Productivity is

the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are

readily understood by the speakers of a language. The most important

and the most productive ways of word-formation are affixation,

conversion,

word-composition

and abbreviation

(contraction).

In the course of time the productivity of this or that way of

word-formation may change. Sound

interchange

or gradation

(blood −

to bleed, to abide − abode, to strike − stroke) was

a productive way of word building in old English and is important for

a diachronic study of the English language. It has lost its

productivity in Modern English and no new word can be coined by means

of sound gradation. Affixation on the contrary was productive in Old

English and is still one of the most productive ways of word building

in Modern English.

3. Affixation. General characteristics of suffixes and prefixes.

The process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some

root morpheme.

Suffixation

is more productive than prefixation.

In Modern English suffixation is characteristic of noun and adjective

formation, while prefixation is typical of verb formation (incoming,

trainee, principal, promotion).

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two large groups as words: native

and

borrowed (see

Lecture

1; Table 2).

It would be wrong, though, to suppose that affixes are borrowed in

the same way and for the same reasons as words. The

term borrowed

affixes

is not very exact as affixes are never

borrowed as such, but only as parts of loan words. To enter the

morphological system of the English language a borrowed affix has to

meet certain conditions. The borrowing of the affixes is possible

only if the number of words containing this affix is considerable, if

its meaning and function are definite and clear enough, and also if

its structural pattern corresponds to the structural patterns already

existing in the language.

If

these conditions are fulfilled, the foreign affix may even become

productive and combine with native stems or borrowed stems within the

system of English vocabulary like

-able <

Lat

-abilis

in

such words as laughable

or

unforgettable

and

unforgivable.

The

English words balustrade,

brigade, cascade are

borrowed from French. On the analogy with these in the English

language itself such words as blockade

are

coined.

Affixes are usually divided

into living

and dead

affixes.

Living affixes are easily separated from the stem (care-ful).

Dead affixes have become fully merged with the stem and can be

singled out by a diachronic analysis of the development of the word

(admit

− L.

ad+mittere).

Affixes can also be

classified into productive

and

non-productive

types. By productive

affixes

we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this

particular period of language development. The best way to identify

productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e. words

coined and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are

usually formed on the level of living speech and reflect the most

productive and progressive patterns in word-building:

unputdownable thrill;

“I

don’t

like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish”;

Professor Pringle was a

thinnish, baldish, dispeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock. (From Right-Ho,

Jeeves by

P.G. Wodehouse)

In many cases the choice of

the affixes is a means of differentiating meaning:

uninterested −

disinterested;

distrust − mistrust.

One should not confuse the

productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are

quite a number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no

longer used in word-derivation (e. g. the adjective-forming native

suffixes -ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant,

-ent, -al which

are quite frequent).

Unlike

roots, affixes are always bound forms. The difference between

suffixes and prefixes, it will be remembered, is not confined to

their respective position, suffixes being “fixed after” and

prefixes “fixed before” the stem. It also concerns their function

and meaning.

A

suffix

is

a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new

derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class,

сf.

-en,

-y, -less in

hearten,

hearty, heartless. When

both the underlying and the resultant forms belong to the same part

of speech, the suffix serves to differentiate between

lexico-grammatical classes by rendering some very general

lexico-grammatical meaning. For instance, both -ify

and

-er

are

verb suffixes, but the first characterises causative verbs, such as

horrify,

purify, rarefy, simplify, whereas

the second is mostly typical of frequentative verbs: flicker,

shimmer, twitter and

the like.

If we realise that suffixes

render the most general semantic component of the word’s lexical

meaning by marking the general class of phenomena to which the

referent of the word belongs, the reason why suffixes are as a rule

semantically fused with the stem stands explained.

A

prefix

is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying

meaning, cf. hearten

—

dishearten.

It

is only with verbs and statives that a prefix may serve to

distinguish one part of speech from another, like in earth

n

—

unearth

v,

sleep

n

—

asleep

(stative).

It

is interesting that as a prefix en-

may

carry the same meaning of being or bringing into a certain state as

the suffix -en,

сf.

enable,

encamp, endanger,

endear, enslave and

fasten,

darken, deepen, lengthen, strengthen.

Preceding

a verb stem, some prefixes express the difference between a

transitive and an intransitive verb: stay

v

and outstay

(sb)

vt. With a few exceptions prefixes modify the stem for time (pre-,

post-), place

(in-,

ad-) or

negation (un-,

dis-) and

remain semantically rather independent of the stem.

An

infix

is an affix placed within the word, like -n-

in

stand.

The

type is not productive. An affix should not be confused with a

combining form.

A

combining form is also a bound form but it can be distinguished from

an affix historically by the fact that it is always borrowed from

another language, namely, from Latin or Greek, in which it existed as

a free form, i.e. a separate word, or also as a combining form. They

differ from all other borrowings in that they occur in compounds and

derivatives that did not exist in their original language but were

formed only in modern times in English, Russian, French, etc., сf.

polyclinic,

polymer;

stereophonic, stereoscopic, telemechanics, television. Combining

forms

are mostly international. Descriptively a combining form differs from

an affix, because it can occur as one constituent of a form whose

only other constituent is an affix, as in graphic,

cyclic.

Also

affixes are characterised either by preposition with respect to the

root (prefixes) or by postposition (suffixes), whereas the same

combining

form may occur in both positions. Cf.

phonograph,

phonology and

telephone,

microphone, etc.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, productivity is the degree to which speakers of a language use a particular grammatical process, especially in word formation. It compares grammatical processes that are in frequent use to less frequently used ones that tend towards lexicalization. Generally the test of productivity concerns identifying which grammatical forms would be used in the coining of new words: these will tend to only be converted to other forms using productive processes.

Examples in English[edit]

In standard English, the formation of preterite and past participle forms of verbs by means of ablaut (as Germanic strong verbs, for example, sing–sang–sung) is no longer considered productive. Newly coined verbs in English overwhelmingly use the ‘weak’ (regular) ending -ed for the past tense and past participle (for example, spammed, e-mailed). Similarly, the only clearly productive plural ending is -(e)s; it is found on the vast majority of English count nouns and is used to form the plurals of neologisms, such as FAQs and Muggles. The ending -en, on the other hand, is no longer productive, being found only in oxen, children, and the now-rare brethren (as a plural of brother). Because these old forms can sound incorrect to modern ears, regularization can wear away at them until they are no longer used: brethren has now been replaced with the more regular-sounding brothers except when talking about religious orders. It appears that many strong verbs were completely lost during the transition from Old English to Middle English, possibly because they sounded archaic or were simply no longer truly understood.

In both cases, however, occasional exceptions have occurred. A false analogy with other verbs caused dug to become thought of as the ‘correct’ preterite and past participle form of dig (the King James Bible preferred digged in 1611) and more recent examples, like snuck from sneak and dove from dive, have similarly become popular. Some American English dialects also use the non-standard drug as the past tense of drag.

Significance[edit]

Since use to produce novel (new, non-established) structures is the clearest proof of usage of a grammatical process, the evidence most often appealed to as establishing productivity is the appearance of novel forms of the type the process leads one to expect, and many people would limit the definition offered above to exclude use of a grammatical process that does not result in a novel structure. Thus in practice, and, for many, in theory, productivity is the degree to which speakers use a particular grammatical process for the formation of novel structures. A productive grammatical process defines an open class, one which admits new words or forms. Non-productive grammatical processes may be seen as operative within closed classes: they remain within the language and may include very common words, but are not added to and may be lost in time or through regularization converting them into what now seems to be a correct form.

Productivity is, as stated above and implied in the examples already discussed, a matter of degree, and there are a number of areas in which that may be shown to be true. As the example of -en becoming productive shows, what has apparently been non-productive for many decades or even centuries may suddenly come to some degree of productive life, and it may do so in certain dialects or sociolects while not in others, or in certain parts of the vocabulary but not others. Some patterns are only very rarely productive, others may be used by a typical speaker several times a year or month, whereas others (especially syntactic processes) may be used productively dozens or hundreds of times in a typical day. It is not atypical for more than one pattern with similar functions to be comparably productive, to the point that a speaker can be in a quandary as to which form to use —e.g., would it be better to say that a taste or color like that of raisins is raisinish, raisiny, raisinlike, or even raisinly?

