I’m trying to find a second word typed in a sentence. I have the first word determined and I’m having trouble finding how to get JUST the second word. This is what I’ve tried:

String strSentence = JOptionPane.showInputDialog(null,

"Enter a sentence with at" + " least 4 words",

"Split Sentence", JOptionPane.PLAIN_MESSAGE);

int indexOfSpace = strSentence.indexOf(' ');

String strFirstWord = strSentence.substring(0, indexOfSpace);

/*--->*/String strSecondWord = strSentence.substring(indexOfSpace, indexOfSpace);

Boolean blnFirstWord = strFirstWord.toLowerCase().equals("hello");

Boolean blnSecondWord = strSecondWord.toLowerCase().equals("boy");

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(null, "The sentence entered: " + strSentence

+ "nThe 1st word is " + strFirstWord

+ "nThe 2nd word is " + strSecondWord

+ "nIs 1st word: hello? " + blnFirstWord

+ "nIs 2nd word: boy? " + blnSecondWord);

asked Sep 23, 2013 at 21:24

Adariel LzinskiAdariel Lzinski

1,0332 gold badges19 silver badges41 bronze badges

1

You are taking the second word from the first space to the first space (its going to be empty). I suggest you take it until the second space or the end.

int indexOfSpace2 = = strSentence.indexOf(' ', indexOfSpace+1);

String strSecondWord = strSentence.substring(indexOfSpace+1, indexOfSpace2);

If you can use split you can do

String[] words = strSentence.split(" ");

String word1 = words[0];

String word2 = words[1];

answered Sep 23, 2013 at 21:28

Peter LawreyPeter Lawrey

523k77 gold badges748 silver badges1126 bronze badges

0

int indexOfSpace = strSentence.indexOf(' ');

String strFirstWord = strSentence.substring(0, indexOfSpace);

strSentence = strSentence.substring(indexOfSpace+1);

indexOfSpace = strSentence.indexOf(' ');

String strSecondWord = strSentence.substring(0, indexOfSpace);

strSentence = strSentence.substring(indexOfSpace+1);

indexOfSpace = strSentence.indexOf(' ');

String strThirdWord = strSentence.substring(0, indexOfSpace);

answered Sep 23, 2013 at 21:28

The first word is defined as the text between the start of the sentence and the first space, right? So String strFirstWord = strSentence.substring(0, indexOfSpace); gets that for you.

Similarly, the second word is defined as the text between the first space and the second space. String strSecondWord = strSentence.substring(indexOfSpace, indexOfSpace); finds the text between the first space and the first space (which is an empty String), which isn’t what you want; you want the text between the first space and the second space…

answered Sep 23, 2013 at 21:28

TimTim

2,02714 silver badges24 bronze badges

You can use split() method of String class. It part the string using a pattern. For example:

String strSentence = "word1 word2 word3";

String[] parts = strSentence.split(" ");

System.out.println("1st: " + parts[0]);

System.out.println("2nd: " + parts[1]);

System.out.println("3rd: " + parts[2]);

answered Sep 23, 2013 at 21:31

I would use regex:

String second = input.replaceAll("^\w* *(\w*)?.*", "$1");

This works by matching the entire input while capturing the second word and replacing what’s matched (ie everything) with what was captured in group 1.

Importantly, the regex is crafted such that everything is optional, which means that if there’s no second word, a blank results. This will also work with the edge case of blank input.

Another plus is it’s just one line.

answered Sep 23, 2013 at 21:30

Bohemian♦Bohemian

407k89 gold badges572 silver badges711 bronze badges

2.

Match the words in the box with their definitions.

There are four extra words which you do not need to use.

suburban

inexperience heap

novel

nursery

dreadful

bang occasion

funnily

cross

intention

poetry

1. unpleasant, very

poor in quality;

2. a sudden loud

noise, such as the noise of an explosion;

3. angry or

irritated;

4. a big amount of something;

5. situated outside

the city centre;

6. a long written

story about imaginary people and events ;

7. a room where

children sleep or play;

8. little knowledge

about a particular area or situation;

3. Put

the verbs in brackets into the correct form ( -ing-form, to-infinitive or bare

infinitive):

1. She

apologised for __________ (interrupt) the session.

2. They

seemed __________ (know) each other’s thoughts before they spoke.

3. John is

afraid of __________(fly).

4. I don’t

mind __________ (lend) you the book, but you must __________(return) it

to me next week.

5. It’s

cold outside. You’d better __________ (take) your coat.

6. We saw

them __________ (do) all the damage.

7. She

enjoys __________ (receive) people at home.

8. I would

like __________ (meet) that writer.

9. I

stopped __________ (play) football because of a knee injury.

10. This crossword is

impossible __________ (do).

11. They couldn’t

__________ (find) the way easily.

12. The English

teacher doesn’t let us __________(use) the dictionary while tests.

4.

Fill in the correct preposition:

5. Fill

in the correct word derived from the word in bold:

1. Agventurous

people get a lot of ………………………..going skydiving or rafting. ENJOY

2. In

the USA ……………………Day is celebrated on July 4. DEPEND

3. We

wish you the fastest …………………….. RECOVER

4. Please,

express your ………………………..with new rules directly. DISAGREE

5. Jack

stared at Helen in …………………………… AMAZE

6. Stay

in our comfortable …………………… and relax in style! ACCOMMODATE

7. Complete

the 2nd sentence using the word in bold so that it means the same as

the 1st:

1. I

don’t really love going to basketball matches.

keen I’m

……………………….. to basketball matches.

2. French

painting is up to her liking.

fond

She ………………………. French painting.

3. My

younger brother can play DOTS for long hours!

crazy

My younger brother ……………………. DOTS!

4. Lucy

is pleased with her son’s achievements.

proud Lucy’s

………………………. achievements.

