Complete the sentences. Use the new words.

square, sea, abroad, thing, hotel, capital, city, letter.

1) What is the first … of the alphabet?

2) It is very interesting to go … and meet new people.

3) The most beautiful … in Moscow is Red … .

4) A lot of people like to go to the … for their holidays.

5) Delhi is a big … in India. It is the … of the country.

6) There is a big new … in the square.

7) The best … for me is to go travelling in the country.

reshalka.com

ГДЗ Английский язык 5 класс (часть 1) Афанасьева. UNIT 1. Step 5. Номер №9

Решение

Перевод задания

Составь предложения, используя новые слова.

площадь, море, за границу, вещь, гостиница, столица, большой город, буква.

1) Какая первая … алфавита?

2) Это очень интересно ездить … и встречать новых людей.

3) Самая красивая … в Москве – это Красная … .

4) Многим людям нравится ездить к … в отпуск.

5) Дели − … в Индии. Это … страны.

6) На площади стоит большая новая … .

7) Самая лучшая … для меня – это путешествовать в другие страны.

ОТВЕТ

1) What is the first letter of the alphabet?

2) It is very interesting to go abroad and meet new people.

3) The most beautiful square in Moscow is Red square.

4) A lot of people like to go to the sea for their holidays.

5) Delhi is a big city in India. It is the capital of the country.

6) There is a big new hotel in the square.

7) The best thing for me is to go travelling in the country.

Перевод ответа

1) Какая первая буква алфавита?

2) Это очень интересно ездить за границу и встречать новых людей.

3) Самая красивая площадь в Москве – это Красная площадь.

4) Многим людям нравится ездить к морю в отпуск.

5) Дели – большой город в Индии. Это столица страны.

6) На площади стоит большая новая гостиница.

7) Самая лучшая вещь для меня – это путешествовать в другие страны.

| English alphabet | |

|---|---|

An English pangram displaying all the characters in context, in FF Dax Regular typeface |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c.1500 to present |

| Languages | English |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

|

Child systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

U+0000 to U+007E Basic Latin and punctuation |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The alphabet for Modern English is a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, each having an upper- and lower-case form. The word alphabet is a compound of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha and beta. The alphabet originated around the 7th century CE to write Old English from Latin script. Since then, letters have been added or removed to give the current letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

The exact shape of printed letters varies depending on the typeface (and font), and the standard printed form may differ significantly from the shape of handwritten letters (which varies between individuals), especially cursive.

The English alphabet has 5 vowels, 19 consonants, and 2 letters (Y and W) that can function as consonants or vowels.

Written English has a large number of digraphs, such as ch, ea, oo, sh, and th. Within the languages used in Europe, English stands out in not normally using diacritics in native words.

Letter names[edit]

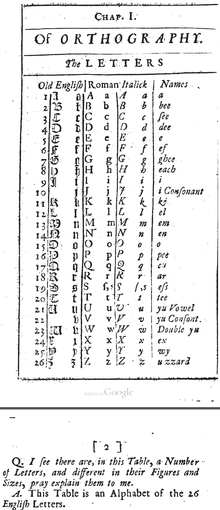

English alphabet from 1740, with some unusual letter names.

The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, etc.), derived forms (e.g., exed out, effing, to eff and blind, aitchless, etc.), and objects named after letters (e.g., en and em in printing, and wye in railroading). The spellings listed below are from the Oxford English Dictionary. Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding -s (e.g., bees, efs or effs, ems) or -es in the cases of aitches, esses, exes. Plurals of vowel names also take -es (i.e., aes, ees, ies, oes, ues), but these are rare. For a letter as a letter, the letter itself is most commonly used, generally in capitalized form, in which case the plural just takes -s or -‘s (e.g. Cs or c’s for cees).

| Letter | Name | Name pronunciation | Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern English | Latin | Modern English | Latin | Old French | Middle English | ||

| A | a | ā | , [nb 1] | /aː/ | /aː/ | /aː/ | 8.17% |

| B | bee | bē | /beː/ | /beː/ | /beː/ | 1.49% | |

| C | cee | cē | /keː/ | /tʃeː/ > /tseː/ > /seː/ | /seː/ | 2.78% | |

| D | dee | dē | /deː/ | /deː/ | /deː/ | 4.25% | |

| E | e | ē | /eː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | 12.70% | |

| F | ef, eff | ef | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | 2.23% | |

| eff as a verb | |||||||

| G | gee | gē | /ɡeː/ | /dʒeː/ | /dʒeː/ | 2.02% | |

| H | aitch | hā | /haː/ > /ˈaha/ > /ˈakːa/ | /ˈaːtʃə/ | /aːtʃ/ | 6.09% | |

| haitch[nb 2] | |||||||

| I | i | ī | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | 6.97% | |

| J | jay | – | – | – | [nb 3] | 0.15% | |

| jy[nb 4] | |||||||

| K | kay | kā | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | 0.77% | |

| L | el, ell[nb 5] | el | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | 4.03% | |

| M | em | em | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | 2.41% | |

| N | en | en | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | 6.75% | |

| O | o | ō | /oː/ | /oː/ | /oː/ | 7.51% | |

| P | pee | pē | /peː/ | /peː/ | /peː/ | 1.93% | |

| Q | cue, kew, kue, que[nb 6] | qū | /kuː/ | /kyː/ | /kiw/ | 0.10% | |

| R | ar | er | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ > /ar/ | 5.99% | |

| or[nb 7] | |||||||

| S | ess | es | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | 6.33% | |

| es- in compounds[nb 8] | |||||||

| T | tee | tē | /teː/ | /teː/ | /teː/ | 9.06% | |

| U | u | ū | /uː/ | /yː/ | /iw/ | 2.76% | |

| V | vee | – | – | – | – | 0.98% | |

| W | double-u | – | [nb 9] | – | – | – | 2.36% |

| X | ex | ex | /ɛks/ | /iks/ | /ɛks/ | 0.15% | |

| ix | /ɪks/ | ||||||

| Y | wy, wye, why[nb 10] | hȳ | /hyː/ | ui, gui ? | /wiː/ | 1.97% | |

| /iː/ | |||||||

| ī graeca | /iː ˈɡraɪka/ | /iː ɡrɛːk/ | |||||

| Z | zed[nb 11] | zēta | /ˈzeːta/ | /ˈzɛːdə/ | /zɛd/ | 0.07% | |

| zee[nb 12] |

Etymology[edit]

The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendants, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See Latin alphabet: Origins.)

The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are:

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /k/ successively to /tʃ/, /ts/, and finally to Middle French /s/. Affects C.

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /ɡ/ to Proto-Romance and Middle French /dʒ/. Affects G.

- fronting of Latin /uː/ to Middle French /yː/, becoming Middle English /iw/ and then Modern English /juː/. Affects Q, U.

- the inconsistent lowering of Middle English /ɛr/ to /ar/. Affects R.

- the Great Vowel Shift, shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y.

The novel forms are aitch, a regular development of Medieval Latin acca; jay, a new letter presumably vocalized like neighboring kay to avoid confusion with established gee (the other name, jy, was taken from French); vee, a new letter named by analogy with the majority; double-u, a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ū); wye, of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French wi; izzard, from the Romance phrase i zed or i zeto «and Z» said when reciting the alphabet; and zee, an American levelling of zed by analogy with other consonants.

Some groups of letters, such as pee and bee, or em and en, are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet, used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other.

Ampersand[edit]

The ampersand (&) has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð’s list of letters in 1011.[1] & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere. An example may be seen in M. B. Moore’s 1863 book The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks.[2] Historically, the figure is a ligature for the letters Et. In English and many other languages, it is used to represent the word and, plus occasionally the Latin word et, as in the abbreviation &c (et cetera).

