Word knowledge plays an important role in language teaching, it provides the basis for learners to grasp four language skills listening, speaking, reading and writing. Without a certain amount of words, learners cannot expect to understand fully the content of listening and reading and express their meaning clearly in the process of speaking and writing. Lexical competence is one of components of communicative competence (Meara 1996).however, knowing a word is complicated and it involves knowing its form, meaning and use (Nation,2001) .e.g. spelling, pronunciation, grammar, denotative and connotative meaning, word associations, frequency, collocation and register.

For English Learners in China, due to limited exposure to the target language, they have got difficulties with collocations and collocation errors are often found in their writing and speaking. In order to achieve a high level of competence in English, it is better for students to know more collocations. Nowadays in China, collocation has become one of the most important issues in English language teaching and learning.

In this paper, firstly, the author attempts to explain and exemplify the question of ‘what is involved in knowing a word’, and some aspects of word knowledge are discussed. Secondly, collocation as one aspect of word knowledge is chosen to discuss in more detail, then some issues with respect to collocation are discussed, including the definition of collocation, the classification of collocations and the significant of collocation,. Finally, it deals with the classroom practice, as an English language teacher, some suggestions are given on the teaching of collocation in the classroom.

What is involved in knowing a word?

In the L1 acquisition, it is very common that learners may know how to speak one word in mother tongue but they do not know how to spell this word, while in L2 acquisition, learners may know the written form of word, but they do not know how to pronounce it clearly, or learners may know one meaning of a word, however, they do not know other meanings of this word in different contexts. Even learners may know both form and meaning of a word, but they do not know how to use this word appropriately in different contexts. Therefore, knowing a word is quite a complex cognitive process, and knowing a word involves understanding many aspects of word knowledge. Nation (2001:23) points out that ‘words are not isolated units of language’. Therefore, the question of ‘what is involved in ‘knowing a word’ has attracted considerable attention in the field of vocabulary acquisition. Researchers have identified different types of word knowledge. Richards (1976) and Nation (1990, 2001) list different aspects of word knowledge which learners needs to know about a word. I will use Nation’s classification of word knowledge as the basis for my discussion. More information, see the appendix 2.

In recent decades, Nation is one of the world’s leading authorities on vocabulary acquisition. Based on the earlier word framework (Nation, 1990), Nation (2001:27) points out that knowing a word involves knowing its form, meaning and use, and each category is broken down into receptive and productive knowledge. Each of these three categories can be found in the discussion brief below. More details please see appendix two.

Word form

Knowing one word form includes spoken form, written form and word parts (Nation, 2001). Spoke and written form are essential word knowledge which helps learners to move forward to literacy. The knowledge of phonics, word reorganization and spelling provides a basis for learners to decode word meaning and use the word appropriately in different context. Knowing the spoken form means being able to understand the spoken form in hearing this word, this is receptive knowledge, as well as being able to pronounce the word clearly and make other people understood in the conversation, this is productive knowledge. Knowing the written form means being able to recognize the written form when reading, this is receptive knowledge; in the meantime, knowing the written form means being able to spell correctly the written form in writing, this is productive knowledge (Schmitt, 2000).Schmitt points out that the more similar between the second language and first language in spelling and pronunciation, the easier learners to attain these knowledge in second language. For example, it is easier for Spanish to learn the spoken and written form of English than to learn Chinese and Japanese, due to different orthographic and pronunciation systems (ibid).

In terms of word parts, it involves knowing the prefix, suffix and stem that make up a word as well as knowing the word family (Nation 2001). It is possible to decode the meaning of unknown word when knowing the prefix, suffix or stem of this word. Take the word unbelievable, for an example. Prefix un means not, opposite, believe means trust something, -able means can be, worthy of, therefore the meaning of unbelievable is ‘Not to be believed’. In addition, Nation (2001) point out that knowing a word involves knowing the members of word family that will increase as proficiency develops. For example, knowing the word able, learners may know unable, disable, in the beginning, then they will know enable, ability, abilities, disabled disability.

Normally, the knowledge of phonics, word reorganization and spelling are learnt by explicit instruction, such as repeat exercises, drills and rote memorization. Although this explicit instruction helps learners to acquire this knowledge to some extent, however, too much depending on exercises and rote memorization leads to boredom and decrease motivation. The best way to develop the phonics, word reorganization and spelling skill is to provide more opportunities to engage in meaningful reading and writing in the particular context. In addition, Learners can be trained and encouraged to use learning strategies. Such as’ finding analogies, cover and recall, focusing on difficult parts and setting regular learning goals’ (Nation: 2001:46).

2.2 Word meaning:

Nation (2001) points out that knowing the meaning of a word includes connecting form and meaning, concept and referents, and word associations. Normally the word form and meaning are learned together. it means that when learners hear and see the word form, the meaning of this word will retrieved, in the meantime, when they want to express the meaning of word, the form of this word will retrieved as well. Daulton (1998) points out that the same form in the target language and first language makes learning the word meanings burden light. For example, English has some loan words from Japan; this helps Japanese learn some English words easier. In terms of concepts and referents, each word has got a core concept, while other meanings vary. It means a word has got a lot of meanings depending on the different contexts. Aitcheson (1987) also points out that there is a fuzzy boundary in the meanings of a word. One of the main reasons is that schema is different in the different contexts (Schmitt, 2000). In addition, Richards (1976:81) claims that ‘words do not exist in isolation’ .Knowing a word involves knowing word association. Word associations are the links that words are related to each other in people’s mind. One word is given to a learner; some other that are similar or opposite, and related words easily come to mind.

e.g. Accident-car, blood, hospital.

School- chair, table, classroom, students, teachers;

Home- kitchen, dish, food.

2.3 Word use

Nation (2001) points out that knowing how to use a word involves knowing the word grammatical functions, collocations and being aware of constraints on use due to many factors, such as register, frequency and different cultures. Grammatical function is one of the most important linguistic constraints in choosing a word to use, and grammatical function refers to word classes and what grammatical patterns one word can fit into (ibid).e.g. we can say ‘I know a lot, I eat a lot, I read a lot’, however we cannot say ‘I knowledge a lot, I eaten a lot, I reading a lot’.

Register and frequency are other particular types of word constrains on use. Register is considered as the stylistic constraints that ‘make each word more or less appropriate for certain language situations or language purposes’ (Schmitt, 2000:31).

In terms of word frequency, High frequency words (laugh) are heard and seen and used more frequently than low frequency words (guffaw, giggle, and chuckle). Generally speaking, low frequency words are used in the particular discipline, e.g. medicine, law, engineering, literature and so on). Therefore, High frequency words are more easily recognized and recalled than low frequency words. Therefore, knowing the use of a word should be aware of constrains on use of a word.

In this section, word form, word meaning and word use are discussed. Next I will select collocation as one type of word knowledge (collocation) to discuss in more detail.Firstly, I will explore the definition of collocation, the types of collocation, and then I suggest that the knowledge of collocations is essential for learners, lastly, some advice on teaching and learning collocations in the classroom are given.

The definition and clarification of collocation

Collocation is defined in different way by researchers. collocation refers to’ items whose meaning is not obvious from their parts ‘(Palm 1933 in Firth 1957, summarised in Nation, 2001:317).e.g., blonde hair, shrug his shoulders, fizzy drink, bite the dust. According to Schmitt(2000:76),collocation is described as ‘the tendency of two or more words to co-occur in discourse’. Here co-occurrence is the main characteristic of collocation. Similar to Schmitt, Lewis (2000:132) describes it in another way as ‘collocation is the way in which words co-occur in natural text in statistically significant ways’, in this definition, the way words naturally co-occur is emphasized. It implies that people cannot put two or more words together arbitrarily, because words co-occur naturally. In fact, it is very common that some learners in foreign and second language context tend to put two or more words together arbitrarily because of the first language interference. For example, do a decision instead of make a decision, big rain instead of heavy rain. Nation (2001:371) defines collocation as’any generally accepted grouping of words into phrases or clauses’. This definition reflects the two criteria of collocation which are ‘frequency occur together and have some degree of semantic unpredictability’ (ibid). The above definitions indicate that words co-occur naturally, it is not easy for learners to get the meaning of collocation form its components, and as a result, it may cause problems for learners to acquire the knowledge of collocations. The definition of collocation leads to the shift to explore the types of collocation.

Collocations are divided into two basic types: grammatical/syntactic collocations and Semantic/lexical collocations (Schmitt.2000). The former refers to one word combines with other words with the grammatical rule. E.g. get used to, be good at .the latter means multi words co-occur to contribute the meaning. E.g. make a mistake, catch a bus. Lewis (2000) lists different types of collocation, such as verb+noun, noun+noun, adjective + noun, verb+adjective, fixed phrase, part of proverb, binomial, trinomial and so on.

The significance of learning collocations

4.1 The underlying rule of organization of lexicon

Sinclair (1991) advances two principles (the open-choice principle and the idiom principle) to explain the organization of the texts. The open-choice principle suggests that you can put any word in the slot to make texts as long as you follow the grammar rule. It is known as slot-and-filler model. However, this principle cannot explain the collocation constrains. The idiom principle highlights that there are some regularities when two or more words combine together, and Sinclair claims that there are some constrains on the choices words in discourse(ibid), in other words, the way words co-occur are not random. Hill (2000) also agrees with the idea that the lexicon is not arbitrary. E.g. commit. A relatively fixed set of words can co-occur with it. E.g. suicide, crime, murder, sin. But not promise, advice, plan.

