a slur is a word that is used against someone of a specific race, condition, sexuality, gender, illness etc. slurs can be reclaimed and used by the person they were used against, for example someone who is black can reclaim the n word, someone who is gay can reclaim the f slur.

‘bro did you hear that lil huddy said a slur?’

‘no, which one did he say?’

‘he said the n word, he’s a horrible person’

‘oh my god he’s terrible’

Get the slur mug.

1) to speak incoherntly esp. while intoxicated or due to a speaking disabilty like a lisp

2)To slander /to be slack tongued/an aspersion or disparaging remark

3)To say something that is ridiculous , inarticulate or purely obtuse

1)waassupppppp mannnn , howwwzzz youuu ….

2)i waz goingz therez

3)Stop using derisory racist slurs

4)yaooo maan u dawgy dog.(??wth is that)

Get the slur mug.

From Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Slur might mean:

- A slur is a type of offensive word that can cause hatred. (See Pejorative)

- To slur also means to talk very fast and mix words together in doing so.

- A slur might also refer to a symbol in music which tells the musician to play legato.

Content note: this post contains examples of offensive slur-terms.

Last week, the British edition of Glamour magazine published a column in which Juno Dawson used the term ‘TERF’ to describe feminists (the example she named was Germaine Greer) who ‘steadfastly believe that me—and other trans women—are not women’. When some readers complained about the use of derogatory language, a spokeswoman for the magazine replied on Twitter that TERF is not derogatory:

Trans-exclusionary radical feminist is a description, and not a misogynistic slur.

Arguments about whether TERF is a neutral descriptive term or a derogatory slur have been rumbling on ever since. They raise a question which linguists and philosophers have found quite tricky to answer (and which they haven’t reached a consensus on): what makes a word a slur?

Before I consider that general question, let’s take a closer look at the meaning and history of TERF. As the Glamour spokeswoman said, it’s an abbreviated form of the phrase ‘Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist’; more specifically it’s an acronym, constructed from the initial letters of the words that make up the phrase. Some people have suggested this means it can’t be a slur. I find that argument puzzling, since numerous terms which everyone agrees are slurs are abbreviated forms (examples include ‘Paki’, ‘Jap’, ‘paedo’ and ‘tranny’). But in any case, there’s a question about the status of TERF as an acronym. Clearly it started out as one, but is it still behaving like one now?

To see what I’m getting at, consider an acronym from the 1940s: ‘radar’. Do you know what all the letters stand for? I do, but only because I’ve just looked it up. I’ve been using the word for 50-odd years without realising it meant ‘RAdio Detection And Ranging’—a feat made possible by the fact that ‘radio detection and ranging’ isn’t really what it means any longer. Over time it’s become just an ordinary word, which is used without reference to its origins as an acronym. No one mentally expands the letters R-A-D-A-R into words; no one imagines that ‘gaydar’ must be short for ‘gay detection and ranging’. Also (a trivial but telling sign) no one now writes ‘radar’ in all caps.

I’ve been writing TERF in all caps, but these days you also see it written ‘Terf’ or ‘terf’. That’s one sign it’s going the same way as ‘radar’, becoming a word which can be used without knowing what the letters of the original acronym stand for. Another sign is the way it’s now used to describe people (e.g., men) who don’t fit the original specification, in that they aren’t radical feminists. It looks as if at least some users of the term don’t define it strictly as meaning ‘trans-exclusionary radical feminist’, but use it with a more generic meaning like ‘transphobic person’.

This kind of change is common in the history of words. Word-meaning is inherently unstable, liable to vary among different groups of users and to change over time, because we don’t learn the meanings of most words by looking them up in some authoritative reference book, we figure them out from our experience of hearing or seeing words used in context.

It’s easy to see how that might shift the meaning of TERF in the way I’ve just suggested. Imagine you hear two of your friends discussing a mutual acquaintance who they refer to as a TERF. You’ve never encountered the term before and you have no way of knowing it’s a short form of a longer phrase (because it’s a true acronym, pronounced not as a series of letters but as a single syllable that rhymes with ‘smurf’). So you listen to what’s being said about the TERF in question and make the simplest inference compatible with what you’re hearing: that TERF means a transphobic person.

If TERF’s meaning has started to shift that’s actually a sign of its success (words evolve as they spread to new users and contexts). But it makes the argument that TERF is just a neutral descriptive label for a specific group of people less convincing. That argument either takes no account of the way usage has changed over time, or else it’s a version of the etymological fallacy (‘however people actually use a word, its original meaning is the true meaning’).

But the fact that a word isn’t a neutral description doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a slur. We’re back to the question philosophers and semanticists have found so tricky: on what basis can we say that a word is a slur?

As I’ve already mentioned, the people who’ve written on this subject don’t agree on what the answer is. And after reading their various accounts, I’m not sure I believe there’s a single right answer. Rather, I think there are a number of criteria which need to be considered. If we’re in doubt about a word’s status as a slur, we can try asking the following questions, and then looking at the overall balance of the answers.

My first two questions are based on what the philosopher Jennifer Hornsby proposes as the two fundamental features of a derogatory term or slur.

Is the word commonly understood to convey hatred or contempt?

Does the word have a neutral counterpart which denotes the same group without conveying hatred/contempt?

This definition seems to have been constructed using racial/ethnic slurs as a prototype. In these cases it’s generally understood that the slur term, used in preference to a neutral term which denotes the same group of people, communicates hatred/contempt as part of its meaning (that’s the difference between, say, ‘Jew’ and ‘kike’). This doesn’t help us much with terms like TERF whose status as slurs is disputed. TERF is certainly understood by some people to convey hatred and contempt, but others deny it conveys those things.

It’s also unclear whether there’s a neutral term which TERF contrasts with. TERF doesn’t so much refer to a pre-existing group as bring a new category into existence (there was a pre-existing group of radical feminists, but they weren’t defined as a category by the belief that trans women are not women, and in fact they still aren’t, since not all radical feminists hold that belief). So, to decide whether TERF is a slur we need to ask some other questions.

Do the people the word is applied to either use it to describe themselves or accept it when others use it to describe them?

Both parts of this question are important. If a group of people voluntarily use a word to describe themselves, then—on the assumption that people don’t generally slur their own group—you might conclude the word isn’t a slur. However, this does not allow for the possibility that a term might be a marker of identity and solidarity when used within the group, while remaining a slur if it’s used to/about the group by outsiders. (The classic example is the solidary use of the N-word among (some) Black people: it doesn’t make it OK for white people to use it. ‘Dyke’ for ‘lesbian’ is another example: fine if you are a lesbian, suspect if you aren’t. ) There are also jocular, ironic and self-mocking uses which don’t undermine the status of a word as a slur (women friends might refer to themselves in private as ‘sluts’ or ‘bitches’, but they wouldn’t accept being described in those terms in public or by non-intimates).

