Problem solving is the process of achieving a goal by overcoming obstacles, a frequent part of most activities. Problems in need of solutions range from simple personal tasks (e.g. how to turn on an appliance) to complex issues in business and technical fields. The former is an example of simple problem solving (SPS) addressing one issue, whereas the latter is complex problem solving (CPS) with multiple interrelated obstacles.[1] Another classification is into well-defined problems with specific obstacles and goals, and ill-defined problems in which the current situation is troublesome but it is not clear what kind of resolution to aim for.[2] Similarly, one may distinguish formal or fact-based problems requiring psychometric intelligence, versus socio-emotional problems which depend on the changeable emotions of individuals or groups, such as tactful behavior, fashion, or gift choices.[3]

Solutions require sufficient resources and knowledge to attain the goal. Professionals such as lawyers, doctors, and consultants are largely problem solvers for issues which require technical skills and knowledge beyond general competence. Many businesses have found profitable markets by recognizing a problem and creating a solution: the more widespread and inconvenient the problem, the greater the opportunity to develop a scalable solution.

There are many specialized problem-solving techniques and methods in fields such as engineering, business, medicine, mathematics, computer science, philosophy, and social organization. The mental techniques to identify, analyze, and solve problems are studied in psychology and cognitive sciences. Additionally, the mental obstacles preventing people from finding solutions is a widely researched topic: problem solving impediments include confirmation bias, mental set, and functional fixedness.

DefinitionEdit

The term problem solving has a slightly different meaning depending on the discipline. For instance, it is a mental process in psychology and a computerized process in computer science. There are two different types of problems: ill-defined and well-defined; different approaches are used for each. Well-defined problems have specific end goals and clearly expected solutions, while ill-defined problems do not. Well-defined problems allow for more initial planning than ill-defined problems.[2] Solving problems sometimes involves dealing with pragmatics, the way that context contributes to meaning, and semantics, the interpretation of the problem. The ability to understand what the end goal of the problem is, and what rules could be applied represents the key to solving the problem. Sometimes the problem requires abstract thinking or coming up with a creative solution.

PsychologyEdit

Problem solving in psychology refers to the process of finding solutions to problems encountered in life.[4] Solutions to these problems are usually situation or context-specific. The process starts with problem finding and problem shaping, where the problem is discovered and simplified. The next step is to generate possible solutions and evaluate them. Finally a solution is selected to be implemented and verified. Problems have an end goal to be reached and how you get there depends upon problem orientation (problem-solving coping style and skills) and systematic analysis.[5] Mental health professionals study the human problem solving processes using methods such as introspection, behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experiment. Social psychologists look into the person-environment relationship aspect of the problem and independent and interdependent problem-solving methods.[6] Problem solving has been defined as a higher-order cognitive process and intellectual function that requires the modulation and control of more routine or fundamental skills.[7]

Problem solving has two major domains: mathematical problem solving and personal problem solving. Both are seen in terms of some difficulty or barrier that is encountered.[8] Empirical research shows many different strategies and factors influence everyday problem solving.[9][10][11] Rehabilitation psychologists studying individuals with frontal lobe injuries have found that deficits in emotional control and reasoning can be re-mediated with effective rehabilitation and could improve the capacity of injured persons to resolve everyday problems.[12] Interpersonal everyday problem solving is dependent upon the individual personal motivational and contextual components. One such component is the emotional valence of «real-world» problems and it can either impede or aid problem-solving performance. Researchers have focused on the role of emotions in problem solving,[13][14] demonstrating that poor emotional control can disrupt focus on the target task and impede problem resolution and likely lead to negative outcomes such as fatigue, depression, and inertia.[15] In conceptualization, human problem solving consists of two related processes: problem orientation and the motivational/attitudinal/affective approach to problematic situations and problem-solving skills. Studies conclude people’s strategies cohere with their goals[16] and stem from the natural process of comparing oneself with others.

Cognitive sciencesEdit

Among the first experimental psychologists to study problem solving were the Gestaltists in Germany, e.g., Karl Duncker in The Psychology of Productive Thinking (1935).[17] Perhaps best known is the work of Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon.[18]

Experiments the 1960s and early 1970s asked participants to solve relatively simple, well-defined, but not previously seen laboratory tasks.[19][20] These simple problems, such as the Tower of Hanoi, admitted optimal solutions which could be found quickly, allowing observation of the full problem-solving process. Researchers assumed that these model problems would elicit the characteristic cognitive processes by which more complex «real world» problems are solved.

An outstanding problem solving technique found by this research is the principle of decomposition.[21]

Computer scienceEdit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2018)

Much of computer science and artificial intelligence involves designing automatic systems to solve a specified type of problem: to accept input data and calculate a correct or adequate response, reasonably quickly. Algorithms are recipes or instructions that direct such systems, written into computer programs.

Steps for designing such systems include problem determination, heuristics, root cause analysis, de-duplication, analysis, diagnosis, and repair. Analytic techniques include linear and nonlinear programming, queuing systems, and simulation.[22] A large, perennial obstacle is to find and fix errors in computer programs: debugging.

LogicEdit

Formal logic is concerned with such issues as validity, truth, inference, argumentation and proof. In a problem-solving context, it can be used to formally represent a problem as a theorem to be proved, and to represent the knowledge needed to solve the problem as the premises to be used in a proof that the problem has a solution. The use of computers to prove mathematical theorems using formal logic emerged as the field of automated theorem proving in the 1950s. It included the use of heuristic methods designed to simulate human problem solving, as in the Logic Theory Machine, developed by Allen Newell, Herbert A. Simon and J. C. Shaw, as well as algorithmic methods such as the resolution principle developed by John Alan Robinson.

In addition to its use for finding proofs of mathematical theorems, automated theorem-proving has also been used for program verification in computer science. However, already in 1958, John McCarthy proposed the advice taker, to represent information in formal logic and to derive answers to questions using automated theorem-proving. An important step in this direction was made by Cordell Green in 1969, using a resolution theorem prover for question-answering and for such other applications in artificial intelligence as robot planning.

The resolution theorem-prover used by Cordell Green bore little resemblance to human problem solving methods. In response to criticism of his approach, emanating from researchers at MIT, Robert Kowalski developed logic programming and SLD resolution,[23] which solves problems by problem decomposition. He has advocated logic for both computer and human problem solving[24] and computational logic to improve human thinking[25]

EngineeringEdit

Problem solving is used when products or processes fail, so corrective action can be taken to prevent further failures. It can also be applied to a product or process prior to an actual failure event—when a potential problem can be predicted and analyzed, and mitigation applied to prevent the problem. Techniques such as failure mode and effects analysis can proactively reduce the likelihood of problems.

Forensic engineering is an important technique of failure analysis that involves tracing product defects and flaws. Corrective action can then be taken to prevent further failures.

Reverse engineering attempts to discover the original problem-solving logic used in developing a product by taking it apart.[26]

Military scienceEdit

In military science, problem solving is linked to the concept of «end-states», the condition or situation which is the aim of the strategy.[27]: xiii, E-2 Ability to solve problems is important at any military rank, but is essential at the command and control level, where it results from deep qualitative and quantitative understanding of possible scenarios.[clarification needed] Effectiveness is evaluation of results, whether the goal was accomplished.[27]: IV-24 Planning is the process of determining how to achieve the goal.[27]: IV-1

ProcessesEdit

Some models of problem solving involve identifying a goal and then a sequence of subgoals towards achieving this goal. Andersson, who introduced the ACT-R model of cognition, modelled this collection of goals and subgoals as a goal stack, where the mind contains a stack of goals and subgoals to be completed with a single task being carried out at any time.[28]: 51

It has been observed that knowledge of how to solve one problem can be applied to another problem, in a process known as transfer.[28]: 56

Problem-solving strategiesEdit

Problem-solving strategies are steps to overcoming the obstacles to achieving a goal, the «problem-solving cycle».[29]

Common steps in this cycle include recognizing the problem, defining it, developing a strategy to fix it, organizing knowledge and resources available, monitoring progress, and evaluating the effectiveness of the solution. Once a solution is achieved, another problem usually arises, and the cycle starts again.

Insight is the sudden aha! solution to a problem, the birth of a new idea to simplify a complex situation. Solutions found through insight are often more incisive than those from step-by-step analysis. A quick solution process requires insight to select productive moves at different stages of the problem-solving cycle. Unlike Newell and Simon’s formal definition of a move problem, there is no consensus definition of an insight problem.[30][31][32]

Some problem-solving strategies include:[33]

- Abstraction: solving the problem in a tractable model system to gain insight into the real system

- Analogy: adapting the solution to a previous problem which has similar features or mechanisms

- Brainstorming: (especially among groups of people) suggesting a large number of solutions or ideas and combining and developing them until an optimum solution is found

- Critical thinking

- Divide and conquer: breaking down a large, complex problem into smaller, solvable problems

- Hypothesis testing: assuming a possible explanation to the problem and trying to prove (or, in some contexts, disprove) the assumption

- Lateral thinking: approaching solutions indirectly and creatively

- Means-ends analysis: choosing an action at each step to move closer to the goal

- Morphological analysis: assessing the output and interactions of an entire system

- Proof of impossibility: try to prove that the problem cannot be solved. The point where the proof fails will be the starting point for solving it

- Reduction: transforming the problem into another problem for which solutions exist

- Research: employing existing ideas or adapting existing solutions to similar problems

- Root cause analysis: identifying the cause of a problem

- Trial-and-error: testing possible solutions until the right one is found

- Help-seeking

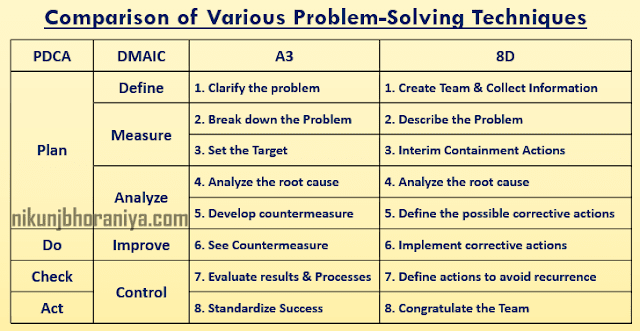

Problem-solving methodsEdit

- Eight Disciplines Problem Solving

- GROW model

- How to Solve It

- Lateral thinking

- OODA loop (observe, orient, decide, and act)

- PDCA (plan–do–check–act)

- Root cause analysis

- RPR problem diagnosis (rapid problem resolution)

- TRIZ (Russian: теория решения изобретательских задач, romanized: teoriya resheniya izobretatelskikh zadatch, lit. ‘theory of inventive problem solving’)

- A3 problem solving

- System dynamics

- Hive mind

- Design Thinking

- Help-seeking

Common barriersEdit

Common barriers to problem solving are mental constructs that impede an efficient search for solutions. Five of the most common identified by researchers are: confirmation bias, mental set, functional fixedness, unnecessary constraints, and irrelevant information.

Confirmation biasEdit

Confirmation bias is an unintentional tendency to collect and use data which favors preconceived notions. Such notions may be incidental rather than motivated by important personal beliefs: the desire to be right may be sufficient motivation.[34] Research has found that scientific and technical professionals also experience confirmation bias.

Andreas Hergovich, Reinhard Schott, and Christoph Burger’s experiment conducted online, for instance, suggested that professionals within the field of psychological research are likely to view scientific studies that agree with their preconceived notions more favorably than clashing studies.[35] According to Raymond Nickerson, one can see the consequences of confirmation bias in real-life situations, which range in severity from inefficient government policies to genocide. Nickerson argued that those who killed people accused of witchcraft demonstrated confirmation bias with motivation. Researcher Michael Allen found evidence for confirmation bias with motivation in school children who worked to manipulate their science experiments to produce favorable results.[36]

However, confirmation bias does not necessarily require motivation. In 1960, Peter Cathcart Wason conducted an experiment in which participants first viewed three numbers and then created a hypothesis that proposed a rule that could have been used to create that triplet of numbers. When testing their hypotheses, participants tended to only create additional triplets of numbers that would confirm their hypotheses, and tended not to create triplets that would negate or disprove their hypotheses.[37]

Mental setEdit

Mental set is the inclination to re-use a previously successful solution, rather than search for new and better solutions. It is a reliance on habit.

It was first articulated by Abraham Luchins in the 1940s with his well-known water jug experiments.[38] Participants were asked to fill one jug with a specific amount of water using other jugs with different maximum capacities. After Luchins gave a set of jug problems that could all be solved by a single technique, he then introduced a problem that could be solved by the same technique, but also by a novel and simpler method. His participants tended to use the accustomed technique, oblivious of the simpler alternative.[39] This was again demonstrated in Norman Maier’s 1931 experiment, which challenged participants to solve a problem by using a familiar tool (pliers) in an unconventional manner. Participants were often unable to view the object in a way that strayed from its typical use, a type of mental set known as functional fixedness (see the following section).

Rigidly clinging to a mental set is called fixation, which can deepen to an obsession or preoccupation with attempted strategies that are repeatedly unsuccessful.[40] In the late 1990s, researcher Jennifer Wiley found that professional expertise in a field can create a mental set, perhaps leading to fixation.[40]

Groupthink, where each individual takes on the mindset of the rest of the group, can produce and exacerbate mental set.[41] Social pressure leads to everybody thinking the same thing and reaching the same conclusions.

Functional fixednessEdit

Functional fixedness is the tendency to view an object as having only one function, unable to conceive of any novel use, as in the Maier pliers experiment above. Functional fixedness is a specific form of mental set, and is one of the most common forms of cognitive bias in daily life.

Tim German and Clark Barrett describe this barrier: «subjects become ‘fixed’ on the design function of the objects, and problem solving suffers relative to control conditions in which the object’s function is not demonstrated.»[42] Their research found that young children’s limited knowledge of an object’s intended function reduces this barrier[43] Research has also discovered functional fixedness in many educational instances, as an obstacle to understanding. Furio, Calatayud, Baracenas, and Padilla stated: «… functional fixedness may be found in learning concepts as well as in solving chemistry problems.»[44]

As an example, imagine a man wants to kill a bug in is house, but the only thing at hand is a can of air freshener. He may start searching for something to kill the bug instead of squashing it with the can, thinking only of its main function of deodorizing.

There are several hypotheses in regards to how functional fixedness relates to problem solving.[45] It may waste time, delaying or entirely preventing the correct use of a tool.

Unnecessary constraintsEdit

Unnecessary constraints are arbitrary boundaries imposed unconsciously on the task at hand, which foreclose a productive avenue of solution. The solver may become fixated on only one type of solution, as if it were an inevitable requirement of the problem. Typically, this combines with mental set, clinging to a previously successful method.[46]

Visual problems can also produce mentally invented constraints.[47] A famous example is the dot problem: nine dots arranged in a three-by-three grid pattern must be connected by drawing four straight line segments, without lifting pen from paper or backtracking along a line. The subject typically assumes the pen must stay within the outer square of dots, but the solution requires lines continuing beyond this frame, and researchers have found a 0% solution rate within a brief allotted time.[48]

This problem has produced the expression «think outside the box».[49] Such problems are typically solved via a sudden insight which leaps over the mental barriers, often after long toil against them.[50] This can be difficult depending on how the subject has structured the problem in their mind, how they draw on past experiences, and how well they juggle this information in their working memory. In the example, envisioning the dots connected outside the framing square requires visualizing an unconventional arrangement, a strain on working memory.[49]

Irrelevant informationEdit

Irrelevant information is a specification or data presented in a problem that is unrelated to the solution.[46] If the solver assumes that all information presented needs to be used, this often derails the problem solving process, making relatively simple problems much harder.[51]

For example: «Fifteen percent of the people in Topeka have unlisted telephone numbers. You select 200 names at random from the Topeka phone book. How many of these people have unlisted phone numbers?»[52] The «obvious» answer is 15%, but in fact none of the unlisted people would be listed among the 200. This kind of «trick question» is often used in aptitude tests or cognitive evaluations.[53] Though not inherently difficult, they require independent thinking that is not necessarily common. Mathematical word problems often include irrelevant qualitative or numerical information as an extra challenge.

Avoiding barriers by changing problem representationEdit

The disruption caused by the above cognitive biases can depend on how the information is represented:[53] visually, verbally, or mathematically. A classic example is the Buddhist monk problem:

-

- A Buddhist monk begins at dawn one day walking up a mountain, reaches the top at sunset, meditates at the top for several days until one dawn when he begins to walk back to the foot of the mountain, which he reaches at sunset. Making no assumptions about his starting or stopping or about his pace during the trips, prove that there is a place on the path which he occupies at the same hour of the day on the two separate journeys.

The problem cannot be addressed in a verbal context, trying to describe the monk’s progress on each day. It becomes much easier when the paragraph is represented mathematically by a function: one visualizes a graph whose horizontal axis is time of day, and whose vertical axis shows the monk’s position (or altitude) on the path at each time. Superimposing the two journey curves, which traverse opposite diagonals of a rectangle, one sees they must cross each other somewhere. The visual representation by graphing has resolved the difficulty.

Similar strategies can often improve problem solving on tests.[46][54]

Other barriers for individualsEdit

Individual humans engaged in problem-solving tend to overlook subtractive changes, including those that are critical elements of efficient solutions. This tendency to solve by first, only or mostly creating or adding elements, rather than by subtracting elements or processes is shown to intensify with higher cognitive loads such as information overload.[55][56]

Dreaming: problem-solving without waking consciousnessEdit

Problem solving can also occur without waking consciousness. There are many reports of scientists and engineers who solved problems in their dreams. Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine, figured out the structure of the bobbin from a dream.[57]

The chemist August Kekulé was considering how benzene arranged its six carbon and hydrogen atoms. Thinking about the problem, he dozed off, and dreamt of dancing atoms that fell into a snakelike pattern, which led him to discover the benzene ring. As Kekulé wrote in his diary,

One of the snakes seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.[58]

There also are empirical studies of how people can think consciously about a problem before going to sleep, and then solve the problem with a dream image. Dream researcher William C. Dement told his undergraduate class of 500 students that he wanted them to think about an infinite series, whose first elements were OTTFF, to see if they could deduce the principle behind it and to say what the next elements of the series would be.[59] He asked them to think about this problem every night for 15 minutes before going to sleep and to write down any dreams that they then had. They were instructed to think about the problem again for 15 minutes when they awakened in the morning.

The sequence OTTFF is the first letters of the numbers: one, two, three, four, five. The next five elements of the series are SSENT (six, seven, eight, nine, ten). Some of the students solved the puzzle by reflecting on their dreams. One example was a student who reported the following dream:[59]

I was standing in an art gallery, looking at the paintings on the wall. As I walked down the hall, I began to count the paintings: one, two, three, four, five. As I came to the sixth and seventh, the paintings had been ripped from their frames. I stared at the empty frames with a peculiar feeling that some mystery was about to be solved. Suddenly I realized that the sixth and seventh spaces were the solution to the problem!

With more than 500 undergraduate students, 87 dreams were judged to be related to the problems students were assigned (53 directly related and 34 indirectly related). Yet of the people who had dreams that apparently solved the problem, only seven were actually able to consciously know the solution. The rest (46 out of 53) thought they did not know the solution.

Mark Blechner conducted this experiment and obtained results similar to Dement’s.[60] He found that while trying to solve the problem, people had dreams in which the solution appeared to be obvious from the dream, but it was rare for the dreamers to realize how their dreams had solved the puzzle. Coaxing or hints did not get them to realize it, although once they heard the solution, they recognized how their dream had solved it. For example, one person in that OTTFF experiment dreamed:[60]

There is a big clock. You can see the movement. The big hand of the clock was on the number six. You could see it move up, number by number, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve. The dream focused on the small parts of the machinery. You could see the gears inside.

In the dream, the person counted out the next elements of the series – six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve – yet he did not realize that this was the solution of the problem. His sleeping mindbrain solved the problem, but his waking mindbrain was not aware how.

Albert Einstein believed that much problem solving goes on unconsciously, and the person must then figure out and formulate consciously what the mindbrain has already solved. He believed this was his process in formulating the theory of relativity: «The creator of the problem possesses the solution.»[61] Einstein said that he did his problem-solving without words, mostly in images. «The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be ‘voluntarily’ reproduced and combined.»[62]

Cognitive sciences: two schoolsEdit

In cognitive sciences, researchers’ realization that problem-solving processes differ across knowledge domains and across levels of expertise[63] and that, consequently, findings obtained in the laboratory cannot necessarily generalize to problem-solving situations outside the laboratory, has led to an emphasis on real-world problem solving since the 1990s. This emphasis has been expressed quite differently in North America and Europe, however. Whereas North American research has typically concentrated on studying problem solving in separate, natural knowledge domains, much of the European research has focused on novel, complex problems, and has been performed with computerized scenarios.[64]

EuropeEdit

In Europe, two main approaches have surfaced, one initiated by Donald Broadbent[65][66] in the United Kingdom and the other one by Dietrich Dörner[67][68][69] in Germany. The two approaches share an emphasis on relatively complex, semantically rich, computerized laboratory tasks, constructed to resemble real-life problems. The approaches differ somewhat in their theoretical goals and methodology, however. The tradition initiated by Broadbent emphasizes the distinction between cognitive problem-solving processes that operate under awareness versus outside of awareness, and typically employs mathematically well-defined computerized systems. The tradition initiated by Dörner, on the other hand, has an interest in the interplay of the cognitive, motivational, and social components of problem solving, and utilizes very complex computerized scenarios that contain up to 2,000 highly interconnected variables.[70][71]

North AmericaEdit

In North America, initiated by the work of Herbert A. Simon on «learning by doing» in semantically rich domains,[72][73] researchers began to investigate problem solving separately in different natural knowledge domains – such as physics, writing, or chess playing – thus relinquishing their attempts to extract a global theory of problem solving.[74] Instead, these researchers have frequently focused on the development of problem solving within a certain domain, that is on the development of expertise.[75][76][77]

Areas that have attracted rather intensive attention in North America include:

- Reading[78]

- Writing[79]

- Calculation[80]

- Political decision making[81]

- Managerial problem solving[82]

- Lawyers’ reasoning[83]

- Mechanical problem solving[84]

- Problem solving in electronics[85]

- Computer skills[86]

- Game playing[87]

- Personal problem solving[88]

- Mathematical problem solving[89][90]

- Social problem solving[13][14]

- Problem solving for innovations and inventions: TRIZ[91]

Characteristics of complex problemsEdit

Complex problem solving (CPS) is distinguishable from simple problem solving (SPS). When dealing with SPS there is a singular and simple obstacle in the way. But CPS comprises one or more obstacles at a time. In a real-life example, a surgeon at work has far more complex problems than an individual deciding what shoes to wear. As elucidated by Dietrich Dörner, and later expanded upon by Joachim Funke, complex problems have some typical characteristics as follows:[1]

- Complexity (large numbers of items, interrelations and decisions)

- enumerability

- heterogeneity

- connectivity (hierarchy relation, communication relation, allocation relation)

- Dynamics (time considerations)

- temporal constraints

- temporal sensitivity

- phase effects

- dynamic unpredictability

- Intransparency (lack of clarity of the situation)

- commencement opacity

- continuation opacity

- Polytely (multiple goals)[92]

- inexpressivenes

- opposition

- transience

Collective problem solvingEdit

Problem solving is applied on many different levels − from the individual to the civilizational. Collective problem solving refers to problem solving performed collectively.

Social issues and global issues can typically only be solved collectively.

It has been noted that the complexity of contemporary problems has exceeded the cognitive capacity of any individual and requires different but complementary expertise and collective problem solving ability.[93]

Collective intelligence is shared or group intelligence that emerges from the collaboration, collective efforts, and competition of many individuals.

Collaborative problem solving is about people working together face-to-face or in online workspaces with a focus on solving real world problems. These groups are made up of members that share a common concern, a similar passion, and/or a commitment to their work. Members are willing to ask questions, wonder, and try to understand common issues. They share expertise, experiences, tools, and methods.[94] These groups can be assigned by instructors, or may be student regulated based on the individual student needs. The groups, or group members, may be fluid based on need, or may only occur temporarily to finish an assigned task. They may also be more permanent in nature depending on the needs of the learners. All members of the group must have some input into the decision-making process and have a role in the learning process. Group members are responsible for the thinking, teaching, and monitoring of all members in the group. Group work must be coordinated among its members so that each member makes an equal contribution to the whole work. Group members must identify and build on their individual strengths so that everyone can make a significant contribution to the task.[95] Collaborative groups require joint intellectual efforts between the members and involve social interactions to solve problems together. The knowledge shared during these interactions is acquired during communication, negotiation, and production of materials.[96] Members actively seek information from others by asking questions. The capacity to use questions to acquire new information increases understanding and the ability to solve problems.[97] Collaborative group work has the ability to promote critical thinking skills, problem solving skills, social skills, and self-esteem. By using collaboration and communication, members often learn from one another and construct meaningful knowledge that often leads to better learning outcomes than individual work.[98]

In a 1962 research report, Douglas Engelbart linked collective intelligence to organizational effectiveness, and predicted that pro-actively ‘augmenting human intellect’ would yield a multiplier effect in group problem solving: «Three people working together in this augmented mode [would] seem to be more than three times as effective in solving a complex problem as is one augmented person working alone».[99]

Henry Jenkins, a key theorist of new media and media convergence draws on the theory that collective intelligence can be attributed to media convergence and participatory culture.[100] He criticizes contemporary education for failing to incorporate online trends of collective problem solving into the classroom, stating «whereas a collective intelligence community encourages ownership of work as a group, schools grade individuals». Jenkins argues that interaction within a knowledge community builds vital skills for young people, and teamwork through collective intelligence communities contributes to the development of such skills.[101]

Collective impact is the commitment of a group of actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem, using a structured form of collaboration.

After World War II the UN, the Bretton Woods organization and the WTO were created; collective problem solving on the international level crystallized around these three types of organizations from the 1980s onward. As these global institutions remain state-like or state-centric it has been called unsurprising that these continue state-like or state-centric approaches to collective problem-solving rather than alternative ones.[102]

Crowdsourcing is a process of accumulating the ideas, thoughts or information from many independent participants, with aim to find the best solution for a given challenge. Modern information technologies allow for massive number of subjects to be involved as well as systems of managing these suggestions that provide good results.[103][104] With the Internet a new capacity for collective, including planetary-scale, problem solving was created.[105]

See alsoEdit

- Actuarial science

- Analytical skill

- Creative problem-solving

- Collective intelligence

- Community of practice

- Coworking

- Crowdsolving

- Divergent thinking

- Grey problem

- Innovation

- Instrumentalism

- Problem statement

- Problem structuring methods

- Psychedelics in problem-solving experiment

- Structural fix

- Subgoal labeling

- Troubleshooting

- Wicked problem

NotesEdit

- ^ a b Frensch, Peter A.; Funke, Joachim, eds. (2014-04-04). Complex Problem Solving. doi:10.4324/9781315806723. ISBN 9781315806723.

- ^ a b Schacter, D.L. et al. (2009). Psychology, Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. pp. 376

- ^ Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). «Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective». Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00469.x. S2CID 145645352.

- ^ Jerrold R. Brandell (1997). Theory and Practice in Clinical Social Work. Simon and Schuster. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-684-82765-0.

- ^ What is a problem? in S. Ian Robertson, Problem solving, Psychology Press, 2001.

- ^ Rubin, M.; Watt, S. E.; Ramelli, M. (2012). «Immigrants’ social integration as a function of approach-avoidance orientation and problem-solving style». International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 36 (4): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.12.009. hdl:1959.13/931119.

- ^ Goldstein F. C.; Levin H. S. (1987). «Disorders of reasoning and problem-solving ability». In M. Meier; A. Benton; L. Diller (eds.). Neuropsychological rehabilitation. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- ^ Bernd Zimmermann, On mathematical problem solving processes and history of mathematics, University of Jena.

- ^ Vallacher, Robin; M. Wegner, Daniel (2012). Action Identification Theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. pp. 327–348. doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n17. ISBN 9780857029607.

- ^ Margrett, J. A; Marsiske, M (2002). «Gender differences in older adults’ everyday cognitive collaboration». International Journal of Behavioral Development. 26 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1080/01650250143000319. PMC 2909137. PMID 20657668.

- ^ Antonucci, T. C; Ajrouch, K. J; Birditt, K. S (2013). «The Convoy Model: Explaining Social Relations From a Multidisciplinary Perspective». The Gerontologist. 54 (1): 82–92. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt118. PMC 3894851. PMID 24142914.

- ^ Rath, Joseph F.; Simon, Dvorah; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Sherr, Rose Lynn; Diller, Leonard (September 2003). «Group treatment of problem‐solving deficits in outpatients with traumatic brain injury: A randomised outcome study». Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 13 (4): 461–488. doi:10.1080/09602010343000039. S2CID 143165070.

- ^ a b D’Zurilla, T. J.; Goldfried, M. R. (1971). «Problem solving and behavior modification». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 78 (1): 107–126. doi:10.1037/h0031360. PMID 4938262.

- ^ a b D’Zurilla, T. J.; Nezu, A. M. (1982). «Social problem solving in adults». In P. C. Kendall (ed.). Advances in cognitive-behavioral research and therapy. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press. pp. 201–274.

- ^ RATH, J (August 2004). «The construct of problem solving in higher level neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation*1». Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 19 (5): 613–635. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2003.08.006. PMID 15271407.

- ^ Hoppmann, Christiane A.; Blanchard-Fields, Fredda (November 2010). «Goals and everyday problem solving: Manipulating goal preferences in young and older adults». Developmental Psychology. 46 (6): 1433–1443. doi:10.1037/a0020676. PMID 20873926.

- ^ Duncker, K. (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- ^ Newell, A.; Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ For example:

- X-ray problem by Duncker, K. (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- Disk problem, later known as Tower of Hanoi by Ewert, P. H.; Lambert, J. F. (1932). «Part II: The Effect of Verbal Instructions upon the Formation of a Concept». The Journal of General Psychology. Informa UK Limited. 6 (2): 400–413. doi:10.1080/00221309.1932.9711880. ISSN 0022-1309.

- ^ Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition (Second ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong, William B. Denniston Jr. and Matt M. Gordon (1975). «The Use of the Decomposition Principle in Making Judgments» (PDF). Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 14 (2): 257–263. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(75)90028-8. S2CID 122659209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-20.

- ^ Malakooti, Behnam (2013). Operations and Production Systems with Multiple Objectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-58537-5.

- ^ Kowalski, R. Predicate Logic as a Programming Language Memo 70, Department of Artificial Intelligence, Edinburgh University. 1973. Also in Proceedings IFIP Congress, Stockholm, North Holland Publishing Co., 1974, pp. 569–574.

- ^ Kowalski, R., Logic for Problem Solving, North Holland, Elsevier, 1979

- ^ Kowalski, R., Computational Logic and Human Thinking: How to be Artificially Intelligent, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- ^ «Einstein’s Secret to Amazing Problem Solving (and 10 Specific Ways You Can Use It)». litemind.com. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ^ a b c «Commander’s Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy» (PDF). United States Joint Forces Command, Joint Warfighting Center, Suffolk, VA. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b Robertson, S. Ian (2017). Problem solving: perspectives from cognition and neuroscience (2nd ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-317-49601-4. OCLC 962750529.

- ^ Bransford, J. D.; Stein, B. S (1993). The ideal problem solver: A guide for improving thinking, learning, and creativity (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman.

- ^ Ash, Ivan K.; Jee, Benjamin D.; Wiley, Jennifer (2012-05-11). «Investigating Insight as Sudden Learning». The Journal of Problem Solving. 4 (2). doi:10.7771/1932-6246.1123. ISSN 1932-6246.

- ^ Chronicle, Edward P.; MacGregor, James N.; Ormerod, Thomas C. (2004). «What Makes an Insight Problem? The Roles of Heuristics, Goal Conception, and Solution Recoding in Knowledge-Lean Problems». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 30 (1): 14–27. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.14. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 14736293. S2CID 15631498.

- ^ Chu, Yun; MacGregor, James N. (2011-02-07). «Human Performance on Insight Problem Solving: A Review». The Journal of Problem Solving. 3 (2). doi:10.7771/1932-6246.1094. ISSN 1932-6246.

- ^ Wang, Y.; Chiew, V. (2010). «On the cognitive process of human problem solving» (PDF). Cognitive Systems Research. Elsevier BV. 11 (1): 81–92. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2008.08.003. ISSN 1389-0417. S2CID 16238486.

- ^ Nickerson, R. S. (1998). «Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises». Review of General Psychology. 2 (2): 176. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175. S2CID 8508954.

- ^ Hergovich, Schott; Burger (2010). «Biased evaluation of abstracts depending on topic and conclusion: Further evidence of a confirmation bias within scientific psychology». Current Psychology. 29 (3): 188–209. doi:10.1007/s12144-010-9087-5. S2CID 145497196.

- ^ Allen (2011). «Theory-led confirmation bias and experimental persona». Research in Science & Technological Education. 29 (1): 107–127. Bibcode:2011RSTEd..29..107A. doi:10.1080/02635143.2010.539973. S2CID 145706148.

- ^ Wason, P. C. (1960). «On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task». Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 12 (3): 129–140. doi:10.1080/17470216008416717. S2CID 19237642.

- ^ Luchins, A. S. (1942). Mechanization in problem solving: The effect of Einstellung. Psychological Monographs, 54 (Whole No. 248).

- ^ Öllinger, Michael; Jones, Gary; Knoblich, Günther (2008). «Investigating the Effect of Mental Set on Insight Problem Solving» (PDF). Experimental Psychology. Hogrefe Publishing Group. 55 (4): 269–282. doi:10.1027/1618-3169.55.4.269. ISSN 1618-3169. PMID 18683624.

- ^ a b Wiley, J (1998). «Expertise as mental set: The effects of domain knowledge in creative problem solving». Memory & Cognition. 24 (4): 716–730. doi:10.3758/bf03211392. PMID 9701964.

- ^ Cottam, Martha L., Dietz-Uhler, Beth, Mastors, Elena, Preston, & Thomas. (2010). Introduction to Political Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press.

- ^ German, Tim P.; Barrett, H. Clark (2005). «Functional Fixedness in a Technologically Sparse Culture». Psychological Science. SAGE Publications. 16 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00771.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 15660843. S2CID 1833823.

- ^ German, Tim P.; Defeyter, Margaret A. (2000). «Immunity to functional fixedness in young children». Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 7 (4): 707–712. doi:10.3758/BF03213010. PMID 11206213.

- ^ Furio, C.; Calatayud, M. L.; Baracenas, S; Padilla, O (2000). «Functional fixedness and functional reduction as common sense reasonings in chemical equilibrium and in geometry and polarity of molecules. Valencia, Spain». Science Education. 84 (5): 545–565. doi:10.1002/1098-237X(200009)84:5<545::AID-SCE1>3.0.CO;2-1.

- ^ Adamson, Robert E (1952). «Functional fixedness as related to problem solving: A repetition of three experiments. Stanford University. California». Journal of Experimental Psychology. 44 (4): 1952. doi:10.1037/h0062487.

- ^ a b c Kellogg, R. T. (2003). Cognitive psychology (2nd ed.). California: Sage Publications, Inc.

- ^ Meloy, J. R. (1998). The Psychology of Stalking, Clinical and Forensic Perspectives (2nd ed.). London, England: Academic Press.

- ^ MacGregor, J.N.; Ormerod, T.C.; Chronicle, E.P. (2001). «Information-processing and insight: A process model of performance on the nine-dot and related problems». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 27 (1): 176–201. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.27.1.176. PMID 11204097.

- ^ a b Weiten, Wayne. (2011). Psychology: themes and variations (8th ed.). California: Wadsworth.

- ^ Novick, L. R., & Bassok, M. (2005). Problem solving. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (Ch. 14, pp. 321-349). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Walinga, Jennifer (2010). «From walls to windows: Using barriers as pathways to insightful solutions». The Journal of Creative Behavior. 44 (3): 143–167. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2010.tb01331.x.

- ^ Weiten, Wayne. (2011). Psychology: themes and variations (8th ed.) California: Wadsworth.

- ^ a b Walinga, Jennifer, Cunningham, J. Barton, & MacGregor, James N. (2011). Training insight problem solving through focus on barriers and assumptions. The Journal of Creative Behavior.

- ^ Vlamings, Petra H. J. M.; Hare, Brian; Call, Joseph (2009). «Reaching around barriers: The performance of great apes and 3-5-year-old children». Animal Cognition. 13 (2): 273–285. doi:10.1007/s10071-009-0265-5. PMC 2822225. PMID 19653018.

- ^ «People add by default even when subtraction makes more sense». Science News. 7 April 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Adams, Gabrielle S.; Converse, Benjamin A.; Hales, Andrew H.; Klotz, Leidy E. (April 2021). «People systematically overlook subtractive changes». Nature. 592 (7853): 258–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..258A. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03380-y. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33828317. S2CID 233185662. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Kaempffert, W. (1924) A Popular History of American Invention. New York: Scribners.

- ^ Kekulé, A (1890). «Benzolfest-Rede». Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 23: 1302–1311. Trans. Benfey, O. (1958). «Kekulé and the birth of the structural theory of organic chemistry in 1858». Journal of Chemical Education. 35: 21–23. doi:10.1021/ed035p21.

- ^ a b Dement, W.C. (1972). Some Must Watch While Some Just Sleep. New York: Freeman.

- ^ a b Blechner, M. J. (2018) The Mindbrain and Dreams: An Exploration of Dreaming, Thinking, and Artistic Creation. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Fromm, Erika O (1998). «Lost and found half a century later: Letters by Freud and Einstein». American Psychologist. 53 (11): 1195–1198. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.53.11.1195.

- ^ Einstein, A. (1994) Ideas and Opinions. New York: Modern Library.

- ^ e.g. Sternberg, R. J. (1995). Conceptions of expertise in complex problem solving: A comparison of alternative conceptions. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 295-321). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ For an overview, see Funke, J. (1991). «Solving complex problems: Human identification and control of complex systems». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 185–222. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Broadbent, D. E. (1977). Levels, hierarchies, and the locus of control. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29, 181-201.

- ^ See Berry, D. C., & Broadbent, D. E. (1995). Implicit learning in the control of complex systems: A reconsideration of some of the earlier claims. In P.A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 131-150). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Dörner, D. (1975). Wie Menschen eine Welt verbessern wollten [How people wanted to improve the world]. Bild der Wissenschaft, 12, 48-53.

- ^ Dörner, D. (1985). Verhalten, Denken und Emotionen [Behavior, thinking, and emotions]. In L. H. Eckensberger & E. D. Lantermann (Eds.), Emotion und Reflexivität (pp. 157-181). München, Germany: Urban & Schwarzenberg.

- ^ Dörner, D., & Wearing, A. (1995). Complex problem solving: Toward a (computer-simulated) theory. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 65-99). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ For example:

- The LOHHAUSEN project in Dörner, D., Kreuzig, H. W., Reither, F., & Stäudel, T. (Eds.). (1983). Lohhausen. Vom Umgang mit Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität [Lohhausen. On dealing with uncertainty and complexity]. Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber.

- Ringelband, O. J., Misiak, C., & Kluwe, R. H. (1990). Mental models and strategies in the control of a complex system. In D. Ackermann, & M. J. Tauber (Eds.), Mental models and human-computer interaction (Vol. 1, pp. 151-164). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers.

- ^ The two traditions are described in detail in Buchner, A. (1995). Theories of complex problem solving. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 27-63). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Anzai, K.; Simon, H. A. (1979). «The theory of learning by doing». Psychological Review. 86 (2): 124–140. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.86.2.124. PMID 493441.

- ^ Bhaskar, R.; Simon, Herbert A. (1977). «Problem Solving in Semantically Rich Domains: An Example from Engineering Thermodynamics». Cognitive Science. Wiley. 1 (2): 193–215. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog0102_3. ISSN 0364-0213.

- ^ e.g., Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A., eds. (1991). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 55-81.

- ^ Chi, M. T. H.; Feltovich, P. J.; Glaser, R. (1981). «Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices». Cognitive Science. 5 (2): 121–152. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog0502_2.

- ^ Anderson, J. R.; Boyle, C. B.; Reiser, B. J. (1985). «Intelligent tutoring systems» (PDF). Science. 228 (4698): 456–462. Bibcode:1985Sci…228..456A. doi:10.1126/science.228.4698.456. PMID 17746875. S2CID 62403455.

- ^ Stanovich, K. E.; Cunningham, A. E. (1991). «Reading as constrained reasoning». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 3–60. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Bryson, M.; Bereiter, C.; Scardamalia, M.; Joram, E. (1991). «Going beyond the problem as given: Problem solving in expert and novice writers». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 61–84. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Sokol, S. M.; McCloskey, M. (1991). «Cognitive mechanisms in calculation». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 85–116. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Voss, J. F.; Wolfe, C. R.; Lawrence, J. A.; Engle, R. A. (1991). «From representation to decision: An analysis of problem solving in international relations». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 119–158. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443. PsycNET: 1991-98396-004.

- ^ Wagner, R. K. (1991). «Managerial problem solving». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 159–183. PsycNET: 1991-98396-005.

- ^ Amsel, E.; Langer, R.; Loutzenhiser, L. (1991). «Do lawyers reason differently from psychologists? A comparative design for studying expertise». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 223–250. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Hegarty, M. (1991). «Knowledge and processes in mechanical problem solving». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 253–285. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Lesgold, A.; Lajoie, S. (1991). «Complex problem solving in electronics». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 287–316. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Kay, D. S. (1991). «Computer interaction: Debugging the problems». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 317–340. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Frensch, P. A.; Sternberg, R. J. (1991). «Skill-related differences in game playing». In Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A. (eds.). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 343–381. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Heppner, P. P., & Krauskopf, C. J. (1987). An information-processing approach to personal problem solving. The Counseling Psychologist, 15, 371-447.

- ^ Pólya, 1945

- ^ Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical Problem Solving. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- ^ Altshuller, Genrich (1994). And Suddenly the Inventor Appeared. Translated by Lev Shulyak. Worcester, MA: Technical Innovation Center. ISBN 978-0-9640740-1-9.

- ^ Sternberg, R. J.; Frensch, P. A., eds. (1991). Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0650-4. OCLC 23254443.

- ^ Hung, Woei (24 April 2013). «Team-based complex problem solving: a collective cognition perspective». Educational Technology Research and Development. 61 (3): 365–384. doi:10.1007/s11423-013-9296-3. S2CID 62663840.

- ^ Jewett, Pamela; Deborah MacPhee (October 2012). «Adding Collaborative Peer Coaching to Our Teaching Identities». The Reading Teacher. 66 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1002/TRTR.01089.

- ^ Wang, Qiyun (2009). «Design and Evaluation of a Collaborative Learning Environment». Computers and Education. 53 (4): 1138–1146. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.05.023.

- ^ Kai-Wai Chu, Samual; David Kennedy (2011). «Using Online Collaborative tools for groups to Co-Construct Knowledge». Online Information Review. 35 (4): 581–597. doi:10.1108/14684521111161945.

- ^ Legare, Cristine; Candice Mills; Andre Souza; Leigh Plummer; Rebecca Yasskin (2013). «The use of questions as problem-solving strategies during early childhood». Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 114 (1): 63–7. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2012.07.002. PMID 23044374.

- ^ Wang, Qiyan (2010). «Using online shared workspaces to support group collaborative learning». Computers and Education. 55 (3): 1270–1276. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.023.

- ^ Engelbart, Douglas (1962) Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework — section on Team Cooperation

- ^ Flew, Terry (2008). New Media: an introduction. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Henry, Jenkins. «Interactive audiences? The ‘collective intelligence’ of media fans» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Park, Jacob; Conca, Ken; Conca, Professor of International Relations Ken; Finger, Matthias (2008-03-27). The Crisis of Global Environmental Governance: Towards a New Political Economy of Sustainability. Routledge. ISBN 9781134059829. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Guazzini, Andrea; Vilone, Daniele; Donati, Camillo; Nardi, Annalisa; Levnajić, Zoran (10 November 2015). «Modeling crowdsourcing as collective problem solving». Scientific Reports. 5: 16557. arXiv:1506.09155. Bibcode:2015NatSR…516557G. doi:10.1038/srep16557. PMC 4639727. PMID 26552943.

- ^ Boroomand, A. and Smaldino, P.E., 2021. Hard Work, Risk-Taking, and Diversity in a Model of Collective Problem Solving. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(4).

- ^ Stefanovitch, Nicolas; Alshamsi, Aamena; Cebrian, Manuel; Rahwan, Iyad (30 September 2014). «Error and attack tolerance of collective problem solving: The DARPA Shredder Challenge». EPJ Data Science. 3 (1). doi:10.1140/epjds/s13688-014-0013-1.

Further readingEdit

- Beckmann, J. F., & Guthke, J. (1995). Complex problem solving, intelligence, and learning ability. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 177-200). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Brehmer, B. (1995). Feedback delays in dynamic decision making. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 103-130). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Brehmer, B., & Dörner, D. (1993). Experiments with computer-simulated microworlds: Escaping both the narrow straits of the laboratory and the deep blue sea of the field study. Computers in Human Behavior, 9, 171-184.

- Dörner, D. (1992). Über die Philosophie der Verwendung von Mikrowelten oder «Computerszenarios» in der psychologischen Forschung [On the proper use of microworlds or «computer scenarios» in psychological research]. In H. Gundlach (Ed.), Psychologische Forschung und Methode: Das Versprechen des Experiments. Festschrift für Werner Traxel (pp. 53-87). Passau, Germany: Passavia-Universitäts-Verlag.

- Eyferth, K.; Schömann, M.; Widowski, D. (1986). «Der Umgang von Psychologen mit Komplexität» [On how psychologists deal with complexity]. Sprache & Kognition (in German). 5: 11–26.

- Funke, J. (1993). Microworlds based on linear equation systems: A new approach to complex problem solving and experimental results. In G. Strube & K.-F. Wender (Eds.), The cognitive psychology of knowledge (pp. 313-330). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers.

- Funke, J. (1995). Experimental research on complex problem solving. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 243-268). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Funke, U. (1995). Complex problem solving in personnel selection and training. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 219-240). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Groner, M., Groner, R., & Bischof, W. F. (1983). Approaches to heuristics: A historical review. In R. Groner, M. Groner, & W. F. Bischof (Eds.), Methods of heuristics (pp. 1-18). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hayes, J. (1980). The complete problem solver. Philadelphia: The Franklin Institute Press.

- Huber, O. (1995). Complex problem solving as multistage decision making. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 151-173). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hübner, R. (1989). Methoden zur Analyse und Konstruktion von Aufgaben zur kognitiven Steuerung dynamischer Systeme [Methods for the analysis and construction of dynamic system control tasks]. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie, 36, 221-238.

- Hunt, E. (1991). Some comments on the study of complexity. In R. J. Sternberg, & P. A. Frensch (Eds.), Complex problem solving: Principles and mechanisms (pp. 383-395). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hussy, W. (1985). Komplexes Problemlösen — Eine Sackgasse? [Complex problem solving — a dead end?]. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie, 32, 55-77.

- Kluwe, R. H. (1993). «Chapter 19 Knowledge and Performance in Complex Problem Solving». The Cognitive Psychology of Knowledge. Advances in Psychology. Vol. 101. pp. 401–423. doi:10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62668-0. ISBN 9780444899422.

- Kluwe, R. H. (1995). Single case studies and models of complex problem solving. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 269-291). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kolb, S., Petzing, F., & Stumpf, S. (1992). Komplexes Problemlösen: Bestimmung der Problemlösegüte von Probanden mittels Verfahren des Operations Research ? ein interdisziplinärer Ansatz [Complex problem solving: determining the quality of human problem solving by operations research tools — an interdisciplinary approach]. Sprache & Kognition, 11, 115-128.

- Krems, J. F. (1995). Cognitive flexibility and complex problem solving. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European Perspective (pp. 201-218). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Müller, H. (1993). Komplexes Problemlösen: Reliabilität und Wissen [Complex problem solving: Reliability and knowledge]. Bonn, Germany: Holos.

- Paradies, M.W., & Unger, L. W. (2000). TapRooT — The System for Root Cause Analysis, Problem Investigation, and Proactive Improvement. Knoxville, TN: System Improvements.

- Putz-Osterloh, Wiebke (1993). «Chapter 15 Strategies for Knowledge Acquisition and Transfer of Knowledge in Dynamic Tasks». The Cognitive Psychology of Knowledge. Advances in Psychology. Vol. 101. pp. 331–350. doi:10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62664-3. ISBN 9780444899422.

- Riefer, D.M., & Batchelder, W.H. (1988). Multinomial modeling and the measurement of cognitive processes. Psychological Review, 95, 318-339.

- Schaub, H. (1993). Modellierung der Handlungsorganisation. Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber.

- Strauß, B. (1993). Konfundierungen beim Komplexen Problemlösen. Zum Einfluß des Anteils der richtigen Lösungen (ArL) auf das Problemlöseverhalten in komplexen Situationen [Confoundations in complex problem solving. On the influence of the degree of correct solutions on problem solving in complex situations]. Bonn, Germany: Holos.

- Strohschneider, S. (1991). Kein System von Systemen! Kommentar zu dem Aufsatz «Systemmerkmale als Determinanten des Umgangs mit dynamischen Systemen» von Joachim Funke [No system of systems! Reply to the paper «System features as determinants of behavior in dynamic task environments» by Joachim Funke]. Sprache & Kognition, 10, 109-113.

- Tonelli M. (2011). Unstructured Processes of Strategic Decision-Making. Saarbrücken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3-8465-5598-9

- Van Lehn, K. (1989). Problem solving and cognitive skill acquisition. In M. I. Posner (Ed.), Foundations of cognitive science (pp. 527-579). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wisconsin Educational Media Association. (1993). «Information literacy: A position paper on information problem-solving.» Madison, WI: WEMA Publications. (ED 376 817). (Portions adapted from Michigan State Board of Education’s Position Paper on Information Processing Skills, 1992).

External linksEdit

- Learning materials related to Solving Problems at Wikiversity

This is the sentence I’m writing

The system requires a stiff solver and appropriate ______, such as the Jacobian Matrix Pattern

I’ve been thinking of workarounds, but the example given is not something that avoids the problem or finds an alternate solution, but it helps in solving the original problem, making it much faster. They are not needed, but they help a great deal. Also Pattern is not the only one of these.

devices does not sound right either, because it evokes a physical object.

Maybe aids, but it is more related to people or humanitarian causes.

Is there a single word to express a group of (non-physical) things that help you reach a solution?

asked Jul 14, 2015 at 8:43

laureapresalaureapresa

4134 silver badges13 bronze badges

4

The word tool is often used metaphorically to refer to methods and software. For instance, a word processor is a common tool of writers and editors. And the Socratic Method is a tool employed by teachers.

See these definitions in ODO:

1.1 A thing used in an occupation or pursuit:

computers are an essential tool

the ability to write clearly is a tool of the trade1.3 Computing: A piece of software that carries out a particular function, typically creating or modifying another program.

answered Jul 14, 2015 at 9:09

BarmarBarmar

18.5k1 gold badge33 silver badges52 bronze badges

1

Although you have discounted it, I do think that device would work well here, perhaps with a qualifying, attributive adjective.

Likewise, I think that, whilst tool is used more commonly used in such circumstances, aid is also appropriate and would convey your meaning clearly.

The system requires a stiff solver and appropriate algorithmic device, such as the Jacobian Matrix Pattern.

A numerical device such as the Jacobian Matrix Pattern greatly assists in solving the problem.

An appropriate algorithmic device, such as the Jacobian Matrix Pattern, is an invaluable aid for computing the solution.

answered Jul 14, 2015 at 9:42

CharonCharon

8,9664 gold badges27 silver badges46 bronze badges

1

Might you consider using an adverb more specific to the function you are trying to describe? Perhaps «appropriate» is slightly too non-specific. However, if that is the word which suits your fancy, I might consider «application» to fill in your blank for these three reasons:

- A little alliteration never hurts to smooth over awkward meanings in sentences because the reader’s creativity gets engaged. Literary devices are a «stuck» writer’s best friend.

- The term «application» implies a quality of particularity, although it also leaves room for a broader sense of usage.

- «Application» also seems to fit your conditional clause here:

«…it helps in solving the original problem, making it much faster. They

are not needed, but they help a great deal.»

Best of luck! I look forward to reading your outcome. =)

answered Jul 14, 2015 at 11:44

2

How about «process«? (from Webster: a series of actions that lead to a particular result)

answered Jul 14, 2015 at 10:47

OldbagOldbag

13.2k20 silver badges41 bronze badges

The system requires a stiff solver and appropriate models, such

as the Jacobian Matrix Pattern.

- (n), a hypothetical description of a complex entity or process

- “the computer program was based on a model of the circulatory and

respiratory systems”.(vocab.com/suggested in comments, too)

answered Jul 14, 2015 at 12:26

MistiMisti

13.7k4 gold badges29 silver badges64 bronze badges

1

What is Problem Solving?

4 ‘don’ts’ and a ‘do’!

“What is problem solving?” may seem a straight forward question to answer, but if we were to ask the question differently, how would you answer: “What do you do, when you don’t know what to do?”

To explain problem solving we’ll look at some possible answers to this question and in doing so think about what problem solving is not to better understand what it is.

We began our article “definition of problem solving” by recognized the obvious: that problems are problematic. A problem means something may not be right, or something has gone wrong, or there is something that is unsatisfactory. Or perhaps there is a gap between what is expected and the reality of what is actually happening.

In other words you know something needs to be done, but do you know what to do? So what do you do, when you don’t know what to do? Sadly, people often do the wrong things!

The do’s and don’ts of problem solving

What is problem solving? Here are 5 possible responses to what you might do, when you don’t know what to do:

Panic – do you switch into panic mode, rush around and dive into potentially reckless action? Do you have a tendency to do something quickly and perhaps the problem will go away, or do you try and get enough people “wound-up” and involved, in the hope that between everyone something will get done?

Procrastinate (Put off) – in contrast to panic, procrastination is the equivalent of a rabbit being caught in the head-lights of a car and freezing. You don’t know what to do, and you freeze: taking no action at all. Alternatively, you might put off doing anything: perhaps the problem will go away if you leave it alone.

Pretend – this is similar to procrastination except that you pretend there isn’t a problem: that everything can go on as usual. Your response is to deny there is a problem, everything is fine.

Plough-on – here you recognize there is a problem but carry on regardless. Nothing is going to get in the way of you doing what you always have done, or what you want to do. Keep going and you may leave the problem behind you. The problem may not be relevant next week/month if you keep ploughing-on.

Problem solve – this is the response that you should take! When you don’t know what to do, use a process which helps you to find out what you should do. Problem solving is a process using techniques to help you find good solutions, even when you’re not sure what to do. For example, see our seven step problem solving process.

What is Problem Solving? An Alternative View

Problem solving then, is what you should do when you don’t know what to do. However, we may all be more susceptible to panic, procrastination, pretending or ploughing-on than we would care to admit. To avoid these responses think through your own approach to problem solving. You may want to use some of the articles, tools and resources highlighted below to build your own repertoire.

For more answers to the question “what is problem solving?” see our articles and problem solving exercises. You will also find a detailed process with links to tools to help you solve problems in our article Seven Step Problem Solving Process or if you are short of time the essential steps are in our article 7 problem solving steps. There is also a great story of the Charlie Brown approach to problem solving in our article decision making lesson.

What’s the Problem?

- Tool 1: When you don’t know what to do

- Tool 2: Defining questions for problem solving

- Tool 3: Finding the right problems to solve

- Tool 4: Problem solving check-list

- Tool 4a: Using the question check-list with your team

- Tool 5: Problem analysis in 4 steps

- Tool 5a: Using 4 Step problem analysis with your team

- Tool 6: Questions that create possibilities

- Tool 6a: Using the 5 questions with your team

- Tool 6b: Putting creativity to work – 5 alternate questions

- Tool 6c: Workshop outline

- Tool 7: Evaluating alternatives

- Tool 8: Creative thinking techniques A-Z

- Tool 9: The 5 Whys technique

Forage puts students first. Our blog articles are written independently by our editorial team. They have not been paid for or sponsored by our partners. See our full editorial guidelines.

Why do employers hire employees? To help them solve problems. Whether you’re a financial analyst deciding where to invest your firm’s money, or a marketer trying to figure out which channel to direct your efforts, companies hire people to help them find solutions. Problem-solving is an essential and marketable soft skill in the workplace.

So, how can you improve your problem-solving and show employers you have this valuable skill? In this guide, we’ll cover:

- Problem-Solving Skills Definition

- Why Are Problem-Solving Skills Important?

- Problem-Solving Skills Examples

- How to Include Problem-Solving Skills in a Job Application

- How to Improve Problem-Solving Skills

- Problem-Solving: The Bottom Line

Problem-solving skills are the ability to identify problems, brainstorm and analyze answers, and implement the best solutions. An employee with good problem-solving skills is both a self-starter and a collaborative teammate; they are proactive in understanding the root of a problem and work with others to consider a wide range of solutions before deciding how to move forward.

Examples of using problem-solving skills in the workplace include:

- Researching patterns to understand why revenue decreased last quarter

- Experimenting with a new marketing channel to increase website sign-ups

- Brainstorming content types to share with potential customers

- Testing calls to action to see which ones drive the most product sales

- Implementing a new workflow to automate a team process and increase productivity

Why Are Problem-Solving Skills Important?

Problem-solving skills are the most sought-after soft skill of 2022. In fact, 86% of employers look for problem-solving skills on student resumes, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook 2022 survey.

It’s unsurprising why employers are looking for this skill: companies will always need people to help them find solutions to their problems. Someone proactive and successful at problem-solving is valuable to any team.

“Employers are looking for employees who can make decisions independently, especially with the prevalence of remote/hybrid work and the need to communicate asynchronously,” Eric Mochnacz, senior HR consultant at Red Clover, says. “Employers want to see individuals who can make well-informed decisions that mitigate risk, and they can do so without suffering from analysis paralysis.”

Problem-Solving Skills Examples

Problem-solving includes three main parts: identifying the problem, analyzing possible solutions, and deciding on the best course of action.

Research

Research is the first step of problem-solving because it helps you understand the context of a problem. Researching a problem enables you to learn why the problem is happening. For example, is revenue down because of a new sales tactic? Or because of seasonality? Is there a problem with who the sales team is reaching out to?

Research broadens your scope to all possible reasons why the problem could be happening. Then once you figure it out, it helps you narrow your scope to start solving it.

Analysis

Analysis is the next step of problem-solving. Now that you’ve identified the problem, analytical skills help you look at what potential solutions there might be.

“The goal of analysis isn’t to solve a problem, actually — it’s to better understand it because that’s where the real solution will be found,” Gretchen Skalka, owner of Career Insights Consulting, says. “Looking at a problem through the lens of impartiality is the only way to get a true understanding of it from all angles.”

Decision-Making

Once you’ve figured out where the problem is coming from and what solutions are, it’s time to decide on the best way to go forth. Decision-making skills help you determine what resources are available, what a feasible action plan entails, and what solution is likely to lead to success.

How to Include Problem-Solving Skills in a Job Application

On a Resume

Employers looking for problem-solving skills might include the word “problem-solving” or other synonyms like “critical thinking” or “analytical skills” in the job description.

“I would add ‘buzzwords’ you can find from the job descriptions or LinkedIn endorsements section to filter into your resume to comply with the ATS,” Matthew Warzel, CPRW resume writer, advises. Warzel recommends including these skills on your resume but warns to “leave the soft skills as adjectives in the summary section. That is the only place soft skills should be mentioned.”

On the other hand, you can list hard skills separately in a skills section on your resume.

In a Cover Letter or an Interview

Explaining your problem-solving skills in an interview can seem daunting. You’re required to expand on your process — how you identified a problem, analyzed potential solutions, and made a choice. As long as you can explain your approach, it’s okay if that solution didn’t come from a professional work experience.

“Young professionals shortchange themselves by thinking only paid-for solutions matter to employers,” Skalka says. “People at the genesis of their careers don’t have a wealth of professional experience to pull from, but they do have relevant experience to share.”

Aaron Case, career counselor and CPRW at Resume Genius, agrees and encourages early professionals to share this skill. “If you don’t have any relevant work experience yet, you can still highlight your problem-solving skills in your cover letter,” he says. “Just showcase examples of problems you solved while completing your degree, working at internships, or volunteering. You can even pull examples from completely unrelated part-time jobs, as long as you make it clear how your problem-solving ability transfers to your new line of work.”

How to Improve Problem-Solving Skills

Learn How to Identify Problems

Problem-solving doesn’t just require finding solutions to problems that are already there. It’s also about being proactive when something isn’t working as you hoped it would. Practice questioning and getting curious about processes and activities in your everyday life. What could you improve? What would you do if you had more resources for this process? If you had fewer? Challenge yourself to challenge the world around you.

Think Digitally

“Employers in the modern workplace value digital problem-solving skills, like being able to find a technology solution to a traditional issue,” Case says. “For example, when I first started working as a marketing writer, my department didn’t have the budget to hire a professional voice actor for marketing video voiceovers. But I found a perfect solution to the problem with an AI voiceover service that cost a fraction of the price of an actor.”