When you’re a new teacher, the number of buzzwords that you have to master seems overwhelming at times. You’ve probably heard about many concepts, but you may not be entirely sure what they are or how to use them in your classroom. For example, new teacher Katy B. asks, “This seems like a really basic question, but what are sight words, and where do I find them?” No worries, Katy. We have you covered!

What’s the difference between sight words and high-frequency words?

Oftentimes we use the terms sight words and high-frequency words interchangeably. Opinions differ, but our research shows that there is a difference. High-frequency words are words that are most commonly found in written language. Although some fit standard phonetic patterns, some do not. Sight words are a subset of high-frequency words that do not fit standard phonetic patterns and are therefore not easily decoded.

We use both types of words consistently in spoken and written language, and they also appear in books, including textbooks, and stories. Once students learn to quickly recognize these words, reading comes more easily.

What are sight words and how can I teach my students to memorize them?

Sight words are words like come, does, or who that do not follow the rules of spelling or the six types of syllables. Decoding these words can be very difficult for young learners. The common practice has been to teach students to memorize these words as a whole, by sight, so that they can recognize them immediately (within three seconds) and read them without having to use decoding skills.

Can I teach sight words using the science of reading?

On the other hand, recent findings based on the science of reading suggests we can use strategies beyond rote memorization. According to the the science of reading, it is possible to sound out many sight words because they have recognizable patterns. Literacy specialist Susan Jones, a proponent of using the science of reading to teach sight words, recommends a method called phoneme-grapheme mapping where students first map out the sounds they hear in a word and then add graphemes (letters) they hear for each sound.

How else can I teach sight words?

There are many fun and engaging ways to teach sight words. Dozens of books on the subject have been published, including the much-revered Comprehensive Phonics, Spelling, and Word Study Guide by Fountas & Pinnell. Also, resources like games, manipulatives, and flash cards are readily available online and in stores. To help get you started, check out these Creative and Simple Sight Word Activities for the Classroom. Also, check out Susan Jones Teaching for three science-of-reading-based ideas and more.

Where do I find sight word lists?

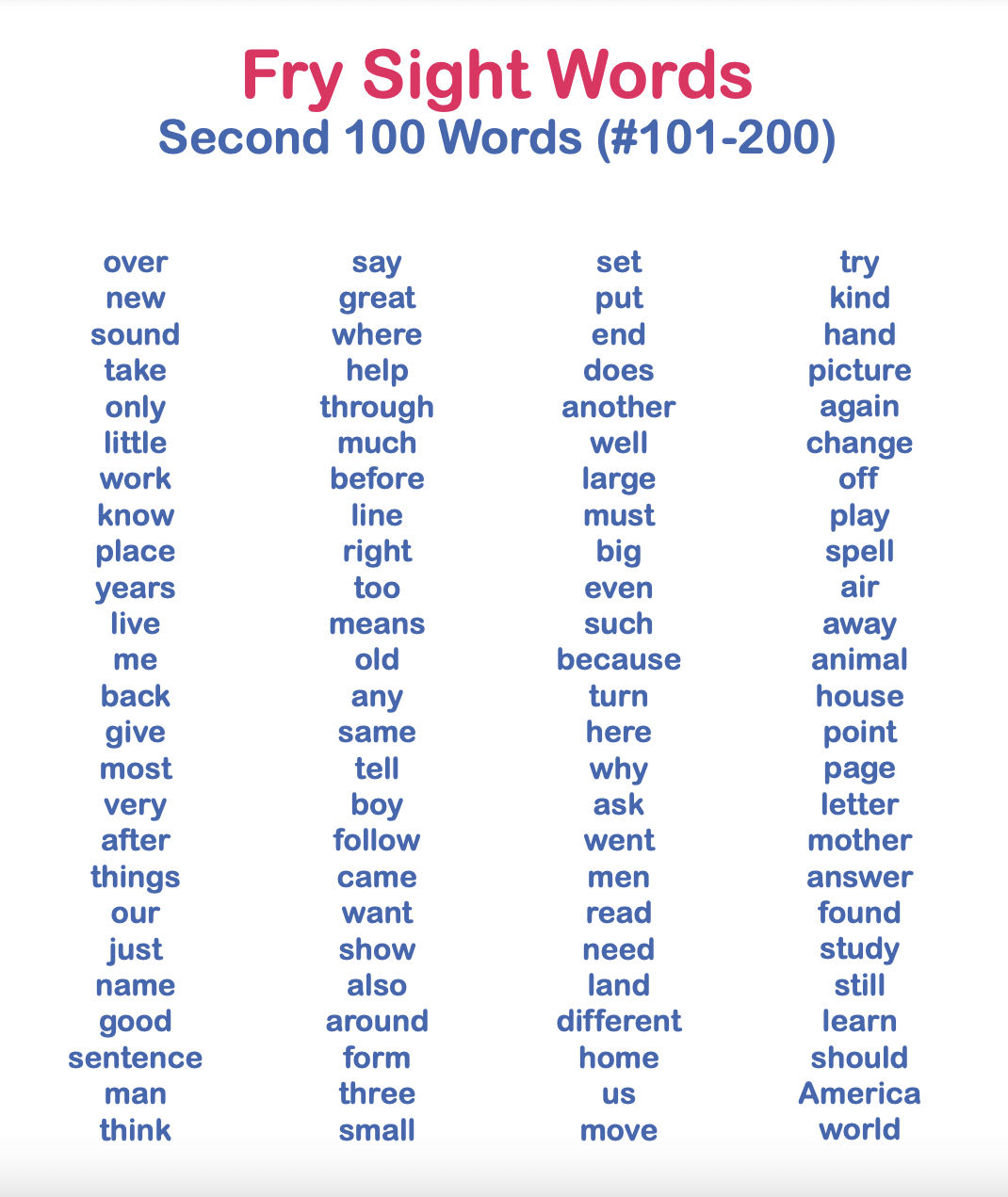

Two of the most popular sources are the Dolch High Frequency Words list and the Fry High Frequency Words list.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Dr. Edward Dolch developed his word list, used for pre-K through third grade, by studying the most frequently occurring words in the children’s books of that era. The list has 200 “service words” and also 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch word list comprises 80 percent of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50 percent of the words found in writing for adults.

Dr. Edward Fry developed an expanded word list for grades 1–10 in the 1950s (updated in 1980), based on the most common words that appear in reading materials used in grades 3–9. The Fry list contains the most common 1,000 words in the English language. The Fry words include 90 percent of the words found in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

Looking for more sight word activities? Check out 20 Fun Phonics Activities and Games for Early Readers.

Want more articles like this? Be sure to sign up for our newsletters.

Overview

Learn the history behind Dolch and Fry sight words, and why they are important in developing fluent readers.

More

Lessons

Follow the sight words teaching techniques. Learn research-validated and classroom-proven ways to introduce words, reinforce learning, and correct mistakes.

More

Flash Cards

Print your own sight words flash cards. Create a set of Dolch or Fry sight words flash cards, or use your own custom set of words.

