Spoken word in particular is one of the most powerful forms of poetry today and these videos provide more than enough evidence of that. Whether you like poetry or not, prepare to be blown away.

Whether you like poetry or not, prepare to be blown away. Poetry is more than just flowery language from an archaic time; it’s a way to express deep truths that transcend words and rhythm. Spoken word in particular is one of the most powerful forms of poetry today and these videos provide more than enough evidence of that.

«Remember How We Forgot»

This spoken word by Shane Koyczan is a wonderful reminder of our childhood and what we might have lost over the years. In this moving piece, Koyczan explores his childhood experiences — many of which we might have shared with him in our own little ways — and laments how differently we view the world once we lose our childlike sense of wonder.

It’s not as dark or depressing as I’ve made it sound. In fact, this performance ends on a high note full of inspiration and motivation. The message is clear: let us not forget that we are each individuals with our own passions and let us remember to live as if we were truly alive.

«Mathematics»

In this piece, Holly McNish thoughtfully arranges a short story that explores the topic of immigration and xenophobia. Despite the politically-charged nature of the subject, she presents a clear and thoughtful stance that ought to ring true with all of us. I’m not one to concern myself with political debate, but this spoken word goes beyond that.

There’s a bit of mild cussing in this one so if you have sensitive ears, you should be wary of that before hitting play. I think it’s worth the watch even so.

«Knock Knock»

Here’s a spoken word that strikes deep to the core, appealing to the inner children within all of us who have ever struggled in our identity apart from our parents. Daniel Beaty recounts his experiences as the son of a prisoner and his lessons are words of wisdom for us all.

The ending might be a bit too saccharine for some, but I found his words both encouraging and motivational. Even if you think the message is a bit corny and idealistic, you can still appreciate the way in which he strings his words together and weaves a short tale. Brilliant.

«I Will Not Let Exam Results Decide My Fate»

The education system here in the US often takes center stage under the crosshairs of my peers. No system is perfect, of course, but there is a flaw that sits deep in the core of many education systems today. In this piece, Suli Breaks explores the question: if we’re all individuals with unique desires, passions, and skills, then why doesn’t the education system recognize that?

My takeaway from this was NOT that tests are inherently bad but that perhaps education needs a paradigm shift at its core. This piece should be especially powerful to those who have always just assumed that schooling is the way it is because «it’s always been that way.» Maybe it’s time for a change.

«What Teachers Make»

This is what happens when your life is driven by passion. With every word uttered, Taylor Mali oozes raw energy and pain — not a self-centered pain but a pain for those around him who can’t see that character, integrity, and honesty are more important than simply making money for the sake of it.

It’s easy to walk away from this video with a higher respect for teachers — at least for the teachers who truly believe in what they do and live to transform the lives of their students, not just teach to a test in order to look good before their peers. Real teachers who have a heart for their students are rare to find these days.

Are you a fan of the spoken word? If you know of any particularly outstanding videos that weren’t mentioned in this list, please share them with us in the comments.

Image Credits: dualdflipflop Via Flickr

Spoken Word Explained

These days poetry is a lot more than Shakespeare sonnets and posh accents. Led by ambassadors such as George the Poet and Polarbear, the world of spoken word is set to explode! Here’s your lowdown on the scene…

So what actually is it?

‘Spoken word’ is a tricky one to define. On the surface, it’s just poetry that’s written to be performed, but in reality it’s so much more. Spoken word can be delivered in a variety of styles and can even involve collaboration and experimentation with other art forms, including music, theatre and dance. It can be used to tell your own stories or to explore the stories of others.

But how’s that different from rapping in hip hop?

Hip hop and spoken word do cross over a lot, with both sharing influences and audiences, and following similar themes in the topics they cover. Some spoken word artists even incorporate raps and hip hop beats into their work.

The main way that they differ is that spoken word tends to be a lot more straight to the point, avoiding complicated metaphors in favour of stripped back and straight to the point lyrics.

Where has it come from?

Spoken word first kicked off with the American Beat Poet movement that took place in the 1940s and 1950s. This saw a group of authors in New York using their work to exploring and influence the American culture of the time.

