I watched a trickle of dust filter through the light in the Workman’s Club on an unduly warm October Saturday. Speaking a line of a certain poem, I suddenly existed within, simultaneously, three places on the globe. The locales are wrapped in the fabric of how I percieve performance poetry’s relationship to the page, and to my own journey as a performer along geographic lines: Chicago, with its love of experimentation; Paris and its focus on magical illumination; and Dublin, in the wild freedom of its scene’s naissance.

Green Mill Lounge sits at the intersection of Lawrence and Broadway in the Uptown neighborhood on Chicago’s northside. Attitudes in this neighborhood can be as gritty as its mottled cigarette packs in gutters, as time-worn as the loose bricks in abandoned patches between apartment blocks. The lounge’s façade is a feast of 1920s-era signage. Its sheet of tiny bulbs cackle with a decadent glow, backlighting the neon emerald name in cursive. Green Mill was named in 1910 to rival the Moulin Rouge (“Red Mill”) of Paris. At the time, Uptown shared Montmartre’s predilection for lengthy bohemian evenings; the Gilded Age meets La Belle Epoque. During Prohibition, Al Capone’s favorite booth was directly west of the short end of the bar, past the booths along the north wall, positioned for clear views of both entrances. During America’s Jazz Age, when the lounge’s red-lit cabaret environs were the international toast, Billie Holiday often performed.

Speed forward to 1986. Both Uptown and Green Mill have suffered since the early ‘60s. Day drinking and drugs have long replaced nightlife. So it’s surprising that, under the new ownership of Dave Jemilo, the Green Mill – now a pile of scuffed bricks on a neglected corner – decided to use poetry as a revival tactic.

Construction worker Marc Smith approached Jemilo to organize a poetry cabaret ending with a competition, for the lounge’s slow Sunday nights. Smith was a poetry fanatic, eager to inject theatricality into Chicago’s scene, and he thought the emphasis should be on pageless performance. He became the grandfather of the slam movement. Uptown Poetry Slam debuted on 25 July 1986, with Smith drawing from baseball terminology for the name. Slam layed the groundwork for a style of powerful presence and hip-hop-inspired craft, furthering the notion of “spoken word” vs. recited verse. Removal of the page and reliance on rhythm and theatricalilty created a generation of writers in defiance of the notion of poetry as a staid, academic medium.

The last neighborhood I lived in before leaving my hometown was two miles from Lawrence and Broadway. The years frequenting the Uptown Slam were magical; words and those red shafts of light were dusted with glitter, at least from where I sat. Slam was a quiet escape inward, as the poets flowed everything inside their vessels into an invisible powder keg suspended between the audience and themselves. These types of nights had a markedly different energy than traditional poetry evenings focused on relating — that is, making audible — words on a page. The difference lies in embodiment of the words and the dissolution of barriers between spectator and spectated. The Green Mill became spoken word Mecca, and the orignal format of one-hour open mike, one-hour featured guest(s), then two-hour competition continues each Sunday, 28 years after its inception.

It’s fascinating how spoken word has traveled since the days of America’s “Def Poetry Jam” tv show (2002-2007), and how each scene is deeply rooted in sense of place. What was the line from “The Impossible” that gave me pause? “The lights on top of Moulin Rouge, turning lust into a holy aspiration.”

A reviewer of the Lingo show graciously said I “had a sense of both metre and theatre.” Metre, theatre, or communicative urgency in my spoken word were no doubt influenced by those hallowed evenings in America’s answer to the “Red Mill.” There, lust for words sparked many an aspiration. There was a new thirst for presenting and receiving poetry. Now Lingo has capitalized on the scene having travelled full-force to Ireland, land of barroom bards.

As Lingo organizer Stephen James Smith put it, “Spoken word is the recharging of our tradition.”

Many people who’ve been involved in the Dublin poetry scene for a long time, such as festival organizer Phil Lynch, say that only in the last five years have things exploded as they have. There are a multitude of weekly and monthly spoken word showcase nights, though it’s still niche entertainment. Six Lingo organizers dedicated their time for free and worked tirelessly for more than one year to gather Dublin’s prominent showcases and a plethora of individual artists, galvanizing and culminating the emerging energy.

