Table of Contents

- What is science from the Latin word and its meaning?

- What does the word science mean?

- Who came up with the word science?

- What are the 4 meaning of science?

- What is the full name of science?

- Who was the first female scientist in the world?

- Who was the most famous scientist?

- Who is the first scientist of America?

- What are the 50 types of scientists?

- Who is the greatest scientist of 21st century?

- Who is the most famous chemist?

- Who is the first chemist in the world?

- Who is the best biologist in the world?

- Who was the first chemist in India?

- Who is father of Indian chemistry?

- Who is the best Indian scientist?

- Who is the first woman scientist in ISRO?

- What is the salary of ISRO scientist?

- Who was the missile woman of India?

- Who is the most famous female scientist?

- Who is the most famous woman ever?

- What is the name of missile woman?

- Who was the first Indian lady?

Science (from the Latin word scientia, meaning “knowledge”) is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

What does the word science mean?

1 : knowledge about the natural world that is based on facts learned through experiments and observation. 2 : an area of study that deals with the natural world (as biology or physics) 3 : a subject that is formally studied the science of linguistics.

Who came up with the word science?

William Whewell

What are the 4 meaning of science?

Science is defined as the observation, identification, description, experimental investigation, and theoretical explanation of natural phenomena.

What is the full name of science?

→ Systematic and Comprehensive Investigation and Exploration of Nature’s Causes and Effects. Suggest new Science Full Form.

Who was the first female scientist in the world?

An ancient Egyptian physician, Merit-Ptah ( c. 2700 BC), described in an inscription as “chief physician”, is the earliest known female scientist named in the history of science. Agamede was cited by Homer as a healer in ancient Greece before the Trojan War (c. 1194–1184 BC).

Who was the most famous scientist?

The 10 Greatest Scientists of All Time

- Albert Einstein: The Whole Package.

- Marie Curie: She Went Her Own Way.

- Isaac Newton: The Man Who Defined Science on a Bet.

- Charles Darwin: Delivering the Evolutionary Gospel.

- Nikola Tesla: Wizard of the Industrial Revolution.

- Galileo Galilei: Discoverer of the Cosmos.

Who is the first scientist of America?

Benjamin Franklin, one of the first early American scientists.

What are the 50 types of scientists?

Terms in this set (34)

- Archaeologist. Studies the remains of human life.

- Astronomer. Studies outer space, the solar system, and the objects in it.

- Audiologist. Studies sound and its properties.

- Biologist. Studies all forms of life.

- Biomedical Engineer. Designs and build body parts.

- Botanist.

- Cell Biologist.

- Chemist.

Who is the greatest scientist of 21st century?

21st Century Scientists

- Stephen Hawking. 08 January 1942, British.

- Larry Page. 26 March 1973, American.

- Tim Berners-Lee. 08 June 1955, British.

- Neil deGrasse Tyson. 05 October 1958, American.

- Eduardo Saverin. 19 March 1982, Brazilian.

- Katherine Johnson. 26 August 1918, American.

- Sergey Brin.

- Richard Dawkins.

Who is the most famous chemist?

Top ten greatest chemists

- Alfred Nobel (1833–1896)

- Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907)

- Marie Curie (1867–1934)

- Alice Ball (1892–1916)

- Dorothy Hodgkin (1910–1994)

- Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958)

- Marie Maynard Daly (1921–2003)

- Mario Molina (1943–2020)

Who is the first chemist in the world?

Tapputi

Who is the best biologist in the world?

Ten Top Influential Biologists Today

- Richard Dawkins.

- Carolyn Bertozzi.

- Craig Venter.

- Jennifer Doudna.

- James D. Watson.

- Richard Lewontin.

- Edward O. Wilson.

- Marcus Feldman.

Who was the first chemist in India?

| Asima Chatterjee | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | Indian |

| Alma mater | University of Calcutta |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic chemistry, phytomedicine |

Who is father of Indian chemistry?

Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray

Who is the best Indian scientist?

Famous Indian scientists list

- Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920)

- CV.

- Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944)

- Har Gobind Khorana (1922-2011)

- S.S.

- Meghnad Saha (1893-1956)

- Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (1910-1995)

- Salim Ali (1896-1987)

Who is the first woman scientist in ISRO?

Ritu Karidhal Srivastava Ritu Karidhal

What is the salary of ISRO scientist?

ISRO Scientist Salary 2021: In-hand Salary Per Month, Facilities After 7th Pay Commission

| Post | Pay Band |

|---|---|

| Scientist/ Engineer- SF | INR 37,400 – INR 67,000 |

| Scientist/ Engineer- SG | INR 37,400 – INR 67,000 |

| Scientist/ Engineer- H | INR 37,400 – INR 67,000 |

| Outstanding Scientist | INR 67,000 -INR 79,000 |

Who was the missile woman of India?

Tessy Thomas

Who is the most famous female scientist?

Meet 10 Women in Science Who Changed the World

- Marie Curie, Physicist and Chemist.

- Janaki Ammal, Botanist.

- Chien-Shiung Wu, Physicist.

- Katherine Johnson, Mathematician. Aug.

- Rosalind Franklin, Chemist. July 25, 1920-April 16, 1958.

- Vera Rubin, Astronomer. July 23, 1928-Dec.

- Gladys West, Mathematician. 1930-

- Flossie Wong-Staal, Virologist and Molecular Biologist. Aug.

Who is the most famous woman ever?

Here are the 12 women who changed the world

- Catherine the Great (1729 – 1796)

- Sojourner Truth (1797 – 1883)

- Rosa Parks (1913 – 2005)

- Malala Yousafzai (1997 – Present)

- Marie Curie (1867 – 1934)

- Ada Lovelace (1815 – 1852)

- Edith Cowan (1861 – 1932)

- Amelia Earhart (1897 – 1939)

What is the name of missile woman?

Who was the first Indian lady?

First Ladies and Gentlemen of India

| First Lady of India | |

|---|---|

| Residence | Rashtrapati Bhavan, Delhi (primary) Rashtrapati Nilayam, Hyderabad (winter) The Retreat Building, Shimla (summer) |

| Inaugural holder | Rajvanshi Devi |

| Formation | 26 January 1950 |

| Deputy | Spouse of the Vice President of India |

- Текст

- Веб-страница

The word «science» comes from the Latin word «scientia», which means «knowledge». Science covers the broad field of knowledge that deals with facts and the relationship among these facts.

Scientists study a wide variety of subjects. Some scientists search for clues to the origin of the universe and examine the structure of the cells of living plants and animals. Other researchers investigate why we act the way we do, or try to solve complicated mathematical problems.

Scientists use systematic methods of study to make observations and collect facts. They develop theories that help them order and unify facts. Scientific theories consist of general principles or laws that attempt to explain how and why something happens or has happened. A theory is considered to become a part of scientific knowledge if it has been tested experimentally and proved to be true.

Scientific study can be divided into three major groups: the natural, social, and technical sciences. As scientific knowledge has grown and become more complicated, many new fields of science have appeared. At the same time, the boundaries between scientific fields have become less and less clear. Numerous areas of science overlap each other and it is often hard to tell where one science ends and another begins. All sciences are closely interconnected.

Science has great influence on our lives. It provides the basis of modern technology – the tools and machines that make our life and work easier. The discoveries and the inventions of scientists also help shape our view about ourselves and our place in the universe.

Technology means the use of people’s inventions and discoveries to satisfy their needs. Since people have appeared on the earth, they have had to get food, clothes, and shelter. Through the ages, people have invented tools, machines, and materials to make work easier.

Nowadays, when people speak of technology, they generally mean industrial technology. Industrial technology began about 200 years ago with the development of the steam engine, the growth of factories, and the mass production of goods. It influenced different aspects of people’s lives. The development of the car influenced where people lived and worked. Radio and television changed their leisure time. The telephone revolutionized communication.

Science has contributed much to modern technology. Science attempts to explain how and why things happen. Technology makes things happen. But not all technology is based on science. For example, people had made different objects from iron for centuries before they learnt the structure of the metal. But some modern technologies, such as nuclear power production and space travel, depend heavily on science.

