-

Three aspects of semantic

change. -

Causes of semantic change.

-

Nature of semantic change.

Metaphor and metonymy. -

Results of semantic change.

4.1.

Word meanings are liable to change in the process of historical

development

of the language. The semantic structure of a word is never static.

The number of meanings may change, with new meanings being added and

some meaning dropping out; the existing meanings may be rearranged in

the semantic structure.

When speaking about semantic

change, we must distinguish between:

-

the

causes

of semantic change, i.e. the factors bringing it about; we try to

find out why

the word has changed its meaning; -

the

nature

of semantic change; we describe the process of the change and try to

answer the question how

it has been brought about; -

the

results

of semantic change; we try to state what

has been changed.

These are three different but

closely connected aspects of the same problem.

4.2.

The causes,

or factors,

that bring about semantic changes are classified into linguistic

and extralinguistic.

By extralinguistic

causes

we mean various changes in the life of a speech community; changes in

social life, culture, science, technology, economy, etc. as reflected

in word meanings,

e.g. mill

originally was borrowed from Latin in the 1st c. B.C. in the meaning

«a building in which corn is ground into flour». When the

first textile factories appeared in Great Britain it acquired a new

meaning — «a textile factory». The cause of this semantic

change is scientific and technological progress.

Linguistic

causes

are factors that operate within the language system.

They are:

1)

Ellipsis.

In a phrase made up of two words one of them is omitted and its

meaning is transferred to the other one,

e.g. In

OE sterven (MnE to starve) meant “to die, perish». It was

often used in the phrase «sterven of hunger», the second

word was omitted and the verb acquired the new meaning n

die of hunger».

2)

Discrimination

of synonyms,

e.g. In

OE land had two meanings: «1. solid part of Earth’s surface; 2.

the territory of a nation». In ME the word country was borrowed

as a synonym to land. Then the second meaning of land came to be

expressed by country and the semantic structure of land changed.

3)

Linguistic

analogy.

If one member of a synonymic set takes on a new meaning, other

members of the same set may acquire this meaning, too,

e.g.

to catch acquired the meaning «understand»; its synonyms to

get, to qrasp also acquired the same meaning.

-

A

necessary condition of anу

semantic change is some connection or association between the old,

existing meaning and the new one. There are two

main types of association:

-

Similarity

of meaning or metaphor, -

Contiguity

of meaning or metonymy,

i.e. contact, proximity in place or time.

Metaphor

is the semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in

some way resembles the other. Metaphors may be based on similarity of

shape, size,

position, function, etc.

In various languages

metaphoric meanings of words denoting parts of the human body are

most frequent,

e.g. the

eye of a needle «hole in the end of a needle», the neck of

a bottle, the heart of a cabbage — the metaphoric meaning has

developed through similarity of the shape of two objects; the foot of

the hill — this metaphoric change is based on the similarity of

position; the hand of the clock, the Head of the school — the

metaphoric meaning is based on similarity of function.

A special group of metaphors

comprises proper nouns that have become common nouns,

e.g. a

Don Juan — «a lady-killer» , a vandal — «one who

destroys property, works of art» (originally «Germanic

tribe that in the 4th-5th c. ravaged Gaul, Spain, N. Africa, and

Rome, destroying many books and works of art»).

Metonymy

is a semantic process of associating two referents which are somehow

connected or linked in time or space. They may be connected because

they often appear in the same situation,

e.g. bench

has developed the meaning «judges» because it was on

benches that judges used to sit,

or the association may be of

material and an object made of it, etc.,

e.g. silver

– 1) certain .precious metal; 2) silver coins; 3) cutlery; 4)

silver medal,

or they may be associated

because one makes part of the other,

e.g.

factory/farm

hands «workers» (because strong, skillful hands are the

most important part of a person engaged in physical labour).

Common nouns may be derived

from proper names through metonymic transference,

e.g.

Wellingtons

«high boots covering knees in front» (from the 1st Duke of

Wellington, Br. general and statesman, who introduced them in

fashion).

4.4.

Results of semantic change may be observed in the changes of the

denotative component

and the

connotative component

of word meaning.

1) Changes

of the denotative component are of two types:

-

broadening

(or generalization,

= widening, = extension)

of

meaning,

i.e. the range of the new meaning is broader, the word is applied to

a wider range of referents,

e.g. to

arrive, borrowed from French, originally meant «to come to

shore, to land». In MnE it has developed a broader meaning «to

come». Yankee – 1) a native of New England (originally); 2) a

citizen of the USA (now).

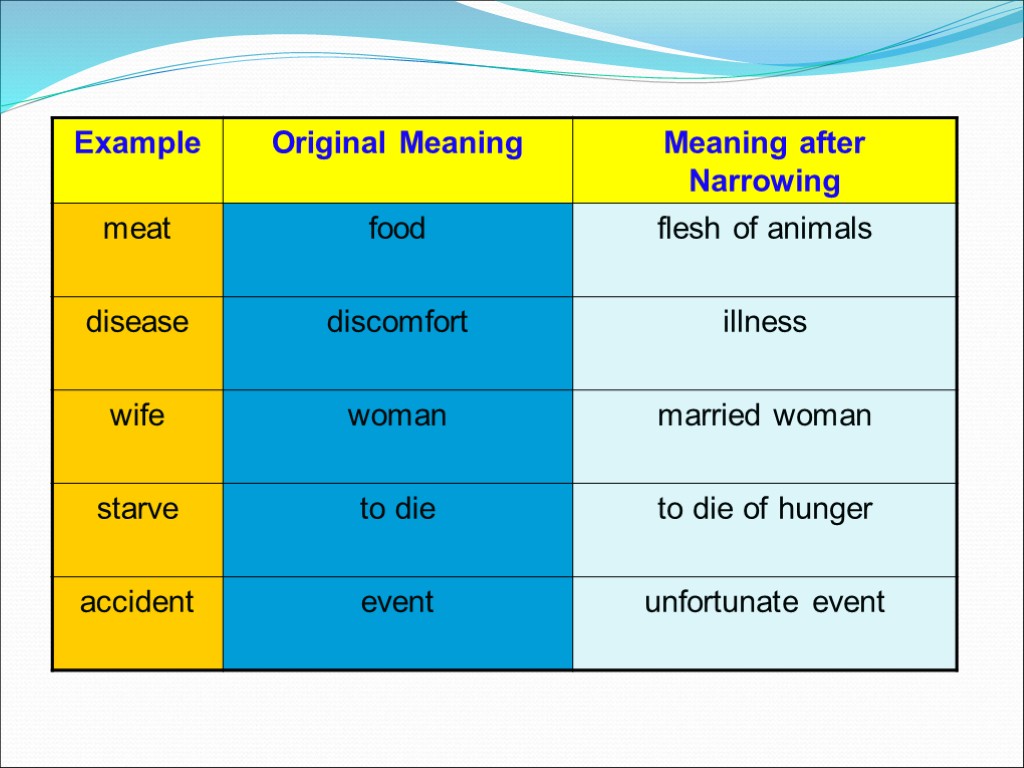

(b) narrowing

(or specialization,

= restriction)

of

meaning.

The word comes to denote a

more limited range of referents, fewer types of them,

e.g. meat

in OE meant «any food», now it means «flesh of animals

used as food» (i.e. some special food); in OE hound meant «a

dog», now it is «a dog of special breed used in chasing

foxes».

As a

special group, we can mention proper

names derived from common nouns,

e.g. the

Border — between Scotland and England,

the

Tower — the museum in London.

2) Changes

in the connotative component of meaning are also of two types:

(a)

degeneration

(or degradation,

= deterioration)

of

meaning,

i.e. a word develops a meaning with a negative evaluative connotation

which was absent in the first meaning,

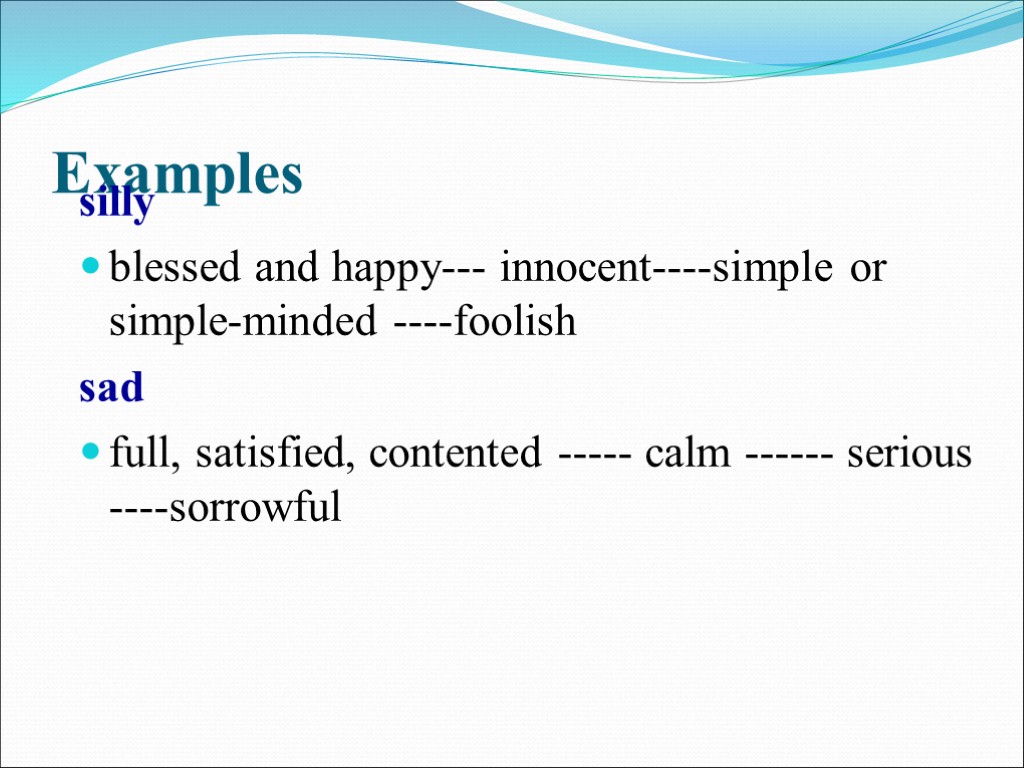

e.g. silly

«happy» (originally) — «foolish» (now);

(b)

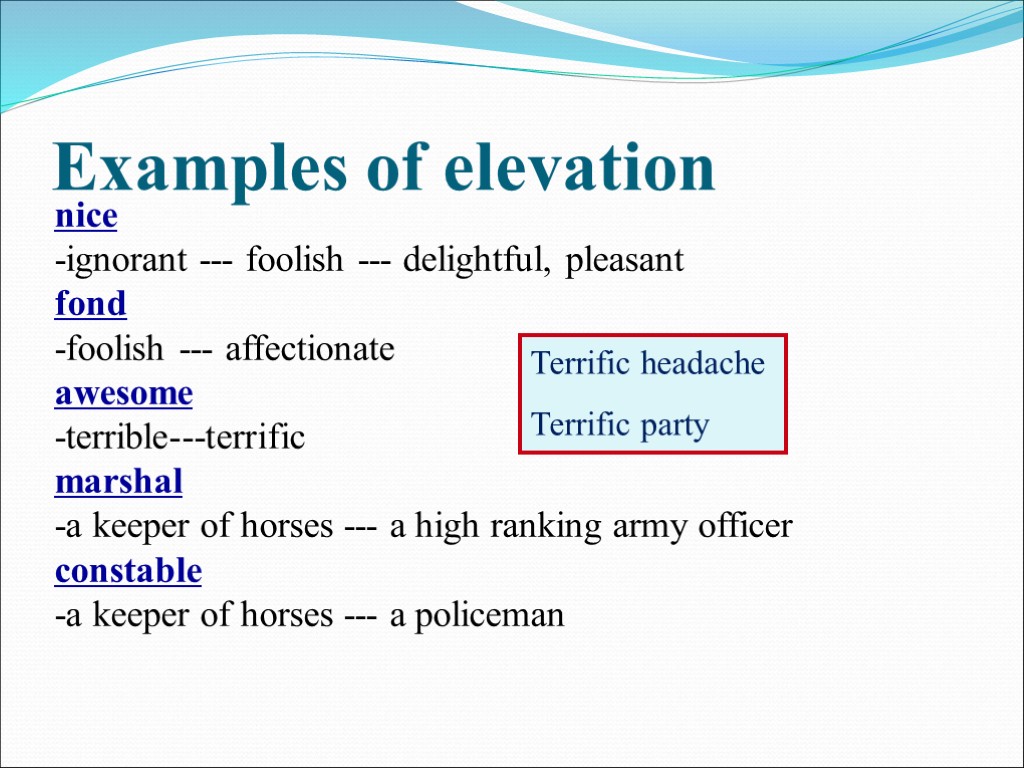

elevation

(or amelioration)

of

meaning,

i.e. the first meaning has a negative connotation and the new one has

not,

e.g. nice

originally «foolish» — now «fine, good».

In other cases the new meaning

acquires positive connotation absent in the original meaning,

e.g. knight

«manservant» (originally) — «noble, courageous man»

(now)

The terms elevation and

degeneration of meaning are inaccurate as we actually deal not with

elevation or degradation of meanings but of referents.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Change of meaning. Extension, narrowing, elevation, degradation of meaning of a word, metaphor, metonymy.

Definition of changes of word meaning Types of changes Extension Elevation Narrowing Degradation Metaphor Metonomy

Changes in word meaning When a word loses its old meaning and comes to refer to something different, the result is a change in word meaning. Change of meaning refers to the alternation of the meaning of existing words, as well as the addition of new meaning to a particular word. Changing word meaning has never ceased since the beginning of the language and will continue in the future. The changes in meaning are gradual, and words are not changed in a day.

Types of Change -Extension of meaning -Narrowing of meaning -Elevation of meaning -Degradation of meaning

Extension of Meaning — Generalization of Meaning It is a process by which a word which originally had a specialized meaning has now become generalized or has extended to cover a broader concept.

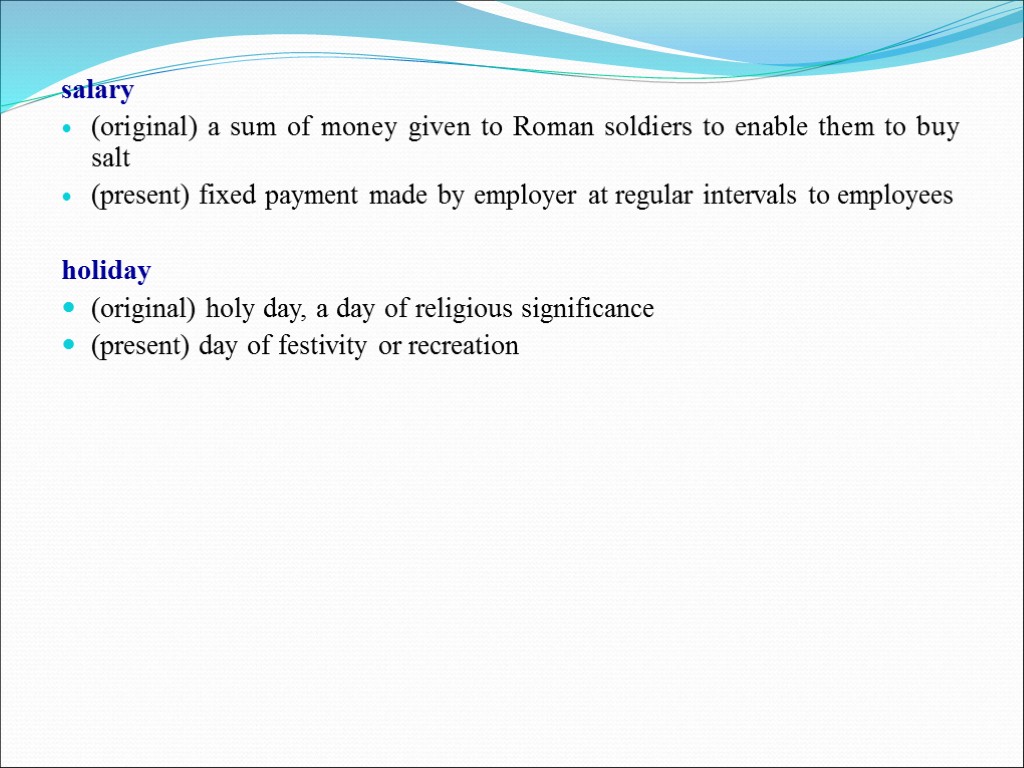

salary (original) a sum of money given to Roman soldiers to enable them to buy salt (present) fixed payment made by employer at regular intervals to employees holiday (original) holy day, a day of religious significance (present) day of festivity or recreation

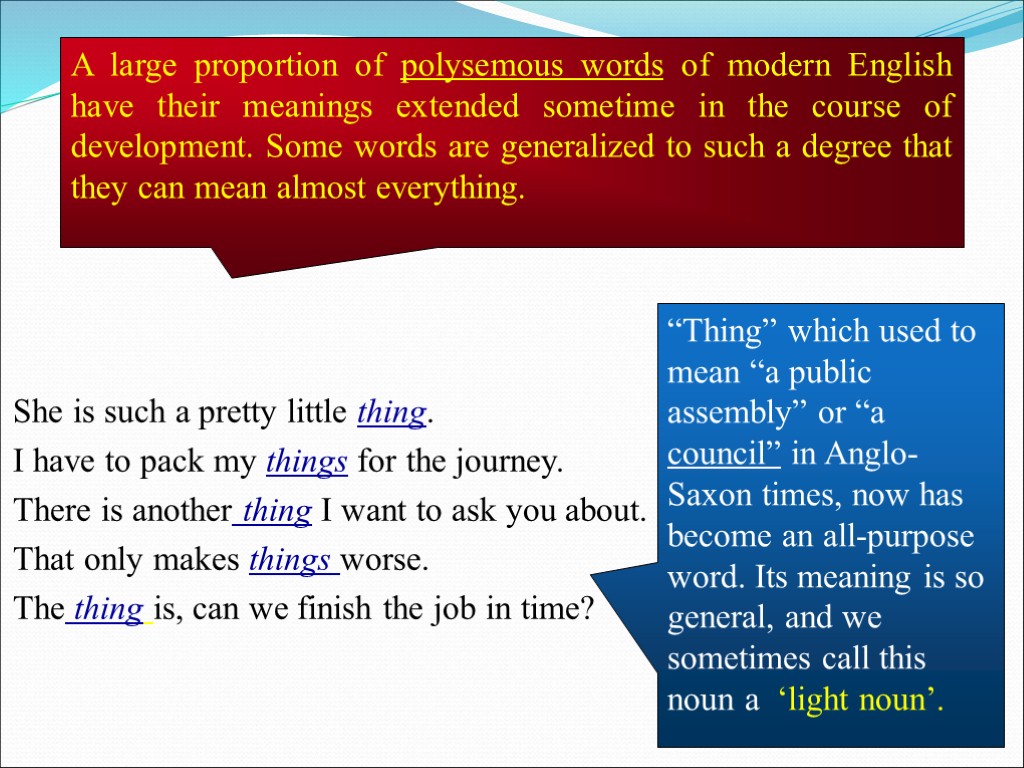

She is such a pretty little thing. I have to pack my things for the journey. There is another thing I want to ask you about. That only makes things worse. The thing is, can we finish the job in time? A large proportion of polysemous words of modern English have their meanings extended sometime in the course of development. Some words are generalized to such a degree that they can mean almost everything. “Thing” which used to mean “a public assembly” or “a council” in Anglo-Saxon times, now has become an all-purpose word. Its meaning is so general, and we sometimes call this noun a ‘light noun’.

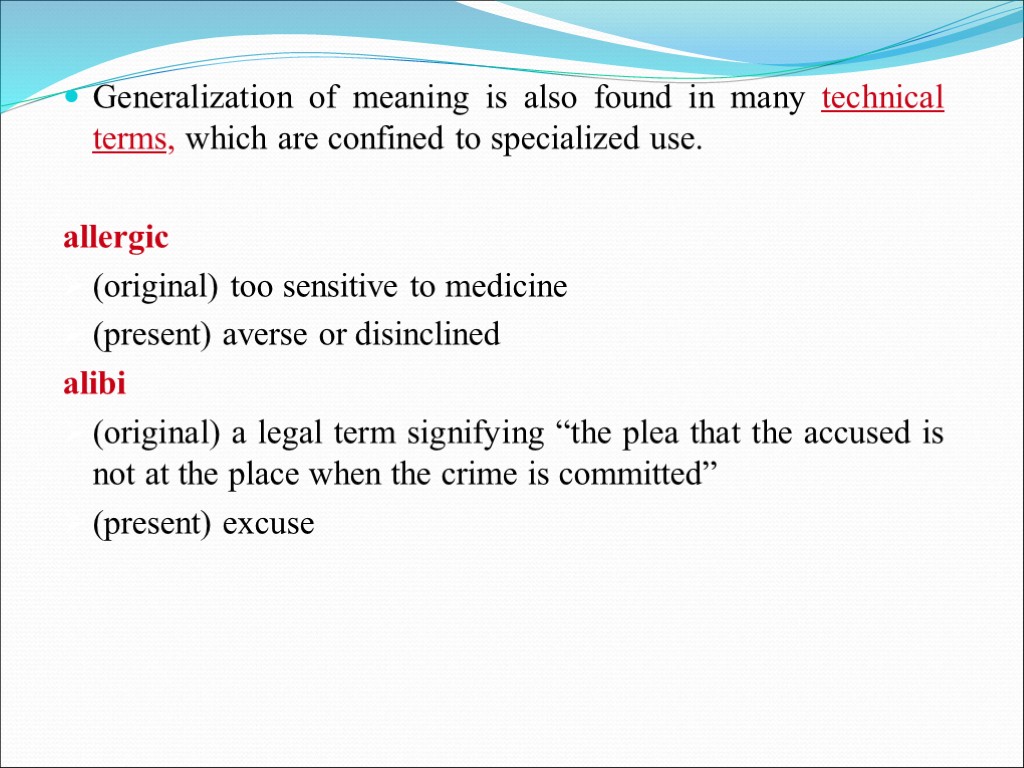

Generalization of meaning is also found in many technical terms, which are confined to specialized use. allergic (original) too sensitive to medicine (present) averse or disinclined alibi (original) a legal term signifying “the plea that the accused is not at the place when the crime is committed” (present) excuse

Narrowing of Meaning It is a process by which a word of wide meaning acquires a narrow or specialized sense. In other words, a word which used to have a more general sense becomes restricted in its application and conveys a special concept in present-day English. Narrowing; specialization; restriction

Narrowing of Meaning For economy, some phrases are shortened and only one element of the original, usually an adjective, is left to retain the meaning of the whole. Such adjectives have thus taken on specialized meanings. a general = a general officer an editorial = an editorial article Some material nouns are used to refer to objects made of them and thus have a more specific sense. glass a cup-like container or a mirror iron device for smoothing clothes

Change in associative meaning Both extension and narrowing of meaning are talking about the changes in conceptual meaning. Next we will talk about the changes in associative meaning. Elevation of meaning Degradation of meaning

Elevation of Meaning (amelioration) -It is the process by which words rise from humble beginnings to positions of importance. -Some words early in their history signify something quite low or humble, but change to designate something agreeable or pleasant. -A “snarl” word becomes a “purr” word, or a slang becomes a common word. -elevation; amelioration

Examples of elevation nice -ignorant — foolish — delightful, pleasant fond -foolish — affectionate awesome -terrible—terrific marshal -a keeper of horses — a high ranking army officer constable -a keeper of horses — a policeman Terrific headache Terrific party

Degradation of Meaning It is a process by which words with appreciatory or neutral affective meaning fall into ill reputation or come to be used in a derogatory sense. A “purr” word becomes a “snarl” word. degradation, degeneration, pejoration

Examples silly blessed and happy— innocent—-simple or simple-minded —-foolish sad full, satisfied, contented —— calm —— serious —-sorrowful

Figurative use of words Change in word meaning may result from the figurative use of the language. Metaphor and metonymy are two important figures of speech. Metaphor is a figure of speech containing an implied comparison based on similarity. E.x.: A cunning person may be referred to as a fox. Here “fox” means something other than its literal meaning. The word “fox” gets the figurative meaning of “a cunning person”.

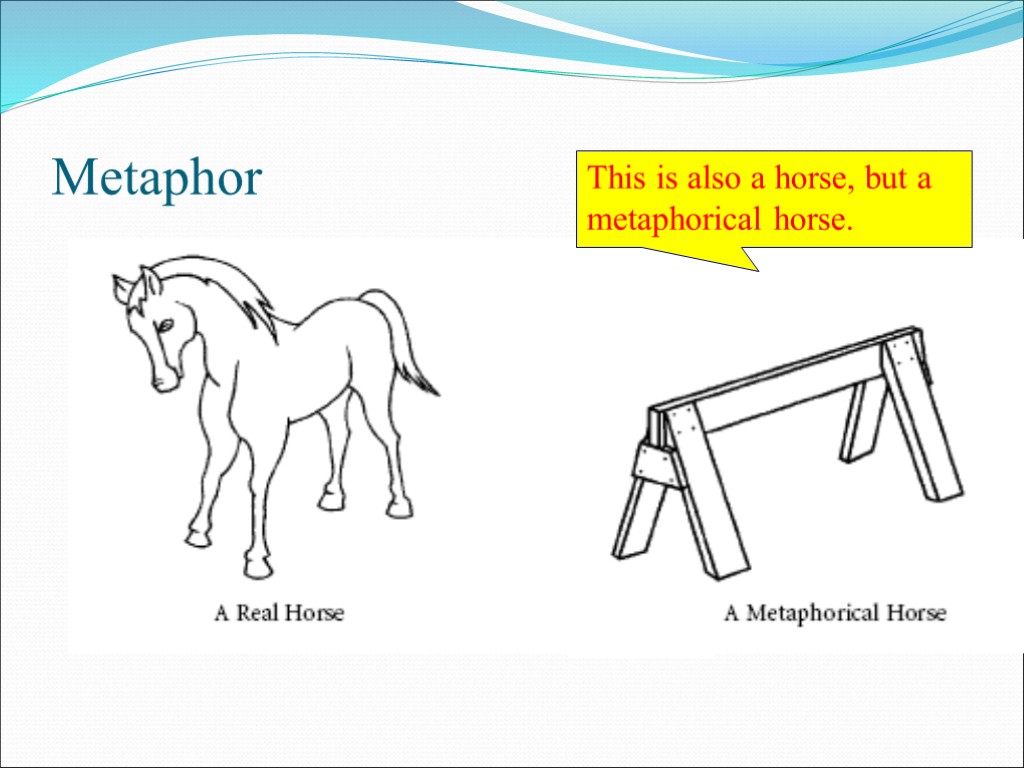

Metaphor This is also a horse, but a metaphorical horse.

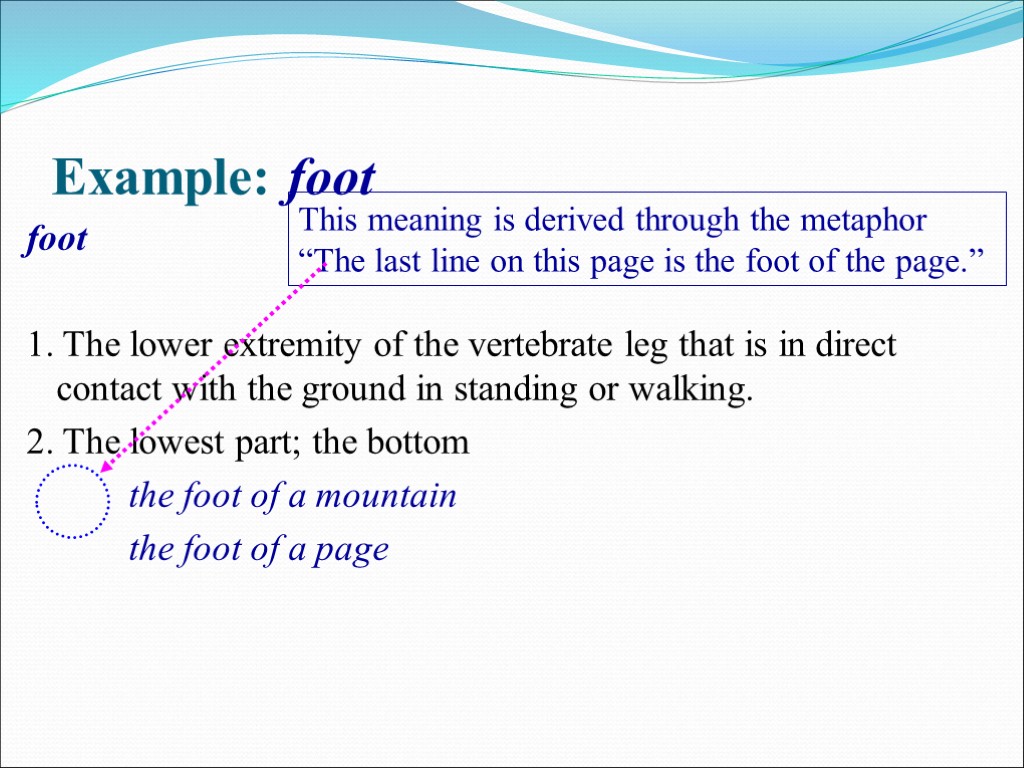

Example: foot foot 1. The lower extremity of the vertebrate leg that is in direct contact with the ground in standing or walking. 2. The lowest part; the bottom the foot of a mountain the foot of a page This meaning is derived through the metaphor “The last line on this page is the foot of the page.”

Metonymy is another important factor in semantic change. It is a figure of speech by which an object or an idea is described by the name of something else closely related to it.

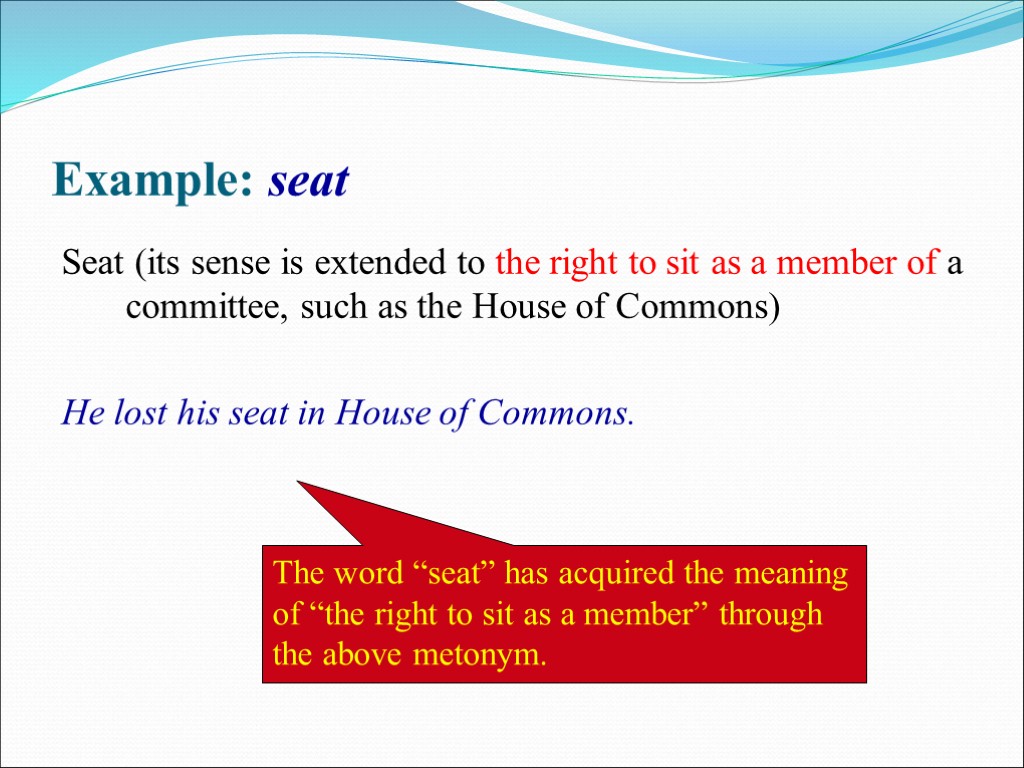

Example: seat Seat (its sense is extended to the right to sit as a member of a committee, such as the House of Commons) He lost his seat in House of Commons. The word “seat” has acquired the meaning of “the right to sit as a member” through the above metonym.

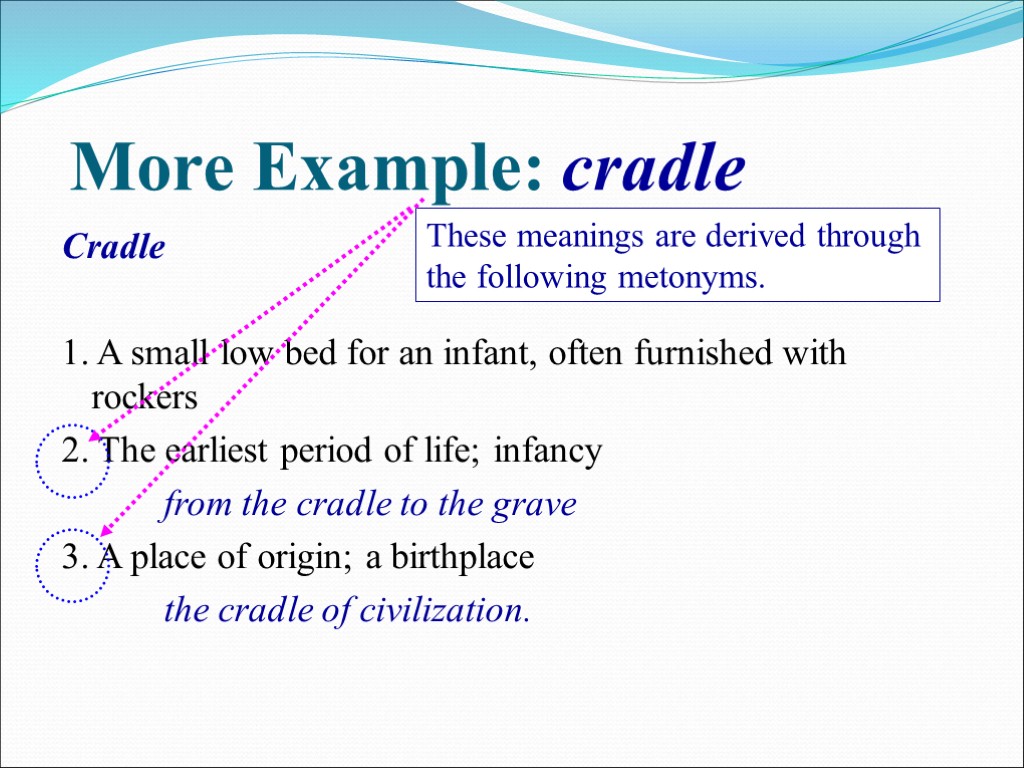

More Example: cradle Cradle 1. A small low bed for an infant, often furnished with rockers 2. The earliest period of life; infancy from the cradle to the grave 3. A place of origin; a birthplace the cradle of civilization. These meanings are derived through the following metonyms.

Semantics refers to the study of meaning. There are two types of semantics: logical and lexical. Logical semantics is the study of reference (the symbolic relationship between language and real-world objects) and implication (the relationship between two sentences). Lexical semantics is the analysis of word meaning.

What is semantic change?

The term semantic change refers to how the meaning of words changes over time. We will cover five types of semantic change: narrowing, broadening, amelioration, pejoration, and semantic reclamation.

Let’s learn about the causes of semantic change, the different types of semantic change, and look at some examples.

The term ‘semantic shift’ can also be used to refer to the changing meanings of words.

The nature of semantic change

It is important to remember that the nature of semantic change is a gradual process. The meaning of a word doesn’t just change in an instant, it can take many years.

Semantic change often occurs as societal values change. This means that different social or ethnic groups may experience semantic change differently for different words.

Causes of semantic change

There are two different causes of semantic change. These are extralinguistic causes (not involving language) and linguistic causes (involving language).

Extralinguistic causes

Extralinguistic causes in semantic change are mainly to do with the social or historical causes of semantic change. If we break the term ‘extralinguistic’ down we can see that it refers to factors that are ‘extra’ so exist outside the language itself. Linguist Andreas Blank breaks down this factor into three main subcategories.

1. Psychological factors

Psychological factors are factors that affect how people view a word and its meaning. If a word’s original meaning is unclear, it is given new meaning. The meaning of a word may also become taboo or is used as a euphemism, eg. the term ‘pass away’ can be used to describe someone dying.

2. Sociocultural factors

This is perhaps the most common factor for extralinguistic causes of semantic change. Changes in the social, economical or political status of a country can have a significant impact on semantics. An example of this is how the meaning of words changed following the Industrial Revolution e.g. the meaning of the word ‘engine’ changed from describing general devices used in war to describing a specific mechanical device. This means that the word went the semantic change (more specifically narrowing).

3. Cultural/encyclopaedic factors

These factors refer to the cultural reasons why a word’s meaning may change. This can be because of cultural changes that lead to a change in how the word is categorised (causing a semantic change). For example, the word ‘cool’ was originally used in the context of jazz music but as the popularity of jazz increased, the word became associated with anything trendy.

| Extralinguistic causes |

| The fuzziness of a meaning |

| Cultural importance changes |

| Word becomes taboo |

| Change in a word’s popularity |

| Communicative changes |

| Changes in worldview |

Linguistic causes

Linguistic causes of semantic change are factors that occur within the system of the language spoken. Natural language changes tend to take longer than extralinguistic causes. We see this throughout history, for example, Old English took centuries to develop into Middle English.

Linguistic factors can include:

Metonymy

Metonymy occurs when the name of an object is substituted for an attribute or adjective. For example, sometimes when discussing horse racing, the tracks are referred to as ‘turf’.

Metaphors

Metaphors may also affect what certain words are associated with. The meaning words may be extended to show a connection between two similar things.

Ellipsis

This occurs when two words are consistently used together in a sentence until they acquire the same meaning. For example, the verb ‘to starve’ originally meant ‘to die’; however, it was frequently used in sentences about hunger. This led to the word’s meaning to die of hunger.

There are factors within these causes that will also impact semantic changes. Have a look at the table below to see some examples of extralinguistic and linguistic causes of semantic change.

| Linguistic causes |

| Metonymy / metaphor |

| Ellipses |

| Changes in the referents (what is being referred to) |

| Excessive length |

| Wordplay and puns |

| Disguising language / misnomers (i.e. an inaccurate name) |

Different types of semantic change

There are five major types of semantic change. These changes occur for either extralinguistic or linguistic reasons. The five major kinds of semantic change are: narrowing, broadening, amelioration, pejoration, and semantic reclamation.

Below, we will discuss the characteristics of these, and look at examples of each type of semantic change.

Narrowing

Semantic narrowing is the process by which a word’s meaning becomes less generalised (in other words more specific) over time. This means that the new meaning derives directly from the original meaning. Typically this process is caused by linguistic factors, such as ellipses, and can take many years to occur. Narrowing can also be referred to as semantic specialisation or semantic restriction.

Let’s look at two examples of semantic narrowing:

Hound

The word ‘hound’, traditionally was used to refer to any type of dog. However, over the centuries the meaning narrowed until it was only used when discussing dogs used when hunting (such as beagles and bloodhounds).

Meat

Similarly, ‘meat’, has also undergone semantic narrowing over the years. The word originally just meant ‘food’. This meaning grew more specific until the word ‘meat’ was only used when relating to one type of food (animal flesh).

Broadening

Broadening is the process in which the meaning of a word becomes more generalised over time. In order words, the word can be used in more contexts than it could originally. This is sometimes referred to as semantic generalisation.

Semantic broadening is the antonym of semantic narrowing, as the process that takes place is the opposite. However, like semantic narrowing, this process often occurs over the course of many years. Broadening can be caused by both extralinguistic and linguistic causes, such as a change in worldview, or linguistic analogy.

Below are two examples of semantic broadening:

Business

The word, ‘business’ originally was only used to refer to being busy. However, over the years, the meaning of this word broadened to refer to any type of work or job.

Cool

The term, ‘cool’, was popular within the language of jazz musicians, as it referred to a specific style of music (‘cool jazz’)! Over time, as jazz music grew in popularity, the word started to be used in other contexts.

Amelioration

Amelioration is a term that refers to when a word acquires a more positive meaning over time. It may also be referred to as semantic amelioration or semantic elevation. Typically this process occurs due to different extralinguistic reasons, such as cultural and worldview changes occurring.

The word ‘nice’ is possibly the most well-known example of amelioration. In the 1300s, the word originally meant that a person was foolish or silly. However, by the 1800s, the process of amelioration had changed this, and the word came to mean that someone was kind and thoughtful. From this, we can see that amelioration is a process that can take centuries to occur.

Sick

Many slang terms, such as ‘sick’, have undergone the process of amelioration over the years. Terms such as ‘sick’ or ‘wicked’ now also have positive connotations. This is because when used as slang, they gain a new, positive, meaning and are associated with the word, ‘cool’.

Pejoration

Pejoration is a term used to describe the process where a word that once had a positive meaning acquires a negative one. It is sometimes also referred to as semantic deterioration. This type of semantic change usually occurs due to extralinguistic causes. This can include a word becoming taboo, or being linked with a taboo within the culture.

Below, we will look at two different examples of pejoration:

Silly

The word, ‘silly’, is a common example of pejoration. In Old and Middle English, the term was used to mean that someone was happy, or spiritually blessed. However, over the centuries, this changed and by the 1500s, the word became associated with acting foolishly — as it is today!

Attitude

This word was originally used to refer to someone’s pose or posture. The meaning of the word changed, referring to someone’s way of thinking instead. From this, the term began to be used colloquially which led it to be associated with acting rude or unkind. A phrase such as ‘he has a bad attitude’ can become shortened to ‘he has an attitude’, showing that the word has gained a negative meaning.

Semantic change: reclamation

Semantic reclamation occurs when a group of people who have been oppressed reclaim (or take back) a word that has been used in the past to disparage them. The people who reclaim these words use them in a positive context and in doing this, the word is stripped of its power to disparage the group.

Semantic reclamation is often a political and controversial act, as these words become special to one particular group. Words have been reclaimed by groups such as women, ethnic minorities and the LGBTQIA community.

It is important to remember when discussing this form of semantic change that, unlike amelioration, the word may still also be used in the pejorative sense.

Words that have undergone semantic change

We’ve discussed examples of the different types of semantic change. However, here are a few more interesting examples that show the change of the English language over time!

- Girl (narrowing)- originally referred to a child of either gender. The meaning narrowed to refer to a female child.

- Playdough (broadening)- was originally the brand name. The meaning broadened to refer to the product as well.

- Fun (amelioration)- originally had negative connotations meaning ‘to cheat or trick’. The meaning now has positive connotations of amusement.

- Stench (pejoration)- originally meant ‘smell, odour, or fragrance’. The meaning now has negative connotations of a bad or unpleasant smell.

Semantic Change — Key Takeaways

- Semantic change refers to a type of language change in which the meaning of a word changes over time. Semantic change can be caused by extralinguistic and linguistic factors.

- Narrowing is when a word’s meaning becomes more specialised in time.

- Broadening is when a word becomes more generalised and gains additional meanings.

- Amelioration is when a word’s meaning changes from negative to positive.

- Pejoration is when a word’s meaning changes from positive to negative.

- Semantic reclamation is a process where a word that was once used to disparage a group of people is reclaimed by the group.

4.1. Three aspects of semantic change.

4.2. Causes of semantic change.

4.3. Nature of semantic change. Metaphor and metonymy.

4.4. Results of semantic change.

4.1. Word meanings are liable to change in the process of historical development of the language. The semantic structure of a word is never static. The number of meanings may change, with new meanings being added and some meaning dropping out; the existing meanings may be rearranged in the semantic structure.

When speaking about semantic change, we must distinguish between:

2) the causes of semantic change, i.e. the factors bringing it about; we try to find out why the word has changed its meaning;

3) the nature of semantic change; we describe the process of the change and try to answer the question how it has been brought about;

4) the results of semantic change; we try to state what has been changed.

These are three different but closely connected aspects of the same problem.

4.2. The causes, or factors, that bring about semantic changes are classified into linguistic and extralinguistic. By extralinguistic causes we mean various changes in the life of a speech community; changes in social life, culture, science, technology, economy, etc. as reflected in word meanings,

e.g. mill originally was borrowed from Latin in the 1st c. B.C. in the meaning » a building in which corn is ground into flour». When the first textile factories appeared in Great Britain it acquired a new meaning — » a textile factory». The cause of this semantic change is scientific and technological progress.

Linguistic causes are factors that operate within the language system. They are:

1) Ellipsis. In a phrase made up of two words one of them is omitted and its meaning is transferred to the other one,

e.g. In OE sterven (MnE to starve) meant “to die, perish». It was often used in the phrase » sterven of hunger», the second word was omitted and the verb acquired the new meaning n die of hunger».

2) Discrimination of synonyms,

e.g. In OE land had two meanings: » 1. solid part of Earth’s surface; 2. the territory of a nation». In ME the word country was borrowed as a synonym to land. Then the second meaning of land came to be expressed by country and the semantic structure of land changed.

3) Linguistic analogy. If one member of a synonymic set takes on a new meaning, other members of the same set may acquire this meaning, too,

e.g. to catch acquired the meaning » understand»; its synonyms to get, to qrasp also acquired the same meaning.

4.3 A necessary condition of anу semantic change is some connection or association between the old, existing meaning and the new one. There are two main types of association:

1) Similarity of meaning or metaphor,

2) Contiguity of meaning or metonymy, i.e. contact, proximity in place or time.

Metaphor is the semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some way resembles the other. Metaphors may be based on similarity of shape, size, position, function, etc.

In various languages metaphoric meanings of words denoting parts of the human body are most frequent,

e.g. the eye of a needle » hole in the end of a needle», the neck of a bottle, the heart of a cabbage — the metaphoric meaning has developed through similarity of the shape of two objects; the foot of the hill — this metaphoric change is based on the similarity of position; the hand of the clock, the Head of the school — the metaphoric meaning is based on similarity of function.

A special group of metaphors comprises proper nouns that have become common nouns,

e.g. a Don Juan — » a lady-killer», a vandal — » one who destroys property, works of art» (originally » Germanic tribe that in the 4th-5th c. ravaged Gaul, Spain, N. Africa, and Rome, destroying many books and works of art»).

Metonymy is a semantic process of associating two referents which are somehow connected or linked in time or space. They may be connected because they often appear in the same situation,

e.g. bench has developed the meaning » judges» because it was on benches that judges used to sit,

or the association may be of material and an object made of it, etc.,

e.g. silver – 1) certain.precious metal; 2) silver coins; 3) cutlery; 4) silver medal,

or they may be associated because one makes part of the other,

e.g. factory/farm hands » workers» (because strong, skillful hands are the most important part of a person engaged in physical labour).

Common nouns may be derived from proper names through metonymic transference,

e.g. Wellingtons » high boots covering knees in front» (from the 1st Duke of Wellington, Br. general and statesman, who introduced them in fashion).

4.4. Results of semantic change may be observed in the changes of the denotative component and the connotative component of word meaning.

1) Changes of the denotative component are of two types:

(a) broadening (or generalization, = widening, = extension) of meaning, i.e. the range of the new meaning is broader, the word is applied to a wider range of referents,

e.g. to arrive, borrowed from French, originally meant » to come to shore, to land». In MnE it has developed a broader meaning » to come». Yankee – 1) a native of New England (originally); 2) a citizen of the USA (now).

(b) narrowing (or specialization, = restriction) of meaning.

The word comes to denote a more limited range of referents, fewer types of them,

e.g. meat in OE meant » any food», now it means » flesh of animals used as food» (i.e. some special food); in OE hound meant » a dog», now it is » a dog of special breed used in chasing foxes»;.

As a special group, we can mention proper names derived from common nouns,

e.g. the Border — between Scotland and England,

the Tower — the museum in London.

2) Changes in the connotative component of meaning are also of two types:

(a) degeneration (or degradation, = deterioration) of meaning, i.e. a word develops a meaning with a negative evaluative connotation which was absent in the first meaning,

e.g. silly » happy» (originally) — » foolish» (now);

(b) elevation (or amelioration) of meaning, i.e. the first meaning has a negative connotation and the new one has not,

e.g. nice originally » foolish» — now » fine, good»;.

In other cases the new meaning acquires positive connotation absent in the original meaning,

e.g. knight » manservant» (originally) — » noble, courageous man» (now)

The terms elevation and degeneration of meaning are inaccurate as we actually deal not with elevation or degradation of meanings but of referents.

|

Обзор компонентов Multisim Компоненты – это основа любой схемы, это все элементы, из которых она состоит. Multisim оперирует с двумя категориями… |

Композиция из абстрактных геометрических фигур Данная композиция состоит из линий, штриховки, абстрактных геометрических форм… |

Важнейшие способы обработки и анализа рядов динамики Не во всех случаях эмпирические данные рядов динамики позволяют определить тенденцию изменения явления во времени… |

ТЕОРЕТИЧЕСКАЯ МЕХАНИКА Статика является частью теоретической механики, изучающей условия, при которых тело находится под действием заданной системы сил… |

Generalization, Specialization, Amelioration, and Pejoration

Updated on October 05, 2018

Stick around long enough and you’ll notice that language changes—whether you like it or not. Consider this recent report from columnist Martha Gill on the redefinition of the word literally:

It’s happened. Literally the most misused word in the language has officially changed definition. Now as well as meaning «in a literal manner or sense; exactly: ‘the driver took it literally when asked to go straight over the traffic circle,'» various dictionaries have added its other more recent usage. As Google puts it, «literally» can be used «to acknowledge that something is not literally true but is used for emphasis or to express strong feeling.» . . .

«Literally,» you see, in its development from knock-kneed, single-purpose utterance, to swan-like dual-purpose term, has reached that awkward stage. It is neither one nor the other, and it can’t do anything right.»

(Martha Gill, «Have We Literally Broken the English Language?» The Guardian [UK], August 13, 2013)

Changes in word meanings (a process called semantic shift) happen for various reasons and in various ways. Four common types of change are broadening, narrowing, amelioration, and pejoration. (For more detailed discussions of these processes, click on the highlighted terms.)

- Broadening

Also known as generalization or extension, broadening is the process by which a word’s meaning becomes more inclusive than an earlier meaning. In Old English, for instance, the word dog referred to just one particular breed, and thing meant a public assembly. In contemporary English, of course, dog can refer to many different breeds, and thing can refer to, well, anything. - Narrowing

The opposite of broadening is narrowing (also called specialization or restriction), a type of semantic change in which a word’s meaning becomes less inclusive. For example, in Middle English, deer could refer to any animal, and girl could mean a young person of either sex. Today, those words have more specific meanings. - Amelioration

Amelioration refers to the upgrading or rise in status of a word’s meaning. For example, meticulous once meant «fearful or timid,» and sensitive meant simply «capable of using one’s senses.» - Pejoration

More common than amelioration is the downgrading or depreciation of a word’s meaning, a process called pejoration. The adjective silly, for instance, once meant «blessed» or «innocent,» officious meant «hard working,» and aggravate meant to «increase the weight» of something.

What’s worth keeping in mind is that meanings don’t change over night. Different meanings of the same word often overlap, and new meanings can co-exist with older meanings for centuries. In linguistic terms, polysemy is the rule, not the exception.

«Words are by nature incurably fuzzy,» says linguist Jean Aitchison in the book Language Change: Progress Or Decay. In recent years, the adverb literally has become exceptionally fuzzy. In fact, it has slipped into the rare category of Janus words, joining terms like sanction, bolt, and fix that contain opposite or contradictory meanings.

Martha Gill concludes that there’s not much we can do about literally. The awkward stage that it’s going through may last for quite some time. «It is a moot word,» she says. «We just have to leave it up in its bedroom for a while until it grows up a bit.»

More About Language Change

- The Endless Decline of the English Language

- The Great Vowel Shift

- Inconceivable!: 5 Words That May Not Mean What You Think They Mean

- Key Dates in the History of the English Language

- Six Common Myths About Language

- Semantic Change and the Etymological Fallacy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Semantic change (also semantic shift, semantic progression, semantic development, or semantic drift) is a form of language change regarding the evolution of word usage—usually to the point that the modern meaning is radically different from the original usage. In diachronic (or historical) linguistics, semantic change is a change in one of the meanings of a word. Every word has a variety of senses and connotations, which can be added, removed, or altered over time, often to the extent that cognates across space and time have very different meanings. The study of semantic change can be seen as part of etymology, onomasiology, semasiology, and semantics.

Examples in English[edit]

- Awful — Literally «full of awe», originally meant «inspiring wonder (or fear)», hence «impressive». In contemporary usage, the word means «extremely bad».

- Awesome — Literally «awe-inducing», originally meant «inspiring wonder (or fear)», hence «impressive». In contemporary usage, the word means «extremely good».

- Terrible — Originally meant «inspiring terror», shifted to indicate anything spectacular, then to something spectacularly bad.

- Terrific — Originally meant «inspiring terror», shifted to indicate anything spectacular, then to something spectacularly good.[1]

- Nice — Originally meant «foolish, ignorant, frivolous, senseless.» from Old French nice (12c.) meaning «careless, clumsy; weak; poor, needy; simple, stupid, silly, foolish,» from Latin nescius («ignorant or unaware»). Literally «not-knowing,» from ne- «not» (from PIE root *ne- «not») + stem of scire «to know» (compare with science). «The sense development has been extraordinary, even for an adj.» [Weekley] — from «timid, faint-hearted» (pre-1300); to «fussy, fastidious» (late 14c.); to «dainty, delicate» (c. 1400); to «precise, careful» (1500s, preserved in such terms as a nice distinction and nice and early); to «agreeable, delightful» (1769); to «kind, thoughtful» (1830).

- Naïf or Naïve —Initially meant «natural, primitive, or native» . From French naïf, literally «native«. The masculine form of the French word, but used in English without reference to gender. As a noun, «natural, artless, naive person,» first attested 1893, from French, where Old French naif also meant «native inhabitant; simpleton, natural fool.»

- Demagogue — Originally meant «a popular leader». It is from the Greek dēmagōgós «leader of the people», from dēmos «people» + agōgós «leading, guiding». Now the word has strong connotations of a politician who panders to emotions and prejudice.

- Egregious — Originally described something that was remarkably good (as in Theorema Egregium). The word is from the Latin egregius «illustrious, select», literally, «standing out from the flock», which is from ex—»out of» + greg—(grex) «flock». Now it means something that is remarkably bad or flagrant.

- Gay — Originally meant (13th century) «lighthearted», «joyous» or (14th century) «bright and showy», it also came to mean «happy»; it acquired connotations of immorality as early as 1637, either sexual e.g., gay woman «prostitute», gay man «womaniser», gay house «brothel», or otherwise, e.g., gay dog «over-indulgent man» and gay deceiver «deceitful and lecherous». In the United States by 1897 the expression gay cat referred to a hobo, especially a younger hobo in the company of an older one; by 1935, it was used in prison slang for a homosexual boy; and by 1951, and clipped to gay, referred to homosexuals. George Chauncey, in his book Gay New York, would put this shift as early as the late 19th century among a certain «in crowd», knowledgeable of gay night-life. In the modern day, it is most often used to refer to homosexuals, at first among themselves and then in society at large, with a neutral connotation; or as a derogatory synonym for «silly», «dumb», or «boring».[2]

- Guy — Guy Fawkes was the alleged leader of a plot to blow up the English Houses of Parliament on 5 November 1605. The day was made a holiday, Guy Fawkes Day, commemorated by parading and burning a ragged manikin of Fawkes, known as a Guy. This led to the use of the word guy as a term for any «person of grotesque appearance» and then by the late 1800s—especially in the United States—for «any man», as in, e.g., «Some guy called for you.» Over the 20th century, guy has replaced fellow in the U.S., and, under the influence of American popular culture, has been gradually replacing fellow, bloke, chap and other such words throughout the rest of the English-speaking world. In the plural, it can refer to a mixture of genders (e.g., «Come on, you guys!» could be directed to a group of mixed gender instead of only men).

Evolution of types[edit]

A number of classification schemes have been suggested for semantic change.

Recent overviews have been presented by Blank[3] and Blank & Koch (1999). Semantic change has attracted academic discussions since ancient times, although the first major works emerged in the 19th century with Reisig (1839), Paul (1880), and Darmesteter (1887).[4] Studies beyond the analysis of single words have been started with the word-field analyses of Trier (1931), who claimed that every semantic change of a word would also affect all other words in a lexical field.[5] His approach was later refined by Coseriu (1964). Fritz (1974) introduced Generative semantics. More recent works including pragmatic and cognitive theories are those in Warren (1992), Dirk Geeraerts,[6] Traugott (1990) and Blank (1997).

A chronological list of typologies is presented below. Today, the most currently used typologies are those by Bloomfield (1933) and Blank (1999).

Typology by Reisig (1839)[edit]

Reisig’s ideas for a classification were published posthumously. He resorts to classical rhetorics and distinguishes between

- Synecdoche: shifts between part and whole

- Metonymy: shifts between cause and effect

- Metaphor

Typology by Paul (1880)[edit]

- Generalization: enlargement of single senses of a word’s meaning

- Specialization on a specific part of the contents: reduction of single senses of a word’s meaning

- Transfer on a notion linked to the based notion in a spatial, temporal, or causal way

Typology by Darmesteter (1887)[edit]

- Metaphor

- Metonymy

- Narrowing of meaning

- Widening of meaning

The last two are defined as change between whole and part, which would today be rendered as synecdoche.

Typology by Bréal (1899)[edit]

- Restriction of sense: change from a general to a special meaning

- Enlargement of sense: change from a special to a general meaning

- Metaphor

- «Thickening» of sense: change from an abstract to a concrete meaning

Typology by Stern (1931)[edit]

- Substitution: Change related to the change of an object, of the knowledge referring to the object, of the attitude toward the object, e.g., artillery «engines of war used to throw missiles» → «mounted guns», atom «inseparable smallest physical-chemical element» → «physical-chemical element consisting of electrons», scholasticism «philosophical system of the Middle Ages» → «servile adherence to the methods and teaching of schools»

- Analogy: Change triggered by the change of an associated word, e.g., fast adj. «fixed and rapid» ← faste adv. «fixedly, rapidly»)

- Shortening: e.g., periodical ← periodical paper

- Nomination: «the intentional naming of a referent, new or old, with a name that has not previously been used for it» (Stern 1931: 282), e.g., lion «brave man» ← «lion»

- Regular transfer: a subconscious Nomination

- Permutation: non-intentional shift of one referent to another due to a reinterpretation of a situation, e.g., bead «prayer» → «pearl in a rosary»)

- Adequation: Change in the attitude of a concept; distinction from substitution is unclear.

This classification does not neatly distinguish between processes and forces/causes of semantic change.

Typology by Bloomfield (1933)[edit]

The most widely accepted scheme in the English-speaking academic world[according to whom?] is from Bloomfield (1933):

- Narrowing: Change from superordinate level to subordinate level. For example, skyline formerly referred to any horizon, but now in the US it has narrowed to a horizon decorated by skyscrapers.[7]

- Widening: There are many examples of specific brand names being used for the general product, such as with Kleenex.[7] Such uses are known as generonyms: see genericization.

- Metaphor: Change based on similarity of thing. For example, broadcast originally meant «to cast seeds out»; with the advent of radio and television, the word was extended to indicate the transmission of audio and video signals. Outside of agricultural circles, very few use broadcast in the earlier sense.[7]

- Metonymy: Change based on nearness in space or time, e.g., jaw «cheek» → «mandible».

- Synecdoche: Change based on whole-part relation. The convention of using capital cities to represent countries or their governments is an example of this.

- Hyperbole: Change from weaker to stronger meaning, e.g., kill «torment» → «slaughter»

- Meiosis: Change from stronger to weaker meaning, e.g., astound «strike with thunder» → «surprise strongly».

- Degeneration: e.g., knave «boy» → «servant» → «deceitful or despicable man»; awful «awe-inspiring» → «very bad.»

- Elevation: e.g., knight «boy» → «nobleman»; terrific «terrifying» → «astonishing» → «very good».

Typology by Ullmann (1957, 1962)[edit]

Ullmann distinguishes between nature and consequences of semantic change:

- Nature of semantic change

- Metaphor: change based on a similarity of senses

- Metonymy: change based on a contiguity of senses

- Folk-etymology: change based on a similarity of names

- Ellipsis: change based on a contiguity of names

- Consequences of semantic change

- Widening of meaning: rise of quantity

- Narrowing of meaning: loss of quantity

- Amelioration of meaning: rise of quality

- Pejoration of meaning: loss of quality

Typology by Blank (1999)[edit]

However, the categorization of Blank (1999) has gained increasing acceptance:[8]

- Metaphor: Change based on similarity between concepts, e.g., mouse «rodent» → «computer device».

- Metonymy: Change based on contiguity between concepts, e.g., horn «animal horn» → «musical instrument».

- Synecdoche: A type of metonymy involving a part to whole relationship, e.g. «hands» from «all hands on deck» → «bodies»

- Specialization of meaning: Downward shift in a taxonomy, e.g., corn «grain» → «wheat» (UK), → «maize» (US).

- Generalization of meaning: Upward shift in a taxonomy, e.g., hoover «Hoover vacuum cleaner» → «any type of vacuum cleaner».

- Cohyponymic transfer: Horizontal shift in a taxonomy, e.g., the confusion of mouse and rat in some dialects.

- Antiphrasis: Change based on a contrastive aspect of the concepts, e.g., perfect lady in the sense of «prostitute».

- Auto-antonymy: Change of a word’s sense and concept to the complementary opposite, e.g., bad in the slang sense of «good».

- Auto-converse: Lexical expression of a relationship by the two extremes of the respective relationship, e.g., take in the dialectal use as «give».

- Ellipsis: Semantic change based on the contiguity of names, e.g., car «cart» → «automobile», due to the invention of the (motor) car.

- Folk-etymology: Semantic change based on the similarity of names, e.g., French contredanse, orig. English country dance.

Blank considered it problematic to include amelioration and pejoration of meaning (as in Ullman) as well as strengthening and weakening of meaning (as in Bloomfield). According to Blank, these are not objectively classifiable phenomena; moreover, Blank has argued that all of the examples listed under these headings can be grouped under other phenomena, rendering the categories redundant.

Forces triggering change[edit]

Blank[9] has tried to create a complete list of motivations for semantic change. They can be summarized as:

- Linguistic forces

- Psychological forces

- Sociocultural forces

- Cultural/encyclopedic forces

This list has been revised and slightly enlarged by Grzega (2004):[10]

- Fuzziness (i.e., difficulties in classifying the referent or attributing the right word to the referent, thus mixing up designations)

- Dominance of the prototype (i.e., fuzzy difference between superordinate and subordinate term due to the monopoly of the prototypical member of a category in the real world)

- Social reasons (i.e., contact situation with «undemarcation» effects)

- Institutional and non-institutional linguistic pre- and proscriptivism (i.e., legal and peer-group linguistic pre- and proscriptivism, aiming at «demarcation»)

- Flattery

- Insult

- Disguising language (i.e., «misnomers»)

- Taboo (i.e., taboo concepts)

- Aesthetic-formal reasons (i.e., avoidance of words that are phonetically similar or identical to negatively associated words)

- Communicative-formal reasons (i.e., abolition of the ambiguity of forms in context, keyword: «homonymic conflict and polysemic conflict»)

- Wordplay/punning

- Excessive length of words

- Morphological misinterpretation (keyword: «folk-etymology», creation of transparency by changes within a word)

- Logical-formal reasons (keyword: «lexical regularization», creation of consociation)

- Desire for plasticity (creation of a salient motivation of a name)

- Anthropological salience of a concept (i.e., anthropologically given emotionality of a concept, «natural salience»)

- Culture-induced salience of a concept («cultural importance»)

- Changes in the referents (i.e., changes in the world)

- Worldview change (i.e., changes in the categorization of the world)

- Prestige/fashion (based on the prestige of another language or variety, of certain word-formation patterns, or of certain semasiological centers of expansion)

The case of reappropriation[edit]

A specific case of semantic change is reappropriation, a cultural process by which a group reclaims words or artifacts that were previously used in a way disparaging of that group, for example like with the word queer. Other related processes include pejoration and amelioration.[11]

Practical studies[edit]

Apart from many individual studies, etymological dictionaries are prominent reference books for finding out about semantic changes. A recent survey lists practical tools and online systems for investigating semantic change of words over time.[12] WordEvolutionStudy is an academic platform that takes arbitrary words as input to generate summary views of their evolution based on Google Books ngram dataset and the Corpus of Historical American English.[13]

See also[edit]

- Calque

- Dead metaphor

- Euphemism treadmill

- False friend

- Genericized trademark

- Language change

- Lexicology and lexical semantics

- List of calques

- Newspeak

- Phono-semantic matching

- Q-based narrowing

- Semantic field

- Skunked term

- Retronym

Notes[edit]

- ^ «13 Words That Changed From Negative to Positive Meanings (or Vice Versa)». Mental Floss. July 9, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Lalor, Therese (2007). «‘That’s So Gay’: A Contemporary Use of Gay in Australian English». Australian Journal of Linguistics. 27 (200): 147–173. doi:10.1080/07268600701522764. hdl:1885/30763. S2CID 53710541.

- ^ Blank (1997:7–46)

- ^ in Ullmann (1957), and Ullmann (1962)

- ^ An example of this comes from Old English: meat (or rather mete) referred to all forms of solid food while flesh (flæsc) referred to animal tissue and food (foda) referred to animal fodder; meat was eventually restricted to flesh of animals, then flesh restricted to the tissue of humans and food was generalized to refer to all forms of solid food Jeffers & Lehiste (1979:130)

- ^ in Geeraerts (1983) and Geeraerts (1997)

- ^ a b c Jeffers & Lehiste (1979:129)

- ^ Grzega (2004) paraphrases these categories (except ellipses and folk etymology) as «similar-to» relation, «neighbor-of» relation, «part-of» relation, «kind-of» relation (for both specialization and generalization), «sibling-of» relation, and «contrast-to» relation (for antiphrasis, auto-antonymy, and auto-converse), respectively

- ^ in Blank (1997) and Blank (1999)

- ^ Compare Grzega (2004) and Grzega & Schöner (2007)

- ^ Anne Curzan (May 8, 2014). Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-1-107-02075-7.

- ^ Adam Jatowt, Nina Tahmasebi, Lars Borin (2021). Computational Approaches to Lexical Semantic Change: Visualization Systems and Novel Applications. Language Science Press. pp. 311–340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adam Jatowt (2018). «Every Word has its History: Interactive Exploration and Visualization of Word Sense Evolution» (PDF). ACM Press. pp. 1988–1902.

References[edit]

- Blank, Andreas (1997), Prinzipien des lexikalischen Bedeutungswandels am Beispiel der romanischen Sprachen (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 285), Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Blank, Andreas (1999), «Why do new meanings occur? A cognitive typology of the motivations for lexical Semantic change», in Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (eds.), Historical Semantics and Cognition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 61–90

- Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (1999), «Introduction: Historical Semantics and Cognition», in Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter (eds.), Historical Semantics and Cognition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–16

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1933), Language, New York: Allen & Unwin

- Bréal, Michel (1899), Essai de sémantique (2nd ed.), Paris: Hachette

- Coseriu, Eugenio (1964), «Pour une sémantique diachronique structurale», Travaux de Linguistique et de Littérature, 2: 139–186

- Darmesteter, Arsène (1887), La vie des mots, Paris: Delagrave

- Fritz, Gerd (1974), Bedeutungswandel im Deutschen, Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Geeraerts, Dirk (1983), «Reclassifying Semantic change», Quaderni di Semantica, 4: 217–240

- Geeraerts, Dirk (1997), Diachronic prototype Semantics: a contribution to historical lexicology, Oxford: Clarendon

- Grzega, Joachim (2004), Bezeichnungswandel: Wie, Warum, Wozu? Ein Beitrag zur englischen und allgemeinen Onomasiologie, Heidelberg: Winter

- Grzega, Joachim; Schöner, Marion (2007), English and general historical lexicology: materials for onomasiology seminars (PDF), Eichstätt: Universität

- Jeffers, Robert J.; Lehiste, Ilse (1979), Principles and methods for historical linguistics, MIT press, ISBN 0-262-60011-0

- Paul, Hermann (1880), Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte, Tübingen: Niemeyer

- Reisig, Karl (1839), «Semasiologie oder Bedeutungslehre», in Haase, Friedrich (ed.), Professor Karl Reisigs Vorlesungen über lateinische Sprachwissenschaft, Leipzig: Lehnhold

- Stern, Gustaf (1931), Meaning and change of meaning with special reference to the English language, Göteborg: Elander

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs (1990), «From less to more situated in language: the unidirectionality of Semantic change», in Adamson, Silvia; Law, Vivian A.; Vincent, Nigel; Wright, Susan (eds.), Papers from the Fifth International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 496–517

- Trier, Jost (1931), Der deutsche Wortschatz im Sinnbezirk des Verstandes (dissertation)

- Ullmann, Stephen (1957), Principles of Semantics (2nd ed.), Oxford: Blackwell

- Ullmann, Stephen (1962), Semantics: An introduction to the science of meaning, Oxford: Blackwell

- Vanhove, Martine (2008), From Polysemy to Semantic change: Towards a Typology of Lexical Semantic Associations, Studies in Language Companion Series 106, Amsterdam, New York: Benjamins.

- Warren, Beatrice (1992), Sense Developments: A contrastive study of the development of slang senses and novel standard senses in English, [Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 80], Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell

- Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1-4039-1723-X.

Further reading[edit]

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2015) «Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: A Study of the Polysemy of Verbs»

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2016) «From dašš l-ġōṣ to dašš twitar: Semantic Change in Kuwaiti Arabic»

- AlBader, Yousuf B. (2017) «Polysemy and Semantic Change in the Arabic Language and Dialects»

- Grzega, Joachim (2000), «Historical Semantics in the Light of Cognitive Linguistics: Aspects of a new reference book reviewed», Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 25: 233–244.

- Koch, Peter (2002), «Lexical typology from a cognitive and linguistic point of view», in: Cruse, D. Alan et al. (eds.), Lexicology: An international handbook on the nature and structure of words and vocabularies/lexikologie: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen, [Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 21], Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 1, 1142–1178.

- Wundt, Wilhelm (1912), Völkerpsychologie: Eine Untersuchung der Entwicklungsgesetze von Sprache, Mythus und Sitte, vol. 2,2: Die Sprache, Leipzig: Engelmann.

External links[edit]

- Onomasiology Online (internet platform by Joachim Grzega, Alfred Bammesberger and Marion Schöner, including a list of etymological dictionaries)

- Etymonline, Online Etymology Dictionary of the English language.

- Exploring Word Evolution An online analysis tool for studying evolution of any input words based on Google Books n-gram dataset and the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA).