The Greek language has contributed to the English lexicon in five main ways:

- vernacular borrowings, transmitted orally through Vulgar Latin directly into Old English, e.g., ‘butter’ (butere, from Latin butyrum < βούτυρον), or through French, e.g., ‘ochre’;

- learned borrowings from classical Greek texts, often via Latin, e.g., ‘physics’ (< Latin physica < τὰ φυσικά);

- a few borrowings transmitted through other languages, notably Arabic scientific and philosophical writing, e.g., ‘alchemy’ (< χημεία);

- direct borrowings from Modern Greek, e.g., ‘ouzo’ (ούζο);

- neologisms (coinages) in post-classical Latin or modern languages using classical Greek roots, e.g., ‘telephone’ (< τῆλε + φωνή) or a mixture of Greek and other roots, e.g., ‘television’ (< Greek τῆλε + English vision < Latin visio); these are often shared among the modern European languages, including Modern Greek.

Of these, the neologisms are by far the most numerous.

Indirect and direct borrowings[edit]

Since the living Greek and English languages were not in direct contact until modern times, borrowings were necessarily indirect, coming either through Latin (through texts or through French and other vernaculars), or from Ancient Greek texts, not the living spoken language.[5][6]

Vernacular borrowings[edit]

Romance languages[edit]

Some Greek words were borrowed into Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. English often received these words from French. Some have remained very close to the Greek original, e.g., lamp (Latin lampas; Greek λαμπάς). In others, the phonetic and orthographic form has changed considerably. For instance, place was borrowed both by Old English and by French from Latin platea, itself borrowed from πλατεία (ὁδός), ‘broad (street)’; the Italian piazza and Spanish plaza have the same origin, and have been borrowed into English in parallel.

The word olive comes through the Romance from the Latin olīva, which in turn comes from the archaic Greek elaíwā (ἐλαίϝᾱ).[7] A later Greek word, boútȳron (βούτυρον),[8] becomes Latin butyrum and eventually English butter. A large group of early borrowings, again transmitted first through Latin, then through various vernaculars, comes from Christian vocabulary:

- chair << καθέδρα (cf. ‘cathedra’);

- bishop << epískopos (ἐπίσκοπος ‘overseer’);

- priest << presbýteros (πρεσβύτερος ‘elder’); and

In some cases, the orthography of these words was later changed to reflect the Greek—and Latin—spelling: e.g., quire was respelled as choir in the 17th century. Sometimes this was done incorrectly: ache is from a Germanic root; the spelling ache reflects Samuel Johnson’s incorrect etymology from ἄχος.[9]

Other[edit]

Exceptionally, church came into Old English as cirice, circe via a West Germanic language. The Greek form was probably kȳriakḗ [oikía] (κυριακή [οἰκία] ‘lord’s [house]’). In contrast, the Romance languages generally used the Latin words ecclēsia or basilica, both borrowed from Greek.

Learned borrowings[edit]

Many more words were borrowed by scholars writing in Medieval and Renaissance Latin. Some words were borrowed in essentially their original meaning, often transmitted through Classical Latin: topic, type, physics, iambic, eta, necromancy, cosmopolite. A few result from scribal errors: encyclopedia < ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία ‘the circle of learning’ (not a compound in Greek); acne < ἀκνή (erroneous) < ἀκμή ‘high point, acme’. Some kept their Latin form, e.g., podium < πόδιον.

Others were borrowed unchanged as technical terms, but with specific, novel meanings:

- telescope < τηλεσκόπος ‘far-seeing’, refers to an optical instrument for seeing far away rather than a person who can see far into the distance;

- phlogiston < φλογιστόν ‘burnt thing’, is a supposed fire-making potential rather than something which has been burned, or can be burned; and

- bacterium < βακτήριον ‘stick (diminutive)’, is a kind of microorganism rather than a small stick or staff.

Usage in neologisms[edit]

But by far the largest Greek contribution to English vocabulary is the huge number of scientific, medical, and technical neologisms that have been coined by compounding Greek roots and affixes to produce novel words which never existed in the Greek language:

- utopia (1516; οὐ ‘not’ + τόπος ‘place’)[10]

- zoology (1669; ζῷον + λογία)

- hydrodynamics (1738; ὕδωρ + δυναμικός)

- photography (1834; φῶς + γραφικός)

- oocyte (1895; ᾠόν + κύτος)

- helicobacter (1989; ἕλιξ + βακτήριον)

So it is really the combining forms of Greek roots and affixes that are borrowed, not the words. Neologisms using these elements are coined in all the European languages, and spread to the others freely—including to Modern Greek, where they are considered to be reborrowings. Traditionally, these coinages were constructed using only Greek morphemes, e.g., metamathematics, but increasingly, Greek, Latin, and other morphemes are combined. These hybrid words were formerly considered to be ‘barbarisms’, such as:

- television (τῆλε + Latin vision);

- metalinguistic (μετά + Latin lingua + -ιστής + -ικος); and

- garbology (English garbage + -ολογία).

Some derivations are idiosyncratic, not following Greek compounding patterns, for example:[11]

- gas (< χάος) is irregular both in formation and in spelling;

- hadron < ἁδρός with the suffix -on, itself abstracted from Greek anion (ἀνιόν);

- henotheism < ἑνό(ς) ‘one’ + θεός ‘god’, though heno- is not used as a prefix in Greek;

- taxonomy < τάξις ‘order’ + -nomy (-νομία ‘study of’), where the «more etymological form» is taxinomy,[1][12] as found in ταξίαρχος, ‘taxiarch’, and the neologism taxidermy. Modern Greek uses ταξινομία in its reborrowing.[13]

- psychedelic < ψυχή ‘psyche’ + δηλοῦν ‘make manifest, reveal’; the regular formation would be psychodelotic;

- telegram; the regular formation would have been telegrapheme;[14]

- hecto-, kilo-, myria-, etymologically hecato-, chilio-, myrio-;[15]

- heuristic, regular formation heuretic;

- chrysalis, regular spelling chrysallis;

- ptomaine, regular formation ptomatine;

- kerosene, hydrant, symbiont.

Many combining forms have specific technical meanings in neologisms, not predictable from the Greek sense:

- -cyte or cyto- < κύτος ‘container’, means biological cells, not arbitrary containers.

- -oma < -ωμα, a generic morpheme forming deverbal nouns, such as diploma (‘a folded thing’) and glaucoma (‘greyness’), comes to have the very narrow meaning of ‘tumor’ or ‘swelling’, on the model of words like carcinoma < καρκίνωμα. For example, melanoma does not come from μελάνωμα ‘blackness’, but rather from the modern combining forms melano- (‘dark’ [in biology]) + -oma (‘tumor’).

- -itis < -ῖτις, a generic adjectival suffix; in medicine used to mean a disease characterized by inflammation: appendicitis, conjunctivitis, …, and now facetiously generalized to mean «feverish excitement».[16]

- -osis < -ωσις, originally a state, condition, or process; in medicine, used for a disease.[16]

In standard chemical nomenclature, the numerical prefixes are «only loosely based on the corresponding Greek words», e.g. octaconta- is used for 80 instead of the Greek ogdoeconta- ’80’. There are also «mixtures of Greek and Latin roots», e.g., nonaconta-, for 90, is a blend of the Latin nona- for 9 and the Greek -conta- found in words such as ἐνενήκοντα enenekonta ’90’.[17] The Greek form is, however, used in the names of polygons in mathematics, though the names of polyhedra are more idiosyncratic.

Many Greek affixes such as anti- and -ic have become productive in English, combining with arbitrary English words: antichoice, Fascistic.