Archaic letters[edit]

Old and Middle English had a number of non-Latin letters that have since dropped out of use. These either took the names of the equivalent runes, since there were no Latin names to adopt, or (thorn, wyn) were runes themselves.

- Æ æ ash or æsc , used for the vowel , which disappeared from the language and then reformed. Replaced by ae[nb 13] and e now.

- Ð ð edh, eð or eth , and Þ þ thorn or þorn , both used for the consonants and (which did not become phonemically distinct until after these letters had fallen out of use). Replaced by th now.

- Œ œ ethel, ēðel, œ̄þel, etc. , used for the vowel /œ/, which disappeared from the language quite early. Replaced by oe[nb 14] and e now.

- Ƿ ƿ wyn, ƿen or wynn , used for the consonant . (The letter ‘w’ had not yet been invented.) Replaced by w now.

- Ȝ ȝ yogh, ȝogh or yoch or , used for various sounds derived from , such as and . Replaced by y, j[nb 15] and ch[nb 16] now.

- ſ long s, an earlier form of the lowercase «s» that continued to be used alongside the modern lowercase s into the 1800s. Replaced by lowercase s now.

Diacritics[edit]

The most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç).[3] Diacritics used for tonal languages may be replaced with tonal numbers or omitted.

Loanwords[edit]

Diacritic marks mainly appear in loanwords such as naïve and façade. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them.

As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as hôtel. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of soupçon found in English dictionaries (the OED and others) uses the diacritic. However, diacritics are likely to be retained even in naturalised words where they would otherwise be confused with a common native English word (for example, résumé rather than resume).[4] Rarely, they may even be added to a loanword for this reason (as in maté, from Spanish yerba mate but following the pattern of café, from French, to distinguish from mate).

Native English words[edit]

Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the syllables of a word: cursed (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while cursèd (adjective) is pronounced with two. For this, è is used widely in poetry, e.g., in Shakespeare’s sonnets. J.R.R. Tolkien used ë, as in O wingëd crown.

Similarly, while in chicken coop the letters -oo- represent a single vowel sound (a digraph), they less often represent two which may be marked with a diaresis as in zoölogist[5] and coöperation. This use of the diaeresis is rare but found in some well-known publications, such as MIT Technology Review and The New Yorker. Some publications, particularly in UK usage, have replaced the diaeresis with a hyphen such as in co-operative.[citation needed]

In general, these devices are not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion.

Punctuation marks within words[edit]

Apostrophe[edit]

The apostrophe (ʼ) is not considered part of the English alphabet nor used as a diacritic, even in loanwords. But it is used for two important purposes in written English: to mark the «possessive»[nb 17] and to mark contracted words. Current standards require its use for both purposes. Therefore, apostrophes are necessary to spell many words even in isolation, unlike most punctuation marks, which are concerned with indicating sentence structure and other relationships among multiple words.

- It distinguishes (from the otherwise identical regular plural inflection -s) the English possessive morpheme ‘s (apostrophe alone after a regular plural affix, giving -s’ as the standard mark for plural + possessive). Practice settled in the 18th century; before then, practices varied but typically all three endings were written -s (but without cumulation). This meant that only regular nouns bearing neither could be confidently identified, and plural and possessive could be potentially confused (e.g., «the Apostles words»; «those things over there are my husbands»[6])—which undermines the logic of «marked» forms.

- Most common contractions have near-homographs from which they are distinguished in writing only by an apostrophe, for example it’s (it is or it has), or she’d (she would or she had).

In a Chronicle of Higher Education blog, Geoffrey Pullum argued that apostrophe should be considered a 27th letter of the alphabet, arguing that it is not a form of punctuation.[7]

Hyphen[edit]

Hyphens are often used in English compound words. Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by stylistic policy. Some writers may use a slash in certain instances.

Frequencies[edit]

The letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. The frequencies shown in the table may differ in practice according to the type of text.[8]

Phonology[edit]

The letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent vowels, although I and U represent consonants in words such as «onion» and «quail» respectively.

The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant (as in «young») and sometimes a vowel (as in «myth»). Very rarely, W may represent a vowel (as in «cwm», a Welsh loanword).

The consonant sounds represented by the letters W and Y in English (/w/ and /j/ as in yes /jɛs/ and went /wɛnt/) are referred to as semi-vowels (or glides) by linguists, however this is a description that applies to the sounds represented by the letters and not to the letters themselves.

The remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent consonants.

History[edit]

Old English[edit]

The English language itself was first written in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by Anglo-Saxon settlers. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments.

The Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. As such, the Old English alphabet began to employ parts of the Roman alphabet in its construction.[9] Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters thorn (Þ þ) and wynn (Ƿ ƿ). The letter eth (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of dee (D d), and finally yogh (Ȝ ȝ) was created by Norman scribes from the insular g in Old English and Irish, and used alongside their Carolingian g.

The a-e ligature ash (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune æsc. In very early Old English the o-e ligature ethel (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, œðel[citation needed]. Additionally, the v-v or u-u ligature double-u (W w) was in use.

In the year 1011, a monk named Byrhtferð recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.[1] He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first, including the ampersand, then 5 additional English letters, starting with the Tironian note ond (⁊), an insular symbol for and:

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ

Modern English[edit]

In the orthography of Modern English, the letters thorn (þ), eth (ð), wynn (ƿ), yogh (ȝ), ash (æ), and ethel (œ) are obsolete. Latin borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into Middle English and Early Modern English, though they are largely obsolete (see «Ligatures in recent usage» below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ligatures. Thorn and eth were both replaced by th, though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the minuscule y in most handwriting. Y for th can still be seen in pseudo-archaisms such as «Ye Olde Booke Shoppe». The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day Icelandic (where they now represent two separate sounds, /θ/ and /ð/ having become phonemically-distinct — as indeed also happened in Modern English), while ð is still used in present-day Faroese (although only as a silent letter). Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by uu, which ultimately developed into the modern w. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by gh.

The letters u and j, as distinct from v and i, were introduced in the 16th century, and w assumed the status of an independent letter. The variant lowercase form long s (ſ) lasted into early modern English, and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. Today, the English alphabet is considered to consist of the following 26 letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

Written English has a number of digraphs,[10] but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet:

- ch (usually makes tsh sound)

- ci (makes s sound)

- ck (makes k sound)

- gh (makes f or g sound (also silent))

- ng (makes a voiced velar nasal)

- ph (makes f sound)

- qu (makes kw sound)

- rh (makes r sound)

- sc (makes s sound (also a blend)[clarification needed])

- sh (makes ch sound without t)

- th (makes theta or eth sound)

- ti (makes sh sound)

- wh (makes w sound)

- wr (makes r sound)

- zh (makes j sound without d)

Ligatures in recent usage[edit]

Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in loanwords, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. The ligatures æ and œ were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English)[citation needed] used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as encyclopædia and cœlom, although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as «ae» and «oe» in all types of writing,[citation needed] although in American English, a lone e has mostly supplanted both (for example, encyclopedia for encyclopaedia, and maneuver for manoeuvre).

Some fonts for typesetting English contain commonly used ligatures, such as for ⟨tt⟩, ⟨fi⟩, ⟨fl⟩, ⟨ffi⟩, and ⟨ffl⟩. These are not independent letters, but rather allographs.