With TERF, I’d say the answer to both parts of the question is ‘no’. There may be people who use TERF ironically/self-mockingly in private, but I’m not aware of any who publicly define themselves as TERFs, and it’s common for those who are called TERFs by others to reject the label. Note that these observations concern attitudes to the word: there are certainly some feminists who publicly affirm the belief mentioned by Juno Dawson, that trans women are not women, but they may still deny being TERFs. This suggests they see TERF in the same way members of a certain ethnic group might see an ethnic slur: ‘yes, I am a member of the group you mean, but no, I do not accept the implications of the name you’re calling it by’. Which brings me to the next question:

Do the people the word is applied to regard it as a slur (e.g. do they describe it explicitly as a slur, protest against its use, display offence/distress when it is used)?

For some writers, a ‘yes’ to this question is enough on its own to make a word a slur. Luvell Anderson and Ernie Lepore argue that

…no matter what its history, no matter what it means or communicates, no matter who introduces it, regardless of its past associations, once relevant individuals declare a word a slur, it becomes one [emphasis in original]

What these writers are trying to account for is the fact that labels which were previously considered acceptable, or even polite, can get redefined as slurs (examples include ‘Negro’ and ‘coloured’), and the reverse may also happen (‘Black’ was not always acceptable, and ‘queer’ used to be unambiguously a slur). This isn’t a matter of what the term means (the literal meaning of ‘Black’ and ‘Negro’ is the same), but rather depends on the perceptions of ‘relevant individuals’ (members of the target group) at a particular point in time. If they declare a term offensive, then it’s offensive: it’s idle for non-members of the group to tell them they have no business taking offence.

On this criterion, TERF is indisputably a slur. Many individuals who have been described as TERFs have called it a slur, protested against its use (witness the complaints about Juno Dawson’s column) and explicitly said that it offends them. But I’m reluctant to make that the sole criterion. I agree that for something to be a slur it’s necessary for members of the target group to regard it as offensive, but I’m not sure that’s a sufficient condition (and what do you do about cases where the target group is split? ‘Queer’, for instance, divides opinion in the LGBT community).

As a sociolinguist (unlike the writers I’ve been referencing), I’m also dissatisfied with the implication that members of a group just arbitrarily and randomly decide that, for instance, ‘queer’ has ceased to be a slur or ‘Negro’ has now become one. I think these developments can be related to the changing social and political contexts in which words are used (for instance, the context for the ‘unslurring’ of ‘queer’ was the surge of radical activism prompted by the HIV-AIDS epidemic). Perceptions of words have to be seen in relation to what the words are being used to do, either by the group itself or by its opponents. So another question I would want to ask is,

What speech acts is the word used to perform?

If a word is just a neutral description, you might expect it to be used mainly for the purpose of describing or making claims about states of affairs. If it’s a slur, you’d also expect it to be used for those purposes, but in addition you might expect to see it being used in speech acts expressing hatred and contempt, such as insults, threats and incitements to violence. (By ‘insults’ here, incidentally, I don’t mean statements which are insulting simply because they use the word in question, but statements which say something insulting about the group, e.g. ‘they’re all dirty thieves’.)

There’s evidence that TERF does appear in insults, threats and incitements. You can read a selection of examples (mostly taken from Twitter, so these were public communications) on this website, which was set up to document the phenomenon. Here are a small number of items from the site to give you a sense of what this discourse looks like:

you vile dirty terf cunts must be fuming you have no power to mess with transfolk any more!

I smell a TERF and they fucking stink

if i ever find out you are a TERF i will fucking kill you every single TERF out there needs to die

why are terfs even allowed to exist round up every terf and all their friends for good measure and slit their throats one by one

if you encounter a terf in the wild deposit them in the nearest dumpster. Remember: Keeping our streets clean is everyone’s responsibility

Precisely because it was set up to document uses of TERF as a slur, this site does not offer a representative sample of all uses of the term, so it can’t tell us whether insulting/threatening/inciting are its dominant functions. It does, however, show that they are among its current functions. It also points to another relevant question:

What other words does the word tend to co-occur with?

It’s noticeable that on the website I’ve linked to, TERF quite often shows up in the same tweet as other words whose status as slurs is not disputed, like ‘bitch’ and ‘cunt’. Other words that occur more than once or twice in these tweets include ‘disgusting’, ‘ugly’, ‘scum’ and a cluster of words implying uncleanness (‘smell’, ‘stink’, ‘garbage’, ‘filth’)—which is also a well-worn theme in racist and anti-Semitic discourse.

One of the clues we use to infer an unfamiliar word’s meaning in context is our understanding of the adjacent, familar words; the result is that over time, recurring patterns of collocation (i.e. the tendency for certain words to appear in proximity to one another) have an influence on the way the word’s meaning evolves. The examples on the website are too small and unrepresentative a sample to generalise from, but if the collocations we see there are common in current uses of TERF, that would not only support the contention that it’s a slur, it might also suggest that the word could become increasingly pejorative.

In summary: TERF does not meet all the criteria that have been proposed for defining a word as a slur, but it does meet most of them at least partially. My personal judgment on the slur question has been particularly influenced by the evidence that TERF is now being used in a kind of discourse which has clear similarities with hate-speech directed at other groups (it makes threats of violence, it includes other slur-terms, it uses metaphors of pollution). Granted, this isn’t the only kind of discourse TERF is used in, and it may not be the main kind. But if a term features in that kind of discourse at all, it seems to me impossible to maintain that it is ‘just a neutral description’.

I believe in open debate on politically controversial issues, so I’m not suggesting the views of either side should be either censored or protected from criticism. My point is that when one of the key terms used in the argument has become a slur, it is no longer fit for any other purpose, and the time has come to look for a replacement.

• Dirty dog, for one

• Dirty rat, e.g.

• Dirty rotten scoundrel, e.g.

• Lying thief, e.g.

• White trash, e.g.

• 28 Talk like a toper

• A mark over the minims

• Affront

• All-too-common a campaign tactic

• Animadversion

• Arc on a music score

• Arc on a score

• Arced line connecting two musical notes

• Asperse

• Aspersion

• Aspersion, e.g.

• Bad-mouth

• Belittling comment

• Belittling remark

• Below-the-belt comment

• Bigot’s comment

• Bigot’s remark

• Bit of a loaded conversation?

• Bit of bigotry

• Bit of defamation

• Bit of dirty campaigning

• Bit of mudslinging

• Bit of slander

• Bit of slung mud

• Calumniate

• Calumny

• Campaign tactic

• Case of mud-throwing

• Cast aspersions on

• Curve between musical notes

• Curved line connecting musical notes

• Curved line directing a musician to connect notes together smoothly

• Curved line, in music

• Curved mark on a score

• Curved score mark

• Dastard’s remark

• Defamation of character

• Defamatory remark

• Defamatory statement

• Defame

• Derogatory comment

• Derogatory remark

• Diction impediment

• Diction problem

• Dig

• Dirty crack

• Disparage

• Disparagement

• Disparaging comment

• Disparaging remark

• Disparaging word

• Disrespectful comment

• Drag through the mud

• Drop a letter?

• Drop words

• Drunk’s tip-off

• Elide

• Elide, as vowels

• Enunciate poorly

• Epithet

• Evidence of drunkenness

• Fail to enunciate

• Fail to enunciate, in a way

• Finish off drink noisily, and speak indistinctly (4)

• Garble

• Give away being smashed

• Hardly a compliment

• Hateful word

• Indistinct speech

• Innuendo

• Insinuation

• Insult

• Insult in bad taste

• Insulting comment

• Insulting innuendo

• Insulting remark

• It ties notes together, in music

• Join notes

• Legato effect

• Legato indicator

• Libel, e.g.

• Libelous claim

• Libelous remark

• Lush way of speaking?

• Malign

• Many a campaign tactic

• Mean comment

• Mean words

• Mispronounce

• Mudslinger’s specialty

• Mudslinger’s utterance

• Mumble

• Music marking

• Music symbol

• Music-score mark

• Music-score marking

• Musical ligature

• Musical mark

• Musical phrase mark

• Musical sign

• Musical symbol that connects notes

• Musical-phrase connector

• Nasty comment

• Nasty name to call someone

• Nasty remark

• Offensive comment

• Offensive reference

• Phonetic elision

• Politically incorrect utterance

• Potentially slanderous remark

• Pronounce indistinctly

• Pronounce poorly

• Pronounce poorly, perhaps

• Put down

• Putdown, as between players

• Reveal intoxication

• Run together

• Run words together

• Say Offisher, I am completely shober, e.g.

• Say Offisher, I am shober, e.g.

• Say unclearly

• Scandalize

• Score connector, in music

• Score line

• Score mark

• Score marking

• Shay shomething

• Show evidence of tippling

• Shpeak like this

• Shpeak thish way

• Slanderous remark

• Slide over

• Slide over, as words

• Slight

• Slight verbally

• Sling mud at

• Sling mud at, say

• Smear

• Sot’s speech problem

• Sound like you’ve had a few too many

• Sound sozzled

• Speak after downing a bottle of rum

• Speak after one too many

• Speak carelessly

• Speak drunkenly

• Speak ill of

• Speak indistinctly

• Speak like a sot

• Speak like a tosspot

• Speak like the inebriated

• Speak poorly

• Speak poorly of, or speak poorly

• Speak sloppily

• Speak thickly

• Speak unclearly

• Speech problem

• Stain

• Talk drunkenly

• Talk fast, maybe

• Talk like a boozehound

• Talk like a drunk

• Talk like a lush

• Talk like a sot

• Talk like a toper

• Talk like a tosspot

• Talk like thish

• Talk like thish, shay

• Talk sloppily after a few drinks

• Tie over, in music

• Tying-over line, in music

• Ugly put-down

• Ugly remark

• Unclear utterance

• Unkind word

• Utter indistinctly

• Utter unclearly

• Verbal affront

• Verbal attack

• Verbal black eye

• Verbal punch

• Vilipend

• Vocal evidence of intoxication

• What an arc denotes, in music

• What drunk rocker will do

• What drunks do

• What the drunkard often does

• A blemish made by dirt

• (music) a curved line spanning notes that are to be played legato

• A disparaging remark

Abstract

Although there seems to be an agreement on what slurs are, many authors diverge when it comes to classify some words as such. Hence, many debates would benefit from a technical definition of this term that would allow scholars to clearly distinguish what counts as a slur and what not. Although the paper offers different definitions of the term in order to allow the reader to choose her favorite, I claim that ‘slurs’ is the name given to a grammatical category, and I consequently trace a difference in kind between slurs and other kinds of group pejoratives. I rely on a novel approach to slurs that characterizes them based on their membership to a particular kind of register category, an often neglected sociolinguistic notion determining the social contexts in which registered terms are expected, tolerated or unacceptable. The paper also points out to the close link between words registered as [+derogatory] (slurs) and their usage in the context of dominance relations of different kinds between users and recipients of slurs. By pointing out to this link I hope to underscore the political significance of slur usage, as well as to contribute further to the explanation why slurs are so damaging and unacceptable in most social contexts.

Access options

Buy single article

Instant access to the full article PDF.

39,95 €

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Notes

-

Williamson (2009).

-

See Ashwell (2016) for doubts on the status of these as slurs.

-

I won’t attempt here to provide a definition of ‘meaning’. I am using the term in opposition of ‘use’ and in this contrast, ‘meaning’ could be as well truth-conditional content, that plus conventional implicature or semantic presuppositions, or that plus an expressive dimension.

-

When it comes to slurs, in many countries, this entitlement to offense can even impact on legislation, allowing individuals to initiate legal actions against speakers using these expressions (Kennedy (2002)). See also the distinction between actual, warranted and rational offense in Bolinger (2017): offense can be rational if hearers are epistemically justified in taking offense, and warranted if the offense is morally justified.

-

This should be clear by now: this does not prevent speakers form making slurring remarks using these expressions. I am just saying that the words in themselves are not slurs. However, some of these descriptions or expressions can crystallize as slurs after reiterated slurring use. ‘Limey’ first described the habit of British sailors arriving to North America of sucking limes to prevent scurvy, and is now a slur for British in general. [Example by Richard (2008)].

-

Bach, unpublished.

-

I thank Ram Neta for this example.

-

Oxford Dictionary of English.

-

By ‘literally’ I mean the sense in which Jeshion (2013) uses this term.

-

I thank the anonymous referee for warning me about this problem.

-

Graff Fara (2000).

-

See Williamson (2009, 2010), Whiting (2013) and Copp and Sennet (2015).

-

Notice that the reference of the slur is not dependent on the reference on the neutral counterpart; although some authors may push forward the requisite of the existence of a neutral counterpart for a pejorative to count a slur, I believe that the requirement of group neutrality is a clearer anchor for the relation. See Ashwell (2016) for a critique of the requirement of a neutral counterpart. I thank the anonymous referee for pointing me in the direction of a better clarification of this point.

-

See Haslanger (2012).

-

Again, in the literal use described by Jeshion (2013).

-

See Ashwell (2016) for arguments on why this is not a good idea.

-

See Diaz-Legaspe, Liu, and Stainton (2019) for details.

-

Halliday (1973) and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004). See Predelli (2013, ch. 5) for its use in philosophy of language.

-

Notice that register does not dote registered words with the ability to convey an extra content above their truth-conditional content or to express emotions or attitudes.

-

The expression ‘conversational context’ refers to a situation singled out by social components: conversational parties and their kind of relation, medium, type of interaction, physical setting, previous conversation, etc.

-

Following Matsuda (1993, pp. 24–26) this would be an expected reaction: the abuse received from Ss (or even from some Ss) cause Gs to treat all Ss with suspicion in the best case, and with retaliative negative emotions in the worst.

-

I thank the anonymous referee to point to me to this paradigmatic example.

-

See for example Skinner (2008), Pettit (1997), Lovett (2010) and Honohan (2014).

-

I thank the anonymous referee for this example.

-

Online Etymology Dictionary.

-

For a difference between marginalizing and normalizing slurs see Diaz-Legaspe (2018).

-

Bergen (2016, ch.10) and Nunberg (2018).

-

Consider ‘fuck’, apparently rooted in a German word for ‘strike’ or ‘move back and forth’. One of its first appearances goes back to 16th century, in a manuscript of Cicero’s De Oficiis, where an annotation by a monk reads “O d fuckin Abbot”. Most likely, the author of the comment intended to express his extreme dismay, but since using the word ‘damned’ was forbidden due to religious implications, he preferred this other word. The expression got its connotation from its hinted relation to the other that was tabooed back then. (Mohr 2013). Bergen (2016) adds that pejoratives, profanities and expletives are for the most part based on sexual, religious, bodily or social aspects of human life.

-

Diaz-Legaspe and Stainton, (2018).

-

There are cases in which the referent of the slur is not part of the conversation: non-Jewish interlocutors that use the term ‘kike’ are surely not placing one another in any inferior position. Instead, they are placing someone else in that role, even if that person/s is not present: whoever they are referring to with the term ‘kike’. This differs significantly from a second person pronoun like ‘Usted’, which is always used to address the recipient within the conversation. I thank the anonymous referee for this observation.

-

See Popa-Wyatt and Wyatt (2018) for an approach to slur usage as a speech act that alters conversational roles by disbalancing power.

-

See Bergen (2016).

-

See Bolinger (2017).

References

-

Ashwell, L. (2016). Gendered slurs. Social Theory and Practice,42(2), 228–239.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Bach, K. (2018). Loaded words: On the semantics and pragmatics of slurs. In D. Sosa (Ed.), Bad words: Philosophical perspectives on slurs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

-

Bach, K. Loaded words: on the semantic and pragmatics of slurs. Pacific APA, San Diego, April 19, 2014 (unpublished).

-

Bergen, B. K. (2016). What the F: What swearing reveals about our language, our brains, and ourselves. New York: Basic Books.

Google Scholar

-

Bolinger, R. J. (2017). The pragmatics of slurs. Noûs,51(3), 439–462.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Copp, D., & Sennet, A. (2015). What kind of a mistake is it to use a slur? Philosophical Studies,172(4), 1079–1104.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Diaz-Legaspe, J. (2018). Normalizing slurs and out-group slurs: The case of referential restriction. Analytic Philosophy,59(2), 234–255.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Diaz-Legaspe, J., Liu, Ch. & Stainton, R. J. (2019). Meaning Pluralism, Register and Slurs. Mind and Language (forthcoming).

-

Diaz-Legaspe, J., & Stainton, R. J. (2018). Slurs and warm-hearted uses. Manuscript. University of Western Ontario (unpublished).

-

Eidelson, B. (2015). Discrimination and disrespect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Graff Fara, D. (2000). Shifting sands: an interest-relative theory of vagueness. Philosophical Topics,28(1), 45–81.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Halliday, M. A. K. (1973). Explorations in the functions of language. London: Edward Arnold.

Google Scholar

-

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3d ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Google Scholar

-

Haslanger, S. (2012). Resisting reality: Social construction and social critique. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Hom, C. (2008). The semantics of racial epithets. Journal of Philosophy, 105(8), 416–440.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Hom, Ch. (2012). A puzzle about pejoratives. Philosophical Studies,159(3), 383–405.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Honohan, I. (2014). Domination and migration: An alternative approach to the legitimacy of migration controls. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy,17(1), 31–48.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Jeshion, R. (2013). Expressivism and the offensiveness of slurs. Philosophical Perspectives,27(1), 231–259.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Kennedy, R. (2002). Nigger: The strange career of a troublesome word. New York: Vintage.

Google Scholar

-

Lovett, F. (2010). A general theory of dominance and justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Matsuda, M. J. (1993). Words that wound: critical race theory, assaultive speech, and the First Amendment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Google Scholar

-

Mohr, M. (2013). Holy sh*t: a brief story of swearing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

-

Nunberg, G. (2018). The social life of slurs. In Daniel Fogal, Daniel W. Harris, & Matt Moss (Eds.), New work on speech acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

-

Pettit, P. (1997). Republicanism: A theory of freedom and government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

-

Popa-Wyatt, M., & Wyatt, J. L. (2018). Slurs, roles and power. Philosophical Studies,175(11), 2879–2906.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Predelli, S. (2013). Meaning without truth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Richard, M. (2008). When truth gives out. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Skinner, Q. (2008). Freedom as the absence of arbitrary power. In Cécile Laborde & John W. Maynor (Eds.), Republicanism and political theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Google Scholar

-

Stern, D., & Mackenzie, H. (2016). Slurs, stereotypes and prejudice. Toronto: The Race Relation Division of the Government of Ontario.

Google Scholar

-

Whiting, D. (2013). It’s not what you said, it’s the way you said it: Slurs and conventional implicatures. Analytic Philosophy,54(3), 364–377.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Williamson, T. (2009). Reference, inference and the semantics of pejoratives. In A. Joseph & P. Leonardi (Eds.), The philosophy of David Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

-

Williamson, T. (2010). The use of pejoratives. In D. Whiting (Ed.), The later Wittgenstein on language. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper emerges as part of a research project conducted in Western University and partially financed by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada through grants to R. J. Stainton. It owes much to many people: the people in the slurs reading group of the Philosophy Department in Western University (Rob Stainton, Chang Liu, Jiangtian Li, Mike Korngut and Julia Lei), the Philosophy of Language and Linguistics group of the SADAF institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Eleonora Orlando and Andres Saab, Ramiro Caso, Nicolas Lo Guercio, Alfonso Losada, among others). Comments of another paper presented at the DEX VI Conference in UC Davis inspired and helped put the last details on the original ideas. I thank for this Adam Sennet, David Copp, Tina Rulli, Roberta Millstein, Adrian Currie, Ram Neta, and Tyrus Fisher.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

-

Institute of Philosophical Investigations, Argentinean Society of Philosophical Analysis, National Scientific and Technological Research Council (IIF-SADAF-CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina

Justina Diaz-Legaspe

-

University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

Justina Diaz-Legaspe

-

National University at La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

Justina Diaz-Legaspe

Authors

- Justina Diaz-Legaspe

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to

Justina Diaz-Legaspe.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diaz-Legaspe, J. What is a slur?.

