Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Prof. Jazmyne Welch

Score: 4.9/5

(62 votes)

Italic is a typeface or font style that slants to the right. Most writers use italic type to emphasize certain words or phrases. You can use the word italic as a noun or an adjective, usually in the form «italic type,» or italics. Either way, it describes the kind of cursive-styled typeface that leans at an angle.

What is an example of an italicized word?

Onomatopoeic words (or words that sound like sounds) are usually italicized, as well. For example, “The book landed on the floor with a hearty thwack!” In this case, if an exclamation point is used, it should also be italicized. The exact rules for using italics depend on the specific style guide you’re using.

How do I write in italics in word?

To make your selected text italic or start writing text in italic, press the Ctrl + I keys on your keyboard. To make your selected text underlined or start writing underlined text, press the Ctrl + U keys on your keyboard.

What does italics mean in writing?

Most word processors can produce italics, which are slanted letters — like these. … Most commonly, italics are used for emphasis or contrast — that is, to draw attention to some particular part of a text.

What is italics in writing?

Italics are used primarily to denote titles and names of particular works or objects in order to allow that title or name to stand out from the surrounding sentence. Italics may also be used for emphasis in writing, but only rarely.

32 related questions found

When should I use italics in writing?

When to Use Italics in Your Writing

- To emphasize something.

- For titles of standalone works, such as books and movies.

- For vehicle names, such as ships.

- To show that a word is borrowed from another language.

- For the Latin “scientific” names of plant and animal species.

How do you explain italics?

When you italicize your writing, you print or type in the slanted letters called «italics.» You can italicize a word in a sentence when you want to emphasize it. People italicize for various reasons: they might italicize the title of a book, or a section of dialogue that’s yelled by a character in a story.

What is italic sentence?

Italics is a style of typeface in which the letters slant to the right: This sentence is printed in italics. … Apart from the uses cited below for titles and naming conventions, italics are used to give emphasis to words and phrases in a sentence.

What does italic look like?

An italic font is a cursive, slanted typeface. A font is a specific size, style, and weight of a typeface used in printing and writing. When we keyboard text, we typically use a roman font, where the text is upright. By comparison, an italic font is slightly slanted to the right.

How do you talk in italics?

Here are 4 tips that should help you perfect your pronunciation of ‘italics’:

- Break ‘italics’ down into sounds: [I] + [TAL] + [IKS] — say it out loud and exaggerate the sounds until you can consistently produce them.

- Record yourself saying ‘italics’ in full sentences, then watch yourself and listen.

What does italic print look like?

Italic is defined as a printed letter that is slanted upward to the right, or a language of the Indo-European language family. An example of italic is the font used in the word this: this. … (typography) A typeface in which the letters slant to the right.

Can you use italics for quotes?

Generally and grammatically speaking, put titles of shorter works in quotation marks but italicize titles of longer works. For example, put a “song title” in quotation marks but italicize the title of the album it appears on.

How do you show italics in plain text?

How do you show italics in plain text?

- Insert a slash character before and after the word or phrase. Example: /This is important/

- Enclose the word or phrase in asterisks to signify bolded type. Example: *This is important*

- Type underline characters before and after the word or phrase to mimic underscoring.

How do you emphasize a word?

Still, especially for academic writing, italics or underlining is the preferred way to emphasize words or phrases when necessary. Writers usually choose one or the other method and use it consistently throughout an individual essay. In the final, published version of an article or book, italics are usually used.

What are famous sayings?

The Most Famous Quotes

- “Fortune favors the bold.” – Virgil.

- “I think, therefore I am.” – René Descartes.

- “Time is money.” – …

- “I came, I saw, I conquered.” – …

- “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” – …

- “Practice makes perfect.” – …

- “Knowledge is power.” – …

- “Have no fear of perfection, you’ll never reach it.” –

Which word is the best synonym for the word italics?

Synonyms & Antonyms of italicize

- accentuate,

- bring out,

- emphasize,

- stress,

- underline,

- underscore.

What is the synonyms for nice fun indeed?

yes, certainly, assuredly, emphatically, absolutely, exactly, precisely, of course, definitely, quite, positively, naturally, without doubt, without a doubt, without question, unquestionably, undoubtedly, doubtlessly, indubitably. by all means.

What are compound words?

When two words are used together to yield a new meaning, a compound is formed. Compound words can be written in three ways: as open compounds (spelled as two words, e.g., ice cream), closed compounds (joined to form a single word, e.g., doorknob), or hyphenated compounds (two words joined by a hyphen, e.g., long-term).

What is the difference between italics and quotation marks?

Italics are used for large works, names of vehicles, and movie and television show titles. Quotation marks are reserved for sections of works, like the titles of chapters, magazine articles, poems, and short stories. Let’s look at these rules in detail, so you’ll know how to do this in the future when writing.

Is italic A font style?

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. … The name comes from the fact that calligraphy-inspired typefaces were first designed in Italy, to replace documents traditionally written in a handwriting style called chancery hand.

Which is not a font style?

Superscript is not related to the font style. It is a letter, character number or symbol that is set slightly for the normal line of type. It is generally smaller than the body of the text and detailed occurs at the baseline.

Which is the best font style?

The 10 best fonts

- Akzidenz-Grotesk. Probably the best typeface ever designed. …

- New Baskerville. Probably the best serif typeface ever designed. …

- DIN 1451. …

- Franklin Gothic. …

- HTF Didot. …

- Gotham. …

- Knockout. …

- Gill Shadow.

How do you italicize on iPhone?

How to italicize text on an iPhone in Notes

- Open the Notes app.

- Type your text into a note.

- Select the word you want to italicize by double tapping the word. …

- Tap «BIU.»

- Tap «Italic.»

- Alternatively, after you’ve selected your word(s), you can also tap on «Aa» above your keyboard. …

- Tap «I» to italicize.

How do you distinguish a term of art in legal writing?

A term of art is a phrase that has become so well accepted and pervasive in a particular field that it is no longer considered proprietary to its original author.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about printing. For the handwriting style, see Italic script.

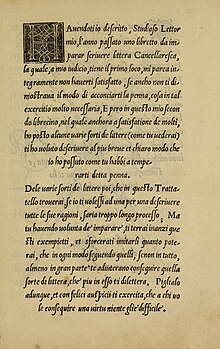

Ludovico Arrighi’s early «chancery italic» typeface, c. 1527. At that time italic was only used for the lower case and not for capitals.

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting.[1][2][3] Along with blackletter and roman type, it served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right, like this. Different glyph shapes from roman type are usually used – another influence from calligraphy – and upper-case letters may have swashes, flourishes inspired by ornate calligraphy.

Historically, italics were a distinct style of type used entirely separately from roman type, but they have come to be used in conjunction—most fonts now come with a roman type and an italic type. In this usage, italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed text, to identify many types of creative works, to cite foreign words or phrases, or, when quoting a speaker, a way to show which words they stressed. One manual of English usage described italics as «the print equivalent of underlining»; in other words, underscore in a manuscript directs a typesetter to use italic.[4]

In fonts which do not have true italics, oblique type may be used instead. The difference between true italics and oblique type is that true italics have some letterforms different from the roman type, but in oblique type letters are just slanted without changing the roman type form.

The name comes from the fact that calligraphy-inspired typefaces were first designed in Italy, to replace documents traditionally written in a handwriting style called chancery hand. Aldus Manutius and Ludovico Arrighi (both between the 15th and 16th centuries) were the main type designers involved in this process at the time.

History[edit]

Sample of Niccoli’s cursive script, which developed into Italic type.

Catherine of Siena, Epistole («Letters»), published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio in September 1500:[5] illustrated table in which appear the first words ever printed in italics: iesus, inside the heart in the left hand and iesu dolce iesu amore inside the book in the right hand.[6]

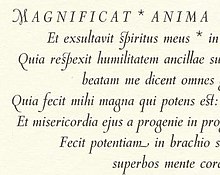

Aldus Manutius’ italic, in a 1501 edition of Virgil.[7] The initial is hand-lettered.