5. In

fact, I can’t cook at all. I burn everything.

terrible

I am really …………………….

8. Read

the text and match the headings:

Keys:

1. 1-f,

2-h, 3-c, 4-g, 5-d, 6-I, 7-b, 8-j, 9-e, 10-a.

2.

1.dreadful 2. bang 3.cross 4. heap 5.suburban 6. novel 7. nursery 8. inexperience

3. 1.

interrupting 2.to know 3. flying 4. lending, return 5. Take 6. do/doing

7.Receiving

8. to meet

9. Playing 10. to do 11.find 12. use.

4.

2. down 3.up 4. After 5. Off 6. Over 7. Off

5

1.enjoyment 2. independence 3.recovery 4.disagreement 5.amazement 6. accommodation.

6.

1. keen on going 2.is fond of 3.is crazy about

playing 4.proud of her son’s 5. terrible at cooking.

7. 1-c,

2-e, 3-a, 4-d,5-b.

Test Module 2

- Match the words and phrases to make expressions:

- Dig deep

- Household

- Martial

- Estate

- Get out

- French

- Make ends

- Splash out

- Make up

- Shopping

a) Spree

b) Meet

c) Arts

d) Of breath

e) Funny stories

f) In one’s pockets

g) Agent

h) Chores

i) Windows

j) On expensive things

- Match the words in the box with their definitions. There are four extra words which

you do not need to use.

suburban inexperience heap novel nursery dreadful

bang occasion funnily cross intention poetry

- unpleasant, very poor in quality;

- a sudden loud noise, such as the noise of an explosion;

- angry or irritated;

- a big amount of something;

- situated outside the city centre;

- a long written story about imaginary people and events ;

- a room where children sleep or play;

- little knowledge about a particular area or situation;

- Put the verbs in brackets into the correct form ( -ing-form, to-infinitive or bare infinitive):

- She apologised for __________ (interrupt) the session.

- They seemed __________ (know) each other’s thoughts before they spoke.

- John is afraid of __________(fly).

- I don’t mind __________ (lend) you the book, but you must __________(return) it to me next week.

- It’s cold outside. You’d better __________ (take) your coat.

- We saw them __________ (do) all the damage.

- She enjoys __________ (receive) people at home.

- I would like __________ (meet) that writer.

- I stopped __________ (play) football because of a knee injury.

- This crossword is impossible __________ (do).

- They couldn’t __________ (find) the way easily.

- The English teacher doesn’t let us __________(use) the dictionary while tests.

- Fill in the correct preposition:

- Fill in the correct word derived from the word in bold:

- Agventurous people get a lot of ………………………..going skydiving or rafting. ENJOY

- In the USA ……………………Day is celebrated on July 4. INDEPEND

- We wish you the fastest …………………….. RECOVER

- Please, express your ………………………..with new rules directly. DISAGREE

- Jack stared at Helen in …………………………… AMAZE

- Stay in our comfortable …………………… and relax in style! ACCOMMODATE

- Complete the 2nd sentence using the word in bold so that it means the same as the 1st:

- I don’t really love going to basketball matches.

keen I’m ……………………….. to basketball matches.

- French painting is up to her liking.

fond She ………………………. French painting.

- My younger brother can play DOTS for long hours!

crazy My younger brother ……………………. DOTS!

- Lucy is pleased with her son’s achievements.

proud Lucy’s ………………………. achievements.

- In fact, I can’t cook at all. I burn everything.

terrible I am really …………………….

- Read the text and match the headings:

Answers:

Task 1

1-f, 2-h, 3-c, 4-g, 5-d, 6-I, 7-b, 8-j, 9-e,10-a.

Task 2

1-dredful, 2-bang, 3-cross, 4-heap, 5-suburban, 6-novel, 7-nursery, 8-inexperience.

Task 3

1-interrupting, 2-to know, 3-flying, 4-lending, return, 5-take, 6-do/doing, 7-receiving, 8-to meet,

9-playing, 10-to do, 11-find, 12-use.

Task 4

2-down, 3-up, 4-after, 5-off, 6-over, 7-off.

Task 5

1-enjoyment, 2-independence, 3-recovery, 4-disagreement, 5-amazement, 6-accommodation.

Task 6

1-keen on going, 2-is fond of, 3-is crazy about playing, 4-proud of her son’s, 5-terrible at cooking.

Task 7

1-c, 2-e, 3-a, 4-d,5-b.

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

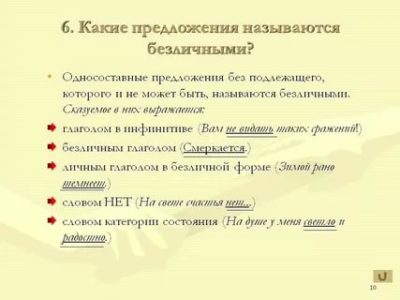

One-piece sentences

Sentences whose grammatical base consists of two main members (subject and predicate) are called two-part.

Sentences, the grammatical base of which consists of one main member, are called one-part. One-part sentences have a complete meaning, and therefore the second main term is not needed or even impossible.

For example: In the summer I will go to the sea. Dark. It’s time to go. Magic night.

One-part sentences, as opposed to incomplete ones, are understandable out of context.

There are several types of one-part sentences:

• definite personal, • indefinite personal, • generalized personal, • impersonal,

• denominational (nominative).

Each of the types of one-part sentences differs in the peculiarities of the meaning and the form of expression of the main member.

Definitely personal suggestions

Definitely personal suggestions — these are one-piece sentences with the main predicate member, conveying the actions of a certain person (speaker or interlocutor).

In definitively personal proposals the main member is expressed by a verb in the form of 1 and 2 persons singular and plural indicative mood (in the present and in the future tense), and in the imperative mood; the producer of the action is defined and can be called personal pronouns of the 1st and 2nd person я, you, we, you.