Philos Stud 177, 1399–1422 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01259-3

Download citation

-

Published: 18 February 2019

-

Issue Date: May 2020

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01259-3

Keywords

- Slurs

- Derogatory language

- Discrimination

- Type-meaning

- Register

1. n проход; путь

2. n путь, подход, ключ

3. n канал

4. n проход, узкая улица, переулок; проулок

single pass — одиночный проход; однопроходный

5. n ущелье, дефиле, перевал, седловина

the height of the pass is … — высота перевала …

6. n воен. стратегическое укрепление, высота

7. n форт, крепость в горах

8. n фарватер, пролив, судоходное русло; судоходный канал

9. n рыбоход

10. n редк. брод, переезд

11. n горн. проход, пропускное отверстие; скат, ходок для людей

12. n метал. калибр или ручей валка

13. n горн. топографическая съёмка

14. n ав. неточно рассчитанный заход на посадку

15. n ав. прохождение, пролёт

close pass — пролёт на небольшом расстоянии, близкий пролёт

16. v идти; проходить; проезжать

17. v проходить мимо, миновать

18. v обгонять

19. v пройти, пропустить, прозевать

20. v не обратить внимания, пренебречь

pass me the butter, please — пожалуйста, передайте мне масло

21. v пройти незамеченным, сойти

22. v проходить, переезжать; пересекать, переправляться

23. v перевозить, проводить

24. v просовывать

25. v спорт. передавать, пасовать

pass on to — передавать; перекладывать на

26. v карт. пасовать, объявлять пас

27. v переходить

28. v превращаться, переходить из одного состояния в другое

29. v переходить или передаваться по наследству

pass round — передавать друг другу, пустить по кругу

30. v идти, проходить, протекать

31. v мелькнуть, появиться

32. v пройти; исчезнуть; прекратиться

33. v происходить, случаться, иметь место

34. v выхолить за пределы; быть выше

35. v ответить на действие тем же действием, обменяться

36. n сдача экзамена без отличия

37. n посредственная оценка; проходной балл, зачёт

38. n оценка «посредственно»

39. n пропуск, паспорт

pass law — закон о паспортах, паспортный закон

40. n пароль

41. n воен. разрешение не присутствовать на поверке; отпускной билет; увольнительная

leave pass — увольнительная записка; отпускное свидетельство

42. n воен. амер. краткосрочный отпуск

43. n воен. бесплатный билет; контрамарка

Синонимический ряд:

1. advance (noun) advance; approach; lunge; proposition; thrust

2. juncture (noun) contingency; crisis; crossroads; emergency; exigency; head; juncture; pinch; strait; turning point; zero hour

3. opening (noun) canyon; channel; crossing; defile; gap; gorge; opening; passageway; path; way

4. permit (noun) admission; authorization; furlough; license; order; passport; permission; permit; right; ticket

5. state (noun) condition; situation; stage; state

8. die (verb) cash in; conk; decease; demise; depart; die; drop; elapse; expire; go away; go by; leave; pass away; pass out; peg out; perish; pip; pop off; succumb

10. employ (verb) circulate; employ; expend; put in; spend; while away

11. enact (verb) adopt; approve; enact; establish; legislate; okay; ratify; sanction

14. go (verb) advance; fare; go; hie; journey; move; proceed; progress; push on; repair; travel; wend

15. happen (verb) befall; betide; chance; come; come about; come off; develop; do; fall out; go on; hap; happen; occur; rise; take place; transpire

18. neglect (verb) blink at; blink away; discount; disregard; elide; fail; forget; ignore; miss; neglect; omit; overleap; overlook; overpass; pass by; pass over; pretermit; skim; skim over; slight; slough over; slur over

20. pose (verb) impersonate; masquerade; pose; posture

22. pronounce (verb) announce; claim; declare; express; pronounce; state; utter

23. surpass (verb) beat; best; better; cap; cob; ding; eclipse; exceed; excel; outdo; outgo; outmatch; outshine; outstrip; overshadow; surpass; top; transcend; trump

24. tell (verb) break; carry; clear; communicate; convey; deliver; disclose; get across; give; impart; relinquish; report; send; spread; tell; transfer; transmit

Антонимический ряд:

come; disapprove; fail; initiate; note; notice; regard; repeal; retreat; return; start

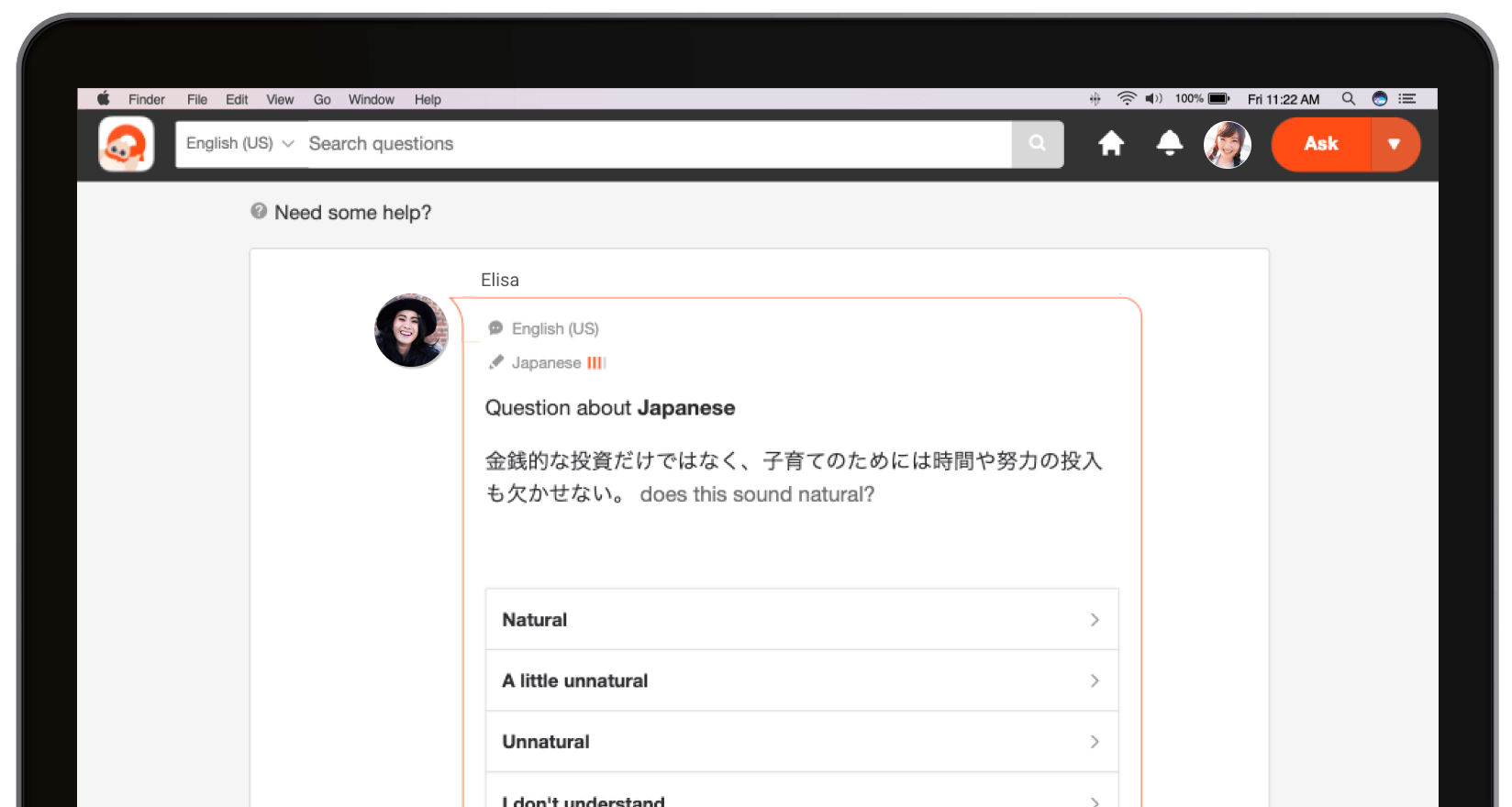

What’s this symbol?

The Language Level symbol shows a user’s proficiency in the languages they’re interested in. Setting your Language Level helps other users provide you with answers that aren’t too complex or too simple.

-

Has difficulty understanding even short answers in this language.

-

Can ask simple questions and can understand simple answers.

-

Can ask all types of general questions and can understand longer answers.

-

Can understand long, complex answers.

Sign up for premium, and you can play other user’s audio/video answers.

What are gifts?

Show your appreciation in a way that likes and stamps can’t.

By sending a gift to someone, they will be more likely to answer your questions again!

If you post a question after sending a gift to someone, your question will be displayed in a special section on that person’s feed.

Tired of searching? HiNative can help you find that answer you’re looking for.

CN: In-depth discussion of the usage and purpose of slurs and the common defenses for using slurs; discussion of racism, sexism, anti-gay bias, and classism.

Warning: There will be a couple of slurs written out in full in this article. They are written this way to maintain clarity in a purely educational piece. I made a point to limit how many slurs I used and to avoid using any slurs that would be particularly egregious for a person with my set of privileges to use.

“You shouldn’t say that word.”

At some point in our lives, we have all had the experience of someone telling us that a word or a phrase that we used is not okay. And if we’re being honest, a lot of the time, our reaction to this push back is, “Huh? What do you mean I can’t say that word?”

Within the world of social justice, there is a wide range of forms of critique of how to talk about, well, everything! Sometimes these critiques are actually about the content as opposed to the words used to describe it, other times the word themselves aren’t necessarily harmful but used in certain contexts, they uphold societal patterns that we’d rather do without.

In this article, I want to focus on a specific form of problematic language called slurs.

What Is a Slur?

A slur is a derogatory term used to describe people from marginalized groups.

A word is a powerful thing. What we call people can represent where we see ourselves in the power dynamic: Are you in charge, or are they? Are you a friend or a stranger? Are you warmly accepting of them or do you reject them? The language we use communicates what type of interaction we want to have and how we believe it is reasonable to behave. This social power exists in many words, but slurs have a power that’s much more damaging than typical insults or other hurtful language.

The purpose of a slur is to dehumanize, to other, and to enforce oppression against marginalized people. It’s a reminder that you, as a person, are defined only by the marginalized group that you’re part of, and that being part of that group makes you less important, less valuable. Receiving a slur communicates that because you are a member of this group, you are inherently dirty, bad and worthless.

Slurs are meant to encompass everything society says is wrong with people like you and those same slurs will be used to put the blame on you for the horrible treatment you receive because you are a [slur] and society says that [slurs] deserve to be treated that way.

What Are Examples of Slurs?

There are many slurs of varying levels of notoriety for every marginalized group and subgroup. If you’re interested in re-examining your language and in learning about more words you may want to choose to avoid, I’ve compiled links to lists of slurs and related offensive language specific to each of the following groups. Please click with caution if you find slurs about your own group upsetting.

Types of slurs

- Ethnic or racial slurs

- Religious slurs

- Classist slurs

- Ableist or sanist (relating to mental illness) slurs

- LGBT related slurs

- Fatphobic slurs

- Sexist slurs

A Slur is Not Just an Insult

It’s extremely important to distinguish a slur, a tool for oppression, from even a particularly nasty insult.

In Power Dynamics Part 2, we learned about how different levels of power in an interaction completely changes the nature of the action committed.

“…When a person of color says that black people can’t be racist to white people, what they mean is that a white person discriminating against a black person is supported by an entire societal structure of social, financial, and institutional power that is designed to make things easier for white people and actively difficult for black people… A black person discriminating against a white person is only supported by individual opinions, not entire systems. The potential impact of the same act on the two groups can be as different as having your life put in danger vs. feeling hurt and rejected.”

This principle is very relevant to the main differences between slurs and insults:

- An insult represents the personal opinion of the person delivering it, whereas a slur represents the opinion of the parts of society that have the most power.

- When you insult someone, your behavior is only supported by whatever immediate social support you have. A slur is supported by entire societal systems that are designed to punish the group the slur represents.

- An insult is directed at aspects of a specific person whereas a slur uses someone’s association with a group of people to insult them.

- Typically, the purpose of an insult is to hurt another person to some degree. The purpose of a slur is to undermine their humanity and reinforce their oppression.

Slurs Are Only Used to Describe Marginalized Groups

It’s important to note that because of these four qualifications, words that are meant to describe and insult privileged groups cannot be slurs. While it might sting more to be insulted based on a group you did not choose to be part of than to be insulted based on your behavior or something random, the insult won’t follow you into your ability to find work, your ability to get medical care, or just your ability to go through life without constant danger. A slur will. When you walk away from that one person insulting your group, you can return to the majority of people who don’t share that opinion. A recipient of the slur can never fully escape the social patterns the slur enforces.

For example, words used to insult white people like “white trash” or “cracker” are actually directed at poor white people. The dehumanization of low-income people makes it a slur, even though white people are the alleged target. These slurs also rely on racism to intensity their sting because they are meant to describe a white person who has failed at being a white person by being as poor as a black person.

Why Shouldn’t You Use Slurs?

In my transition from teenage-hood to adulthood, I knew the word “Bitch” was a swear in most communities but didn’t really understand the fuss about it from feminist circles. I didn’t particularly like the word, but I did use it on occasion, almost always to describe specific very unlikeable women.

It wasn’t until I was in my mid-twenties that I asked myself one day, what does “bitch” mean to me? What do I mean when I say it?

I considered my own definition carefully. I thought “bitch” described a woman who was loud, overbearing, temperamental, abrasive, and aggressive. I realized that I had just given myself a list of all the things women are taught they should never be and that most of the time when women are described using those same words, it is to undermine the legitimacy of their emotions or experience and blame them for their own suffering. I realized a “bitch” was everything a woman wasn’t supposed to be: outspoken, powerful, uncompromising, persistent, angry, and unwilling to cater her behavior to your feelings.

When someone calls me a bitch, they are telling me I’m failing at performing womanhood to society’s standard, and that my failure made me all the more deserving of cruelty.

That was the day that I stopped using the word “bitch” as an insult.

Your Privilege Keeps You in the Dark

As I discuss in Explaining Privilege Part 2, if you are a member of a more privileged group, the societal forces at play will make you less aware of the severity of the problems of corresponding marginalized groups, if you know about them at all. As a result, it’s common to be unaware of many of the words that are used as slurs against any given group. It’s even more common to know about the word, know about its problematic origins, and believe that the word has evolved into a version that is harmless.

Unfortunately, as long as that group’s identity is still used to oppress them in serious ways, using a word that insults their identity is still a problem.