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Слово «наука» происходит от латинского слова «scientia», что означает «знание». Наука охватывает широкие области знаний, которая имеет дело с фактами и взаимосвязь между этими фактами.Ученые изучают широкий спектр предметов. Некоторые ученые ищут ключи к происхождение вселенной и изучить структуру клеток живых растений и животных. Другие исследователи расследовать, почему мы так, что мы делаем, или попытаться решить сложные математические проблемы.Ученые используют систематические методы исследования наблюдения и сбора фактов. Они разрабатывают теории, которые помогают им порядок и унифицировать факты. Научные теории состоят из общих принципов или законов, которые пытаются объяснить, каким образом и почему что-то происходит или произошло. Считается, что теория стать частью научных знаний, если они проверены экспериментально и подтвердилось.Научное исследование можно разделить на три основные группы: естественные, социальные и технические науки. Как научные знания выросла и становятся более сложными, появились многие новые области науки. В то же время границы между научными областями стали менее ясно. Многочисленные области науки перекрывают друг друга, и это часто трудно сказать, где заканчивается одна наука и начинается другое. Все науки тесно взаимосвязаны.Наука имеет большое влияние на нашу жизнь. Она обеспечивает основу современной технологии – инструменты и машины, которые делают нашу жизнь и работу легче. Открытия и изобретения ученых также помогают формировать наш взгляд о себе и наше место во Вселенной.Технология подразумевает использование изобретений и открытий для удовлетворения потребностей людей. Поскольку люди появились на земле, они были вынуждены получать продовольствие, одежду и жилье. На протяжении веков люди придумали инструменты, машины и материалы, чтобы сделать работу легче.В настоящее время когда люди говорят о технологии, они обычно означают промышленной технологии. Промышленная технология началась около 200 лет назад с развитием парового двигателя, рост фабрик и массового производства товаров. Его влияние на различные аспекты жизни людей. Разработка автомобиля, где люди жили и работали. Радио и телевидение изменили свое свободное время. Телефон революцию связи.Наука внесла много современной технологии. Наука пытается объяснить, как и почему вещи происходят. Технология делает вещи случаются. Но не все технология основана на науке. Например люди сделали различные предметы из железа на протяжении веков, прежде чем они узнали структуру металла. Но некоторые современные технологии, такие, как производство ядерной энергии и космических путешествий, в значительной степени зависят от науки.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Слово «наука» происходит от латинского слова «Scientia», что означает «знание». Наука охватывает широкое поле знаний , который имеет дело с фактами и взаимосвязи между этими фактами.

Ученые изучают широкий спектр предметов. Некоторые ученые ищут подсказки о происхождении Вселенной и изучить структуру клеток живых растений и животных. Другие исследователи выяснить , почему мы действуем так , как мы делаем, или пытаться решать сложные математические задачи.

Ученые используют систематические методы исследования для наблюдений и сбора фактов. Они разрабатывают теории , которые помогают им упорядочить и унифицировать факты. Научные теории состоят из общих принципов или законов , которые пытаются объяснить , как и почему что — то происходит или произошло. Теория считается , чтобы стать частью научного знания , если оно было проверено экспериментально и подтвердилось.

Научное исследование можно разделить на три основные группы: естественные, социальные и технических наук. Научные знания выросли и стали более сложными, появилось много новых областей науки. В то же время, границы между научными полями стали меньше и менее ясна. Многочисленные области науки накладываются друг на друга , и часто трудно сказать , где заканчивается наука и начинается другая. Все науки тесно связаны между собой.

Наука имеет большое влияние на нашу жизнь. Она обеспечивает основу современной технологии — инструменты и машины , которые делают нашу жизнь и работу проще. Открытия и изобретений ученых также помогают формировать наше представление о нас самих и о нашем месте во Вселенной.

Технология подразумевает использование изобретений и открытий людей , чтобы удовлетворить их потребности. Так как люди появились на земле, они должны были получить пищу, одежду и кров. На протяжении веков люди изобрели инструменты, машины и материалы , чтобы сделать работу легче. В

наше время, когда люди говорят о технологии, они обычно означают промышленные технологии. Промышленная технология началась около 200 лет назад с развитием парового двигателя, рост заводов и массового производства товаров. Это влияние различные аспекты жизни людей. Развитие автомобиля повлияли где люди жили и работали. Радио и телевидение изменили свое свободное время. Телефон произвел революцию связи.

Наука внесла большой вклад в современные технологии. Наука пытается объяснить , как и почему вещи случаются. Технология делает вещи случаются. Но не все технологии основаны на науке. Например, люди сделали различные предметы из железа на протяжении многих веков , прежде чем они узнали структуру металла. Но некоторые современные технологии, такие как производство атомной энергетики и космических путешествий, в значительной степени зависит от науки.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

слово «наука» происходит от латинского слова «Scientia», что означает «знания».наука охватывает широкие области знаний, что касается фактов и взаимосвязи между этими фактами.ученые изучают разнообразные темы.некоторые ученые ищут ключи к разгадке происхождения вселенной и изучении структуры клетки живых растений и животных.другие исследователи расследование, почему мы будем действовать так, как мы делаем это, или попытаться решить сложные математические проблемы.ученые используют последовательных методов исследования делать замечания и собирать факты.они разрабатывают теории, которые помогают им порядка и унифицировать факты.научные теории состоит из общих принципов или законы, которые пытаются объяснить, как и почему происходит что — то и произошло.теория, как считается, стать частью научных знаний, если она была проверена экспериментально и подтвердятся.научные исследования, можно разделить на три основные группы: природных, социальных, технических наук.в качестве научных знаний растет и усложняется, много новых областях науки, появились.в то же время границы между научной областях становятся все менее и менее ясным.в многочисленных областях науки перекрывают друг друга и зачастую трудно сказать, где заканчивается наука и начинается другая.все науки тесно взаимосвязаны.наука имеет большое влияние на нашу жизнь.он обеспечивает основу современных технологий, инструментов и станков, которые делают нашу жизнь и работу легче.открытия и изобретения ученых, помочь сформировать свое мнение о себе и наше место во вселенной.технология означает использование народной изобретений и открытий, чтобы удовлетворить их потребности.поскольку люди появились на земле, они должны были получить продовольствие, одежда и жилье.на протяжении веков люди изобрели инструментов, машин, и материалами, чтобы сделать работу легче.сегодня, когда говорят о технологии, они, как правило, имею в виду промышленных технологий.промышленные технологии начали около 200 лет назад в развитие парового двигателя, рост на заводах, и массового производства товаров.это повлияло на различные аспекты жизни людей.развитие машину влияние, где люди живут и работают.радио и телевидение изменило свое свободное время.телефон революцию в коммуникации.наука вносит много современных технологий.наука пытается объяснить, как и почему случается.технология позволяет вещам.но не все технологии на основе науки.например, люди сделали разные предметы из железа на протяжении веков до того, как они узнали структуру металла.но некоторые современные технологии, такие, как производство атомной энергии и космических путешествий, в значительной степени зависят от науки.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- What have the children done? Match the s

- крыльная связка

- match the words in bold from the text wi

- The healthiest way of life for a person

- Много студентов учатся хорошо

- Время

- We usually have.. Lessons a day

- The healthiest way of life for a person

- ну так в другой раз значит

- Nature’s little helpers People have been

- Engineering has become a profession. A p

- si vos valetis bene est ego vales

- Доброе утро, любимая моя.

- Зрелая защита позволяет наиболее эффекти

- The word «science» comes from the Latin

- Wusstet ihr, dass die Römer viele Elemen

- I have a lot of friends mostly girls

- Wusstet ihr, dass die Römer viele Elemen

- The word «science» comes from the Latin

- я не умею писать по английски

- The word «science» comes from the Latin

- я не умею писать по английски

- What have the children done? Match the s

- Wusstet ihr, dass die Römer viele Elemen

WHAT IS SCIENCE? • Latin word “scientia, ” meaning knowledge • Is a process of constructing, organizing, and testing explanations and predictions about the world around us.

ORIGIN • Originally considered a philosophy, or an investigation of everyday problems • Used by early hominids and humans to survive the day to day, any ideas how? • Science thrives on scaffolding, using what you know to figure out what you do not know.

pro et contra “for and against” • What are the advantages of using science? • Why? • What are the disadvantages? • Why?

Science in the Classroom • Why is the study of science vital to your success in this classroom, the work place, and in everyday situations? • Is science or the scientific process a learned or “innate” behavior?

SCIENCE 101 • You must use a scientific method! • What is a scientific method? • A scientific method is a technique for acquiring, investigating, correcting and integrating knowledge

Scientific Method • • Observation Problem Hypothesis Experiment Data Analysis Conclusion

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Observation – what do you see, smell, taste, touch, hear or “sense” • Good • Bad Divebums. com

National geographic

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Problem – what seems to be the problem? Issue? Question? Interest? National geographic

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Hypothesis – proposed explanation of observed problem based on what you know. National park service –dry tortugas Jefferycarrier. net

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Experiment – a test or procedure that will challenge your hypothesis in regards to your observed problem. • Accept / Support • Reject / Challenge National park service – dry tortugas

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Data – collected information from an experiment to test a hypothesis about a problem that was observed. • Once data has been collected it CANNOT be changed or altered. Why? • What are some examples of data that you might collect tagging animals?

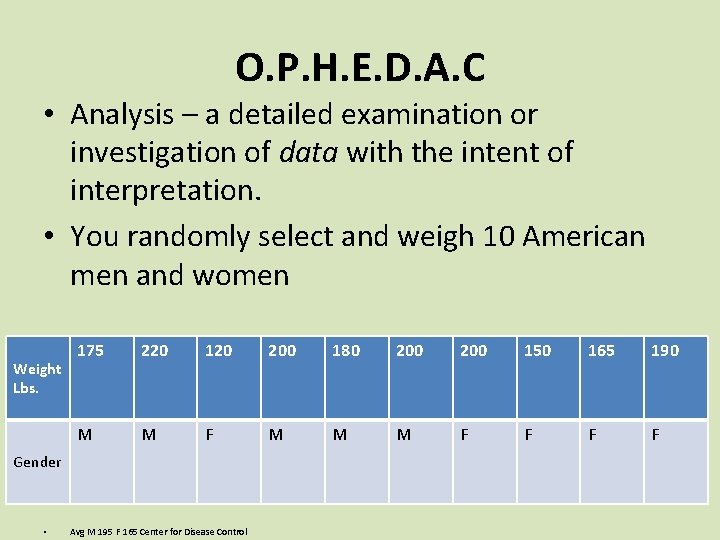

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Analysis – a detailed examination or investigation of data with the intent of interpretation. • You randomly select and weigh 10 American men and women Weight Lbs. 175 220 120 200 180 200 150 165 190 M M F M M M F F Gender • Avg M 195 F 165 Center for Disease Control

O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Conclusion – a well-structured outcome or result using the analysis of the collected data which supports or rejects the hypothesis. • A rejected hypothesis is extremely important, knowing what something is not can help you discover what something is.

Scientific Experiment • Utilizes a scientific method, O. P. H. E. D. A. C • Tests a hypothesis made from an observed problem. • Experiments need to be designed so they can be repeated. Why? • The more tests/experiments performed the better the results. Why?

Experimental Design • Variables – liable to change, changeable. • Independent Variable (IV) — the variable that is changed, “input” • Dependent Variable (DV) – the variable that changes because of the IV, “output” • Control – used for comparison, shows “change” • Constant – a fixed variable that is not changed.

General Science • Science uses a “standard” language. Why? • “le systeme International d’unites” fr. for the International System of Units, SI units • What are some SI units?

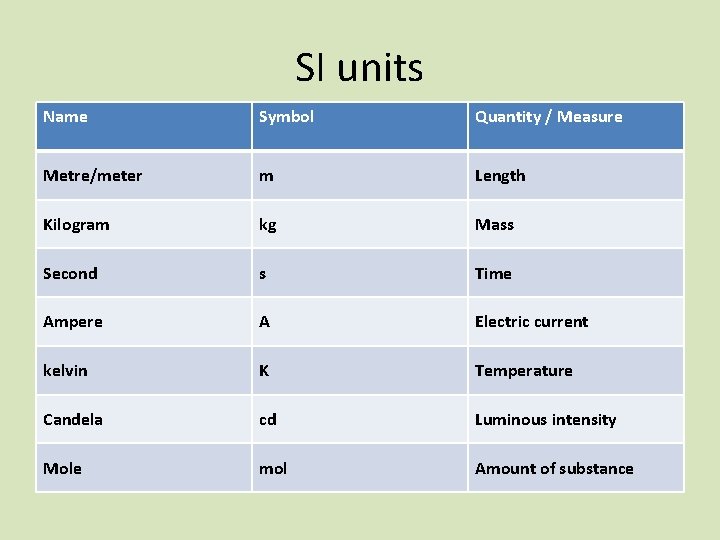

SI units Name Symbol Quantity / Measure Metre/meter m Length Kilogram kg Mass Second s Time Ampere A Electric current kelvin K Temperature Candela cd Luminous intensity Mole mol Amount of substance

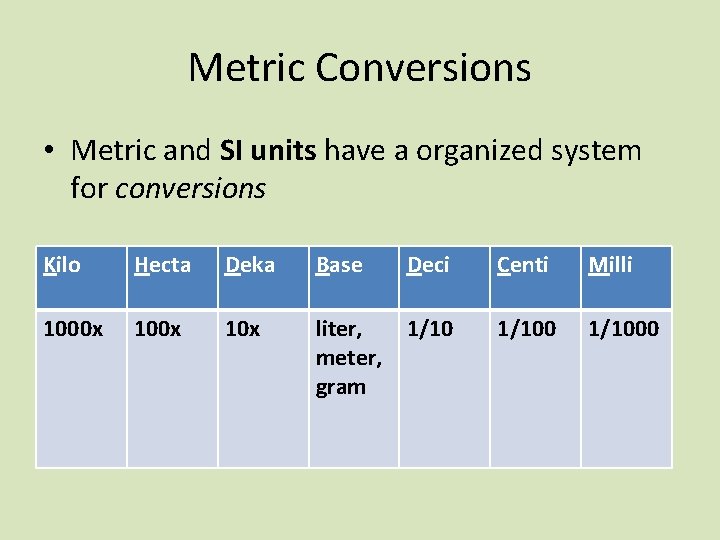

Metric Conversions • Metric and SI units have a organized system for conversions Kilo Hecta Deka Base Deci Centi Milli 1000 x 10 x liter, meter, gram 1/1000

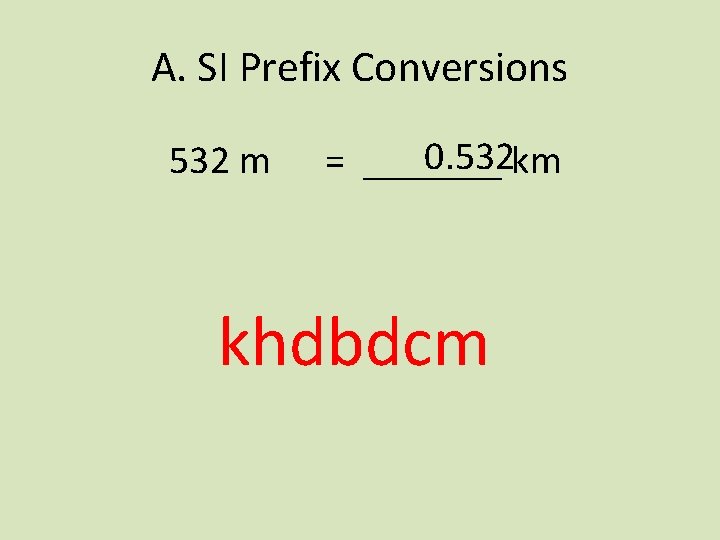

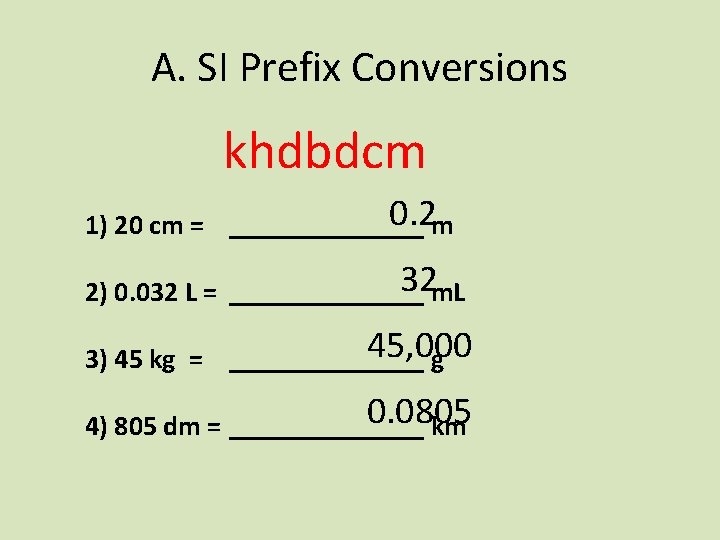

A. SI Prefix Conversions 532 m 0. 532 km = _______ khdbdcm

A. SI Prefix Conversions khdbdcm 0. 2 m 1) 20 cm = _______ 32 m. L 2) 0. 032 L = _______ 45, 000 3) 45 kg = _______ g 0. 0805 4) 805 dm = _______ km

Matter • Anything that has both mass and volume • What are three states of matter? • Solid, Liquid, Gas National geographic Bbc. co. uk Sciencedaily. com

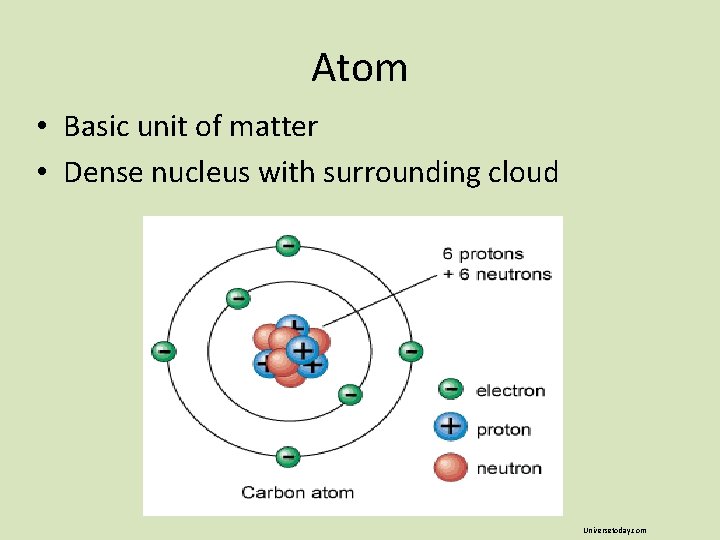

Atom • Basic unit of matter • Dense nucleus with surrounding cloud Universetoday. com

Element • Pure sample of one “type” of atom • Properties governed by atomic structure Periodictable. com

Energy • The capacity of a system to perform work • Occurs in many different forms or “states” Nationalgeographic. com

System • systema grk. “whole of separate parts” • A closed series of components and their relationships. Examples? serc. carleton. edu

WHAT IS EARTH SCIENCE? • The study of the dynamic processes, cycles, and forces that interact on planet Earth and its’ place in the universe – Formation – Composition – History – Characteristics

Earth Science • Utilizes a wide range of scientific disciplines to examine the Earth and its’ processes, examples? • What exactly will we be studying?

Earth Science • There are four major areas • • Astronomy Meteorology Geology Oceanography

Astronomy • Study of objects beyond the Earth’s atmosphere • What would you study? • What is the appropriate title for a scientist who studies Astronomy? • Astronomer, “astro” relating to celestial bodies • NOT ASTROLOGY!!!

Meteorology • Study of the air and gaseous space surrounding the Earth • What would you study? • What is the appropriate title for a scientist who studies Meteorology? • Meteorologist, meteoros- grk. “high in sky”

Geology • Study of the composition and processes that form and change the state of the Earth • What would you study? • What is the appropriate title for a scientist who studies Geology? • Geologist, “geo” relating to the Earth

Oceanography • Study of the Earth’s oceans • What would you study? • What is the appropriate title for a scientist who studies Oceanography? • Oceanographer, “okeanos” grk. the ocean world

Earth Science • These major areas focus on understanding the four main systems on Earth • Lithosphere • Hydrosphere • Atmosphere • Biosphere

What is Environmental Science? • The study of the environment through the use of both the physical and biological sciences • What is an environment? • The cumulative effects and conditions resulting from all of the physical and biological factors • Why study the environment?

Environmental Science vs. Environmentalism • Environmental Science does not have an agenda! • Environmental Scientists study the conditions, factors, and states of an environment • Environmentalism has an agenda! • Concerned with a personal opinion or preference for the environment, “tree hugger” • Which of the two will we focus on? Why?

Enviro Science vs. Enviro-ism • Stand Up…. quietly. • You will be given a scenario, you must decide if you are for or against…. . and why!

Introduction

The Latin word scientia, which means “knowing” or “being skilled,” is the source of the English word science. It has become common, especially in school curricula, to restrict the usage of the word science to the study of the physical, earth, space, and life sciences—for example, physics, chemistry, geology, astronomy, biology, and anatomy.

The branches of study that are now called sciences once fell under the heading of philosophy, an umbrella term that suggested the pursuit of knowledge. As recently as the early 19th century, physicists and chemists were still called philosophers. Adam Smith, who originated the modern study of economics, was known as a moral philosopher rather than as an economist. The word scientist was invented in 1840 by an English writer, William Whewell. It came gradually to refer to practitioners of a specialized field of knowledge. The prestige of the natural sciences at the time lent its weight to them, in contrast to other branches of study that were not considered to use the scientific method.

The scientific method today is not limited to the methods used in specific branches of science. Every area of study has its own specific goals and its own methods for reaching them. For example, most chemistry research takes place in a lab, while botanical studies may be conducted in greenhouses or in the field. However, the overarching process of the scientific method—forming a hypothesis based on observations of phenomena and using a rigorous approach to investigating that hypothesis—is the foundation of modern research in all areas of science. The goals and methods of research in physics are not the same as those of botany or geology, yet all follow a standard approach to study questions of interest. Other fields of study—economics, sociology, archaeology, or psychology—may also be called sciences because they pursue knowledge by suitable methods.

No science is ever a fixed body of knowledge. This is indicated by the word scientific, which means science making—an ongoing process of searching for new information. When the process of making knowledge ceases, what is left is a tradition to be passed from one generation to another. Science does not exclude its tradition but continues developing it. In a letter to physicist Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton paid tribute to science makers who preceded him: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

There are no distinct boundaries separating the various fields. A relationship exists between all of them. Each field uses its own information and methods as well as those of others. The entire field of science is too large to be studied as a whole, so it is divided into different fields based on commonalities. The sciences can be broadly divided into two main areas: the natural sciences and the social sciences. The natural sciences consist of the physical sciences, earth and space sciences, and life (biological) sciences. The social sciences comprise fields that study social and cultural elements of human behavior, such as economics and sociology. Each of these categories includes many specialized fields. Some fields, such as biochemistry and physical archaeology, combine two or more of the others.

The Physical Sciences

Physical science deals with nonliving things—from the tiny particles that make up an atom to the universe itself. It can be divided broadly into three main subject areas: physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

Physics

The field of physics studies forms of energy such as heat, sound, and light. Concerned with the nature and sources of energy, it also explores how one form of energy is changed to another. Its study encompasses not only the behavior of objects under the action of given forces but also the nature and origin of gravitational, electromagnetic, and nuclear force fields.

Electronics concerns the study and control of electrons, especially in relation to computers and to transistors. Some physicists observe the nature of substances at extremely low (cryogenic) or high temperatures. Thermodynamics is the study of heat as it is produced by the motion of molecules.

Light physics deals with the physical characteristics of radiant energy as they affect sight. This field also includes forms of radiant energy that are not part of the visible spectrum. Optics is the study of all phenomena of electromagnetic waves of wavelengths less than those of microwaves yet greater than those of X-rays. Sound is the subject of a number of fields in physics, including acoustics and ultrasonics.

Nuclear physics involves the study of particles found in the nuclei of atoms together with the energy effects produced when the nuclear particles are disturbed by external forces. Solid state physics deals with the properties and structures of solid materials, including crystals.

Mechanics is a broad field that investigates the effects of forces on bodies in motion or at rest. It embraces the fields of dynamics, the study of forces that produce or change motion, and statics, the study of balanced forces or bodies at rest. Aerodynamics is the study of fluid mechanics as it is related to motion between a fluid (air) and a solid. Hydrodynamics is concerned with liquids in motion. Kinematics is the study of motion apart from its effects upon bodies. Kinetics deals with the changes in motion as they are caused by forces not in equilibrium.

Engineering is the application of scientific principles used in converting natural resources into structures, machines, products, and processes for the benefit of mankind. There are traditionally four basic engineering disciplines: civil, mechanical, electrical, and chemical engineering. Other engineering disciplines are concerned with mining, nuclear technology, and environmental control.

Chemistry

Chemistry is the study of the properties, composition, and structure of substances, which are defined as elements and compounds. It seeks to explain the transformations that these substances undergo and the energy that is released or absorbed during these processes.

The science of chemistry embraces many other subfields, including analytical chemistry, organic chemistry, inorganic chemistry, physical chemistry, colloid chemistry, biochemistry, electrochemistry, nuclear chemistry, and chemical engineering. Biochemistry and organic chemistry, which deal with the chemistry of living things, are examples of how the physical sciences and biological sciences are linked to one another.

Other special fields of chemistry deal with its application in various industries. Metallurgy, for example, deals with the recovery of metals from their ores. A branch of metallurgy is concerned with the making of metal alloys for specific purposes. Petroleum chemistry is confined to the commercial manufacture of products from crude oil.

Mathematics

Mathematics is an ancient science that deals with logical reasoning and quantitative calculation—with numbers, shapes, and various ways of counting and measuring. Modern mathematics has evolved from a simple science to a very abstract field of theory. It is the language used by all the other sciences and is the basis for precision in many scientific fields.

Arithmetic is the science of computation by the use of numbers. Algebra is the study of relationships between numbers as they are represented by symbols. Geometry is a science that deals with the measurements and relationships of lines and angles. Calculus is the system of mathematics used to figure the rate of change of a function. There are two types of calculus: differential calculus, which deals with the rate of change of a variable, and integral calculus, which concerns the limiting values of differentials and is used to determine length, volume, or area. The assembling of information in numerical form, together with the processes of tabulation and interpretation, is the concern of statistics.

The Earth and Space Sciences

The Earth sciences seek to understand the features and phenomena of the Earth, its waters, and its atmosphere. The space sciences study stars, the planets, the solar system, and the universe.

Earth sciences

The Earth sciences in general aim to understand the present features and the past evolution of the Earth. This includes the many physical and chemical—and some biological—aspects of the Earth’s atmosphere, waters, surface, and internal structure. Particular phases of the Earth sciences include careful measurements of the Earth’s magnetism, gravity, size, and shape.

The Earth sciences include a number of specific disciplines. Perhaps the broadest of these is geology, the study of the history, structure, and composition of the Earth and the past and present processes that act on it. Among the many other basic Earth sciences are geomorphology, geophysics, seismology, geochemistry, meteorology, climatology, hydrology, and oceanography and marine science.

Some Earth sciences have great applications in society. Meteorology, for example, provides information regarding weather conditions for the purpose of providing forecasts. Climatology studies current and past patterns and trends in global climate. The understanding of earthquake patterns and behaviors is based largely on knowledge gleaned from seismology.

Astronomy

The science of astronomy deals with the origin, evolution, composition, distances, sizes, and movements of the bodies and matter within the universe. It includes astrophysics, which focuses on the physical properties and structure of all cosmic matter. In astrometry, the sizes, distances, and motions of heavenly bodies are measured. Astronautics is the science that enables humans to navigate in outer space.

Celestial mechanics, which investigates the motion of bodies in space and the way they are influenced by gravitational attraction, is used to determine the weight and speed of Earth satellites. Cosmology deals with the origin, structure, and evolution of the entire universe. In radio and radar astronomy, radio and radar signals are beamed from Earth to bodies relatively close to the Earth—meteor trails, the moon, nearby planets—to gain information about them by means of the echoes.

Other areas of astronomy involve monitoring the X-rays, gamma rays, ultraviolet rays, and infrared radiation emitted by celestial bodies. Celestial navigation is a way of determining one’s location on the Earth by measuring the positions of stars above. Archaeoastronomy relates archaeology, anthropology, and mythology with astronomy.

The Biological Sciences

Biological science deals with the relationships between all living things, their environments, and the need to maintain certain conditions to preserve life. Despite their apparent differences, all of the biological science fields are interrelated by basic principles. The sciences of zoology and botany, dealing respectively with animals and plants, have contributed greatly to the field of medicine.

Biology

Biology is the study of all living things—plants and animals—and their vital processes. The two main divisions of biology are zoology, the study of animals, and botany, the study of plants. Another biological discipline is physiology, the study of the functioning of organs and the chemical and physical processes in living things. Much of the current knowledge of physiology was obtained from studying the responses of cells and tissues to imposed environmental changes. New techniques have extended the boundaries of physiology. For example, radioactive isotopes are now used in the measurement of amounts and fluxes of substances present at low concentrations inside cells and in extracellular fluids. Cytology, the study of cells, is thus related to physiology. The structure, function, and classification of microorganisms, including protozoans, algae, molds, bacteria, and viruses, are concerns of microbiology.

The study of the size, shape, and structure of animals, plants, and microorganisms and the relationships of their internal parts is called morphology. The term morphology is sometimes confused with the term anatomy. Whereas anatomy describes the structure of organisms, by dissection and by other means, morphology is concerned with explaining the shapes and arrangement of the parts of organisms as they relate to evolution, function, and development.

Biophysics is concerned with the application of the principles and methods of the physical sciences to biological problems. Major areas deal with the influence of physical agents, such as electricity in nerves or mechanical force in muscles; the interaction of living organisms with physical agents such as light or sound; and interactions between living things and their environment, as in locomotion, navigation, and communication. Biochemistry is the study of the chemical substances that make up cells and play a key role in chemical reactions vital to life.

Genetics is the study of heredity in general and genes in particular. It has been applied to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of hereditary diseases; to the breeding of plants and animals; and to the development of industrial processes that use microorganisms.

Among the many other fields of biology are embryology, the study of fetal development; ecology, the study of organisms and their interactions with other organisms and with their environment; and taxonomy, the classification of plants and animals. The development, care, and cultivation of trees and forests are the focus of forestry.

Medical science

By definition an art as well as a science, the medical sciences are concerned with the maintenance of health and the prevention, alleviation, or cure of disease. While the field of medicine as it relates to human health is well known, the medical sciences comprise a wide number of specialties. Veterinary medicine deals specifically with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease in animals. Dentistry focuses on the treatment of teeth. Psychiatry is a branch of medicine that concerns the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental disorders. Psychology, which is sometimes classed with the social sciences, is the study of behavior and behavioral manifestations of experience in humans and other animals.

The Social Sciences

Any discipline or branch of science that deals with the social and cultural aspects of human behavior can be called a social science. Among the disciplines comprising the social sciences are economics, sociology, geography, and political science. The term behavioral science is used to describe some social sciences, such as anthropology and linguistics, that deal with human behavior. Psychology is often classified as a social science.

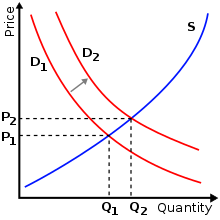

Economics

The field of economics is concerned chiefly with the description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Microeconomics deals with the behavior of individual areas or units of activity, such as individual farmers, business firms, and traders. Macroeconomics is the study of whole systems, especially with regard to general levels of output and income and the interrelations between different sectors of the economy.

