The Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) was the very first general-purpose electronic computer. It was designed primarily to calculate artillery firing tables to be used by the United States Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory to help US troops during World War II. The artillery firing tables helped to predict where an artillery shell would hit, allowing troops to hit their targets more precisely or evade incoming shells. The first programs written for the ENIAC included a study of the hydrogen bomb’s feasibility.

Techopedia Explains Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer

The Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer design and construction was lead by Maj. Gen. Gladeon Marcus Barnes and financed by the Research and Development Command of the US Army Ordnance Corps. The contract for construction was signed on June 5, 1943 and secret work started in July at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania under the codename “Project PX.”

ENIAC was designed and proposed by John Mauchly 1942, but the concept was plagiarized from John Vincent Atanasoff who later won the lawsuit over this matter in 1972. ENIAC was designed to be a modular computer to be composed of individual panels that perform separate functions, and it was the first large-scale computer to run solely on electronic components without any mechanical parts slowing it down. Because of its design and 100 kHz clock, it could do 5000 cycles per second for operations on 10-digit numbers, as the basic machine cycle was 200 microseconds long. During one cycle, it could write and read from a register or add/subtract two numbers. Although it was initially designed for military applications, the ENIAC was also used to solve complex mathematics, engineering, and physics problems, and was programmed by manipulating a series of switches and cables.

The ENIAC team consisted of:

- John Mauchly – Designer

- J. Presper Eckert – Co-designer

- Thomas Kite Sharpless – Master programmer

- Robert F. Shaw – Function tables

- Jeffrey Chuan Chu – Square-rooter/divider

- Arthur Burks – Multiplier

- Harry Huskey – Reader/printer

- Jack Davis – Accumulators

Components of the ENIAC included:

- 1,468 vacuum tubes

- 70,000 resistors

- 10,000 capacitors

- 7,200 crystal diodes

- 1,500 relays

- 5,000,000 hand-soldered joints

Updated: 05/02/2021 by

Short for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, the ENIAC was the first electronic computer used for general purposes, such as solving numerical problems. It was designed and invented by John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the University of Pennsylvania to calculate artillery firing tables for the US Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory.

Its construction began in 1943 and was not completed until 1946. Although it was not completed until the end of World War II, the ENIAC was created to help with the war effort against German forces. During the war, there was a shortage of male engineers, so the programming was done by a team of six women computers: Betty Jean Jennings (Bartik), Marilyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Elizabeth Snyder, Frances Bilas, and Kathleen McNulty

In 1953, the Burroughs Corporation built a 100-word magnetic-core memory, which added to the ENIAC’s memory capabilities, which at the time only held a 20-word internal memory. By 1956, the end of its operation, the ENIAC occupied about 1,800 square feet with almost 20,000 vacuum tubes, 1,500 relays, 10,000 capacitors, and 70,000 resistors. It also used 200 kilowatts of electricity, weighed over 30 tons, and cost about $487,000.

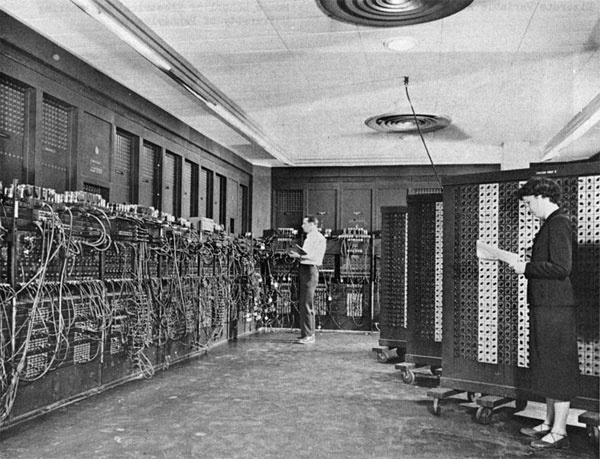

The picture is a public domain U.S. Army photo of the ENIAC. The wires, switches, and components are all part of the ENIAC with two of the team of operators helping run the machine. The ENIAC is now being displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. In 1996, the U.S. Postal Services released a new stamp commemorating the 50th birthday of the ENIAC.

How many transistors did the ENIAC have?

Zero. The ENIAC used vacuum tubes and did not use transistors as they were not yet invented.

Computer acronyms, CSIRAC, EDVAC, Hardware terms, UNIVAC

- Текст

- Веб-страница

When was the first analog computer built?

Where and how was that computer used?

When did the first digital computers appear?

Who was the inventor of the first digital computer?

What could that device do?

What is ENIAC? Decode the word.

What was J. Neumann’s contribution into the development of computers?

What were the advantages of EDVAC in comparison with ENIAC?

What does binary code mean?

Due to what invention could the first digital computers be built?

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

When was the first analog computer built?Where and how was that computer used?When did the first digital computers appear?Who was the inventor of the first digital computer?What could that device do?What is ENIAC? Decode the word.What was J. Neumann’s contribution into the development of computers?What were the advantages of EDVAC in comparison with ENIAC?What does binary code mean?Due to what invention could the first digital computers be built?

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Когда был первый аналоговый компьютер, построенный? Где и как был, что компьютер используется? Когда появятся первые цифровые компьютеры? Кто был изобретателем первого цифрового компьютера? Что может, что устройство делать? Что ENIAC? Расшифруйте слово. Что вклад Дж Неймана в развитие компьютеров? Какие преимущества EDVAC по сравнению с ENIAC? Что двоичный код означает? Из-за того, что изобретение может первые цифровые компьютеры будут построены?

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

когда был первый аналоговый компьютер построил?

, где и как этот компьютер используется?

, когда первый цифровой компьютеров появится?

, кто стал автором первой цифровой компьютер?

что бы это устройство?

что эниак?расшифровать слово.

что J.) за вклад в развитие компьютеров?

что преимущества по сравнению с edvac эниак?

это бинарный код?

объясняется тем, что изобретение может первый цифровой компьютер строить?

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- давай уедем

- cortex thymi

- прибегать к хитростям

- чем мыть пол

- давай уедем

- Making things is another type of hobbies

- Твоя история интереснее чем эта статья

- наука о микроорганизмов

- hey babe u around

- PVG Ready to depart

- egy-care

- делай добро

- In the field of industry special emphasi

- have 2 starts with crustaceavores

- In the field of industry special emphasi

- до свиданья

- Receptacle arrives Omniva Tallin facilit

- But you should know I have been studying

- Каланын орталыгы Конаев кошесы

- Practically

- Is this rate MSC confirm for me? Are you

- ich stelle die sessel in das wohnzimmer.

- Мій батько інженер

- я замужем у меня двое детей

|

Pennsylvania Historical Marker |

|

Four ENIAC panels and one of its three function tables, on display at the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Pennsylvania |

|

| Location | University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science, 3330 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°57′08″N 75°11′26″W / 39.9523°N 75.1906°WCoordinates: 39°57′08″N 75°11′26″W / 39.9523°N 75.1906°W |

| Built/founded | 1945 |

| PHMC dedicated | Thursday, June 15, 2000 |

Glenn A. Beck (background) and Betty Snyder (foreground) program ENIAC in BRL building 328. (U.S. Army photo, c. 1947–1955)

ENIAC (; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer)[1][2] was the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945.[3][4] There were other computers that had combinations of these features, but the ENIAC had all of them in one package. It was Turing-complete and able to solve «a large class of numerical problems» through reprogramming.[5][6]

Although ENIAC was designed and primarily used to calculate artillery firing tables for the United States Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory (which later became a part of the Army Research Laboratory),[7][8] its first program was a study of the feasibility of the thermonuclear weapon.[9][10]

ENIAC was completed in 1945 and first put to work for practical purposes on December 10, 1945.[11]

ENIAC was formally dedicated at the University of Pennsylvania on February 15, 1946, having cost $487,000 (equivalent to $6,200,000 in 2021), and called a «Giant Brain» by the press.[citation needed] It had a speed on the order of one thousand times faster than that of electro-mechanical machines; this computational power, coupled with general-purpose programmability, excited scientists and industrialists alike. The combination of speed and programmability allowed for thousands more calculations for problems.[12]

ENIAC was formally accepted by the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps in July 1946. It was transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland in 1947, where it was in continuous operation until 1955.