If you read through the lists of slurs linked above, there’s a very good chance that you will read some and your reaction will be, “That’s a slur? No. There’s nothing wrong with that word. They’re just being oversensitive.”

If this happens to you, remember that these are words that will never be used to harm you. In fact, society has been designed to protect you from the harm the words do cause. It’s normal for you to not be aware that the word causes harm. But because the impact of the word lands on the marginalized group and never on you, the only way you have of knowing whether or not the word is a problem is based on what the marginalized group tells you. You have no other way of knowing except for listening to their experience of the word.

Oppressive language can go through a process of being reclaimed by the group it describes, which I’ll discuss more later, but that process is lead and determined by the marginalized group itself, which means if you’re unaware of the group’s general feelings about a word, you aren’t in a good position to evaluate whether or not it is still harmful to use it. You are in fact the least qualified to make that judgment call.

If the marginalized group tells you, “This word hurts me,” you lose very little by respecting their request to stop using it. Given such a low maintenance choice between hurting someone and not, why would you intentionally choose the first option?

Common Arguments to Defend the Use of Slurs

Despite it being a seemingly simple choice to listen when someone says you’re hurting them and to make a minor change to your behavior to accommodate that, there are a lot of arguments that pop up in defense of people using their favorite slurs.

But I don’t mean it like that.

One of the first lessons you learn as an ally for any cause is that intent is not magic. The fact that you did not intend to harm someone does not fix the fact that you did. Certainly, hurting someone on accident is less toxic than doing so intentionally, but the fact that it’s an accident doesn’t relieve you of the responsibility of apologizing and tending to the hurt of the harmed person and of prioritizing that care over tending to your own feelings of guilt.

You can’t control how your words impact a specific person, which means that even if you use a slur but “not like that,” you have no way of ensuring that the marginalized person hearing you use it knows that you don’t mean it “like that.” And if you’ve been explicitly told that the word is harmful but you use it anyways, any flexibility you’ve received for your good intentions will be quickly erased. When someone tells you something hurts them, it is not kind to continue to do that thing, no matter your intention behind it.

But the marginalized group gets to say [slur]. Why don’t I?

There is a long history of marginalized groups taking symbols of their oppression, reclaiming them, and using them to further their empowerment. Words like “bitch” and “queer” have been reclaimed by the groups they were used to punish, giving them a new range of connotations and increasing their usage. In the majority of cases, reclaimed language changes the meaning behind the slur from one of dehumanization to one of power and resilience. Where “bitch” used to represent the worst things a woman could be, for many it now represents something awesome and pride-worthy.

This kind of shift means that if there’s any lack of clarity in the context of its usage that the word is meant to mean something positive, it can easily slip back into the damage of a slur, and if it’s used intentionally as an insult, the process of reclamation is irrelevant because the purpose of its use was to harm.

But going back to the idea of what you mean when you say a slur, if a marginalized group is in the process of reclaiming a word used to harm them, and you, a person from the corresponding privileged group, try to use it with the new connotations, a marginalized person has no way of knowing which connotation you intend, whether you know there are contexts where it’s not okay to say that word, and whether you are safe to correct if your usage makes them uncomfortable. In their experience, they’ve encountered far more privileged people who haven’t considered anyone else’s feelings before they choose their words than privileged people who have educated themselves about why the word is harmful, who it hurts, and what contexts are appropriate to us it.

It’s also important to note that reclamation or not, there are slurs that you, the privileged person, should never use regardless of the context. And if you are unsure about which slurs those are, I would err on the side of whatever action that allows you to avoid using slurs.

But other words don’t have the same sting!

It’s true that a lot of the words offered to replace mainstream slurs don’t have the same feeling of satisfaction when you use them and they can sound weak or boring in comparison. The reason that slurs feel more powerful and more damaging is because they are. Using decades of oppression and the culture-wide support of that oppression as a weapon to insult an individual (and insult the entire group they are part of by association) is more powerful and it’s also way more unethical than a simple insult. Would you rather have that extra feeling of satisfaction in the moment but harm a group of people that aren’t the target of your anger, or spend the time to find a replacement word that requires a little extra emotional management on your part but doesn’t harm an already vulnerable group?

But what if they are a [slur]?

While you might feel like these powerful words perfectly capture the essence of a specific person you dislike, it’s important to remember that dehumanization is an integral part of the meaning of slurs. When you say, “They are a [slur]” you’re actually saying “They are not human and they don’t deserve to be treated as one.” And if you find yourself wanting to assert that a person is not human, no matter how poor their behavior, it’s time to take a step back and reflect on why you feel the need to dehumanize someone in order to validate your anger if you’re wanting to be a good ally on this front.

But I’m using it against someone who isn’t part of that group

Even when you use a slur against a person who is not part of the group the slur originally was meant to describe, it still carries the harm of a slur because you are insulting this person for having traits that somehow associate them with a marginalized group. A common example of this problem is that men with stereotypically feminine traits will get called slurs that are meant to describe women or gay men. Effeminate men are not women and they aren’t necessarily gay but using those slurs against them means that just that the association with women and gay men is enough of a reason to dehumanize them according to society.

But you don’t have a problem with curse-words. Why are slurs any different?

Profanity is typically defined as words that segments of society have decided are offensive or inappropriate. They are usually used to express anger or add emphasis. Because swear words are typically defined by how much society objects to them, what words are considered swears often change from country to country or even between different communities. Well-known slurs are often handled in a similar way to swears in terms of censorship or social rules around when it’s “acceptable” to say them. But many slurs are not considered swears because the group in power that has more influence over whether a word is considered socially acceptable or not, typically argues for a slurs’ normalization and social acceptance.

But shouldn’t we just stop insulting each other altogether?

The argument here isn’t that you should never result to name-calling in an argument or that you should never express anger through the use of insults. In fact, allowing marginalized groups to openly express their anger without having to frame it in a productive way that benefits corresponding privileged groups is a right we’re often denied, which makes the occasional insulting rant a radical thing to do.

But the real takeaway in learning about slurs is that insults are not all created equal, nor do they all do the same amount of damage. Slurs hurt more than just the person you use it against, which causes damage of a kind that you don’t want to be part of if you support the empowerment of marginalized groups. Whether or not you should use name-calling ever is an entirely different question from whether you should use slurs, because the intention, the purpose, and the consequences are not the same for both categories.

But shouldn’t we be focusing on more important problems?

It’s easy to feel like putting so much focus on the words we use is a trivial use of our time and that it takes our focus away from the bigger “more important” issues. But our language is a reflection of our cultural attitudes and our history.

Oppression survives as long as there are institutions and people to uphold it. When a word comes from an oppressive history, by using it today, we’re carrying forward old toxic social patterns used to enforce widespread suffering, into the present and interacting with them as a normal part of life, instead of rejecting and replacing them with something that doesn’t hurt people for arbitrary reasons.

Language is just one piece of these much larger societal problems, but it is also one that is in our direct control. Eradicating racism is a massive endeavor, and one that no one person will ever be able to accomplish on their own but you do have the power to change the way you speak. Not only does this make a positive difference in demonstrating good behavior for others and avoiding harming marginalized people you interact with, but it also encourages you to think critically about your own beliefs about the oppressed group you’re trying to help.