For example: I love thunderstorm in early May (Tyutchev); We will patiently endure trials (Chekhov); Go, bow down fish (Pushkin).

In definite personal suggestions predicate cannot be expressed by a 3rd person singular verb and a verb in the past tense… In such cases, the offer does not contain an indication of a specific person and the offer itself is incomplete.

Compare: Do you know Greek too? — I studied a little (Ostrovsky).

Uncertain personal suggestions

Uncertain personal suggestions — these are one-part sentences with the main predicate member, conveying the actions of an indefinite subject.

In vaguely personal sentences the main member is expressed by a verb in the 3-person plural form (present and future tense in the indicative mood and in the imperative mood), past tense plural indicative and similar conditional verb.

The originator of the action in these sentences is unknown or unimportant.

For example: In the house knocked oven doors (A. Tolstoy); On the streets somewhere far away shoot(Bulgakov); Would give man relax in front of the road (Sholokhov).

Generalized personal suggestions

Generalized personal suggestions — these are one-piece sentences with the main predicate term, conveying the actions of the generalized subject (the action is attributed to each and every one separately).

The main term in a generalized personal sentence may have the same modes of expression as in definitively personal and indefinitely personal sentences, but most often expressed by a 2nd person singular and plural verb present and future tense or a 3rd person plural verb.

For example: Good for bad don’t change (proverb); Not very senior now respected (Ostrovsky); What sow, then reap(proverb).

Generalized personal sentences are usually presented in proverbs, sayings, catch phrases, aphorisms.

Proposals containing the author’s generalization are also generalized personal. The speaker uses the 1nd person verb instead of the 2st person verb to give a generalized meaning.

For example: Go out sometimes outside and surprised transparency of air.

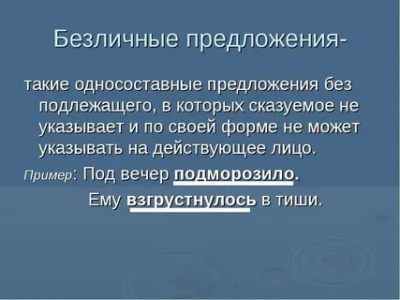

Impersonal sentences

Impersonal sentences — these are one-part sentences with a leading predicate term, transmitting actions or states that arise regardless of the producer of the action.

In such proposals it is impossible to substitute the subject.

The main member of an impersonal sentence can be similar in structure to a simple verbal predicate and is expressed:

1) an impersonal verb, the only syntactic function of which is to be the main member of impersonal one-part sentences:

For example: It’s getting colder / getting colder / will get colder.

2) a personal verb in an impersonal form:

For example: Getting dark.

3) to be a verb and not a word in negative sentences:

For example: Winds did not have / no.

The main member, similar in structure to the compound verb predicate, can have the following expression:

1) modal or phasic verb in impersonal form + infinitive:

For example: Outside the window it got dark.

2) the linking verb be in the impersonal form (in the present tense in the zero form) + adverb + infinitive:

For example: Sorry / it was a pity to leave with friends.

It’s time to get ready on the road.

The main member, similar in structure to the compound nominal predicate, is expressed:

1) verb-linking in impersonal form + adverb:

For example: It was a pity old man.

On the street. became freshly.

2) a linking verb in an impersonal form + a short passive participle:

For example: In a room was smoked.

A special group among impersonal sentences is formed by infinitive sentences.

The main member of a one-part sentence can be expressed by an infinitive that does not depend on any other member of the sentence and denotes an action possible or impossible, necessary, inevitable. Such sentences are called infinitive.

For example: Tomorrow be on duty… To all get up! Would go to Moscow!

Infinitive sentences have different modal meanings: must, necessity, possibility or impossibility, inevitability of action; as well as motivation for action, command, command.

Infinitive sentences are subdivided into unconditional (Be silent!) And conditionally desirable (would read).

Nominative (nominative) sentences

Nominative (nominative) sentences — these are one-piece sentences that convey the meaning of being (existence, presence) of the subject of speech (thought).

The main member in a nominative sentence can be expressed by a noun in the nominative case and a quantitative-nominal combination.

For example: Night, street, lamp, pharmacy… Pointless and dim light(Block); Three wars, three hungry pores, what the century has awarded (Soloukhin).

Indicative particles may be included in nominative sentences. they, here, and for the introduction of emotional assessment — exclamation particles well и, what, like this:

For example: What weather! Well rain! Like this storm!

The distributors of the nominative sentence can be agreed and inconsistent definitions:

For example: Late autumn.

If the distributor is the circumstance of place, time, then such sentences can be interpreted as two-part incomplete:

For example: Coming Soon autumn… (Compare: Coming Soon autumn will come.)

Outdoors rain… (Compare: On the street it’s raining.)

Nominative (nominative) sentences can have the following subspecies:

1) Proper-existential sentences expressing the idea of the existence of a phenomenon, object, time.

For example: April 22 year. Sineva… The snow has melted.

2) Indicative-existential sentences. The basic meaning of beingness is complicated by the meaning of indication.

For example: Here mill.

3) Evaluative-existential (Dominance of evaluation).

For example: Well and day! Oh yeah! And already character! + particles well, then, also to me, and also.

The main member can be an evaluative noun (Beauty. Nonsense.)

4) desirable-existential (particles only, if only).

For example: If only health… Not just death. If happiness.

5) incentive (incentive-desirable: Attention! good afternoon! and imperative-imperatives: Fire! etc.).

It is necessary to distinguish constructions from nominative sentences that coincide in form with them.

— Nominative case as a simple name (name, inscription). They can be called proper-naming — there is absolutely no meaning of beingness.

For example: «War and Peace».

— Nominative as a predicate two-part sentence (Who is he? Familiar.)