Development and design[edit]

ENIAC’s design and construction was financed by the United States Army, Ordnance Corps, Research and Development Command, led by Major General Gladeon M. Barnes. The total cost was about $487,000, equivalent to $6,190,000 in 2021.[13] The construction contract was signed on June 5, 1943; work on the computer began in secret at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering[14] the following month, under the code name «Project PX», with John Grist Brainerd as principal investigator. Herman H. Goldstine persuaded the Army to fund the project, which put him in charge to oversee it for them.[15]

ENIAC was designed by Ursinus College physics professor John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert of the University of Pennsylvania, U.S.[16] The team of design engineers assisting the development included Robert F. Shaw (function tables), Jeffrey Chuan Chu (divider/square-rooter), Thomas Kite Sharpless (master programmer), Frank Mural (master programmer), Arthur Burks (multiplier), Harry Huskey (reader/printer) and Jack Davis (accumulators).[17] Significant development work was undertaken by the female mathematicians who handled the bulk of the ENIAC programming: Jean Jennings, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Betty Snyder, Frances Bilas, and Kay McNulty.[18] In 1946, the researchers resigned from the University of Pennsylvania and formed the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation.

ENIAC was a large, modular computer, composed of individual panels to perform different functions. Twenty of these modules were accumulators that could not only add and subtract, but hold a ten-digit decimal number in memory. Numbers were passed between these units across several general-purpose buses (or trays, as they were called). In order to achieve its high speed, the panels had to send and receive numbers, compute, save the answer and trigger the next operation, all without any moving parts. Key to its versatility was the ability to branch; it could trigger different operations, depending on the sign of a computed result.

Components[edit]

By the end of its operation in 1956, ENIAC contained 18,000 vacuum tubes, 7,200 crystal diodes, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors, and approximately 5,000,000 hand-soldered joints. It weighed more than 30 short tons (27 t), was roughly 8 ft × 3 ft × 100 ft (2 m × 1 m × 30 m) in size, occupied 1,800 sq ft (170 m2) and consumed 150 kW of electricity.[19][20] This power requirement led to the rumor that whenever the computer was switched on, lights in Philadelphia dimmed.[21] Input was possible from an IBM card reader and an IBM card punch was used for output. These cards could be used to produce printed output offline using an IBM accounting machine, such as the IBM 405. While ENIAC had no system to store memory in its inception, these punch cards could be used for external memory storage.[22] In 1953, a 100-word magnetic-core memory built by the Burroughs Corporation was added to ENIAC.[23]

ENIAC used ten-position ring counters to store digits; each digit required 36 vacuum tubes, 10 of which were the dual triodes making up the flip-flops of the ring counter. Arithmetic was performed by «counting» pulses with the ring counters and generating carry pulses if the counter «wrapped around», the idea being to electronically emulate the operation of the digit wheels of a mechanical adding machine.[24]

ENIAC had 20 ten-digit signed accumulators, which used ten’s complement representation and could perform 5,000 simple addition or subtraction operations between any of them and a source (e.g., another accumulator or a constant transmitter) per second. It was possible to connect several accumulators to run simultaneously, so the peak speed of operation was potentially much higher, due to parallel operation.[25][26]

Cpl. Irwin Goldstein (foreground) sets the switches on one of ENIAC’s function tables at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering. (U.S. Army photo)[27]

It was possible to wire the carry of one accumulator into another accumulator to perform arithmetic with double the precision, but the accumulator carry circuit timing prevented the wiring of three or more for even higher precision. ENIAC used four of the accumulators (controlled by a special multiplier unit) to perform up to 385 multiplication operations per second; five of the accumulators were controlled by a special divider/square-rooter unit to perform up to 40 division operations per second or three square root operations per second.

The other nine units in ENIAC were the initiating unit (started and stopped the machine), the cycling unit (used for synchronizing the other units), the master programmer (controlled loop sequencing), the reader (controlled an IBM punch-card reader), the printer (controlled an IBM card punch), the constant transmitter, and three function tables.[28][29]

Operation times[edit]

The references by Rojas and Hashagen (or Wilkes)[16] give more details about the times for operations, which differ somewhat from those stated above.

The basic machine cycle was 200 microseconds (20 cycles of the 100 kHz clock in the cycling unit), or 5,000 cycles per second for operations on the 10-digit numbers. In one of these cycles, ENIAC could write a number to a register, read a number from a register, or add/subtract two numbers.

A multiplication of a 10-digit number by a d-digit number (for d up to 10) took d+4 cycles, so a 10- by 10-digit multiplication took 14 cycles, or 2,800 microseconds—a rate of 357 per second. If one of the numbers had fewer than 10 digits, the operation was faster.

Division and square roots took 13(d+1) cycles, where d is the number of digits in the result (quotient or square root). So a division or square root took up to 143 cycles, or 28,600 microseconds—a rate of 35 per second. (Wilkes 1956:20[16] states that a division with a 10 digit quotient required 6 milliseconds.) If the result had fewer than ten digits, it was obtained faster.

ENIAC is able to process about 500 FLOPS,[30] compared to modern supercomputers’ petascale and exascale computing power.

Reliability[edit]

ENIAC used common octal-base radio tubes of the day; the decimal accumulators were made of 6SN7 flip-flops, while 6L7s, 6SJ7s, 6SA7s and 6AC7s were used in logic functions.[31] Numerous 6L6s and 6V6s served as line drivers to drive pulses through cables between rack assemblies.

Several tubes burned out almost every day, leaving ENIAC nonfunctional about half the time. Special high-reliability tubes were not available until 1948. Most of these failures, however, occurred during the warm-up and cool-down periods, when the tube heaters and cathodes were under the most thermal stress. Engineers reduced ENIAC’s tube failures to the more acceptable rate of one tube every two days. According to an interview in 1989 with Eckert, «We had a tube fail about every two days and we could locate the problem within 15 minutes.»[32]

In 1954, the longest continuous period of operation without a failure was 116 hours—close to five days.

Programming[edit]

ENIAC could be programmed to perform complex sequences of operations, including loops, branches, and subroutines. However, instead of the stored-program computers that exist today, ENIAC was just a large collection of arithmetic machines, which originally had programs set up into the machine[33] by a combination of plugboard wiring and three portable function tables (containing 1,200 ten-way switches each).[34] The task of taking a problem and mapping it onto the machine was complex, and usually took weeks. Due to the complexity of mapping programs onto the machine, programs were only changed after huge numbers of tests of the current program.[35] After the program was figured out on paper, the process of getting the program into ENIAC by manipulating its switches and cables could take days. This was followed by a period of verification and debugging, aided by the ability to execute the program step by step. A programming tutorial for the modulo function using an ENIAC simulator gives an impression of what a program on the ENIAC looked like.[36][37]

ENIAC’s six primary programmers, Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman, not only determined how to input ENIAC programs, but also developed an understanding of ENIAC’s inner workings.[38][39] The programmers were often able to narrow bugs down to an individual failed tube which could be pointed to for replacement by a technician.[40]

Programmers[edit]

Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Meltzer, Fran Bilas, and Ruth Lichterman were the first programmers of the ENIAC. They were not, as computer scientist and historian Kathryn Kleiman was once told, «refrigerator ladies», i.e., models posing in front of the machine for press photography.[41] Nevertheless, some of the women did not receive recognition for their work on the ENIAC in their lifetimes.[18] After the war ended, the women continued to work on the ENIAC. Their expertise made their positions difficult to replace with returning soldiers.[42]

These early programmers were drawn from a group of about two hundred women employed as computers at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. The job of computers was to produce the numeric result of mathematical formulas needed for a scientific study, or an engineering project. They usually did so with a mechanical calculator. The women studied the machine’s logic, physical structure, operation, and circuitry in order to not only understand the mathematics of computing, but also the machine itself.[18] This was one of the few technical job categories available to women at that time.[43] Betty Holberton (née Snyder) continued on to help write the first generative programming system (SORT/MERGE) and help design the first commercial electronic computers, the UNIVAC and the BINAC, alongside Jean Jennings.[44] McNulty developed the use of subroutines in order to help increase ENIAC’s computational capability.[45]

Herman Goldstine selected the programmers, whom he called operators, from the computers who had been calculating ballistics tables with mechanical desk calculators, and a differential analyzer prior to and during the development of ENIAC.[18] Under Herman and Adele Goldstine’s direction, the computers studied ENIAC’s blueprints and physical structure to determine how to manipulate its switches and cables, as programming languages did not yet exist. Though contemporaries considered programming a clerical task and did not publicly recognize the programmers’ effect on the successful operation and announcement of ENIAC,[18] McNulty, Jennings, Snyder, Wescoff, Bilas, and Lichterman have since been recognized for their contributions to computing.[46][47][48] Three of the current (2020) Army supercomputers Jean, Kay, and Betty are named for Jean Bartik (Betty Jennings), Kay McNulty, and Betty Snyder respectively.[49]

The «programmer» and «operator» job titles were not originally considered professions suitable for women. The labor shortage created by World War II helped enable the entry of women into the field.[18] However, the field was not viewed as prestigious, and bringing in women was viewed as a way to free men up for more skilled labor. Essentially, women were seen as meeting a need in a temporary crisis.[18] For example, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics said in 1942, «It is felt that enough greater return is obtained by freeing the engineers from calculating detail to overcome any increased expenses in the computers’ salaries. The engineers admit themselves that the girl computers do the work more rapidly and accurately than they would. This is due in large measure to the feeling among the engineers that their college and industrial experience is being wasted and thwarted by mere repetitive calculation».[18]

Following the initial six programmers, an expanded team of a hundred scientists was recruited to continue work on the ENIAC. Among these were several women, including Gloria Ruth Gordon.[50] Adele Goldstine wrote the original technical description of the ENIAC.[51]

Programming languages[edit]

Several language systems were developed to describe programs for the ENIAC, including:

| Year | Name | Chief developers |

|---|---|---|

| 1943–46 | ENIAC coding system | John von Neumann, John Mauchly, J. Presper Eckert, Herman Goldstine after Alan Turing. |

| 1946 | ENIAC Short Code | Richard Clippinger, John von Neumann after Alan Turing |

| 1946 | Von Neumann and Goldstine graphing system (Notation) | John von Neumann and Herman Goldstine |

| 1947 | ARC Assembly | Kathleen Booth[52][53] |

| 1948 | Curry notation system | Haskell Curry |

Role in the hydrogen bomb[edit]

Although the Ballistic Research Laboratory was the sponsor of ENIAC, one year into this three-year project John von Neumann, a mathematician working on the hydrogen bomb at Los Alamos National Laboratory, became aware of this computer.[54] Los Alamos subsequently became so involved with ENIAC that the first test problem run consisted of computations for the hydrogen bomb, not artillery tables.[8] The input/output for this test was one million cards.[55]

Role in development of the Monte Carlo methods[edit]

Related to ENIAC’s role in the hydrogen bomb was its role in the Monte Carlo method becoming popular. Scientists involved in the original nuclear bomb development used massive groups of people doing huge numbers of calculations («computers» in the terminology of the time) to investigate the distance that neutrons would likely travel through various materials. John von Neumann and Stanislaw Ulam realized the speed of ENIAC would allow these calculations to be done much more quickly.[56] The success of this project showed the value of Monte Carlo methods in science.[57]

Later developments[edit]

A press conference was held on February 1, 1946,[18] and the completed machine was announced to the public the evening of February 14, 1946,[58] featuring demonstrations of its capabilities. Elizabeth Snyder and Betty Jean Jennings were responsible for developing the demonstration trajectory program, although Herman and Adele Goldstine took credit for it.[18] The machine was formally dedicated the next day[59] at the University of Pennsylvania. None of the women involved in programming the machine or creating the demonstration were invited to the formal dedication nor to the celebratory dinner held afterwards.[60]

The original contract amount was $61,700; the final cost was almost $500,000 (approximately equivalent to $8,000,000 in 2021). It was formally accepted by the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps in July 1946. ENIAC was shut down on November 9, 1946, for a refurbishment and a memory upgrade, and was transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland in 1947. There, on July 29, 1947, it was turned on and was in continuous operation until 11:45 p.m. on October 2, 1955.[2]

Role in the development of the EDVAC[edit]

A few months after ENIAC’s unveiling in the summer of 1946, as part of «an extraordinary effort to jump-start research in the field»,[61] the Pentagon invited «the top people in electronics and mathematics from the United States and Great Britain»[61] to a series of forty-eight lectures given in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; all together called The Theory and Techniques for Design of Digital Computers—more often named the Moore School Lectures.[61] Half of these lectures were given by the inventors of ENIAC.[62]

ENIAC was a one-of-a-kind design and was never repeated. The freeze on design in 1943 meant that it lacked some innovations that soon became well-developed, notably the ability to store a program. Eckert and Mauchly started work on a new design, to be later called the EDVAC, which would be both simpler and more powerful. In particular, in 1944 Eckert wrote his description of a memory unit (the mercury delay line) which would hold both the data and the program. John von Neumann, who was consulting for the Moore School on the EDVAC, sat in on the Moore School meetings at which the stored program concept was elaborated. Von Neumann wrote up an incomplete set of notes (First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC) which were intended to be used as an internal memorandum—describing, elaborating, and couching in formal logical language the ideas developed in the meetings. ENIAC administrator and security officer Herman Goldstine distributed copies of this First Draft to a number of government and educational institutions, spurring widespread interest in the construction of a new generation of electronic computing machines, including Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) at Cambridge University, England and SEAC at the U.S. Bureau of Standards.[63]

Improvements[edit]

A number of improvements were made to ENIAC after 1947, including a primitive read-only stored programming mechanism using the function tables as program ROM,[63][64][65] after which programming was done by setting the switches.[66] The idea has been worked out in several variants by Richard Clippinger and his group, on the one hand, and the Goldstines, on the other,[67] and it was included in the ENIAC patent.[68] Clippinger consulted with von Neumann on what instruction set to implement.[63][69][70] Clippinger had thought of a three-address architecture while von Neumann proposed a one-address architecture because it was simpler to implement. Three digits of one accumulator (#6) were used as the program counter, another accumulator (#15) was used as the main accumulator, a third accumulator (#8) was used as the address pointer for reading data from the function tables, and most of the other accumulators (1–5, 7, 9–14, 17–19) were used for data memory.

In March 1948 the converter unit was installed,[71] which made possible programming through the reader from standard IBM cards.[72][73] The «first production run» of the new coding techniques on the Monte Carlo problem followed in April.[71][74] After ENIAC’s move to Aberdeen, a register panel for memory was also constructed, but it did not work. A small master control unit to turn the machine on and off was also added.[75]

The programming of the stored program for ENIAC was done by Betty Jennings, Clippinger, Adele Goldstine and others.[76][64][63] It was first demonstrated as a stored-program computer in April 1948,[77] running a program by Adele Goldstine for John von Neumann. This modification reduced the speed of ENIAC by a factor of 6 and eliminated the ability of parallel computation, but as it also reduced the reprogramming time[70][63] to hours instead of days, it was considered well worth the loss of performance. Also analysis had shown that due to differences between the electronic speed of computation and the electromechanical speed of input/output, almost any real-world problem was completely I/O bound, even without making use of the original machine’s parallelism. Most computations would still be I/O bound, even after the speed reduction imposed by this modification.

Early in 1952, a high-speed shifter was added, which improved the speed for shifting by a factor of five. In July 1953, a 100-word expansion core memory was added to the system, using binary-coded decimal, excess-3 number representation. To support this expansion memory, ENIAC was equipped with a new Function Table selector, a memory address selector, pulse-shaping circuits, and three new orders were added to the programming mechanism.[63]

Comparison with other early computers[edit]

Mechanical computing machines have been around since Archimedes’ time (see: Antikythera mechanism), but the 1930s and 1940s are considered the beginning of the modern computer era.

ENIAC was, like the IBM Harvard Mark I and the German Z3, able to run an arbitrary sequence of mathematical operations, but did not read them from a tape. Like the British Colossus, it was programmed by plugboard and switches. ENIAC combined full, Turing-complete programmability with electronic speed. The Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC), ENIAC, and Colossus all used thermionic valves (vacuum tubes). ENIAC’s registers performed decimal arithmetic, rather than binary arithmetic like the Z3, the ABC and Colossus.

Like the Colossus, ENIAC required rewiring to reprogram until April 1948.[78] In June 1948, the Manchester Baby ran its first program and earned the distinction of first electronic stored-program computer.[79][80][81] Though the idea of a stored-program computer with combined memory for program and data was conceived during the development of ENIAC, it was not initially implemented in ENIAC because World War II priorities required the machine to be completed quickly, and ENIAC’s 20 storage locations would be too small to hold data and programs.

Public knowledge[edit]

The Z3 and Colossus were developed independently of each other, and of the ABC and ENIAC during World War II. Work on the ABC at Iowa State University was stopped in 1942 after John Atanasoff was called to Washington, D.C., to do physics research for the U.S. Navy, and it was subsequently dismantled.[82] The Z3 was destroyed by the Allied bombing raids of Berlin in 1943. As the ten Colossus machines were part of the UK’s war effort their existence remained secret until the late 1970s, although knowledge of their capabilities remained among their UK staff and invited Americans. ENIAC, by contrast, was put through its paces for the press in 1946, «and captured the world’s imagination». Older histories of computing may therefore not be comprehensive in their coverage and analysis of this period. All but two of the Colossus machines were dismantled in 1945; the remaining two were used to decrypt Soviet messages by GCHQ until the 1960s.[83][84] The public demonstration for ENIAC was developed by Snyder and Jennings who created a demo that would calculate the trajectory of a missile in 15 seconds, a task that would have taken several weeks for a human computer.[45]

Patent[edit]

For a variety of reasons – including Mauchly’s June 1941 examination of the Atanasoff–Berry computer (ABC), prototyped in 1939 by John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry – U.S. Patent 3,120,606 for ENIAC, applied for in 1947 and granted in 1964, was voided by the 1973[85] decision of the landmark federal court case Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp.. The decision included: that the ENIAC inventors had derived the subject matter of the electronic digital computer from Atanasoff; gave legal recognition to Atanasoff as the inventor of the first electronic digital computer; and put the invention of the electronic digital computer in the public domain.

Main parts[edit]

The bottoms of three accumulators at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, US

A function table from ENIAC on display at Aberdeen Proving Ground museum.

The main parts were 40 panels and three portable function tables (named A, B, and C). The layout of the panels was (clockwise, starting with the left wall):

- Left wall

- Initiating Unit

- Cycling Unit

- Master Programmer – panel 1 and 2

- Function Table 1 – panel 1 and 2

- Accumulator 1

- Accumulator 2

- Divider and Square Rooter

- Accumulator 3

- Accumulator 4

- Accumulator 5

- Accumulator 6

- Accumulator 7

- Accumulator 8

- Accumulator 9

- Back wall

- Accumulator 10

- High-speed Multiplier – panel 1, 2, and 3

- Accumulator 11

- Accumulator 12

- Accumulator 13

- Accumulator 14

- Right wall

- Accumulator 15

- Accumulator 16

- Accumulator 17

- Accumulator 18

- Function Table 2 – panel 1 and 2

- Function Table 3 – panel 1 and 2

- Accumulator 19

- Accumulator 20

- Constant Transmitter – panel 1, 2, and 3

- Printer – panel 1, 2, and 3

An IBM card reader was attached to Constant Transmitter panel 3 and an IBM card punch was attached to Printer Panel 2. The Portable Function Tables could be connected to Function Table 1, 2, and 3.[86]

Parts on display[edit]

Detail of the back of a section of ENIAC, showing vacuum tubes

Pieces of ENIAC are held by the following institutions:

- The School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Pennsylvania has four of the original forty panels (Accumulator #18, Constant Transmitter Panel 2, Master Programmer Panel 2, and the Cycling Unit) and one of the three function tables (Function Table B) of ENIAC (on loan from the Smithsonian).[86]

- The Smithsonian has five panels (Accumulators 2, 19, and 20; Constant Transmitter panels 1 and 3; Divider and Square Rooter; Function Table 2 panel 1; Function Table 3 panel 2; High-speed Multiplier panels 1 and 2; Printer panel 1; Initiating Unit)[86] in the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.[18] (but apparently not currently on display).

- The Science Museum in London has a receiver unit on display.

- The Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California has three panels (Accumulator #12, Function Table 2 panel 2, and Printer Panel 3) and portable function table C on display (on loan from the Smithsonian Institution).[86]

- The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor has four panels (two accumulators, High-speed Multiplier panel 3, and Master Programmer panel 2),[86] salvaged by Arthur Burks.

- The United States Army Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, where ENIAC was used, has Portable Function Table A.

- The U.S. Army Field Artillery Museum in Fort Sill, as of October 2014, obtained seven panels of ENIAC that were previously housed by The Perot Group in Plano, Texas.[87] There are accumulators #7, #8, #11, and #17;[88] panel #1 and #2 that connected to function table #1,[86] and the back of a panel showing its tubes. A module of tubes is also on display.

- The United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, has one of the data entry terminals from the ENIAC.

- The Heinz Nixdorf Museum in Paderborn, Germany, has three panels (Printer panel 2 and High-speed Function Table)[86] (on loan from the Smithsonian Institution). In 2014 the museum decided to rebuild one of the accumulator panels – reconstructed part has the look and feel of a simplified counterpart from the original machine.[89][90]

Recognition[edit]

ENIAC was named an IEEE Milestone in 1987.[91]

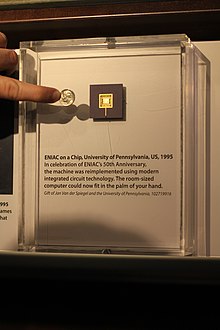

ENIAC on a Chip, University of Pennsylvania (1995) — Computer History Museum

In 1996, in honor of the ENIAC’s 50th anniversary, The University of Pennsylvania sponsored a project named, «ENIAC-on-a-Chip«, where a very small silicon computer chip measuring 7.44 mm by 5.29 mm was built with the same functionality as ENIAC. Although this 20 MHz chip was many times faster than ENIAC, it had but a fraction of the speed of its contemporary microprocessors in the late 1990s.[92][93][94]

In 1997, the six women who did most of the programming of ENIAC were inducted into the Technology International Hall of Fame.[46][95] The role of the ENIAC programmers is treated in a 2010 documentary film titled Top Secret Rosies: The Female «Computers» of WWII by LeAnn Erickson.[47] A 2014 documentary short, The Computers by Kate McMahon, tells of the story of the six programmers; this was the result of 20 years’ research by Kathryn Kleiman and her team as part of the ENIAC Programmers Project.[48][96] In 2022 Grand Central Publishing released Proving Ground by Kathy Kleiman, a hardcover biography about the six ENIAC programmers and their efforts to translate block diagrams and electronic schematics of the ENIAC, then under construction, into programs that would be loaded into and run on ENIAC once it was available for use.[97]

In 2011, in honor of the 65th anniversary of the ENIAC’s unveiling, the city of Philadelphia declared February 15 as ENIAC Day.[98]

The ENIAC celebrated its 70th anniversary on February 15, 2016.[99]

See also[edit]

- History of computing

- History of computing hardware

- Women in computing

- List of vacuum-tube computers

- Military computers

- Unisys

- Arthur Burks

- Betty Holberton

- Frances Bilas Spence

- John Mauchly

- J. Presper Eckert

- Jean Jennings Bartik

- Kathleen Antonelli (Kay McNulty)

- Marlyn Meltzer

- Ruth Lichterman Teitelbaum

Notes[edit]

- ^ Eckert Jr., John Presper and Mauchly, John W.; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, United States Patent Office, US Patent 3,120,606, filed 1947-06-26, issued 1964-02-04; invalidated 1973-10-19 after court ruling in Honeywell v. Sperry Rand.

- ^ a b Weik, Martin H. «The ENIAC Story». Ordnance. Washington, DC: American Ordnance Association (January–February 1961). Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ «3.2 First Generation Electronic Computers (1937-1953)». www.phy.ornl.gov.

- ^ «ENIAC on Trial – 1. Public Use». www.ushistory.org. Search for 1945. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

The ENIAC machine […] was reduced to practice no later than the date of commencement of the use of the machine for the Los Alamos calculations, December 10, 1945.

- ^ Goldstine & Goldstine 1946, p. 97

- ^ Shurkin, Joel (1996). Engines of the mind: the evolution of the computer from mainframes to microprocessors. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31471-7.

- ^ Moye, William T. (January 1996). «ENIAC: The Army-Sponsored Revolution». US Army Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Goldstine 1972, p. 214.

- ^ Richard Rhodes (1995). «chapter 13». Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. p. 251.

The first problem assigned to the first working electronic digital computer in the world was the hydrogen bomb. […] The ENIAC ran a first rough version of the thermonuclear calculations for six weeks in December 1945 and January 1946.

- ^ McCartney 1999, p. 103: «ENIAC correctly showed that Teller’s scheme would not work, but the results led Teller and Ulam to come up with another design together.»

- ^ *«ENIAC on Trial – 1. Public Use». www.ushistory.org. Search for 1945. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

The ENIAC machine […] was reduced to practice no later than the date of commencement of the use of the machine for the Los Alamos calculations, December 10, 1945.

- ^ «ENIAC USA 1946». The History of Computing Project. History of Computing Foundation. March 13, 2013. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021.

- ^ Dalakov, Georgi. «ENIAC». History of Computers. Georgi Dalakov. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ Goldstine & Goldstine 1946

- ^ Gayle Ronan Sims (June 22, 2004). «Herman Heine Goldstine». Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 30, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2017 – via www.princeton.edu.

- ^ a b c Wilkes, M. V. (1956). Automatic Digital Computers. New York: John Wiley & Sons. QA76.W5 1956.

- ^ «ENIAC on Trial». USHistory.org. Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Light 1999.

- ^ «ENIAC». The Free Dictionary. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (December 1955). Ballistic Research Laboratories Report No. 971: A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems. Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD: United States Department of Commerce Office of Technical Services. p. 41. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Farrington, Gregory (March 1996). ENIAC: Birth of the Information Age. Popular Science. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ «ENIAC in Action: What it Was and How it Worked». ENIAC: Celebrating Penn Engineering History. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Martin, Jason (December 17, 1998). «Past and Future Developments in Memory Design». Past and Future Developments in Memory Design. University of Maryland. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Peddie, Jon (June 13, 2013). The History of Visual Magic in Computers: How Beautiful Images are Made in CAD, 3D, VR and AR. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4471-4932-3.

- ^ Goldstine & Goldstine 1946.

- ^ Igarashi, Yoshihide; Altman, Tom; Funada, Mariko; Kamiyama, Barbara (May 27, 2014). Computing: A Historical and Technical Perspective. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-2741-3.

- ^ The original photo can be seen in the article: Rose, Allen (April 1946). «Lightning Strikes Mathematics». Popular Science: 83–86. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Clippinger 1948, Section I: General Description of the ENIAC – The Function Tables.

- ^ Goldstine 1946.

- ^ «The incredible evolution of supercomputers’ powers, from 1946 to today». Popular Science. March 18, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Burks 1947, pp. 756–767

- ^ Randall 5th, Alexander (February 14, 2006). «A lost interview with ENIAC co-inventor J. Presper Eckert». Computer World. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Grier, David (July–September 2004). «From the Editor’s Desk». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 26 (3): 2–3. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2004.9. S2CID 7822223.

- ^ Cruz, Frank (November 9, 2013). «Programming the ENIAC». Programming the ENIAC. Columbia University. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Alt, Franz (July 1972). «Archaeology of computers: reminiscences, 1945-1947». Communications of the ACM. 15 (7): 693–694. doi:10.1145/361454.361528. S2CID 28565286.

- ^ Schapranow, Matthieu-P. (June 1, 2006). «ENIAC tutorial — the modulo function». Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Description of Lehmer’s program computing the exponent of modulo 2 prime

- De Mol & Bullynck 2008

- ^ «ENIAC Programmers Project». eniacprogrammers.org. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Donaldson James, Susan (December 4, 2007). «First Computer Programmers Inspire Documentary». ABC News. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Fritz, W. Barkley (1996). «The Women of ENIAC» (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 18 (3): 13–28. doi:10.1109/85.511940. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ «Meet the ‘Refrigerator Ladies’ Who Programmed the ENIAC». Mental Floss. October 13, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ «ENIAC Programmers: A History of Women in Computing». Atomic Spin. July 31, 2016.

- ^ Grier, David (2007). When Computers Were Human. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849369. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ Beyer, Kurt (2012). Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age. London, Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780262517263.

- ^ a b Isaacson, Walter (September 18, 2014). «Walter Isaacson on the Women of ENIAC». Fortune. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ a b «Invisible Computers: The Untold Story of the ENIAC Programmers». Witi.com. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Gumbrecht, Jamie (February 2011). «Rediscovering WWII’s female ‘computers’«. CNN. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ a b «Festival 2014: The Computers». SIFF. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ «Army researchers acquire two new supercomputers». U.S. Army DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory Public Affairs. December 28, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (July 26, 2009). «Gloria Gordon Bolotsky, 87; Programmer Worked on Historic ENIAC Computer». The Washington Post. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ «ARL Computing History | U.S. Army Research Laboratory». Arl.army.mil. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Booth, Kathleen. «Machine Language for Automatic Relay Computer». Birkbeck College Computation Laboratory. University of London.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin «The Development of Computer Programming in Britain (1945 to 1955)», The Birkbeck College Machines, in (1982) Annals of the History of Computing 4(2) April 1982 IEEE

- ^ Goldstine 1972, p. 182

- ^ Goldstine 1972, p. 226

- ^ Mazhdrakov, Metodi; Benov, Dobriyan; Valkanov, Nikolai (2018). The Monte Carlo Method. Engineering Applications. ACMO Academic Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-619-90684-3-4.

- ^ Kean, Sam (2010). The Disappearing Spoon. New York: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-0-316-05163-7.

- ^ Kennedy, T. R. Jr. (February 15, 1946). «Electronic Computer Flashes Answers». New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp., 180 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 673, p. 20, finding 1.1.3 (U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, Fourth Division 1973) («The ENIAC machine which embodied ‘the invention’ claimed by the ENIAC patent was in public use and non-experimental use for the following purposes, and at times prior to the critical date: … Formal dedication use February 15, 1946 …»).

- ^ Evans, Claire L. (March 6, 2018). Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. Penguin. p. 51. ISBN 9780735211766.

- ^ a b c McCartney 1999, p. 140

- ^ McCartney 1999, p. 140: «Eckert gave eleven lectures, Mauchly gave six, Goldstine gave six. von Neumann, who was to give one lecture, didn’t show up; the other 24 were spread among various invited academics and military officials.»

- ^ a b c d e f «Eniac». Epic Technology for Great Justice. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Goldstine 1947.

- ^

- Goldstine 1972, pp. 233–234, 270, search string: «eniac Adele 1947»

- By July 1947 von Neumann was writing: «I am much obliged to Adele for her letters. Nick and I are working with her new code, and it seems excellent.»

- Clippinger 1948, Section IV: Summary of Orders

- Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, pp. 44–48

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). «Notes to Pages 132-135». Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology. MIT Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780262161473.

- ^ Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, p. 44.

- ^ Clippinger 1948, INTRODUCTION.

- ^ a b Goldstine 1972, 233-234, 270; search string: eniac Adele 1947.

- ^ a b Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Clippinger 1948, Section VIII: Modified ENIAC.

- ^ Fritz, W. Barkley (1949). «Description and Use of the ENIAC Converter Code». Technical Note (141). Section 1. – Introduction, p. 1.

At present it is controlled by a code which incorporates a unit called the Converter as a basic part of its operation, hence the name ENIAC Converter Code. These code digits are brought into the machine either through the Reader from standard IBM cards*or from the Function Tables (…). (…) *The card control method of operation is used primarily for testing and the running of short highly iterative problems and is not discussed in this report.

- ^ Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (July–September 2014c). «Los Alamos Bets On ENIAC: Nuclear Monte Carlo Simulations 1947-48». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 36 (3): 42–63. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2014.40. S2CID 17470931. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2016, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Clippinger 1948, INTRODUCTION

- Full names: Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, p. 44

- ^ Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2016, p. 153.

- ^ See #Improvements

- ^ «Programming the ENIAC: an example of why computer history is hard | @CHM Blog». Computer History Museum. May 18, 2016.

- ^ Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (January–March 2014a). «Reconsidering the Stored Program Concept». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 36 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1109/mahc.2013.56. S2CID 18827916.

- ^ Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014b, pp. 48–54.

- ^ Copeland 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Copeland 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Ward, Mark (May 5, 2014), «How GCHQ built on a colossal secret», BBC News

- ^ «Atanasoff-Berry Computer Court Case». Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2016, pp. 46, 264.

- ^ Meador, Mitch (October 29, 2014). «ENIAC: First Generation Of Computation Should Be A Big Attraction At Sill». The Lawton Constitution. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Haigh. et al. list accumulators 7, 8, 13, and 17, but 2018 photos show 7, 8, 11, and 17.[full citation needed]

- ^ «Meet the iPhone’s 30-ton ancestor: Inside the project to rebuild one of the first computers». TechRepublic. November 23, 2016. Bringing the Eniac back to life.

- ^ «ENIAC – Life-size model of the first vacuum-tube computer». Germany: Heinz Nixdorf Museum. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ «Milestones:Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, 1946». IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ «Looking Back At ENIAC: Commemorating A Half-Century Of Computers In The Reviewing System». The Scientist Magazine.

- ^ Van Der Spiegel, Jan (1996). «ENIAC-on-a-Chip». PENN PRINTOUT. Vol. 12, no. 4. The University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Van Der Spiegel, Jan (May 9, 1995). «ENIAC-on-a-Chip». University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ Brown, Janelle (May 8, 1997). «Wired: Women Proto-Programmers Get Their Just Reward». Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ «ENIAC Programmers Project». ENIAC Programmers Project. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Kleiman, Kathy (July 2022). Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5387-1828-5.

- ^ «Resolution No. 110062: Declaring February 15 as «Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) Day» in Philadelphia and honoring the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Sciences» (PDF). February 10, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Kim, Meeri (February 11, 2016). «70 years ago, six Philly women became the world’s first digital computer programmers». Retrieved October 17, 2016 – via www.phillyvoice.com.

References[edit]

- Burks, Arthur (1947). «Electronic Computing Circuits of the ENIAC». Proceedings of the I.R.E. 35 (8): 756–767. doi:10.1109/jrproc.1947.234265.

- Burks, Arthur; Burks, Alice R. (1981). «The ENIAC: The First General-Purpose Electronic Computer». Annals of the History of Computing. 3 (4): 310–389. doi:10.1109/mahc.1981.10043. S2CID 14205498.

- Clippinger, R. F. (September 29, 1948). Source. «A Logical Coding System Applied to the ENIAC». Ballistic Research Laboratories Report (673). Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- Copeland, B. Jack, ed. (2006), Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park’s Codebreaking Computers, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4

- De Mol, Liesbeth; Bullynck, Maarten (2008). «A Week-End Off: The First Extensive Number-Theoretical Computation on ENIAC». In Beckmann, Arnold; Dimitracopoulos, Costas; Löwe, Benedikt (eds.). Logic and Theory of Algorithms: 4th Conference on Computability in Europe, CiE 2008 Athens, Greece, June 15-20, 2008, Proceedings. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 158–167. ISBN 9783540694052.

- Eckert, J. Presper, The ENIAC (in Nicholas Metropolis, J. Howlett, Gian-Carlo Rota, (editors), A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century, Academic Press, New York, 1980, pp. 525–540)

- Eckert, J. Presper and John Mauchly, 1946, Outline of plans for development of electronic computers, 6 pages. (The founding document in the electronic computer industry.)

- Fritz, W. Barkley, The Women of ENIAC (in IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 18, 1996, pp. 13–28)

- Goldstine, Adele (1946). Source. «A Report on the ENIAC». FTP.arl.mil. 1 (1). Chapter 1 — Introduction: 1.1.2. The Units of the ENIAC.

- Goldstine, H. H.; Goldstine, Adele (1946). «The electronic numerical integrator and computer (ENIAC)». Mathematics of Computation. 2 (15): 97–110. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1946-0018977-0. ISSN 0025-5718. (also reprinted in The Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1982, pp. 359–373)

- Goldstine, Adele K. (July 10, 1947). Central Control for ENIAC. p. 1.

Unlike the later 60- and 100-order codes this one [51 order code] required no additions to ENIAC’s original hardware. It would have worked more slowly and offered a more restricted range of instructions but the basic structure of accumulators and instructions changed only slightly.

- Goldstine, Herman H. (1972). The Computer: from Pascal to von Neumann. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02367-0.

- Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (April–June 2014b). «Engineering ‘The Miracle of the ENIAC’: Implementing the Modern Code Paradigm». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 36 (2): 41–59. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2014.15. S2CID 24359462. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (2016). ENIAC in Action: Making and Remaking the Modern Computer. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53517-5.

- Light, Jennifer S. (1999). «When Computers Were Women» (PDF). Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483. doi:10.1353/tech.1999.0128. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 25147356. S2CID 108407884. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Mauchly, John, The ENIAC (in Metropolis, Nicholas, Howlett, Jack; Rota, Gian-Carlo. 1980, A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century, Academic Press, New York, ISBN 0-12-491650-3, pp. 541–550, «Original versions of these papers were presented at the International Research Conference on the History of Computing, held at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, 10–15 June 1976.»)

- McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC: The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker & Co. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- Rojas, Raúl; Hashagen, Ulf, editors. The First Computers: History and Architectures, 2000, MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-18197-5

- Stuart, Brian L. (2018). «Simulating the ENIAC [Scanning Our Past]». Proceedings of the IEEE. 106 (4): 761–772. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2018.2813678.

- Stuart, Brian L. (2018). «Programming the ENIAC [Scanning Our Past]». Proceedings of the IEEE. 106 (9): 1760–1770. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2018.2843998.

- Stuart, Brian L. (2018). «Debugging the ENIAC [Scanning Our Past]». Proceedings of the IEEE. 106 (12): 2331–2345. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2018.2878986.

Further reading[edit]

- Berkeley, Edmund. GIANT BRAINS or machines that think. John Wiley & Sons, inc., 1949. Chapter 7 Speed – 5000 Additions a Second: Moore School’s ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer)

- Dyson, George (2012). Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42277-5.

- Gumbrecht, Jamie (February 8, 2011). «Rediscovering WWII’s ‘computers’«. CNN.com. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- Hally, Mike. Electronic Brains: Stories from the Dawn of the Computer Age, Joseph Henry Press, 2005. ISBN 0-309-09630-8

- Lukoff, Herman (1979). From Dits to Bits: A personal history of the electronic computer. Portland, OR: Robotics Press. ISBN 978-0-89661-002-6. LCCN 79-90567.

- Tompkins, C. B.; Wakelin, J. H.; High-Speed Computing Devices, McGraw-Hill, 1950.

- Stern, Nancy (1981). From ENIAC to UNIVAC: An Appraisal of the Eckert–Mauchly Computers. Digital Press. ISBN 978-0-932376-14-5.

- «ENIAC Operating Manual» (PDF). www.bitsavers.org.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to ENIAC.

- ENIAC simulation

- Another ENIAC simulation

- Pulse-level ENIAC simulator

- 3D printable model of the ENIAC

- Q&A: A lost interview with ENIAC co-inventor J. Presper Eckert

- Interview with Eckert Transcript of a video interview with Eckert by David Allison for the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution on February 2, 1988. An in-depth, technical discussion on ENIAC, including the thought process behind the design.

- Oral history interview with J. Presper Eckert, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Eckert, a co-inventor of ENIAC, discusses its development at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering; describes difficulties in securing patent rights for ENIAC and the problems posed by the circulation of John von Neumann’s 1945 First Draft of the Report on EDVAC, which placed the ENIAC inventions in the public domain. Interview by Nancy Stern, 28 October 1977.

- Oral history interview with Carl Chambers, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Chambers discusses the initiation and progress of the ENIAC project at the University of Pennsylvania Moore School of Electrical Engineering (1941–46). Oral history interview by Nancy B. Stern, 30 November 1977.

- Oral history interview with Irven A. Travis, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Travis describes the ENIAC project at the University of Pennsylvania (1941–46), the technical and leadership abilities of chief engineer Eckert, the working relations between John Mauchly and Eckert, the disputes over patent rights, and their resignation from the university. Oral history interview by Nancy B. Stern, 21 October 1977.

- Oral history interview with S. Reid Warren, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Warren served as supervisor of the EDVAC project; central to his discussion are J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly and their disagreements with administrators over patent rights; discusses John von Neumann’s 1945 draft report on the EDVAC, and its lack of proper acknowledgment of all the EDVAC contributors.

- ENIAC Programmers Project

- The women of ENIAC

- Programming ENIAC

- How ENIAC took a Square Root

- Mike Muuss: Collected ENIAC documents

- ENIAC chapter in Karl Kempf, Electronic Computers Within The Ordnance Corps, November 1961

- The ENIAC Story, Martin H. Weik, Ordnance Ballistic Research Laboratories, 1961

- ENIAC museum at the University of Pennsylvania

- ENIAC specifications from Ballistic Research Laboratories Report No. 971 December 1955, (A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems)

- A Computer Is Born, Michael Kanellos, 60th anniversary news story, CNet, February 13, 2006

- 1946 film restored, Computer History Archives Project

ЭНИАК (Электронный числовой интегратор и вычислитель — англ. ENIAC, сокр. от Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) — первый электронный цифровой вычислитель общего назначения, который можно было перепрограммировать для решения широкого спектра задач.

История компьютера ENIAC началась в 1930-х, когда американский профессор Джон Мокли захотел предсказывать погоду не на недели, а на годы вперёд. Он считал, что для этого нужно разгадать закономерности вспышек и пятен на Солнце.

У профессора были данные наблюдений метеорологов за много лет. Чтобы проанализировать их, он купил у банков списанные калькуляторы и усадил за работу студентов. Но вычисления шли медленно — информации было много, а студенты часто ошибались.

Мокли понял: чтобы ускорить работу, нужно мощное вычислительное устройство. Тогда он начал разрабатывать машину на радиолампах, которая выдавала бы результат сразу после ввода информации. Но собрать её изобретатель не мог — у него не хватало денег.

Часть идей проекта могла быть позаимствована из предложения 1940 года, сделанного Ирвеном Трэвисом. Именно Трэвис участвовал в подписании договора на использование школой Мура анализатора в 1933 году, а в 1940-м он предложил улучшенную версию анализатора, хотя и не электронного, но работавшего на цифровом принципе. Он должен был использовать механические счётчики вместо аналоговых колёс. К 1943 году он ушёл из школы Мура и занял пост в руководстве флотом в Вашингтоне.

В 1941 году Мокли начал преподавать в инженерной школе при университете. Там он познакомился с изобретателем Джоном Эккертом, которого тоже увлекла идея создать электронный компьютер.

Разработка компьютера ENIAC была начата в 1942 году, в Электротехнической школе Мура, штат Пенсильвания. Ожидалось, что он сможет облегчить работу женщинам, которые вручную рассчитывали траектории полета баллистических ракет и других снарядов. Им нужно было учитывать положение огнестрельного оружия, силу ветра, температуру воздуха, скорость снаряда и многие другие параметры. Военным нужно было знать около 3000 траекторий полета снаряда. На расчет каждой из траекторий требовалось выполнить около 1000 операций. На это у каждой женщины уходило около 16 дней. В результате этих вычислений составлялись так называемые таблицы стрельбы, при помощи которых военные могли точно попадать по вражеским целям.

В августе 1942 года Мокли написал 7-страничный документ «The Use of High-Speed Vacuum Tube Devices for Calculation», в котором предлагал Институту построить электронную вычислительную машину, основанную на электронных лампах. Руководство Института работу не оценило и сдало документ в архив, где он вообще был утерян.

В 1942 году союзники высадились в Северной Африке и артиллеристам понадобились баллистические таблицы под местный климат.

Один из физиков Манхэттенского проекта, Эдвард Теллер, ещё в 1942 году загорелся идеей «супероружия»: гораздо более разрушительного, чем то, что позже сбрасывали на Японию, с энергией взрыва, поступавшей от атомного синтеза, а не от деления ядер. Теллер считал, что он сможет запустить цепную реакцию синтеза в смеси дейтерия (обычный водород с дополнительным нейтроном) и трития (обычный водород с двумя дополнительными нейтронами). Но для этого нужно было обойтись низким содержанием трития, поскольку он был чрезвычайно редким.

Создание компьютера ENIAC было начато в 1942 году в одной из лабораторий Пенсильванского университета по заказу американского армейского Отдела артиллерии и Баллистической научно-исследовательской лаборатории в рамках проекта «Project PX».

Одна из первых вычислительных машин была создана в 1943, но задокументированно данное создание лишь после окончания военных действий в 1946 году.

В апреле 1943 Моучли, Эккерт и Брэйнерд сделали черновик «Отчёта по электронному дифференциальному анализатору». Это привлекло в их ряды ещё одного союзника, Германа Голдстайна, математика и армейского офицера, служившего посредником между Абердином и школой Мура. С помощью Голдстайна группа представила идею комитету в BRL, и получила военный грант, с Брэйнердом в качестве научного руководителя проекта. Им нужно было закончить создание машины к сентябрю 1944 года с бюджетом в $150 000. Команда назвала проект ENIAC: Electronic Numerical Integrator, Analyzer and Computer (Электронный числовой интегратор и вычислитель).

В апреле 1943 года Мокли по совету знакомых подал заявку на выделение средств напрямую в баллистическую лабораторию. Он обещал, что построенный компьютер будет вычислять одну траекторию за пять минут.

Лишь в начале 1943 года один из работников Института в случайной беседе сообщил Голдстайну об идее электронного вычислителя, с которой носился Мокли. Использование электронной вычислительной машины позволило бы лаборатории сократить время расчёта с нескольких месяцев до нескольких часов. Голдстайн встретился с Мокли и предложил ему обратиться с заявкой в лабораторию на выделение средств для постройки задуманной машины. Мокли по памяти восстановил утерянный 7-страничный документ с описанием проекта.

Архитектуру компьютера начали разрабатывать в 1943 году Джон Преспер Эккерт и Джон Уильям Мокли, учёные из Пенсильванского университета (Электротехническая школа Мура), по заказу Лаборатории баллистических исследований Армии США для расчётов таблиц стрельбы. В отличие от созданного в 1941 году немецким инженером Конрадом Цузе комплекса Z3, использовавшего механические реле, в ЭНИАКе в качестве основы элементной базы применялись электронные лампы.

Начиная с 1943 года группа специалистов под руководством Говарда Эйкена, Дж. Моучли и П. Эккерта в США начала конструировать вычислительную машину на основе электронных ламп, а не на электромагнитных реле. Эта машина была названа ENIAC (Electronic Numeral Integrator And Computer) и работала она в тысячу раз быстрее, чем «Марк-1». ENIAC содержал 18 тысяч вакуумных ламп, занимал площадь 9´15 метров, весил 30 тонн и потреблял мощность 150 киловатт. ENIAC имел и существенный недостаток – управление им осуществлялось с помощью коммутационной панели, у него отсутствовала память, и для того чтобы задать программу приходилось в течение нескольких часов или даже дней подсоединять нужным образом провода. Худшим из всех недостатков была ужасающая ненадежность компьютера, так как за день работы успевало выйти из строя около десятка вакуумных ламп.

9 апреля 1943 года проект был представлен Баллистической лаборатории на заседании Комиссии по науке. В проекте машина называлась «электронный дифф. анализатор» (electronic diff. analyzer). Это была уловка, чтобы новизна проекта не вызвала отторжения у военных. Все они были уже знакомы с дифференциальным анализатором, и проект в их представлении просто предлагал сделать его не механическим, а электрическим. Проект обещал, что построенный компьютер будет вычислять одну траекторию за 5 минут.

31 мая 1943 года военная комиссия начала работать над новым компьютером, Джон Мочли был главным консультантом, а Джон Эккерт Преспер был главным инженером.

В контракте под номером W-670-ORD-4926, заключенном 5 июня 1943 года, машина называлась «Electronic Numerical Integrator» («Электронный числовой интегратор»), позднее к названию было добавлено «and Computer» («и компьютер»), в результате чего получилась знаменитая аббревиатура ENIAC. Куратором проекта «Project PX» со стороны Армии США выступил опять-таки Герман Голдстайн.

В 1944 году все чертежи были готовы и группа инженеров под руководством Мокли и Эккерта начала строить компьютер. Начальником проекта стал Мокли, а главным конструктором — Эккерт. Позже в качестве научного консультанта к ним присоединился Джон фон Нейман.

В январе 1944 года Экерт сделал первый набросок второго компьютера с более совершенным дизайном, в котором программа хранилась в памяти компьютера, а не формировалась с помощью коммутаторов и перестановки блоков, как в ЭНИАКе.

Уже к февралю 1944 года теоретическая работа была завершена: продумана архитектура и прописаны электрические схемы. Началась работа по сборке 27-тонной машины, которая длилась полтора года. Увы, к несчастью для военных, Вторая мировая тогда уже завершилась, даже ядерное оружие было испытано. Однако это был первый настоящий компьютер, которому нашлось применение в расчетах термоядерной бомбы и таблиц стрельб ядерными боеприпасами. История сохранила нам имена шести девушек: Франсис Билас, Рут Лихтерман, Кэтлин Макналти, Франсис Снайдер, Бетти Дженнингс, Мерилин Мельцер. Так звали первых программистов первого компьютера.

К февралю 1944 года были готовы все схемы и чертежи будущего компьютера, и группа инженеров под руководством Эккерта и Мокли приступила к воплощению замысла в «железо». В группу вошли также:

Роберт Шоу (Robert F. Shaw) (функциональные таблицы)

Джеффри Чуан Чу (Jeffrey Chuan Chu) (модуль деления/извлечения квадратного корня)

Томас Кайт Шарплес (Thomas Kite Sharpless) (главный программист)

Артур Бёркс[en] (Arthur Burks) (модуль умножения)

Гарри Хаски (модуль чтения выходных данных)

Джек Дэви (Jack Davis) («аккумуляторы» — модули для сложения чисел)

Джон фон Нейман — присоединился к проекту в сентябре 1944 года в качестве научного консультанта. На основе анализа недостатков ЭНИАКа внёс существенные предложения по созданию новой более совершенной машины — EDVAC.

В середине июля 1944 года Мокли и Эккерт собрали два первых «аккумулятора» — модули, которые использовались для сложения чисел. Соединив их вместе, они перемножили два числа 5 и 1000 и получили верный результат. Этот результат был продемонстрирован руководству Института и Баллистической лаборатории и доказал всем скептикам, что электронный компьютер действительно может быть построен.

Летом 1944 года военный куратор проекта Герман Голдстайн случайно познакомился со знаменитым математиком фон Нейманом и привлёк его к работе над машиной. Фон Нейман внёс свой вклад в проект с точки зрения строгой теории. Так был создан теоретический и инженерный фундамент для следующей модели компьютера под названием EDVAC с хранимой в памяти программой. Контракт с Армией США на создание этой машины был подписан в апреле 1946 года.

В 1945 году к работе был привлечен знаменитый математик Джон фон Нейман, который подготовил доклад об этой машине. В этом докладе фон Нейман ясно и просто сформулировал общие принципы функционирования универсальных вычислительных устройств, т.е. компьютеров.

Научная работа фон Неймана «Первый проект отчёта о EDVAC», обнародованная 30 июня 1945 года, послужила толчком к созданию вычислительных машин в США (EDVAC, BINAC, UNIVAC I) и в Англии (EDSAC). Из-за огромного научного авторитета идея о компьютере с программой, хранимой в памяти, приписывается фон Нейману («архитектура фон Неймана»), хотя приоритет на самом деле принадлежит Экерту, предложившему использовать память на ртутных акустических линиях задержки. Фон Нейман подключился к проекту позднее и просто придал инженерным решениям Мокли и Экерта академический научный смысл.

К ноябрю 1945 года ENIAC полностью функционировал. Он не мог похвастаться такой же надёжностью, как его электромеханические родственники, но он был достаточно надёжным для того, чтобы использовать своё преимущество в скорости в несколько сотен раз. Расчёт баллистической траектории, на который у дифференциального анализатора уходило пятнадцать минут, ENIAC мог провести за двадцать секунд — быстрее, чем летит сам снаряд. И в отличие от анализатора, он мог делать это с той же точностью, что и человек-вычислитель, использующий механический калькулятор.

Осенью 1945 года компьютер построили. Его назвали ENIAC — электронным числовым интегратором и вычислителем. Машина получилась весом в 30 тонн и длиной в 30 метров, в ней было 17 000 радиоламп, 10 000 конденсаторов, 7000 резисторов, 15 000 реле и 6000 переключателей.

Компьютер был полностью готов лишь осенью 1945 года. Так как война к тому времени уже была закончена и острой необходимости в быстром расчёте таблиц стрельбы уже не было, военное ведомство США решило использовать ENIAC в расчётах по разработке термоядерного оружия.

Детали и результаты выполненных в ноябре-декабре 1945 года расчётов до сих пор засекречены. Перед ЭНИАКом была поставлена задача решить сложнейшее дифференциальное уравнение, для ввода исходных данных к которому понадобилось около миллиона перфокарт. Вводная задача была разбита на несколько частей, чтобы данные могли поместиться в память компьютера. Промежуточные результаты выводились на перфокарты и после перекоммутации снова заводились в машину.

14 февраля 1946 года ENIAC показали публике (этот день теперь считается Днём программиста). Сначала компьютер за одну секунду посчитал сумму 5000 чисел, а затем — вычислил траекторию полёта снаряда быстрее, чем тот долетает от орудия до цели.

Впервые о нем написали в газетах 15 февраля 1946 года.

Это первая действующая машина, построенная на вакуумных лампах, официально была введена в эксплуатацию 15 февраля 1946 года. Эту машину пытались использовать для решения некоторых задач, подготовленных фон Нейманом и связанных с проектом атомной бомбы.

Когда в феврале 1946 года компьютер ENIAC был представлен общественности, он выглядел гигантским электронным мозгом. Его создание тогда обошлось в 500 тысяч долларов, что по нынешним меркам эквивалентно 7,2 миллионам долларов. Оборудование компьютера весило… 27 тонн и оно занимало 167 квадратных метров площади! Потребляло 150 кВт электричества, которое приводило в действие 18 800 электронных ламп, самыми распространенными из которых являлись диоды и триоды.

Как уже упоминалось выше, в феврале 1946 года, точнее 15 февраля, компьютер ENIAC был представлен представителям прессы, которые снимали на фото и видео вспышки его электронных ламп. При этом, компьютер производил расчет траектории полета ракеты и справлялся с этим за двадцать секунд, за 10 секунд до того, как реальная ракета могла поразить цель. Для того чтобы сделать работу компьютера более красочной на его панелях было установлено большое количество неоновых ламп, спрятанных под рассеиватели, изготовленные из половинок шариков для пинг-понга. Именно благодаря этой уловке большинство последующих компьютеров уже имели на своих панелях массу лампочек, а потом и светодиодов, которые, перемигиваясь, отображали ход выполняемых компьютером вычислений.

В марте 1946 года Экерт и Мокли из-за споров с Пенсильванским университетом о патентах на ЭНИАК и на EDVAC, над которым они в то время работали, решили покинуть институт Мура и начать частный бизнес в области построения компьютеров, создав компанию Electronic Control Company, которая позднее была переименована в Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation. В качестве «прощального подарка» и по просьбе Армии США они прочитали в институте серию лекций о конструировании компьютеров под общим названием «Теория и методы разработки электронных цифровых компьютеров», опираясь на свой опыт построения ENIAC и проектирования EDVAC. Эти лекции вошли в историю как «Лекции школы Мура». Лекции — по сути первые в истории человечества компьютерные курсы — читались летом 1946 года с 8 июля по 31 августа только для узкого круга специалистов США и Великобритании, работавших над той же проблемой в разных правительственных ведомствах и научных институтах, всего 28 человек. Лекции послужили отправной точкой к созданию в 40-х и 50-х годах успешных вычислительных систем CALDIC, SEAC, SWAC, ILLIAC, машина Института перспективных исследований и компьютер Whirlwind, использовавшийся ВВС США в первой в мире компьютерной системе ПВО SAGE.

Британский физик Дуглас Хартри в апреле и июле 1946 года решал на ЭНИАКе проблему обтекания воздухом крыла самолета, движущегося быстрее скорости звука. ЭНИАК выдал ему результаты расчётов с точностью до седьмого знака. Об этом опыте работы Хартри написал в статье в сентябрьском выпуске журнала Nature за 1946 год.

ENIAC продолжал решать несколько более реальных проблем весь 1946-й год: набор подсчётов по потоку жидкостей (например, для обтекания крыла самолёта) для британского физика Дугласа Хартри, ещё один набор расчётов для моделирования имплозии ядерного оружия, подсчёты траекторий для новой девяностомиллиметровой пушки в Абердине. Затем он замолчал на полтора года. В конце 1946-го, по договору школы Мура с армией, BRL упаковал машину и перевёз её на полигон. Там она постоянно страдала от проблем с надёжностью, и команда BRL не смогла заставить её работать достаточно хорошо для того, чтобы она выполняла какую-то полезную работу, вплоть до крупной модернизации, закончившейся в марте 1948.

В отчете фон Неймана и его коллег Г. Голдстайна и А.Беркса (июнь 1946 года) были четко сформулированы требования к структуре компьютеров. Отметим важнейшие из них:

· машины на электронных элементах должны работать не в десятичной, а в двоичной системе счисления;

· программа, как и исходные данные, должна размещаться в памяти машины;

· программа, как и числа, должна записываться в двоичном коде;

· трудности физической реализации запоминающего устройства, быстродействие которого соответствует скорости работы логических схем, требуют иерархической организации памяти (то есть выделения оперативной, промежуточной и долговременной памяти);