Want to join the conversation?

-

What if I don’t know what is the right word to put in? I can’t tell the difference between two choices.

Button navigates to signup pageComment on tom.chen’s post “What if I don’t know what…”

-

If you dont know which word to put in , then simply see which one you would use while forming a sentence so that it would feel accurate.

Button navigates to signup page

-

-

what should I do if I do not know the meaning of the words given in the option

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Well, then you have a problem. Take a look at any of the word roots you can identify and try and guess at the meaning. Let’s say I didn’t know what «promote» meant. I know «pro» means good or forwards, and I might have heard a word that uses «mot» like «motion». I could make the guess then that «promote» means «to move forward» or something. Based on the context, I can deduce that the passage isn’t talking about literally pushing something forwards, and I might stumble upon the thought that it means to push an idea forwards, if I’m lucky enough. If not, it might be best to just guess quickly on the problem. If you’ve eliminated every other answer, choose the word you don’t know. If another answer looks promising, choose it over the word you don’t know. Hope this helps.

Comment on Hecretary Bird’s post “Well, then you have a pro…”

-

-

What is the best way to study for this section? I find myself struggling on this part of the test. I have done many practice problems but can’t seem to tell which is the right answer.

Button navigates to signup pageComment on Yulia Ivanova’s post “What is the best way to s…”

-

How can I help my choosing between two words when both I know are very similar?

Button navigates to signup pageComment on delanie.loya6y’s post “How can I help my choosin…”

-

I am following short of time in solving English section, can u give me any tips for that

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Most English questions are relatively simple, and can be solved in under half a minute by really good test takers. If you see a question and there looks to be two answer choices that could both work, you have to be missing something. The Writing test, more than the other parts of the SAT, is about searching for details. If you scan answer choices more efficiently, you can pick up on those details faster. One technique you can use is to look at the differences between answer choices instead of the answer choices themselves. Most answer choices will use relatively similar wording and everything, but switch out a comma for a semicolon or something like that. Instead of going through the answers one by one and seeing which is right, go through each part of the 4 answers and see which attributes they have, and then decide which attributes are wrong, and eliminate the answers that have those attributes.

For example, let’s say you had:

a) Jenny had a big truck

b) Jenny, had a big truck

c) Jenny, has a big truck

d) Jenny have big truck

Then, you would look for the parts of the answer choices that vary among them, which will be the parts that let u answer the question. You’d make the following observations:

b) and c) have a comma after Jenny.

c) uses «has»

d) uses «have»

d) does not have «a» before «big truck»

Look at the comma first. If its wrong, then b) and c) are wrong, and if not, a) and d) are wrong. From there, just find another detail that doesn’t fit on one of the remaining answers and the question’s done.Comment on Hecretary Bird’s post “Most English questions ar…”

-

-

As a non-native English speaker I am having a fairly hard time managing time on reading and writing questions but I am having no problems with maths exam. I was wondering if I could use the extra time I save with maths in reading and writing or do they take place in different time periods?

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Unfortunately, you can’t do this. Everybody does one section, and then only after the time runs out do you continue with the next section, and you can never turn back to work on a past section, or anything that isn’t being tested at the time. No flipping between sections is allowed on the SAT, sadly.

Button navigates to signup page

-

-

what do i do if two answers sound correct?

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Can we choose (the shorter is better) in the word choice lesson?

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Probably not, in my opinion. Shorter words have an equal chance of being wrong with these question as more complex words. It’s important to actually know the meanings of the words so that you can find which one works best.

Comment on Hecretary Bird’s post “Probably not, in my opini…”

-

-

how many questions on the test

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

52 reading questions, 44 writing questions, 20 math (no calculator) questions, and 38 math (with calculator) questions.

That makes a total of 154 questions.

Comment on Evan’s post “52 reading questions, 44 …”

-

-

I saw that in this part of the test (writing and language test), there were passages for me to read. So, do you suggest reading the whole passage or should I just read the sentence that has the underlined word?

Button navigates to signup pageButton navigates to signup page

-

Up to personal preference. Reading the passage and answering as you reach the question might seem more natural to you; if it does, do it. It could save time when you have questions that ask about the passage as a whole, but these occur infrequently on the writing test, so it might not save time in the long run. If you think you’ll get hung up on the intricacies of the passage that aren’t tested, don’t read the passage. I’ve heard people recommend both.

