From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

High frequency sight words (also known simply as sight words) are commonly used words that young children are encouraged to memorize as a whole by sight, so that they can automatically recognize these words in print without having to use any strategies to decode.[1] Sight words were introduced after whole language (a similar method) fell out of favor with the education establishment.[2]

The term sight words is often confused with sight vocabulary, which is defined as each person’s own vocabulary that the person recognizes from memory without the need to decode for understanding.[3][1]

However, some researchers say that two of the most significant problems with sight words are: (1) memorizing sight words is labour intensive, requiring on average about 35 trials per word,[4] and (2) teachers who withhold phonics instruction and instead rely on teaching sight words are making it harder for children to «gain basic word-recognition skills» that are critically needed by the end of grade three and can be used over a lifetime of reading.[5]

Rationale[edit]

Sight words account for a large percentage (up to 75%) of the words used in beginning children’s print materials.[6][7] The advantage for children being able to recognize sight words automatically is that a beginning reader will be able to identify the majority of words in a beginning text before they even attempt to read it; therefore, allowing the child to concentrate on meaning and comprehension as they read without having to stop and decode every single word.[6] Advocates of whole-word instruction believe that being able to recognize a large number of sight words gives students a better start to learning to read.

Recognizing sight words automatically is said to be advantageous for beginning readers because many of these words have unusual spelling patterns, cannot be sounded out using basic phonics knowledge and cannot be represented using pictures.[8] For example, the word «was» does not follow a usual spelling pattern, as the middle letter «a» makes an /ɒ~ʌ/ sound and the final letter «s» makes a /z/ sound, nor can the word be associated with a picture clue since it denotes an abstract state (existence). Another example, is the word «said», it breaks the phonetic rule of ai normally makes the long a sound, ay. In this word it makes the short e sound of eh.[9] The word «said» is pronounced as /s/ /e/ /d/. The word «has» also breaks the phonetic rule of s normally making the sss sound, in this word the s makes the z sound, /z/.» The word is then pronounced /h/ /a/ /z/.[9]

However, a 2017 study in England compared teaching with phonics vs. teaching whole written words and concluded that phonics is more effective, saying «our findings suggest that interventions aiming to improve the accuracy of reading aloud and/or comprehension in the early stages of learning should focus on the systematicities present in print-to-sound relationships, rather than attempting to teach direct access to the meanings of whole written words».[10]

Most advocates of sight-words believe children should memorize the words. However, some educators say a more efficient method is to teach them by using an explicit phonics approach, perhaps by using a tool such as Elkonin boxes. As a result, the words form part of the students sight vocabulary, are readily accessible and aid in learning other words containing similar sounds.[11][12]

Other phonics advocates, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI-USA), the Departments of Education in England, and the State of Victoria in Australia, recommend that teachers first begin by teaching children the frequent sounds and the simple spellings, then introduce the less frequent sounds and more complex spellings later (e.g. the sounds /s/ and /t/ before /v/ and /w/; and the spellings cake before eight and cat before duck).[13][14][15][16] The following are samples of the lists that are available on the CCSSI-USA site:[17]

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Consonants) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /m/ | mitt, comb, hymn | m, mb, mn |

| /t/ | tickle, mitt, sipped | t, tt, ed |

| /n/ | nice, knight, gnat | n, kn, gn |

| /k/ | cup, kite, duck, chorus, folk, quiet | k, c, ck, ch, lk, q |

| /f/ | fluff, sphere, tough, calf | f, ff, gh, ph, lf |

| /s/ | sit, pass, science, psychic | s, ss, sc, ps |

| /z/ | zoo, jazz, nose, as, xylophone | z, zz, se, s, x |

| /sh/ | shoe, mission, sure, charade, precious, notion, mission, special | sh, ss, s, ch, sc, ti, si, ci |

| /zh/ | measure, azure | s, z |

| /r/ | reach, wrap, her, fur, stir | r, wr, er/ur/ir |

| /h/ | house, whole | h, wh |

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Vowels) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /ā/ | make, rain, play, great, baby, eight, vein, they | a_e, ai, ay, ea, -y, eigh, ei, ey |

| /ē/ | see, these, me, eat, key, happy, chief, either | ee, e_e, -e, ea, ey, -y, ie, ei |

| /ī/ | time, pie, cry, right, rifle | i_e, ie, -y, igh, -I |

| /ō/ | vote, boat, toe, snow, open | o_e, oa, oe, ow, o- |

| /ū/ | use, few, cute | u, ew, u_e |

| /ă/ | cat | a |

| /ĕ/ | bed, breath | e, ea |

| /ĭ/ | sit, gym | i, y |

| /ŏ/ | fox, swap, palm | o, (w)a, al |

| /ŭ/ | cup, cover, flood, tough | u, o, oo, ou |

| /aw/ | saw, pause, call, water, bought | aw, au, al, (w)a, ough |

| /er/ | her, fur, sir | er, ur, ir |

Word lists[edit]

A number of sight word lists have been compiled and published; among the most popular are the Dolch sight words[18] (first published in 1936) and the 1000 Instant Word list prepared in 1979 by Edward Fry, professor of Education and Director of the Reading Center at Rutgers University and Loyola University in Los Angeles.[19][20][21][22] Many commercial products are also available. These lists have similar attributes, as they all aim to divide words into levels which are prioritized and introduced to children according to frequency of appearance in beginning readers’ texts. Although many of the lists have overlapping content, the order of frequency of sight words varies and can be disputed, as they depend on contexts such as geographical location, empirical data, samples used, and year of publication.[23]

Criticism[edit]

Research shows that the alphabetic principle is seen as «the primary driver» of development of all aspects of printed word recognition including phonic rules and sight vocabulary.»[24] In addition, the use of sight words as a reading instructional strategy is not consistent with the dual route theory as it involves out-of-context memorization rather than the development of phonological skills.[25] Instead, it is suggested that children first learn to identify individual letter-sound correspondences before blending and segmenting letter combinations.[26][27]

Proponents of systematic phonics and synthetic phonics argue that children must first learn to associate the sounds of their language with the letter(s) that are used to represent them, and then to blends those sounds into words, and that children should never memorize words as visual designs.[28] Using sight words as a method of teaching reading in English is seen as being at odds with the alphabetic principle and treating English as though it was a logographic language (e.g. Chinese or Japanese).[29]

Some notable researchers have clearly stated their disapproval of whole language and whole-word teaching. In his 2009 book, Reading in the brain, French cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene wrote, «cognitive psychology directly refutes any notion of teaching via a ‘global’ or ‘whole language’ method.» He goes on to talk about «the myth of whole-word reading», saying it has been refuted by recent experiments. «We do not recognize a printed word through a holistic grasping of its contours, because our brain breaks it down into letters and graphemes.»[30] Another cognitive neuroscientist, Mark Seidenberg, says that learning to sound-out atypical words such as have (/h/-/a/-/v/) helps the student to read other words such as had, has, having, hive, haven’t, etc. because of the sounds they have in common.[31]

See also[edit]

- Dolch word list

- Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud

- Fry readability formula

- Learning to read

- Literacy

- Most common words in English

- Phonics

- Reading comprehension

- Reading education in the United States

- Reading (process)

- Subvocalization

- Teaching reading: whole language and phonics

- Whole language

- Writing system

References[edit]

- ^ a b «What Are Sight Words?». WeAreTeachers. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Ravitch, Diane. (2007). EdSpeak: A Glossary of Education Terms, Phrases, Buzzwords, and Jargon. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, ISBN 1416605754.

- ^ Rapp, S. (1999-09-29). Recognizing words on sight; activity. The Baltimore Sun

- ^ Murray, Bruce; McIlwain, Jane (2019). «How do beginners learn to read irregular words as sight words». Journal of Research in Reading. 42 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1111/1467-9817.12250. ISSN 0141-0423. S2CID 150055551.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of sight. New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-5416-1715-5.

- ^ a b Kear, D. J., & Gladhart, M. A. (1983). «Comparative Study to Identify High-Frequency Words in Printed Materials». Perceptual and Motor Skills. 57 (3): 807–810. doi:10.2466/pms.1983.57.3.807. S2CID 144675331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Teaching Sight Words as a Part of Comprehensive Reading Instruction, Iowa reading research centre, 2018-06-12».

- ^ «Phonological Ability», The SAGE Encyclopedia of Contemporary Early Childhood Education, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2016, doi:10.4135/9781483340333.n296, ISBN 9781483340357

- ^ a b «Sight Words». www.thephonicspage.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Taylor, J. S. H.; Davis, Matthew H.; Rastle, Kathleen (2017). «Comparing and Validating Methods of Reading Instruction Using Behavioural and Neural Findings in an Artificial Orthography» (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, volume 146, No. 6, 826–858. 146 (6): 826–858. doi:10.1037/xge0000301. PMC 5458780. PMID 28425742.

- ^ «Sight Words: An Evidence-Based Literacy Strategy, Understood.org».

- ^ «A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words, reading rockets.org». 6 June 2019.

- ^ «Complete report — National Reading Panel, England» (PDF).

- ^ «Sample phonics lessons, The State Government of Victoria».

- ^ «Foundation skills, The State Government of Victoria, AU».

- ^ «English Appendix 1: Spelling, Government of England» (PDF).

- ^ «Common Core Standards, Appendix A, USA» (PDF).

- ^ «Dolch Words 220, Utah Education Network in partnership with the Utah State Board of Education and Utah System of Higher Education» (PDF).

- ^ Edward Fry (1979). 1000 Instant Words: The Most Common Words for Teaching Reading, Writing, and Spelling. ISBN 0809208806.

- ^ «McGraw-Hill Education Acknowledges Enduring Contributions of Reading and Language Arts Scholar, Author and Innovator Ed Fry, McGraw-Hill Education, Sep 15, 2010».

- ^ «Edward B. Fry, PH.D, Published in Los Angeles Times on Sep. 12, 2010». Legacy.com.

- ^ «Fry Instant Words, UTAH EDUCATION NETWORK».

- ^ Otto, W. & cester, R. (1972). «Sight words for beginning readers». The Journal of Educational Research. 65 (10): 435–443. doi:10.1080/00220671.1972.10884372. JSTOR /27536333.

- ^ «Independent Review of the Primary Curriculum: Final Report, page 87» (PDF).

- ^ Ehri, Linnea C. (2017). «Reconceptualizing the Development of Sight Word Reading and Its Relationship to Recoding». Reading Acquisition. London: Routledge. pp. 107–143. ISBN 9781351236898.

- ^ Literacy teaching guide : phonics. New South Wales. Department of Education and Training. [Sydney, N.S.W.]: New South Wales Dept. of Education and Training. 2009. ISBN 9780731386093. OCLC 590631697.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Findings and Determinations of the National Reading Panel by Topic Areas

- ^ McGuinness, Diane (1997). Why Our Children Can’t Read. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0684831619.

- ^ Gatto, John Taylor (2006). «Eyless in Gaza». The Underground History of American Education. Oxford, NY: The Oxford Village Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0945700040.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010-10-26). Reading in the brain. Penquin Books. pp. 222–228. ISBN 9780143118053.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of light. pp. 143–144=author=Mark Seidenberg. ISBN 9780465080656.

When you’re a new teacher, the number of buzzwords that you have to master seems overwhelming at times. You’ve probably heard about many concepts, but you may not be entirely sure what they are or how to use them in your classroom. For example, new teacher Katy B. asks, “This seems like a really basic question, but what are sight words, and where do I find them?” No worries, Katy. We have you covered!

What’s the difference between sight words and high-frequency words?

Oftentimes we use the terms sight words and high-frequency words interchangeably. Opinions differ, but our research shows that there is a difference. High-frequency words are words that are most commonly found in written language. Although some fit standard phonetic patterns, some do not. Sight words are a subset of high-frequency words that do not fit standard phonetic patterns and are therefore not easily decoded.

We use both types of words consistently in spoken and written language, and they also appear in books, including textbooks, and stories. Once students learn to quickly recognize these words, reading comes more easily.

What are sight words and how can I teach my students to memorize them?

Sight words are words like come, does, or who that do not follow the rules of spelling or the six types of syllables. Decoding these words can be very difficult for young learners. The common practice has been to teach students to memorize these words as a whole, by sight, so that they can recognize them immediately (within three seconds) and read them without having to use decoding skills.

Can I teach sight words using the science of reading?

On the other hand, recent findings based on the science of reading suggests we can use strategies beyond rote memorization. According to the the science of reading, it is possible to sound out many sight words because they have recognizable patterns. Literacy specialist Susan Jones, a proponent of using the science of reading to teach sight words, recommends a method called phoneme-grapheme mapping where students first map out the sounds they hear in a word and then add graphemes (letters) they hear for each sound.

How else can I teach sight words?

There are many fun and engaging ways to teach sight words. Dozens of books on the subject have been published, including the much-revered Comprehensive Phonics, Spelling, and Word Study Guide by Fountas & Pinnell. Also, resources like games, manipulatives, and flash cards are readily available online and in stores. To help get you started, check out these Creative and Simple Sight Word Activities for the Classroom. Also, check out Susan Jones Teaching for three science-of-reading-based ideas and more.

Where do I find sight word lists?

Two of the most popular sources are the Dolch High Frequency Words list and the Fry High Frequency Words list.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Dr. Edward Dolch developed his word list, used for pre-K through third grade, by studying the most frequently occurring words in the children’s books of that era. The list has 200 “service words” and also 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch word list comprises 80 percent of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50 percent of the words found in writing for adults.

Dr. Edward Fry developed an expanded word list for grades 1–10 in the 1950s (updated in 1980), based on the most common words that appear in reading materials used in grades 3–9. The Fry list contains the most common 1,000 words in the English language. The Fry words include 90 percent of the words found in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

Looking for more sight word activities? Check out 20 Fun Phonics Activities and Games for Early Readers.

Want more articles like this? Be sure to sign up for our newsletters.

If you’ve been teaching reading for a while, you’ve undoubtedly come across the term sight words, and you probably have some questions about them. Should you teach sight words? What’s the best way to approach sight words? Is it bad to use a curriculum that teaches sight words?

In fact, a common question we get is, “Do you teach sight words in the All About Reading program? ” But before we jump into the details, let’s be sure we’re talking about the same definition for the term sight words.

Our Working Definition of Sight Word

At its most basic–and this is what we mean when we talk about sight words–a sight word is a word that can be read instantly, without conscious attention.

For example, if you see the word peanut and recognize it instantly, peanut is a sight word for you. You just see the word and can read it right away without having to sound it out. In fact, if you are a fluent reader, chances are you don’t need to stop to decode words as you read this blog post because every word in this post is a sight word for you.

But there are three other commonly used definitions for sight words that you should be aware of:

- Irregular words that can’t be decoded using phonics and must be memorized, such as of, could, and said.

- The “whole word” or “look-say” approach to teaching reading, also known as the “sight word approach.” This approach is the opposite of phonics, and words are memorized as a whole.

- Words that appear on high-frequency word lists such as the popular Dolch Sight Word and Fry’s Instant Word lists. (Many educators believe that the words on these lists must be learned through rote memorization, but we bust that myth in this video.)

So now you can see why sight words can cause so much angst! Educators have conflicting ideas about sight words and how to teach them, and in large part that stems from having different definitions for what sight words are.

But you are in safe territory here.

In this article, you’ll find out how to minimize the number of sight words that your child needs to memorize, while maximizing his ability to successfully master these words.

How Fast Is “Instant”?

Now that we’ve settled on the definition for sight words as “any words that can be read instantly, without conscious attention,” that may lead some people to wonder how fast is “instant”? And that’s a great question!

Basically, we want kids to see a word and be unable to not read it. Even before they’ve realized that they are looking at the word, they’ve unconsciously read it.

Here’s a demonstration of what I mean.

(Download this PDF if you want to try this experiment with your family and friends!)

As explained in the short video above, the Stroop effect1 shows that word recognition can be even more automatic than something as basic as color recognition.

So that’s what we mean by “instant.”

We want children to develop automaticity when reading, so they don’t even have to think about decoding words—they just automatically know the words. Ideally, we want reading to become as effortless and unconscious as breathing.

But what about words that aren’t as easily decoded? How should those words be taught?

Some Words Need to Be Learned Through Rote Memorization

The vast majority of words don’t need to be taught by rote memorization. Even the Dolch Sight Word list is mostly decodable (video). But there are some words that do need to be memorized.

Some programs call these “Red Words,” “Outlaw Words,” “Sight Words,” or “Watch-Out” words. In All About Reading, we call them Leap Words. Generally, these are high-frequency words that either don’t follow the normal phonetic patterns or contain phonograms that students haven’t practiced yet. Students “leap ahead” to learn these words as sight words.

Here’s an example of two flashcards used to practice the Leap Words could and again. In the word could, the L isn’t pronounced. In the word again, the AI says /ĕ/, which isn’t one of its typical sounds. The frog graphic acts as a visual reminder that the words are being treated as sight words that need to be memorized.

Leap Words comprise a small percentage of words taught. For example, out of the 200 words taught in All About Reading Level 1, only 11 are Leap Words.

Several techniques are used to help your student remember the Leap Words:

- Leap Word Cards are kept behind the Review divider in your student’s Reading Review Box until your student has achieved instant recognition of the word.

- Leap Words frequently appear on the Practice Sheets.

- Leap Words are used frequently in the decodable readers.

- If a Leap Word causes your student trouble, have your student use a light-colored crayon to circle the part of the word that doesn’t say what your student expects it to say.

- Help your student see that Leap Words generally have just one or two letters that are troublesome, while the rest of the letters say their regular sounds and follow normal patterns.

For typical students who do not struggle with reading, very little practice is needed to move a word into long-term memory. They may encounter the word just one to five times, and never have to sound it out again.

On the other hand, a struggling reader may need up to thirty exposures to a word before it becomes part of the child’s sight word vocabulary. So be patient and give your child the amount of practice she needs to develop a large sight word vocabulary.

Here Are 5 More Ways to Increase Your Child’s Sight Word Vocabulary

These five methods increase the number of times your child encounters a word, helping move the word into long-term memory for instant recall:

- Make use of interesting games and activities (such as Over Easy, Hatch the Turtles, and Pack Your Suitcase).

- Have your child read decodable books.

- Encourage your child to “sound out” phonetically-regular words.

- Use sentence dictation to encourage extra practice.

- Review Word Cards frequently until they are mastered.

The Bottom Line on Teaching Sight Words

When it comes to teaching sight words, here’s what you need to keep in mind:

- The goal of teaching sight words is to allow your child to read easily and fluently, without conscious attention.

- Some words—we call them Leap Words—can’t be decoded as easily and must be learned through rote memorization.

- Increasing the number of times a child encounters a word helps move the word into the child’s long-term memory.

Are you looking for a reading program that doesn’t involve memorizing hundreds of sight words via rote memorization? All About Reading is a research-based program that walks you through all the steps to help your child achieve instant recall. And if you ever need a hand, we’re here to help.

What’s your take on teaching sight words? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

___________________________________

1Stroop, J.R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643-662.

Here, we will be discussing “What are Sight Words” in detail along with the sight word definition, examples, properties and their importance. Needless to say, Sight Words for Kids are extremely beneficial to phrase meaningful sentences for effective communication. These words will enhance your child’s comprehension and other important skills required for conversing and interpreting information appropriately. To enhance their language skills, you can explore common sight words for kids. At the beginning of their learning process, these sight words will enable them to communicate with others efficiently.

To make them practice sight word sentences, start with short and simple sentences. For example, I am going to Market, I like to eat ice cream, This is my toy, etc. These sight words for kids will enable them to grasp the sentences quickly with complete understanding of the communication that they want to convey. The first sight words for kids will include It, Is, In, The, etc so that they can start using these frequently used words in the sentences. Apart from recognition, they should also know the sight words definition so that they will know the meaning of the words that they are using while communicating. At the beginning, explore preschool school sight words for kids.

Sight Words Definition For Kids

If you are wondering what sight words mean, we are here to help. Ever noticed that we come across some words more often than other words? What are these words called? The words that are frequently used in the sentences for meaningful communication. These words are known as Sight Words.

What’s a sight word? Sight words are basically the words that appear more frequently than other words in our reading and writing materials. These words occur so often that the learners are expected to recognize them easily and quickly. Sight words are not easily represented by images or graphics. They are not often linked to any particular subject. That is why we find them repeatedly in various parts of texts, irrespective of the topic the texts are based on. Teaching these words for kids will enable them to become proficient readers.

Sight word recognition is crucial to becoming a fluent and persuasive reader. The more you know about the commonly used words, the better you become at reading. The first sight words are the ones that even kids are expected to be familiar with. They should be able to quickly recognize these words so that they can put in more effort to understand the meanings of other words that are actually used less often and thus, are tougher.