— The nominative case of the topic can be attributed to the isolated nominative, but meaningfully they do not have the meaning of beingness, do not perform a communicative function, form a syntactic unity only in combination with the subsequent construction.

For example: Moscow… How much of this sound has merged for the Russian heart Autumn… I especially love this time of the year.

Source: https://videotutor-rusyaz.ru/uchenikam/teoriya/222-odnosostavnyepredlogeniya.html

Russian language rules

Oak is a tree.Optics is a branch of physics.The elder brother is my teacher.My elder brother is a teacher.

Note 1. If there is a negation not in front of a predicate, a pronounced noun in the nominative case, then a dash is not put, for example:

Poverty is not a vice.

Note 2. In an interrogative sentence with a main member expressed by a pronoun, a dash between the main members is not put, for example:

Who is your father?The purpose of each person is to develop in himself everything that is human, common and enjoy it. (Belinsky). Living life is not a field to cross.Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country (Lenin). Poetry is the fiery gaze of a youth seething with excess strength (Belinsky). Romanticism is the first word that announced the Pushkin period, nationality is the alpha and omega of the new period (Belinsky). Hope and swimmer — the whole sea swallowed (Krylov). Neither the crows of a rooster, nor the sonorous rumble of horns, nor the chirping of an early swallow on the roof — nothing will call the deceased from the coffins (Zhukovsky).

- If you can put it in front of the application without changing the meaning namely, For example:

- If the application contains explanatory words and it is necessary to emphasize the shade of independence of such an application, for example:

I don’t like this aspen tree too much (Turgenev). In relations with outsiders, he demanded one thing — the preservation of decency. (Herzen). Paying tribute to his time, Mr. Goncharov also brought out the antidote to Oblomov — Stolz (Dobrolyubov).

I had a cast-iron teapot with me — my only joy in my travels in the Caucasus (Lermontov).

I went out, not wanting to offend him, on the terrace — and was stupefied (Herzen). I hurry there — and there is already the whole city (Pushkin). I wanted to go around the whole world — and did not go around a hundredth (Griboyedov). I wanted to paint — the brushes fell out of my hands. I tried to read — his gaze slid over the lines (Lermontov).

Note 1. To enhance the shade of surprise, a dash can be placed after the compositional conjunctions connecting two parts of one sentence, for example:

Ask for a calculation on Saturday and — march to the village (M. Gorky). I really want to go there to them, get to know them, but — I’m afraid (M. Gorky).

Note 2. To express surprise, any part of the sentence can be separated by a dash, for example:

And they threw the pike into the river (Krylov). And ate the poor singer — to the crumb (Krylov). I am a king — I am a slave, I am a worm — I am a god (Derzhavin). It’s no wonder to cut off your head — it’s tricky to put (proverb). They don’t live here — paradise (Krylov). Praises are tempting — how can you not wish them? (Krylov). The sun is up — the day begins (Nekrasov). Gruzdev called himself get in the body.The forest is being cut down — the chips are flying.Confused yourself — unravel yourself; knew how to make porridge — be able to disentangle it; if you like to ride — love to carry sledges (Saltykov-Shchedrin). I ask you: do workers need to be paid? (Chekhov). Pustoroslev for his faithful service — Chizhov’s estate, and Chizhov — to Siberia forever (A. N. Tolstoy). We are villages — to ashes, hailstones — to dust, to swords — sickles and plows (Zhukovsky). Everything is obedient to me, but I am to nothing (Pushkin).

§ 174 By means of a dash the following are distinguished:

For parentheses, see § 188.

- Sentences and words inserted in the middle of a sentence for the purpose of clarifying or supplementing it, in cases where brackets can weaken the connection between the insertion and the main sentence, for example:

Here — there is nothing to do — friends kissed (Krylov). Suddenly — lo and behold! oh shame! — spoke the oracle nonsense (Krylov). Only once — and even then at the very beginning — there was an unpleasant and harsh conversation (Furmanov).

For application commas see § 152.

- A common application after the noun being defined, if it is necessary to emphasize the shade of independence of such an application, for example:

The senior sergeant — a brave elderly Cossack with badges for long-term service — ordered to «build up» (Sholokhov). In front of the doors of the club — a wide log house — workers with banners awaited guests (Fedin).

- A group of homogeneous members standing in the middle of a sentence, for example:

Usually from the riding villages — Elanskaya, Vyoshenskaya, Migulinskaya and Kazanskaya — they took Cossacks into the 11-12th Army Cossack regiments and in the Life Guards Atamansky (Sholokhov).

Note. A dash is placed after an enumeration in the middle of a sentence if this enumeration is preceded by a generalizing word or words somehow, for example, namely (see § 160).

I knew very well that this was my husband, not some new, unknown person, but a good person — my husband, whom I knew as myself (L. Tolstoy). Now, as a forensic investigator, Ivan Ilyich felt that all, without exception, the most important, smug people — everything was in his hands (L. Tolstoy). Who is to blame, who is right, is not for us to judge (Krylov). Did Stolz do anything for this, what he did and how he did — we do not know. (Dobrolyubov). Oh, if it is true that in the night, When the living rest, And from the sky, moonbeams Slide onto the grave stones,

Silent graves empty, —

I call the shadow, I wait for Leila:

To me, my friend, here, here!