Italic type was first used by Aldus Manutius and his press in Venice in 1500.[8]

Manutius intended his italic type to be used not for emphasis but for the text of small, easily carried editions of popular books (often poetry), replicating the style of handwritten manuscripts of the period. The choice of using italic type, rather than the roman type in general use at the time, was apparently made to suggest informality in editions designed for leisure reading.[a] Manutius’ italic type was cut by his punchcutter Francesco Griffo (who later following a dispute with Manutius claimed to have conceived it). It replicated handwriting of the period following from the style of Niccolò de’ Niccoli, possibly even Manutius’ own.[9][10]

The first use in a complete volume was a 1501 edition of Virgil dedicated to Italy, although it had been briefly used in the frontispiece of a 1500 edition of Catherine of Siena’s letters.[11] In 1501, Aldus wrote to his friend Scipio:

We have printed, and are now publishing, the Satires of Juvenal and Persius in a very small format, so that they may more conveniently be held in the hand and learned by heart (not to speak of being read) by everyone.

Manutius’ italic was different in some ways from modern italics, being conceived for the specific use of replicating the layout of contemporary calligraphers like Pomponio Leto and Bartolomeo Sanvito. The capital letters were upright capitals on the model of Roman square capitals, shorter than the ascending lower-case italic letters, and were used at the start of each line followed by a clear space before the first lower-case letter.[12] While modern italics are often more condensed than roman types, historian Harry Carter describes Manutius’ italic as about the same width as roman type.[13] To replicate handwriting, Griffo cut at least sixty-five tied letters (ligatures) in the Aldine Dante and Virgil of 1501.[12] Italic typefaces of the following century used varying but reduced numbers of ligatures.[12]

Italic type rapidly became very popular and was widely (and inaccurately) imitated. The Venetian Senate gave Aldus exclusive right to its use, a patent confirmed by three successive Popes, but it was widely counterfeited as early as 1502.[14] Griffo, who had left Venice in a business dispute, cut a version for printer Girolamo «Gershom» Soncino, and other copies appeared in Italy and in Lyons. The Italians called the character Aldino, while others called it Italic. Italics spread rapidly; historian H. D. L. Vervliet dates the first production of italics in Paris to 1512.[8][12] Some printers of Northern Europe used home-made supplements to add characters not used in Italian, or mated it to alternative capitals, including Gothic ones.[8][12]

Jan van Krimpen’s Cancelleresca Bastarda, a twentieth-century revival of the chancery italic style.

Besides imitations of Griffo’s italic and its derivatives, a second wave appeared of «chancery» italics, most popular in Italy, which Vervliet describes as being based on «a more deliberate and formal handwriting [with] longer ascenders and descenders, sometimes with curved or bulbous terminals, and [often] only available in the bigger sizes.»[8][15][16] Chancery italics were introduced around 1524 by Arrighi, a calligrapher and author of a calligraphy textbook who began a career as a printer in Rome, and also by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente of Venice, with imitations rapidly appearing in France by 1528.[13] Chancery italics faded as a style over the course of the sixteenth century, although revivals were made beginning in the twentieth century.[b] Chancery italics may have backward-pointing serifs or round terminals pointing forwards on the ascenders.[15]

Italic capitals with a slope were introduced in the sixteenth century. The first printer known to have used them was Johann or Johannes Singriener in Vienna in 1524, and the practice spread to Germany, France and Belgium.[8][23] Particularly influential in the switch to sloped capitals as a general practice was Robert Granjon, a prolific and extremely precise French punchcutter particularly renowned for his skill in cutting italics.[8] Vervliet comments that among punchcutters in France «the main name associated with the change is Granjon’s.»[8]

The evolution of use of italic to show emphasis happened in the sixteenth century and was a clear norm by the seventeenth. The trend of presenting types as matching in typefounders’ specimens developed also over this period.[24] Italics developed stylistically over the following centuries, tracking changing tastes in calligraphy and type design.[25][26][27] One major development that slowly became popular from the end of the seventeenth century was a switch to an open form h matching the n, a development seen in the Romain du roi type of the 1690s, replacing the folded, closed-form h of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century italics, and sometimes simplification of the entrance stroke.[28][29]

Examples[edit]

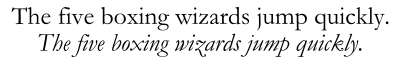

True italic styles are traditionally somewhat narrower than roman fonts. Here is an example of normal (roman) and true italics text:

Example text set in both roman and italic type

In oblique text, the same type is used as in normal type, but slanted to the right:

Usage[edit]

A common view of when to use italics and bold text. An additional option for emphasis is to use small capitals for a word or name to stand out.[30][31]

- Emphasis: «Smith wasn’t the only guilty party, it’s true». This is called stress in speech.

- The titles of works that stand by themselves, such as books (including those within a larger series), albums, paintings, plays, television shows, movies, and periodicals: «He wrote his thesis on The Scarlet Letter«. Works that appear within larger works, such as short stories, poems, newspaper articles, songs, and television episodes are not italicised, but merely set off in quotation marks. When italics are unavailable, such as on a typewriter or websites that do not support formatting, an underscore or quotes are often used instead.[32]

- The names of ships: «The Queen Mary sailed last night.»

- Foreign words, including the Latin binomial nomenclature in the taxonomy of living organisms: «A splendid coq au vin was served»; «Homo sapiens«.

- The names of newspapers and magazines: «My favorite magazine is Psychology Today, and my favorite newspaper is the Chicago Tribune.»

- Mentioning a word as an example of a word rather than for its semantic content (see use–mention distinction): «The word the is an article».

- Using a letter or number mentioned as itself:

- John was annoyed; they had forgotten the h in his name once again.

- When she saw her name beside the 1 on the rankings, she finally had proof that she was the best.

- Using a letter or number mentioned as itself:

- Introducing or defining terms, especially technical terms or those used in an unusual or different way:[33] «Freudian psychology is based on the ego, the super-ego, and the id.»; «An even number is one that is a multiple of 2.»

- Sometimes in novels to indicate a character’s thought process: «This can’t be happening, thought Mary.»

- Italics are used in the King James Version to de-emphasise words «that have no equivalent in the original text but that are necessary in English»:[34] «And God saw the light, that it was good».[35]

- Algebraic symbols (constants and variables) are conventionally typeset in italics: «The solution is x = 2.»

- Symbols for physical quantities and mathematical constants: «The speed of light, c, is approximately equal to 3.00×108 m/s.»[36][37][38]

- In biology, gene names (for example, lacZ) are written in italics whereas protein names are written in roman type (e.g. β-galactosidase, which the lacZ gene codes for).[39][40]

- Italics are frequently used in comics. A letterer may opt to use italic text for a variety of situations, such as internal monologues, captions, words from other languages, and text rendered inside certain types of speech balloons (such as thought balloons). Bolded words are commonly also rendered in italic.[41]

- In older English usage, writers italicised words much more freely, for emphasis, for instance John Donne:

No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were …

Oblique type compared to italics[edit]

Three sans-serif italics. News Gothic, a 1908 grotesque design, has an oblique ‘italic’, like many designs of the period. Gothic Italic no. 124, an 1890s grotesque, has a crisp true italic resembling Didone serif families of the period.[42] Seravek, a modern humanist family, has a more informal italic in the style of handwriting.

Oblique type (or slanted roman, sloped roman) is type that is slanted, but lacking cursive letterforms, with features like a non-descending f and double-storey a, unlike «true italics». Many sans-serif typefaces use oblique designs (sometimes called «sloped roman» styles) instead of italic ones; some have both italic and oblique variants. Type designers have described oblique type as less organic and calligraphic than italics, which in some situations may be preferred.[43] Contemporary type designer Jeremy Tankard stated that he had avoided a true italic a and e in his sans-serif Bliss due to finding them «too soft», while Hoefler and Frere-Jones have described obliques as more «keen and insistent» than true italics.[44][45] Adrian Frutiger has described obliques as more appropriate to the aesthetic of sans-serifs than italics.[46] In contrast, Martin Majoor has argued that obliques do not contrast enough from the regular style.[47]

Almost all modern serif fonts have true italic designs. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of type foundries such as American Type Founders and Genzsch & Heyse offered serif typefaces with oblique rather than italic designs, especially display typefaces but these designs (such as Genzsch Antiqua) have mostly disappeared.[48][49][50] An exception is American Type Founders’ Bookman, offered in some releases with the oblique of its metal type version.[51] An unusual example of an oblique font from the inter-war period is the display face Koch Antiqua. With a partly oblique lower case, it also makes the italic capitals inline in the style of blackletter capitals in the larger sizes of the metal type. It was developed by Rudolph Koch, a type designer who had previously specialised in blackletter font design (which does not use italics); Walter Tracy described his design as «uninhibited by the traditions of roman and italic».[52]

The printing historian and artistic director Stanley Morison was for a time in the inter-war period interested in the oblique type style, which he felt stood out in text less than a true italic and should supersede it. He argued in his article Towards an Ideal Italic that serif book typefaces should have as the default sloped form an oblique and as a complement a script typeface where a more decorative form was preferred.[53] He made an attempt to promote the idea by commissioning the typeface Perpetua from Eric Gill with a sloped roman rather than an italic, but came to find the style unattractive; Perpetua’s italic when finally issued had the conventional italic a, e and f.[54][55] Morison wrote to his friend, type designer Jan van Krimpen, that in developing Perpetua’s italic «we did not give enough slope to it. When we added more slope, it seemed that the font required a little more cursive to it.»[48][c] A few other type designers replicated his approach for a time: van Krimpen’s Romulus and William Addison Dwiggins’ Electra were both released with obliques.[d] Morison’s Times New Roman typeface has a very traditional true italic in the style of the late eighteenth century, which he later wryly commented owed «more to Didot than dogma».[58]

Some serif designs primarily intended for headings rather than body text are not provided with an italic, Engravers and some releases of Cooper Black and Baskerville Old Style being common examples of this. In addition, computer programmes may generate an ‘italic’ style by simply slanting the regular style if they cannot find an italic or oblique style, though this may look awkward with serif fonts for which an italic is expected. Professional designers normally do not simply tilt fonts to generate obliques but make subtle corrections to correct the distorted curves this introduces. Many sans-serif families have oblique fonts labelled as italic, whether or not they include «true italic» characteristics.

More complex usage[edit]

Italics within italics[edit]

Straight italic type within normal italics (Latin and Cyrillic)

If something within a run of italics needs to be italicised itself, the type is normally switched back to non-italicized (roman) type: «I think The Scarlet Letter had a chapter about that, thought Mary.» In this example, the title («The Scarlet Letter«) is within an italicised thought process and therefore this title is non-italicised. It is followed by the main narrative that is outside both. It is also non-italicised and therefore not obviously separated from the former. The reader must find additional criteria to distinguish between these. Here, apart from using the attribute of italic–non-italic styles, the title also employs the attribute of capitalization. Citation styles in which book titles are italicised differ on how to deal with a book title within a book title; for example, MLA style specifies a switch back to roman type, whereas The Chicago Manual of Style (14.94) specifies the use of quotation marks (A Key to Whitehead’s «Process and Reality»). An alternative option is to switch to an ‘upright italic’ style if the typeface used has one; this is discussed below.

Left-leaning italics[edit]

A ‘backslanted’ italic fat face typeface, made for display use by the Figgins foundry of London. The typeface is an example of the increasingly attention-grabbing, bold and dramatic fonts becoming popular in British display typography in the early nineteenth century.

Left-leaning italics are now rare in Latin script, where they are mostly used for the occasional attention-grabbing effect.[59][60] They were once more common, however, being used for example in legal documents.[61]

They are more common in Arabic script.

4 shapes of Adobe Arabic font (Normal, Italic, Bold, Bold-Italic)

4 shapes of Farsi font (Normal, Iranic, Bold, Bold-Iranic)

In certain Arabic fonts (e.g.: Adobe Arabic, Boutros Ads), the italic font has the top of the letter leaning to the left, instead of leaning to the right. Some font families, such as Venus, Roemisch, Topografische Zahlentafel, include left leaning fonts and letters designed for German cartographic map production, even though they do not support Arabic characters.[62]

Iranic font style[edit]

In the 1950s, Gholamhossein Mosahab invented the Iranic font style, a back-slanted italic form to go with the right-to-left direction of

the script.[63]

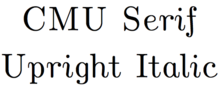

Upright italics[edit]

Since italic styles clearly look different from regular (roman) styles, it is possible to have ‘upright italic’ designs that have a cursive style but remain upright. In Latin-script countries, upright italics are rare but are sometimes used in mathematics or in complex texts where a section of text already in italics needs a ‘double italic’ style to add emphasis to it. Donald Knuth’s Computer Modern has an alternate upright italic as an alternative to its standard italic, since its intended use is mathematical typesetting.

Font families with an upright or near-upright italic only include Jan van Krimpen’s Romanée, Eric Gill’s Joanna, Martin Majoor’s FF Seria and Frederic Goudy’s Deepdene. The popular book typeface Bembo has been sold with two italics: one reasonably straightforward design that is commonly used today, and an alternative upright ‘Condensed Italic’ design, far more calligraphic, as a more eccentric alternative.

This italic face was designed by Alfred Fairbank and named «Bembo Condensed Italic», Monotype series 294.[64][18][19] Some Arts and Crafts movement-influenced printers such as Gill also revived the original italic system of italic lower-case only from the nineteenth century onwards.[65]

Parentheses[edit]

Monotype Garamond’s italic replicates the work of 17th-century punchcutter Jean Jannon quite faithfully, with a variable slant on the italic capitals.[66]

The Chicago Manual of Style suggests that to avoid problems such as overlapping and unequally spaced characters, parentheses and brackets surrounding text that begins and ends in italic or oblique type should also be italicised (as in this example). An exception to this rule applies when only one end of the parenthetical is italicised (in which case roman type is preferred, as on the right of this example).

In The Elements of Typographic Style, however, it is argued that since Italic delimiters are not historically correct, the upright versions should always be used, while paying close attention to kerning.

Substitutes[edit]

In media where italicization is not possible, alternatives are used as substitutes:

- In typewritten or handwritten text, underlining is typically used.

- In plain-text computer files, including e-mail communication, italicised words are often indicated by surrounding them with slashes or other matched delimiters. For example:

- I was /really/ annoyed.

- They >completely< forgot me!

- I had _nothing_ to do with it. (Commonly interpreted as underlining, which is an alternative to italics.)

- It was *absolutely* horrible. (Commonly interpreted as bold. This and the previous example signify italic in Markdown, where bolding uses **double asterisks**, and underlining uses __double underscores__.)

- Where the italics do not indicate emphasis, but are marking a title or where a word is being mentioned, quotation marks may be substituted:

- The word «the» is an article.

- The term «even number» refers to a number that is a multiple of 2.

- The novel «Fahrenheit 451» was written by Ray Bradbury.

OpenType[edit]

OpenType has the ital feature tag to substitute a character to italic form with single font. In addition, the OpenType Font Variation has ital axis for the transition between italic and non-italic forms and slnt axis for the oblique angle of characters.

Web pages[edit]

In HTML, the <i> element is used to produce italic (or oblique) text. When the author wants to indicate emphasised text, modern Web standards recommend using the <em> element, because it conveys that the content is to be emphasised, even if it cannot be displayed in italics. Conversely, if the italics are purely ornamental rather than meaningful, then semantic markup practices would dictate that the author use the Cascading Style Sheets declaration font-style: italic; along with an appropriate, semantic class name instead of an <i> or <em> element.

Unicode[edit]

In Unicode, the Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols block includes Latin and Greek letters in italics and boldface. However, Unicode expressly recommends against using these characters in general text in place of presentational markup.[67]

See also[edit]

- Boldface

Notes[edit]

- ^ It has been suggested that his choice to publish such small, cheap editions was the result of a recession beginning in 1500, the result of war with the Ottoman Empire.

- ^ Notable revivals include Bembo Narrow Italic, Centaur Italic or Arrighi, Poetica and Requiem.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

- ^ Spelling modernised to avoid confusion–Morison wrote ‘fount’, the usual spelling in British English at the time.

- ^ Electra was later reissued–although not in Britain–with a true italic, which is the only form most digitisations include. An exception is Jim Parkinson’s Aluminia revival, which includes both.[56] Romulus was issued on Morison’s plan with an oblique a script typeface companion, Cancelleresca Bastarda, which has longer ascenders and descenders than Romulus does. Digital period type designer James Puckett describes the obliques on both Romulus and Electra as «spectacular failures [which] pretty much killed the idea for serifed types.»[57]

References[edit]

- ^ Ewan Clayton (5 September 2013). The Golden Thread: The Story of Writing. Atlantic Books. pp. 104–6. ISBN 978-1-78239-034-3.

- ^ Gaultney, Victor. «Designing Italics: Approaches to the design of contemporary secondary text typefaces (PhD thesis)». Victor Gaultney. University of Reading. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. «Italics Examined». Hoefler & Co. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Truss, Lynne (2004), Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, New York: Gotham Books, p. 146, ISBN 978-1-59240-087-4

- ^ Bühler, Curt (1970). «False Information in the Colophons of Incunabula». Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 114 (5): 405. ISBN 9781422371374. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

Manutius dated his edition…as 15 September 1500, but included in the volume is a letter…with date of September 19.

- ^ «Columbia University Libraries Online Exhibitions | Type to Print: The Book & The Type Specimen Book». exhibitions.library.columbia.edu. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ «Aldus Manutius». Pioneers of Print. University of Manchester. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hendrik D. L. Vervliet (2008). The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-century Typefaces. BRILL. pp. 287–319. ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1.

- ^ Oxford University Press (1 June 2010). Aldo Manuzio (Aldus Manutius): Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-19-980945-5.

- ^ Berthold Louis Ullman, The origin and development of humanistic script, Rome, 1960, p. 77

- ^ «Roman vs Italic». Type to Print: The Book & The Type Specimen Book. Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Kaufmann, Ueli (11 October 2015). «The design and spread of Froben’s early Italics». Department of Typography & Graphic Communication. University of Reading. Archived from the original on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ a b Carter, Harry (1969). A View of Early Typography. pp. 117–126. ISBN 978-0-19-818137-8.

If Aldus hoped, as it is commonly said that he did, but he never said, that cursive letterforms would save space, he must have been disappointed by the result: a Roman type on the same body gets in just as much. It is a beautiful and legible typeface.

- ^ Updike, D.B. (1927), Printing Types: Their History, Form and Use, Harvard University

- ^ a b Morison, Stanley; Johnson, Alfred (2009). «3: The Chancery Types of Italy and France». In McKitterick, David John (ed.). Selected essays on the history of letter-forms in manuscript and print. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–45. ISBN 978-0-521-18316-1. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Morison, Stanley (1973). A Tally of Types. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-0-521-09786-4.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. «Requiem». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b «Fairbank». Monotype. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b «Fairbank». MyFonts. Monotype.

- ^ «Fairbanks Italic specimen» (PDF). Monotype. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ «Alfred Fairbank» (PDF). Klingspor Museum. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ «Poetica». MyFonts. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Clair, Colin (1969). A Chronology of Printing. New York, Praeger. p. 43.

- ^ Lane, John (1983). «The Types of Nicholas Kis». Journal of the Printing Historical Society: 47–75.

- ^ Johnson, Alfred F. (1930). «The Evolution of the Modern-Face Roman». The Library. s4-XI (3): 353–377. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XI.3.353.

- ^ Dreyfus, John (1950). «The Baskerville Punches 1750–1950». The Library. s5-V (1): 26–48. doi:10.1093/library/s5-V.1.26.

- ^ Ewan Clayton (11 February 2014). The Golden Thread: A History of Writing. Counterpoint LLC. pp. 205–210. ISBN 978-1-61902-242-3.

- ^ Morison, Stanley (1937). «Type Designs of the Past and Present, Part 3». PM: 17–81. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Mosley, James. «Comments on Typophile thread». Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

One of the distinctive things about French calligraphy of [the 1680s] is that the lead-in stroke of letters like i, m, n and so on have flat, rather ‘roman’, serifs, making them look a bit like a ‘sloped roman’…Fournier used it fifty years later in his ‘new style’ italics, and later so did Firmin Didot. And that French flat serif also turns up in…the italic to Times New Roman.

- ^ Butterick, Matthew. «Bold or italics?». Practical Typography. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Butterick, Matthew. «Small caps». Practical Typography. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ «Formatting Book Titles in the Digital Age». dailywritingtips.com.

- ^ University of Minnesota Style Manual, University of Minnesota, 18 July 2007, archived from the original on 24 March 2010, retrieved 22 October 2009

- ^ Norton, David (2005). A Textual History of the King James Bible. Cambridge University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780521771009. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Genesis 1:4

- ^ Mills, I. M.; Metanomski, W. V. (December 1999), On the use of italic and roman fonts for symbols in scientific text (PDF), IUPAC Interdivisional Committee on Nomenclature and Symbols, retrieved 9 November 2012. This document was slightly revised in 2007* and full text included in the Guidelines For Drafting IUPAC Technical Reports And Recommendations and also in the 3rd edition of the IUPAC Green Book Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. *Refer to Chemistry International. Volume 36, Issue 5, Pages 23–24, ISSN (Online) 1365-2192, ISSN (Print) 0193-6484, DOI: 10.1515/ci-2014-0529, September 2014

- ^ See also Typefaces for Symbols in Scientific Manuscripts Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, NIST, January 1998. This cites the family of ISO standards 31-0:1992 to 31-13:1992.

- ^ «More on Printing and Using Symbols and Numbers in Scientific and Technical Documents Archived 29 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine». Chapter 10 of NIST Special Publication 811 (SP 811): Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI). 2008 Edition, by Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, US. March 2008. 76 pages. This cites the ISO standards 31-0:1992 and 31-11:1992, but notes «Currently ISO 31 is being revised […]. The revised joint standards ISO/IEC 80000-1—ISO/IEC 80000-15 will supersede ISO 31-0:1992—ISO 31-13.».

- ^ «The NCBI Style Guide: Style Points and Conventions». National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ «Guidelines for Formatting Gene and Protein Names». BioScience Writers. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ «Comic Book Grammar & Tradition». Blambot Comic Book Fonts. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Specimens of type, borders, ornaments, brass rules and cuts, etc. : catalogue of printing machinery and materials, wood goods, etc. American Type Founders Company. 1897. p. 340. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Majoor, Martin. «Inclined to be dull». Eye magazine. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Tankard, Jeremy. «Bliss». Jeremy Tankard Typography. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Tobias; Hoefler, Jonathan. «Whitney». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Frutiger, Adrian (8 May 2014). Typefaces: The Complete Works (2nd ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 260. ISBN 978-3038212607.

- ^ Majoor, Martin. «My Type Design Philosophy». Typotheque. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b Walter Tracy (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. pp. 61–4. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- ^ «Typophile discussion». Typophile. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Devroye, Luc. «Friedrich Bauer». Type Design Information. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. «Bookmania». Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Tracy, Walter. Letters of Credit. pp. 162–3.