Showcases across three days were Nighthawks and The Monday Echo at Smock Alley Theatre; Brownbread Mixtape, A-Musing, PETTYCASH, and Weekly General Meeting at Workman’s Club; and Milk and Cookies at Roasted Brown Café. Less “underground” poets Paula Meehan, current chair of Irish poetry; and Athenry-based publishing powerhouse, English professor, and slam champ Elaine Feeney featured at Sunday’s “Lyrical Miracles.”

Special projects such as SHOUT OUT! for teen poets and the Lingo Bingo audience participation event, an opening night of Irish major players, and international headliners Polarbear (UK) and Abby Oliviera (NI/SCT) added variety and spice. Of course, as it is church in spoken word culture, there was a slam at the end filled with more energy and gusto than I’d seen my Irish comrades emit thus far. Twenty-four poets there battled and raged for four and a half hours. Oliviera’s strongly delivered politcal laments took home first prize.

Style and thematic matter ran the gamut. Several poets integrated reading from paper into their sets. For example, at the opening-night Lingo is a Go! event at Workman’s, Dublin-based Dave Lordan intoned in somber incantations traditional Irish literary themes of death and uncertainty; “Angel of the Flats” Karl Parkinson, known for his gangly bravado on themes of crime and the artists’ life, alternated reading from his book, deftly maintaining the energy; and John Cummins (see video below), current All-Ireland Slam champion, took his words to the air with a full band. Given Ireland’s history of balladry and the integration of music and poetry so prevalent throughout the scene here, the anticipation for Cummins’ foray was understandable, and his lively integration delivered. At the slam, hilarious storyteller Paul Timoney and shrewdly profound Stephen Clare were final-round contenders, whereas their brand of quirk might not fit in at New York’s Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe.

With all that was on display, what can be said to characterize Ireland’s scene, as it’s been shown to run right up and stand beside its forbears in passion and dedication? It’s the freedom allotted its practitioners to find themselves and their stride. It is the openness of audiences. There are no “hip rules” yet because the scene is burgeoning. In essence, it is ripe for finding itself.

Late during the closing hip-hop party on Sunday at The Liquor Rooms, Smith and I said tender goodbyes. The room around us buzzed with a sense of pride among minglers reluctant to call it a night. He said to me, alive with the sheen of words and their recognition, “I was in your fine city recently. I went to the Green Mill and the Uptown Slam. I was in awe. Floored.” I wanted to tell him not to be overly concerned at the moment – to keep his focus on the grass he’d just watered.

With Lingo, “Spoken word went from underground to overground,” organiser Colm Keegan said. And the field is wide open. Let’s create our own rules.

(c) Clara Rose Thornton

Arriving

Where on Temple Square is the Tabernacle?

The Tabernacle, a landmark with its recognizable silver dome, is located to the west of the Salt Lake Temple and south of the North Visitors’ Center. The Assembly Hall is south of the Tabernacle.

Temple Square Map »

Where on Temple Square is the Conference Center?

The Conference Center is located at 60 West North Temple Street on the north side of North Temple Street, across the street from the North Visitors’ Center.

Temple Square Map »

How do I get to Temple Square?

Temple Square is located in downtown Salt Lake City. It is bordered by 200 North Street, West Temple Street, South Temple Street, and State Street. North Temple Street runs through Temple Square and separates the Conference Center from the other buildings on Temple Square.

View on Map »

Temple Square can also be accessed by UTA’s TRAX Rail System. There are several stops on the Blue Line and Green Line near Temple Square.

UTA Website »

Where can I park my car near Temple Square?

Generally, the Conference Center Parking Lot, which is accessed on West Temple and North Temple Streets, is open to the public and free of charge on Sundays for The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square’s broadcasts of Music & the Spoken Word.

Please note that the Conference Center Parking Lot is not open to the public during general conference (first Sunday in April and October) or other major events (like the Choir’s concerts). Parking fills up quickly during Temple Square events and is not guaranteed.

For additional parking information, visit the resources below:

Temple Square Events »

Salt Lake City Parking »

Attending

What time do doors open at the Tabernacle?

Doors open at 8:30 a.m. on Sunday morning.

What time should I arrive to attend Music & the Spoken Word?

Music & the Spoken Word guests should be in their seats at least 15 minutes prior to the start of the broadcast. On busy weekends, 30 minutes is advisable.

Is Music & the Spoken Word located at the Tabernacle or the Conference Center?

Check here for seasonal updates.

How long does Music & the Spoken Word last?

Music & the Spoken Word is a 30-minute program.

How often does Music & the Spoken Word take place?

Music & the Spoken Word is broadcast live from Temple Square each Sunday, unless the Choir is on tour.

Do I need tickets to attend Music & the Spoken Word?

With a few exceptions, you do not need a ticket to attend a broadcast of Music & the Spoken Word. Guests will need tickets for Music & the Spoken Wordbroadcasts during general conferences, which take place the first Sundays of April and October.

What is appropriate attire for attending a broadcast of Music & the Spoken Word?

Sunday best or business casual is recommended, though we welcome all guests regardless of dress.

Can I bring my child to Music & the Spoken Word?

All Temple Square performances, including broadcasts of Music & the Spoken Word, are limited to those 8 years of age and above due to the live nature of the recording. An overflow location is provided for those who come with children under 8 years of age. A video feed of the broadcast is shown in the overflow location.

Can I bring food or drink inside the Tabernacle or Conference Center?

No, bringing food or drinks is not permitted inside the Tabernacle or Conference Center. Water is allowed in clear plastic water bottles only. Metal water bottles are prohibited.

Can I bring a bag inside the Tabernacle or Conference Center?

Large bags, backpacks, and packages are prohibited. Small bags and purses will be allowed into the event but will be screened or visually inspected. Laptop computers are prohibited. Event venues will not accept or store any personal items.

Can I take photos or video or audio recordings during Music & the Spoken Word?

During the 9:30 a.m.-10:00 a.m. broadcast of Music & the Spoken Word taking photos and video or audio recordings is not permitted.

However, taking photos and videos is permitted during the morning run-through rehearsal (approximately 8:30 a.m.-9:00 a.m.) and after the broadcast. The Choir sings «God Be With You Till We Meet Again» after each broadcast, and this is an excellent opportunity for pictures.

Note: Large cameras with detachable lenses, tripods, or selfie sticks are not permitted in the venues.

Get More

How can I watch the Music & the Spoken Wordbroadcast each week?

The broadcast can be watched on the Choir’s website, YouTube channel and Facebook channel each Sunday beginning at 9:30 a.m. (mountain time). You can also watch the broadcasts on BYUtv available on many cable and satellite systems or listen on Sirius XM radio.

To locate local broadcasts for your specific city or state check here.

To view past Music & the Spoken Wordepisodes check here.

Do you announce the songs and the Spoken Word ahead of time?

The music repertoire and Spoken Word message are sent out the Friday before each broadcast in Choir Notes, the Choir’s weekly email newsletter.

Subscribe to the Choir’s weekly newsletter »

Can I attend a Music & the Spoken Word rehearsal?

Unless otherwise noted, Choir rehearsals are open to the public. The rehearsals take place on Thursday evenings from 7:30 p.m. until 9:30 p.m. The Choir will rehearse in the location of the upcoming Music & the Spoken Wordbroadcast. Check here to see date exceptions and locations.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples

the spoken/written word

(redirected from the spoken word)

References in classic literature

?

The connection between the spoken word and the word as it reaches the hearer is causal.

A single word, accordingly, is by no means simple it is a class of similar series of movements (confining ourselves still to the spoken word).

When he was a little boy, he had heard that there were things that obeyed the spoken word!

The Book of Army Management says: On the field of battle, the spoken word does not carry far enough: hence the institution of gongs and drums.

It must not pass without the spoken word. I love you!»

The spoken words that are inaudible among the flying spindles; those same words are plainly heard without the walls, bursting from the opened casements.

In everything save the spoken words I crave she has promised me her love.

Acting on this plan, I filled in each blank space on the paper, with what the words or phrases on either side of it suggested to me as the speaker’s meaning; altering over and over again, until my additions followed naturally on the spoken words which came before them, and fitted naturally into the spoken words which came after them.

Many believe Juan Miguel and the spoken word itself have helped kept the Filipino language alive, especially in times when learning foreign languages seems to have become popular among Pinoys.

‘The Spoken Word Tour — I Talk Too Much’ is coming to Loughborough Town Hall on May 5 when he will spill the beans on his relationship with the late Rick Parfitt, on what it was like to play to a global audience of 1.9 billion at Live Aid and what makes him more passionate than ever about Status Quo.

A festival of music, the spoken word and art will take place in Stirling over four days fromThursday September 20.

Juan Miguel Severo, foremost figure of the spoken word phenomenon in the Philippines, and V.E.

And most of all, I want to make the UAE proud and put the country on the spoken word map.

The spoken word is a very powerful tool, and no one knows that better than veteran poet, DJ and recording artist Haji Mike, who will give a workshop on the matter on Saturday.

Idioms browser

?

- ▲

- the soft option

- the soft/easy option

- the something to end all sths

- the sooner the better

- the soul of (something)

- the soul of discretion

- the sow that eats her farrow

- the sow that eats its farrow

- the sparks fly

- the spectre at the feast

- the spirit is willing

- the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak

- The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak

- the spirit is willing, but the/(one’s) body is weak

- the spirit is willing, but the/(one’s) flesh is weak

- the spirit moves (one)

- the spirit moves someone

- the spirit of the age

- the spirit of the law

- the spirit of the times

- the spit and image of (one)

- the spit of (one)

- the spitten image of (one)

- the spitting image

- the spitting image of (one)

- the spoken word

- the spoken/written word

- the sport of kings

- the spotlight

- the squeaking wheel gets the grease

- the squeaking wheel gets the oil

- the squeaky wheel gets oiled

- the squeaky wheel gets the grease

- the squeaky wheel gets the grease/oil

- the squeaky wheel gets the oil

- the squirts

- the squits

- the staff of life

- the staggers

- the stake

- the standard bearer

- the stars align

- the Stars and Stripes

- the stars are aligned

- the stars have aligned

- the state of play

- the status quo

- the sticks

- the still of (the) night

- the still of the night

- the still small voice

- ▼

Full browser

?

- ▲

- the spitting image of (someone)

- the spitting image of her

- the spitting image of him

- the spitting image of me

- the spitting image of one

- the spitting image of someone

- the spitting image of the very likeness of

- the spitting image of them

- the spitting image of us

- the spitting image of you

- The splendid little war

- The splendid little war

- The splendid little war

- The splendid little war

- The splendid little war

- the split decision

- the split-decision

- The splits

- The splits

- The splits

- The splits

- The splits

- the spoil sport spoil sport, a

- the spoil-sport spoil-sport, a

- The Spoiler

- the spoiler alert

- The Spoils

- The Spoils of War

- The spoils system

- the spoilsport spoilsport, a

- the spoken word

- the spoken/written word

- The Sponge

- the sponger

- The Sport of Kings

- The Sport Psychologist

- The Sporting Clubs of Niagara

- The Sporting Exchange Limited

- The Sporting Exchange Ltd.

- The Sporting Life

- The Sporting News

- The Sporting News Points

- The Sports Authority

- The Sports Factory

- The Sports Law Professor

- The Sports Management Group

- The Sports Network

- the spot check

- The Spotlight

- the spotlight, into

- the spread

- The Spring Chicken

- the spring fling

- the spring-chicken

- the Springboks

- the Springboks

- The Springfield Anglican College

- The Spriter’s Resource

- the spur of the moment

- The Spy Who Loved Me

- The Squadron Sinister

- ▼

Listener

Фото —

Иван Балашов

Listener стартовали в далеком 2002-м как хип-хоп-проект Дэна Смита. Со временем звучание ужесточилось до такой степени, что Смита позвали записывать гостевой вокал для металкорщиков The Chariot, а сама группа выступала на разогреве у The Dillinger Escape Plan на недавно прошедших в России концертах.

Инструментал у Listener довольно агрессивный, отдаёт кантри-мотивами, а безумные участники делают каждую песню не слёзным рассказом о несчастной любви, а эмоциональной декларацией лучшего друга в баре под очередную пинту пива.

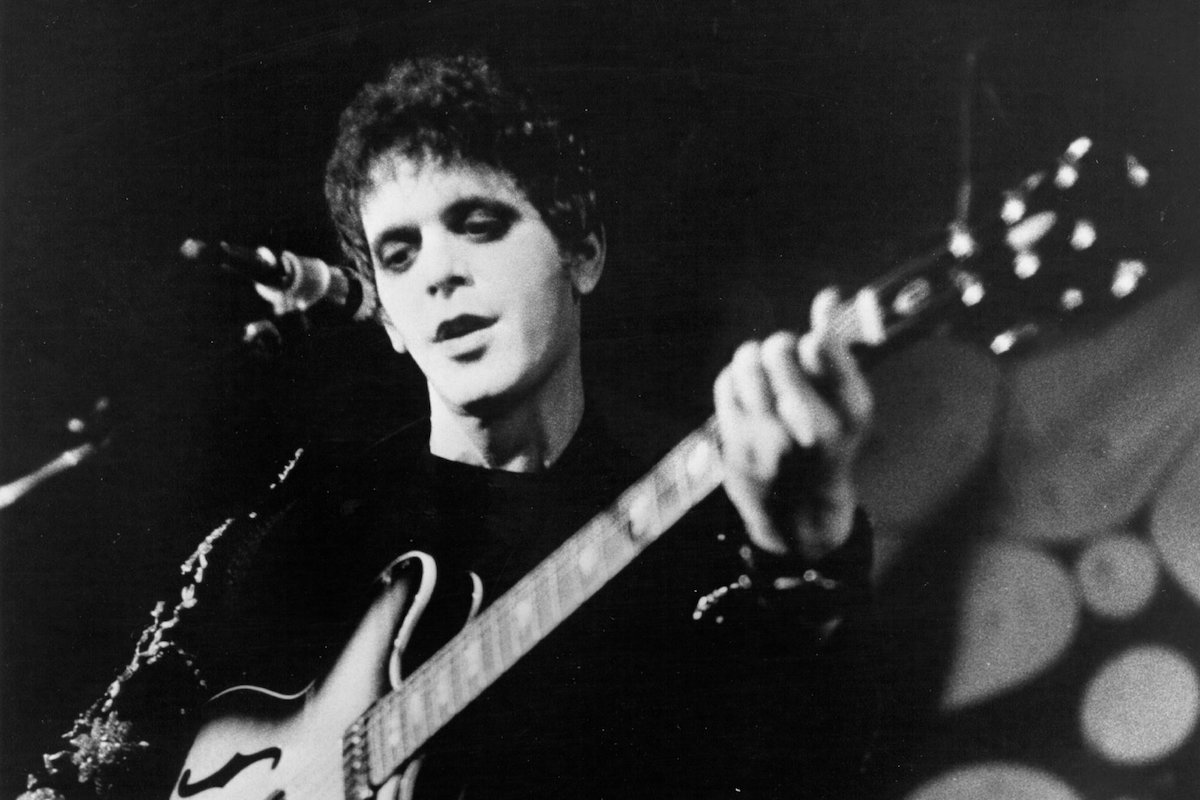

Лу Рид

Фото —

The Daily Beast

→

Лу Рид и его группа The Velvet Underground в своё время вдохновили невероятное количество музыкантов и тем самым повлияли на развитие рока. Например, о сильном влиянии Лу Рида на своё творчество говорил Дэвид Боуи.

Лу был в составе The Velvet Underground с 1964 по 1970 год, а после ухода из группы начал сольную карьеру. Он принял участие в песне Tranquilize группы The Killers, записал вместе с Gorillaz песню Plastic Beach и даже выпустил совместный альбом с Metallica!

Конечно, он выпускал и собственные альбомы. Наиболее необычный и несомненно заслуживающий внимания — The Raven, записанный в жанре spoken word. Главное в нём то, что он основан на рассказах Эдгара Аллана По. Так что скачивайте все 36 (!) песен, закрывайте глаза и погружайтесь в атмосферу.

Hotel Books

Фото —

Егор Зорин

→

Hotel Books обязательно понравятся любителям концептуализма. Кемерон Смит – единственный бессменный участник группы и её лицо – знает в этом толк. Например, песни July и August объединяет один общий клип, а для песни Lose One Friend существует своего рода парная композиция — Lose All Friends.

«Люди приходят и люди уходят. Некоторые приходят навестить, а другие просто потусить. И это моя книга поэм», — объясняет Кемерон название группы. Однако «люди приходят и люди уходят» — это не только про жизнь Смита, но и про саму группу. В последнем туре Hotel Books, например, за инструментал отвечали участники металкор-группы Convictions.

Дискография Hotel Books насчитывает уже 4 альбома, поэтому каждый сможет найти для себя новую любимую песню среди всего их разнообразия.

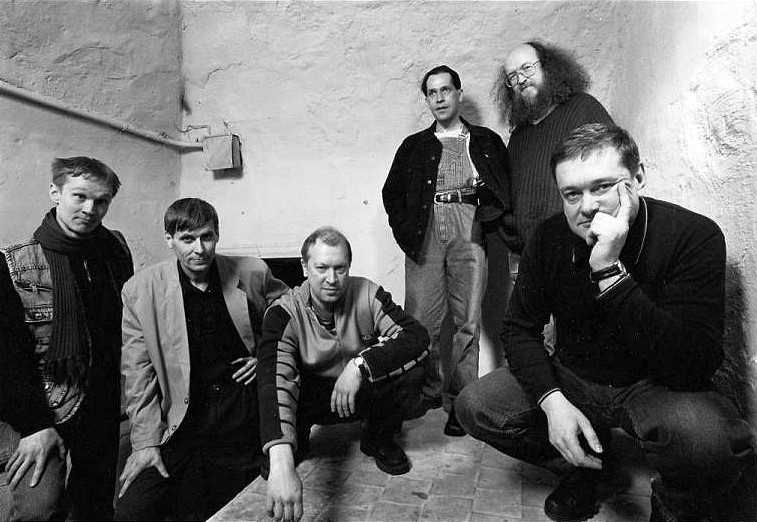

ДК

Фото —

Сергей Бабенко

→

ДК – советская группа, созданная в 1980 году. Название ей дал Сергей Жариков – создатель, идеолог и руководитель группы. ДК не стеснялись экспериментировать со звучанием и жанрами. Они первопроходцы российской экспериментальной музыки, творившие не только в жанре spoken word, но и авангарде, психоделическом роке, арт-панке, блюз-роке и еще множестве интересных жанров.

В 1984 году на Жарикова завели уголовное дело, а его группе, соответственно, запретили любые публичные выступления. Несомненно, это серьёзно сказалось на популярности ДК среди широких масс. Но всё же в музыкальных кругах они были группой известной и даже оказали сильное влияние на творчество Егора Летова (как на Гражданскую оборону, так и на проект Коммунизм), а также на группу Сектор Газа.

Canadian Softball

Фото —

Jarrod-Alonge

→

Canadian Softball – это вымышленная группа комика и музыканта Джаррода Алонжа, известного своими пародиями на рокеров и рок-группы. В 2015 году он выпустил альбом Beating a Dead Horse, в записи которого «участвовали» семь различных групп. На самом деле все семь групп были выдуманы комиком. Каждая группа пародировала определённый жанр. Звучание Canadian Softball, в частности, напоминало об эмо-группах поздних 1990-х — ранних 2000-х.

Состояла эта группа из самого Алонжа, вокалиста и гитариста, бассиста Уилла Грини и барабанщика/бэк-вокалиста Энди Конвэя. В альбоме у этой группы была только одна песня: The Distance Between You and Me is Longer Than the Title of this Song. Как видите, даже её название носит пародийный характер.

Позднее группа представила еще несколько песен, а 28 июля обещает выпустить альбом. В общем, дела у пародийной выдуманной группы идут даже лучше, чем у некоторых реально существующих артистов.