(Pushkin). In the 1800s, in a time when there were no railways, no highways, no gas or stearin light, no spring low sofas, no furniture without varnish, no disillusioned youths with glass, no liberal philosophers-women, nor the lovely ladies-camellias, of which there are so many divorced in our time, in those naive times, when from Moscow, leaving for St. Petersburg in a cart or carriage, they took with them a whole home-made kitchen, drove for eight days along a soft, dusty or dirty road and they believed in fire cutlets, Valdai bells and bagels; when tallow candles were burning on long autumn evenings, lighting up family circles of twenty and thirty people, wax and spermaceti candles were inserted into the candelabra at balls, when the furniture was placed symmetrically, when our fathers were still young, not only by the absence of wrinkles and gray hair, but shot for women, from another corner of the room, rushed to pick up handkerchiefs that had been dropped by accident or not; our mothers wore short waists and huge sleeves and decided family matters by taking out tickets; when the lovely camellia ladies were hiding from the daylight; in the naive times of the Masonic lodges, the Martinists of the Tugendbund, in the times of the Miloradovichs, Davydovs, and Pushkins, there was a congress of landowners in the provincial town of K. and the noble elections ended (L. Tolstoy). Flights from the USSR to America.Manuscripts of the XNUMXth — XNUMXth centuries

Source: https://therules.ru/dash/

Personal, vaguely personal and impersonal sentences in English

Personal sentences are sentences in which the subject expresses a person, object or concept.

The child began to cry.

The child began to cry.

Sometimes the subject is not indicated, but it is implied (more often in imperative sentences).

And don’t cross the street against the lights.

And do not cross the street by the light (meaning you «you»).

Note. For ways of expressing subjects, see Subject in English

Uncertain personal suggestions

Uncertain personal sentences are sentences in which the subject is expressed by an indefinite person.

In English, pronouns are used in the function of the subject of an indefinite personal sentence (in the meaning of an indefinite person) one, you or they (the latter is excluding the speaker).

In Russian, there is no subject in vaguely personal sentences. When translating English indefinite sentences into Russian, pronouns one, you и they are not translated, and English vaguely personal sentences are generally translated into Russian by vaguely personal or impersonal sentences.

One must be careful when driving a car.

Necessary be careful when driving.

You never know what he may bring next time. (- One never knows)

You never know (hard to say) what he can bring next time.

You may walk miles without seeing one.

One can (You can) walk many miles without meeting anyone.

They are drunk that a new theater will soon be built here.

They saythat a new theater will soon be built here.

Impersonal sentences

In Russian, an impersonal sentence is a sentence in which there is no subject: Winter. Coldly. Dark. It’s time to start working.

In English, there is a subject in impersonal sentences, but it does not express the person or object that performs the action. The function of this formal subject is expressed by the pronoun it, which is usually not translated into Russian.

Impersonal sentences are used:

1. When designating:

a) time:

It is 6 o’clock. 6 o’clock.

It is late. Late.

b) distances:

It is three miles from here. (It’s) three miles from here.

c) natural phenomena, the state of the weather, the emotional state of a person:

It is winter. Winter. It is cold. Coldly.

It is snowing (raining). It’s snowing (rain)

2. In the presence of impersonal turns, it seems — it seems, it appears — obviously, apparently, it happens — it turns out.

It happened that nobody had taken the key to the flat. It turned out that no one took the key to the apartment.

it seems that I have left my textbook at home.

It seems (that) I left the tutorial at home.

The verb shall is used as an auxiliary verb for the formation of the future tense in the 1st person singular and plural. The verb will is used as an auxiliary verb for the formation of the future tense with the 2nd and 3rd person singular and plural.

Source: https://catchenglish.ru/grammatika/lichnye-neopredelenno-lichnye-i-bezlichnye-predlozheniya.html

Using impersonal sentences in English

The British love accuracy, so in English the main thing is to adhere to a clear sentence structure. Everything should be in order: first the subject, then the predicate, then the secondary members of the sentence, etc.

However, there are sentences in English that are called impersonal.

It is difficult to compare them with the chaotic impersonal sentences in Russian, devoid of the subject, such as «Evening», «Light», since in these structures the subject is still there. But first things first.

3 types of offers to be aware of

In English, as in Russian, there are 3 types of sentences: personal, vaguely personal and impersonal.

In personal sentences, the subject expresses a person, object or concept. Everything is simple here: The child began to cry / The child began to cry.

In indefinite personal sentences, the subject is expressed by an indefinite person. The pronouns one, you or they perform the functions of a subject indefinitely-personal sentence in English.

- One must be graceful to his parents. — You need to be grateful to your parents.

- You never guess what she may bring next time. (- One never guess) — You will never guess (hard to say) what she might bring next time.

- You may walk along the street without meeting one. — You can (you can / you can) walk along the street and not meet anyone.

- They say that a new mall will be built here next year. — They say that next year a new shopping center will be built here.

In Russian, an impersonal sentence is a sentence in which there is no subject: Winter. It is light. Coldly. It’s frosty. Dark. It’s time to leave. Impersonal sentences in English, as noted above, are not devoid of a subject. However, it does not express the person or object performing the action. The function of the so-called «formal» subject is performed by the pronoun it, which, as a rule, is not translated into Russian.

Cases of using impersonal constructions

- When designating time, distance, natural phenomena, the state of the weather, the emotional state of a person.

- It is 3 o’clock. 3 hours.

- It is late. Late.

- It is ten miles from here. (It’s) ten miles from here.

- It is summer. Summer.

- It is frosty. It’s frosty.

- It is raining (snowing). It’s raining (snowing)

- In the presence of such impersonal turns as it seems (seems), it appears (apparently, apparently), it happens (turns out).

- It seems that I’ve forgotten my identity card at home. — It seems (that) I forgot my passport at home.

- It appears that he will win. — Obviously he will win.

- It happened that nobody had made homework. — It turned out that no one had done their homework.

2 types of impersonal sentences

In English, they are of two types: nominal and verb. The first got their name due to the presence of an adjective in their structure. Their structure includes the verb to be and they are formed according to the following scheme:

subject + linking verb to be + nominal predicate + object

Let’s consider examples of structures of a nominal impersonal sentence in the table.

| Subject matter | Linking verb to be | Nominal part of the predicate | Addition | Transfer |

| It | is | stuffy | here | It’s stuffy here |

| It | is | amazing | that we saw it our own eyes | It’s great that we saw it with our own eyes |

| It | was | late | when he came | It was getting late when he arrived |

| It | is | pleasant | to be on this island | It’s nice to be on this island |

Examples of structures of a verbal impersonal sentence.

| Subject matter | Linking verb to be | Semantic verb | Addition | Transfer |

| It | snow | a lot in Alaska | It often snows in Alaska | |

| It | rained | cats and dogs last Monday | It rained like a bucket last Monday | |

| It | will | snow | next tuesday | It will snow next tuesday |

The construction of interrogative and negative forms of verbal impersonal sentences occurs according to the general rules of ordinary verbal predicates: the grammatical time used in the sentence is taken into account, and auxiliary words are used that are necessary to pose the question.

Mistakes Beginners

The most common beginner mistake is trying to translate impersonal sentences verbatim. Even the most simple sentences can be correctly translated by understanding the following rules:

- do not rush to translate if in Russian a sentence begins with indirect pronouns: me, him, her, them, us. Think carefully about how to say it in English;

- remember that in English a sentence always begins with a subject, and if this subject is a pronoun, then it must necessarily be in the nominative case: he, she, it, I, you, they, we, but not us, them, me, him , her.

Below are examples of constructs in which beginners most often make mistakes.

- I don’t like this novel = I don’t like this novel. — I don’t this novel. (Me not this novel).

- She has a son. = She has a son. — She has a son. (Her be a son.)

- My name is Katya. = My name is Katya. = I am Katya. — My name is Kate. I am Kate. (Me is Kate).

- They live well. = They live well. — They live well. (Them lives good).

Exercises for consolidation

To better understand all of the above rules, the impersonality of a sentence and consolidate knowledge, try a simple translation exercise:

- It will be hot ..

- Stuffy ..

- It was raining and snowing on Monday.

- It was warmer three days ago ..

- It will be cold in March. …

Source: https://englishfull.ru/grammatika/bezlichnye-predlozheniya.html

Parse proposal by members

Parsing a word by its composition Find co-root words Check uniqueness Find synonyms for words Check spelling Recognize

The service allows you to automatically parse the proposal by members.

Members of the Russian language proposal

Words and word combinations that are connected by syntactic relations when constructing a sentence constitute a special section. All members of the proposal are divided into:

Prepositions, conjunctions, particles and interjections do not differ as a member of a sentence. Introductory constructions and appeals join this group.

The main members of the proposal

Subject and predicate have the main semantic function. They are the grammatical basis of the sentence.

A subject is a subject who performs an action. Who answers the questions? what? It is always in the nominative case. For example, the birds are singing. The action is performed by the birds — this is the subject.

The predicate indicates the action of the subject. Answers the questions: what to do? what to do? what? what it is? For example, a house is a fortress. House what is it? Fortress is a predicate.

According to the presence of the main members and their number, the proposal is:

- two-part or one-part;

- simple or complex.

In a two-part sentence, there are both predicate and subject. For example, spring is coming. At the core of a one-part sentence, only one of the main members is implied. For example, it’s spring outside.

A simple sentence reflects only one stem from the subject / predicate. With two or more stems, it is called complex. For example: Summer is coming soon. Summer is coming soon, and the berries will ripen again.

When parsing a sentence in writing, the subject is underlined with one line, the predicate — with two.

Secondary members of the proposal

The secondary information is carried by three members of the proposal, which are closely related to the main members, explain the main idea.

Depending on the presence of secondary members, there are:

- common and uncommon.

An uncommon sentence consists only of a subject and a predicate (in a one-part sentence with one main member). For example: Spring. Children draw.

If there is a minor member, the offer is considered extended. For example: A fragrant spring. Children draw birds.

Add definition, addition and circumstance for additional information.

Addition

Indicates an object and answers questions of indirect cases: who? what? to whom? what? whom? what? by whom? how? about whom? about what?

There is a direct object: in the accusative case, the object does not need a preposition when answering a question. For example, I see (who?) Mom.

Indirect object is the forms of all other cases, regardless of the presence of a preposition; in the accusative case, a preposition is required. For example, believe (what?) In justice.

Parts of speech that express complement:

- noun;

- adjective as a noun;

- participle as a noun;

- pronoun;

- indefinite form of the verb (infinitive);

- phrase;

- phraseological units.

In written parsing, the addition is underlined with a dotted line.

Definition

Indicates a feature of an object and answers the questions which one? whose? Refers to a noun or part of speech that acts as a noun. According to the method of agreement, the definitions are:

- agreed;

- inconsistent;

The agreed definition applies in the same gender, number, case as the word being defined. Inconsistent definitions are associated with the word being defined using contiguity, control.

The writing definition is underlined with a wavy line.

Circumstance

Indicates the place, time, mode of action and degree, as well as the reason, condition, comparison, purpose of the action. Depending on the type, it answers the questions: where? when? where? since when? as? how? why? from what? why? why? for what purpose? how?

In a written analysis, the circumstance is marked with a dot-and-dash line.

So, there are main and secondary members of the proposal. You can especially consider homogeneous members of the sentence that refer to the same word, answer the same question.

How the sentence is parsed

To parse a sentence by member, you need to follow a simple algorithm. It consists in the following: first, the grammatical basis of the sentence is found. Ask nominative questions «who?» and what?». This will be the subject. Most often it is expressed by a noun, pronoun, or the initial form of a verb.

You can find the predicate by asking the age-old question that Nikolai Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky thought about: «What to do?» It is very suitable for that member of the sentence, which is expressed by such an interesting morphological unit as a verb. By underlining the subject with one line, and the predicate with two, you can further parse. You should be careful when parsing, since there are sentences with one main term, subject or predicate.

Now we need to explain the main thing.

Finding all the secondary members of a sentence will become easier if you know which part of speech they are usually expressed. A complement is a noun or its substitute pronoun in five cases (excluding the nominative). Such cases are called indirect.

Definitions are expressed by an adjective, participle, pronoun and answer the questions: «what?» and «whose?» An adverb, a participle, a noun and an indefinite form of a verb in a sentence perform the function of a circumstance if they answer the questions: how, where, from where, where, for what reason.

We underline the additions with a dotted line, the definition is wavy, the circumstance is a dotted line with a dot.

Special cases

The proposals with homogeneous members of the proposals are original. Homogeneous ones are so called because they mean the same thing, which means that it should be noted that homogeneous terms answer the same question

Source: https://progaonline.com/members_proposal

The grammatical basis of the sentence: what constitutes the basis and scheme of this in complex constructions, how to determine the main members and their types

As part of the grammatical base, there are subject and predicate… If a sentence consists of one main member, then this is only a subject or predicate.

There are no proposals without a foundation (except for incomplete ones)!

Find the subject. Questions WHO? or WHAT?

The subject is the main member of the sentence, grammatically independent.

In a typical sentence, it is the subject (in the broad sense) referred to in the sentence. This is a nominative word. Most often it is a noun or pronoun that answers the questions: Who? or What?

Examples:

- The wolf came out of the forest (What or what is the sentence about? About the wolf, that is, we pose the question: Who? Wolf. Noun).

- A shaggy black dog suddenly jumped out of the sedge thickets (Who? Dog. Noun).

- I smiled and walked forward. (Who? I. Pronoun).

There are some cases when the subject is expressed in other ways (not a noun and not a pronoun):

| Other ways of expressing the subject | Examples |

| Numeral (quantitative and collective) name as a noun | Three came out of the forest. |

| Adjective as a noun | Well fed hungry is not a comrade. |

| Participle as a noun | Vacationers were having fun. The road will be mastered by the walking one. |

| Adverb | Tomorrow will definitely come. |

| Interjection | A hurray burst out in the distance. |

| Phrase | My friends and I left earlier. A lot of schoolchildren took part in the competition. |

| Infinitive | Composing is my element. |

We find the predicate. Questions: WHAT DOES IT DO?

What are the predicates?

The predicate is associated with the subject and answers the question that is asked to it from the subject: What does the subject do?

But with the appropriate expression of the subject (see the table above), these may be other questions: What is an object ?, What is an object), etc.

Examples:

- The wolf came out of the forest (We ask a question from the character, from the subject: what did the wolf do? Out — this is a predicate, expressed by a verb).

- A shaggy black dog suddenly jumped out of the sedge thickets (What did the dog do? Jumped out).

- I smiled and walked forward. (What I did — smiled and went).

There are three types of predicates in Russian:

- Simple verb (one verb). Example: The wolf came out.

- Compound verb (auxiliary verb + infinitive). Example: I am hungry. I have to go to Suzdal (essentially two verbs in a predicate).

- Compound nominal (linking verb + nominal part). Example: I will be a teacher (essentially a verb and another part of speech in a predicate).

Difficult cases in determining predicates

The 1 situation… Often, problems with the definition of a predicate arise in a situation where a simple verb predicate is expressed in more than one word. Example: Today you will not have lunch alone (= will have lunch).

In this sentence, the predicate you will have dinner is a simple verb, it is expressed in two words for the reason that it is a composite form of the future tense.

The 2 situation… I got into trouble doing this job (= difficult). The predicate is expressed in phraseological units.

The 3 situation… Another difficult case is sentences in which a compound predicate is represented by the form of a short participle. Example: The doors are always open.

An error in determining the type of predicate may be associated with an incorrect definition of a part of speech (a short participle should be distinguished from a verb). In fact, in this sentence, the predicate is a compound nominal, and not a simple verb, as it might seem.

Why compound, if expressed in one word? Because in the form of the present tense, the verb has a zero link. If you put the predicate in the form of the past or future tense, then it will manifest itself. Compare. The doors will always be open. The doors were always open.

The 4 situation… A similar error can occur in the case of expressing the nominal part of a compound nominal predicate by a noun or adverb.

Example. Our hut is the second from the edge. (Compare: Our hut was second from the edge).

Dasha is married to Sasha (Compare: Dasha was married to Sasha).

Remember that words are part of the compound predicate you can, you need, you can’t.

Determining the stem in one-part sentences

In nominative sentences, the basis will be presented to the subject.

Example: Winter morning.

In vaguely personal sentences, there is only a predicate. The subject is not expressed, but it is understandable.

Example: I love the storm in early May.

The most difficult case of expressing the stem in impersonal sentences. Most often these are just different types of compound nominal predicates.

Examples: I need to act. The house is warm. I’m upset. There is no comfort, no peace.

If you do not form the skill of determining the basis of a sentence in the lower grades, then this will lead to difficulties in analyzing one-part and complex sentences in grades 8-9. If you gradually develop this skill by the method of complication, then all problems will be resolved.

Source: https://rgiufa.ru/russkij-yazyk/kak-opredelit-grammaticheskuyu-osnovu-predlozheniya.html

Two-part and one-part sentences

One-part sentences are divided into verbal and substantive. In verbal one-part sentences, the main member is the predicate. In substantive one-part sentences, the main member is the subject.

Verb one-part sentences, in turn, are divided into definite personal, indefinite personal and impersonal. Sometimes generalized personal proposals are also singled out.

One-part verbs

1. Definitely personal

A definite personal sentence is a one-part sentence with the main member — a predicate, expressed by a verb in the form of the 1st or 2nd person of the indicative mood or a verb in the form of the imperative mood. The predicate denotes the action of the speaker or his interlocutor.

