A. Lexical

Meaning

every

word (lexical unit) has . . . something that is individual, that makes it

different from any other word. And it is just the lexical meaning which is

the most outstanding individual property of the word. (Zgusta, 1971:67)

The

lexical meaning of a word or lexical unit may be thought of as the specific

value it has in a particular linguistic system and the ‘personality’ it acquires through usage within that system. It

is rarely possible to analyse a word, pattern, or structure into distinct

components of meaning; the way in which language works is much too complex to

allow that. Nevertheless, it is sometimes useful to play down the complexities

of language temporarily in order both to appreciate them and to be able to

handle them better in the long run. With

this aim in mind, we will now briefly discuss a model for analysing the

components of lexical meaning. This model is largely derived from Cruse (1986),

but the description of register (2.2.3 below) also draws on Halliday

(1978). For alternative models of lexical meaning see Zgusta

(1971: Chapter 1) and Leech (1974:

Chapter 2).

2.2.1. Propositional vs expressive meaning

The propositional

meaning of a word or an utterance arises from the relation

between it and what it refers to or

describes in a real or imaginary world, as conceived by the speakers of the

particular language to which the word or utterance belongs. It is this type of

meaning which provides the basis on which we can judge an utterance as true or

false. For instance, the propositional meaning of shirt is ‘a piece of

clothing worn on the upper part of the body’. It would be inaccurate to use shirt,

under normal circumstances,to refer to a piece of clothing worn on the

foot, such as socks. When a translation is described as ‘inaccurate’, it

is often the propositional meaningthat is being called into question.

Expressive

meaning cannot be judged as true or false. This is because expressive

meaning relates to the speaker’s2 feelings or attitude rather thanto what words

and utterances refer to. The difference between Don’t complain and Don’t

whinge does not lie in their propositional meanings but in the expressiveness

of whinge, which suggests that the speaker finds the actionannoying. Two

or more words or utterances can therefore have the samepropositional meaning

but differ in their expressive meanings. This is true not only of words and

utterances within the same language, where such words are often referred to as

synonyms or near-synonyms, but also for words

and utterances from different

languages. The difference between famous in English and fameux in

French does not lie in their respective propositional meanings; both items basically

mean ‘well-known’. It lies in their expressive meanings. Famous is

neutral in English: it has no inherent evaluative meaning or connotation. Fameux,

on the other hand, is potentially evaluative and can be readily used in

some contexts in a derogatory way (for example, une femme fameuse means,

roughly, ‘a woman of ill repute’). It is worth noting that differences between

words in the area of expressive

meaning are not simply a matter of

whether an expression of a certain attitude or evaluation is inherently present

or absent in the words in question. The same attitude or evaluation may be

expressed in two words or utterances in widely differing degrees of

forcefulness. Both unkind and cruel, for instance, are inherently

expressive, showing the speaker’s disapproval of someone’s attitude. However, the element of disapproval

in cruel is stronger than it is in unkind. The meaning of a word

or lexical unit can be both propositional and expressive, e.g. whinge, propositional

only, e.g. book, or expressive only, e.g. bloody and various

other swear words and emphasizers. Words which contribute solely to expressive

meaning can be removed from an utterance without affecting its information

content. Consider, for instance, the wordsimply in the following text:

2.2.2 Presupposed

meaning

Presupposed

meaning arises from co-occurrence restrictions, i.e. restrictions

on what other words or expressions

we expect to see before or after a particular lexical unit. These restrictions

are of two types:

1. Selectional restrictions: these

are a function of the propositional meaning of a word. We expect a human

subject for the adjective studious and an inanimate one for geometrical.

Selectional restrictions are deliberately violated in the case of

figurative language but are otherwise strictly observed.

2. Collocational restrictions: these

are semantically arbitrary restrictions which do not follow logically from the

propositional meaning of a word. For instance, laws are broken in

English, but in Arabic they are ‘contradicted’. In English, teeth are brushed,

but in German and Italian they are ‘polished’, in Polish they are ‘washed’,

and in Russian they are ‘cleaned’. Because they are arbitrary, collocational

restrictions tend to show more variation across languages than do selectional

restrictions.

The

difference between selectional and collocational restrictions is not always

as clear cut as the examples given

above might imply. For example, in the following English translation of a

German leaflet which accompanies Baumler products (men’s suits), it is

difficult to decide whether the awkwardness of the wording is a result of

violating selectional or collocational restrictions:

Dear Sir

I am very pleased that you have

selected one of our garments. You have made a wise choice, as suits, jackets

and trousers eminating from our Company are amongst the finest products Europe

has to offer.

Ideas, qualities, and feelings

typically emanate (misspelt as eminate in the above text) from a

source, but objects such as trousers and jackets do not, at least

not in English. The awkwardness of the wording can be explained in terms of

selectional or collocational restrictions, depending on whether or not one sees

the restriction involved as a function of the prepositional meaning of emanate.

3. Evoked meaning

Evoked

meaning arises from dialect and register variation. A dialect is

a variety of language which has currency within a specific community or

group of speakers. It may be classified on one of the following bases:

1. Geographical (e.g. a Scottish

dialect, or American as opposed to British English: cf. the difference between lift

and elevator);

2. Temporal (e.g. words and

structures used by members of different age groups within a community, or words

used at different periods in the history of a language: cf. verily and really);

3. Social (words and structures used

by members of different social classes: cf. scent and perfume, napkin

and serviette).

Register is a variety of language that a language user considers appropriate

to a specific situation. Register

variation arises from variations in the

following:

1. Field of

discourse: This is an abstract term for ‘what is going on’ that is

relevant to the speaker’s choice of linguistic items. Different

linguistic choices are made by different speakers depending on what kind of

action other than the immediate action of speaking they see themselves as participating

in. For example, linguistic choices will vary according to whether the speaker

is taking part in a football match or discussing football;

making love or discussing love;

making a political speech or discussing politics; performing an operation or

discussing medicine.

2. Tenor of

discourse: An abstract term for the relationships between the

people

taking part in the discourse. Again, the language people use varies depending

on such interpersonal relationships as mother/ child, doctor/ patient, or

superior/inferior in status. A patient is unlikely to use swear words in

addressing a doctor and a mother is unlikely to start a request to her child

with I wonder if you could . . . Getting the tenor of discourse right in

translation can be quite difficult. It depends on whether one sees a certain

level of formality as ‘right’ from the perspective of the source culture or the

target culture. For example, an American teenager may adopt a highly informal

tenor with his/her parents by, among other things, using their first names

instead of Mum/Mother and Dad/Father. This level of informality

would be highly inappropriate in most other cultures.

3. Mode of

discourse: An abstract term for the role that the language is playing

(speech, essay, lecture, instructions) and for its medium of transmission

(spoken, written).3 Linguistic choices are influenced by these dimensions. For example, a word such as re

is perfectly appropriate in a business letter but is rarely, if ever, used

in spoken English.

B. THE

PROBLEM OF NON-EQUIVALENCE

Based

on the above discussion, we can now begin to outline some of the more common

types of non-equivalence which often pose difficulties for the translator and

some attested strategies for dealing with them. First, a word of warning. The

choice of a suitable equivalent in a given context depends on a wide variety of

factors. Some of these factors may be strictly linguistic. Other factors may be

extra-linguistic. It is virtually impossible to offer absolute guidelines for

dealing with the various types of nonequivalence which exist among languages.

The most that can be done in this and the following chapters is to suggest

strategies which may be used to dealwith non equivalence ‘in some contexts’.

The choice of a suitable equivalent will always depend not only on the

linguistic system or systems being handled by the translator, but also on the

way both the writer of the source text and the producer of the target text,

i.e. the translator, choose to manipulate the linguistic systems in question.

2.3.1 Semantic

fields and lexical sets – the segmentation of experience

The

words of a language often reflect not so much the reality of the world,

but the interests of the people who

speak it. (Palmer, 1976: 21) It is sometimes useful to view the vocabulary of a

language as a set of words referring to a series of conceptual fields. These

fields reflect the divisions and sub-divisions ‘imposed’ by a given linguistic

community on the continuum of experience.4 In linguistics, the divisions are

called semantic fields. Fields are abstract concepts. An example

of a semantic field would be the field of SPEECH, or PLANTS, or VEHICLES. A large

number of semantic fields are common to all or most languages. Most, if not

all, languages will have fields of DISTANCE, SIZE, SHAPE, TIME, EMOTION,

BELIEFS, ACADEMIC SUBJECTS, and NATURAL PHENOMENA. The actual words and

expressions under each field are sometimes called lexical sets.5 Each

semantic field will normally have several sub-divisions or lexical sets under

it, and each subdivision will have further sub-divisions and lexical sets. So,

the field of SPEECH in English has a sub-division of VERBS OF SPEECH which

includes general verbs such as speak and say and more specific

ones such as mumble, murmur, mutter, and whisper. It seems

reasonable to suggest that the more detailed a semantic field is in a given

language, the more different it is likely

to be from related semantic fields

in other languages. There generally tends to be more agreement among languages

on the larger headings of semantic fields and less agreement as the sub-fields

become more finely differentiated. Most languages are likely to have

equivalents for the more general verbs of speech such as say and speak,

but many may not have equivalents for the more specific ones. Languages

understandably tend to make only those distinctions in meaning which are

relevant to their particular environment, be it physical, historical,

political, religious, cultural, economic, legal, technological, social, or

otherwise.

Limitations aside, there are two

main areas in which an understanding of semantic fields and lexical sets can be

useful to a translator:

a. appreciating the ‘value’ that a

word has in a given system; and

b. developing strategies for dealing

with non-equivalence.

(a) Understanding the difference in

the structure of semantic fields in the source and target languages allows a

translator to assess the value of a given item in a lexical set. If you know

what other items are available in a lexical set and how they contrast with the

item chosen by a writer or speaker, you can appreciate the significance of the

writer’s or speaker’s choice. You can understand not only what something is,

but also what it is not. This is best illustrated by an example.

In

the field of TEMPERATURE, English has four main divisions: cold, cool, hot and

warm. This contrasts with Modern Arabic, which has four different divisions:

baarid (‘cold/cool’), haar (‘hot: of the weather’), saakhin (‘hot:

of objects’), and daafi’ (‘warm’). Note that, in contrast with

English, Arabic (a) does not distinguish between cold and cool,

and (b) distinguishes between the hotness of the weather and the

hotness of other things. The fact that English does not make the latter

distinction does not mean that you can always use hot to describe

the temperature of something, even metaphorically (cf. hot temper, but

not * hot feelings). There are restrictions on the cooccurrence

of words in any language (see discussion of collocation: Chapter 3,

section 3.1). Now consider the following examples from the COBUILD corpus

of English:6

1. The air was cold and the wind was

like a flat blade of ice.

2. Outside the air was still cool.

Bearing in mind the differences in

the structure of the English and Arabic fields, one can appreciate, on the one

hand, the difference in meaning between cold and cool in the

above examples and, on the other, the potential difficulty in making such a

distinction clear when translating into Arabic.

(b) Semantic fields are arranged

hierarchically, going from the more general

to

the more specific. The general word is usually referred to as superordinate

and the specific word as hyponym.

In the field of VEHICLES, vehicle is a superordinate and bus,

car, truck, coach, etc. are all hyponyms of vehicle. It stands to

reason that any propositional meaning carried by a superordinate or general

word is, by necessity, part of the meaning of each of its hyponyms, but not

vice versa. If something is a bus, then it must be a vehicle, but not the other

way round. We can sometimes manipulate this feature of semantic fields when we

are faced with semantic gaps in the target language. Translators often deal

with semantic gaps by modifying a superordinate word or by means of

circumlocutions based on modifying superordinates. More on this in the

following section.

2.3.2

Non-equivalence at word level and some common strategies for

dealing with it

Non-equivalence

at word level means that the target language has no direct equivalent for a

word which occurs in the source text. The type and level of difficulty posed

can vary tremendously depending on the nature of nonequivalence. Different

kinds of non-equivalence require different strategies, some very

straightforward, others more involved and difficult to handle. Since, in

addition to the nature of non-equivalence, the context and purpose of

translation will often rule out some strategies and favour others, I will keep

the discussion of types of non-equivalence separate from the discussion of

strategies used by professional translators. It is neither possible nor helpful

to attempt to relate specific types of non-equivalence to specific strategies, but

I will comment on the advantages or disadvantages of certain strategies wherever

possible

.

2.3.2.1 Common

problems of non-equivalence

The

following are some common types of non-equivalence at word level, with examples

from various languages

:

(a) Culture-specific concepts

The

source-language word may express a concept which is totally unknown in the

target culture. The concept in question may be abstract or concrete; it may

relate to a religious belief, a social custom, or even a type of food. Such concepts

are often referred to as ‘culture-specific’. An example of an abstract English

concept which is notoriously difficult to translate into other languages is

that expressed by the word privacy. This is a very ‘English’ concept

which is rarely understood by people from other cultures. Speaker (of

the House of Commons) has no equivalent in many languages, such as Russian,

Chinese, and Arabic among others. It is often translated into Russian as

‘Chairman’, which does not reflect the role of the Speaker of the House of Commons

as an independent person who maintains authority and order in

Parliament. An example of a concrete

concept is airing cupboard in Englishwhich, again, is unknown to

speakers of most languages.

(b) The source-language concept is

not lexicalized in the target language

The source-language word may express

a concept which is known in the target culture but simply not lexicalized, that

is not ‘allocated’ a targetlanguage word to express it. The word savoury has

no equivalent in many languages, although it expresses a concept which is easy

to understand. The adjective standard (meaning ‘ordinary, not extra’, as

in standard range of products) also expresses a concept which is

very accessible and readily understood by most people, yet Arabic has no

equivalent for it. Landslide has no ready equivalent in many languages,

although it simply means overwhelming majority’.

(c) The source-language word is semantically

complex

The

source-language word may be semantically complex. This is a fairly common

problem in translation. Words do not have to be morphologically complex to be

semantically complex (Bolinger and Sears, 1968). In otherwords, a single word

which consists of a single morpheme can sometimes express a more complex set of

meanings than a whole sentence. Languages automatically develop very concise

forms for referring to complex concepts if the concepts become important enough

to be talked about often. Bolinger and Sears suggest that ‘If we should ever

need to talk regularly and frequentlyabout independently operated sawmills from

which striking workers are locked out on Thursday when the temperature is

between 500° and 600°F, we would find a concise way to do it’ (ibid.: 114). We

do not usually realize

how semantically complex a word is

until we have to translate it into a language which does not have an equivalent

for it. An example of such a semantically complex word is arruação, a

Brazilian word which means clearing the ground under coffee trees of rubbish

and piling it in the middle of the row in order to aid in the recovery of beans

dropped during harvesting’ (ITI News, 1988: 57).7

(d) The source and target languages

make different distinctions in meaning

The

target language may make more or fewer distinctions in meaning than the source

language. What one language regards as an important distinction in meaning

another language may not perceive as relevant. For example, Indonesian makes a

distinction between going out in the rain without the knowledge that it is raining

(kehujanan) and going out in the rain with the knowledge that it is

raining (hujan-hujanan). English does not make this distinction, with

the result that if an English text referred to going out in the rain, the

Indonesian translator may find it difficult to choose the right

equivalent, unless the context makes

it clear whether zor not the person in question

knew that it was raining.

(e)

The target language lacks a superordinate

The

target language may have specific words (hyponyms) but no general word

(superordinate) to head the semantic field. Russian has no ready equivalent for

facilities, meaning ‘any equipment, building, services, etc. that are

provided for a particular activity or purpose’.8 It does, however, have several

specific words and expressions which can be thought of as types of facilities,

for example sredstva peredvizheniya (‘means of transport’), naem

(‘loan’), neobkhodimye pomeschcheniya (‘essential accommodation’), and neobkhodimoe

oborudovanie (‘essential equipment’).

f)

The target language lacks a specific term (hyponym)

More commonly,

languages tend to have general words (superordinates) but lack specific ones

(hyponyms), since each language makes only those distinctions in meaning which

seem relevant to its particular environment.

There are

endless examples of this type of non-equivalence. English has many hyponyms

under article for which it is difficult to find precise equivalents in other

languages, for example feature, survey, report, critique, commentary,

review, and many more. Under house, English again has a variety of

hyponyms which have no equivalents in many languages, for example bungalow,

cottage, croft, chalet, lodge, hut, mansion, manor, villa, and hall. Under

jump we find more specific verbs such as leap, vault, spring, bounce,

dive, clear, plunge, and plummet.

g)

Differences in physical or interpersonal perspective

Physical

perspective has to do with where things or people are in relation to one

another or to a place, as expressed in pairs of words such as come/go,

take/bring, arrive/depart, and so on. Perspective may also include the

relationship between participants in the discourse (tenor). For example,

Japanese has six equivalents for give, depending on who gives to whom: yaru,

ageru, morau, kureru, itadaku, and kudasaru (McCreary, 1986).

h)

Differences in expressive meaning

There may be a

target-language word which has the same propositional meaning as the

source-language word, but it may have a different expressive meaning. The

difference may be considerable or it may be subtle but important enough to pose

a translation problem in a given context. It is usually easier to add

expressive meaning than to subtract it. In other words, if the target-language

equivalent is neutral compared to the source-language item, the translator can

sometimes add the evaluative element by means of a modifier or adverb if

necessary, or by building it in somewhere else in the text. So, it may be possible,

for instance, in some contexts to render the English verb batter (as in

child/wife battering) by the more neutral Japanese verb tataku, meaning

‘to beat’, plus an equivalent modifier such as ‘savagely’ or ‘ruthlessly’.

Differences in expressive meaning are usually more difficult to handle when the

target-language equivalent is more emotionally loaded than the source-language

item. This is often the case with items which relate to sensitive issues such

as religion, politics, and sex. Words like homosexuality and homosexual

provide good examples. Homosexuality is not an inherently pejorative

word in English, although it is often used in this way. On the other hand, the

equivalent expression in Arabic, shithuth jinsi (literally: ‘sexual

perversion’), is inherently more pejorative and would be quite difficult to use

in a neutral context without suggesting strong disapproval.

i)

Differences in form

There is often

no equivalent in the target language for a particular form in the source text.

Certain suffixes and prefixes which convey propositional and other types of

meaning in English often have no direct equivalents in other languages. English

has many couplets such as employer/employee, trainer/trainee, and payer/payee.

It also makes frequent use of suffixes such as -ish (e.g. boyish,

hellish, greenish) and -able (e.g. conceivable, retrievable,

drinkable). Arabic, for instance, has no ready mechanism for producing such

forms and so they are often replaced by an appropriate paraphrase, depending on

the meaning they convey (e.g. retrievable as ‘can be retrieved’ and drinkable

as ‘suitable for drinking’). Affixes which contribute to evoked meaning,

for instance by creating buzz words such as washateria, carpeteria, and groceteria

(Bolinger and Sears, 1968), and those which convey expressive meaning, such

as journalese, translationese, and legalese (the -ese suffix

usually suggests disapproval of a muddled or stilted form of writing) are more

difficult to translate by means of a paraphrase. It is relatively easy to

paraphrase propositional meaning, but other types of meaning cannot always be

spelt out in a translation. Their subtle contribution to the overall meaning of

the text is either lost altogether or recovered elsewhere by means of

compensatory techniques.

j)

Differences in frequency and purpose of using specific forms

Even when a

particular form does have a ready equivalent in the target language, there may

be a difference in the frequency with which it is used or the purpose for which

it is used. English, for instance, uses the continuous — ing form for

binding clauses much more frequently than other languages which have

equivalents for it, for example German and the Scandinavian languages.

Consequently, rendering every -ing form in an English source text with

an equivalent -ing form in a German, Danish, or Swedish target text

would result in stilted, unnatural style.

k)

The use of loan words in the source text

The use of loan words in the source text poses a special

problem in translation. Quite apart from their respective prepositional

meaning, loan words such as au fait, chic, and alfresco in

English are often used for their prestige value, because they can add an air of

sophistication to the text or its subject matter. This is often lost in

translation because it is not always possible to find a loan word with the same

meaning in the target language. Dilettante is a loan word in English,

Russian, and Japanese; but Arabic has no equivalent loan word. This means that

only the prepositional meaning of dilettante can be rendered into

Arabic; its stylistic effect would almost certainly have to be sacrificed.

The above are some of the more common examples of non-equivalence

among languages and the problems they pose for translators. In dealing with any

kind of non-equivalence, it is important first of all to assess its

significance and implications in a given context. Not every instance of

non-equivalence you encounter is going to be significant. It is neither

possible nor desirable to reproduce every aspect of meaning for every word in a

source text. We have to try, as much as possible, to convey the meaning of key

words which are focal to the understanding and development of a text, but we

cannot and should not distract the reader by looking at every word in isolation

and attempting to present him/her with a full linguistic account of its

meaning.

STRATEGIES USED BY PROFESSIONAL TRANSLATORS

With the above proviso in mind, we can now

look at examples of strategies used by professional translators

for dealing with various types of nonequivalence. In each example,

the source-language word which represents a translation problem is

underlined. The strategy used by the translator is highlighted in

bold in both the original translation and the back-translated version.

Only the strategies used for dealing with non-equivalence at word level

will be commented on. Other strategies and differences between the source

and target texts are dealt with in subsequent chapters.

a)

Translation by a more

general word (superordinate)

This is one of

the commonest strategies for dealing with many types of nonequivalence,

particularly in the area of propositional meaning. It works equally well in

most, if not all, languages, since the hierarchical structure of semantic

fields is not language-specific.

Example D

Source text (China’s Panda Reserves; see Appendix 3, no. 3):

Today there may be no more than 1000 giant

pandas left in the wild, restricted to a few mountain strongholds in the

Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu.

Target text (back-translated from Chinese):

Today there may be only 1000 big pandas which still remain in the wild

state, restricted to certain mountain areas in China’s Sichuan, Shaanxi

and Gansu.

What the translators of the above extracts have done is to go up a

level in a given semantic field to find a more general word that covers the

core propositional meaning of the missing hyponym in the target language.

(b) Translation by a more neutral/less expressive word

Example

A

Source text: (Morgan Matroc – ceramics company brochure; see Appendix 2):

Today people are aware that modern ceramic materials offer unrivalled

properties for many of our most demanding industrial applications. So is this

brochure necessary; isn’t the ceramic market already overbombarded with

technical literature; why should Matroc add more?

Because someone mumbles, ‘Our competitors do it.’ But why should we

imitate our competitors when Matroc probably supplies a greater range of

ceramic materials for more applications than any other manufacturer.

Target text: (Italian):

Qualcuno suggerisce: ‘i nostri concorrenti lo fanno.’

Someone suggests: ‘Our competitors do it.’

There is a noticeable difference in the expressive meaning of mumble

and its nearest Italian equivalent, mugugnare. The English verb mumble

suggest confusion or embarrassment, as can be seen in the following

examples:9

Simon mumbled confusedly: ‘I don’t believe in

the beast.’

I looked at the ground, shuffled my feet and

mumbled something defensive.

‘I know it wasn’t very successful,’ he

mumbled. ‘But give me another

chance.’

The Italian near equivalent, mugugnare, on the other hand,

tends to suggest dissatisfaction rather than embarrassment or confusion.

Possibly to avoid conveying the wrong expressive meaning, the Italian

translator opted for a more general word, suggerisce (‘suggest’).

(c) Translation by cultural substitution

This strategy involves replacing a culture-specific item or expression

with a target-language item which does not have the same propositional meaning

but is likely to have a similar impact on the target reader. The main advantage

of using this strategy is that it gives the reader a concept with which s/he

can identify, something familiar and appealing. On an individual level, the

translator’s decision to use this strategy will largely depend on (a) how much

licence is given to him/ her by those who commission the translation and (b) he

purpose of the translation. On a more general level, the decision will also

reflect, to some extent, the norms of translation prevailing in a given

community. Linguistic communities vary in the extent to which they tolerate

strategies that involve significant departure from the propositional meaning of

the text.

Example :

Source text (The Patrick Collection – a leaflet produced

by a privately owned museum of classic cars; see Appendix 4):

The Patrick Collection has restaurant facilities to suit every taste –

from the discerning gourmet, to the Cream Tea expert.

Target text

(Italian):

. . . di soddisfare tutti i gusti: da quelli del gastronomo esigente a

quelli

dell’esperto di pasticceria.

. . . to satisfy all tastes: from those of the demanding gastronomist

to

those of the expert in pastry.

In Britain, cream tea is ‘an afternoon meal consisting of tea to drink

and scones with jam and clotted cream to eat. It can also include sandwiches

and cakes.’12 Cream tea has no equivalent in other cultures. The Italian

translator replaced it with ‘pastry’, which does not have the same meaning (for

one thing, cream tea is a meal in Britain, whereas ‘pastry’ is only a type of

food). However, ‘pastry’ is familiar to the Italian reader and therefore

provides a good cultural substitute.

This strategy involves replacing a

culture-specific item with a target language item which does not have the same

meaning but may have a similar [impact] influence on the receptor.

|

Source text |

Target text [Italian] |

|

The |

…………………….to |

In Britain, cream tea is “an afternoon meal” consisting of tea to

drink and scones with jam and clotted cream to eat. It can also include

sandwishes and cakes.

d. Translation by

using a loan word plus explanation

We use this strategy to deal with culture-specific items/ notions/concepts,

especially modern concepts.

|

Source text |

Target text [German] |

|

The |

…vom |

e. Translation by

paraphrase [ using a related / close word ]

The concept in the source text is lexicalized but the source text

is significantly higher than the natural target language

|

Source text |

Target text [ German ] |

|

Hot |

In |

f. Translation

by paraphrase [ using a unrelated word ]

The concept in the source text is not lexicalised in

the receptor text [ so this means there is no equivalent word / lexical unit]

à The

translator has to paraphrase by using unrelated words

|

Source text |

Target text [in German] |

|

You |

In |

à “alfresco”

and “in the open” have the same propositional meaning but different evoked meaning

|

Source text |

Target text [ in Arabic] |

|

They On |

The …………….with |

The main advantage of

the paraphrase strategy is that it achieves a high level of precision in

specifying propositional meaning.

g. Translation

by omision

This strategy may sound rather drastic, but

in fact it does no harm to omit translating a word expression in some context.

|

Source text |

Target text |

|

This |

Here |

h.

translation by illustration

This strategy to useful option if the word which

lacks an equivalent.

— Lipton Yellow Tea Packet in

Arab market as Tagged teabags

refrensi : Mona Baker, In other word

TYPES AND LEVELS OF EQUIVALENCE Lectures # 4-5 By Dr. Dmytro Tsolin

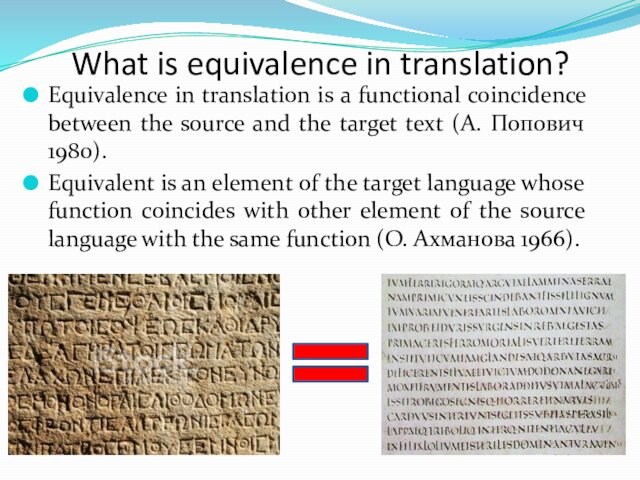

What is equivalence in translation? Equivalence in translation is a functional coincidence between the source and the target text (А. Попович 1980). Equivalent is an element of the target language whose function coincides with other element of the source language with the same function (О. Ахманова 1966).