- ^ Morison, Stanley. Towards an Ideal Italic.

- ^ «Monotype Imaging: Perpetua». Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Lo Celso, Alejandro. «Serial Type Families» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2014.

- ^ «Recasting Electra as Aluminia». Letterform Archive. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Puckett, James. «Draughtsman’s Alphabets published by Keuffel & Esser». dailytypespecimen. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Morison, Stanley. «Changing the Times». Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ William E. Ryan; Theodore E. Conover (2004). Graphic Communications Today. Cengage Learning. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7668-2075-3.

- ^ «Nitro & Turbo — Overview». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Reverse italics at StudioType

- ^ «Venus». Fonts in Use. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Esfahbod, Behdad; Roozbeh Pournader (March 2002). «FarsiTeX and the Iranian TeX Community» (PDF). TUGboat. 23 (1): 41–45. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Bixler, M & W. «Bembo Condensed Italic specimen». Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Harling, Robert (1975). The Letter Forms and Type Designs of Eric Gill (1st U.S. ed.). Westerham, Kent: Published by Eva Svensson, and printed by the Westerham Press. pp. 51–8. ISBN 978-0-903696-04-3.

- ^ Warde, Beatrice (1926). «The ‘Garamond’ Types». The Fleuron: 131–179.

- ^ «22.2 Letterlike Symbols». The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA: Unicode, Inc. March 2020.

External links[edit]

- The Essential Italic on YouTube, Victor Gaultney (presentation to ATypI)

- Hamilton, Frederick W. (1918). The Uses of Italic: A Primer of Information Regarding the Origin and Uses of Italic Letters at Project Gutenberg

Italic is a typeface or font style that slants to the right. Most writers use italic type to emphasize certain words or phrases. You can use the word italic as a noun or an adjective, usually in the form “italic type,” or italics. Either way, it describes the kind of cursive-styled typeface that leans at an angle.

Subsequently, What’s App text tricks?

Monospace

- Android: Tap and hold the text you’re entering in the text field, then choose Bold, Italic, or More . Tap More to choose Strikethrough or Monospace.

- iPhone: Tap the text you’re entering in the text field > Select or Select All > B_I_U. Then, choose Bold, Italic, Strikethrough, or Monospace.

Accordingly What does italic look like?

An italic font is a cursive, slanted typeface. A font is a specific size, style, and weight of a typeface used in printing and writing. When we keyboard text, we typically use a roman font, where the text is upright. By comparison, an italic font is slightly slanted to the right.

Beside above, What is non italic called? The technical name for non-italic fonts is roman or romanized, so this is probably your best choice from the options you’ve given.

What are italics examples?

Italics can emphasize a single word or phrase. For example: “Are you going to eat that?” or “I never said I wanted to go. I said I would consider it.”

also How do you make text bold? Make text bold

- Move your pointer to the Mini toolbar above your selection and click Bold .

- Click Bold in the Font group on the Home tab.

- Type the keyboard shortcut: CTRL+B.

How do I change the text style on my phone?

Changing Built-In Font Settings

- In the “Settings” menu, scroll down and tap the “Display” option.

- The “Display” menu may vary depending on your Android device. …

- In the “Font Size and Style” menu, tap the “Font Style” button.

- You’ll have a list of pre-installed font styles available for you to choose from.

What is WhatsApp font style?

Whatsapp Font is → Helvetica®

What is a normal angle of italic words?

In general, italics tend to slant between 4–14 degrees. Most contemporary fonts slant between 6–9 degrees.

What is roman style?

R. The normal typography style in which the vertical lines of the characters are straight up and not on an angle. It is the opposite of italic, which uses slanted lines. The Four Typefaces. Many fonts come in normal (roman), bold, italic and bold italic variations.

Is Bold text rude?

Don’t abuse the bold, italics and underline styling.

While these features can be used to emphasize a point, too much of a good thing goes bad quickly. An email full of bold, italicized and underlined text could come across as aggressive, or even rude. If nothing else, it’s distracting and confusing.

Should I use bold or italics?

Bold text is used to describe strong, clear words. Italics can be used for giving certain emphasis on a particular word or phrase and it should be used sparingly. Don’t overuse italics as they will make your blog posts look cluttered, so only use them when you really need to stress something out.

When should you italicize a word?

Use Italics when you want to emphasize a certain word or phrase. A common use for italics is to draw attention to a particular part of a text in order to provide emphasis. If something is important or shocking, you might want to italicize that word or phrase so that your readers don’t miss it.

What is italic sentence?

Italics is a style of typeface in which the letters slant to the right: This sentence is printed in italics. … Apart from the uses cited below for titles and naming conventions, italics are used to give emphasis to words and phrases in a sentence.

What do italics mean in writing?

Most word processors can produce italics, which are slanted letters — like these. … Most commonly, italics are used for emphasis or contrast — that is, to draw attention to some particular part of a text.

What are the bold letters?

A set of type characters that are darker and heavier than normal. A bold font implies that each character was originally designed with a heavier appearance rather than created on the fly from a normal character. See boldface attribute.

What does words in bold mean?

Bold, bold face, or bold font is any text that is darkened to help emphasize a remark or comment. For example, this is bold text. If your browser supports bold text, the previous words “bold text” are in bold lettering.

How do I change text from bold to normal?

Figure E. Note: If you just need to convert to regular text, press Ctrl + B in the Find What box and then click in the Replace With box and press Ctrl + B twice. This tells Word to replace Bold with Not Bold.

How do I install custom fonts on Android?

Downloading, extracting and installing a custom font on your Android Device

- Extract the font to Android SDcard> iFont> Custom. Click ‘Extract’ to complete the extraction.

- The font will now be located in My Fonts as a custom font.

- Open it to preview the font and to install it on your device.

How do I change the letter style on my keyboard?

To change input language and the keyboard layout

- Tap and hold .

- Tap Input language & type.

- Tap each language to select as one of input languages.

- Tap to change the keyboard layout.

- Tap QWERTY keyboard, Phone keyboard, Handwriting, or Shape writer.

How do I download fonts to my phone?

Using Downloadable Fonts via Android Studio and Google Play services

- In the Layout Editor, select a TextView, and then under Properties, select fontFamily > More Fonts. Figure 2. …

- In the Source drop-down list, select Google Fonts.

- In the Fonts box, select a font.

- Select Create downloadable font and click OK.

How do I color my text on WhatsApp?

Change the color of a label: Tap a label > Edit > tap the color palette icon > Choose Color > tap Save.

How can I write my name in WhatsApp style?

On Android, tap and hold the message and choose the appropriate formatting option. Tap on the three-dot icon to view other options. On iPhone, tap and hold the text and select the option that states BIU. Then choose the formatting option from bold, italic, strikethrough, and monospace.

How do you type in bold on a phone?

Add text to your message. Double tap the text you want to format. Tap Format, then choose a formatting option like bolding, italics, or changing the font color.

Italics can be applied for various reasons, but it is always with the same goal: to mark text as different in some way. This difference can be a matter of emphasis, or it can indicate the title of a book or movie or other work, the scientific name of a species, or the name of a court case, among other things. Italics may also be used to highlight a key term or a word or phrase from another language.

There are also times when it’s important to understand that italics are not needed. A key term may get italics when it is first introduced but not after that. And many words and phrases that have been borrowed from another language will be familiar enough to readers to be left without italics.

The different ways to use italics can get confusing, which is why we designed The Chicago Manual of Style for PerfectIt—the add-in for Microsoft Word that we introduced to readers of Shop Talk last August—to teach these principles. It won’t find everything. However, it can help with each of the scenarios described above, and it can be customized to match your preferences.

PerfectIt’s Italics Check

Before exploring CMOS, it’s worth understanding how PerfectIt functions on its own.

PerfectIt works by scanning your Word documents for inconsistencies—in hyphenation, spelling, capitalization, numbers, and several other categories. For example, if it finds “long term” in one place and “long-term” in another, it will flag both so you can decide whether either of them needs to be fixed.

For italics, which are less predictable than hyphenation, PerfectIt uses a slightly different approach. Instead of checking everything, PerfectIt looks for a range of common words and phrases borrowed mainly from Latin, French, and German. These are terms that might be italicized according to some style guides but not others, so PerfectIt checks only those terms for consistency.

For example, if the Latin abbreviation “et al.” (and others) is italicized in some places in your document but not others, each instance of the term will be flagged. You’ll get the option to change the ones in regular text to italics:

Or you can change the ones in italics to regular text:

In Chicago style, the preference would be for regular text. Which brings us to Chicago Style for PerfectIt.

Italics for Non-English Terms in The Chicago Manual of Style for PerfectIt

According to CMOS 7.53–55, italics should be used for an isolated word or phrase from a language other than English unless it appears in a standard dictionary and would be familiar to most of your readers. A less familiar word or phrase would be italicized. An unfamiliar term that appears frequently in the text might be italicized on first use only.

The Chicago Manual of Style for PerfectIt builds on PerfectIt’s italics check by adding hundreds of terms from Latin, French, German, Spanish, Hebrew, Japanese, and other languages that are likely to appear in an English-language context.

Each of these terms is listed in Merriam-Webster—and therefore likely to be familiar in the context of an English-language document. Nonetheless, even within Merriam-Webster some terms are more familiar than others. The preference in PerfectIt for the more familiar of these is set to “no italics.” Less familiar terms will be flagged only if they are used inconsistently.

None, however, are set to prefer italics. Any list of unfamiliar terms from other languages would be endless. So it’s up to you to customize PerfectIt further (see below) if you’re working with terms from other languages that you want to ensure are italicized.

“Et al.” and other common Latin abbreviations should be familiar to most English speakers, so when Chicago Style is turned on in PerfectIt, it will flag “et al.”—but only when it appears in italics.

Clicking “Fix” will remove the italics.

Another example of a familiar term is the French phrase “faux pas,” which would also get flagged by Chicago Style for PerfectIt if it appears in italics:

But it’s important to review each term carefully. In this case, if you’re trying to enforce Chicago style, the italics are correct. That’s because a word or phrase referred to as such is an exception—as in “The expression faux pas.” So you’d want to ignore the software’s suggestion in that case.

To help with these rules and suggestions, PerfectIt gives you the option to “See more from CMOS 7.54”—which will bring up advice directly from the Manual:

If you still want more detail, clicking on any of the red numbers will take you directly to the applicable section in CMOS Online.

“Et al.” and “faux pas” are very common, but what about the legal terms “in absentia,” “in camera,” “in esse,” and “in flagrante delicto”? Or the French “amuse-bouche” or the Spanish “churro” or the Italian “loggia”? Each of those terms is still fairly common, so PerfectIt will flag any of them if they appear in italics.

Other terms in PerfectIt’s check, though they’re listed in Merriam-Webster, are a bit more obscure—for example, the French legal terms “cestui que trust,” “cestui que use,” and “cestui que vie.” PerfectIt is set to check those for consistency only. If you’ve been inconsistent with any of those terms, you will have to use your editorial judgment to decide whether to use italics or regular text—or italics on first use and regular text thereafter.

Terms That Are Always in Italics

CMOS recommends italics for a broad range of categories, including the titles of books and periodicals (and several other types of works), the scientific names for plant and animal species, the names of ships and other vessels, the names of court cases, and lettered rhyme schemes like abab.

Chicago Style for PerfectIt’s italics check includes some representative terms in each category. But it can’t include every title of every work and the name of every ship, species, and court case. Instead, it finds a few common ones in the hope that these will demonstrate the principles of Chicago style.

For example, the title of the novel Middlemarch, if it appears in regular text, will be flagged:

Some styles put the title of books in quotation marks, as in this example, so editors are likely to see this result in PerfectIt. When you do, you will need not only to click “Fix” (to apply the italics) but also to put your cursor in the text to delete the quotation marks. PerfectIt, like Word’s spelling and grammar checker, makes it easy to do this while you are running the program.

Customizing the Italics Check

Chicago Style for PerfectIt gives editors a lot of leeway to make their own choices. When one of PerfectIt’s suggestions doesn’t apply (as with that italic “faux pas”), you can simply ignore it and click “Next.” But you can also customize PerfectIt by creating a new style based on Chicago and modifying it to reflect your preferences.

Italics are in a separate tab in PerfectIt’s style sheet editor, so it’s easy to add terms and modify your preferences. For example, if you prefer italics for “in absentia,” you can change the setting from “no italics” to “always in italics.” Or if you prefer italics on first use only—or not to check that term at all—those are also options.

Adding terms is just as easy. It would be counterproductive to add thousands of titles of books and other works that should be in italics. But if there are any that come up frequently in your work (as, say, CMOS does at Shop Talk), they’re easy to add. Court cases, species names, the names of ships and other vessels—any of these can be added, with your preferences set however you’d like.

Depending on your needs, you can save multiple versions of Chicago Style for PerfectIt tailored to your house style or to specific projects or clients.

Learn More

Though the italics check in Chicago Style for PerfectIt includes a lot of terms, it’s not designed to find everything. Nor will it always agree with your preferences. Instead, it’s designed to teach the principles of Chicago style and to give you the chance to make good decisions, with help from CMOS.

To learn more about Chicago Style for PerfectIt or to apply it on your next document, click for details.

Close-up of dictionary page for “italics” by TungCheung / Adobe Stock.

Please see our commenting policy.

Table of Contents

- What does a word in italics mean?

- What are italics used for?

- What should be in italics?

- When should I use italics in writing?

- Can you italicize in text?

- How do you italicize a title?

- How do I italicize on my phone?

- Can I italicize on my iPhone?

- How do you do italics on messenger?

- Can you change font on messenger?

- What fonts does Facebook use?

- Does Messenger support markdown?

- How do you color your text on messenger?

- How do you get text effects on messenger?

- What do bold letters mean?

- How do I change my font in Facebook?

- What is best FB name?

- How do you change fonts?

- What are the 4 major font types?

- How do I change my font size?

- Why is my text font so big?

- How do I get my text back to normal size?

- How do I make text smaller?

When you italicize your writing, you print or type in the slanted letters called “italics.” You can italicize a word in a sentence when you want to emphasize it. Italicize and italics come from the Latin word for “Italian,” italicus.

What are italics used for?

Most commonly, italics are used for emphasis or contrast — that is, to draw attention to some particular part of a text.

What should be in italics?

Using Italics to Denote Titles, Foreign Words, and Proper Names. Use italics to denote the titles of long creative works. You should italicize the titles of long creative works in your paper. These include books, long poems, plays, television shows and films, artworks, or musical compositions.

When should I use italics in writing?

Italics are used primarily to denote titles and names of particular works or objects in order to allow that title or name to stand out from the surrounding sentence. Italics may also be used for emphasis in writing, but only rarely.

Can you italicize in text?

Yes, you can format text (Bold, Italic, Underline, Strikethrough ,Colourful font) on Facebook Posts, Comments etc, easily.

How do you italicize a title?

Titles of full works like books or newspapers should be italicized. Titles of short works like poems, articles, short stories, or chapters should be put in quotation marks. Titles of books that form a larger body of work may be put in quotation marks if the name of the book series is italicized.

How do I italicize on my phone?

How do you italicize text on Android? On Android, you can tap and hold the text you’re typing > More > and choose among bold, italic, strikethrough and monospace.

Can I italicize on my iPhone?