Some words in English have been reanalyzed as a base plus suffix, leading to suffixes based on Greek words, but which are not suffixes in Greek (cf. libfix). Their meaning relates to the full word they were shortened from, not the Greek meaning:

- -athon or -a-thon (from the portmanteau word walkathon, from walk + (mar)athon).

- -ase, used in chemistry for enzymes, is abstracted from diastase, where —ασις is not a morpheme at all in Greek.

- -on for elementary particles, from electron: lepton, neutron, phonon, …

- -nomics refers specifically to economics: Reaganomics.

Through other languages[edit]

Some Greek words were borrowed through Arabic and then Romance. Many are learned:

- alchemy (al- + χημεία or χημία)

- chemist is a back-formation from alchemist

- elixir (al- + ξήριον)

- alembic (al- + ἄμβιξ)

Others are popular:

- bottarga (ᾠοτάριχον)

- tajine (τάγηνον)

- carat (κεράτιον)

- talisman (τέλεσμα)

- possibly quintal (κεντηνάριον < Latin centenarium (pondus)).

A few words took other routes:[18]

- seine (a kind of fishing net) comes from a West Germanic form *sagīna, from Latin sagēna, from σαγήνη.

- effendi comes from Turkish, borrowed from Medieval Greek αυθέντης (/afˈθendis/, ‘lord’).

- hora (the dance) comes from Romanian and Modern Hebrew, borrowed from χορός ‘dance’.

Vernacular or learned doublets[edit]

Some Greek words have given rise to etymological doublets, being borrowed both through a later learned, direct route, and earlier through an organic, indirect route:[19][20]

|

|

Other doublets come from differentiation in the borrowing languages:

|

|

From modern Greek[edit]

Finally, with the growth of tourism and emigration, some words reflecting modern Greek culture have been borrowed into English—many of them originally borrowings into Greek themselves:

|

|

Greek as an intermediary[edit]

Many words from the Hebrew Bible were transmitted to the western languages through the Greek of the Septuagint, often without morphological regularization:

- rabbi (ραββί)

- seraphim (σεραφείμ, σεραφίμ)

- paradise (παράδεισος < Hebrew < Persian)

- pharaoh (Φαραώ < Hebrew < Egyptian)

Written form of Greek words in English[edit]

Many Greek words, especially those borrowed through the literary tradition, are recognizable as such from their spelling. Latin had standard orthographies for Greek borrowings, including, but not limited to:

- Greek υ was written as ‘y’

- η as ‘e’

- χ as ‘ch’

- φ as ‘ph’

- κ as ‘c’

- rough breathings as ‘h’

- both ι and ει as ‘i’

These conventions, which originally reflected pronunciation, have carried over into English and other languages with historical orthography, like French.[22] They make it possible to recognize words of Greek origin, and give hints as to their pronunciation and inflection.

The romanization of some digraphs is rendered in various ways in English. The diphthongs αι and οι may be spelled in three different ways in English:

- the Latinate digraphs ae and oe;

- the ligatures æ and œ; and

- the simple letter e.

The ligatures have largely fallen out of use worldwide; the digraphs are uncommon in American usage, but remain common in British usage. The spelling depends mostly on the variety of English, not on the particular word. Examples include: encyclopaedia / encyclopædia / encyclopedia; haemoglobin / hæmoglobin / hemoglobin; and oedema / œdema / edema. Some words are almost always written with the digraph or ligature: amoeba / amœba, rarely ameba; Oedipus / Œdipus, rarely Edipus; others are almost always written with the single letter: sphære and hæresie were obsolete by 1700; phænomenon by 1800; phænotype and phænol by 1930. The verbal ending -ίζω is spelled -ize in American English, and -ise or -ize in British English.

Since the 19th century, a few learned words were introduced using a direct transliteration of Ancient Greek and including the Greek endings, rather than the traditional Latin-based spelling: nous (νοῦς), koine (κοινή), hoi polloi (οἱ πολλοί), kudos (κύδος), moron (μωρόν), kubernetes (κυβερνήτης). For this reason, the Ancient Greek digraph ει is rendered differently in different words—as i, following the standard Latin form: idol < εἴδωλον; or as ei, transliterating the Greek directly: eidetic (< εἰδητικός), deixis, seismic. Most plurals of words ending in -is are -es (pronounced [iːz]), using the regular Latin plural rather than the Greek -εις: crises, analyses, bases, with only a few didactic words having English plurals in -eis: poleis, necropoleis, and acropoleis (though acropolises is by far the most common English plural).

Most learned borrowings and coinages follow the Latin system, but there are some irregularities:

- eureka (cf. heuristic);

- kaleidoscope (the regular spelling would be calidoscope[6])

- kinetic (cf. cinematography);

- krypton (cf. cryptic);

- acolyte (< ἀκόλουθος; acoluth would be the etymological spelling, but acolythus, acolotus, acolithus are all found in Latin);[23]

- stoichiometry (< στοιχεῖον; regular spelling would be st(o)echio-).

- aneurysm was formerly often spelled aneurism on the assumption that it uses the usual -ism ending.

Some words whose spelling in French and Middle English did not reflect their Greco-Latin origins were refashioned with etymological spellings in the 16th and 17th centuries: caracter became character and quire became choir.

In some cases, a word’s spelling clearly shows its Greek origin:

- If it includes ph pronounced as /f/ or y between consonants, it is very likely Greek, with some exceptions, such as nephew, cipher, triumph.[24]

- If it includes rrh, phth, or chth; or starts with hy-, ps-, pn-, or chr-; or the rarer pt-, ct-, chth-, rh-, x-, sth-, mn-, tm-, gn- or bd-, then it is Greek, with some exceptions: gnat, gnaw, gneiss.

Other exceptions include:

- ptarmigan is from a Gaelic word, the p having been added by false etymology;

- style is probably written with a ‘y’ because the Greek word στῦλος ‘column’ (as in peristyle, ‘surrounded by columns’) and the Latin word stilus, ‘stake, pointed instrument’, were confused.

- trophy, though ultimately of Greek origin, did not have a φ but a π in its Greek form, τρόπαιον.

Pronunciation[edit]

In clusters such as ps-, pn-, and gn- which are not allowed by English phonotactics, the usual English pronunciation drops the first consonant (e.g., psychology) at the start of a word; compare gnostic [nɒstɪk] and agnostic [ægnɒstɪk]; there are a few exceptions: tmesis [t(ə)miːsɪs].

Initial x- is pronounced z. Ch is pronounced like k rather than as in «church»: e.g., character, chaos. The consecutive vowel letters ‘ea’ are generally pronounced separately rather than forming a single vowel sound when transcribing a Greek εα, which was not a digraph, but simply a sequence of two vowels with hiatus, as in genealogy or pancreas (cf., however, ocean, ωκεανός); zeal (earlier zele) comes irregularly from the η in ζήλος.

Some sound sequences in English are only found in borrowings from Greek, notably initial sequences of two fricatives, as in sphere.[25] Most initial /z/ sounds are found in Greek borrowings.[25]

The stress on borrowings via Latin which keep their Latin form generally follows the traditional English pronunciation of Latin, which depends on the syllable structure in Latin, not in Greek. For example, in Greek, both ὑπόθεσις (hypothesis) and ἐξήγησις (exegesis) are accented on the antepenult, and indeed the penult has a long vowel in exegesis; but because the penult of Latin exegēsis is heavy by Latin rules, the accent falls on the penult in Latin and therefore in English.