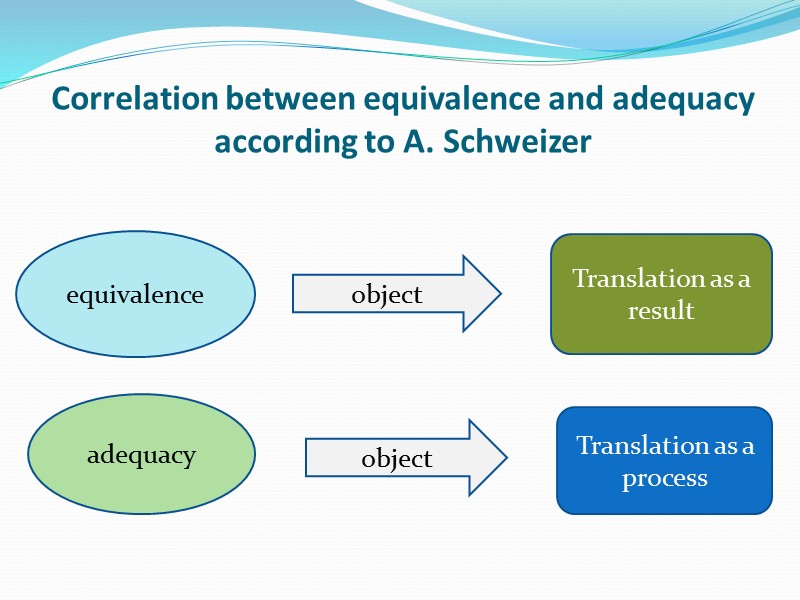

Equivalence and Adequacy Many scholars use these terms as synonyms (R. Levitsky, J. Catford). V. N. Komissarov considers “adequacy” as a characteristic of translation in general, while “equivalence” describes correlation between units of SL and TL. Adequacy as a kind of correlation between ST and TT which takes into account the aim of translation has been considered by K. Reiss and G. Vermeer. In translation equivalence is set not between word-signs as themselves, but between actual signs as segments of the text (A. Schweizer).

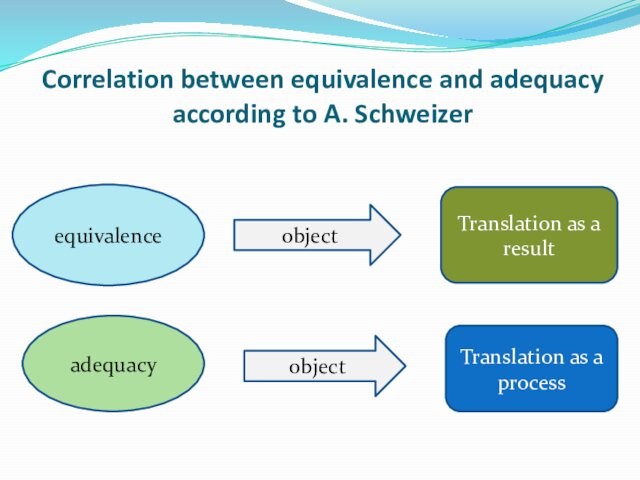

Correlation between equivalence and adequacy according to A. Schweizer equivalence adequacy object object Translation as a result Translation as a process

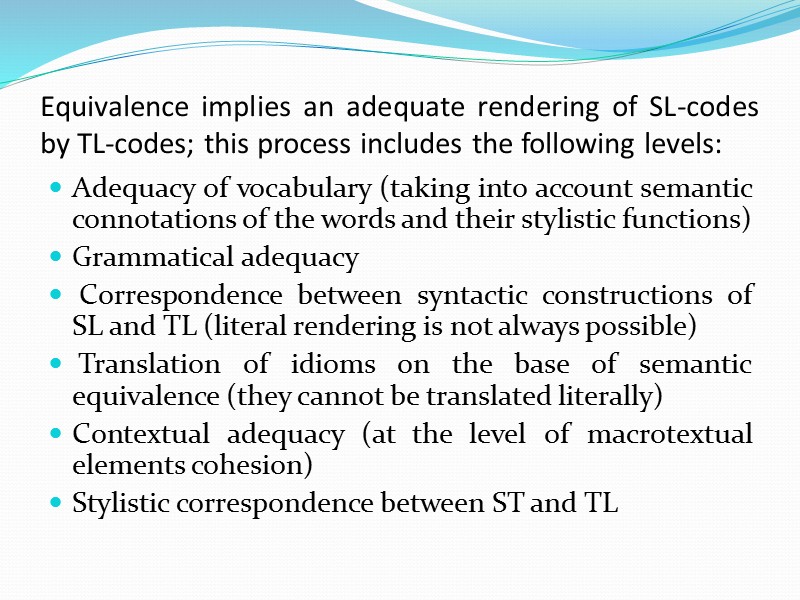

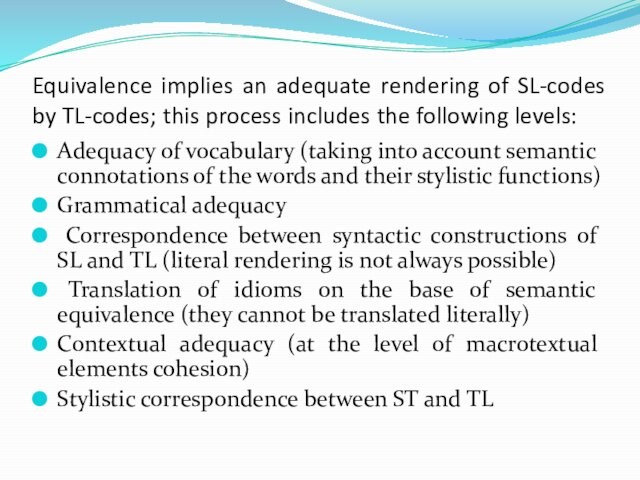

Equivalence implies an adequate rendering of SL-codes by TL-codes; this process includes the following levels: Adequacy of vocabulary (taking into account semantic connotations of the words and their stylistic functions) Grammatical adequacy Correspondence between syntactic constructions of SL and TL (literal rendering is not always possible) Translation of idioms on the base of semantic equivalence (they cannot be translated literally) Contextual adequacy (at the level of macrotextual elements cohesion) Stylistic correspondence between ST and TL

Equivalence of the text is more important than equivalence of it segments!!!

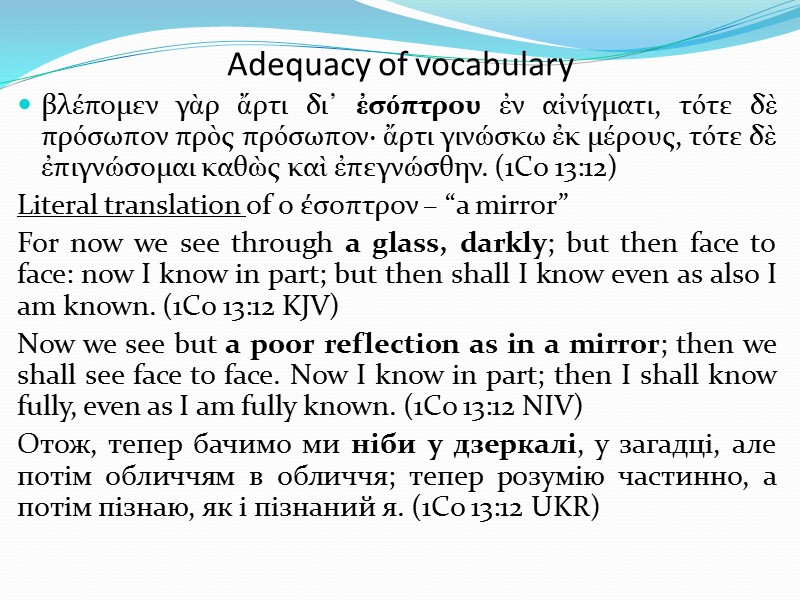

Adequacy of vocabulary βλέπομεν γὰρ ἄρτι δι᾽ ἐσόπτρου ἐν αἰνίγματι, τότε δὲ πρόσωπον πρὸς πρόσωπον· ἄρτι γινώσκω ἐκ μέρους, τότε δὲ ἐπιγνώσομαι καθὼς καὶ ἐπεγνώσθην. (1Co 13:12) Literal translation of ο έσοπτρον – “a mirror” For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (1Co 13:12 KJV) Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. (1Co 13:12 NIV) Отож, тепер бачимо ми ніби у дзеркалі, у загадці, але потім обличчям в обличчя; тепер розумію частинно, а потім пізнаю, як і пізнаний я. (1Co 13:12 UKR)

Ancient mirrors

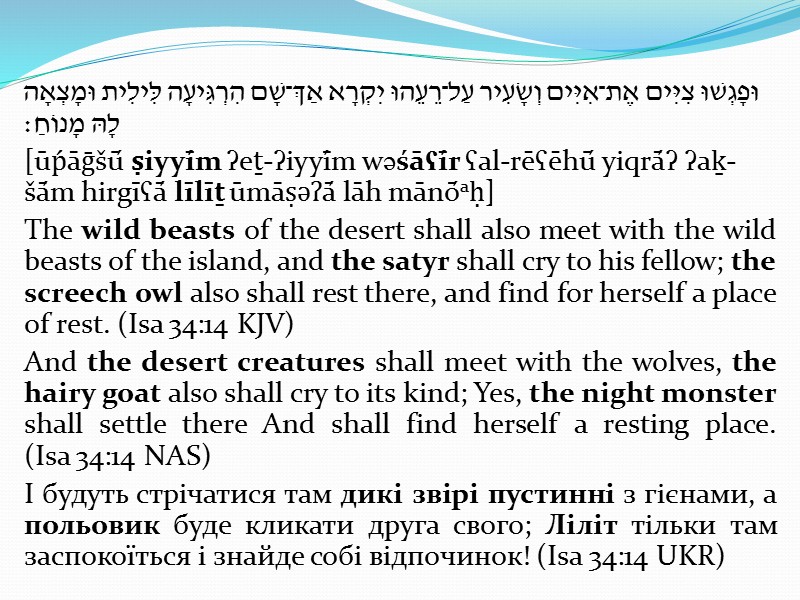

וּפָגְשׁוּ צִיִּים אֶת־אִיִּים וְשָׂעִיר עַל־רֵעֵהוּ יִקְרָא אַךְ־שָׁם הִרְגִּיעָה לִּילִית וּמָצְאָה לָהּ מָנוֹחַ׃ [ūṕāḡšū́ ṣiyyī́m ʔeṯ-ʔiyyī́m wəśāʕī́r ʕal-rēʕēhū́ yiqrā́ʔ ʔaḵ-šā́m hirgīʕā́ līlīṯ ūmāṣəʔā́ lāh mānṓaḥ] The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest. (Isa 34:14 KJV) And the desert creatures shall meet with the wolves, the hairy goat also shall cry to its kind; Yes, the night monster shall settle there And shall find herself a resting place. (Isa 34:14 NAS) І будуть стрічатися там дикі звірі пустинні з гієнами, а польовик буде кликати друга свого; Ліліт тільки там заспокоїться і знайде собі відпочинок! (Isa 34:14 UKR)

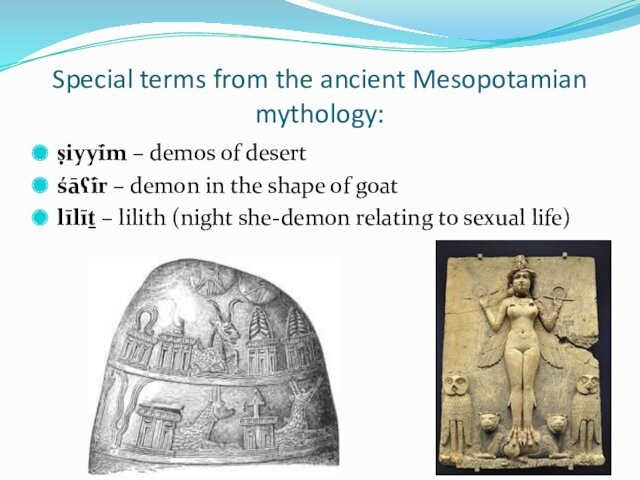

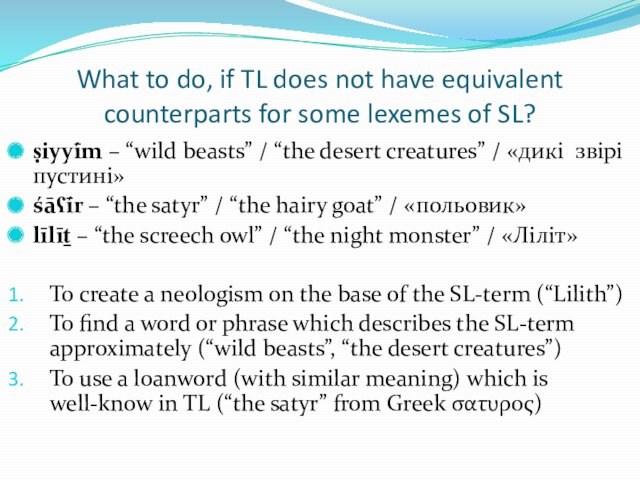

Special terms from the ancient Mesopotamian mythology: ṣiyyī́m – demos of desert śāʕī́r – demon in the shape of goat līlīṯ – lilith (night she-demon relating to sexual life)

What to do, if TL does not have equivalent counterparts for some lexemes of SL? ṣiyyī́m – “wild beasts” / “the desert creatures” / «дикі звірі пустині» śāʕī́r – “the satyr” / “the hairy goat” / «польовик» līlīṯ – “the screech owl” / “the night monster” / «Ліліт» To create a neologism on the base of the SL-term (“Lilith”) To find a word or phrase which describes the SL-term approximately (“wild beasts”, “the desert creatures”) To use a loanword (with similar meaning) which is well-know in TL (“the satyr” from Greek σατυρος)

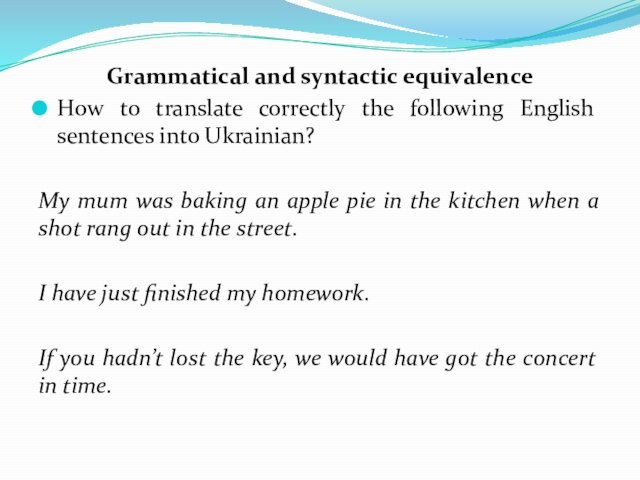

Grammatical and syntactic equivalence How to translate correctly the following English sentences into Ukrainian? My mum was baking an apple pie in the kitchen when a shot rang out in the street. I have just finished my homework. If you hadn’t lost the key, we would have got the concert in time.