If you can substitute pronouns in the sentence я, you, we, you and the meaning of this will not change, then this is definitely a personal proposal.

I love to eat delicious food. In this sentence, the predicate is expressed by a verb in the form of the 1st person. You can supplement the sentence with a pronoun я.

Respect cats! In this sentence, the predicate is expressed by a verb in the form of an imperative mood.

Let’s go to Honduras! In this sentence, the predicate is also expressed by a verb in the form of an imperative mood.

2. Vaguely personal

An indefinite personal sentence is a one-piece sentence with a main member — a predicate, which denotes an action or state of an indefinite person. The predicate in such sentences is expressed by a verb in the form of a 3 person plural. numbers in the present or future tense or in the plural form. numbers in the past tense.

You will be paid a scholarship.

The elephant was led along the streets.

3. Impersonal

An impersonal sentence is a one-part sentence with a main member — a predicate, which names an action or state that is presented without the participation of the subject of the action (subject). In such a sentence, there is not and cannot be a subject.

The predicate in such sentences can be expressed:

a) a predicative adverb or a combination of a predicative adverb (must not, can, necessary etc.) and the indefinite form of the verb

You cannot divide by zero.

The cat is bored of being locked up.

It’s cold in the room.

b) an impersonal verb in the form of the 3rd person singular. numbers in the present or future tense or in the form of a neuter singular. numbers in the past tense (or a combination of such a verb and an indefinite verb)

I really want chocolate.

I wanted to go far, far away.

c) a personal verb in an impersonal meaning (for example, when denoting a natural phenomenon or a change in the time of day) in the form of 3 person singular. numbers in the present or future tense or in the form of a neuter singular. numbers in the past tense

After the cancellation of the transition to winter time, it gets dark very early in winter.

d) the indefinite form of the verb

Everybody stand up!

e) word no.

There is no truth on earth. (AS Pushkin. «Mozart and Salieri») In this sentence the predicate is the word no.

4. Generalized personal

A generalized personal sentence is a one-part sentence with a main term — a predicate, the action of which potentially applies to any person.

In form, such proposals are similar to definite personal or vaguely personal.

Tears of sorrow will not help. This proposal in form is definitely personal.

They do not look at a given horse’s teeth. This form proposal is vaguely personal.

Not all linguists distinguish generalized personal sentences in a separate category.

One-piece substantive

The most common type of one-part substantive sentences is nominative sentences.

A nominative sentence is a one-part sentence with a main member — a subject, denoting the presence, existence of an object or phenomenon. The subject in such sentences is expressed by a noun, a personal pronoun, a substantiated part of speech in the form of a nominative case, as well as a quantitative-nominal combination, the main word in which is in the nominative case.

Night, street, lantern, pharmacy, meaningless and dim light. (A. Blok) This is a complex non-union sentence, each part of which is a one-part nominative sentence, and not a simple sentence with four homogeneous subjects.

This is my home.

Source: https://lampa.io/p/двусоставные-и-односоставные-предложения-000000006b15c4d870a5390da5e406b3

Members of the proposal

Articles

- Subject matter

- Predicate

- Definition

- Circumstance

- Addition

Members of the proposal, grammatically significant parts into which the sentence is subdivided during parsing; can consist of both separate words and phrases, i.e. groups of syntactically related words.

The members of the sentence are distinguished not on the basis of their internal structure, but on the basis of the function that they perform as part of larger syntactic units. In a sentence, a group of a subject and a group of a predicate are usually distinguished, connected with each other by a predicative relationship.

The subject and predicate are called the main members of the sentence; in their composition, other members are distinguished, called secondary: definitions, additions, circumstances.

The subject and predicate play the most important role in a sentence.

Subject matter

The subject is usually called a noun (with or without dependent words), which plays the most important grammatical role in a sentence: in Russian it usually stands in the nominative case, the predicate agrees with it, it most often expresses the topic (what is said in the sentence ); only it can correspond to a reflexive or reciprocal pronoun, only the subject can coincide in the main sentence and in the adverbial turnover.

However, there are also such units in which only a part of the listed signs is observed, for example, there is an indirect case (He can’t open the door, I’m cold), lack of agreement with the predicate (And the queen is laughing), difficulty in controlling the adverbial circulation (?Resisting, the offender was killed).

Sometimes the null subject is selected, which controls the agreement with the predicate, but does not have an external expression (At five o’clock in the morning, as always, the rise struck (A.I.Solzhenitsyn); The yard was covered with snow). In some Germanic and Romance languages, the subject must be expressed necessarily, in connection with which the phenomenon of an empty subject is observed, i.e. shaped, but not meaningful: eng.

It is raining «It’s raining», There is a book on the table «There is a book on the table.» Often, subjects are distinguished — subordinate clauses (That he was late — poorly), less often — adverbial groups (From Moscow to Tula near) and other units.

Predicate

Predictable is the part of the sentence that expresses its main content — that which is the subject of a statement (with a greater or lesser degree of certainty), denial or question. The predicate is usually expressed by a verb, sometimes with dependent words (Boy goes to school; I want to get up early), less often — a noun or an adjective with or without a linking verb (He is sick; I was a student).

How to identify types of one-part sentences

Most often, the task B4 of the Unified State Exam in the Russian language involves the ability define the types of one-part sentences. There is a lot of information on this topic — you can find it in school textbooks, various kinds of manuals, etc. And we decided to focus on the most important thing — on what is directly useful for completing the USE tasks in the Russian language.

One-piece sentence differs from two-part, first of all, by the fact that in it not two main members, but only one — subject or predicate. Let’s observe:

Depending on what kind of main member (subject or predicate) is in the sentence, one-part sentences are divided into two groups:

- one-part sentences with a principal subject,

- one-part sentences with a leading predicate.

Let’s consider each of the groups.