Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Maiya Stokes

Score: 4.5/5

(32 votes)

A hierarchy is an arrangement of items that are represented as being «above», «below», or «at the same level as» one another.

What does hierarchy mean in simple terms?

1 : a group that controls an organization and is divided into different levels The church hierarchy faced resistance to some of their/its decisions. 2 : a system in which people or things are placed in a series of levels with different importance or status He was at the bottom of the corporate hierarchy.

What is hierarchy example?

The definition of hierarchy is a group of people or things arranged in order of rank or the people that rank at the top of such a system. An example of hierarchy is the corporate ladder. An example of hierarchy is the various levels of priests in the Catholic church.

What is the meaning of the word hierarchical ‘?

C2. arranged according to people’s or things’ level of importance, or relating to such a system: The military has a hierarchical rank structure. It’s a very hierarchical organization in which everyone’s status is clearly defined.

What is the definition of the word social hierarchy?

Introduction. Social hierarchies are broadly defined as systems of social organization in which some individuals enjoy a higher social status than others (Sidanius and Pratto 1999) – specifically, in which people are stratified by their group membership (Axte et al. … 2004; Sidanius and Pratto 1999).

32 related questions found

What is human hierarchy?

Human social hierarchies are seen as consisting of a hegemonic group at the top and negative reference groups at the bottom. More powerful social roles are increasingly likely to be occupied by a hegemonic group member (for example, an older white male).

Why is social hierarchy bad?

A hierarchy serves a great purpose in helping every employee in an organization see where they fit in the big picture of things. A hierarchical org chart is very easy to read and makes sense. … Hierarchies can be useful because as much as we don’t like to admit it, most people perform better with some sense of structure.

What is hierarchy explain?

A hierarchy is an organizational structure in which items are ranked according to levels of importance. Most governments, corporations and organized religions are hierarchical. … Most file systems, for example, are based on a hierarchical model in which files are placed somewhere in a hierarchical tree model.

What is the order hierarchy?

Hierarchical order is one of the basic types of systemic organization. When organizing the physical space of urban areas, a hierarchical order has been attempted wherever planned development was feasible and land in abundant supply. … The hierarchy is constructed from the bottom upwards.

What does hierarchy mean in history?

By Satoshi Miura | View Edit History. hierarchy, in the social sciences, a ranking of positions of authority, often associated with a chain of command and control. The term is derived from the Greek words hieros (“sacred”) and archein (“rule” or “order”).

Where do you find hierarchy?

Political systems are hierarchies. In America, the hierarchy starts at the top with the president, and then the vice president, then the speaker of the house, then the president of the Senate, followed by the secretary of state. Your family tree is a hierarchy starting back with your first ancestors.

What is hierarchy in the workplace?

A company’s hierarchy allows employees on different levels to identify the chain of command and serves as a reference point for decision making. A company without a hierarchy cannot effectively hold its executives, managers and employees accountable.

What is hierarchical leadership?

Hierarchical leadership employs a top-down, pyramid-shaped structure with a narrow center of power that trickles down to widening bases of subordinate levels. Nonhierarchical leadership flattens the pyramid to form a structure with decentralized authority and fewer levels.

What does hierarchy family mean?

Psychologists use the term “family hierarchy” to describe the desired and necessary structure for a family. Basically the husband and wife are at the top of the hierarchy, equal to one another, with the children falling under them. Everything within the family stems from the top-level relationship of husband and wife.

Why is hierarchy in a workplace important?

Hierarchy ensures accountability

An effective hierarchy makes leaders accountable for results, and provisions for their replacing failures with someone new — sometimes through internal promotion. That’s how hierarchy ultimately serve the success of the organisation as whole — including owners, managers, and employees.

What is high hierarchy?

noun, plural hi·er·ar·chies. any system of persons or things ranked one above another. government by ecclesiastical rulers. the power or dominion of a hierarch. an organized body of ecclesiastical officials in successive ranks or orders: the Roman Catholic hierarchy.

What is the top of a hierarchy called?

A hierarchy is typically visualized as a pyramid, where the height of the ranking or person depicts their power status and the width of that level represents how many people or business divisions are at that level relative to the whole—the highest-ranking people are at the apex, and there are very few of them, and in …

What are the different types of hierarchy?

Five Types of Hierarchies

- Traditional Hierarchy: It is the most common structure, often popularly known as the «top-down» management style. …

- Flatter Organizations: They are based on fewer layers than the traditional hierarchical companies. …

- Flat Organizations: …

- Flatarchies: …

- Holocratic Organizations:

What is the opposite of a hierarchy?

of or relating to different levels in a hierarchy (as levels of social class or income group) Antonyms: nonhierarchic, nonhierarchical. not classified hierarchically. ungraded, unordered, unranked. not arranged in order hierarchically.

How do you use the word hierarchy?

Hierarchy in a Sentence ?

- In regards to political decisions, the prime minister sits at the top of the British hierarchy.

- The man could not marry the woman he loved because she was born in a level of social hierarchy that fell beneath his family’s rank.

What is meant by hierarchy in public administration?

Literally, hierarchy means rule or control of higher over the lower. Concretely, hierarchy means a graded organization of successive steps or levels in which each of lower level is immediately subordinate to the next higher one and through it, to the other higher steps right upto to top.

What does hierarchy mean in biology?

Biological hierarchy refers to the systemic organisation of organisms into levels, such as the Linnaean taxonomy (a biological classification set up by Carl Linnaeus). It organises living things in descending levels of complexity: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species.

Are humans naturally hierarchical?

Second, hierarchies form quickly and spontaneously among group-living animals. … Further evidence suggests that humans rapidly attribute status information to others (Moors & Houwer, 2005), and they spontaneously organize into a hierarchical structure (e.g., Berger et al. 1980; Gould, 2002).

How does hierarchy affect communication?

A company’s type of organizational structure affects its communications. In the traditional setup – the boss on top, managers beneath and employees at the bottom – the tight, formal hierarchy makes for controlled, formal communication channels. … Unconstrained by formal bureaucratic channels, information spreads quickly.

What is wrong with hierarchy?

The danger of hierarchy is that it tends not to generate a wide range of information. «The more complex the task, the more likely we are to make a mistake or miss something critical» in a hierarchical organization. Hierarchy can also suppress dissent, because people don’t want to take on those at the top.

Hierarchy seems to be the dominant form of human organisations. From the Catholic Church to States, from the Military to most private organisations, we see these pyramid-like organisations everywhere, up to the point that many assume that Hierarchy is a “Natural Order”. Yet the word hierarchy has acquired an almost negative connotation today. Many attacks come to organisational models that are based on Hierarchy, and different options are being put forward. However, when facing the concept itself, it is difficult to simply state that “hierarchy is evil”, and hop on an entirely different system… because, to date, I argue that there is no scalable system that is complete without hierarchical principles.

Through this article, I would try to answer a couple of critical questions:

- What is the origin of the word Hierarchy?

- Is Homo Sapiens a hierarchical being?

- What forms can Hierarchy take within an organisation context?

- What are the

Origins of the Word and meaning across History.

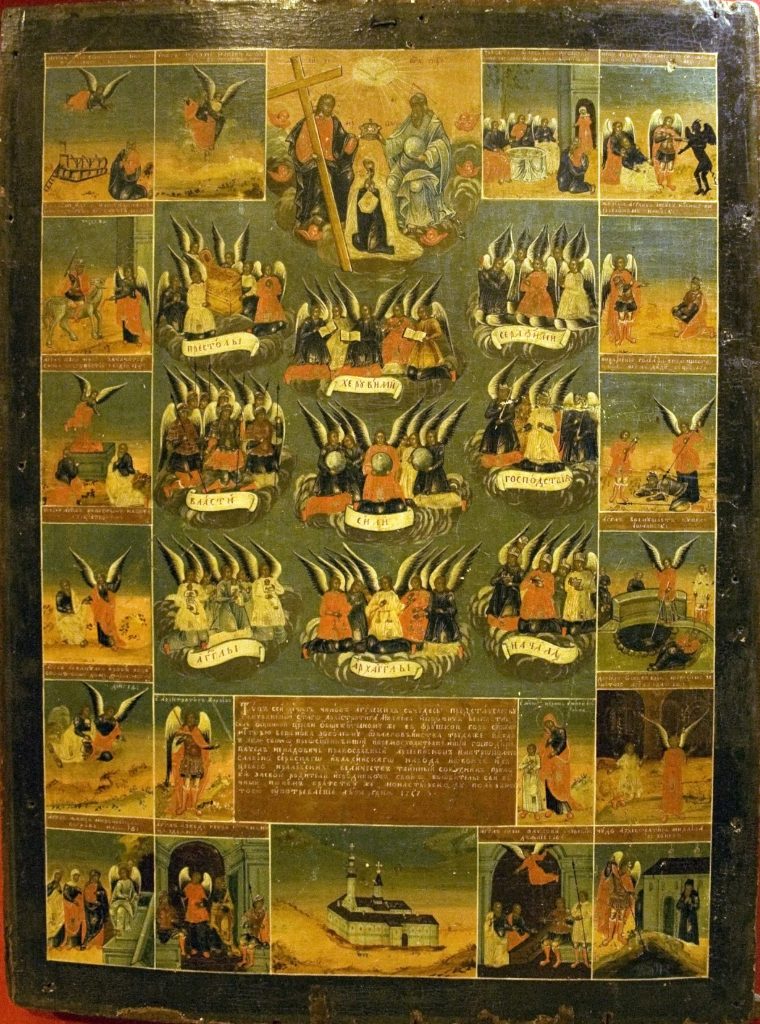

The word Hierarchy dates back to ancient Greece. It seems to have been coined by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in the 6th Century AD. It is made up of ἱερός (hierós, “holy”) + ἄρχω (árkhō, “I rule”). The first clear meaning, linked to its etymology, comes as “the governance of things sacred” (Verdier, 2006). In Theology the word was initially used to refer to the subordination that exists between different levels of Angels. The concept than migrates and is extended to the description of Clergy.

The concept of Hierarchy in the Catholic Church, as a principle derived from God, was at the centre of the dispute between Martin Luther and the Church. It is at the time of the Council of Trento that the word hierarchy was officially adopted to describe the different degrees of the ecclesiastical state. At the same time, it was mandating that opposition to this concept would have been a reason for heresy.

With the French Illuminism and the Encyclopedie, we see for the first time the usage of the word outside a religious context. Hierarchy becomes a “Human Construct” that also applies to society. Several philosophers have been reasoning on the concept of Hierarchy in different domains, especially as a tool for classification and taxonomies. Primarily, any ordered system that entails a subordinate relationship can today be described as a Hierarchy.

When applied to Human Systems, there is a tendency from many authors to consider Hierarchy as a dominant or natural way of arrangement. Almost every system of organisation applied to the world is arranged hierarchically (Kulish, 2002).

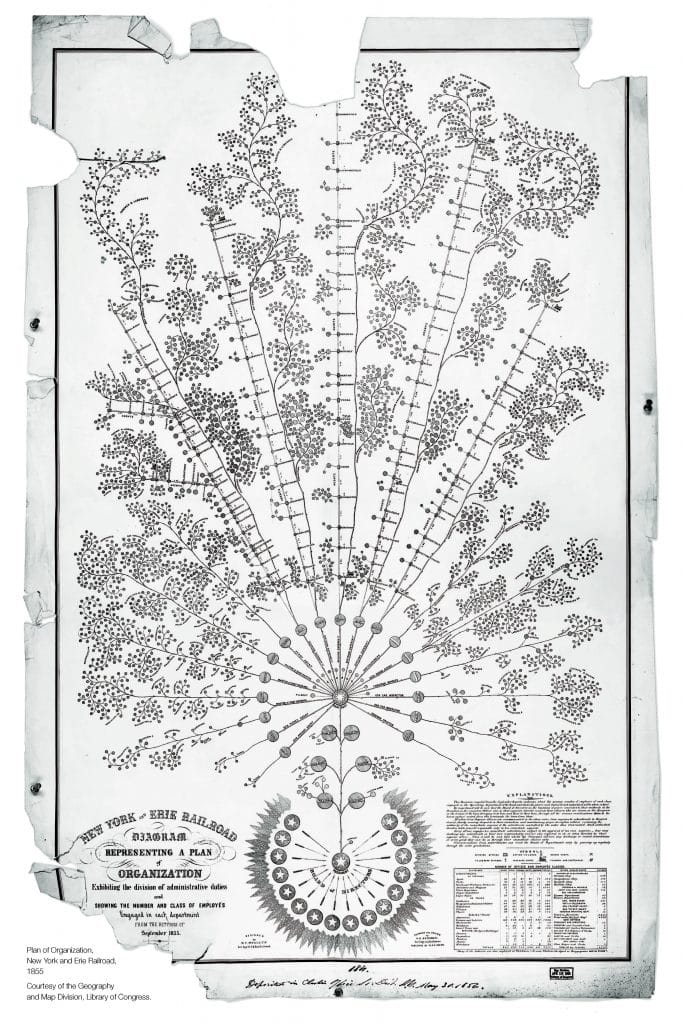

When we speak about Human Organisations, we talk about Hierarchical Structure to show the typical pyramid organisational model, where a manager coordinates the work of several subordinates. By many, it is assumed that there is not an alternative to this model, which at most can be mitigated in its shortcomings. Almost as if that initial connection with gods, was never really removed.

On top of this, there is a tendency to identify Hierarchy also as an “innate behaviour” for animals and the Human Species. But is it really like that?

Homo Sapiens and the desire to command.

Biologists and zoologists have been observing Hierarchical Behaviors among most species on Earth. From Ants to Bonobos, there is a tendency to assume that many species tend to form hierarchies in Nature. We all have clear through the documentaries we have seen, the concept of the “Alpha Male”, particularly relevant among predators (Boehm, 2001). So, is this attitude innate also in Human Beings?

The answer that researcher give in this context is not linear. The reason is that many define Human Beings as having, in reality, egalitarian behaviours. Other primates have tended to express simple hierarchical structures. However, there are among some of the giant apes, practices of collaboration among members forming coalitions to overthrow the dominant male. Resentment of Dominance is apparently also connatural to many hierarchical animals, but only ion few cases there is cooperation among some members.

As the homo sapiens evolved, apparently this collaboration trait became more “useful” also from an evolutionary perspective: this especially when the first communities of gatherers formed, with male hunters often serving as the collective alpha (Calmettes and Weiss, 2017). The theory for many is that a dominance hierarchy of individuals with exclusively self-centred characteristics (the wish to dominate, resentment at being dominated) transitions spontaneously to egalitarianism as their capacity for language develops. Language allows resentment against being dominated to promote the formation of mutually beneficial coalitions which destabilise the alpha position for individuals, leading to a phase transition in which a coalition of the full or part of the population suddenly becomes dominant. This essentially means that hunter–gatherer hierarchies were fluid in character (Erdal and Whiten, 1996) akin to the autonomous work groups promoted by job design researchers and some of the more radical business experiments in self-organized workforces (Nicholson, 2010).

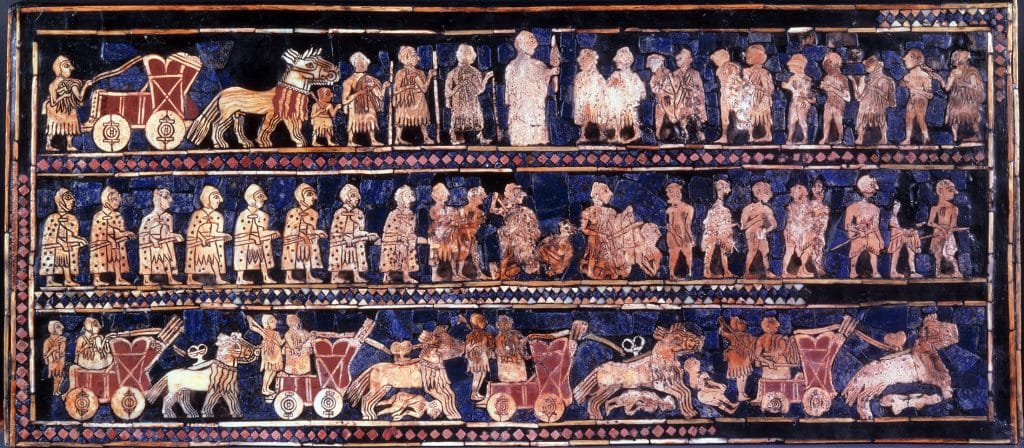

With historical progression, communities of gatherers evolved into larger residential communities. It’s here that new governance systems were created, and where the first hierarchies started to appear. When human societies began to grow, and roles began to specialise, a tipping point happened which pushed for the birth of government systems where a “chief” would dominate, together with a hierarchy of dignitaries (Peterson and Somit, 1997). The fact that in most of these institutions there has been a moment in which the power principle has been linked to some kind of supernatural power, is further testimony to the fact that probably, the human being is not made to live in hierarchies naturally.

Whenever a team of children is put together to solve a problem, we can often observe the primacy of an individual and the formation of a sort of Hierarchy. But this usually is instrumental in reaching the goal, not a prerequisite for action (Fein, 2012). So, why has the hierarchical model had so much success in Human History?

The analysis of Harari in his book Homo Deus comes to help. As he examines what has been the real evolutionary advantage of the Homo Sapiens vs other animals, he mentions the fact that Humans can establish much more extensive networks of collaboration (Harari, 2018). For doing so, Humans have developed complex forms of communication. But, there are limits on which individual relationship are sufficient. Several researchers have set this limit to about 150 people: this is the maximum size by which we can hold a community together without an organisation structure. As smaller communities started to collaborate, there was the necessity to build a way to coordinate these more extensive networks. According to Hariri, this came in the form of a shared narrative, and the development of writing gave the tool required to expand this narrative over time. The development of a hierarchical structure (with bureaucrats, armies and a formal religion) helped then extend each of the narratives also in size (geographically), giving birth to the first empires. And to date, the most enduring forms of human societies (more extensive than a village), have all endured because of a shared narrative. And a Hierarchy is a perfect way to enable and maintain this, accompanying its evolution over time.

So is the Human Being inherently hierarchical? The best answer is that, probably, our Nature is mixed. We are instinctively tuned to Hierarchy, but we have developed an ambition for egalitarianism. The point is that it takes intentional action to be egalitarian, something we might miss in situations of danger or high stress. There is also another essential element to consider: the evolution of our society has created a complex set of multiple hierarchies. Thus each of us belongs to numerous hierarchies at the same time. In our daily life, therefore, we might very well be able to express our competitive spirit in some domains and be egalitarian in others.

Hierarchy and Organisation

As we have seen in the paragraph on History, the word Hierarchy has been used primarily to indicate a way to classify and organise information. Angels were the very first ones, but most taxonomies (if not all of them) today are based on a hierarchical principle, which is why Hierarchy can fundamentally be viewed as a thought tool or a cognitive skill, which enables humans to group things, ideas and concepts into categories (Knuchel, 2018).

Seen this way, the concept of Hierarchy changes altogether. Most models that we use to map knowledge, know-how, competencies, skills, are all hierarchical. The principle itself of the Functional organisation is based not on a hierarchy of power, but rather on a classification of activities. The principle itself of the division of labour (Durkheim, 1984) is nothing but a hierarchical taxonomy applied to the tasks and activities of work.

But how do hierarchies get formed in an organisation? According to the milestone article by Ronald Coase The Nature of the Firm, people begin to organise in firms when an entrepreneur starts hiring people. According to classical economic theory, in the presence of perfect markets, there should not be the need for such an organisation. But Coase saw that the birth of a firm was explicitly linked to the imperfect market and the fact that internal transaction costs within an organisation would be lower than transaction costs within the market. These lower transaction costs are mostly achieved precisely because of the application of a hierarchical principle within the firm: the entrepreneur can govern and organise the work of its employees, who execute directives.

The so-called Theory of the Firm has evolved from the initial transactional cost focus of Coase. However, also other approaches, such as that of William Baumol and Oliver E. Williamson (so-called Managerial Theory) have ended up underlying the inherent existence of a Hierarchical principle in the reality itself of the organisation. Moving the focus from the entrepreneur to the manager, would not change the basic idea: which is that Hierarchy is indisputably part of any organisation.

According to Gerard Fairtlough, however, this is a misconception, as we tend to mix up two critical concepts, both using the word “Organisation”. An organisation is an entity, is a group of people working together for some purpose. Organisation is also an activity, and here the meaning relates to the creation of discipline and order (Fairtlough, 2007).

In his view, there are, in reality, three ways of getting things done in an organisation. He named this triarchy, and here is a quick description of the elements.

- Hierarchy (we know this).

- Heterarchy is the form of structure commonly found in professional-service firms, the partnerships of accountants or lawyers in which key decisions are taken by all the partners jointly.

- Responsible autonomy: here, an individual or a group has the autonomy to decide what to do but is accountable for the outcome of the decision. It is this accountability principle that makes responsible autonomy a valid alternative, very different from anarchy (Fairtlough, 2007). An area where this model works well is scientific research, where individuals or teams work independently, and peer review ensure the respect of scientific principles (Wikipedia Contributors, 2019).

In the view of Fairtlough, the biggest problem is not that we are hardwired to work in a hierarchy, but that we assume Hierarchy is the only way of getting things done.

The hegemony of hierarchy makes us think the only alternative is disorganisation…we only compare hierarchy with anarchy or chaos.

Gerard Fairtlough, The Three Ways of Getting things Done (2007)

Any form of human organisation ends up being based on a division of tasks or knowledge. It’s almost as if every person would be part of an algorithm, and it is the algorithm in itself that takes decisions, acts, executes. This is the essence of bureaucracy (Harari, 2018), genuinely intended in the sense that Max Weber gave, without the negative connotation we often carry. Now, an algorithm is an essential mathematical process, and mathematics is inherently hierarchical.

This creates the shortcut of our view of the world: we tend to assume that any organisation needs to be hierarchical. But we are mixing up several distinct elements, that I will now address separately:

- Hierarchy as a form of organising information.

- Hierarchy as a form of power.

- Hierarchy as a communication flow.

- Hierarchy as a Shared Narrative.

Hierarchy as a way of organising information

We have already mentioned the view of “hierarchy” as a way to classify information and create taxonomies. And we said that important sciences like Mathematics are inherently hierarchical. Let’s see a shortlist of items that are used every day to organise information, and that is based on a hierarchical principle:

- Project Plans and GANTT charts

- Budgets

- Process Flows

- Triage mechanisms and Crisis Planning

- Prioritisation Matrixes

- Benchmarking

- Any of the Business Models Tools we have seen, by excluding parts and helping to focus on others, create a hierarchy.

- Any of the Strategy Frameworks we have seen, look at identifying what is more important and what is less.

- Any of the Operating Model Tools we have seen look at establishing priorities in the way to execute.

- Any of the Change Management methods we have examined establishes a priority of action.

Essentially whenever we have to establish that one thing is more important than another, we are creating a hierarchy. Where things have gone pear-shaped, however, is where Hierarchy has been hijacked by bullies seeking power (Knuchel, 2018).

Hierarchy and Power

The problem with Hierarchy is when this is associated with power and is used as a way to preserve energy. This is where the confusion, mentioned by Fairtlough, becomes dangerous: when we confuse Hierarchy as the sole way to direct an organisation, by applying command and control principles.

How is this achieved? Usually, by segmenting information and avoiding transparency. When few people at the top can really hold on to the bulk of information, and only segment chunks of these of the rest of the organisation is when the pernicious effects of Hierarchy appear. The most visible impact happens when the organisation structure also becomes a channel of communication.

Hierarchy and Communication Flows

I recently reviewed a non-management book: Midnight in Chernobyl. One of the reasons for that review, as mentioned, is that it perfectly illustrates how an organisation can almost implode and destroy itself by blindly following a hierarchical principle, by which each piece of information needs to be routed through the command chain. A realisation that true leaders need make early as they face situations of uncertainty: Ed Catmull mention in his book that one of his earliest discovery of problems at Pixar was when he understood that communication was being held hostage by the organisational structure.

Hierarchy Structures are an effective means of top-down communication. Centuries of combat have shown that armies can be very useful in using this form of organisation. The problem is when feedback loops need to be created to get communication upward. When the bureaucrats at each level want to preserve part of the information power, then everything can slow down and get stuck.

It is this flow of communication aspect, the non-transparency and the power focus that have led to creating a strong sentiment anti-hierarchy, that is more and more diffused around the world. when blindly rejecting Hierarchy indiscriminately on that basis, there is a danger that we do throw the human baby and our core ability to think & prioritise out with the water at the same time. (Knuchel, 2018).

Hierarchology and the Peter’s Principle

We have recently seen through the review of The Peter Principle, some of the other deviations that Hierarchy creates, up to the point that he created a discipline called hierarchology. Besides the ironic tone of most of the book, there are some genuinely valid principles there, including the Peter Principle itself. In a Hierarchy, Every Employee Tends to Rise to His Level of Incompetence. This paradox is probably one of the main reasons why there is a growing sense of resentment towards hierarchies.

Hierarchy and Shared Narrative

What hierarchies have been good at is creating and preserving a Shared Narrative, which is one of the main components in establishing a sense of belonging? Think about the Catholic Church (but also all other significant religions in the world). They all have been portraying hierarchical models, and they all have endured over time. Nation/States are another example of lasting narratives based on hierarchical models.

What’s interesting is that in today’s discussion about the human-centred, network-based organisation, we fail to recognise that we still assume also in the flattest organisation, a hierarchical principle: Purpose.

What’s wrong with Hierarchies?

There is nothing inherently wrong with hierarchies; we have seen this. The fact is that Nature’s default way of working is not Hierarchy, but rather what has been defined as Complex Adaptive Systems. This can be translated “as a system in which large networks of components with no central control and simple rules of operation give rise to complex collective behaviour, sophisticated information processing, and adaptation via learning or evolution.” (Mitchell, 2011). What is most distinctive about complex adaptive systems is that, while they do produce hierarchies as byproducts, the archetype for their fundamental structures is the network (Collins, 2016).

Hierarchies work well in the context of a mechanical system designed to leverage control and maintain equilibrium. But the moment we introduce changing circumstances, the advantage of complex adaptive systems are evident: they are great at leveraging collective learning to adapt to changing conditions.

Here we come to the heart of the organisational design issue. If the primary focus of the organisation is about maintaining control and balance in an ordered world, then Hierarchy is a perfect tool to work with. If instead, the focus is to build an organisation that can adapt to a rapidly changing environment, then we need to seek alternatives forms of organisation. And this should be some form of networks.

A perfect example of a human organisation that is based on some Network principles is our democratic state. Power is not concentrated in a unique source; it is instead distributed across several entities. And democracies foster the development of new forms of collaboration and a new relationship. Thus new nodes are formed (and destroyed) regularly. Is Democracy a perfect system? Probably not. But so far it has demonstrated to be a very resilient one.

Yet somebody would observe that also in a democracy several forms of Hierarchy are present. And this is a correct observation.

Regardless of which orientation is chosen, from a practical perspective, any organisation will contain both hierarchies and networks. That’s because in every Hierarchy, there are networks and, in every network, there are hierarchies.

François Knuchel, Is hierarchy Toxic?

Let’s look at some of the leading examples of networks. One example is Wikipedia. A perfect example of an actual network. Yet, also within Wikipedia, there are some forms of hierarchies. There are System Administrator and Bureaucrats, and there are Stewards. The goal of these roles, however, is not to organise the effort of a large number of people. Instead, they are there to solve exceptions (for example when there is a discussion on a particular topic and consensus among the authors is not reached), ensure that malicious content is kept afar, and working on the oversight of the quality of the tool.

I don’t want to list again the many different forms of organisation that have been presented as alternatives to the traditional Hierarchy, as I have already discussed these in detail in another article. They all try to advocate better options to react to continuous change.

There is, for sure, merit in trying to diminish the levels of middle management in most organisation and to flatten the structure (Minnaar, 2019). But be careful, as long as we keep using words like empowerment, delegation accountability, participation, and so on, we are implicitly recognising the existence of some forms of Hierarchy. People are empowered because somebody is giving permission, delegation implies the possibility to hand part of the responsibility (but also taking it back). Accountability means being held responsible for something… Participation means being part of a decision, but not necessarily making it.

Another word that holds the seeds of Hierarchy is Leadership as it implicitly recognises at least a grading of competence between great leadership and low leadership, if not a distinction between leaders and followers.

The Quest for Self-Management

We can’t and should not get rid of hierarchies fully (Pick, 2018), we instead need to understand in which areas of an organisation they make sense and avoid assuming that the principle applies everywhere. Same way, if we agree on self-management principles to be involved, we need to ensure we think from the very beginning about how to manage exceptions and all those cases where consensus is not reached. An interesting example is the experience of Ricardo Semler with Democracy. Reading the book, it is evident that the experiment of applying democratic principles has been able to mitigate a lot of the issues that traditional organisation structures have. But Semler has been able to hold some form of ultimate power across the entire history of that organisation. And in the end, he decides to sell Semco.

I think that in the quest to establish a real alternative to the traditional Hierarchy, we need to deeper analyse all the components of an organisation design, trying to understand what can be applier where. Self-Management, for example, seems instinctively the best candidate to become the alternative source of focus for many organisations. But what do we do when things don’t work? The advantage of Hierarchy vs other systems is that it gave an intrinsic solution also for all exceptions as well as the possibility to form coalitions that could change the power structure of the organisation (think about all the cases of a management buy-out or M&A). Alternative models yet have to deliver a holistic answer to all these questions. At the same time, we should not consider the argument that we have to wait for the perfect system to appear to start innovating.

In the end, the ideal solution is probably a situational hierarchy where each organisation moves on a slider between full self-management and full top-down Hierarchy and adapts this depending on the environmental situation.

Conclusion

In this lengthy article, I tried to demonstrate a few facts that are important to understand the concept of Hierarchies.

- The word hierarchy is linked initially to religious contexts, a fact that is helpful to understand why we often attribute to a Hierarchy a “supernatural” meaning.

- Homo Sapiens is a species that tends to be equalitarian, rather than hierarchical. However, with the establishment of modern societies that exceeded, in size, that of a small village, some principles of controls pushed humanity to choose hierarchical forms of organisation. In most cases, these have been linked to some kind of spiritual power.

- Hierarchy is a powerful tool to create and maintain a social narrative.

- Hierarchy is a way to organise information. When applied to an organisation we tend to mix the Power aspect with the human necessity of giving a sense to information, using taxonomies and hierarchies. When power is used to subject the information flows, avoiding transparency, we have negative impacts on Hierarchy.

- Alternative models suggested to Hierarchy can be grouped into clusters of Heterarchy or Responsible Autonomy. Yet the question is how to scale organisation that use these principles.

- Traditional Top-Down hierarchies are not “fit for purpose” in VUCA contexts, where constant adaptation and change might be required. But the reality is that we cannot abandon altogether the hierarchical principle in an organisation that we want to scale. There are moments where these will, in any case, be necessary.

- There is not yet an alternative to Hierarchy that is fully versatile and can manage all exceptions. However, this should not push to avoid seeking for alternatives forms. In the end, every organisation will resort to hybrid models, ranging in a spectrum between self-management and Hierarchy.

I’m sure that probably this article raises more questions, rather than giving answers. I wanted to frame the issue with so many of the different points of views that are necessary to grasp it holistically, as it is to easy to shrug off Hierarchy as we don’t need it anymore, without having a clear perception of the alternative.

What do you think about this article? Use the comment form below.

Boehm, C. (2001). Hierarchy in the forest : the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Calmettes, G. and Weiss, J.N. (2017). The emergence of egalitarianism in a model of early human societies. Heliyon, 3(11), p.e00451.

Collins, R. (2016). Is Hierarchy Really Necessary? [online] HuffPost. Available at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/is-hierarchy-really-neces_b_9850168 [Accessed 17 May 2020].

Durkheim, É. (1984). The division of labour in society. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Fairtlough, G. (2007). The Three Ways of Getting Things Done: Hierarchy, Heterarchy and Responsible Autonomy in Organization. Triarchy Press.

Fein, M.L. (2012). Human Hierarchies: A General Theory. 1st Edition ed. Transaction Publishers.

Harari, Y.N. (2018). Homo deus : a brief history of tomorrow. New York, Ny: Harper Perennial.

Knuchel, F. (2018). Is Hierarchy Toxic? [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/humanorganisingco/the-issue-with-hierarchy-a986f62963a5 [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Kulish, V.V. (2002). Hierarchical Methods. 1st Edition ed. Amsterdam: Springer.

Lane, D. (2006). Hierarchy, Complexity, Society. In: D. Pumain, ed., Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences. Amsterdam: Springer, pp.81–119.

Minnaar, J. (2019). 4 Future-Proof Organizational Models Beyond Hierarchy And Bureaucracy. [online] Corporate Rebels. Available at: https://corporate-rebels.com/4-future-proof-organizational-models-beyond-hierarchy-and-bureaucracy/ [Accessed 18 May 2020].

Mitchell, M. (2011). Complexity : a guided tour. New York ; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nilaya, J. (2015). Understanding Hierarchies in Nature and Society. [online] http://www.wnpr.org. Available at: https://www.wnpr.org/post/understanding-hierarchies-nature-and-society [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Peterson, S. and Somit, A. (1997). Darwinism, Dominance, and Democracy: The Biological Bases of Authoritarianism. Praeger.

Pick, F. (2018). Busting The Myth: Organizations With No Hierarchy Don’t Exist. [online] Corporate Rebels. Available at: https://corporate-rebels.com/busting-the-myth/ [Accessed 20 Nov. 2019].

Verdier, N. (2006). Hierarchy: A Short History of a Word in Western Thought. In: D. Pumain, ed., Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences. Amsterdam: Springer, pp.13–37.

Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Responsible autonomy. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Responsible_autonomy [Accessed 15 May 2020].

show less

Cover Photo by Edvard Alexander Rølvaag on Unsplash

2

a

: a ruling body of clergy organized into orders or ranks each subordinate to the one above it

especially

: the bishops of a province or nation

b

: church government by a hierarchy

3

: a body of persons in authority

4

: the classification of a group of people according to ability or to economic, social, or professional standing

also

: the group so classified

5

: a graded or ranked series

Did you know?

The earliest meaning of hierarchy in English has to do with the ranks of different types of angels in the celestial order. The idea of categorizing groups according to rank readily transferred to the organization of priestly or other governmental rule. The word hierarchy is, in fact, related to a number of governmental words in English, such as monarchy, anarchy, and oligarchy, although it itself is now very rarely used in relation to government.

The word comes from the Greek hierarchēs, which was formed by combining the words hieros, meaning “supernatural, holy,” and archos, meaning. “ruler.” Hierarchy has continued to spread its meaning beyond matters ecclesiastical and governmental, and today is commonly found used in reference to any one of a number of different forms of graded classification.

Synonyms

Example Sentences

… he wrote a verse whose metaphors were read somewhere in the Baathist hierarchy as incitement to Kurdish nationalism.

—

Whereas the monkeys normally hew to strict hierarchies when it comes to who gets the best food and who grooms whom, there are no obvious top or rotten bananas in the sharing of millipede secretions.

—

The idea that social order has to come from a centralized, rational, bureaucratic hierarchy was very much associated with the industrial age.

—

The church hierarchy faced resistance to some of their decisions.

He was at the bottom of the corporate hierarchy.

a rigid hierarchy of social classes

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

There was no sense of hierarchy.

—

But its time at the top of the 3-series hierarchy will be limited.

—

Having been home-schooled most of her life, Cady is spectacularly unprepared for the trials and tribulations of high school hierarchy.

—

From his love stories to his experiences of the caste hierarchy in our region Maharashtra.

—

Common communication bottlenecks can occur for any organization and at any level of its hierarchy, leading to limited flow of information that impacts scheduling efforts and use of resources.

—

The origins of the caste system in India can be traced back 3,000 years as a social hierarchy based on one’s occupation and birth.

—

The origins of the caste system in India can be traced back 3,000 years as a social hierarchy based on one’s occupation and birth.

—

Now, Prigozhin’s long-running criticism of the military hierarchy, once oblique, has taken on an aggressive, even desperate tone, just as the battle for Bakhmut appears to be entering a critical phase.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘hierarchy.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle English ierarchie rank or order of holy beings, from Anglo-French jerarchie, from Medieval Latin hierarchia, from Late Greek, from Greek hierarchēs

First Known Use

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Time Traveler

The first known use of hierarchy was

in the 14th century

Dictionary Entries Near hierarchy

Cite this Entry

“Hierarchy.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hierarchy. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on hierarchy

Last Updated:

7 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Table of Contents

- What does the word hierarchy mean in a sentence?

- What type of word is hierarchy?

- What is human hierarchy?

- What is an example of social hierarchy?

- Why is social hierarchy bad?

- Do we need hierarchy?

- Why a hierarchy is important?

- What is your hierarchy?

- What is the hierarchy of leadership?

- What is hierarchy culture?

- How do you manage hierarchy?

- How can we prevent hierarchy?

- How do you solve a hierarchy problem?

- What is reduce hierarchy?

- How do you establish a hierarchy?

a system in which people or things are arranged according to their importance: Some monkeys have a very complex social hierarchy. He rose quickly through the political hierarchy to become party leader. the people in the upper levels of an organization who control it. SMART Vocabulary: related words and phrases.

What type of word is hierarchy?

noun, plural hi·er·ar·chies. any system of persons or things ranked one above another. government by ecclesiastical rulers. the power or dominion of a hierarch. an organized body of ecclesiastical officials in successive ranks or orders: the Roman Catholic hierarchy.

What is human hierarchy?

To begin, hierarchy refers to the ranking of members in social groups based on the power, influence, or dominance they exhibit, whereby some members are superior or subordinate to others (Fiske, 2010; Magee & Galinsky, 2008; Mazur, 1985; Zitek & Tiedens, 2012).

Social hierarchies are omnipresent in the lives of many species. For example, reliance on status cues to organize important social behavior is identified in ants1 and other insects, such as bees, who infer higher ranking in the social hierarchy based on physical body size.

A one-sided, top-down hierarchy can stifle the employee experience and leave workers with a lack of power and control over their situations. The future of work is moving towards organizations where employees feel valued and have the tools they need to reach their potential.

Do we need hierarchy?

Hierarchies add structure and regularity to our lives. They give us routines, duties, and responsibilities. We may not realize that we need such things until we lose them.

Why a hierarchy is important?

A hierarchy helps to establish efficient communication paths between employees, departments and divisions of the company. The manager of each department becomes the departmental administrator, and any information that is relevant to the department is given to the manager.

What is your hierarchy?

A hierarchy is an organizational structure in which items are ranked according to levels of importance. The computer memory hierarchy ranks components in terms of response times, with processor registers at the top of the pyramid structure and tape backup at the bottom.

What is the hierarchy of leadership?

In a hierarchical organization, leaders organize subordinates into a pyramid-like structure. At the lowest level, less-experienced employees take direction from supervisors and managers at higher levels. Communication typically flows from the top to the bottom.

What is hierarchy culture?

1. An organizational culture that focuses on the development and maintenance of stable organizational rules, structures, and processes, by implementing a hierarchical system of power and management.

How do you manage hierarchy?

Here are ten ways to help foster a connection between executives and their staff and create a more successful company employee hierarchy.

- Adopt a Mobile-First Communication Tool.

- Flatten Communication Hierarchy with Open Communication Channels.

- Lead by Example.

- Encourage Engagement to Get Employee Buy-In.

How can we prevent hierarchy?

Here are a few pieces of advice to help tackle hierarchy in the workplace.

- Initiate shared responsibility rules.

- Redefine roles and responsibilities.

- Give junior team members the floor.

- If possible, trial an open-plan office space.

- Respect at every level.

How do you solve a hierarchy problem?

Supersymmetry can explain how a tiny Higgs mass can be protected from quantum corrections. Supersymmetry removes the power-law divergences of the radiative corrections to the Higgs mass and solves the hierarchy problem as long as the supersymmetric particles are light enough to satisfy the Barbieri–Giudice criterion.

What is reduce hierarchy?

Delayering is a means of simplifying management structures, reducing bureaucracy, cutting communication paths, speeding up decision-making and pushing responsibility down to lower organizational levels.

How do you establish a hierarchy?

How to Establish Visual Hierarchy

- Contrast. Contrast is employed by using typographic styles that are vastly different to distinguish areas in a design.

- Scale. Scale is the easiest way to establish visual hierarchy.

- Color. Color can clearly differentiate areas of information and with great effect, but one should use it carefully.

- Space.

- Alignment.

«Subordinate» redirects here. For other uses, see Subordination.

A hierarchy (from Greek: ἱεραρχία, hierarkhia, ‘rule of a high priest’, from hierarkhes, ‘president of sacred rites’) is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being «above», «below», or «at the same level as» one another. Hierarchy is an important concept in a wide variety of fields, such as architecture, philosophy, design, mathematics, computer science, organizational theory, systems theory, systematic biology, and the social sciences (especially political science).

A hierarchy can link entities either directly or indirectly, and either vertically or diagonally. The only direct links in a hierarchy, insofar as they are hierarchical, are to one’s immediate superior or to one of one’s subordinates, although a system that is largely hierarchical can also incorporate alternative hierarchies. Hierarchical links can extend «vertically» upwards or downwards via multiple links in the same direction, following a path. All parts of the hierarchy that are not linked vertically to one another nevertheless can be «horizontally» linked through a path by traveling up the hierarchy to find a common direct or indirect superior, and then down again. This is akin to two co-workers or colleagues; each reports to a common superior, but they have the same relative amount of authority. Organizational forms exist that are both alternative and complementary to hierarchy. Heterarchy is one such form.

Nomenclature[edit]

Hierarchies have their own special vocabulary. These terms are easiest to understand when a hierarchy is diagrammed (see below).

In an organizational context, the following terms are often used related to hierarchies:[1][2]

- Object: one entity (e.g., a person, department or concept or element of arrangement or member of a set)

- System: the entire set of objects that are being arranged hierarchically (e.g., an administration)

- Dimension: another word for «system» from on-line analytical processing (e.g. cubes)

- Member: an (element or object) at any (level or rank) in a (class-system, taxonomy or dimension)

- Terms about Positioning

- Rank: the relative value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level etc. of an object

- Level or Tier: a set of objects with the same rank OR importance

- Ordering: the arrangement of the (ranks or levels)

- Hierarchy: the arrangement of a particular set of members into (ranks or levels). Multiple hierarchies are possible per (dimension taxonomy or Classification-system), in which selected levels of the dimension are omitted to flatten the structure

- Terms about Placement

- Hierarch, the apex of the hierarchy, consisting of one single orphan (object or member) in the top level of a dimension. The root of an inverted-tree structure

- Member, a (member or node) in any level of a hierarchy in a dimension to which (superior and subordinate) members are attached

- Orphan, a member in any level of a dimension without a parent member. Often the apex of a disconnected branch. Orphans can be grafted back into the hierarchy by creating a relationship (interaction) with a parent in the immediately superior level

- Leaf, a member in any level of a dimension without subordinates in the hierarchy

- Neighbour: a member adjacent to another member in the same (level or rank). Always a peer.

- Superior: a higher level or an object ranked at a higher level (A parent or an ancestor)

- Subordinate: a lower level or an object ranked at a lower level (A child or a descendant)

- Collection: all of the objects at one level (i.e. Peers)

- Peer: an object with the same rank (and therefore at the same level)

- Interaction: the relationship between an object and its direct superior or subordinate (i.e. a superior/inferior pair)

- a direct interaction occurs when one object is on a level exactly one higher or one lower than the other (i.e., on a tree, the two objects have a line between them)

- Distance: the minimum number of connections between two objects, i.e., one less than the number of objects that need to be «crossed» to trace a path from one object to another

- Span: a qualitative description of the width of a level when diagrammed, i.e., the number of subordinates an object has

- Terms about Nature

- Attribute: a heritable characteristic of (members and their subordinates) in a level (e.g. hair-colour)

- Attribute-value: the specific value of a heritable characteristic (e.g. Auburn)

In a mathematical context (in graph theory), the general terminology used is different.

Most hierarchies use a more specific vocabulary pertaining to their subject, but the idea behind them is the same. For example, with data structures, objects are known as nodes, superiors are called parents and subordinates are called children. In a business setting, a superior is a supervisor/boss and a peer is a colleague.

Degree of branching [edit]

Degree of branching refers to the number of direct subordinates or children an object has (in graph theory, equivalent to the number of other vertices connected to via outgoing arcs, in a directed graph) a node has. Hierarchies can be categorized based on the «maximum degree», the highest degree present in the system as a whole. Categorization in this way yields two broad classes: linear and branching.

In a linear hierarchy, the maximum degree is 1.[1] In other words, all of the objects can be visualized in a line-up, and each object (excluding the top and bottom ones) has exactly one direct subordinate and one direct superior. Note that this is referring to the objects and not the levels; every hierarchy has this property with respect to levels, but normally each level can have an infinite number of objects. An example of a linear hierarchy is the hierarchy of life.

In a branching hierarchy, one or more objects has a degree of 2 or more (and therefore the minimum degree is 2 or higher).[1] For many people, the word «hierarchy» automatically evokes an image of a branching hierarchy.[1] Branching hierarchies are present within numerous systems, including organizations and classification schemes. The broad category of branching hierarchies can be further subdivided based on the degree.

A flat hierarchy (also known for companies as flat organization) is a branching hierarchy in which the maximum degree approaches infinity, i.e., that has a wide span.[2] Most often, systems intuitively regarded as hierarchical have at most a moderate span. Therefore, a flat hierarchy is often not viewed as a hierarchy at all. For example, diamonds and graphite are flat hierarchies of numerous carbon atoms that can be further decomposed into subatomic particles.

An overlapping hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which at least one object has two parent objects.[1] For example, a graduate student can have two co-supervisors to whom the student reports directly and equally, and who have the same level of authority within the university hierarchy (i.e., they have the same position or tenure status).

Etymology[edit]

Possibly the first use of the English word hierarchy cited by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1881, when it was used in reference to the three orders of three angels as depicted by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th–6th centuries). Pseudo-Dionysius used the related Greek word (ἱεραρχία, hierarchia) both in reference to the celestial hierarchy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy.[3] The Greek term hierarchia means ‘rule of a high priest’,[4] from hierarches (ἱεράρχης, ‘president of sacred rites, high-priest’)[5] and that from hiereus (ἱερεύς, ‘priest’)[6] and arche (ἀρχή, ‘first place or power, rule’).[7] Dionysius is credited with first use of it as an abstract noun.

Since hierarchical churches, such as the Roman Catholic (see Catholic Church hierarchy) and Eastern Orthodox churches, had tables of organization that were «hierarchical» in the modern sense of the word (traditionally with God as the pinnacle or head of the hierarchy), the term came to refer to similar organizational methods in secular settings.

Representing hierarchies[edit]

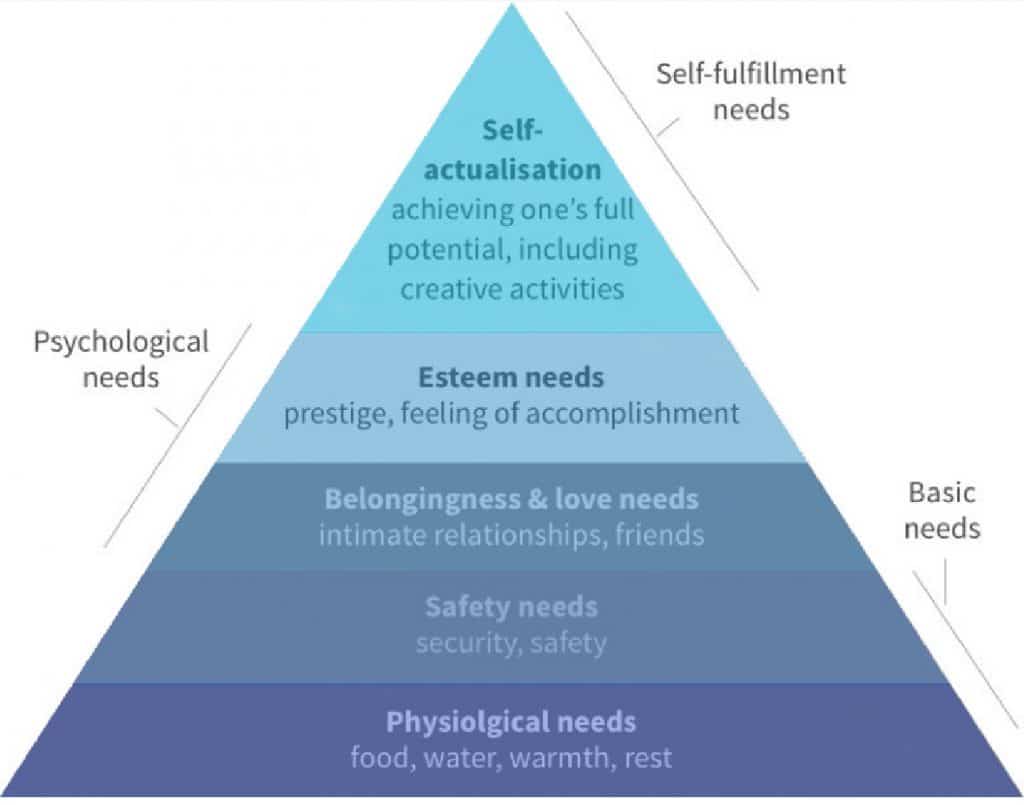

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. This is an example of a hierarchy visualized with a triangle diagram. The hierarchical aspect represented here is that needs at lower levels of the pyramid are considered more basic and must be fulfilled before higher ones are met.

A hierarchy is typically depicted as a pyramid, where the height of a level represents that level’s status and width of a level represents the quantity of items at that level relative to the whole.[8] For example, the few Directors of a company could be at the apex, and the base could be thousands of people who have no subordinates.

These pyramids are often diagrammed with a triangle diagram which serves to emphasize the size differences between the levels (but note that not all triangle/pyramid diagrams are hierarchical; for example, the 1992 USDA food guide pyramid). An example of a triangle diagram appears to the right.

Another common representation of a hierarchical scheme is as a tree diagram. Phylogenetic trees, charts showing the structure of § Organizations, and playoff brackets in sports are often illustrated this way.

More recently, as computers have allowed the storage and navigation of ever larger data sets, various methods have been developed to represent hierarchies in a manner that makes more efficient use of the available space on a computer’s screen. Examples include fractal maps, TreeMaps and Radial Trees.

Visual hierarchy[edit]

In the design field, mainly graphic design, successful layouts and formatting of the content on documents are heavily dependent on the rules of visual hierarchy. Visual hierarchy is also important for proper organization of files on computers.

An example of visually representing hierarchy is through nested clusters. Nested clusters represent hierarchical relationships using layers of information. The child element is within the parent element, such as in a Venn diagram. This structure is most effective in representing simple hierarchical relationships. For example, when directing someone to open a file on a computer desktop, one may first direct them towards the main folder, then the subfolders within the main folder. They will keep opening files within the folders until the designated file is located.

For more complicated hierarchies, the stair structure represents hierarchical relationships through the use of visual stacking. Visually imagine the top of a downward staircase beginning at the left and descending on the right. Child elements are towards the bottom of the stairs and parent elements are at the top. This structure represents hierarchical relationships through the use of visual stacking.

Informal representation[edit]

In plain English, a hierarchy can be thought of as a set in which:[1]

- No element is superior to itself, and

- One element, the (apex or hierarch), is superior to all of the other elements in the set.

The first requirement is also interpreted to mean that a hierarchy can have no circular relationships; the association between two objects is always transitive.

The second requirement asserts that a hierarchy must have a leader or root that is common to all of the objects.

Mathematical representation[edit]

Mathematically, in its most general form, a hierarchy is a partially ordered set or poset.[9] The system in this case is the entire poset, which is constituted of elements. Within this system, each element shares a particular unambiguous property. Objects with the same property value are grouped together, and each of those resulting levels is referred to as a class.

«Hierarchy» is particularly used to refer to a poset in which the classes are organized in terms of increasing complexity.

Operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are often performed in a certain sequence or order. Usually, addition and subtraction are performed after multiplication and division has already been applied to a problem. The use of parentheses is also a representation of hierarchy, for they show which operation is to be done prior to the following ones. For example:

(2 + 5) × (7 — 4).

In this problem, typically one would multiply 5 by 7 first, based on the rules of mathematical hierarchy. But when the parentheses are placed, one will know to do the operations within the parentheses first before continuing on with the problem. These rules are largely dominant in algebraic problems, ones that include several steps to solve. The use of hierarchy in mathematics is beneficial to quickly and efficiently solve a problem without having to go through the process of slowly dissecting the problem. Most of these rules are now known as the proper way into solving certain equations.

Subtypes[edit]

Nested hierarchy[edit]

Matryoshka dolls, also known as nesting dolls or Russian dolls. Each doll is encompassed inside another until the smallest one is reached. This is the concept of nesting. When the concept is applied to sets, the resulting ordering is a nested hierarchy.

A nested hierarchy or inclusion hierarchy is a hierarchical ordering of nested sets.[10] The concept of nesting is exemplified in Russian matryoshka dolls. Each doll is encompassed by another doll, all the way to the outer doll. The outer doll holds all of the inner dolls, the next outer doll holds all the remaining inner dolls, and so on. Matryoshkas represent a nested hierarchy where each level contains only one object, i.e., there is only one of each size of doll; a generalized nested hierarchy allows for multiple objects within levels but with each object having only one parent at each level. The general concept is both demonstrated and mathematically formulated in the following example:

A square can always also be referred to as a quadrilateral, polygon or shape. In this way, it is a hierarchy. However, consider the set of polygons using this classification. A square can only be a quadrilateral; it can never be a triangle, hexagon, etc.

Nested hierarchies are the organizational schemes behind taxonomies and systematic classifications. For example, using the original Linnaean taxonomy (the version he laid out in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae), a human can be formulated as:[11]

Taxonomies may change frequently (as seen in biological taxonomy), but the underlying concept of nested hierarchies is always the same.

In many programming taxonomies and syntax models (as well as fractals in mathematics), nested hierarchies, including Russian dolls, are also used to illustrate the properties of self-similarity and recursion. Recursion itself is included as a subset of hierarchical programming, and recursive thinking can be synonymous with a form of hierarchical thinking and logic.[12]

Containment hierarchy[edit]

A containment hierarchy is a direct extrapolation of the nested hierarchy concept. All of the ordered sets are still nested, but every set must be «strict»—no two sets can be identical. The shapes example above can be modified to demonstrate this:

The notation

A general example of a containment hierarchy is demonstrated in class inheritance in object-oriented programming.

Two types of containment hierarchies are the subsumptive containment hierarchy and the compositional containment hierarchy. A subsumptive hierarchy «subsumes» its children, and a compositional hierarchy is «composed» of its children. A hierarchy can also be both subsumptive and compositional[example needed].[13]

Subsumptive containment hierarchy[edit]

A subsumptive containment hierarchy is a classification of object classes from the general to the specific. Other names for this type of hierarchy are «taxonomic hierarchy» and «IS-A hierarchy».[9][14][15] The last term describes the relationship between each level—a lower-level object «is a» member of the higher class. The taxonomical structure outlined above is a subsumptive containment hierarchy. Using again the example of Linnaean taxonomy, it can be seen that an object that is a member of the level Mammalia «is a» member of the level Animalia; more specifically, a human «is a» primate, a primate «is a» mammal, and so on. A subsumptive hierarchy can also be defined abstractly as a hierarchy of «concepts».[15] For example, with the Linnaean hierarchy outlined above, an entity name like Animalia is a way to group all the species that fit the conceptualization of an animal.

Compositional containment hierarchy[edit]

A compositional containment hierarchy is an ordering of the parts that make up a system—the system is «composed» of these parts.[16] Most engineered structures, whether natural or artificial, can be broken down in this manner.

The compositional hierarchy that every person encounters at every moment is the hierarchy of life. Every person can be reduced to organ systems, which are composed of organs, which are composed of tissues, which are composed of cells, which are composed of molecules, which are composed of atoms. In fact, the last two levels apply to all matter, at least at the macroscopic scale. Moreover, each of these levels inherit all the properties of their children.

In this particular example, there are also emergent properties—functions that are not seen at the lower level (e.g., cognition is not a property of neurons but is of the brain)—and a scalar quality (molecules are bigger than atoms, cells are bigger than molecules, etc.). Both of these concepts commonly exist in compositional hierarchies, but they are not a required general property. These level hierarchies are characterized by bi-directional causation.[10] Upward causation involves lower-level entities causing some property of a higher level entity; children entities may interact to yield parent entities, and parents are composed at least partly by their children. Downward causation refers to the effect that the incorporation of entity x into a higher-level entity can have on x’s properties and interactions. Furthermore, the entities found at each level are autonomous.

Contexts and applications[edit]

Kulish (2002) suggests that almost every system of organization which humans apply to the world is arranged hierarchically.[17][need quotation to verify] Some conventional definitions of the terms «nation»[18][failed verification] and «government»[19][failed verification] suggest that every nation has a government and that every government is hierarchical. Sociologists can analyse socioeconomic systems in terms of stratification into a social hierarchy (the social stratification of societies), and all systematic classification schemes (taxonomies) are hierarchical.[20] Most organized religions, regardless of their internal governance structures, operate as a hierarchy under deities and priesthoods. Many Christian denominations have an autocephalous ecclesiastical hierarchy of leadership. Families can be viewed as hierarchical structures in terms of cousinship (e.g., first cousin once removed, second cousin, etc.), ancestry (as depicted in a family tree) and inheritance (succession and heirship). All the requisites of a well-rounded life and lifestyle can be organized using Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs — according to Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. Learning steps often follow a hierarchical scheme—to master differential equations one must first learn calculus; to learn calculus one must first learn elementary algebra; and so on. Nature offers hierarchical structures, as numerous schemes such as Linnaean taxonomy, the organization of life, and biomass pyramids attempt to document. Hierarchies are so infused into daily life that they are viewed[by whom?] as trivial.[21][need quotation to verify][22]

While the above examples are often[quantify] clearly depicted in a hierarchical form and are classic examples, hierarchies exist in numerous systems where this branching structure is not immediately apparent. For example, most postal-code systems are hierarchical. Using the Canadian postal code system as an example, the top level’s binding concept, the «postal district», consists of 18 objects (letters). The next level down is the «zone», where the objects are the digits 0–9. This is an example of an overlapping hierarchy, because each of these 10 objects has 18 parents. The hierarchy continues downward to generate, in theory, 7,200,000 unique codes of the format A0A 0A0 (the second and third letter positions allow 20 objects each). Most library classification systems are also hierarchical. The Dewey Decimal System is infinitely hierarchical because there is no finite bound on the number of digits can be used after the decimal point.[23]

Organizations[edit]

Organizations can be structured[by whom?] as a dominance hierarchy. In an organizational hierarchy, there is a single person or group with the most power or authority, and each subsequent level represents a lesser authority. Most organizations are structured in this manner,[24] including governments, companies, armed forces, militia and organized religions. The units or persons within an organization may be depicted hierarchically in an organizational chart.

In a reverse hierarchy, the conceptual pyramid of authority is turned upside-down, so that the apex is at the bottom and the base is at the top. This mode represents the idea that members of the higher rankings are responsible for the members of the lower rankings.

Biology[edit]

Empirically, when we observe in nature a large proportion of the (complex) biological systems, they exhibit hierarchic structure.[25] On theoretical grounds we could expect complex systems to be hierarchies in a world in which complexity had to evolve from simplicity.[26] System hierarchies analysis performed in the 1950s,[27][28] laid the empirical foundations for a field that would become, from the 1980s, hierarchical ecology.[29][30][31][32][33]

The theoretical foundations are summarized by thermodynamics.

When biological systems are modeled as physical systems, in the most general abstraction, they are thermodynamic open systems that exhibit self-organised behavior, and the set/subset relations between dissipative structures can be characterized[by whom?] in a hierarchy.

Other hierarchical representations related to biology include ecological pyramids which illustrate energy flow or trophic levels in ecosystems, and taxonomic hierarchies, including the Linnean classification scheme and phylogenetic trees that reflect inferred patterns of evolutionary relationship among living and extinct species.

Computer-graphic imaging[edit]

CGI and computer-animation programs mostly use hierarchies for models. On a 3D model of a human for example, the chest is a parent of the upper left arm, which is a parent of the lower left arm, which is a parent of the hand. This pattern is used in modeling and animation for almost everything built as a 3D digital model.

Linguistics[edit]

Many grammatical theories, such as phrase-structure grammar, involve hierarchy.

Direct–inverse languages such as Cree and Mapudungun distinguish subject and object on verbs not by different subject and object markers, but via a hierarchy of persons.

In this system, the three (or four with Algonquian languages) persons occur in a hierarchy of salience. To distinguish which is subject and which object, inverse markers are used if the object outranks the subject.

On the other hand, languages include a variety of phenomena that are not hierarchical. For example, the relationship between a pronoun and a prior noun-phrase to which it refers commonly crosses grammatical boundaries in non-hierarchical ways.

Music[edit]

The structure of a musical composition is often understood hierarchically (for example by Heinrich Schenker (1768–1835, see Schenkerian analysis), and in the (1985) Generative Theory of Tonal Music, by composer Fred Lerdahl and linguist Ray Jackendoff). The sum of all notes in a piece is understood to be an all-inclusive surface, which can be reduced to successively more sparse and more fundamental types of motion. The levels of structure that operate in Schenker’s theory are the foreground, which is seen in all the details of the musical score; the middle ground, which is roughly a summary of an essential contrapuntal progression and voice-leading; and the background or Ursatz, which is one of only a few basic «long-range counterpoint» structures that are shared in the gamut of tonal music literature.

The pitches and form of tonal music are organized hierarchically, all pitches deriving their importance from their relationship to a tonic key, and secondary themes in other keys are brought back to the tonic in a recapitulation of the primary theme.

Examples of other applications[edit]

Information-based[edit]

|

City planning-based[edit]

|

Linguistics-oriented[edit]

|

[edit]

|

[edit]

|

Perception-based[edit]

|

History-oriented[edit]

|

Science-focussed[edit]

|

Technology-based[edit]

|

[edit]

- Levels of consciousness

- Chakras

- Great chain of being

- G.I. Gurdjieff

- Timothy Leary

- Levels of spiritual development

- In Theravada Buddhism

- In Mahayana Buddhism

- In Theosophy

- Ages in the evolution of society

- In Astrology

- In Hellenism (the Ancient Greek Religion)

- Dispensations in Protestantism

- Dispensations in Mormonism

- Degrees of communion between various Christian churches

- UFO religions

- Command hierarchy of the Ashtar Galactic Command flying saucer fleet

- Deities

- In Japanese Buddhism

- In Theosophy

- Angels

- In Christianity

- In Islam

- In Judaism

- Kabbalistic

- In Zoroastrianism

- Devils and Demons

- Devils

- Demons

- Hells

- In Catholicism (Nine Levels of Hell)

- In Buddhism (Sixteen Levels of Hell)

- Religions in society

- (organizational hierarchies are listed under «Power- or authority-based»)

Methods using hierarchy[edit]

- Analytic Hierarchy Process

- Hierarchical Decision Process

- Hierarchic Object-Oriented Design

- Hierarchical Bayes model

- Hierarchical clustering

- Hierarchical clustering of networks

- Hierarchical constraint satisfaction

- Hierarchical linear modeling

- Hierarchical modulation

- Hierarchical proportion

- Hierarchical radial basis function

- Hierarchical storage management

- Hierarchical task network

- Hierarchical temporal memory

- Hierarchical token bucket

- Hierarchical visitor pattern

- Presentation-abstraction-control

- Hierarchical-Model-View-Controller

Criticisms[edit]

In the work of diverse theorists such as William James (1842 to 1910), Michel Foucault (1926 to 1984) and Hayden White (1928 to 2018), important critiques of hierarchical epistemology are advanced. James famously asserts in his work Radical Empiricism that clear distinctions of type and category are a constant but unwritten goal of scientific reasoning, so that when they are discovered, success is declared. But if aspects of the world are organized differently, involving inherent and intractable ambiguities, then scientific questions are often considered unresolved.

Feminists, Marxists, anarchists, communists, critical theorists and others, all of whom have multiple interpretations, criticize the hierarchies commonly found within human society, especially in social relationships. Hierarchies are present in all parts of society: in businesses, schools, families, etc. These relationships are often viewed as necessary. Entities that stand in hierarchical arrangements are animals, humans, plants, etc.

Ethics, behavioral psychology, philosophies of identity[edit]

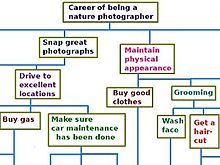

Career-oriented purposes can be diagrammed using a hierarchy describing how less important actions support a larger goal.

In ethics, various virtues are enumerated and sometimes organized hierarchically according to certain brands of virtue theory.

In some of these random examples, there is an asymmetry of ‘compositional’ significance between levels of structure, so that small parts of the whole hierarchical array depend, for their meaning, on their membership in larger parts. There is a hierarchy of activities in human life: productive activity serves or is guided by the moral life; the moral life is guided by practical reason; practical reason (used in moral and political life) serves contemplative reason (whereby we contemplate God). Practical reason sets aside time and resources for contemplative reason.

See also[edit]

- Anarchy

- Class browser

- Forms of government

- Graph theory

- Heterarchy

- Hierarchical classifier

- Hierarchical epistemology

- Hierarchical hidden Markov model

- Hierarchical INTegration

- Hierarchical Music Specification Language

- Hierarchy Open Service Interface Definition

- Hierarchy problem

- Holarchy § Different meanings

- Instrumental value

- Layer (disambiguation)

- Multilevel model

- Multitree

- Ordinary (officer)

- Characters of Halo § High Prophets

- List of Coptic Orthodox Popes of Alexandria

- Peter Principle

- Ring (computer security)

- Social dominance theory

[edit]

(For example, in § Subtypes)

- Is-a

- Hypernymy (and supertype)

- Hyponymy (and subtype)

- Has-a

- Holonymy

- Meronymy

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Dawkins, Richard (1976). Bateson, Paul Patrick Gordon; Hinde, Robert A. (eds.). Hierarchical organization: a candidate principle for ethology. Growing points in ethology: based on a conference sponsored by St. John’s College and King’s College, Cambridge. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–54. ISBN 0-521-29086-4.

- ^ a b Simon, Herbert A. (12 December 1962). «The Architecture of Complexity». Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society. 106 (6): 467–482. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.110.961. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 985254.(registration required)

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Hierarchy

- ^ «hierarchy». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ ἱεράρχης,

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library - ^ ἱερεύς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἀρχή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Douglas Lemke (2002). Regions of War and Peace. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. p. 49.

- ^ a b Lehmann, Fritz (1996). Eklund, Peter G.; Ellis, Gerard; Mann, Graham (eds.). Big Posets of Participatings and Thematic Roles. Conceptual structures: knowledge representation as interlingua—4th International Conference on Conceptual Structures, ICCS ’96, Sydney, Australia, August 19–22, 1996—proceedings. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 115. Germany: Springer. pp. 50–74. ISBN 3-540-61534-2.

- ^ a b Lane, David (2006). «Hierarchy, Complexity, Society». In Pumain, Denise (ed.). Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 81–120. ISBN 978-1-4020-4126-6.

- ^ Linnaei, Carl von (1959). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Stockholm: Impensis Direct. ISBN 0-665-53008-0. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ^ Corballis, Michael (2011). The Recursive Mind. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691145471.

- ^ Kopisch, Manfred; Günther, Andreas (1992). «Configuration of a passenger aircraft cabin based on conceptual hierarchy, constraints and flexible control». In Belli, Fevzi (ed.). Industrial and Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Expert Systems. Industrial and engineering applications of artificial intelligence and expert systems: 5th international conference, IEA/AIE-92, Paderborn, Germany, June 9–12, 1992 : proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Series. Vol. 602. Springer. pp. 424–427. doi:10.1007/BFb0024994. ISBN 3-540-55601-X. ISSN 0302-9743.

- ^ «Compositional hierarchy». WebSphere Transformation Extender Design Studio. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2009.