This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

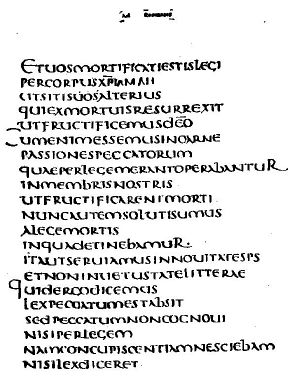

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

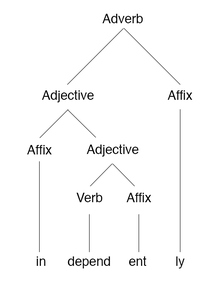

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Since

the word is such a fundamental unit in both language and thought, let

us not try an exhaustive definition and concentrate instead on those

properties of words which are of greatest importance for linguistics:

-

A

word is a unity of meaning and form. -

A

word is composed of one or more morphemes which are the smallest

meaningful units. -

The

meaning of a word is a whole and not a sum of meanings of its

component morphemes. -

The

morphemes, and therefore the word, are made up of one or more spoken

sounds (or their graphic representations). -

A

word is made graphically and phonetically separate from other words

by spacing, intonation, and stress. Thus,

a number of formal

criteria

can be suggested. In writing, for instance, a word is something

which has a space on either side. But in speech, there is no exact

equivalent of this; we do not pause after every word when we speak.

Then one such criterion in writing is leaving a space and in oral

speech it is a potential pause which often coincides with the spaces

in writing. -

A

word, unlike a morpheme, is a minimum syntactically complete

structure (= a minimum complete utterance). Another

criterion is that words are the smallest units in a language that

can

be used alone as a sentence.

We can say Go.

Here.

Men.

We cannot use the bits of words as sentences, as with un

-,-ize, in-. -

There

are two classes of morphemes – those used to produce new words and

those used for linking words together in a syntactic unity. -

The

freedom of linking words together is limited by syntactic rules

which form a separate field of study. Yet

another criterion for word identification is in terms of minimal

unit of positional mobility

– which is simply a precise way of saying that the word is the

smallest unit which can be moved from one position to another in a

sentence – bits of words cannot be so moved. -

Words

are relatively stable in use, and therefore can be isolated and

fixed in dictionaries. Words

are the units which have fixed

internal structure.

Technically this characteristic is often referred to as internal

stability. If we want to insert fresh information into a sentence,

then it is between the words that this information goes and not

within them. Words are not interruptable.

Another

technique may be helpful in identifying separate words in a language,

namely the use of formulas of speech. One may say This

is a

… followed by various free forms such as pen,

book, house,

etc.

So

the word differs from the morpheme, on the one hand, and the

word-combination, on the other, and can be singled out in the flow of

speech as an independent unit.

We

can distinguish the following criteria of the word:

– the

phonetic criterion (pause, accent, intonation),

– the

acoustic identity of the word,

– the

criteria of separability, replaceability and displaceability,

– the

semantic criterion,

– the

criterion of isolatedness and reproducibility.

One

more problem that is connected with the problem of the definition of

the word is the existence of homonymous forms. In this case it is

difficult to say whether it is one word or different words. As an

example let’s take a sentence «Of

all the saws I ever saw I never saw a saw as that saw saws».

Here

we deal with two different words: the noun saw

and the verb saw,

because they have two different paradigms. Paradigm is the system of

the grammatical forms of a word. It means that though they are

identical in sound and spelling, they are different in meaning,

distribution (usage) and origin.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning. Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition.

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own. Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation. In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock,» «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

Definitions and meanings

A word can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[2] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock,» «god,» «write,» «with,» «the,» and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks,» «ungodliness,» «typewriter,» and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s,» «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness,» «type»+»writ»+»er,» and «can»+»not»).

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[2] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[3]. Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context, but these do not converge on a single definition.[4] Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on a phonological, a grammatical or an orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[5] It is possible, however, to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description. These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers. On the orthographic level it is a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print. On the basis of morphology it is the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms. Within semantics it is the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon.Syntactically, it is the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[3]

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word.» However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[5] Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric perspective of European scholars, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the same patterns. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[5] Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[3] The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[5]

In most languages, stress may serve as a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[5]

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[5]

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[4]

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon. This is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[4]

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[5]

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9] This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10] Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13] The word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way). Each of these features defines one aspect of the word.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[14]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[15] Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Usage and meaning

When studying the way in which words and signs are used, it is often the case that words have different meanings, depending on the social context of use. An important example of this is the process called deixis, which describes the way in which certain words refer to entities through their relation between a specific point in time and space when the word is uttered. Such words are, for example, the word, «I» (which designates the person speaking), «now» (which designates the moment of speaking), and «here» (which designates the position of speaking). Signs also change their meanings over time, as the conventions governing their usage gradually change. The study of how the meaning of linguistic expressions changes depending on context is called pragmatics. Deixis is an important part of the way that we use language to point out entities in the world.[16] Pragmatics is concerned with the ways in which language use is patterned and how these patterns contribute to meaning. For example, in all languages, linguistic expressions can be used not just to transmit information, but to perform actions. Certain actions are made only through language, but nonetheless have tangible effects. The act of «naming» creates a new name for some entity, or the act of «pronouncing someone man and wife,» which creates a social contract of marriage. These types of acts are called speech acts, although they can also be carried out through writing or hand signing.[16]

The form of linguistic expression often does not correspond to the meaning that it actually has in a social context. For example, if at a dinner table a person asks, «Can you reach the salt?», that is, in fact, not a question about the length of the arms of the one being addressed, but a request to pass the salt across the table. This meaning is implied by the context in which it is spoken; these kinds of effects of meaning are called conversational implicatures. These social rules for which ways of using language are considered appropriate in certain situations and how utterances are to be understood in relation to their context vary between communities, and learning them is a large part of acquiring communicative competence in a language.[16]

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[2]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[17] the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East Asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese and Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[15]

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century B.C.E., with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words focusing on their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas,» though they are chosen «not by any natural connection that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea.»[18] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[19]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[20]

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[21][4] On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[4]

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century B.C.E., distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language. Since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[4]

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, since they do not mean what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[22]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [23] This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, in which the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[5] The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.

Notes

- ↑ E. K. Brown and J. E. Miller, The Cambridge Dictionary of Linguistics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0521766753), 473.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Martin Haspelmath, «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax,» Folia Linguistica 45(1) (2011). Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hadumod Bussman, Gregory Trauth, and Kerstin Kazzazi, Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics (London, UK: Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0415022258), 670-671, 768, 1285.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Keith Brown, Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: Volumes 1-14, 2nd. ed. (Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier Publications, 2005, ISBN 978-0080442990), 13:618, 629, 631.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Robert M. W. Dixon and A. Y. Aikhenvald, Word: A cross-linguistic typology (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0511061498), 1-6, 14-20, 269.

- ↑ Zellig S. Harris, «From morpheme to utterance,» Language 22(3) (1946): 161–183.

- ↑ John R. Taylor, The Oxford Handbook of the Word (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0191756696).

- ↑ Martin S. Chodorow, Roy J. Byrd, and George E. Heidorn, «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary,» Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (1985): 299–304. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ↑ Francis Katamba, English Words: Structure, history, usage, 2nd. ed. (London, UK: Routledge, 2005, ISBN 041529892X), 11.

- ↑ Michael Fleming, Frank Hardman, David Stevens, and John Williamson, Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (London, UK: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-1134568512), 77. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Anna Wierzbicka, Semantics: Primes and universals (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0198700024).

- ↑ Cliff Goddard and Anna Wierzbicka, «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages,» in Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Pub. Co., 2002, ISBN 1588112640).

- ↑ David Adger, Core Syntax: A minimalist approach (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0199243700), 36-37.

- ↑ Note that the convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ralph W. Fasold and Jeff Connor-Linton, An Introduction to Language and Linguistics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0521847681), 56, 73.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Stephen C. Levinson, Pragmatics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0521222358).

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, English Word-formation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 0521241677), 9.

- ↑ John Locke, «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words,» in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, volume III (London, UK: Thomas Basset, 1690). Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Anar Biletzki and Anat Matar, «Ludwig Wittgenstein,» in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Winter 2021). Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Adrian Akmajian, Linguistics: An introduction to language and communication, 6th ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0262013758), 21-24.

- ↑ David Beck, «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed,» Flexible Word Classes ed. Jan Rijkhoff and Eva van Lier (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0199668441), 185-220. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Clinton B. De Soto, Margaret M. Hamilton, and Ralph B. Taylor, «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory,» Social Cognition 3(4) (December 1985): 369–382. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ R. H. Robins, A Short History of Linguistics, 4th. ed. (London, UK: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0582249945), 70.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adger, David. Core Syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0199243700

- Akmajian, Adrian. Linguistics: An introduction to language and communication, 6th ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0262013758

- Bauer, Laurie. English Word-formation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0521241677

- Beck, David. «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed,» Flexible Word Classes edited by Jan Rijkhoff and Eva van Lier. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0199668441

- Biletzki, Anar, and Anat Matar. «Ludwig Wittgenstein,» The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Winter 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Brown, E. K., and Anne Anderson. The Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, 2nd. ed. Amsterdam, N.L.: Elsevier, 2006. ISBN 978-0080442990

- Brown, E. K. and J. E. Miller. The Cambridge Dictionary of Linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0521766753

- Brown, Keith. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: Volumes 1-14, 2nd. ed. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier Publications, 2005. ISBN 978-0080442990

- Bussman, Hadumod, Gregory Trauth, and Kerstin Kazzazi. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. London, UK: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0415022258

- Chodorow, Martin S., Roy J. Byrd and George E. Heidorn. «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary,» Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (1985): 299–304. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- De Soto, Clinton B., Margaret M. Hamilton, and Ralph B. Taylor. «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory,» Social Cognition 3(4) (December 1985): 369–382. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Dixon Robert M. W., and A. Y. Aikhenvald. Word: A cross-linguistic typology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0511061498

- Fasold, Ralph W., and Jeff Connor-Linton. An Introduction to Language and Linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0521847681

- Fleming, Michael, Frank Hardman, David Stevens, and John Williamson. Meeting the Standards in Secondary English. London, UK: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-1134568512

- Goddard, Cliff, and Anna Wierzbicka. «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages,» in Meaning and Universal Grammar. Volume II: Theory and empirical findings. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 1588112640

- Harris, Zellig S. «From morpheme to utterance,» Language 22(3) (1946): 161–183.

- Haspelmath, Martin. «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax,» Folia Linguistica 45(1) (2011). Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Katamba, Francis. English Words: Structure, history, usage, 2nd. ed. London, UK: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 041529892X

- Levinson, Stephen C. Pragmatics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0521222358

- Locke, John. «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words,» in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. HardPress Publishing, 2019 (original 1690). ISBN 978-0461142044

- Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics, 4th. ed. London, UK: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0582249945

- Taylor, John R. The Oxford Handbook of the Word. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0191756696

- Wierzbicka, Anna. Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0198700024

Further Reading

- Barton, David. Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1994. ISBN 0631190899

- Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521401798

- Plag, Ingo. Word-formation in English. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0511078439

- Simpson, J. A., and E. S. C. Weiner. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd. ed. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1989. ISBN 0198611862

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Word history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Word»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

According to traditional grammar, a word is defined as, “the basic unit of language”. The word is usually a speech sound or mixture of sounds which is represented in speaking and writing.

Few examples of words are fan, cat, building, scooter, kite, gun, jug, pen, dog, chair, tree, football, sky, etc.

You can also define it as, “a letter or group/set of letters which has some meaning”. So, therefore the words are classified according to their meaning and action.

It works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in the language.

The group of words makes a sentence. These sentences contain different types of functions (of the words) in it.

The structure (formation) of words can be studied with Morphology which is usually a branch (part) of linguistics.

The meaning of words can be studied with Lexical semantics which is also a branch (part) of linguistics.

Also Read: What is a Sentence in English Grammar? | Best Guide for 2021

The word can be used in many ways. Few of them are mentioned below.

- Noun (rabbit, ring, pencil, US, etc)

- Pronoun (he, she, it, we, they, etc)

- Adjective (big, small, fast, slow, etc)

- Verb (jumping, singing, dancing, etc)

- Adverb (slowly, fastly, smoothly, etc)

- Preposition (in, on, into, for, under, etc)

- Conjunction (and, or, but, etc)

- Subject (in the sentences)

- Verb and many more!

Now, let us understand the basic rules of the words.

Rules/Conditions for word

There are some set of rules (criteria) in the English Language which describes the basic necessity of becoming a proper word.

Rule 1: Every word should have some potential pause in between the speech and space should be given in between while writing.

For example, consider the two words like “football” and “match” which are two different words. So, if you want to use them in a sentence, you need to give a pause in between the words for pronouncing.

It cannot be like “Iwanttowatchafootballmatch” which is very difficult to read (without spaces).

But, if you give pause between the words while reading like, “I”, “want”, “to”, “watch”, “a”, “football”, “match”.

Example Sentence: I want to watch a football match.

We can observe that the above sentence can be read more conveniently and it is the only correct way to read, speak and write.

- Incorrect: Iwanttowatchafootballmatch.

- Correct: I want to watch a football match.

So, always remember that pauses and spaces should be there in between the words.

Rule 2: Every word in English grammar must contain at least one root word.

The root word is a basic word which has meaning in it. But if we further break down the words, then it can’t be a word anymore and it also doesn’t have any meaning in it.

So, let us consider the above example which is “football”. If we break this word further, (such as “foot” + “ball”), we can observe that it has some meaning (even after breaking down).

Now if we further break down the above two words (“foot” + “ball”) like “fo” + “ot” and “ba” + “ll”, then we can observe that the words which are divided have no meaning to it.

So, always you need to remember that the word should have atleast one root word.

Rule 3: Every word you want to use should have some meaning.

Yes, you heard it right!

We know that there are many words in the English Language. If you have any doubt or don’t know the meaning of it, then you can check in the dictionary.

But there are also words which are not defined in the English Language. Many words don’t have any meaning.

So, you need to use only the words which have some meaning in it.

For example, consider the words “Nuculer” and “lakkanah” are not defined in English Language and doesn’t have any meaning.

Always remember that not every word in the language have some meaning to it.

Also Read: 12 Rules of Grammar | (Grammar Basic Rules with examples)

More examples of Word

| Words List | Words List |

| apple | ice |

| aeroplane | jam |

| bat | king |

| biscuit | life |

| cap | mango |

| doll | nest |

| eagle | orange |

| fish | pride |

| grapes | raincoat |

| happy | sad |

Quiz Time! (Test your knowledge here)

#1. A word can be ____________.

all of the above

all of the above

a noun

a noun

an adjective

an adjective

a verb

a verb

Answer: A word can be a noun, verb, adjective, preposition, etc.

#2. A root word is a word that _____________.

none

none

can be divided further

can be divided further

cannot be divided further

cannot be divided further

both

both

Answer: A root word is a word that cannot be divided further.

#3. A group of words can make a ___________.

none

none

sentence

sentence

letters

letters

words

words

Answer: A group of words can make a sentence.

#4. Morphology is a branch of ___________.

none

none

Linguistics

Linguistics

Phonology

Phonology

Semantics

Semantics

Answer: Morphology is a branch of Linguistics.

#5. The meaning of words can be studied with ___________.

none

none

both

both

Morphology

Morphology

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

Answer: The meaning of the words can be studied with Lexical semantics.

#6. The word is the largest unit in the language. Is it true or false?

#7. Is cat a word? State true or false.

Answer: “Cat” is a word.

#8. A word is a _____________.

group of paragraphs

group of paragraphs

group of letters

group of letters

group of sentences

group of sentences

All of the above

All of the above

Answer: A word is a group of letters which delivers a message or an idea.

#9. A word is usually a speech sound or mixture of it. Is it true or false?

#10. The structure of words can be studied with ___________.

Morphology

Morphology

both

both

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

none

none

Answer: The structure of words can be studied with Morphology.

Results

—

Hurray….. You have passed this test! 🙂

Congratulations on completing the quiz. We are happy that you have understood this topic very well.

If you want to try again, you can start this quiz by refreshing this page.

Otherwise, you can visit the next topic 🙂

Oh, sorry about that. You didn’t pass this test! 🙁

Please read the topic carefully and try again.

Summary: (What is a word?)

- Generally, the word is the basic and smallest unit in the language.

- It is categorised based on its meaning.

- Morphology is the study of Words structure (formation) and Lexical semantics is the study of meanings of the words. These both belong to a branch of Linguistics.

- A word should have at least one root and meaning to it.

Also Read: What is Grammar? | (Grammar definition, types & examples) | Best Guide 2021

If you are interested to learn more, then you can refer wikipedia from here.

I hope that you understood the topic “What is a word?”. If you still have any doubts, then comment down below and we will respond as soon as possible. Thank You.

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language.A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Contents

- 1 What is word and its example?

- 2 What is word and its types?

- 3 What is word linguistics?

- 4 What is the meaning of word?

- 5 What are words called?

- 6 What is word in language?

- 7 What is a word class in grammar?

- 8 Why do we define words?

- 9 Why do we say word?

- 10 What is morpheme and word?

- 11 What is word Slideshare?

- 12 Is word a noun or verb?

- 13 What are the parts of a word?

- 14 What is word Wikipedia?

- 15 What type of word is there?

- 16 What is word boundaries?

- 17 What is called sentence?

- 18 Is your name a word?

- 19 What are the 4 main word classes?

- 20 What is word class in syntax?

What is word and its example?

The definition of a word is a letter or group of letters that has meaning when spoken or written. An example of a word is dog.An example of words are the seventeen sets of letters that are written to form this sentence.

What is word and its types?

There are eight types of words that are often referred to as ‘word classes’ or ‘parts of speech’ and are commonly distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions.These are the different types of words in the English language.

What is word linguistics?

In linguistics, a word of a spoken language can be defined as the smallest sequence of phonemes that can be uttered in isolation with objective or practical meaning.In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a “word” may be learned as part of learning the writing system.

What is the meaning of word?

1 : a sound or combination of sounds that has meaning and is spoken by a human being. 2 : a written or printed letter or letters standing for a spoken word. 3 : a brief remark or conversation I’d like a word with you.

What are words called?

All words belong to categories called word classes (or parts of speech) according to the part they play in a sentence. The main word classes in English are listed below. Noun. Verb. Adjective.

What is word in language?

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or a combination of morphemes. The branch of linguistics that studies word structures is called morphology.

A word class is a group of words that have the same basic behaviour, for example nouns, adjectives, or verbs.

Why do we define words?

The definition of definition is “a statement expressing the essential nature of something.” At least that’s one way Webster defines the word.Because definitions enable us to have a common understanding of a word or subject; they allow us to all be on the same page when discussing or reading about an issue.

Why do we say word?

‘Word’ in slang is a word one would use to indicate acknowledgement, approval, recognition or affirmation, of something somebody else just said.

What is morpheme and word?

Word vs Morpheme

A morpheme is usually considered as the smallest element of a word or else a grammar element, whereas a word is a complete meaningful element of language.

What is word Slideshare?

•“A word’ is a free morpheme or a combination of morphemes that together form a basic segment of speech” .

Is word a noun or verb?

word used as a noun:

A distinct unit of language (sounds in speech or written letters) with a particular meaning, composed of one or more morphemes, and also of one or more phonemes that determine its sound pattern. A distinct unit of language which is approved by some authority.

What are the parts of a word?

The parts of a word are called morphemes. These include suffixes, prefixes and root words. Take the word ‘microbiology,’ for example.

What is word Wikipedia?

A word is something spoken by the mouth, that can be pronounced. In alphabetic writing, it is a collection of letters used together to communicate a meaning. These can also usually be pronounced.Some words have different pronunciation, for example, ‘wind’ (the noun) and ‘wind’ (the verb) are pronounced differently.

What type of word is there?

The word “there” have multiple functions. In verbal and written English, the word can be used as an adverb, a pronoun, a noun, an interjection, or an adjective. This word is classified as an adverb if it is used to modify a verb in the sentence.

What is word boundaries?

A word boundary is a zero-width test between two characters. To pass the test, there must be a word character on one side, and a non-word character on the other side. It does not matter which side each character appears on, but there must be one of each.

What is called sentence?

A sentence is a set of words that are put together to mean something. A sentence is the basic unit of language which expresses a complete thought. It does this by following the grammatical basic rules of syntax.A complete sentence has at least a subject and a main verb to state (declare) a complete thought.

Is your name a word?

Yes, names are words. Specifically, they are proper nouns: they refer to specific people, places, or things. “John” is a proper noun; “ground” is a common noun. But both are words.

What are the 4 main word classes?

There are four major word classes: verb, noun, adjective, adverb.

What is word class in syntax?

In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution.It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).