A sign in a shop window in Italy proclaims these silent clocks make «No Tic Tac» [sic], in imitation of the sound of a clock.

Onomatopoeia[note 1] is the use or creation of a word that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Such a word itself is also called an onomatopoeia. Common onomatopoeias include animal noises such as oink, meow (or miaow), roar, and chirp. Onomatopoeia can differ between languages: it conforms to some extent to the broader linguistic system;[6][7] hence the sound of a clock may be expressed as tick tock in English, tic tac in Spanish and Italian (shown in the picture), dī dā in Mandarin, kachi kachi in Japanese, or tik-tik in Hindi.

The English term comes from the Ancient Greek compound onomatopoeia, ‘name-making’, composed of onomato— ‘name’ and —poeia ‘making’. Thus, words that imitate sounds can be said to be onomatopoeic or onomatopoetic.[8]

Uses

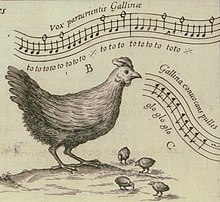

According to Musurgia Universalis (1650), the hen makes «to to too», while chicks make «glo glo glo».

In the case of a frog croaking, the spelling may vary because different frog species around the world make different sounds: Ancient Greek brekekekex koax koax (only in Aristophanes’ comic play The Frogs) probably for marsh frogs; English ribbit for species of frog found in North America; English verb croak for the common frog.[9]

Some other very common English-language examples are hiccup, zoom, bang, beep, moo, and splash. Machines and their sounds are also often described with onomatopoeia: honk or beep-beep for the horn of an automobile, and vroom or brum for the engine. In speaking of a mishap involving an audible arcing of electricity, the word zap is often used (and its use has been extended to describe non-auditory effects of interference).

Human sounds sometimes provide instances of onomatopoeia, as when mwah is used to represent a kiss.[10]

For animal sounds, words like quack (duck), moo (cow), bark or woof (dog), roar (lion), meow/miaow or purr (cat), cluck (chicken) and baa (sheep) are typically used in English (both as nouns and as verbs).

Some languages flexibly integrate onomatopoeic words into their structure. This may evolve into a new word, up to the point that the process is no longer recognized as onomatopoeia. One example is the English word bleat for sheep noise: in medieval times it was pronounced approximately as blairt (but without an R-component), or blet with the vowel drawled, which more closely resembles a sheep noise than the modern pronunciation.

An example of the opposite case is cuckoo, which, due to continuous familiarity with the bird noise down the centuries, has kept approximately the same pronunciation as in Anglo-Saxon times and its vowels have not changed as they have in the word furrow.

Verba dicendi (‘words of saying’) are a method of integrating onomatopoeic words and ideophones into grammar.

Sometimes, things are named from the sounds they make. In English, for example, there is the universal fastener which is named for the sound it makes: the zip (in the UK) or zipper (in the U.S.) Many birds are named after their calls, such as the bobwhite quail, the weero, the morepork, the killdeer, chickadees and jays, the cuckoo, the chiffchaff, the whooping crane, the whip-poor-will, and the kookaburra. In Tamil and Malayalam, the word for crow is kaakaa. This practice is especially common in certain languages such as Māori, and so in names of animals borrowed from these languages.

Cross-cultural differences

Although a particular sound is heard similarly by people of different cultures, it is often expressed through the use of different consonant strings in different languages. For example, the snip of a pair of scissors is cri-cri in Italian,[11] riqui-riqui in Spanish,[11] terre-terre[11] or treque-treque[citation needed] in Portuguese, krits-krits in modern Greek,[11] cëk-cëk in Albanian,[citation needed] and katr-katr in Hindi.[citation needed] Similarly, the «honk» of a car’s horn is ba-ba (Han: 叭叭) in Mandarin, tut-tut in French, pu-pu in Japanese, bbang-bbang in Korean, bært-bært in Norwegian, fom-fom in Portuguese and bim-bim in Vietnamese.[citation needed]

Onomatopoeic effect without onomatopoeic words

An onomatopoeic effect can also be produced in a phrase or word string with the help of alliteration and consonance alone, without using any onomatopoeic words. The most famous example is the phrase «furrow followed free» in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The words «followed» and «free» are not onomatopoeic in themselves, but in conjunction with «furrow» they reproduce the sound of ripples following in the wake of a speeding ship. Similarly, alliteration has been used in the line «as the surf surged up the sun swept shore …» to recreate the sound of breaking waves in the poem «I, She and the Sea».

Comics and advertising

A sound effect of breaking a door

Comic strips and comic books make extensive use of onomatopoeia. Popular culture historian Tim DeForest noted the impact of writer-artist Roy Crane (1901–1977), the creator of Captain Easy and Buz Sawyer:

- It was Crane who pioneered the use of onomatopoeic sound effects in comics, adding «bam,» «pow» and «wham» to what had previously been an almost entirely visual vocabulary. Crane had fun with this, tossing in an occasional «ker-splash» or «lickety-wop» along with what would become the more standard effects. Words as well as images became vehicles for carrying along his increasingly fast-paced storylines.[12]

In 2002, DC Comics introduced a villain named Onomatopoeia, an athlete, martial artist, and weapons expert, who often speaks pure sounds.[clarification needed]

Advertising uses onomatopoeia for mnemonic purposes, so that consumers will remember their products, as in Alka-Seltzer’s «Plop, plop, fizz, fizz. Oh, what a relief it is!» jingle, recorded in two different versions (big band and rock) by Sammy Davis, Jr.

Rice Krispies (US and UK) and Rice Bubbles (AU)[clarification needed] make a «snap, crackle, pop» when one pours on milk. During the 1930s, the illustrator Vernon Grant developed Snap, Crackle and Pop as gnome-like mascots for the Kellogg Company.

Sounds appear in road safety advertisements: «clunk click, every trip» (click the seatbelt on after clunking the car door closed; UK campaign) or «click, clack, front and back» (click, clack of connecting the seat belts; AU campaign) or «click it or ticket» (click of the connecting seat belt, with the implied penalty of a traffic ticket for not using a seat belt; US DOT (Department of Transportation) campaign).

The sound of the container opening and closing gives Tic Tac its name.

Manner imitation

In many of the world’s languages, onomatopoeic-like words are used to describe phenomena beyond the purely auditive. Japanese often uses such words to describe feelings or figurative expressions about objects or concepts. For instance, Japanese barabara is used to reflect an object’s state of disarray or separation, and shiiin is the onomatopoetic form of absolute silence (used at the time an English speaker might expect to hear the sound of crickets chirping or a pin dropping in a silent room, or someone coughing). In Albanian, tartarec is used to describe someone who is hasty. It is used in English as well with terms like bling, which describes the glinting of light on things like gold, chrome or precious stones. In Japanese, kirakira is used for glittery things.

Examples in media

- James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) coined the onomatopoeic tattarrattat for a knock on the door.[13] It is listed as the longest palindromic word in The Oxford English Dictionary.[14]

- Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein is an early example of pop art, featuring a reproduction of comic book art that depicts a fighter aircraft striking another with rockets with dazzling red and yellow explosions.

- In the 1960s TV series Batman, comic book style onomatopoeic words such as wham!, pow!, biff!, crunch! and zounds! appear onscreen during fight scenes.

- Ubisoft’s XIII employed the use of comic book onomatopoeic words such as bam!, boom! and noooo! during gameplay for gunshots, explosions and kills, respectively. The comic-book style is apparent throughout the game and is a core theme, and the game is an adaptation of a comic book of the same name.

- The chorus of American popular songwriter John Prine’s song «Onomatopoeia» incorporates onomatopoeic words: «Bang! went the pistol», «Crash! went the window», «Ouch! went the son of a gun».

- The marble game KerPlunk has an onomatopoeic word for a title, from the sound of marbles dropping when one too many sticks has been removed.

- The Nickelodeon cartoon’s title KaBlam! is implied to be onomatopoeic to a crash.

- Each episode of the TV series Harper’s Island is given an onomatopoeic name which imitates the sound made in that episode when a character dies. For example, in the episode titled «Bang» a character is shot and fatally wounded, with the «Bang» mimicking the sound of the gunshot.

- Mad Magazine cartoonist Don Martin, already popular for his exaggerated artwork, often employed creative comic-book style onomatopoeic sound effects in his drawings (for example, thwizzit is the sound of a sheet of paper being yanked from a typewriter). Fans have compiled The Don Martin Dictionary, cataloging each sound and its meaning.

Cross-linguistic examples

In linguistics

A key component of language is its arbitrariness and what a word can represent,[clarification needed] as a word is a sound created by humans with attached meaning to said sound.[15] No one can determine the meaning of a word purely by how it sounds. However, in onomatopoeic words, these sounds are much less arbitrary; they are connected in their imitation of other objects or sounds in nature. Vocal sounds in the imitation of natural sounds doesn’t necessarily gain meaning, but can gain symbolic meaning.[clarification needed][16] An example of this sound symbolism in the English language is the use of words starting with sn-. Some of these words symbolize concepts related to the nose (sneeze, snot, snore). This does not mean that all words with that sound relate to the nose, but at some level we recognize a sort of symbolism associated with the sound itself. Onomatopoeia, while a facet of language, is also in a sense outside of the confines of language.[17]

In linguistics, onomatopoeia is described as the connection, or symbolism, of a sound that is interpreted and reproduced within the context of a language, usually out of mimicry of a sound.[18] It is a figure of speech, in a sense. Considered a vague term on its own, there are a few varying defining factors in classifying onomatopoeia. In one manner, it is defined simply as the imitation of some kind of non-vocal sound using the vocal sounds of a language, like the hum of a bee being imitated with a «buzz» sound. In another sense, it is described as the phenomena of making a new word entirely.

Onomatopoeia works in the sense of symbolizing an idea in a phonological context, not necessarily constituting a direct meaningful word in the process.[19] The symbolic properties of a sound in a word, or a phoneme, is related to a sound in an environment, and are restricted in part by a language’s own phonetic inventory, hence why many languages can have distinct onomatopoeia for the same natural sound. Depending on a language’s connection to a sound’s meaning, that language’s onomatopoeia inventory can differ proportionally. For example, a language like English generally holds little symbolic representation when it comes to sounds, which is the reason English tends to have a smaller representation of sound mimicry then a language like Japanese that overall has a much higher amount of symbolism related to the sounds of the language.

Evolution of language

In ancient Greek philosophy, onomatopoeia was used as evidence for how natural a language was: it was theorized that language itself was derived from natural sounds in the world around us. Symbolism in sounds was seen as deriving from this.[20] Some linguists hold that onomatopoeia may have been the first form of human language.[17]

Role in early language acquisition

When first exposed to sound and communication, humans are biologically inclined to mimic the sounds they hear, whether they are actual pieces of language or other natural sounds.[21] Early on in development, an infant will vary his/her utterances between sounds that are well established within the phonetic range of the language(s) most heavily spoken in their environment, which may be called «tame» onomatopoeia, and the full range of sounds that the vocal tract can produce, or «wild» onomatopoeia.[19] As one begins to acquire one’s first language, the proportion of «wild» onomatopoeia reduces in favor of sounds which are congruent with those of the language they are acquiring.

During the native language acquisition period, it has been documented that infants may react strongly to the more wild-speech features to which they are exposed, compared to more tame and familiar speech features. But the results of such tests are inconclusive.

In the context of language acquisition, sound symbolism has been shown to play an important role.[16] The association of foreign words to subjects and how they relate to general objects, such as the association of the words takete and baluma with either a round or angular shape, has been tested to see how languages symbolize sounds.

In other languages

Japanese

The Japanese language has a large inventory of ideophone words that are symbolic sounds. These are used in contexts ranging from day to day conversation to serious news.[22] These words fall into four categories:

- Giseigo: mimics humans and animals. (e.g. wanwan for a dog’s bark)

- Giongo: mimics general noises in nature or inanimate objects. (e.g. zaazaa for rain on a roof)

- Gitaigo: describes states of the external world

- Gijōgo: describes psychological states or bodily feelings.

The two former correspond directly to the concept of onomatopoeia, while the two latter are similar to onomatopoeia in that they are intended to represent a concept mimetically and performatively rather than referentially, but different from onomatopoeia in that they aren’t just imitative of sounds. For example, shiinto represents something being silent, just as how an anglophone might say «clatter, crash, bang!» to represent something being noisy. That «representative» or «performative» aspect is the similarity to onomatopoeia.

Sometimes Japanese onomatopoeia produces reduplicated words.[20]

Hebrew

As in Japanese, onomatopoeia in Hebrew sometimes produces reduplicated verbs:[23]: 208

-

- שקשק shikshék «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 207

- רשרש rishrésh «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 208

Malay

There is a documented correlation within the Malay language of onomatopoeia that begin with the sound bu- and the implication of something that is rounded, as well as with the sound of -lok within a word conveying curvature in such words like lok, kelok and telok (‘locomotive’, ‘cove’, and ‘curve’ respectively).[24]

Arabic

The Qur’an, written in Arabic, documents instances of onomatopoeia.[17] Of about 77,701 words, there are nine words that are onomatopoeic: three are animal sounds (e.g., «mooing»), two are sounds of nature (e.g.; «thunder»), and four that are human sounds (e.g., «whisper» or «groan»).

Albanian

There is wide array of objects and animals in the Albanian language that have been named after the sound they produce. Such onomatopoeic words are shkrepse (matches), named after the distinct sound of friction and ignition of the match head; take-tuke (ashtray) mimicking the sound it makes when placed on a table; shi (rain) resembling the continuous sound of pouring rain; kukumjaçkë (Little owl) after its «cuckoo» hoot; furçë (brush) for its rustling sound; shapka (slippers and flip-flops); pordhë (loud flatulence) and fëndë (silent flatulence).

Hindi-Urdu

In Hindi and Urdu, onomatopoeic words like bak-bak, churh-churh are used to indicate silly talk. Other examples of onomatopoeic words being used to represent actions are fatafat (to do something fast), dhak-dhak (to represent fear with the sound of fast beating heart), tip-tip (to signify a leaky tap) etc. Movement of animals or objects is also sometimes represented with onomatopoeic words like bhin-bhin (for a housefly) and sar-sarahat (the sound of a cloth being dragged on or off a piece of furniture). khusr-phusr refers to whispering. bhaunk means bark.

See also

- Anguish Languish

- Japanese sound symbolism

- List of animal sounds

- List of onomatopoeias

- Sound mimesis in various cultures

- Sound symbolism

- Vocal learning

Notes

- ^ ;[1][2] from the Greek ὀνοματοποιία;[3] ὄνομα for «name»[4] and ποιέω for «I make»,[5] adjectival form: «onomatopoeic» or «onomatopoetic»; also onomatopœia

References

Citations

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2

- ^ ὀνοματοποιία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ὄνομα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ποιέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle, Hugh Bredin, The Johns Hopkins University, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ Definition of Onomatopoeia, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ onomatopoeia at merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Basic Reading of Sound Words-Onomatopoeia, Yale University, retrieved October 11, 2013

- ^ «English Oxford Living Dictionaries». Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Earl R. (1998). A Grammar of Iconism. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780838637647.

- ^ DeForest, Tim (2004). Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio: How Technology Changed Popular Fiction in America. McFarland. ISBN 9780786419029.

- ^ James Joyce (1982). Ulysses. Editions Artisan Devereaux. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-1-936694-38-9.

… I was just beginning to yawn with nerves thinking he was trying to make a fool of me when I knew his tattarrattat at the door he must …

- ^ O.A. Booty (January 1, 2002). Funny Side of English. Pustak Mahal. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-81-223-0799-3.

The longest palindromic word in English has twelve letters: tattarrattat. This word, appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary, was invented by James Joyce and used in his book Ulysses (1922), and is an imitation of the sound of someone [farting].

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (January 1, 2011). «The anatomy of onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ a b RHODES, R (1994). «Aural Images». In J. Ohala, L. Hinton & J. Nichols (Eds.) Sound Symbolism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Seyedi, Hosein; Baghoojari, ELham Akhlaghi (May 2013). «The Study of Onomatopoeia in the Muslims’ Holy Write: Qur’an» (PDF). Language in India. 13 (5): 16–24.

- ^ Bredin, Hugh (August 1, 1996). «Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle». New Literary History. 27 (3): 555–569. doi:10.1353/nlh.1996.0031. ISSN 1080-661X. S2CID 143481219.

- ^ a b Laing, C. E. (September 15, 2014). «A phonological analysis of onomatopoeia in early word production». First Language. 34 (5): 387–405. doi:10.1177/0142723714550110. S2CID 147624168.

- ^ a b Osaka, Naoyuki (1990). «Multidimensional Analysis of Onomatopoeia – A note to make sensory scale from word». Studia phonologica. 24: 25–33. hdl:2433/52479. NAID 120000892973.

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (December 14, 2011). «The Anatomy of Onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ Inose, Hiroko. «Translating Japanese Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words.» N.p., n.d. Web.

- ^ a b c Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ WILKINSON, R. J. (January 1, 1936). «Onomatopoeia in Malay». Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 14 (3 (126)): 72–88. JSTOR 41559855.

General references

- Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55967-7.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. p. 680. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.

External links

- Derek Abbott’s Animal Noise Page

- Over 300 Examples of Onomatopoeia

- BBC Radio 4 show discussing animal noises

- Tutorial on Drawing Onomatopoeia for Comics and Cartoons (using fonts)

- WrittenSound, onomatopoeic word list

- Examples of Onomatopoeia

What is Onomatopoeia?

Onomatopoeia Definition

Onomatopoeia indicates a word that sounds like what it refers to or describes. The letter sounds combined in the word mimic the natural sound of the object or action, such as hiccup. A word is considered onomatopoetic if its pronunciation is a vocal imitation of the sound associated with the word.

Use of Onomatopoeia in Literature

Onomatopoeia is used by writers and poets as figurative language to create a heightened experience for the reader. Onomatopoetic words are descriptive and provide a sensory effect and vivid imagery in terms of sight and sound. This literary device is prevalent in poetry, as onomatopoetic words are also conducive to rhymes.

Common Examples of Onomatopoeia

- The buzzing bee flew away.

- The sack fell into the river with a splash.

- The books fell on the table with a loud thump.

- He looked at the roaring

- The rustling leaves kept me awake.

The different sounds of animals are also considered as examples of onomatopoeia. You will recognize the following sounds easily:

- Meow

- Moo

- Neigh

- Tweet

- Oink

- Baa

Groups of Onomatopoeic Words

Onomatopoeic words come in combinations, as they reflect different sounds of a single object. For example, a group of words reflecting different sounds of water are: plop, splash, gush, sprinkle, drizzle, and drip.

Similarly, words like growl, giggle, grunt, murmur, blurt, and chatter denote different kinds of human voice sounds.

Moreover, we can identify a group of words related to different sounds of wind, such as swish, swoosh, whiff, whoosh, whizz, and whisper.

Onomatopoeia in Comics

Comics show their own examples of different types of onomatopoeia. Different comics use different panels where bubbles show different types of sounds. Although sometimes authors and illustrators show the exact sounds of animals, or the sound of the falling of something or some machines, somethings they create their own sounds as well. These sounds depend upon the inventiveness of the illustrator as well as the writer. Most of these sounds are crash, zap, pow, bang, or repetition of different letters in quick succession intended to create an impression of sounds.

Impacts of Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia not only creates rhythm but also beats, as the poets try to create sounds imitating the sound creators. These sounds create a sensory impression in the minds of the readers which they understand. The readers also understand the impacts of the sounds, their likely meanings, and their roles in creating those meanings. When used in poetry, onomatopoeia creates a rhythmic pattern that imitates the sounds in reality. This vice versa movement of sounds shows the onomatopoeic use of words to create a metrical pattern and rhyme scheme.

Use of Onomatopoeia in Sentences

- When cats are crying miaow, miaow, it means they are hungry.

- As soon as the mother heard the bell sing ding dong, she excitedly ran to open the door.

- When he fell down, there was a ‘whoosh’ he caused a big splash in the water which caused the other swimmers to get up.

- When Mathew dropped his mobile, he heard a ‘crash’ that made him cry immediately.

- Once upon a time, Jeanie rubbed an old lamp and ‘poof’ a real genie appeared in front of her.

Examples of Onomatopoeia in Literature

Onomatopoeia is frequently employed in the literature. We notice, in the following examples, the use of onomatopoeia gives rhythm to the texts. This makes the descriptions livelier and more interesting, appealing directly to the senses of the reader.

Below, a few Onomatopoeia examples are highlighted in bold letters:

Example #1: Come Down, O Maid By Alfred Lord Tennyson

“The moan of doves in immemorial elms,

And murmuring of innumerable bees…”

Example #2: The Tempest By William Shakespeare

“Hark, hark!

Bow-wow.

The watch-dogs bark!

Bow-wow.

Hark, hark! I hear

The strain of strutting chanticleer

Cry, ‘cock-a-diddle-dow!’”

Example #3: For Whom the Bell Tolls By Ernest Hemingway

“He saw nothing and heard nothing but he could feel his heart pounding and then he heard the clack on stone and the leaping, dropping clicks of a small rock falling.”

Example #4: The Marvelous Toy By Tom Paxton

“It went zip when it moved and bop when it stopped,

And whirr when it stood still.

I never knew just what it was and I guess I never will.”

Example #5: Get Me to the Church on Time By Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe

“I’m getting married in the morning!

Ding dong! the bells are gonna chime.”

Examples #6: The Bells by Edgar Allen Poe

Keeping time, time, time,

As he knells, knells, knells,

In a happy Runic rhyme,

To the rolling of the bells—

Of the bells, bells, bells—

To the tolling of the bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells—

Bells, bells, bells—

To the moaning and the groaning of the bells.

Onomatopoeia and Phanopoeia

Onomatopoeia, in its more complicated use, takes the form of phanopoeia. Phanopoeia is a form of onomatopoeia that describes the sense of things, rather than their natural sounds. D. H. Lawrence, in his poem Snake, illustrates the use of this form:

“He reached down from a fissure in the earth-wall in the gloom

And trailed his yellow-brown slackness soft-bellied down, over the

edge of the stone trough

And rested his throat upon the stone bottom,

And where the water had dripped from the tap, in a small clearness

He sipped with his straight mouth…”

The rhythm and length of the above lines, along with the use of “hissing” sounds, create a picture of a snake in the minds of the readers.

Function of Onomatopoeia

Generally, words are used to tell what is happening. Onomatopoeia, on the other hand, helps readers to hear the sounds of the words they reflect. Hence, the reader cannot help but enter the world created by the poet with the aid of these words. The beauty of onomatopoeic words lies in the fact that they are bound to have an effect on the readers’ senses, whether that effect is understood or not. Moreover, a simple plain expression does not have the same emphatic effect that conveys an idea powerfully to the readers. The use of onomatopoeic words helps create emphasis.

Synonyms of Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia does not have any synonyms. However, some words come very close to it in meanings such as sounds, imitation of sounds, onomatope, alliteration, echo, echoism, and mimesis. Yet, they have different meanings of their own.

What is onomatopoeia? To describe it in a zip, an onomatopoeia is a word that smacks the reader’s ears and makes them pop. Onomatopoeia words describe sounds by copying the sound itself.

Crash! Bang! Whiz! An onomatopoeia doesn’t just describe sounds, it emulates the sound itself. With this literary device, you can hear the meow of a cat, the whoosh of a bicycle, the whir of the laundry machine, and the murmur of a stream.

While some onomatopoeia words might seem juvenile to use, there are many more words to choose from. These sound devices can texture your writing with style and flare, while also drawing the reader into the world of your writing. So, let’s listen to this delightful tool that revs in the writer’s toolkit. We’ll take a look at some onomatopoeia examples in literature and discuss the surprising poetics of this euphonious device.

But first, let’s start with the basics, defining what an onomatopoeia is and isn’t. what is onomatopoeia?

Contents

- Onomatopoeia Definition

- Onomatopoeia vs Phanopoeia

- How to Pronounce Onomatopoeia

- Onomatopoeia Examples in Literature

- Onomatopoeia Words

- A Note on the Translation of Onomatopoeia Words

- Why Use Onomatopoeia in Your Writing?

Onomatopoeia Definition

An onomatopoeia is a word that sounds like the noise it describes. The spelling and pronunciation of that word is directly influenced by the sound it defines in real life. All onomatopoeia words describe specific sounds.

Onomatopoeia definition: a word that sounds like the noise it describes.

Some onomatopoeia examples include the words boing, gargle, clap, zap, and pitter-patter. When these words are used in context, you can almost hear what they describe: the boing of a spring, the clap of chalkboard erasers, and the pitter-patter of rain falling on the pavement like tiny footsteps.

Including onomatopoeia words in your writing can enhance the imagery of your story or poem. Technically, onomatopoeia is not a form of auditory imagery, because auditory imagery is the use of figurative language (like similes and metaphors) to describe sound. But, an onomatopoeia can certainly complement auditory imagery, as both devices heighten the sonic qualities of the work.

Note that not all onomatopoeia words are words listed in the dictionary. Many authors have made up their own sounds to complement their writing. In our onomatopoeia examples, you’ll see nonce words like “skulch,” “glush,” and “pit-a-pat.”

Sometimes, when these nonce onomatopoeia words are used often enough in everyday speech, they become dictionary entries. The etymology for “tattarrattat” is James Joyce’s Ulysses. It is also the longest palindrome in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Onomatopoeia vs Phanopoeia

A relative of onomatopoeia, phanopoeia is a literary device in which the general sensation of something is emulated in the sounds of the words that the author uses.

This is easier demonstrated than explained. Read this short poem below, by Franz Wright:

Heaven

I lived as a monster, my only

hope is to die like a child.

In the otherwise vacant

and seemingly ceilingless

vastness of a snowlit Boston

church, a voice

said: I

can do that–if you ask me, I will do it

for you.

In bold is phanopoeia. The repetition of “s” sounds, as well as the spaciousness of the poem’s stanza breaks, resembles the sounds of echoes in a mostly empty church. The reader can experience the vastness of the church through alliteration and stanza breaks. There is a sonic and spacious quality to the poem that the reader, if attentive, can climb into and never leave. The poem does not have onomatopoeia, however: none of the words used are emulating real life sounds.

How to Pronounce Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is pronounced “On-oh-mah-tow-pee-uh.” The bolded syllables are stressed.

It’s a weird looking word, right? Onomatopoeia comes from the Greek “onoma” (word or name) + “poiein” (to make). In other words, this literary device is “word making,” as these words are invented using the sounds that they describe.

Poiein is also the root of the modern words “poet” and “poetry,” as the Greeks viewed the act of writing poetry as an act of invention, creating something from nothing.

Onomatopoeia Examples in Literature

Let’s take a look at how authors have used this device in some onomatopoeia examples.

“The Pied Piper of Hamelin” by Robert Browning

Read the full poem here.

Just as he said this, what should hap

At the chamber door but a gentle tap?

Bless us, cried the Mayor, what’s that?

(With the Corporation as he sate,

Looking little though wondrous fat);

Only a scraping of shoes on the mat?

Anything like the sound of a rat

Makes my heart go pit-a-pat!

This poem, which is about the invasion of rats in a town called Hamelin, makes frequent use of onomatopoeia to emulate the sounds of scurrying rodents. Words like tap, scrape, and pit-a-pat situate the reader into the narrative poem’s anxiety and rat problems.

“I Heard a Fly Buzz—When I Died” by Emily Dickinson

Read the full poem here.

I willed my Keepsakes—Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable—and then it was

There interposed a Fly—

With Blue—uncertain—stumbling Buzz—

Between the light—and me—

And then the Windows failed—and then

I could not see to see—

There’s only one onomatopoeia here, and that’s the word buzz. The poem’s speaker hears this one final sound before her death. Thus, the buzzing carries a dual meaning: it is both figuratively and literally the only sound of the poem, and after that, silence.

“Honky Tonk in Cleveland, Ohio” by Carl Sandburg

Read the full poem here.

It’s a jazz affair, drum crashes and cornet razzes.

The trombone pony neighs and the tuba jackass snorts.

The banjo tickles and titters too awful.

The chippies talk about the funnies in the papers.

The cartoonists weep in their beer.

The chaotic, cacophonous sounds of this poem perfectly emulate the feeling of being in a jazz bar. The instruments mixed with the peoples’ conversations overwhelms the reader, and the poem’s structured improvisation resembles jazz itself.

For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

Read the full text here.

He saw nothing and heard nothing but he could feel his heart pounding and then he heard the clack on stone and the leaping, dropping clicks of a small rock falling.

This brief line offers so much context and imagery. With only the onomatopoeia words “pounding,” “clack,” and “clicks,” the reader can imagine a man standing at the edge of a cliff, overwhelmed by the grand endlessness of the world, feeling the terror of falling as pebbles skitter down the rocky earth.

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Read the full poem here.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door—

“‘Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

This poem’s tapping and rapping are so repetitive, the reader must feel how the speaker does—distracted and overwhelmed by an incessant sound. Poe is a master of using language to emulate sound: another poem of his, “The Bells,” repeats use of the word “bells” so much that the poem itself begins to jingle.

“The Weary Blues” by Langston Hughes

Read the full poem here.

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan—

“Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more—

Langston Hughes is a prominent voice of the Harlem Renaissance, capturing the sound and vitality of mid-century Harlem, New York. This poem’s sounds and overall musicality capture the liveliness of the era, situating the reader in the sweet and soulful atmosphere of a blue’s bar.

Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce

Read the full text (with annotations) here.

The fall (bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonner-ronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthur-nuk!) of a once wallstrait oldparr is retaled early in bed and later on life down through all christian minstrelsy.

James Joyce is famous for inventing and torturing language—to the point that native English speakers don’t recognize their own mother tongue. That long bababada word is an onomatopoeia that is supposed to represent the sound of thunder during the fall of Adam and Eve. While this nonce word may seem nonsensical, it actually pulls from a variety of languages, including the word “thunder” in Swedish, Hindi, Japanese, Danish, Gaelic, French, Italian, and Portuguese.

“I Was Sitting in McSorley’s” by E. E. Cumming

Read the full poem here.

the Bar.tinking luscious jigs dint of ripe silver with warm-lyish wetflat splurging smells waltz the glush of squirting taps plus slush of foam knocked off and a faint piddle-of-drops she says I ploc spittle what the lands thaz me kid in no sir hopping sawdust you kiddo

he’s a palping wreaths of badly Yep cigars who jim him why gluey grins topple together eyes pout gestures stickily point made glints squinting who’s a wink bum-nothing and money fuzzily mouths take big wobbly foot

steps every goggle cent of it get out ears dribbles soft right old feller belch the chap hic summore eh chuckles skulch. . . .

E. Cummings’ Modernist poetry sought to translate experiences exactly as they happened. In “I Was Sitting in McSorley’s,” that experience is being drunk in a famous bar in the East Village, Manhattan. Cummings uses a variety of onomatopoeia words to capture the sounds and iniquities of the bar: real words, like tinking and slush, capture the sounds of drinks and glasses. But also, made-up words like glush, skulch, and ploc have a more disgusting sound to them, attempting to represent the grossness of the bar.

“Cynthia in the Snow” by Gwendolyn Brooks

It SHUSHES.

It hushes

The loudness in the road.

It flitter-twitters,

And laughs away from me.

It laughs a lovely whiteness,

And whitely whirs away,

To be

Some otherwhere,

Still white as milk or shirts.

So beautiful it hurts.

This poem has great onomatopoeia examples and phanopoeia examples. The repeated “sh” sounds make this poem feel blanketed by snow. You know how, after the first snowfall, the entire world is hushed? How there’s barely a breeze and no one outside and the sounds are muffled in blankets of “lovely whiteness”? This poem captures that through sound, making it an excellent onomatopoeia poem.

“TV People” by Haruki Murakami

You can find an archive of this story here. Originally published in The New Yorker, and then in Murakami’s collection The Elephant Vanishes.

The TV people exit and leave me alone. My sense of reality comes back to me. These hands are once again my hands. It’s only then I notice that the dusk has been swallowed by darkness. I turn on the light. Then I close my eyes. Yes, that’s a TV set sitting there. Meanwhile, the clock keeps ticking away the minutes. TRPP Q SCHAOUS TRPP Q SCHAOUS

Murakami is an endlessly inventive storyteller, and what I love most about this onomatopoeia example is how specific the sound is. Rather than describe a simple “swish” or “whir” of a moving pendulum, Murakami invents something that feels incessant, swift, and mechanical. When you try to speak this onomatopoeia out loud, you come pretty close to speaking the sound.

Onomatopoeia Words

The following onomatopoeia list includes examples of the device that can be found in the dictionary.

Make note of two things: first, there are many onomatopoeia examples that exist outside of the dictionary. Because these words attempt to represent real sounds, they can be made up for whatever occasion in your own writing.

Second, some onomatopoeia words have multiple definitions. “Jingle,” for example, sounds like Christmas bells, but it also means a catchy song for advertising.

Some onomatopoeia words have multiple definitions. “Jingle,” for example, sounds like Christmas bells, but it also means a catchy song for advertising.

Try to use these fun sound words in your own writing!

General sounds

- achoo

- bam

- bang

- bash

- beep

- belch

- blah

- blab

- blast

- blow

- boing

- boo

- boom

- boop

- burp

- buzz

- cha-ching

- chortle

- clack

- clackety-clack

- clang

- click

- clink

- clap

- clang

- clop

- creak

- crunch

- crackle

- ding

- ding-dong

- dong

- doink

- drip

- fizzle

- flap

- flick

- flop

- flush

- gargle

- gibber

- groan

- grunt

- gulp

- gurgle

- gush

- hiccup

- honk

- hum

- jingle

- kaboom

- kapow

- kerplunk

- knock

- lurch

- mumble

- munch

- natter

- patter

- ping

- plop

- plunk

- pong

- pop

- pow

- puff

- pulse

- rap

- raspy

- rattle

- ring

- rumble

- rustle

- scrape

- shuffle

- sizzle

- slam

- slash

- slosh

- slurp

- snap

- spit

- splash

- split

- swish

- swoosh

- thud

- thump

- tick

- ting

- tock

- toot

- twang

- vroom

- whip

- yackety-yack

- yak

- yammer

- yap

- zap

- zing

- zip

- zoom

Animals

- arf

- bark

- bleat

- bow-wow

- bray

- buzz

- chirp

- chomp

- clip-clop

- cluck

- cock a doodle doo

- coo

- cough

- croak

- croon

- crow

- cuckoo

- drone

- growl

- hiss

- hoot

- howl

- mew

- meow

- moo

- neigh

- oink

- peep

- purr

- quack

- ribbit

- roar

- ruff

- screech

- sniff

- snort

- splat

- squawk

- squish

- squeak

- squelch

- thwack

- tweet

- warble

- wallop

- woof

- wolf

Expletives

- ah

- aha

- ahem

- argh

- eek

- ew

- guffaw

- ha-ha

- hmm

- hoho

- huh

- ohh

- phew

- ugh

- uhh

- um

Objects

- awooga

- ba dum tss

- brring

- chime

- choo-choo

- clogs

- clunker

- crash

- crinkle

- flip-flop

- gong

- oom-pah

- pew-pew

- popcorn

- rap

- tap

- wail

- whistle

A Note on the Translation of Onomatopoeia Words

Onomatopoeia words present an interesting conundrum to linguists and translators. Because these devices seek to directly emulate sound, one would assume that onomatopoeia words are the same across languages.

Oddly enough, this isn’t the case. For example, while in English the sound a dog makes is “woof” or “arf,” some Spanish speakers represent the dog’s bark as “guau;” in Japanese, “wan wan,” and in Catalan, “taula.”

How can this be? If you just speak English, you probably won’t hear “taula” no matter how much you listen to your dog. This conundrum points towards the unconscious ways that language shapes reality. The languages we speak restrict the sounds that we can produce and readily hear, so while an English speaker certainly hears their dog woof, a Japanese speaker undoubtedly hears their dog’s wan wan. (The Japanese language also possesses numerous onomatopoeia words, more than most languages do. Take a look at this list to see how Japanese language speakers hear sounds differently than English speakers.)

At the same time, many onomatopoeia examples in the English language come from Latin and Greek. “Bowwow,” for example, is influenced by the Latin baubor and the Greek bauzein, words which themselves are likely onomatopoeic. Of course, Latin and Greek root words make up about 60% of the English language dictionary. Perhaps that influences why we hear what the Ancient Greeks and Romans heard?

By noticing the ways that culture and language shape onomatopoeia words, you can also notice the many possible sounds that language hasn’t yet captured. The onomatopoeia is an experimental literary device, so play around with it, research how sounds are transcribed in other languages (for fun!), and lean into the possibilities of words and sounds.

Why Use Onomatopoeia in Your Writing?

Onomatopoeia words serve many different functions in writing. These include:

- Resembling Real Life. By capturing the sounds of everyday life in language, the writer makes the world of their story or poem much more accessible.

- Playing With Language. Onomatopoeia words can be very experimental, and whether the writer uses existing words or comes up with new onomatopoeia words, this device offers a playfulness with language that all writers should embrace.

- Drawing the Reader in. For the most part, readers love onomatopoeia words. These words are fun, interesting, and compelling to the reader, and they help establish the mood of a certain passage.

- Writing Comics. Comic book writers and graphic novel writers often rely on onomatopoeia words, both pre-existing and made-up, to show sound effects and keep the story interesting.

- Style. An easy way to add texture and variety to your writing style is with this literary device.

- Developing Mental Images. Although an onomatopoeia is not imagery on its own, it does help build a mental image of the writing’s sights and sounds. Imagery and “show, don’t tell writing” are essential tools in the author’s toolbox.

Explore Onomatopoeia at Writers.com

Want practice in fine tuning your onomatopoeia words? Whether you’re writing poetry or prose, the courses at Writers.com are designed to help every author on their writing journey. Take a look at our upcoming course schedule, where you’ll find courses for all writing levels that offer the support and structure you need.

Onomatopoeia definition: An onomatopoeia a word whose sound imitates its meaning. An onomatopoeia is a literary device.

What is an onomatopoeia? When a pronounced word sounds like the sound the word means, it is called an onomatopoeia.

This concept is best understood through example.

Examples of Onomatopoeia:

- Buzz

Other examples: stomp, clap, snap

All of these terms roughly sound like their meaning. When pronounced, “stomp” sounds like a stomp; “clap” sound like a clap; “snap” sound like a snap.

Onomatopoeias are frequently used in poetry as a way to create sound interest and double meaning.

Modern Examples of Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeias are used in everyday language even though their purpose may not be for literary effect.

- bang

- murmur

- smack

- pop

- ring

- ding

- clink

- sizzle

- thump

- thud

- screech

- bark (as a dog)

- meow (as a cat)

- hiss (as a snake)

When these words are pronounced, they sound like their meaning.

The Function of Onomatopoeia

When a writer includes an onomatopoeia, he does not need to write any additional terms to express sound or meaning.

Let’s look further at this example:

- Pop!

When a writer uses this term, he can simply state the word and the sound is included in the meaning.

He does not need to say: “The sound of the champagne opening made a noise like pop.”

Instead he can simply say, “Pop!” and the audience will understand the sound.

This makes writing more efficient, clear, and concise.

How Onomatopoeia is Used in Literature

Edgar Allan Poe’s poem, “The Bells,” utilizes onomatopoeia to reflect the sound he wants to describe. Here, the onomatopoeias also help to create tone and mood.

Here are excerpted lines from Part I of “The Bells:”

“How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle” (4)

“To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells” (11)

“From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.” (14)

The onomatopoeias “tinkle,” “tintinnabulation,” “jingling,” and “tinkling” reflect Poe’s purpose and create an effect as he describes the bells. The audience can “hear” the bells ringing as Poe uses onomatopoeia to set the mood for the poem.

Summary: What Does Onomatopoeia Mean?

Define Onomatopoeia: In summary, an onomatopoeia:

- is a literary device that sounds like its meaning

- is often used in everyday language

- is very effective in poetry

Contents

- 1 What is Onomatopoeia?

- 2 Modern Examples of Onomatopoeia

- 3 The Function of Onomatopoeia

- 4 How Onomatopoeia is Used in Literature

- 5 Summary: What Does Onomatopoeia Mean?

Onomatopoeia is something many of us briefly touched upon in primary school—cats meow, superheroes smash, bees buzz, doors bang—before discarding it in favor of elegant literary devices better suited to Serious Writers™. You might be surprised to learn that onomatopoeia doesn’t have to be restricted to children’s nursery rhymes and classic comic books; when used effectively, many onomatopoeic words can enhance auditory imagery and create a more vibrant, immersive story for your reader.

Let’s take a closer look at the onomatopoeia definition with some common examples of words, along with some example sentences, and how to use this literary device to make your writing pop.

What is onomatopoeia in writing?

Onomatopoeia is a literary device in which a word emulates a certain sound. The word “onomatopoeia” comes from the Greek and means “the making of a name or word.” Onomatopoeic words always sound like what they’re describing.

These might be animal sounds like a dog’s bark, the tick-tock of a clock, the ding-dong of a bell, a crackling fire, or the bang of a starter pistol. All of these sound words—bark, tick-tock, ding-dong, crackling, and bang—sound like what they describe when you say them out loud.

For example, describing a “rushing wind” gives the reader an idea of what the wind is doing, but it also brings the sound to life in the ear; “rush” is a little bit like what wind sounds like as it moves through tree branches.

Another onomatopoeia example might be a “screeching car.” Not only is this an action verb your readers will recognize, but it creates the sensation of sound on the page; you can imagine the “skreeeeech” sound as the car comes to a halt. All of these fun words work to describe sound in a clear and engaging way.

We’ll look at more examples of onomatopoeia below.

How to pronounce onomatopoeia

“Onomatopoeia” is a pretty big chunk of change to carry around in your mouth. Here’s how it’s pronounced: “ahn-uh-mat-uh-pee-uh,” hitting the first and second-last syllable.

Why do writers find onomatopoeia divisive?

You might notice on your creative writing journey that some writers tell you never to use onomatopoeia in adult fiction. Say huh? Does this mean your cars can’t screech, and your wind can’t rush, and your brooks can’t burble?

Well, no. Sometimes people say onomatopoeia shouldn’t be used because they don’t have a very clear idea of what it really is or what it can offer a story.

The biggest issue with onomatopoeia in literature comes from lack of subtlety and overuse. This can make your writing feel cliché. Here’s one onomatopoeia example:

They inched farther into the haunted house, and then—BANG! The door slammed shut behind them.

This sentence isn’t out of place in middle-grade fiction. But for a more mature audience, overt use of onomatopoeia can feel as though you’re leading your readers to the tension of the story rather than letting them discover it themselves. Consider instead:

They inched deeper into the house and, with a sudden whoosh of stagnant air, the door slammed shut behind them.

You actually still have onomatopoeia in this sentence, but in a smoother, more elegant way. The “whoosh” shows the reader the sound the door makes as it falls back towards the door frame, and “slammed” shows us the sound it makes as it connects (locking our heroes inside… forever…!). Here, you’re using onomatopoeia and figurative language to create the same level of tension without the reader even realizing you’re doing it.

Onomatopoeia vs. Phanopoeia

Another auditory literary device you might come across is phanopoeia. This is similar to onomatopoeia, but instead of bringing sound to the page in a specific moment the way you would with onomatopoeic words, phanopoeia brings sound to the overall sensation of the poem as a whole. This is usually done by paying attention to creative use of consonance and assonance.

For example, if you’re writing a story about the sea you might favor lots of w words, sh words, and soft vowels like “whooshing,” “rushing,” “wishes,” “soon,” “would,” “shore,” “whirl,” and so on. When read out loud, these sounds give the sensation of soft, gathering waves.

Another example might be if you’re writing about a noisy city, you could use hard consonants like k, d, or t to create a sense of sharp dissonance. By using words like “crack,” “tatter,” “broken,” “back street,” “district,” or “dirty,” you create a segment of writing that’s alive with life. Notice how different they feel when read out loud compared to the softer ocean sounds in the previous example.

In your writing, try combining onomatopoeia (sound at the line level) and phanopoeia (sound at the broader level) to really bring your poem or story to life.

Examples of onomatopoeia from everyday speech

As you can see, onomatopoeia isn’t always about crashing, banging, or barking. Not just limited to comic book-style stories, auditory language shows up in our everyday speech all the time. Human sounds and natural sounds that describe the world around us often become integrated into our language without us even realizing it. Here are some examples of onomatopoeia words from day-to-day language.

-

“The only sounds were the rustling of pages.”

-

“Water splashed up against the wheels.”

-

“I’m going to catch some Zs before class.”

-

“The clock ticked mercilessly on.”

-

“She slammed her keys down on the table.”

-

“The logs crackled in the fireplace.”

-

“He slurped his soup gratefully.”

-

“A car honked at her as she stepped onto the street.”

-

“They called a plumber to fix the drip in the faucet.”

-

“There was a knock at the front door.”

Not only do these onomatopoeia examples all sound like what they’re describing when spoken out loud, they’ve become a fluid part of our daily language. We don’t even notice that the hard K in “knock” sounds like knuckles against wood; we simply recognize it as a distinctive action. In a story, however, these onomatopoeia examples work on a subconscious level to create a more lifelike setting that we can see and hear.

Onomatopoeia examples from literature

Now that we know more about what onomatopoeia is and the potential it has to elevate a story, let’s look at some other examples from literature.

“A Dream Of Coltrane” by Joel Jacob Todd, Jr.

Walking through Greenwich Village in New York

I hear a distant melody.

What is this cacophony of color, line and sound—

These spiraling notes that seem so angry?

A shrieking saxophone, a moaning horn—

What type of music was being played?

Onomatopoeia is one of the cornerstones of poetry, especially in poems related to music. In this jazz-inspired poem, the poet uses “shrieking” and “moaning” to create a vivid image of the scene. The hard k in “shrieking” and the long vowel in “moaning” make the words sound like what the speaker is hearing. They work well with other supporting aspects of language like “cacophony” and “angry” to immerse the reader in the poem.

October, October by Katya Balen

The noise is still there. It rolls between a hiss and a growl. My heart starts to jump and I wish I had my machete or a tiger. There’s a rustling too and it’s not the normal scuffle of leaves or branches twitching in the wind.

This scene uses vibrant onomatopoeia to describe the world for the reader. We have words like “hiss,” “growl,” “rustling,” and “scuffle,” which come together to create a soundscape of the scene. The double s in “hiss” and the gr in “growl” illustrate what the moment sounds like. When the speaker talks about “rustling,” you can imagine the animal sounds of some unseen beast scraping against the undergrowth.

For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

He saw nothing and heard nothing but he could feel his heart pounding and then he heard the clack on stone and the leaping, dropping clicks of a small rock falling.

A man famous for embracing simplicity in his narratives, Hemingway uses click-clack to illustrate the sharpness of tiny sounds against the silence. The key takeaway in this onomatopoeia example is in the specificity; “click” and “clack” are almost exactly the same word and refer to very similar sounds, and yet each one is exactly right for what Hemingway is trying to communicate. If you were to reverse the two words, the meaning wouldn’t be as powerful.

The more specific you can make your onomatopoeic word choices, the more vivid and immersive your scene will be.

How to use onomatopoeia effectively in your story

Now that you’ve seen how other writers use onomatopoeia in their work, let’s wrap up with some tips on using onomatopoeic words in your own writing.

1. Look to everyday language

As we saw when we looked at onomatopoeia words from everyday speech, much of it is already deeply entrenched in our day-to-day vocabulary. Many onomatopoeia examples happen all around us in advertising, your favorite catchy song, and even casual conversation. Onomatopoeia is always at its best when it’s subtle—when it gives the scene another layer of color without the reader knowing it’s happening right before their eyes.

Remember that specificity is key. Try writing down a few similar onomatopoeia words that you could use in your scene—for example, “rustling,” “scuttling,” “rattling,” “scuffling,” etc—and see which of the sound words feels like the perfect fit for that moment. There will almost always be one that seems to naturally slot into place.

2. Use your ear

Onomatopoeia is deeply instinctive. It’s one of the rare times when you can simply make up words without really having to explain yourself, because your readers will understand. James Joyce was a writer who was notorious for making up onomatopoeic words in his novels.

For example, you could say “his boots shlupped through the mud on his way to the front door.” His boots huh? And yet, this word is all the reader needs to imagine the shlup shlup shlup sound of plastic shoes against wet, clingy mud.

In your writing, try to “listen” as you create your story world and look for ways to use vowels and consonants to convey your own sounds onto the page.

3. Imitate sound with rhythm

Sometimes, onomatopoeia comes from the rhythm of a piece rather than one particular word. This is especially true in poetry, but you can find it in prose, too. One famous example that uses this technique is Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Bells,” where he uses the word “Bell” to imitate a bell sound.

The word itself doesn’t sound a lot like a bell in the way some other onomatopoeia words do, but Poe uses a repetitive rhythm to create the sound he needs:

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the throbbing of the bells—

Of the bells, bells, bells—

and so forth. Here Poe uses rhythm to create a sound effect on the page. Each time he uses a repeated word, it sounds like the repeated tolling of a bell. Try experimenting with syllables, rhythm, and sentence structure to imitate the sort of different sounds you want your reader to hear.

A list of some common onomatopoeia words

If you’re still not sure what onomatopoeia is, check out these examples of onomatopoeia:

-

Pop

-

Hoot

-

Bam

-

Bang

-

Bash

-

Beep

-

Belch

-

Blab

-

Blast

-

Boing

-

Boom

-

Burp

-

Buzz

-

Clack

-

Clang

-

Click

-

Clink

-

Clap

-

Clop

-

Thud

-

Thump

-

Creak

-

Crunch

-

Crackle

-

Rattle

-

Shuffle

-

Ding

-

Dong

-

Tick

-

Tock

-

Drip

-

Fizzle

-

Sizzle

-

Flap

-

Flick

-

Flop

-

Flush

-

Gargle

-

Groan

-

Grunt

-

Gulp

-

Gurgle

-

Gush

-

Hiccup

-

Honk

-

Hum

-

Kapow

-

Knock

-

Lurch

-

Mumble

-

Munch

-

Rumble

-

Rustle

-

Natter

-

Ping

-

Plop

-

Plunk

-

Pow

-

Puff

-

Rap

-

Rasp

-

Ring

-

Scrape

-

Slam

-

Slash

-

Slosh

-

Slurp

-

Snap

-

Splash

-

Swish

-

Swoosh

-

Toot

-

Twang

-

Whip

-

Yammer

-

Yap

-

Zap

-

Zing

-

Zip

-

Zoom

-

Squawk

-

Thwack

-

Squish

-

Squeak

-

Squelch

-

Tweet

-

Warble

-

Chime

-

Clunker

-

Crash

-

Crinkle

-

Flip-flop

-

Pitter patter

-

Tap

-

Wail

-

Whistle

A lot of these words sound or look similar on the page, but they bring to mind a very distinctive sound. That’s the power onomatopoeia gives your writing.

Use onomatopoeic words to create a more expressive story

Onomatopoeia is one of those literary devices that has a sore reputation; used with intention and precision, however, words related to sound can help your writing become more expressive and immersive for the reader. Between natural sounds from the world around us, animal noises, and all the different sounds that we hear every day, you have a whole auditory palette with which to bring your story world to life.