Slurs might be a symptom, not the cause of oppression, but they are a symptom that will lead you to the source of the dysfunction.

The Privilege of Saying What You Want

One of the things that makes it so uncomfortable to be told that you shouldn’t say certain words is that our culture highly promotes the idea that you should be able to say whatever you want whenever you want. Or at least, our culture promotes that to you proportionally to the amount of privilege you have, with white cis men typically holding that belief with the most strength.

If you believe speaking your mind in real-time without fear is a virtue, being asked to avoid saying something to cater to someone else’s request can sound like disrespect, and ignoring their request can seem like you’re standing up for yourself and what you believe in.

This mental pattern is also really common among folks that are oppressed in one way but not in other ways. If you have put in work to undo the conditioning your oppression forced on you, and one of those traits you were forced into was to walk on eggshells around others, it sounds like the same force at work when you’re asked to do the same thing for a different marginalized group.

The important difference here is the relative levels of power. If a person with less power than you is asking you to change your language, they are not censoring or silencing you because they don’t have the power to do that. They have very little ability to impact your behavior at all. You still have full control over what words you choose to use. You’ve just received social resistance to a behavior that negatively impacts other people.

The truth is, even the most outspoken among us will be perfectly willing to change how we speak when we’re interacting with someone with substantially more power than we have. If you met a celebrity, or a famous politician, or a member of royalty, would you lean on your habit of brutal honesty or would you reign yourself in out of respect? Do you say whatever you want to your boss? To your grandmother? To your teachers?

People in positions of power actually have the ability to potentially censor or silence us but we don’t tend to think of our minor adaptations of language and tone for them as censorship because we’ve been taught that it’s important to graciously offer consideration to powerful people. We’ve been taught that their needs truly matter. We only feel like it’s censorship when it’s for the needs of people we’ve deemed “not important.”

To replace that pattern, I’m offering the idea that it is not actually ethical or righteous to say exactly what you want to say whenever you want to say it. It is kind and respectful to consider the needs of other people when you talk. And it is especially important to consider the needs of people who have less power than you do.

To be clear, the ability to stand up for yourself is an important skill and it will always be important to ensure your own well being and to assert your own boundaries. But never have I run into an instance where the best possible thing someone could do to care for themselves was to use a slur against someone more vulnerable than them.

The Process of Replacing Your Language

Re-training yourself to use new language takes time and practice and some slurs are easier to weed out of your vocabulary than others. Here are a few strategies to keep in mind that should help along this process.

Focus on Accuracy

In addition to disability activism not yet reaching the awareness of mainstream activism circles, many of the ableist and sanist words that disabled communities have flagged as still causing them harm are so ingrained in our daily usage and so common that even if you’re fully on board with reducing your usage, it can be really hard to stop.

I have one main strategy in combatting frustration around removing slurs or other problematic language from your vocabulary: Focus on accuracy.

“Stupid” is on the list of words that much of the disabled community has asked everyone not to use. Its origins lie in descriptions of people with cognitive disabilities, which means that calling someone “stupid” includes the connotation that they cannot control their behavior but you’re punishing them for it anyways.

One of the things that makes it so freaking hard to stop saying “stupid” is that there is no single go-to replacement word because we use it to mean so many things.

When you call someone “stupid” you could be saying…

- This person is incompetent

- This person is acting illogically

- This person is behaving in a way that I don’t understand

- This person is uneducated

- This person is not worthwhile

- This person is frustrating me

- This person is willfully ignorant

- This person is unlikeable

As a writer, I want to ensure I’m picking the best possible words to convey my meaning as accurately as possible. I find it much easier to let go of common words like “stupid” when I focus on the fact that it’s an unspecific and inaccurate word anyways. I can find a word that’s better by saying what I actually mean instead.

“Why do I have to fill out this paperwork again, this is so… pointless!”

“The return policies at this store make no sense!”

“My coworker is so incredibly bad at her job. I can’t trust her to do anything right.”

This strategy comes with the added benefit of noticing and reflecting on what your real beliefs are about a given subject or why something upsets you, rather than just flying past these details in your general frustration.

Hold Yourself Accountable

Changing your language also means replacing an old habit with a new one, which typically involves plenty of mistakes before it’s solid. If you mess up in front of someone who would be harmed from your mistake, apologize in a quick straight forward way and correct yourself. You want to avoid making a big show of how sorry you are or how hard you are trying. Acknowledge that you’ve messed up and move on. This strategy prevents you from centering yourself in a conversation where you are not in any way the victim.

If you mess up in front of someone the mistake doesn’t harm, you should still correct yourself. If you want to include them in the process for accountability, you could try to say, “I’m trying to teach myself to stop saying x and say y instead,” and invite them to start the practice as well.

Reinforce Your Neural Pathways

Every habit you have is physically carved out in a neural pathway in your brain. Your brain finds it easier to send signals along the largest, strongest pathways, which are the ones you’ve used the most. This means that if you have a new habit with a tiny little neural pathway, your brain is going to have to work harder to use it, and it’ll want to default to the old stronger one.

If you’re feeling frustrated or awkward with the new language, remember that you already have a very strong neural pathway devoted to using the old word, which means that it is physically easier for your brain to cue you to say the old word. It will take time to develop a new neural pathway that is strong enough to overpower the old pathway every time. The only way to make a neural pathway stronger is by using it as much as possible. Eventually, you won’t need to exert so much conscious effort to make sure you say the right thing, it’ll just happen automatically. But that will only happen if you put in the work now.

The Kinder Thing to Do

If you’ve ever had resistance to being told that a word you use is a slur or that you shouldn’t use certain language, chances are I’ve addressed the reason above.

But regardless of where that resistance is coming from, this issue boils down to the idea that when someone says, “This action hurts me,” it is kind and considerate to listen to them and to adjust your behavior if it is in your power to do so.

There are absolutely going to be times when someone says “this action hurts me,” and you’re going to have to decide not to give them what they need, either because it’s not something you control, it’s fundamentally in conflict with your system of ethics, or because the action harms you in a significant way.

But when the request is, “Please avoid using this word,” the adjustment needed on your end is so small, and the harm that you’ll be preventing is significant enough that it just makes sense to respect requests for language changes, especially for people who have less power than you do and who have to struggle a lot harder than you do through no fault of their own.

About the writer: Kella Hanna-Wayne is the creator, editor, and main writer for Yopp. In addition to creating a collection of educational resources for social justice, she works as a freelance writer specializing in content about her experience with disability, chronic illness, mental health, and trauma. Her work has been published in Ms. Magazine blog, The BeZine, Betty’s Battleground, and Splain You a Thing. You can find her @KellaHannaWayne on Facebook, Twitter, Medium, and Instagram.

At Yopp we’re dedicated to providing educational material for social

justice

that emphasizes the individual experience of lived oppression and helps you

understand the whole picture instead of memorizing do’s & don’ts.