More

Games

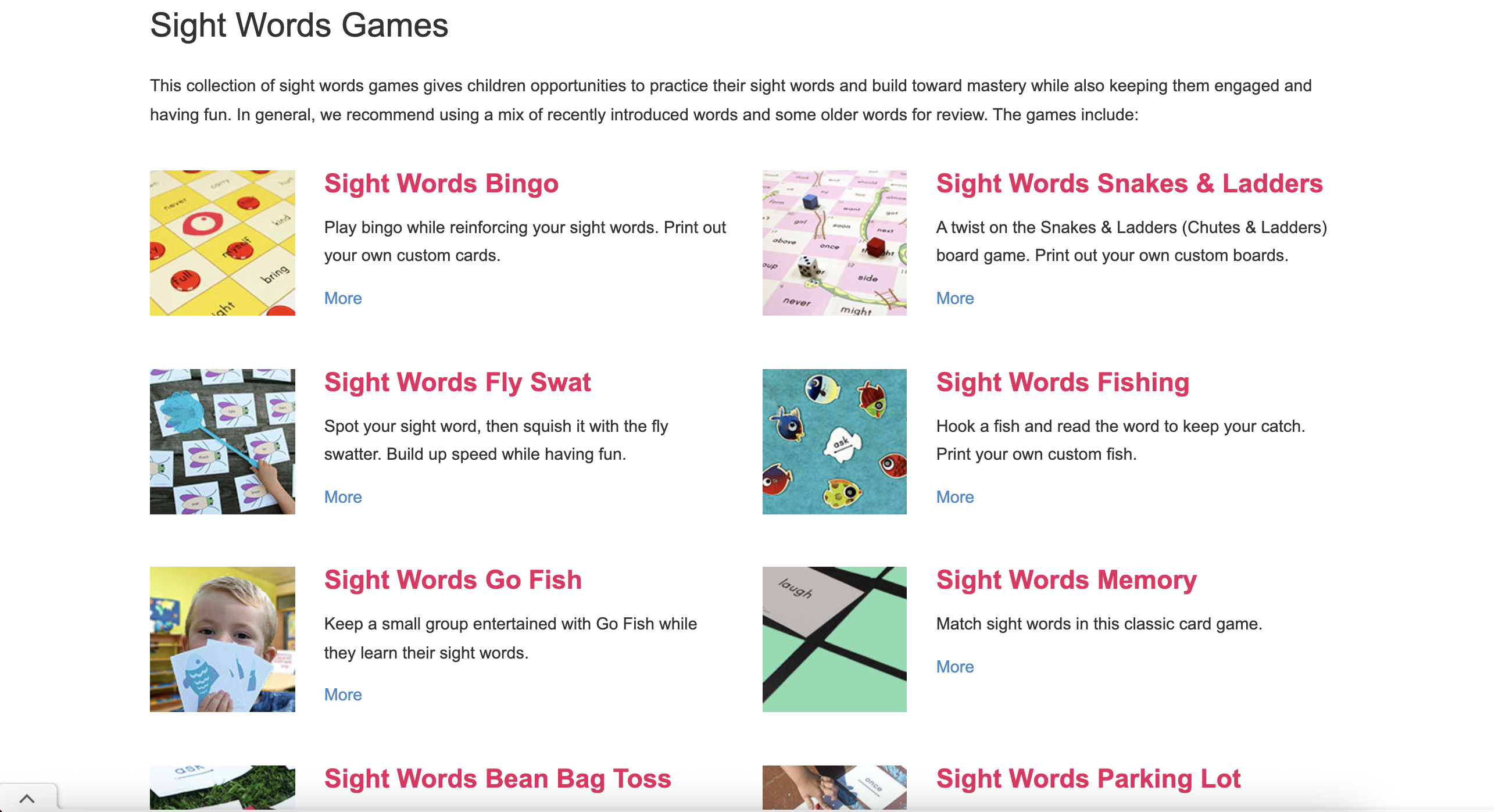

Play sight words games. Make games that create fun opportunities for repetition and reinforcement of the lessons.

More

- Overview

- What Are Sight Words?

- Types of Sight Words

- When to Start

- Scaling & Scaffolding

- Research

- Questions and Answers

1. Overview

Sight words instruction is an excellent supplement to phonics instruction. Phonics is a method for learning to read in general, while sight words instruction increases a child’s familiarity with the high frequency words he will encounter most often.

The best way to learn sight words is through lots and lots of repetition, in the form of flashcard exercises and word-focused games.

↑ Top

2. What Are Sight Words?

Sight words are words that should be memorized to help a child learn to read and write. Learning sight words allows a child to recognize these words at a glance — on sight — without needing to break the words down into their individual letters and is the way strong readers recognize most words. Knowing common, or high frequency, words by sight makes reading easier and faster, because the reader does not need to stop to try and sound out each individual word, letter by letter.

Sight Words are memorized so that a child can recognize commonly used or phonetically irregular words at a glance, without needing to go letter-by-letter.

Other terms used to describe sight words include: service words, instant words (because you should recognize them instantly), snap words (because you should know them in a snap), and high frequency words. You will also hear them referred to as Dolch words or Fry words, the two most commonly used sight words lists.

Sight words are the glue that holds sentences together.

These pages contain resources to teach sight words, including: sight words flash cards, lessons, and games. If you are new to sight words, start with the teaching strategies to get a road map for teaching the material, showing you how to sequence the lessons and activities.

↑ Top

3. Types of Sight Words

Sight words fall into two categories:

- Frequently Used Words — Words that occur commonly in the English language, such as it, can, and will. Memorizing these words makes reading much easier and smoother, because the child already recognizes most of the words and can concentrate their efforts on new words. For example, knowing just the Dolch Sight Words would enable you to read about 50% of a newspaper or 80% of a children’s book.

- Non-Phonetic Words — Words that cannot be decoded phonetically, such as buy, talk, or come. Memorizing these words with unnatural spellings and pronunciations teaches not only these words but also helps the reader recognize similar words, such as guy, walk, or some.

There are several lists of sight words that are in common use, such as Dolch, Fry, Top 150, and Core Curriculum. There is a great deal of overlap among the lists, but the Dolch sight word list is the most popular and widely used.

3.1 Dolch Sight Words

The Dolch Sight Words list is the most commonly used set of sight words. Educator Dr. Edward William Dolch developed the list in the 1930s-40s by studying the most frequently occurring words in children’s books of that era. The list contains 220 “service words” plus 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch sight words comprise 80% of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50% of the words found in writing for adults. Once a child knows the Dolch words, it makes reading much easier, because the child can then focus his or her attention on the remaining words.

More

3.2 Fry Sight Words

The Fry Sight Words list is a more modern list of words, and was extended to capture the most common 1,000 words. Dr. Edward Fry developed this expanded list in the 1950s (and updated it in 1980), based on the most common words to appear in reading materials used in Grades 3-9. Learning all 1,000 words in the Fry sight word list would equip a child to read about 90% of the words in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

More

3.3 Top 150 Written Words

The Top 150 Written Words is the newest of the word lists featured on our site, and is commonly used by people who are learning to read English as a non-native language. This list consists of the 150 words that occur most frequently in printed English, according to the Word Frequency Book. This list is recommended by Sally E. Shaywitz, M.D., Professor of Learning Development at Yale University’s School of Medicine.

More

3.4 Other Sight Words Lists

There are many newer variations, such as the Common Core sight words, that tweak the Dolch and Fry sight words lists to find the combination of words that is the most beneficial for reading development. Many teachers take existing sight word lists and customize them, adding words from their own classroom lessons.

↑ Top

4. When to Start Teaching Sight Words

Before a child starts learning sight words, it is important that he/she be able to recognize and name all the lower-case letters of the alphabet. When prompted with a letter, the child should be able to name the letter quickly and confidently. Note that, different from learning phonics, the child does not need to know the letters’ sounds.

Before starting sight words, a child needs to be able to recognize and name all the lower-case letters of the alphabet.

If a student’s knowledge of letter names is still shaky, it is important to spend time practicing this skill before jumping into sight words. Having a solid foundation in the ability to instantly recognize and name the alphabet letters will make teaching sight words easier and more meaningful for the child.

Go to our Lessons for proven strategies on how to teach and practice sight words with your child.

↑ Top

5. Scaling & Scaffolding

Every child is unique and will learn sight words at a different rate. A teacher may have a wide range of skill levels in the same classroom. Many of our sight words games can be adjusted to suit different skill levels.

Many of our activity pages feature recommendations for adjusting the game to the needs of your particular child or classroom:

- Confidence Builders suggest ways to simplify a sight words game for a struggling student.

- Extensions offer tips for a child who loves playing a particular game but needs to be challenged more.

- Variations suggest ways to change up the game a little, by tailoring it to a child’s special interests or making it “portable.”

- Small Group Adaptations offer ideas for scaling up from an individual child to a small group (2-5 children), ensuring that every child is engaged and learning.