Inflectional endings and plurals[edit]

Though many English words derived from Greek through the literary route drop the inflectional endings (tripod, zoology, pentagon) or use Latin endings (papyrus, mausoleum), some preserve the Greek endings:

- -ον: phenomenon, criterion, neuron, lexicon;

- —∅: plasma, drama, dilemma, trauma (-ma is derivational, not inflectional);

- -ος: chaos, ethos, asbestos, pathos, cosmos;

- -ς: climax (ξ x = k + s), helix, larynx, eros, pancreas, atlas;

- -η: catastrophe, agape, psyche;

- -ις: analysis, basis, crisis, emphasis;

- -ης: diabetes, herpes, isosceles.

In cases like scene, zone, fame, though the Greek words ended in -η, the silent English e is not derived from it.

In the case of Greek endings, the plurals sometimes follow the Greek rules: phenomenon, phenomena; tetrahedron, tetrahedra; crisis, crises; hypothesis, hypotheses; polis, poleis; stigma, stigmata; topos, topoi; cyclops, cyclopes; but often do not: colon, colons not *cola (except for the very rare technical term of rhetoric); pentathlon, pentathlons not *pentathla; demon, demons not *demones; climaxes, not *climaces.

Usage is mixed in some cases: schema, schemas or schemata; lexicon, lexicons or lexica; helix, helixes or helices; sphinx, sphinges or sphinxes; clitoris, clitorises or clitorides. And there are misleading cases: pentagon comes from Greek pentagonon, so its plural cannot be *pentaga; it is pentagons—the Greek form would be *pentagona (cf. Plurals from Latin and Greek).

Verbs[edit]

A few dozen English verbs are derived from the corresponding Greek verbs; examples are baptize, blame and blaspheme, stigmatize, ostracize, and cauterize. In addition, the Greek verbal suffix -ize is productive in Latin, the Romance languages, and English: words like metabolize, though composed of a Greek root and a Greek suffix, are modern compounds. A few of these also existed in Ancient Greek, such as crystallize, characterize, and democratize, but were probably coined independently in modern languages. This is particularly clear in cases like allegorize and synergize, where the Greek verbs ἀλληγορεῖν and συνεργεῖν do not end in -ize at all. Some English verbs with ultimate Greek etymologies, like pause and cycle, were formed as denominal verbs in English, even though there are corresponding Greek verbs, παῦειν/παυσ- and κυκλεῖν.

Borrowings and cognates[edit]

Greek and English share many Indo-European cognates. In some cases, the cognates can be confused with borrowings. For example, the English mouse is cognate with Greek μῦς /mys/ and Latin mūs, all from an Indo-European word *mūs; they are not borrowings. Similarly, acre is cognate to Latin ager and Greek αγρός, but not a borrowing; the prefix agro- is a borrowing from Greek, and the prefix agri- a borrowing from Latin.

Phrases[edit]

Many Latin phrases are used verbatim in English texts—et cetera (etc.), ad nauseam, modus operandi (M.O.), ad hoc, in flagrante delicto, mea culpa, and so on—but this is rarer for Greek phrases or expressions:

- hoi polloi ‘the many’

- eureka ‘I have found [it]’

- kalos kagathos ‘beautiful and virtuous’

- hapax legomenon ‘once said’

- kyrie eleison ‘Lord, have mercy’

Calques and translations[edit]

Greek technical terminology was often calqued in Latin rather than borrowed,[26][27] and then borrowed from Latin into English. Examples include:[26]

- (grammatical) case, from casus (‘an event’, something that has fallen’), a semantic calque of Greek πτώσις (‘a fall’);

- nominative, from nōminātīvus, a translation of Greek ὀνομαστική;

- adverb, a morphological calque of Greek ἐπίρρημα as ad- + verbum;

- magnanimous, from Greek μεγάθυμος (lit. ‘great spirit’);

- essence, from essentia, which was constructed from the notional present participle *essens, imitating Greek οὐσία.[28]

- Substance, from substantia, a calque of Greek υπόστασις (cf. hypostasis);[29]

- Cicero coined moral on analogy with Greek ηθικός.[30]

- Recant is modeled on παλινῳδεῖν.[31]

Greek phrases were also calqued in Latin, then borrowed or translated into English:

- English commonplace is a calque of locus communis, itself a calque of Greek κοινός τόπος.

- deus ex machina ‘god out of the machine’ was calqued from the Greek apò mēkhanês theós (ἀπὸ μηχανῆς θεός).

- materia medica is a short form of Dioscorides‘ De Materia Medica, from Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς.

- quod erat demonstrandum (Q.E.D.) is a calque of ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι.

- subject matter is a calque of subiecta māteria, itself a calque of Aristotle’s phrase «ἡ ὑποκειμένη ὕλη.»

- wisdom tooth came to English from dentes sapientiae, from Arabic aḍrāsu ‘lḥikmi, from σωϕρονιστῆρες, used by Hippocrates.

- political animal is from πολιτικὸν ζῷον (in Aristotle’s Politics).

- quintessence is post-classical quinta essentia, from Greek πέμπτη οὐσία.

The Greek word εὐαγγέλιον has come into English both in borrowed forms like evangelical and the form gospel, an English calque (Old English gód spel ‘good tidings’) of bona adnuntiatio, itself a calque of the Greek.

Statistics[edit]

The contribution of Greek to the English vocabulary can be quantified in two ways, type and token frequencies: type frequency is the proportion of distinct words; token frequency is the proportion of words in actual texts.

Since most words of Greek origin are specialized technical and scientific coinages, the type frequency is considerably higher than the token frequency. And the type frequency in a large word list will be larger than that in a small word list. In a typical English dictionary of 80,000 words, which corresponds very roughly to the vocabulary of an educated English speaker, about 5% of the words are borrowed from Greek.[32]

Most common[edit]

Of the 500 most common words in English, 18 (3.6%) are of Greek origin: place (rank 115), problem (121), school (147), system (180), program (241), idea (252), story (307), base (328), center (335), period (383), history (386), type (390), music (393), political (395), policy (400), paper (426), phone (480), economic (494).[33]

See also[edit]

- List of Greek and Latin roots in English

- List of Greek morphemes used in English

- List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names

- Transliteration of Greek into English

- Classical compound

- Hybrid word

- Latin influence in English

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary, by subscription

- ^ Online Etymological Dictionary, free

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, free

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, free

- ^ Ayers, Donald M. 1986. English Words from Latin and Greek Elements. (2nd ed.). p. 158.

- ^ a b Tom McArthur, ed., The Oxford companion to the English language, 1992, ISBN 019214183X, s.v. ‘Greek’, p. 453-454

- ^ This must have been an early borrowing, since the Latin v reflects a still-pronounced digamma; the earliest attested form of it is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀁𐀨𐀷, e-ra3-wo ‘elaiwo(n)’, attested in Linear B syllabic script. (see C.B. Walker, John Chadwick, Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet, 1990, ISBN 0520074319, p. 161) The Greek word was in turn apparently borrowed from a pre-Indo-European Mediterranean substrate; cf. Greek substrate language.

- ^ Carl Darling Buck, A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages (ISBN 0-226-07937-6) notes that the word has the form of a compound βοΰς + τυρός ‘cow-cheese’, possibly a calque from Scythian, or possibly an adaptation of a native Scythian word.

- ^ Okrent, Arika. October 8, 2014. «5 Words That Are Spelled Weird Because Someone Got the Etymology Wrong.» Mental Floss. (Also in OED.)

- ^ The 14th-century Byzantine monk Neophytos Prodromenos independently coined the word in Greek in his Against the Latins, with the meaning ‘absurdity’.