List Of Sight Words For Kids

| a | I | is | am | in | on |

| the | am | me | my | we | you |

| and | are | it | not | to | up |

| an | our | his | him | her | she |

| at | he | do | did | they | but |

| are | them | with | if | of | say |

| what | why | where | how | when | who |

| has | have | had | look | so | then |

| from | yes | no | please | come | go |

| up | down | out | does | can | could |

| thank | some | any | by | there | than |

| always | never | around | been | be | best |

| sit | their | help | big | may | here |

| said | give | know | eat | us | very |

| about | date | nice | much | also | many |

Properties Of Sight Words

Here are certain characteristics of sight words in English language as mentioned below:

- Sight words are high-frequency words and thus appear highly often in text or speeches.

- Most of the sight words are words that provide a sense to a sentence and the text as a whole.

- They are majorly helping verbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, adverbs and adjectives.

- Sight words are not very easy to represent through images or videos. (How can one explain ‘the’ or ‘it’ or ‘am’ through pictures!)

- Sight words are often phonetically quite random. You won’t find sight words very consistent in terms of the way they are pronounced. Some of them go in line with the usual rules of phonetics while others don’t.

- These are basic sight words that can only be recognized and memorized.

- Sight words give meanings to the information that you want to convey.

- There is an increase in the fluency of the language by using sight words appropriately.

- Though the words seemed to be small but have more weightage in terms of meaning.

For example, the pronunciation of sight words ‘in’ and ‘it’ are similar – both having a short ‘i’ sound in their pronunciation. But, the pronunciation of the sight words ‘so’ and ‘to’ are way different – while ‘so’ has an ‘o’ sound in its pronunciation, ‘to’ has ‘oo’ sound. That is the reason why sight words are also referred to as trick words. Did you know that sight words are also known as popcorn words? This is because sight words pop-up so very often in texts and speech.

Few Examples of Sight Words

Some of the most basic sight words are the, to, and, do, did, a, an, in, is, etc. The set of sight words that occur even more frequently are called the first sight words or the beginning sight words. Examples of first sight words can include a, an, the, is, in, on, it, me, my, not, to, up, we, you, etc. When children are exposed to sight words, they are often initially introduced to the first sight words as these are simple and most used. Some of the beginning sight words used in sentences are mentioned below:

- This is part of a plant.

- I am going to the beach.

- This is my friend Sam.

- I have pet dog

- Do you want a pencil?

- This is a large animal.

- I went to school in a bus

- The sun is out.

- She is playing with dolls.

- The monkey is here.

- Can I take this pen?

- The rose is red.

- He is cutting nail.

- My mother is cooking.

- Can we go to the park?

- I like to eat apple pie?

- Is this your house?

- There are many butterflies in the garden.

- Do you like shrimp?

- Do you want to play scrabble?

- Where is your school?

- I like to play with my dogs.

- Can you sing a song?

- There is a lot of noise here.

- She ate all the oranges.

Why are Sight Words Important?

Some of the benefits of learning sight words are mentioned below:

- Build Vocabulary: As a parent, you must want your child to develop a rich vocabulary.

The journey of knowing lots of words starts with getting acquainted with a few words. Sight words are the first set of words that children would come across very often and thus, should become a part of their vocabulary soon. - Improves reading: The basic idea of categorizing some words as sight words is that these become incorporated in an individual’s reading and writing in such a way that he/she doesn’t have to stop and think about its meaning or pronunciation anymore.

Sight words become a part and parcel of communication for young children as well, thus, making them more fluent readers. - Familiarises with pronunciation: Above everything, sight words are basically words!

When kids come across them so frequently, eventually they get familiarized with how these words are to be pronounced. - Refines writing skills: Most of the things that improve reading skills would automatically have a positive effect on writing proficiency. Essay writing, sentence formation, etc. would obviously need usage of sight words. If kids are thorough with sight words, they will be able to write better.

- Introduces them to English phonetics: As discussed, sight words have irregular phonetics. When kids are made aware of several sight words, their spellings and pronunciation, they get to know that there can be irregularities in terms of spelling and pronunciation of words. Thus, they get an insight into English phonetics.

- Helps in communication: In the formative years of children, they need to grasp a lot of information on different things. This needs to be done through communication. Sight words boost kids’ comprehension of information that is imparted to them.

- Builds confidence among kids: While using appropriate sight words in sentences, there will be clarity in the information that is being conveyed. Eventually, this will build confidence among kids to make effective use of sight words in communication.

- Provides meaning to the sentences: Sight words will help in giving meaning to the sentence that is being communicated. Without use of appropriate words, the information can be miscommunicated or misinterpreted. Here, sight words play an important role in making meaningful sentences.

We hope that this article will help you understand the meaning of sight words, examples, recognition of sight words in a sentence, properties and their importance in linguistic comprehension.

Apart from the above, you may also want to explore Kindergarten Sight Words, Preschool Sight Words, First Grade Sight Words, 2nd Grade Sight Words, 3rd Grade Sight Words and Color by Sight Words.

Frequently Asked Questions on What are Sight Words?

What are sight words?

Sight words are those words that are frequently used in sentence formation and in text or speeches. As mentioned, these words are frequently used and kids learn them easily and quickly for making meaningful sentences. Moreover, these words are not depicted in images or visual representations.

What are some of the examples of sight words?

Some of the examples of sight words are am, in, the, a, I, us, in, on, me, then, when, where, here, there, these, this, their, always, around, never, been, big, be, nice, about, etc.

What are the properties of the sight words?

The properties of sight words are that these words makes the sentence meaningful and are high frequency words. They are mostly, prepositions, adverbs, verbs, pronouns and conjunctions. These words also improve and increase the fluency of the language and vocabulary.

When you hear the words “sight word instruction”, what do you think of? I can honestly say that my idea of what “sight word instruction” means and looks like has drastically changed over the years. In fact, my definition of “sight words” has even changed.

Often the term is used interchangeably to mean a few things: high-frequency words, irregular words, and words that students recognize on sight.

I used to think of sight words as words that couldn’t be sounded out and needed to be memorized. I also thought of them as words that needed to be memorized as a whole. I used the flash card method mostly, with the belief that if my students saw these words enough times, they would memorize them. This turned out to be true for some of my students. However, it certainly was not the case with many of my students. I started to look into why. I eventually learned that the research points to more effective methods of teaching “sight words”.

What are Sight Words?

Now I define sight words as words that can be read instantly and effortlessly (“on sight”).

- High-frequency words are words that are the most occurring in print. Because they are words that our students will most likely encounter in a text, we often work hard to help these become “sight words”.

- This includes words that are fully decodable and words that have some irregularities.

- Technically, the goal is to make every word a “sight word” but in the beginning, it is helpful for students to know these particular high-frequency words since they account for 75% of words in print.

- The fancy word for “sight word” is orthographic lexicon, or the words that a reader can read automatically and without any effort.

There are two main lists that most teachers pull from: the Dolch and Fry Lists, that include the most frequently occurring words in children’s texts. Both of these lists were originally created to use the “look-say” method (essentially whole language approach).

We now have more research to draw from that tells us reading outcomes are stronger when beginning readers are taught to decode words using sound-symbol associations, rather than rote memorization. That goes for all words, including regular and irregular high-frequency words.

Why is Teaching Sight Words Important?

Knowing that these high-frequency words appear more often in children’s texts means we should spend a little more time on these words so that our students can read them automatically and with little effort. Helping these high frequency words become “sight words” will begin to improve their fluency because automatic word recognition is the first step toward fluency (followed by developing prosody, rate, expressing, and appropriate phrasing).

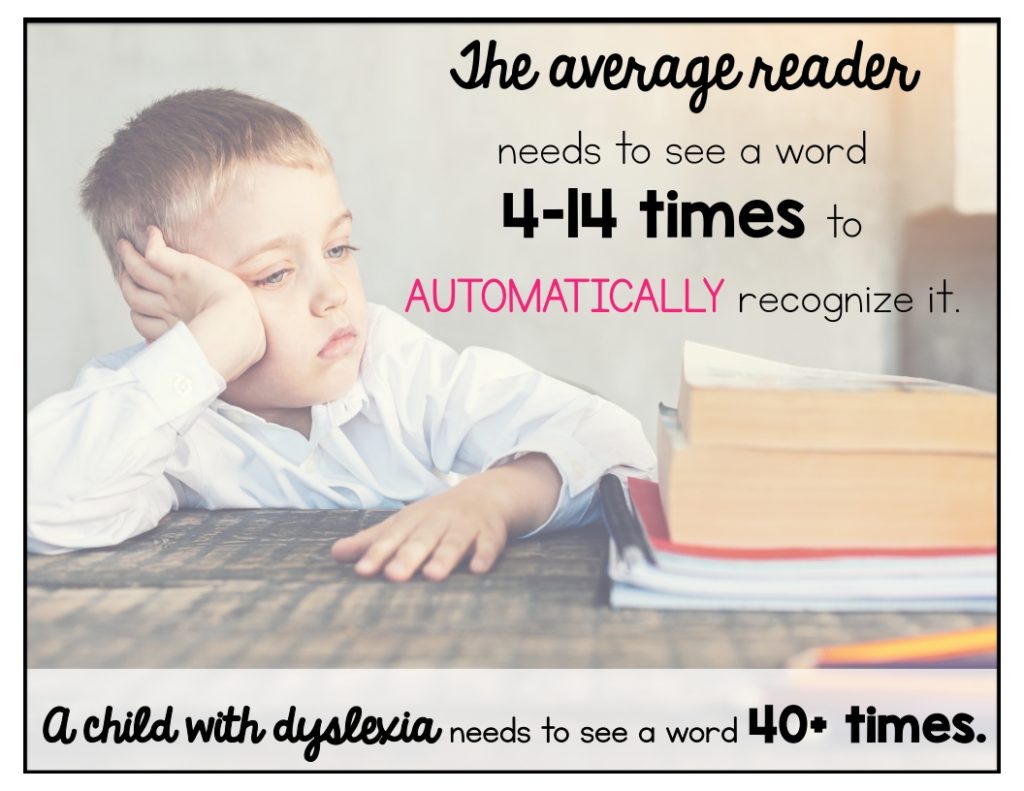

Even your average beginning reader needs to be exposed to a word several times in order to read it with automaticity. Students with dyslexia need SEVERAL more exposures to those words. We need to provide them with those opportunities to practice these words.

However, by second grade on, your typically developing readers are able to store a new word permanently in only one to four exposures (Bowey & Miller, 2007). The exact number for readers with dyslexia is not known, although I can tell from experience, it’s a lot more than that and it varies from student to student.

Some Facts about Sight Words

Another thing we need to get out of the way is the idea that most “sight words” (high-frequency words) are all irregular. I’m going to throw some facts out there:

- Many high-frequency words are decodable.

- The majority of irregular words actually only have only one irregular letter-sound relationship.

- Even though these words are irregular, they are still stored in our long-term memory using the same orthographic mapping process as regular words.

