What is the emotional meaning of a word called?

connotation

What is the implied meaning of a word called?

The connotation of a word or phrase is the associated or secondary meaning; it can be something suggested or implied by a word or thing, rather than being explicitly named or described. …

What are the emotional associations of terms called?

Connotation is the emotional and imaginative association surrounding a word. Denotation is the strict dictionary meaning of a word. connotation as the emotional weight of a word, comparing cheap to inexpensive as an example.

What does the word emotion stand for?

1a : a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) subjectively experienced as strong feeling usually directed toward a specific object and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body. b : a state of feeling. c : the affective aspect of consciousness : feeling.

What are the 7 human emotions?

Here’s a rundown of those seven universal emotions, what they look like, and why we’re biologically hardwired to express them this way:

- Anger.

- Fear.

- Disgust.

- Happiness.

- Sadness.

- Surprise.

- Contempt.

What is the root word of emotion?

The word emotion comes from the Middle French word émotion, which means “a (social) moving, stirring, agitation.” We feel many different emotions every day, like love, fear, joy and sadness — just to name a few.

What are the 4 core emotions?

There are four kinds of basic emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, and anger, which are differentially associated with three core affects: reward (happiness), punishment (sadness), and stress (fear and anger).

What are the 30 emotions?

Robert Plutchik’s theory

- Fear → feeling of being afraid , frightened, scared.

- Anger → feeling angry.

- Sadness → feeling sad.

- Joy → feeling happy.

- Disgust → feeling something is wrong or nasty.

- Surprise → being unprepared for something.

- Trust → a positive emotion; admiration is stronger; acceptance is weaker.

How many emotions are there?

27

What is the rarest emotion?

10 Obscure Emotions That Actually Exist – And Their Names [VIDEOS]

- 1 – Sonder. Sonder is that feeling when you realize that everyone you see, everyone who passes you by has their own complex life.

- 2 – Zenosyne.

- 3 – Chrysalism.

- 4 – Monachopsis.

- 5 – Lachesism.

- 6 – Rubatosis.

- 7 – Klexos.

- 8 – Jouska.

What is the strongest emotion?

Fear

What emotions do humans feel?

During the 1970s, psychologist Paul Eckman identified six basic emotions that he suggested were universally experienced in all human cultures. The emotions he identified were happiness, sadness, disgust, fear, surprise, and anger.

Is love an emotion or feeling?

Love is not an emotion; it doesn’t behave the way emotions do. When we love truly, we can experience all our free-flowing, mood state, and intense emotions (including fear, rage, hatred, grief, and shame) while continuing to love and honor our loved ones. Love isn’t the opposite of fear, or anger, or any other emotion.

How do I identify my emotions?

Identifying Your Feelings

- Start by taking your emotional temperature.

- Identify your stressors.

- Notice if you start judging what you feel.

- Speak about your feelings, and let go of the fear.

What are the 10 basic emotions?

10 Basic Emotions and What They’re Trying To Tell You

- Happiness. One of the first core emotions we all experience is happiness.

- Sadness. Next comes sadness, an emotion that we feel whenever we experience the loss of something important in our lives.

- Anger.

- Anticipation.

- Fear.

- Loneliness.

- Jealousy.

- Disgust.

What are examples of emotion?

Here’s a look at what each of these five categories involves.

- Enjoyment. People generally like to feel happy, calm, and good.

- Sadness. Everyone feels sad from time to time.

- Fear. Fear happens when you sense any type of threat.

- Anger. Anger usually happens when you experience some type of injustice.

- Disgust.

What are the 10 positive emotions?

Frederickson (2009) identifies the ten most common positive emotions as joy, gratitude, serenity, interest, hope, pride, amusement, inspiration, awe and love. She also noted that we really need a 3:1 ratio of positive to negative in order to have a good life.

What is your emotional self?

Emotional Self-Awareness is the ability to understand your own emotions and their effects on your performance. You know what you are feeling and why—and how it helps or hurts what you are trying to do. You sense how others see you and so align your self-image with a larger reality.

What is the example of emotional self?

For example, you can benefit from learning who you are and how your buttons are pushed by different things. Furthermore, emotional self-awareness allows you to recognize situations when emotions like fear, frustration, and anger start to control you. These emotions are obviously negative for your happiness.

Is self control an emotion?

Emotional Self-Control is the ability to keep your disruptive emotions and impulses in check, to maintain your effectiveness under stressful or even hostile conditions. With Emotional Self-Control, you manage your disruptive impulses and destabilizing emotions, staying clear-headed and calm.

Why is emotional self important?

It is an important skill for leadership at any level, as well as many aspects of life. The purpose of developing Emotional Self-Awareness is that it allows us to understand how our bodily sensations and our emotions impact ourselves, others, and our environment. Each moment is an opportunity to be self-aware.

How can I improve my emotional self?

Lists 10 tips for improving your self awareness.

- Get out of the comfort zone.

- Identify your triggers.

- Do not judge your feelings.

- Don’t make decisions in a bad mood.

- Don’t make decisions in a good mood either.

- Get to the birds-eye view.

- Look for your emotions in the media.

- Revisit your values and act accordingly.

How do I control my self emotions?

Here are some pointers to get you started.

- Take a look at the impact of your emotions. Intense emotions aren’t all bad.

- Aim for regulation, not repression.

- Identify what you’re feeling.

- Accept your emotions — all of them.

- Keep a mood journal.

- Take a deep breath.

- Know when to express yourself.

- Give yourself some space.

What are the benefits of controlling your emotions?

Emotions are powerful. Your mood determines how you interact with people, how much money you spend, how you deal with challenges, and how you spend your time. Gaining control over your emotions will help you become mentally stronger. Fortunately, anyone can become better at regulating their emotions.

Why can’t I express my emotions?

What to know about alexithymia. Alexithymia is when a person has difficulty identifying and expressing emotions. It is not a mental health disorder. People with alexithymia may have problems maintaining relationships and taking part in social situations.

How do I stop repressing emotions?

Things you can try right now

- Check in. Ask yourself how you feel right now.

- Use “I” statements. Practice expressing your feelings with phrases like “I feel confused.

- Focus on the positive. It might seem easier to name and embrace positive emotions at first, and that’s OK.

- Let go of judgement.

- Make it a habit.

How do emotions affect communication?

Feelings play a big role in communication. If you are emotionally aware, you will communicate better. You will notice the emotions of other people, and how the way they are feeling influences the way they communicate. You will also better understand what others are communicating to you and why.

How do you communicate with someone who is emotional?

6 Ways To Keep Your Cool When Dealing With Overly Emotional People

- Don’t: Call them too emotional.

- Do: Ask what they’re feeling.

- Don’t: Say, “I know how you feel,” if you don’t.

- Do: Say you want to understand how they feel.

- Don’t: Get angry.

- Do: Say it’s okay.

- Don’t: Try to combat the emotions with logic.

What are emotions in communication?

Emotions result from outside stimuli or physiological changes that influence our behaviors and communication. Emotions developed in modern humans to help us manage complex social life including interpersonal relations. The expression of emotions is influenced by sociocultural norms and display rules.

How do emotions affect relationships?

If you become upset or angry, it can make things very difficult, and it’s also hard to trust someone who is mad at you. If emotional upset happens on a regular basis, your relationship will be unable to grow, and it will slowly degrade if you don’t find a way to be nice to each other again.

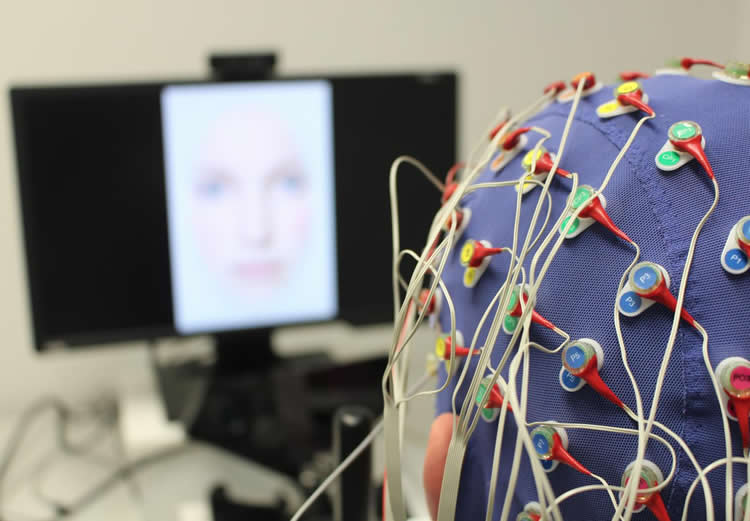

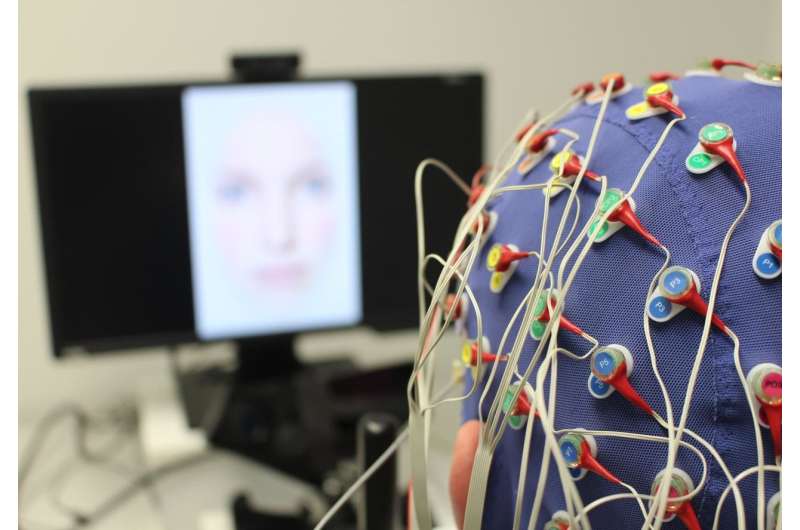

Summary: Researchers used EEG to investigate how the brain processes stimuli to determine whether an image or word is positive or negative. The study found words associated with loss causes neural reactions in the visual cortex after 100 milliseconds.

Source: University of Gottigen.

Many objects and people in everyday life have an emotional meaning. A pair of wool socks, for example, has an emotional value if it was the last thing the grandmother knitted before her death. The same applies to words. The name of a stranger has no emotional value at first, but if a loving relationship develops, the same name suddenly has a positive connotation. Researchers at the University of Göttingen have investigated how the brain processes such stimuli, which can be positive or negative. The results were published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

The scientists from the Georg Elias Müller Institute for Psychology at the University of Göttingen analysed how people associate neutral signs, words and faces with emotional meaning. Within just a few hours, participants learn these connections through a process of systematic rewards and losses. For example, if they always receive money when they see a certain neutral word, this word acquires a positive association. However, if they lose money whenever they see a certain word, this leads to a negative association. The studies show that people learn positive associations much faster than neutral or negative associations: something positive very quickly becomes associated with a word or indeed with the face of a person (as their recent research in Neuroimage has shown).

Using electroencephalography (EEG), the researchers also investigated how the brain processes the various stimuli. The brain usually determines whether an image or word is positive or negative after about 200 to 300 milliseconds. “Words associated with loss cause specific neuronal reactions in the visual cortex after just 100 milliseconds,” says Dr Louisa Kulke, first author of the study. “So the brain distinguishes in a flash what a newly learned meaning the word has for us, especially if that meaning is negative.”

It also seems to make a difference whether the word is already known to the subject (like “chair” or “tree”) or whether it is a fictitious word that does not exist in the language (like “napo” or “foti”). Thus, the existing semantic meaning of a word seems to play a role in the emotions that we associate with that word.

About this neuroscience research article

Source: Melissa Sollich – University of Gottigen

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Anap-Lab.

Original Research: Abstract for “Differential effects of learned associations with words and pseudowords on event-related brain potentials” by Louisa Kulke, Mareike Bayer, Anna-Maria Grimm,and Annekathrin Schacht in Neuropsychologia. Published December 17 2018.

doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.12.012

Cite This NeuroscienceNews.com Article

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]University of Gottigen”How Words Get an Emotional Meaning.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 9 January 2019.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]University of Gottigen(2019, January 9). How Words Get an Emotional Meaning. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved January 9, 2019 from https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]University of Gottigen”How Words Get an Emotional Meaning.” https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/ (accessed January 9, 2019).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Differential effects of learned associations with words and pseudowords on event-related brain potentials

Associated stimulus valence affects neural responses at an early processing stage. However, in the field of written language processing, it is unclear whether semantics of a word or low-level visual features affect early neural processing advantages. The current study aimed to investigate the role of semantic content on reward and loss associations. Participants completed a learning session to associate either words (Experiment 1, N = 24) or pseudowords (Experiment 2, N = 24) with different monetary outcomes (gain-associated, neutral or loss-associated). Gain-associated stimuli were learned fastest. Behavioural and neural response changes based on the associated outcome were further investigated in separate test sessions. Responses were faster towards gain- and loss-associated than neutral stimuli if they were words, but not pseudowords. Early P1 effects of associated outcome occurred for both pseudowords and words. Specifically, loss-association resulted in increased P1 amplitudes to pseudowords, compared to decreased amplitudes to words. Although visual features are likely to explain P1 effects for pseudowords, the inversed effect for words suggests that semantic content affects associative learning, potentially leading to stronger associations.

Feel free to share this Neuroscience News.

Many objects and people can convey an emotional meaning. A pair of wool socks, for example, has an emotional value if it was the last thing the grandmother knitted before her death. The same applies to words. The name of a stranger has no emotional value at first, but if a loving relationship develops, the same name suddenly has a positive connotation. Researchers at the University of Göttingen have investigated how the brain processes such stimuli, which can be positive or negative. The results were published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

The scientists from the Georg Elias Müller Institute for Psychology at the University of Göttingen analysed how people associate neutral signs, words and faces with emotional meaning. Within just a few hours, participants learn these connections through a process of systematic rewards and losses. For example, if they always receive money when they see a certain neutral word, this word acquires a positive association. However, if they lose money whenever they see a certain word, this leads to a negative association. The studies show that people learn positive associations much faster than neutral or negative associations: Something positive very quickly becomes associated with a word, or indeed, with the face of a person (as their recent research in Neuroimage has shown).

Using electroencephalography (EEG), the researchers also investigated how the brain processes the various stimuli. The brain usually determines whether an image or word is positive or negative after about 200 to 300 milliseconds. «Words associated with loss cause specific neuronal reactions in the visual cortex after just 100 milliseconds,» says Dr. Louisa Kulke, first author of the study. «So the brain distinguishes in a flash what a newly learned meaning the word has for us, especially if that meaning is negative.»

It also seems to make a difference whether the word is already known to the subject (like «chair» or «tree») or whether it is a fictitious word that does not exist in the language (like «napo» or «foti»). Thus, the existing semantic meaning of a word seems to play a role in the emotions that we associate with that word.

More information:

Louisa Kulke et al, Differential effects of learned associations with words and pseudowords on event-related brain potentials, Neuropsychologia (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.12.012

Provided by

University of Göttingen

Citation:

How words get an emotional meaning (2019, January 10)

retrieved 14 April 2023

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-01-words-emotional.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Translation of words

with emotive meaning

Emotive

meaning may be regarded as one of the objective semantic features

proper to words as linguistic units and should not be confused with

contextual emotive meaning that words may acquire in speech. Emotive

meaning varies in different word classes. In some

of them, for example, in interjections, the emotive element prevails

whereas in function words it is practically non-existent.

The

emotion meaning is based on connotations — positive, negative or

neutral. Russian is rich in emotive suffixes whose meaning is

rendered

by using additional lexical items (e.g. домишко

— small, wretched house) or different lexemes (cf.: дом

— house, домишко

-hovel).

Some

words may acquire a negative or positive connotation in different

contexts. The noun «glamour» and the adjective «glamorous»

may

illustrate this point. The following examples are from Somerset

Maugham: R. was captivated by the vulgar glamour and the shoddy

brilliance of the scene before him. P. Был

пленен

вульгарным

блеском

и

дешевой

роскошью

окружающего.

(As a matter of fact both

collocations «vulgar glamour» and «shoddy brilliance»

are synonymous):

…who

were attracted for the moment by the glamour of the dancer or the

blatant sensuality of the woman. — …которых

на

мгновение

привлек

романтический

ореол

танцовщицы

или

её

откровенная

чувственность.

Cf.:

the following example from a newspaper review:

Hirsh’s

Richard is not lacking in glamour. Facially he is a smiling fallen

angel (The Observer Review, 1973). Ричард

в исполнении Хирша не лишен обаяния. У

него лицо улыбающегося падшего ангела.

Sometimes

differences in usage or valency do not allow the use of the Russian

referential equivalent, and the translator is forced to resort

to a lexical

replacement

with the emotive meaning preserved.

In

the general strike, the fight against the depression, the antifascist

struggle, and the struggle against Hitlerism the British Communist

Party played a proud

role (The Labour Monthly, 1970).

Во

время всеобщей забастовки, в борьбе

против кризиса, в антифашистской борьбе

против Мосли и против гитлеризма

Коммунистическая

партия Великобритании играла выдающуюся

роль.

The

emotive meaning of some adjectives and adverbs is so strong that it

suppresses the referential meaning (I. R. Galperin. Stylistics.

M.,1971, p.60.) and they are used merely as intensifies. They are

rendered by Russian intensifies irrespective of their reference. i_

Even

judged by Tory standards, the level of the debate on the devaluation

of the pound yesterday was abysmally

low

(M.S., 1973).

Даже

с точки зрения консерваторов дебаты в

Палате общин по вопросу о девальвации

фунта происходили на чрезвычайно

/невероятно/

низком уровне.

The

emotive meaning often determines the translator’s choice. The English

word «endless» is neutral in its connotations, while the

Russian бесконечный

has negative connotations — boring or tiresome (бесконечные

разговоры).

Thus, in the translation of the phrase

«the endless resolutions received by the National Peace

Committee» the word «endless» should be translated by

Russian adjective

«бесчисленные»

or «многочисленные».

Многочисленные

резолюции,

полученные

Национальным

комитетом

защиты

мира.

The Russian word «озарила»

conveys positive connotations, e.g. «Ее

лицо

озарила

улыбка»,

where as its English referential equivalent

is evidently neutral. Horror dawned

in her face (Victoria Holt). A possible translation will be: Её

лицо

выразило

ужас.

Rendering of Stylistic

Meaning in Translation

Every

word is stylistically marked according to the layer of the vocabulary

it belongs to. Stylistically words can be subdivided into literary

and non-literary.

(See I. R. Galperin, op. cit. — p.63.) The stylistic function of the

different strata of the English vocabulary depends

not so much on the inner qualities of each of the groups as on their

interaction when opposed to one another.(l. R. Galperin, op. cit. —

p.68.) Care should be taken to render stylistic meaning

If

you don’t keep

your yap

shut«…»

(J.Salinger)

Если ты не заткнёшься /пер. Э.

Медниковой/

Then he really let

one go at me

(ibid.) — Тут

он

мне

врезал

по-настоящему.

It

would be an error to translate a neutral or a literary word by a

colloquial one. A mistake of this type occurs in the excellent

translation

of Henry Esmond by E. Kalashnikova:

«She

had recourse to the ultimo ratio of all women and burst into tears.»

— «Она

прибегла

к

ultimo ratio всех

женщин

и

ударилась

в

слёзы».

Translation of

Phraseological Units

Phraseological units may be

classified into three big groups:

phraseological fusions,

phraseological unities and phraseological collocations.

Phraseological

fusions are usually rendered by interpreting translation: to show the

white feather — быть

трусом;

to dine with Duke Humphry

— остаться

без

обеда.

Sometimes they have word-equivalents: red tape — волокита,

to pull one’s leg — одурачивать,

мистифицировать.

The

meaning of a phraseological fusion may often be rendered by a series

of alternative phrases, e.g. to go the whole hog -делать

что-либо

основательно,

доводить

до

конца,

не

останавливаться

на

полумерах,

идти

на

всё

(словарь

А.Кунина).

According

to the principles of their translation phraseological unities can be

divided into four groups;

1)

Phraseological

unities having Russian counterparts with the same meaning and

simailar images. They can often be traced to the same

prototype: biblical, mythological, etc.

All

that glitters is not gold. — He всё

золото,

что

блестит.

As

a man sows, so he shall reap. — Что

посеешь,

то

и

пожнёшь.

2)

Phraseological

unities having the same meaning but expressing it through

a—different-

image.

То

buy

a

pig

in

a

poke.

— Купить кота в мешке.

Phraseological

units of the source-language sometimes have synonymous equivalents in

the target-language. The choice is open to

the translator and is often determined by the context.