It can also be very difficult to assess when a given usage is productive or when a person is using a form that has already been learned as a whole. Suppose a reader comes across an unknown word such as despisement meaning «an attitude of despising». The reader may apply the verb+ment noun-formational process to understand the word perfectly well, and this would be a kind of productive use. This would be essentially independent of whether or not the writer had also used the same process productively in coining the term, or whether he or she had learned the form from previous usage (as most English speakers have learned government, for instance), and no longer needed to apply the process productively in order to use the word. Similarly a speaker or writer’s use of words like raisinish or raisiny may or may not involve productive application of the noun+ish and noun+y rules, and the same is true of a hearer or reader’s understanding of them. But it will not necessarily be at all clear to an outside observer, or even to the speaker and hearer themselves, whether the form was already learnt and whether the rules were applied or not.

English and productive forms[edit]

Developments over the last five hundred years or more have meant English has developed in ways very different from the evolution of most world languages across history.[citation needed] English is a language with a long written past that has preserved many words that might otherwise have been lost or changed, often in fixed texts such as the King James Version of the Bible which are not updated regularly to modernise their language. English also has many conventions for writing polite and formal prose, which are often very different from how people normally speak.

As literacy among English-speakers has become almost universal, it has become increasingly easy for people to bring back into life archaic words and grammar forms, often to create a comic or humorously old-fashioned effect, with the expectation that the new coinings will be understandable. Those processes would be much rarer for languages without a culture of literacy.

English has also borrowed extensively from other languages because of technology and trade and often borrows both plural and singular forms into standard English. For example, the plural of radius (from Latin) has not decisively settled between radiuses and the original Latin radii, but educated opinion prefers the latter. In some cases, new words have been coined from these bases (often Latin) on the same rules.

Examples in other languages[edit]

One study, which focuses on the usage of the Dutch suffix -heid (comparable to -ness in English) hypothesizes that -heid gives rise to two kinds of abstract nouns: those referring to concepts and those referring to states of affairs. It shows that the referential function of -heid is typical for the lowest-frequency words, while its conceptual function is typical for the highest-frequency words. It claims that high-frequency formations with the suffix -heid are available in the mental lexicon, whereas low-frequency words and neologisms are produced and understood by rule.[1]

See also[edit]

- Word formation

- Inflection

References[edit]

- Baayen, Harald. (1992). Quantitative aspects of morphological productivity. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology, 1991. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 109–149. ISBN 0-7923-1416-6.

- Baayen, Harald & Rochelle Lieber. (1991). Productivity and English derivation: A corpus-based study. Linguistics 29, 801-844.

- Bauer, Laurie. (2001). Morphological productivity. Cambridge studies in linguistics (No. 95). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79238-X.

- Bolozky, Shmuel. (1999). Measuring productivity in word formation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11252-9.

- Hay, Jennifer & Harald Baayen. (2002). Parsing and productivity. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology, 2002, 203–35. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Palmer, Chris C. (2015). Measuring productivity diachronically: nominal suffixes in English letters, 1400–1600. English Language and Linguistics, 19, 107-129. doi:10.1017/S1360674314000264.

- Plag, Ingo. (1999). Morphological productivity: Structural constraints in English derivation. Topics in English linguistics (No. 28). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015833-7.

- Säily, Tanja. (2014). Sociolinguistic variation in English derivational productivity: Studies and methods in diachronic corpus linguistics. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique.

- Schröder, Anne. (2011). On the productivity of verbal prefixation in English: Synchronic and diachronic perspectives. Tübingen: Narr.

- Trips, Carola. (2009). Lexical semantics and diachronic morphology: The development of -hood, -dom and -ship in the history of English. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Notes[edit]

- ^ BAAYEN, R. & NEIJT, A. (2009). Productivity in context: a case study of a Dutch suffix. Linguistics, 35(3), pp. 565-588. Retrieved 24 Oct. 2017, from doi:10.1515/ling.1997.35.3.565

Lecture №3. Productive and Non-productive Ways of Word-formation in Modern English

Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by the speakers of language. The most important and the most productive ways of word-formation are affixation, conversion, word-composition and abbreviation (contraction). In the course of time the productivity of this or that way of word-formation may change. Sound interchange or gradation (blood-to bleed, to abide-abode, to strike-stroke) was a productive way of word building in old English and is important for a diachronic study of the English language. It has lost its productivity in Modern English and no new word can be coined by means of sound gradation. Affixation on the contrary was productive in Old English and is still one of the most productive ways of word building in Modern English.

WORDBUILDING

Word-building is one of the main ways of enriching vocabulary. There are four main ways of word-building in modern English: affixation, composition, conversion, abbreviation. There are also secondary ways of word-building: sound interchange, stress interchange, sound imitation, blends, back formation.

AFFIXATION

Affixation is one of the most productive ways of word-building throughout the history of English. It consists in adding an affix to the stem of a definite part of speech. Affixation is divided into suffixation and prefixation.

Suffixation

The main function of suffixes in Modern English is to form one part of speech from another, the secondary function is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. (e.g. «educate» is a verb, «educator» is a noun, and music» is a noun, «musical» is also a noun or an adjective). There are different classifications of suffixes :

1. Part-of-speech classification. Suffixes which can form different parts of speech are given here :

a) noun-forming suffixes, such as: —er (criticizer), —dom (officialdom), —ism (ageism),

b) adjective-forming suffixes, such as: —able (breathable), less (symptomless), —ous (prestigious),

c) verb-forming suffixes, such as —ize (computerize) , —ify (minify),

d) adverb-forming suffixes , such as : —ly (singly), —ward (tableward),

e) numeral-forming suffixes, such as —teen (sixteen), —ty (seventy).

2. Semantic classification. Suffixes changing the lexical meaning of the stem can be subdivided into groups, e.g. noun-forming suffixes can denote:

a) the agent of the action, e.g. —er (experimenter), —ist (taxist), -ent (student),

b) nationality, e.g. —ian (Russian), —ese (Japanese), —ish (English),

c) collectivity, e.g. —dom (moviedom), —ry (peasantry, —ship (readership), —ati (literati),

d) diminutiveness, e.g. —ie (horsie), —let (booklet), —ling (gooseling), —ette (kitchenette),

e) quality, e.g. —ness (copelessness), —ity (answerability).

3. Lexico—grammatical character of the stem. Suffixes which can be added to certain groups of stems are subdivided into:

a) suffixes added to verbal stems, such as: —er (commuter), —ing (suffering), — able (flyable), —ment (involvement), —ation (computerization),

b) suffixes added to noun stems, such as: —less (smogless), —ful (roomful), —ism (adventurism), —ster (pollster), —nik (filmnik), —ish (childish),

c) suffixes added to adjective stems, such as: —en (weaken), —ly (pinkly), —ish (longish), —ness (clannishness).

4. Origin of suffixes. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) native (Germanic), such as —er,-ful, —less, —ly.

b) Romanic, such as : —tion, —ment, —able, —eer.

c) Greek, such as : —ist, —ism, -ize.

d) Russian, such as —nik.

5. Productivity. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) productive, such as: —er, —ize, —ly, —ness.

b) semi-productive, such as: —eer, —ette, —ward.

c) non-productive , such as: —ard (drunkard), —th (length).

Suffixes can be polysemantic, such as: —er can form nouns with the following meanings: agent, doer of the action expressed by the stem (speaker), profession, occupation (teacher), a device, a tool (transmitter). While speaking about suffixes we should also mention compound suffixes which are added to the stem at the same time, such as —ably, —ibly, (terribly, reasonably), —ation (adaptation from adapt). There are also disputable cases whether we have a suffix or a root morpheme in the structure of a word, in such cases we call such morphemes semi-suffixes, and words with such suffixes can be classified either as derived words or as compound words, e.g. —gate (Irangate), —burger (cheeseburger), —aholic (workaholic) etc.