- ^ These are all listed as «irregularly formed» in the Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Both are used in French; see: Jean-Louis Fisher, Roselyne Rey, «De l’origine et de l’usage des termes taxinomie-taxonomie», Documents pour l’histoire du vocabulaire scientifique, Institut national de la langue française, 1983, 5:97-113

- ^ Andriotis et al., Λεξικό της κοινής νεοελληνικής = Triantafyllidis Dictionary, s.v.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v.

- ^ Thomas Young as reported in Brewster, David (1832). The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia. Vol. 12 (1st American ed.). Joseph and Edward Parker. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ a b Simeon Potter, Our language, Penguin, 1950, p. 43

- ^ N. Lozac’h, «Extension of Rules A-1.1 and A-2.5 concerning numerical terms used in organic chemical nomenclature (Recommendations 1986)», Pure and Applied Chemistry 58:12:1693-1696 doi:10.1351/pac198658121693, under «Discussion», p. 1694-1695 full texte.g.%2C%20nona-%20for%209%2C%20undeca-%20for%2011%2C%20nonaconta-%20for%2090). deep link to WWW version

- ^ Skeat gives more on p. 605-606, but the Oxford English Dictionary does not agree with his etymologies of cobalt, nickel, etc.

- ^ Walter William Skeat, A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, «List of Doublets», p. 599ff (full text)

- ^ Edward A. Allen, «English Doublets», Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 23:2:184-239 (1908) doi:10.2307/456687 JSTOR 456687

- ^ Etymology is disputed; perhaps from Latin Christianus, as a euphemism; perhaps from Latin crista, referring to a symptom of iodine deficiency

- ^ Crosby, Henry Lamar, and John Nevin Schaeffer. 1928. An Introduction to Greek. section 66.

- ^ Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, s.v.

- ^ Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia, 1897, s.v., p. 4432

- ^ a b Hickey, Raymond. «Phonological change in English.» In The Cambridge Handbook of English Historical Linguistics 12.10, edited by M. Kytö and P. Pahta.

- ^ a b Fruyt, Michèle. «Latin Vocabulary.» In A Companion to the Latin Language, edited by J. Clackson. p. 152.

- ^ Eleanor Detreville, «An Overview of Latin Morphological Calques on Greek Technical Terms: Formation and Success», M.A. thesis, University of Georgia, 2015, full text

- ^ Joseph Owens, Étienne Henry Gilson, The Doctrine of Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics, 1963, p. 140

- ^ F.A.C. Mantello, Medieval Latin, 1996, ISBN 0813208416, p. 276

- ^ Wilhelm Wundt et al., Ethics: An Investigation of the Facts and Laws of the Moral Life, 1897, p. 1:26

- ^ A.J. Woodman, «O MATRE PVLCHRA: The Logical Iambist: To the memory of Niall Rudd«, The Classical Quarterly 68:1:192-198 (May 2018) doi:10.1017/S0009838818000228, footnote 26

- ^ Scheler, Manfred. 1977. Der englische Wortschatz. Berlin: Schmidt.

- ^ New General Service List, [1]

Sources[edit]

- Baugh, Albert C., Thomas Cable. 2002. A History of the English Language, 5th edition. ISBN 0415280990

- Gaidatzi, Theopoula. July 1985. «Greek loanwords in English» (M.A. thesis). University of Leeds

- Konstantinidis, Aristidis. 2006. Η Οικουμενική Διάσταση της Ελληνικής Γλώσσας [The Universal Reach of the Greek Language]. Athens: self-published. ISBN 960-90338-2-2.

- Krill, Richard M. 1990. Greek and Latin in English Today. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-241-7.

- March, F. A. 1893. «The Influence of the Greeks on the English Language.» The Chautauquan 16(6):660–66.

- —— 1893. «Greek in the English of Modern Science.» The Chautauquan 17(1):20–23.

- Scheler, Manfred. 1977. Der englische Wortschatz [English vocabulary]. Berlin: Schmidt.

- Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.)

External links[edit]

- Mathematical Words: Origins and Sources (John Aldrich, University of Southampton)

After French, Latin and Viking (and Old English of course, but that is English), the Greek language has contributed more words to modern English than any other – perhaps 5%.

Many Greek words sprang from Greek mythology and history. Knowing those subjects was evidence that a person was educated, so dropping a reference to Greek literature was encouraged even into the 20th century. From Greek mythology, we get words such as atlas, chaos, chronological, erotic, herculean, hypnotic, muse, nectar, promethean, and even cloth.

But most Greek-origin words in English did not come straight from ancient Greek. Many are modern, not ancient, combinations of Greek root words. For example, you probably know the telephone was not used by the ancient Greeks. But the word itself is all Greek, made up of the Greek words for “distant” and “sound.” Besides tele and phon, common Greek roots include anti, arch, auto, bio, centro, chromo, cyclo, demo, dys, eu, graph, hydro, hypo, hyper, logo, macro, mega, meta, micro, mono, paleo, para, philo, photo, poly, pro, pseudo, psycho, pyro, techno, thermo and zoo. Among others.

Comparing the original and the modern meanings of Greek words that became English words sometimes shows not only how much language has changed, but how much culture has changed.

- idiot

Someone of very low intelligence. For the ancient Greeks, an idiot was a private citizen, a person not involved in civil government or politics. Related: idiosyncracy, idiom, and other individualistic words. - metropolis

The Greek roots of this word are “mother” and “city.” Socrates, convicted in court of corrupting the youth with his philosophy, was given a choice between drinking poison or exile from his mother city of Athens. He chose poison because he wasn’t an idiot, in the ancient sense. If you chose exile, you might be an idiot in the ancient sense, but you would be a live idiot. - acrobat

This circus performer who demonstrates feats of physical agility by climbing to the very top of the rope gets his name from the Greek words “high” and “walk,” with the sense of “rope dancer” and “tip-toe.” - bacterium

From a Greek word that means “stick” because under a microscope (another Greek word), some bacteria look like sticks. - cemetery

The Greek word koimeterion meant “sleeping place, dormitory.” Early Christian writers adopted the word for “burial ground,” and that’s why college students stay in the dormitory and not in the cemetery. - dinosaur

You may have heard this one before. Our word for these ancient reptiles is a modern (1841) combination of the Greek words for “terrible” and “lizard. - hippopotamus

The ancient Greeks called this large, moist African animal a hippopótamos, from the words for “horse” and “river.” In other words, river horse. - rhinoceros

Continuing our African theme, this large, dry African animal is named after the Greek words for “nose” and “horn.” Horns usually don’t grow on noses. - history

The Greek word historía meant “inquiry, record, narrative.” - dialogue

A monologue has one speaker, but a dialogue doesn’t necessarily have two speakers (that would be a “di-logue,” but there’s no such word). Dialogue comes from Greek words that mean “across-talk,” and more than two people can do that if they take turns. - economy

The Greek word for “household administration” has been expanded to mean the management of money, goods, and services for an entire community or nation. But “economical” still refers to personal thrift. - metaphor

In ancient times, this word meant “transfer” or “carrying over.” When my grandfather called my grandmother a peach, metaphorically speaking, he used a figure of speech that transferred the sweetness of the fruit to his sweet wife. - planet

The ancient Greeks get blamed for everything wrong with astronomy before the Renaissance, but they were astute enough to notice that while most stars stood still, some wandered from year to year. The word planet comes from the Greek word for “wandering.” - schizophrenia

People with this mental disorder have been described as having a “split personality,” and the name comes from Greek words for “split” and “mind.” Symptoms may include hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech. - technology

This word was not limited to industry or science until the mid-19th century, during the Industrial Revolution. Originally it referred to “technique” (same Greek root) or the systematic study of an art or craft – the art of grammar, at first, and later the fine arts. - grammatical

Speaking of grammar, the Ancient Greek word grammatike meant “skilled in writing.” Now it means “correct in writing.” - syntax

A combination of Ancient Greek words that mean “together” and “arrangement.” Syntax is how words are arranged together. - sarcasm

Though it was used to describe bitter sneering, the Greek word sarkazein literally meant “to cut off flesh,” which you might feel has happened to you when subjected to cutting sarcasm or critical humor. - sycophant

Not a word that I’ve ever used, but you might like it. It means “servile, self-seeking flatterer.” In ancient Greek, it meant “one who shows the fig.” That referred to an insulting hand gesture that respectable Greek politicians wouldn’t use against their opponents, but whose shameless followers could be encouraged to do so. - telescope

Another all-Greek word that wasn’t invented by the Greeks, but perhaps by the Dutch around 1600. Its roots mean “far-seeing” and Galileo Galilei was one of the first astronomers to use a telescope to see faraway things.

As you can see, Greek is deeply woven into modern English. To prove it, in the late 1950s, Greek economist Xenophon Zolotas gave two speeches in English, but using only Greek words, except for articles and prepositions. The results were rather high-sounding, but mostly comprehensible. As you become more familiar with Greek words, English will be easier to understand. And probably, more colorful.

You will face the wrath of many linguists if you suggest that English is a hybrid language. But at least in terms of vocabulary, it’s true. Over 60 percent of the vocabulary of English consists of words with Latin or Greek roots, and if we focus specifically on the sciences, the number hits the roof. The majority of these words have roots in Latin, but a large number have roots in Greek as well.

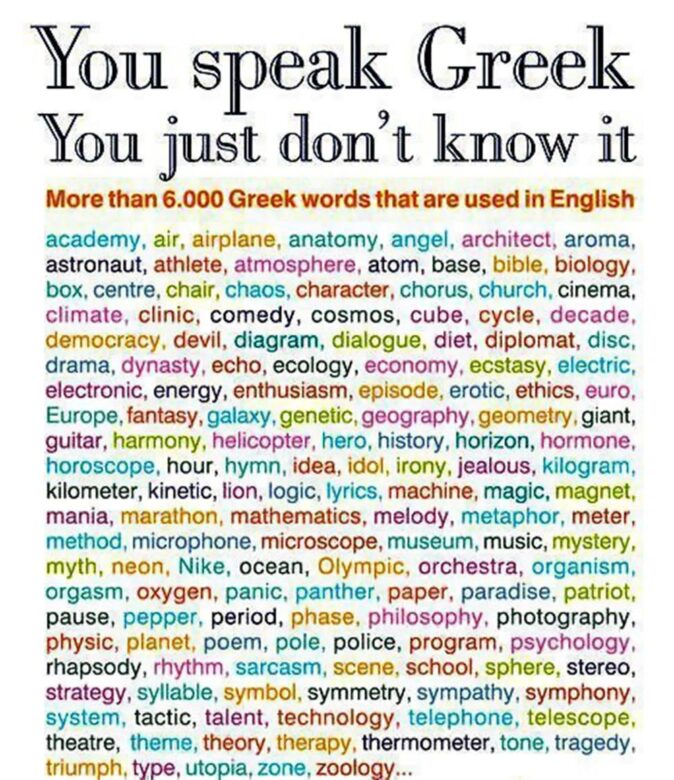

Some estimate that around 6% of English vocabulary derives from Greek, but the estimates reach 12-15% (and sometimes even higher), depending

on how they are measured. Either way, we use Greek words everyday without even knowing it.

In my recent video “How did Greek Influence English?” I gave many examples of English words borrowed from Greek (either directly or indirectly via Latin or French), and newly coined words with Greek roots (some of those words being entirely Greek, and some being a hybrid of Greek and Latin roots). In response to that video, viewers wrote many informative comment giving additional interesting examples.

How Did Greek Influence English?

A few examples used in everyday English:

chair – fomes from Old French “chaiere”, from the Latin “cathedra”, from the Greek “καθέδρα” (kathédra). “καθέδρα” was a compound of κατά (katá) meaning “down”, and ἕδρα (hédra) meaning “seat”.

desk – from Ancient Greek δίσκος (diskos), which then entered Latin as “discus”, then medieval Latin “desca” was borrowed into English.

paper – from Ancient Greek πάπυρος (pápuros), because papyrus stocks functioned as paper. This word which was then borrowed into Latin as papyrus, then into Old French as “papier”, then into English.

kilogram – This word was borrowed from the French word kilogramme, but it traces back to Greek χίλιοι (khílioi) meaning “thousand” and γράμμα (grámma) meaning “small weight”.

automatic – This word entered English from French “automatique” which traces back to Greek αὐτόματον (autómaton), a compound of αὐτός (autós) meaning “self” and μέμαα (mémaa) meaning “to wish eagerly, strive, yearn, desire”. So I guess the original sense of “automatic” was self-motivated or something to that effect.

telephone — “tele” comes from τῆλε (têle) meaning “far” and φωνή (phōnḗ) meaning “voice/sound”. This word was non-existent in Greek but was coined in French using Greek roots in the 19th century.

idiot – from Greek ἰδιώτης (idiṓtēs) – meaning ”private citizen, one who has no professional knowledge, layman”. This word referred to people who were not involved in public life (ie. politics).

hippopotamus – from Ancient Greek ἱπποπόταμος (hippopótamos), a compound of ίππος (hippos) meaning “horse” and ποταμος (potamos) meaning “river”. So “hippopotamus” means river horse!

history – from Greek ἱστορία (historía), which entered Latin as “historia” and then Old French as “estoire”, before entering Middle English.

A few more examples related to features of society:

metropolis – from Greek μητρόπολις (mētrópolis) – a combination of μήτηρ (mḗtēr) meaning “mother” and πόλις (pólis) meaning “city” or “city state”. So metropolis means “mother city” or “main city”.

economy – from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomía), meaning “management of a household, administration”)

Technology – from Greek τεχνολογία (tekhnología), meaning “systematic treatment of an art, craft, or technique”. The original Greek word was used in reference to grammar, and the original English word (adopted around 1610) was used to refer to the arts. The meaning of “study of mechanical and industrial arts” dates back to 1859.

And lots of words relating to language and linguistics come from Greek:

grammar – from Ancient Greek γραμματική (grammatikḗ), meaning “skilled in writing”, which made it’s way into Latin as “grammatica”, then Old French as “gramaire”, which was borrowed into Middle English.

syntax – from Ancient Greek σύνταξις (súntaxis), a compound word containing σύν (sún) meaning “together”, and τάξις (táxis) meaning “arrangement”. So “syntax” literally means “arrange together”.

Dialogue – from Ancient Greek διάλογος (diálogos) meaning “conversation” or “discourse”, which then entered Latin as “dialogus”, then Old French as “dialoge”, and then English.

Metaphor – from Ancient Greek μεταφορά (metaphorá) which meant “transfer” or “carrying over”. This referred to the transfer of meaning from one word to another. This word then entered Latin as “metaphora”, then Middle French as “métaphore”, before entering English.

Language and linguistics is one academic area in which Greek provides much of the specialized vocabulary, and this is the case in academic English in general, from the arts to the sciences.

As we’ve seen from the small number of examples above, and from the linked Langfocus video, Greek words really permeate every area of English vocabulary. And this is not only the case for English. Greek has had a similar amount of influence on most modern European languages, particularly in academic fields and science and technology. It might be fair to say that Greek has greatly influenced an “international academic vocabulary” that crosses language boundaries and doesn’t belong to any one language.

Be sure to watch the video above for more examples, if you haven’t already!

