For the international (civil) aviation organization (ICAO) spelling alphabet, see NATO phonetic alphabet.

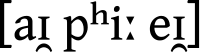

| International Phonetic Alphabet | |

|---|---|

«IPA» in IPA ([aɪ pʰiː eɪ]) |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet – partially featural |

|

Time period |

1888 to present |

| Languages | Used for phonetic and phonemic transcription of any language |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Palaeotype alphabet, English Phonotypic Alphabet

|

The official chart of the IPA, revised in 2020

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standardized representation of speech sounds in written form.[1] The IPA is used by lexicographers, foreign language students and teachers, linguists, speech–language pathologists, singers, actors, constructed language creators, and translators.[2][3]

The IPA is designed to represent those qualities of speech that are part of lexical (and, to a limited extent, prosodic) sounds in oral language: phones, phonemes, intonation, and the separation of words and syllables.[1] To represent additional qualities of speech—such as tooth gnashing, lisping, and sounds made with a cleft lip and cleft palate—an extended set of symbols may be used.[2]

Segments are transcribed by one or more IPA symbols of two basic types: letters and diacritics. For example, the sound of the English letter ⟨t⟩ may be transcribed in IPA with a single letter: [t], or with a letter plus diacritics: [t̺ʰ], depending on how precise one wishes to be. Slashes are used to signal phonemic transcription; therefore, /t/ is more abstract than either [t̺ʰ] or [t] and might refer to either, depending on the context and language.[note 1]

Occasionally, letters or diacritics are added, removed, or modified by the International Phonetic Association. As of the most recent change in 2005,[4] there are 107 segmental letters, an indefinitely large number of suprasegmental letters, 44 diacritics (not counting composites), and four extra-lexical prosodic marks in the IPA. Most of these are shown in the current IPA chart, posted below in this article and at the website of the IPA.[5]

History[edit]

In 1886, a group of French and British language teachers, led by the French linguist Paul Passy, formed what would be known from 1897 onwards as the International Phonetic Association (in French, l’Association phonétique internationale).[6] Their original alphabet was based on a spelling reform for English known as the Romic alphabet, but to make it usable for other languages the values of the symbols were allowed to vary from language to language.[note 2] For example, the sound [ʃ] (the sh in shoe) was originally represented with the letter ⟨c⟩ in English, but with the digraph ⟨ch⟩ in French.[6] In 1888, the alphabet was revised to be uniform across languages, thus providing the base for all future revisions.[6][7] The idea of making the IPA was first suggested by Otto Jespersen in a letter to Passy. It was developed by Alexander John Ellis, Henry Sweet, Daniel Jones, and Passy.[8]

Since its creation, the IPA has undergone a number of revisions. After revisions and expansions from the 1890s to the 1940s, the IPA remained primarily unchanged until the Kiel Convention in 1989. A minor revision took place in 1993 with the addition of four letters for mid central vowels[2] and the removal of letters for voiceless implosives.[9] The alphabet was last revised in May 2005 with the addition of a letter for a labiodental flap.[10] Apart from the addition and removal of symbols, changes to the IPA have consisted largely of renaming symbols and categories and in modifying typefaces.[2]

Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for speech pathology (extIPA) were created in 1990 and were officially adopted by the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association in 1994.[11]

Description[edit]

The general principle of the IPA is to provide one letter for each distinctive sound (speech segment).[note 3] This means that:

- It does not normally use combinations of letters to represent single sounds, the way English does with ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩ and ⟨ng⟩, or single letters to represent multiple sounds, the way ⟨x⟩ represents /ks/ or /ɡz/ in English.

- There are no letters that have context-dependent sound values, the way ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ in several European languages have a «hard» or «soft» pronunciation.

- The IPA does not usually have separate letters for two sounds if no known language makes a distinction between them, a property known as «selectiveness».[2][note 4] However, if a large number of phonemically distinct letters can be derived with a diacritic, that may be used instead.[note 5]

The alphabet is designed for transcribing sounds (phones), not phonemes, though it is used for phonemic transcription as well. A few letters that did not indicate specific sounds have been retired (⟨ˇ⟩, once used for the «compound» tone of Swedish and Norwegian, and ⟨ƞ⟩, once used for the moraic nasal of Japanese), though one remains: ⟨ɧ⟩, used for the sj-sound of Swedish. When the IPA is used for phonemic transcription, the letter–sound correspondence can be rather loose. For example, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are used in the IPA Handbook for /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/.

Among the symbols of the IPA, 107 letters represent consonants and vowels, 31 diacritics are used to modify these, and 17 additional signs indicate suprasegmental qualities such as length, tone, stress, and intonation.[note 6] These are organized into a chart; the chart displayed here is the official chart as posted at the website of the IPA.

Letter forms[edit]

Loop-tail ⟨g⟩ and open-tail ⟨ɡ⟩ are graphic variants. Open-tail ⟨ɡ⟩ was the original IPA symbol, but both are now considered correct. See history of the IPA for details.

The letters chosen for the IPA are meant to harmonize with the Latin alphabet.[note 7] For this reason, most letters are either Latin or Greek, or modifications thereof. Some letters are neither: for example, the letter denoting the glottal stop, ⟨ʔ⟩, originally had the form of a dotless question mark, and derives from an apostrophe. A few letters, such as that of the voiced pharyngeal fricative, ⟨ʕ⟩, were inspired by other writing systems (in this case, the Arabic letter ⟨ﻉ⟩, ʿayn, via the reversed apostrophe).[9]

Some letter forms derive from existing letters:

- The right-swinging tail, as in ⟨ʈ ɖ ɳ ɽ ʂ ʐ ɻ ɭ ⟩, indicates retroflex articulation. It originates from the hook of an r.

- The top hook, as in ⟨ɠ ɗ ɓ⟩, indicates implosion.

- Several nasal consonants are based on the form ⟨n⟩: ⟨n ɲ ɳ ŋ⟩. ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ŋ⟩ derive from ligatures of gn and ng, and ⟨ɱ⟩ is an ad hoc imitation of ⟨ŋ⟩.

- Letters turned 180 degrees for suggestive shapes, such as ⟨ɐ ɔ ə ɟ ɓ ɥ ɾ ɯ ɹ ʇ ʊ ʌ ʍ ʎ⟩ from ⟨a c e f ɡ h ᴊ m r t Ω v w y⟩.[note 8] Either the original letter may be reminiscent of the target sound (e.g., ⟨ɐ ə ɹ ʇ ʍ⟩) or the turned one (e.g., ⟨ɔ ɟ ɓ ɥ ɾ ɯ ʌ ʎ⟩). Rotation was popular in the era of mechanical typesetting, as it had the advantage of not requiring the casting of special type for IPA symbols, much as the sorts had traditionally often pulled double duty for ⟨b⟩ and ⟨q⟩, ⟨d⟩ and ⟨p⟩, ⟨n⟩ and ⟨u⟩, ⟨6⟩ and ⟨9⟩ to reduce cost.

-

An example of a font that uses turned small-capital omega, ⟨ꭥ⟩, for the vowel ⟨ʊ⟩. The symbol had originally been a small-capital ⟨ᴜ⟩.

-

- Among consonant letters, the small capital letters ⟨ɢ ʜ ʟ ɴ ʀ ʁ⟩, and also ⟨ꞯ⟩ in extIPA, indicate more guttural sounds than their base letters. (⟨ʙ⟩ is a late exception.) Among vowel letters, small capitals indicate «lax» vowels. Most of the original small-cap vowel letters have been modified into more distinctive shapes (e.g. ⟨ʊ ɤ ɛ ʌ⟩ from U Ɐ E A), with only ⟨ɪ ʏ⟩ remaining as small capitals.

Typography and iconicity[edit]

The International Phonetic Alphabet is based on the Latin script, and uses as few non-Latin letters as possible.[6] The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most letters would correspond to «international usage» (approximately Classical Latin).[6] Hence, the consonant letters ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨f⟩, (hard) ⟨ɡ⟩, (non-silent) ⟨h⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨k⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨p⟩, (voiceless) ⟨s⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨t⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨z⟩ have more or less the values found in English; and the vowel letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ correspond to the (long) sound values of Latin: [i] is like the vowel in machine, [u] is as in rule, etc. Other Latin letters, particularly ⟨j⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨y⟩, differ from English, but have their IPA values in Latin or other European languages.

This basic Latin inventory was extended by adding small-capital and cursive forms, diacritics and rotation. The sound values of these letters are related to those of the original letters, and their derivation may be iconic.[12] For example, letters with a rightward-facing hook at the bottom represent retroflex equivalents of the source letters, and small capital letters usually represent uvular equivalents of their source letters.

There are also several letters from the Greek alphabet, though their sound values may differ from Greek. The most extreme difference is ⟨ʋ⟩, which is a vowel in Greek but a consonant in the IPA. For most Greek letters, subtly different glyph shapes have been devised for the IPA, specifically ⟨ɑ⟩, ⟨ꞵ⟩, ⟨ɣ⟩, ⟨ɛ⟩, ⟨ɸ⟩, ⟨ꭓ⟩ and ⟨ʋ⟩, which are encoded in Unicode separately from their parent Greek letters. One, however – ⟨θ⟩ – has only its Greek form, while for ⟨ꞵ ~ β⟩ and ⟨ꭓ ~ χ⟩, both Greek and Latin forms are in common use.[13]

The tone letters are not derived from an alphabet, but from a pitch trace on a musical scale.

Beyond the letters themselves, there are a variety of secondary symbols which aid in transcription. Diacritic marks can be combined with IPA letters to add phonetic detail such as tone and secondary articulations. There are also special symbols for prosodic features such as stress and intonation.