Prefixation

Prefixation is the formation of words by means of adding a prefix to the stem. In English it is characteristic for forming verbs. Prefixes are more independent than suffixes. Prefixes can be classified according to the nature of words in which they are used: prefixes used in notional words and prefixes used in functional words. Prefixes used in notional words are proper prefixes which are bound morphemes, e.g. un— (unhappy). Prefixes used in functional words are semi-bound morphemes because they are met in the language as words, e.g. over— (overhead) (cf. over the table). The main function of prefixes in English is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. But the recent research showed that about twenty-five prefixes in Modern English form one part of speech from another (bebutton, interfamily, postcollege etc).

Prefixes can be classified according to different principles:

1. Semantic classification:

a) prefixes of negative meaning, such as: in— (invaluable), non— (nonformals), un— (unfree) etc,

b) prefixes denoting repetition or reversal actions, such as: de— (decolonize), re— (revegetation), dis— (disconnect),

c) prefixes denoting time, space, degree relations, such as: inter— (interplanetary) , hyper— (hypertension), ex— (ex-student), pre— (pre-election), over— (overdrugging) etc.

2. Origin of prefixes:

a) native (Germanic), such as: un-, over-, under— etc.

b) Romanic, such as: in-, de-, ex-, re— etc.

c) Greek, such as: sym-, hyper— etc.

When we analyze such words as adverb, accompany where we can find the root of the word (verb, company) we may treat ad-, ac— as prefixes though they were never used as prefixes to form new words in English and were borrowed from Romanic languages together with words. In such cases we can treat them as derived words. But some scientists treat them as simple words. Another group of words with a disputable structure are such as: contain, retain, detain and conceive, receive, deceive where we can see that re-, de-, con— act as prefixes and —tain, —ceive can be understood as roots. But in English these combinations of sounds have no lexical meaning and are called pseudo-morphemes. Some scientists treat such words as simple words, others as derived ones. There are some prefixes which can be treated as root morphemes by some scientists, e.g. after— in the word afternoon. American lexicographers working on Webster dictionaries treat such words as compound words. British lexicographers treat such words as derived ones.

COMPOSITION

Composition is the way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more stems to form one word. The structural unity of a compound word depends upon: a) the unity of stress, b) solid or hyphеnated spelling, c) semantic unity, d) unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. These are characteristic features of compound words in all languages. For English compounds some of these factors are not very reliable. As a rule English compounds have one uniting stress (usually on the first component), e.g. hard-cover, best—seller. We can also have a double stress in an English compound, with the main stress on the first component and with a secondary stress on the second component, e.g. blood—vessel. The third pattern of stresses is two level stresses, e.g. snow—white, sky—blue. The third pattern is easily mixed up with word-groups unless they have solid or hyphеnated spelling.

Spelling in English compounds is not very reliable as well because they can have different spelling even in the same text, e.g. war—ship, blood—vessel can be spelt through a hyphen and also with a break, insofar, underfoot can be spelt solidly and with a break. All the more so that there has appeared in Modern English a special type of compound words which are called block compounds, they have one uniting stress but are spelt with a break, e.g. air piracy, cargo module, coin change, penguin suit etc. The semantic unity of a compound word is often very strong. In such cases we have idiomatic compounds where the meaning of the whole is not a sum of meanings of its components, e.g. to ghostwrite, skinhead, brain—drain etc. In nonidiomatic compounds semantic unity is not strong, e. g., airbus, to bloodtransfuse, astrodynamics etc.

English compounds have the unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. They are used in a sentence as one part of it and only one component changes grammatically, e.g. These girls are chatter-boxes. «Chatter-boxes» is a predicative in the sentence and only the second component changes grammatically. There are two characteristic features of English compounds:

a) Both components in an English compound are free stems, that is they can be used as words with a distinctive meaning of their own. The sound pattern will be the same except for the stresses, e.g. «a green-house» and «a green house». Whereas for example in Russian compounds the stems are bound morphemes, as a rule.

b) English compounds have a two-stem pattern, with the exception of compound words which have form-word stems in their structure, e.g. middle-of-the-road, off—the—record, up—and—doing etc. The two-stem pattern distinguishes English compounds from German ones.

WAYS OF FORMING COMPOUND WORDS

Compound words in English can be formed not only by means of composition but also by means of:

a) reduplication, e.g. too—too, and also by means of reduplication combined with sound interchange , e.g. rope-ripe,

b) conversion from word-groups, e.g. to micky—mouse, can—do, makeup etc,

c) back formation from compound nouns or word-groups, e.g. to bloodtransfuse, to fingerprint etc ,

d) analogy, e.g. lie—in (on the analogy with sit-in) and also phone—in, brawn—drain (on the analogy with brain—drain) etc.

CLASSIFICATIONS OF ENGLISH COMPOUNDS

1. According to the parts of speech compounds are subdivided into:

a) nouns, such as: baby-moon, globe-trotter,

b) adjectives, such as : free-for-all, power-happy,

c) verbs, such as : to honey-moon, to baby-sit, to henpeck,

d) adverbs, such as: downdeep, headfirst,

e) prepositions, such as: into, within,

f) numerals, such as : fifty—five.

2. According to the way components are joined together compounds are divided into: a) neutral, which are formed by joining together two stems without any joining morpheme, e.g. ball—point, to windowshop,

b) morphological where components are joined by a linking element: vowels «o» or «i» or the consonant «s», e.g. («astrospace», «handicraft», «sportsman»),

c) syntactical where the components are joined by means of form-word stems, e.g. here-and-now, free-for-all, do-or-die.

3. According to their structure compounds are subdivided into:

a) compound words proper which consist of two stems, e.g. to job-hunt, train-sick, go-go, tip-top,

b) derivational compounds, where besides the stems we have affixes, e.g. ear—minded, hydro-skimmer,

c) compound words consisting of three or more stems, e.g. cornflower—blue, eggshell—thin, singer—songwriter,

d) compound-shortened words, e.g. boatel, VJ—day, motocross, intervision, Eurodollar, Camford.

4. According to the relations between the components compound words are subdivided into:

a) subordinative compounds where one of the components is the semantic and the structural centre and the second component is subordinate; these subordinative relations can be different: with comparative relations, e.g. honey—sweet, eggshell—thin, with limiting relations, e.g. breast—high, knee—deep, with emphatic relations, e.g. dog—cheap, with objective relations, e.g. gold—rich, with cause relations, e.g. love—sick, with space relations, e.g. top—heavy, with time relations, e.g. spring—fresh, with subjective relations, e.g. foot—sore etc

b) coordinative compounds where both components are semantically independent. Here belong such compounds when one person (object) has two functions, e.g. secretary-stenographer, woman-doctor, Oxbridge etc. Such compounds are called additive. This group includes also compounds formed by means of reduplication, e.g. fifty-fifty, no-no, and also compounds formed with the help of rhythmic stems (reduplication combined with sound interchange) e.g. criss-cross, walkie-talkie.

5. According to the order of the components compounds are divided into compounds with direct order, e.g. kill—joy, and compounds with indirect order, e.g. nuclear—free, rope—ripe.

CONVERSION

Conversion is a characteristic feature of the English word-building system. It is also called affixless derivation or zero-suffixation. The term «conversion» first appeared in the book by Henry Sweet «New English Grammar» in 1891. Conversion is treated differently by different scientists, e.g. prof. A.I. Smirntitsky treats conversion as a morphological way of forming words when one part of speech is formed from another part of speech by changing its paradigm, e.g. to form the verb «to dial» from the noun «dial» we change the paradigm of the noun (a dial, dials) for the paradigm of a regular verb (I dial, he dials, dialed, dialing). A. Marchand in his book «The Categories and Types of Present-day English» treats conversion as a morphological-syntactical word-building because we have not only the change of the paradigm, but also the change of the syntactic function, e.g. I need some good paper for my room. (The noun «paper» is an object in the sentence). I paper my room every year. (The verb «paper» is the predicate in the sentence). Conversion is the main way of forming verbs in Modern English. Verbs can be formed from nouns of different semantic groups and have different meanings because of that, e.g.:

a) verbs have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting parts of a human body e.g. to eye, to finger, to elbow, to shoulder etc. They have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting tools, machines, instruments, weapons, e.g. to hammer, to machine-gun, to rifle, to nail,

b) verbs can denote an action characteristic of the living being denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to crowd, to wolf, to ape,

c) verbs can denote acquisition, addition or deprivation if they are formed from nouns denoting an object, e.g. to fish, to dust, to peel, to paper,

d) verbs can denote an action performed at the place denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to park, to garage, to bottle, to corner, to pocket,

e) verbs can denote an action performed at the time denoted by the noun from which they have been converted e.g. to winter, to week-end.