While you can’t italicize text when sending messages on an iPhone, you can add italics in Mail, Notes, and Pages. Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

How do you do italics on messenger?

To italicize text, type an underscore (_) before and after the text. Like bold font, italics are often used to draw attention to a certain detail.

Can you change font on messenger?

You can use your device’s built-in accessibility features to make your Messenger appear larger. 1- Go to your device’s settings. 2- Enter your display settings to change the text size. 3- Close and restart the Facebook for Android app to see the changes.

What fonts does Facebook use?

Fonts used by the Facebook Website It uses Helvetica or Arial, or whatever your sans-serif default is. Lucida Grande, Tahoma, and Verdana are also identified by the style sheet.

Does Messenger support markdown?

facebook – FB Messenger supports Markdown | DaniWeb.

How do you color your text on messenger?

- Launch the Messenger app on your phone.

- Now from the home tab, open the conversation you want to pick a color for.

- Tap on the (i) sign at the top right corner.

- Then tap on the theme.

- Finally, pick a color or theme for the conversation.

How do you get text effects on messenger?

How to add fire or confetti effects on Facebook Messenger:

- In the message box, type your message which you want the effect to be added. Do not send it yet.

- Tap on the Sticker button on the right side of the message box.

- Tap effects.

- Choose either the confetti or the fire effect.

What do bold letters mean?

A set of type characters that are darker and heavier than normal. A bold font implies that each character was originally designed with a heavier appearance rather than created on the fly from a normal character.

How do I change my font in Facebook?

- You can change the font of your Facebook posts or messages using the LingoJam text generator.

- To use the LingoJam text generator, simply type your message into the platform’s font generator, select the style of font, and then copy and paste it into your Facebook post or message.

What is best FB name?

So, to complete their wish, we have collected some of the coolest stylish names for Facebook.

- тђє ғїԍђтєя

- Hɘɭɭ’ɓoƴ

- Aɭoŋɘ ɭovɘʀ

- ⓑɩʛʀʌ ⓢʜɘʜʑʌɗʌ

- ⓞƴɘ ⓙʌŋʋ

- ⓛⓞⓥⓔⓡ

- рэяғэст ѕмөкэя

- ⓑɽʌŋⓓəⓓ ⓚʌⓜəəŋʌ

How do you change fonts?

In the Action Launcher Settings menu, tap the “Appearance” option. Scroll down within the “Appearance” menu and then tap “Font.” Choose one of the custom Action Launcher fonts available within the “Font” menu. Tap on one of the options to confirm your choice and then select the back button to return to your app drawer.

What are the 4 major font types?

Most typefaces can be classified into one of four basic groups: those with serifs, those without serifs, scripts and decorative styles.

How do I change my font size?

To increase the text size: Click on the ‘View’ menu with the mouse or pressing ‘Alt’ + ‘V’ . Click on the ‘Text Zoom’ option with the mouse or press ‘Z’. Click on the text size you want with the mouse or use the up and down keys and then ‘Enter’ to select the text size you want.

Why is my text font so big?

Change the Text and Items Size Go to Display Size. Use the slider at the bottom to decrease or increase the text and items size. Slide left to make them smaller and slide right to make them larger.

How do I get my text back to normal size?

Luckily, it’s quite easy to change it back to normal. Here’s how: If the text size is too small, press and hold the Ctrl key and then press the + key (that’s the “plus” key) over on the numeric keypad until the size is back to normal.

How do I make text smaller?

To make your font size smaller or larger:

- Open your device’s Settings app .

- Tap Accessibility Font size.

- Use the slider to choose your font size.

Most word processors can produce italics, which are slanted letters — like

these. If you can’t produce italics, the conventional substitute is to use

underlining — like this. Italics have several uses.

Most commonly, italics are used for emphasis or contrast — that is, to

draw attention to some particular part of a text. Here are some examples:

- The Battle of New Orleans was fought in January 1815, two weeks

after the peace treaty had been signed. - According to the linguist Steven Pinker, «Many prescriptive rules of

grammar are just plain dumb and should be deleted from the

usage handbooks» [emphasis added]. - Standard English usage requires `insensitive’ rather than `unsensitive’.

- Lemmings have, not two, but three kinds of sex chromosome.

The first two examples illustrate emphasis and the last two illustrate contrast.

This is the standard way of representing emphasis or contrast; you should not

try to use quotation marks or other punctuation marks for this purpose.

Another use of italics is to cite titles of

complete works: books, films, journals, musical compositions, and so on:

- We saw a performance of the Messiah on Saturday.

- Chomsky’s book Syntactic Structures revolutionized linguistics.

- Spielberg won his Oscars for Schindler’s List.

An exception: the names of holy books are usually not written in italics. Thus,

we write about the (Holy) Bible and the (Holy) Koran, with no italics. Don’t

ask me why.

Note, however, that we do not use italics when citing a name which is

only a conventional description:

- Dvořák’s ninth symphony is commonly known as the New World

symphony.

Here the label `Dvořák’s ninth symphony’ is not strictly a title, and hence is not

italicized.

A third use of italics is to cite foreign words when talking about them.

Examples:

- The French word pathétique is usually best translated as `moving’, not

as `pathetic’. - The German word Gemütlichkeit is not easy to translate into

English. - The Sicilian tradition of omertà has long protected the Mafia.

- At Basque festivals, a favourite entertainment is the sokamuturra, in

which people run in front of a bull which is restricted by ropes

controlled by handlers.

Related to this is the use of italics when using foreign words and

phrases which are not regarded as completely assimilated into English:

- Psychologists are interested in the phenomenon of déjà vu.

- This analysis is not in accord with the Sprachgefühl of native speakers.

If you are not sure which foreign words and phrases are usually written in

italics, consult a good dictionary.

It is also quite common to use italics

when citing English words that are being talked about, as an alternative to single quotes:

- The origin of the word boy is unknown.

- Note the spelling difference between premier (an adjective meaning

`first’ or `most important’) and premiere (a noun meaning `first

performance’).

Finally, italics are used in certain disciplines for various specific

purposes. Here are two of the commoner ones. In biology, genus and species

names of living creatures are italicized:

- The earliest known member of the genus Homo is H. habilis.

- The cedar waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum) is a familiar American bird.

Note that a genus name always has a capital letter, while a species name never

does.

Second, names of legal cases are italicized:

- The famous case of Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark in

American legal history.

In this case, note that the abbreviation v., which stands for versus (`against’)

stands in roman type, not in italics. Note also that the American abbreviation is

vs.:

- (A) The famous case of Brown vs. Board of Education was a

landmark in American legal history.

Special note: If you have a sentence containing a phrase which would

normally go into italics, and if for some reason the entire sentence needs to be

italicized, the the phrase that would normally be in italics goes into ordinary

roman type instead. So, if for some reason my last example sentence needs to

be italicized, the result looks like this:

- The famous case of Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark in

American legal history.

Copyright © Larry Trask, 1997

Maintained by the Department of Informatics, University of Sussex

Download Article

Download Article

Italics are useful (and sometimes necessary) in many situations when you’re writing. You might use them when you want to emphasize that your friend ate ten burritos, or to write about an interesting article you read in the New York Times. Knowing when and when not to use italics can be confusing, but don’t worry. This wikiHow will walk you through the basics of using italics, show you examples, and help you use italics effectively in your writing.

Italics Usage Cheat Sheet

-

1

Use italics to denote the titles of long creative works. You should italicize the titles of long creative works in your paper. These include books, long poems, plays, television shows and films, artworks, or musical compositions. If you are writing in Chicago or MLA style, you should also italicize these titles on your works cited page or bibliography and use title case (i.e., Capitalizing Each Major Word in a Title). In APA style, italicize but do not use title case. Italicize:[1]

- Book titles: I just can’t stop reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

- Anthology and collection titles: I need the Norton Anthology of English Literature for a class I am taking next fall.