Sociology

The scientific study of society, social institutions, and social relationships is called sociology. It involves the structure, interaction, and collective behavior of organized groups of people. A related field, social psychology, deals with the manner in which the personality, attitudes, motivations, and behavior of the individual are influenced by social groups.

Geography

With aspects of physical as well as social science, geography is the study of the features of the Earth’s surface and of their relationships to each other and to humankind. Physical geography incorporates some Earth sciences such as climatology as well as hydrography and the study of landforms known as geomorphology. Human geography involves the economic, political, and social activities of people in communities and cultures. The structure and dynamics of human populations, including age, sex, births, deaths, and migratory movements, are investigated in the field of demography.

Political science

Political science studies the origin, development, structure, powers, functions, underlying philosophy, and administration of the different forms of government. Political scientists investigate governments at all levels—local to international. Among its other areas of focus are business, labor, and legislative programs, natural resources, and regional planning. Although most historians regard history as one of the humanities, many consider it a science. Law, the discipline concerned with the customs and rules governing a community, is also sometimes regarded as a science, particularly comparative law.

Anthropology

Anthropology is sometimes called the science of humanity. It is broadly divided into four areas—cultural anthropology, linguistics, physical anthropology, and archaeology. Human culture, especially with respect to social structure, language, law, politics, religion, art, and technology, is the focus of cultural anthropology. It is particularly concerned with patterns in human behavior as a description of social and cultural phenomena. Since language is the critical factor that sets humans apart from the other animals, linguistics is a basic study in the social sciences. A further refinement of linguistics, semantics deals with the evolution and essential meanings of words. Physical anthropology is concerned with similarities and differences between humans and their human and nonhuman ancestors; it examines these relationships through comparisons of physical characteristics. Archaeology is the science that examines the cultures of earlier peoples and civilizations.

Additional Reading

Asimov, Isaac.

Isaac Asimov’s Wonderful Worldwide Science Bazaar (Houghton, 1986).

Barnes, Barry.

About Science (Blackwell, 1985).

Brooks, Culver.

Introduction to Science (Paladin House, 1986).

Gabel, Dorothy.

Introductory Science Skills (Waveland, 1982).

Maxwell, Nicholas.

From Knowledge to Wisdom (Blackwell, 1984).

Rensberger, Boyce.

How the World Works (Morrow, 1986).

Snow, C.P.

Two Cultures (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1969).

(See also bibliographies in articles on the fields of the sciences.)

What is science?

Science (from the Latin word scientia, meaning “knowledge”)[1] is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.[2][3][4]

The earliest roots of science can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3500 to 3000 BCE.[5][6] Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes.[5][6] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages[7] but was preserved in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age.[8] The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived “natural philosophy”,[7][9] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[10] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[11][12][13][14] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape;[15][16][17] along with the changing of “natural philosophy” to “natural science.”[18]

Modern science is typically divided into three major branches that consist of the natural sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics), which study nature in the broadest sense; the social sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies; and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study abstract concepts. There is disagreement,[19][20] however, on whether the formal sciences actually constitute a science as they do not rely on empirical evidence.[21] Disciplines that use existing scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine, are described as applied sciences.[22][23][24][25]

Science is based on research, which is commonly conducted in academic and research institutions as well as in government agencies and companies. The practical impact of scientific research has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the development of commercial products, armaments, health care, and environmental protection.

Branches of science

Modern science is commonly divided into three major branches that consist of the natural sciences, social sciences, and formal sciences. Each of these branches comprise various specialized yet overlapping scientific disciplines that often possess their own nomenclature and expertise.[90] Both natural and social sciences are empirical sciences[91] as their knowledge is based on empirical observations and is capable of being tested for its validity by other researchers working under the same conditions.[92]

There are also closely related disciplines that use science, such as engineering and medicine, which are sometimes described as applied sciences. The relationships between the branches of science are summarized by the following table.

| Science | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal science | Empirical sciences | ||

| Natural science | Social science | ||

| Foundation | Logic; Mathematics; Statistics | Physics; Chemistry; Biology; Earth science; Space science |

Economics; Political science; Sociology; Psychology |

| Application | Computer science | Engineering; Agricultural science; Medicine; Dentistry; Pharmacy |

Business administration; Jurisprudence; Pedagogy |

Natural science

Natural science is concerned with the description, prediction, and understanding of natural phenomena based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. It can be divided into two main branches: life science (or biological science) and physical science. Physical science is subdivided into branches, including physics, chemistry, astronomy and earth science. These two branches may be further divided into more specialized disciplines. Modern natural science is the successor to the natural philosophy that began in Ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches which were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science.[93] Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and so on.[94] Today, “natural history” suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.[95]

Social science is concerned with society and the relationships among individuals within a society. It has many branches that include, but are not limited to, anthropology, archaeology, communication studies, economics, history, human geography, jurisprudence, linguistics, political science, psychology, public health, and sociology. Social scientists may adopt various philosophical theories to study individuals and society. For example, positivist social scientists use methods resembling those of the natural sciences as tools for understanding society, and so define science in its stricter modern sense. Interpretivist social scientists, by contrast, may use social critique or symbolic interpretation rather than constructing empirically falsifiable theories, and thus treat science in its broader sense. In modern academic practice, researchers are often eclectic, using multiple methodologies (for instance, by combining both quantitative and qualitative research). The term “social research” has also acquired a degree of autonomy as practitioners from various disciplines share in its aims and methods.

Formal science

Formal science is involved in the study of formal systems. It includes mathematics,[96][97] systems theory, and theoretical computer science. The formal sciences share similarities with the other two branches by relying on objective, careful, and systematic study of an area of knowledge. They are, however, different from the empirical sciences as they rely exclusively on deductive reasoning, without the need for empirical evidence, to verify their abstract concepts.[21][98][92] The formal sciences are therefore a priori disciplines and because of this, there is disagreement on whether they actually constitute a science.[19][20] Nevertheless, the formal sciences play an important role in the empirical sciences. Calculus, for example, was initially invented to understand motion in physics.[99] Natural and social sciences that rely heavily on mathematical applications include mathematical physics, mathematical chemistry, mathematical biology, mathematical finance, and mathematical economics.

References

- Harper, Douglas. “science”. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- Wilson, E.O. (1999). “The natural sciences”. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York, New York: Vintage. pp. 49–71. ISBN978-0-679-76867-8.

- “… modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions.”— p.vii Heilbron, J.L. (editor-in-chief)(2003). “Preface”. The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–X. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

- “science”. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved October 16, 2011. 3 a:knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method b: such knowledge or such a system of knowledge concerned with the physical world and its phenomena.

- “The historian … requires a very broad definition of “science” – one that … will help us to understand the modern scientific enterprise. We need to be broad and inclusive, rather than narrow and exclusive … and we should expect that the farther back we go [in time] the broader we will need to be.” p.3—Lindberg, David C. (2007). “Science before the Greeks”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context(Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Grant, Edward (2007). “Ancient Egypt to Plato”. A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN978-052-1-68957-1.

- Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The revival of learning in the West”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Lindberg, David C. (2007). “Islamic science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–92. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The recovery and assimilation of Greek and Islamic science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–53. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). “Introduction”. Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (First ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN978-0-199-56741-6.

- Lindberg, David C. (1990). “Conceptions of the Scientific Revolution from Baker to Butterfield: A preliminary sketch”. In David C. Lindberg; Robert S. Westman (eds.). Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution (First ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN978-0-521-34262-9.

- Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The legacy of ancient and medieval science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Del Soldato, Eva (2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Fall 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Grant, Edward (2007). “Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century”. A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–322. ISBN978-052-1-68957-1.

- Cahan, David, ed. (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-08928-7.

- The Oxford English Dictionarydates the origin of the word “scientist” to 1834.

- Lightman, Bernard (2011). “13. Science and the Public”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature : From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN978-0226317830.

- Harrison, Peter(2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 9780226184517. The changing character of those engaged in scientific endeavors was matched by a new nomenclature for their endeavors. The most conspicuous marker of this change was the replacement of “natural philosophy” by “natural science”. In 1800 few had spoken of the “natural sciences” but by 1880, this expression had overtaken the traditional label “natural philosophy”. The persistence of “natural philosophy” in the twentieth century is owing largely to historical references to a past practice (see figure 11). As should now be apparent, this was not simply the substitution of one term by another, but involved the jettisoning of a range of personal qualities relating to the conduct of philosophy and the living of the philosophical life.

