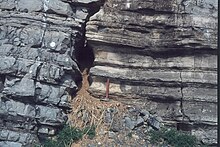

A natural arch produced by erosion of differentially weathered rock in Jebel Kharaz (Jordan)

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs in situ (on site, with little or no movement), and so is distinct from erosion, which involves the transport of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity.

Weathering processes are divided into physical and chemical weathering. Physical weathering involves the breakdown of rocks and soils through the mechanical effects of heat, water, ice, or other agents. Chemical weathering involves the chemical reaction of water, atmospheric gases, and biologically produced chemicals with rocks and soils. Water is the principal agent behind both physical and chemical weathering,[1] though atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide and the activities of biological organisms are also important.[2] Chemical weathering by biological action is also known as biological weathering.[3]

The materials left over after the rock breaks down combine with organic material to create soil. Many of Earth’s landforms and landscapes are the result of weathering processes combined with erosion and re-deposition. Weathering is a crucial part of the rock cycle, and sedimentary rock, formed from the weathering products of older rock, covers 66% of the Earth’s continents and much of its ocean floor.[4]

Physical weathering[edit]

Physical weathering, also called mechanical weathering or disaggregation, is the class of processes that causes the disintegration of rocks without chemical change.Physical weathering involves the breakdown of rocks into smaller fragments through processes such as expansion and contraction, mainly due to temperature changes. Two types of physical breakdown are freeze-thaw weathering and thermal fracturing. Pressure release can also cause weathering without temperature change. It is usually much less important than chemical weathering, but can be significant in subarctic or alpine environments.[5] Furthermore, chemical and physical weathering often go hand in hand. For example, cracks extended by physical weathering will increase the surface area exposed to chemical action, thus amplifying the rate of disintegration.[6]

Frost weathering is the most important form of physical weathering. Next in importance is wedging by plant roots, which sometimes enter cracks in rocks and pry them apart. The burrowing of worms or other animals may also help disintegrate rock, as can «plucking» by lichens.[7]

Frost weathering[edit]

A rock in Abisko, Sweden fractured along existing joints possibly by frost weathering or thermal stress

Frost weathering is the collective name for those forms of physical weathering that are caused by the formation of ice within rock outcrops. It was long believed that the most important of these is frost wedging, which results from the expansion of pore water when it freezes. However, a growing body of theoretical and experimental work suggests that ice segregation, in which supercooled water migrates to lenses of ice forming within the rock, is the more important mechanism.[8][9]

When water freezes, its volume increases by 9.2%. This expansion can theoretically generate pressures greater that 200 megapascals (29,000 psi), though a more realistic upper limit is 14 megapascals (2,000 psi). This is still much greater than the tensile strength of granite, which is about 4 megapascals (580 psi). This makes frost wedging, in which pore water freezes and its volumetric expansion fractures the enclosing rock, appear to be a plausible mechanism for frost weathering. However, ice will simply expand out of a straight, open fracture before it can generate significant pressure. Thus frost wedging can only take place in small, tortuous fractures.[5] The rock must also be almost completely saturated with water, or the ice will simply expand into the air spaces in the unsaturated rock without generating much pressure. These conditions are unusual enough that frost wedging is unlikely to be the dominant process of frost weathering.[10] Frost wedging is most effective where there are daily cycles of melting and freezing of water-saturated rock, so it is unlikely to be significant in the tropics, in polar regions or in arid climates.[5]

Ice segregation is a less well characterized mechanism of physical weathering.[8] It takes place because ice grains always have a surface layer, often just a few molecules thick, that resembles liquid water more than solid ice, even at temperatures well below the freezing point. This premelted liquid layer has unusual properties, including a strong tendency to draw in water by capillary action from warmer parts of the rock. This results in growth of the ice grain that puts considerable pressure on the surrounding rock,[11] up to ten times greater than is likely with frost wedging. This mechanism is most effective in rock whose temperature averages just below the freezing point, −4 to −15 °C (25 to 5 °F). Ice segregation results in growth of ice needles and ice lenses within fractures in the rock and parallel to the rock surface, that gradually pry the rock apart.[9]

Thermal stress[edit]

Thermal stress weathering results from the expansion and contraction of rock due to temperature changes. Thermal stress weathering is most effective when the heated portion of the rock is buttressed by surrounding rock, so that it is free to expand in only one direction.[12]

Thermal stress weathering comprises two main types, thermal shock and thermal fatigue. Thermal shock takes place when the stresses are so great that the rock cracks immediately, but this is uncommon. More typical is thermal fatigue, in which the stresses are not great enough to cause immediate rock failure, but repeated cycles of stress and release gradually weaken the rock.[12]

Thermal stress weathering is an important mechanism in deserts, where there is a large diurnal temperature range, hot in the day and cold at night.[13] As a result, thermal stress weathering is sometimes called insolation weathering, but this is misleading. Thermal stress weathering can be caused by any large change of temperature, and not just intense solar heating. It is likely as important in cold climates as in hot, arid climates.[12] Wildfires can also be a significant cause of rapid thermal stress weathering.[14]

The importance of thermal stress weathering has long been discounted by geologists,[5][9] based on experiments in the early 20th century that seemed to show that its effects were unimportant. These experiments have since been criticized as unrealistic, since the rock samples were small, were polished (which reduces nucleation of fractures), and were not buttressed. These small samples were thus able to expand freely in all directions when heated in experimental ovens, which failed to produce the kinds of stress likely in natural settings. The experiments were also more sensitive to thermal shock than thermal fatigue, but thermal fatigue is likely the more important mechanism in nature. Geomorphologists have begun to reemphasize the importance of thermal stress weathering, particularly in cold climates.[12]

Pressure release[edit]

Exfoliated granite sheets in Texas, possibly caused by pressure release

Pressure release or unloading is a form of physical weathering seen when deeply buried rock is exhumed. Intrusive igneous rocks, such as granite, are formed deep beneath the Earth’s surface. They are under tremendous pressure because of the overlying rock material. When erosion removes the overlying rock material, these intrusive rocks are exposed and the pressure on them is released. The outer parts of the rocks then tend to expand. The expansion sets up stresses which cause fractures parallel to the rock surface to form. Over time, sheets of rock break away from the exposed rocks along the fractures, a process known as exfoliation. Exfoliation due to pressure release is also known as sheeting.[15]

As with thermal weathering, pressure release is most effective in buttressed rock. Here the differential stress directed towards the unbuttressed surface can be as high as 35 megapascals (5,100 psi), easily enough to shatter rock. This mechanism is also responsible for spalling in mines and quarries, and for the formation of joints in rock outcrops.[16]

Retreat of an overlying glacier can also lead to exfoliation due to pressure release. This can be enhanced by other physical wearing mechanisms.[17]

Salt-crystal growth [edit]

Salt crystallization (also known as salt weathering, salt wedging or haloclasty) causes disintegration of rocks when saline solutions seep into cracks and joints in the rocks and evaporate, leaving salt crystals behind. As with ice segregation, the surfaces of the salt grains draw in additional dissolved salts through capillary action, causing the growth of salt lenses that exert high pressure on the surrounding rock. Sodium and magnesium salts are the most effective at producing salt weathering. Salt weathering can also take place when pyrite in sedimentary rock is chemically weathered to iron(II) sulfate and gypsum, which then crystallize as salt lenses.[9]

Salt crystallization can take place wherever salts are concentrated by evaporation. It is thus most common in arid climates where strong heating causes strong evaporation and along coasts.[9] Salt weathering is likely important in the formation of tafoni, a class of cavernous rock weathering structures.[18]

Biological effects on mechanical weathering[edit]

Living organisms may contribute to mechanical weathering, as well as chemical weathering (see § Biological weathering below). Lichens and mosses grow on essentially bare rock surfaces and create a more humid chemical microenvironment. The attachment of these organisms to the rock surface enhances physical as well as chemical breakdown of the surface microlayer of the rock. Lichens have been observed to pry mineral grains loose from bare shale with their hyphae (rootlike attachment structures), a process described as plucking, [15] and to pull the fragments into their body, where the fragments then undergo a process of chemical weathering not unlike digestion.[19] On a larger scale, seedlings sprouting in a crevice and plant roots exert physical pressure as well as providing a pathway for water and chemical infiltration.[7]

Chemical weathering[edit]

Comparison of unweathered (left) and weathered (right) limestone

Most rock forms at elevated temperature and pressure, and the minerals making up the rock are often chemically unstable in the relatively cool, wet, and oxidizing conditions typical of the Earth’s surface. Chemical weathering takes place when water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and other chemical substances react with rock to change its composition. These reactions convert some of the original primary minerals in the rock to secondary minerals, remove other substances as solutes, and leave the most stable minerals as a chemically unchanged resistate. In effect, chemical weathering changes the original set of minerals in the rock into a new set of minerals that is in closer equilibrium with surface conditions. However, true equilibrium is rarely reached, because weathering is a slow process, and leaching carries away solutes produced by weathering reactions before they can accumulate to equilibrium levels. This is particularly true in tropical environments.[20]

Water is the principal agent of chemical weathering, converting many primary minerals to clay minerals or hydrated oxides via reactions collectively described as hydrolysis. Oxygen is also important, acting to oxidize many minerals, as is carbon dioxide, whose weathering reactions are described as carbonation.[21]

The process of mountain block uplift is important in exposing new rock strata to the atmosphere and moisture, enabling important chemical weathering to occur; significant release occurs of Ca2+ and other ions into surface waters.[22]

Dissolution[edit]

Limestone core samples at different stages of chemical weathering, from very high at shallow depths (bottom) to very low at greater depths (top). Slightly weathered limestone shows brownish stains, while highly weathered limestone loses much of its carbonate mineral content, leaving behind clay. Limestone drill core taken from the carbonate West Congolian deposit in Kimpese, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dissolution (also called simple solution or congruent dissolution) is the process in which a mineral dissolves completely without producing any new solid substance.[23] Rainwater easily dissolves soluble minerals, such as halite or gypsum, but can also dissolve highly resistant minerals such as quartz, given sufficient time.[24] Water breaks the bonds between atoms in the crystal:[25]

The overall reaction for dissolution of quartz is

- SiO2 + 2H2O → H4SiO4

The dissolved quartz takes the form of silicic acid.

A particularly important form of dissolution is carbonate dissolution, in which atmospheric carbon dioxide enhances solution weathering. Carbonate dissolution affects rocks containing calcium carbonate, such as limestone and chalk. It takes place when rainwater combines with carbon dioxide to form carbonic acid, a weak acid, which dissolves calcium carbonate (limestone) and forms soluble calcium bicarbonate. Despite a slower reaction kinetics, this process is thermodynamically favored at low temperature, because colder water holds more dissolved carbon dioxide gas (due to the retrograde solubility of gases). Carbonate dissolution is therefore an important feature of glacial weathering.[26]

Carbonate dissolution involves the following steps:

- CO2 + H2O → H2CO3

- carbon dioxide + water → carbonic acid

- H2CO3 + CaCO3 → Ca(HCO3)2

- carbonic acid + calcium carbonate → calcium bicarbonate

Carbonate dissolution on the surface of well-jointed limestone produces a dissected limestone pavement. This process is most effective along the joints, widening and deepening them.[27]

In unpolluted environments, the pH of rainwater due to dissolved carbon dioxide is around 5.6. Acid rain occurs when gases such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides are present in the atmosphere. These oxides react in the rain water to produce stronger acids and can lower the pH to 4.5 or even 3.0. Sulfur dioxide, SO2, comes from volcanic eruptions or from fossil fuels, can become sulfuric acid within rainwater, which can cause solution weathering to the rocks on which it falls.[28]

Hydrolysis and carbonation[edit]

Hydrolysis (also called incongruent dissolution) is a form of chemical weathering in which only part of a mineral is taken into solution. The rest of the mineral is transformed into a new solid material, such as a clay mineral.[29] For example, forsterite (magnesium olivine) is hydrolyzed into solid brucite and dissolved silicic acid:

- Mg2SiO4 + 4 H2O ⇌ 2 Mg(OH)2 + H4SiO4

- forsterite + water ⇌ brucite + silicic acid

Most hydrolysis during weathering of minerals is acid hydrolysis, in which protons (hydrogen ions), which are present in acidic water, attack chemical bonds in mineral crystals.[30] The bonds between different cations and oxygen ions in minerals differ in strength, and the weakest will be attacked first. The result is that minerals in igneous rock weather in roughly the same order in which they were originally formed (Bowen’s Reaction Series).[31] Relative bond strength is shown in the following table:[25]

| Bond | Relative strength |

|---|---|

| Si–O | 2.4 |

| Ti–O | 1.8 |

| Al–O | 1.65 |

| Fe+3–O | 1.4 |

| Mg–O | 0.9 |

| Fe+2–O | 0.85 |

| Mn–O | 0.8 |

| Ca–O | 0.7 |

| Na–O | 0.35 |

| K–O | 0.25 |

This table is only a rough guide to order of weathering. Some minerals, such as illite, are unusually stable, while silica is unusually unstable given the strength of the silicon-oxygen bond.[32]

Carbon dioxide that dissolves in water to form carbonic acid is the most important source of protons, but organic acids are also important natural sources of acidity.[33] Acid hydrolysis from dissolved carbon dioxide is sometimes described as carbonation, and can result in weathering of the primary minerals to secondary carbonate minerals.[34] For example, weathering of forsterite can produce magnesite instead of brucite via the reaction:

- Mg2SiO4 + 2 CO2 + 2 H2O ⇌ 2 MgCO3 + H4SiO4

- forsterite + carbon dioxide + water ⇌ magnesite + silicic acid in solution

Carbonic acid is consumed by silicate weathering, resulting in more alkaline solutions because of the bicarbonate. This is an important reaction in controlling the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and can affect climate.[35]

Aluminosilicates containing highly soluble cations, such as sodium or potassium ions, will release the cations as dissolved bicarbonates during acid hydrolysis:

- 2 KAlSi3O8 + 2 H2CO3 + 9 H2O ⇌ Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 4 H4SiO4 + 2 K+ + 2 HCO3−

- orthoclase (aluminosilicate feldspar) + carbonic acid + water ⇌ kaolinite (a clay mineral) + silicic acid in solution + potassium and bicarbonate ions in solution

Oxidation[edit]

A pyrite cube has dissolved away from host rock, leaving gold particles behind.

Within the weathering environment, chemical oxidation of a variety of metals occurs. The most commonly observed is the oxidation of Fe2+ (iron) by oxygen and water to form Fe3+ oxides and hydroxides such as goethite, limonite, and hematite. This gives the affected rocks a reddish-brown coloration on the surface which crumbles easily and weakens the rock. Many other metallic ores and minerals oxidize and hydrate to produce colored deposits, as does sulfur during the weathering of sulfide minerals such as chalcopyrites or CuFeS2 oxidizing to copper hydroxide and iron oxides.[36]

Hydration[edit]

Mineral hydration is a form of chemical weathering that involves the rigid attachment of water molecules or H+ and OH- ions to the atoms and molecules of a mineral. No significant dissolution takes place. For example, iron oxides are converted to iron hydroxides and the hydration of anhydrite forms gypsum.[37]

Bulk hydration of minerals is secondary in importance to dissolution, hydrolysis, and oxidation,[36] but hydration of the crystal surface is the crucial first step in hydrolysis. A fresh surface of a mineral crystal exposes ions whose electrical charge attracts water molecules. Some of these molecules break into H+ that bonds to exposed anions (usually oxygen) and OH- that bonds to exposed cations. This further disrupts the surface, making it susceptible to various hydrolysis reactions. Additional protons replace cations exposed in the surface, freeing the cations as solutes. As cations are removed, silicon-oxygen and silicon-aluminium bonds become more susceptible to hydrolysis, freeing silicic acid and aluminium hydroxides to be leached away or to form clay minerals.[32][38] Laboratory experiments show that weathering of feldspar crystals begins at dislocations or other defects on the surface of the crystal, and that the weathering layer is only a few atoms thick. Diffusion within the mineral grain does not appear to be significant.[39]

Biological weathering[edit]

Mineral weathering can also be initiated or accelerated by soil microorganisms. Soil organisms make up about 10 mg/cm3 of typical soils, and laboratory experiments have demonstrated that albite and muscovite weather twice as fast in live versus sterile soil. Lichens on rocks are among the most effective biological agents of chemical weathering.[33] For example, an experimental study on hornblende granite in New Jersey, USA, demonstrated a 3x – 4x increase in weathering rate under lichen covered surfaces compared to recently exposed bare rock surfaces.[40]

The most common forms of biological weathering result from the release of chelating compounds (such as certain organic acids and siderophores) and of carbon dioxide and organic acids by plants. Roots can build up the carbon dioxide level to 30% of all soil gases, aided by adsorption of CO2 on clay minerals and the very slow diffusion rate of CO2 out of the soil.[41] The CO2 and organic acids help break down aluminium- and iron-containing compounds in the soils beneath them. Roots have a negative electrical charge balanced by protons in the soil next to the roots, and these can be exchanged for essential nutrient cations such as potassium.[42] Decaying remains of dead plants in soil may form organic acids which, when dissolved in water, cause chemical weathering.[43] Chelating compounds, mostly low molecular weight organic acids, are capable of removing metal ions from bare rock surfaces, with aluminium and silicon being particularly susceptible.[44] The ability to break down bare rock allows lichens to be among the first colonizers of dry land.[45] The accumulation of chelating compounds can easily affect surrounding rocks and soils, and may lead to podsolisation of soils.[46][47]

The symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi associated with tree root systems can release inorganic nutrients from minerals such as apatite or biotite and transfer these nutrients to the trees, thus contributing to tree nutrition.[48] It was also recently evidenced that bacterial communities can impact mineral stability leading to the release of inorganic nutrients.[49] A large range of bacterial strains or communities from diverse genera have been reported to be able to colonize mineral surfaces or to weather minerals, and for some of them a plant growth promoting effect has been demonstrated.[50] The demonstrated or hypothesised mechanisms used by bacteria to weather minerals include several oxidoreduction and dissolution reactions as well as the production of weathering agents, such as protons, organic acids and chelating molecules.

Weathering on the ocean floor[edit]

Weathering of basaltic oceanic crust differs in important respects from weathering in the atmosphere. Weathering is relatively slow, with basalt becoming less dense, at a rate of about 15% per 100 million years. The basalt becomes hydrated, and is enriched in total and ferric iron, magnesium, and sodium at the expense of silica, titanium, aluminum, ferrous iron, and calcium.[51]

Building weathering[edit]

Buildings made of any stone, brick or concrete are susceptible to the same weathering agents as any exposed rock surface. Also statues, monuments and ornamental stonework can be badly damaged by natural weathering processes. This is accelerated in areas severely affected by acid rain.[52]

Accelerated building weathering may be a threat to the environment and occupant safety. Design strategies can moderate the impact of environmental effects, such as using of pressure-moderated rain screening, ensuring that the HVAC system is able to effectively control humidity accumulation and selecting concrete mixes with reduced water content to minimize the impact of freeze-thaw cycles. [53]

Properties of well-weathered soils[edit]

Granitic rock, which is the most abundant crystalline rock exposed at the Earth’s surface, begins weathering with destruction of hornblende. Biotite then weathers to vermiculite, and finally oligoclase and microcline are destroyed. All are converted into a mixture of clay minerals and iron oxides.[31] The resulting soil is depleted in calcium, sodium, and ferrous iron compared with the bedrock, and magnesium is reduced 40% and silicon by 15%. At the same time, the soil is enriched in aluminium and potassium, by at least 50%; by titanium, whose abundance triples; and by ferric iron, whose abundance increases by an order of magnitude compared with the bedrock.[54]

Basaltic rock is more easily weathered than granitic rock, due to its formation at higher temperatures and drier conditions. The fine grain size and presence of volcanic glass also hasten weathering. In tropical settings, it rapidly weathers to clay minerals, aluminium hydroxides, and titanium-enriched iron oxides. Because most basalt is relatively poor in potassium, the basalt weathers directly to potassium-poor montmorillonite, then to kaolinite. Where leaching is continuous and intense, as in rain forests, the final weathering product is bauxite, the principal ore of aluminium. Where rainfall is intense but seasonal, as in monsoon climates, the final weathering product is iron- and titanium-rich laterite. [55] Conversion of kaolinite to bauxite occurs only with intense leaching, as ordinary river water is in equilibrium with kaolinite.[56]

Soil formation requires between 100 and 1,000 years, a very brief interval in geologic time. As a result, some formations show numerous paleosol (fossil soil) beds. For example, the Willwood Formation of Wyoming contains over 1,000 paleosol layers in a 770 meters (2,530 ft) section representing 3.5 million years of geologic time. Paleosols have been identified in formations as old as Archean (over 2.5 billion years in age). However, paleosols are difficult to recognize in the geologic record.[57] Indications that a sedimentary bed is a paleosol include a gradational lower boundary and sharp upper boundary, the presence of much clay, poor sorting with few sedimentary structures, rip-up clasts in overlying beds, and desiccation cracks containing material from higher beds.[58]

The degree of weathering of a soil can be expressed as the chemical index of alteration, defined as 100 Al2O3/(Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O + K2O). This varies from 47 for unweathered upper crust rock to 100 for fully weathered material.[59]

Weathering of non-geological materials[edit]

Wood can be physically and chemically weathered by hydrolysis and other processes relevant to minerals, but in addition, wood is highly susceptible to weathering induced by ultraviolet radiation from sunlight. This induces photochemical reactions that degrade the wood surface.[60] Photochemical reactions are also significant in the weathering of paint[61] and plastics.[62]

Gallery[edit]

-

Salt weathering of building stone on the island of Gozo, Malta

-

Weathering on a sandstone pillar in Bayreuth

-

Weathering effect on a sandstone statue in Dresden, Germany

-

Physical weathering of the pavements of Azad University Science and Research Branch, which is located in the heights of Tehran, the capital of Iran

See also[edit]

- Aeolian processes – Processes due to wind activity

- Biorhexistasy – Theory explaining the formation of soils and transported sediments by changes of climatic conditions

- Case hardening of rocks

- Decomposition – Process in which organic substances are broken down into simpler organic matter

- Environmental chamber

- Eluvium – End product of rock weathering

- Exfoliating granite – Granite skin peeling like an onion (desquamation) because of weathering

- Factors of polymer weathering – Photo-oxidation of polymers

- Metasomatism – Chemical alteration of a rock by hydrothermal and other fluids

- Meteorite weathering – Terrestrial alteration of a meteorite

- Pedogenesis – Process of soil formation

- Reverse weathering

- Soil production function

- Space weathering – Type of weathering

- Spheroidal weathering – Form of chemical weathering that affects jointed bedrock

- Weather testing of polymers – Controlled polymer and polymer coating degradation

- Weathering steel – Group of steel alloys designed to form a rust-like finish when exposed to weather

References[edit]

- ^ Leeder, M. R. (2011). Sedimentology and sedimentary basins : from turbulence to tectonics (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 4. ISBN 9781405177832.

- ^ Blatt, Harvey; Middleton, Gerard; Murray, Raymond (1980). Origin of sedimentary rocks (2d ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0136427103.

- ^ Gore, Pamela J. W. «Weathering». Georgia Perimeter College. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10.

- ^ Blatt, Harvey; Tracy, Robert J. (1996). Petrology : igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. p. 217. ISBN 0716724383.

- ^ a b c d Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 247.

- ^ Leeder 2011, p. 3.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Murton, J. B.; Peterson, R.; Ozouf, J.-C. (17 November 2006). «Bedrock Fracture by Ice Segregation in Cold Regions». Science. 314 (5802): 1127–1129. Bibcode:2006Sci…314.1127M. doi:10.1126/science.1132127. PMID 17110573. S2CID 37639112.

- ^ a b c d e Leeder 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Matsuoka, Norikazu; Murton, Julian (April 2008). «Frost weathering: recent advances and future directions». Permafrost and Periglacial Processes. 19 (2): 195–210. doi:10.1002/ppp.620. S2CID 131395533.

- ^ Dash, J. G.; Rempel, A. W.; Wettlaufer, J. S. (12 July 2006). «The physics of premelted ice and its geophysical consequences». Reviews of Modern Physics. 78 (3): 695–741. Bibcode:2006RvMP…78..695D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.695.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Kevin (1999), «The role of thermal stress fatigue in the breakdown of rock in cold regions», Geomorphology, 31 (1–4): 47–63, Bibcode:1999Geomo..31…47H, doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(99)00072-0

- ^ Paradise, T. R. (2005). «Petra revisited: An examination of sandstone weathering research in Petra, Jordan». Special Paper 390: Stone Decay in the Architectural Environment. Vol. 390. pp. 39–49. doi:10.1130/0-8137-2390-6.39. ISBN 0-8137-2390-6.

- ^ Shtober-Zisu, Nurit; Wittenberg, Lea (March 2021). «Long-term effects of wildfire on rock weathering and soil stoniness in the Mediterranean landscapes». Science of the Total Environment. 762: 143125. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.762n3125S. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143125. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 33172645. S2CID 225117000.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 249.

- ^ Leeder 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Harland, W. B. (1957). «Exfoliation Joints and Ice Action». Journal of Glaciology. 3 (21): 8–10. doi:10.3189/S002214300002462X.

- ^ Turkington, Alice V.; Paradise, Thomas R. (April 2005). «Sandstone weathering: a century of research and innovation». Geomorphology. 67 (1–2): 229–253. Bibcode:2005Geomo..67..229T. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.09.028.

- ^ Fry, E. Jennie (July 1927). «The Mechanical Action of Crustaceous Lichens on Substrata of Shale, Schist, Gneiss, Limestone, and Obsidian». Annals of Botany. os-41 (3): 437–460. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a090084.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 246.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2010) «Calcium», in A. Jorgenson and C. Cleveland (eds.) Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

- ^ Birkeland, Peter W. (1999). Soils and geomorphology (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0195078862.

- ^ Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 7. ISBN 0131547283.

- ^ a b Nicholls, G. D. (1963). «Environmental Studies in Sedimentary Geochemistry». Science Progress (1933- ). 51 (201): 12–31. JSTOR 43418626.

- ^ Plan, Lukas (June 2005). «Factors controlling carbonate dissolution rates quantified in a field test in the Austrian alps». Geomorphology. 68 (3–4): 201–212. Bibcode:2005Geomo..68..201P. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.11.014.

- ^ Anon. «Geology and geomorphology». Limestone Pavement Conservation. UK and Ireland Biodiversity Action Plan Steering Group. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Charlson, R. J.; Rodhe, H. (February 1982). «Factors controlling the acidity of natural rainwater». Nature. 295 (5851): 683–685. Bibcode:1982Natur.295..683C. doi:10.1038/295683a0. S2CID 4368102.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Leeder 2011, p. 4.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 252.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 258.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 250.

- ^ Thornbury, William D. (1969). Principles of geomorphology (2d ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 303–344. ISBN 0471861979.

- ^ Berner, Robert A. (31 December 1995). White, Arthur F; Brantley, Susan L (eds.). «Chapter 13. CHEMICAL WEATHERING AND ITS EFFECT ON ATMOSPHERIC CO2 AND CLIMATE». Chemical Weathering Rates of Silicate Minerals: 565–584. doi:10.1515/9781501509650-015. ISBN 9781501509650.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Boggs 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Leeder 2011, pp. 653–655.

- ^ Berner, Robert A.; Holdren, George R. (1 June 1977). «Mechanism of feldspar weathering: Some observational evidence». Geology. 5 (6): 369–372. Bibcode:1977Geo…..5..369B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1977)5<369:MOFWSO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Zambell, C.B.; Adams, J.M.; Gorring, M.L.; Schwartzman, D.W. (2012). «Effect of lichen colonization on chemical weathering of hornblende granite as estimated by aqueous elemental flux». Chemical Geology. 291: 166–174. Bibcode:2012ChGeo.291..166Z. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.10.009.

- ^ Fripiat, J. J. (1974). «Interlamellar Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide by Smectites». Clays and Clay Minerals. 22 (1): 23–30. Bibcode:1974CCM….22…23F. doi:10.1346/CCMN.1974.0220105. S2CID 53610319.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 251.

- ^ Chapin III, F. Stuart; Pamela A. Matson; Harold A. Mooney (2002). Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology ([Nachdr.] ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780387954431.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 233.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Lundström, U. S.; van Breemen, N.; Bain, D. C.; van Hees, P. A. W.; Giesler, R.; Gustafsson, J. P.; Ilvesniemi, H.; Karltun, E.; Melkerud, P. -A.; Olsson, M.; Riise, G. (2000-02-01). «Advances in understanding the podzolization process resulting from a multidisciplinary study of three coniferous forest soils in the Nordic Countries». Geoderma. 94 (2): 335–353. Bibcode:2000Geode..94..335L. doi:10.1016/S0016-7061(99)00077-4. ISSN 0016-7061.

- ^ Waugh, David (2000). Geography : an integrated approach (3rd ed.). Gloucester, U.K.: Nelson Thornes. p. 272. ISBN 9780174447061.

- ^ Landeweert, R.; Hoffland, E.; Finlay, R.D.; Kuyper, T.W.; van Breemen, N. (2001). «Linking plants to rocks: Ectomycorrhizal fungi mobilize nutrients from minerals». Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 16 (5): 248–254. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02122-X. PMID 11301154.

- ^ Calvaruso, C.; Turpault, M.-P.; Frey-Klett, P. (2006). «Root-Associated Bacteria Contribute to Mineral Weathering and to Mineral Nutrition in Trees: A Budgeting Analysis». Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (2): 1258–66. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.1258C. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.2.1258-1266.2006. PMC 1392890. PMID 16461674.

- ^ Uroz, S.; Calvaruso, C.; Turpault, M.-P.; Frey-Klett, P. (2009). «Mineral weathering by bacteria: ecology, actors and mechanisms». Trends Microbiol. 17 (8): 378–87. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.004. PMID 19660952.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1960, p. 256.

- ^ Schaffer, R. J. (2016). Weathering of Natural Building Stones. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781317742524.

- ^ «Design Discussion Primer — Chronic Stressors» (PDF). BC Housing. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray, p. 253.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray, p. 254.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray, p. 262.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray, p. 233.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 236.

- ^ Leeder, 2011 & 11.

- ^ Williams, R.S. (2005). «7». In Rowell, Roger M. (ed.). Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. pp. 139–185. ISBN 9780203492437.

- ^ Nichols, M.E.; Gerlock, J.L.; Smith, C.A.; Darr, C.A. (August 1999). «The effects of weathering on the mechanical performance of automotive paint systems». Progress in Organic Coatings. 35 (1–4): 153–159. doi:10.1016/S0300-9440(98)00060-5.

- ^ Weathering of plastics : testing to mirror real life performance. [Brookfield, Conn.]: Society of Plastics Engineers. 1999. ISBN 9781884207754.

Other links[edit]

Look up weathering in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Weathering.

Wikiversity has learning resources about Weathering

Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Justyn Murazik

Score: 4.6/5

(37 votes)

Weathering is the breaking down of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms.

What is the best definition of weathering?

Weathering describes the breaking down or dissolving of rocks and minerals on the surface of the Earth. Water, ice, acids, salts, plants, animals, and changes in temperature are all agents of weathering.

What are the 3 types of weathering?

Weathering is the breakdown of rocks at the Earth’s surface, by the action of rainwater, extremes of temperature, and biological activity. It does not involve the removal of rock material. There are three types of weathering, physical, chemical and biological.

What are the 4 types of weathering?

There are four main types of weathering. These are freeze-thaw, onion skin (exfoliation), chemical and biological weathering. Most rocks are very hard. However, a very small amount of water can cause them to break.

What do you mean by weathering Class 7?

Weathering, either chemical or physical, causes large rocks to break into smaller pieces, particularly near the surface. The smaller rocks weather into a fine layer of particles at the surface.

45 related questions found

What are examples of weathering?

Weathering is the wearing away of the surface of rock, soil, and minerals into smaller pieces. Example of weathering: Wind and water cause small pieces of rock to break off at the side of a mountain.

What is weathering Class 8 very short answer?

What is weathering? Answer. Weathering refers to the breaking up and decay of exposed rocks. This breaking up and decay are caused by temperature fluctuations between too high and too low, frost action, plants, animals, and even human activity.

What are 3 examples of physical weathering?

These examples illustrate physical weathering:

- Swiftly moving water. Rapidly moving water can lift, for short periods of time, rocks from the stream bottom. …

- Ice wedging. Ice wedging causes many rocks to break. …

- Plant roots. Plant roots can grow in cracks.

What is the best example of physical weathering?

The correct answer is (a) the cracking of rock caused by the freezing and thawing of water.

What are 5 types of weathering?

5 Types of Mechanical Weathering

- Plant Activity. The roots of plants are very strong and can grow into the cracks in existing rocks. …

- Animal Activity. …

- Thermal Expansion. …

- Frost action. …

- Exfoliaton.

What is an example of physical weathering?

Physical Weathering Caused by Water

When you pick up a rock out of a creek or stream, you are seeing an example of physical weathering, which is also referred to as mechanical weathering. … When the rocks drop back down they bump into other rocks, and tiny pieces of the rocks can break apart.

What is the biggest cause of weathering and erosion?

Plant and animal life, atmosphere and water are the major causes of weathering. Weathering breaks down and loosens the surface minerals of rock so they can be transported away by agents of erosion such as water, wind and ice.

Why is it called onion skin weathering?

spheroids of weathered rocks in which the successive shells of decayed rock resemble the layers of an onion. Also called onion weathering, concentric weathering.

What is weathering one word answer?

: the action of the weather conditions in altering the color, texture, composition, or form of exposed objects specifically : the physical disintegration and chemical decomposition of earth materials at or near the earth’s surface.

What is Brainpop weathering?

What is weathering? A process that break rocks down into smaller pieces.

How are you weathering meaning?

Weathering is defined as coping with the effects of changes in climate, environmental conditions or difficult situations. … When you make it through a difficult time, this is an example of a time when you might be said to be weathering the storm.

Is the best example of chemical weathering?

Some examples of chemical weathering are rust, which happens through oxidation and acid rain, caused from carbonic acid dissolves rocks. Other chemical weathering, such as dissolution, causes rocks and minerals to break down to form soil.

What are some examples of physical and chemical weathering?

Physical, or mechanical, weathering happens when rock is broken through the force of another substance on the rock such as ice, running water, wind, rapid heating/cooling, or plant growth. Chemical weathering occurs when reactions between rock and another substance dissolve the rock, causing parts of it to fall away.

What is the best example of physical weathering quizlet?

2. Which is the best example of physical weathering? (1) The cracking of rock caused by the freezing and thawing of water.

What are the 6 types of physical weathering?

There are six types of physical weathering:

- Exfoliation: also called unloading; the outer layers of rock break away from the rest of the rock due to heat expansion.

- Abrasion: moving material causes rock to break into smaller rock.

- Thermal expansion: outside layers of rock become hot, expand, and crack.

What are the factors of physical weathering?

Physical weathering can occur due to temperature, pressure, frost, root action, and burrowing animals. For example, cracks exploited by physical weathering will increase the surface area exposed to chemical action, thus amplifying the rate of disintegration.

What is meant by weathering class 9?

Weathering is the process of breaking down of rocks but not its removal. It is described as disintegration or decomposition of a rock in size by natural agents at or near the surface of the earth.

What is 11th weathering?

Weathering is mechanical disintegration and chemical decomposition of rocks through the actions of various elements of weather and climate. Weathering is an important process in the formation of soils. When rocks undergo weathering, rocks start to break up and take form of soil gradually.

What is the work of a river?

Hint: A river has three basic functions: erosion, transportation and deposition. It is the combination of these three processes that lead to the formation of various landforms by the action of a river. … Sometimes, the river overflows the banks causing flood in the neighboring areas.

Is weathering good or bad?

Weathering is a combination of mechanical breakdown of rocks into fragments and the chemical alteration of rock minerals. Erosion by wind, water or ice transports the weathering products to other locations where they eventually deposit. These are natural processes that are only harmful when they involve human activity.

The Definition of Weathering

Types of Weathering and Their Results

Weathering shapes this limestone landscape.

Premium/UIG/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Updated on October 01, 2018

Weathering is the gradual destruction of rock under surface conditions, dissolving it, wearing it away or breaking it down into progressively smaller pieces. Think of the Grand Canyon or the red rock formations scattered across the American Southwest. It may involve physical processes, called mechanical weathering, or chemical activity, called chemical weathering. Some geologists also include the actions of living things, or organic weathering. These organic weathering forces can be classified as mechanical or chemical or a combination of both.

Mechanical Weathering

Mechanical weathering involves five major processes that physically break rocks down into sediment or particles: abrasion, crystallization of ice, thermal fracture, hydration shattering, and exfoliation. Abrasion occurs from grinding against other rock particles. Crystallization of ice can result in force sufficient enough to fracture rock. Thermal fracture may occur due to significant temperature changes. Hydration — the effect of water — predominantly affects clay minerals. Exfoliation occurs when rock is unearthed after its formation.

Mechanical weathering does not just affect the earth. It can also affect some brick and stone buildings over time.

Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering involves the decomposition or decay of rock. This type of weathering doesn’t break rocks down but rather alters its chemical composition through carbonation, hydration, oxidation or hydrolysis. Chemical weathering changes the composition of the rock toward surface minerals and mostly affects minerals that were unstable in the first place. For example, water can eventually dissolve limestone. Chemical weathering can occur in sedimentary and metamorphic rocks and it is an element of chemical erosion.

Organic Weathering

Organic weathering is sometimes called bioweathering or biological weathering. It involves factors such as contact with animals—when they dig in the dirt—and plants when their growing roots contact rock. Plant acids can also contribute to the dissolution of rock.

Organic weathering isn’t a process that stands alone. It’s a combination of mechanical weathering factors and chemical weathering factors.

The Result of Weathering

Weathering can range from a change in color all the way to a complete breakdown of minerals into clay and other surface minerals. It creates deposits of altered and loosened material called residue that is ready to undergo transportation, moving across the earth’s surface when propelled by water, wind, ice or gravity and thus becoming eroded. Erosion means weathering plus transportation at the same time. Weathering is necessary for erosion, but a rock may weather without undergoing erosion.

: the action of the weather conditions in altering the color, texture, composition, or form of exposed objects

specifically

: the physical disintegration and chemical decomposition of earth materials at or near the earth’s surface

Example Sentences

Recent Examples on the Web

According to Thomlinson, the durability of landscape fabric depends on several factors, such as the type of material used and how often it is exposed to weathering.

—

In the permanently frozen soil bones and mammoth tusks are safe from weathering and scavengers, but mummified remains with skin and hair are rarely unearthed.

—

Consequently, scientists have disagreed about how sensitive weathering is to temperature changes on a global scale.

—

The steel bowl is designed to fade from a standard metallic color to a rusted one when exposed to weathering.

—

The Late Miocene Cooling Event, previously attributed to carbon dioxide drawdown from Himalayan silicate weathering, may have been caused in large part by ash from Andean volcanism.

—

There is now a broader understanding and acceptance that these technologies, which actively suck carbon out of the atmosphere through direct air capture, enhanced weathering, and other methods, are critical to reaching our global climate goals.

—

Buildings that show a little weathering just look old to a lot of people.

—

This process, called weathering, breaks down billions of tons of minerals across the Earth’s surface each year.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘weathering.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

First Known Use

1548, in the meaning defined above

Time Traveler

The first known use of weathering was

in 1548

Dictionary Entries Near weathering

Cite this Entry

“Weathering.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/weathering. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on weathering

Last Updated:

9 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Meaning Weathering

What does Weathering mean? Here you find 63 meanings of the word Weathering. You can also add a definition of Weathering yourself

1 |

0 Physical, chemical or biological breakdown of rocks and minerals into smaller sized particles.

|

2 |

0 WeatheringThe physical, chemical and biological processes that decompose rock at and below the surface of the Earth through low pressures and temperatures and the presence of air and water. Weathering includes [..]

|

3 |

0 WeatheringAltération des roches

|

4 |

0 WeatheringThe process by which Earth materials change when exposed to conditions at or near the Earth’s surface and different from the ones under which they formed. compare decomposition , disintegration .

|

5 |

0 WeatheringThe process a rock or mineral may go through when exposed to air, water, pressure, or wind. Exposure to these elements may chemically affected rocks or minerals in one way or another.

|

6 |

0 Weatheringthe breaking down or dissolving of the Earth’s surface rocks and minerals. Read more in the NG Education Encyclopedia

|

7 |

0 WeatheringThe mechanical, chemical, or biological action of the atmosphere, hydrometeors, and suspended impurities on the form, color, or constitution of exposed material; to be distinguished from erosion. Mech [..]

|

8 |

0 Weatheringn. The physical, chemical, and biological processes by which rock is broken down into smaller pieces.

|

9 |

0 WeatheringWhen rocks are eroded or broken down by wind and rain

|

10 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the process which changes a material in time. Or, in architecture, the slope on a buttress to shed rainwater.

|

11 |

0 Weatheringbreakdown of rock in situ by physical and chemical processes due to the presence of water, plants and animals. Rates vary according to additional controls of temperature, rock type and time. (see phys [..]

|

12 |

0 Weatheringthe surface deterioration of a hose cover during outdoor exposure as shown by checking, cracking, crazing and chalking

|

13 |

0 Weathering"Making little ones out of big ones." Waethering includes the processes which mechanically and chemically break down the mountains into little pieces, so they can be eroded and trans [..]

|

14 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is when rocks are worn down by natural elements, such as water, wind, or ice.

|

15 |

0 Weatheringthe process by which rocks are broken down and decomposed by the action of factors such as wind, rain, ice, sunshine and also by plants and bacteria. Weathering can alter a rock’s form, texture a [..]

|

16 |

0 WeatheringNatural alteration by either chemical or mechanical processes due to the action of the atmosphere, surface waters, soil and other ground waters, or to temperature changes. Changes by weathering are no [..]

|

17 |

0 WeatheringChanges on the surface of glass caused by chemical reaction with the environment. Weathering usually involves the leaching of alkali from the glass by water, leaving behind siliceous weathering products that are often laminar.

|

18 |

0 Weathering(n) — the process by which a rock is broken into smaller pieces

|

19 |

0 Weathering(also Stain) Attack of a glass surface by atmospheric elements.

|

20 |

0 WeatheringA chemical or physical process in which rocks exposed to the weather are worn down by water, wind, or ice.

|

21 |

0 WeatheringThe physical disintegration and chemical decomposition of rock. [ return to top

|

22 |

0 WeatheringChanges on the surface of glass caused by chemical reaction with the environment. Weathering usually involves the leaching of alkali from the glass by water, leaving behind siliceous weathering products that are often laminar.

|

23 |

0 WeatheringThe tendency of some o-ring seals to surface crack upon exposure to atmospheres containing ozone and other pollutants. Width: An o-ring cut at a 90 degree angle to the mold parting line. The cross sectional diameter of an o-ring. Back

|

24 |

0 WeatheringThe mechanical or chemical disintegration and discoloration of the surface of wood caused by exposure to light. The action of dust and sand carried by winds and alternate shrinking and swelling of t [..]

|

25 |

0 Weatheringthe breakdown and decay of rock by its natural processes, without the involvement of any moving forces

|

26 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the wearing away of rocks. It can be weathering, biological or physical weathering.

|

27 |

0 Weatheringthe process by which water, wind, and ice break down rocks and other exposed surfaces into smaller pieces (sediments)

|

28 |

0 Weatheringthe chemical or physical break-down of rocks on the Earth’s surface

|

29 |

0 WeatheringSloping surface (to buttresses, hood-moulds, etc.) to throw off rain. (Wood, Margaret. The English Medieval House, 416)

|

30 |

0 WeatheringThe breakdown and changes in rocks and sediments at or near the Earth’s surface produced by biological, chemical, and physical agents or combinations of them.

|

31 |

0 WeatheringThe processes that cause exposed rock to break down (Lesson 27)

|

32 |

0 WeatheringThe physical, chemical, and biological processes by which rock is changed and broken down. A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z — X —

|

33 |

0 WeatheringWeathering includes two surface or near-surface processes that work in concert to decompose rocks. Both processes occur in place. No movement is involved in weathering. Chemical weathering

|

34 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the decomposition of rocks and soils at or near the Earth’s surface. See sections 2.3.2, 4.3.1, 4.3.2 and 5.3.2.

|

35 |

0 WeatheringThe surface deterioration of a hose cover during outdoor exposure, as shown by checking, cracking, crazing, and chalking.

|

36 |

0 WeatheringNatural alteration by either chemical or mechanical processes due to the action of constituents of the atmosphere, soil, surface waters, and other ground waters, or by temperature changes.

|

37 |

0 WeatheringThe mechanical or chemical disintegration and discoloration of the surface of wood caused by exposure to light. The action of dust and sand carried by winds and alternate shrinking and swelling of the surface fibers with continual variation in moisture content due to changes in the weather. Also an inclined surface on a member such as a cornice or [..]

|

38 |

0 Weatheringis the physical and chemical breakdown of rocks due to natural process.

|

39 |

0 WeatheringThe process during which a complex compound is reduced to its simpler component parts, transported via physical processes, or biodegraded over time.

|

40 |

0 WeatheringBehavior of paint films when exposed to natural weather or accelerated weathering equipment, characterized by changes in color, texture, strength, chemical composition or other properties.

|

41 |

0 WeatheringPassing to windward.

|

42 |

0 Weatheringthe natural processes by which the actions of atmospheric and other environmental agents, such as wind, rain, and temperture changes, result in the physical disintegration and chemical decomposition o [..]

|

43 |

0 WeatheringA relative term used in sailing to define the action of one vessel which is eating to windward of another, thus, if a vessel is said to he weathering on another she is eating her out of the wind, or c [..]

|

44 |

0 WeatheringThe mechanical breakdown and chemical alteration of rocks and minerals at Earth’s surface during exposure to air, moisture, and organic matter.

|

45 |

0 WeatheringThe passive act of a mineral that was exposed from the earth and was chemically affected in one way or another, either by air, water, pressure, or wind.

|

46 |

0 WeatheringThe processes of chemical alteration and mechanical deterioration of rocks and minerals at or very near to the surface that is caused by exposure to air, water, acids, and mechanical stresses.

|

47 |

0 WeatheringPhysical disintegration and chemical decomposition of earthy and rocky materials on exposure to atmospheric agents, producing an in-place mantle of waste.

|

48 |

0 WeatheringThe destructive processes by which rocks are changed on exposure to atmospheric agents at or near the earth’s surface, with little or no transport of the loosened or altered material.

|

49 |

0 WeatheringThe destructive effects of air, wind, water or ice, by which rocks are changed in colour, texture, composition or form. Most weathering occurs at the surface, but it may take place deep under the surface as water and oxygen penetrates into rocks through joints.

|

50 |

0 WeatheringThe change in appearance of paint caused by exposure to nature. The physical disintegration and chemical decomposition of materials on exposure to atmospheric agents

|

51 |

0 Weatheringthe natural process by which atmospheric and environmental agents, such as wind, rain, and temperature changes, disintegrate and decompose rocks

|

52 |

0 WeatheringThe decay and breakup of rocks on the earth’s surface by natural chemical and mechanical processes. The mechanical action includes large changes of temperature, extreme temperatures, frost, or the impact of wind borne sand or water. Chemical action includes the chemical reactions between atmospheric constituents in a moist environments or in r [..]

|

53 |

0 WeatheringThe decay and breakup of rocks on the earth’s surface by natural chemical and mechanical processes. The mechanical action includes large changes of temperature, extreme temperatures, frost, or th [..]

|

54 |

0 WeatheringThe decay and breakup of rocks on the earth’s surface by natural chemical and mechanical processes. The mechanical action includes large changes of temperature

|

55 |

0 WeatheringThe decay and breakup of rocks on the earth’s surface by natural chemical and mechanical processes. The mechanical action includes large changes of temperature, extreme temperatures, frost, or the impact of wind borne sand or water. Chemical action includes the chemical reactions between atmospheric constituents in a moist environments or in rain [..]

|

56 |

0 WeatheringThe process during which a complex compound is reduced to its simpler component parts, transported via physical processes, or biodegraded over time.

|

57 |

0 Weathering(obsolete) Weather, especially favourable or fair weather. (geology) Mechanical or chemical breaking down of rocks in situ by weather or other causes. (architecture) A slight inclination given t [..]

|

58 |

0 WeatheringThe disintegration of rocks and minerals on the Earth’s surface in situ.

|

59 |

0 WeatheringPhysical and chemical processes by which rocks and minerals are broken down by such environmental agents as rain, wind, temperature changes, and biological influences.

|

60 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the breaking down of rocks, soil, and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with the Earth’s atmosphere, water, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs i [..]

|

61 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the breaking down of rocks, soil, and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with the Earth’s atmosphere, water, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs i [..]

|

62 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the breaking down of rocks, soil, and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with the Earth’s atmosphere, water, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs i [..]

|

63 |

0 WeatheringWeathering is the breaking down of rocks, soil, and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with the Earth’s atmosphere, water, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs i [..]

|

Dictionary.university is a dictionary written by people like you and me.

Please help and add a word. All sort of words are welcome!

Add meaning

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

The best experience that we have on Earth is the fact that we have scientific stations, weathering over stations down in the Antarctic for almost the entire 20th century to learn how to exist in exceedingly hazardous conditions; and the Moon is far more hazardous than Antarctica. At least they have water there.

Edgar Mitchell

PRONUNCIATION OF WEATHERING

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF WEATHERING

Weathering is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES WEATHERING MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Weathering

Weathering is the breaking down of rocks, soil and minerals as well as artificial materials through contact with the Earth’s atmosphere, biota and waters. Weathering occurs in situ, or «with no movement», and thus should not be confused with erosion, which involves the movement of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity. Two important classifications of weathering processes exist – physical and chemical weathering; each sometimes involves a biological component. Mechanical or physical weathering involves the breakdown of rocks and soils through direct contact with atmospheric conditions, such as heat, water, ice and pressure. The second classification, chemical weathering, involves the direct effect of atmospheric chemicals or biologically produced chemicals also known as biological weathering in the breakdown of rocks, soils and minerals. While physical weathering is accentuated in very cold or very dry environments, chemical reactions are most intense where the climate is wet and hot. However, both types of weathering occur together, and each tends to accelerate the other.

Definition of weathering in the English dictionary

The definition of weathering in the dictionary is the mechanical and chemical breakdown of rocks by the action of rain, snow, cold, etc.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH WEATHERING

Synonyms and antonyms of weathering in the English dictionary of synonyms

SYNONYMS OF «WEATHERING»

The following words have a similar or identical meaning as «weathering» and belong to the same grammatical category.

Translation of «weathering» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF WEATHERING

Find out the translation of weathering to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of weathering from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «weathering» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

风化

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

meteorización

570 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

अपक्षय

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

التجوية

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

выветривания

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

intemperismo

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

weathering

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

érosion

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Luluhawa

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Verwitterung

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

風化

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

풍화

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Cuaca

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

nói về thời tiết

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

காலநிலையாக்க

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

हवामान

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

kötü havadan aşınma

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

agenti atmosferici

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

atmosferycznych

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

вивітрювання

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

intemperii

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

καιρικές συνθήκες

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

verwering

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

vittring

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

forvitring

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of weathering

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «WEATHERING»

The term «weathering» is quite widely used and occupies the 35.517 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Quite widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «weathering» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of weathering

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «weathering».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «WEATHERING» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «weathering» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «weathering» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about weathering

QUOTES WITH «WEATHERING»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word weathering.

The best experience that we have on Earth is the fact that we have scientific stations, weathering over stations down in the Antarctic for almost the entire 20th century to learn how to exist in exceedingly hazardous conditions; and the Moon is far more hazardous than Antarctica. At least they have water there.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «WEATHERING»

Discover the use of weathering in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to weathering and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

On Weathering: The Life of Buildings in Time

In a clear and direct account, supplemented by photographs, Mostafavi and Leatherbarrow examine buildings and other projects to show that continual refinishing of a building by natural forces is a continuation of the building process rather …

2

Weathering: An Introduction to the Basic Principles

Weathering is the initial process which exposes the top few layers of the Earth to the potential for change. This book provides an introduction to the scientific principles behind mechanical, chemical and biological weathering.

Will J. Bland, David Rolls, 1998

3

Done in a Day: Easy Detailing and Weathering Projects for …

More than a dozen easy weathering and detailing projects show you how to add realism to rolling stock and locomotives. Beginning modelers will appreciate the well-illustrated, easy-to-follow instructions.

4

Weathering the Storm: Working-class Families from the …

In this challenging sequel to A Millennium of Family Change Wally Seccombe examines in detail the ways in which large-scale economic changes shape the microcosm of personal life.

Investigates the key agents of weathering and erosion, explains how they have worked over time to change the appearance of the planet’s landscapes, and discusses the many diverse physical features that have been created and shaped by water, …

6

Heritage, Weathering and Conservation

This book will be useful to professionals and scientists working in a variety of fields related to heritage: geologists, geographers, chemists, physicists, biologists, architects, engineers, restorers, historians, archaeologists, policy …

Rafael Fort, Alvarez De Buergo Ballest Staff, Monica Alvarez de Buergo, 2006

7

Surface and Ground Water, Weathering, and Soils: Treatise on …

Volume 5 has several objectives. The first is to present an overview of the composition of surface and ground waters on the continents and the mechanisms that control the compositions.

8

Weathering the World: Recovery in the Wake of the Tsunami in …

The Asian tsunami in December 2004 severely affected people in coastal regions all around the Indian Ocean. This book provides the first in-depth ethnography of the disaster and its effects on a fishing village in Tamil Nadu, India.

9

Weathering Winter: A Gardener’s Daybook

In his distinctive daybook, Weathering Winter, Carl Klaus reminds readers that the season of brown twigs and icy gales is just as much a part of the year as when tulips open, tomatoes thrive, and pumpkins color the brown earth.

10

Weathering: Poems and Translations

Alastair Reid began publishing poetry in the New Yorker in 1951 and has since contributed reviews, translations, stories, and reportage as well.

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «WEATHERING»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term weathering is used in the context of the following news items.

Weathering the storm: a windswept history of the Open

Weathering the storm: a windswept history of the Open. After the monsoon-like conditions at St Andrews, we look back at the famous old competition and its … «The Guardian, Jul 15»

Stress test shows Commerce weathering a crisis

A hypothetical next financial crisis would leave Commerce Bancshares with slightly less in loan losses than it suffered in the last crisis, according to stress test … «STLtoday.com, Jun 15»

Weathering the storm: Walmart is preparing for natural disasters

The world’s biggest retailer is often the first to help communities when disaster strikes. Whether it’s a tornado or flood, more and more big companies are doing … «ABC Action News, Jun 15»

Putin says Russia weathering sanctions, lectures West

ST PETERSBURG, Russia President Vladimir Putin boasted on Friday that Russia had found the «inner strength» to prevent sanctions causing a deep economic … «Reuters, Jun 15»

During Ice Age Cycles, Weathering And River Discharge Were …

Scientists expect weathering rates to slow down during Earth’s ice ages because temperatures were lower, and as a consequence much of the water that might … «Science 2.0, Jun 15»

Weathering and river discharge surprisingly constant during Ice Age …

Scientists expect weathering rates to slow down during Earth’s ice ages because temperatures were lower, and as a consequence much of the water that might … «Phys.Org, Jun 15»

Denver’s Homeless Shelters Weathering The Cold But Still Need Help

DENVER (CBS4) – Homeless shelters across the metro area have been working overtime to accommodate those who are less fortunate during Denver’s cold … «CBS Local, Feb 15»

Balance, Efficiency Key to Hess Weathering Low Oil Price Storm

Rigzone talks with Hess’ Senior Vice President of Offshore Brian Truelove on the company’s strategy for weathering the low oil price environment. Hess Corp. «Rigzone, Feb 15»

Weathering review – Lucy Wood’s beautifully atmospheric debut

In one sense, then, Weathering is a ghost story, but it feels more concrete than that. Anyone who catches themselves talking to a dead relative in the midst of … «The Guardian, Feb 15»

Weathering Late Rally, Islanders Reach First

Mikhail Grabovski’s shot from the slot midway through the second period stood up as the winning goal for the Islanders, who hung on for a 3-2 victory over the … «New York Times, Feb 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Weathering [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/weathering>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

When rocks are gradually worn away by water, salt, wind, plants, and animals, it’s called weathering. Many of the world’s most breathtaking rock formations are the result of weathering.

Weathering is the process of rocks disintegrating due to weather conditions or other biological causes. This includes chemical effects caused by minerals, physical pressure from plants or animals, and the scraping of ice as it freezes and thaws. During weathering, the worn-away pieces of rock stay nearby; if they’re swept away by water or wind, that’s called erosion.

Definitions of weathering

-

noun

a geological process in which a given substance wears away due to exposure to the atmosphere

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘weathering’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up weathering for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

What Does Weathering Mean?

Weathering is breaking down rocks, soil, and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials by contacting the atmosphere, water, and biological organisms of the Earth. Weathering takes place in situ, i.e. in the same place, with little or no movement. It should therefore not be confused with erosion involving the movement of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity, and then transported and deposited elsewhere.

There are two important weathering process classifications–physical and chemical weathering; each involves a biological component at times. Mechanical or physical weathering involves rock and soil breakdown by direct contact with atmospheric conditions such as heat, water, ice and pressure.

The second classification, chemical weathering, involves the direct effect in the breakdown of rocks, soils and minerals of atmospheric chemicals or biologically produced chemicals also known as biological weathering. While physical weathering is emphasized in very cold or very dry environments, where the climate is wet and hot, chemical reactions are most intense. Both types of weathering, however, take place together, and each tends to speed up the other.

How Rocks Are Weathered?

Once a rock is broken down, the bits of rock and mineral are carried away by a process called erosion. No rock on Earth is hard enough to resist weathering and erosion forces.

Weathering is often divided into mechanical weathering and weathering processes. Biological weathering may be part of both processes, in which living or once – living organisms contribute to weathering.

Physical Weathering

Physical weathering, also known as mechanical weathering or disaggregation, is the process class that causes rocks to disintegrate without chemical change. Abrasion (the process by which clasts and other particles are reduced in size) is the primary process in physical weathering.

Due to temperature, pressure, frost etc., physical weather may occur. For instance, cracks exploited by physical weathering will increase the surface area that is exposed to chemical action, thereby increasing the rate of disintegration.

Where does Physical Weathering occur?

In places where there is little soil and few plants grow, such as mountain regions and hot deserts, physical weathering occurs especially.

How does Physical Weathering occur?

Either by repeated melting and freezing of water (mountains and tundra) or by expanding and shrinking the surface layer of rocks baked by the sun (hot deserts).

Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering changes rock composition, often transforming them into different chemical reactions when water interacts with minerals. Chemical weathering is a gradual and ongoing process as the rock mineralogy adjusts to the environment near the surface.

The rock’s original minerals develop new or secondary minerals. The oxidation and hydrolysis processes are most important in this. Chemical weathering is enhanced by geological agents such as water and oxygen, as well as biological agents such as microbial and plant-root metabolism acids.

Where does Chemical Weathering occur?

These chemical processes require water and occur faster at higher temperatures, so it is best to have warm, humid climates. The first stage in soil production is chemical weathering (especially hydrolysis and oxidation).

How does Chemical Weathering occur?

There are various types of chemical weathering, the most important of which is:

Solution