Proposed reforms[edit]

There have been a number of proposals to extend or replace the basic English alphabet. These include proposals for the addition of letters to the English alphabet, such as eng or engma (Ŋ ŋ), used to replace the digraph «ng» and represent the voiced velar nasal sound with a single letter. Benjamin Franklin’s phonetic alphabet, based on the Latin alphabet, introduced a number of new letters as part of a wider proposal to reform English orthography. Other proposals have gone further, proposing entirely new scripts for written English to replace the Latin alphabet such as the Deseret alphabet and the Shavian alphabet.

See also[edit]

- Alphabet song

- NATO phonetic alphabet

- English orthography

- English-language spelling reform

- American manual alphabet

- Two-handed manual alphabets

- English Braille

- American Braille

- New York Point

- Chinese respelling of the English alphabet

- Burmese respelling of the English alphabet

- Base36

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ often in Hiberno-English, due to the letter’s pronunciation in the Irish language

- ^ The usual form in Hiberno-English and Australian English

- ^ The letter J did not occur in Old French or Middle English. The Modern French name is ji /ʒi/, corresponding to Modern English jy (rhyming with i), which in most areas was later replaced with jay (rhyming with kay).

- ^ in Scottish English

- ^ In the US, an L-shaped object may be spelled ell.

- ^ One of the few letter names commonly spelled without the letter in question.

- ^ in Hiberno-English

- ^ in compounds such as es-hook

- ^ Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are , , and (as in the nickname «Dubya») or just , especially in terms like www.

- ^ why is a homophone of y

- ^ in British English, Hiberno-English and Commonwealth English

- ^ in American English, Newfoundland English and Philippine English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in words like hallelujah

- ^ in words like loch in Scottish English

- ^ Linguistic analyses vary on how best to characterise the English possessive morpheme -‘s: a noun case inflectional suffix distinct to possession, a genitive case inflectional suffix equivalent to prepositional periphrastic of X (or rarely for X), an edge inflection that uniquely attaches to a noun phrase’s final (rather than head) word, or an enclitic postposition.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, On the Status of the Latin Letter Þorn and of its Sorting Order

- ^ «The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks». Branson, Farrar & Co., Raleigh NC.

- ^ Strizver, Ilene, «Accents & Accented Characters», Fontology, Monotype Imaging, retrieved 2019-06-17

- ^ Modern Humanities Research Association (2013), MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors and Editors (pdf) (3rd ed.), London, Section 2.2, ISBN 978-1-78188-009-8, retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ Zoölogist, Minnesota Office of the State (1892). Report of the State Zoölogist.

- ^ Kingsley Amis quoted in Jane Fyne, «Little Things that Matter,» Courier Mail (2007-04-26) Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ^ Pullum, Geoffrey K. (March 22, 2013). «Being an apostrophe (Lingua Franca post)». Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ Beker, Henry; Piper, Fred (1982). Cipher Systems: The Protection of Communications. Wiley-Interscience. p. 397. Table also available from

Lewand, Robert (2000). Cryptological Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 36. ISBN 978-0883857199. and «English letter frequencies». Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2008-06-25. - ^ Shaw, Phillip (May 2013). «Adapting the Roman alphabet for Writing Old English: Evidence from Coin Epigraphy and Single-Sheet Characters». 21: 115–139 – via Ebscohost.

- ^ «Digraphs (Phonics on the Web)». phonicsontheweb.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

Further reading[edit]

- Michael Rosen (2015). Alphabetical: How Every Letter Tells a Story. Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1619027022.

- Upward, Christopher; Davidson, George (2011), The History of English Spelling, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9024-4, LCCN 2011008794.

- Текст

- Веб-страница

1 What is the first letter of the alphabet?

2 It is very interesting to go abroad and meet new people

3 The most beautiful thing in Moscow is Red square

4 A lot of people like to go to the sea for their holidays

5 Delhi is a big city in India. It is the capital of the country

6 There is a big new hotel in the square

7 The best thing for me is to go travelling in the country

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

1 What is the first letter of the alphabet? 2 It is very interesting to go abroad and meet new people 3 The most beautiful thing in Moscow is Red square 4 A lot of people like to go to the sea for their holidays 5 Delhi is a big city in India. It is the capital of the country 6 There is a big new hotel in the square 7 The best thing for me is to go travelling in the country

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

1 Что такое первая буква алфавита?

2 Это очень интересно поехать за границу и познакомиться с новыми людьми

3 Самое прекрасное в Москве Красная площадь

4 много людей хотели бы поехать на море в отпуск

5-Дели является большой город в Индии. Он является столицей страны

6 Существует большой новый отель на площади

7 Самое лучшее для меня, чтобы отправиться в путешествие в страны

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

1 — первая буква алфавита?

2, это очень интересно, чтобы поехать за границу и познакомиться с новыми людьми

3 — самая прекрасная вещь в москве красная площадь

4 много людей хотели бы поехать к морю, на каникулы: 5 — дели — большой город в индии.это столица страны

6 есть большой новый отель на площади

7 лучшая вещь для меня — это путешествие в страну

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- мой любимый сезон лето.

- Число 3 , я всегда выбираю это число ког

- Ширшова Наталья

- Меня зовут Екатерина. Мне 18 лет. Я живу

- мой любимый сезон лето.

- you dhave not help me

- Ширшова Наталья

- Happy teddy day, go buy some teddies

- семичасовой рабочий день

- For example, every family may need to gi

- is there some bakers

- Делать домашние задание

- семичасовой рабочий день

- вчерашняя газета

- Would it be possible to change/switch se

- Делать домашние задание

- Get it

- Хочу и буду

- die mädchen

- Это мальчиков куртка

- is there a bakers

- Не верьте тем, кто говорит, что работа п

- Он всегда фотографирует, когда путешеств

- я живу в городе домодедово

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Writing systems |

|---|

| History |

| Types |

| Alphabet |

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Syllabary |

| Logogram |

| Related |

| Pictogram |

| Ideogram |

An alphabet is a standard set of letters (basic written symbols or graphemes) which is used to write one or more languages based on the general principle that the letters represent phonemes (basic significant sounds) of the spoken language. This is in contrast to other types of writing systems, such as syllabaries (in which each character represents a syllable) and logographies (in which each character represents a word, morpheme or semantic unit). The use of alphabets supports efforts to achieve universal literacy, which is a high priority in contemporary society, through the greater ease of learning a limited number of letters compared to the large numbers of symbols involved in logographies.

A true alphabet has letters for the vowels of a language as well as the consonants. The first «true alphabet» in this sense is believed to be the Greek alphabet, which is a modified form of the Phoenician alphabet. In other types of alphabet either the vowels are not indicated at all, as was the case in the Phoenician alphabet (such systems are known as abjads), or else the vowels are shown by diacritics or modification of consonants, as in the devanagari used in India and Nepal (these systems are known as abugidas or alphasyllabaries).

There are dozens of alphabets in use today, the most popular being the Latin alphabet (which was derived from the Greek). Many languages use modified forms of the Latin alphabet, with additional letters formed using diacritical marks. While most alphabets have letters composed of lines (linear writing), there are also exceptions such as the alphabets used in Braille and Morse code.

Alphabets are usually associated with a standard ordering of their letters. This makes them useful for purposes of collation, specifically by allowing words to be sorted in alphabetical order. It also means that their letters can be used as an alternative method of «numbering» ordered items, in such contexts as numbered lists.

Etymology

The English word alphabet came into Middle English from the Late Latin word alphabetum, which in turn originated in the Greek ἀλφάβητος (alphabētos), from alpha and beta, the first two letters of the Greek alphabet. Alpha and beta in turn came from the first two letters of the Phoenician alphabet, and originally meant ox and house respectively.