4.2 The size of collocation

Groups of words or phrases are used very frequently to express meaning in the oral and written texts. Hill (2000) claims that two or more than two words collocations make up a huge percentage in the text. It is estimated that up to 70% of everything we use in oral and written texts are fixed expression. This widely used collocation implies that if non-native learners have got a huge amount of collocation, it will be helpful for them to achieve native-like fluency in the target language. Nation (2001) also points out that knowing the collocation knowledge of a word is one of the most important aspects of knowing a word.

4.3 Native-like fluency

Learning collocation helps learners to speak and write English in a more natural and accurate way (Dell and McCarthy, 2008).if learners store a huge number of collocations, this allows them to retrieve ready-made language, think more quickly and produce language efficiently (Hill 2000).in addition, they do not need to make sentences word by word to express themselves, and this assists them in using English not only naturally but accurately. According to my experience of teaching English in China, due to the first language interference, the direct translate are used to produce language, the inaccurate use of collocation is very common in the essay writing, and this is one of the main causes which lead to the emergence of Chinglish, e.g. eat medicine, make exercise, receive the telephone e, open/close the radio, look TV instead of take medicine, do exercise, answer the telephone, turn on/turn off radio, watch TV.

4.4 language acquisition

Learning collocation enhances language acquisition (Hill, 2000). Nation (2001) points out that collocation helps learners to store knowledge quickly. If learners have got a huge number of collocations in mind, it is easier for them to retrieve ready-made language from their mental lexicon and think more quickly because they can recognize big chunks of language when reading and listening, and this is very helpful for them to understand the meaning in the speed of speech and the long reading texts. In contrast, if learners decode the meaning of speech and texts word by word, maybe they know the meaning of each word, however, they do not know the meaning of collocation or chunks in the long discourse. It may be difficult for them to get the accurate meaning of the speech and texts. Based on my teaching experiences as a high school English teacher, I found that most of the students in my class have got difficulty understanding the meaning of the entire paragraph due to lack of collocation competence. Hill (2000) also agree with this explanation that one of the main reason for having difficulty in reading or listening is due to lack of collocation competence, rather than the load of new words.

E.g. as far as I know, the old sheep comes up with the idea that he will give up on his dream to look after little sheep, however, he cannot make this decision due to other people. This makes him keep crying all the time.

Even though students know the meaning of each word in the above paragraph, it is still very hard for them to understand the entire paragraph because they are not familiar with some collocations inside.

In the above two sections, the definition, types of collocation and the significance of collocation were discussed. In the next section, I would like to give some suggestions on teaching and learning collocations in the classroom.

5. Teaching collocations in the classroom

Here are some suggestions and activities for English language teachers that will help students to acquire the knowledge of collocations in the classroom.

5.1 Raising awareness of collocation in classroom

Woolard (2000) points out that raising learners’ awareness of the importance of collocations is a good way to help them notice them. Teachers should explain the rationale for collocation, the significance of learning collocation in language acquisition, and then make learners know that words are not used in isolation, knowing one word also means knowing which word is likely to co-occur with it, Teachers can emphasize in the classroom instruction that knowing collocations not only helps them to receive (reading and listening) and store language quickly but also produce language naturally and accurately. E.g. When teaching reading, it is an effective way to ask learners to identify collocations in the texts and let them make a list of collocations. When teaching speaking, teachers can ask learners to predict the collocations of the word. If teachers encourage learners to notice collocations in input and output teaching activities, this practice will help learners develop an ability to notice and use collocations. It also helps learners to develop learner autonomy, when they read newspaper, listen to radio, watch TV and talk to other people in English. They will notice the existence of collocations in spoken and written texts.

5.2 Increasing language input and providing output opportunities

Using the authentic reading texts is an effective way to teach collocations. In the classroom, Lewis (2000) also suggests that teachers should choose the right kind of texts which includes different types of collocations. These texts can be used in the intensive reading practice. However, this is not enough to acquire the knowledge of collocations. Krashen(1985 )points out that enough comprehensible input is a source of language acquisition. Collocations are used in different types of texts, such as newspaper, magazine, and story books. It is good for learners to do extensive reading to encounter collocations in these authentic texts and remember them in the notebooks. In addition, extensive reading provides learners with context to make the understanding of the meaning of collocation easier and deeper, therefore. Extensive reading not only helps them to know how native speakers use the collocations in the natural way, but also moves learning collocations from short to long-term memory.

However, Swain (1995) claims that despite the fact that learners are given a rich source of comprehensible input in the French immersion programmes in Canada. It is still hard for learners to produce the native-like language proficiency. Teaching collocations also needs to provide opportunities to learners to practice how to use collocations. These activities can be some communicative activities in terms of writing and speaking. Hill, Lewis and Lewis (2000) suggest that teachers can ask learners to find the collocations in the reading texts, and then use these collocations to reconstruct the content. Some collocation errors can be found. Teachers need to write down these errors in the blackboard and make learners to analyse them. The same activities can be done by listening to tapes or stories and then ask learners to speak out the collocations. Some exercises are used to help learners acquire collocations (Dell and McCarthy, 2008). Such as Fill in blanks, Match games True/False.

5.3 Using resources: Collocation Dictionaries and corpora and concordances

It is a good way to get learners use collocation dictionaries to know more about collocations. e.g. Oxford Collocations Dictionary for students of English. In addition, with the development of internet, the innovative corpora and concordances are becoming the effective way for learners to check collocations online. They provide great texts to check collocations and grow dramatically with the update texts. Corpus has brought great insights into linguistics, especially into the study of collocations.

A corpus collects the written or spoken texts and stores them in the computer. It is very helpful and efficient way to use the corpus to check how the people use collocations in written or spoken texts .Sinclair (1991:32) defines ‘a concordance is a collection of the occurrences of a word-form, each in its own textual environment’. Compared to collocation dictionary, concordance allows us view more collocation lists in the corpus. However, I think it is necessary for teachers to provide learners with some training to help them use it well, this also encourage learner autonomy.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have explained and exemplified the question ‘what is involved knowing a word’. Word form, word meaning and word use were discussed briefly. Such as spelling, pronunciation, word parts, word meanings, word associations, grammatical functions, register, collocations, frequency and so on. In these many aspects of word knowledge, collocation as one type of word knowledge was chosen to explore. First, the definition and classification of collocation were discussed, and then the reason for choosing collocations was explained. Next, this author proceeded to explore how to teach collocations in the classroom. Lastly, this paper offers some suggestions on how to help learners acquire the knowledge of collocations in the classroom.

Appendix 1:

The meaning of knowing a word(Richards,1976),

1

The native speaker of a language continues to expand his vocabulary in adulthood, whereas there is comparatively little development of syntax in adult life.

2

Knowing a word means knowing the degree of probability of encountering that word in speech or print. For many words we also “know” the sort of words most likely to be found associated with the word

3

Knowing a word implies knowing the limitations imposed on the use of the word according to variations of function and situation.

4

Knowing a word means knowing the syntactic behavior associated with that word.

5

Knowing a word entails knowledge of the underlying form of a word and the derivations that can be made from it.

6

Knowing a word entails knowledge of the network of associations between that word and other words in language.

7

Knowing a word means knowing the semantic value of a word.

8

Knowing a word means knowing many of the different meanings associated with the word.

Appendix 2:

What is involved in knowing a word? (Nation, 2001)

Form

spoken

R

P

What does the word sound like?

How is the word pronounced?

written

R

P

What does the word look like?

How is the word written and spelled?

word parts

R

P

What parts are recognizable in this word?

What word parts are needed to express the meaning?

Meaning

Form and meaning

R

P

What meaning does this word form signal?

What word form can be used to express this meaning?

Concept and referents

R

P

What is included in the concept?

What items can the concept refer to?

associations

R

P

What other words does this make us think of?

What other words could we use instead of this one?

Use

grammatical functions

R

P

In what patterns does the word occur?

In what patterns must we use this word?

collocations

R

P

What words or types of words occur with this one?

What words or types of words must we use with this one?

constraints on use (register, frequency )

R

P

Where, when, and how often would we expect to meet this word?

Where, when, and how often can we use this word?

Order Now

What is involved in knowing a word? Is it significant for learners of a second language to manage a great amount of vocabulary? How can teachers help vocabulary learning?

In this essay, I am firstly going to analyse, what really a word is, and the aspects involved when knowing and using vocabulary. In the second section of this paper, I am going to discuss and analysed some authors and linguists’ point of view about lexicon and its importance in learning a foreign language.

Finally, I am going to focus on some useful learning strategies to be applied when teaching vocabulary to second language learners.

When thinking about teaching and learning of a second language, the first aspect which comes to our minds is the syntactic aspect, the rules by which we construct intelligible ideas.

To know how to use grammatical rules is, indeed, important to native and non natives speakers, it could make the difference between a good and a bad user of the language.

Nevertheless, as important as knowing about grammar is knowing about vocabulary.