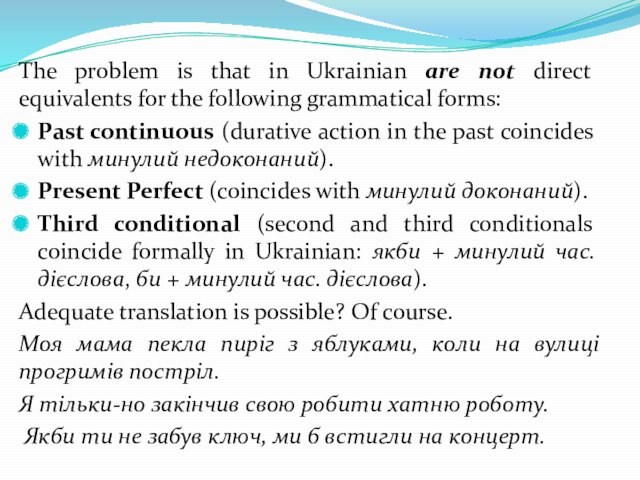

The problem is that in Ukrainian are not direct equivalents for the following grammatical forms: Past continuous (durative action in the past coincides with минулий недоконаний). Present Perfect (coincides with минулий доконаний). Third conditional (second and third conditionals coincide formally in Ukrainian: якби + минулий час. дієслова, би + минулий час. дієслова). Adequate translation is possible? Of course. Моя мама пекла пиріг з яблуками, коли на вулиці прогримів постріл. Я тільки-но закінчив свою робити хатню роботу. Якби ти не забув ключ, ми б встигли на концерт.

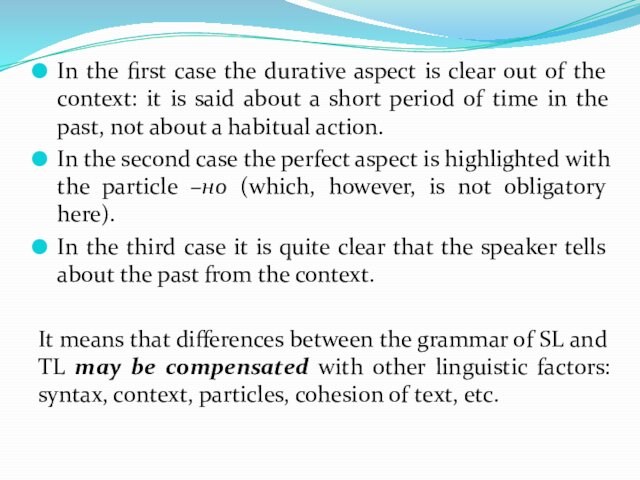

In the first case the durative aspect is clear out of the context: it is said about a short period of time in the past, not about a habitual action. In the second case the perfect aspect is highlighted with the particle –но (which, however, is not obligatory here). In the third case it is quite clear that the speaker tells about the past from the context. It means that differences between the grammar of SL and TL may be compensated with other linguistic factors: syntax, context, particles, cohesion of text, etc.

Contextual Adequacy Only limited number of words have one meaning, but most of them have several semantic variants which may be clarified from the context. Words with one meaning are mainly special terms or lexemes which designate specific items: allusion, organization, technology, methodology, dodder, dog-bee, etc. Words with many meanings prevail in any language: He received a special membership card and a club pin onto his lapel. One of them cleverly decorates a vase by drawing plant leaves using a sharp pin, while another shapes small frog-like figures to be put on ashtrays.

She was very nimble on her pins. A bolt from the blue. A great bolt of white lightning flashed out of thin air. Crossbow bolts and arrows passed like clouds across the face of the sun. The room is stacked with bolts of cloth. Those leaves which present a double or quadruple fold, technically termed «the bolt».

Translation of idioms: The captain held his peace that evening and for many evenings to come (R. Stevenson) Literal (mechanical) translation: Капітан тримав свій мир того вечора і протягом багатьох наступних вечорів. Correct translation: Капітан мовчав / тримав язик за зубами того вечора і протягом наступних вечорів. Miss Williams will look after you well because she knows the ropes (J. Aldridge) Literal translation: Міс Уільямс догляне тебе добре, бо вона знає мотузки. Correct translation: Міс Уільямс потурбується про тебе добре / належно, бо вона знає свою справу.

Her father kissed her when she left him with lips which she was sure had trembled. From the warmth of her embrace he probably divined that he had let the cat out of the bag (J. Galsworthy). Literal translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона покидала його, устами, про які вона була упевнена, що вони затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що випустив кота з мішка. Correct translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона йшла від нього, устами, які, здалося їй, затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що видав свої почуття.

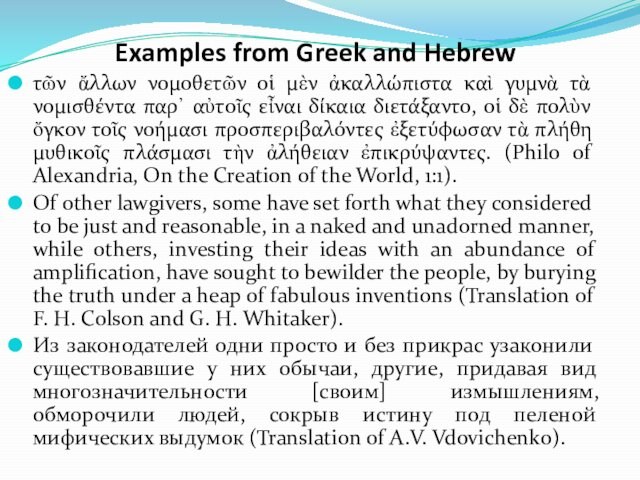

Examples from Greek and Hebrew τῶν ἄλλων νομοθετῶν οἱ μὲν ἀκαλλώπιστα καὶ γυμνὰ τὰ νομισθέντα παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς εἶναι δίκαια διετάξαντο, οἱ δὲ πολὺν ὄγκον τοῖς νοήμασι προσπεριβαλόντες ἐξετύφωσαν τὰ πλήθη μυθικοῖς πλάσμασι τὴν ἀλήθειαν ἐπικρύψαντες. (Philo of Alexandria, On the Creation of the World, 1:1). Of other lawgivers, some have set forth what they considered to be just and reasonable, in a naked and unadorned manner, while others, investing their ideas with an abundance of amplification, have sought to bewilder the people, by burying the truth under a heap of fabulous inventions (Translation of F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker). Из законодателей одни просто и без прикрас узаконили существовавшие у них обычаи, другие, придавая вид многозначительности [своим] измышлениям, обморочили людей, сокрыв истину под пеленой мифических выдумок (Translation of A.V. Vdovichenko).

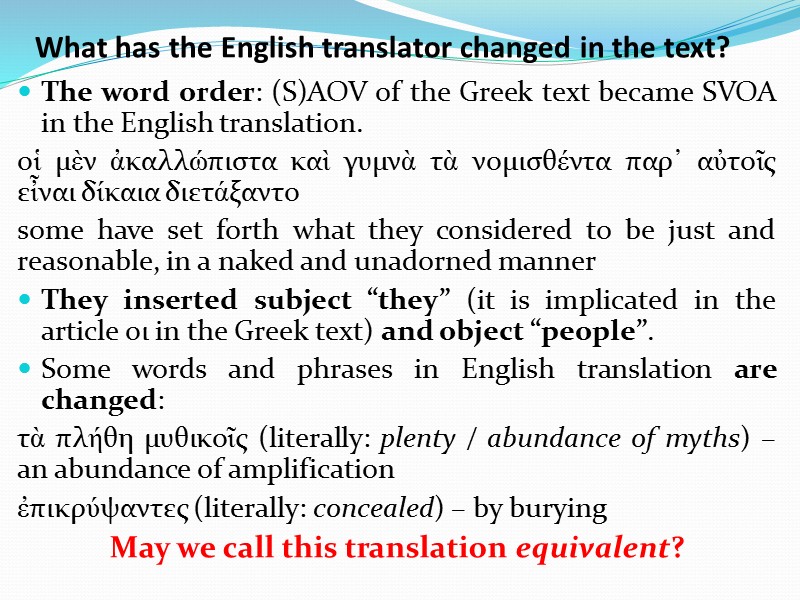

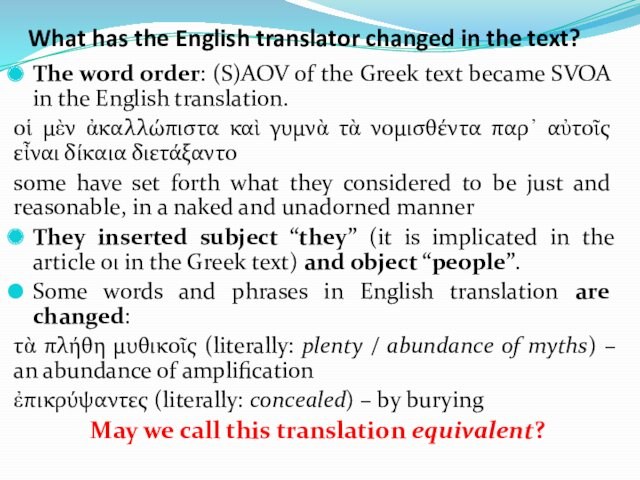

What has the English translator changed in the text? The word order: (S)AOV of the Greek text became SVOA in the English translation. οἱ μὲν ἀκαλλώπιστα καὶ γυμνὰ τὰ νομισθέντα παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς εἶναι δίκαια διετάξαντο some have set forth what they considered to be just and reasonable, in a naked and unadorned manner They inserted subject “they” (it is implicated in the article οι in the Greek text) and object “people”. Some words and phrases in English translation are changed: τὰ πλήθη μυθικοῖς (literally: plenty / abundance of myths) – an abundance of amplification ἐπικρύψαντες (literally: concealed) – by burying May we call this translation equivalent?

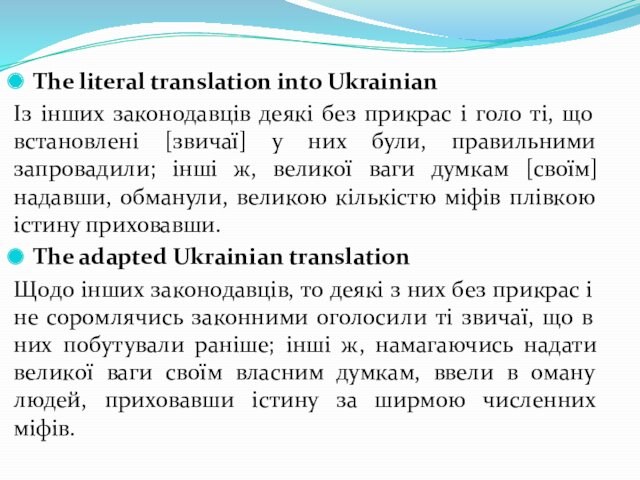

The literal translation into Ukrainian Із інших законодавців деякі без прикрас і голо ті, що встановлені [звичаї] у них були, правильними запровадили; інші ж, великої ваги думкам [своїм] надавши, обманули, великою кількістю міфів плівкою істину приховавши. The adapted Ukrainian translation Щодо інших законодавців, то деякі з них без прикрас і не соромлячись законними оголосили ті звичаї, що в них побутували раніше; інші ж, намагаючись надати великої ваги своїм власним думкам, ввели в оману людей, приховавши істину за ширмою численних міфів.

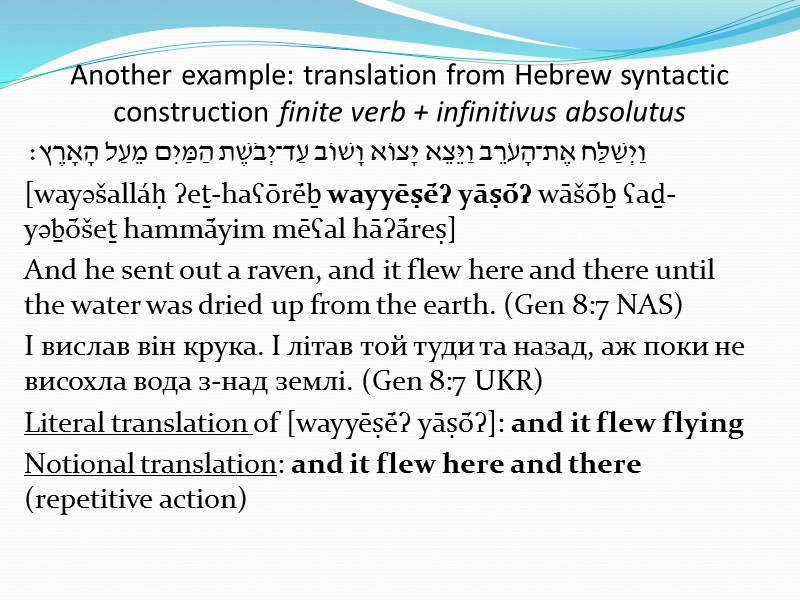

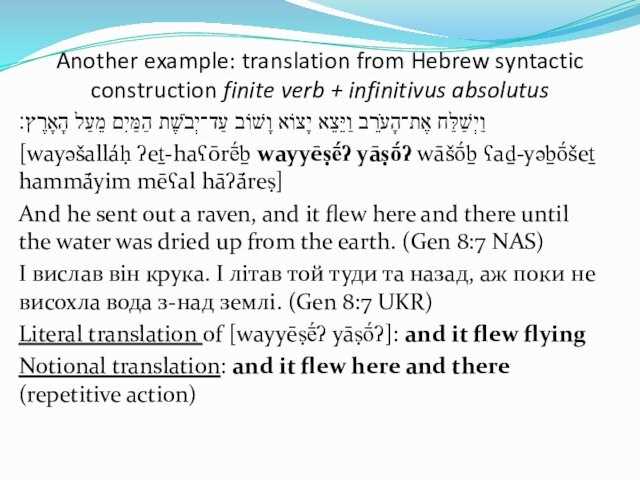

Another example: translation from Hebrew syntactic construction finite verb + infinitivus absolutus וַיְשַׁלַּח אֶת־הָעֹרֵב וַיֵּצֵא יָצוֹא וָשׁוֹב עַד־יְבֹשֶׁת הַמַּיִם מֵעַל הָאָרֶץ׃ [wayəšalláḥ ʔeṯ-haʕōrḗḇ wayyēṣḗʔ yāṣṓʔ wāšṓḇ ʕaḏ-yəḇṓšeṯ hammā́yim mēʕal hāʔā́reṣ] And he sent out a raven, and it flew here and there until the water was dried up from the earth. (Gen 8:7 NAS) І вислав він крука. І літав той туди та назад, аж поки не висохла вода з-над землі. (Gen 8:7 UKR) Literal translation of [wayyēṣḗʔ yāṣṓʔ]: and it flew flying Notional translation: and it flew here and there (repetitive action)