History

The history of alphabetic writing goes back to the consonantal writing system used for Semitic languages in the Levant in the second millennium B.C.E. Most or nearly all alphabetic scripts used throughout the world today ultimately go back to this Semitic proto-alphabet.[1] Its first origins can be traced back to a Proto-Sinaitic script developed in Ancient Egypt to represent the language of Semitic-speaking workers in Egypt. This script was partly influenced by the older Egyptian hieratic, a cursive script related to Egyptian hieroglyphs.[2]

[3]

Although the following description presents the evolution of scripts in a linear fashion, this is a simplification. For example, the Manchu alphabet, descended from the abjads of West Asia, was also influenced by Korean hangul, which was either independent (the traditional view) or derived from the abugidas of South Asia. Georgian apparently derives from the Aramaic family, but was strongly influenced in its conception by Greek. The Greek alphabet, itself ultimately a derivative of hieroglyphs through that first Semitic alphabet, later adopted an additional half dozen demotic hieroglyphs when it was used to write Coptic Egyptian.

The Beginnings in Egypt

By 2700 B.C.E. the ancient Egyptians had developed a set of some 22 hieroglyphs to represent the individual consonants of their language, plus a 23rd that seems to have represented word-initial or word-final vowels. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names. However, although alphabetic in nature, the system was not used for purely alphabetic writing. That is, while capable of being used as an alphabet, it was in fact always used with a strong logographic component, presumably due to strong cultural attachment to the complex Egyptian script.

The Middle Bronze Age scripts of Egypt have yet to be deciphered. However, they appear to be at least partially, and perhaps completely, alphabetic. The oldest examples are found as graffiti from central Egypt and date to around 1800 B.C.E.[4][5][2] These inscriptions, according to Gordon J. Hamilton, help to show that the most likely place for the alphabet’s invention was in Egypt proper.[6]

The first purely alphabetic script is thought to have been developed by 2000 B.C.E. for Semitic workers in central Egypt. Over the next five centuries it spread north, and all subsequent alphabets around the world have either descended from it, or been inspired by one of its descendants, with the possible exception of the Meroitic alphabet, a third century B.C.E. adaptation of hieroglyphs in Nubia to the south of Egypt.

Middle Eastern scripts

A specimen of Proto-Sinaitic script, one of the earliest (if not the very first) phonemic scripts

The apparently «alphabetic» system known as the Proto-Sinaitic script appears in Egyptian turquoise mines in the Sinai peninsula dated to the fifteenth century B.C.E., apparently left by Canaanite workers. An even earlier version of this first alphabet was discovered at Wadi el-Hol and dated to circa 1800 B.C.E. This alphabet showed evidence of having been adapted from specific forms of Egyptian hieroglyphs dated to circa 2000 B.C.E., suggesting that the first alphabet had been developed around that time.[7] Based on letter appearances and names, it is believed to be based on Egyptian hieroglyphs.[8] This script had no characters representing vowels. An alphabetic cuneiform script with 30 signs including three which indicate the following vowel was invented in Ugarit before the fifteenth century B.C.E. This script was not used after the destruction of Ugarit.[9]

This Semitic script did not restrict itself to the existing Egyptian consonantal signs, but incorporated a number of other Egyptian hieroglyphs, for a total of perhaps thirty, and used Semitic names for them.[10] However, by the time the script was inherited by the Canaanites, it was purely alphabetic. For example, the hieroglyph originally representing «house» stood only for b.[10]

The Proto-Sinaitic script eventually developed into the Phoenician alphabet, which is conventionally called «Proto-Canaanite» before 1050 B.C.E.[11] The oldest text in Phoenician script is an inscription on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram. This script is the parent script of all western alphabets. By the tenth century two other forms can be distinguished namely Canaanite and Aramaic, which then gave rise to Hebrew.[8] The South Arabian alphabet, a sister script to the Phoenician alphabet, is the script from which the Ge’ez alphabet (an abugida) is descended.

The Proto-Sinatic or Proto Canaanite script and the Ugaritic script were the first scripts with limited number of signs, in contrast to the other widely used writing systems at the time, Cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Linear B. The Phoenician script was probably the first phonemic script[8][11] and it contained only about two dozen distinct letters, making it a script simple enough for common traders to learn. Another advantage of Phoenician was that it could be used to write down many different languages, since it recorded words phonemically.

The script was spread by the Phoenicians across the Mediterranean.[11] In Greece, it was modified to add the vowels, giving rise to the ancestor of all alphabets in the West. The Greeks took letters which did not represent sounds that existed in Greek, and changed them to represent the vowels. The syllabical Linear B script which was used by the Mycenaean Greeks from the sixteenth century B.C.E. had 87 symbols including 5 vowels. In its early years, there were many variants of the Greek alphabet, a situation which caused many different alphabets to evolve from it.

Descendants of the Aramaic abjad

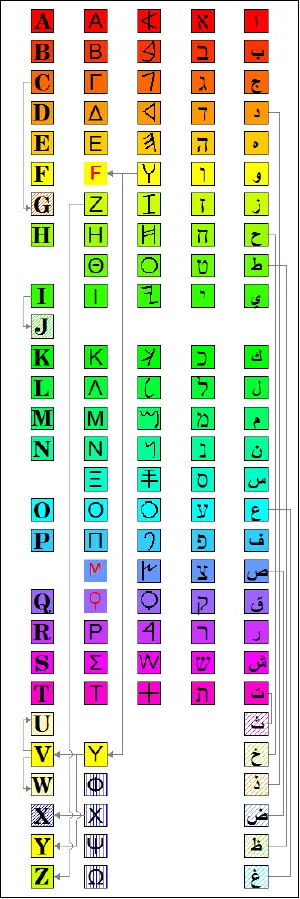

Chart showing details of four alphabets’ descent from Phoenician abjad, from left to right Latin, Greek, original Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic.

The Phoenician and Aramaic alphabets, like their Egyptian prototype, represented only consonants, a system called an abjad. The Aramaic alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician in the seventh century B.C.E. as the official script of the Persian Empire, appears to be the ancestor of nearly all the modern alphabets of Asia:

- The modern Hebrew alphabet started out as a local variant of Imperial Aramaic. (The original Hebrew alphabet has been retained by the Samaritans.)[10] [12]

- The Arabic alphabet descended from Aramaic via the Nabatean alphabet of what is now southern Jordan.

- The Syriac alphabet used after the third century C.E. evolved, through Pahlavi and Sogdian, into the alphabets of northern Asia, such as Orkhon (probably), Uyghur, Mongolian, and Manchu.

- The Georgian alphabet is of uncertain provenance, but appears to be part of the Persian-Aramaic (or perhaps the Greek) family.

- The Aramaic alphabet is also the most likely ancestor of the Brahmic alphabets of the Indian subcontinent, which spread to Tibet, Mongolia, Indochina, and the Malay archipelago along with the Hindu and Buddhist religions. (China and Japan, while absorbing Buddhism, were already literate and retained their logographic and syllabic scripts.)

European alphabets

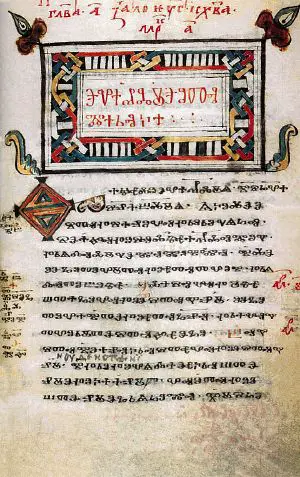

Codex Zographensis in the Glagolitic alphabet from Medieval Bulgaria

A true alphabet has letters for the vowels of a language as well as the consonants. The first «true alphabet» in this sense is believed to be the Greek alphabet which was modified from the Phoenician alphabet to include vowels.[8][13]

The Greek alphabet was then carried over by Greek colonists to the Italian peninsula, where it gave rise to a variety of alphabets used to write the Italic languages. One of these became the Latin alphabet, which was spread across Europe as the Romans expanded their empire. Even after the fall of the Roman state, the alphabet survived in intellectual and religious works. It eventually became used for the descendant languages of Latin (the Romance languages) and then for most of the other languages of Europe.