During decades, lexis was kept aside and was not considered as an important aspect of language to be concerned about. «Linguists have had remarkable little to say about vocabulary and one can find very few studies which could be of any practical interest for language teachers» (Wilkins, 1972:109). Though, after ignoring it for a long time, Lexical knowledge is now been appreciated as one of the most important aspect in the learning process. (Gass and Selinker, 1994:270).

According to Nation (2001:26) meaning is just an aspect of knowing a word. Identifying its Form (whether it is spoken, written as well as word-parts) recognising its use (grammatical functions, collocations or constraints on use) are strands involved too.

As stated before, words embrace much more than a meaning and to be familiar with them, a learner must be aware of its formation and its meaningful parts. For that reason , I am going to focus this essay on Morphology, which is defined by R.L. Trask (1997:145) as «the branch of linguistics dealing with the study of word structure, conventionally divided into inflectional and derivational morphology».

From now, the term «word-form» is also going to be used in this essay to refer to a word.

The first assumption a learner should make is that a word-form consists of meaningful pieces of language ( Ronald Carter et Michael McCarthy, 1988:18) called morphemes, which is commonly defined as the smallest grammatical and meaningful unit.(Aitchison, 1994:122) In the word-form useless two morphemes with different meanings ( use/less) are arranged to create another word-form with a new meaning. In this case, the morpheme use is a free morpheme, due to it can stand by itself, whereas the affix less is a bound morpheme, since despite having own meaning it is not freestanding.

The same phenomenon occurs in unhappy. No one may consider un as a word, but its meaning is well- known (opposite in this case), instead of happy that is a lexeme by itself.

In the English Language as in many others, the affix found in one word-form, may also occur in others.

That feature, Nation claims, is another aspect involved in knowing a word, (2001:46) and this semantic knowledge, may facilitate student’s acquisition of vocabulary, especially in the first stages of learning word-forms, thus learners may apply word-formation to decode the meaning of other words.

The same learner who realized that unhappy could be considered as opposite of happy, due to the affix un, will interpret the word uneducated correctly thanks to that learner already recognises one of the meanings of the specific bound morpheme un.

There is no doubt that being aware of word-formation contributes in the learning process of a non native speaker. Although, it should be mentioned, that morphemes not always behave as in the examples above. As not all words consists of two or more morphemes, some words may create misunderstandings in a learner. Whether the affix un enables to create an opposite meaning, a beginner student who is trying to formulate a sentence in English with the language he or she handles, may easily say » I unwork on weekends» assuming that unwork is the opposite of work, which is actually erroneous.

Owing to that fact , in the last section of this paper I am going to concentrate in the ways teachers can help learners to achieve accuracy in learning vocabulary.

Another significant morphological feature in word-forms, is the grammatical factor. Bolinger and Sears mention that by the point of view of grammar, morphemes may be grouped into inflectional or derivational ones( 1981:71). The former group is related to those morphemes which affect the syntactic role of a word-form, without modifying its inner meaning. Aitchison illustrates Inflectional by saying that the only difference between the words Dish and Dishes is the suffix plural ending -es (1994:124). The author agrees with Bolinger and Sears in that when inflectional morphemes are attached to a word, it continues being the same, but with a different form(1981:66).

The latter group, derivational morphemes, are the bits of language that attached to an existing word make a new word. Aitchison exemplifies it using the word-form Learn. When the suffix -er is attached, a new word appears: learner. In this case, the observable change may be in word class or in Sense.(1994:124)

The diagram below illustrates the difference between both Derivation and Inflection.

DERIVATION

INFLECTION

PREFIX

SUFFIX

SUFFIX

Dis- agree -ment

Hate -s

Until now, it is been explained the morphological aspect of knowing a word. It was also said that being familiar with this feature is useful when learning a foreign language, but the fact that vocabulary learning and teaching was a neglected theme for so many years, placed the task of vocabulary acquisition on learners’ hands (Hedge, 2000:110). I concur with McCarthy in saying that «Studying how words are formed offers one way of classifying vocabulary, for teaching and learning purposes…»(1990:5).

As a non-native speaker, I truly believe that vocabulary development is essential to communicate in a foreign language, and I do not hesitate in declaring that Morphology is one of the most important tool learners may have command of when acquiring a new language, and English Teachers may contribute in achieving this task, by using vocabulary learning strategies in the classroom.

As a language is made up of an endless amount of words, it may be slightly demanding for teachers and learners to select the appropriate number and words to be acquired. Nonetheless, coping with learning strategies is a conscious process which enables people to control their own learning at their own speed and may be employed in any subject, not just in teaching a foreign language.

Learning strategies promote learner autonomy in the learning process, whereas, these techniques must be taught and trained. At this point, is when teachers emerge to become a facilitator in the learners acquisition of the proper knowledge.

Tricia Hedge classifies learners strategies into four groups: Cognitive, Metacognitive, Socio-affective and Communication strategies (2000:77-79).

The author gives some examples to be applied within each category.

TYPES OF LEARNER STRATEGIES

Socio-affective strategies

Communication strategies

Metacognitive strategies

Cognitive strategies

*Initiate conversations.

* Collaborating on tasks.

*Listening to the radio in the target language.

*Watching TV in the target language.

*Use of body language.

*Paraphrase.

*Use of cognates.

*Self-monitoring.

*Evaluation of the learning process.

*Analogy: to compare the meaning of a new Word in L1 and L2.

*Memorization: Visual or auditory

*Repetition: imitating a model.

*Inferencing: guessing meanings.

Focusing on acquiring vocabulary by learning word-formation, a teacher may wish to make use of affixes in first place. «Recognizing the composition of words is important; the learner can go a long way towards deciphering new words if he or she can see familiar morphemes within them» (Michael McCarthy, 1990:4).

Nation states (2001:275) that learners should attain some essential skills in order to acquire the appropriate knowledge; these are the Receptive and Productive skills.

The former refers to the ability of recognizing that some words are made up of meaningful bits of language, the ability of knowing the meaning those bits of language. Nation grades derivational affixes according from the easiest to the more difficult to learn. (Nation 2001: 268) and the ability of recognizing that a new word has been made.

e.g. use / useful

The latter skill refers to the ability of realising the shifts in pronunciation and spelling of the new word-form; the ability of identifying the changes in class of the new word-form.

To teach vocabulary throughout affixes may result in an attractive experience for learners, but first, it is imperative to create an appropriate environment to develop the activities. The purpose of the tasks must be clear enough(what it is going to be learnt and why) as well as the instructions for the class work. Equally important is the fact that learners may know that the new knowledge is pertinent and relevant for their learning process.

As brainstorming learners may well start analyzing some authentic material from a magazine, where they underline all the suffixes or prefixes. In comparing with the whole class, learners will acknowledge and discuss the overlap among some words regarding, for example, the endings, and in which way they affect the word-forms. It is appropriate displaying tasks which enable learners to recognize those shifts clearly.

The PPP (Presentation, Practice, and Production) approach seems suitable when working with affixes. First, the teacher presents one affix, emphasizing its meaning and its use. Then, students identify that affix in the words by underlining them, for instance; and finally learners are encourage to apply the new knowledge, by matching words with the appropriate affix and using the new word in a new sentence.

Still, educators must be careful. Exposing the learners to too many morphemes at the same time, may cause confusion and rejection amongst students, therefore, it is important to consider frequency when choosing the proper morphemes to teach, that motivates learners since they will feel familiar with the content. (Nation 2001:268)

Another way to deal with affixes is using the dictionary as a tool. Learner could be asked to look up as many words containing the prefix -anti (maybe any other), before giving its meaning (against), so they will guess it and share their predictions with the rest of the class.

The following list contains suggestions about how to work with morphemes in the classroom:

— Matching columns. Column A containing the affix, and column B the root.

— Playing memory cards with roots and affixes.

— Giving extra points to the learners when they use affixes properly.

— Team contest, where the team with more correct words having affixes and roots, will obtain extra points.

— Using Hangman game with words including morphemes to strengthen spelling.

Reinforcement may be fulfilled by creating a chart for the classroom with roots, suffixes and prefixes with their meanings, that students will make use of when requiring.

Every teacher wonders how to teach a word to students, so that it stays with them and they can actually use it in the context in an appropriate form. Have your students ever struggled with knowing what part of the speech the word is (knowing nothing about terminologies and word relations) and thus using it in the wrong way? What if we start to teach learners of foriegn languages the basic relations between words instead of torturing them to memorize just the usage of the word in specific contexts?

Let’s firstly try to recall what semantic relations between words are. Semantic relations are the associations that exist between the meanings of words (semantic relationships at word level), between the meanings of phrases, or between the meanings of sentences (semantic relationships at phrase or sentence level). Let’s look at each of them separately.

Word Level

At word level we differentiate between semantic relations:

- Synonyms — words that have the same (or nearly the same) meaning and belong to the same part of speech, but are spelled differently. E.g. big-large, small-tiny, to begin — to start, etc. Of course, here we need to mention that no 2 words can have the exact same meaning. There are differences in shades of meaning, exaggerated, diminutive nature, etc.