Verbs can be also converted from adjectives, in such cases they denote the change of the state, e.g. to tame (to become or make tame), to clean, to slim etc.

Nouns can also be formed by means of conversion from verbs. Converted nouns can denote: a) instant of an action e.g. a jump, a move,

b) process or state e.g. sleep, walk,

c) agent of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a help, a flirt, a scold,

d) object or result of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a burn, a find, a purchase,

e) place of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a drive, a stop, a walk.

Many nouns converted from verbs can be used only in the Singular form and denote momentaneous actions. In such cases we have partial conversion. Such deverbal nouns are often used with such verbs as: to have, to get, to take etc., e.g. to have a try, to give a push, to take a swim.

CRITERIA OF SEMANTIC DERIVATION

In cases of conversion the problem of criteria of semantic derivation arises: which of the converted pair is primary and which is converted from it. The problem was first analized by prof. A.I. Smirnitsky. Later on P.A. Soboleva developed his idea and worked out the following criteria:

1. If the lexical meaning of the root morpheme and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide the word is primary, e.g. in cases pen — to pen, father — to father the nouns are names of an object and a living being. Therefore in the nouns «pen» and «father» the lexical meaning of the root and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide. The verbs «to pen» and «to father» denote an action, a process therefore the lexico-grammatical meanings of the stems do not coincide with the lexical meanings of the roots. The verbs have a complex semantic structure and they were converted from nouns.

2. If we compare a converted pair with a synonymic word pair which was formed by means of suffixation we can find out which of the pair is primary. This criterion can be applied only to nouns converted from verbs, e.g. «chat» n. and «chat» v. can be compared with «conversation» – «converse».

3. The criterion based on derivational relations is of more universal character. In this case we must take a word-cluster of relative words to which the converted pair belongs. If the root stem of the word-cluster has suffixes added to a noun stem the noun is primary in the converted pair and vica versa, e.g. in the word-cluster: hand n., hand v., handy, handful the derived words have suffixes added to a noun stem, that is why the noun is primary and the verb is converted from it. In the word-cluster: dance n., dance v., dancer, dancing we see that the primary word is a verb and the noun is converted from it.

SUBSTANTIVIZATION OF ADJECTIVES

Some scientists (Yespersen, Kruisinga) refer substantivization of adjectives to conversion. But most scientists disagree with them because in cases of substantivization of adjectives we have quite different changes in the language. Substantivization is the result of ellipsis (syntactical shortening) when a word combination with a semantically strong attribute loses its semantically weak noun (man, person etc), e.g. «a grown-up person» is shortened to «a grown-up». In cases of perfect substantivization the attribute takes the paradigm of a countable noun, e.g. a criminal, criminals, a criminal’s (mistake), criminals’ (mistakes). Such words are used in a sentence in the same function as nouns, e.g. I am fond of musicals. (musical comedies). There are also two types of partly substantivized adjectives: 1) those which have only the plural form and have the meaning of collective nouns, such as: sweets, news, finals, greens; 2) those which have only the singular form and are used with the definite article. They also have the meaning of collective nouns and denote a class, a nationality, a group of people, e.g. the rich, the English, the dead.

«STONE WALL» COMBINATIONS

The problem whether adjectives can be formed by means of conversion from nouns is the subject of many discussions. In Modern English there are a lot of word combinations of the type, e.g. price rise, wage freeze, steel helmet, sand castle etc. If the first component of such units is an adjective converted from a noun, combinations of this type are free word-groups typical of English (adjective + noun). This point of view is proved by O. Yespersen by the following facts:

1. «Stone» denotes some quality of the noun «wall».

2. «Stone» stands before the word it modifies, as adjectives in the function of an attribute do in English.

3. «Stone» is used in the Singular though its meaning in most cases is plural, and adjectives in English have no plural form.

4. There are some cases when the first component is used in the Comparative or the Superlative degree, e.g. the bottomest end of the scale.

5. The first component can have an adverb which characterizes it, and adjectives are characterized by adverbs, e.g. a purely family gathering.

6. The first component can be used in the same syntactical function with a proper adjective to characterize the same noun, e.g. lonely bare stone houses.

7. After the first component the pronoun «one» can be used instead of a noun, e.g. I shall not put on a silk dress, I shall put on a cotton one.

However Henry Sweet and some other scientists say that these criteria are not characteristic of the majority of such units. They consider the first component of such units to be a noun in the function of an attribute because in Modern English almost all parts of speech and even word-groups and sentences can be used in the function of an attribute, e.g. the then president (an adverb), out-of-the-way villages (a word-group), a devil-may-care speed (a sentence). There are different semantic relations between the components of «stone wall» combinations. E.I. Chapnik classified them into the following groups:

1. time relations, e.g. evening paper,

2. space relations, e.g. top floor,

3. relations between the object and the material of which it is made, e.g. steel helmet,

4. cause relations, e.g. war orphan,

5. relations between a part and the whole, e.g. a crew member,

6. relations between the object and an action, e.g. arms production,

7. relations between the agent and an action e.g. government threat, price rise,

8. relations between the object and its designation, e.g. reception hall,

9. the first component denotes the head, organizer of the characterized object, e.g. Clinton government, Forsyte family,

10. the first component denotes the field of activity of the second component, e.g. language teacher, psychiatry doctor,

11. comparative relations, e.g. moon face,

12. qualitative relations, e.g. winter apples.

ABBREVIATION

In the process of communication words and word-groups can be shortened. The causes of shortening can be linguistic and extra-linguistic. By extra-linguistic causes changes in the life of people are meant. In Modern English many new abbreviations, acronyms, initials, blends are formed because the tempo of life is increasing and it becomes necessary to give more and more information in the shortest possible time. There are also linguistic causes of abbreviating words and word-groups, such as the demand of rhythm, which is satisfied in English by monosyllabic words. When borrowings from other languages are assimilated in English they are shortened. Here we have modification of form on the basis of analogy, e.g. the Latin borrowing «fanaticus» is shortened to «fan» on the analogy with native words: man, pan, tan etc. There are two main types of shortenings: graphical and lexical.

Graphical abbreviations

Graphical abbreviations are the result of shortening of words and word-groups only in written speech while orally the corresponding full forms are used. They are used for the economy of space and effort in writing. The oldest group of graphical abbreviations in English is of Latin origin. In Russian this type of abbreviation is not typical. In these abbreviations in the spelling Latin words are shortened, while orally the corresponding English equivalents are pronounced in the full form, e.g. for example (Latin exampli gratia), a.m. – in the morning (ante meridiem), No – number (numero), p.a. – a year (per annum), d – penny (dinarius), lb – pound (libra), i. e. – that is (id est) etc.

Some graphical abbreviations of Latin origin have different English equivalents in different contexts, e.g. p.m. can be pronounced «in the afternoon» (post meridiem) and «after death» (post mortem). There are also graphical abbreviations of native origin, where in the spelling we have abbreviations of words and word-groups of the corresponding English equivalents in the full form. We have several semantic groups of them: a) days of the week, e.g. Mon – Monday, Tue – Tuesday etc

b) names of months, e.g. Apr – April, Aug – August etc.

c) names of counties in UK, e.g. Yorks – Yorkshire, Berks – Berkshire etc

d) names of states in USA, e.g. Ala – Alabama, Alas – Alaska etc.

e) names of address, e.g. Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr. etc.

f) military ranks, e.g. capt. – captain, col. – colonel, sgt – sergeant etc.

g) scientific degrees, e.g. B.A. – Bachelor of Arts, D.M. – Doctor of Medicine. (Sometimes in scientific degrees we have abbreviations of Latin origin, e.g., M.B. – Medicinae Baccalaurus).

h) units of time, length, weight, e.g. f./ft – foot/feet, sec. – second, in. – inch, mg. – milligram etc.

The reading of some graphical abbreviations depends on the context, e.g. «m» can be read as: male, married, masculine, metre, mile, million, minute, «l.p.» can be read as long-playing, low pressure.

Initial abbreviations

Initialisms are the bordering case between graphical and lexical abbreviations. When they appear in the language, as a rule, to denote some new offices they are closer to graphical abbreviations because orally full forms are used, e.g. J.V. – joint venture. When they are used for some duration of time they acquire the shortened form of pronouncing and become closer to lexical abbreviations, e.g. BBC is as a rule pronounced in the shortened form. In some cases the translation of initialisms is next to impossible without using special dictionaries. Initialisms are denoted in different ways. Very often they are expressed in the way they are pronounced in the language of their origin, e.g. ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States) is given in Russian as АНЗУС, SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) was for a long time used in Russian as СОЛТ, now a translation variant is used (ОСВ – Договор об ограничении стратегических вооружений). This type of initialisms borrowed into other languages is preferable, e.g. UFO – НЛО, CП – JV etc. There are three types of initialisms in English:

a) initialisms with alphabetical reading, such as UK, BUP, CND etc

b) initialisms which are read as if they are words, e.g. UNESCO, UNO, NATO etc.

c) initialisms which coincide with English words in their sound form, such initialisms are called acronyms, e.g. CLASS (Computor-based Laboratory for Automated School System). Some scientists unite groups b) and c) into one group which they call acronyms. Some initialisms can form new words in which they act as root morphemes by different ways of wordbuilding:

a) affixation, e.g. AVALism, ex- POW, AIDSophobia etc.

b) conversion, e.g. to raff, to fly IFR (Instrument Flight Rules),

c) composition, e.g. STOLport, USAFman etc.

d) there are also compound-shortened words where the first component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical reading and the second one is a complete word, e.g. A-bomb, U-pronunciation, V -day etc. In some cases the first component is a complete word and the second component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical pronunciation, e.g. Three -Ds (Three dimensions) – стереофильм.

Abbreviations of words

Abbreviation of words consists in clipping a part of a word. As a result we get a new lexical unit where either the lexical meaning or the style is different form the full form of the word. In such cases as «fantasy» and «fancy», «fence» and «defence» we have different lexical meanings. In such cases as «laboratory» and «lab», we have different styles. Abbreviation does not change the part-of-speech meaning, as we have it in the case of conversion or affixation, it produces words belonging to the same part of speech as the primary word, e.g. prof. is a noun and professor is also a noun. Mostly nouns undergo abbreviation, but we can also meet abbreviation of verbs, such as to rev. from to revolve, to tab from to tabulate etc. But mostly abbreviated forms of verbs are formed by means of conversion from abbreviated nouns, e.g. to taxi, to vac etc. Adjectives can be abbreviated but they are mostly used in school slang and are combined with suffixation, e.g. comfy, dilly etc. As a rule pronouns, numerals, interjections. conjunctions are not abbreviated. The exceptions are: fif (fifteen), teen-ager, in one’s teens (apheresis from numerals from 13 to 19). Lexical abbreviations are classified according to the part of the word which is clipped. Mostly the end of the word is clipped, because the beginning of the word in most cases is the root and expresses the lexical meaning of the word. This type of abbreviation is called apocope. Here we can mention a group of words ending in «o», such as disco (dicotheque), expo (exposition), intro (introduction) and many others. On the analogy with these words there developed in Modern English a number of words where «o» is added as a kind of a suffix to the shortened form of the word, e.g. combo (combination) – небольшой эстрадный ансамбль, Afro (African) – прическа под африканца etc. In other cases the beginning of the word is clipped. In such cases we have apheresis, e.g. chute (parachute), varsity (university), copter (helicopter), thuse (enthuse) etc. Sometimes the middle of the word is clipped, e.g. mart (market), fanzine (fan magazine) maths (mathematics). Such abbreviations are called syncope. Sometimes we have a combination of apocope with apheresis, when the beginning and the end of the word are clipped, e.g. tec (detective), van (vanguard) etc. Sometimes shortening influences the spelling of the word, e.g. «c» can be substituted by «k» before «e» to preserve pronunciation, e.g. mike (microphone), Coke (coca-cola) etc. The same rule is observed in the following cases: fax (facsimile), teck (technical college), trank (tranquilizer) etc. The final consonants in the shortened forms are substituded by letters characteristic of native English words.

NON-PRODUCTIVE WAYS OF WORDBUILDING

SOUND INTERCHANGE

Sound interchange is the way of word-building when some sounds are changed to form a new word. It is non-productive in Modern English, it was productive in Old English and can be met in other Indo-European languages. The causes of sound interchange can be different. It can be the result of Ancient Ablaut which cannot be explained by the phonetic laws during the period of the language development known to scientists, e.g. to strike – stroke, to sing – song etc. It can be also the result of Ancient Umlaut or vowel mutation which is the result of palatalizing the root vowel because of the front vowel in the syllable coming after the root (regressive assimilation), e.g. hot — to heat (hotian), blood — to bleed (blodian) etc. In many cases we have vowel and consonant interchange. In nouns we have voiceless consonants and in verbs we have corresponding voiced consonants because in Old English these consonants in nouns were at the end of the word and in verbs in the intervocalic position, e.g. bath – to bathe, life – to live, breath – to breathe etc.

STRESS INTERCHANGE

Stress interchange can be mostly met in verbs and nouns of Romanic origin: nouns have the stress on the first syllable and verbs on the last syllable, e.g. `accent — to ac`cent. This phenomenon is explained in the following way: French verbs and nouns had different structure when they were borrowed into English, verbs had one syllable more than the corresponding nouns. When these borrowings were assimilated in English the stress in them was shifted to the previous syllable (the second from the end). Later on the last unstressed syllable in verbs borrowed from French was dropped (the same as in native verbs) and after that the stress in verbs was on the last syllable while in nouns it was on the first syllable. As a result of it we have such pairs in English as: to af«fix -`affix, to con`flict- `conflict, to ex`port -`export, to ex`tract — `extract etc. As a result of stress interchange we have also vowel interchange in such words because vowels are pronounced differently in stressed and unstressed positions.

SOUND IMITATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by imitating different sounds. There are some semantic groups of words formed by means of sound imitation:

a) sounds produced by human beings, such as : to whisper, to giggle, to mumble, to sneeze, to whistle etc.

b) sounds produced by animals, birds, insects, such as: to hiss, to buzz, to bark, to moo, to twitter etc.

c) sounds produced by nature and objects, such as: to splash, to rustle, to clatter, to bubble, to ding-dong, to tinkle etc.

The corresponding nouns are formed by means of conversion, e.g. clang (of a bell), chatter (of children) etc.

BLENDS

Blends are words formed from a word-group or two synonyms. In blends two ways of word-building are combined: abbreviation and composition. To form a blend we clip the end of the first component (apocope) and the beginning of the second component (apheresis) . As a result we have a compound- shortened word. One of the first blends in English was the word «smog» from two synonyms: smoke and fog which means smoke mixed with fog. From the first component the beginning is taken, from the second one the end, «o» is common for both of them. Blends formed from two synonyms are: slanguage, to hustle, gasohol etc. Mostly blends are formed from a word-group, such as: acromania (acronym mania), cinemaddict (cinema adict), chunnel (channel, canal), dramedy (drama comedy), detectifiction (detective fiction), faction (fact fiction) (fiction based on real facts), informecial (information commercial), Medicare (medical care), magalog (magazine catalogue) slimnastics (slimming gymnastics), sociolite (social elite), slanguist (slang linguist) etc.

BACK FORMATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by dropping the final morpheme to form a new word. It is opposite to suffixation, that is why it is called back formation. At first it appeared in the language as a result of misunderstanding the structure of a borrowed word. Prof. Yartseva explains this mistake by the influence of the whole system of the language on separate words. E.g. it is typical of English to form nouns denoting the agent of the action by adding the suffix -er to a verb stem (speak- speaker). So when the French word «beggar» was borrowed into English the final syllable «ar» was pronounced in the same way as the English —er and Englishmen formed the verb «to beg» by dropping the end of the noun. Other examples of back formation are: to accreditate (from accreditation), to bach (from bachelor), to collocate (from collocation), to enthuse (from enthusiasm), to compute (from computer), to emote (from emotion), to televise (from television) etc.

As we can notice in cases of back formation the part-of-speech meaning of the primary word is changed, verbs are formed from nouns.

23

Lecture 3 Word-formation in Modern English 1. Productivity. Productive and non-productive ways of word-formation. 2. Derivation. 2.1. Semantics of Affixes. 2.2. Boundary cases between derivation, inflection and composition 2.2.1 Semi-Affixes. 2.2.2. Combining forms. 2.3. Reduplication. 3. Compounds. 3.1. Neutral Compounds 3.3. Morphological compounds 3.4 Syntactic compounds 3.5. Specific features of English Compounding 3.6. The criteria of compounds. 3.7. Pseudo-compounds. 11 December 2017 1

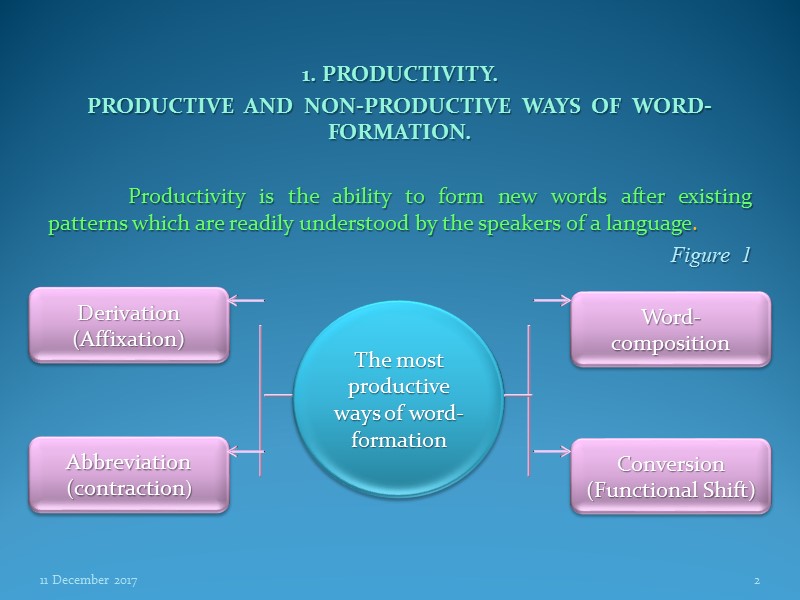

1. PRODUCTIVITY. PRODUCTIVE AND NON-PRODUCTIVE WAYS OF WORD-FORMATION. Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by the speakers of a language. Figure 1 , 11 December 2017 2 The most productive ways of word-formation Abbreviation (contraction) Conversion (Functional Shift) Derivation (Affixation) Word-composition

In the course of time the productivity of this or that way of word-formation may change. Sound interchange or gradation (blood − to bleed, to abide − abode, to strike − stroke) was a productive way of word building in old English and is important for a diachronic study of the English language. It has lost its productivity in Modern English and no new word can be coined by means of sound gradation. Affixation on the contrary was productive in Old English and is still one of the most productive ways of word building in Modern English. 11 December 2017 3

2. DERIVATION The addition of a word-forming affix is called derivation. The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme. Suffixation is more productive than prefixation. Suffixation is characteristic of noun and adjective formation, while prefixation is typical of verb formation (incoming, trainee, principal, promotion). Figure 2 11 December 2017 4

a phonological change: reduce > reduction, clear > clarity, fuse > fusion, include > inclusive, drama > dramatize, relate > relation, permit > permissive, impress > impression, electric > electricity, photograph > photography; an orthographic change to the root: pity > pitiful, deny > denial, happy > happiness; a semantic change: husband > husbandry, event > eventual, post > postage, recite > recital, emerge >emergency; a change in word class: eat (V) > eatable (A), impress (V) > impression (N). 11 December 2017 5

In English, derivational affixes are either prefixes or suffixes. They may be native (deriving from Old English) or foreign (borrowed along with a word from a foreign language, especially French). Their productivity may range from very limited to quite extensive, depending upon whether they are preserved in just a few words and no longer used to create new words or whether they are found in many words and still used to create new words. An example of an unproductive suffix is the -th in warmth, width, depth, or wealth, whereas an example of a productive suffix is the -able in available, unthinkable, admirable, or honorable. Which affix attaches to which root is always quite arbitrary and unpredictable; it is not a matter of rule but must be stated separately for each root . 11 December 2017 6

Derivation is part of the lexicon, not part of the grammar of a language. Only three prefixes, which are no longer productive in English, systematically change the part of speech of the root: а- N/V > A ablaze, asleep, astir, astride, abed, abroad be- N > V betoken, befriend, bedeck, becalm, besmirch en- A/N > V enlarge, ensure, encircle, encase, entrap Other prefixes change only the meaning of the root, not its class. 11 December 2017 7

11 December 2017 8 Table 1. Semantic Classes of Prefixes in English

Many suffixes attached to nouns change their meaning but not their class: The diminutive suffixes -ling, -let, -y, -ie (as in princeling, piglet, daddy, hoodie), Diminution (e.g. doggy) is not the only use for the diminutive suffix; it may also express degradation (e.g. dummy), amelioration (e.g. hubby), and intimacy (e.g. Jenny < Jennifer). 11 December 2017 9 Functions of Suffixes to change the meaning of the root and to change the part of speech of the root Figure 3

the feminine suffixes -ess, -ette, -rix, -ine (as in actress, usherette, aviatrix, heroine) − which, for social and cultural reasons, are now falling out of use, the abstract suffixes -ship, -hood, -ism, making abstract nouns out of concrete nouns (as in friendship, neighborhood, hoodlumism), or suffixes denoting people such as -(i)an, -ist, -er (in librarian, Texan, Canadian, Marxist, Londoner). Some suffixes attached to adjectives likewise change only their meaning: -ish means ‘nearly, not exactly’ in greenish, fortyish, coldish -ly express ‘resemblance’ in goodly, sickly, lonely More often, however, suffixes change the word class of the root as shown in Table 2 11 December 2017 10

11 December 2017 11 Table 2. Derivational Suffixes in English

11 December 2017 12 Table 2. Derivational Suffixes in English (Continued)

The false morphological division of words may result in more or less productive suffixes, which one scholar calls “splinters”, as in the following: ham/burger > cheeseburger; fishburger; mushroomburger; vegieburger alc/oholic > workaholic; chocaholic; rageaholic mar/athon > workathon; telethon; swimathon; walkathon pano/rama > autorama ; motorama caval/cade > aquacade; motorcade heli/copter > heliport; helidrome; helistop 11 December 2017 13

Derivation can be stated in terms of lexical rules: mis- + align (V) + -ment > misalignment (N) image (N) + -ine + -ary > imaginary (A) false (A) + -ify> falsify (V) 11 December 2017 14

11 December 2017 15 the number of words containing this affix is considerable its meaning and function are definite and clear enough its structural pattern corresponds to the structural patterns already existing in the language Conditions for borrowing an affix Figure 4 From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

If these conditions are fulfilled, the foreign affix may even become productive and combine with native stems or borrowed stems within the system of English vocabulary like -able < Lat -abilis in such words as laughable or unforgettable and unforgivable. The English words balustrade, brigade, cascade are borrowed from French. On the analogy with these in the English language itself such words as blockade are coined. Affixes are usually divided into living and dead affixes. Living affixes are easily separated from the stem: care-ful) Dead affixes have become fully merged with the stem and can be singled out by a diachronic analysis of the development of the word: admit < Lat. ad+mittere. 11 December 2017 16

Affixes can also be classified into productive and non-productive types. By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words (words coined and used only for this particular occasion). The latter are usually formed on the level of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive patterns in word-building: unputdownable thrill; “I don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish”; Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish, dispeptic-lookingish cove with an eye like a haddock. 11 December 2017 17

In many cases the choice of the affixes is a means of differentiating meaning: uninterested − disinterested; distrust − mistrust. One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in word-derivation, cf.: the adjective-forming native suffixes -ful, -ly; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al Affixes are always bound forms. 11 December 2017 18

The difference between suffixes and prefixes is not confined to their respective position, suffixes being “fixed after” and prefixes “fixed before” the stem. It also concerns their function and meaning. A suffix is a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class, сf. : -en, -y, -less in hearten, hearty, heartless. When both the underlying and the resultant forms belong to the same part of speech, the suffix serves to differentiate between lexico-grammatical classes by rendering some very general lexico-grammatical meaning, cf.: -ify (characterises causative verbs) horrify, purify, rarefy, simplify; -er (is mostly typical of frequentative verbs) flicker, shimmer, twitter. 11 December 2017 19

A prefix is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying meaning, cf.: hearten — dishearten. It is only with verbs and statives that a prefix may serve to distinguish one part of speech from another, cf.: earth n — unearth v, sleep n — asleep (stative). Preceding a verb stem, some prefixes express the difference between a transitive and an intransitive verb: stay v — outstay (sb) vt. With a few exceptions prefixes modify the stem for time (pre-, post-), place (in-, ad-) or negation (un-, dis-) and remain semantically rather independent of the stem. 11 December 2017 20

2.1. SEMANTICS OF AFFIXES Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalised meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is vast and all-embracing. Figure 5 11 December 2017 21 the noun-forming suffix -er the object of their occupation / labour: painter — the one who paints their place of origin / abode: southerner — the one living in the South

Some words with this suffix have no equivalents in Ukrainian and may be rendered in descriptive way: The sheriff might have been a slow talker, but he was a fast mover (Irish). − Можливо, шериф і говорив повільно, та рухався він швидко. I’m not a talker, boys, talking’s not what I do, but I want you to know that this is not…. (King). − Я не дуже балакучий… Other noun-forming suffixes designating the same semantic field both in English and Ukrainian are given in table 3: 11 December 2017 22

11 December 2017 23 Table 3

11 December 2017 24 Table 3 (Continued)

11 December 2017 25 Table 4

2.2. BOUNDARY CASES BETWEEN DERIVATION, INFLECTION AND COMPOSITION 2.2.1 SEMI-AFFIXES There are a few roots in English which have developed great combining ability in the position of the second element of a word and a very general meaning similar to that of an affix. These are semi-affixes − semantically, functionally, structurally and statistically they behave more like affixes than like roots. Their meaning is as general. They determine the lexical and grammatical class the word belongs to, cf.: sailor ↔ seaman, -or is a suffix, -man is a semi-affix: sportsman, gentleman, nobleman, salesman, seaman, fisherman, countryman, statesman, policeman. 11 December 2017 26

Semantically, the constituent -man in these words approaches the generalised meaning of such noun-forming suffixes as -er, -or, -ist ( artist), -ite (hypocrite). Other examples of semi-affixes are: -land Ireland, Scotland, fatherland, wonderland -like ladylike, unladylike, businesslike, starlike, flowerlike, -worthy seaworthy, trustworthy, praiseworthy . The component -proof, standing between a stem and an affix, is regarded by some scholars as a semi-affix: “… The Great Glass Elevator is shockproof, waterproof, bombproof and bulletproof…” Lady Malvern tried to freeze him with a look, but you can’t do that sort of thing to Jeeves. He is look-proof. Better sorts of lip-stick are frequently described in advertisements as kissproof. Some building materials may be advertised as fireproof. Certain technical devices are foolproof meaning that they are safe even in a fool’s hands. 11 December 2017 27

All these words, with -proof for the second component, stand between compounds and derived words in their characteristics. On the one hand, the second component seems to bear all the features of a stem and preserves certain semantic associations with the free form proof. On the other hand, the meaning of -proof in all the numerous words built on this pattern has become so generalised that it is certainly approaching that of a suffix. The high productivity of the pattern is proved, once more, by the possibility of coining nonce-words after this pattern: look-proof. Semi-affixes may be also used in preposition like prefixes. Thus, anything that is smaller or shorter than others of its kind may be preceded by mini-: mini-budget, mini-bus, mini-car, mini-crisis, mini-planet, mini-skirt, etc. Other productive semi-affixes used in pre-position are midi-, maxi-, self- and others: midi-coat, maxi-coat, self-starter, self-help. 11 December 2017 28

In Ukrainian the following semi-affixes are used: повно- ново- само- авто- повноправний, новостворений, самохідний, автобіографія -вод, -воз діловод, тепловоз. Figure 6 . 11 December 2017 29 The factors conducing to transition of free forms into semi-affixes High semantic productivity Adaptability Combinatorial capacity (high valency), Brevity

2.2.2. COMBINING FORMS An affix should not be confused with a combining form. Combining forms are linguistic forms which in modern languages are used as bound forms although in Greek and Latin from which they are borrowed they functioned as independent words. They constitute a specific type of linguistic units . Combining forms are mostly international. Descriptively a combining form differs from an affix, because it can occur as one constituent of a form whose only other constituent is an affix, cf.: graphic, cyclic. Affixes are characterised either by preposition with respect to the root (prefixes) or by postposition (suffixes), whereas the same combining form may occur in both positions, cf.: phonograph, phonology and telephone, microphone, etc 11 December 2017 30

Combining forms differ from all other borrowings in that they occur in compounds and derivatives that did not exist in their original language but were formed only in modern times in English, Russian, French, etc., сf.: polyclinic, polymer; stereophonic, stereoscopic, telemechanics, television. Combining forms are particularly frequent in the specialised vocabularies of arts and sciences. They have long become familiar in the international scientific terminology. Many of them attain widespread currency in everyday language: astron − star → astronomy; autos − self → automatic; bios − life → biology; electron − amber → electronics; ge − earth → geology; graph − to write → typography; hydor − water →hydroelectric; logos − speech → physiology; philein − love → philology phone − sound, voice → telephone; 11 December 2017 31

Combining forms mostly occur together with other combining forms and not with native roots. Almost all of the above examples are international words, each entering a considerable word-family: autobiography, autodiagnosis, automobile, autonomy, autogenic, autopilot, autoloader; bio-astronautics, biochemistry, bio-ecology, bionics, biophysics; economics, economist, economise, eco-climate, eco-activist, eco-type, eco-catastrophe; geodesy, geometry, geography; hydrodynamic, hydromechanic, hydroponic, hydrotherapeutic. hydrography, phonograph, photograph, telegraph. lexicology, philology, phonology. 11 December 2017 32

2.3 Reduplication Reduplication is a process similar to derivation, in which the initial syllable or the entire word is doubled, exactly or with a slight phonological change. Reduplication is not a common or regular process of word formation in English, though it may be in other languages. In English reduplication is often used in children’s language (e.g. boo-boo, putt-putt, choo-choo) or for humorous or ironic effect (e.g. goody-goody, rah-rah, pooh-pooh). 11 December 2017 33

11 December 2017 34 Exact reduplication papa, mama, goody-goody, so-so, hush-hush, never-never, tutu, fifty-fifty, hush-hush Ablaut reduplication criss-cross, zig-zag,flip-flop, mish-mash, wishy-washy, clip-clop, riff-raff, achy-breaky Rhyme reduplication hodge-podge, fuddy-duddy, razzle-dazzle, boogie-woogie, nitty-gritty, roly-poly, hob-nob, hocus-pocus Figure 7 Reduplication

Reduplications can be formed with two meaningful parts: flower-power, brain drain, culture vulture, boy toy, heart smart. Reduplication has many different functions. it can express: 1) disparagement (namby- pamby), 2) intensification (super-duper), diminution (teeny-weeny), 3) onomatopoeia (tick- tock), or alternation (ping-pong), among other uses. Reduplication is greatly facilitated in Modern English by the vast number of monosyllables. 11 December 2017 35

Stylistically speaking, most words made by reduplication represent informal groups: colloquialisms and slang: walkie-talkie − a portable radio; riff-raff − the worthless or disreputable element of society; chi-chi − sl. for chic as in a chi-chi girl. In a modern novel an angry father accuses his teenager son of doing nothing but dilly-dallying all over the town. (dilly-dallying — wasting time, doing nothing, loitering) Another example of a word made by reduplication may be found in the following quotation from The Importance of Being Earnest by O. Wilde: I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. (shilly-shallying — irresolution, indecision) 11 December 2017 36

3. COMPOUNDS A compound is the combination of two or more free roots (plus associated affixes). The bulk of compound words is motivated and the semantic relations between the two components are transparent. The great variety of compound types brings about a great variety of classifications (see Figure 7). 11 December 2017 37

11 December 2017 38 Compound words may be classified The type of composition and the linking element The part of speech to which the compound belongs The type of composition and the linking element Within each part of speech according to the structural pattern Semantically Motivated Idiomatic compounds Structurally Endocentric Exocentric Bahuvrihi Syntactic Asyntactic Figure 8 Phrase compounds Reduplicative compounds Pseudo-compounds Quotation compounds

Eendocentric: Eng. beetroot, ice-cold, knee-deep, babysit, whitewash; UA. землеустрій, сівозміна, літакобудування; Exocentric: Eng. scarecrow — something that scares crows; UA гуртожиток, склоріз, самопал; Bahuvrihi: Eng. lazy-bones, fathead, bonehead, readcoat ; UA. шибайголова, одчайдух, жовтобрюх; Syntactic and asyntactic combinations: Which of those fellows do you like to command a search-and-destroy mission?; “Now come along, Bridget. I don’t want any silliness”, she said in her Genghis-Khan-at-height-of-evil voice; Kurtz caught sight of Permutter’s sunken, I-fooled-you grin in the wide rearview mirror. 11 December 2017 39

The classification according to the type of composition establishes the following groups: 1) The predominant type is a mere juxtaposition without connecting elements: heartache n, heart-beat n, heart-break n, heart-breaking adj, heart-broken adj, heart-felt adj. 2) Composition with a vowel or a consonant as a linking element. The examples are very few: electromotive adj, speedometer n, Afro-Asian adj, handicraft n, statesman n. 3) Compounds with linking elements represented by preposition or conjunction stems: down-and-out n, matter-of-fact adj, son-in-law n, pepper-and-salt adj, wall-to-wall adj, up-to-date adj, on the up-and-up adv, up-and-coming. 11 December 2017 40

The classification of compounds according to the structure of immediate constituents distinguishes: 1) compounds consisting of simple stems: film-star. Compounds formed by joining together stems of words already available in the language and the two ICs of which are stems of notional words are also called compounds proper: Eng. ice-cold (N+A), ill-luck (A+N); UA диван-ліжко, матч-реванш, лікар-терапевт. 2) compounds where at least one of the constituents is a derived stem: chain-smoker; 3) compounds where at least one of the constituents is a clipped stem: maths-mistress (in British English) math-mistress (in American English). The subgroup will contain abbreviations like H-bag (handbag) or Xmas (Christmas), whodunit n (for mystery novels); 11 December 2017 41

4) compounds where at least one of the constituents is a compound stem: wastepaper-basket. In coordinative compounds neither of the components dominates the other, both are structurally and semantically independent and constitute two structural and semantic centres, cf.: breath-taking, self-discipline, word-formaiton. Compounds are not homogeneous in structure. Traditionally three types are distinguished: neutral, morphological and syntactic. In neutral compounds the process of compounding is realised without any linking elements, by a mere juxtaposition of two stems: blackbird, shop-window, sunflower, bedroom, tallboy, etc. There are three subtypes of neutral compounds depending on the structure of the constituent stems. The examples above represent the subtype which may be described as simple neutral compounds: they consist of simple affixless stems. 11 December 2017 42

The productivity of derived or derivational compounds (compound-derivatives) is confirmed by a considerable number of comparatively recent formations, cf.: teenager, babysitter, strap-hanger, fourseater (car or boat with four seats), doubledecker (a ship or bus with two decks). Numerous nonce-words are coined on this pattern which is another proof of its high productivity: luncher-out (a person who habitually takes his lunch in restaurants and not at home), goose-flesher (murder story). In the coining of the derivational compounds two types of word-formation are at work. The essence of the derivational compounds will be clear if we compare them with derivatives and compounds proper that possess a similar structure. 11 December 2017 43

brainstraster, honeymooner UC’s = noun stem + noun stem+-er. mill-owner mill-owner IC’s = two noun stems mill+owner (Composition) honeymooner IC’s = mooner does not exist as a free stem IC’s = honeymoon + er (honey+moon)+-er (Derivation: honeymoon a compound honeymooner a derivative) brains trust (a phrase) brainstruster = composition +derivation = a derivational compound IC’s = (brains+ trust)+-еr. 11 December 2017 44

Another frequent type of derivational compounds are the possessive compounds of the type kind-hearted: adjective stem+noun stem+ -ed. kind-hearted IC’s = a noun phrase kind heart + -ed The first element may also be a noun stem or a numeral: bow-legged, heart-shaped, three-coloured. The derivational compounds often become the basis of further derivation, cf. : war-minded → war-mindedness; whole-hearted → whole-heartedness → whole-heartedly, schoolboyish → schoolboyishness; do-it-yourselfer → do-it-yourselfism. The process is also called phrasal derivation: mini-skirt → mini-skirted, nothing but → nothingbutism, or quotation derivation as when an unwillingness to do anything is characterised as let-George-do-it-ity. All these are nonce-words, with some ironic or jocular connotation. 11 December 2017 45

` Morphological compounds, words in which two compounding stems are combined by a linking vowel or consonant are few in number. This type is non-productive: Anglo-Saxon, Franko-Prussian, handiwork, handicraft, craftsmanship, spokesman, statesman. Syntactic compounds (the term is arbitrary) are formed from segments of speech, preserving in their structure numerous traces of syntagmatic relations typical of speech: articles, prepositions, adverbs, cf.: lily-of-the-valley, Jack-of-all-trades, good-for-nothing, mother-in-law, sit-at-home. 11 December 2017 46

Both the semantics and the syntax of compound are complex. Often the semantics of compounds are not simply a sum of the meaning of the parts, that is, if we know the meaning of the two roots, we cannot necessarily predict the meaning of the compound, as in firearm, highball, makeup, or handout. Note the various ways in which the meanings of the roots of these compounds interact with home: homeland ‘land which is one’s home’ homemade ‘something which is made at home’ homebody ‘someone who stays at home’ homestead ‘a place which is a home’ homework ‘work which is done at home’ homerun ‘a run to home’ homemaker ‘a person who makes (cares for) the home’ 11 December 2017 47

The syntax of compounds is even more complex. Any combination of parts of speech seems possible, with almost any part of speech resulting. One principle which holds is that the word class of the compound is determined by the head of the compound, or its rightmost member, whereas the leftmost member carries the primary stress. The only exception to this rule is a converted compound or one containing a class changing suffix. Look at the syntactic patterns of compounding shown in Table 5. 11 December 2017 48

11 December 2017 49 Table 5. Syntactic Patterns in English Compounds

11 December 2017 50 Table 5. Syntactic Patterns in English Compounds. (Continued)

11 December 2017 51 Table 5. Syntactic Patterns in English Compounds. (Continued)

A problem for the differentiation of compounds and phrases is the phrasal verb. Older English preferred prefixed verbs, such as forget, understand, withdraw, befriend, overrun, outdo, offset, and uproot, but prefixing of verbs is not productive in Modern English, except for those with out- and over-. Modern English favors verbs followed by postverbal particles, such as run over, lead on, use up, stretch out, and put down. Like compounds, phrasal verbs have semantic coherence, evidenced by the fact that they are sometimes replaceable by single Latinate verbs, as in the following: break out → erupt, escape think up → imagine count out → exclude put off → delay take off → depart, remove egg on → incite work out → solve put out → extinguish bring up → raise put away → store go on — continue take up → adopt 11 December 2017 52