Greek Alphabet

By at least the eighth century B.C.E. the Greeks had borrowed the Phoenician alphabet and adapted it to their own language.[14] The letters of the Greek alphabet are the same as those of the Phoenician alphabet, and both alphabets are arranged in the same order. However, whereas separate letters for vowels would have actually hindered the legibility of Egyptian, Phoenician, or Hebrew, their absence was problematic for Greek, where vowels played a much more important role. The Greeks chose Phoenician letters representing sounds that did not exist in Greek to represent their vowels. For example, the Greeks had no glottal stop or h, so the Phoenician letters ’alep and he became Greek alpha and e (later renamed epsilon), and stood for the vowels /a/ and /e/ rather than the Phoenician consonants. This provided for five or six (depending on dialect) of the twelve Greek vowels, and so the Greeks eventually created digraphs and other modifications, such as ei, ou, and o (which became omega), or in some cases simply ignored the deficiency, as in long a, i, u.[12]

Several varieties of the Greek alphabet developed. One, known as Western Greek or Chalcidian, was west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other variation, known as Eastern Greek, was used in present-day Turkey, and the Athenians, and eventually the rest of the world that spoke Greek, adopted this variation. After first writing right to left, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to right, unlike the Phoenicians who wrote from right to left.[15]

Latin Alphabet

A tribe known as the Latins, who became known as the Romans, also lived in the Italian peninsula like the Western Greeks. From the Etruscans, a tribe living in the first millennium B.C.E. in central Italy, and the Western Greeks, the Latins adopted writing in about the fifth century. In adopted writing from these two groups, the Latins dropped four characters from the Western Greek alphabet. They also adapted the Etruscan letter F, pronounced ‘w,’ giving it the ‘f’ sound, and the Etruscan S, which had three zigzag lines, was curved to make the modern S. To represent the G sound in Greek and the K sound in Etruscan, the Gamma was used. These changes produced the modern alphabet without the letters G, J, U, W, Y, and Z, as well as some other differences.[15]

Over the few centuries after Alexander the Great conquered the Eastern Mediterranean and other areas in the third century B.C.E., the Romans began to borrow Greek words, so they had to adapt their alphabet again in order to write these words. From the Eastern Greek alphabet, they borrowed Y and Z, which were added to the end of the alphabet because the only time they were used was to write Greek words.[15]

When the Anglo-Saxon language began to be written using Roman letters after Britain was invaded by the Normans in the eleventh century further modifications were made: W was placed in the alphabet by V. U developed when people began to use the rounded U when they meant the vowel u and the pointed V when the meant the consonant V. J began as a variation of I, in which a long tail was added to the final I when there were several in a row. People began to use the J for the consonant and the I for the vowel by the fifteenth century, and it was fully accepted in the mid-seventeenth century.[15]

Some adaptations of the Latin alphabet are augmented with ligatures, such as æ in Old English and Icelandic and Ȣ in Algonquian; by borrowings from other alphabets, such as the thorn þ in Old English and Icelandic, which came from the Futhark runes; and by modifying existing letters, such as the eth ð of Old English and Icelandic, which is a modified d. Other alphabets only use a subset of the Latin alphabet, such as Hawaiian, and Italian, which uses the letters j, k, x, y and w only in foreign words.

Other

Another notable script is Elder Futhark, which is believed to have evolved out of one of the Old Italic alphabets. Elder Futhark gave rise to a variety of alphabets known collectively as the Runic alphabets. The Runic alphabets were used for Germanic languages from 100 C.E. to the late Middle Ages. Its usage is mostly restricted to engravings on stone and jewelry, although inscriptions have also been found on bone and wood. These alphabets have since been replaced with the Latin alphabet, except for decorative usage for which the runes remained in use until the twentieth century.

The Old Hungarian script is a contemporary writing system of the Hungarians. It was in use during the entire history of Hungary, albeit not as an official writing system. From the nineteenth century it once again became more popular.

The Glagolitic alphabet was the initial script of the liturgical language Old Church Slavonic and became, together with the Greek uncial script, the basis of the Cyrillic script. Cyrillic is one of the most widely used modern alphabetic scripts, and is notable for its use in Slavic languages and also for other languages within the former Soviet Union. Cyrillic alphabets include the Serbian, Macedonian, Bulgarian, and Russian alphabets. The Glagolitic alphabet is believed to have been created by Saints Cyril and Methodius, while the Cyrillic alphabet was invented by the Bulgarian scholar Clement of Ohrid, who was their disciple. They feature many letters that appear to have been borrowed from or influenced by the Greek alphabet and the Hebrew alphabet.

Asian alphabets

Beyond the logographic Chinese writing, many phonetic scripts are in existence in Asia. The Arabic alphabet, Hebrew alphabet, Syriac alphabet, and other abjads of the Middle East are developments of the Aramaic alphabet, but because these writing systems are largely consonant-based they are often not considered true alphabets.

Most alphabetic scripts of India and Eastern Asia are descended from the Brahmi script, which is often believed to be a descendant of Aramaic.

Zhuyin (sometimes called Bopomofo) is a semi-syllabary used to phonetically transcribe Mandarin Chinese in the Republic of China. After the later establishment of the People’s Republic of China and its adoption of Hanyu Pinyin, the use of Zhuyin today is limited, but it is still widely used in Taiwan where the Republic of China still governs. Zhuyin developed out of a form of Chinese shorthand based on Chinese characters in the early 1900s and has elements of both an alphabet and a syllabary. Like an alphabet the phonemes of syllable initials are represented by individual symbols, but like a syllabary the phonemes of the syllable finals are not; rather, each possible final (excluding the medial glide) is represented by its own symbol. For example, luan is represented as ㄌㄨㄢ (l-u-an), where the last symbol ㄢ represents the entire final -an. While Zhuyin is not used as a mainstream writing system, it is still often used in ways similar to a romanization system—that is, for aiding in pronunciation and as an input method for Chinese characters on computers and cellphones.

In Korea, the Hangul alphabet was created by Sejong the Great[16] Hangul is a unique alphabet: it is a featural alphabet, where many of the letters are designed from a sound’s place of articulation (for example P to look like the widened mouth, L to look like the tongue pulled in); its design was planned by the government of the day; and it places individual letters in syllable clusters with equal dimensions (one syllable always takes up one type-space no matter how many letters get stacked into building that one sound-block).

European alphabets, especially Latin and Cyrillic, have been adapted for many languages of Asia. Arabic is also widely used, sometimes as an abjad (as with Urdu and Persian) and sometimes as a complete alphabet (as with Kurdish and Uyghur).