- Long poems: The Bhagavad Gita is a long Hindu poem written in Sanskrit.

- Plays: Sophocles is one of the most famous ancient Greek playwrights. He wrote plays such as Antigone and Oedipus the King.

- Movie and television show titles: We watched Halloween last night, and it terrified us! Fortunately we followed it up with Brooklyn Nine-Nine to lighten the mood.

- Album titles: In Utero is my favorite Nirvana album.

- Long musical works: Mozart’s Don Giovanni is one of my favorite operas. I also really enjoy Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata for piano.

- Works of art: Mexican artist Frida Kahlo painted many self-portraits, including the famous Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird.

- An exception to italics exists for citing titles that incorporate other titles. For example, if you wanted to cite the (made-up) book titled Shakespeare’s King Lear and the Pagan Tradition, you would need to de-italicize the title of the play because it is present in another book’s title.

-

2

Italicize titles of journalistic media. You should italicize the titles of newspapers, journals, magazines, and radio series. News programs with a specific name should also be italicized. As with the literary examples, italicize these titles on your works cited page or bibliography in Chicago or MLA style and use title case. Italicize without title case for APA style.[2]

Italicize:[3]

- Newspapers: My mom subscribes to the New York Times.

- Journals and magazines: I read articles from the New England Journal of Medicine for school, but when I’m reading for fun I prefer People.

- Radio series and podcasts: I listen to This American Life whenever I get the chance. Like nearly everyone else in 2014, I was also hooked on the podcast Serial.

- News programs: The Rachel Maddow Show is one of the top-performing news programs on cable news networks.

Advertisement

-

3

Italicize specific editions of sacred texts, but not the generic names of sacred texts. You should italicize the titles of specific editions of sacred texts, such as the The New American Standard Bible. However, you should not write the names of holy books, such as the Bible, in italics. This rule applies whether you are including the title within your paper or on your works cited page or bibliography.[4]

-

4

Don’t italicize the names of public documents. Names of documents like the Declaration of Independence or the Magna Carta are not italicized.[5]

- However, some academic styles such as the American Sociological Association (ASA) recommend that you italicize the titles of specific public documents, but not well-known documents (e.g., the Constitution). For example: Telecommunications Act of 1996, Public Law 104-014, 110 U.S. Statutes at Large 56 (1996).[6]

- However, some academic styles such as the American Sociological Association (ASA) recommend that you italicize the titles of specific public documents, but not well-known documents (e.g., the Constitution). For example: Telecommunications Act of 1996, Public Law 104-014, 110 U.S. Statutes at Large 56 (1996).[6]

-

5

Don’t italicize or capitalize the word “the” at the beginning of titles. Even if “the” is part of the official name, such as “The Wall Street Journal,” most style guides recommend that you do not capitalize or italicize “the” when it comes at the beginning of a title.[7]

- Obviously, if you use the title as the beginning of your own title or a sentence, you would capitalize the word “the.” You would not italicize it, however. For example: The Wall Street Journal is the premier source of business and financial news in the US.[8]

- Obviously, if you use the title as the beginning of your own title or a sentence, you would capitalize the word “the.” You would not italicize it, however. For example: The Wall Street Journal is the premier source of business and financial news in the US.[8]

-

6

Use italics for foreign words that have not been integrated into the English language. Words like alumni do not need to be italicized, but words like semper fi do need to be italicized. The difference is that alumni is understood by English speaking people as graduates of a particular university, whereas semper fi requires translation to be understood.[9]

- This rule, like several others, is open to interpretation. A general rule of thumb is that if the foreign word is in an English dictionary, you do not need to italicize it.[10]

- This rule, like several others, is open to interpretation. A general rule of thumb is that if the foreign word is in an English dictionary, you do not need to italicize it.[10]

-

7

Italicize names of vehicles. You should italicize the names of ships, airplanes, missiles, and man-made satellites. Do not italicize modifiers on the name such as “the” or “U.S.S.” or “H.M.S.”.[11]

- The Enola Gay

- U.S.S. Cole

- Don’t italicize types of vehicles, such as the Learjet.

-

8

Use italics to denote legal cases. When you need to provide the name of a legal case in a paper, italicize the case title including v.. You should also italicize the legal case name on your works cited page or bibliography.[12]

- The famous case of Gideon v. Wainwright was a landmark in American legal history.

-

9

Use italics to denote species names, variety, and subspecies names. The Latin names of species, varieties, and subspecies need to be italicized, but common English names do not need to be italicized. For example:[13]

- For example: Homo sapiens is the binomial nomenclature for the human species. Homo is the Latin genus name, and Homo sapiens is our species name.

- In scientific writing, it is customary to give the full binomial nomenclature in the title and the first time it is used in the paper. After that, abbreviate like so: H. sapiens.

- You would not italicize “humans,” the common English name for H. sapiens.

-

10

Know the exceptions. While most style guides recommend using italics as shown in the above examples, some don’t. The AP (Associated Press) style does not use italics in news stories at all, even to refer to titles.[14]

- In APA style, if you are not sure whether something should be italicized, the preference is to not italicize it.[15]

- Many writers for the web prefer to use underlining or quotation marks to highlight text. This is because italics can be difficult to distinguish on a computer screen. Use your judgment to determine whether italics or other forms of highlighting are appropriate for your purpose.[16]

- In APA style, if you are not sure whether something should be italicized, the preference is to not italicize it.[15]

Advertisement

-

1

Use Italics when you want to emphasize a certain word or phrase. A common use for italics is to draw attention to a particular part of a text in order to provide emphasis. If something is important or shocking, you might want to italicize that word or phrase so that your readers don’t miss it. For example:[17]

- He had managed to eat ten cookies.

- I love the word flabbergasted.

-

2

Italicize words, letters, and numbers when used as specific terms. If you want to call attention to a word, letter, or number as a specific term, use italics. For example:[18]

- When defining an unfamiliar term, you may want to italicize its first appearance: “The scientific term for sneezing is sternutation.”[19]

- Use italics to emphasize a letter on its own: I got an A in history this term.

- When he moved to the Denver Broncos, quarterback Peyton Manning retained his famous 18 on his jersey.

- When defining an unfamiliar term, you may want to italicize its first appearance: “The scientific term for sneezing is sternutation.”[19]

-

3

Use italics when you want to show a contrast between two words or phrases. It is also common to use italics to show contrast to your readers. If you want your readers to notice a contrast between two words or phrases, you might want to italicize that word or phrase so that your readers don’t miss it. You can italicize one or both words depending on your objective.[20]

- He had managed to eat not nine, but ten cookies.

- The words through and threw may sound the same but obviously have very different meanings.

-

4

Avoid using italics to provide emphasis or show contrast in formal writing. Using italics to provide emphasis or show contrast is usually accepted in informal writing. However, most style guidelines advise against these uses in formal, professional, or academic writing. In most cases, it’s preferable to use syntax to emphasize your point in these types of writing.

- For example, APA style specifies that using italics to provide emphasis is inappropriate unless the reader might miss your intended meaning without the italics.

- Chicago style also does not recommend the use of italics for emphasis.[21]

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

I am writing a book and one of the main characters has thoughts here and there. Would I those be italicized?

It’s not required. Doing so would be a matter of stylistic choice.

-

Question

In fiction, when I’m writing a thought in italics, and that thought includes a word that would normally be in italics, such as a TV show or book title, then the book title or TV show is de-italicized?

Yes.

-

Question

Should Roman words be italicized?

Roman (Latin) words are sometimes italicized to differentiate them from English, but it’s not required.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

Consistency is important when using italics. If you italicize a title on one page, make sure that you do so throughout your paper. Don’t switch from italics to underlining halfway through.

-

If you are required to use a specific style for a course or your profession, always refer to the style guide for specific details on the rules for italics.

-

Don’t italicize names of organizations, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Use title case instead.

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX