Economies around the world witness a combination of different market structures. While there’s a lot of competition in most industries, some industries witness just one seller. There exists no competition in such industries as there are virtually no other players. Such market structures are termed as monopolies.

But what exactly is a monopoly and how does it work?

Let’s find out.

What is a monopoly?

A monopoly is a market structure that consists of a single seller who has exclusive control over a commodity or service.

The word mono means single or one and the prefix polein finds its roots in Greek, meaning “to sell”. Hence, the word monopoly literally translates to single seller.

To understand the concept better, let’s break the definition into three key-phrases –

- Market structure: A market structure is how a market is organised. It explains the competition in the market and how different players are connected to each other.

- Single seller: A single seller is the key characteristic of a monopoly. This means that only a single seller is solely responsible for the production of output of a certain good.

- Exclusive control: Exclusive control, in this context, is the power an entity has over the production and selling of the concerned offering.

A monopoly displays characteristics that are different from other market structures. These characteristics are as follows:

- Single seller – A single seller has total control over the production, and selling of a specific offering. This also means that the seller has no competition and holds the entire market share of the offering that it deals in.

- No close substitutes – The monopolist produces a product or service that has no similar or close substitute.

- Barriers to entry – In a monopoly market structure, new firms cannot enter the industry due to barriers like government regulations, contracts, insurmountable costs of production, etc.

- Price maker – A monopolist has the power to charge any price for its product of service.

Types of monopoly

There exist several different types of monopolies in an economy. These different types of monopolies are listed below:

- Private Monopoly – A private monopoly is one that is owned by an individual or a group of individuals. These monopolies mainly aim for profits.

- Public Monopoly – A public monopoly is one that is owned by the government. These monopolies are set up for the welfare of the masses. An example of a public monopoly would be the U. S. Postal Service.

- Pure/ Absolute Monopoly – The monopolist controls the entire market supply for its product without facing any form of competition. This is possible because there is absolutely no close or remote substitute available in the market.

- Imperfect Monopoly – The monopolist controls the entire market supply for its product as there is no close substitute, but there is a remote substitute for the product available in the market.

- Simple Monopoly – A simple monopoly is one in which a single seller sells its product or service for a single price. There is no price discrimination in a simple monopoly.

- Discriminating Monopoly – A discriminating monopoly is one where a single seller does not sell his product or service for a single price. Price discrimination is witnessed wherein prices may vary from region to region, or people coming from different economic backgrounds may be charged a different price, etc.

- Legal Monopoly – A legal monopolist enjoys government approved rights like trade mark, patent, copy right, etc.

- Natural Monopoly – A natural monopolist enjoys or benefits from natural factors like locational advantages, locational reputation, natural talents and skill sets of the producers, etc.

- Technological Monopoly – When a firm holds a technologically superior position that other firms cannot compete with, the firm is said to be a technological monopoly.

- Joint Monopoly – When two or more firms join hands in order to form a monopoly, it is referred to as a joint or a shared monopoly.

Monopoly Examples

Some examples of monopolies which have great historical significance are listed below:

- Andrew Carnegie’s Steel Company (now U.S. Steel): From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Carnegie’s Steel Company maintained a singular control over steel in the US market.

- American Tobacco Company: Incorporated in North Carolina on 31 Jan. 1890 by James B. Duke, American Tobacco Company maintained a singular control over tobacco in America till 1906 and controlled four-fifths of the entire domestic tobacco industry other than cigars.

Barriers to Entry: How a Monopoly Maintains its Power

Several factors and strategies allow a monopoly to maintain the power that it holds in an industry. These essentially pose as barriers to entry to potential entrants. Some of these are:

Economies Of Scale

When it is said that the production of a certain commodity has become efficient, it means that the firm does not have to spend large amounts on the cost of production. After existing in the market for a considerable period of time, output can be generated at a larger scale with fewer input cost. This is known as economies of scale.

Due to this phenomenon, the output generated by a monopolist is large, with lesser input cost. In case a new firm tries to enter, the cost of production would be higher than that of the monopolist and the output generated would be lower than the monopolist. It is, hence, evident that the new entrant would be at a disadvantage in terms of production costs. Hence, the monopolist gains a cost advantage.

This inevitable disadvantage deters potential entrants and so, economies of scale poses as a barrier to entry.

Strategic Pricing

Strategic Pricing allows a monopolist to charge any price for their offerings. The price may be set to be extremely low – predatory pricing – in order to prevent any firm from entering the market. This is often done by a monopolist to demonstrate power and pressurise potential and existing rivals.

Sometimes, a monopolist often sets the price of its product or service just above the average cost of production of the product/service. This move ensures no competition. This is because if a competitor too decides to charge the same price for the commodity, the competitor will face losses as the cost of production for the monopolist is far lower than the competitor’s cost of production.

Ownership Of Essential And Scarce Resources

Monopolies that first enter a market have access to resources that it may choose to keep for itself. Due to this, these scarce but essential resources are made unavailable to the potential entrants.

This is often the case with natural monopolies.

High Sunk costs

Sunk costs are those which cannot be retrieved in the case a firm shuts down. These are costs that are essential for the firm, like advertising costs, but cannot be recovered.

With the existence of a large monopoly, the risk of a potential entrant going out of businesses always looms. Hence, these potential entrants hesitate when it comes to taking a risk that could cost them too much. This consequently poses as a barrier to entry.

Contracts

Monopolies maintain their power by creating contracts with suppliers and retailers.

Consumer Brand Loyalty

Consumers often develop trust and loyalty with firms that offer them quality products and services. A sense of familiarity that generates consequently deters them from going elsewhere to satisfy their demand. This does not allow other entrants a chance. Hence, they find it difficult to capture market share for the product and service that they offer.

A great example of a company using this technique to develop a monopoly is Google.

Advantages Of Monopoly

Monopolies are advantageous to economies in some ways. Some of these reasons are listed below:

- No price wars – Price wars often discompose markets. In the absence of price wars, consumers enjoy a certain degree of certainty with regards to the prices they pay for a commodity. Hence, this becomes an advantage that monopolies bring to consumers in a market.

- Large economies of scale – A monopoly has the power to produce large quantities of output at low input costs. Thus, they can and provide them to the masses at lower costs. But this advantage would benefit consumers only if the monopoly is ethical.

- More research and development- A monopoly tends to feel confident about its market share. This encourages them to go ahead and invest more in research and development. Research and development leads to the generation of new goods and services as well as enhanced manufacturing efficiencies which eventually benefits consumers.

Disadvantages Of Monopoly

The disadvantages of a monopoly in an economy often outweigh its advantages. Below listed are the disadvantages of a monopoly:

- Affects the quality of products and services offered – Due to a lack of competition, monopolists often do not realise the need to upgrade. They tend to not engage in innovating, and so, many monopolies go out of trend for the same. A good example of this could be Blackberry, a cellphone brand that captivated the global market in the early 2000s but has now been compelled to discontinue making its own smartphones in 2016. Monopolies also offer inferior products and services in an attempt to save on the cost of production. Since there are no close substitutes, consumers have no option but to buy these inferior products.

- Higher prices – A monopoly is essentially a price maker. Monopolies have the power to determine the price of their commodity without having to analyse competitor prices since there are virtually o competitors. This allows them to indulge in charging excessive prices for their commodities.

- Price discrimination – This selling strategy is employed by monopolies wherein they charge different prices for the same product in different markets. They charge a price based on what they think the consumer would agree to. For example, a product that is being sold at a relatively affluent area would be priced more than the same product that is being sold at a poor.

Go On, Tell Us What You Think!

Did we miss something? Come on! Tell us what you think about our article in the comments section.

A startup enthusiast who enjoys reading about successful entrepreneurs and writing about topics that involve the study of different markets.

Monopoly: Definition, Types, Characteristics, & Examples

by Siddhi Kamble

Monopoly Meaning

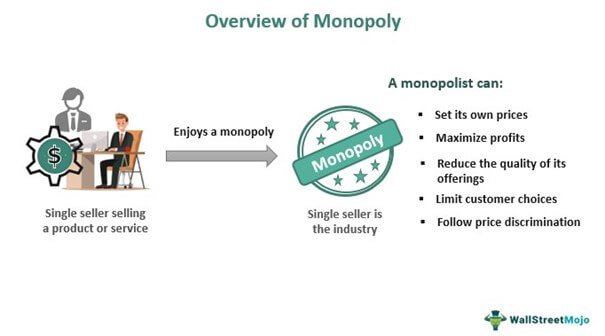

A monopoly is a market where one firm (or manufacturer) is the sole supplier of certain goods or services. This firm faces no competition due to which it can set its own prices, thereby exercising full control over the market. The monopolist aims to generate high profits by selling products (or services) that do not have close substitutes.

You are free to use this image on your website, templates, etc, Please provide us with an attribution linkArticle Link to be Hyperlinked

For eg:

Source: Monopoly (wallstreetmojo.com)

Monopolies are discouraged in several countries as power and wealth tend to concentrate with a single seller. Moreover, such sellers may offer low-quality products at high prices, thus exploiting the consumer. A monopoly can be broken by imposing government regulations or opening the market to competition.

Table of contents

- Monopoly Meaning

- Monopoly in Economics Explained

- Types of Monopoly

- #1 – Simple monopoly

- #2 – Pure monopoly

- #3 – Natural monopoly

- #4 – Legal monopoly

- #5 – Public or industrial monopoly

- Characteristics

- #1 – Maximizes profits

- #2 – Sets prices

- #3 – Poses high entry barriers

- #4 – Lacks close substitutes

- #5 – Becomes the industry

- Example

- Measuring Monopoly Power

- #1 – Lerner index

- #2 – Concentration ratio

- #3 – Price discrimination policy

- #4 – Profit rate

- #5 – Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI)

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Recommended Articles

- A monopoly consists of a single seller selling unique products or services. The monopolist has full control over the market, making it a price setter rather than a price taker.

- A monopolist can seek to maximize profits due to the absence of close substitutes, lack of competition, and barriers for new entrants.

- Monopoly power can be measured by the Lerner index, concentration ratio, price discrimination policy, profit rate, and Herfindahl-Hirschman index.

- Monopolies can be of several kinds like simple, pure, natural, legal, and public.

Monopoly in Economics Explained

Monopoly is derived from the words “monos” (single) and “polein” (to sell) of Greek. Monopoly was first depicted in The Landlord’s Game, which was invented by Elizabeth Magie Phillips (or Lizzie Magie) in 1904. This game inspired the monopoly board game that is played by most students today.

In economics, a monopoly exists when the following conditions are satisfied:

- A single seller dominates either the entire industry (or market) or a substantial percentage of the industry. This domination makes the monopolist firm a price setter (or price maker) rather than a price taker.

- There is a lack of competition in the market. Additionally, there are barriers to the entry of new firms. This implies that it is difficult to enter the market as the consumers prefer the products of the established firm over those of the new entrants. Moreover, the established firm can produce the products at low prices while the new entrants cannot do this initially.

- There is an absence of the availability of close substitutes. This implies that the consumer has no choice but to purchase from the monopolist firm.

Monopolies can often lead to unfair trade practices like charging different prices from different consumers (price discrimination), setting prices far above the costs of manufacturing, selling inferior products and services, etc. Due to these practices, a monopoly may be dissolved sooner or later.

Types of Monopoly

The different types of monopolies are discussed as follows:

#1 – Simple monopoly

A simple monopoly charges uniform prices for its product (or service) from all the buyers. In this, the monopolist firm usually operates in one market and its consumers are price takers.

#2 – Pure monopoly

A pure monopoly is the rarest form wherein the product (or service) being sold has no close substitutes. Moreover, competitors are discouraged from entering the market often due to high initial costs.

#3 – Natural monopoly

A natural monopoly depends on unique raw materials or sophisticated technology to manufacture its products. In this, the monopolist firm utilizes its copyright and patents to prevent competition. In addition, such firms usually provide public utilities (like electricity, gas, etc.), adhere to government regulations, and incur high costs on research and innovation.

#4 – Legal monopoly

A legal monopoly is one wherein the monopolist firm reserves the right to manufacture a product by way of a patent, trademark or copyright. Since the monopolist is the inventor of such a product (or process), it is the exclusive supplier in the market. Patents allow time to firms to recover the high costs of development and research.

#5 – Public or industrial monopoly

A public monopoly is set up by the government to supply important products and services. The government creates such monopolies for the following reasons:

- The costs associated with production and deliveries are too high.

- The presence of a sole supplier is considered to be more reliable and beneficial for the general public.

Public monopolies are created when the government nationalizes certain industries to serve the interest of the people.

Characteristics

The features of a monopoly are listed as follows:

#1 – Maximizes profits

The monopolist firm aims to maximize its profits owing to no rivalry and lack of consumer choices. This is the major reason a monopolist firm wants to continue enjoying its monopoly. The monopolist firms strive to earn abnormal (or supernormal) profits.

#2 – Sets prices

The single manufacturer has the power to set the prices of its products or services. The monopolist firm (price maker) may or may not charge the same price from all its consumers. The consumers (price takers) have to accept the prices set by the firm unless the government intervenes to impose a maximum price.

#3 – Poses high entry barriers

The new entrants have to face several challenges while trying to enter a monopolist market. Such challenges include high startup costs, specialized technologies, high government restrictions, complex business contracts, restricted purchase of raw materials, etc.

#4 – Lacks close substitutes

There are no products (or services) that match the offerings of the monopolist firm. The absence of close substitutes makes the demand for monopolist products relatively inelastic. The demand is inelastic when it does not change much with a change in the price of the product. Inelastic demand makes it easier to make profits in the market.

#5 – Becomes the industry

The single firm, being the sole supplier, becomes synonymous with the industry. This implies that the difference between a firm and an industry ceases to exist in the case of a monopoly.

Example

In May 2022, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), a competition regulator of the United Kingdom (UK), claimed that Google might be favoring its own services through its advertisements. However, Google charges fees from both buyers and sellers for selling a range of advertising services (like supplying online advertising space). Therefore, such favoring is against the interest of the general public and the rivals and customers of Google. The outcomes of this move are stated as follows:

- The advertisement revenues of sellers may be reduced, which will force them to lower the costs or compromise the quality of their content. As a solution, such sellers may make their content available for a subscription fee (paywalls) from the consumers.

- Businesses relying on apps to fund their content may no longer be able to reach their consumers. This would weaken competition in the long-run and may also be detrimental for the other businesses of UK.

A Google spokesperson claimed that the company’s tools account for £55 billion from over 700,000 businesses across the globe. Further, Google will continue to share the working of its systems with the CMA. This will sort matters for the company (Google) and address the concerns of the regulator (CMA).

Measuring Monopoly Power

The various methods of measuring monopoly power are listed as follows:

#1 – Lerner index

The economist Abba P. Lerner proposed the Lerner index. According to this measure, the higher the monopolist firm charges above the marginal cost, the higher its monopoly power is said to be.

Lerner Index (L)=(Price-Marginal Cost)/Price

The value of L ranges from 0 to 1. Zero implies no monopoly power and one implies maximum power. L depends on factors like elasticity of demand, presence of competitors, extent of regulations, etc.

#2 – Concentration ratio

The concentration ratio indicates the extent of competition prevalent in an industry. The ratio can range from 0 to 100%. Zero implies the existence of a large number of firms (high competition) and one implies the absence of competitors (no competition or a monopoly).

#3 – Price discrimination policy

Price discrimination exists if a firm charges different prices from different consumers. High price discrimination implies more control of the monopolist over the prices. Further, the elasticity of demand is also an indicator of monopoly power.

#4 – Profit rate

The profit rate measure indicates that the higher the profit a firm makes, the greater its monopoly power. Earning low profits indicates a competitive market, while earning supernormal profits indicates a monopoly.

#5 – Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI)

The Herfindahl-Hirschman index indicates the competition or the market concentration of an industry. It is obtained by squaring the size of the different firms in the industry and summing the resulting numbers. HHI can range from 0 to 1 or from 0 to 10000 points. Lower HHI indicates more competition, while a higher one indicates less or no competition (i.e., monopoly).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What companies are monopolies?

The companies that are the sole supplier of a product or service in the industry enjoy a monopoly. The offerings of such companies are unique, thereby eliminating competitors and the resulting conflicts.

2. Is a monopoly illegal?

A monopoly that tends to defraud the customer through extremely high prices and inferior quality goods is considered to be illegal. Therefore, such monopolies are discouraged and dissolved by government intervention.

However, companies operating in sectors like oil, gas, water, electricity, etc., are government-owned monopolies. Such companies need to adhere to government policies while conducting business. Hence, these monopolies are not illegal.

3. Why is a monopoly bad?

A monopolist firm may be considered bad for the following reasons:

• It may become negligent towards the quality delivered due to lack of rivalry.

• It may charge increased prices even though its manufacturing costs may be low.

• It may follow policies that maximize profits rather than those that serve the best interest of the society and environment.

• It may indulge in price discrimination wherein different customers are charged different prices.

• It may limit the choices of the customer as one can purchase from only one firm.

Recommended Articles

This article has been a guide to Monopoly and its meaning. Here, we explain the types, characteristics, and working of monopoly, along with an example. You can learn more from the following articles–

- Monopoly vs Oligopoly

- Monopoly vs Monopolistic Competition

- Monopoly Examples

A monopoly (from Greek μόνος, mónos, ‘single, alone’ and πωλεῖν, pōleîn, ‘to sell’), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the «absence of competition», creating a situation where a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular thing. This contrasts with a monopsony which relates to a single entity’s control of a market to purchase a good or service, and with oligopoly and duopoly which consists of a few sellers dominating a market.[1] Monopolies are thus characterised by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller’s marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit.[2] The verb monopolise or monopolize refers to the process by which a company gains the ability to raise prices or exclude competitors. In economics, a monopoly is a single seller. In law, a monopoly is a business entity that has significant market power, that is, the power to charge overly high prices, which is associated with a decrease in social surplus.[3] Although monopolies may be big businesses, size is not a characteristic of a monopoly. A small business may still have the power to raise prices in a small industry (or market).[3]

A monopoly may also have monopsony control of a sector of a market. Likewise, a monopoly should be distinguished from a cartel (a form of oligopoly), in which several providers act together to coordinate services, prices or sale of goods. Monopolies, monopsonies and oligopolies are all situations in which one or a few entities have market power and therefore interact with their customers (monopoly or oligopoly), or suppliers (monopsony) in ways that distort the market.[citation needed]

Monopolies can be established by a government, form naturally, or form by integration. In many jurisdictions, competition laws restrict monopolies due to government concerns over potential adverse effects. Holding a dominant position or a monopoly in a market is often not illegal in itself, however certain categories of behavior can be considered abusive and therefore incur legal sanctions when business is dominant. A government-granted monopoly or legal monopoly, by contrast, is sanctioned by the state, often to provide an incentive to invest in a risky venture or enrich a domestic interest group. Patents, copyrights, and trademarks are sometimes used as examples of government-granted monopolies. The government may also reserve the venture for itself, thus forming a government monopoly, for example with a state-owned company.[citation needed]

Monopolies may be naturally occurring due to limited competition because the industry is resource intensive and requires substantial costs to operate (e.g., certain railroad systems).[4]

| one | two | few | |

| sellers | monopoly | duopoly | oligopoly |

| buyers | monopsony | duopsony | oligopsony |

Market structuresEdit

Market structure is determined by following factors:

- Barriers to entry: Competition within the market will determine the firm’s future profits, and future profits will determine the entry and exit barriers to the market. Estimating entry, exit and profits are decided by three factors: the intensity of competition in short-term prices, the magnitude of sunk costs of entry faced by potential entrants, and the magnitude of fixed costs faced by incumbents.[5]

- The number of companies in the market: If the number of firms in the market increases, the value of firms remaining and entering the market will decrease, leading to a high probability of exit and a reduced likelihood of entry.

- Product substitutability: Product substitution is the phenomenon where customers can choose one over another. This is the main way to distinguish a monopolistic competition market from a perfect competition market.

In economics, the idea of monopolies is important in the study of management structures, which directly concerns normative aspects of economic competition, and provides the basis for topics such as industrial organization and economics of regulation. There are four basic types of market structures in traditional economic analysis: perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly and monopoly. A monopoly is a structure in which a single supplier produces and sells a given product or service. If there is a single seller in a certain market and there are no close substitutes for the product, then the market structure is that of a «pure monopoly». Sometimes, there are many sellers in an industry or there exist many close substitutes for the goods being produced, but nevertheless, companies retain some market power. This is termed «monopolistic competition», whereas in an oligopoly, the companies interact strategically.

In general, the main results from this theory compare the price-fixing methods across market structures, analyze the effect of a certain structure on welfare, and vary technological or demand assumptions in order to assess the consequences for an abstract model of society. Most economic textbooks follow the practice of carefully explaining the «perfect competition» model, mainly because this helps to understand departures from it (the so-called «imperfect competition» models).

The boundaries of what constitutes a market and what does not are relevant distinctions to make in economic analysis. In a general equilibrium context, a good is a specific concept including geographical and time-related characteristics. Most studies of market structure relax a little their definition of a good, allowing for more flexibility in the identification of substitute goods.

CharacteristicsEdit

A monopoly has at least one of these five characteristics:

- Profit maximizer: monopolists will choose the price or output to maximase profits at where MC=MR.This output will be somewhere over the price range, where demand is price elastic. If the total revenue is higher than total costs, the monopolists will make abnormal profits.

- Price maker: Decides the price of the good or product to be sold, but does so by determining the quantity in order to demand the price desired by the firm.

- High barriers to entry: Other sellers are unable to enter the market of the monopoly.

- Single seller: In a monopoly, there is one seller of the good, who produces all the output.[6] Therefore, the whole market is being served by a single company, and for practical purposes, the company is the same as the industry.

- Price discrimination: A monopolist can change the price or quantity of the product. They sell higher quantities at a lower price in a very elastic market, and sell lower quantities at a higher price in a less elastic market.

Sources of monopoly powerEdit

Monopolies derive their market power from barriers to entry – circumstances that prevent or greatly impede a potential competitor’s ability to compete in a market. There are three major types of barriers to entry: economic, legal and deliberate.[7]

- Elasticity of demand: In a complete monopolistic market, the demand curve for the product is the market demand curve. There is only one firm within the industry. The monopolist is the sole seller, and its demand is the demand of the entire market. A monopolist is the price setter, but it is also limited by the law of market demand. If he/she sets a high price, the sales volume will inevitably decline, if expand the sales volume, the price must be lowered, which means that the demand and price in the monopoly market move in opposite directions. Therefore, the demand curve faced by a monopoly is a downward sloping curve, or a negative slope. Since monopolists control the supply of the entire industry, they also control the price of the entire industry and become price setters. A monopolistic firm can have two business decisions: sell less output at a higher price, or sell more output at a lower price. There are no close substitutes for the products of a monopolistic firm. Otherwise, other firms can produce substitutes to replace the monopoly firm’s products, and a monopolistic firm cannot become the only supplier in the market. So consumers have no other choice.

- Economic barriers: Economic barriers include economies of scale, capital requirements, cost advantages and technological superiority.[8]

- Economies of scale: Decreasing unit costs for larger volumes of production.[9] Decreasing costs coupled with large initial costs, If for example the industry is large enough to support one company of minimum efficient scale then other companies entering the industry will operate at a size that is less than MES, and so cannot produce at an average cost that is competitive with the dominant company. And if the long-term average cost of the dominant company is constantly decreasing[clarification needed], then that company will continue to have the least cost method to provide a good or service.[10]

- Capital requirements: Production processes that require large investments of capital, perhaps in the form of large research and development costs or substantial sunk costs, limit the number of companies in an industry:[11] this is an example of economies of scale.

- Technological superiority: A monopoly may be better able to acquire, integrate and use the best possible technology in producing its goods while entrants either do not have the expertise or are unable to meet the large fixed costs (see above) needed for the most efficient technology.[9] Thus one large company can often produce goods cheaper than several small companies.[12]

- No substitute goods: A monopoly sells a good for which there is no close substitute. The absence of substitutes makes the demand for that good relatively inelastic, enabling monopolies to extract positive profits.

- Control of natural resources: A prime source of monopoly power is the control of resources (such as raw materials) that are critical to the production of a final good.

- Network externalities: The use of a product by a person can affect the value of that product to other people. This is the network effect. There is a direct relationship between the proportion of people using a product and the demand for that product. In other words, the more people who are using a product, the greater the probability that another individual will start to use the product. This reflects fads, fashion trends,[13] social networks etc. It also can play a crucial role in the development or acquisition of market power. The most famous current example is the market dominance of the Microsoft office suite and operating system in personal computers.[citation needed]

- Legal barriers: Legal rights can provide opportunity to monopolise the market in a good. Intellectual property rights, including patents and copyrights, give a monopolist exclusive control of the production and selling of certain goods. Property rights may give a company exclusive control of the materials necessary to produce a good.

- Advertising: Advertising and brand names with a high degree of consumer loyalty may prove a difficult obstacle to overcome.

- Manipulation: A company wanting to monopolise a market may engage in various types of deliberate action to exclude competitors or eliminate competition. Such actions include collusion, lobbying governmental authorities, and force (see anti-competitive practices).

- First-mover advantage: In some industries such as electronics, the pace of product innovation is so rapid that the existing firms will be working on the next generation of products whilst launching the current ranges. New entrants are destined to fail unless they have original ideas or can exploit a new market segment.

- Monopolistic price: It may be possible for existing firms to ride the existence of abnormal profit by what is called entry limit pricing. This involves deliberately setting a low price and temporarily abandoning profit maximisation in order to force new entrants out of the market.

In addition to barriers to entry and competition, barriers to exit may be a source of market power. Barriers to exit are market conditions that make it difficult or expensive for a company to end its involvement with a market. High liquidation costs are a primary barrier to exiting.[14] Market exit and shutdown are sometimes separate events. The decision whether to shut down or operate is not affected by exit barriers.[citation needed] A company will shut down if price falls below minimum average variable costs.

Monopoly versus competitive marketsEdit

This 1879 anti-monopoly cartoon depicts powerful railroad barons controlling the entire rail system.

While monopoly and perfect competition mark the extremes of market structures[15] there is some similarity. The cost functions are the same.[16] Both monopolies and perfectly competitive (PC) companies minimize cost and maximize profit. The shutdown decisions are the same. Both are assumed to have perfectly competitive factors markets. There are distinctions, some of the most important distinctions are as follows:

- Marginal revenue and price: In a perfectly competitive market, price equals marginal cost. In a monopolistic market, however, price is set above marginal cost. The price equal marginal revenue in this case.[17]

- Product differentiation: There is no product differentiation in a perfectly competitive market. Every product is perfectly homogeneous and a perfect substitute for any other. With a monopoly, there is great to absolute product differentiation in the sense that there is no available substitute for a monopolized good. The monopolist is the sole supplier of the good in question.[18] A customer either buys from the monopolizing entity on its terms or does without.

- Number of competitors: PC markets are populated by a large number of buyers and sellers. A monopoly involves a single seller.[18]

- Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry are factors and circumstances that prevent entry into market by would-be competitors and limit new companies from operating and expanding within the market. PC markets have free entry and exit. There are no barriers to entry, or exit competition. Monopolies have relatively high barriers to entry. The barriers must be strong enough to prevent or discourage any potential competitor from entering the market

- Elasticity of demand: The price elasticity of demand is the percentage change of demand caused by a one percent change of relative price. A successful monopoly would have a relatively inelastic demand curve. A low coefficient of elasticity is indicative of effective barriers to entry. A PC company has a perfectly elastic demand curve. The coefficient of elasticity for a perfectly competitive demand curve is infinite.[citation needed]

- Excess profits: Excess or positive profits are profit more than the normal expected return on investment. A PC company can make excess profits in the short term but excess profits attract competitors, which can enter the market freely and decrease prices, eventually reducing excess profits to zero.[19] A monopoly can preserve excess profits because barriers to entry prevent competitors from entering the market.[20]

- Profit maximization: A PC company maximizes profits by producing such that price equals marginal costs. A monopoly maximises profits by producing where marginal revenue equals marginal costs.[21] The rules are not equivalent. The demand curve for a PC company is perfectly elastic – flat. The demand curve is identical to the average revenue curve and the price line. Since the average revenue curve is constant the marginal revenue curve is also constant and equals the demand curve, Average revenue is the same as price ( ). Thus the price line is also identical to the demand curve. In sum, .

- P-Max quantity, price and profit: If a monopolist obtains control of a formerly perfectly competitive industry, the monopolist would increase prices, reduce production, incur deadweight loss, and realise positive economic profits.[22]

- Supply curve: in a perfectly competitive market there is a well defined supply function with a one-to-one relationship between price and quantity supplied.[23] In a monopolistic market no such supply relationship exists. A monopolist cannot trace a short-term supply curve because for a given price there is not a unique quantity supplied. As Pindyck and Rubenfeld note, a change in demand «can lead to changes in prices with no change in output, changes in output with no change in price or both».[24] Monopolies produce where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. For a specific demand curve the supply «curve» would be the price-quantity combination at the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. If the demand curve shifted the marginal revenue curve would shift as well and a new equilibrium and supply «point» would be established. The locus of these points would not be a supply curve in any conventional sense.[25][26]

The most significant distinction between a PC company and a monopoly is that the monopoly has a downward-sloping demand curve rather than the «perceived» perfectly elastic curve of the PC company.[27] Practically all the variations mentioned above relate to this fact. If there is a downward-sloping demand curve then by necessity there is a distinct marginal revenue curve. The implications of this fact are best made manifest with a linear demand curve. Assume that the inverse demand curve is of the form . Then the total revenue curve is and the marginal revenue curve is thus . From this several things are evident. First, the marginal revenue curve has the same -intercept as the inverse demand curve. Second, the slope of the marginal revenue curve is twice that of the inverse demand curve. What is not quite so evident is that the marginal revenue curve is below the inverse demand curve at all points ( ).[27] Since all companies maximise profits by equating and it must be the case that at the profit-maximizing quantity MR and MC are less than price, which further implies that a monopoly produces less quantity at a higher price than if the market were perfectly competitive.

The fact that a monopoly has a downward-sloping demand curve means that the relationship between total revenue and output for a monopoly is much different than that of competitive companies.[28] Total revenue equals price times quantity. A competitive company has a perfectly elastic demand curve meaning that total revenue is proportional to output.[28] Thus the total revenue curve for a competitive company is a ray with a slope equal to the market price.[28] A competitive company can sell all the output it desires at the market price. For a monopoly to increase sales it must reduce price. Thus the total revenue curve for a monopoly is a parabola that begins at the origin and reaches a maximum value then continuously decreases until total revenue is again zero.[29] Total revenue has its maximum value when the slope of the total revenue function is zero. The slope of the total revenue function is marginal revenue. So the revenue maximizing quantity and price occur when . For example, assume that the monopoly’s demand function is . The total revenue function would be and marginal revenue would be . Setting marginal revenue equal to zero we have

So the revenue maximizing quantity for the monopoly is 12.5 units and the revenue-maximizing price is 25.

A company with a monopoly does not experience price pressure from competitors, although it may experience pricing pressure from potential competition. If a company increases prices too much, then others may enter the market if they are able to provide the same good, or a substitute, at a lesser price.[30] The idea that monopolies in markets with easy entry need not be regulated against is known as the «revolution in monopoly theory».[31]

A monopolist can extract only one premium,[clarification needed] and getting into complementary markets does not pay. That is, the total profits a monopolist could earn if it sought to leverage its monopoly in one market by monopolizing a complementary market are equal to the extra profits it could earn anyway by charging more for the monopoly product itself. However, the one monopoly profit theorem is not true if customers in the monopoly good are stranded or poorly informed, or if the tied good has high fixed costs.

A pure monopoly has the same economic rationality of perfectly competitive companies, i.e. to optimise a profit function given some constraints. By the assumptions of increasing marginal costs, exogenous inputs’ prices, and control concentrated on a single agent or entrepreneur, the optimal decision is to equate the marginal cost and marginal revenue of production. Nonetheless, a pure monopoly can – unlike a competitive company – alter the market price for its own convenience: a decrease of production results in a higher price. In the economics’ jargon, it is said that pure monopolies have «a downward-sloping demand». An important consequence of such behaviour is that typically a monopoly selects a higher price and lesser quantity of output than a price-taking company; again, less is available at a higher price.[32]

Inverse elasticity ruleEdit

A monopoly chooses that price that maximizes the difference between total revenue and total cost. The basic markup rule (as measured by the Lerner index) can be expressed as

,

where is the price elasticity of demand the firm faces.[33] The markup rules indicate that the ratio between profit margin and the price is inversely proportional to the price elasticity of demand.[33] The implication of the rule is that the more elastic the demand for the product the less pricing power the monopoly has.

Market powerEdit

Market power is the ability to increase the product’s price above marginal cost without losing all customers.[34] Perfectly competitive (PC) companies have zero market power when it comes to setting prices. All companies of a PC market are price takers. The price is set by the interaction of demand and supply at the market or aggregate level. Individual companies simply take the price determined by the market and produce that quantity of output that maximizes the company’s profits. If a PC company attempted to increase prices above the market level all its customers would abandon the company and purchase at the market price from other companies. A monopoly has considerable although not unlimited market power. A monopoly has the power to set prices or quantities although not both.[35] A monopoly is a price maker.[36] The monopoly is the market[37] and prices are set by the monopolist based on their circumstances and not the interaction of demand and supply. The two primary factors determining monopoly market power are the company’s demand curve and its cost structure.[38]

Market power is the ability to affect the terms and conditions of exchange so that the price of a product is set by a single company (price is not imposed by the market as in perfect competition).[39][40] Although a monopoly’s market power is great it is still limited by the demand side of the market. A monopoly has a negatively sloped demand curve, not a perfectly inelastic curve. Consequently, any price increase will result in the loss of some customers.

Price discriminationEdit

Price discrimination allows a monopolist to increase its profit by charging higher prices for identical goods to those who are willing or able to pay more. For example, most economic textbooks cost more in the United States than in developing countries like Ethiopia. In this case, the publisher is using its government-granted copyright monopoly to price discriminate between the generally wealthier American economics students and the generally poorer Ethiopian economics students. Similarly, most patented medications cost more in the U.S. than in other countries with a (presumed) poorer customer base. Typically, a high general price is listed, and various market segments get varying discounts. This is an example of framing to make the process of charging some people higher prices more socially acceptable.[citation needed] Perfect price discrimination would allow the monopolist to charge each customer the exact maximum amount they would be willing to pay. This would allow the monopolist to extract all the consumer surplus of the market. A domestic example would be the cost of airplane flights in relation to their takeoff time; the closer they are to flight, the higher the plane tickets will cost, discriminating against late planners and often business flyers. While such perfect price discrimination is a theoretical construct, advances in information technology and micromarketing may bring it closer to the realm of possibility.

Partial price discrimination can cause some customers who are inappropriately pooled with high price customers to be excluded from the market. For example, a poor student in the U.S. might be excluded from purchasing an economics textbook at the U.S. price, which the student may have been able to purchase at the Ethiopian price. Similarly, a wealthy student in Ethiopia may be able to or willing to buy at the U.S. price, though naturally would hide such a fact from the monopolist so as to pay the reduced third world price. These are deadweight losses and decrease a monopolist’s profits. Deadweight loss is considered detrimental to society and market participation. As such, monopolists have substantial economic interest in improving their market information and market segmenting.[41]

There is important information for one to remember when considering the monopoly model diagram (and its associated conclusions) displayed here. The result that monopoly prices are higher, and production output lesser, than a competitive company follow from a requirement that the monopoly not charge different prices for different customers. That is, the monopoly is restricted from engaging in price discrimination (this is termed first degree price discrimination, such that all customers are charged the same amount). If the monopoly were permitted to charge individualised prices (this is termed third degree price discrimination), the quantity produced, and the price charged to the marginal customer, would be identical to that of a competitive company, thus eliminating the deadweight loss; however, all gains from trade (social welfare) would accrue to the monopolist and none to the consumer. In essence, every consumer would be indifferent between going completely without the product or service and being able to purchase it from the monopolist.[citation needed]

As long as the price elasticity of demand for most customers is less than one in absolute value, it is advantageous for a company to increase its prices: it receives more money for fewer goods. With a price increase, price elasticity tends to increase, and in the optimum case above it will be greater than one for most customers.[citation needed]

A company maximizes profit by selling where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. A company that does not engage in price discrimination will charge the profit maximizing price, , to all its customers. In such circumstances there are customers who would be willing to pay a higher price than and those who will not pay but would buy at a lower price. A price discrimination strategy is to charge less price sensitive buyers a higher price and the more price sensitive buyers a lower price.[42] Thus additional revenue is generated from two sources. The basic problem is to identify customers by their willingness to pay.

The purpose of price discrimination is to transfer consumer surplus to the producer.[43] Consumer surplus is the difference between the value of a good to a consumer and the price the consumer must pay in the market to purchase it.[44] Price discrimination is not limited to monopolies.

Market power is a company’s ability to increase prices without losing all its customers. Any company that has market power can engage in price discrimination. Perfect competition is the only market form in which price discrimination would be impossible (a perfectly competitive company has a perfectly elastic demand curve and has no market power).[43][45][46][47]

There are three forms of price discrimination. First degree price discrimination charges each consumer the maximum price the consumer is willing to pay. Second degree price discrimination involves quantity discounts. Third degree price discrimination involves grouping consumers according to willingness to pay as measured by their price elasticities of demand and charging each group a different price. Third degree price discrimination is the most prevalent type.[48]

There are three conditions that must be present for a company to engage in successful price discrimination. First, the company must have market power.[49] Second, the company must be able to sort customers according to their willingness to pay for the good.[50] Third, the firm must be able to prevent resell.

A company must have some degree of market power to practice price discrimination. Without market power a company cannot charge more than the market price.[51] Any market structure characterized by a downward sloping demand curve has market power – monopoly, monopolistic competition and oligopoly.[49] The only market structure that has no market power is perfect competition.[51]

A company wishing to practice price discrimination must be able to prevent middlemen or brokers from acquiring the consumer surplus for themselves. The company accomplishes this by preventing or limiting resale. Many methods are used to prevent resale. For instance, persons are required to show photographic identification and a boarding pass before boarding an airplane. Most travelers assume that this practice is strictly a matter of security. However, a primary purpose in requesting photographic identification is to confirm that the ticket purchaser is the person about to board the airplane and not someone who has repurchased the ticket from a discount buyer.[citation needed]

The inability to prevent resale is the largest obstacle to successful price discrimination.[45] Companies have however developed numerous methods to prevent resale. For example, universities require that students show identification before entering sporting events. Governments may make it illegal to resell tickets or products. In Boston, Red Sox baseball tickets can only be resold legally to the team.

The three basic forms of price discrimination are first, second and third degree price discrimination. In first degree price discrimination the company charges the maximum price each customer is willing to pay. The maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a unit of the good is the reservation price. Thus for each unit the seller tries to set the price equal to the consumer’s reservation price.[52] Direct information about a consumer’s willingness to pay is rarely available. Sellers tend to rely on secondary information such as where a person lives (postal codes); for example, catalog retailers can use mail high-priced catalogs to high-income postal codes.[53][54] First degree price discrimination most frequently occurs in regard to professional services or in transactions involving direct buyer-seller negotiations. For example, an accountant who has prepared a consumer’s tax return has information that can be used to charge customers based on an estimate of their ability to pay.[a]

In second degree price discrimination or quantity discrimination customers are charged different prices based on how much they buy. There is a single price schedule for all consumers but the prices vary depending on the quantity of the good bought.[55] The theory of second degree price discrimination is a consumer is willing to buy only a certain quantity of a good at a given price. Companies know that consumer’s willingness to buy decreases as more units are purchased[citation needed]. The task for the seller is to identify these price points and to reduce the price once one is reached in the hope that a reduced price will trigger additional purchases from the consumer. For example, sell in unit blocks rather than individual units.

In third degree price discrimination or multi-market price discrimination[56] the seller divides the consumers into different groups according to their willingness to pay as measured by their price elasticity of demand. Each group of consumers effectively becomes a separate market with its own demand curve and marginal revenue curve.[46] The firm then attempts to maximize profits in each segment by equating MR and MC,[49][57][58] Generally the company charges a higher price to the group with a more price inelastic demand and a relatively lesser price to the group with a more elastic demand.[59] Examples of third degree price discrimination abound. Airlines charge higher prices to business travelers than to vacation travelers. The reasoning is that the demand curve for a vacation traveler is relatively elastic while the demand curve for a business traveler is relatively inelastic. Any determinant of price elasticity of demand can be used to segment markets. For example, seniors have a more elastic demand for movies than do young adults because they generally have more free time. Thus theaters will offer discount tickets to seniors.[b]

ExampleEdit

Assume that by a uniform pricing system the monopolist would sell five units at a price of $10 per unit. Assume that his marginal cost is $5 per unit. Total revenue would be $50, total costs would be $25 and profits would be $25. If the monopolist practiced price discrimination he would sell the first unit for $17 the second unit for $14 and so on which is listed in the table below. Total revenue would be $55, his total cost would be $25 and his profit would be $30.[60] Several things are worth noting. The monopolist acquires all the consumer surplus and eliminates practically all the deadweight loss because he is willing to sell to anyone who is willing to pay at least the marginal cost.[60] Thus the price discrimination promotes efficiency. Secondly, by the pricing scheme price = average revenue and equals marginal revenue. That is the monopolist behaving like a perfectly competitive company.[61] Thirdly, the discriminating monopolist produces a larger quantity than the monopolist operating by a uniform pricing scheme.[62]

| Qd | Price |

|---|---|

| 1 | $17 |

| 2 | $14 |

| 3 | $11 |

| 4 | $8 |

| 5 | $5 |

Classifying customersEdit

Successful price discrimination requires that companies separate consumers according to their willingness to buy. Determining a customer’s willingness to buy a good is difficult. Asking consumers directly is fruitless: consumers don’t know, and to the extent they do they are reluctant to share that information with marketers. The two main methods for determining willingness to buy are observation of personal characteristics and consumer actions. As noted information about where a person lives (postal codes), how the person dresses, what kind of car he or she drives, occupation, and income and spending patterns can be helpful in classifying.[citation needed]

Monopoly and efficiencyEdit

The price of monopoly is upon every occasion the highest which can be got. The natural price, or the price of free competition, on the contrary, is the lowest which can be taken, not upon every occasion indeed, but for any considerable time together. The one is upon every occasion the highest which can be squeezed out of the buyers, or which it is supposed they will consent to give; the other is the lowest which the sellers can commonly afford to take, and at the same time continue their business.[63]: 56

…Monopoly, besides, is a great enemy to good management.[63]: 127

– Adam Smith (1776), The Wealth of Nations

According to the standard model, in which a monopolist sets a single price for all consumers, the monopolist will sell a lesser quantity of goods at a higher price than would companies by perfect competition. Because the monopolist ultimately forgoes transactions with consumers who value the product or service less than its price, monopoly pricing creates a deadweight loss referring to potential gains that went neither to the monopolist nor to consumers. Deadweight loss is the cost to society because the market is not in equilibrium, it is inefficient. Given the presence of this deadweight loss, the combined surplus (or wealth) for the monopolist and consumers is necessarily less than the total surplus obtained by consumers by perfect competition. Where efficiency is defined by the total gains from trade, the monopoly setting is less efficient than perfect competition.[64]

It is often argued that monopolies tend to become less efficient and less innovative over time, becoming «complacent», because they do not have to be efficient or innovative to compete in the marketplace. Sometimes this very loss of psychological efficiency can increase a potential competitor’s value enough to overcome market entry barriers, or provide incentive for research and investment into new alternatives. The theory of contestable markets argues that in some circumstances (private) monopolies are forced to behave as if there were competition because of the risk of losing their monopoly to new entrants. This is likely to happen when a market’s barriers to entry are low. It might also be because of the availability in the longer term of substitutes in other markets. For example, a canal monopoly, while worth a great deal during the late 18th century United Kingdom, was worth much less during the late 19th century because of the introduction of railways as a substitute.[citation needed]

Contrary to common misconception,[according to whom?] monopolists do not try to sell items for the highest possible price, nor do they try to maximize profit per unit, but rather they try to maximize total profit.[65][full citation needed]

Natural monopolyEdit

A natural monopoly is an organization that experiences increasing returns to scale over the relevant range of output and relatively high fixed costs.[66] A natural monopoly occurs where the average cost of production «declines throughout the relevant range of product demand». The relevant range of product demand is where the average cost curve is below the demand curve.[67] When this situation occurs, it is always more efficient for one large company to supply the market than multiple smaller companies; in fact, absent government intervention in such markets, will naturally evolve into a monopoly. Often, a natural monopoly is the outcome of an initial rivalry between several competitors. An early market entrant that takes advantage of the cost structure and can expand rapidly can exclude smaller companies from entering and can drive or buy out other companies. A natural monopoly suffers from the same inefficiencies as any other monopoly. Left to its own devices, a profit-seeking natural monopoly will produce where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. Regulation of natural monopolies is problematic.[citation needed] Fragmenting such monopolies is by definition inefficient. The most frequently used methods dealing with natural monopolies are government regulations and public ownership. Government regulation generally consists of regulatory commissions charged with the principal duty of setting prices.[68] Natural monopolies are synonymous with what is called «single-unit enterprise», a term which was used in the 1914 book Social Economics written by Friedrich von Wieser. As mentioned, government regulations are frequently used with natural monopolies to help control prices. An example that can illustrate this can be found when looking at the United States Postal Service, which has a monopoly over types of mail. According to Wieser, the idea of a competitive market within the postal industry would lead to extreme prices and unnecessary spending, and this highlighted why government regulation in the form of price control is necessary as it helped efficient market.[69]

To reduce prices and increase output, regulators often use average cost pricing. By average cost pricing, the price and quantity are determined by the intersection of the average cost curve and the demand curve.[70] This pricing scheme eliminates any positive economic profits since price equals average cost. Average-cost pricing is not perfect. Regulators must estimate average costs. Companies have a reduced incentive to lower costs. Regulation of this type has not been limited to natural monopolies.[70] Average-cost pricing does also have some disadvantages. By setting price equal to the intersection of the demand curve and the average total cost curve, the firm’s output is allocatively inefficient as the price is less than the marginal cost (which is the output quantity for a perfectly competitive and allocatively efficient market).

In 1848, J.S. Mill was the first individual to describe monopolies with the adjective «natural». He used it interchangeably with «practical». At the time, Mill gave the following examples of natural or practical monopolies: gas supply, water supply, roads, canals, and railways. In his Social Economics,[71] Friedrich von Wieser demonstrated his view of the postal service as a natural monopoly: «In the face of [such] single-unit administration, the principle of competition becomes utterly abortive. The parallel network of another postal organization, beside the one already functioning, would be economically absurd; enormous amounts of money for plant and management would have to be expended for no purpose whatever.»[71]

Overall, most monopolies are man-made monopolies, or unnatural monopolies, not natural ones.

Government-granted monopolyEdit

A government-granted monopoly (also called a «de jure monopoly») is a form of coercive monopoly, in which a government grants exclusive privilege to a private individual or company to be the sole provider of a commodity. Monopoly may be granted explicitly, as when potential competitors are excluded from the market by a specific law, or implicitly, such as when the requirements of an administrative regulation can only be fulfilled by a single market player, or through some other legal or procedural mechanism, such as patents, trademarks, and copyright. These monopolies can also be the result of «rent-seeking» behavior, where firms will try to get the prize of having a monopoly, and the increase of profits in acquiring one from a competitive market in their sector.[72]

Monopolist shutdown ruleEdit

A monopolist should shut down[according to whom?] when price is less than average variable cost for every output level[73] – in other words where the demand curve is entirely below the average variable cost curve.[73] Under these circumstances at the profit maximum level of output (MR = MC) average revenue would be less than average variable costs and the monopolists would be better off shutting down in the short term.[73]

Breaking up monopoliesEdit

In an unregulated market, monopolies can potentially be ended by new competition, breakaway businesses, or consumers seeking alternatives. In a regulated market, a government will often either regulate the monopoly, convert it into a publicly owned monopoly environment, or forcibly fragment it (see Antitrust law and trust busting). Public utilities, often being naturally efficient with only one operator and therefore less susceptible to efficient breakup, are often strongly regulated or publicly owned. American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T) and Standard Oil are often cited as examples of the breakup of a private monopoly by government. The Bell System, later AT&T, was protected from competition first by the Kingsbury Commitment, and later by a series of agreements between AT&T and the Federal Government. In 1984, decades after having been granted monopoly power by force of law, AT&T was broken up into various components, MCI, Sprint, who were able to compete effectively in the long-distance phone market. These breakups are due to the presence of deadweight loss and inefficiency in a monopolistic market, causing the Government to intervene on behalf of consumers and society in order to incite competition.[citation needed] While the sentiment among regulators and judges has generally recommended that breakups are not as remedies for antitrust enforcement, recent scholarship has found that this hostility to breakups by administrators is largely unwarranted.[74]: 1 In fact, some scholars have argued breakups, even if incorrectly targeted, could arguably still encourage collaboration, innovation, and efficiency.[74]: 49

LawEdit

A 1902 anti-monopoly cartoon depicts the challenges that monopolies may create for workers.

The law regulating dominance in the European Union is governed by Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which aims at enhancing the consumer’s welfare and also the efficiency of allocation of resources by protecting competition on the downstream market.[75] The existence of a very high market share does not always mean consumers are paying excessive prices since the threat of new entrants to the market can restrain a high-market-share company’s price increases. Competition law does not make merely having a monopoly illegal, but rather abusing the power a monopoly may confer, for instance through exclusionary practices (i.e. pricing high just because it is the only one around.) It may also be noted that it is illegal to try to obtain a monopoly, by practices of buying out the competition, or equal practices. If one occurs naturally, such as a competitor going out of business, or lack of competition, it is not illegal until such time as the monopoly holder abuses the power.

