Asked by: Cayla Wisoky

Score: 5/5

(37 votes)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. A sentence word (also called a one-word sentence) is a single word that forms a full sentence. Henry Sweet described sentence words as ‘an area under one’s control’ and gave words such as «Come!», «John!», «Alas!», «Yes.» and «No.» as examples of sentence words.

What is a one word line called?

Why? A lonely single word at the end of a paragraph creates a visual interruption in the flow that breaks the reader’s focus. This is called a “runt”.

Can a sentence contain 1 word?

A sentence must have a subject (noun) and a verb (action). However, when we speak we don’t always use complete sentences. So there are sentences that are made up of just one word followed by a punctuation mark. This is allowable because in one-word sentences either the noun or the verb is implied.

What is a short sentence called?

A simple sentence is built from the minimum of a subject and a main verb. It can be very short in length but doesn’t have to be. There are several reasons for using simple sentences.

What is a one word phrase?

In syntax and grammar, a phrase is a group of words which act together as a grammatical unit. … Phrases can consist of a single word or a complete sentence. In theoretical linguistics, phrases are often analyzed as units of syntactic structure such as a constituent.

41 related questions found

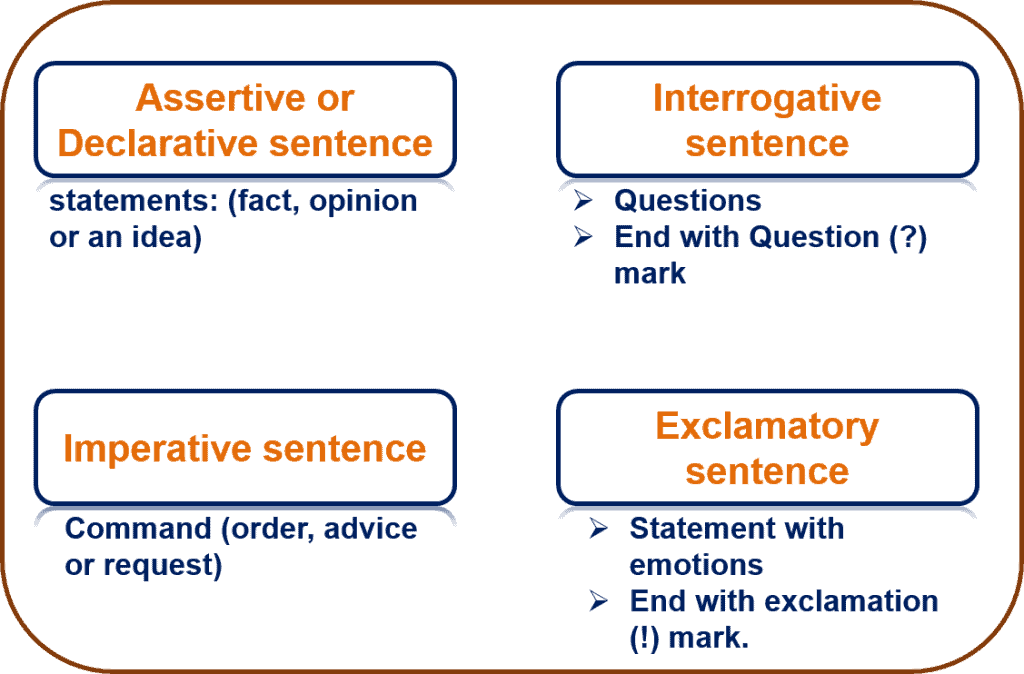

What are types of sentences?

The Four Types of Sentences

Declarative Sentences: Used to make statements or relay information. Imperative Sentences: Used to make a command or a direct instruction. Interrogative Sentences: Used to ask a question. Exclamatory Sentences: Used to express a strong emotion.

What are the 7 types of sentences?

The other way is based on a sentence’s structure (simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex).

- Statements/Declarative Sentences. These are the most common type of sentence. …

- Questions/Interrogative Sentences. …

- Exclamations/Exclamatory Sentences. …

- Commands/Imperative Sentences.

What is a two word sentence called?

Examples of two-word sentences that everyone would agree are «complete sentences» are «Dogs bark» (Subject Verb), «I slept» (Subject Verb), and «We left» (Subject Verb). If «sentence» means «utterance» or «turn at speaking,» the answer is also «yes».

What is the difference between Zeugma and Syllepsis?

is that syllepsis is (rhetoric) a figure of speech in which one word simultaneously modifies two or more other words such that the modification must be understood differently with respect to each modified word; often causing humorous incongruity while zeugma is (rhetoric) the act of using a word, particularly an …

Where is Ke in a sentence?

«I visited my old neighborhood where I have the best memories.» «I went back to the store where I bought my sweater.» «I went to the library where I studied until 8 o’clock.» «I went to my friend’s house where we got ready for the party.»

Is unfortunate a single word?

unfavorable or inauspicious: an unfortunate beginning. regrettable or deplorable: an unfortunate remark.

What is an example of enjambment?

Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. For example, the poet John Donne uses enjambment in his poem «The Good-Morrow» when he continues the opening sentence across the line break between the first and second lines: «I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I / Did, till we loved?

Is enjambment a technique?

Having a line break at the end of a phrase or complete thought is a regular and expected pattern in poetry. Poets subvert this expectation by using a technique called enjambment. Enjambment breaks with our expectations of where a line should end, creating a different feel to a poem.

Is enjambment a syntax?

In poetry, enjambment (/ɛnˈdʒæmbmənt/ or /ɪnˈdʒæmmənt/; from the French enjamber) is incomplete syntax at the end of a line; the meaning ‘runs over’ or ‘steps over’ from one poetic line to the next, without punctuation. Lines without enjambment are end-stopped.

Can there be a 2 word sentence?

Two-word sentences have all they need to qualify as complete sentences: a subject and a verb. Used appropriately, they can be powerful. When teaching students about complete sentences, the two-word sentence is a good starting point. «Chrysanthemum could scarcely believe her ears.

What is the longest sentence using only one word?

“Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.” According to William Rappaport, a linguistics professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo (naturally), that — the word “Buffalo,” eight times in a row — is a legitimate, grammatically valid sentence.

Is yes a full sentence?

The single word yes could be considered a sentence because there is an understood subject and verb associated with it, one that could be drawn from…

What are the 12 types of sentences?

Types of Sentences

- 1 (1) Declarative Sentences.

- 2 (2) Imperative Sentences.

- 3 (3) Interrogative Sentences.

- 4 (4) Exclamatory Sentences.

What are the 8 kinds of sentences?

Terms in this set (8)

- Simple Sentence. a sentence with only one independent clause.

- Compound Sentence. a sentence made up of two or more simple sentences.

- Complex Sentence. …

- Compound-Complex Sentence. …

- Declarative Sentence. …

- Interrogative Sentence. …

- Imperative Sentence. …

- Exclamatory Sentence.

What are the 3 main types of sentences?

Three essential types of sentence are declarative sentences (which are statements), interrogative sentences (which are questions), and imperative sentences (which are orders).

Is When Pigs Fly an idiom?

«When pigs fly» is an adynaton, a way of saying that something will never happen. The phrase is often used for humorous effect, to scoff at over-ambition.

Is break a leg an idiom?

«Break a leg» is a typical English idiom used in the context of theatre or other performing arts to wish a performer «good luck». … When said at the onset of an audition, «break a leg» is used to wish success to the person being auditioned.

What is the idiom of spill the beans?

Disclose a secret or reveal something prematurely, as in You can count on little Carol to spill the beans about the surprise. In this colloquial expression, first recorded in 1919, spill means “divulge,” a usage dating from the 1500s.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A sentence word (also called a one-word sentence) is a single word that forms a full sentence.

Henry Sweet described sentence words as ‘an area under one’s control’ and gave words such as «Come!», «John!», «Alas!», «Yes.» and «No.» as examples of sentence words.[1] The Dutch linguist J. M. Hoogvliet described sentence words as «volzinwoorden».[2] They were also noted in 1891 by Georg von der Gabelentz, whose observations were extensively elaborated by Hoogvliet in 1903; he does not list «Yes.» and «No.» as sentence words. Wegener called sentence words «Wortsätze».[3]

Single-word utterances and child language acquisition[edit]

One of the predominant questions concerning children and language acquisition deals with the relation between the perception and the production of a child’s word usage. It is difficult to understand what a child understands about the words that they are using and what the desired outcome or goal of the utterance should be.[4]

Holophrases are defined as a «single-word utterance which is used by a child to express more than one meaning usually attributed to that single word by adults.»[5] The holophrastic hypothesis argues that children use single words to refer to different meanings in the same way an adult would represent those meanings by using an entire sentence or phrase. There are two opposing hypotheses as to whether holophrases are structural or functional in children. The two hypotheses are outlined below.

Structural holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

The structural version argues that children’s “single word utterances are implicit expressions of syntactic and semantic structural relations.” There are three arguments used to account for the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The comprehension argument, the temporal proximity argument, and the progressive acquisition argument.[5]

- The comprehension argument is based on the idea that comprehension in children is more advanced than production throughout language acquisition. Structuralists believe that children have knowledge of sentence structure but they are unable to express it due to a limited lexicon. For example, saying “Ball!” could mean “Throw me the ball” which would have the structural relation of the subject of the verb. However, studies attempting to show the extent to which children understand syntactic structural relation, particularly during the one-word stage, end up showing that children “are capable of extracting the lexical information from a multi-word command,” and that they “can respond correctly to a multi-word command if that command is unambiguous at the lexical level.”[5] This argument therefore does not provide evidence needed to prove the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis because it fails to prove that children in the single-word stage understand structural relations such as the subject of a sentence and the object of a verb.[5]

- The temporal proximity argument is based on the observation that children produce utterances referring to the same thing, close to each other. Even the utterances aren’t connected, it is argued that children know about the linguistic relationships between the words, but cannot connect them yet.[5] An example is laid out below:

→ Child: «Daddy» (holding pair of fathers pants)

- → Child

-

-

- «Bai» (‘bai’ is the term the child uses for any item of clothing)

-

The usage of ‘Daddy’ and ‘Bai’ used in close proximity are seen to represent a child’s knowledge of linguistic relations; in this case the relation is the ‘possessive’.[6] This argument is seen as having insufficient evidence as it is possible that the child is only switching from one way to conceptualize pants to another. It is also pointed out that if the child had knowledge of linguistic relationships between words, then the child would combine the words together, instead of using them separately.[5]

- Finally, the last argument in support of structuralism is the progressive acquisition argument. This argument states that children progressively gain new structural relations throughout the holophrastic stage. This is also unsupported by the research.[5]

Functional holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

Functionalists doubt whether children really have structural knowledge, and argue that children rely on gestures to carry meaning (such as declarative, interrogative, exclamative or vocative). There are three arguments used to account for the functional version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The intonation argument, the gesture argument, and the predication argument.[5]

- The intonation argument suggests that children use intonation in a contrastive way. Researchers have established through longitudinal studies that children have knowledge of intonation and can use it to communicate a specific function across utterances.[7][8][9] Compare the two examples below:

→ Child: «Ball.» (flat intonation) — Can mean «That is a ball.»

-

-

- → Child: «Ball?» (rising inflection) — Can mean «Where is the ball?»

-

- However, it has been noted by Lois Bloom that there is no evidence that a child intends for intonation to be contrastive, it is only that adults are able to interpret it as such.[10] Martyn Barrett contrasts this with a longitudinal study performed by him, where he illustrated the acquisition of a rising inflection by a girl who was a year and a half old. Although she started out using intonation randomly, upon acquisition of the term «What’s that» she began to use rising intonation exclusively for questions, suggesting knowledge of its contrastive usage.[11]

- The gesture argument establishes that some children use gesture instead of intonation contrastively. Compare the two examples laid out below:

→ Child: «Milk.» (points at milk jug) — could mean “That is milk.”

-

-

- → Child: «Milk.» (open-handed gesture while reaching for a glass of milk) — could mean “I want milk.”

-

- Each use of the word ‘milk’ in the examples above could have no use of intonation, or a random use of intonation, and so meaning is reliant on gesture. Anne Carter observed, however, that in the early stages of word acquisition children use gestures primarily to communicate, with words merely serving to intensify the message.[12] As children move onto multi-word speech, content and context are also used alongside gesture.

- The predication argument suggests that there are three distinct functions of single word utterances, ‘Conative’, which is used to direct the behaviour of oneself or others; ‘Expressive’, which is used to express emotion; and referential, which is used to refer to things.[13] The idea is that holophrases are predications, which is defined as the relationship between a subject and a predicate. Although McNeill originally intended this argument to support the structural hypothesis, Barrett believes that it more accurately supports the functional hypothesis, as McNeill fails to provide evidence that predication is expressed in holophrases.[5]

Single-word utterances and adult usage[edit]

While children use sentence words as a default strategy due to lack of syntax and lexicon, adults tend to use sentence words in a more specialized way, generally in a specific context or to convey a certain meaning. Because of this distinction, single word utterances in children are called ‘holophrases’, while in adults, they are called ‘sentence words’. In both the child and adult use of sentence words, context is very important and relative to the word chosen, and the intended meaning.

Sentence word formation[edit]

Many sentence words have formed from the process of devaluation and semantic erosion. Various phrases in various languages have devolved into the words for «yes» and «no» (which can be found discussed in detail in yes and no), and these include expletive sentence words such as «Well!» and the French word «Ben!» (a parallel to «Bien!»).[14]

However, not all word sentences suffer from this loss of lexical meaning. A subset of sentence words, which Fonagy calls «nominal phrases», exist that retain their lexical meaning. These exist in Uralic languages, and are the remainders of an archaic syntax wherein there were no explicit markers for nouns and verbs. An example of this is the Hungarian language «Fecske!», which transliterates as «Swallow!», but which has to be idiomatically translated with multiple words «Look! A swallow!» for rendering the proper meaning of the original, which to a native Hungarian speaker is neither elliptical nor emphatic. Such nominal phrase word sentences occur in English as well, particularly in telegraphese or as the rote questions that are posed to fill in form data (e.g. «Name?», «Age?»).[14]

Sentence word syntax[edit]

A sentence word involves invisible covert syntax and visible overt syntax. The invisible section or «covert» is the syntax that is removed in order to form a one word sentence. The visible section or «overt» is the syntax that still remains in a sentence word.[15] Within sentence word syntax there are 4 different clause-types: Declarative (making a declaration), exclamative (making an exclamation), vocative (relating to a noun), and imperative (a command).

| Overt | Covert | |

|---|---|---|

| Declarative | ‘That is excellent!’

|

‘Excellent!’

|

| Exclamative | ‘That was rude!’

|

‘Rude!’

|

| Vocative | ‘There is Mary!’

|

‘Mary!’

|

| Imperative | ‘You should leave!’

|

‘Leave!’

|

| Locative | ‘The chair is here.’

|

‘Here.’

|

| Interrogative | ‘Where is it?’

|

‘Where?’

|

The words in bold above demonstrate that in the overt syntax structures, there are words that can be omitted in order to form a covert sentence word.

Distribution cross-linguistically[edit]

Other languages use sentence words as well.

- In Japanese, a holophrastic or single-word sentence is meant to carry the least amount of information as syntactically possible, while intonation becomes the primary carrier of meaning.[16] For example, a person saying the Japanese word e.g. «はい» (/haɪ/) = ‘yes’ on a high level pitch would command attention. Pronouncing the same word using a mid tone, could represent an answer to a roll-call. Finally, pronouncing this word with a low pitch could signify acquiescence: acceptance of something reluctantly.[16]

| High tone pitch | Mid tone pitch | Low tone pitch |

|---|---|---|

| Command attention | Represent an answer to roll-call | Signify acquiescence acceptance of something reluctantly |

- Modern Hebrew also exhibits examples of sentence words in its language, e.g. «.חַם» (/χam/) = «It is hot.» or «.קַר» (/kar/) = «It is cold.».

References[edit]

- ^ Henry Sweet (1900). «Adverbs». A New English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 127. ISBN 978-1-4021-5375-4.

- ^ Jan Noordegraaf (2001). «J. M. Hoogvliet as a teacher and theoretician». In Marcel Bax; C. Jan-Wouter Zwart; A. J. van Essen (eds.). Reflections on Language and Language Learning. John Benjamins B.V. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-272-2584-9.

- ^ Giorgio Graffi (2001). 200 Years of Syntax. John Benjamins B.V. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-58811-052-7.

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2009). Language Development. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barrett, Martyn, D. (1982). «The holophrastic hypothesis: Conceptual and empirical issues». Cognition. 11: 47–76. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(82)90004-x.

- ^ Rodgon, M.M. (1976). Single word usage, cognitive development and the beginnings of combinatorial speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dore, J. (1975). «Holophrases, speech acts and language universals». Journal of Child Language. 2: 21–40. doi:10.1017/s0305000900000878.

- ^ Leopold, W.F. (1939). Speech Development of a Bilingual Child: A Linguist’s Record. Volume 1: Vocabulary growth in the first two years. Evanston, ill: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ Von Raffler Engel, W. (1973). «The development from sound to phoneme in child language». Studies of Child Language Development.

- ^ Bloom, Lois (1973). One word at a time: The use of single word utterances before syntax. The Hague: Mouton.

- ^ Barrett, M.D (1979). Semantic Development during the Single-Word Stage of Language Acquisition (Unpublished doctoral thesis).

- ^ Carter, Anne :L. (1979). «Prespeech meaning relations an outline of one infant’s sensorimotor morpheme development». Language Acquisition: 71–92.

- ^ David, McNeill (1970). The Acquisition of Language: The Study of Developmental Psycholinguistics.

- ^ a b Ivan Fonagy (2001). Languages Within Language. John Benjamins B.V. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-927232-82-1.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: a generative introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 496.

- ^ a b Hirst, D. (1998). Intonation systems: a survey of twenty languages. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 372.

What is syntax?

-

Syntax is the study of the structure of sentences.

-

Syntax analyzes how words combine to form sentences.

-

Sentences are made up of smaller units, called phrases (which in turn are made up of words).

Why is syntax important?

-

We speak in sentences not in words. To understand the structure of a language it is necessary to study the structure of sentences.

-

If we learn to analyze the structure of sentences, we will also learn to analyze their meaning.

-

The study of syntax is the study of the function of words, which is necessary to understand the structure and the meaning of a language.

The basic functions

-

Subject: obligatory element; it specifies the entity about which we will say something (the doer of the action, the entity described, etc.)

-

Object: obligatory element, it completes the meaning of a word or sentence.

-

Subject or Object Complement: obligatory element that adds a description of the subject or the object. These function also receive the names of Attribute and Predicative.

-

Modifier: optional element; adds additional information that specifies a noun

-

Adverbial: optional element; modifies a verb, adjective or adverb

What is a sentence?

Although everyone knows or thinks they know what a word is and what a sentence is, both terms defy exact definition. The sentence as a linguistic concept has been defined in over 200 different ways, none of them completely adequate. Here are the most important attempts at defining the sentence:

The traditional, or common sense definition states that a sentence is a group of words that expresses a thought . The problem comes in defining what a thought is. The phrase an egg expresses a thought but is it a sentence? A sentence like I closed the door because it was cold expresses two thoughts and yet it is one sentence.

-

A sentence is basically a string of words that follow the grammatical rules of a language.

-

A sentence expresses a complete thought

-

A sentence is made up of phrases. At the very least a sentence contains a verb phrase (also known as the predicate) and a subject.

-

We will use the terms SENTENCE and CLAUSE indistinctively.

What is a phrase?

-

A phrase is a part of a sentence. It does not express a complete thought.

-

A phrase is a group of words that function as a single unit. Usually they can be substituted by a pronominal form.

-

All phrases have one word which is the nucleus, the head. The head of a phrase determines the kind of phrase we have: Noun Phrase, Adjective Phrase, Adverb Phrase, Prepositional Phrase or Verb Phrase.

A phrase is a small group of words that forms a meaningful unit within a clause.

A clause is a group of words that contains a verb (and usually other components too). A clause may form part of a sentence or it may be a complete sentence in itself.

A sentence is a group of words that makes complete sense, contains a main verb, and begins with a capital letter.

Sentence must:

-

have a subject and a verb (predicate)

-

MUST have a complete though

-

Begins with a capital letter

-

Ends with punctuation

-

have intonation

Sentences are used:

-

to make statements:

-

to ask questions or make requests:

-

to give orders:

-

to express exclamations:

Syntactic atoms

-

The basic unit of syntax is not the word, but the syntactic atom, defined as a structure that fulfills a basic syntactic function. Syntactic atoms may be either a single word or a phrase that fulfills a single syntactic function.

-

Fido ate the bone.

-

The dog ate the bone.

-

The big yellow dog ate the bone.

-

Our dog that we raised from a puppy ate the bone.

Simple sentence

A simple sentence normally contains one statement (known as a main clause). For example:

The train should be here soon.

His father worked as a journalist.

Compound sentence

A compound sentence contains two or more clauses of equal status (or main clauses), which are normally joined by a conjunction such as and or but. For example:

|

Joe became bored with teaching |

and |

he looked for a new career. |

|

[main clause] |

[conjunction] |

[main clause] |

|

Boxers can be very friendly dogs |

but |

they need to be trained. |

|

[main clause] |

[conjunction] |

[main clause] |

Complex sentence

A complex sentence is also made up of clauses, but in this case the clauses are not equally balanced. They contain a main clause and one or more subordinate clauses. For example:

|

The story would make headlines |

if it ever became public. |

|

[main clause] |

[subordinate clause] |

|

He took up the project again |

as soon as he felt well enough. |

|

[main clause] |

[subordinate clause] |

A clause is a group of words that contains a verb (and usually other components too). A clause may form part of a sentence or it may be a complete sentence in itself. For example:

|

He was eating a bacon sandwich. |

|

[clause] |

|

She had a long career |

but she is remembered mainly for one early work. |

|

[clause] |

[clause] |

Main clause

Every sentence contains at least one main clause. A main clause may form part of a compound sentence or a complex sentence, but it also makes sense on its own, as in this example:

|

He was eating a bacon sandwich. |

|

[main clause] |

Compound sentences are made up of two or more main clauses linked by a conjunction such asand, but, or so, as in the following examples:

|

I love sport |

and |

I’m captain of the local football team. |

|

[main clause] |

[conjunction] |

[main clause] |

|

She was born in Spain |

but |

her mother is Polish. |

|

[main clause] |

[conjunction] |

[main clause] |

Subordinate clause

A subordinate clause depends on a main clause for its meaning. Together with a main clause, a subordinate clause forms part of a complex sentence. Here are two examples of sentences containing subordinate clauses:

|

After we had had lunch, |

we went back to work. |

|

[subordinate clause] |

[main clause] |

|

I first saw her in Paris, |

where I lived in the early nineties. |

|

[main clause] |

[subordinate clause] |

A phrase is a small group of words that forms a meaningful unit within a clause.

Types of Syntactic Relations

One of the most important problems of syntax is the classification and criteria of

distinguishing of different types of syntactical connection.

L. Barkhudarov (3) distinguishes three basic types of syntactical bond:

-

subordination,

-

co-ordination,

-

predication.

Subordination implies the relation of head-word and adjunct-word, as e.g. a tall boy, a red pen and so on.

The criteria for identification of head-word and adjunct is the substitution test. Example:

1) A tall boy came in.

2) A boy came in.

3) Tall came in.

This shows that the head-word is «a boy» while «tall» is adjunct, since the sentence (3) is

unmarked from the English language view point. While sentence (2) is marked as it has an invariant meaning with the sentence (1).

Co-ordination is shown either by word-order only, or by the use of form-words:

4) Pens and pencils were purchased.

5) Pens were purchased.

6) Pencils were purchased.

Since both (5), (6) sentences show identical meaning we may say that these two words are

independent: coordination is proved.

Predication is the connection between the subject and the predicate of a sentence. In predication none of the components can be omitted which is the characteristic feature of this type of connection, as e.g.

7) He came …

9) * … came or

10) I knew he had come

11) * I knew he

12) * I knew had come

Sentences (8), (9) and (11), (12) are unmarked ones.

H. Sweet (42) distinguishes two types of relations between words: subordination, coordination.

Subordination is divided in its turn into concord when head and adjunct words have alike inflection, as it is in phrases this pen or these pens: and government when a word assumes a certain grammatical form through being associated with another word:

13) I see him, here «him» is in the objective case-form.

The transitive verbs require the personal pronouns in this case.

14) I thought of him. “him” in this sentence is governed by the preposition “of”. Thus, “see” and “of” are the words that governs while “him” is a governed word.

B. Ilyish (15) also distinguishes two types of relations between words: agreement by which he means «a method of expressing a syntactical relationship, which consists in making the subordinate word take a form similar to that of the word to which it is subordinated». Further he states: «the sphere of agreement in Modern English is

extremely small. It is restricted to two pronouns-this and that …» government («we understand the use of a certain form of the subordinate word required by its head word, but not coinciding with the form of the head word itself-that is the difference between agreement and government»)

e.g. Whom do you see

This approach is very close to Sweet’s conception.

As one can see that when speaking about syntactic relations between words we mention the terms coordination, subordination, predication, agreement and government

It seems that it is very important to differentiate the first three terms (coordination, subordination and predication) from the terms agreement and government, because the first three terms define the types of syntactical relations from the standpoint of dependence of the components while the second ones define the syntactic relations from the point of view of the correspondence of the grammatical forms of their components. Agreement and government deals with only subordination and has nothing to do with coordination and predication. Besides agreement and government there is one more type of syntactical relations which may be called collocation when head and adjunct words are connected with each-other not by formal grammatical means (as it is the case with agreement and government but by means of mere collocation, by the order of words and by their meaning as for example: fast food, great day, sat silently and so on).

subordination – подчинение

coordination –согласованность

predication – предикация

agreement- согласование

Согласование (agreement) имеет место тогда, когда подчиненное слово принимают форму, сходную с формой ядерного слова, например: this boy, these boys; the child plays, the children play; в английском языке слова согласуются только по категории числа в некоторых контекстах.

Управление (government) имеет место тогда, когда некая форма адъюнкта требуется при присоединении к ядерному слову, но не совпадает с ним по форме, например: to see him; to talk to him. Rely on him, to be proud of her.

Примыкание(adjoinment)- не предполагает никакого формального признака связи, слова объединяются просто на основе контакта друг с другом, например: to go home, to nod silently, to act cautuiosly.

Замыкание(enclosure) имеет место тогда, когда адъюнкт располагается между двумя частями аналитической формы ядерного слова, например: to thoroughly think over, the then government, an interesting question , a pretty face, your pretty man, on good essay.

Theme and Rheme

Theme-functions as the ‘starting point for the message’ (M. A. K. Halliday, 1985a, p. 39),the element which the clause is going to be ‘about’ has a crucial effect in orienting listeners and readers. Theme is the starting point of the clause, realised by whatever element comes first.

Rheme

is the rest of the message, which provides the additional information added to the starting point and which is available for subsequent development in the text. The different choice of Theme has contributed to a different meaning and English uses firstclausal position as a signal to orient a different meaning of the sentences. For example,

Li Ping read a very good book last night.

Li Ping— theme

read a very good book last night.- rheme

A very good book,Li ping read last night.

A very good book— theme

Li ping read last night.- rheme

Last night Li ping read a very good book.

What Li Ping read

Last night was a very good book.

Li Ping,he read a very good book last night.

In each case above, the writer starts the message from a different point, that is, to choose a different Theme for the clause. As Halliday (1994, p.38) mentioned Theme as the‘starting-point for the message’ or ‘the ground from which the clause is taking off’.

And also, the different choice of Theme has contributed to a different meaning. What makes these sentences different is that they differ in their choice of theme and they tell us what

Li Ping, Avery good book, Last night or What Li Ping read

is going to be about.

The

sentence, as has been mentioned, is the central object of study in

syntax. It can be defined as the immediate integral unit of speech

built up by words according to a definite syntactic pattern and

distinguished by a contextually

The

correlation of the word and the sentence shows some important

differences and similarities between these two main level-forming

lingual units. Both of them are nominative units, but the word just

names objects and phenomena of reality; it is a purely nominative

component of the word-stock, while the sentence is at the same time a

nominative and predicative lingual unit: it names dynamic situations,

or situational events, and at the same time reflects the connection

between the nominal denotation of the event, on the one hand, and

objective reality, on the other hand, showing the time of the event,

its being real or unreal, desirable or undesirable, etc. A sentence

can consist of only one word, as any lingual unit of the upper level

can consist of only one unit of the lower level, e.g.: Why? Thanks.

But a word making up a sentence is thereby turned into an

utterance-unit expressing various connections between the situation

described and actual reality. So, the definition of the sentence as a

predicative lingual unit gives prominence to the basic differential

feature of the sentence as a separate lingual unit: it performs the

nominative signemic function, like the word or the phrase, and at the

same time it performs the reality-evaluating, or predicative

function.

Another

difference between the word and the sentence is as follows: the word

exists in the system of language as a ready-made unit, which is

reproduced in speech; the sentence is produced each time in speech,

except for a limited number of idiomatic utterances. The sentence

belongs primarily to the sphere of speech; earlier logical and

psychological oriented grammar treated the sentence as a portion of

the flow of words of one speaker containing a complete thought.

Being

a unit of speech, the sentence is distinguished by a relevant

intonation: each sentence possesses certain intonation contours,

including pauses, pitch movements and stresses, which separate one

sentence from another in the flow of speech and, together with

various segmental means of expression, participate in rendering

essential communicative-predicative meanings (for example,

interrogation).

But,

as was outlined at the beginning of the course, speech presents only

one aspect of language in the broad sense of the term, which

dialectically combines the system of language, language proper

(“langue”), and the immediate realization of it in the process of

intercourse, speech proper (“parole”). The sentence as a unit of

communication also includes two sides inseparably connected with each

other: fixed in the system of the language are typical models,

generalized sentence patterns, which speakers follow when

constructing their own utterances in actual speech. The number of

actual sentences, or utterances, is infinite; the number of

“linguistic sentences” or sentence patterns in the system of

language is definite, and they are the object of study in grammar.

The

definition of the category of predication is similar to the

definition of the category of modality, which also shows a connection

between the named objects and actual reality. However, modality is a

broader category, revealed not only in grammar, but in the lexical

elements of language; for example, various modal meanings are

expressed by modal verbs (can, may, must, etc.), by word-particles of

specifying modal semantics (just, even, would-be, etc.), by

semi-functional modal words and phrases of subjective evaluation

(perhaps, unfortunately, by all means, etc.) and by other lexical

units. Predication can be defined as syntactic modality, expressed by

the sentence.

The

center of predication in the sentence is the finite form of the verb,

the predicate: it is through the finite verb’s categorial forms of

tense, mood, and voice that the main predicative meanings, actual

evaluations of the event, are expressed. L. Tesnière, who introduced

the term “valency” in linguistics, described the verbal predicate

as the core around which the whole sentence structure is organized

according to the valencies of the predicate verb; he subdivided all

verbal complements and supplements into so-called “actants”,

elements that identify the participants in the process, and

“circonstants”, or elements that identify the circumstances of

the process[1]. Besides the predicate, other elements of the sentence

also help express predication: for example, word order, various

functional words and, in oral speech, intonation. In addition to

verbal time and mood evaluation, the predicative meanings of the

sentence include the purpose of communication (declaration –

interrogation – inducement), affirmation and negation and other

meanings

As

the description above shows, predication is the basic differential

feature of the sentence, but not the only one. There is a profound

difference between the nominative function of the word and the

nominative function of the sentence. The nominative content of a

syntagmatically complete average sentence, called a proposition,

reflects a processual situation, an event that includes a certain

process (actional or statal) as its dynamic center, the agent of the

process, the objects of the process, and various conditions and

circumstances of the realization of the process. The situation,

together with its various elements, is reflected through the

nominative parts (members) of the sentence, distinguished in the

traditional grammatical or syntactic division of the sentence, which

can also be defined as its nominative division. No separate word, no

matter how many stems it consists of, can express the

situation-nominative semantics of a proposition.

To

some extent, the nomination of situational events can be realized by

expanded substantive or nominal phrases. Between the sentence and the

substantive phrase of situational semantics direct transformations

are possible; the transformation of a sentence into a nominal phrase

is known as “nominalization”, e.g.: His father arrived

unexpectedly à his father’s unexpected arrival, the unexpected

arriving of his father, etc. When a sentence is transformed into a

substantive phrase, or “nominalized”, it loses its

processual-predicative character. This, first, supports once again

the idea that the content of the sentence is a unity of two mutually

complementary aspects: of the nominative aspect and the predicative

aspect; and, second, this specifies the definition of predication:

predication should be interpreted not simply as referring the content

of the sentence to reality, but as referring the nominative content

of the sentence to reality.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

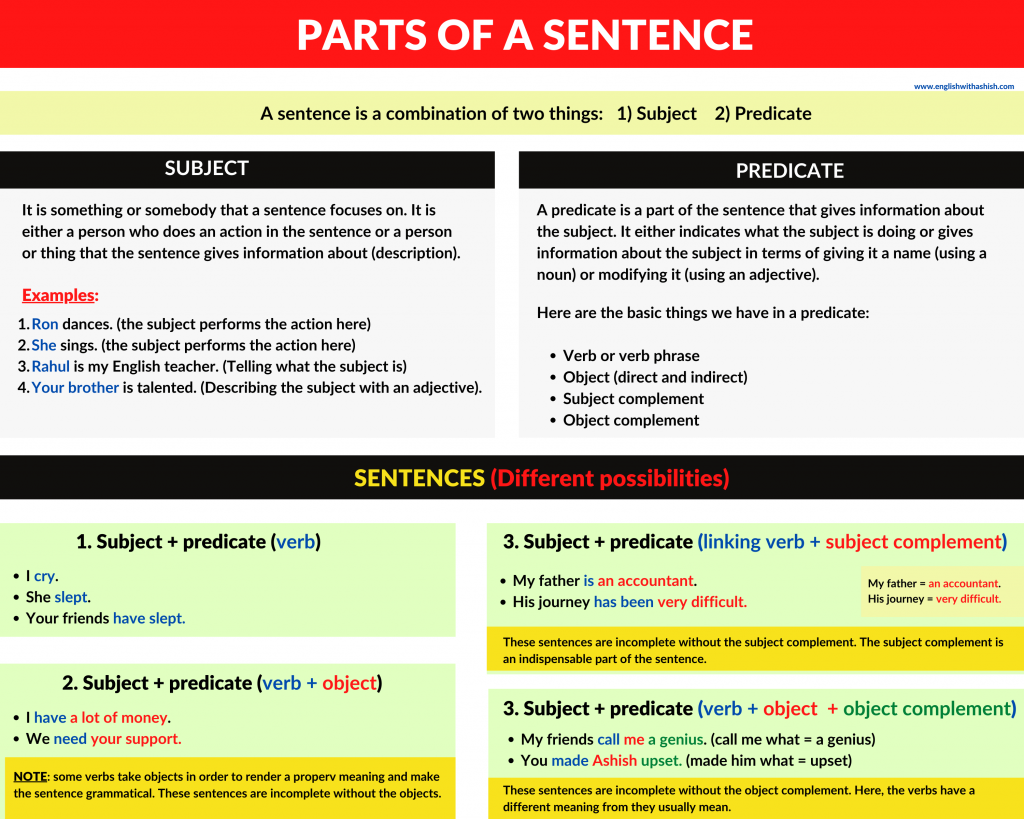

Every sentence in English is a combination of some elements that have their separate roles to play in the sentence. In this post, we will learn the basic elements that we need in order to form a sentence.

Let’s first understand what a sentence in English is.

What is a sentence in English?

A sentence is a group of words that have a particular meaning. It contains two main elements:

- Subject

- Predicate

To be called a sentence, it (a group of words) must make sense.

Examples:

- I sleep.

- We eat.

- I have money.

- We are working.

- You me.

- She living is.

- I you love.

All these examples have a group of words. Notice the last three examples don’t make any sense; they don’t render a meaning. So, having a group of words doesn’t qualify into a sentence. It has to have the necessary elements, that too in the right order.

Let’s correct them and change them into sentences.

- You trouble me. (Added a necessary element)

- She is living. (Corrected the order)

- I love you. (Corrected the order)

A sentence has two major elements:

- Subject

- Predicate

1. SUBJECT

A subject is something or someone the sentence is about. It is what the sentence focuses on. It is either a person who performs the action or a person or a thing that the sentence gives information about (descriptive information).

Examples:

- Rahul sings.

- Jon lives in Canada.

- Tom is working.

- I teach English.

In all the above examples, the subject (italicized) is the part (person) performing the action in the sentence. A sentence doesn’t always indicate an action that the subject performs. It also gives information about the subject.

Examples:

- Rahul is my English teacher. (Telling what the subject is)

- Jon is talented. (Describing the subject with an adjective).

- Tom is under pressure. (describing the subject with adjectival phrase)

- I am your boss. (telling what the subject is)

Types of subjects in English

There are three types of subjects in English:

- Simple subject

- Compound subject

- Complete subject

Simple subject

A simple subject is a one-word subject. It does not include any modifiers.

- India is the biggest democratic country in the world.

- Jacob loves pancakes.

- The man in the white coat is a doctor.

- Rahul called me after the meeting.

NOTE: a simple subject does not have to be a single word. It can be a group of words, but it won’t have any modifiers.

- The Taj Mahal is one of the seven wonders of the world.

- Justin Bieber is my sister’s favourite singer.

Here, the subject is a proper noun. It does not have any modifiers.

Complete subject

A complete subject is a combination of a simple subject and the words that modify it.

Examples:

1. Some people just make excuses for their failures.

Simple subject = people

Modifier = some

Complete subject = some people

2. People living in this area are very poor.

Simple subject = people

Modifier = living in this area (present participle phrase)

Complete subject = people living in this area

3. A wise man once said that money is an illusion.

Simple subject = man

Modifiers = a, wise

Complete subject = a wise man

A complete subject is formed using a simple subject and one or more modifiers. Here are the ways to form a complete subject:

- Pre-modifier/s + simple subject

- Simple subject + modifier/s

- Pre-modifier/s + simple subject + post-modifier/s

Pre-modifier + simple subject

- My friends love me. (Premodifier = my)

- A school is being built here. (Premodifier = a)

Simple subject + post-modifier

- People in my village support each other. (post-modifier = in my village)

- Events of such nature kept happening. (post-modifier = of such nature)

Pre-modifier + simple subject + post-modifier

- The man looking at us looks strange. (premodifier = the, post-modifier = looking at us)

- The goal of this gathering is to raise money for some poor kids. (premodifier = the, post-modifier = of this gathering)

Compound subject

A compound subject is a combination of two or more (generally two) simple subjects or complete subjects. It is joined by a coordinating conjunction, usually with ‘and’, ‘nor’, and ‘or’.

Examples:

- Jon and Max came to see me the other day.

- Susan or I can go there and talk to the mangement about this.

A compound subject can also be joined with correlative conjunctions such as ‘not only…but also‘, ‘Both…and‘, and ‘neither…not’.

- Neither the doctors nor the patients were happy with the ongoing protests.

- Both the police and the protestors are working together.

- Not only my parents but I am also in support of this rule.

What can be a subject?

A subject is generally a noun or a noun phrase but can be any of these:

- Noun

- Noun phrase

- Pronoun

- Noun clause

- Gerund

- Infinitive

Noun as a subject

A noun is a name given to something or someone. It’s generally a name of a person, place, thing, animal, emotion, concept, subject, activity, etc.

Examples:

- Mohit loves chocolates.

- Dubai is a beautiful city.

- Love overpowers hate.

- Honestly is the best policy.

Noun phrase as a subject

A noun phrase is a group of words headed by a noun. It has a noun and a word or words that modify it.

Examples:

- A man can do anything.

- A motivated man can achieve anything.

- Your house looks amazing.

- A tall girl came to my house yesterday.

- The man in the blue coat is waving at you.

Click here to study noun phrases in detail.

Pronoun as a subject

- You are amazing.

- She is studying right now.

- Everyone loves Ashish.

- There are 15 students in the classroom. All are studying.

- That is my house.

Noun clause as a subject

A subject can be a clause. Here are some examples:

- What he is eating is pancakes.

- What he wants is uncertain.

- Who you are hanging out with is a criminal.

- How she did this is shocking to us.

Click here to study noun clauses and noun clauses as the subject.

Gerund as a subject

A gerund is a progressive form of a verb that functions as a noun.

Examples:

- Dancing is my passion. (We are talking about an action: dancing. This action is not happening right now.

- Smoking can kill you.

- Teaching English is my passion.

- Talking to kids makes me happy.

The last examples of subjects are gerund phrases.

Study these topics in detail by clicking on them:

- Gerunds

- Gerund phrases

Infinitive as a subject

An infinitive is the ‘TO + V1’ form of a verb that functions as a noun, adjective, or adverb.

Examples:

- To go home is what I want right now.

- To start an NGO is my dream.

- To bring her back is difficult.

Related lessons to study:

- Infinitives in English

- Bare Infinitives

- Forms of Infinitives

2. PREDICATE

A predicate is a part of the sentence that gives information about the subject. It either indicates what the subject is doing or gives information about the subject in terms of giving it a name (using a noun) or modifying it (using an adjective).

Examples:

- She slept.

- She is working.

- You are a great human being.

- She is extremely talented.

Types of predicates in English

There are three types of predicates in English:

- Simple predicate

- Compound predicate

- Complete predicate

Simple predicate

A simple predicate is a verb or a verb phrase (a combination of an auxiliary verb and the main verb). It does not include ant objects or modifiers.

Examples:

- She works.

Here, ‘she’ is the simple subject, and ‘works‘ is the simple predicate.

- You can go.

In the sentence, ‘can go’ is the simple predicate. It is a combination of the auxiliary verb (can) and the main verb (go). You is the simple subject here.

- Jon has been sleeping.

Here, ‘Jon’ is the simple subject, and ‘has been sleeping‘ is the simple predicate.

- My mother is cooking my favorite dish.

In this sentence, the simple predicate is ‘is cooking’. The complete predicate is ‘is cooking my favorite dish’. The complete predicate is a combination of a simple predicate and the object of the verb.

- She called me right after the meeting ended.

‘Called’ is the simple predicate here. It is the main verb. Notice that the verb called has its object and modifier after it, but a simple predicate does not include anything other than a verb (main verb) and a verb phrase (auxiliary verb + main verb).

More examples of simple predicates

- She cries.

- It works.

- He finished the work.

- You have done this beautifully.

- Some of you may get a call in the evening.

- Some people never learn from their mistakes.

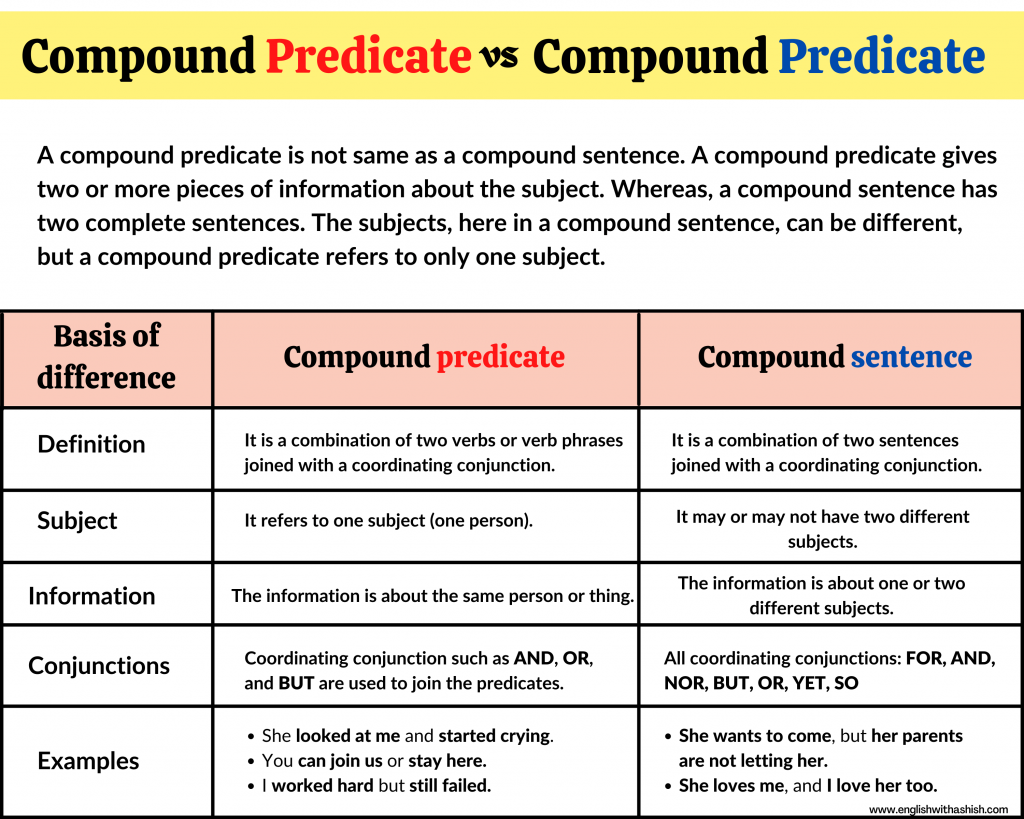

Compound predicate

A compound predicate is a combination of two verbs or verb phrases. The verbs of a compound predicate share the same subject. The verbs are joined with coordinating conjunctions such as ‘and‘, ‘or‘, or ‘but‘. Forming a compound predicate is a way to avoid repeating the subject.

Study the following example to see how a predicate fits into a sentence.

Rahul calls me every day. He tells me everything.

These are two sentences where the doer of both the actions is the same: Rahul. Calls and tells. These are two simple predicates. When a subject performs two or more actions, we can bring them together and avoid mentioning the subject again in a new clause.

Rahul calls me every day and tells me everything.

Now, we have brought these two predicates using the coordinating conjunction ‘and’.

More examples:

- They will hire you or let you go.

- The company has changed their policy and opened 5 new posts.

- I wanted to help you but didn’t have money.

- Joanna fell off the roof and broke her foot.

- Some of my friends moved to Dubai and bought houses there.

- I will call your parents and tell them everything you did.

- The movie was long but had an amazing storyline.

Complete predicate

A complete predicate is a combination of a simple predicate (verb) and the others parts of the sentence: objects, complements, and modifiers.

Examples:

- Jon Jones finished his career at the top.

Simple predicate = finished

Complete predicate = finished his career at the top

- You owe me 500 dollars.

Simple predicate = owe

Complete predicate = owe me 500 dollars

- You have been working hard lately.

Simple predicate = have been working

Complete predicate = have been working hard lately

I should have listened to my father that day.

Simple predicate = should have listened

Complete predicate = should have listened to my father that day

- They are sleeping.

‘Are sleeping’ is the simple predicate here. It does not have a complete sentence.

NOTE: a complete predicate must have more than a verb. It must include objects, complements, or modifiers. A verb or a verb phrase can’t be a complete predicate.

Parts of a predicate

Here are the things we have in a predicate:

- Verb or verb phrase

- Object

- Complement

- Adverb or adverbial

NOTE: A sentence can be formed using a subject and a verb or verb phrase, at minimum.

- Ron dances.

- She sings.

- We are working.

But sometimes, with the other information we want to render, that’s not enough.

- We are having dinner.

- Your sister wants some money.

- She has finished the assignment.

But it’s important to note that we need only two things to form a subject: a subject and a verb.

Verb and verb phrase

A verb in English either indicates the action the subject performs, or shows the state of the subject, or links the subject to its complement.

Examples (action):

- My parents help everyone.

- Ashish teaches amazingly.

- I am reading a book.

Examples (stative):

- We love this concept.

- I understand you.

- Jon appreciates your work.

A stative verb shows the state of the subject. Click here to study stative verbs and their types in detail.

Examples (linking):

- Ashish is a teacher. (Ashish = a teacher)

- Jon was a writer.

- You are great.

- These boys are notorious.

Linking verbs link the subject to a word or a group of words (subject complement) that gives information about the subject. Click here to study subject complement in detail.

Verb phrase

All these verbs (action, stative, and linking) are main verbs. Sometimes, main verbs are combined with an auxiliary verb to show the tense and the number of the subject.

Examples:

- They are playing there.

Verb phrase = are playing

Main verb = playing

Auxiliary verb = are

- Some students were dancing in the corridor.

Verb phrase = were dancing

Main verb = dancing

Auxiliary verb = were

- I have been sitting here.

Verb phrase = have been sitting

Main verb = sitting

Auxiliary verb = have been

- I have done it.

Verb phrase = have done

Main verb = done

Auxiliary verb = have

- You can do this.

Verb phrase = can do

Main verb = do

Auxiliary verb = can

Verbs phrases and tenses

| TENSES | VERB PHRASES | EXAMPLES |

| Present Indefinite tense | Do + V1 Does + V1 (only in negative and interrogative sentences) |

I do not like cheese. Do you have my number? Does she know you? Also used in an emphatic way: I do want to work with you. |

| Present Continuous tense | Is/am/are + present participle (V1+ing) | Jon is sleeping. |

| Present Perfect tense | Has/have + past participle (V3) | I have completed the project. Max has left the company. |

| Present Perfect Continuous tense | Has/have + been + present participle (V1+ing) | I have been teaching English since 2014. Sneha has been waiting for some time. |

| Past Indefinite tense | Did + V1 (only in negative and interrogative sentences) |

Did you see her last night? I did see you her night. (emphatic) |

| Past Continuous tense | was/were + present participle (V1+ing) | I was sleeping. We were studying. |

| Past Perfect tense | had + past participle (V3) | I had left his place when you called. |

| Past Perfect Continuous tense | Had + been + present participle (V1+ing) | We had been playing video games before the light went out. |

| Future Indefinite tense | Will/shall + V1 | I will call you soon. We shall do it. |

| Future Continuous tense | Will/shall + present participle (V1+ing) | We will be studying. |

| Future Perfect tense | will have + past participle (V3) | He will have left before us reaching. |

| Future Perfect Continuous tense | will have been + present participle (V1+ing) | He will have been sleeping. |

OBJECT

An object is a noun or a pronoun that receives the action. It is something or someone that the action is acted upon. It sometimes is needed to complete the meaning of the verb. Only transitive verbs take an object. Intransitive verbs can’t do that.

NOTE: an object is not always necessary to have a grammatical sentence. But with certain verbs, it’s vital to use the object of the verb to make the sentence grammatical and complete.

- I have a lot of money.

Have what? The sentence doesn’t give a clear meaning without the object. Here, the object (a lot of money) is needed to complete the sentence.

- Do you want my help?

Want what? The sentence again looks incomplete with the object (my help).

But an object is not always needed for the grammatical sanctity of the sentence. Intransitive verbs don’t take an object. Here are some examples:

- Jon slept late.

- Keep smiling.

- You can sit on my seat.

- I was shivering whem you called.

Can you sleep someone or something? No, right? You can sleep with someone or something but someone/something can’t receive this action directly. Similarly, smile, sit, and shiver are intransitive verbs. You can’t smile, sit and shiver someone or something.

Sometimes, you can avoid using a direct object after a transitive verb either. The sentence remains grammatical without it. Here are some examples to study:

- I am studying right now. Call me later.

You study something (direct object). But here, the object has not been mentioned as it’s not important or the speaker does not want to share it.

- I don’t feel like eating right now.

Eat is a transitive verb; you can eat something. But here, the object of the verb hasn’t been used, and the sentence is still grammatical without it.

Notice, the sentences make sense without the objects (italicized). But adding the object does make the sentence better. But it’s important to note that with some verbs, objects need to be used always.

A few verbs: want, love, need, have, hate, desire, admire, make

Types of objects

There are two types of objects in English:

- Direct object

- Indirect object

A direct object is someone or something that directly receives the action. It answers the question ‘what’ or ‘whom’.

An indirect object receives the direct object. It is generally a person whom the action is done for. It answers the question ‘for whom’ or ‘to whom’.

Examples:

- I love you.

Direct object (love ‘whom’)= you

- Max plays the piano.

Direct object (play ‘what’) = the piano

- My mother gave me a phone.

Direct object (gave what) = a phone

Indirect object (who received it) = me

- Jon gifted us a dog.

Direct object (gifted what) = a dog

Indirect object (who received it) = us

Notice, in the last two examples, the indirect object receives the direct object.

Some verbs always take both direct and indirect objects, and that’s why they become a part of a sentence. Here are a few of them:

- Gift

- Give

- Pass

- Lend

- Get

Related posts:

- Direct and objects

- 4 types of objects in English

- Ditransitive verbs

COMPLEMENT

A complement is a word or a group of words that gives information about something in a sentence and completes its meaning. The core meaning of the sentence changes if the complement is removed from it.

Types of complements in English

- Subject complement

- Object complement

- Verb complement

- Adjective complement

- Adverbial complement

| TYPES OF COMPLEMENTS | DEFINITION | EXAMPLES | WHAT CAN PLAY THE ROLE? |

| Subject complement | A subject complement is a word or a group of words that comes after a linking verb and gives information about the subject. It either renames the subject (using a noun) or modifies it (using an adjective). | 1. Tarang is a businessman.

Subject complement = a business (noun phrase, renaming the subject) 2. His journey has been very difficult. |

Predicative nominative (noun or noun equivalent) or Predicative adjective (adjective or prepositional phrase) |

| Object complement | An object complement is something that complements the direct object: indicates that the object has become. It either renames the object (using a noun) or modifies it (using an adjective). |

1. My friends call me a genius. 2. You made Ashish upset |

Noun or adjective |

| Verb complement | A verb complement is usually an object that comes after a verb and completes its meaning. Without the verb complement, the sentence stops giving the same meaning and looks incomplete. |

1. We enjoyed watching this show. 2. She gave me a beautiful car. |

direct object and indirect object (noun/pronoun) |

| Adjective complement | An adjective complement is a phrase or a clause that completes the meaning of an adjective by giving more information about it. The information helps the readers or listeners to understand the situation better. So, the information it provides is necessary in order to complete the meaning of the adjective. |

1. I am not happy with your performance. Here, ‘with your performance’ is a prepositional phrase that’s working as an adjective complement. If we ended the sentence with the adjective happy, we wouldn’t have more clarity about the sentence. We wouldn’t know what the speaker is unhappy with. 2. I am happy to see you again. ‘To see you again’ is an infinitive phrase that’s coming next to the adjective ‘happy’ and telling us the reason for this state of existence. |

1. Prepositional phrase 2. Adjective clause 3. Infinitive phrase |

| Adverbial complement | An adverbial complement is an adverb or an adverbial that completes the meaning of a verb. It helps the sentence renders the meaning it intends to give. Taking an adverbial complement out of a sentence changes the core meaning of the sentence. |

1. Don’t put me in his group. 2. I love coming here. Here, the adverb ‘here’ is a complement to the verb ‘coming’. You don’t just come; you come to a place. So, mentioning the place is important. |

1. Prepositional phrase 2. Adverb |

SUBJECT COMPLEMENT

A subject complement is a word or a group of words that comes after a linking verb and gives information about the subject. It either renames the subject (using a noun) or modifies it (using an adjective).

Examples:

- My father is an accountant.

Linking verb = is

Subject complement = an accountant (noun phrase, renaming the subject)

- Aakriti was the head of my team.

Linking verb = was

Subject complement = the head of my team (noun phrase, renaming the subject)

- You are amazing.

Linking verb = amazing

Subject complement = amazing (adjective, modifying the subject)

- I am happy.

Linking verb = am

Subject complement = happy (adjective, modifying the subject)

A prepositional phrase can also act as a subject complement, modifying the subject.

Examples:

- We are under pressure.

- She is in heavy debts.

- Max is in London.

NOTE: subject complements are absolutely necessary to complete a sentence and make it grammatical. Without them, sentences are incomplete and ungrammatical.

Related posts:

- Linking verbs

- Subject complement

OBJECT COMPLEMENT

An object complement is something that complements the direct object: indicates that the object has become. It either renames the object (using a noun) or modifies it (using an adjective).

Examples:

- My friends call me a genius.

Direct object = me

Object complement = a genius (noun phrase)

Removing the object complement changes the meaning of the sentence. Here, the verb ‘call’ doesn’t mean to ring. It’s used differently. They call me what? We need to know that.

- My company made him the branch manager.

Direct object = him

Object complement = the branch manager (noun phrase)

Ask again: the company made him what? The sentence looks incomplete without the object complement.

- You made Ashish upset

Direct object = Ashish

Object complement = upset (adjective)

Here, the object complement indicates what Ashish has become: upset. It refers to the change in his state of being.

NOTE: there are only certain verbs (with a certain meaning) that will take an object complement. Only with these verbs do we need an object complement. Else, it’s not an essential part of a sentence.

Verbs that take a direct object and an object complement:

- Make

- Call

- Name

- Consider

- Elected

VERB COMPLEMENT

Verb complement definition: a verb complement is usually an object that comes after a verb and completes its meaning. Without the verb complement, the sentence stops giving the same meaning and looks incomplete.

- Do you mind switching our seats?

‘To mind’ means to dislike. You just can’t mind; you mind something. There has to be something that you mind. I can mind your behavior, living with you, your touching me, someone living in my house, and so on. But I can’t just mind.

- I hope that you win this competition.

Here, the noun clause coming after the verb ‘hope’ is its complement. You don’t just hope; you hope something. Here, the noun clause is the verb’s complement. Without the complement, the sentence (I hope) looks incomplete.

ADJECTIVE COMPLEMENT

An adjective complement is a phrase or a clause that completes the meaning of an adjective by giving more information about it. The information helps the readers or listeners to understand the situation better. So, the information it provides is necessary in order to complete the meaning of the adjective.

I was unhappy to go there alone.

The infinitive phrase (in red) gives us information about the adjective (unhappy) and working as its complement. Without it, the sentence gives a different meaning.

Examples:

- We are excited to attend the party.

- His family and friends were devastated to hear the news of his death.

- We are really excited about Jon’s wedding.

- I am delighted that all my students have passed the exams.

ADVERBIAL COMPLEMENT

An adverbial complement is an adverb or an adverbial that completes the meaning of a verb. It helps the sentence renders the meaning it intends to give. Taking an adverbial complement out of a sentence changes the core meaning of the sentence; it takes an essential part of the sentence, unlike an adjunct.

- Don’t aim for a money fight.

‘For a money fight’ is the adverbial complement here. It is a prepositional phrase that is complementing the verb and helping it complete the correct meaning of the sentence. When used as an intransitive verb, it is followed by a prepositional phrase starting with either ‘for’ or ‘at’.

- We are aiming at the manager’s post.

When you aim at something; you plan to achieve it. Without using the prepositional phrase starting (at + object), this meaning can’t be delivered. Without the verb complement (We are aiming), the sentence is incomplete and does not render the intended meaning.

ADVERB

An adverb is a word or a group of words that modifies a verb, adjective, or adverb.

When it modifiers a verb, it tells us the following things:

- Time of the action

- Place of the action

- Manner of the action

- Reason of the action

Adverbs (verb modifiers) are not usually essential for the sentence, but they make the sentence more informative.

Examples:

- I went there in the evening. (place, time)

- Sam is playing upstairs. (place)

- She acts like a small baby. (manner)

- Jon is doing this to earn some extra bucks. (reason)

Adverbs can modify adjectives too. Here are some examples:

- We are not positive about the next game. (modifying the adjective ‘positive’)

- Ashish is delighted to work with us. (modifying the adjective ‘delighted’)

Adverbs can modify adverbs or complete sentences. Here are some examples:

- Fortunately, I was there to help her. (modifying the main clause)

- Jacob runs very fast. (modifying the adverb ‘fast’)

Important points to note

A) A sentence can be formed only with a subject and a verb.

There are two things we need in order to form a sentence, that is a subject and a verb.

Examples:

- We work.

- Jon cries.

- I am typing.

Note that it’s not always possible to form a sentence with these two elements. Sometimes, you need other parts like objects, subject complements, and object complements too. The selection of the elements you need to form a sentence is decided by the information you want to render.

B) A linking verb takes a subject complement.

If a sentence has a linking verb (main verb), it has to follow a subject complement. The sentence would be incomplete without a subject complement if the main verb is a linking verb.

Examples:

- My father is a doctor.

Here, my father is a subject complement. The sentence without it (My father is) incomplete. So, it’s not that you can always form a sentence with a subject and a verb. The type of the verb and what you want to say decide the elements that need to be there in a sentence (essential elements).

More examples:

- You will be very successful someday.

- We are grateful to you.

- They were great dancers.

C) Some verbs must have an object to complete the meaning of the sentence.

- I have.

- We need.

- My brother owns.

Do these sentences make complete sense? These are incomplete without the direct object. Let’s complete them adding an object of the verb.

- I have his number.

- We need some food.

- My brother owns this house.

PRACTICE SET!

Find out the subjects in the following sentences:

1. The main problem with you is your ego.

2. Some people don’t listen to anyone.

3. Either you or Max can get it done.

4. Looking at the old pictures of his mother, he started crying.

5.No-one wants to work with you anymore.

6. People who do yoga daily rarely get sick.

7. What I really want is to help you in this.

8. To go there at this time can be really dangerous.

9. Arresting his family would not help him to confess the crime.

10. Identifying the problem is the first step to remove the problem.

Answers:

- Complete subject = the main problem with you, simple subject = problem

- Complete subject = some people, simple subject = people

- Compound subject = either you or Max

- Simple subject = he

- Simple subject = no-one

- Complete subject = people who do yoga daily, simple subject = people

- Complete subject = what I really want

- Complete subject = to go there alone at this time

- Complete subject = arresting his family

- Complete subject = identifying the problem

Now you know what a sentence is and what essential parts it has. Do share the lesson with others to help, and do share your questions and doubts in the comment section.

For one-on-one classes, contact me at [email protected]

FAQs

What are the basic parts of a sentence?

The basic parts of a sentence contain the subject and the verb/verb phrase.

Examples:

1. You sleep.

2. We cry.

But these are, sometimes, not enough to give proper information. We need objects and complements.

What are the 5 elements of a sentence?

These are the five elements in a sentence in English:

1. Subject

2. Verb

3. Object

4. Complement

5. Adjunct

Ex – She made me happy at the party. (She = subject, made = verb, me = object, happy = object complement, at the party = adjunct)

How do you form a sentence?

There are several ways to form a sentence, depending upon the information one wants to render. The most common structures are the following:

1. Subject + verb + object

2. Subject + verb + complement

Examples:

1. They love Ashish.

2. Ashish is an English teacher.

What are the 6 sentence patterns?

Here are 6 different sentence structures in English:

1. Subject + verb

2. Subject + verb + object

3. Subject + verb + subject complement

4. Subject + verb + object + object complement

5. Subject + verb + adjunct

6. Subject + verb + subject complement + adjunct

English is a beautiful language, and one of its many perks is the one-word sentences. One-word sentences — as the name suggests is a sentence with a single word, and which makes total sense.

One word sentences can be used in different forms. It could be in form of a question such as “Why?” It could be in form of a command such as “Stop!” Furthermore, it could be used as a declarative such as “Me.” Also, a one-word sentence could be used to show location, for example, “here.” It could also be used as nominatives e.g. “David.”

Actually, most of the words in English can be turned into one-word sentences. All that matters is the context in which they are used. In a sentence, there is usually a noun, and a verb. In a one-word sentence, the subject and the action of the sentence is implied in the single word, and this is why to understand one-word sentences, one has to understand the context in which the word is being used.

Saying only a little at all times is a skill most people want to learn; knowing when to use one-word sentences can help tremendously. However, you cannot use one-word sentences all the time so as robotic or come off as rude.

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

- Help: This signifies a call for help.

- Hurry: Used to ask someone to do something faster

- Begin: Used to signify the beginning of a planned event.

Basically, the 5 Wh-question words — where, when, why, who and what? can also stand as one-word sentences.

By Bizhan Romani

Dr. Bizhan Romani has a PhD in medical virology. When it comes to writing an article about science and research, he is one of our best writers. He is also an expert in blogging about writing styles, proofreading methods, and literature.

What does a conjunction do?Where is a conjunction used?What is a conjunction? Here we have answers to all these questions! Conjunctions, one of the English parts of speech, act as linkers to join different parts of a sentence. Without conjunctions, the expression of the complex ideas will seem odd as you will have to use…

Introduction An adverb is a word that modifies a sentence, verb, or adjective. An adverb can be a word or simply an expression that can even change prepositions, and clauses. An adverb usually ends only- but some are the same as their adjectives counterparts. Adverbs express the time, place, frequency, and level of certainty. The…

What is a noun?What are all types of nouns?How is a noun used in a sentence? A noun is referred to any word that names something. This could be a person, place, thing, or idea. Nouns play different roles in sentences. A noun could be a subject, direct object, indirect object, subject complement, object complement,…

What is a pronoun?How is a pronoun used in a sentence?What are all types of pronouns? A pronoun is classified as a transition word and a subcategory of a noun that functions in every capacity that a noun will function. They can function as both subjects and objects in a sentence. Let’s see the origin…

In the English language, sentence construction is quite imperative to understanding. A sentence can be a sequence, set or conglomerate of words that is complete in itself as it typically contains a subject, verb, object and predicate. However, this sentence regardless of its intent, would be chaotic if not constructed properly. Proper sentence construction helps…

In this article, we will discuss what is sentence in English?, Parts of sentence, and Types of sentences: Declarative, Interrogative, Imperative, and Exclamatory sentences.

A sentence is a group of words that helps a person to express himself.

In every communication, there is a need of a group of words to communicate. Such a group of words, which can communicate a complete message is called a sentence.

For Example:

- I am going to school.

- James is a doctor.

- What is your name?

- My name is Tony.

In any language,

- Letters help in making words.

- Words help in making Sentences.

- Sentences help in making Paragraphs.

Actually, a sentence is a collection of meaningful words that helps to share our thoughts or ideas with other persons.

To write or speak any language, you need words. These meaningful word helps to create a sentence which helps a person to express himself.

A sentence can be one word or more than one word, means if a single word is sufficient to express himself than that word is also a sentence.

For example,

- Mother: Do you want to go to school?

- Son: No.

- Mother: Why?

- Son: I am not feeling well today.

In the above example, all are the sentences, because all these single words are sufficient to express himself. If you convey a message in a single word, so that is also called a sentence.

A group of words doesn’t mean it makes a sentence, those words which make complete sense (you can understand), is called a Sentence.

Actually, Sentences are arranged in a systematic way that gives us complete sense.

Example 1:

- Rahul is reading a book. ✔

- book rahul a reading is. ✘

Example 2:

- John is a Good Boy. ✔

- Boy is good John. ✘

Parts of Sentence

Every sentence consists of two parts:

Subject + Predicate

Subject:

A subject is what we are talking about. It can be a noun or pronoun that performs some action.

What is being told about that sentence is the subject of that sentence.

The subject is a noun or pronoun, which has been being talked about or that which is doing that work.

Predicate:

Predicate shows some details about the subject. It contains a verb that explains about the subject or what subject is doing and also contains objects that are affected by the subject’s actions.

For Example,

- I love you.