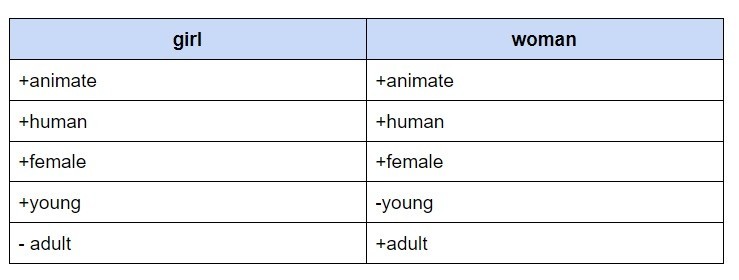

- Antonyms — semantic relationship that exists between two (or more) words that have opposite meanings. These words belong to the same grammatical category (both are nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). They share almost all their semantic features except one. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1998) E.g.

- Homonyms — the relationship that exists between two (or more) words which belong to the same grammatical category, have the same spelling, may or may not have the same pronunciation, but have different meanings and origins. E.g. to lie (= to rest) and to lie (= not to tell the truth); When used in a context, they can be misunderstood especially if the person knows only one meaning of the word.

Other semantic relations include hyponymy, polysemy and metonymy which you might want to look into when teaching/learning English as a foreign language.

At Phrase and Sentence Level

Here we are talking about paraphrases, collocations, ambiguity, etc.

- Paraphrase — the expression of the meaning of a word, phrase or sentence using other words, phrases or sentences which have (almost) the same meaning. Here we need to differentiate between lexical and structural paraphrase. E.g.

Lexical — I am tired = I am exhausted.

Structural — He gave the book to me = He gave me the book.

- Ambiguity — functionality of having two or more distinct meanings or interpretations. You can read more about its types here.

- Collocations — combinations of two or more words that often occur together in speech and writing. Among the possible combinations are verbs + nouns, adjectives + nouns, adverbs + adjectives, etc. Idiomatic phrases can also sometimes be considered as collocations. E.g. ‘bear with me’, ‘round and about’, ‘salt and pepper’, etc.

So, what does it mean to know a word?

Knowing a word means knowing all of its semantic relations and usages.

Why is it useful?

It helps to understand the flow of the language, its possibilities, occurrences, etc.better.

Should it be taught to EFL learners?

Maybe not in that many details and terminology, but definitely yes if you want your learners to study the language in depth, not just superficially.

How should it be taught?

Not as a separate phenomenon, but together with introducing a new word/phrase, so that students have a chance to create associations and base their understanding on real examples. You can give semantic relations and usages, ask students to look up in the dictionary, brainstorm ideas in pairs and so on.

Let us know what you do to help your students learn the semantic relations between the words and whether it helps.

To learn new vocabulary, these factors must be considered in order to effectively introduce the new words to students:

- Form:

- Spoken: Transcription of the word is necessary.

- What does the word sound like?

- How is the word pronounced?

- Written: Written form of the word is needed.

- What does the word look like?

- How is the word written and spelled?

- Word part: Include affixes of the word if possible.

- What parts are recognizable in this word?

- What word parts are needed to express this meaning?

- Spoken: Transcription of the word is necessary.

- Meaning:

- Form & meaning

- What meaning does this word form signal?

- What word form can be used to express this meaning?

- Concept & referents

- What is included in the concept?

- What items can the concept refer to?

- Associations: Synonyms & antonyms (if possible).

- What other words does this make us think of?

- What other words can we use instead of this one?

- Form & meaning

- Use:

- Grammatical functions

- In what patterns does this word occur?

- In what patterns must we use this word?

- Collocations

- What words or types of words occur with this one?

- What words or types of words must we use with this one?

- Constraints on use (register, frequency…)

- Where, when and how often would we expect to meet this word?

- Where, when and how often can we use this word?

- Grammatical functions

There’s relatively little on the Notebook about teaching vocabulary, and in the next few weeks I’m going to try and remedy that. In future articles we’ll talk about techniques you can use in the classroom to introduce, practice and recycle new lexis, but before looking at that, we need to know exactly what it is we want to teach. So what does it mean to know a word? Here are a few suggestions.

«Knowing» a word means :

a) understanding its basic meaning (denotation) and also any evaluative or associated meaning it has (connotation). For example cottage and hovel are both types of small houses. But cottage suggests cosiness, a pretty house with a garden, probably in the countryside, whereas hovel suggests a run-down construction, dirt and squalid poverty. Many words have similar positive or negative connotations — consider slim and scrawny — and, in certain cases these connotations may lead to their being considered «politically incorrect» — for example handicapped.

b) understanding the grammatical form of the word and its syntactic use (colligation). For example, interesting, main and alone are all adjectives. However, while interesting (like most adjectives) can be either attributive or predicative — eg:

- It was an interesting discussion (attributive)

- The discussion was interesting (predicative)

main can only be used attributively — That’s the main point rather than *That point is main, while alone can only be used predicatively — The woman was alone but not *We saw an alone woman.