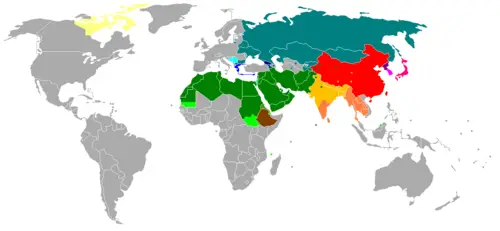

Types

Alphabets: Armenian , Cyrillic , Georgian , Greek , Latin , Latin (and Arabic) , Latin and Cyrillic

Abjads: Arabic , Hebrew

Abugidas: North Indic , South Indic , Ge’ez , Tāna , Canadian Syllabic and Latin

Logographic+syllabic: Pure logographic , Mixed logographic and syllabaries , Featural-alphabetic syllabary + limited logographic , Featural-alphabetic syllabary

The term «alphabet» is used by linguists and paleographers in both a wide and a narrow sense. In the wider sense, an alphabet is a script that is segmental at the phoneme level—that is, it has separate glyphs for individual sounds and not for larger units such as syllables or words. In the narrower sense, some scholars distinguish «true» alphabets from two other types of segmental script, abjads and abugidas. These three differ from each other in the way they treat vowels: abjads have letters for consonants and leave most vowels unexpressed; abugidas are also consonant-based, but indicate vowels with diacritics to or a systematic graphic modification of the consonants. In alphabets in the narrow sense, on the other hand, consonants and vowels are written as independent letters. The earliest known alphabet in the wider sense is the Wadi el-Hol script, believed to be an abjad, which through its successor Phoenician is the ancestor of modern alphabets, including Arabic, Greek, Latin (via the Old Italic alphabet), Cyrillic (via the Greek alphabet) and Hebrew (via Aramaic).

Examples of present-day abjads are the Arabic and Hebrew scripts; true alphabets include Latin, Cyrillic, and Korean hangul; and abugidas are used to write Tigrinya, Amharic, Hindi, and Thai. The Canadian Aboriginal syllabics are also an abugida rather than a syllabary as their name would imply, since each glyph stands for a consonant which is modified by rotation to represent the following vowel. (In a true syllabary, each consonant-vowel combination would be represented by a separate glyph.)

All three types may be augmented with syllabic glyphs. Ugaritic, for example, is basically an abjad, but has syllabic letters for /ʔa, ʔi, ʔu/. (These are the only time vowels are indicated.) Cyrillic is basically a true alphabet, but has syllabic letters for /ja, je, ju/ (я, е, ю); Coptic has a letter for /ti/. Devanagari is typically an abugida augmented with dedicated letters for initial vowels, though some traditions use अ as a zero consonant as the graphic base for such vowels.

The boundaries between the three types of segmental scripts are not always clear-cut. For example, Sorani Kurdish is written in the Arabic script, which is normally an abjad. However, in Kurdish, writing the vowels is mandatory, and full letters are used, so the script is a true alphabet. Other languages may use a Semitic abjad with mandatory vowel diacritics, effectively making them abugidas. On the other hand, the Phagspa script of the Mongol Empire was based closely on the Tibetan abugida, but all vowel marks were written after the preceding consonant rather than as diacritic marks. Although short a was not written, as in the Indic abugidas, one could argue that the linear arrangement made this a true alphabet. Conversely, the vowel marks of the Tigrinya abugida and the Amharic abugida (ironically, the original source of the term «abugida») have been so completely assimilated into their consonants that the modifications are no longer systematic and have to be learned as a syllabary rather than as a segmental script. Even more extreme, the Pahlavi abjad eventually became logographic. (See below.)

Thus the primary classification of alphabets reflects how they treat vowels. For tonal languages, further classification can be based on their treatment of tone, though names do not yet exist to distinguish the various types. Some alphabets disregard tone entirely, especially when it does not carry a heavy functional load, as in Somali and many other languages of Africa and the Americas. Such scripts are to tone what abjads are to vowels. Most commonly, tones are indicated with diacritics, the way vowels are treated in abugidas. This is the case for Vietnamese (a true alphabet) and Thai (an abugida). In Thai, tone is determined primarily by the choice of consonant, with diacritics for disambiguation. In the Pollard script, an abugida, vowels are indicated by diacritics, but the placement of the diacritic relative to the consonant is modified to indicate the tone. More rarely, a script may have separate letters for tones, as is the case for Hmong and Zhuang. For most of these scripts, regardless of whether letters or diacritics are used, the most common tone is not marked, just as the most common vowel is not marked in Indic abugidas; in Zhuyin not only is one of the tones unmarked, but there is a diacritic to indicate lack of tone, like the virama of Indic.

The number of letters in an alphabet can be quite small. The Book Pahlavi script, an abjad, had only twelve letters at one point, and may have had even fewer later on. Today the Rotokas alphabet has only twelve letters. (The Hawaiian alphabet is sometimes claimed to be as small, but it actually consists of 18 letters, including the ʻokina and five long vowels.) While Rotokas has a small alphabet because it has few phonemes to represent (just eleven), Book Pahlavi was small because many letters had been conflated—that is, the graphic distinctions had been lost over time, and diacritics were not developed to compensate for this as they were in Arabic, another script that lost many of its distinct letter shapes. For example, a comma-shaped letter represented g, d, y, k, or j. However, such apparent simplifications can perversely make a script more complicated. In later Pahlavi papyri, up to half of the remaining graphic distinctions of these twelve letters were lost, and the script could no longer be read as a sequence of letters at all, but instead each word had to be learned as a whole—that is, they had become logograms as in Egyptian Demotic. The alphabet in the Polish language contains 32 letters.

The largest segmental script is probably an abugida, Devanagari. When written in Devanagari, Vedic Sanskrit has an alphabet of 53 letters, including the visarga mark for final aspiration and special letters for kš and jñ, though one of the letters is theoretical and not actually used. The Hindi alphabet must represent both Sanskrit and modern vocabulary, and so has been expanded to 58 with the khutma letters (letters with a dot added) to represent sounds from Persian and English.

The largest known abjad is Sindhi, with 51 letters. The largest alphabets in the narrow sense include Kabardian and Abkhaz (for Cyrillic), with 58 and 56 letters, respectively, and Slovak (for the Latin script), with 46. However, these scripts either count di- and tri-graphs as separate letters, as Spanish did with ch and ll until recently, or uses diacritics like Slovak č. The largest true alphabet where each letter is graphically independent is probably Georgian, with 41 letters.

Syllabaries typically contain 50 to 400 glyphs, and the glyphs of logographic systems typically number from the many hundreds into the thousands. Thus a simple count of the number of distinct symbols is an important clue to the nature of an unknown script.

Names of letters

The Phoenician letter names, in which each letter was associated with a word that begins with that sound, continue to be used to varying degrees in Samaritan, Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek and Arabic. The names were abandoned in Latin, which instead referred to the letters by adding a vowel (usually e) before or after the consonant (the exception is zeta, which was retained from Greek). In Cyrillic originally the letters were given names based on Slavic words; this was later abandoned as well in favor of a system similar to that used in Latin.

Orthography and pronunciation

When an alphabet is adopted or developed for use in representing a given language, an orthography generally comes into being, providing rules for the spelling of words in that language. In accordance with the principle on which alphabets are based, these rules will generally map letters of the alphabet to the phonemes (significant sounds) of the spoken language. In a perfectly phonemic orthography there would be a consistent one-to-one correspondence between the letters and the phonemes, so that a writer could predict the spelling of a word given its pronunciation, and a speaker could predict the pronunciation of a word given its spelling. However this ideal is not normally achieved in practice; some languages (such as Spanish and Finnish) come close to it, while others (such as English) deviate from it to a much larger degree.

Languages may fail to achieve a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds in any of several ways:

- A language may represent a given phoneme with a combination of letters rather than just a single letter. Two-letter combinations are called digraphs and three-letter groups are called trigraphs. German uses the tesseragraphs (four letters) «tsch» for the phoneme German pronunciation: [tʃ] and «dsch» for [dʒ], although the latter is rare. Kabardian also uses a tesseragraph for one of its phonemes, namely «кхъу». Two letters representing one sound is widely used in Hungarian as well (where, for instance, cs stands for [č], sz for [s], zs for [ž], dzs for [ǰ], etc.).