Influence of the Greek(Hellenic) language in today’s word

How many Greek words are in the English language

The Guinness Book of Records ranks the Hellenic language as the richest in the world with 5 million words and 70 million word types!

Hellenic roots are often used to coin new words for other languages, especially in the sciences and medicine.

Mathematics, physics, astronomy, democracy, philosophy, athletics, theatre, rhetoric, baptism, and hundreds of other words are Hellenic(Greek), this is a FACT

Greek words and word elements continue to be productive as a basis for coinages: anthropology, photography, telephony, isomer, biomechanics, cinematography, etc…

In a typical everyday 80,000-word English dictionary, about 5% of the words are directly borrowed from Greek; (for example, “phenomenon” is a Hellenic word and even obeys Hellenic grammar rules as the plural is “phenomena”), and another 25% are borrowed indirectly.

So, about 150,000 words in modern English have direct or indirect origins in the ancient Greek language.

This is because there were many Hellenic words borrowed from Latin originally, which then filtered down into English because English borrowed so many words from Latin (for example, “elaiwa” in Greek evolved into the Latin “oliva”, which in turn became “olive” in English).

So, 30% of English words are…Greek!

Hellenic and Latin are the predominant sources of the international scientific vocabulary, however, the percentage of words borrowed from Greek rises much higher than Latin when considering highly scientific vocabulary (for example, “oxytetracycline” is a medical term that has three Hellenic roots).

And finally, had you ever wondered how the world was going to be if the Greek language never existed?

Most of the ideas in this article are borrowed from this website, so greetings belong to them.

Tags

Learn 100 Greek words in 10 minutes!

List of Greek words in English

Only an example of a few words of Greek origin is below with their writing in the modern Greek language and their spelling with Latin characters. Practically unchanged since antiquity.

NOTE: The words on this list are not clickable, if you click on them simply nothing will happen!

- Academy = Ακαδημία (Akademia)

- Acrobat = Ακροβάτης (Akrovates)

- Air = Αέρας, Αήρ (Aeras)

- Airplane = Αεροπλάνο (Aeroplano)

- Anatomy = Ανατομία (Anatomia)

- Angel = Άγγελος (Aggelos)

- Abnormal = Ανώμαλος (Anomalos)

- Anti = Αντι (Anti)

- Archaeo = Αρχαιο (Archaeo)

- Architect = Αρχιτέκτων (Architekton)

- Aroma = Άρωμα (Aroma)

- Astronaut = Αστροναύτης (Astronaftis)

- Athlete = Αθλητής (Athleetees)

- Atlas = Άτλας (Atlas)

- Atmosphere = Ατμόσφαιρα (Atmosphera)

- Atom = Άτομο (Atomo)

- Auto = Αυτο (Afto)

- Bacterium = Βακτήριον (Vakterion)

- Base = Βάση (Vasee)

- Bible = Βίβλος (Veevlos)

- Bio = Βιο (Veeo)

- Biology = Βιολογία (Viologia)

- Box = Βοξ (Vox)

- Cemetery = Κοιμητήριο (Keemeeteerio)

- Centre = Κέντρο (Kentro)

- Centro = Κέντρο (Kentro)

- Chair = Καρέκλα (Karekla)

- Chaos = Χάος (Chaos)

- Character = Χαρακτήρ (Characteer)

- Chorus = Χορός (Choros)

- Chromo = Χρωμο (Chromo)

- Chronological = Χρονολογικό (Chronologiko)

- Cinema = Κινημα (Kinima)

- Climate = Κλιμα, Κλιματικό (Klimatiko)

- Clinic = Κλινική (Kliniki)

- Comedy = Κωμωδία (Komodeea)

- Cosmos = Κόσμος (Kosmos)

- Cube = Κύβος (Kyvos)

- Cycle = Κύκλος (Kyklos)

- Cyclo = Κυκλο (Kyklo)

- Decade = Δεκάδα (Decada)

- Demo = Δημο (Deemo)

- Democracy = Δημοκρατία (Deemokrateea)

- Devil = Διάβολος (Diavolos)

- Diagram = Διάγραμμα (Diagrama)

- Dialogue = Διάλογος (Dialogos)

- Diet = Δίαιτα (Dieta)

- Diplomat = Διπλωμάτης (Diplomates)

- Dinosaur = Δεινόσαυρος (Dinosavros)

- Disc = Δίσκος (Diskos)

- Drama = Δράμα (Drama)

- Dynasty = Δυναστεία (Dynasteia)

- Dys = Δυσ (Dys)

- Echo = Ηχώ (Echo)

- Ecology = Οικολογία (Ekologia)

- Economy = Οικονομία (Ekonomia)

- Ecstasy = Έκσταση (Ekstasi)

- Electric = Ηλεκτρικό (Elektriko)

- Electronic = Ηλεκτρονικό (Eelektroniko)

- Energy = Ενέργεια (Energeia)

- Enthusiasm = Ενθουσιασμός (Enthousiasmos)

- Episode = Επεισόδιο (Episodeio)

- Erotic = Ερωτικό (Erotiko)

- Ethics = ‘Ηθη (Ethe)

- Eu = Ευ (Ef)

- Euro = Ευρώ (Evro)

- Europe = Ευρώπη (Evropee)

- Fantasy = Φαντασία (Fantasia)

- Galaxy = Γαλαξίας (Galaxias)

- Genetic = Γενετικός (Genetikos)

- Geography = Γεωγραφία (Geographia)

- Geometry = Γεωμετρία (Geometria)

- Giant = Γίγαντας (Gigantas)

- Grammatical = Γραμματικό (Grammatiko)

- Graph = Γραφ (Graph)

- Guitar = Κιθάρα (Kithara)

- Harmony = Αρμονία (Armonia), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Helicopter = Ελικόπτερο (Elikoptero), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hercules = Ηρακλής (Eraklees), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hero = Ήρως (Iros), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hippopotamus = Ιπποπόταμος (Ipopotamos), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- History = Ιστορία (Eestoreea), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Horizon = Ορίζοντας (Orizontas), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hormone = Ορμόνη (Ormonee), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Horoscope = Ωροσκόπιο (Oroskopio), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hour = Ώρα (Ora), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hydro = Υδρο (Ydro), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hymn = Ύμνος (Ymnos), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hypo = Υπο (Ypo), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hyper = Υπερ (Yper), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Hypnotic = Υπνωτικό(Ypnotiko), the “h” is rejected in modern Greek.

- Idea = Ιδέα (Idea)

- Idiot = Ιδιώτης (Idiotes)

- Idol = Είδωλο (Idolo)

- Irony = Ειρωνία (Ironea)

- Jealous = Ζήλεια (Zelia)

- Kilogram = Χιλιόγραμμο (Chiliogrammo)

- Kilometer = Χιλιόμετρο (Chiliometro)

- Kinetic = Κινητικό (Kinetiko)

- Lion = Λέων (Leon)

- Logic = Λογικό (Logiko)

- Logo = Λογο (Logo)

- Lyrics = Λυρισμός (Lyrismos)

- Machine = Μηχανή (Mechane)

- Macro = Μακρο (Makro)

- Mega = Μεγα (Mega)

- Magic = Μαγικό (Magiko)

- Meta = Μετα (Meta)

- Metaphor = Μεταφορά (Metaphora)

- Metropolis = Μητρόπολις (Metropolis)

- Micro = Μικρο (Mikro)

- Mono = Μονο (Mono)

- Muse = Μούσα (Musa)

- Mystery = Μυστήριο (Mysterio)

- Myth = Μύθος (Mythos)

- Nectar = Νεκταρ (Nektar)