Establishing dominanceEdit

First it is necessary to determine whether a company is dominant, or whether it behaves «to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer». Establishing dominance is a two-stage test. The first thing to consider is market definition which is one of the crucial factors of the test.[76] It includes relevant product market and relevant geographic market.

Relevant product marketEdit

As the definition of the market is of a matter of interchangeability, if the goods or services are regarded as interchangeable then they are within the same product market.[77] For example, in the case of United Brands v Commission,[78] it was argued in this case that bananas and other fresh fruit were in the same product market and later on dominance was found because the special features of the banana made it could only be interchangeable with other fresh fruits in a limited extent and other and is only exposed to their competition in a way that is hardly perceptible. The demand substitutability of the goods and services will help in defining the product market and it can be access by the ‘hypothetical monopolist’ test or the ‘SSNIP’ test.[79]

Relevant geographic marketEdit

It is necessary to define it because some goods can only be supplied within a narrow area due to technical, practical or legal reasons and this may help to indicate which undertakings impose a competitive constraint on the other undertakings in question. Since some goods are too expensive to transport where it might not be economic to sell them to distant markets in relation to their value, therefore the cost of transporting is a crucial factor here. Other factors might be legal controls which restricts an undertaking in a Member States from exporting goods or services to another.

Market definition may be difficult to measure but is important because if it is defined too narrowly, the undertaking may be more likely to be found dominant and if it is defined too broadly, the less likely that it will be found dominant.

Market sharesEdit

As with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with reference to the particular market in which the company and product in question is sold. It does not in itself determine whether an undertaking is dominant but work as an indicator of the states of the existing competition within the market. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) is sometimes used to assess how competitive an industry is. It sums up the squares of the individual market shares of all of the competitors within the market. The lower the total, the less concentrated the market and the higher the total, the more concentrated the market.[80] In the US, the merger guidelines state that a post-merger HHI below 1000 is viewed as not concentrated while HHIs above that will provoke further review.

By European Union law, very large market shares raise a presumption that a company is dominant, which may be rebuttable. A market share of 100% may be very rare but it is still possible to be found and in fact it has been identified in some cases, for instance the AAMS v Commission case.[81] Undertakings possessing market share that is lower than 100% but over 90% had also been found dominant, for example, Microsoft v Commission case.[82] In the AKZO v Commission case,[83] the undertaking is presumed to be dominant if it has a market share of 50%. There are also findings of dominance that are below a market share of 50%, for instance, United Brands v Commission,[78] it only possessed a market share of 40% to 45% and still to be found dominant with other factors. The lowest yet market share of a company considered «dominant» in the EU was 39.7%. If a company has a dominant position, then there is a special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the common market however these will all falls away if it is not dominant.[84]

When considering whether an undertaking is dominant, it involves a combination of factors. Each of them cannot be taken separately as if they are, they will not be as determinative as they are when they are combined.[85] Also, in cases where an undertaking has previously been found dominant, it is still necessary to redefine the market and make a whole new analysis of the conditions of competition based on the available evidence at the appropriate time.[86]

Edit

According to the Guidance, there are three more issues that must be examined. They are actual competitors that relates to the market position of the dominant undertaking and its competitors, potential competitors that concerns the expansion and entry and lastly the countervailing buyer power.[85]

- Actual Competitors

Market share may be a valuable source of information regarding the market structure and the market position when it comes to accessing it. The dynamics of the market and the extent to which the goods and services differentiated are relevant in this area.[85]

- Potential Competitors

It concerns with the competition that would come from other undertakings which are not yet operating in the market but will enter it in the future. So, market shares may not be useful in accessing the competitive pressure that is exerted on an undertaking in this area. The potential entry by new firms and expansions by an undertaking must be taken into account,[85] therefore the barriers to entry and barriers to expansion is an important factor here.

- Countervailing buyer power

Competitive constraints may not always come from actual or potential competitors. Sometimes, it may also come from powerful customers who have sufficient bargaining strength which come from its size or its commercial significance for a dominant firm.[85]

Types of abusesEdit

There are three main types of abuses which are exploitative abuse, exclusionary abuse and single market abuse.

- Exploitative abuse

It arises when a monopolist has such significant market power that it can restrict its output while increasing the price above the competitive level without losing customers.[80] This type is less concerned by the Commission than other types.

- Exclusionary abuse

This is most concerned about by the Commissions because it is capable of causing long-term consumer damage and is more likely to prevent the development of competition.[80] An example of it is exclusive dealing agreements.

- Single market abuse

It arises when a dominant undertaking carrying out excess pricing which would not only have an exploitative effect but also prevent parallel imports and limits intra-brand competition.[80]

Examples of abusesEdit

- Limiting supply

- Predatory pricing or undercutting

- Price discrimination

- Refusal to deal and exclusive dealing

- Tying (commerce) and product bundling

Despite wide agreement that the above constitute abusive practices, there is some debate about whether there needs to be a causal connection between the dominant position of a company and its actual abusive conduct. Furthermore, there has been some consideration of what happens when a company merely attempts to abuse its dominant position.

To provide a more specific example, economic and philosophical scholar Adam Smith cites that trade to the East India Company has, for the most part, been subjected to an exclusive company such as that of the English or Dutch. Monopolies such as these are generally established against the nation in which they arose out of. The profound economist goes on to state how there are two types of monopolies. The first type of monopoly is one which tends to always attract to the particular trade where the monopoly was conceived, a greater proportion of the stock of the society than what would go to that trade originally. The second type of monopoly tends to occasionally attract stock towards the particular trade where it was conceived, and sometimes repel it from that trade depending on varying circumstances. Rich countries tended to repel while poorer countries were attracted to this. For example, The Dutch company would dispose of any excess goods not taken to the market in order to preserve their monopoly while the English sold more goods for better prices. Both of these tendencies were extremely destructive as can be seen in Adam Smith’s writings.[87]

Historical monopoliesEdit

OriginEdit

The term «monopoly» first appears in Aristotle’s Politics. Aristotle describes Thales of Miletus’s cornering of the market in olive presses as a monopoly (μονοπώλιον).[88][89] Another early reference to the concept of «monopoly» in a commercial sense appears in tractate Demai of the Mishna (2nd century C.E.), regarding the purchasing of agricultural goods from a dealer who has a monopoly on the produce (chapter 5; 4).[90] The meaning and understanding of the English word ‘monopoly’ has changed over the years.[91]

Monopolies of resourcesEdit

SaltEdit

Vending of common salt (sodium chloride) was historically a natural monopoly. Until recently, a combination of strong sunshine and low humidity or an extension of peat marshes was necessary for producing salt from the sea, the most plentiful source. Changing sea levels periodically caused salt «famines» and communities were forced to depend upon those who controlled the scarce inland mines and salt springs, which were often in hostile areas (e.g. the Sahara desert) requiring well-organised security for transport, storage, and distribution.

The Salt Commission was a legal monopoly in China. Formed in 758, the Commission controlled salt production and sales in order to raise tax revenue for the Tang Dynasty.

The «Gabelle» was a notoriously high tax levied upon salt in the Kingdom of France. The much-hated levy had a role in the beginning of the French Revolution, when strict legal controls specified who was allowed to sell and distribute salt. First instituted in 1286, the Gabelle was not permanently abolished until 1945.[92]

CoalEdit