↑ Top

6. Research

Our sight words teaching techniques are based not only on classroom experience but also on the latest in child literacy research. Here is a bibliography of some of the research supporting our approach to sight words instruction:

- Ceprano, M. A. “A review of selected research on methods of teaching sight words.” The Reading Teacher 35:3 (1981): 314-322.

- Ehri, Linnea C. “Grapheme–Phoneme Knowledge Is Essential for Learning to Read Words in English.” Word Recognition in Beginning Literacy. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1998.

- Enfield, Mary Lee, and Victoria Greene. Project Read. www.projectread.com. 1969.

- Gillingham, Anna, and Bessie W. Stillman. The Gillingham Manual: Remedial Training for Students with Specific Disability in Reading, Spelling, and Penmanship, 8th edition. Cambridge, MA: Educators Publishing Service, 2014.

- Nist, Lindsay, and Laurice M. Joseph. “Effectiveness and Efficiency of Flashcard Drill Instructional Methods on Urban First-Graders’ Word Recognition, Acquisition, Maintenance, and Generalization.” School Psychology Review 37:3 (Fall 2008): 294-308.

- Shaywitz, Sally E. Overcoming Dyslexia: A New and Complete Science-Based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

- Stoner, J.C. “Teaching at-risk students to read using specialized techniques in the regular classroom.” Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3 (1991).

- Wilson, Barbara A. “The Wilson Reading Method.” Learning Disabilities Journal 8:1 (February 1998): 12-13.

- Wilson, Barbara A. Wilson Reading System. Millbury, MA: Wilson Language Training, 1988.

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

Recent Blog Posts

Case Wars: Upper vs. Lower Case Letters

September 27, 2016

Some of our visitors ask us why all our materials are printed in lower-case letters as opposed to upper-case letters. We know that many preschool and kindergarten teachers focus on teaching upper-case letters first. The ability to recognize lower-case letters … Continued

Is It Dyslexia?

August 29, 2016

We sometimes get questions from SightWords.com visitors who are concerned that their child or grandchild may have a learning disability. Of particular concern is the possibility that their child might have dyslexia. Many people assume that dyslexia is a visual … Continued

SightWords.com at the Southeast Homeschool Expo

August 10, 2016

On July 29th and 30th, board members of the Georgia Preschool Association met at the Cobb Galleria Centre just outside Atlanta to attend the Southeast Homeschool Expo, a convention for homeschooling families and resource providers from across the Southeastern U.S. … Continued

© 2023 Sight Words: Teach Your Child to Read

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

High frequency sight words (also known simply as sight words) are commonly used words that young children are encouraged to memorize as a whole by sight, so that they can automatically recognize these words in print without having to use any strategies to decode.[1] Sight words were introduced after whole language (a similar method) fell out of favor with the education establishment.[2]

The term sight words is often confused with sight vocabulary, which is defined as each person’s own vocabulary that the person recognizes from memory without the need to decode for understanding.[3][1]

However, some researchers say that two of the most significant problems with sight words are: (1) memorizing sight words is labour intensive, requiring on average about 35 trials per word,[4] and (2) teachers who withhold phonics instruction and instead rely on teaching sight words are making it harder for children to «gain basic word-recognition skills» that are critically needed by the end of grade three and can be used over a lifetime of reading.[5]

Rationale[edit]

Sight words account for a large percentage (up to 75%) of the words used in beginning children’s print materials.[6][7] The advantage for children being able to recognize sight words automatically is that a beginning reader will be able to identify the majority of words in a beginning text before they even attempt to read it; therefore, allowing the child to concentrate on meaning and comprehension as they read without having to stop and decode every single word.[6] Advocates of whole-word instruction believe that being able to recognize a large number of sight words gives students a better start to learning to read.

Recognizing sight words automatically is said to be advantageous for beginning readers because many of these words have unusual spelling patterns, cannot be sounded out using basic phonics knowledge and cannot be represented using pictures.[8] For example, the word «was» does not follow a usual spelling pattern, as the middle letter «a» makes an /ɒ~ʌ/ sound and the final letter «s» makes a /z/ sound, nor can the word be associated with a picture clue since it denotes an abstract state (existence). Another example, is the word «said», it breaks the phonetic rule of ai normally makes the long a sound, ay. In this word it makes the short e sound of eh.[9] The word «said» is pronounced as /s/ /e/ /d/. The word «has» also breaks the phonetic rule of s normally making the sss sound, in this word the s makes the z sound, /z/.» The word is then pronounced /h/ /a/ /z/.[9]

However, a 2017 study in England compared teaching with phonics vs. teaching whole written words and concluded that phonics is more effective, saying «our findings suggest that interventions aiming to improve the accuracy of reading aloud and/or comprehension in the early stages of learning should focus on the systematicities present in print-to-sound relationships, rather than attempting to teach direct access to the meanings of whole written words».[10]

Most advocates of sight-words believe children should memorize the words. However, some educators say a more efficient method is to teach them by using an explicit phonics approach, perhaps by using a tool such as Elkonin boxes. As a result, the words form part of the students sight vocabulary, are readily accessible and aid in learning other words containing similar sounds.[11][12]

Other phonics advocates, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI-USA), the Departments of Education in England, and the State of Victoria in Australia, recommend that teachers first begin by teaching children the frequent sounds and the simple spellings, then introduce the less frequent sounds and more complex spellings later (e.g. the sounds /s/ and /t/ before /v/ and /w/; and the spellings cake before eight and cat before duck).[13][14][15][16] The following are samples of the lists that are available on the CCSSI-USA site:[17]

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Consonants) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /m/ | mitt, comb, hymn | m, mb, mn |

| /t/ | tickle, mitt, sipped | t, tt, ed |

| /n/ | nice, knight, gnat | n, kn, gn |

| /k/ | cup, kite, duck, chorus, folk, quiet | k, c, ck, ch, lk, q |

| /f/ | fluff, sphere, tough, calf | f, ff, gh, ph, lf |

| /s/ | sit, pass, science, psychic | s, ss, sc, ps |

| /z/ | zoo, jazz, nose, as, xylophone | z, zz, se, s, x |

| /sh/ | shoe, mission, sure, charade, precious, notion, mission, special | sh, ss, s, ch, sc, ti, si, ci |

| /zh/ | measure, azure | s, z |

| /r/ | reach, wrap, her, fur, stir | r, wr, er/ur/ir |

| /h/ | house, whole | h, wh |

| Phoneme | Sample only — Word Examples (Vowels) (CCSSI-USA) | Common Graphemes (Spellings) |

|---|---|---|

| /ā/ | make, rain, play, great, baby, eight, vein, they | a_e, ai, ay, ea, -y, eigh, ei, ey |

| /ē/ | see, these, me, eat, key, happy, chief, either | ee, e_e, -e, ea, ey, -y, ie, ei |

| /ī/ | time, pie, cry, right, rifle | i_e, ie, -y, igh, -I |

| /ō/ | vote, boat, toe, snow, open | o_e, oa, oe, ow, o- |

| /ū/ | use, few, cute | u, ew, u_e |

| /ă/ | cat | a |

| /ĕ/ | bed, breath | e, ea |

| /ĭ/ | sit, gym | i, y |

| /ŏ/ | fox, swap, palm | o, (w)a, al |

| /ŭ/ | cup, cover, flood, tough | u, o, oo, ou |

| /aw/ | saw, pause, call, water, bought | aw, au, al, (w)a, ough |

| /er/ | her, fur, sir | er, ur, ir |

Word lists[edit]

A number of sight word lists have been compiled and published; among the most popular are the Dolch sight words[18] (first published in 1936) and the 1000 Instant Word list prepared in 1979 by Edward Fry, professor of Education and Director of the Reading Center at Rutgers University and Loyola University in Los Angeles.[19][20][21][22] Many commercial products are also available. These lists have similar attributes, as they all aim to divide words into levels which are prioritized and introduced to children according to frequency of appearance in beginning readers’ texts. Although many of the lists have overlapping content, the order of frequency of sight words varies and can be disputed, as they depend on contexts such as geographical location, empirical data, samples used, and year of publication.[23]

Criticism[edit]

Research shows that the alphabetic principle is seen as «the primary driver» of development of all aspects of printed word recognition including phonic rules and sight vocabulary.»[24] In addition, the use of sight words as a reading instructional strategy is not consistent with the dual route theory as it involves out-of-context memorization rather than the development of phonological skills.[25] Instead, it is suggested that children first learn to identify individual letter-sound correspondences before blending and segmenting letter combinations.[26][27]

Proponents of systematic phonics and synthetic phonics argue that children must first learn to associate the sounds of their language with the letter(s) that are used to represent them, and then to blends those sounds into words, and that children should never memorize words as visual designs.[28] Using sight words as a method of teaching reading in English is seen as being at odds with the alphabetic principle and treating English as though it was a logographic language (e.g. Chinese or Japanese).[29]

Some notable researchers have clearly stated their disapproval of whole language and whole-word teaching. In his 2009 book, Reading in the brain, French cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene wrote, «cognitive psychology directly refutes any notion of teaching via a ‘global’ or ‘whole language’ method.» He goes on to talk about «the myth of whole-word reading», saying it has been refuted by recent experiments. «We do not recognize a printed word through a holistic grasping of its contours, because our brain breaks it down into letters and graphemes.»[30] Another cognitive neuroscientist, Mark Seidenberg, says that learning to sound-out atypical words such as have (/h/-/a/-/v/) helps the student to read other words such as had, has, having, hive, haven’t, etc. because of the sounds they have in common.[31]

See also[edit]

- Dolch word list

- Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud

- Fry readability formula

- Learning to read

- Literacy

- Most common words in English

- Phonics

- Reading comprehension

- Reading education in the United States

- Reading (process)

- Subvocalization

- Teaching reading: whole language and phonics

- Whole language

- Writing system

References[edit]

- ^ a b «What Are Sight Words?». WeAreTeachers. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Ravitch, Diane. (2007). EdSpeak: A Glossary of Education Terms, Phrases, Buzzwords, and Jargon. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, ISBN 1416605754.

- ^ Rapp, S. (1999-09-29). Recognizing words on sight; activity. The Baltimore Sun

- ^ Murray, Bruce; McIlwain, Jane (2019). «How do beginners learn to read irregular words as sight words». Journal of Research in Reading. 42 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1111/1467-9817.12250. ISSN 0141-0423. S2CID 150055551.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of sight. New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-5416-1715-5.

- ^ a b Kear, D. J., & Gladhart, M. A. (1983). «Comparative Study to Identify High-Frequency Words in Printed Materials». Perceptual and Motor Skills. 57 (3): 807–810. doi:10.2466/pms.1983.57.3.807. S2CID 144675331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Teaching Sight Words as a Part of Comprehensive Reading Instruction, Iowa reading research centre, 2018-06-12».

- ^ «Phonological Ability», The SAGE Encyclopedia of Contemporary Early Childhood Education, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2016, doi:10.4135/9781483340333.n296, ISBN 9781483340357

- ^ a b «Sight Words». www.thephonicspage.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Taylor, J. S. H.; Davis, Matthew H.; Rastle, Kathleen (2017). «Comparing and Validating Methods of Reading Instruction Using Behavioural and Neural Findings in an Artificial Orthography» (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, volume 146, No. 6, 826–858. 146 (6): 826–858. doi:10.1037/xge0000301. PMC 5458780. PMID 28425742.

- ^ «Sight Words: An Evidence-Based Literacy Strategy, Understood.org».

- ^ «A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words, reading rockets.org». 6 June 2019.

- ^ «Complete report — National Reading Panel, England» (PDF).

- ^ «Sample phonics lessons, The State Government of Victoria».

- ^ «Foundation skills, The State Government of Victoria, AU».

- ^ «English Appendix 1: Spelling, Government of England» (PDF).

- ^ «Common Core Standards, Appendix A, USA» (PDF).

- ^ «Dolch Words 220, Utah Education Network in partnership with the Utah State Board of Education and Utah System of Higher Education» (PDF).

- ^ Edward Fry (1979). 1000 Instant Words: The Most Common Words for Teaching Reading, Writing, and Spelling. ISBN 0809208806.

- ^ «McGraw-Hill Education Acknowledges Enduring Contributions of Reading and Language Arts Scholar, Author and Innovator Ed Fry, McGraw-Hill Education, Sep 15, 2010».

- ^ «Edward B. Fry, PH.D, Published in Los Angeles Times on Sep. 12, 2010». Legacy.com.

- ^ «Fry Instant Words, UTAH EDUCATION NETWORK».

- ^ Otto, W. & cester, R. (1972). «Sight words for beginning readers». The Journal of Educational Research. 65 (10): 435–443. doi:10.1080/00220671.1972.10884372. JSTOR /27536333.

- ^ «Independent Review of the Primary Curriculum: Final Report, page 87» (PDF).

- ^ Ehri, Linnea C. (2017). «Reconceptualizing the Development of Sight Word Reading and Its Relationship to Recoding». Reading Acquisition. London: Routledge. pp. 107–143. ISBN 9781351236898.

- ^ Literacy teaching guide : phonics. New South Wales. Department of Education and Training. [Sydney, N.S.W.]: New South Wales Dept. of Education and Training. 2009. ISBN 9780731386093. OCLC 590631697.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Findings and Determinations of the National Reading Panel by Topic Areas

- ^ McGuinness, Diane (1997). Why Our Children Can’t Read. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0684831619.

- ^ Gatto, John Taylor (2006). «Eyless in Gaza». The Underground History of American Education. Oxford, NY: The Oxford Village Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0945700040.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010-10-26). Reading in the brain. Penquin Books. pp. 222–228. ISBN 9780143118053.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of light. pp. 143–144=author=Mark Seidenberg. ISBN 9780465080656.

Like many families this week, your children are heading back to the classroom and coming home with a worksheet or two of homework. (Make that dozens of worksheets for your older kids!) The homework that caught my eye this week is the list of “sight words.” What are sight words? Sight words (high-frequency words, core words or even popcorn words) are the words that are used most often in reading and writing. According to Teach Stix:

In classrooms across America, the development of sight word recognition continues to be a top priority when instructing emerging and beginning readers.

They are called “sight” words because the goal is for your child to recognize these words instantly, at first sight.

Why are Sight Words Important?

Sight words are very important for your child to master because, believe it or not, “sight words account for up to 75% of the words used in beginning children’s printed material”, according to Study to Identify High-Frequency Words in Printed Materials, by D.J. Kear & M.A. Gladhart. There are different sight words for every grade level. Each set of words builds upon the other, meaning that once your child learns the sight words in Kindergarten, he will be expected to still recognize those words as he learns new words in first grade, and so forth.

Many of the over 200 “sight words” do not follow the basic phonics principles, thus they cannot be “sounded out.” Beginning readers need an effective strategy for decoding unknown words, and being familiar with sight words is an effective method. Other benefits of sight words include:

- Sight words promote confidence. Because the first 100 sight words represent over 50% of English text, a child who has mastered the list of sight words can already recognize at least half of a sentence. If your child begins to read a book and can already recognize the words, chances are he won’t feel discouraged and put the book down, rather he’ll have more confidence to read it all the way through. And, choose another!

- Sight words help promote reading comprehension. When your child opens her book for the first time, instead of trying to decipher what ALL of the words mean, she can shift her attention to focus on those words she is not familiar with. She will already know at least half of the words, so focusing on the other half helps strengthen her understanding of the text.

- Sight words provide clues to the context of the text. If your child is familiar with the sight words, she may be able to decode the meaning of the paragraph or sentence by reading the sight words. And, if a picture accompanies the text, your child may be able to determine what the story is about and come away with a few new words under her belt.

How to Practice Sight Words

You will want to become familiar with all of the sight words for each grade. Both the Dolch List of Basic Sight Words and Fry’s 300 Instant Sight Words, each of which can be downloaded from the Literacy and Information Communication System (LINCS) website. The key to mastering the list of sight words? Practice and repeat! The more opportunity your child has to become familiar with these words, the better. Of course, you’ll see sight words come home in the homework folder, or you may even be asked by the teacher to use flashcards, but there are many FUN activities and games that you can do together to help promote learning of the sight words.

Educational website, Ed Helper has an extensive collection of printables and worksheets designed to help kids conquer their list of sight words. Even Pinterest has jumped aboard with creative ideas to help your child work on sight words. There is an entire Pinterest site dedicated to sight word activities for your kids! Think Skittles, snowballs, chalkboards…the choices are endless! Take a look!

Creative Ways to Conquer Sight Words. Pinned Image from teacherspayteachers.com

Sight words help your child build a foundation for reading comprehension and fluency. How about using online tools to help perfect those words? Most kids will welcome the chance to “play” online, even if it is educational. Our new Bitsboard app is a great way to target certain sounds and sight words in an engaging way. Enjoy!

Language Development

If you’ve been teaching reading for a while, you’ve undoubtedly come across the term sight words, and you probably have some questions about them. Should you teach sight words? What’s the best way to approach sight words? Is it bad to use a curriculum that teaches sight words?

In fact, a common question we get is, “Do you teach sight words in the All About Reading program? ” But before we jump into the details, let’s be sure we’re talking about the same definition for the term sight words.

Our Working Definition of Sight Word

At its most basic–and this is what we mean when we talk about sight words–a sight word is a word that can be read instantly, without conscious attention.

For example, if you see the word peanut and recognize it instantly, peanut is a sight word for you. You just see the word and can read it right away without having to sound it out. In fact, if you are a fluent reader, chances are you don’t need to stop to decode words as you read this blog post because every word in this post is a sight word for you.

But there are three other commonly used definitions for sight words that you should be aware of:

- Irregular words that can’t be decoded using phonics and must be memorized, such as of, could, and said.

- The “whole word” or “look-say” approach to teaching reading, also known as the “sight word approach.” This approach is the opposite of phonics, and words are memorized as a whole.

- Words that appear on high-frequency word lists such as the popular Dolch Sight Word and Fry’s Instant Word lists. (Many educators believe that the words on these lists must be learned through rote memorization, but we bust that myth in this video.)

So now you can see why sight words can cause so much angst! Educators have conflicting ideas about sight words and how to teach them, and in large part that stems from having different definitions for what sight words are.

But you are in safe territory here.

In this article, you’ll find out how to minimize the number of sight words that your child needs to memorize, while maximizing his ability to successfully master these words.

How Fast Is “Instant”?

Now that we’ve settled on the definition for sight words as “any words that can be read instantly, without conscious attention,” that may lead some people to wonder how fast is “instant”? And that’s a great question!

Basically, we want kids to see a word and be unable to not read it. Even before they’ve realized that they are looking at the word, they’ve unconsciously read it.

Here’s a demonstration of what I mean.

(Download this PDF if you want to try this experiment with your family and friends!)

As explained in the short video above, the Stroop effect1 shows that word recognition can be even more automatic than something as basic as color recognition.

So that’s what we mean by “instant.”

We want children to develop automaticity when reading, so they don’t even have to think about decoding words—they just automatically know the words. Ideally, we want reading to become as effortless and unconscious as breathing.

But what about words that aren’t as easily decoded? How should those words be taught?

Some Words Need to Be Learned Through Rote Memorization

The vast majority of words don’t need to be taught by rote memorization. Even the Dolch Sight Word list is mostly decodable (video). But there are some words that do need to be memorized.

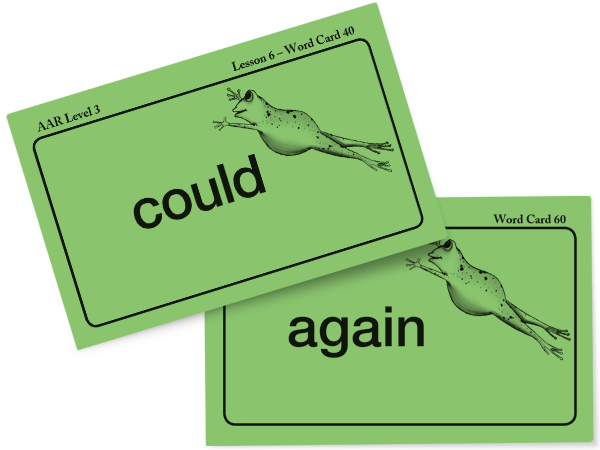

Some programs call these “Red Words,” “Outlaw Words,” “Sight Words,” or “Watch-Out” words. In All About Reading, we call them Leap Words. Generally, these are high-frequency words that either don’t follow the normal phonetic patterns or contain phonograms that students haven’t practiced yet. Students “leap ahead” to learn these words as sight words.

Here’s an example of two flashcards used to practice the Leap Words could and again. In the word could, the L isn’t pronounced. In the word again, the AI says /ĕ/, which isn’t one of its typical sounds. The frog graphic acts as a visual reminder that the words are being treated as sight words that need to be memorized.

Leap Words comprise a small percentage of words taught. For example, out of the 200 words taught in All About Reading Level 1, only 11 are Leap Words.

Several techniques are used to help your student remember the Leap Words:

- Leap Word Cards are kept behind the Review divider in your student’s Reading Review Box until your student has achieved instant recognition of the word.

- Leap Words frequently appear on the Practice Sheets.

- Leap Words are used frequently in the decodable readers.

- If a Leap Word causes your student trouble, have your student use a light-colored crayon to circle the part of the word that doesn’t say what your student expects it to say.

- Help your student see that Leap Words generally have just one or two letters that are troublesome, while the rest of the letters say their regular sounds and follow normal patterns.

For typical students who do not struggle with reading, very little practice is needed to move a word into long-term memory. They may encounter the word just one to five times, and never have to sound it out again.

On the other hand, a struggling reader may need up to thirty exposures to a word before it becomes part of the child’s sight word vocabulary. So be patient and give your child the amount of practice she needs to develop a large sight word vocabulary.

Here Are 5 More Ways to Increase Your Child’s Sight Word Vocabulary

These five methods increase the number of times your child encounters a word, helping move the word into long-term memory for instant recall:

- Make use of interesting games and activities (such as Over Easy, Hatch the Turtles, and Pack Your Suitcase).

- Have your child read decodable books.

- Encourage your child to “sound out” phonetically-regular words.

- Use sentence dictation to encourage extra practice.

- Review Word Cards frequently until they are mastered.

The Bottom Line on Teaching Sight Words

When it comes to teaching sight words, here’s what you need to keep in mind:

- The goal of teaching sight words is to allow your child to read easily and fluently, without conscious attention.

- Some words—we call them Leap Words—can’t be decoded as easily and must be learned through rote memorization.

- Increasing the number of times a child encounters a word helps move the word into the child’s long-term memory.

Are you looking for a reading program that doesn’t involve memorizing hundreds of sight words via rote memorization? All About Reading is a research-based program that walks you through all the steps to help your child achieve instant recall. And if you ever need a hand, we’re here to help.

What’s your take on teaching sight words? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

___________________________________

1Stroop, J.R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643-662.

The term «sight word» has different meanings depending upon one’s philosophy of reading instruction. In today’s public schools, though, if your child brings home a list of words with «Sight Words» printed at the top of it, you can bet that the teacher wants your child to memorize every word on the list.

More than likely it’s a list of short, high-frequency words, that is, words that appear very often in print. The prime justification for such a list is that a lot of the words cannot be easily decoded by a child. They are considered «phonetically irregular,» or «difficult to sound out,» or some other similar term. Your child is being told that he has to just learn to say those words quickly, i.e., «on sight,» and the technique for learning them is usually by rote memorization, without considering the phonics information contained in the word.

The Problem: Every Word is a Sight Word

The main sight word lists circulating today were put together years ago by people who advocated a whole-word memorization approach to reading instruction. Just memorize every word you encounter and you’ll be a great reader. The advocates of whole-word instruction have always criticized phonics programs for slowing children down, that is, for forcing them to «laboriously» (a favorite word) decode each and every word accurately, a process that «hinders» (another favorite word) their comprehension of the story they’re reading.

But they’re wrong on every count. Memorizing even a dozen words is difficult without utilizing the phonics information that virtually every English word possesses. Phonics advocates don’t intend each word to be sounded out «laboriously» every time it’s encountered; they expect a child to learn the word, and to base that learning on the phonetic structure of the word. Once learned, it becomes what even whole-word advocates would consider a sight word, i.e., the child knows it on sight, without having to decode it.

As for whether the process is «laborious» or not, rote memorization of hundreds of words is just a prelude to rote memorization of thousands of words. If you don’t teach a child a strategy for decoding «sight words» like go and to, then how are they to ever develop a strategy for decoding government or together? Hint: These are the programs that tell a child to look for words within the word (like the to, get and her in together perhaps), and that then teach your child to recognize common prefixes and suffixes. Just memorize enough components and put them together becomes the strategy. Oh, and once you’ve figured a word out, memorize it so you don’t have to go through that process again.

Earlier, I said they’re wrong on every count. They are. They’re wrong about whether it’s easier to learn to read a word on sight by memorizing it, or by first analyzing its phonetic structure. They’re also wrong about whether it hinders comprehension for children taught by whole-word methods are continually misreading similar words whereas the children familiar with phonics easily comprehend which word is which. Does your child confuse that with what, or there with where? That’s the expected result of whole-word instruction via sight word lists.

They’re also wrong about the process being «laborious.» It’s the whole-word reader who hits a wall in 2nd or 3rd grade when the number of words that require memorization finally exceeds their memory capacity. From that point on, many just guess at unfamiliar words, filling in something that seems to fit the context. Within the context of a story, house and home are interchangeable; without context, so are house and horse. Inside the word, the letters just don’t matter much. After all, they weren’t taught to use them.

What Do You Do When that First Sight-Word List Comes Home?

Well, you might consider using the list to teach the phonics code. To do that, just use the OnTrack Reading Phonogram Set. It’s available here as a set of flash cards.

To illustrate, I’ll use the first 10 words of the Ayres List. They are me, do, and, go, at, on, a, it, is, and she. Each of these is on one of the first few sight word lists your child will bring home.

me: (/m/ee/) Take cards number 16 (m) and 10 (e) and teach their content. Chances are your child already knows the sound of the phonogram m, and might even know the /e/ sound for the phonogram e. Just teach him that the phonogram e is /e/ee/. Then show him me and write a 2 over the e. Then have him write me, saying /m/ as he writes the m and /ee/ as he writes the e. If he can’t remember how to spell the /ee/ sound, tell him that in the word me, he should use the phonogram he learned as /e/ee/. When he’s written me, have him put a 2 over the e to remind him its the second sound of the phonogram e.

do: (/d/oo/) Take cards number 18 (p) and 6 (o) and again teach their content. It might take a few attempts to teach the three sounds of the phonogram o, but the effort will pay off handsomely in the end. Once your child can respond /o/oe/oo/ when seeing the phonogram o, show him do and write the number 3 over the o to designate the third sound, /oo/. Then, as before, have him spell do, saying each sound as he writes each phonogram. If he needs it, tell him to use the phonogram for /oo/ that he just learned as /o/oe/oo/ and again have him put a 3 over the phonogram o to indicate that he used the third sound when spelling do.

and: (/a/n/d/) Take cards number 1 (a) and 17 (n) and teach their sounds. Your child might already know the first sound of both phonograms, but teach them anyway. Then show him and while pointing out that the /a/ sound is spelled with the phonogram he learned as /a/ae/o/, the second is spelled with the phonogram he learned as /n/ng/, and the last is spelled with the phonogram he learned as /d/. Add that no numbers are needed because he used the first sound of every phonogram.

go: (/g/oe/) Get card number 5 (g) and teach it’s two sounds, /g/j/. He might already know that it’s /g/, but make sure he knows both sounds. Then show him go and write a 2 above the o and tell him we use the phonogram /o/oe/oo/ when spelling go. Repeat the process of having him spell the word go himself and putting the number 2 above the phonogram o.

at: (/a/t/) Get card number 20 (t) and make sure your child knows it as the /t/ sound. The show him at and explain that it uses the the /a/ae/o/ phonogram to spell /a/, and the /t/ phonogram to spell /t/. Because only the first sounds of the phonograms are used, no numbers are needed. Repeat the spelling process described for the earlier words.

on: (o/n) Get no new cards. This is where the payoff begins. Just write on and tell him we use the phonogram for /o/oe/oo/ to write the /o/ sound and the phonogram for /n/ng/ to write the /n/ sound. They’re both first sounds of the phonogram, so no numbers are needed. Have him spell on, making sure he’s saying both sounds as he writes the phonograms.

a: (/ae/) Again, no new cards are needed. However, be sure to teach the word a as the second sound of the phonogram a. You can illustrate by using the word a with emphasis, saying something like «Give me A break!» as an example that we should associate the /ae/ sound with the word a. You can also explain that most of the time we say /u/, like «a car, a dog,» etc., but that he should always think of it as the /ae/ sound for spelling. Write a and don’t forget to put the number 2 above it, telling him it’s spelled with the phonogram /a/ae/o/.

it: (/i/t/) Get card number 12 (i) and teach your child that it’s /i/ie/ee/, and then repeat the process you’ve done above. No numbers are needed, since it uses the first sound of each phonogram.

is: (/i/z/) Get card number 7 (s) and teach your child that it’s /s/z/. You might want to illustrate a few cases where it sounds like /z/ in words, like at the end of has, his, and pens. When you spell is place a 2 above the s. Then have your child spell is and mark it with the 2 above the phonogram s.

she: (/sh/ee/) Get card number 27 (sh) and teach it as the /sh/ sound. Explain that sometimes we use two letters together to spell a sound and that we call that a digraph. Write she, underlining the phonogram sh and writing a 2 over the e. Explain that we underline any digraphs in a word with a single underline. Then have him write the word. Make sure your child is saying /sh/ just once as he writes the phonogram sh and that after writing she, he goes back and underlines the digraph sh and puts a 2 above the phonogram e.

Note: The reason to mark the word after writing it completely is so that your child doesn’t develop a habit of marking as he goes. After all, if all those markings show up on a spelling test, the words might be marked as incorrectly spelled. Explain that you are having him mark the words only once, at home, so that he can understand their spellings. He should not be marking words in a spelling test.

Summing Up So Far

What have you taught so far? If you add them up, you’ve taught the sounds for 11 phonograms. There are 84 in the complete set, many of them far simpler than the phonograms you’ve just taught, like a, o, i, and n, and you’re already over 10 percent of the way to teaching the complete set.

You’ve also taught a solid foundation for ten words. If you’d have taught them sight words to be simply memorized, you’d be just 4 percent of the way through a list of common sight words, and have established no foundation for learning any of them. Furthermore, there’s thousands more words that your child must learn to read on sight over the next few years.

As you go through the next 10 words on the Ayres List, you’ll need to teach fewer and fewer new phonograms. For example here are the next ten words and the new phonograms required to teach them: can (c), see (ee), run (r and u), the (th), in (none), so (none), no (none), now (ow), man (none), and ten (none). That’s six new phonograms for those ten words.

So, What’s a Sight Word, Really?

Notice that every single one of the first twenty words in the Ayres List is can be completely explained by referring to the common sounds associated with each of the phonograms. In other words, there isn’t a single sight word among them. Of course your child should learn to read them all by sight and he will. He will just find it far easier to do so when he knows the phonics information contained within the spelling of each word.

Furthermore, armed with that phonics knowledge, he’ll be able to extend it to read dozens, even hundreds, of new words almost immediately. When the next list comes home containing words like am, an, we, bed, us, and last, he’ll easily understand each of them, and will quickly learn to say them on sight, because he already knows the phonics code in all of them.

However, there are words, many of them quite common, that do contain some irregular, or unusual, spellings. The spellings in those words are so unusual that there is no value in teaching them as phonograms for the particular sound they represent, or even sometimes as phonograms at all.

The Double-Underline

The OnTrack Reading marking system treats unusual spellings by double-underlining them. If it’s an extraneous letter that appears randomly in the word, the double-underline just indicates that the letter represents no sound and can be ignored for pronunciation purposes, but must be remembered for spelling purposes.

On the other hand, if the spelling is an accepted phonogram, but represents an unusual sound in a particular word, then the phonogram is double-underlined and the sound it is representing is written under the word (using the notation described here.)

Rather than use random examples to illustrate the use of the double-underline convention, here are all of the words in the first 100 words of the Ayres List that require a double-underline:

of: Teach it as /o/v/, using the /o/ sound even though we tend to say «uv.» Double-underline the phonogram f and write «v» under the lines.

are: Underline the phonogram ar indicating a digraph. Double-underline the phonogram e to indicate that it’s an extraneous letter that must be remembered.

door: Double underline the phonogram oo indicating a digraph and write «oe» under it to denote the /oe/ sound.

floor: Same as door. If there were a lot more words like door and floor where the phonogram oo represents the /oe/ sound, it wold be taught as /oo/oul/oe/, but there aren’t so the /oe/ sound is treated as an unusual sound for that phonogram.

one: Teach it as /w/o/n/ with the ne phonogram underlined as a digraph for the /n/ sound. This is one of the weirdest English words (along with once) because it has a sound (/w/) without a phonogram to represent it. To mark it, double-underline the space in front of the word, and write «w» under the lines.

This takes us through about the first 120 words of the Ayres List and so far we have exactly five words that require double-underlining somewhere within the word. Even in those cases, there is obviously reliable phonics information contained within each of the five words.

We can now go through to about word 340 without requiring another case of double-underlining, at which point we hit the word eye. Now the word eye is probably one of the «sight words» most aggressively taught due to the apparent need to memorize every component of the word. (Most teachers probably draw a couple of e’s as eyes and then put the «y» between them as a nose, add a circle around the whole thing for a face, then add a mouth and ears. Trust me, this works. I worked with nearly 200 struggling readers, kids who were always misreading simple words, but nearly every one of them could read eye on sight.

But is there phonetic information in eye? If you compare it to words like bye, dye, lye, and rye, each of which contain a phonogram ye that represents the /ie/ sound, then you could, and should, mark the word eye as follows: Double-underline the e at the beginning to indicate an extraneous letter and single-underline the phonogram ye as a digraph that represents the /ie/ sound. As with other words containing double-underlines, this is a signal that the letter e must be remembered when spelling eye.

Note: The phonogram ye occurs infrequently enough that, while it is indeed a phonogram, it isn’t included in the 84-phonogram set that is formally taught. A number of phonograms are explained as they are encountered later, such as this one. Doubled consonants like bb and dd also aren’t included in the 84 phonograms formally taught; they are just explained as common spellings of the /b/ and /d/ sound when they are first encountered. Your child should already know the sound of the single phonograms b and d by that time that occurs.

Conclusion

You can let the public school system teach your child sight words if you wish, but your child will then be getting the very mixed, and misleading, message that some words are just not decodable and need to be memorized without regard to their phonetic content.

Or, if the above discussion has convinced you that all words have at least some phonetic structure to them, and that very few are actually irregular at all, provided the phonics code is properly taught, then you should consider teaching that structure to your child yourself, at home. Doing so will pay huge dividends if you can pull it off. And later, if you really want to create an advanced reader, consider teaching your child the OnTrack Reading Multisyllable Method for decoding longer words.

One last comment: As your child begins to learn short, simple words encourage him to write short sentences using the words learned so far. That’s one advantage of learning to read and spell the high-frequency words, and you might as well make the most use of it. These can be as simple as leaving each other notes around the house, with your child reading your notes while writing some of his own.

Sight words are an essential part of the reading process. They are hard words for students to «break down» or «sound out.» Sight words do not follow the standard English language spelling rules or the six types of syllables. Sight words usually have irregular spellings or complex spellings that are hard for children to sound out. Decoding sight words is hard or sometimes impossible, so teaching memorization is better.

Sight word recognition is an essential skill that students will learn while in elementary school. They are the building blocks to creating fluent readers and a strong foundation of reading skills.

Sight words are words found in a typical book at the elementary level. Fluent readers will be able to read a complete sight word list for their grade, and sight word fluency builds strong readers.

What are the differences between phonics and sight words?

The difference between sight words and phonics is simple. Phonics is the sound of each letter or syllable that can be broken down into a single sound, and sight words are words that are part of the building blocks of reading, but students will not always be able to sound out the words due to sight words not following standard spelling rules or the six types of syllables.

Phonics instruction gives students a basic understanding of how letter sounds are made and sound out a new word. The rules of phonics are clear when students are learning, but do not always apply to sight words, which is why students memorize them. Phonics comprehension is needed to have a solid foundation and progress students’ reading capabilities.

Knowing both phonics skills and sight words will help students’ reading progress and help them create a lifetime of reading.

Sight words are also different from high-frequency words. High-frequency words are the most common words used in texts or a typical book but mix decodable words (words that can be sounded out) and tricky words (words that don’t follow the standard English language rules).

Each grade level will have a standard list of sight words and phonics rules that students will learn during the school year.

What are the types of sight words?

There are many types of sight words. Sight words are the most common words found in an elementary level book that don’t follow the spelling rules or six types of syllables.

Two common sight words lists are Fry’s sight word lists, created by Edward Fry, and the Dolch sight word lists, created by Edward William Dolch.

There is a foundation of sight words for each grade level in elementary school, and most of them are built using either Fry’s or Dolch’s sight words lists. Each list holds a unique set of examples of sight words, and is created for every level of student.

Written below are lists of sight words common to teach in elementary school.

Edward Fry Sight Word List Level 1

| the | of | and | you | that |

| for | with | his | they | have |

| from | had | words | but | what |

| all | were | your | can | said |

| use | each | their | them | these |

Edward Dolch Sight Word List Kindergarten

| all | black | eat | into | our |

| am | brown | four | must | please |

| are | but | get | like | pretty |

| ate | came | good | new | saw |

| be | did | have | now | say |

How to teach sight words

Many teaching strategies can help students learn sight words quickly and easily. The goal to learn sight words is to help students memorize every word.

Here is an essential guide to sight words teaching techniques. Listed below are the easiest ways to introduce students to sight words and help them become efficient readers.

Teaching sight words is a large part of the method of teaching reading that helps students become efficient readers.

1. Sight words lists

Teachers can assign a sight word list to students as a tool to take home and study. It is easy to print out a leveled list to send home with students to practice at home.

Depending on the level of students (e.g. advanced students), you can assign students new lists and levels if they have already mastered the sight word list for their grade or level.

2. Sight words games

All students love to play games. That includes sight words games and sight word activities. Students can practice sight words in a fun, interactive way. There are so many games you can play with your students, pick a game that works well for your specific class.

Games are also perfect for non-readers or reluctant readers! They are an effective strategy to expose students to sight words while having fun.

Many sight word games can be interactive, such as sensory bags to spell words, find words in the morning message or announcement, and build words with bricks and legos. These are examples of hands-on interactive games that are fun for both the student and teacher.

3. Sight word games online

There are many educational online games that help students learn their sight word lists. The best online games are usually free to educators and students. Students love playing games online, they might even be encouraged to play them at home.

Roomrecess.com has a great game called «Sight Word Smash» where students ‘smash’ the word they are looking for by clicking it. They win the game by showing they know and can find all of their sight words.

It is easy to find other online games, such as sight word bingo, sight word memory, and many other fun games.

4. Sight words flashcards

Students can make flashcards or you can print them out for the whole class. It’s an easy way to practice memorization. Just flip through the cards to test students on their sight word skills.

Don’t forget to correct mistakes while students are playing games, doing activities, or reviewing flashcards. Giving students opportunities for repetition will allow them to memorize the sight words more easily.

Sight words takeaway

Memorization is the main key to increasing reading fluency and helping students remember sight word lists.

Helping students memorize their words will assist students in their long-term reading goals. You will see student fluency in reading increase if students can memorize their sight words.

‘Sight words’ is a term associated with reading. It normally refers to a set of words that appear repeatedly on a page in books while reading.

Sight words form the basics of reading lessons for children. The child is taught to recognize these words quickly and accurately. This will help the child to attain fluency in reading. Only when reading is fluent can the child understand and comprehend the written matter.

SIGHT WORD LISTS – AN OVERVIEW

The Dolch word list and the Fry word list are the most popular sight words list.

Dr. Edward Dolch has 200 sight words used in teaching students from Kindergarten to third grade.

He prepared this list by studying words that frequently occurred in children’s books during the 1930s and 1940s.

Dr. Edward Fry developed a word list based on words that frequently appeared in reading matter used from Grades 3 to 9 in the 1950s.

This list contains the most widely used 1000 words in English. The list includes words found in current books, textbooks, and newspapers.

Though there are almost 1000 sight words in the English language, the most commonly used is around 100 of them.

Words like I, we, on, all, who, the, he, was, does, me, be, there, am, then, at, an, so, are examples of sight words.

TEACHING OF SIGHT WORDS

Basic understanding of sight words:

It should be understood that the sight words cannot be taught through phonics. They cannot be sounded. In phonics, the child is taught to decode each word and read. Decoding of sight words will not make sense.

The sight words cannot be associated with illustrations and hence pictorial flashcards cannot be used.

Flashcards with the words written on them can be used. Readers are expected to recognize the words by looking at them.

Teaching sight words focus on the reading words that occur frequently without having to decode each and every word.

Hence it is critical that the instructors spend time to teach the children the right usage and pronunciation of these words.

When:

The language skills of children develop between the ages of three and five. This is not a written rule and hence these words can be taught as and when the child is found to be receptive.

Literacy experts suggest that a child in Kindergarten should be introduced to 20 sight words. The child should have mastered 100 sight words by the end of First Grade.

The sight words have to be stated several times to a child till he gets to read, say and use it right. The students are taught to memorize these words by sight as these words do not comply with any spelling or grammar rules.

They have to recognize these words instantly while reading. In short, the readers need to learn to by heart these words. This way reading becomes simpler and comprehension easier.

Methods:

Sight words can be taught in different ways.

-The most common method is to see and say. The child sees the word on a card and says the word while underlining the word with his finger.

-Spell reading is another technique used. The child says the word, spells the word and reads the word once again.

Also Read: Why is it important For Teachers to Study Philosophy Of Education?

– Air writing or skywriting is another method used where the child says the word and writes the letters in front of the word in the air.

-Table writing is a method where the child writes the letters on a table, first looking and then from memory.

-Arm tapping is yet another way where the child says the word and then spells out the letters tapping on his arm.

– Creating a song the lyrics of which resemble a familiar nursery rhyme or tune. The words are replaced with spellings of sight words.

– Creating a story on how the letters of these words look and how they are connected. Children build associations quicker by listening to stories.

The frequency of lessons and the child’s attention span determine whether all techniques are to be used. Ideally, the use of all these techniques, are recommended in the teaching of sight words.

The repetitive seeing, hearing, speaking, spelling, singing and writing of the words will ensure long term memorization.

How:

A child can be taught three to five new words in a day. These words can be reviewed before the start of the next day’s lessons.

If the child is able to recognize the words he can be taught another set of three to five words.

The pace can be slowed down if it is found that the child does not remember the first set of words.

It is said that the child has to recognize the word in about three seconds.

This is not a universal norm that needs to be followed. The pace of learning is dependent on factors like the age of the child, memory skills, and varies from child to child.

The words can be taught through simple games where they get a turn to read the words.

The teacher observes the child for correct reading. When they go wrong, the teacher takes the turn to read correctly without offending the children.

Word walls are found to be very effective in the teaching of sight words.

The teacher and children together prepare colorful charts with the words displayed on them. It acts as an interactive, ongoing platform for the different words taught and used frequently.

Books with repetitive matter and word search books help the child to identify the sight words being taught. Children get excited when they come across words they have learned.

Follow up of the techniques:

It is imperative that the teacher or instructor know to what extent the children have understood the lessons that have been taught.

Manipulative techniques like mixing up the letters and getting the children to rearrange them correctly help the teacher to understand their level of grasping. Magnetic alphabets or letter tiles can be used.

The children can be asked to identify sight words in print on the page of a book. They have to point out the specific word surrounded by other words, spaces, and punctuation marks. Kindergarten children may be rewarded each time they find the word.

Alternatively, the children could be asked to perform an activity each time the teacher came across the sight word in small group reading sessions.

Play-acting can be done with children forming the letters with their bodies.

These activities will reinforce the child’s knowledge too. Learning to read is not easy.

Identifying sight words increases the child’s confidence to read. Fluency in reading is the key to the understanding of the reading matter.

Each word matters in language and literature. Words help us to read, write, think and talk.

Words help to communicate. Hence it is essential to provide children with the right basic education. Sight words have to be memorized as there is no other way to master them.

The initiative and creativity of the teachers go a long way in the teaching of sight words. Their dedication and motivation are paramount to the success of the child’s learning.

What are sight words?

Sight words, or high frequency words as they’re often known, are vocabulary words that appear frequently in verbal and written communication – words such as the, come, to and where. Unfortunately for those learning to read, many of these words are irregularly spelt, making them difficult to sound out phonetically.

Why is it important to learn sight words?

As children read, if they stop to phonetically decode a word the flow of text is interrupted, and comprehension of what has been read can be lost as the reader’s focuses on the task of decoding. It is for this reason that most reading programs recommend that children develop the ability to recall high frequency words automatically or ‘on sight.’ Children with a good grasp of the most regularly used sight words are able to read more fluently which, in turn, supports good reading comprehension.

What is the Dolch Sight Word List?

There are many different sets of sight words commonly used in schools and reading programs – the Dolch Word List, Fry’s Instant Words and the Magic 100 words are all very popular. The Dolch Word List is a list of common vocabulary developed by Edward William Dolch in 1936. Dolch sourced these words by studying the vocabulary of popular children’s books. These words are believed to represent between 50% and 75% of all vocabulary used at a grade school level.

How many words are in the Dolch Sight Word List?

The Dolch word list contains 220 non-nouns divided into five groups, and an associated list of 95 high frequency nouns. The non-nouns are divided into five levels of difficulty;

Pre-Primer – 40 words

Primer – 52 words

First grade – 41 words

Second grade – 46 words

Third grade – 41 words

How to teach sight words?

Typically, when children begin to learn to read sight words they start with small subsets or lists of 5-10 new words at a time, moving on to a new set of words once each previous set is mastered. Mastery generally involves lots of repetition, but it definitely does not have to be dull or boring! An average reader needs around 30 exposures to a word for recall to become automatic. Even a good reader needs around 20 exposures to each word. Exposing children to sight words in a variety of different ways and formats, both in context and in isolation, is it important to sight word mastery. There are many fun and interesting ways to expose a child repeatedly to a word without relying on flashcard drills.

Game playing is one of our favourite ways to develop sight word recall. Games are fun and engaging, and children often do not realize how much they are learning when they are having fun playing a game with a friend or family member.

You will find a great selection of printable sight word games in our Sight Words Games pack.

The pack provides 16 different games for revising sight words. They are suitable for home and school, working well as homework revision tasks and for small group work. As with all early learning, adding a touch of fun or playfulness to practice time can help to engage a child’s interest in the learning experience.

Christie Burnett is a teacher, presenter, writer and the mother of two. She created Childhood 101 as a place for teachers and parents to access engaging, high quality learning ideas.