Button navigates to signup page

-

Table of Contents

- Why should Speakers pay close attention to word choice?

- Why is word choice so important in communication?

- What is strong word choice?

- What is word choice in a poem?

- What do you call the three dots in a sentence?

- What is a proposition as it is used in the Gettysburg Address?

- Does score mean 20?

- What is a score in money?

- What is slang for a fiver?

Answer: It is important because it does not confuse the reader; a strong, precise word choice makes things clear and vivid. A strong word choice can also invoke feelings you want readers to feel. For example, a specific word choice can make your readers feel angry, sad, or inspired.

Why should Speakers pay close attention to word choice?

To better understand the speaker’s intentions. Explanation: When an author writes any text, he puts particular attention to his choice of words. If the reader pays close attention to the word choice of the author, he will better understand the speaker’s intentions.

Why is word choice so important in communication?

Word choice is an important part of any type of writing-especially content writing. Selecting precise words will help you increase the impact you create on your audience. The best writing creates a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. By appealing to one or more of your reader’s senses, you create a compelling message.

Strong word choice is characterized not so much by an exceptional vocabulary chosen to impress the reader, but more by the skill to use everyday words well.

What is word choice in a poem?

“Word choice” refers to the words a poet chooses to use. Word choice is extremely important in poetry, since the poem is such a compact form. Sometimes poets choose words for the way they sound; sometimes for their connotations.

What do you call the three dots in a sentence?

ellipsis

What is a proposition as it is used in the Gettysburg Address?

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

Does score mean 20?

A ‘score’ is a group of 20 (often used in combination with a cardinal number, i.e. fourscore to mean 80), but also often used as an indefinite number (e.g. the newspaper headline “Scores of Typhoon Survivors Flown to Manila”).

What is a score in money?

A score is an old term for 20, usually not used with money. Cockney Rhyming Slang with money includes: A ‘pony’ which is £25, a ‘ton’ is £100 and a ‘monkey’, which equals £500. Also used regularly is a ‘score’ which is £20, a ‘bullseye’ is £50, a ‘grand’ is £1,000 and a ‘deep sea diver’ which is £5 (a fiver).

What is slang for a fiver?

A five-dollar note is known colloquially as a fin, a fiver, or half a sawbuck. A ten-dollar note is known colloquially as a ten-spot, a dixie, or a sawbuck.

Answer: To better understand the speaker’s intentions. Explanation: If the reader pays close attention to the word choice of the author, he will better understand the speaker’s intentions.

Precision

A very important part of word choice is precision.

Through precise word selection, you can increase the clarity of your argument by enabling your readers to grasp your intended meaning quickly and accurately. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that your word choices affect a reader’s attitudes toward your presentation and your subject matter. Therefore, you also need to choose words that will convey your ideas clearly to your readers. This kind of precise writing will help your audience understand your argument.

Regardless of the words you use, you must use them accurately. Usage errors can distract readers from your argument.

How can you ensure that words are used accurately?

Unfortunately, there is no easy way, but there are some solutions. You can revisit a text that uses the word and observe how the word is used in that instance. Additionally, you can consult a dictionary whenever you are uncertain. Be especially careful when using words that are not yet part of your usual vocabulary.

General vs. Specific Words

You can increase the clarity of your writing by using concrete, specific words rather than abstract, general ones.

Almost anything can be described either in general words or in specific ones.

General words and specific words are not opposites. General words cover a broader spectrum with a single word than specific words. Specific words narrow the scope of your writing by providing more details. For example, “car” is a general term that could be made more specific by writing “Honda Accord.”

Specific words are a subset of general words. You can increase the clarity of your writing by choosing specific words over general words. Specific words help your readers understand precisely what you mean in your writing. Here’s an example of general and specific words in a sentence:

- General: She said, “I don’t want you to go.”

- Specific: She murmured, “I don’t want you to go.”

The words “said” and “murmured” are similar. They both are a form of verbal communication. However, “murmured” gives the sentence a different feeling from “said.” Thus, as a writer, choosing specific words over general words can add description to and change the mood of your writing.

(Caveat: When writing fiction, avoid the temptation to frequently alter the dialogue tag «said.» Doing so can be distracting for readers. The tag, «said,» is so common it almost becomes invisible, letting readers keep their focus where it should be—on the actual dialogue.)

Using the Dictionary and Thesaurus Effectively

Always use a dictionary to confirm the meaning of any word about which you are unsure. Although the built-in dictionary that comes with your word processor is a great time-saver, it falls far short of college-edition dictionaries, or the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). If the spell-check tool suggests bizarre corrections for one of your words, it could be that you know a word it does not. When in doubt, always check a dictionary to be sure.

Vocabulary Choice and Style

It’s important to vary word choice. If it feels like you keep repeating a word throughout your writing, pull out a thesaurus for ideas on different, more creative choices. A thesaurus can add some color and depth to a piece that may otherwise seem repetitive and mundane. However, make sure that the word you substitute has the meaning you intend to convey.

Thesauruses provide words with similar meanings, not identical meanings. If you are unsure about the precise meaning of a replacement word, look up the new word in a dictionary.

Connotation

Connotation is the extended or suggested meaning of a word beyond its literal meaning. For example, “flatfoot” and “police detective” are often thought to be synonyms, but they connote very different things: “flatfoot” suggests a plodding, perhaps not very bright cop, while “police detective” suggests an intelligent professional.

Verbs, too, have connotations. For instance, to “suggest” that someone has overlooked a key fact is not the same as to “insinuate” it. To “devote” your time to working on a client’s project is not the same as to “spend” your time on it. The connotations of your words can shape your audience ‘s perception of your argument.

Register

“Register” refers to a word’s association with certain situations or contexts. In a restaurant ad, for example, we might expect to see the claim that it offers “amazingly delicious food.” However, we would not expect to see a research company boast in a proposal for a government contract that it is capable of conducting “amazingly good studies.” Here, the word “amazingly” is in the register of consumer advertising, but not in the register of research proposals.

Being aware of the connotation and register of your word choice will help increase your writing’s clarity.

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

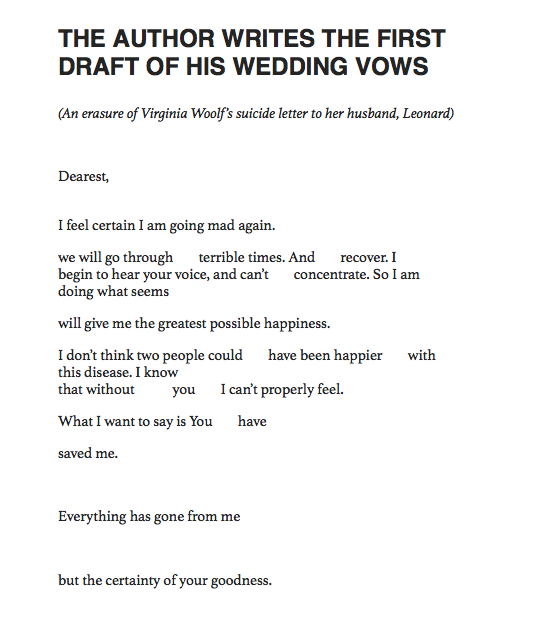

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Asked by: Prof. Bennett Sipes

Score: 4.4/5

(5 votes)

Precisest meaning

Superlative form of precise: most precise.

How do you use the word precise?

English Sentences Focusing on Words and Their Word Families The Word «Precise» in Example Sentences Page 1

- [S] [T] Tom is precise. ( …

- [S] [T] You’re precise. ( …

- [S] [T] Be more precise. ( …

- [S] [T] I should’ve been more precise. ( …

- [S] [T] My watch is very precise. ( …

- [S] [T] Precise measurements are needed. (

What does it mean when someone is precise?

Precise means strictly correct or very exact. If you need something to be precise, like the positioning of a safety net for a stunt jump over a canyon, there’s no room for error.

What are the precise words?

Frequently Asked Questions About precise

Some common synonyms of precise are accurate, correct, exact, nice, and right. While all these words mean «conforming to fact, standard, or truth,» precise adds to exact an emphasis on sharpness of definition or delimitation.

How do you describe a precise person?

someone who is precise is always careful to be accurate and to behave correctly. Synonyms and related words. Careful and cautious. careful.

23 related questions found

Is the basic precise literal meaning of the word?

Connotation refers to the wide array of positive and negative associations that most words naturally carry with them, whereas denotation is the precise, literal definition of a word that might be found in a dictionary.

When we use precise in a sentence?

1. She gave me clear and precise directions. 2. I can’t give you a precise date.

What is an example of precise?

The definition of precise is exact. An example of precise is having the exact amount of money needed to buy a notebook.

What is precise in your own words?

1 : exactly or sharply defined or stated. 2 : minutely exact. 3 : strictly conforming to a pattern, standard, or convention.

What is precise word choice?

Precision. A very important part of word choice is precision. Through precise word selection, you can increase the clarity of your argument by enabling your readers to grasp your intended meaning quickly and accurately. … Therefore, you also need to choose words that will convey your ideas clearly to your readers.

What’s the difference between precise and accurate?

Accuracy is the degree of closeness to true value. Precision is the degree to which an instrument or process will repeat the same value. In other words, accuracy is the degree of veracity while precision is the degree of reproducibility.

How do you write a precise sentence?

Writing Concise, Precise Sentences

- Be specific and direct. If one word can replace a longer descriptive phrase, use the one word. …

- Cut unnecessary words. Words that don’t contribute to the meaning of a sentence don’t provide value to the reader. …

- Combine related sentences.

What’s a precise noun?

An exact noun is a noun that is specific rather than generic. For example, the words ‘dog,’ ‘cat,’ and ‘bird’ are common nouns that can refer to any of those creatures. On the other hand, the words ‘beagle,’ ‘tabby,’ and ‘raven’ are exact nouns because they refer to a specific type of those particular common nouns.

What is precise language?

Precise language is using exact, specific words. Writers use precise language to give readers particular images in their heads.

What do you call the literal meaning of the word?

The literal meaning of a word is its original, basic meaning: The literal meaning of «television» is «seeing from a distance». You will need to show more than just a literal understanding of the text. Compare. figurative (LANGUAGE)

What is an example of literal meaning?

Literal language is used to mean exactly what is written. For example: “It was raining a lot, so I rode the bus.” In this example of literal language, the writer means to explain exactly what is written: that he or she chose to ride the bus because of the heavy rain. … It was raining cats and dogs, so I rode the bus.

What does literal meaning mean in English?

adjective. in accordance with, involving, or being the primary or strict meaning of the word or words; not figurative or metaphorical: the literal meaning of a word.

What are common nouns?

A common noun is the generic name for a person, place, or thing in a class or group. Unlike proper nouns, a common noun is not capitalized unless it either begins a sentence or appears in a title.

What is noun of compare?

compare is a verb, comparison is a noun, comparable is an adjective:Compare the two items to see which is cheaper. She made a comparison of the two items.

What is the noun of exact?

exaction. The act of demanding with authority, and compelling to pay or yield; compulsion to give or furnish; a levying by force. extortion. That which is exacted; a severe tribute; a fee, reward, or contribution, demanded or levied with severity or injustice.

What are precise words and phrases?

Precise language is the use of exact nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc., to help produce vivid mental pictures without resorting to using too many words to convey thoughts. When you use specific words in your writing, you create strong, compelling images in the minds of the readers.

What should be avoided in precis writing?

For a precis writing, avoid using contractions and abbreviations. Write the full form of any given words only. Avoid being jerky. This will show that you have not understood the passage properly and have started writing a precis.

What is precise but not accurate?

Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the true or accepted value. Precision refers to how close measurements of the same item are to each other. Precision is independent of accuracy. … If all of the darts land very close together, but far from the bulls-eye, there is precision, but not accuracy (SF Fig.

Which is better precision or recall?

Precision can be seen as a measure of quality, and recall as a measure of quantity. Higher precision means that an algorithm returns more relevant results than irrelevant ones, and high recall means that an algorithm returns most of the relevant results (whether or not irrelevant ones are also returned).

Which is more important accuracy or precision?

Accuracy is something you can fix in future measurements. Precision is more important in calculations. When using a measured value in a calculation, you can only be as precise as your least precise measurement.