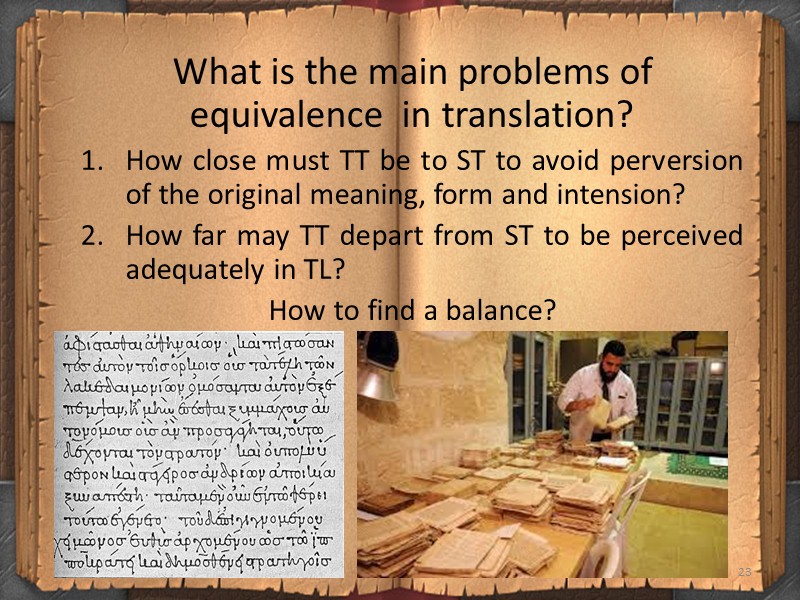

What is the main problems of equivalence in translation? How close must TT be to ST to avoid perversion of the original meaning, form and intension? How far may TT depart from ST to be perceived adequately in TL? How to find a balance? 23

Part 2 CONCEPTS OF EQUIVALENCE IN TRANSLATION

Jean-Paul Vinay and Jean Darbelnet theory Vinay and Darbelnet view equivalence-oriented translation as a procedure which ‘replicates the same situation as in the original, whilst using completely different wording’ (1995, p. 342). They also suggest that, if this procedure is applied during the translation process, it can maintain the stylistic impact of the SL text in the TL text. According to them, equivalence is therefore the ideal method when the translator has to deal with proverbs, idioms, clichés, nominal or adjectival phrases and the onomatopoeia of animal sounds.

Later they note that glossaries and collections of idiomatic expressions ‘can never be exhaustive’ (ibid.:256). They conclude by saying that ‘the need for creating equivalences arises from the situation, and it is in the situation of the SL text that translators have to look for a solution’ (ibid.: 255). Indeed, they argue that even if the semantic equivalent of an expression in the SL text is quoted in a dictionary or a glossary, it is not enough, and it does not guarantee a successful translation. 26

Roman Jacobson’s Theory of Equivalence “These three kinds of translation are to be differently labeled: 1 Intralingual translation or rewording is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs of the same language. 2 Interlingual translation or translation proper is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language. 3 Intersemiotic translation or transmutation is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (1959, p. 233).

“Most frequently, however, translation from one language into another substitutes messages in one language not for separate code-units but for entire messages in some other language. Such a translation is a reported speech; the translator recodes and transmits a message received from another source. Thus translation involves two equivalent messages in two different codes”. 28

Eugene Nida’s Theory of Translation Nida argued that there are two different types of equivalence, namely formal equivalence (or formal correspondence) and dynamic equivalence. Formal correspondence ‘focuses attention on the message itself, in both form and content’, unlike dynamic equivalence which is based upon ‘the principle of equivalent effect’ (1964:159). This theory is mainly expressed in the book Nida, Eugene A. and C. R. Taber. The Theory and Practice of Translation (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969 / 1982).

Formal correspondence consists of a TL item which represents the closest equivalent of a SL word or phrase. Dynamic equivalence is defined as a translation principle according to which a translator seeks to translate the meaning of the original in such a way that the TL wording will trigger the same impact on the TC audience as the original wording did upon the ST audience.

The advantage of the Nida-Taber’s concept is in their interest in the message of the text or, in other words, in its semantic quality. The disadvantage of this approach is in its inability to render poetry: poetical text demands not only semantic adequacy, but aesthetic-emotional aspects of communication. 31

“It is hard, however, to empirically test whether the translator has succeeded in producing a dynamic equivalence. The methods suggested by Nida-Taber provide means to make sure that the translation is idiomatic, but they lack reference to the source text regarding form and semantics”. Christoffer Gehrmann 32

John Catford’s theory John Catford had a preference for a more linguistic-based approach to translation. His main contribution in the field of translation theory is the introduction of the concepts of types and shifts of translation. Catford proposed very broad types of translation in terms of three criteria: The extent of translation (full translation vs partial translation); The grammatical rank at which the translation equivalence is established (rank-bound translation vs. unbounded translation); The levels of language involved in translation (total translation vs. restricted translation).

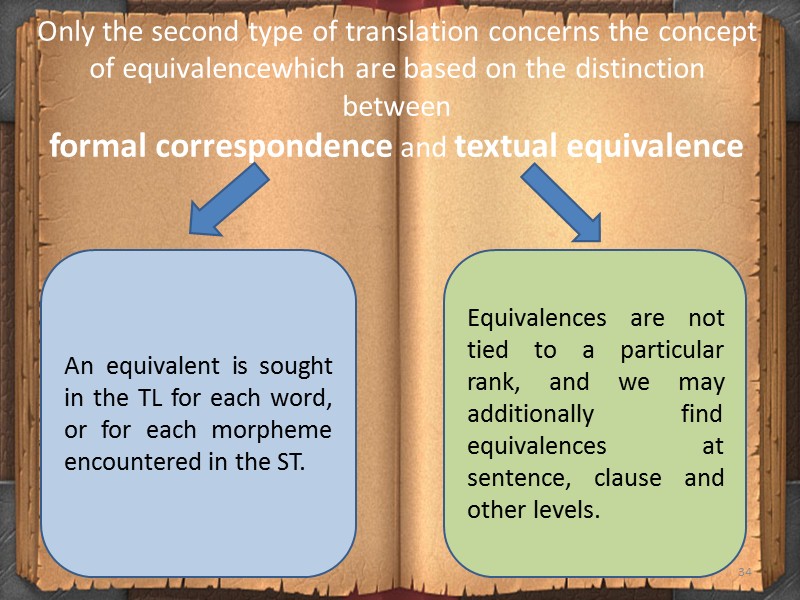

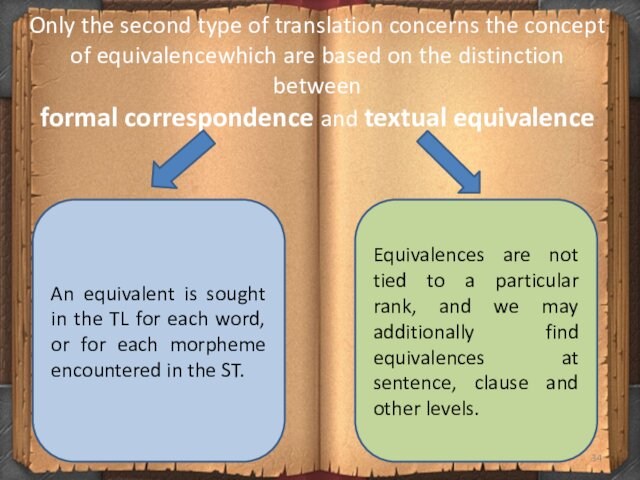

Only the second type of translation concerns the concept of equivalencewhich are based on the distinction between formal correspondence and textual equivalence 34 An equivalent is sought in the TL for each word, or for each morpheme encountered in the ST. Equivalences are not tied to a particular rank, and we may additionally find equivalences at sentence, clause and other levels.

However, in the process of rendering from SL to TL a translator departs from formal correspondence. J. Catford calls these departures “shifts”. There are two main types of translation shifts: level shifts, where the SL item at one linguistic level (e.g. grammar) has a TL equivalent at a different level (e.g. lexis), and category shifts which are divided into four types: 35

Structure-shifts, which involve a grammatical change between the structure of the ST and that of the TT; Class-shifts, when a SL item is translated with a TL item which belongs to a different grammatical class, i.e. a verb may be translated with a noun; Unit-shifts, which involve changes in rank; Intra-system shifts, which occur when ‘SL and TL possess systems which approximately correspond formally as to their constitution, but when translation involves selection of a non-corresponding term in the TL system’ (ibid.:80). For instance, when the SL singular becomes a TL plural. 36

Catford was criticized very much for his linguistic theory of translation. His critics denoted that the translation process cannot simply be reduced to a linguistic exercise, as claimed by Catford for instance, since there are also other factors, such as textual, cultural and situational aspects, which should be taken into consideration when translating. Linguistics is the only discipline which enables people to carry out a translation, since translating involves different cultures and different situations at the same time and they do not always match from one language to another.

Juliane Hause’s concept of equivalance Juliane House (1977) is in favour of semantic and pragmatic equivalence and argues that ST and TT should match one another in function. In fact, according to her theory, every text is in itself is placed within a particular situation which has to be correctly identified and taken into account by the translator. if the ST and the TT differ substantially on situational features, then they are not functionally equivalent, and the translation is not of a high quality.

Central to House’s discussion is the concept of overt and covert translations. In an overt translation the TT audience is not directly addressed and there is therefore no need at all to attempt to recreate a ‘second original’ since an overt translation ‘must overtly be a translation’ (1977, p. 189). By covert translation, on the other hand, is meant the production of a text which is functionally equivalent to the ST. House also argues that in this type of translation the ST ‘is not specifically addressed to a TC audience’ (ibid., p. 194). 39

Mona Baker: different types of equivalence Equivalence that can appear at word level and above word level, when translating from one language into another. Equivalence at word level is the first element to be taken into consideration by the translator. In fact, when the translator starts analyzing the ST s/he looks at the words as single units in order to find a direct ‘equivalent’ term in the TL. Baker gives a definition of the term word since it should be remembered that a single word can sometimes be assigned different meanings in different languages and might be regarded as being a more complex unit or morpheme. This means that the translator should pay attention to a number of factors when considering a single word, such as number, gender and tense (ibid.:11-12).

Grammatical equivalence. She notes that grammatical rules may vary across languages and this may pose some problems in terms of finding a direct correspondence in the TL. In fact, she claims that different grammatical structures in the SL and TL may cause remarkable changes in the way the information or message is carried across. Textual equivalence. The equivalence between a SL text and a TL text in terms of information and cohesion. It is up to the translator to decide whether or not to maintain the cohesive ties as well as the coherence of the SL text. His or her decision will be guided by three main factors, that is, the target audience, the purpose of the translation and the text type. Pragmatic equivalence. The role of the translator is to recreate the author’s intention in another culture in such a way that enables the TC reader to understand it clearly.

Five types of equivalence in accordance with Verner Koller: Denotative: the main content of the text is preserved (or “invariance of the content”) Connotative: purposeful rendering of connotations of the text by using of synonyms (or “stylistic equivalence”) Text-normative: rendering of genre and norms of languages Pragmatic: orientation to a receiver (or “communicative equivalence”) Formal: rendering of formal specificities of the original text (word play, pun, individual vocabulary of characters, etc.).

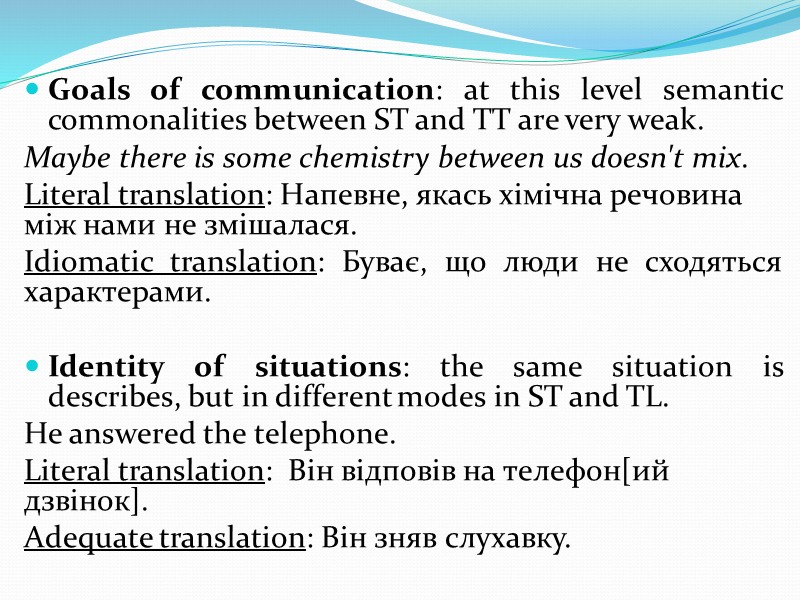

Types (levels) of equivalence according to V.N. Komissarov (В.Н. Комиссаров) V. N. Komissarov singles out four stages of semantic commonality between ST and TT: Goals of communication; Identity of situations; Modes of description of the situation; Meaning of syntactic structures; Meaning of word-signs.

Goals of communication: at this level semantic commonalities between ST and TT are very weak. Maybe there is some chemistry between us doesn’t mix. Literal translation: Напевне, якась хімічна речовина між нами не змішалася. Idiomatic translation: Буває, що люди не сходяться характерами. Identity of situations: the same situation is describes, but in different modes in ST and TL. Не answered the telephone. Literal translation: Він відповів на телефон[ий дзвінок]. Adequate translation: Він зняв слухавку.

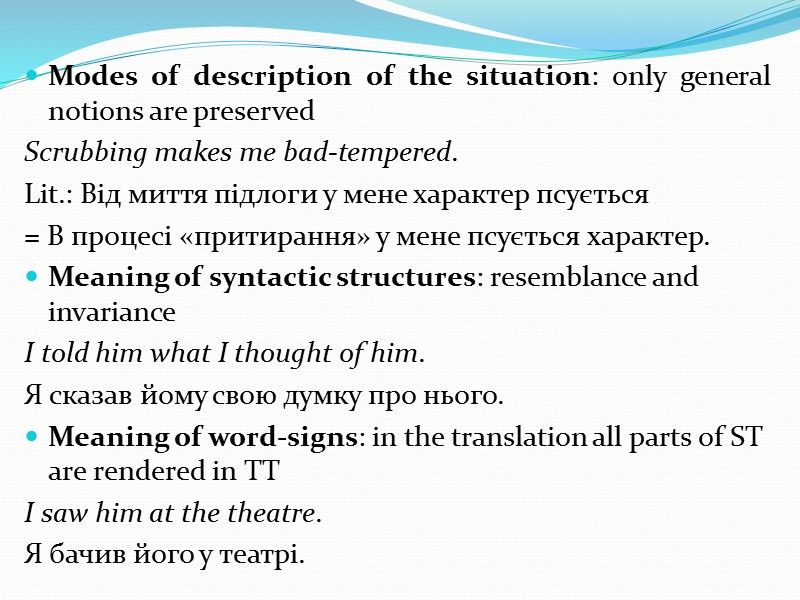

Modes of description of the situation: only general notions are preserved Scrubbing makes me bad-tempered. Lit.: Від миття підлоги у мене характер псується = В процесі «притирання» у мене псується характер. Meaning of syntactic structures: resemblance and invariance I told him what I thought of him. Я сказав йому свою думку про нього. Meaning of word-signs: in the translation all parts of ST are rendered in TT I saw him at the theatre. Я бачив його у театрі.

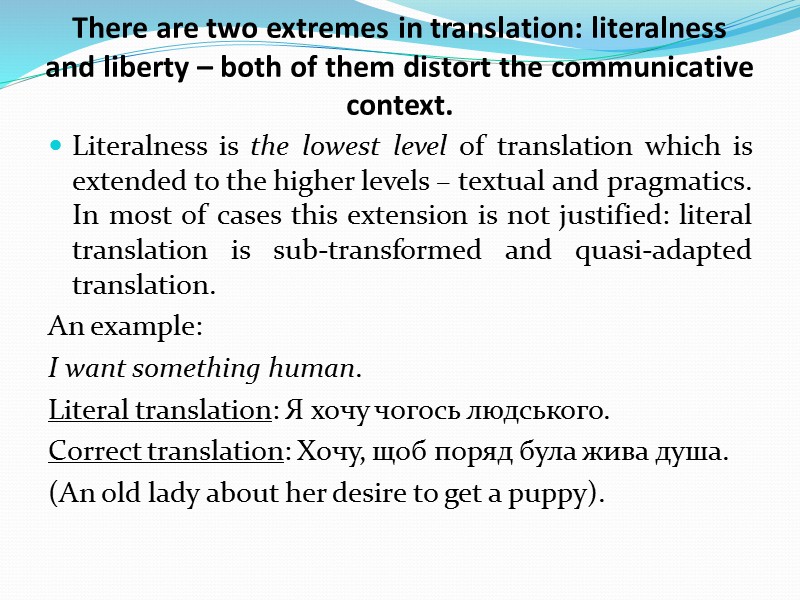

There are two extremes in translation: literalness and liberty – both of them distort the communicative context. Literalness is the lowest level of translation which is extended to the higher levels – textual and pragmatics. In most of cases this extension is not justified: literal translation is sub-transformed and quasi-adapted translation. An example: I want something human. Literal translation: Я хочу чогось людського. Correct translation: Хочу, щоб поряд була жива душа. (An old lady about her desire to get a puppy).

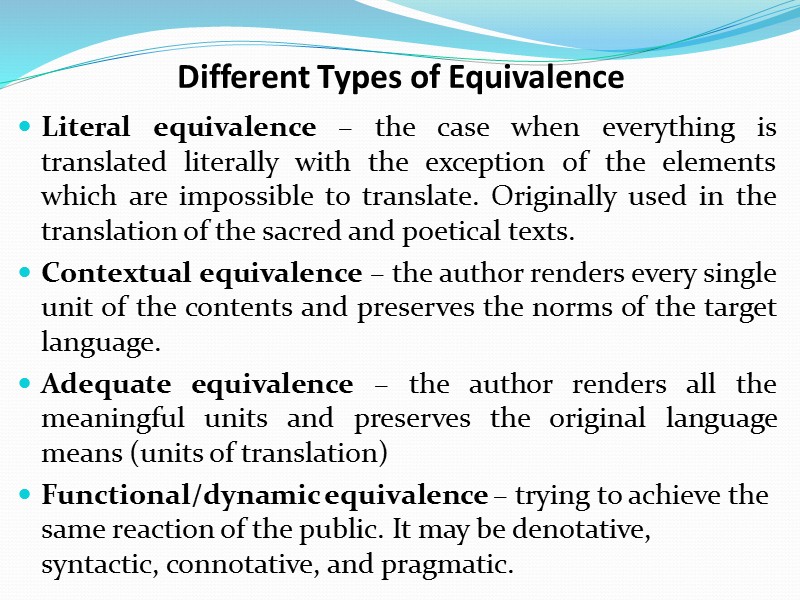

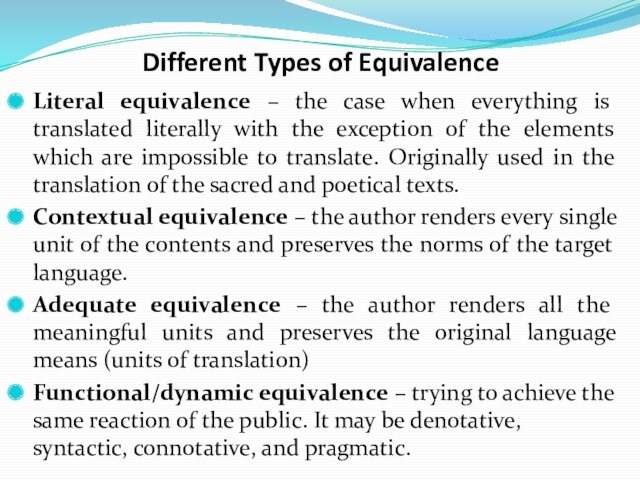

Different Types of Equivalence Literal equivalence – the case when everything is translated literally with the exception of the elements which are impossible to translate. Originally used in the translation of the sacred and poetical texts. Contextual equivalence – the author renders every single unit of the contents and preserves the norms of the target language. Adequate equivalence – the author renders all the meaningful units and preserves the original language means (units of translation) Functional/dynamic equivalence – trying to achieve the same reaction of the public. It may be denotative, syntactic, connotative, and pragmatic.

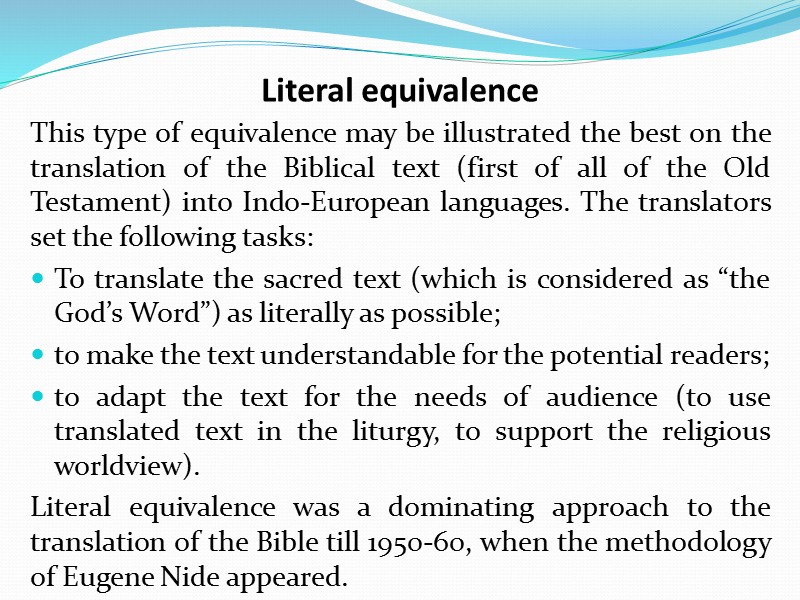

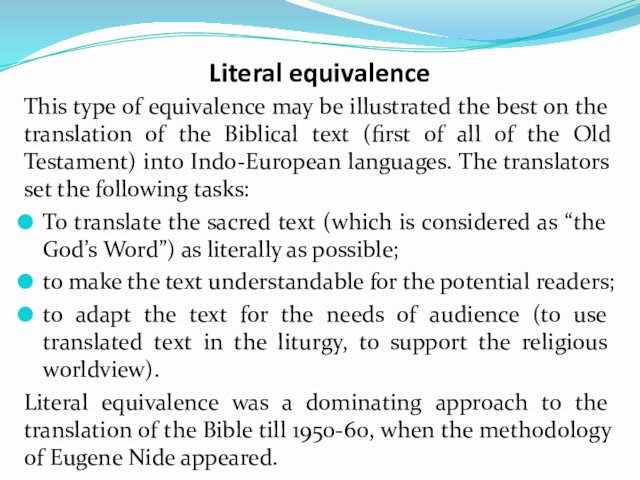

Literal equivalence This type of equivalence may be illustrated the best on the translation of the Biblical text (first of all of the Old Testament) into Indo-European languages. The translators set the following tasks: To translate the sacred text (which is considered as “the God’s Word”) as literally as possible; to make the text understandable for the potential readers; to adapt the text for the needs of audience (to use translated text in the liturgy, to support the religious worldview). Literal equivalence was a dominating approach to the translation of the Bible till 1950-60, when the methodology of Eugene Nide appeared.

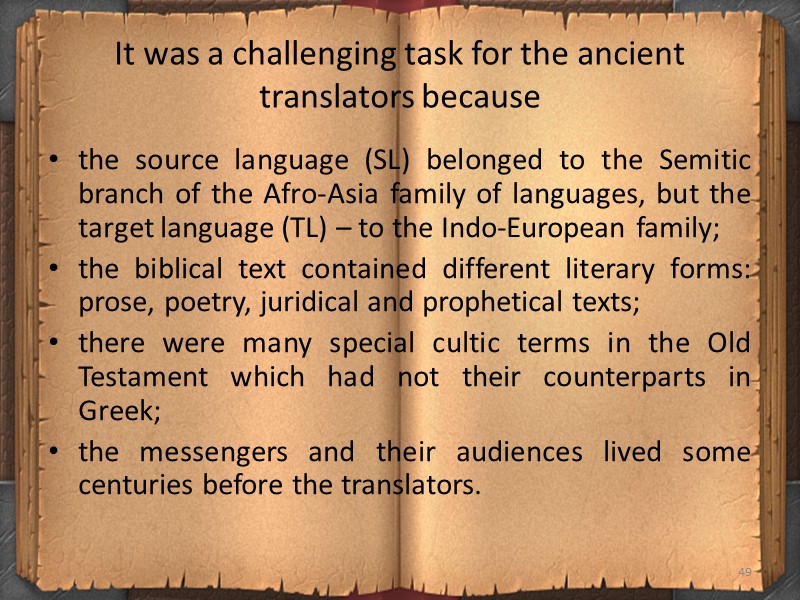

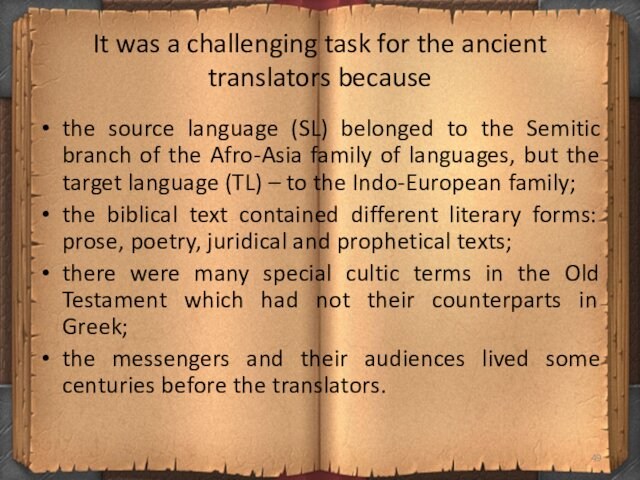

It was a challenging task for the ancient translators because the source language (SL) belonged to the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asia family of languages, but the target language (TL) – to the Indo-European family; the biblical text contained different literary forms: prose, poetry, juridical and prophetical texts; there were many special cultic terms in the Old Testament which had not their counterparts in Greek; the messengers and their audiences lived some centuries before the translators. 49

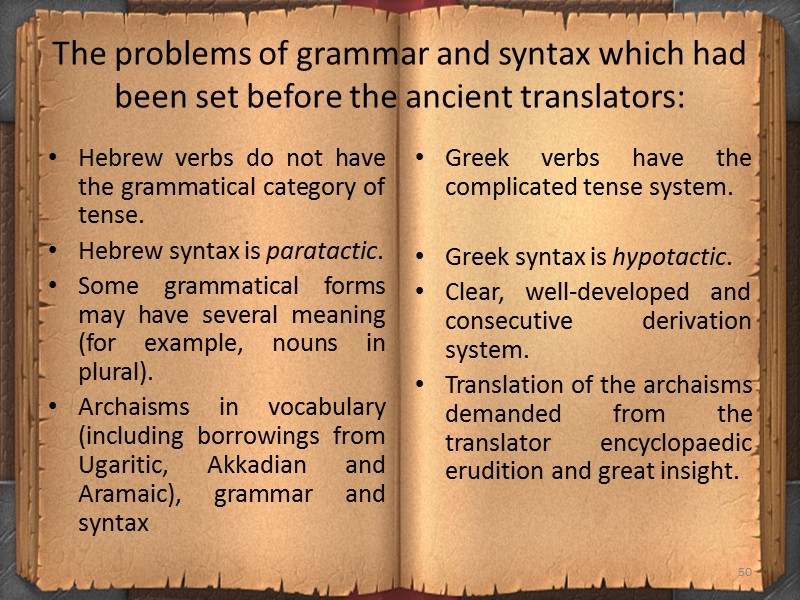

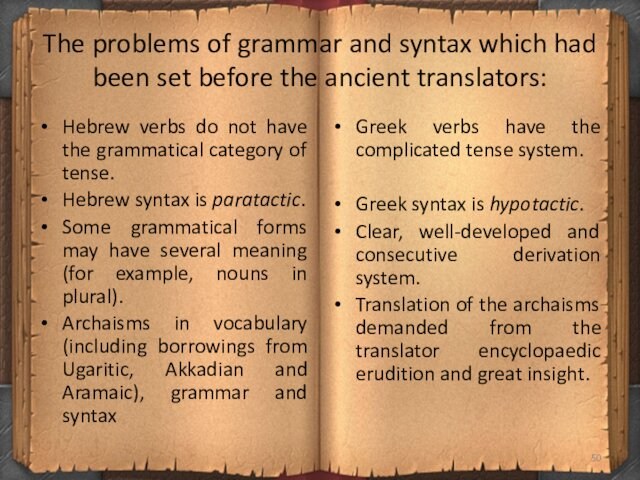

The problems of grammar and syntax which had been set before the ancient translators: Hebrew verbs do not have the grammatical category of tense. Hebrew syntax is paratactic. Some grammatical forms may have several meaning (for example, nouns in plural). Archaisms in vocabulary (including borrowings from Ugaritic, Akkadian and Aramaic), grammar and syntax Greek verbs have the complicated tense system. Greek syntax is hypotactic. Clear, well-developed and consecutive derivation system. Translation of the archaisms demanded from the translator encyclopaedic erudition and great insight. 50

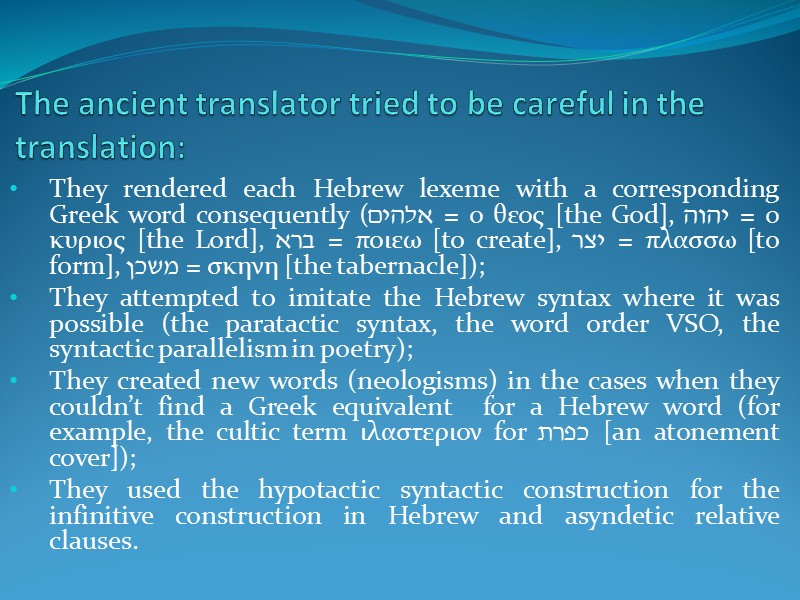

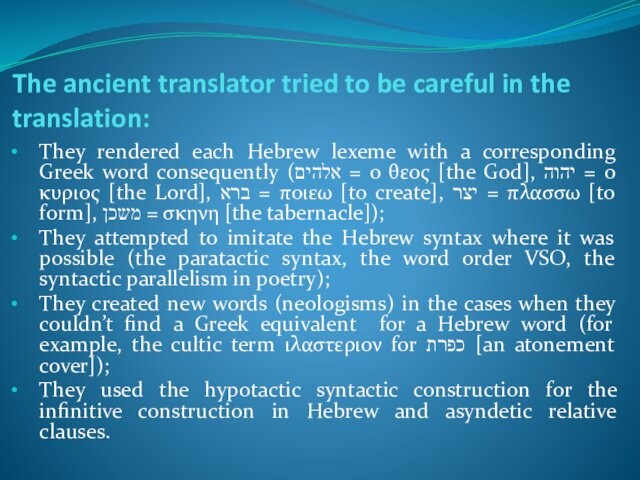

The ancient translator tried to be careful in the translation: They rendered each Hebrew lexeme with a corresponding Greek word consequently (אלהים = ο θεος [the God], יהוה = ο κυριος [the Lord], ברא = ποιεω [to create], יצר = πλασσω [to form], משכן = σκηνη [the tabernacle]); They attempted to imitate the Hebrew syntax where it was possible (the paratactic syntax, the word order VSO, the syntactic parallelism in poetry); They created new words (neologisms) in the cases when they couldn’t find a Greek equivalent for a Hebrew word (for example, the cultic term ιλαστεριον for כפרת [an atonement cover]); They used the hypotactic syntactic construction for the infinitive construction in Hebrew and asyndetic relative clauses.

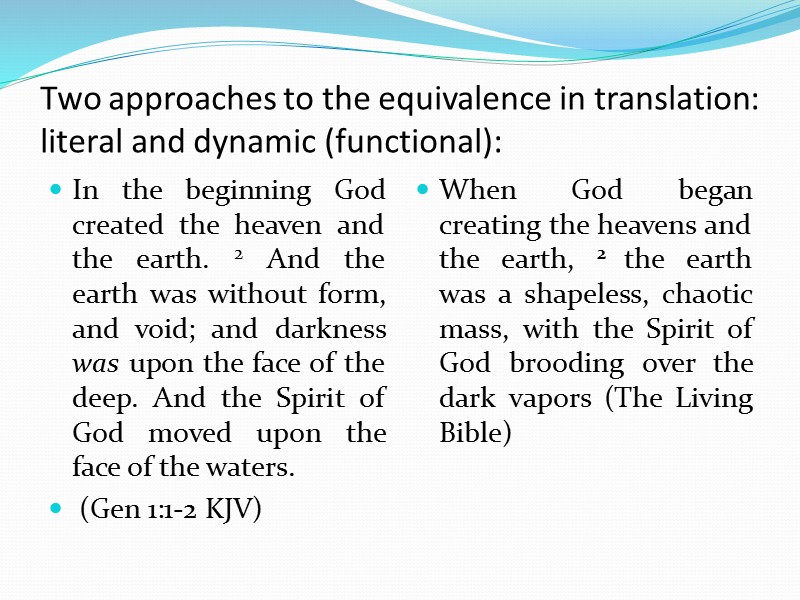

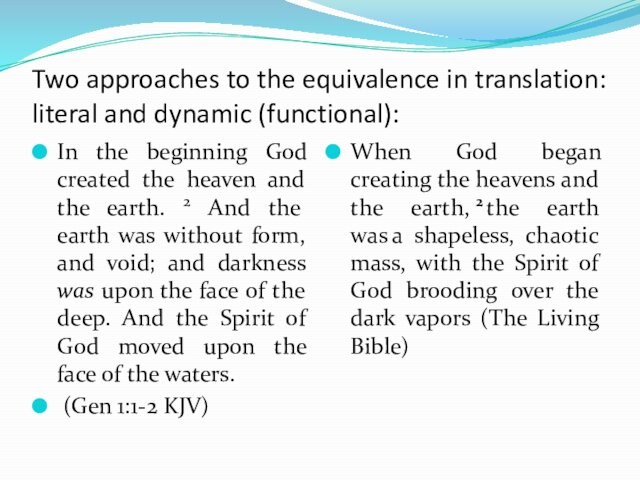

Two approaches to the equivalence in translation: literal and dynamic (functional): In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. (Gen 1:1-2 KJV) When God began creating the heavens and the earth, 2 the earth was a shapeless, chaotic mass, with the Spirit of God brooding over the dark vapors (The Living Bible)

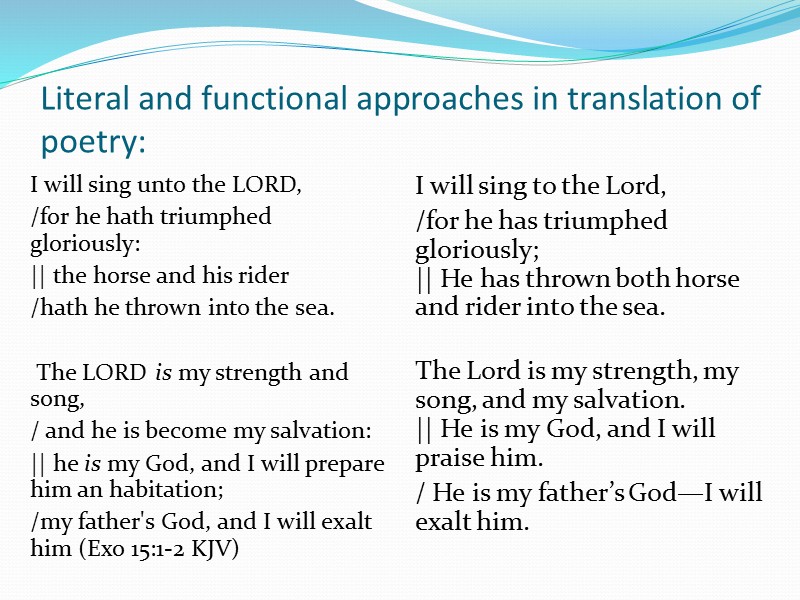

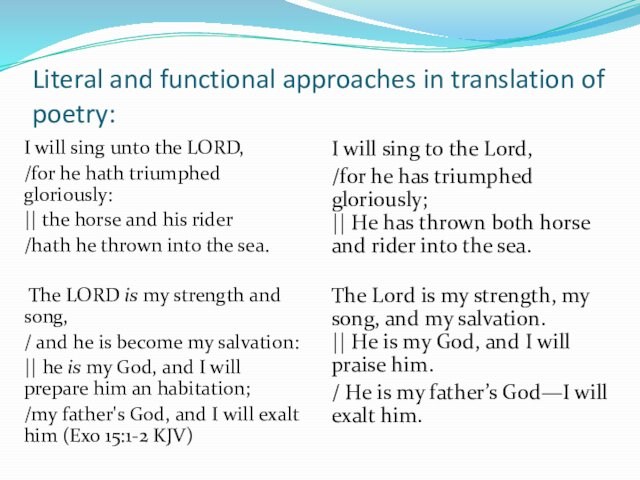

Literal and functional approaches in translation of poetry: I will sing unto the LORD, /for he hath triumphed gloriously: || the horse and his rider /hath he thrown into the sea. The LORD is my strength and song, / and he is become my salvation: || he is my God, and I will prepare him an habitation; /my father’s God, and I will exalt him (Exo 15:1-2 KJV) I will sing to the Lord, /for he has triumphed gloriously; || He has thrown both horse and rider into the sea. The Lord is my strength, my song, and my salvation. || He is my God, and I will praise him. / He is my father’s God—I will exalt him.

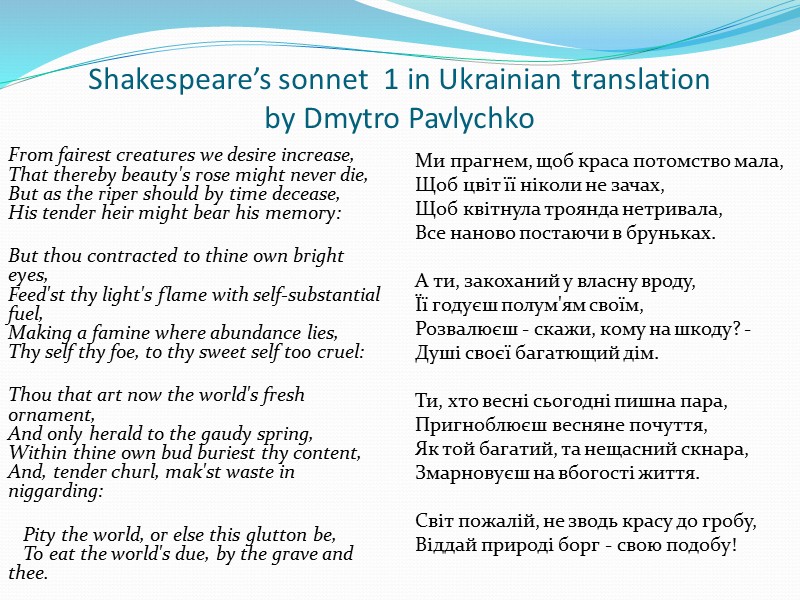

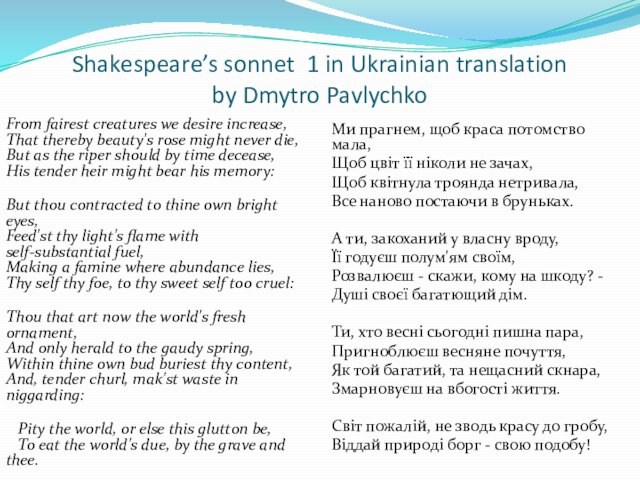

Shakespeare’s sonnet 1 in Ukrainian translation by Dmytro Pavlychko From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauty’s rose might never die, But as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory: But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes, Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel, Making a famine where abundance lies, Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel: Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament, And only herald to the gaudy spring, Within thine own bud buriest thy content, And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding: Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee. Ми прагнем, щоб краса потомство мала, Щоб цвіт її ніколи не зачах, Щоб квітнула троянда нетривала, Все наново постаючи в бруньках. А ти, закоханий у власну вроду, Її годуєш полум’ям своїм, Розвалюєш — скажи, кому на шкоду? — Душі своєї багатющий дім. Ти, хто весні сьогодні пишна пара, Пригноблюєш весняне почуття, Як той багатий, та нещасний скнара, Змарновуєш на вбогості життя. Світ пожалій, не зводь красу до гробу, Віддай природі борг — свою подобу!

Слайд 1

TYPES AND LEVELS OF EQUIVALENCE

Lectures # 4-5

By Dr.

Dmytro Tsolin

Слайд 2

What is equivalence in translation?

Equivalence in translation is

a functional coincidence between the source and the target

text (А. Попович 1980).

Equivalent is an element of the target

language whose function coincides with other element of the source language with the same function (О. Ахманова 1966).

Слайд 3

Equivalence and Adequacy

Many scholars use these terms as

synonyms (R. Levitsky, J. Catford).

V. N. Komissarov considers “adequacy”

as a characteristic of translation in general, while “equivalence” describes

correlation between units of SL and TL.

Adequacy as a kind of correlation between ST and TT which takes into account the aim of translation has been considered by K. Reiss and G. Vermeer.

In translation equivalence is set not between word-signs as themselves, but between actual signs as segments of the text (A. Schweizer).

Слайд 4

Correlation between equivalence and adequacy according to A.

Schweizer

equivalence

adequacy

object

object

Translation as a result

Translation as a process

Слайд 5

Equivalence implies an adequate rendering of SL-codes by

TL-codes; this process includes the following levels:

Adequacy of vocabulary

(taking into account semantic connotations of the words and their

stylistic functions)

Grammatical adequacy

Correspondence between syntactic constructions of SL and TL (literal rendering is not always possible)

Translation of idioms on the base of semantic equivalence (they cannot be translated literally)

Contextual adequacy (at the level of macrotextual elements cohesion)

Stylistic correspondence between ST and TL

Слайд 6

Equivalence of the text is more important than

equivalence of it segments!!!

Слайд 7

Adequacy of vocabulary

βλέπομεν γὰρ ἄρτι δι᾽ ἐσόπτρου ἐν

αἰνίγματι, τότε δὲ πρόσωπον πρὸς πρόσωπον· ἄρτι γινώσκω ἐκ

μέρους, τότε δὲ ἐπιγνώσομαι καθὼς καὶ ἐπεγνώσθην. (1Co 13:12)

Literal translation of

ο έσοπτρον – “a mirror”

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (1Co 13:12 KJV)

Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. (1Co 13:12 NIV)

Отож, тепер бачимо ми ніби у дзеркалі, у загадці, але потім обличчям в обличчя; тепер розумію частинно, а потім пізнаю, як і пізнаний я. (1Co 13:12 UKR)

Слайд 9

וּפָגְשׁוּ צִיִּים אֶת־אִיִּים וְשָׂעִיר עַל־רֵעֵהוּ יִקְרָא אַךְ־שָׁם הִרְגִּיעָה

לִּילִית וּמָצְאָה לָהּ מָנוֹחַ׃

[ūṕāḡšū́ ṣiyyī́m ʔeṯ-ʔiyyī́m wəśāʕī́r ʕal-rēʕēhū́ yiqrā́ʔ

ʔaḵ-šā́m hirgīʕā́ līlīṯ ūmāṣəʔā́ lāh mānṓaḥ]

The wild beasts of the

desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest. (Isa 34:14 KJV)

And the desert creatures shall meet with the wolves, the hairy goat also shall cry to its kind; Yes, the night monster shall settle there And shall find herself a resting place. (Isa 34:14 NAS)

І будуть стрічатися там дикі звірі пустинні з гієнами, а польовик буде кликати друга свого; Ліліт тільки там заспокоїться і знайде собі відпочинок! (Isa 34:14 UKR)

Слайд 10

Special terms from the ancient Mesopotamian mythology:

ṣiyyī́m –

demos of desert

śāʕī́r – demon in the shape of

goat

līlīṯ – lilith (night she-demon relating to sexual life)

Слайд 11

What to do, if TL does not have

equivalent counterparts for some lexemes of SL?

ṣiyyī́m –

“wild beasts” / “the desert creatures” / «дикі звірі пустині»

śāʕī́r

– “the satyr” / “the hairy goat” / «польовик»

līlīṯ – “the screech owl” / “the night monster” / «Ліліт»

To create a neologism on the base of the SL-term (“Lilith”)

To find a word or phrase which describes the SL-term approximately (“wild beasts”, “the desert creatures”)

To use a loanword (with similar meaning) which is well-know in TL (“the satyr” from Greek σατυρος)

Слайд 12

Grammatical and syntactic equivalence

How to translate correctly the

following English sentences into Ukrainian?

My mum was baking an

apple pie in the kitchen when a shot rang out

in the street.

I have just finished my homework.

If you hadn’t lost the key, we would have got the concert in time.

Слайд 13

The problem is that in Ukrainian are not

direct equivalents for the following grammatical forms:

Past continuous (durative

action in the past coincides with минулий недоконаний).

Present Perfect (coincides

with минулий доконаний).

Third conditional (second and third conditionals coincide formally in Ukrainian: якби + минулий час. дієслова, би + минулий час. дієслова).

Adequate translation is possible? Of course.

Моя мама пекла пиріг з яблуками, коли на вулиці прогримів постріл.

Я тільки-но закінчив свою робити хатню роботу.

Якби ти не забув ключ, ми б встигли на концерт.

Слайд 14

In the first case the durative aspect is

clear out of the context: it is said about

a short period of time in the past, not about

a habitual action.

In the second case the perfect aspect is highlighted with the particle –но (which, however, is not obligatory here).

In the third case it is quite clear that the speaker tells about the past from the context.

It means that differences between the grammar of SL and TL may be compensated with other linguistic factors: syntax, context, particles, cohesion of text, etc.

Слайд 15

Contextual Adequacy

Only limited number of words have one

meaning, but most of them have several semantic variants

which may be clarified from the context.

Words with one

meaning are mainly special terms or lexemes which designate specific items:

allusion, organization, technology, methodology, dodder, dog-bee, etc.

Words with many meanings prevail in any language:

He received a special membership card and a club pin onto his lapel.

One of them cleverly decorates a vase by drawing plant leaves using a sharp pin, while another shapes small frog-like figures to be put on ashtrays.

Слайд 16

She was very nimble on her pins.

A bolt

from the blue.

A great bolt of white lightning

flashed out of thin air.

Crossbow bolts and arrows passed like

clouds across the face of the sun.

The room is stacked with bolts of cloth.

Those leaves which present a double or quadruple fold, technically termed «the bolt».

Слайд 17

Translation of idioms:

The captain held his peace

that evening and for many evenings to come (R.

Stevenson)

Literal (mechanical) translation: Капітан тримав свій мир того вечора і

протягом багатьох наступних вечорів.

Correct translation: Капітан мовчав / тримав язик за зубами того вечора і протягом наступних вечорів.

Miss Williams will look after you well because she knows the ropes (J. Aldridge)

Literal translation: Міс Уільямс догляне тебе добре, бо вона знає мотузки.

Correct translation: Міс Уільямс потурбується про тебе добре / належно, бо вона знає свою справу.

Слайд 18

Her father kissed her when she left

him with lips which she was sure had trembled.

From the warmth of her embrace he probably divined that

he had let the cat out of the bag (J. Galsworthy).

Literal translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона покидала його, устами, про які вона була упевнена, що вони затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що випустив кота з мішка.

Correct translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона йшла від нього, устами, які, здалося їй, затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що видав свої почуття.

Слайд 19

Examples from Greek and Hebrew

τῶν ἄλλων νομοθετῶν

οἱ μὲν ἀκαλλώπιστα καὶ γυμνὰ τὰ νομισθέντα παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς

εἶναι δίκαια διετάξαντο, οἱ δὲ πολὺν ὄγκον τοῖς νοήμασι προσπεριβαλόντες

ἐξετύφωσαν τὰ πλήθη μυθικοῖς πλάσμασι τὴν ἀλήθειαν ἐπικρύψαντες. (Philo of Alexandria, On the Creation of the World, 1:1).

Of other lawgivers, some have set forth what they considered to be just and reasonable, in a naked and unadorned manner, while others, investing their ideas with an abundance of amplification, have sought to bewilder the people, by burying the truth under a heap of fabulous inventions (Translation of F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker).

Из законодателей одни просто и без прикрас узаконили существовавшие у них обычаи, другие, придавая вид многозначительности [своим] измышлениям, обморочили людей, сокрыв истину под пеленой мифических выдумок (Translation of A.V. Vdovichenko).

Слайд 20

What has the English translator changed in the

text?

The word order: (S)AOV of the Greek text became

SVOA in the English translation.

οἱ μὲν ἀκαλλώπιστα καὶ γυμνὰ τὰ

νομισθέντα παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς εἶναι δίκαια διετάξαντο

some have set forth what they considered to be just and reasonable, in a naked and unadorned manner

They inserted subject “they” (it is implicated in the article οι in the Greek text) and object “people”.

Some words and phrases in English translation are changed:

τὰ πλήθη μυθικοῖς (literally: plenty / abundance of myths) – an abundance of amplification

ἐπικρύψαντες (literally: concealed) – by burying

May we call this translation equivalent?

Слайд 21

The literal translation into Ukrainian

Із інших законодавців деякі

без прикрас і голо ті, що встановлені [звичаї] у

них були, правильними запровадили; інші ж, великої ваги думкам [своїм]

надавши, обманули, великою кількістю міфів плівкою істину приховавши.

The adapted Ukrainian translation

Щодо інших законодавців, то деякі з них без прикрас і не соромлячись законними оголосили ті звичаї, що в них побутували раніше; інші ж, намагаючись надати великої ваги своїм власним думкам, ввели в оману людей, приховавши істину за ширмою численних міфів.

Слайд 22

Another example: translation from Hebrew syntactic construction finite

verb + infinitivus absolutus

וַיְשַׁלַּח אֶת־הָעֹרֵב וַיֵּצֵא יָצוֹא וָשׁוֹב עַד־יְבֹשֶׁת

הַמַּיִם מֵעַל הָאָרֶץ׃

[wayəšalláḥ ʔeṯ-haʕōrḗḇ wayyēṣḗʔ yāṣṓʔ wāšṓḇ ʕaḏ-yəḇṓšeṯ hammā́yim

mēʕal hāʔā́reṣ]

And he sent out a raven, and it flew here and there until the water was dried up from the earth. (Gen 8:7 NAS)

І вислав він крука. І літав той туди та назад, аж поки не висохла вода з-над землі. (Gen 8:7 UKR)

Literal translation of [wayyēṣḗʔ yāṣṓʔ]: and it flew flying

Notional translation: and it flew here and there (repetitive action)

Слайд 23

What is the main problems of equivalence in

translation?

How close must TT be to ST to avoid

perversion of the original meaning, form and intension?

How far may

TT depart from ST to be perceived adequately in TL?

How to find a balance?

Слайд 24

Part 2

CONCEPTS OF EQUIVALENCE IN TRANSLATION

Слайд 25

Jean-Paul Vinay and

Jean Darbelnet theory

Vinay and Darbelnet

view equivalence-oriented translation as a procedure which ‘replicates the

same situation as in the original, whilst using completely different

wording’ (1995, p. 342). They also suggest that, if this procedure is applied during the translation process, it can maintain the stylistic impact of the SL text in the TL text.

According to them, equivalence is therefore the ideal method when the translator has to deal with proverbs, idioms, clichés, nominal or adjectival phrases and the onomatopoeia of animal sounds.

Слайд 26

Later they note that glossaries and collections of

idiomatic expressions ‘can never be exhaustive’ (ibid.:256). They conclude

by saying that ‘the need for creating equivalences arises from

the situation, and it is in the situation of the SL text that translators have to look for a solution’ (ibid.: 255).

Indeed, they argue that even if the semantic equivalent of an expression in the SL text is quoted in a dictionary or a glossary, it is not enough, and it does not guarantee a successful translation.

Слайд 27

Roman Jacobson’s Theory of Equivalence

“These three kinds

of translation are to be differently labeled:

1 Intralingual translation

or rewording is an interpretation of verbal signs by means

of other signs of the same language.

2 Interlingual translation or translation proper is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language.

3 Intersemiotic translation or transmutation is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (1959, p. 233).

Слайд 28

“Most frequently, however, translation from one language into

another substitutes messages in one language not for separate

code-units but for entire messages in some other language. Such

a translation is a reported speech; the translator recodes and transmits a message received from another source. Thus translation involves two equivalent messages in two different codes”.

Слайд 29

Eugene Nida’s Theory of Translation

Nida argued that there

are two different types of equivalence, namely formal equivalence (or

formal correspondence) and dynamic equivalence.

Formal correspondence ‘focuses attention on the message

itself, in both form and content’, unlike dynamic equivalence which is based upon ‘the principle of equivalent effect’ (1964:159).

This theory is mainly expressed in the book Nida, Eugene A. and C. R. Taber. The Theory and Practice of Translation (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969 / 1982).

Слайд 30

Formal correspondence consists of a TL item which

represents the closest equivalent of a SL word or

phrase.

Dynamic equivalence is defined as a translation principle according to

which a translator seeks to translate the meaning of the original in such a way that the TL wording will trigger the same impact on the TC audience as the original wording did upon the ST audience.

Слайд 31

The advantage of the Nida-Taber’s concept is in

their interest in the message of the text or,

in other words, in its semantic quality.

The disadvantage of

this approach is in its inability to render poetry: poetical text demands not only semantic adequacy, but aesthetic-emotional aspects of communication.

Слайд 32

“It is hard, however, to empirically test whether

the translator has succeeded in producing a dynamic equivalence.

The methods suggested by Nida-Taber provide means to make sure

that the translation is idiomatic, but they lack reference to the source text regarding form and semantics”.

Christoffer Gehrmann

Слайд 33

John Catford’s theory

John Catford had a preference for

a more linguistic-based approach to translation. His main contribution

in the field of translation theory is the introduction of

the concepts of types and shifts of translation. Catford proposed very broad types of translation in terms of three criteria:

The extent of translation (full translation vs partial translation);

The grammatical rank at which the translation equivalence is established (rank-bound translation vs. unbounded translation);

The levels of language involved in translation (total translation vs. restricted translation).

Слайд 34

Only the second type of translation concerns the