- Neon = Νέον (Neon)

- Nike = Νίκη (Nike)

- Nine = Εννέα (Enea)

- Ocean = Ωκεανός (Okeanos)

- Olympic = Ολυμπιακός (Olympiakos)

- Orchestra = Ορχήστρα (Orcheestra)

- Organism = Οργανισμός (Organismos)

- Orgasm = Οργασμός (Orgasmos)

- Oxyzen = Οχυγόνο (Oxygono)

- Paleo = Παλαιο (Paleo)

- Panic = Πανικός (Panikos)

- Panther = Πάνθηρας (Pantheras)

- Paper = Πάπυρος (Papeeros)

- Para = Παρα (Para)

- Paradise = Παράδεισος (Paradeisos)

- Patriot = Πατριώτης (Patriotes)

- Pause = Παύση (Pafsi)

- Pepper = Πιπέρι (Peperi)

- Period = Περίοδος (Periodos)

- Phase = Φάση (Phasee)

- Philo = Φιλο (Philo)

- Philosophy = Φιλοσοφία (Philosophia)

- Photo = Φωτο (Photo)

- Photography = Φωτογραφία (Photografia)

- Physic = Φυσική (Physike)

- Planet = Πλανήτης (Planeetes)

- Poem = Ποίημα (Peema)

- Pole = Πόλος (Polos)

- Poly = Πολυ (Poly)

- Pro = Προ (Pro)

- Program = Πρόγραμμα (Programma)

- Pseudo = Ψευδο (Psevdo)

- Psycho = Ψυχο (Psycho)

- Psychology = Ψυχολογία (Psychologia)

- Pyro = Πυρο (Pyro)

- Rhapsody = Ραψωδία (Rapsodia)

- Rhythm = Ρυθμός (Rythmos)

- Rhinoceros = Ρινόκερως (Rinokeros)

- Sarcasm = Σαρκασμός (Sarkasmos)

- Scene = Σκηνή (Skene)

- Schizophrenia = Σχιζοφρένεια (Schizophrenia)

- School = Σχολείο (Scholeeo)

- Sphere = Σφαίρα (Sphera)

- Star = Αστήρ (Asteer)

- Stereo = Στέρεο (Stereo)

- Strategy = Στρατηγική (Strategiki)

- Sycophant = Συκοφάντης (Sykophantes)

- Syllable = Συλλαβή (Syllavee)

- Symbol = Σύμβολο (Symvolo)

- Symmetry = Συμμετρία (Symmetria)

- Sympathy = Συμπάθεια (Sympatheia)

- Symphony = Συμφωνία (Symphonia)

- Syntax = Σύνταξη (Syntaksi)

- System = Σύστημα (Systeema)

- Tactic = Τακτική (Taktikee)

- Talent = Ταλέντο (Talento)

- Techno = Τεχνο (Techno)

- Technology = Τεχνολογία (Technologia)

- Telescope = Τηλεσκόπιο (Teleskopio)

- Telephone = Τηλέφωνο (Telephono)

- Television = Τηλεόραση (Teleorasi)

- Theatre = Θέατρο (Theatro)

- Theme = Θέμα (Thema)

- Theory = Θεωρία (Theoria)

- Therapy = Θεραπεία (Therapia)

- Thermo = Θερμο (Thermo)

- Thermometer = Θερμόμετρο (Thermometro)

- Third = Τρίτο (Treeto)

- Tone = Τόνος (Tonos)

- Tragedy = Τραγωδία (Tragodia)

- Triumph = Θρίαμβος (Thriamvos)

- Type = Τύπος (Typos)

- Utopia = Ουτοπία (Utopeea)

- Zone = Ζώνη (Zonee)

- Zoo = Ζωο (Zoo)

- Zoology = Ζωολογία (Zoologia)

Also, almost all words that start with “PH” are of Greek origin!

We must stop here, these are already very good samples, and is impossible to write down all the 150,000 Greek words used in English! But if you click this Wiktionary link you can discover thousands more Greek words in English than you ever imagined.

So, If you are one of those who say “It’s all Greek to me” it’s time to reconsider it, it will help if you follow a couple of simple tips.

Most important, the Latin sound of “C” is “K” in Greek. For Greeks, the sound of “C” is written and pronounced always as “S”.

Keep in mind that the “TH” sound is written with the letter “Θ” in Greek.

The ancient Greek B originally sounded like what B sounds like in English today, but in modern Greek, it is written with “MΠ” (M+P), and the letter “Β” sounds like “V”.

All ancient Greek words that start with the “H” sound, History, for instance, were written with aspiration in the first letter, this aspirate remained in English but was replaced with the letter ‘H’.

This aspiration is abolished in modern Greek and the sound of “H” is not pronounced.

Anywhere you see an “Ω” or “Ο” both pronounced as “O”. There are some more minor differences, but slowly you will find out that you start to make sense.

Differences in the alphabets are minor, the Latin alphabet, after all, is the natural evolution of the Greek Euboean alphabet which in turn is a transformation of the Phoenician alphabet with the additions of vowels.

Finally, you will see that saying “is all Greek to me” is a non-sense expression, therefore for something completely unknown it’s more appropriate to say “it’s all Chinese to me“.

After all, the so-called Indo-European languages have something in common, the Phoenician alphabet which is the common ancestor for all alphabets in Europe.

They are all Hellenic(Greek)

According to one estimate, more than 150,000 words of English are derived from Greek words…source:www.britishcouncil.org

Now that you have seen how many Greek words you know, You shouldn’t feel stranger when you visit Greece, you are a native Greek-speaking person, you just don’t know it yet! Learn about this.

Learn 100 Greek words in 10 minutes!

.

English has borrowed many words from the ancient Greek language. Their spelling gives clues to their recognition and pronunciation

HISTORICAL INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH

English is essentially a North-Western European language related to German, Dutch and languages in Scandinavia. However, historical events have caused it to be greatly expanded by borrowings from other languages, especially those of Southern Europe.

French has been a particular influence as a result of Britain being ruled by French-speaking monarchs for about 300 years after 1066 (see 135. French Influences on English Vocabulary). Latin, the language of the ancient Romans, is the ancestor of French, and hence had a great impact on English through it. Later, however, as scholarship advanced, English borrowed more and more words directly from Latin in order to name developing new concepts. More about the influence of Latin on English is in the posts 45. Latin Clues to English Spelling and 130. Formal Abbreviations. Many scholarly words were also borrowed from the language of Ancient Greece. Finally, the growth of Britain as an imperial power caused it to adopt many other new words from right across the world.

The language of Ancient Greece has had almost as important an impact on English as Latin. This is because the Ancient Greeks were the foremost European thinkers before Latin was spread across the continent by the Romans. Words from their language entered English not only directly as names for modern ideas and inventions, but also via Latin, since the Romans themselves used many Ancient Greek words in their learned writings (e.g. philosophia, the Greek word for philosophy).

.

HOW TO RECOGNISE ENGLISH WORDS OF GREEK ORIGIN

Being able to recognise that a word is of Greek origin can help you to spell and pronounce it correctly. This is because these aspects follow fairly reliable rules. Indeed, words of Greek origin very rarely have illogical features of the kind discussed in 29. Illogical Vowel Spellings; and 188. Causes of Common Spelling Mistakes; they only seem a problem because their spelling is often quite unusual.

The main clues that a word is of Greek origin are the following:

.

1. Special Letter Combinations

Many of these involve the letter “p”. It combines with “h” in words like philosophy, phrase, sphere, emphasis, graph, nymph, symphony and aphrodisiac. In addition, there are “ps” combinations – most disconcertingly at the start of words (psychology, psalm, pseudonym), but also in the middle (rhapsody) – and also “pn” and “pt”, mostly at the beginning of words (pneumatic, pneumonia, pterodactyl, helicopter, symptom).

The letter “y” used as a vowel is also a good clue to a Greek origin, though it is not entirely reliable. It is not Greek at the end of adjectives (happy, easy, ready) and many nouns (discovery, itinerary) and in the -ly and -fy endings, nor in short words like my, why, shy and sky. Words where it is of Greek origin are abyss, analyse, psychology, hypocrite, hypnotise, pyramid, hyperactive, mystery, rhythm, syndrome, syringe, cycle and cyst.

The “ch” spelling is also variably indicative of a Greek origin. It is Greek in anarchy, anchor, character, chiropody, choir, cholesterol, chorus, Christmas, chrome, epoch, orchestra, psychology and scheme; but it is not Greek in chicken, church, chain, change, chief, chimney, lychee, fetch and inch.

Many words with “th” come from Greek, e.g. mathematics, theme, thesis, theatre, thermal, ethics, myth, sympathise and labyrinth. Finally, the combination “rh” is highly indicative of a Greek origin. It exists in words like rheumatism, diarrhoea, rhythm, rhapsody and rhetoric.

.

2. Greek Word Endings

The Guinlist post 12. Singular and Plural Verb Choices states that most nouns become plural by adding -s to their singular form, but not all do. Two of the exceptional categories are nouns of Greek origin whose singular forms end in either -on or -is – words like automaton, criterion, phenomenon, oasis, diagnosis, emphasis, thesis, hypothesis, parenthesis, synthesis, analysis, metamorphosis, axis and crisis. The -on ending becomes -a in the plural, the -is one -es (pronounced /i:z/). The underlined -is words are usable as “action” nouns – uncommon for words not of Latin origin (see 249. Action Noun Endings).

A common noun ending in Greek is -ma. These letters at the end of an English noun tend to indicate a Greek origin. Examples are cinema, coma, drama, enigma, magma, panorama, stigma and trauma. There are also some English words that have dropped the -a and just end with -m, e.g. axiom, phlegm, poem, problem, spasm, sperm, symptom and theme. The underlined words in both lists can be made into English adjectives ending -atic – another indicator of a Greek origin. Additional words with it include automatic, emphatic and rheumatic (but not the Latin-derived erratic).

Many other adjectives with -ic show a Greek origin. Common ones are analytic, archaic, comic, cosmic, economic, fantastic, gastric, graphic, historic, histrionic, ironic, manic, panoramic, pathetic, periodic, photographic, poetic, politic, scenic, strategic, synthetic and tragic. Going against this trend, though, are quite a few -ic adjectives of Latin rather than Greek origin, for example civic, frantic, linguistic, prolific, specific, terrific and Teutonic.

In addition to adjectives, -ic is found on many nouns of Greek origin. Examples include antic, comic, critic, graphic, ethic, heretic, logic, mimic, music, mystic, rhetoric, statistic, synthetic, tactic and topic. For more on how a single ending can show different word classes, see 172. Multi-Word Suffixes.

Another adjective ending that commonly shows a Greek origin is -ical. It makes adjectives out of nouns ending in -ology, e.g. biological, psychological and sociological, and out of some other nouns too, such as geographical, pharmaceutical, symmetrical, theatrical and typical. However, there are also some -ical words that are not of Greek origin, including farcical, medical and radical.

The -al ending, common on both nouns and adjectives in English, is not specific to words of Greek origin, but quite commonly makes adjectives out of Greek -ic words. Examples are comical, critical, economical, ethical, graphical, heretical, historical, logical, mathematical, musical, mystical, political, rhetorical, statistical, tactical, topical.

The links in the above lists are to explanations of confusing pairs like economic/economical.

.

3. Greek Word Beginnings

The Guinlist post 45. Latin Clues to English Spelling points out that Latin prepositions are found at the beginning of many English words taken from Latin. The same is true of Greek prepositions. Common ones are ana-, anti-, apo-, dia-, en-/em-, epi-, hypo, hyper-, meta-, para-, peri-, pro- and syn-/sym-. Recognising any of these at the beginning of a word can greatly help its identification as Greek.

Examples of words starting with a Greek preposition are analysis, anatomy, antithesis, antonym, apology, apostle, diabetes, dialogue, emblem, empathy, epoch, epistle, epitome, hypodermic, hypothesis, hyperbole, metabolism, metaphor, paradox, paralyse, parallel, paraphrase, perimeter, period, problem, prophylaxis, symbol, synonym and synchronise. The word hyphen (representing a punctuation type considered in depth in this blog in 223. Uses of Hyphens) begins with a modified form of hypo. Parenthesis combines para- (= beside) and -en- (= inside) with -thesis (= placement) (see 294. Parentheses).

Sometimes the rest of a word after a Greek preposition is itself a possible English word, so that the preposition is acting like a true prefix (see 146. Some Important Prefix Types). Examples are para-medic and hyper-inflation. Some other English prefixes are also of Greek origin, for example auto- (= “self-“), pseudo- (= “pretending”) and a- (= “not”). Words with the latter include amorphous, apathetic, apolitical, asexual, atheist and atypical (but not Latin-derived abnormal).

.

4. Medical Terms

Medicine is an area where Greek words are especially abundant. Examples are anatomy, antigen, artery, bacteria, cholesterol, dermatology, diarrhoea, gene, larynx, microscope, neurosis, oesophagus, parasite, pathology, physiology, rhesus, sclerosis, syndrome, syringe, thermometer and thrombosis.

The -osis ending (sometimes spelt -asis) means “present and troublesome” and is used to describe a wide range of illnesses (thrombosis for example is the presence of a troublesome blood clot). -osis can even be combined with a non-Greek root, as in tubercul-osis.

.

PRONUNCIATION OF GREEK WORDS IN ENGLISH

It is generally well-known that the combination ph- is usually pronounced /f/. The letter “p” in other combinations (pn-, ps- and pt-) is silent at the start of a word (see 155. Silent Consonants) but in other positions is pronounced normally. Pseudonym, for example, begins with /s/, pneumonia with /n/.

The pronunciation of “ch” is usually /k/. Here is where it is important to know whether or not the word is originally Greek, since “ch” in non-Greek words is /t∫/. All of the “ch” words listed above follow this tendency. An exception, though, is arch – pronounced with /t∫/ despite a Greek origin.

Another useful guideline, also mentioned in the post 86. The Pronunciation of “e” and “i”, is that the letter “i” in the Greek prefixes dia-, bio- and micro- is pronounced /aı/ not /ı/. Examples are diabetes, diagonal, diameter, diarrhoea, biology, biopic, biopsy, microbe, microeconomics, micrometer and microscope.

One problem that is unfortunately not so easy to solve is deciding whether to pronounce “y” as /ı/ or /aı/. The former seems more common, occurring for example in analytic, anarchy, cyclic, cyst, embryo, gymnasium, hymn, hypnotise, mystery, physics, pyramid, rhythm, syllable, syringe, system and words beginning with syn-; the latter is exemplified in analyse, cycle, encyclopaedia, gynaecology, paralyse, phylum, psychology, style, tyrant and the prefixes hypo- and hyper-.

Finally, in words of Greek origin the letter “e” at the end does not always make the vowel before it long (as in words like fade, hope, site, use and paralyse), but can instead make a separate syllable (pronounced /ı/). This happens in words like anemo-ne, epito-me, hyperbo-le, synco-pe and the girls’ names Hermio-ne and Daph-ne. The word simi-le, which also has this feature, is of Latin rather than Greek origin.