Between

the

devil

and

the

deep

sea

— между двух огней, между молотом и

наковальней; в безвыходном положении.

In

the absence of a correlated phraseological unity the translator

resorts to interpreting translation.

A

skeleton

in

the

closet

(cupboard)

— Семейная тайна, неприятность, скрываемая

от посторонних.

Target-language

equivalents having a local colour should be avoided. «To carry

coals to Newcastle» should not be translated by the Russian —

ездить

в

Тулу

со

своим

самоваром.

In this case two solutions are possible: a) to preserve the image of

the English phraseological unity — ездить

в

Ньюкасл

со

своим

углём,

b) to resort to interpreting translation — заниматься

бесполезным

делом.

-

Phraseological

unities having no equivalents in Russian are rendered by

interpreting translation. Little

pitches

have

long

ears.

— Дети

лобят слушать разговоры взрослых. -

Phraseological

unities having word equivalents: shake a leg — отплясывать,

hang fire-мешкать,медлить,задерживаться.Translation

of Phraseological Collocations

Phraseological

collocations are motivated but they are made up of words possessing

specific lexical valency which accounts for a certain

degree of stability in such word groups.

They

may be translated by corresponding phraseological collocations of the

target-language: to take part — принимать

участие,

to throw a glance — бросить

взгляд.

They may be also translated by a word (to take part — участвовать)

or a free word group (to take one’s

temperature — измерить

температуру).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Introduction: Where are the Emotions in Words?

We text, blog, twitter and tweet, we write each other emails, poems and love letters. Ever since in human history, people have been using language to communicate emotions and feelings, well knowing that words can hurt or heal. Thus, considering everyday experiences, there is no doubt that written language constitutes a most powerful tool for inducing emotions in self and others—and for eliciting emotional responses in the sender and perceiver of a message even when no direct face to face communication is possible.

However, what happens so naturally and effortlessly in everyday life has become a subject of intensive scientific debate. Can language, specifically written language in terms of single words elicit emotions? And if so, where are the emotions in words and where are the words in emotions?

Theoretically, the answer to these questions is anything than trivial. Traditionally, language has been considered a purely cognitive function of the human mind; a property of the mind that evolved for the purpose of representing individual experiences in an abstract way, independent from sensory and motor experience and independent from bodily sensations including emotions (for a discussion see Chapter 1 in this book). In this view, reading emotion-related or emotional words such as “snake” or “fear” may activate the semantic meaning of the word including its emotional meaning; readers may even infer from reading that snakes are harmful and threatening creatures; nonetheless, this knowledge would be stored in a purely amodal fashion. As a result, readers would be unable to bodily and affectively feel what they are reading because the crucial link between mental states and sensory, motor and peripheral (bodily) changes characterizing emotions would be missing. In other words, viewed from a pure cognitive approach of language, emotions and their perceptual, sensory and motor consequences can be expressed linguistically. However, the linguistic description and semantic representation of an emotion will not be accompanied by physiological bodily changes or by affective experiences of arousal, or by bodily feelings of pleasure and displeasure nor by changes in motivational behavior of approach or avoidance.

In recent years there have been changes with respect to the understanding of mind-body interactions and the role language may play in emotion processing and emotion regulation. In the past 15 years, a number of studies have been conducted at the interface of language and emotion, most if not all of them accumulated empirical evidence against the theoretical belief of a purely cognitive-based foundation of language (e.g., see Chapter 1–4 in this book).

Emotional Word Processing—Core Dimensions, Time Course and Brain Structures

Several studies investigated the neurophysiological and psychophysiological correlates of emotional word processing to determine whether the processing of emotions from words and the processing of emotions from pictures or faces share the same neurophysiological mechanisms (e.g., Kissler et al., 2006, 2007; Herbert et al., 2008; Citron, 2012; Mavratzakis et al., 2016; see Bayer and Schacht; Palazova in this book for an overview). Methodologically, most studies used high-density electroencephalography (EEG) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) techniques either alone or in combination with behavioral and subjective self-report measures.

Investigating emotional word processing in the brain showed that reading emotional words vs. neutral words increases neural activity in the ventral visual processing stream (involved in object recognition) within the first 200 ms after word presentation; i.e., in the same early time-windows reported in EEG studies investigating emotional picture processing (e.g., Junghöfer et al., 2001; Kissler et al., 2007; Herbert et al., 2008; see Bayer and Schacht, in this book for an overview). For words, occasionally, even earlier emotional facilitation effects have been reported indicating that emotional content is able to circumvent in-depth semantic analysis (e.g., Kissler and Herbert, 2013; see Palazova in this book for discussion). Interestingly, results from imaging studies suggested that these stimulus-driven neural activity changes are likely to be caused by reentrant processing between the amygdala and the ventral visual processing system (e.g., Herbert et al., 2009; see Flaisch et al.; Eden et al. in this book for a discussion). Furthermore, under some instances, processing of emotional words may also lead to changes in approach and avoidance behavior (e.g., Herbert and Kissler, 2010) and to specific approach- and avoidance related behavioral response patterns (see Citron et al. for an overview in this book).

Taken together, the results do not support the idea that language representations in the brain are cut off from perception, actions and emotions. Instead the results argue in favor of a common coding principle of how the brain represents and processes emotional information—be this information abstract or concrete, verbal or non-verbal. Emotional stimuli may therefore—regardless of the stimulus type (pictures, faces or words)—elicit changes in central autonomic arousal and in specific appraisals related to pleasure and displeasure. Nevertheless, as suggested by functional imaging and EEG source analysis studies, the activation of brain structures involved in the top-down regulation of visual attention can significantly differ during processing of emotional pictures vs. emotional words; also when words are used as task-related distracters vs. targets (e.g., see Flaisch et al.; Hinojosa et al. in this book).

This raises questions about whether the emotional content of a word is embodied during reading: i.e., can readers affectively experience and feel what they are reading? And if so, when during reading does this kind of embodied processing occur? Undeniably, many if not all languages are rich of emotional words, suggesting a tight connection between written words and felt emotions. Previous research exploring the structure of affective ratings in large emotional word corpora and different languages suggested two dimensional emotional factors of valence (positive vs. negative) and arousal (being physiologically calm vs. aroused). These two factors seem to explain most of the variance of the affective ratings of words (e.g., see Jacobs et al. in this book for an overview). More recent studies found that other stimulus appraisal factors related to sensing, acting and feeling may also play a role (e.g., see Imbir et al.; Jacobs et al. in this book for an overview). All in all, this suggests on the one hand, fast and non-reflective appraisal of words according to the bodily arousal of the words and on the other hand, temporally slower and reflective evaluation of the word’s personal self-, motivational or emotional relevance.

The distinction between pre-reflective, arousal-driven vs. reflective and valence-driven appraisal checks is well in line with what EEG studies investigating the time course of emotional word processing during passive reading, lexical decision or rapid serial visual presentation suggested (Herbert et al., 2006, 2008; Kissler et al., 2007, 2009; Carretié et al., 2008; Schacht and Sommer, 2009; Hinojosa et al., 2010): a rapid and selective processing of highly arousing emotional words of positive and negative valence in the time window of, for instance, the early posterior negativity (EPN) and a temporally later in-depth semantic processing of emotional words according to their emotional valence (positive vs. negative) in, for instance, the time windows of the N400 and LPP (e.g., Herbert et al., 2006, 2008; Kissler et al., 2009; see Palazova; Bayer and Schacht, in this book for a discussion). Therefore, the emotional significance of a word may be quickly appraised according to its physiological arousal and its emotional intensity. However, at these early bottom-up driven stages of emotional word processing the subjective feelings that arise from this processing may at this stage of word processing not be consciously, conceptually and semantically available for the reader although they arise from verbal input (Herbert, 2015; see e.g., Lindquist; Ensie Abbassi et al. in this book for a theoretical discussion). Subjective feelings may be consciously, conceptually and semantically available for the reader only during later stages of word processing.

Effects of Mood, Intrapersonal and Sublexical Factors Including Comparisons Across Stimulus Types

Moreover, sublexical factors such as phonological iconicity (sound-to-meaning correspondences) and intrapersonal factors (e.g., subjective mood, anxiety) can influence emotional word processing (e.g., Eden et al.; Sereno et al.; Ullrich et al., in this book). Regarding sublexical factors, these factors may modulate already stimulus-driven early stages of emotional word processing (Ullrich et al. in this book). Furthermore, anxiety may modulate activity in emotion structures such as the amygdala (involved in emotion detection and emotional response selection) in associative word-learning paradigms (Eden et al. in this book), whereas positive mood may change lexical decisions for positive and negative words via a broadening of attention (Sereno et al. in this book). Also, the induced mood state (via positive or negative film clips) may significantly affect syntactic processing of words. Thus, the interaction between emotion and language can go beyond semantic processing levels (see Verhees et al. in this book).

Nevertheless, an early stimulus tagging stage seems obligatory for all types of emotional stimuli (faces, words, pictures). This is also suggested by studies that compared the time course of emotional picture, emotional face and emotional word processing. These studies suggest that pictures, faces and words do evoke the same electrophysiological signals (e.g., an early posterior negativity component, EPN, as well as a late positive potential, LPP), but the emotion effects elicited at later processing stages may be stimulus-type specific due to a positivity offset elicited by the overall lower arousal levels of words vs. faces and pictures (see Bayer and Schacht; Lüdtke and Jacobs in this book for a discussion of EEG and behavioral results).

Emotional Word Processing—Current Theories and Perspectives

What many emotional word processing studies though still leave open is whether the results summarized above are more compatible with traditional associative network models, interactive dual processing models or with an embodied account of word processing. Associative network models of emotions assume that emotional content conveyed by an abstract symbol such as a word or a concrete emotional stimulus such as a picture is rapidly mapped onto conceptual knowledge stored in associative memory networks. The information stored in these networks as nodes includes links to the operations, use, and purpose of the stimulus, as well as its emotional and physiological consequences (e.g., Lang, 1979; Bower, 1981). Importantly, activation of these networks is assumed to partially reactivate the perceptual processing, feeling- and action patterns that occur when directly confronted with an emotion inducing event in real time; an assumption that is also shared by theories of embodied cognition, that view knowledge as grounded in perception and action. Dual processing models (e.g., Paivio, 2010) as well as embodied theories of language processing (e.g., Barsalou et al., 2008) distinguish between two processing systems. Controversy between the two theories exists in the way concrete and abstract stimuli are processed by the two propagated systems (Vigliocco et al., 2009; Kousta et al., 2011; Paivio, 2013, for a discussion). Embodied theories propose a fast linguistic system and a temporally slower imagery-based simulation system (see Ensi-Abassi et al. in this book). Additionally, they assume that experiencing emotions through abstract words is possible only through simulation or reenactment. Theoretically, it has been proposed that on a cortical level, embodied processing of emotional words is laterized to the right hemisphere, whereas a pure linguistic and probably “cold” appraisal of words is more strongly associated with left-hemisphere activation (see Ensi-Abassi et al. Moritz-Gasser et al. in this book).

Going Beyond Single Words—the Impact of Self-Reference, Social Relevance and Communicative Context on Emotional Word and Sentence Processing

Compelling evidence that emotional content conveyed by abstract symbols such as words can elicit consciously retrievable affective feeling states comes from recent studies that extended emotion word processing to the domains of social cognition. Going beyond single words, a number of these studies use sentences that differ in self-reference (see Fields and Kuperberg, in this book). Other studies use compound stimuli consisting of pronoun- and article-noun pairs making a reference to the reader’s own emotions (e.g., “my fear,” “my pleasure”) or to the emotion of another person (“my fear,” “my pleasure”) or that contain no particular personal reference (see Weis and Herbert, in this book). Some studies are using more complex designs in which participants read emotional trait adjectives in anticipation of an evaluation by a significant communicative sender (see Schindler et al. in this book). Generally speaking, these studies allow a detailed analysis of where and when in the processing stream emotional meaning is discriminated from neutral meaning as a function of the communicative context and the stimuli’s personal or social reference (self, other, no reference). Crucially, one particular observation of these studies is that self-reference impacts emotional word processing during later stages of cortical processing, i.e., after an in-depth semantic analysis (N400, LPP) (see Fields and Kuperberg in this book; see also Herbert et al., 2011a,b). Moreover, the self-reference of an emotional word seems to selectively enhance activity in cortical midline structures, possibly generating an awareness, feeling or evaluation that this stimulus and its content refer to one’s own emotion (see Herbert et al., 2011c). Nevertheless, the evaluation of self-related emotional words in reference to one’s own feelings may not be accompanied by stronger emotional expressive behavior or by stronger physiological changes in heart rate or skin conductance: instead, it appears that appraising other-related emotional words (e.g., “his happiness”) in reference to one’s own feelings elicits significant changes in facial muscle activity (see Weis and Herbert, in this book).

Taken together, the results of the studies presented in Chapter 3 argue in favor of a differentiated view of embodied emotional word processing. The studies suggest that the social relevance of the emotional words needs to be taken into consideration. Interestingly, anticipating the evaluation by a communicative partner seems to be sufficient to increase the relevance of an emotional word. This seems to facilitate already early cortical processing in the EPN time window (see Schindler et al. in this book). Moreover, recent studies have extended emotional word processing to the domain of verbal fear learning and to symbolic generalization (see Bennet et al. in this book) and to grammatical aspects in political speech (see Havas and Chapp, in this book) and to the general affective meaning of a word in poetic texts (see Ullrich et al. in this book).

Where are the Words in Emotions? Affect Labeling, Emotional Language Acquisition, Multilingualisms and Poetic Aesthetics

Although the results reviewed above clearly support the notion that words can elicit emotions, yet, there is another line of research showing that language processing can also regulate and change emotion perception of non-verbal emotional signals (e.g., Lieberman et al., 2011; Herbert et al., 2013; see Lindquist et al. in this book for discussion). Viewed from a developmental perspective of the human brain, emotion processing may be significantly influenced by language as soon as children learn to use words and verbal labels for emotion expression and emotion categorization (see Lindquist et al. in this book). This implies that in the adult brain, language and emotions are inextricably intertwined, influencing each other on different levels of cerebral, peripheral, subjective and behavioral responding. Due to this bidirectional link between emotion and language, experimental approaches probing learning of new emotion concepts in adults in different languages as well as approaches investigating emotion processing in mono- vs. bilinguals or multilingual speakers seem to be especially fruitful to better understand this interaction (e.g., see Caldwell-Harris; Ferré et al. in this book).

Conclusion

As outlined above, the articles included in this book The Janus Face of Language: Where are the Emotions in Words and Where are the Words in Emotions? can provide a conclusive theoretical and empirical answer to the questions raised by the Topic Editors Herbert, Ethofer, Fallgatter, Walla, and Northoff. The authors of the in total 24 articles theoretically and empirically illuminate the key aspects of the relationship between language and emotion. They provide answers to how information about an emotion is decoded from abstract stimuli such as words, and how the emotional content of a word is processed in the brain. They furthermore highlight the role bodily physiological changes and self- and socially relevant contexts play in the processing and generation of emotional word meaning.

Summary and Structure of the Chapters

The articles are grouped into four chapters: Chapter 1 comprises articles with a strong theoretical focus. These articles discuss recent theoretical views that exist in explaining the emotion-language link with regard to written language. In addition, empirical research focusing on word corpora analyses is included in Chapter 1 investigating the major core affective dimensions underlying the appraisal of emotional words in different languages. Chapter 2 comprises several experimental studies investigating the brain structures and the time course of emotional word processing. These studies also lay special focus on the effects of task-, sublexical, and intrapersonal factors. Moreover, they shed light on the questions of how affective core dimensions (e.g., emotional valence, emotional arousal or affective origin) influence emotion word processing, the interaction between words and the direction of behavior (approach vs. withdrawal). The studies summarized in Chapter 3 extend emotional word processing to the domains of social cognition. They provide evidence that the interaction between words and emotions must also be seen in a broader context that takes intrapersonal (self-reference), social factors (sender-receiver characteristics) and the sender’s communicative intentions into consideration. Finally, the studies summarized in Chapter 4 extend the research on emotional word processing to the domains of aesthetics and poetic text, bi- and multilingualism, i.e., areas of psycholinguistic and psychological language research that have developed only recently.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Barsalou, L. W., Santos, A., Simmons, W. K., and Wilson, C. D. (2008). “Language and simulation in conceptual processing,” in Symbols, Embodiment, and Meaning, eds M. De Vega, A. M. Glenberg, and A. C. Graesser (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 245–283.

Google Scholar

Carretié, L., Hinojosa, J. A., Albert, J., López-Martín, S., de la Gándara, B. S., Igoa, J. M., et al. (2008). Modulation of ongoing cognitive processes by emotionally intense words. Psychophysiology 45, 188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00617.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Citron, F. M. (2012). Neural correlates of written emotion word processing: a review of recent electrophysiological and hemodynamic neuroimaging studies. 122, 211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.007

CrossRef Full Text

Herbert, C. (2015). Human emotion in the brain and the body: why language matters: comment on“ The quartet theory of human emotions: an integrative and neurofunctional model” by S. Koelsch et al. Phys. Life Rev. 13, 55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2015.04.011

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Ethofer, T., Anders, S., Junghofer, M., Wildgruber, D., Grodd, W., et al. (2009). Amygdala activation during reading of emotional adjectives–an advantage for pleasant content. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 4, 35–49. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn027

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Herbert, B. M., Ethofer, T., and Pauli, P. (2011a). His or mine? The time course of self-other discrimination in emotion processing. Soc. Neurosci. 6, 277–288. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.523543

CrossRef Full Text

Herbert, C., Herbert, B. M., and Pauli, P. (2011b). Emotional self-reference: brain structures involved in the processing of words describing one’s own emotions. Neuropsychologia 49, 2947–2956. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.06.026

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Junghofer, M., and Kissler, J. (2008). Event related potentials to emotional adjectives during reading. Psychophysiology 45, 487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00638.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., and Kissler, J. (2010). Motivational priming and processing interrupt: startle reflex modulation during shallow and deep processing of emotional words. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 76, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.02.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Kissler, J., Junghöfer, M., Peyk, P., and Rockstroh, B. (2006). Processing of emotional adjectives. Evidence from startle EMG and ERPs. Psychophysiology 43, 197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00385.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Pauli, P., and Herbert, B. M. (2011c). Self-reference modulates the processing of emotional stimuli in the absence of explicit self-referential appraisal instructions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 6, 653–661. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq082

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herbert, C., Sfärlea, A., and Blumenthal, T. (2013). Your emotion or mine. Labeling feelings alters emotional face perception—an ERP study on automatic and intentional affect labeling. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7:378. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00378

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hinojosa, J. A., Méndez-Bértolo, C., and Pozo, M. A. (2010). Looking at emotional words is not the same as reading emotional words. Behavioral and neural correlates. Psychophysiology 47, 748–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.00982.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Junghöfer, M., Bradley, M. M., Elbert, T. R., and Lang, P. J. (2001). Fleeting images: a new look at early emotion discrimination. Psychophysiology 38, 175–178. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.3820175

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kissler, J., Assadollahi, R., and Herbert, C. (2006). Emotional and semantic networks in visual word processing: insights from ERP studies. Prog. Brain Res. 156, 147–183. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56008-X

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kissler, J., and Herbert, C. (2013). Emotion, Etmnooi, or Emitoon?–Faster lexical access to emotional than to neutral words during reading. Biol. Psychol. 92, 464–479. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.09.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kissler, J., Herbert, C., Peyk, P., and Junghofer, M. (2007). Buzzwords: early cortical responses to emotional words during reading. Psychol. Sci. 18, 475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01924.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kissler, J., Herbert, C., Winkler, I., and Junghofer, M. (2009). Emotion and attention in visual word processing. An ERP study. Biol. Psychol. 80, 75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.03.004

CrossRef Full Text

Kousta, S.-T., Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D. P., Andrews, M., and Del Campo, E. (2011). The representation of abstract words. Why emotion matters. J. Exp. Psychol. 140, 14–34. doi: 10.1037/a0021446

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lieberman, M. D., Inagaki, T. K.;, Tabibnia, G., and Crockett, M. J. (2011). Subjective responses to emotional stimuli during labeling, reappraisal, and distraction. Emotion 11, 468–480. doi: 10.1037/a0023503

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mavratzakis, A., Herbert, C., and Walla, P. (2016). Emotional facial expressions evoke faster orienting responses, but weaker emotional responses at neural and behavioural levels compared to scenes: a simultaneous EEG and facial EMG study. Neuroimage 124, 931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.065

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vigliocco, G., Meteyard, L., Andrews, M., and Kousta, S. (2009). Toward a theory of semantic representation. Lang. Cogn. 1, 219–247. doi: 10.1515/LANGCOG.2009.011

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar