An adjective (abbreviated adj.) is a word that describes a noun or noun phrase. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives were considered one of the main parts of speech of the English language, although historically they were classed together with nouns.[1] Nowadays, certain words that usually had been classified as adjectives, including the, this, my, etc., typically are classed separately, as determiners.

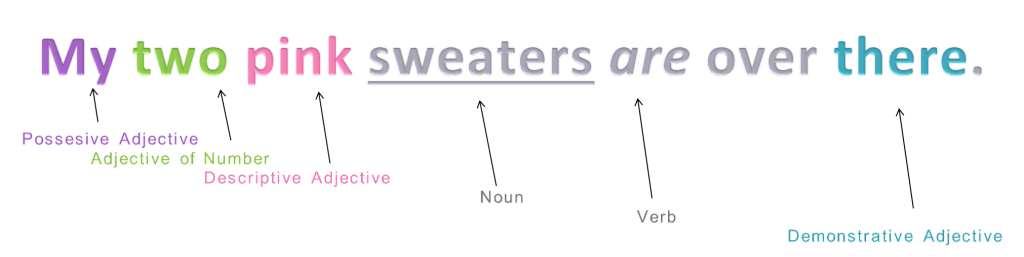

Here are some examples:

- That’s a funny idea. (attributive)

- That idea is funny. (predicative)

- Tell me something funny. (postpositive)

- The good, the bad, and the funny. (substantive)

Etymology[edit]

Adjective comes from Latin nōmen adjectīvum,[2] a calque of Ancient Greek: ἐπίθετον ὄνομα, romanized: epítheton ónoma, lit. ‘additional noun’ (whence also English epithet).[3][4] In the grammatical tradition of Latin and Greek, because adjectives were inflected for gender, number, and case like nouns (a process called declension), they were considered a type of noun. The words that are today typically called nouns were then called substantive nouns (nōmen substantīvum).[5] The terms noun substantive and noun adjective were formerly used in English but are now obsolete.[1]

Types of use[edit]

Depending on the language, an adjective can precede a corresponding noun on a prepositive basis or it can follow a corresponding noun on a postpositive basis. Structural, contextual, and style considerations can impinge on the pre-or post-position of an adjective in a given instance of its occurrence. In English, occurrences of adjectives generally can be classified into one of three categories:

- Prepositive adjectives, which are also known as «attributive adjectives», occur on an antecedent basis within a noun phrase.[6] For example: «I put my happy kids into the car», wherein happy occurs on an antecedent basis within the my happy kids noun phrase, and therefore functions in a prepositive adjective.

- Postpositive adjectives can occur: (a) immediately subsequent to a noun within a noun phrase, e.g. «The only room available cost twice what we expected»; (b) as linked via a copula or other linking mechanism subsequent to a corresponding noun or pronoun; for example: «My kids are happy«, wherein happy is a predicate adjective[6] (see also: Predicative expression, Subject complement); or (c) as an appositive adjective within a noun phrase, e.g. «My kids, [who are] happy to go for a drive, are in the back seat.»

- Nominalized adjectives, which function as nouns. One way this happens is by eliding a noun from an adjective-noun noun phrase, whose remnant thus is a nominalization. In the sentence, «I read two books to them; he preferred the sad book, but she preferred the happy», happy is a nominalized adjective, short for «happy one» or «happy book». Another way this happens is in phrases like «out with the old, in with the new», where «the old» means «that which is old» or «all that is old», and similarly with «the new». In such cases, the adjective may function as a mass noun (as in the preceding example). In English, it may also function as a plural count noun denoting a collective group, as in «The meek shall inherit the Earth», where «the meek» means «those who are meek» or «all who are meek».

Distribution[edit]

Adjectives feature as a part of speech (word class) in most languages. In some languages, the words that serve the semantic function of adjectives are categorized together with some other class, such as nouns or verbs. In the phrase «a Ford car», «Ford» is unquestionably a noun but its function is adjectival: to modify «car». In some languages adjectives can function as nouns: for example, the Spanish phrase «un rojo» means «a red [one]».

As for «confusion» with verbs, rather than an adjective meaning «big», a language might have a verb that means «to be big» and could then use an attributive verb construction analogous to «big-being house» to express what in English is called a «big house». Such an analysis is possible for the grammar of Standard Chinese, for example.

Different languages do not use adjectives in exactly the same situations. For example, where English uses «to be hungry» (hungry being an adjective), Dutch, French, and Spanish use «honger hebben«, «avoir faim«, and «tener hambre» respectively (literally «to have hunger», the words for «hunger» being nouns). Similarly, where Hebrew uses the adjective זקוק (zaqūq, roughly «in need of»), English uses the verb «to need».

In languages that have adjectives as a word class, it is usually an open class; that is, it is relatively common for new adjectives to be formed via such processes as derivation. However, Bantu languages are well known for having only a small closed class of adjectives, and new adjectives are not easily derived. Similarly, native Japanese adjectives (i-adjectives) are considered a closed class (as are native verbs), although nouns (an open class) may be used in the genitive to convey some adjectival meanings, and there is also the separate open class of adjectival nouns (na-adjectives).

Adverbs[edit]

Many languages (including English) distinguish between adjectives, which qualify nouns and pronouns, and adverbs, which mainly modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. Not all languages make this exact distinction; many (including English) have words that can function as either. For example, in English, fast is an adjective in «a fast car» (where it qualifies the noun car) but an adverb in «he drove fast» (where it modifies the verb drove).

In Dutch and German, adjectives and adverbs are usually identical in form and many grammarians do not make the distinction, but patterns of inflection can suggest a difference:

- Eine kluge neue Idee.

- A clever new idea.

- Eine klug ausgereifte Idee.

- A cleverly developed idea.

A German word like klug («clever(ly)») takes endings when used as an attributive adjective but not when used adverbially. (It also takes no endings when used as a predicative adjective: er ist klug, «he is clever».) Whether these are distinct parts of speech or distinct usages of the same part of speech is a question of analysis. It can be noted that, while German linguistic terminology distinguishes adverbiale from adjektivische Formen, German refers to both as Eigenschaftswörter («property words»).

Determiners[edit]

Linguists today distinguish determiners from adjectives, considering them to be two separate parts of speech (or lexical categories). Determiners formerly were considered to be adjectives in some of their uses.[a] Determiners function neither as nouns nor pronouns but instead characterize a nominal element within a particular context. They generally do this by indicating definiteness (a vs. the), quantity (one vs. some vs. many), or another such property.

Adjective phrases[edit]

An adjective acts as the head of an adjective phrase or adjectival phrase (AP). In the simplest case, an adjective phrase consists solely of the adjective; more complex adjective phrases may contain one or more adverbs modifying the adjective («very strong»), or one or more complements (such as «worth several dollars«, «full of toys«, or «eager to please«). In English, attributive adjective phrases that include complements typically follow the noun that they qualify («an evildoer devoid of redeeming qualities«).

Other modifiers of nouns[edit]

In many languages (including English) it is possible for nouns to modify other nouns. Unlike adjectives, nouns acting as modifiers (called attributive nouns or noun adjuncts) usually are not predicative; a beautiful park is beautiful, but a car park is not «car». The modifier often indicates origin («Virginia reel»), purpose («work clothes»), semantic patient («man eater») or semantic subject («child actor»); however, it may generally indicate almost any semantic relationship. It is also common for adjectives to be derived from nouns, as in boyish, birdlike, behavioral (behavioural), famous, manly, angelic, and so on.

In Australian Aboriginal languages, the distinction between adjectives and nouns is typically thought weak, and many of the languages only use nouns—or nouns with a limited set of adjective-deriving affixes—to modify other nouns. In languages that have a subtle adjective-noun distinction, one way to tell them apart is that a modifying adjective can come to stand in for an entire elided noun phrase, while a modifying noun cannot. For example, in Bardi, the adjective moorrooloo ‘little’ in the phrase moorrooloo baawa ‘little child’ can stand on its own to mean ‘the little one,’ while the attributive noun aamba ‘man’ in the phrase aamba baawa ‘male child’ cannot stand for the whole phrase to mean ‘the male one.’[7] In other languages, like Warlpiri, nouns and adjectives are lumped together beneath the nominal umbrella because of their shared syntactic distribution as arguments of predicates. The only thing distinguishing them is that some nominals seem to semantically denote entities (typically nouns in English) and some nominals seem to denote attributes (typically adjectives in English).[8]

Many languages have participle forms that can act as noun modifiers either alone or as the head of a phrase. Sometimes participles develop into functional usage as adjectives. Examples in English include relieved (the past participle of relieve), used as an adjective in passive voice constructs such as «I am so relieved to see you». Other examples include spoken (the past participle of speak) and going (the present participle of go), which function as attribute adjectives in such phrases as «the spoken word» and «the going rate».

Other constructs that often modify nouns include prepositional phrases (as in «a rebel without a cause«), relative clauses (as in «the man who wasn’t there«), and infinitive phrases (as in «a cake to die for«). Some nouns can also take complements such as content clauses (as in «the idea that I would do that«), but these are not commonly considered modifiers. For more information about possible modifiers and dependents of nouns, see Components of noun phrases.

Order[edit]

In many languages, attributive adjectives usually occur in a specific order. In general, the adjective order in English can be summarised as: opinion, size, age or shape, colour, origin, material, purpose.[9][10][11] Other language authorities, like the Cambridge Dictionary, state that shape precedes rather than follows age.[9][12][13]

Determiners and postdeterminers—articles, numerals, and other limiters (e.g. three blind mice)—come before attributive adjectives in English. Although certain combinations of determiners can appear before a noun, they are far more circumscribed than adjectives in their use—typically, only a single determiner would appear before a noun or noun phrase (including any attributive adjectives).

- Opinion – limiter adjectives (e.g. a real hero, a perfect idiot) and adjectives of subjective measure (e.g. beautiful, interesting) or value (e.g. good, bad, costly)

- Size – adjectives denoting physical size (e.g. tiny, big, extensive)

- Shape or physical quality – adjectives describing more detailed physical attributes than overall size (e.g. round, sharp, swollen, thin)

- Age – adjectives denoting age (e.g. young, old, new, ancient, six-year-old)

- Colour – adjectives denoting colour or pattern (e.g. white, black, pale, spotted)

- Origin – denominal adjectives denoting source (e.g. Japanese, volcanic, extraterrestrial)

- Material – denominal adjectives denoting what something is made of (e.g., woollen, metallic, wooden)

- Qualifier/purpose – final limiter, which sometimes forms part of the (compound) noun (e.g., rocking chair, hunting cabin, passenger car, book cover)

This means that, in English, adjectives pertaining to size precede adjectives pertaining to age («little old», not «old little»), which in turn generally precede adjectives pertaining to colour («old white», not «white old»). So, one would say «One (quantity) nice (opinion) little (size) old (age) round (shape) [or round old] white (colour) brick (material) house.» When several adjectives of the same type are used together, they are ordered from general to specific, like «lovely intelligent person» or «old medieval castle».[9]

This order may be more rigid in some languages than others; in some, like Spanish, it may only be a default (unmarked) word order, with other orders being permissible. Other languages, such as Tagalog, follow their adjectival orders as rigidly as English.

The normal adjectival order of English may be overridden in certain circumstances, especially when one adjective is being fronted. For example, the usual order of adjectives in English would result in the phrase «the bad big wolf» (opinion before size), but instead, the usual phrase is «the big bad wolf».

Owing partially to borrowings from French, English has some adjectives that follow the noun as postmodifiers, called postpositive adjectives, as in time immemorial and attorney general. Adjectives may even change meaning depending on whether they precede or follow, as in proper: They live in a proper town (a real town, not a village) vs. They live in the town proper (in the town itself, not in the suburbs). All adjectives can follow nouns in certain constructions, such as tell me something new.

Comparison (degrees)[edit]

In many languages, some adjectives are comparable and the measure of comparison is called degree. For example, a person may be «polite», but another person may be «more polite», and a third person may be the «most polite» of the three. The word «more» here modifies the adjective «polite» to indicate a comparison is being made, and «most» modifies the adjective to indicate an absolute comparison (a superlative).

Among languages that allow adjectives to be compared, different means are used to indicate comparison. Some languages do not distinguish between comparative and superlative forms. Other languages allow adjectives to be compared but do not have a special comparative form of the adjective. In such cases, as in some Australian Aboriginal languages, case-marking, such as the ablative case may be used to indicate one entity has more of an adjectival quality than (i.e. from—hence ABL) another. Take the following example in Bardi:[7]

Jalnggoon oysters are bigger than niwarda oysters

In English, many adjectives can be inflected to comparative and superlative forms by taking the suffixes «-er» and «-est» (sometimes requiring additional letters before the suffix; see forms for far below), respectively:

- «great», «greater», «greatest»

- «deep», «deeper», «deepest»

Some adjectives are irregular in this sense:

- «good», «better», «best»

- «bad», «worse», «worst»

- «many», «more», «most» (sometimes regarded as an adverb or determiner)

- «little», «less», «least»

Some adjectives can have both regular and irregular variations:

- «old», «older», «oldest»

- «far», «farther», «farthest»

also

- «old», «elder», «eldest»

- «far», «further», «furthest»

Another way to convey comparison is by incorporating the words «more» and «most». There is no simple rule to decide which means is correct for any given adjective, however. The general tendency is for simpler adjectives and those from Anglo-Saxon to take the suffixes, while longer adjectives and those from French, Latin, or Greek do not—but sometimes sound of the word is the deciding factor.

Many adjectives do not naturally lend themselves to comparison. For example, some English speakers would argue that it does not make sense to say that one thing is «more ultimate» than another, or that something is «most ultimate», since the word «ultimate» is already absolute in its semantics. Such adjectives are called non-comparable or absolute. Nevertheless, native speakers will frequently play with the raised forms of adjectives of this sort. Although «pregnant» is logically non-comparable (either one is pregnant or not), one may hear a sentence like «She looks more and more pregnant each day». Likewise «extinct» and «equal» appear to be non-comparable, but one might say that a language about which nothing is known is «more extinct» than a well-documented language with surviving literature but no speakers, while George Orwell wrote, «All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others». These cases may be viewed as evidence that the base forms of these adjectives are not as absolute in their semantics as is usually thought.

Comparative and superlative forms are also occasionally used for other purposes than comparison. In English comparatives can be used to suggest that a statement is only tentative or tendential: one might say «John is more the shy-and-retiring type,» where the comparative «more» is not really comparing him with other people or with other impressions of him, but rather, could be substituting for «on the whole» or «more so than not». In Italian, superlatives are frequently used to put strong emphasis on an adjective: bellissimo means «most beautiful», but is in fact more commonly heard in the sense «extremely beautiful».

Restrictiveness[edit]

Attributive adjectives and other noun modifiers may be used either restrictively (helping to identify the noun’s referent, hence «restricting» its reference) or non-restrictively (helping to describe a noun). For example:

- He was a lazy sort, who would avoid a difficult task and fill his working hours with easy ones.

Here «difficult» is restrictive – it tells which tasks he avoids, distinguishing these from the easy ones: «Only those tasks that are difficult».

- She had the job of sorting out the mess left by her predecessor, and she performed this difficult task with great acumen.

Here «difficult» is non-restrictive – it is already known which task it was, but the adjective describes it more fully: «The aforementioned task, which (by the way) is difficult»

In some languages, such as Spanish, restrictiveness is consistently marked; for example, in Spanish la tarea difícil means «the difficult task» in the sense of «the task that is difficult» (restrictive), whereas la difícil tarea means «the difficult task» in the sense of «the task, which is difficult» (non-restrictive). In English, restrictiveness is not marked on adjectives but is marked on relative clauses (the difference between «the man who recognized me was there» and «the man, who recognized me, was there» being one of restrictiveness).

Agreement[edit]

In some languages, adjectives alter their form to reflect the gender, case and number of the noun that they describe. This is called agreement or concord. Usually it takes the form of inflections at the end of the word, as in Latin:

-

puella bona (good girl, feminine singular nominative) puellam bonam (good girl, feminine singular accusative/object case) puer bonus (good boy, masculine singular nominative) pueri boni (good boys, masculine plural nominative)

In Celtic languages, however, initial consonant lenition marks the adjective with a feminine singular noun, as in Irish:

-

buachaill maith (good boy, masculine) girseach mhaith (good girl, feminine)

Here, a distinction may be made between attributive and predicative usage. In English, adjectives never agree, whereas in French, they always agree. In German, they agree only when they are used attributively, and in Hungarian, they agree only when they are used predicatively:

-

The good (Ø) boys. The boys are good (Ø). Les bons garçons. Les garçons sont bons. Die braven Jungen. Die Jungen sind brav (Ø). A jó (Ø) fiúk. A fiúk jók.

Semantics[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: other aspects of adjective semantics. You can help by adding to it. (talk) (August 2022) |

Semanticist Barbara Partee classifies adjectives semantically as intersective, subsective, or nonsubsective, with nonsubsective adjectives being plain nonsubsective or privative.[14]

- An adjective is intersective if and only if the extension of its combination with a noun is equal to the intersection of its extension and that of the noun its modifying. For example, the adjective carnivorous is intersective, given the extension of carnivorous mammal is the intersection of the extensions of carnivorous and mammal (i.e., the set of all mammals who are carnivorous).

- An adjective is subsective if and only if the extension of its combination with a noun is a subset of the extension of the noun. For example, the extension of skillful surgeon is a subset of the extension of surgeon, but it is not the intersection of that and the extension of skillful, as that would include (for example) incompetent surgeons who are skilled violinists. All subsective adjectives are intersective, but the term ‘subsective’ is sometimes used to refer to only those subsective adjectives which are not intersective.

- An adjective is privative if and only if the extension of its combination with a noun is disjoint from the extension of the noun. For example, fake is privative because a fake cat is not a cat.

- A plain nonsubsective adjective is an adjective that is not subsective or privative. For example, the word possible is this kind of adjective, as the extension of possible murderer overlaps with, but is not included in the extension of murderer (as some, but not all, possible murderers are murderers).

See also[edit]

- Attributive verb

- Flat adverb

- Grammatical modifier

- Intersective modifier

- List of eponymous adjectives in English

- Noun adjunct

- Part of speech

- Predication (philosophy)

- Privative adjective

- Proper adjective

- Subsective modifier

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ In English dictionaries, which typically still do not treat determiners as their own part of speech, determiners are often recognizable by being listed both as adjectives and as pronouns.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Trask, R.L. (2013). A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in Linguistics. Taylor & Francis. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-134-88420-9.

- ^ adjectivus. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ ἐπίθετος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Mastronarde, Donald J. Introduction to Attic Greek. University of California Press, 2013. p. 60.

- ^ McMenomy, Bruce A. Syntactical Mechanics: A New Approach to English, Latin, and Greek. University of Oklahoma Press, 2014. p. 8.

- ^ a b See: «Attributive and predicative adjectives» at Lexico, archived 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b Bowern, Claire (2013). A grammar of Bardi. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-027818-7. OCLC 848086054.

- ^ Simpson, Jane (6 December 2012). Warlpiri Morpho-Syntax : a Lexicalist Approach. Dordrecht. ISBN 978-94-011-3204-6. OCLC 851384391.

- ^ a b c Order of adjectives, British Council.

- ^ R.M.W. Dixon, «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?» Studies in Language 1, no. 1 (1977): 19–80.

- ^ Dowling, Tim (13 September 2016). «Order force: the old grammar rule we all obey without realising». The Guardian.

- ^ Adjectives: order (from English Grammar Today), in the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary online

- ^ R. Declerck, A Comprehensive Descriptive Grammar of English (1991), p. 350: «When there are several descriptive adjectives, they normally occur in the following order: characteristic – size – shape – age – colour – […]»

- ^ Partee, Barbara (1995). «Lexical semantics and compositionality». In Gleitman, Lila; Liberman, Mark; Osherson, Daniel N. (eds.). An Invitation to Cognitive Science: Language. The MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3964.003.0015. ISBN 978-0-262-15044-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1977). «Where Have All the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1993). R. E. Asher (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (1st ed.). Pergamon Press Inc. pp. 29–35. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1999). «Adjectives». In K. Brown & T. Miller (eds.), Concise Encyclopedia of Grammatical Categories. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-043164-X. pp. 1–8.

- Rießler, Michael (2016). Adjective Attribution. Language Science Press. ISBN 9783944675657.

- Warren, Beatrice (1984). Classifying adjectives. Gothenburg studies in English No. 56. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. ISBN 91-7346-133-4.

- Wierzbicka, Anna (1986). «What’s in a Noun? (Or: How Do Nouns Differ in Meaning from Adjectives?)». Studies in Language. 10 (2): 353–389. doi:10.1075/sl.10.2.05wie.

External links[edit]

Look up adjective in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- List of English collateral adjectives at Wiktionary

1.1. Adjectives: General Characteristic

Adjectives

belong to an Open-class system. That is this class is open to new

membership since there are productive word-building affixes.

Adjectives are semantically diversified and can be subgrouped along

different lines of semantic classification.

The

adjective (fr. two Latin words ad

– pertaining to, and

jacia

– throw)

expresses the categorial semantics of property of a substance. Each

adjective used in the text presupposes relation to some noun the

property of whose referent it denotes (material, colour, dimensions,

position, state, and other permanent and temporary characteristics).

Thus

adjectives do not possess a full nominative value. They exist only in

collocations showing for ex. what is long,

who is hospitable,

what is fragrant.

Adjectives

are a well-defined part of speech in Modern English.

If

the adjective is placed in a nominatively self-dependent position,

this leads to its substantivisation

(the

sun tinged the snow with red).

Syntactical

function of adjectives:

-

an

attribute -

a

predicative.

Combinability

of adjectives:

-

with

nouns (usu in pre-position); -

with

link-verbs; -

with

modifying adverbs. -

when

used as predicatives or post-positional attributes, certain

adjectives demonstrate complementive combinability with nouns (fond

of,

jealous of,

curious of).

Such adjectival collocations render:

verbal

meanings (be

fond of – love, like; be envious of – envy; be angry with –

resent).

relations

of addressee (grateful

to, indebted to, partial to, useful for).

The

derivational features of adjectives:

The

adjectival suffixes

are non-productive (-y,

-ish, -ly)

and productive (-ful,

-less, -ish, -ous, -ive, -ic).

Some adjectives exist in two derivative forms, thus differing in

style, or in an implication (comical

– comic; poetic – poetical).

There

are adjectival prefixes proper (un-,

il-, a-)

and other prefixes belonging to a deriving stem of a corresponding

verb or noun (co-operat-ive;

super-natur-al).

Compounding

is also observed in adjectives and it is considered to be a very

productive way of word-building (white-headed,

lilly-white).

The

variable/demutative morphological features of adjectives:

The

English adjective is distinguished by the hybrid category of

comparison and have two types of paradigm – a synthetic and an

analytic ones.

1.2. Subclasses of Adjectives

The

adjectives are traditionally divided into:

1)Qualitative

Qualitative

adjectives denote various qualities of substances which admit of a

quantitative estimation. The measure of a quality can be estimated as

high or low, adequate or inadequate, sufficient or insufficient,

optimal or excessive (an

awkward situation – a very awkward situation; a difficult task –

too difficult a task; an enthusiastic reception – rather an

enthusiastic reception; a hearty welcome — not a very hearty

welcome).

2) Relative.

Relative

adjectives express the properties of a substance determined by the

direct relation of the substance to some other substance (wood

– a wooden hut; mathematics – mathematical precision; history –

a historical event; colour – coloured postcards; the Middle Ages –

mediaeval rites).

The

ability of an adjective to form degrees of comparison is usually

taken as a formal sign of its qualitative character however, in

actual speech the described principle of distinction is not at all

strictly observed.

In

order to overcome the of rigour in the definitions, an additional

linguistic division based on the evaluative function of adjectives

was introduced:

-

evaluative

(giving some qualitative evaluation to the substance referent) -

specificative

(only

pointing out the corresponding native property of the substance

referent).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Adjectives describe or modify—that is, they limit or restrict the meaning of—nouns and pronouns. They may name qualities of all kinds: huge, red, angry, tremendous, unique, rare, etc.

An adjective usually comes right before a noun: «a red dress,» «fifteen people.» When an adjective follows a linking verb such as be or seem, it is called a predicate adjective: «That building is huge,» «The workers seem happy.» Most adjectives can be used as predicate adjectives, although some are always used before a noun. Similarly, a few adjectives can only be used as predicate adjectives and are never used before a noun.

Some adjectives describe qualities that can exist in different amounts or degrees. To do this, the adjective will either change in form (usually by adding -er or -est) or will be used with words like more, most, very, slightly, etc.: «the older girls,» «the longest day of the year,» «a very strong feeling,» «more expensive than that one.» Other adjectives describe qualities that do not vary—»nuclear energy,» «a medical doctor»—and do not change form.

The four demonstrative adjectives—this, that, these, and those—are identical to the demonstrative pronouns. They are used to distinguish the person or thing being described from others of the same category or class. This and these describe people or things that are nearby, or in the present. That and those are used to describe people or things that are not here, not nearby, or in the past or future. These adjectives, like the definite and indefinite articles (a, an, and the), always come before any other adjectives that modify a noun.

An indefinite adjective describes a whole group or class of people or things, or a person or thing that is not identified or familiar. The most common indefinite adjectives are: all, another, any, both, each, either, enough, every, few, half, least, less, little, many, more, most, much, neither, one (and two, three, etc.), other, several, some, such, whole.

The interrogative adjectives—primarily which, what, and whose—are used to begin questions. They can also be used as interrogative pronouns.

Which horse did you bet on? = Which did you bet on?

What songs did they sing? = What did they sing?

Whose coat is this? = Whose is this?

The possessive adjectives—my, your, his, her, its, our, their—tell you who has, owns, or has experienced something, as in «I admired her candor, «Our cat is 14 years old,» and «They said their trip was wonderful.»

Nouns often function like adjectives. When they do, they are called attributive nouns.

When two or more adjectives are used before a noun, they should be put in proper order. Any article (a, an, the), demonstrative adjective (that, these, etc.), indefinite adjective (another, both, etc.), or possessive adjective (her, our, etc.) always comes first. If there is a number, it comes first or second. True adjectives always come before attributive nouns. The ordering of true adjectives will vary, but the following order is the most common:

opinion word→ size→ age→ shape→ color→ nationality→ material.

Participles are often used like ordinary adjectives. They may come before a noun or after a linking verb. A present participle (an -ing word) describes the person or thing that causes something; for example, a boring conversation is one that bores you. A past participle (usually an -ed word) describes the person or thing who has been affected by something; for example, a bored person is one who has been affected by boredom.

They had just watched an exciting soccer game.

The instructions were confusing.

She’s excited about the trip to North Africa.

Several confused students were asking questions about the test.

The lake was frozen.

Types of Adjective

There are several types of adjective such as: Adjectives of quality, Adjectives of Quantity, Numeral Adjectives, Demonstrative Adjectives, Possessive Adjectives, and Interrogative adjectives.

Let us discuss each type of adjective in more detail.

Adjectives of Quality

Adjectives of quality describe the kind, quality, or degree, of a noun or pronoun. They are also called Descriptive Adjectives.

Examples:

He ate a big mango.

Hassan is an honest man.

The child is foolish.

Arabic language is not hard to learn.

In the last example, the word Arabic is a proper noun. Such adjectives which are formed from proper nouns are called sometimes as Proper Adjectives. They generally come under the category of adjectives of quality.

Adjectives of Quantity

These adjectives tell us about the quantity of a noun. They answer the question: How much?

Common adjectives of quantity are: some, much, no, any, little, enough, great, half, sufficient

Examples:

Take great care of your grandma’s health.

The pay is enough for my expenses.

Half of the papers were checked.

Adjectives of Number | Numeral Adjectives

Adjectives of Number tell us about how many things or people are meant or the order of standing of people or things. These are also called Numeral Adjectives.

There are of three types of adjectives of number (numeral adjective): Definite Numeral Adjectives, Indefinite Numeral Adjectives and Distributive Numeral Adjectives.

1. Definite Numeral Adjectives: These represent an accurate number. Definite numeral adjectives are of further two types: Cardinals and Ordinals.

(a) Cardinals indicate how many. Such as: One, two, three, etc.

Example: I have three pairs of scissors.

(b) Ordinals indicate in which order. Such as: First, second, third, etc.

Example: She was the first one to arrive at the airport.

2. Indefinite Numeral Adjectives: Indefinite Numeral Adjectives do not represent an accurate number. Some of the common indefinite numeral adjectives are:

No, all, few, many, some, several, any, etc.

Examples in sentences:

All the cats are sleeping.

I have taken several different baking lessons.

There are no pedestrians on the street.

3. Distributive Numeral Adjectives: These adjectives refer to a specific or all things or people of a bunch. Some common Distributive Numeral Adjectives are:

Every, each, either, neither

Examples in sentences:

Each student must take its turn.

Neither proposal is acceptable.

Demonstrative Adjectives

Demonstrative Adjectives point to a specific person or thing. They answer the question: Which? Some common demonstrative adjectives are:

This, that, these, those, such

Examples:

This is my assignment.

Those are spicy dishes.

Such an attitude will cause him failure.

Interrogative Adjectives

Interrogative adjectives are used to ask questions. When what, whose and which are used with a noun to ask questions, they become interrogative adjectives. Interrogative adjectives are only three and are very easy to remember.

Examples in sentences:

Which way goes to the mall?

What time is it?

Whose duty time is it?

Possessive Adjectives

Possessive adjectives denote the ownership of something. Common possessive adjectives are:

My, your, our, its, his, her, their

Examples in sentences:

My daily routine is pretty simple.

Your shoelaces are loose.

Cat is licking its paws.

They are doing their work.

Emphasizing Adjectives

Emphasizing adjectives are used to put emphasis in sentences. Look at the example below.

This is the very book I want.

Sarah saw the robbery with her own eyes.

In the examples above, very and own are added to put additional emphasis.

Exclamatory Adjective

Exclamatory adjective is used to exclaim excitement, fear and other extreme feelings. There is only one word which is usually used to exclaim i.e. what.

Examples of adjective in sentences:

What crap!

What a spectacular view!

What foolishness!

One of the most important components of a sentence is the adjective. This part of speech is so common that people use it almost automatically, both in speech and in writing. For you to understand the concept of adjectives better this article will answer the following questions:

- What is an adjective?

- What are the functions of adjectives?

- What are the different kinds of adjectives?

- What are the degrees of adjectives?

Aside from answering the basic questions and defining the related terms, various examples will also be included in this short write-up.

What is an Adjective and its Functions?

An adjective is a part of speech which describes, identifies, or quantifies a noun or a pronoun. So basically, the main function of an adjective is to modify a noun or a pronoun so that it will become more specific and interesting. Instead of just one word, a group of words with a subject and a verb, can also function as an adjective. When this happens, the group of words is called an adjective clause.

For example:

- For example: My brother, who is much older than I am, is an astronaut.

In the example above, the underlined clause modifies the noun ”brother.” But what if the group of words doesn’t have a subject and a verb? What do you think the resulting group of words will be called?

If you think it’s called an adjective phrase, you are right. As you might recall, phrases and clauses are both groups of words and the main difference is that clauses have subjects and verbs, while phrases don’t.

- For example: She is prettier than you.

What are the Different Kinds of Adjectives?

Now that you already know the answer to the question, “What is an adjective?” you should know that not all adjectives are the same. They modify nouns and pronouns differently, and just like the other parts of speech, there are different kinds of adjectives. These are:

1. Descriptive Adjectives

Among the different kinds of adjectives, descriptive adjectives are probably the most common ones. They simply say something about the quality or the kind of the noun or pronoun they’re referring to.

Examples:

- Erika is witty.

- She is tired.

- Adrian’s reflexes are amazing.

2. Adjectives of Number or Adjectives of Quantity

As the name suggests, this kind of adjective answers the question, “How many?” or “How much?”

Examples:

- Twenty-one students failed the exam.

- The plants need more water.

3. Demonstrative Adjectives

Demonstrative adjectives point out pronouns and nouns, and always come before the words they are referring to.

Examples:

- I used to buy this kind of shirts.

- When the old man tripped over that wire, he dropped a whole bag of groceries.

4. Possessive Adjectives

Obviously, this kind of adjectives shows ownership or possession. Aside from that, possessive adjectives always come before the noun.

Examples:

- I can’t answer my seatwork because I don’t have a calculator.

- Trisha sold his dog.

5. Interrogative Adjectives

Interrogative adjectives ask questions and are always followed by a noun.

Examples:

- What movie are you watching?

- Which plants should be placed over here?

What are the Degrees of Adjectives?

There are only three degrees or levels of adjectives (also known as degrees of comparison) namely, positive, comparative, and superlative. When you talk about or describe only a single person, place, or thing, you should use the positive degree.

Examples:

- She is a beautiful lady.

- It was a memorable trip.

If on the other hand, you are comparing two persons, places, or things, it is appropriate to use the comparative degree of the word. Normally, you will need to add “-er” to transform the word into its comparative form or add the word “more.” Also, the word “than” should be added after the adjective in the comparative degree.

Examples:

- This swimming pool is bigger than that one.

- Ashley is more intelligent than Aldrin.

*Note: For words ending in “y,” you should first change the “y” into “i,” and then add “-er” (e.g., lovely-lovelier; pretty- prettier; tasty- tastier)

Lastly, if you are comparing more than two things, the superlative form of the adjectives should be used and the word “the” should be added before the adjective. In order to transform the adjective into its superlative form, you just have to add the suffix “-est” or the word “most.”

Examples:

- That is by far, the tallest tree I have ever seen in my entire life.

- This is the most crucial match of the season.

*Note: For words ending in “y,” you should first change the “y” into “i,” and then add “-est” (e.g., lovely-loveliest; pretty- prettiest; tasty- tastiest)

Final Thoughts

This article entitled “Basic Grammar: What is an Adjective?” can be very helpful for beginners who want to improve their grammar skills and ace the English subject. If you really have a deep understanding of what is an adjective, you will surely be able to apply this concept to your compositions properly. Just remember that although adjectives seem a little trivial, an effective use of this part of speech can actually strengthen your writing.