Brackets and transcription delimiters[edit]

There are two principal types of brackets used to set off (delimit) IPA transcriptions:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| [ … ] | Square brackets are used with phonetic notation, whether broad or narrow[14] – that is, for actual pronunciation, possibly including details of the pronunciation that may not be used for distinguishing words in the language being transcribed, which the author nonetheless wishes to document. Such phonetic notation is the primary function of the IPA. |

| / … / | Slashes[note 9] are used for abstract phonemic notation,[14] which note only features that are distinctive in the language, without any extraneous detail. For example, while the ‘p’ sounds of English pin and spin are pronounced differently (and this difference would be meaningful in some languages), the difference is not meaningful in English. Thus, phonemically the words are usually analyzed as /ˈpɪn/ and /ˈspɪn/, with the same phoneme /p/. To capture the difference between them (the allophones of /p/), they can be transcribed phonetically as [pʰɪn] and [spɪn]. Phonemic notation commonly uses IPA symbols that are rather close to the default pronunciation of a phoneme, but for legibility or other reasons can use symbols that diverge from their designated values, such as /c, ɟ/ for affricates typically pronounced [t͜ʃ, d͜ʒ], as found in the Handbook, or /r/, which in phonetic notation is a trill, for English r even when pronounced [ɹʷ]. |

Other conventions are less commonly seen:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| { … } | Braces («curly brackets») are used for prosodic notation.[15] See Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for examples in this system. |

| ( … ) | Parentheses are used for indistinguishable[14] or unidentified utterances. They are also seen for silent articulation (mouthing),[16] where the expected phonetic transcription is derived from lip-reading, and with periods to indicate silent pauses, for example (…) or (2 sec). The latter usage is made official in the extIPA, with unidentified segments circled.[17] |

| ⸨ … ⸩ | Double parentheses indicate either a transcription of obscured speech or a description of the obscuring noise. The IPA specifies that they mark the obscured sound,[15] as in ⸨2σ⸩, two audible syllables obscured by another sound. The current extIPA specifications prescribe double parentheses for the extraneous noise, such as ⸨cough⸩ or ⸨knock⸩ for a knock on a door, but the IPA Handbook identifies IPA and extIPA usage as equivalent.[18] Early publications of the extIPA explain double parentheses as marking «uncertainty because of noise which obscures the recording,» and that within them «may be indicated as much detail as the transcriber can detect.»[19] |

All three of the above are provided by the IPA Handbook. The following are not, but may be seen in IPA transcription or in associated material (especially angle brackets):

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| ⟦ … ⟧ | Double square brackets are used for extra-precise (especially narrow) transcription. This is consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree. Double brackets may indicate that a letter has its cardinal IPA value. For example, ⟦a⟧ is an open front vowel, rather than the perhaps slightly different value (such as open central) that «[a]» may be used to transcribe in a particular language. Thus, two vowels transcribed for easy legibility as ⟨[e]⟩ and ⟨[ɛ]⟩ may be clarified as actually being ⟦e̝⟧ and ⟦e⟧; ⟨[ð]⟩ may be more precisely ⟦ð̠̞ˠ⟧.[20] Double brackets may also be used for a specific token or speaker; for example, the pronunciation of a child as opposed to the adult phonetic pronunciation that is their target.[21] |

| ⫽ … ⫽ | … | ‖ … ‖ { … } |

Double slashes are used for morphophonemic transcription. This is also consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree (in this case, more abstract than phonemic transcription).

Other symbols sometimes seen for morphophonemic transcription are pipes and double pipes, from Americanist phonetic notation; and braces from set theory, especially when enclosing the set of phonemes that constitute the morphophoneme, e.g. {t d} or {t|d} or {/t/, /d/}. Only double slashes are unambiguous: both pipes and braces conflict with IPA prosodic transcription.[note 10] See morphophonology for examples. |

| ⟨ … ⟩ ⟪ … ⟫ |

Angle brackets[note 11] are used to mark both original Latin orthography and transliteration from another script; they are also used to identify individual graphemes of any script.[22][23] Within the IPA, they are used to indicate the IPA letters themselves rather than the sound values that they carry. Double angle brackets may occasionally be useful to distinguish original orthography from transliteration, or the idiosyncratic spelling of a manuscript from the normalized orthography of the language.

For example, ⟨cot⟩ would be used for the orthography of the English word cot, as opposed to its pronunciation /ˈkɒt/. Italics are usual when words are written as themselves (as with cot in the previous sentence) rather than to specifically note their orthography. However, italic markup is not evident to sight-impaired readers who rely on screen reader technology. |

Some examples of contrasting brackets in the literature:

In some English accents, the phoneme /l/, which is usually spelled as ⟨l⟩ or ⟨ll⟩, is articulated as two distinct allophones: the clear [l] occurs before vowels and the consonant /j/, whereas the dark [ɫ]/[lˠ] occurs before consonants, except /j/, and at the end of words.[24]

the alternations /f/ – /v/ in plural formation in one class of nouns, as in knife /naɪf/ – knives /naɪvz/, which can be represented morphophonemically as {naɪV} – {naɪV+z}. The morphophoneme {V} stands for the phoneme set {/f/, /v/}.[25]

[ˈffaɪnəlz ˈhɛld ɪn (.) ⸨knock on door⸩ bɑɹsə{𝑝ˈloʊnə and ˈmədɹɪd 𝑝}] — f-finals held in Barcelona and Madrid.[26]

Other representations[edit]

IPA letters have cursive forms designed for use in manuscripts and when taking field notes, but the 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association recommended against their use, as cursive IPA is «harder for most people to decipher.»[27] A braille representation of the IPA for blind or visually impaired professionals and students has also been developed.[28]

Modifying the IPA chart[edit]

The authors of textbooks or similar publications often create revised versions of the IPA chart to express their own preferences or needs. The image displays one such version. All pulmonic consonants are moved to the consonant chart. Only the black symbols are on the official IPA chart; additional symbols are in grey. The grey fricatives are part of the extIPA, and the grey retroflex letters are mentioned or implicit in the Handbook. The grey click is a retired IPA letter that is still in use.

The International Phonetic Alphabet is occasionally modified by the Association. After each modification, the Association provides an updated simplified presentation of the alphabet in the form of a chart. (See History of the IPA.) Not all aspects of the alphabet can be accommodated in a chart of the size published by the IPA. The alveolo-palatal and epiglottal consonants, for example, are not included in the consonant chart for reasons of space rather than of theory (two additional columns would be required, one between the retroflex and palatal columns and the other between the pharyngeal and glottal columns), and the lateral flap would require an additional row for that single consonant, so they are listed instead under the catchall block of «other symbols».[29] The indefinitely large number of tone letters would make a full accounting impractical even on a larger page, and only a few examples are shown, and even the tone diacritics are not complete; the reversed tone letters are not illustrated at all.

The procedure for modifying the alphabet or the chart is to propose the change in the Journal of the IPA. (See, for example, August 2008 on an open central unrounded vowel and August 2011 on central approximants.)[30] Reactions to the proposal may be published in the same or subsequent issues of the Journal (as in August 2009 on the open central vowel).[31] A formal proposal is then put to the Council of the IPA[32] – which is elected by the membership[33] – for further discussion and a formal vote.[34][35]

Nonetheless, many users of the alphabet, including the leadership of the Association itself, deviate from this norm.[note 12]

The Journal of the IPA finds it acceptable to mix IPA and extIPA symbols in consonant charts in their articles. (For instance, including the extIPA letter ⟨𝼆⟩, rather than ⟨ʎ̝̊⟩, in an illustration of the IPA.)[36]

Usage[edit]

Of more than 160 IPA symbols, relatively few will be used to transcribe speech in any one language, with various levels of precision. A precise phonetic transcription, in which sounds are specified in detail, is known as a narrow transcription. A coarser transcription with less detail is called a broad transcription. Both are relative terms, and both are generally enclosed in square brackets.[1] Broad phonetic transcriptions may restrict themselves to easily heard details, or only to details that are relevant to the discussion at hand, and may differ little if at all from phonemic transcriptions, but they make no theoretical claim that all the distinctions transcribed are necessarily meaningful in the language.

Phonetic transcriptions of the word international in two English dialects

For example, the English word little may be transcribed broadly as [ˈlɪtəl], approximately describing many pronunciations. A narrower transcription may focus on individual or dialectical details: [ˈɫɪɾɫ] in General American, [ˈlɪʔo] in Cockney, or [ˈɫɪːɫ] in Southern US English.

Phonemic transcriptions, which express the conceptual counterparts of spoken sounds, are usually enclosed in slashes (/ /) and tend to use simpler letters with few diacritics. The choice of IPA letters may reflect theoretical claims of how speakers conceptualize sounds as phonemes or they may be merely a convenience for typesetting. Phonemic approximations between slashes do not have absolute sound values. For instance, in English, either the vowel of pick or the vowel of peak may be transcribed as /i/, so that pick, peak would be transcribed as /ˈpik, ˈpiːk/ or as /ˈpɪk, ˈpik/; and neither is identical to the vowel of the French pique which would also be transcribed /pik/. By contrast, a narrow phonetic transcription of pick, peak, pique could be: [pʰɪk], [pʰiːk], [pikʲ].

Linguists[edit]

IPA is popular for transcription by linguists. Some American linguists, however, use a mix of IPA with Americanist phonetic notation or use some nonstandard symbols for various reasons.[37] Authors who employ such nonstandard use are encouraged to include a chart or other explanation of their choices, which is good practice in general, as linguists differ in their understanding of the exact meaning of IPA symbols and common conventions change over time.

Dictionaries[edit]

English[edit]

Many British dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary and some learner’s dictionaries such as the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary and the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, now use the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent the pronunciation of words.[38] However, most American (and some British) volumes use one of a variety of pronunciation respelling systems, intended to be more comfortable for readers of English and to be more acceptable across dialects, without the implication of a preferred pronunciation that the IPA might convey. For example, the respelling systems in many American dictionaries (such as Merriam-Webster) use ⟨y⟩ for IPA [ j] and ⟨sh⟩ for IPA [ ʃ ], reflecting the usual spelling of those sounds in English.[39]

(In IPA, [y] represents the sound of the French ⟨u⟩, as in tu, and [sh] represents the sequence of consonants in grasshopper.)

Other languages[edit]

The IPA is also not universal among dictionaries in languages other than English. Monolingual dictionaries of languages with phonemic orthographies generally do not bother with indicating the pronunciation of most words, and tend to use respelling systems for words with unexpected pronunciations. Dictionaries produced in Israel use the IPA rarely and sometimes use the Hebrew alphabet for transcription of foreign words.[note 13] Bilingual dictionaries that translate from foreign languages into Russian usually employ the IPA, but monolingual Russian dictionaries occasionally use pronunciation respelling for foreign words.[note 14] The IPA is more common in bilingual dictionaries, but there are exceptions here too. Mass-market bilingual Czech dictionaries, for instance, tend to use the IPA only for sounds not found in Czech.[40]

Standard orthographies and case variants[edit]

IPA letters have been incorporated into the alphabets of various languages, notably via the Africa Alphabet in many sub-Saharan languages such as Hausa, Fula, Akan, Gbe languages, Manding languages, Lingala, etc. Capital case variants have been created for use in these languages. For example, Kabiyè of northern Togo has Ɖ ɖ, Ŋ ŋ, Ɣ ɣ, Ɔ ɔ, Ɛ ɛ, Ʋ ʋ. These, and others, are supported by Unicode, but appear in Latin ranges other than the IPA extensions.

In the IPA itself, however, only lower-case letters are used. The 1949 edition of the IPA handbook indicated that an asterisk ⟨*⟩ might be prefixed to indicate that a word was a proper name,[41] but this convention was not included in the 1999 Handbook, which notes the contrary use of the asterisk as a placeholder for a sound or feature that does not have a symbol.

Classical singing[edit]

The IPA has widespread use among classical singers during preparation as they are frequently required to sing in a variety of foreign languages. They are also taught by vocal coaches to perfect diction and improve tone quality and tuning.[42] Opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA, such as Nico Castel’s volumes[43] and Timothy Cheek’s book Singing in Czech.[44] Opera singers’ ability to read IPA was used by the site Visual Thesaurus, which employed several opera singers «to make recordings for the 150,000 words and phrases in VT’s lexical database … for their vocal stamina, attention to the details of enunciation, and most of all, knowledge of IPA».[45]

Letters[edit]

The International Phonetic Association organizes the letters of the IPA into three categories: pulmonic consonants, non-pulmonic consonants, and vowels.[46][47]

Pulmonic consonant letters are arranged singly or in pairs of voiceless (tenuis) and voiced sounds, with these then grouped in columns from front (labial) sounds on the left to back (glottal) sounds on the right. In official publications by the IPA, two columns are omitted to save space, with the letters listed among ‘other symbols’ even though theoretically they belong in the main chart,[note 15] and with the remaining consonants arranged in rows from full closure (occlusives: stops and nasals), to brief closure (vibrants: trills and taps), to partial closure (fricatives) and minimal closure (approximants), again with a row left out to save space. In the table below, a slightly different arrangement is made: All pulmonic consonants are included in the pulmonic-consonant table, and the vibrants and laterals are separated out so that the rows reflect the common lenition pathway of stop → fricative → approximant, as well as the fact that several letters pull double duty as both fricative and approximant; affricates may be created by joining stops and fricatives from adjacent cells. Shaded cells represent articulations that are judged to be impossible.

Vowel letters are also grouped in pairs—of unrounded and rounded vowel sounds—with these pairs also arranged from front on the left to back on the right, and from maximal closure at top to minimal closure at bottom. No vowel letters are omitted from the chart, though in the past some of the mid central vowels were listed among the ‘other symbols’.

Consonants[edit]

Pulmonic consonants[edit]

A pulmonic consonant is a consonant made by obstructing the glottis (the space between the vocal cords) or oral cavity (the mouth) and either simultaneously or subsequently letting out air from the lungs. Pulmonic consonants make up the majority of consonants in the IPA, as well as in human language. All consonants in English fall into this category.[48]

The pulmonic consonant table, which includes most consonants, is arranged in rows that designate manner of articulation, meaning how the consonant is produced, and columns that designate place of articulation, meaning where in the vocal tract the consonant is produced. The main chart includes only consonants with a single place of articulation.

Notes

- In rows where some letters appear in pairs (the obstruents), the letter to the right represents a voiced consonant (except breathy-voiced [ɦ]).[49] In the other rows (the sonorants), the single letter represents a voiced consonant.

- While IPA provides a single letter for the coronal places of articulation (for all consonants but fricatives), these do not always have to be used exactly. When dealing with a particular language, the letters may be treated as specifically dental, alveolar, or post-alveolar, as appropriate for that language, without diacritics.

- Shaded areas indicate articulations judged to be impossible.

- The letters [β, ð, ʁ, ʕ, ʢ] are canonically voiced fricatives but may be used for approximants.[50]

- In many languages, such as English, [h] and [ɦ] are not actually glottal, fricatives, or approximants. Rather, they are bare phonation.[51]

- It is primarily the shape of the tongue rather than its position that distinguishes the fricatives [ʃ ʒ], [ɕ ʑ], and [ʂ ʐ].

- [ʜ, ʢ] are defined as epiglottal fricatives under the «Other symbols» section in the official IPA chart, but they may be treated as trills at the same place of articulation as [ħ, ʕ] because trilling of the aryepiglottic folds typically co-occurs.[52]

- Some listed phones are not known to exist as phonemes in any language.

Non-pulmonic consonants[edit]

Non-pulmonic consonants are sounds whose airflow is not dependent on the lungs. These include clicks (found in the Khoisan languages and some neighboring Bantu languages of Africa), implosives (found in languages such as Sindhi, Hausa, Swahili and Vietnamese), and ejectives (found in many Amerindian and Caucasian languages).

Notes

- Clicks have traditionally been described as consisting of a forward place of articulation, commonly called the click ‘type’ or historically the ‘influx’, and a rear place of articulation, which when combined with the voicing, aspiration, nasalization, affrication, ejection, timing etc. of the click is commonly called the click ‘accompaniment’ or historically the ‘efflux’. The IPA click letters indicate only the click type (forward articulation and release). Therefore, all clicks require two letters for proper notation: ⟨k͡ǂ, ɡ͡ǂ, ŋ͡ǂ, q͡ǂ, ɢ͡ǂ, ɴ͡ǂ⟩ etc., or with the order reversed if both the forward and rear releases are audible. The letter for the rear articulation is frequently omitted, in which case a ⟨k⟩ may usually be assumed. However, some researchers dispute the idea that clicks should be analyzed as doubly articulated, as the traditional transcription implies, and analyze the rear occlusion as solely a part of the airstream mechanism.[53] In transcriptions of such approaches, the click letter represents both places of articulation, with the different letters representing the different click types, and diacritics are used for the elements of the accompaniment: ⟨ǂ, ǂ̬, ǂ̃⟩ etc.

- Letters for the voiceless implosives ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ are no longer supported by the IPA, though they remain in Unicode. Instead, the IPA typically uses the voiced equivalent with a voiceless diacritic: ⟨ɓ̥, ʛ̥⟩, etc..

- The letter for the retroflex implosive, ⟨ᶑ ⟩, is not «explicitly IPA approved» (Handbook, p. 166), but has the expected form if such a symbol were to be approved.

- The ejective diacritic is placed at the right-hand margin of the consonant, rather than immediately after the letter for the stop: ⟨t͜ʃʼ⟩, ⟨kʷʼ⟩. In imprecise transcription, it often stands in for a superscript glottal stop in glottalized but pulmonic sonorants, such as [mˀ], [lˀ], [wˀ], [aˀ] (also transcribable as creaky [m̰], [l̰], [w̰], [a̰]).

Affricates[edit]

Affricates and co-articulated stops are represented by two letters joined by a tie bar, either above or below the letters with no difference in meaning.[note 16] Affricates are optionally represented by ligatures (e.g. ⟨ʦ, ʣ, ʧ, ʤ, ʨ, ʥ, ꭧ, ꭦ ⟩), though this is no longer official IPA usage[1] because a great number of ligatures would be required to represent all affricates this way. Alternatively, a superscript notation for a consonant release is sometimes used to transcribe affricates, for example ⟨tˢ⟩ for [t͜s], paralleling [kˣ] ~ [k͜x]. The letters for the palatal plosives ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are often used as a convenience for [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ] or similar affricates, even in official IPA publications, so they must be interpreted with care.

Co-articulated consonants[edit]

Co-articulated consonants are sounds that involve two simultaneous places of articulation (are pronounced using two parts of the vocal tract). In English, the [w] in «went» is a coarticulated consonant, being pronounced by rounding the lips and raising the back of the tongue. Similar sounds are [ʍ] and [ɥ]. In some languages, plosives can be double-articulated, for example in the name of Laurent Gbagbo.

Notes

- [ɧ], the Swedish sj-sound, is described by the IPA as a «simultaneous [ʃ] and [x]«, but it is unlikely such a simultaneous fricative actually exists in any language.[54]

- Multiple tie bars can be used: ⟨a͡b͡c⟩ or ⟨a͜b͜c⟩. For instance, if a prenasalized stop is transcribed ⟨m͡b⟩, and a doubly articulated stop ⟨ɡ͡b⟩, then a prenasalized doubly articulated stop would be ⟨ŋ͡m͡ɡ͡b⟩

- If a diacritic needs to be placed on or under a tie bar, the combining grapheme joiner (U+034F) needs to be used, as in [b͜͏̰də̀bdɷ̀] ‘chewed’ (Margi). Font support is spotty, however.

Vowels[edit]

Tongue positions of cardinal front vowels, with highest point indicated. The position of the highest point is used to determine vowel height and backness.

The IPA defines a vowel as a sound which occurs at a syllable center.[55] Below is a chart depicting the vowels of the IPA. The IPA maps the vowels according to the position of the tongue.

The vertical axis of the chart is mapped by vowel height. Vowels pronounced with the tongue lowered are at the bottom, and vowels pronounced with the tongue raised are at the top. For example, [ɑ] (the first vowel in father) is at the bottom because the tongue is lowered in this position. [i] (the vowel in «meet») is at the top because the sound is said with the tongue raised to the roof of the mouth.

In a similar fashion, the horizontal axis of the chart is determined by vowel backness. Vowels with the tongue moved towards the front of the mouth (such as [ɛ], the vowel in «met») are to the left in the chart, while those in which it is moved to the back (such as [ʌ], the vowel in «but») are placed to the right in the chart.

In places where vowels are paired, the right represents a rounded vowel (in which the lips are rounded) while the left is its unrounded counterpart.

Diphthongs[edit]

Diphthongs are typically specified with a non-syllabic diacritic, as in ⟨uɪ̯⟩ or ⟨u̯ɪ⟩, or with a superscript for the on- or off-glide, as in ⟨uᶦ⟩ or ⟨ᵘɪ⟩. Sometimes a tie bar is used: ⟨u͡ɪ⟩, especially if it is difficult to tell if the diphthong is characterized by an on-glide, an off-glide or is variable.

Notes

- ⟨a⟩ officially represents a front vowel, but there is little if any distinction between front and central open vowels (see Vowel § Acoustics), and ⟨a⟩ is frequently used for an open central vowel.[37] If disambiguation is required, the retraction diacritic or the centralized diacritic may be added to indicate an open central vowel, as in ⟨a̠⟩ or ⟨ä⟩.

Diacritics and prosodic notation [edit]

Diacritics are used for phonetic detail. They are added to IPA letters to indicate a modification or specification of that letter’s normal pronunciation.[56]

By being made superscript, any IPA letter may function as a diacritic, conferring elements of its articulation to the base letter. Those superscript letters listed below are specifically provided for by the IPA Handbook; other uses can be illustrated with ⟨tˢ⟩ ([t] with fricative release), ⟨ᵗs⟩ ([s] with affricate onset), ⟨ⁿd⟩ (prenasalized [d]), ⟨bʱ⟩ ([b] with breathy voice), ⟨mˀ⟩ (glottalized [m]), ⟨sᶴ⟩ ([s] with a flavor of [ʃ], i.e. a voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant), ⟨oᶷ⟩ ([o] with diphthongization), ⟨ɯᵝ⟩ (compressed [ɯ]). Superscript diacritics placed after a letter are ambiguous between simultaneous modification of the sound and phonetic detail at the end of the sound. For example, labialized ⟨kʷ⟩ may mean either simultaneous [k] and [w] or else [k] with a labialized release. Superscript diacritics placed before a letter, on the other hand, normally indicate a modification of the onset of the sound (⟨mˀ⟩ glottalized [m], ⟨ˀm⟩ [m] with a glottal onset). (See § Superscript IPA.)

| Syllabicity diacritics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◌̩ | ɹ̩ n̩ | Syllabic | ◌̯ | ɪ̯ ʊ̯ | Non-syllabic |

| ◌̍ | ɻ̍ ŋ̍ | ◌̑ | y̑ | ||

| Consonant-release diacritics | |||||

| ◌ʰ | tʰ | Aspirated[a] | ◌̚ | p̚ | No audible release |

| ◌ⁿ | dⁿ | Nasal release | ◌ˡ | dˡ | Lateral release |

| ◌ᶿ | tᶿ | Voiceless dental fricative release | ◌ˣ | tˣ | Voiceless velar fricative release |

| ◌ᵊ | dᵊ | Mid central vowel release | |||

| Phonation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̥ | n̥ d̥ | Voiceless | ◌̬ | s̬ t̬ | Voiced |

| ◌̊ | ɻ̊ ŋ̊ | ||||

| ◌̤ | b̤ a̤ | Breathy voiced[a] | ◌̰ | b̰ a̰ | Creaky voiced |

| Articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̪ | t̪ d̪ | Dental | ◌̼ | t̼ d̼ | Linguolabial |

| ◌͆ | ɮ͆ | ||||

| ◌̺ | t̺ d̺ | Apical | ◌̻ | t̻ d̻ | Laminal |

| ◌̟ | u̟ t̟ | Advanced (fronted) | ◌̠ | i̠ t̠ | Retracted (backed) |

| ◌᫈ | ɡ᫈ | ◌̄ | q̄[b] | ||

| ◌̈ | ë ä | Centralized | ◌̽ | e̽ ɯ̽ | Mid-centralized |

| ◌̝ | e̝ r̝ | Raised ([r̝], [ɭ˔] are fricatives) |

◌̞ | e̞ β̞ | Lowered ([β̞], [ɣ˕] are approximants) |

| ◌˔ | ɭ˔ | ◌˕ | y˕ ɣ˕ | ||

| Co-articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̹ | ɔ̹ x̹ | More rounded (over-rounding) |

◌̜ | ɔ̜ xʷ̜ | Less rounded (under-rounding)[c] |

| ◌͗ | y͗ χ͗ | ◌͑ | y͑ χ͑ʷ | ||

| ◌ʷ | tʷ dʷ | Labialized | ◌ʲ | tʲ dʲ | Palatalized |

| ◌ˠ | tˠ dˠ | Velarized | ◌̴ | ɫ ᵶ | Velarized or pharyngealized |

| ◌ˤ | tˤ aˤ | Pharyngealized | |||

| ◌̘ | e̘ o̘ | Advanced tongue root | ◌̙ | e̙ o̙ | Retracted tongue root |

| ◌꭪ | y꭪ | ◌꭫ | y꭫ | ||

| ◌̃ | ẽ z̃ | Nasalized | ◌˞ | ɚ ɝ | Rhoticity |

Notes

- ^a With aspirated voiced consonants, the aspiration is usually also voiced (voiced aspirated – but see voiced consonants with voiceless aspiration). Many linguists prefer one of the diacritics dedicated to breathy voice over simple aspiration, such as ⟨b̤⟩. Some linguists restrict that diacritic to sonorants, such as breathy-voice ⟨m̤⟩, and transcribe voiced-aspirated obstruents as e.g. ⟨bʱ⟩.

- ^b Care must be taken that a superscript retraction sign is not mistaken for mid tone.

- ^c These are relative to the cardinal value of the letter. They can also apply to unrounded vowels: [ɛ̜] is more spread (less rounded) than cardinal [ɛ], and [ɯ̹] is less spread than cardinal [ɯ].[57]

Since ⟨xʷ⟩ can mean that the [x] is labialized (rounded) throughout its articulation, and ⟨x̜⟩ makes no sense ([x] is already completely unrounded), ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ can only mean a less-labialized/rounded [xʷ]. However, readers might mistake ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ for «[x̜]» with a labialized off-glide, or might wonder if the two diacritics cancel each other out. Placing the ‘less rounded’ diacritic under the labialization diacritic, ⟨xʷ̜⟩, makes it clear that it is the labialization that is ‘less rounded’ than its cardinal IPA value.

Subdiacritics (diacritics normally placed below a letter) may be moved above a letter to avoid conflict with a descender, as in voiceless ⟨ŋ̊⟩.[56] The raising and lowering diacritics have optional spacing forms ⟨˔⟩, ⟨˕⟩ that avoid descenders.

The state of the glottis can be finely transcribed with diacritics. A series of alveolar plosives ranging from open-glottis to closed-glottis phonation is:

| Open glottis | [t] | voiceless |

|---|---|---|

| [d̤] | breathy voice, also called murmured | |

| [d̥] | slack voice | |

| Sweet spot | [d] | modal voice |

| [d̬] | stiff voice | |

| [d̰] | creaky voice | |

| Closed glottis | [ʔ͡t] | glottal closure |

Additional diacritics are provided by the Extensions to the IPA for speech pathology.

Suprasegmentals[edit]

These symbols describe the features of a language above the level of individual consonants and vowels, that is, at the level of syllable, word or phrase. These include prosody, pitch, length, stress, intensity, tone and gemination of the sounds of a language, as well as the rhythm and intonation of speech.[58] Various ligatures of pitch/tone letters and diacritics are provided for by the Kiel Convention and used in the IPA Handbook despite not being found in the summary of the IPA alphabet found on the one-page chart.

Under capital letters below we will see how a carrier letter may be used to indicate suprasegmental features such as labialization or nasalization. Some authors omit the carrier letter, for e.g. suffixed [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ or prefixed [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟],[59] or place a spacing variant of a diacritic such as ⟨˔⟩ or ⟨˜⟩ at the beginning or end of a word to indicate that it applies to the entire word.[60]

| Length, stress, and rhythm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ˈke | Primary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

ˌke | Secondary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

| eː kː | Long (long vowel or geminate consonant) |

eˑ | Half-long |

| ə̆ ɢ̆ | Extra-short | ||

| ek.ste eks.te |

Syllable break (internal boundary) |

es‿e | Linking (lack of a boundary; a phonological word)[note 17] |

| Intonation | |||

| | | Minor or foot break | ‖ | Major or intonation break |

| ↗︎ | Global rise[note 18] | ↘︎ | Global fall[note 18] |

| Up- and down-step | |||

| ꜛke | Upstep | ꜜke | Downstep |

| Pitch diacritics[note 19] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ŋ̋ e̋ | Extra high | ŋ̌ ě | Rising | ŋ᷄ e᷄ | Mid-rising |

| ŋ́ é | High | ŋ̂ ê | Falling | ŋ᷅ e᷅ | Low-rising |

| ŋ̄ ē | Mid | ŋ᷈ e᷈ | Peaking (rising–falling) | ŋ᷇ e᷇ | High-falling |

| ŋ̀ è | Low | ŋ᷉ e᷉ | Dipping (falling–rising) | ŋ᷆ e᷆ | Mid-falling |

| ŋ̏ ȅ | Extra low | (etc.)[note 20] |

| Chao tone letters[note 19] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ˥e | ꜒e | e˥ | e꜒ | High |

| ˦e | ꜓e | e˦ | e꜓ | Half-high |

| ˧e | ꜔e | e˧ | e꜔ | Mid |

| ˨e | ꜕e | e˨ | e꜕ | Half-low |

| ˩e | ꜖e | e˩ | e꜖ | Low |

| ˩˥e | ꜖꜒e | e˩˥ | e꜖꜒ | Rising (low to high or generic) |

| ˥˩e | ꜒꜖e | e˥˩ | e꜒꜖ | Falling (high to low or generic) |

| (etc.) |

The old staveless tone letters, which are effectively obsolete, include high ⟨ˉe⟩, mid ⟨˗e⟩, low ⟨ˍe⟩, rising ⟨ˊe⟩ and falling ⟨ˋe⟩.

Stress[edit]

Officially, the stress marks ⟨ˈ ˌ⟩ appear before the stressed syllable, and thus mark the syllable boundary as well as stress (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a period).[61] Occasionally the stress mark is placed immediately before the nucleus of the syllable, after any consonantal onset.[62] In such transcriptions, the stress mark does not mark a syllable boundary. The primary stress mark may be doubled ⟨ˈˈ⟩ for extra stress (such as prosodic stress). The secondary stress mark is sometimes seen doubled ⟨ˌˌ⟩ for extra-weak stress, but this convention has not been adopted by the IPA.[61] Some dictionaries place both stress marks before a syllable, ⟨¦⟩, to indicate that pronunciations with either primary or secondary stress are heard, though this is not IPA usage.[63]

Boundary markers[edit]

There are three boundary markers: ⟨.⟩ for a syllable break, ⟨|⟩ for a minor prosodic break and ⟨‖⟩ for a major prosodic break. The tags ‘minor’ and ‘major’ are intentionally ambiguous. Depending on need, ‘minor’ may vary from a foot break to a break in list-intonation to a continuing–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a comma), and while ‘major’ is often any intonation break, it may be restricted to a final–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a period). The ‘major’ symbol may also be doubled, ⟨‖‖⟩, for a stronger break.[note 21]

Although not part of the IPA, the following additional boundary markers are often used in conjunction with the IPA: ⟨μ⟩ for a mora or mora boundary, ⟨σ⟩ for a syllable or syllable boundary, ⟨+⟩ for a morpheme boundary, ⟨#⟩ for a word boundary (may be doubled, ⟨##⟩, for e.g. a breath-group boundary),[65] ⟨$⟩ for a phrase or intermediate boundary and ⟨%⟩ for a prosodic boundary. For example, C# is a word-final consonant, %V a post-pausa vowel, and T% an IU-final tone (edge tone).

Pitch and tone[edit]

⟨ꜛ ꜜ⟩ are defined in the Handbook as «upstep» and «downstep», concepts from tonal languages. However, the upstep symbol can also be used for pitch reset, and the IPA Handbook uses it for prosody in the illustration for Portuguese, a non-tonal language.

Phonetic pitch and phonemic tone may be indicated by either diacritics placed over the nucleus of the syllable (e.g., high-pitch ⟨é⟩) or by Chao tone letters placed either before or after the word or syllable. There are three graphic variants of the tone letters: with or without a stave, and facing left or facing right from the stave. The stave was introduced with the 1989 Kiel Convention, as was the option of placing a staved letter after the word or syllable, while retaining the older conventions. There are therefore six ways to transcribe pitch/tone in the IPA: i.e., ⟨é⟩, ⟨˦e⟩, ⟨e˦⟩, ⟨꜓e⟩, ⟨e꜓⟩ and ⟨ˉe⟩ for a high pitch/tone.[61][66][67] Of the tone letters, only left-facing staved letters and a few representative combinations are shown in the summary on the Chart, and in practice it is currently more common for tone letters to occur after the syllable/word than before, as in the Chao tradition. Placement before the word is a carry-over from the pre-Kiel IPA convention, as is still the case for the stress and upstep/downstep marks. The IPA endorses the Chao tradition of using the left-facing tone letters, ⟨˥ ˦ ˧ ˨ ˩⟩, for underlying tone, and the right-facing letters, ⟨꜒ ꜓ ꜔ ꜕ ꜖⟩, for surface tone, as occurs in tone sandhi, and for the intonation of non-tonal languages.[note 22] In the Portuguese illustration in the 1999 Handbook, tone letters are placed before a word or syllable to indicate prosodic pitch (equivalent to [↗︎] global rise and [↘︎] global fall, but allowing more precision), and in the Cantonese illustration they are placed after a word/syllable to indicate lexical tone. Theoretically therefore prosodic pitch and lexical tone could be simultaneously transcribed in a single text, though this is not a formalized distinction.

Rising and falling pitch, as in contour tones, are indicated by combining the pitch diacritics and letters in the table, such as grave plus acute for rising [ě] and acute plus grave for falling [ê]. Only six combinations of two diacritics are supported, and only across three levels (high, mid, low), despite the diacritics supporting five levels of pitch in isolation. The four other explicitly approved rising and falling diacritic combinations are high/mid rising [e᷄], low rising [e᷅], high falling [e᷇], and low/mid falling [e᷆].[note 23]

The Chao tone letters, on the other hand, may be combined in any pattern, and are therefore used for more complex contours and finer distinctions than the diacritics allow, such as mid-rising [e˨˦], extra-high falling [e˥˦], etc. There are 20 such possibilities. However, in Chao’s original proposal, which was adopted by the IPA in 1989, he stipulated that the half-high and half-low letters ⟨˦ ˨⟩ may be combined with each other, but not with the other three tone letters, so as not to create spuriously precise distinctions. With this restriction, there are 8 possibilities.[68]

The old staveless tone letters tend to be more restricted than the staved letters, though not as restricted as the diacritics. Officially, they support as many distinctions as the staved letters,[69] but typically only three pitch levels are distinguished. Unicode supports default or high-pitch ⟨ˉ ˊ ˋ ˆ ˇ ˜ ˙⟩ and low-pitch ⟨ˍ ˏ ˎ ꞈ ˬ ˷⟩. Only a few mid-pitch tones are supported (such as ⟨˗ ˴⟩), and then only accidentally.

Although tone diacritics and tone letters are presented as equivalent on the chart, «this was done only to simplify the layout of the chart. The two sets of symbols are not comparable in this way.»[70] Using diacritics, a high tone is ⟨é⟩ and a low tone is ⟨è⟩; in tone letters, these are ⟨e˥⟩ and ⟨e˩⟩. One can double the diacritics for extra-high ⟨e̋⟩ and extra-low ⟨ȅ⟩; there is no parallel to this using tone letters. Instead, tone letters have mid-high ⟨e˦⟩ and mid-low ⟨e˨⟩; again, there is no equivalent among the diacritics.

The correspondence breaks down even further once they start combining. For more complex tones, one may combine three or four tone diacritics in any permutation,[61] though in practice only generic peaking (rising-falling) e᷈ and dipping (falling-rising) e᷉ combinations are used. Chao tone letters are required for finer detail (e˧˥˧, e˩˨˩, e˦˩˧, e˨˩˦, etc.). Although only 10 peaking and dipping tones were proposed in Chao’s original, limited set of tone letters, phoneticians often make finer distinctions, and indeed an example is found on the IPA Chart.[note 24] The system allows the transcription of 112 peaking and dipping pitch contours, including tones that are level for part of their length.

| Register | Level [note 26] |

Rising | Falling | Peaking | Dipping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e˩ | e˩˩ | e˩˧ | e˧˩ | e˩˧˩ | e˧˩˧ |

| e˨ | e˨˨ | e˨˦ | e˦˨ | e˨˦˨ | e˦˨˦ |

| e˧ | e˧˧ | e˧˥ | e˥˧ | e˧˥˧ | e˥˧˥ |

| e˦ | e˦˦ | e˧˥˩ | e˧˩˥ | ||

| e˥ | e˥˥ | e˩˥ | e˥˩ | e˩˥˧ | e˥˩˧ |

More complex contours are possible. Chao gave an example of [꜔꜒꜖꜔] (mid-high-low-mid) from English prosody.[68]

Chao tone letters generally appear after each syllable, for a language with syllable tone (⟨a˧vɔ˥˩⟩), or after the phonological word, for a language with word tone (⟨avɔ˧˥˩⟩). The IPA gives the option of placing the tone letters before the word or syllable (⟨˧a˥˩vɔ⟩, ⟨˧˥˩avɔ⟩), but this is rare for lexical tone. (And indeed reversed tone letters may be used to clarify that they apply to the following rather than to the preceding syllable: ⟨꜔a꜒꜖vɔ⟩, ⟨꜔꜒꜖avɔ⟩.) The staveless letters are not directly supported by Unicode, but some fonts allow the stave in Chao tone letters to be suppressed.

Comparative degree[edit]

IPA diacritics may be doubled to indicate an extra degree of the feature indicated.[71] This is a productive process, but apart from extra-high and extra-low tones ⟨ə̋, ə̏⟩ being marked by doubled high- and low-tone diacritics, and the major prosodic break ⟨‖⟩ being marked as a double minor break ⟨|⟩, it is not specifically regulated by the IPA. (Note that transcription marks are similar: double slashes indicate extra (morpho)-phonemic, double square brackets especially precise, and double parentheses especially unintelligible.)

For example, the stress mark may be doubled to indicate an extra degree of stress, such as prosodic stress in English.[72] An example in French, with a single stress mark for normal prosodic stress at the end of each prosodic unit (marked as a minor prosodic break), and a double stress mark for contrastive/emphatic stress: [ˈˈɑ̃ːˈtre | məˈsjø ‖ ˈˈvwala maˈdam ‖] Entrez monsieur, voilà madame.[73] Similarly, a doubled secondary stress mark ⟨ˌˌ⟩ is commonly used for tertiary (extra-light) stress.[74] In a similar vein, the effectively obsolete (though never retired) staveless tone letters were once doubled for an emphatic rising intonation ⟨˶⟩ and an emphatic falling intonation ⟨˵⟩.[75]

Length is commonly extended by repeating the length mark, as in English shhh! [ʃːːː], or for «overlong» segments in Estonian:

- vere /vere/ ‘blood [gen.sg.]’, veere /veːre/ ‘edge [gen.sg.]’, veere /veːːre/ ‘roll [imp. 2nd sg.]’

- lina /linɑ/ ‘sheet’, linna /linːɑ/ ‘town [gen. sg.]’, linna /linːːɑ/ ‘town [ine. sg.]’

(Normally additional degrees of length are handled by the extra-short or half-long diacritic, but the first two words in each of the Estonian examples are analyzed as simply short and long, requiring a different remedy for the final words.)

Occasionally other diacritics are doubled:

- Rhoticity in Badaga /be/ «mouth», /be˞/ «bangle», and /be˞˞/ «crop».[76]

- Mild and strong aspirations, [kʰ], [kʰʰ].[note 27]

- Nasalization, as in Palantla Chinantec lightly nasalized /ẽ/ vs heavily nasalized /e͌/,[77] though in extIPA the latter indicates velopharyngeal frication.

- Weak vs strong ejectives, [kʼ], [kˮ].[78]

- Especially lowered, e.g. [t̞̞] (or [t̞˕], if the former symbol does not display properly) for /t/ as a weak fricative in some pronunciations of register.[79]

- Especially retracted, e.g. [ø̠̠] or [s̠̠],[80][71][81] though some care might be needed to distinguish this from indications of alveolar or alveolarized articulation in extIPA, e.g. [s͇].

- The transcription of strident and harsh voice as extra-creaky /a᷽/ may be motivated by the similarities of these phonations.

Ambiguous letters[edit]

A number of IPA letters are not consistently used for their official values. A distinction between voiced fricatives and approximants is only partially implemented by the IPA, for example. Even with the relatively recent addition of the palatal fricative ⟨ʝ⟩ and the velar approximant ⟨ɰ⟩ to the alphabet, other letters, though defined as fricatives, are often ambiguous between fricative and approximant. For forward places, ⟨β⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ can generally be assumed to be fricatives unless they carry a lowering diacritic. Rearward, however, ⟨ʁ⟩ and ⟨ʕ⟩ are perhaps more commonly intended to be approximants even without a lowering diacritic. ⟨h⟩ and ⟨ɦ⟩ are similarly either fricatives or approximants, depending on the language, or even glottal «transitions», without that often being specified in the transcription.

Another common ambiguity is among the letters for palatal consonants. ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are not uncommonly used as a typographic convenience for affricates, typically [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ], while ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ʎ⟩ are commonly used for palatalized alveolar [n̠ʲ] and [l̠ʲ]. To some extent this may be an effect of analysis, but it is common to match up single IPA letters to the phonemes of a language, without overly worrying about phonetic precision.

It has been argued that the lower-pharyngeal (epiglottal) fricatives ⟨ʜ⟩ and ⟨ʢ⟩ are better characterized as trills, rather than as fricatives that have incidental trilling.[82] This has the advantage of merging the upper-pharyngeal fricatives [ħ, ʕ] together with the epiglottal plosive [ʡ] and trills [ʜ ʢ] into a single pharyngeal column in the consonant chart. However, in Shilha Berber the epiglottal fricatives are not trilled.[83][84] Although they might be transcribed ⟨ħ̠ ʢ̠⟩ to indicate this, the far more common transcription is ⟨ʜ ʢ⟩, which is therefore ambiguous between languages.

Among vowels, ⟨a⟩ is officially a front vowel, but is more commonly treated as a central vowel. The difference, to the extent it is even possible, is not phonemic in any language.

For all phonetic notation, it is good practice for an author to specify exactly what they mean by the symbols that they use.

Redundant letters[edit]

Three letters are not needed and would be hard to justify today by the standards of the modern IPA, but are retained due to inertia. ⟨ʍ⟩ appears because it is found in English; officially it is a fricative, with terminology dating to the days before ‘fricative’ and ‘approximant’ were distinguished. Based on how all other fricatives and approximants are transcribed, one would expect either ⟨xʷ⟩ for a fricative (not how it is actually used) or ⟨w̥⟩ for an approximant. Indeed, outside of English transcription, that is what is more commonly found in the literature. ⟨ɱ⟩ is another historic remnant. It is a nearly universal allophone of [m] before [f] and [v], but it is only phonemically distinct in a single language (Kukuya), a fact that was discovered long after it was standardized in the IPA. (A number of consonants do not have dedicated IPA letters despite being phonemic in many more languages.) ⟨ɱ⟩ is retained because of its historical use for European languages, where it could easily be normalized to ⟨m̪⟩. There have been several votes to retire ⟨ɱ⟩ from the IPA, but so far they have failed. Finally, ⟨ɧ⟩ is officially a simultaneous postalveolar and velar fricative, a realization that does not appear to exist in any language. It is retained because it is convenient for the transcription of Swedish, where it is used for a consonant that has various realizations in different dialects. That is, it is not actually a phonetic character at all, but a phonemic one, which is officially beyond the purview of the IPA alphabet; indeed, another phonemic IPA letter, ⟨ƞ⟩ for the homorganic nasal of Japanese, was retired because it had no defined phonetic value.

Superscript letters[edit]

Superscript IPA letters may be used to indicate secondary articulation; onsets, releases and other transitions; shades of sound; light epenthetic sounds and incompletely articulated sounds. In 2020, the IPA and ICPLA endorsed the Unicode encoding of superscript variants of all contemporary IPA letters apart from the Chao tone letters, including the extended retroflex letters ⟨ꞎ 𝼅 𝼈 ᶑ 𝼊 ⟩, which were thus confirmed as being implicit in the IPA alphabet.[36][85][86]

Superscript letters can be meaningfully modified by combining diacritics, just as baseline letters can. For example, a superscript dental nasal is ⟨ⁿ̪d̪⟩, a superscript voiceless velar nasal is ⟨ᵑ̊ǂ⟩, and labial-velar prenasalization is ⟨ᵑ͡ᵐɡ͡b⟩. Although the diacritic may seem a bit oversized compared to the superscript letter it modifies, e.g. ⟨ᵓ̃⟩, this can be an aid to legibility, just as it is with the composite superscript c-cedilla ⟨ᶜ̧⟩ and rhotic vowels ⟨ᵊ˞ ᶟ˞⟩. Superscript length marks can be used to indicate the length of aspiration of a consonant, e.g. [pʰ tʰ𐞂 kʰ𐞁]. Another option is to double the diacritic: ⟨kʰʰ⟩.[36]

Obsolete and nonstandard symbols[edit]

A number of IPA letters and diacritics have been retired or replaced over the years. This number includes duplicate symbols, symbols that were replaced due to user preference, and unitary symbols that were rendered with diacritics or digraphs to reduce the inventory of the IPA. The rejected symbols are now considered obsolete, though some are still seen in the literature.

The IPA once had several pairs of duplicate symbols from alternative proposals, but eventually settled on one or the other. An example is the vowel letter ⟨ɷ⟩, rejected in favor of ⟨ʊ⟩. Affricates were once transcribed with ligatures, such as ⟨ʦ ʣ, ʧ ʤ, ʨ ʥ, ꭧ ꭦ ⟩ (and others not found in Unicode). These have been officially retired but are still used. Letters for specific combinations of primary and secondary articulation have also been mostly retired, with the idea that such features should be indicated with tie bars or diacritics: ⟨ƍ⟩ for [zʷ] is one. In addition, the rare voiceless implosives, ⟨ƥ ƭ ƈ ƙ ʠ ⟩, were dropped soon after their introduction and are now usually written ⟨ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ʄ̊ ɠ̊ ʛ̥ ⟩. The original set of click letters, ⟨ʇ, ʗ, ʖ, ʞ⟩, was retired but is still sometimes seen, as the current pipe letters ⟨ǀ, ǃ, ǁ, ǂ⟩ can cause problems with legibility, especially when used with brackets ([ ] or / /), the letter ⟨l⟩, or the prosodic marks ⟨|, ‖⟩. (For this reason, some publications which use the current IPA pipe letters disallow IPA brackets.)[87]

Individual non-IPA letters may find their way into publications that otherwise use the standard IPA. This is especially common with:

- Affricates, such as the Americanist barred lambda ⟨ƛ⟩ for [t͜ɬ] or ⟨č⟩ for [t͜ʃ ].[note 28]

- The Karlgren letters for Chinese vowels, ⟨ɿ, ʅ , ʮ, ʯ ⟩

- Digits for tonal phonemes that have conventional numbers in a local tradition, such as the four tones of Standard Chinese. This may be more convenient for comparison between related languages and dialects than a phonetic transcription would be, because tones vary more unpredictably than segmental phonemes do.

- Digits for tone levels, which are simpler to typeset, though the lack of standardization can cause confusion (e.g. ⟨1⟩ is high tone in some languages but low tone in others; ⟨3⟩ may be high, medium or low tone, depending on the local convention).

- Iconic extensions of standard IPA letters that can be readily understood, such as retroflex ⟨ᶑ ⟩ and ⟨ꞎ⟩. These are referred to in the Handbook and have been included in IPA requests for Unicode support.

In addition, it is common to see ad hoc typewriter substitutions, generally capital letters, for when IPA support is not available, e.g. A for ⟨ɑ⟩, B for ⟨β⟩ or ⟨ɓ⟩, D for ⟨ð⟩, ⟨ɗ ⟩ or ⟨ɖ ⟩, E for ⟨ɛ⟩, F or P for ⟨ɸ⟩, G ⟨ɣ⟩, I ⟨ɪ⟩, L ⟨ɬ⟩, N ⟨ŋ⟩, O ⟨ɔ⟩, S ⟨ ʃ ⟩, T ⟨θ⟩ or ⟨ʈ ⟩, U ⟨ʊ⟩, V ⟨ʋ⟩, X ⟨χ⟩, Z ⟨ʒ⟩, as well as @ for ⟨ə⟩ and 7 or ? for ⟨ʔ⟩. (See also SAMPA and X-SAMPA substitute notation.)

Extensions[edit]

Chart of the Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet (extIPA), as of 2015

The Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for Disordered Speech, commonly abbreviated «extIPA» and sometimes called «Extended IPA», are symbols whose original purpose was to accurately transcribe disordered speech. At the Kiel Convention in 1989, a group of linguists drew up the initial extensions,[88] which were based on the previous work of the PRDS (Phonetic Representation of Disordered Speech) Group in the early 1980s.[89] The extensions were first published in 1990, then modified, and published again in 1994 in the Journal of the International Phonetic Association, when they were officially adopted by the ICPLA.[90] While the original purpose was to transcribe disordered speech, linguists have used the extensions to designate a number of sounds within standard communication, such as hushing, gnashing teeth, and smacking lips,[2] as well as regular lexical sounds such as lateral fricatives that do not have standard IPA symbols.

In addition to the Extensions to the IPA for disordered speech, there are the conventions of the Voice Quality Symbols, which include a number of symbols for additional airstream mechanisms and secondary articulations in what they call «voice quality».

Associated notation[edit]

Capital letters and various characters on the number row of the keyboard are commonly used to extend the alphabet in various ways.

Associated symbols[edit]

There are various punctuation-like conventions for linguistic transcription that are commonly used together with IPA. Some of the more common are:

- ⟨*⟩

- (a) A reconstructed form.

- (b) An ungrammatical form (including an unphonemic form).

- ⟨**⟩

- (a) A reconstructed form, deeper (more ancient) than a single ⟨*⟩, used when reconstructing even further back from already-starred forms.

- (b) An ungrammatical form. A less common convention than ⟨*⟩ (b), this is sometimes used when reconstructed and ungrammatical forms occur in the same text.[91]

- ⟨×⟩

- An ungrammatical form. A less common convention than ⟨*⟩ (b), this is sometimes used when reconstructed and ungrammatical forms occur in the same text.[92]

- ⟨?⟩

- A doubtfully grammatical form.

- ⟨%⟩

- A generalized form, such as a typical shape of a wanderwort that has not actually been reconstructed.[93]

- ⟨#⟩

- A word boundary – e.g. ⟨#V⟩ for a word-initial vowel.

- ⟨$⟩

- A phonological word boundary; e.g. ⟨H$⟩ for a high tone that occurs in such a position.

- ⟨_⟩

- The location of a segment – e.g. ⟨V_V⟩ for an intervocalic position

Capital letters[edit]

Full capital letters are not used as IPA symbols, except as typewriter substitutes (e.g. N for ⟨ŋ⟩, S for ⟨ ʃ ⟩, O for ⟨ɔ⟩ – see SAMPA). They are, however, often used in conjunction with the IPA in two cases:

- for (archi)phonemes and for natural classes of sounds (that is, as wildcards). The extIPA chart, for example, uses capital letters as wildcards in its illustrations.

- as carrying letters for the Voice Quality Symbols.

Wildcards are commonly used in phonology to summarize syllable or word shapes, or to show the evolution of classes of sounds. For example, the possible syllable shapes of Mandarin can be abstracted as ranging from /V/ (an atonic vowel) to /CGVNᵀ/ (a consonant-glide-vowel-nasal syllable with tone), and word-final devoicing may be schematized as C → C̥/_#. In speech pathology, capital letters represent indeterminate sounds, and may be superscripted to indicate they are weakly articulated: e.g. [ᴰ] is a weak indeterminate alveolar, [ᴷ] a weak indeterminate velar.[94]

There is a degree of variation between authors as to the capital letters used, but ⟨C⟩ for {consonant}, ⟨V⟩ for {vowel} and ⟨N⟩ for {nasal} are ubiquitous in English-language material. Other common conventions are ⟨T⟩ for {tone/accent} (tonicity), ⟨P⟩ for {plosive}, ⟨F⟩ for {fricative}, ⟨S⟩ for {sibilant},[note 29] ⟨G⟩ for {glide/semivowel}, ⟨L⟩ for {lateral} or {liquid}, ⟨R⟩ for {rhotic} or {resonant/sonorant},[note 30] ⟨₵⟩ for {obstruent}, ⟨Ʞ⟩ for {click}, ⟨A, E, O, Ɨ, U⟩ for {open, front, back, close, rounded vowel}[note 31] and ⟨B, D, Ɉ, K, Q, Φ, H⟩ for {labial, alveolar, post-alveolar/palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, glottal[note 32] consonant}, respectively, and ⟨X⟩ for {any sound}. The letters can be modified with IPA diacritics, for example ⟨Cʼ⟩ for {ejective}, ⟨Ƈ ⟩ for {implosive}, ⟨N͡C⟩ or ⟨ᴺC⟩ for {prenasalized consonant}, ⟨Ṽ⟩ for {nasal vowel}, ⟨CʰV́⟩ for {aspirated CV syllable with high tone}, ⟨S̬⟩ for {voiced sibilant}, ⟨N̥⟩ for {voiceless nasal}, ⟨P͡F⟩ or ⟨Pꟳ⟩ for {affricate}, ⟨Cʲ⟩ for {palatalized consonant} and ⟨D̪⟩ for {dental consonant}. ⟨H⟩, ⟨M⟩, ⟨L⟩ are also commonly used for high, mid and low tone, with ⟨LH⟩ for rising tone and ⟨HL⟩ for falling tone, rather than transcribing them overly precisely with IPA tone letters or with ambiguous digits.[note 33]

Typical examples of archiphonemic use of capital letters are ⟨I⟩ for the Turkish harmonic vowel set {i y ɯ u};[note 34] ⟨D⟩ for the conflated flapped middle consonant of American English writer and rider; ⟨N⟩ for the homorganic syllable-coda nasal of languages such as Spanish and Japanese (essentially equivalent to the wild-card usage of the letter); and ⟨R⟩ in cases where a phonemic trill /r/ and flap /ɾ/ are indeterminate, as in Spanish enrejar /eNreˈxaR/ (the n is homorganic and the first r is a trill but the second is variable).[95] Similar usage is found for phonemic analysis, where a language does not distinguish sounds that have separate letters in the IPA. For instance, Castillian Spanish has been analyzed as having phonemes /Θ/ and /S/, which surface as [θ] and [s] in voiceless environments and as [ð] and [z] in voiced environments (e.g. hazte /ˈaΘte/, → [ˈaθte], vs hazme /ˈaΘme/, → [ˈaðme]; or las manos /laS ˈmanoS/, → [lazˈmanos]).[96]

⟨V⟩, ⟨F⟩ and ⟨C⟩ have completely different meanings as Voice Quality Symbols, where they stand for «voice» (generally meaning secondary articulation, as in ⟨Ṽ⟩ «nasal voice», not phonetic voicing), «falsetto» and «creak». They may also take diacritics that indicate what kind of voice quality an utterance has, and may be used to extract a suprasegmental feature that occurs on all susceptible segments in a stretch of IPA. For instance, the transcription of Scottish Gaelic [kʷʰuˣʷt̪ʷs̟ʷ] ‘cat’ and [kʷʰʉˣʷt͜ʃʷ] ‘cats’ (Islay dialect) can be made more economical by extracting the suprasegmental labialization of the words: Vʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] and Vʷ[kʰʉˣt͜ʃ].[97] The usual wildcard X or C might be used instead of V so that the reader does not misinterpret ⟨Vʷ⟩ as meaning that only vowels are labialized (i.e. Xʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] for all segments labialized, Cʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] for all consonants labialized), or the carrier letter may be omitted altogether (e.g. ʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟], [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟] or [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ). (See § Suprasegmentals for other transcription conventions.)

Segments without letters[edit]

The blank cells on the IPA chart can be filled without much difficulty if the need arises. The expected retroflex letter forms have appeared in the literature for the retroflex implosive ⟨ᶑ ⟩, the retroflex lateral flap ⟨𝼈 ⟩ and the retroflex clicks ⟨𝼊 ⟩; the first is mentioned in the IPA Handbook and the IPA requested Unicode support for superscript variants of all three. The missing voiceless lateral fricatives are provided for by the extIPA. The epiglottal trill is arguably covered by the generally trilled epiglottal «fricatives» ⟨ʜ ʢ⟩. Labiodental plosives ⟨ȹ ȸ⟩ appear in some old Bantuist texts. Ad hoc near-close central vowels ⟨ᵻ ᵿ⟩ are used in some descriptions of English. Diacritics can duplicate some of these; ⟨p̪ b̪⟩ are now universal for labiodental plosives, ⟨ɪ̈ ʊ̈⟩ are common for the central vowels and ⟨ɭ̆ ⟩ is occasionally seen for the lateral flap. Diacritics are able to fill in most of the remainder of the charts.[98] If a sound cannot be transcribed, an asterisk ⟨*⟩ may be used, either as a letter or as a diacritic (as in ⟨k*⟩ sometimes seen for the Korean «fortis» velar).

Consonants[edit]

Representations of consonant sounds outside of the core set are created by adding diacritics to letters with similar sound values. The Spanish bilabial and dental approximants are commonly written as lowered fricatives, [β̞] and [ð̞] respectively.[note 35] Similarly, voiced lateral fricatives would be written as raised lateral approximants, [ɭ˔ ʎ̝ ʟ̝]; extIPA provides ⟨𝼅⟩ for the first of these. A few languages such as Banda have a bilabial flap as the preferred allophone of what is elsewhere a labiodental flap. It has been suggested that this be written with the labiodental flap letter and the advanced diacritic, [ⱱ̟].[99]

Similarly, a labiodental trill would be written [ʙ̪] (bilabial trill and the dental sign), and labiodental stops [p̪ b̪] rather than with the ad hoc letters sometimes found in the literature. Other taps can be written as extra-short plosives or laterals, e.g. [ ɟ̆ ɢ̆ ʟ̆], though in some cases the diacritic would need to be written below the letter. A retroflex trill can be written as a retracted [r̠], just as non-subapical retroflex fricatives sometimes are. The remaining consonants – the uvular laterals ([ʟ̠] etc.) and the palatal trill – while not strictly impossible, are very difficult to pronounce and are unlikely to occur even as allophones in the world’s languages.

Vowels[edit]

The vowels are similarly manageable by using diacritics for raising, lowering, fronting, backing, centering, and mid-centering.[100] For example, the unrounded equivalent of [ʊ] can be transcribed as mid-centered [ɯ̽], and the rounded equivalent of [æ] as raised [ɶ̝] or lowered [œ̞] (though for those who conceive of vowel space as a triangle, simple [ɶ] already is the rounded equivalent of [æ]). True mid vowels are lowered [e̞ ø̞ ɘ̞ ɵ̞ ɤ̞ o̞] or raised [ɛ̝ œ̝ ɜ̝ ɞ̝ ʌ̝ ɔ̝], while centered [ɪ̈ ʊ̈] and [ä] (or, less commonly, [ɑ̈]) are near-close and open central vowels, respectively. The only known vowels that cannot be represented in this scheme are vowels with unexpected roundedness, which would require a dedicated diacritic, such as protruded ⟨ʏʷ⟩ and compressed ⟨uᵝ⟩ (or protruded ⟨ɪʷ⟩ and compressed ⟨ɯᶹ⟩).

Symbol names[edit]

An IPA symbol is often distinguished from the sound it is intended to represent, since there is not necessarily a one-to-one correspondence between letter and sound in broad transcription, making articulatory descriptions such as «mid front rounded vowel» or «voiced velar stop» unreliable. While the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association states that no official names exist for its symbols, it admits the presence of one or two common names for each.[101] The symbols also have nonce names in the Unicode standard. In many cases, the names in Unicode and the IPA Handbook differ. For example, the Handbook calls ⟨ɛ⟩ «epsilon», while Unicode calls it «small letter open e».

The traditional names of the Latin and Greek letters are usually used for unmodified letters.[note 36] Letters which are not directly derived from these alphabets, such as ⟨ʕ⟩, may have a variety of names, sometimes based on the appearance of the symbol or on the sound that it represents. In Unicode, some of the letters of Greek origin have Latin forms for use in IPA; the others use the characters from the Greek block.

For diacritics, there are two methods of naming. For traditional diacritics, the IPA notes the name in a well known language; for example, ⟨é⟩ is «e-acute», based on the name of the diacritic in English and French. Non-traditional diacritics are often named after objects they resemble, so ⟨d̪⟩ is called «d-bridge».

Geoffrey Pullum and William Ladusaw list a variety of names in use for both current and retired IPA symbols in their Phonetic Symbol Guide. Many of them found their way into Unicode.[9]

Computer support[edit]

Unicode[edit]

Unicode supports nearly all of the IPA alphabet. Apart from basic Latin and Greek and general punctuation, the primary blocks are IPA Extensions, Spacing Modifier Letters and Combining Diacritical Marks, with lesser support from Phonetic Extensions, Phonetic Extensions Supplement, Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement, and scattered characters elsewhere. The extended IPA is supported primarily by those blocks and Latin Extended-G.

IPA numbers[edit]

After the Kiel Convention in 1989, most IPA symbols were assigned an identifying number to prevent confusion between similar characters during the printing of manuscripts. The codes were never much used and have been superseded by Unicode.[102]

Typefaces[edit]

The sequence ⟨˨˦˧꜒꜔꜓k͜𝼄a͎̽᷅ꟸ⟩ in the fonts Gentium Book Plus, Andika, Brill, Noto Serif and Calibri. All of these fonts align diacritics well. Asterisks are characters not supported by that font. In Noto, the red tone letters do not link properly. This is a test sequence: Noto and Calibri support most IPA adequately.

Many typefaces have support for IPA characters, but good diacritic rendering remains rare.[103] Web browsers generally do not need any configuration to display IPA characters, provided that a typeface capable of doing so is available to the operating system.

System fonts[edit]

The ubiquitous Arial and Times New Roman fonts include IPA characters, but they are neither complete (especially Arial) nor render diacritics properly. The basic Latin Noto fonts are better, only failing with the more obscure characters. The proprietary Calibri font, which is the default font of Microsoft Office, has nearly complete IPA support with good diacritic rendering.

| Font | Sample | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Times New Roman | ⟨˨˦˧꜒꜔꜓k͜𝼄a͎̽᷅ꟸ⟩ | The tone letters join properly, but the tie-bar and diacritics are displaced, and the diacritics overstrike each other rather than stacking |

Other commercial fonts[edit]

Brill has good IPA support. It is a commercial font but freely available for non-commercial use.[104]

Free fonts[edit]

Typefaces that provide nearly full IPA support and properly render diacritics include Gentium Plus, Charis SIL, Doulos SIL, and Andika.

In addition to the support found in other fonts, these fonts support the full range of old-style (pre-Kiel) staveless tone letters, through a character variant option that suppresses the stave of the Chao tone letters. They also have an option to maintain the ⟨a⟩ ~ ⟨ɑ⟩ distinction in italic. However, the combining parentheses, and especially the combining paired parentheses, which are used in extIPA to bracket diacritics, often don’t display properly.

ASCII and keyboard transliterations[edit]

Several systems have been developed that map the IPA symbols to ASCII characters. Notable systems include SAMPA and X-SAMPA. The usage of mapping systems in on-line text has to some extent been adopted in the context input methods, allowing convenient keying of IPA characters that would be otherwise unavailable on standard keyboard layouts.

IETF language tags[edit]

IETF language tags have registered fonipa as a variant subtag identifying text as written in IPA.[105]

Thus, an IPA transcription of English could be tagged as en-fonipa.

For the use of IPA without attribution to a concrete language, und-fonipa is available.

Computer input using on-screen keyboard[edit]

Online IPA keyboard utilities are available, though none of them cover the complete range of IPA symbols and diacritics.[note 37] In April 2019, Google’s Gboard for Android added an IPA keyboard to its platform.[106][107] For iOS there are multiple free keyboard layouts available, e.g. «IPA Phonetic Keyboard».[108]

See also[edit]

- Afroasiatic phonetic notation

- Americanist phonetic notation – Phonetic alphabet developed in the 1880s

- Arabic International Phonetic Alphabet – System of phonetic transcription to adapt the International Phonetic Alphabet to the Arabic script

- Articulatory phonetics – A branch of linguistics studying how humans make sounds

- Case variants of IPA letters – International Phonetic Alphabet variants

- Cursive forms of the International Phonetic Alphabet – Deprecated cursive forms of IPA symbols

- Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet – Disordered speech additions to the phonetic alphabet

- Index of phonetics articles

- International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration – Transliteration scheme for Indic scripts

- International Phonetic Alphabet chart for English dialects

- List of international common standards

- Luciano Canepari – Italian linguist (born 1947)

- Phonetic symbols in Unicode – Representation of phonetic symbols in the Unicode Standard

- RFE Phonetic Alphabet – phonetic transcription system for Iberian languages, proposed by Tomás Navarro Tomás and adopted by Centro de Estudios Históricos for use in its journal Revista de Filología Española (whence its name)

- SAMPA – Computer-readable phonetic script

- Semyon Novgorodov – Yakut politician and linguist – inventor of IPA-based Yakut scripts

- TIPA – TeX macro package providing phonetic character capabilities provides IPA support for LaTeX

- UAI phonetic alphabet – Phonetic transcription

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet – Phonetic alphabet for Uralic languages

- Voice Quality Symbols – Set of phonetic symbols used for voice quality, such as to transcribe disordered speech

- X-SAMPA – Remapping of the IPA into ASCII

Notes[edit]

- ^ The inverted bridge under the ⟨t̺ʰ⟩ specifies it as apical (pronounced with the tip of the tongue), and the superscript h shows that it is aspirated (breathy). Both these qualities cause the English /t/ to sound different from the French or Spanish /t/, which is a laminal (pronounced with the blade of the tongue) and unaspirated [t̻]. [t̺ʰ] and [t̻] are thus two different, though similar, sounds.

- ^ «Originally, the aim was to make available a set of phonetic symbols which would be given different articulatory values, if necessary, in different languages.» (International Phonetic Association, Handbook, pp. 195–196)