This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

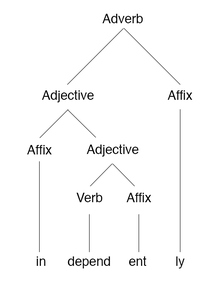

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

According to traditional grammar, a word is defined as, “the basic unit of language”. The word is usually a speech sound or mixture of sounds which is represented in speaking and writing.

Few examples of words are fan, cat, building, scooter, kite, gun, jug, pen, dog, chair, tree, football, sky, etc.

You can also define it as, “a letter or group/set of letters which has some meaning”. So, therefore the words are classified according to their meaning and action.

It works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in the language.

The group of words makes a sentence. These sentences contain different types of functions (of the words) in it.

The structure (formation) of words can be studied with Morphology which is usually a branch (part) of linguistics.

The meaning of words can be studied with Lexical semantics which is also a branch (part) of linguistics.

Also Read: What is a Sentence in English Grammar? | Best Guide for 2021

The word can be used in many ways. Few of them are mentioned below.

- Noun (rabbit, ring, pencil, US, etc)

- Pronoun (he, she, it, we, they, etc)

- Adjective (big, small, fast, slow, etc)

- Verb (jumping, singing, dancing, etc)

- Adverb (slowly, fastly, smoothly, etc)

- Preposition (in, on, into, for, under, etc)

- Conjunction (and, or, but, etc)

- Subject (in the sentences)

- Verb and many more!

Now, let us understand the basic rules of the words.

Rules/Conditions for word

There are some set of rules (criteria) in the English Language which describes the basic necessity of becoming a proper word.

Rule 1: Every word should have some potential pause in between the speech and space should be given in between while writing.

For example, consider the two words like “football” and “match” which are two different words. So, if you want to use them in a sentence, you need to give a pause in between the words for pronouncing.

It cannot be like “Iwanttowatchafootballmatch” which is very difficult to read (without spaces).

But, if you give pause between the words while reading like, “I”, “want”, “to”, “watch”, “a”, “football”, “match”.

Example Sentence: I want to watch a football match.

We can observe that the above sentence can be read more conveniently and it is the only correct way to read, speak and write.

- Incorrect: Iwanttowatchafootballmatch.

- Correct: I want to watch a football match.

So, always remember that pauses and spaces should be there in between the words.

Rule 2: Every word in English grammar must contain at least one root word.

The root word is a basic word which has meaning in it. But if we further break down the words, then it can’t be a word anymore and it also doesn’t have any meaning in it.

So, let us consider the above example which is “football”. If we break this word further, (such as “foot” + “ball”), we can observe that it has some meaning (even after breaking down).

Now if we further break down the above two words (“foot” + “ball”) like “fo” + “ot” and “ba” + “ll”, then we can observe that the words which are divided have no meaning to it.

So, always you need to remember that the word should have atleast one root word.

Rule 3: Every word you want to use should have some meaning.

Yes, you heard it right!

We know that there are many words in the English Language. If you have any doubt or don’t know the meaning of it, then you can check in the dictionary.

But there are also words which are not defined in the English Language. Many words don’t have any meaning.

So, you need to use only the words which have some meaning in it.

For example, consider the words “Nuculer” and “lakkanah” are not defined in English Language and doesn’t have any meaning.

Always remember that not every word in the language have some meaning to it.

Also Read: 12 Rules of Grammar | (Grammar Basic Rules with examples)

More examples of Word

| Words List | Words List |

| apple | ice |

| aeroplane | jam |

| bat | king |

| biscuit | life |

| cap | mango |

| doll | nest |

| eagle | orange |

| fish | pride |

| grapes | raincoat |

| happy | sad |

Quiz Time! (Test your knowledge here)

#1. A word can be ____________.

all of the above

all of the above

a noun

a noun

an adjective

an adjective

a verb

a verb

Answer: A word can be a noun, verb, adjective, preposition, etc.

#2. A root word is a word that _____________.

none

none

can be divided further

can be divided further

cannot be divided further

cannot be divided further

both

both

Answer: A root word is a word that cannot be divided further.

#3. A group of words can make a ___________.

none

none

sentence

sentence

letters

letters

words

words

Answer: A group of words can make a sentence.

#4. Morphology is a branch of ___________.

none

none

Linguistics

Linguistics

Phonology

Phonology

Semantics

Semantics

Answer: Morphology is a branch of Linguistics.

#5. The meaning of words can be studied with ___________.

none

none

both

both

Morphology

Morphology

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

Answer: The meaning of the words can be studied with Lexical semantics.

#6. The word is the largest unit in the language. Is it true or false?

#7. Is cat a word? State true or false.

Answer: “Cat” is a word.

#8. A word is a _____________.

group of paragraphs

group of paragraphs

group of letters

group of letters

group of sentences

group of sentences

All of the above

All of the above

Answer: A word is a group of letters which delivers a message or an idea.

#9. A word is usually a speech sound or mixture of it. Is it true or false?

#10. The structure of words can be studied with ___________.

Morphology

Morphology

both

both

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

none

none

Answer: The structure of words can be studied with Morphology.

Results

—

Hurray….. You have passed this test! 🙂

Congratulations on completing the quiz. We are happy that you have understood this topic very well.

If you want to try again, you can start this quiz by refreshing this page.

Otherwise, you can visit the next topic 🙂

Oh, sorry about that. You didn’t pass this test! 🙁

Please read the topic carefully and try again.

Summary: (What is a word?)

- Generally, the word is the basic and smallest unit in the language.

- It is categorised based on its meaning.

- Morphology is the study of Words structure (formation) and Lexical semantics is the study of meanings of the words. These both belong to a branch of Linguistics.

- A word should have at least one root and meaning to it.

Also Read: What is Grammar? | (Grammar definition, types & examples) | Best Guide 2021

If you are interested to learn more, then you can refer wikipedia from here.

I hope that you understood the topic “What is a word?”. If you still have any doubts, then comment down below and we will respond as soon as possible. Thank You.

Word is a unit of language that serves as a principal carrier of meaning, consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation. One may define a word as the blocks from which sentences are made. Words consist of one or more morphemes that can be of independent use or consist of two or three such units combined under some connection. Words are usually divided into writing by spaces and in many languages. They are differentiated phonologically, as by accent.

Idioms beginning with Words:

-

word for word

-

word of honour

-

word of mouth

-

words fail me

-

words of one syllable,

-

words stick in one’s throat

-

words to that effect

-

word to the wise

Types of a Word

Word is a speech sound or sequence of speech sounds that typically symbolize and express a message without being divisible into smaller units that can be used separately.

Word is the whole range of linguistic forms generated by combining a single basis with different inflectional elements without altering the part of speech elements.

-

Any part of a written or printed expression that normally occurs between spaces or between a space and a punctuation mark.

-

The act of speaking or talking verbally. A short comment or conversation

-

I just want to have a chat with you.

-

A number of bytes that are processed as a unit and convey a quantity of contact and computer work information

-

To form phrases, we combine words. Typically, a term serves the same purpose as a word from some other class of terms.

What makes a Word Real Word?

In English, the word has a broad variety of meanings and uses. Yet one of the pieces of word-related knowledge most commonly searched for is not something that can be included in its meaning. Instead, what makes a word a real word is some variant of the question?

Vocabulary is one of English’s most prolific fields of change and variation; new terms are constantly being invented to name or characterize new technologies or developments or to better classify aspects of our rapidly changing culture. Time, resources and personnel constraints would make it impossible for any dictionary to capture a completely comprehensive account of all the terms in the language, no matter how big. Most general English dictionaries are intended to contain only terms that fulfil certain usage requirements in large areas and over long periods (for more information about how words are selected for entry in the dictionary).

Classification of Words

Words are grouped in English into parts of speech. The functional adjective and functional adverb are functional derivations.

Noun

A noun is an identifying word:

Eg: An individual (man, female, engineer, friend)

Verb

What a person or thing does or what happens is represented by a verb.

Eg: A case, An action

Adjective

An adjective is a term that identifies a noun, offering additional details about it.

Eg: A thrilling adventure

Adverb

An adverb is a word used to give a verb, adjective or other adverb details. They can make stronger or weaker the meaning of a noun, adjective, or other adverbs, and sometimes appear between the subject and its verb.

Eg: She almost lost everything.

Pronoun

In place of a noun that is already recognized or has already been mentioned, pronouns are used. To stop repeating the noun, this is always done.

Eg: Since she was tired, Laura left early.

Preposition

A preposition is a concept like after, in to, on, and with. Prepositions are normally used in front of nouns or pronouns and illustrate the connection in a sentence between the noun or pronoun and other words.

Conjunction

A conjunction is a term such as and because, but for, if or, and when A conjunction (also called a connective). Conjunctions are used to connect words, clauses, and sentences.

Determiner

A determiner is a phrase that introduces a noun, such as a/an, the any, this, others, or many (as in a dog, the dog, this dog, those dogs, each dog, many dogs).

Exclamation

A word or expression that expresses strong emotions, such as surprise, pleasure, or rage, is an exclamation (also called an interjection). Exclamations sometimes stand on their own.

A word is a unit of language that carries meaning and consists of one or more morphemes which are linked more or less tightly together, and has a phonetic value. Typically a word will consist of a root or stem and zero or more affixes. Words can be combined to create phrases, clauses, and sentences. A word consisting of two or more stems joined together form a compound. A word combined with another word or part of a word form a portmanteau.

Etymology

English ‘ is directly from Old English «word», and has cognates in all branches of Germanic (Old High German «wort», Old Norse «orð», Gothic «waurd»), deriving from Proto-Germanic «*wurđa», continuing a virtual PIE «PIE|*wr̥dhom«. Cognates outside Germanic include Baltic (Old Prussian «wīrds» «word», and with different ablaut Lithuanian » var̃das» «name», Latvian «vàrds» «word, name») and Latin ‘. The PIE stem «PIE|*werdh-» is also found in Greek ερθει (φθεγγεται «speaks, utters» Hes. ). The PIE root is «PIE|*ŭer-, ŭrē-» «say, speak» (also found in Greek ειρω, ρητωρ). [Jacob Grimm, «Deutsches Wörterbuch»]

The original meaning of «word» is «utterance, speech, verbal expression». [OED, sub I. 1-11.] Until Early Modern English, it could more specifically refer to a name or title. [OED, sub II. 12 b. (a)]

The technical meaning of «an element of speech» first arises in discussion of grammar (particularly Latin grammar), as in the prologue to Wyclif’s Bible (ca. 1400)::»This word «autem», either «vero», mai stonde for «forsothe», either for «but».» [OED meaning II. 12 a.]

Definitions

Depending on the language, words can be difficult to identify or delimit. Dictionaries take upon themselves the task of categorizing a language’s lexicon into lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the authors.

Word boundaries

In spoken language, the distinction of individual words is usually given by rhythm or accent, but short words are often run together. See clitic for phonologically dependent words. Spoken French has some of the features of a polysynthetic language: «il y est allé» («He went there») is pronounced /IPA|i.ljɛ.ta.le/. As the majority of the world’s languages are not written, the scientific determination of word boundaries becomes important.

There are five ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:;Potential pause:A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words.;Indivisibility:A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, «I have lived in this village for ten years» might become «I and my family have lived in this little village for about ten or so years». These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes; in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an,» the noun «ankommen» is separated.;Minimal free forms:This concept was proposed by Leonard Bloomfield. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves. This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms, as they make no sense by themselves (for example, «the» and «of»).;Phonetic boundaries:Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish): the vowels within a given word share the same «quality», so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. However, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.;Semantic units:Much like the above mentioned minimal free forms, this method breaks down a sentence into its smallest semantic units. However, language often contains words that have little semantic value (and often play a more grammatical role), or semantic units that are compound words.

;A further criterion. Pragmatics. As Plag suggests, the idea of a lexical item being considered a word should also adjust to pragmatic criteria. The word «hello, for example, does not exist outside of the realm of greetings being difficult to assign a meaning out of it. This is a little more complex if we consider «how do you do?»: is it a word, a phrase, or an idiom? In practice, linguists apply a mixture of all these methods to determine the word boundaries of any given sentence. Even with the careful application of these methods, the exact definition of a word is often still very elusive.

There are some words that seem very general but may truly have a technical definition, such as the word «soon,» usually meaning within a week.

Orthography

In languages with a literary tradition, there is interrelation between orthography and the question of what is considered a single word.

Word separators (typically space marks) are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts,but these are (excepting isolated precedents) a modern development (see also history of writing).

In English orthography, words may contain spaces if they are compounds or proper nouns such as «ice cream» or «air raid shelter».

Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes, not words. Conversely, synthetic languages often combine many lexical morphemes into single words, making it difficult to boil them down to the traditional sense of words found more easily in analytic languages; this is especially difficult for polysynthetic languages such as Inuktitut and Ubykh, where entire sentences may consist of single such words.

Logographic scripts use single signs (characters) to express a word. Most «de facto» existing scripts are however partly logographic, and combine logographic with phonetic signs. The most widespreadlogographic script in modern use is the Chinese script. While the Chinese script has some true logographs, the largest class of characters used in modern Chinese (some 90%) are so-called pictophonetic compounds ( _zh. 形声字, _pn. Xíngshēngzì). Characters of this sort are composed of two parts: a pictograph, which suggests the general meaning of the character, and a phonetic part, which is derived from a character pronounced in the same way as the word the new character represents. In this sense, the character for most Chinese words consists of a determiner and a syllabogram, similar to the approach used by cuneiform script and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

There is a tendency informed by orthography to identify a single Chinese character as corresponding to a single word in the Chinese language, parallel to the tendency to identify the letters between two space marks as a single word in the English language. In both cases, this leads to the identification of compound members as individual words, while e.g. in German orthography, compound members are not separated by space marks and the tendency is thus to identify the entire compound as a single word. Compare e.g. English «capital city» with German «Hauptstadt» and Chinese 首都 (lit. ): all three are equivalent compounds, in the English case consisting of «two words» separated by a space mark, in the German case written as a «single word» without space mark, and in the Chinese case consisting of two logographic characters.

Morphology

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, «love») may have a number of different forms (for example, «loves», «loving», and «loved»). However, these are not usually considered to be different words, but different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are

*the root

*optional suffixes

*a desinence.Thus, the Proto-Indo-European «PIE|*wr̥dhom» would be analysed as consisting of

#»PIE|*wr̥-«, the zero grade of the root «PIE|*wer-»

#a root-extension «PIE|*-dh-» (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root «PIE|*wr̥dh-«

#The thematic suffix «PIE|*-o-«

#the neuter gender nominative or accusative singular desinence «PIE|*-m«.

Classes

Grammar classifies a language’s lexicon into several groups of words. The basic bipartite division possible for virtually every natural language is that of nouns vs. verbs.

The classification into such classes is in the tradition of Dionysius Thrax, who distinguished eight categories: noun, verb, adjective, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction and interjection.

In Indian grammatical tradition, Panini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of desinences taken by the word.

References

*Bauer, L. (1983) English Word Formation. Cambridge. CUP.

*Brown, Keith R. (Ed.) (2005) Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Elsevier. 14 vols.

*Crystal, D. (1995) The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

*Plag, Ingo.(2003) Word formation in English. CUP

ee also

*Grammar

*Utterance

*Morphology

*Lexeme

*Lexicon

*Lexis (linguistics)

*Lexical item

External links

* [http://www.sussex.ac.uk/linguistics/documents/essay_-_what_is_a_word.pdf What Is a Word?] — a working paper by Larry Trask, Department of Linguistics and English Language, University of Sussex.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

What is a word? This question is one of the most deceptively simple ones I know. Everyone will say they know the answer, or at least say they know one when they see one, but even native speakers of a language can and do disagree. The dictionary isn’t much help since many dictionaries have multi-sentence, ad hoc definitions which basically boil down to «a word is a unit of language that means something, sort of.»

Let’s jump ahead and assume we know what a word is, or that we can get native speakers to identify most words most of the time. Furthermore, let’s say that our goal is to get a computer to understand a given language. Since humans learn languages initially by learning words and basic grammar it seems like a good choice to try and get computers to recognize words. So, our goal: given a string of English letters insert spaces between the words.

What is a word?

To show that the above exercise isn’t totally contrived let’s look at some of the subtleties in the idea of the word. This is only for people interested in the «linguistics» part of «computaitonal linguistics,» but if you want to read it then click here.

Assumptions

Obviously we can’t integrate all of the subtleties above as that would be tantamount to writing a computer program which actually processed text in the same way humans do. Rather, we will work under the following assumptions: first, we already have a database (called the «lexicon») of words; second, this database is complete. The first assumption isn’t totally off-the-wall since it’s a general working assumption among linguists that humans have just such a database. The second, however, is much harder to swallow since the lexicon is typically understood to contain root morphemes plus general information about the morphology, phonology, phonotactics, etc. of the language.

If I said «koop» were a verb, you’d know right away that «kooped,» «koops,» «kooper,» etc. were all also valid words. Likewise, even though «cromulent» is not actually an English word an English speaker knows that it could be (and that, furthermore, it would probably be an adjective), but that «plkdjfhg» could never be an English word. Our database, however, is very dumb and very uncompressed: every permutation of every word should be present, otherwise that permutation won’t be counted as a word. We’re only making this assumption to simplify the problem. I may be a pretty good programmer, but I’m not good enough to write a computer program which automatically learns a language’s syntax, morphology, and phonology.

Enough chit chat, let’s get to the code.

The Algorithm

The algorithm I’m going to use is a simple probabalistic dynamic programming algorithm. Let’s say we have a string like «therentisdue» and want to parse it as «the-rent-is-due.» Assuming our training data is representative of the language as a whole (a big assumption, for sure) then we know the probability of each word is #occurances of the word in the data over the total number of words in the data. The idea is that the best parse of a string, given our training data, is the parse which has the highest probability of occuring.

For the CS students out there this should scream «dynamic programming.» For everyone else, I’ll explain. The most obvious way to find the parse with the highest probability is to find every possible parse and then find that parse which has the highest probability. Implementing the algorithm this way is intractable since there are 2n-1 parses (why?). Instead we’ll do the following. The pseudo code:

BestParse[0] := "" FOR i in [1..length of StringToParse] DO FOR j in [0..i) DO parse := BestParse[j] + StringToParse[j,i] IF COST(parse) < COST(BestParse[i]) THEN BestParse[i] = parse ENDIF ENDFOR ENDFOR DEFINE COST(parse) return -LOG2(PROBABILITY(parse)) END DEFINE PROBABILITY(parse) return product of the frequencies of each word in parse END

Let the input string be s. At each point i, that is, for the initial i-length substring of s, determine what the best parse up to i is. Now, let’s say we know what the best parse at i is for some fixed i. To find the best parse at i+1 we try to insert a break after each initial j substring, for j < i+1. Since we’ve been keeping track of the best parse (and cost) at each such j the whole time, we just see which break insertion is the cheapest.

Here is an illustration, again with «therentisdue.» Let’s say we have «therenti» parsed so far. This means we know the best parse for each initial substring of this string, e.g., «t», «th», «the», etc. The best parse will probably be «the-rent-i» since each of these is a word and every other parse contains at least one non-word. Now let’s see how the algorithm determines the best parse of «therentis» from this.

After each character in the string we need to decide whether or not to insert a break. Should we insert a space after the first character? Well, yes, since the best parse of a single character is definitely that character. So at the first step we get «t-|herentis.» If we’re favoring single letters over non-words (it’s our choice to make) then the best parse after the second character would be «t-h-|erentis.» After the third, however, the parse is «the-|rentis» since «the» is a word and therefore the best parse of the first three letters is «the» (we know this because, by assumption, we have already computed the best parse for «the»). Next we get «the-r-|entis,» followed by «the-re-|ntis,» and so on, until we get to «the-ren-|tis.» After this step we try «the-rent-|is.» This is a very good parse since we have three words. Finally, we try «the-rent-i-|s,» which has a lower probability than the previous parse because «s» is not a word. Therefore «the-rent-is» is the parse which we save as the best parse of «therentis.»

I implemented this algorithm using C++, which you can download here. By default it uses the KJV Bible as training data, which means what it considers words can be a little funny. For example, «sin» is considered a very common word.