- Most of these irregular words have a history (etymology) and relatives that actually do explain the spelling.

How Do We Learn Sight Words?

How do our brains process and permanently store words into our sight memory? Orthographic mapping! According to David Kilpatrick, new readers map the phonemes (sounds) of words (that they already have in their phonological memory) to the sequence of the letters they see on the page. Once a word has been adequately mapped, it is there for quick, effortless retrieval.

Ortho means straight (correct, in order, sequence) and graph means writing. Together that makes correct writing.

We form connections between the pronunciation of a word (with the individual sounds) and the order of the printed letters. We are connecting sounds to sequence of letters. This connection is called “mapping”. Orthographic mapping allows our brains to permanently store words, so we can retrieve them automatically.

We need three things for this to happen:

- Automatic sound-symbol awareness

- Phoneme awareness

- Word study: helping students see the connections between letters and sounds

Here’s a tidbit I just learned: According to David Kilpatrick’s book Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, we actually do not memorize sight words using our visual memory. We use vision for input but not for storage. Instead, storage is orthographic, phonological (sound), and semantic (meaning). Mind blown, right? That means new words are not simply memorized just by seeing it over and over.

For more about orthographic mapping, click here.

Another study out of Stanford found that “beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the area of the brain best wired for reading. In other words, to develop reading skills, teaching students to sound out C-A-T sparks more optimal brain circuitry than instructing them to memorize the word cat.” This also debunks the idea that high-frequency words should be learned using the “look-see-learn” whole language method.

How to Teach Sight Words

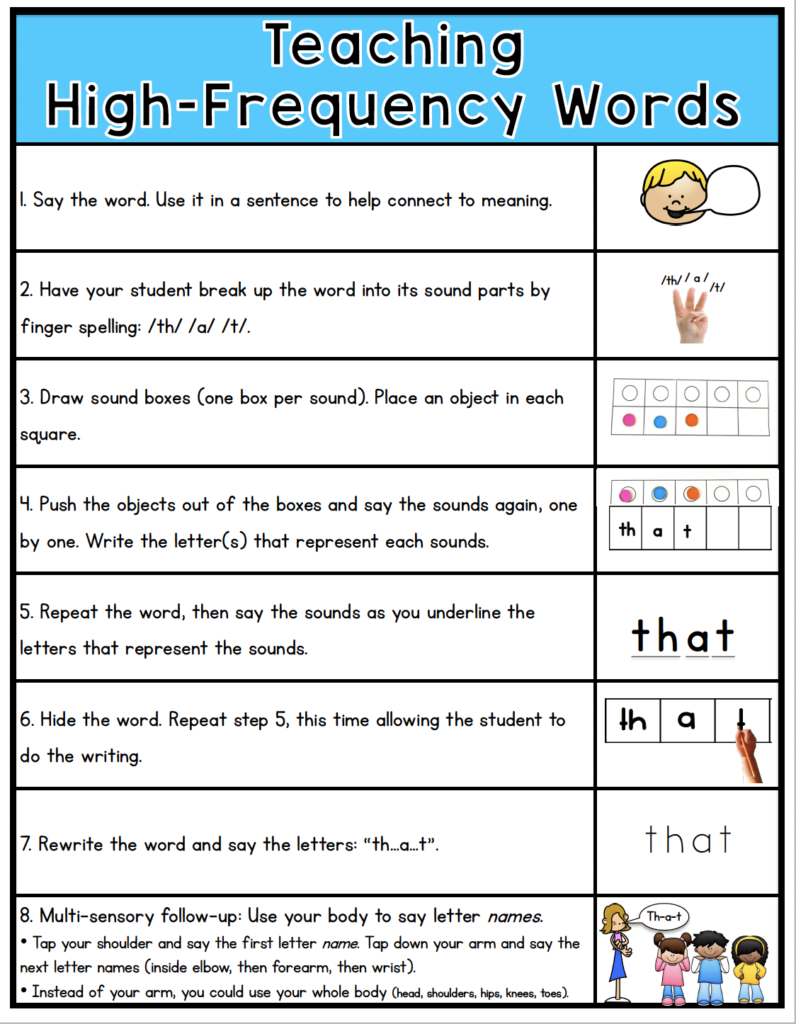

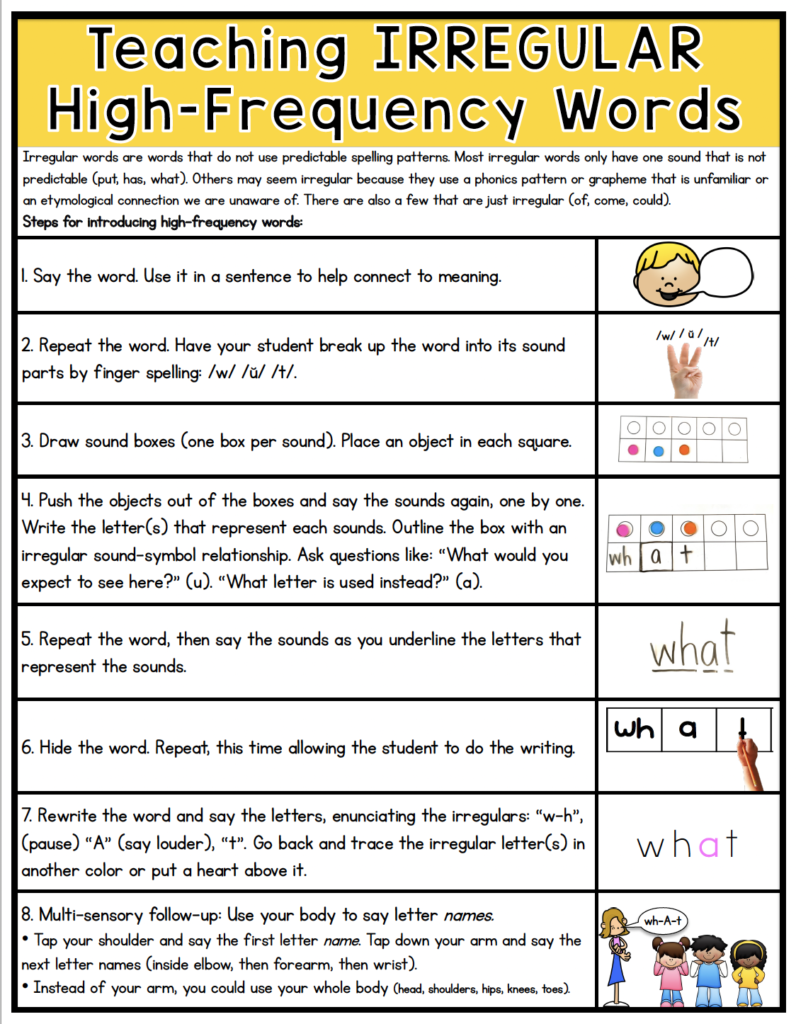

Now that I have a better understanding of how our brains learn new words, I’ve made some changes to how I approach sight words. Now, the first thing I do is introduce the word orally and explicitly teach the sound-symbol connections.

Step 1: Match the Sounds to the Correct Letters

Here are the steps to take;

- Introduce the word and show the student:

- Say the word.

- Write the word and show your students.

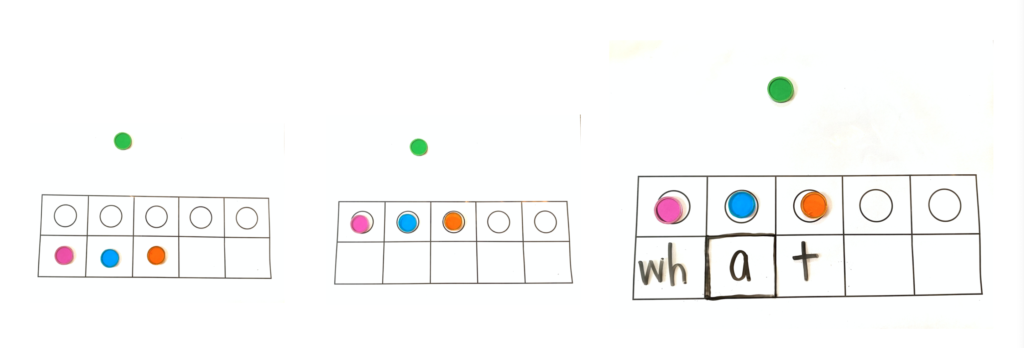

- Use your finger to tap under the letters as you break the word up into its sound parts. (For the word “what”, you would underline with your finger (or actual underline as shown below): <wh> as you say /w/, underline <a> as you say /u/ and <t> as you say /t/. Erase the word or move it away.

- Repeat the word

- Segment the word into its individual sounds.

- Draw dots, sound boxes, or use bingo chips to represent those sounds.

- Students will tap the sound boxes or slide the bingo chips as they say the sounds. For example: /w/ /u/ /t/.

- Discuss what letters you expect to see representing each sound.

- If there is a word that has an irregular sound-symbol relationship, I often outline that box in another color if I’m using sound boxes or use another color for the dot if I’m just making dots.

- Show the word you had written in the first step. Underline with your finger again the letters as you say each sound. Point out the unexpected sounds.

- Have your students write the letters that go with each sound in the sound boxes or above the dots.

Click HERE to download the printable below.

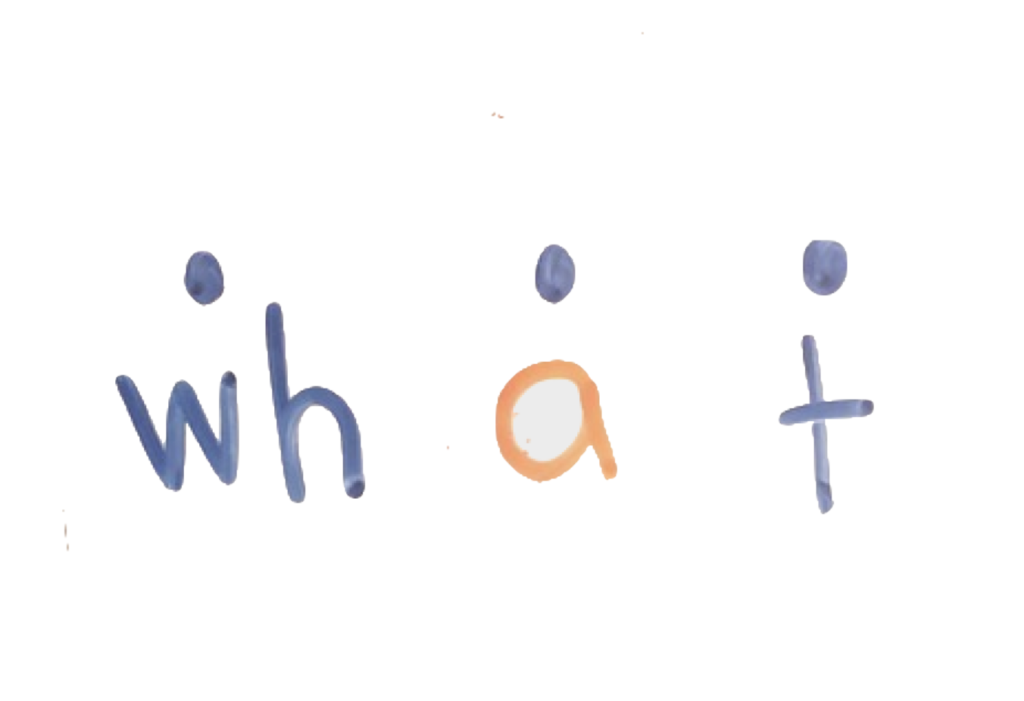

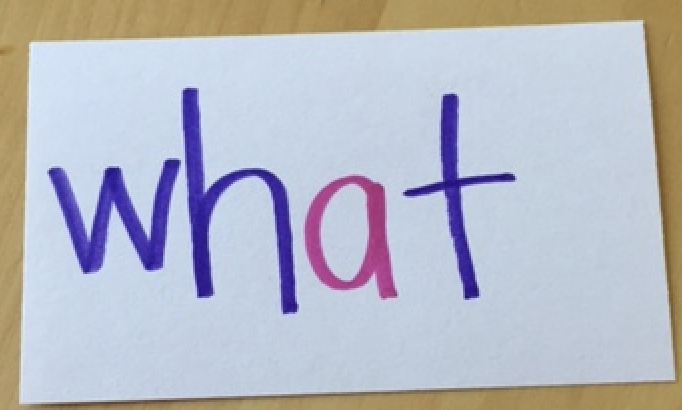

Highlight the “Irregular” or Unexpected Sound

This is another tip that I find very helpful. Somehow highlight the unexpected letter-sound relationship.

For example: Connect the sound /w/ with <wh>, /u/ with <a>, and /t/ with <t>. Then highlight, underline, or use another color for the letter <a>. You could also underline that letter.

Update: I have now learned of a method called “heart words” where people put a heart over the irregular sound-symbol relationship. When I originally wrote this post years ago, I had never heard of heart words, but I do love this idea!

Show your students the word with the highlighted “odd” or unexpected letter(s). Practice spelling the word as you did earlier (in the above tip.) This time enunciate the odd letter(s) vocally. “Wh-A-t” You could enunciate it with a louder voice or with an accent or with a funny voice- anything to get that letter to stick! Notice how I also said wh together. That is intentional because I want them to group those two letters since they are one grapheme representing the sound /w/.

A lot of times, there may actually be a reason for the unexpected sound-symbol connection. In this case, teach your student why that letter is used.

- For example, the word give and have end in the letter e. This makes our students think that it is not fully decodable. But actually, there is a reason for that e. Did you know an English word should not end in v? So that silent e has a purpose, just not one that they are used to. (The e is there to make sure the v isn’t the last letter.) Click here for more about the “rules” of spelling.

- In the word, around and about, the a says /uh/ which makes it trickier. Well, that is also a phonic thing called Schwa.

Step 2: Make it Multi-Sensory

This is nothing new but it’s always worth saying. Students need to see it, say it, write it, feel it, and hear it.

- Have students say the letters in the word as they trace the letters.

- Repeat. Say the word again.

- Have the student write the letters in the air AND on the table or a bumpy surface, saying the letters as they trace, repeating the whole word when they are done.

- After seeing and tracing the word, guide your student to try to take a “snapshot” of this word in their brain: Look at the word, say the letters, then close your eyes and try to see the word repeating the letters. I try to group letters together that go with sounds. For example, wh-A-t. I say the <wh> together because they make one sound together. I say the <a> louder because it is irregular.

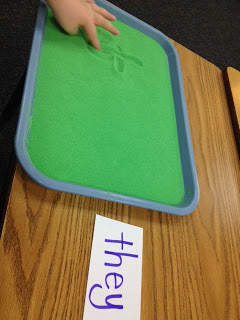

To spice it up, use sand and/or add glue to the flashcards to give them a bumpier feel. I often use these foam sheets with different textures for students to trace on. If you don’t have all of these extra things, that is okay. Truly, multi-sensory just means uses multiple senses. That means multisensory can just mean you say, see it, hear it, and write it.

A popular method that Orton-Gillingham tutors use is the Arm Tap.

- Begin at the shoulder.

- Say the first letters as you tap your right shoulder with your left hand.

- Move down your arm and say the other letters as you tap down your arm.

- Once you’ve said all the letters, repeat the word as you slide your hand from your shoulder to your wrist.

For example, the word what would go like this: “w-h” (tap shoulder), “a” (say louder since it’s an oddball and tap inside elbow), and “t” (tap wrist). I’m not sure if there is actual research to back this method up, but it is another way to practice the word and it’s always nice to get kids moving!

Step 3: Repeat, Repeat, Repeat

This one is obvious, I know! Remember how a child with dyslexia needs to see a word 40+ times? That’s a lot of exposures for that little one. My challenge is always, how do I do this without boring my kids to tears?! I think playing games is a great way to get that repetition.

Below are some easy games to play (with free editable templates):

Spin and Read: You can make your own spinner using a metal fastener. Write the words you are working on in the spinner. Make a chart like the one shown next to the spinner. Write each word in the first column. After you spin, read the word you land on. Then write that word in the second column in the correct row.

Roll a Word: Make a chart like the one shown below (with the dice). Instead of the dice that are shown, simply write 1-6. Write a sight word in each box. Roll the die. Read the words under the number that you landed on.

Tic Tac Toe: Write your sight words on a stack of index cards. Draw a card. Read the word. Write the word on the Tic-Tac-Toe board. (Each player will have a different color marker.) The next player does the same. Continue as you would with Tic-Tac-Toe, trying to be the first to get three in a row.

Word-O: Draw a 3×3 or 4×4 grid. Ahead of time, each player writes the same sight words on their own board in different spaces. Write those same words on index cards. Draw an index card. Read the word. Then cross out that word on your board. Continue until someone gets three/four in a row or black out.

As fun as games are, it’s also so impactful to give them plenty of practice to write the words again using the sound boxes, making the connection from sound to symbol and reviewing any irregular part.

Using Flash Cards Effectively

After we’ve done phoneme-grapheme mapping, then I bring out the flashcards for students to practice. One common mistake I see/hear about a lot is not letting kids sound out the word when they are using flash cards. Teachers will say, “If they don’t know the word automatically, I tell them the word and then skip it and come back to it because they need to know it automatically.” I was also one of these teachers.

But think about it. If they don’t know the word, then it’s just a random sequence of letters to them or a shape. And that shape looks like many of the other shapes on those flashcards. So, you telling them the word and then simply bringing it back again doesn’t help them at all. It’s that look-say method that we learned doesn’t actually work for many students. If they don’t know the word on sight yet, that means they don’t have it stored yet. Letting them sound out the word is okay because they are trying to use what they know to figure out the word. I recommend following the steps I’ve listed before.

When reviewing words using flashcards, follow these steps if a student doesn’t remember a word or says an incorrect word (going back to step one from above):

- Hold up the flash card.

- Say the word.

- Repeat the word, this time slower to enunciate each sound. As you say the sounds, underline the letter(s) that say each sound with your finger (even if it is irregular).

- If there is an irregularity, ask, “What sound do you hear here? What letters make that sound for this word?”

- Say the word again, sliding your finger under the whole word.

- Repeat the “arm tap” or just say the letters of the word again. For example: “they. <th> <EY>. they”.

- Give them the opportunity to write that word again, saying the letters.

Step 4: Spot it in Context

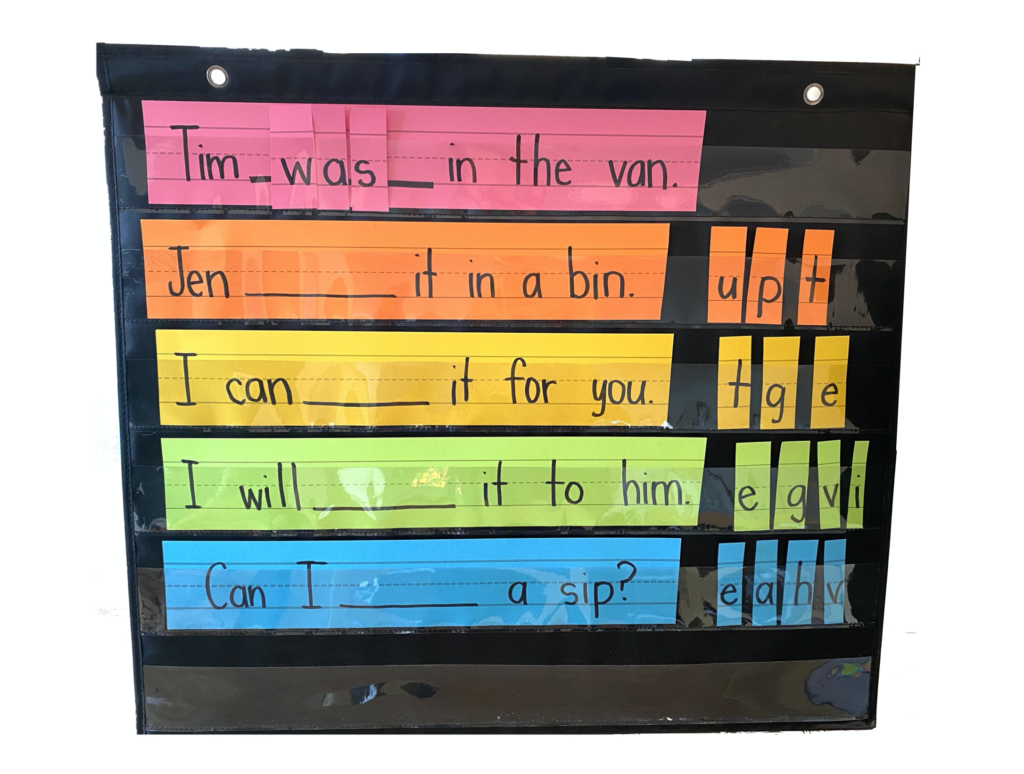

This should be done after a word has been introduced and you’ve done phoneme-grapheme mapping. Research shows we want to move away from using context to guess words. Guessing is not a decoding strategy. However, I still feel like this activity is a good way to practice spelling words while thinking about meaning. It is not using context to decode. It is using context to apply meaning to the word.

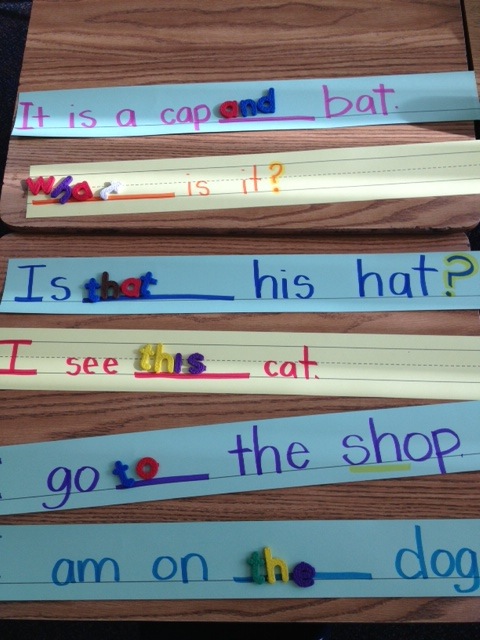

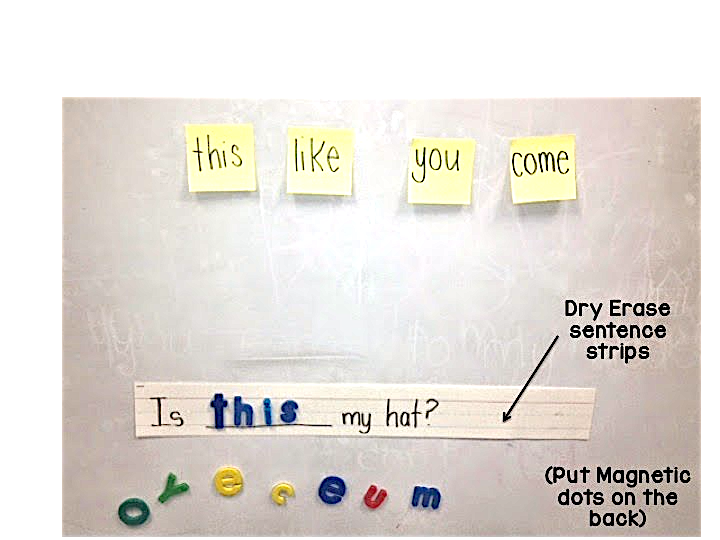

Write a sentence on sentence strips or on the whiteboard with a blank in the middle. Put the letters of a sight word scrambled next to or on the blank. Read the sentence, determine the word, then spell it correctly. Afterward, you can connect back to the sounds. Say the word, and point to the letters as you make their sounds. That means for a word like “what”, you would point to both <wh> for /w/.

For a larger group, put the sentence strips in a pocket chart with the sight word chopped up into letters.

You could also write the sentence on a magnetic whiteboard and use letter magnets.

I just want to be clear that this is not used as a decoding activity to guess as a reading strategy. Admittedly, that’s how I used to use these! Since then, I’ve learned that we do not want to put too much focus on using context because it takes away from decoding and leads to bad habits. I think it’s a fine activity to use once words have been taught explicitly. Plus kids see it as a puzzle and it can be fun for them.

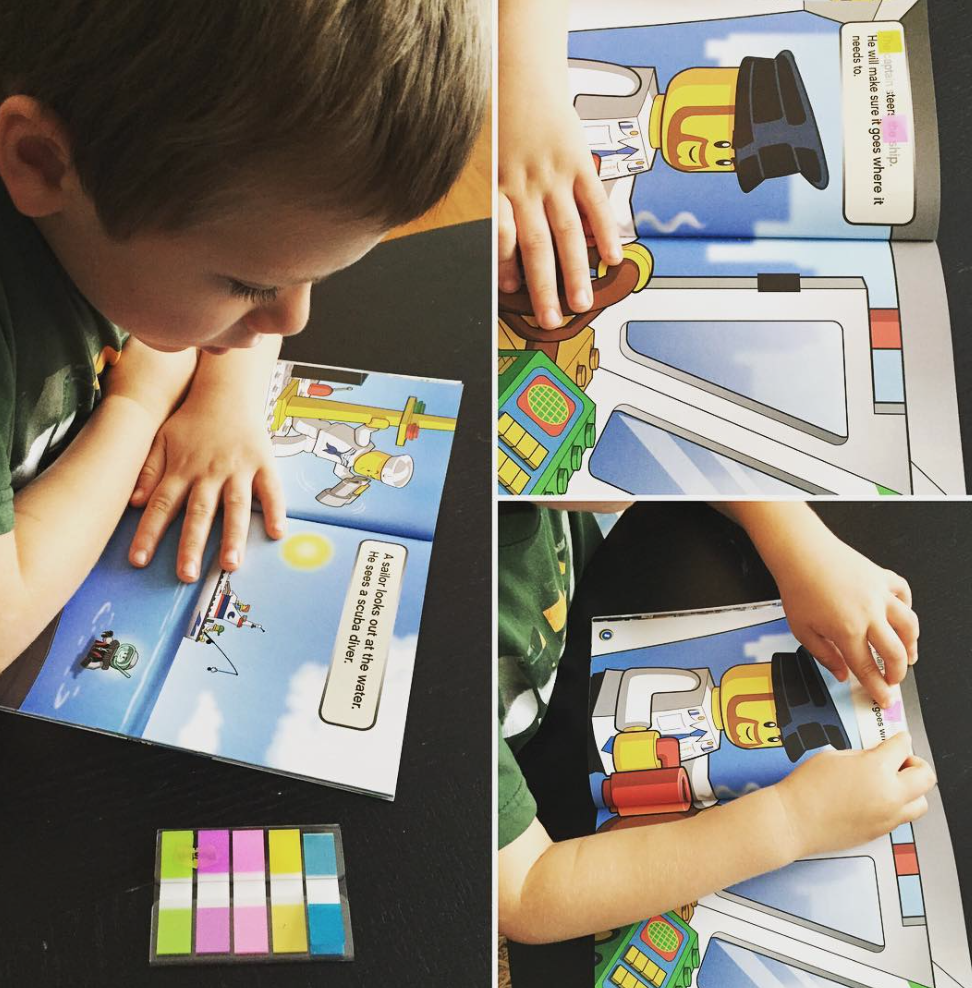

Sight Word “Hunts”

Get your students looking for those words! This can be a center, an independent activity, or a warm-up in reading groups. Have your kids look for a certain word in books or big poems.

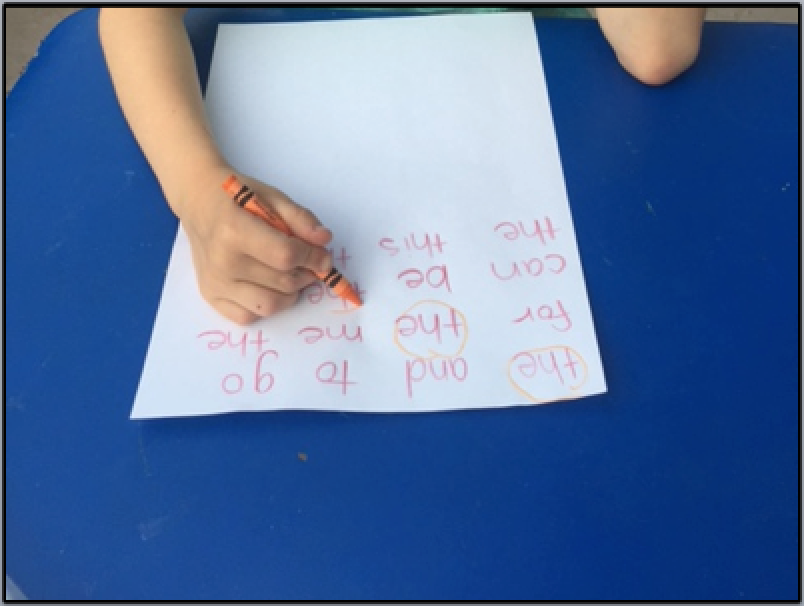

I blogged about this picture already last year. Both of my boys loved to search for words like this. They would focus on one word and try to find it. This was nice in the beginning because they didn’t necessarily have to know the other words on the page yet. They were just looking for that one word. I have several pre-made word hunts that I will show at the end of this post!

Step 5: Build from Words to Phrases to Sentences

The purpose of mastering high-frequency words is to gain automaticity with these words so that eventually your students will become fluent readers when reading a book or reading passage. BUT sometimes we skip so many steps in between. I know I’ve been guilty of that. Okay, you know that word, sweet! Let’s read this huge passage then. Wait! Rewind. What I mean is, let’s give you those building blocks so that you can read that huge reading passage. Our struggling and beginning readers can be VERY intimidated by a huge reading passage without support. With that said, many of our students learn sight words quickly and are ready for huge passages pretty quickly. I’m more focusing on your students who need a little extra time and guidance.

Sight Word Phrases

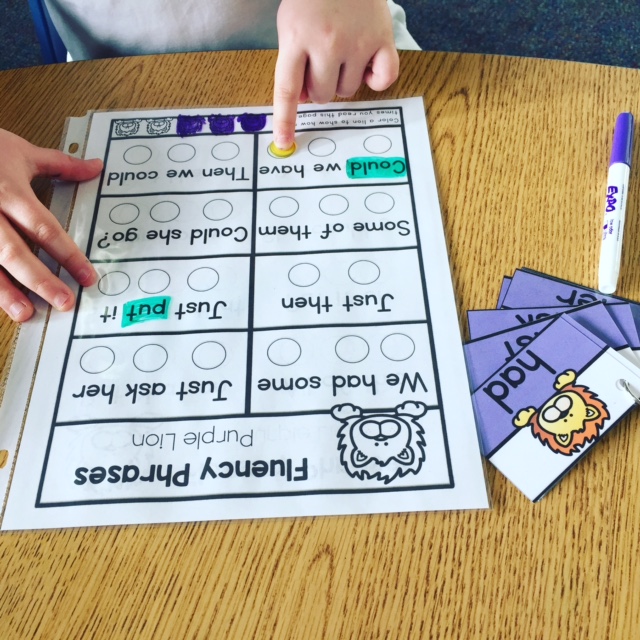

We’ve talked about practicing high-frequency words in isolation. Now we’re moving into reading those words in the context of a phrase, sentence, or reading passage. First, you can focus on phrases. These are the common phrases that go together. This is a great way to transition from word to sentence. It’s good for them to see these words in some context. You can actually find fluency phrases all over! Just google and there you will find tons.

I used these after my students had a little practice with the sight words individually. They are phrases, not complete sentences yet. It gives students the chance to practice reading with a little context.

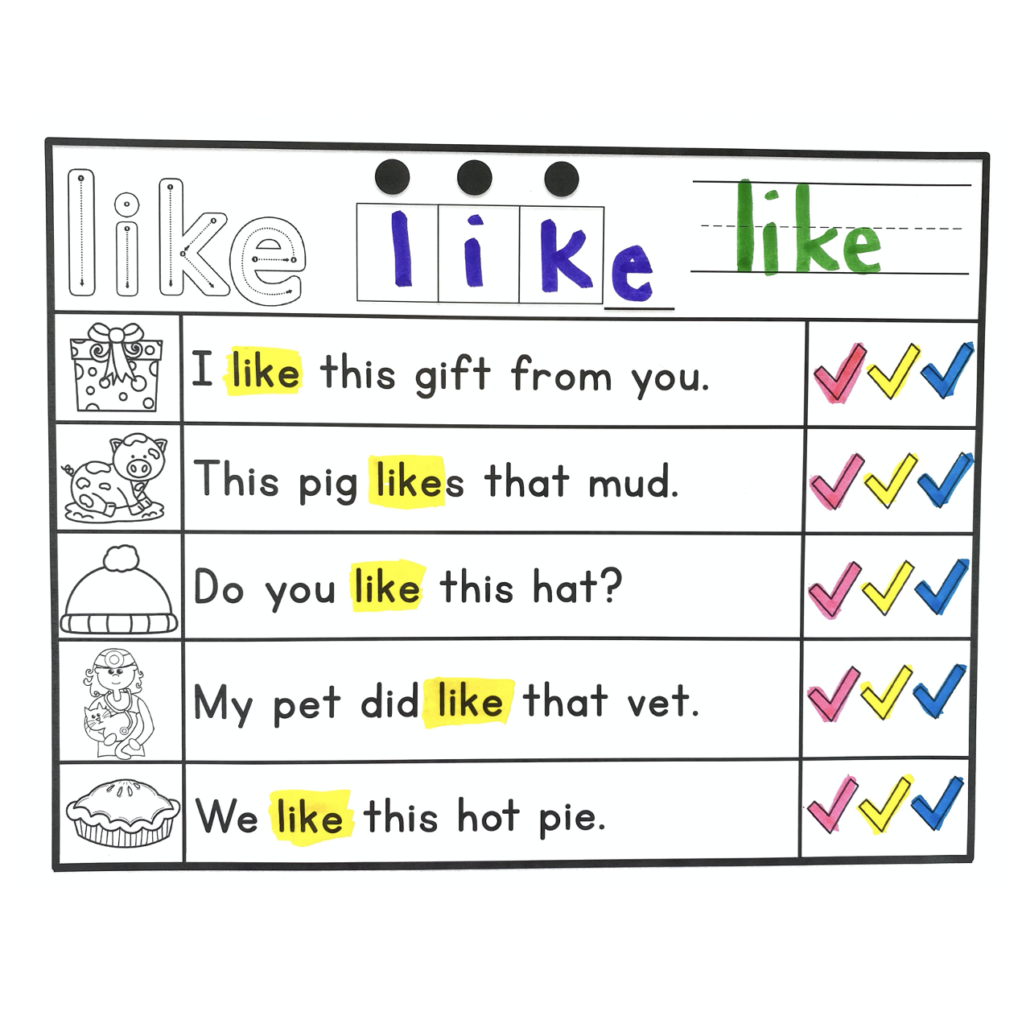

Simple Sentences

Here, I’ve made sentences with a focus on one high-frequency word. This one has the word “like” in each. I made sentences where the student could be successful using their knowledge of the new word, other high-frequency words they’ve already learned, and decodable words. This way, they can practice those words within connected text and be successful!

Give your students practice reading those words in context where they can be successful. You can write simple sentences using sentence strips or on chart paper, too!

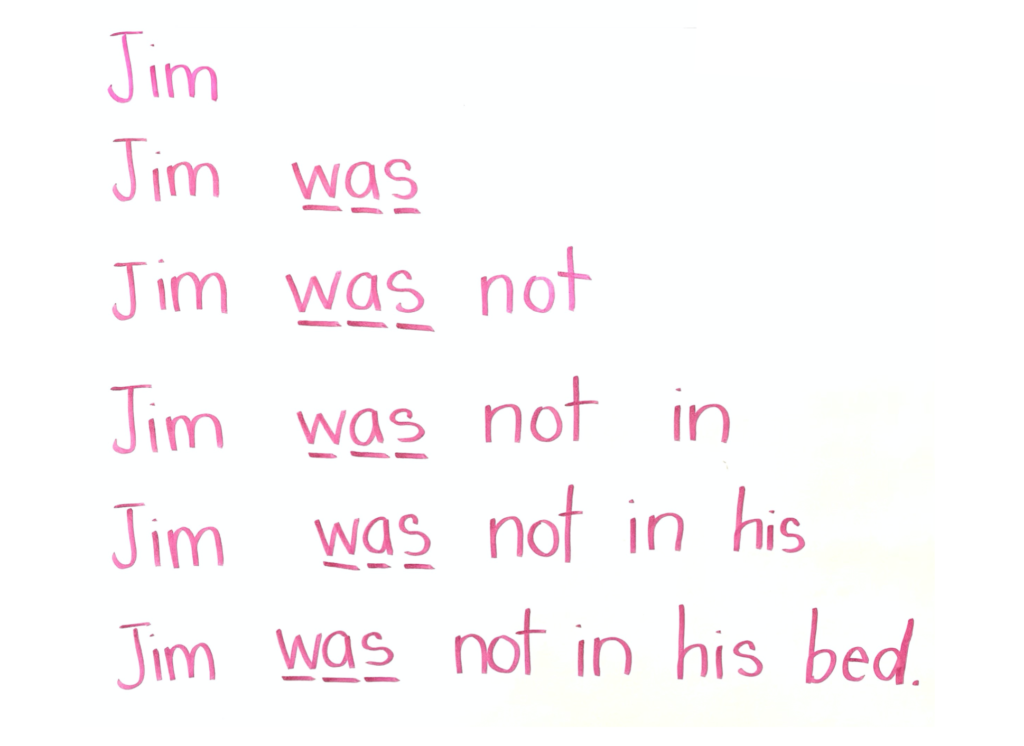

Sentence Ladders

Once students know a handful of sight words and are even reading those fluency phrases, we get a little excited about throwing them that reading passage or big ol’ book to read. And yes, absolutely that is our goal and many, many kids make that transfer seamlessly and quickly. However, some need a little extra something. I love making Sentence Ladders for my students. It gives them practice with sight words and helps develop fluency because they are rereading words in a sentence over and over.

Which List: Dolch, Fry…or Neither?

Originally, I was using the Dolch list. I created a ton of resources based around this list. I did and do love these resources and found they really helped my students. However, I also felt like these resources didn’t fit into my big picture instructionally. As I learned more about the science of reading, I started to rethink my approach.

Mainly, I was seeing that here I was teaching my kinder students to decode and spell CVC words. For my struggling readers, this was a lot. They would make gains with the right systematic, explicit instruction and were developing an understanding of how words work, at a pace that was appropriate. But then I’d also be like, “Oh yeah and we also have to learn the words “come”, “down”, and “find” because those are on the Dolch kindergarten pre-primer list and that’s just what we do. So, even though it felt like this just didn’t fit with everything else I was doing, I was still doing it. I created the Dolch resources you’ll see below and really tried my best to make them work. I think what I came up with was helpful considering these words were out of place with the rest of the curriculum.

Then I had an epiphany. Wait, I don’t have to teach high frequency words in this order, especially if the science is telling me otherwise. But not just the science. My students were showing me this too. I had already restructured the way I teach high-frequency words. Now I was going to change the order in which I teach them.

I looked over the Dolch and Fry lists and grouped the fully decodable words phonetically. Then I looked at the words that were decodable except for only one or two sound-symbol relationships. I placed those into the groups that made the most sense. Last, I looked at the real odd balls. These are the few words that really are irregular in my mind. I placed those where I felt they made the most sense instructionally.

Once I had a sequence, broke the words up into smaller, more manageable groups. This is one thing I had also done with the dolch list and it really helped my students. They felt more success when they mastered a small set of words (as opposed to looking at this huge list).

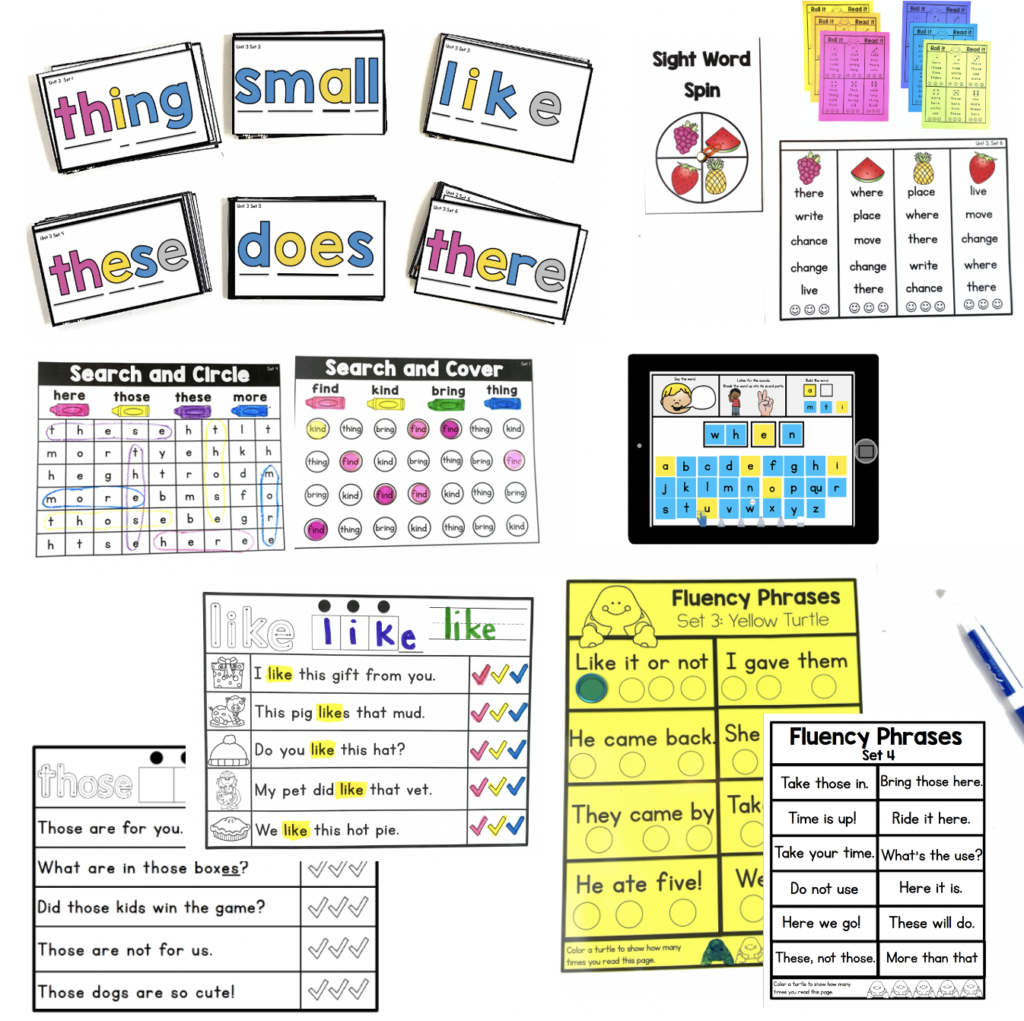

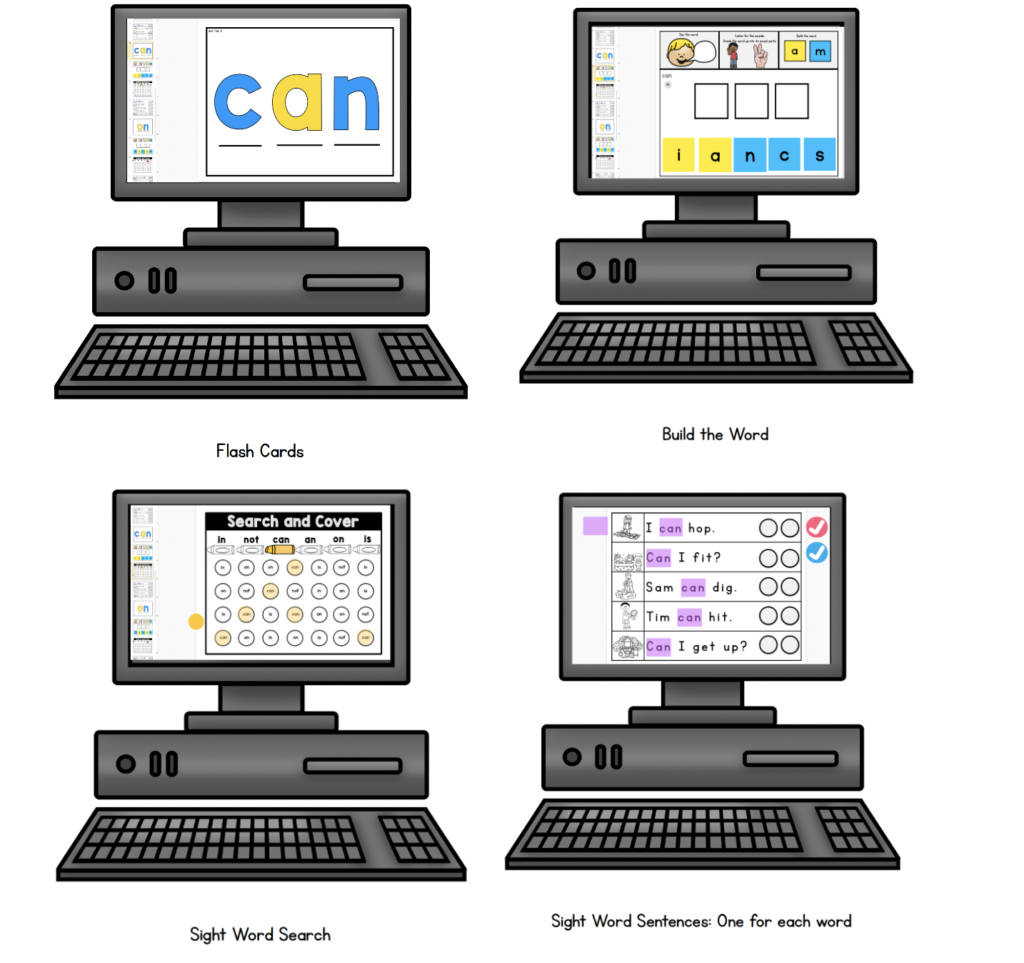

Then, I started making activities and teaching resources to go with those words and groups. I made flashcards that mirror the way I teach the words, fluency phrases for each group, sentences focusing on each sight word, word searches, and games.

Sight Word Instruction Resources

I have two different sight word resources. I explained above my evolution with sight word instruction. For this reason, I have two sets of sight word resources: Several resources based around the Dolch list and new resources using the phonetically-grouped list of words. I now use the phonetically-grouped list.

Phonetically-Grouped “Sight Word” Units

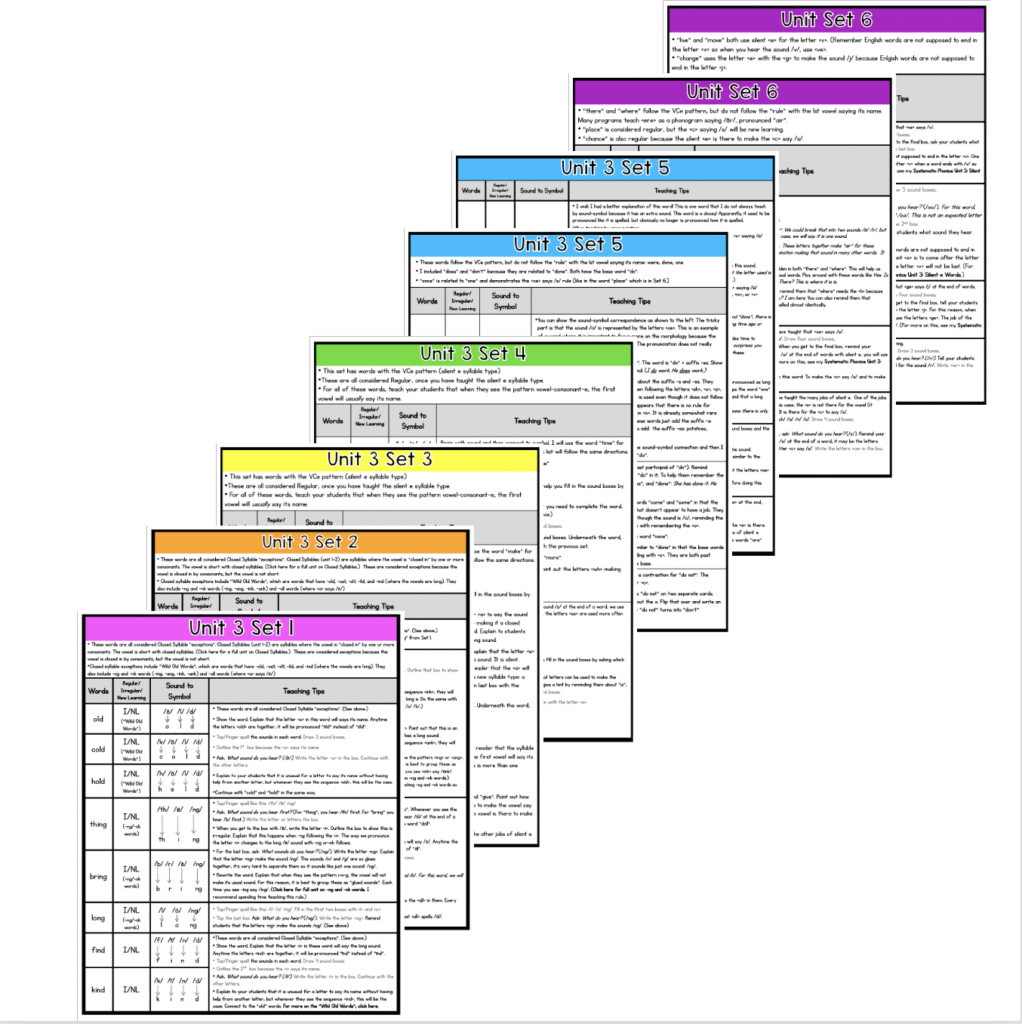

To integrate my “sight word” instruction into my existing phonics instruction, I grouped the high-frequency words phonetically. Like my Dolch units, I have one animal to represent each unit and then each unit is further divided into smaller sets, each with a color. In total, there are 6 units. See below for how the words are grouped:

This shows some of Unit 5.

- There are two choices for “flashcards“. One option is color-coordinated with vowels one color and consonants another color. There are also the underlines that represent sounds. (This is my favorite.)The other option is the more cutesie animals.

- There are “fluency phrases” (“printable” option and smaller cards to laminate). Those are just short phrases with high-frequency words from that set.

- Word Searches

- Automaticity games (one for each set): Spin and Read or Roll and Read

- Sentences: Each word has a whole page of 4-5 sentences and then another page that reviews all the words from that set. Option with pictures or without.

- Tracking sheets

There are also directions about how to teach the words using phoneme-grapheme mapping, along with any helpful tips.

I also made Google Slides:

THIS LINK will lead you to the bundle of all 6. If you just want to look at one unit, you will see a link to each individual unit from there.

References

David Kilpatrick’s books: Equipped for Reading Success and The Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties.

Louisa Moats: Speech to Print and LETRS books.

A Fresh Look at Phonics by Wiley Blevins.

Rethinking Sight Words. Article by Katharine Pace MilesGregory B. RubinSelenid Gonzalez‐Frey from the International Reading Association Journal.

Additional Posts about Sight Words

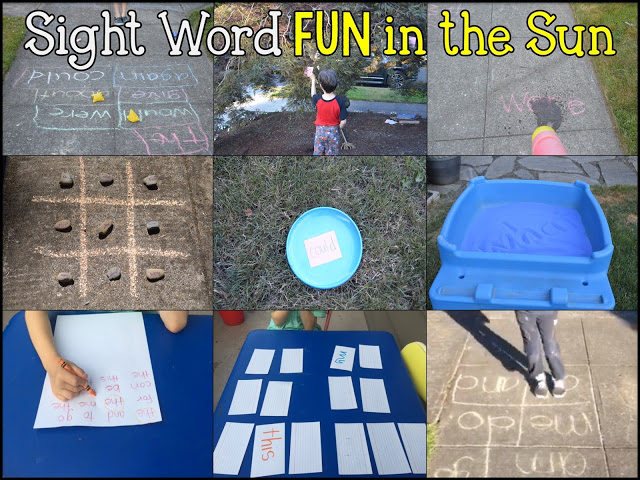

For another posts about sight words, click here. There, you will find ideas for the summer AND a printable pack for parents filled with ideas to practice sight words.

You can find this blog post here.