c) understanding that words may have more than one meaning — eg boom may mean a loud sound, an increase in business, a pole to which a sail (on a boat) or a microphone or camera (in a TV or film studio) may be attached, or a heavy chain stretched across a river to stop things passing. Changes in meaning may also involve changes in colligation. To go back to the example of adjectives above, take the adjective old. With the meaning of aged it can be both attributive or predicative — We live in an old house / Our house is old. But with the meaning known for a long time it is only attributive — an old friend, an old saying. Using it predicatively —My friend is old — changes the meaning back to aged.

d) understanding that in changing meaning the word may also change form — eg fast can be an adjective or adverb meaning quick(ly) or a verb or noun related to a period of voluntarily going without food.

e) understanding what variety of English the word belongs to :

- is it informal, neutral or formal? Eg nosh — food — comestibles

- does it belong to a specific regional variety of the language (eg bairn in Scottish English), or does it have different meanings in different varieties of English? For example, biscuit in US and UK English.

- is it considered vulgar or taboo? Eg bollocks, asshole, shit

- is it an «everyday» term or a technical term and if the latter in what field? Eg feelers vs antennae in biology

- is it used in current English or is it archaic? Eg betwixt, damsel, looking glass

f) knowing how to decode the word when it is heard or read, and how to pronounce and spell it when it is used. The lack of a one-to-one correspondence between spelling and pronunciation in English makes this feature more important than in many other languages, the classic example being the variation of pronunciation of -ough in words like though, through, thought, tough, and cough. Pronunciation also involves knowledge of stress patterns and how changes in the form of the word may affect this : consider ˈphotograph, phoˈtographer, photoˈgraphic In addition, both spelling and pronunciation may be affected by the differences in variety of English mentioned in (g) above. For example — the pronunciation of new as /nju:/ in British English but /nu:/ in American English; and the change in spelling from -our in British English (behaviour, colour) to -or in US English (behavior, color)

g) understanding how affixes can change the form and meaning of the word — eg help, helpful, unhelpful, helpfully, helpless, helplessness etc

h) knowing how it relates to other words in lexical sets. This includes relationships such as:

- hyponymy — for example a car is member of the category vehicle and thus asociated with other members of that category : bus, coach, lorry, motorbike etc.

- meronymy — for example an arm is part of a body and as such is associated with other parts such as leg, hand, head, ear etc.

- synonymy — words with the same meaning — eg flower, bloom, blossom

- antonymy — opposites ; big-small, dead-alive, open-close etc.

i) knowing its place in one or more specific lexical fields, and the other words likely to be found in that field. Eg dig is part of the lexical field gardening and as such is connected to words such as plant, fertiliser, roses, roots, secateurs, mow etc. But it is also part of the lexical field archaeology, where it will have a different set of associations.

j) knowing its use in fixed and semi-fixed lexical chunks, such as multiword verbs (eg run in run out of) collocations (the use of heavy in heavy rain), idioms (to get cold feet), binomials (trial and error), and other types of figurative language which I discussed in detail here.

All this begs one important question however : are we talking about receptive understanding or productive use? Obviously, some features of the word — eg its basic denotation and possible connotations — are important for both, while colligation is perhaps only necessary for productive use. This will affect how we decide to teach the words, but so may other factors : what level are the learners? How can we teach lexis in such a way as to promote retention? Which other of the factors listed above should we take into consideration and how do we do it? These questions will be discussed in another article — coming soon!

time to complete: 15-20 minutes

Let’s now turn to what it means to know a word. Obviously, knowing a word means to be able to identify it when reading or listening and use it when writing or speaking. But, what kind of information do you need to know to do all this successfully? In other words, what is it about a word that you need to know?

To answer this question, do the following tasks. The first one introduces you to the basics, while the second covers more advanced information.

Types of vocabulary knowledge I

Types of vocabulary knowledge II

Formal vs. informal

At this point, it is worth mentioning that some of these types of vocabulary knowledge might be more relevant or useful than others, depending on the context and how much you already know. For example, idioms tend to be informal and therefore not appropriate for academic writing, but they can help you sound more natural when socialising with your fellow students:

❌ (in writing)

Researchers have been scratching their heads over the sudden decrease…

✔️ (in speaking)

-Munirah, could you help me with Question 5? I’ve been scratching my head over it all morning!

Similarly, you should always consider whether a word you are learning is formal or informal and appropriate for your studies. For example, the verb ‘get’ is in the Oxford3000 list but it is rather informal. When writing, you would need to use more formal synonyms e.g. obtain, receive, acquire, gain, earn, collect, etc., depending on the meaning of course.

Task: To practise formal and informal vocabulary, do the following task.