Venting their frustrations with society, these poets started a tradition that has continued for many years, moving into the 1970s with punk poets like the UK’s John Cooper Clarke and famed dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, all the way up to today, where new social issues have brought upon a completely new era of spoken word.

Where in the past ‘spoken word’ might have been viewed as uncool or irrelevant, the new class of poets have given poetry a new sense of cool with stripped back promo videos and gigs in some of the most well-renowned venues.

Over the last decade Essex’s very own wordsmith Scroobius Pip has found success after forming a hip hop duo with Dan le Sac. Together, they’ve been able to launch a career that’s seen them top the podcast charts and put on sell out tours around Europe.

This clip contains some strong language.

The BBC is not responsible for external and third party content.

Who’s big in the scene today?

LionHeart, GREEdS, Talia Randall, Deci4Life — there is SO much great British talent out there right now! Here are our profiles for some of the biggest names…

“He’s really really intelligent but his poetry is accessible – he doesn’t alienate people, he talks about real stuff and he also fuses it with music, which is really exciting and and I think people can relate to that.”Cecilia Knap on George the Poet

George the Poet

Who: George Mpanga aka George The Poet

Where: North London

How: Began rapping at 15 year and later adapted his rap to poetry

3 Things to note:

- Studied politics, psychology and sociology at Cambridge university

- Finished no. 5 on the BBC Sound of 2015 poll

- Ambassador for IDEA — Prince Andrew’s digital business idea charity

Find out more: @georgethepoet on Twitter // www.iamgeorgethepoet.co.uk

Kate Tempest

Who: Kate Tempest – spoken word artist, playwright and poet

Where: South east London

How: Started out as a rapper, toured the spoken word circuit

3 things to note:

- Nominated for the Mercury Music Prize 2014

- Debut novel will be published in 2016

- Won 2 poetry slams at the renowned Nuyorican Poets Café in New York

Find out more: @katetempest on Twitter // www.katetempest.co.uk

Polarbear

Who: Steve Camden aka Polarbear – one of the most respected in the UK

Where: London via Birmingham

How: Accidentally got into it (an incident involving a broken P.A system)

3 things to note:

- Spent 4 years delivering a spoken word course at Roundhouse

- Performed all over the world including Glastonbury and the U.S

- Twice published author

Find out more: @homeofpolar on twitter // www.bearheart.org

Hollie McNish

Who: Hollie McNish aka Hollie Poetry

Where: Cambridge, London & Glasgow

How: Started scribbling poems at age 4, but didn’t perform them til age 23

3 Things to note:

- Previous UK slam poetry champion

- First poet to record an album at the world famous Abbey Road studios

- Her performances have clocked up over 4 million views on YouTube

Find out more: @holliepoetry on Twitter // www.holliepoetry.com

This clip contains some strong language.

The BBC is not responsible for external and third party content.

What’s special about it?

It gives people a voice

You don’t need a big fancy studio to lay down a track — unlike regular music, spoken word requires just two things — you and your voice.

As it’s so easy to launch yourself into spoken word, we’ve been able to hear unique stories from people and communities that might not normally reach the spotlight.

This clip contains some strong language.

The BBC is not responsible for external and third party content.

Jack Rooke is a stand-up poet from London who mixes spoken word with his unique style of comedy. In this video he tackles the issue of bereavement, explaining how finding humour in his darkest moment helped him work through everything.

There are no rules

This clip contains some strong language.

The BBC is not responsible for external and third party content.

Rhyme, or don’t rhyme; do it fast, or do it slow — it’s your call!

Joshua Idehen uses this freedom in My Love to catch the audience’s attention, changing the rhythm and style while he tells his story. The beauty of spoken word is you never really know what you’re going to get!

It can make you sit up and pay attention

While spoken word poetry can just involve telling stories, it generally tries to provoke some sort of reaction.

Without the distraction of big beats and fancy sets, a spoken word audience really has to take on board the words being said.

Performers such as Amaal Said use this to their advantage, cutting through silences to speak about the challenges and triumphs of being a young Muslim woman of colour growing up in the 21st century.

Speaking about this difference, George the Poet told an interviewer at The Guardian:

“I’d observed, as an MC and as a grime rapper, how people always glazed over the quality of the lyrics and lyricism of a lot of grime and rap and that always bothered me. So I always thought, well, if I take away the beat, slow down the delivery and give people the chance the digest every lyric, it might be received differently. People took it as poetry mainly because it always had strong social messages.”

Suli Breaks is another big name on the scene at the moment. The twenty-something from London shot to internet fame with his poem Why I Hate School But Love Education, with his video reaching over 6.5 million views.

Sounds good. How do I get involved?

So you’re ready to get stuck in? Great!

There’s a whole range of spoken word groups up and down the UK, all ready to welcome you and to help guide you to your first performance. We’ve picked out some of our favourites on the right →

If you don’t have a group in your area, the internet is also a great place to get started — simply search for ‘spoken poetry’ or ‘performance poetry’ online and start taking inspiration from the many spoken word artists that are already showcasing their work. When you’ve put decided what you want to say, prop yourself in front of your webcam, record a video of you performing and share it online — not only will help you to build your confidence ahead of hitting the real stage, it will also give you chance to receive that all important feedback.

If you’re lucky enough to live in the right area, you could even brave a spoken word open mic night. These see new and established artists taking to the stage to try out new material in front of supportive and hyped-up crowds. Either way, give it a go — you never know where it might lead!

Groups around the UK

More spoken word across the BBC

Download Article

Download Article

Spoken word is a great way to express your truth to others through poetry and performance. To write a spoken word piece, start by picking a topic or experience that triggers strong feelings for you. Then, compose the piece using literary devices like alliteration, repetition, and rhyme to tell your story. Polish the piece when it is done so you can perform it for others in a powerful, memorable way. With the right approach to the topic and a strong attention to detail, you can write a great spoken word piece in no time.

-

1

Choose a topic that triggers a strong feeling or opinion. Maybe you go for a topic that makes you angry, like war, poverty, or loss, or excited, like love, desire, or friendship. Think of a topic that you feel you can explore in depth with passion.[1]

- You may also take a topic that feels broad or general and focus on a particular opinion or perspective you have on it. For example, you may look at a topic like “love” and focus on your love for your big sister. Or you may look at a topic like “family” and focus on how you made your own family with close friends and mentors.

-

2

Focus a memorable moment or experience in your life. Pick an experience that was life changing or shifted your perspective on the world in a profound way. The moment or experience could be recent or from childhood. It could be a small moment that became meaningful later or an experience that you are still recovering from.[2]

- For example, you may choose to write about the moment you realized you loved your partner or the moment you met your best friend. You can also write about a childhood experience in a new place or an experience you shared with your mother or father.

Advertisement

-

3

Respond to a troubling question or idea. Some of the best spoken word comes from a response to a question or idea that makes you think. Pick a question that makes you feel unsettled or curious. Then, write a detailed response to create the spoken word piece.

- For example, you may try responding to a question like “What are you afraid of?” “What bothers you about the world?” or “Who do you value the most in your life?”

-

4

Watch videos of spoken word pieces for inspiration. Look up videos of spoken word poets who tackle interesting subjects from a unique point of view. Pay attention to how the performer tells their truth to engage the audience. You may watch spoken word pieces like:

- “The Type” by Sarah Kay.[3]

- “When a Boy Tells You He Loves You” by Edwin Bodney.[4]

- “Lost Voices” by Darius Simpson and Scout Bostley.[5]

- “The Drug Dealer’s Daughter” by Sierra Freeman.[6]

- “The Type” by Sarah Kay.[3]

Advertisement

-

1

Come up with a gateway line. The gateway line is usually the first line of the piece. It should sum up the main topic or theme. The line can also introduce the story you are about to tell in a clear, eloquent way. A good way to find a gateway line is to write down the first ideas or thoughts that pop into your head when you focus on a topic, moment, or experience.[7]

- For example, you may come up with a gateway line like, “The first time I saw her, I was alone, but I did not feel alone.” This will then let the reader know you are going to be talking about a female person, a “her,” and about how she made you feel less lonely.

-

2

Use repetition to reinforce an idea or image. Most spoken word will use repetition to great effect, where you repeat a phrase or word several times in the piece. You may try repeating the gateway line several times to remind the reader of the theme of your piece. Or you may repeat an image you like in the piece so the listener is reminded of it again and again.[8]

- For example, you may repeat the phrase “The first time I saw her” in the piece and then add on different endings or details to the phrase.

-

3

Include rhyme to add flow and rhythm to the piece. Rhyme is another popular device used in spoken word to help the piece flow better and sound more pleasing to listeners. You may follow a rhyme scheme where you rhyme every other sentence or every third sentence in the piece. You can also repeat a phrase that rhymes to give the piece a nice flow.[9]

- For example, you may use a phrase like «Bad dad» or «Sad dad» to add rhyme. Or you may try rhyming every second sentence with the gateway line, such as rhyming «The first time I saw him» with «I wanted to dive in and swim.»

- Avoid using rhyme too often in the piece, as this can make it sound too much like a nursery rhyme. Instead only use rhyme when you feel it will add an extra layer of meaning or flow to the piece.

-

4

Focus on sensory details and description. Think about how settings, objects, and people smell, sound, look, taste, and feel. Describe the topic of your piece using your 5 senses so the reader can become immersed in your story.

- For example, you may describe the smell of someone’s hair as «light and floral» or the color of someone’s outfit as «as red as blood.» You can also describe a setting through what it sounded like, such as «the walls vibrated with bass and shouting,» or an object through what it tasted like, such as «her mouth tasted like fresh cherries in summer.»

-

5

End with a strong image. Wrap up the piece with an image that connects to the topic or experience in your piece. Maybe you end with a hopeful image or with an image that speaks to your feelings of pain or isolation.

- For example, you may describe losing your best friend at school, leaving the listener with the image of your pain and loss.

-

6

Conclude by repeating the gateway line. You can also end by repeating the gateway line once more, calling back to the beginning of the piece. Try adding a slight twist or change to the line so the meaning of it is deepened or changed.

- For example, you may take an original gateway line like, “The first time I saw her” and change it to “The last time I saw her” to end the poem with a twist.

Advertisement

-

1

Read the piece aloud. Once you have finished a draft of the spoken word piece, read it aloud several times. Pay attention to how it flows and whether it has a certain rhythm or style. Use a pen or pencil to underline or highlight any lines that sound awkward or unclear so you can revise them later.[10]

-

2

Show the piece to others. Get friends, family members, or mentors to read the piece and give you feedback. Ask them if they feel the piece feels like it represents your style and attitude. Have others point out any lines or phrases they find wordy or unclear so you can adjust them.[11]

-

3

Revise the piece for flow, rhythm, and style. Check that the piece has a clear flow and rhythm. Simplify lines or phrases to reflect how you express yourself in casual conversation or among friends. You should also remove any jargon that feels too academic or complex, as you do not want to alienate your listener. Instead, use language that you feel comfortable with and know well so you can show off your style and attitude in the piece.[12]

- You may need to revise the piece several times to find the right flow and meaning. Be patient and edit as much as you need until the piece feels finished.

Advertisement

-

1

Memorize the piece. Read the piece aloud several times. Then, try to repeat it aloud without looking at the written words, working line by line or section by section. It may take several days for you to memorize the piece in its entirety so be patient and take your time.[13]

- You may find it helpful to ask a friend or family member to test you when you have memorized the piece to ensure you can repeat every word by heart.

-

2

Use your voice to convey emotion and meaning to the audience. Project your voice when you perform. Make sure you enunciate words or phrases that are important in the piece. You can also raise or lower your voice using a consistent pattern or rhythm when you perform. Try speaking in different registers to give the piece variety and flow.[14]

- A good rule of thumb is to say the gateway line or a key phrase louder than other words every time you repeat it. This can help you find a sense of rhythm and flow.

-

3

Express yourself with eye contact and facial gestures. Maintain eye contact with the audience when you perform the poem, rather than looking down or at a piece of paper. Use your mouth and face to communicate any emotions or thoughts expressed in the poem. Make facial gestures like a look of surprise when you describe a realization, or a look of anger when you talk about an injustice or troubling moment.[15]

- You can also use your hands to help you express yourself. Make hand gestures to the audience to keep them engaged.

- Keep in mind the audience will not really be paying attention your lower body or your legs, so you have to rely on your face, arms, and upper body in your performance.

-

4

Practice in front of a mirror until you feel confident. Use a mirror to get a sense of your facial expressions and your hand gestures. Maintain eye contact in the mirror and project your voice so you appear confident to the audience.

- Once you feel comfortable performing to the mirror, you may decide to perform for friends or family. You can also perform the spoken word piece at a poetry slam or an open mic night once you feel it is ready to share with others.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

Must there be a rhythm?

No. The goal should be to write natural-sounding speech. Most people do not naturally employ rhythm in their speech.

-

Question

What if I have no mirror at home for practicing?

You can practice with a friend or family member instead. Then, ask them to review your performance and offer constructive criticism.

-

Question

Why is rhyme important to the rhythm of the spoken word?

Actually, rhyme is not especially important in speech patterns, although it can certainly be used to comic or fanciful effect. If this question has been taken from a test, you should simply respond with whatever your teacher or textbook has told you about spoken rhyme.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To write spoken word, start by coming up with a gateway line, which sums up the main topic or theme and is typically the first line of the piece. As you write, work some repetition into your piece to reinforce the main ideas or images. You should also include rhyme to add flow and rhythm to the piece. Additionally, incorporate sensory details, such as how things felt, smelt, or tasted, to help draw your listener into the world you’ve created. Finally, end with a strong image that will stay with your audience or repeat the gateway line for closure. To learn how to end your spoken word piece, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 75,673 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Akinwumi Shulammite

Oct 24, 2022

«It’s inspiring, when I saw this article I became more curious about the spoken word that I want to practice and…» more

Did this article help you?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples

Listener

Фото —

Иван Балашов

Listener стартовали в далеком 2002-м как хип-хоп-проект Дэна Смита. Со временем звучание ужесточилось до такой степени, что Смита позвали записывать гостевой вокал для металкорщиков The Chariot, а сама группа выступала на разогреве у The Dillinger Escape Plan на недавно прошедших в России концертах.

Инструментал у Listener довольно агрессивный, отдаёт кантри-мотивами, а безумные участники делают каждую песню не слёзным рассказом о несчастной любви, а эмоциональной декларацией лучшего друга в баре под очередную пинту пива.

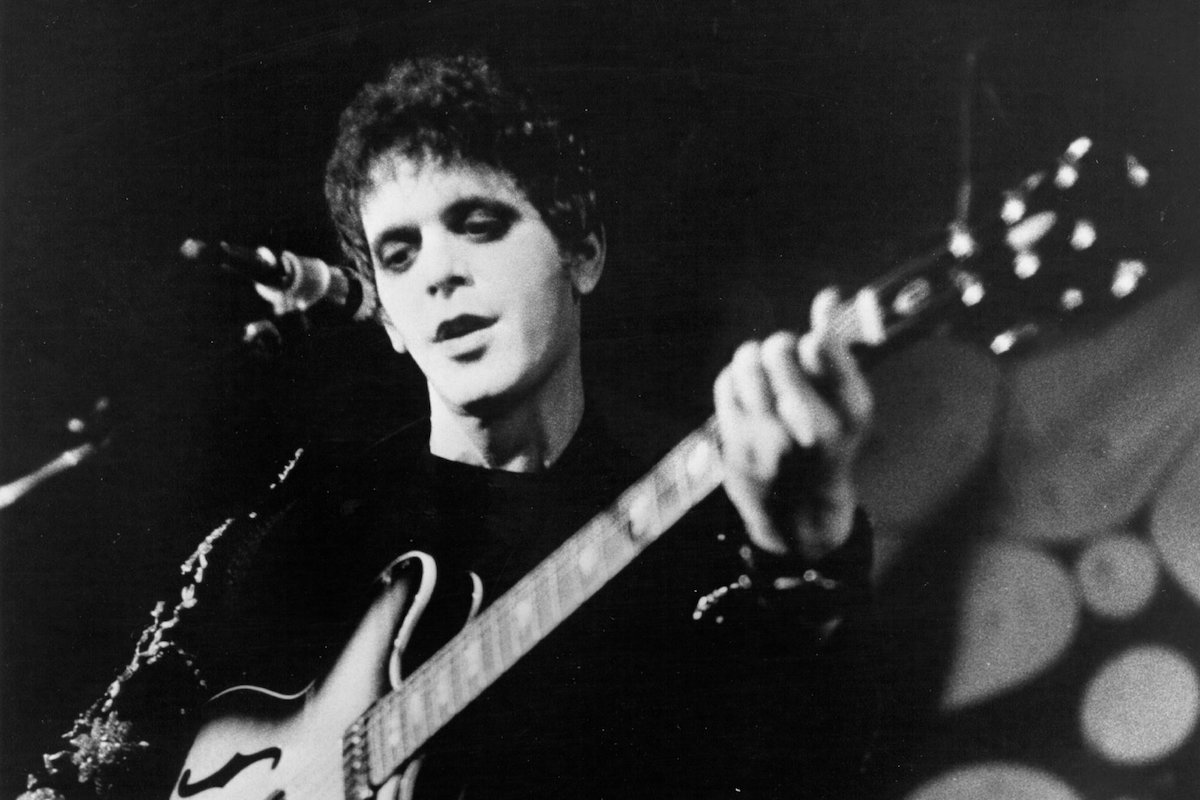

Лу Рид

Фото —

The Daily Beast

→

Лу Рид и его группа The Velvet Underground в своё время вдохновили невероятное количество музыкантов и тем самым повлияли на развитие рока. Например, о сильном влиянии Лу Рида на своё творчество говорил Дэвид Боуи.

Лу был в составе The Velvet Underground с 1964 по 1970 год, а после ухода из группы начал сольную карьеру. Он принял участие в песне Tranquilize группы The Killers, записал вместе с Gorillaz песню Plastic Beach и даже выпустил совместный альбом с Metallica!

Конечно, он выпускал и собственные альбомы. Наиболее необычный и несомненно заслуживающий внимания — The Raven, записанный в жанре spoken word. Главное в нём то, что он основан на рассказах Эдгара Аллана По. Так что скачивайте все 36 (!) песен, закрывайте глаза и погружайтесь в атмосферу.

Hotel Books

Фото —

Егор Зорин

→

Hotel Books обязательно понравятся любителям концептуализма. Кемерон Смит – единственный бессменный участник группы и её лицо – знает в этом толк. Например, песни July и August объединяет один общий клип, а для песни Lose One Friend существует своего рода парная композиция — Lose All Friends.

«Люди приходят и люди уходят. Некоторые приходят навестить, а другие просто потусить. И это моя книга поэм», — объясняет Кемерон название группы. Однако «люди приходят и люди уходят» — это не только про жизнь Смита, но и про саму группу. В последнем туре Hotel Books, например, за инструментал отвечали участники металкор-группы Convictions.

Дискография Hotel Books насчитывает уже 4 альбома, поэтому каждый сможет найти для себя новую любимую песню среди всего их разнообразия.

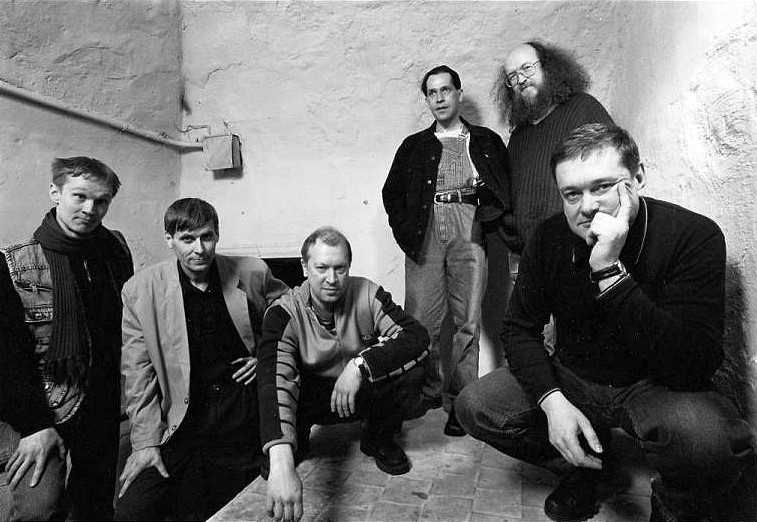

ДК

Фото —

Сергей Бабенко

→

ДК – советская группа, созданная в 1980 году. Название ей дал Сергей Жариков – создатель, идеолог и руководитель группы. ДК не стеснялись экспериментировать со звучанием и жанрами. Они первопроходцы российской экспериментальной музыки, творившие не только в жанре spoken word, но и авангарде, психоделическом роке, арт-панке, блюз-роке и еще множестве интересных жанров.

В 1984 году на Жарикова завели уголовное дело, а его группе, соответственно, запретили любые публичные выступления. Несомненно, это серьёзно сказалось на популярности ДК среди широких масс. Но всё же в музыкальных кругах они были группой известной и даже оказали сильное влияние на творчество Егора Летова (как на Гражданскую оборону, так и на проект Коммунизм), а также на группу Сектор Газа.

Canadian Softball

Фото —

Jarrod-Alonge

→

Canadian Softball – это вымышленная группа комика и музыканта Джаррода Алонжа, известного своими пародиями на рокеров и рок-группы. В 2015 году он выпустил альбом Beating a Dead Horse, в записи которого «участвовали» семь различных групп. На самом деле все семь групп были выдуманы комиком. Каждая группа пародировала определённый жанр. Звучание Canadian Softball, в частности, напоминало об эмо-группах поздних 1990-х — ранних 2000-х.

Состояла эта группа из самого Алонжа, вокалиста и гитариста, бассиста Уилла Грини и барабанщика/бэк-вокалиста Энди Конвэя. В альбоме у этой группы была только одна песня: The Distance Between You and Me is Longer Than the Title of this Song. Как видите, даже её название носит пародийный характер.

Позднее группа представила еще несколько песен, а 28 июля обещает выпустить альбом. В общем, дела у пародийной выдуманной группы идут даже лучше, чем у некоторых реально существующих артистов.

Skip to main contentSkip to search

Ideas worth spreading

SIGN IN

MEMBERSHIP

Type to search

A collection of TED Talks (and more) on the topic of Spoken word.

Skip playlists

Video playlists about Spoken word

9 talks

Spoken-word fireworks

Brave and beautiful expressions from some of the world’s most talented spoken-word performers, who weave stories in words and gestures.

Skip Talks

Talks about Spoken word

Naima Penniman

«Being Human»

4 minutes 2 seconds

Maria Popova

An excerpt from «Figuring»

4 minutes 26 seconds

Clint Smith

«Ode to the Only Black Kid in the Class»

1 minute

Marc Bamuthi Joseph

«You Have the Rite»

7 minutes 4 seconds

Climbing PoeTree

«Being Human» / «Awakening»

11 minutes 27 seconds

Sarah Kay

«A Bird Made of Birds»

4 minutes 43 seconds

Amanda Gorman

Using your voice is a political choice

7 minutes 16 seconds

Felice Belle and Jennifer Murphy

How we became sisters

12 minutes 35 seconds

IN-Q

A poet’s plea to save our planet

4 minutes 54 seconds

Ise Lyfe

We are not mud

7 minutes 8 seconds

Mwende «FreeQuency» Katwiwa

Black life at the intersection of birth and death

7 minutes 39 seconds

Cleo Wade

Want to change the world? Start by being brave enough to care

10 minutes 51 seconds

Emtithal Mahmoud

A young poet tells the story of Darfur

10 minutes 42 seconds

Lee Mokobe

A powerful poem about what it feels like to be transgender

4 minutes 11 seconds

Clint Smith

How to raise a Black son in America

5 minutes 3 seconds

Harry Baker

A love poem for lonely prime numbers

13 minutes 48 seconds

See all talks on Spoken word

Exclusive articles about Spoken word

Art is art, and other of this week’s comments

This week’s virtual mailbag included a personal take on why we should teach creativity, and the accusation that a TED speaker might just be «philosophically redundant.»

Posted Jul 2014

Recently, I’ve been getting a lot of questions about teaching spoken word poetry, especially when it comes to teaching students to craft a slam poem that connects with the audience on a personal level and sounds professional and polished.

I’ve taught slam poetry to students for the last seven+ years and nothing brings me more joy than seeing students gain the confidence to express themselves through spoken word.

I created these videos originally for my own students. They are quick and actionable and filled with examples for students to see the strategies in action.

How to Use These Slam Poetry Writing Tutorials

➡ Use these videos to flip the classroom or during a writing stations activity. It is best if you pull students for a quick student-led conference to discuss their takeaways and/or revisions made as a result of viewing the video. Alternatively, I have students leave me a comment on their draft reflecting on what they learned and how they revised as a result. This way, I can take a look at their progress and leave feedback / tell them to re-watch a certain part of the video if they need further work/application.

➡ We all know that teacher feedback is best when it’s targeted and specific as well as timely. Spoken word poetry is usually easy to breeze through and leave formative feedback for students, but the process is further simplified for me when I can leave a quick comment about what I’m noticing/what I like so far in a student’s draft and then link to the video that I think they need to watch for the “next step” in the revision process. This way, I can keep a student moving along and also hold them accountable for viewing these mini lessons and applying when I conference with them or check in the next time on their writing progress.

➡ Pop these videos into a recursive Google Form and let students pace themselves through the videos depending on their needs.

Picking a Spoken Word Poem Topic

When it comes to writing spoken word poetry, it’s important for students to explore a variety of different poets and examples of spoken word poetry. There are so many different styles that a student is sure to find a slam poet he or she can connect with because of the content of the poetry and/or the performance style.

➡️ The number one question I hear from teachers is focused on how to get students to engage and pick a topic for their slam poems.

In response, I want to say that it’s our job as teachers to open up the world of spoken word poetry in a way that doesn’t intimidate students, but rather invites them to explore and add their own voices into the mix.

I always start by debunking misconceptions about spoken word poems as students tend to think they have to be angry rants that are melodramatic and “over the top.” Not so. When students see writing a slam poem can be as simple as telling a story or sending a message, they can let down their guard and start to connect. Furthermore, when students see slam as an extension of who they are, they become invested in making it represent what they really care about and are invested in.

When it comes to picking a poem topic, students tend to go wide rather than deep. They think that having a topic = having a poem. Not so. A topic can turn into any number of different poems, depending on the angle a student chooses.

➡️ So, my number one tip for choosing a spoken word topic is to brainstorm a lot. Start students out with writing lists like Sarah Kay suggests. Conference with them, have them listen to a lot of slam poems, and it will come.

➡️ Second, I suggest showing students who are still struggling to get started this video on narrowing a topic and avoiding the two biggest slam poetry “killers”: melodrama and generic writing.

How to Write Spoken Word Poetry

Next, when students are drafting their slam poems, follow-up with these four mini-lessons.

➡️ The first lesson helps students to see how “show don’t tell” applies to their writing. Students will work to develop their writing with specific, concrete details and use of imagery.

➡️ The second lesson is for students who have a solid draft and are ready to fine-tune at the sound level. Using consonance, assonance, and alliteration is a way for students to make their poems sound cohesive, but it’s really important for students to consider the overall tone they’re going for and to choose soft or hard sounding word sounds to echo. This strategy is what creates a tone on a subtle sound-level, and it can also help students to achieve a really dramatic tone shift.

➡️ The third lesson is probably my favorite because I can always see the lightbulb moments for students who think that rhyme always has to be predictable, perfect end rhyme. See for yourself what other strategies you can make available to students and watch their slam poems transform from geek to fleek.

➡️ The final lesson I’ll share here is for final editing. Students need a little nudge to think about line divisions and omission of “fluff” words from their writing. For example, a lot of the time students can omit articles from their writing to achieve a cleaner and more poetic sound to their lines. Oh, and at the end of the video I model and “think aloud” as I edit a slam poem draft.

More Great Spoken Word Poetry Teaching Videos

In addition to my own videos above, I always use Guante’s five-video series on spoken word poetry. It is absolute gold for students (and for teachers who really want to help students)!

More Slam Poetry Teaching Resources

I would be remiss if I didn’t tell you about my FREE slam poetry guide for teachers. I’d love to share more ideas with you, so be sure to download it HERE if you haven’t already.

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 18 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.