- Bishop, Alan (1991). “Environmental activities and mathematical culture”. Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN978-0-792-31270-3.

- Bunge, Mario (1998). “The Scientific Approach”. Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory. 1(revised ed.). New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN978-0-765-80413-6.

- Fetzer, James H. (2013). “Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems”. Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines (1st ed.). Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 271–308. ISBN978-1-443-81946-6.

- Fischer, M.R.; Fabry, G (2014). “Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education”. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung. 31(2): Doc24. doi:3205/zma000916. PMC 4027809. PMID 24872859.

- Abraham, Reem Rachel (2004). “Clinically oriented physiology teaching: strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students”. Advances in Physiology Education. 28(3): 102–04. doi:1152/advan.00001.2004. PMID 15319191.

- Sinclair, Marius. “On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods”. The International Journal of Engineering Education.

- “Engineering Technology :: Engineering Technology :: Purdue School of Engineering and Technology, IUPUI”. www.engr.iupui.edu. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Grant, Edward (January 1, 1997). “History of Science: When Did Modern Science Begin?”. The American Scholar. 66(1): 105–113. JSTOR 41212592.

- Pingree, David(December 1992). “Hellenophilia versus the History of Science”. Isis. 83 (4): 554–63. Bibcode:..83..554P. doi:10.1086/356288. JSTOR 234257.

- Sima Qian(司馬遷, d. 86 BCE) in his Records of the Grand Historian (太史公書) covering some 2500 years of Chinese history, records Sunshu Ao (孫叔敖, fl. c. 630–595 BCE – Zhou dynasty), the first known hydraulic engineer of China, cited in (Joseph Needham et al. (1971) Science and Civilisation in China 3 p. 271) as having built a reservoir which has lasted to this day.

- Rochberg, Francesca (2011). “Ch.1 Natural Knowledge in Ancient Mesopotamia”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature : From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN978-0226317830.

- McIntosh, Jane R. (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California, Denver, Colorado, and Oxford, England: ABC-CLIO. pp. 273–76. ISBN978-1-57607-966-9.

- Aaboe (May 2, 1974). “Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 276(1257): 21–42. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276…21A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007. JSTOR 74272.

- R D. Biggs (2005). “Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia”. Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19(1): 7–18.

- Lehoux, Daryn (2011). “2. Natural Knowledge in the Classical World”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature : From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 39. ISBN978-0226317830.

- See the quotation in Homer(8th century BCE) Odyssey302–03

- “Progress or Return” in An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss(Expanded version of Political Philosophy: Six Essays by Leo Strauss, 1975.) Ed. Hilail Gilden. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1989.

- Cropsey; Strauss (eds.). History of Political Philosophy (3rd ed.). p. 209.

- O’Grady, Patricia F. (2016). Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 245. ISBN978-0-7546-0533-1.

- Burkert, Walter(June 1, 1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018.

- Pullman, Bernard (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. pp. 31–33. Bibcode:book…..P. ISBN978-0-19-515040-7.

- Cohen, Henri; Lefebvre, Claire, eds. (2017). Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science(Second ed.). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2.

- Margotta, Roberto (1968). vFZrAAAAMAAJ The Story of MedicineCheck |url= value (help). New York City, New York: Golden Press.

- Touwaide, Alain (2005). Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven; Wallis, Faith (eds.). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 224. ISBN978-0-415-96930-7.

- Leff, Samuel; Leff, Vera (1956). From Witchcraft to World Health. London, England: Macmillan.

- Mitchell, Jacqueline S. (February 18, 2003). “The Origins of Science”. Scientific American Frontiers. PBS. Archived from the originalon March 3, 2003. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- “Plato, Apology”. p. 17. Archivedfrom the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- “Plato, Apology”. p. 27. Archivedfrom the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- “Plato, Apology, section 30”. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. 1966. Archivedfrom the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- Nicomachean Ethics (H. Rackham ed.). Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2010. 1139b

- McClellan III, James E.; Dorn, Harold (2015). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN978-1-4214-1776-9.

- Edwards, C.H. Jr. (1979). The Historical Development of the Calculus(First ed.). New York City, New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-387-94313-8.

- Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 190–91. ISBN978-1-85109-539-1.

- Murphy, Trevor Morgan (2004). Pliny the Elder’s Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN9780199262885.

- Doode, Aude (2010). Pliny’s Encyclopedia: The Reception of the Natural History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN9781139484534.

- Smith, A. Mark (June 2004), “What is the History of Medieval Optics Really About?”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 148(2): 180–94, JSTOR 1558283, PMID 15338543

- Lindberg, David C. (2007). “Roman and early medieval science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–162. ISBN978-0-226-48205-7.

- Wildberg, Christian (May 1, 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aristotle, PhysicsII, 3, and Metaphysics V, 2

- Grant, Edward (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge Studies in the History of Science. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–17. ISBN978-0521567626.

- Grant, Edward (2007). “Islam and the eastward shift of Aristotelian natural philosophy”. A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–67. ISBN978-0-521-68957-1.

- The Cambridge history of Iran. Fisher, W.B. (William Bayne). Cambridge: University Press. 1968–1991. ISBN978-0521200936. OCLC 745412.

- “Bayt al-Hikmah”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archivedfrom the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- Klein-Frank, F. Al-Kindi. In Leaman, O & Nasr, H (2001). History of Islamic Philosophy. London: Routledge. p. 165. Felix Klein-Frank (2001) Al-Kindi, pp. 166–67. In Oliver Leaman & Hossein Nasr. History of Islamic Philosophy. London: Routledge.

- “Science in Islam”. Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. 2009.

- Toomer, G.J. (1964). “Reviewed work: Ibn al-Haythams Weg zur Physik, Matthias Schramm”. Isis. 55(4): 463–65. doi:1086/349914. JSTOR 228328. See p. 464: “Schramm sums up [Ibn Al-Haytham’s] achievement in the development of scientific method.”, p. 465: “Schramm has demonstrated .. beyond any dispute that Ibn al-Haytham is a major figure in the Islamic scientific tradition, particularly in the creation of experimental techniques.” p. 465: “only when the influence of ibn al-Haytam and others on the mainstream of later medieval physical writings has been seriously investigated can Schramm’s claim that ibn al-Haytam was the true founder of modern physics be evaluated.”

- Smith 2001:Book I, [6.54]. p. 372

- Selin, H (2006). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 155–156. Bibcode:book…..S. ISBN978-1-4020-4559-2.

- Numbers, Ronald (2009). 9780674057418 Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and ReligionCheck |url= value (help). Harvard University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-674-03327-6.

- Shwayder, Maya (April 7, 2011). “Debunking a myth”. The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- Smith 2001

- McGinnis, Jon (2010). The Canon of Medicine. Oxford University. p. 227.

- Lindberg, David (1992). The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. p. 162. ISBN9780226482040.

- “St. Albertus Magnus | German theologian, scientist, and philosopher”. Archivedfrom the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Smith, A. Mark (2001). “Alhacen’s Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen’s “De aspectibus”, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham’s “Kitāb al-Manāẓir”: Volume One”. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 91(4): i–337. JSTOR 3657358.

- Smith, A. Mark (1981). “Getting the Big Picture in Perspectivist Optics”. Isis. 72(4): 568–89. doi:1086/352843. JSTOR 231249. PMID 7040292.

- Goldstein, Bernard R (2016). “Copernicus and the Origin of his Heliocentric System”. Journal for the History of Astronomy. 33(3): 219–35. doi:1177/002182860203300301.

- Cohen, H. Floris(2010). How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough(Second ed.). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089642394.

- “Galileo and the Birth of Modern Science”. American Heritage of Invention and Technology. 24.

- van Helden, Al (1995). “Pope Urban VIII”. The Galileo Project. Archivedfrom the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- MacTutor Archive, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

- Freudenthal, Gideon; McLaughlin, Peter (May 20, 2009). The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution: Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN9781402096044.

- Thomas G. Bergin (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Renaissance(Oxford and New York: New Market Books, 1987).

- see Hall (1954), iii; Mason (1956), 223.

- Cassels, Alan. Ideology and International Relations in the Modern World. p. 2.

- Ross, Sydney (1962). “Scientist: The story of a word”(PDF). Annals of Science. 18(2): 65–85. doi:1080/00033796200202722. Retrieved March 8, 2011.To be exact, the person who coined the term scientist was referred to in Whewell 1834 only as “some ingenious gentleman.” Ross added a comment that this “some ingenious gentleman” was Whewell himself, without giving the reason for the identification. Ross 1962, p. 72.

- von Bertalanffy, Ludwig (1972). “The History and Status of General Systems Theory”. The Academy of Management Journal. 15(4): 407–26. doi:2307/255139. JSTOR 255139.

- Naidoo, Nasheen; Pawitan, Yudi; Soong, Richie; Cooper, David N.; Ku, Chee-Seng (October 2011). “Human genetics and genomics a decade after the release of the draft sequence of the human genome”. Human Genomics. 5(6): 577–622. doi:1186/1479-7364-5-6-577. PMC 3525251. PMID 22155605.

- Rashid, S. Tamir; Alexander, Graeme J.M. (March 2013). “Induced pluripotent stem cells: from Nobel Prizes to clinical applications”. Journal of Hepatology. 58(3): 625–629. doi:1016/j.jhep.2012.10.026. ISSN 1600-0641. PMID 23131523.

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; Affeldt, C.; Afrough, M.; Agarwal, B.; Agathos, M.; Agatsuma, K.; Aggarwal, N.; Aguiar, O.D.; Aiello, L.; Ain, A.; Ajith, P.; Allen, B.; Allen, G.; Allocca, A.; Altin, P.A.; Amato, A.; Ananyeva, A.; Anderson, S.B.; Anderson, W.G.; Angelova, S.V.; et al. (2017). “Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger”. The Astrophysical Journal. 848(2): L12. arXiv:05833. Bibcode:2017ApJ…848L..12A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa91c9.

- Cho, Adrian (2017). “Merging neutron stars generate gravitational waves and a celestial light show”. Science. doi:1126/science.aar2149.

- “Scientific Method: Relationships Among Scientific Paradigms”. Seed Magazine. March 7, 2007. Archived from the originalon November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 4,2016.

- Bunge, Mario Augusto (1998). Philosophy of Science: From Problem to Theory. Transaction Publishers. p. 24. ISBN978-0-7658-0413-6.

- Popper, Karl R. (2002a) [1959]. “A survey of some fundamental problems”. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. New York, New York: Routledge Classics. pp. 3–26. ISBN978-0-415-27844-7. OCLC 59377149.

- Gauch Jr., Hugh G. (2003). “Science in perspective”. Scientific Method in Practice. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN978-0-52-101708-4.

- Oglivie, Brian W. (2008). “Introduction”. The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe(Paperback ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN978-0-226-62088-6.

- “Natural History”. Princeton University WordNet. Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- Tomalin, Marcus (2006). Linguistics and the Formal Sciences. doi:2277/0521854814.

- Löwe, Benedikt (2002). “The Formal Sciences: Their Scope, Their Foundations, and Their Unity”. Synthese. 133: 5–11. doi:1023/a:1020887832028.

- Bill, Thompson (2007), “2.4 Formal Science and Applied Mathematics”, The Nature of Statistical Evidence, Lecture Notes in Statistics, 189(1st ed.), Springer, p. 15

- Mujumdar, Anshu Gupta; Singh, Tejinder (2016). “Cognitive science and the connection between physics and mathematics”. In Anthony Aguirre; Brendan Foster (eds.). Trick or Truth?: The Mysterious Connection Between Physics and Mathematics. The Frontiers Collection (1st ed.). Switzerland: SpringerNature. pp. 201–218. ISBN978-3-319-27494-2.

- Richard Dawkins (May 10, 2006). “To Live at All Is Miracle Enough”. RichardDawkins.net. Archived from the originalon January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- Stanovich, Keith E. (2007). How to Think Straight About Psychology. Boston: Pearson Education. pp. 106–147. ISBN978-0-205-68590-5.

- “The amazing point is that for the first time since the discovery of mathematics, a method has been introduced, the results of which have an intersubjective value!” (Author’s punctuation)}} —di Francia, Giuliano Toraldo (1976). “The method of physics”. The Investigation of the Physical World. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–52. ISBN978-0-521-29925-1.

- Wilson, Edward (1999). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Vintage. ISBN978-0-679-76867-8.

- Fara, Patricia (2009). “Decisions”. Science: A Four Thousand Year History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 408. ISBN978-0-19-922689-4.

- Nola, Robert; Irzik, Gürol (2005k). “naive inductivism as a methodology in science”. Philosophy, science, education and culture. Science & technology education library. 28. Springer. pp. 207–230. ISBN978-1-4020-3769-6.

- Nola, Robert; Irzik, Gürol (2005j). “The aims of science and critical inquiry”. Philosophy, science, education and culture. Science & technology education library. 28. Springer. pp. 207–230. ISBN978-1-4020-3769-6.

- van Gelder, Tim (1999). “”Heads I win, tails you lose”: A Foray Into the Psychology of Philosophy”(PDF). University of Melbourne. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- Pease, Craig (September 6, 2006). “Chapter 23. Deliberate bias: Conflict creates bad science”. Science for Business, Law and Journalism. Vermont Law School. Archived from the originalon June 19, 2010.

- Shatz, David (2004). Peer Review: A Critical Inquiry. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0-7425-1434-8. OCLC 54989960.

- Krimsky, Sheldon (2003). Science in the Private Interest: Has the Lure of Profits Corrupted the Virtue of Biomedical Research. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0-7425-1479-9. OCLC 185926306.

- Bulger, Ruth Ellen; Heitman, Elizabeth; Reiser, Stanley Joel (2002). The Ethical Dimensions of the Biological and Health Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-00886-0. OCLC 47791316.

- Backer, Patricia Ryaby (October 29, 2004). “What is the scientific method?”. San Jose State University. Archived from the originalon April 8, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- Ziman, John (1978c). “Common observation”. Reliable knowledge: An exploration of the grounds for belief in science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–76. ISBN978-0-521-22087-3.

- Ziman, John (1978c). “The stuff of reality”. Reliable knowledge: An exploration of the grounds for belief in science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–123. ISBN978-0-521-22087-3.

- Popper, Karl R. (2002e) [1959]. “The problem of the empirical basis”. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. New York, New York: Routledge Classics. pp. 3–26. ISBN978-0-415-27844-7. OCLC 59377149.

- “SIAM: Graduate Education for Computational Science and Engineering”. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. Archivedfrom the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003c). “Induction and confirmation”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 39–56. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003o). “Empiricism, naturalism, and scientific realism?”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 219–232. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003b). “Logic plus empiricism”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 19–38. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003d). “Popper: Conjecture and refutation”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 57–74. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003g). “Lakatos, Laudan, Feyerabend, and frameworks”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 102–121. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Popper, Karl (1972). Objective Knowledge.

- “Shut up and multiply”. LessWrong Wiki. September 13, 2015. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Newton-Smith, W.H. (1994). The Rationality of Science. London: Routledge. p. 30. ISBN978-0-7100-0913-5.

- Bird, Alexander (2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). “Thomas Kuhn”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd. ed., Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1970, p. 206. ISBN0-226-45804-0

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003j). “Naturalistic philosophy in theory and practice”. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago. pp. 149–162. ISBN978-0-226-30062-7.

- Brugger, E. Christian (2004). “Casebeer, William D. Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition”. The Review of Metaphysics. 58(2).

- Winther, Rasmus Grønfeldt (2015). “The Structure of Scientific Theories”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Popper, Karl Raimund (1996). In Search of a Better World: Lectures and Essays From Thirty Years. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-13548-1.

- Dawkins, Richard; Coyne, Jerry (September 2, 2005). “One side can be wrong”. The Guardian. London. Archivedfrom the original on December 26, 2013.