- A language may represent the same phoneme with two different letters or combinations of letters. An example is modern Greek which may write the phoneme Template:IPA-el in six different ways: ⟨ι⟩, ⟨η⟩, ⟨υ⟩, ⟨ει⟩, ⟨οι⟩, and ⟨υι⟩ (although the last is rare).

- A language may spell some words with unpronounced letters that exist for historical or other reasons. For example, the spelling of the Thai word for «beer» [เบียร์] retains a letter for the final consonant «r» present in the English word it was borrowed from, but silences it.

- Pronunciation of individual words may change according to the presence of surrounding words in a sentence (sandhi).

- Different dialects of a language may use different phonemes for the same word.

- A language may use different sets of symbols or different rules for distinct sets of vocabulary items, such as the Japanese hiragana and katakana syllabaries, or the various rules in English for spelling words from Latin and Greek, or the original Germanic vocabulary.

National languages generally elect to address the problem of dialects by simply associating the alphabet with the national standard. However, with an international language with wide variations in its dialects, such as English, it would be impossible to represent the language in all its variations with a single phonetic alphabet.

Some national languages like Finnish, Turkish, Serbo-Croatian (Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian), and Bulgarian have a very regular spelling system with a nearly one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes. Strictly speaking, these national languages lack a word corresponding to the verb «to spell» (meaning to split a word into its letters), the closest match being a verb meaning to split a word into its syllables. Similarly, the Italian verb corresponding to ‘spell (out)’, compitare, is unknown to many Italians because the act of spelling itself is rarely needed since Italian spelling is highly phonemic. In standard Spanish, it is possible to tell the pronunciation of a word from its spelling, but not vice versa; this is because certain phonemes can be represented in more than one way, but a given letter is consistently pronounced. French, with its silent letters and its heavy use of nasal vowels and elision, may seem to lack much correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, but its rules on pronunciation, though complex, are consistent and predictable with a fair degree of accuracy.

At the other extreme are languages such as English, where the spelling of many words simply has to be memorized as they do not correspond to sounds in a consistent way. For English, this is partly because the Great Vowel Shift occurred after the orthography was established, and because English has acquired a large number of loanwords at different times, retaining their original spelling at varying levels. Even English has general, albeit complex, rules that predict pronunciation from spelling, and these rules are successful most of the time; rules to predict spelling from the pronunciation have a higher failure rate.

Sometimes, countries have the written language undergo a spelling reform to realign the writing with the contemporary spoken language. These can range from simple spelling changes and word forms to switching the entire writing system itself, as when Turkey switched from the Arabic alphabet to a Turkish alphabet of Latin origin.

The sounds of speech of all languages of the world can be written by a rather small universal phonetic alphabet. A standard for this is the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Alphabetical order

Alphabets often come to be associated with a standard ordering of their letters, which can then be used for purposes of collation – namely for the listing of words and other items in what is called alphabetical order. Thus, the basic ordering of the Latin alphabet (ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ), for example, is well established, although languages using this alphabet have different conventions for their treatment of modified letters (such as the French é, à, and ô) and of certain combinations of letters (multigraphs). Some alphabets, such as Hanunoo, are learned one letter at a time, in no particular order, and are not used for collation where a definite order is required.

It is unknown if the earliest alphabets had a defined sequence. However, the order of the letters of the alphabet is attested from the fourteenth century B.C.E.[12] Tablets discovered in Ugarit, located on Syria’s northern coast, preserve the alphabet in two sequences. One, the ABGDE order later used in Phoenician, has continued with minor changes in Hebrew, Greek, Armenian, Gothic, Cyrillic, and Latin; the other, HMĦLQ, was used in southern Arabia and is preserved today in Ethiopic.[13] Both orders have therefore been stable for at least 3000 years.

The Brahmic family of alphabets used in India abandoned the inherited order for one based on phonology: The letters are arranged according to how and where they are produced in the mouth. This organization is used in Southeast Asia, Tibet, Korean hangul, and even Japanese kana, which is not an alphabet. The historical order was also abandoned in Runic and Arabic, although Arabic retains the traditional «abjadi order» for numbering.

Notes

- ↑ Geoffrey Sampson, Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction (Stanford University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0804712545).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Elizabeth J. Himelfarb, «First Alphabet Found in Egypt», Archaeology 53(1) (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ↑ Orly Goldwasser, «How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs» Biblical Archaeology Review 36(1) (Mar/Apr 2010). Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ Middle East: Oldest alphabet found in Egypt BBC News, November 15, 1999. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ↑ Ancient graffiti may display oldest alphabet The Japan Times, December 1, 1999. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ↑ Gordon J. Hamilton, «W. F. Albright and Early Alphabetic Writing,» Near Eastern Archaeology 65(1) (March 2002): 35-42.

- ↑ J. C. Darnell, F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, Marilyn J. Lundberg, P. Kyle McCarter, and Bruce Zuckermanet, «Two early alphabetic inscriptions from the Wadi el-Hol: New evidence for the origin of the alphabet from the western desert of Egypt.» The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 59 (2005).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Florian Coulmas, The Writing Systems of the World (Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1989, ISBN 0631180281).

- ↑ Jim A. Cornwell, «Ugaritic Writing» The Alpha and the Omega — Volume III, 1999. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 J.T. Hooker (ed.), Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet (Trustees of the British Museum, 1990, ISBN 978-0760707265).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Peter T. Daniels and William Bright (eds.), The World’s Writing Systems (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0195079937).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Andrew Robinson, The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms (New York, NY: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2007, ISBN 978-0500286609).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 A.R. Millard, «The Infancy of the Alphabet,» World Archaeology 17(3), Early Writing Systems (Feb., 1986): 390-398

- ↑ P. Kyle McCarter, «The Early Diffusion of the Alphabet,» The Biblical Archaeologist 37, No. 3 (Sep., 1974): 54-68.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 The Phoenician Alphabet Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ↑ «上親制諺文二十八字…是謂訓民正音(His majesty created 28 characters himself… It is Hunminjeongeum (original name for Hangul))», 《세종실록 (The Annals of the Choson Dynasty : Sejong)》 25년 12월.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coulmas, Florian. The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1989. ISBN 0631180281

- Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright (eds.). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0195079937

- Diringer, David, and H. Freeman. History of the Alphabet. Unwin Bros. Ltd, 1977. ISBN 978-0905418124

- Driver, G.R. Semitic Writing: From Pictograph to Alphabet. British Academy, 1976. ISBN 978-0197259177

- Fischer, Stephen Roger. A History of Writing. Reaktion Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1861891013

- Hoffman, Joel M. In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. New York, NY: NYU Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0814736548

- Hooker, J.T. (ed.). Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. Trustees of the British Museum, 1990. ISBN 978-0760707265

- Logan, Robert K. The Alphabet Effect: The Impact of the Phonetic Alphabet on the Development of Western Civilization. Hampton Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1572735231

- McLuhan, Marshall, and Robert K. Logan. «Alphabet, Mother of Invention,» Etcetera 34 (1977): 373-383.

- Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Josephine Bacon. Mysteries of the Alphabet: The Origins of Writing. Abbeville Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0789205216

- Robinson, Andrew. The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2007. ISBN 978-0500286609

- Sacks, David. Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z. Broadway Books, 2004. ISBN 978-0767911733

- Saggs, H.W.F. Civilization Before Greece and Rome. Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0300050318 (Chapter 4 traces the invention of writing).

- Ullman, B. L. «The Origin and Development of the Alphabet,» American Journal of Archaeology 31(3) (1927): 311-328.

External links

All links retrieved May 17, 2021.

- Alphabets Omniglot.

- The Alphabets of Europe by Michael Everson.

- The Greek alphabet H2G2.

- The Development of the Western Alphabet H2G2.

- The Greek alphabet Greek Language and Linguistics.

- The origins of abc: Where does our alphabet come from?

- How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs by Orly Goldwasser.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Alphabet history

- History_of_the_alphabet history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Alphabet»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Asked by: Cary Murphy

Score: 5/5

(5 votes)

The Phoenicians lived near what we now call the Middle East. They invented an alphabet with 22 consonants and no vowels (A, E, I, O or U). Vowels only became part of the alphabet much later.

When was the first letter invented?

The evolution of the alphabet involved two important achievements. The first was the step taken by a group of Semitic-speaking people, perhaps the Phoenicians, on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean between 1700 and 1500 bce. This was the invention of a consonantal writing system known as North Semitic.

Who created the first 22 letter alphabet?

About 700 years after, the Phoenicians developed an alphabet based on the earlier foundations. It was widely used in the Mediterranean, including southern Europe, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula and the Levant. The alphabet was made up of 22 letters, all of the consonants.

Who invented English letters?

Scholars attribute its origin to a little known Proto-Sinatic, Semitic form of writing developed in Egypt between 1800 and 1900 BC. Building on this ancient foundation, the first widely used alphabet was developed by the Phoenicians about seven hundred years later.

What is the 27th letter in the alphabet?

The ampersand often appeared as a character at the end of the Latin alphabet, as for example in Byrhtferð’s list of letters from 1011. Similarly, & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere.

30 related questions found

Is Phoenician a dead language?

Phoenician (/fəˈniːʃən/ fə-NEE-shən) is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. … The Phoenician alphabet was spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

What was first alphabet?

The first fully phonemic script, the Proto-Canaanite script, later known as the Phoenician alphabet, is considered by some to be the first alphabet, and is the ancestor of most modern alphabets, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and possibly Brahmic.

How did w get its name?

It is from this ⟨uu⟩ digraph that the modern name «double U» derives. The digraph was commonly used in the spelling of Old High German, but only in the earliest texts in Old English, where the /w/ sound soon came to be represented by borrowing the rune ⟨ᚹ⟩, adapted as the Latin letter wynn: ⟨ƿ⟩.

What called alphabet?

An alphabet is a writing system, a list of symbols for writing. The basic symbols in an alphabet are called letters. In an alphabet, each letter is a symbol for a sound or related sounds. … Many languages use the Latin alphabet: it is the most used alphabet today.

Who invented letters in math?

At the end of the 16th century, François Viète introduced the idea of representing known and unknown numbers by letters, nowadays called variables, and the idea of computing with them as if they were numbers—in order to obtain the result by a simple replacement.

Why do we pronounce W as double U?

Q: Why is the letter “w” called “double u”? It looks like a “double v” to me. A: The name of the 23rd letter of the English alphabet is “double u” because it was originally written that way in Anglo-Saxon times. As the Oxford English Dictionary explains it, the ancient Roman alphabet did not have a letter “w.”

Why do we call it double U?

So, Norman French used a double U to represent W sounds in words. … It was a character (ƿ) representing the sound (w) in Old English and early Middle English manuscripts, based on a rune with the same phonetic value.

Why is W pronounced V in German?

When the Germanic languages took the Latin alphabet they had to find a way to write the consonant [v] which didn’t exist in Latin at that point. So they took U and V and separated them. The Germanic languages started to write UU for the consonant [w], which later became our W.

Which language has the longest alphabet?

The language with the most letters is Khmer (Cambodian), with 74 (including some without any current use).

Why is J pronounced as Y?

Romanization can render «Я» as «ja», as many languages using the Roman alphabet use «j» for a sound much like the English «y». Wikipedia A better term would be anglicization. Your textbook may have used a romanization that was not applicable to English.

Is Phoenician older than Hebrew?

As such, Phoenician is attested slightly earlier than Hebrew, whose first inscriptions date to the 10th century B.C.E. Hebrew eventually achieved a long and extensive literary tradition (cf. the biblical books especially), while Phoe- nician is known only from inscriptions.

What language did the Jesus speak?

Hebrew was the language of scholars and the scriptures. But Jesus’s «everyday» spoken language would have been Aramaic. And it is Aramaic that most biblical scholars say he spoke in the Bible.

What is the oldest language in the world?

The Tamil language is recognized as the oldest language in the world and it is the oldest language of the Dravidian family. This language had a presence even around 5,000 years ago. According to a survey, 1863 newspapers are published in the Tamil language only every day.

Why does R look like P?

The letter R came from the Phoenician letter rosh (see image at left). The word rosh meant head and the letter resembles a neck and head. It also looks like a backwards P. When the letter entered the Greek alphabet, the Greeks turned the letter around and added the short leg to the side.

What does R mean in Latin?

R is a written abbreviation meaning king or queen. … R is short for the Latin words ‘rex’ and ‘regina’. …

What numbers stand for letters?

The numbers are assigned to letters of the Latin alphabet as follows:

- 1 = a, j, s,

- 2 = b, k, t,

- 3 = c, l, u,

- 4 = d, m, v,

- 5 = e, n, w,

- 6 = f, o, x,

- 7 = g, p, y,

- 8 = h, q, z,

Why isn’t an M called a double n?

The slave replied that he wanted the letter «m» to no longer be called double-n, as it had been until that time, because Nero’s daughter was called Neroette, and to him the letter «N» was the most beautiful in the whole language and could never be doubled. Nero granted this, and proclaimed it to be so forever.

«Writers spend years rearranging 26 letters of the alphabet,» novelist Richard Price once observed. «It’s enough to make you lose your mind day by day.» It’s also a good enough reason to gather a few facts about one of the most significant inventions in human history.

The Origin of the Word Alphabet

The English word alphabet comes to us, by way of Latin, from the names of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha and beta. These Greek words were in turn derived from the original Semitic names for the symbols: Aleph («ox») and beth («house»).

Where the English Alphabet Came From

The original set of 30 signs, known as the Semitic alphabet, was used in ancient Phoenicia beginning around 1600 BCE. Most scholars believe that this alphabet, which consisted of signs for consonants only, is the ultimate ancestor of virtually all later alphabets. (The one significant exception appears to be Korea’s han-gul script, created in the 15th century.)

Around 1,000 BCE, the Greeks adopted a shorter version of the Semitic alphabet, reassigning certain symbols to represent vowel sounds, and eventually, the Romans developed their own version of the Greek (or Ionic) alphabet. It’s generally accepted that the Roman alphabet reached England by way of the Irish sometime during the early period of Old English (5 c.- 12 c.).

Over the past millennium, the English alphabet has lost a few special letters and drawn fresh distinctions between others. But otherwise, our modern English alphabet remains quite similar to the version of the Roman alphabet that we inherited from the Irish.

The Number of Languages That Use the Roman Alphabet

About 100 languages rely on the Roman alphabet. Used by roughly two billion people, it’s the world’s most popular script. As David Sacks notes in Letter Perfect (2004), «There are variations of the Roman alphabet: For example, English employs 26 letters; Finnish, 21; Croatian, 30. But at the core are the 23 letters of ancient Rome. (The Romans lacked J, V, and W.)»

How Many Sounds There Are in English

There are more than 40 distinct sounds (or phonemes) in English. Because we have just 26 letters to represent those sounds, most letters stand for more than one sound. The consonant c, for example, is pronounced differently in the three words cook, city, and (combined with h) chop.

What Are Majuscules and Minuscules?