After the Norman Conquest, in which the Normans invaded England, the English language was strongly influenced by the Anglo-Norman French. This included changes in the vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation of the English language, which eventually led to the evolution from Old English to Middle English. Middle English was the language period spoken and written from the mid-1100s until the mid-1400s.

Let’s begin by taking a look at a brief history of the English language!

Brief History of English

Before delving into the Middle English alphabet and some examples, let’s start by acknowledging the four main periods of the English language, which are as follows:

1. Old English

2. Middle English

3. Early Modern English

4. Modern English

Old English

Old English was the earliest form of English, spoken and written from around 450 — 1150 AD. It was very different from the current English we know and was influenced by Latin and Germanic languages.

Middle English

After the Norman Conquest, the English language was slowly replaced by the Anglo-Norman dialect (a dialect of Old Norman French), this eventually evolved into what is known as Middle English. It was heavily influenced by Anglo-Norman French, particularly words relating to law and religion. Middle English was spoken and written from the mid-1100s until the mid-1400s.

Early Modern English

Early Modern English was used from around 1500 until the 1800s. This was the form of English used by Shakespeare. His work was highly influential during this time and helped shape the English language into what it has become now.

DID YOU KNOW? Shakespeare invented around 1700 words! Many of these are still used in the English language today!

Modern English

Modern English has been spoken since the late 17th century. The use of Modern English was due to «The Great Vowel Shift,» which refers to the mass change of vowel pronunciations in English. This meant that the vowel sounds (particularly long vowels) were pronounced in a different place in the mouth. The shift occurred between the 1400s and 1700s.

Middle English Period

Now we have a basic understanding of the history of English, let’s return to Middle English. The introduction of the Middle English period mostly saw changes in grammar, namely:

-

Word order became more fixed

-

Fewer inflections (word forms)

-

Fewer word endings (suffixes)

-

Using word order instead of word endings to express meaning

Also, vocabulary became more extensive as new words were invented and old words became redundant. Vocabulary continues to change to this day, reflecting the evolution of the English language!

What about the differences between Middle and Modern English?

The main changes were:

-

The standardization of spelling

-

The Great Vowel Shift (changes in the pronunciation of long vowel sounds)

-

Changes in vocabulary (new words invented, old words no longer used)

Middle English Alphabet

The English alphabet we know today contains 26 letters. Old English contained 24, but some letters are no longer used. During the evolution of Middle English, some of these letters were dropped or changed. Let’s take a look at a few of the dropped letters:

Þ / þ — Thorn

Have you ever seen an old sign that said «Ye olde»? Most of the time, the «ye» is mispronounced as «yee.» But in this instance, the «y» actually came from the thorn letter, which made a «the» sound. So «ye» is actually pronounced as «thee.» The «þ» was often written similarly to the letter «y,» which is why we see the spelling «ye olde» instead of «þe olde.» The thorn was later replaced with «th,» which is what we still use today.

Ð / ð — Eth

The eth was pronounced as «th» (such as the /th/ sound in «thorn»). However, it soon got replaced by the thorn due to how similar they sounded in certain accents. Nowadays, we combine the letters «t» and «h» to create a /th/ sound instead of using a single letter.

Ȝ / ȝ — Yogh

The yogh was derived from the Old English letter «g.» There is no Modern English equivalent of the yogh, but it was pronounced similarly to the «ch» in the Scots word «loch.» It was quite a harsh, throaty sound. The yogh was later replaced with «gh.» For example, the word «niȝt» became «night.»

Æ / æ — Ash

The ash looks like a mix of «a» and «e.» It was pronounced the same as the «a» sound in words like «mat» and «bat.» It stopped being used around the 14th century, as it was simply replaced with «a.»

Œ / œ — Ethel

The ethel looks like a mix of «o» and «e.» It was originally pronounced as an «oi» sound (like in the word «foil») but was later pronounced like a mixture of «o» and «e» together. It was later replaced with «e.»

Ƿ / ƿ — Wynn

The letter wynn was used in Old English to represent the «w» sound. In Middle English, this changed to two u’s, so it looked like: uu. This later changed to the «w» we all know today.

Also worth mentioning are the letters «k,» «q,» and «z.»

These letters were rarely used in Old English but came to be more commonly used in Middle English!

Examples of Middle English

Check out an example of The Lord’s Prayer below, written in Middle English. Notice how some words are similar to the Modern English we are familiar with today. One of the main differences is the non-standardized spelling, which makes Middle English more difficult to read!

The Lord’s Prayer — The Wyclif Bible (around 1390)

Oure fadir that art in heuenes,

halewid be thi name;

thi kyngdoom come to;

be thi wille don, in erthe as in heuene.

Yyue to vs this dai oure breed ouer othir

substance,

and foryyue to vs oure dettis, as we foryyuen to

ore dettouris;

and lede vs not in to temptacioun, but delyuere vs fro yuel. Amen.

Modern English translation:

Our Father, who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name;

thy kingdom come;

thy will be done;

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us,

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

Amen.

The standardization of spelling was greatly due to the invention of the printing press, which was a mechanical device used to transfer copies of texts onto paper or cloth. Spelling was standardized for efficiency, as this allowed for the mass production of texts. This saw a major shift between Middle and Modern English; as a result of the gradual standardization of spelling, language became easier to read, write and pronounce.

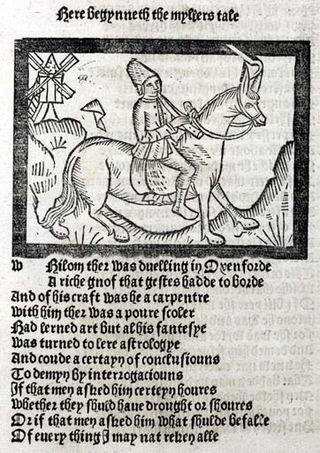

Another example of Middle English comes from English author and poet Geoffrey Chaucer. The Canterbury Tales — a collection of stories by Chaucer — were written in Middle English. Below is an extract:

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

When Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halve cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open yë

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages). —

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

— The Canterbury Tales: General Prologue (1387)

Modern English Translation:

When April with its gentle showers has pierced

the March drought to the root

and bathed every plant in the moisture

which will hasten the flowering;

when Zephyrus with his sweet breath

has stirred the new shoots in every wood and field,

and the young sun

has run its half-course in the Ram,

and small birds sing melodiously,

so touched in their hearts by nature

that they sleep all night with open eyes–

then folks long to go on pilgrimages,

and palmers to visit foreign shores

and distant shrines, known in various lands;

and especially from every shire’s end

of England they travel to Canterbury,

to seek the holy blessed martyr

who helped them when they were sick.

Middle English Words

Here are some examples of Middle English words. As you read through these, think about how many of them are similar to the modern-day words we use.

| Middle English word | Modern English translation |

| Lite | Little |

| Anon | At once |

| Ny | Near |

| Lasse | Less |

| Forthy | Therefore |

| Ech | Each |

| Gan / gonne | Began |

| Morewe | Morrow / morning |

| Swich | Such |

| Ynogh | Enough |

Middle English Pronouns

The pronouns used in Middle English were not all the same as the pronouns used in the English language today. Due to spelling not being standardized, many pronouns in Middle English had more than one spelling and pronunciation. Here is a list of Middle English pronouns and their Modern English translations, starting with singular pronouns:

| Singular Middle English pronouns | Modern English translation |

| Ic / ich / I | I |

| Me / mi | Me |

| Min / minen | My |

| Min / mire / minre | Mine |

| Min one / mi selven | Myself |

| þou / þu / tu / þeou | You (thou) |

| þe | You (thee) |

| þi / ti | Your (thy) |

| þin / þyn | Yours (thine) |

| þeself / þi selven | Yourself (thyself) |

| He | He |

| Him / hine | Him |

| His / hisse / hes | His (as a possessive determiner) |

| His / hisse | His (as a possessive pronoun) |

| Him-seluen | Himself |

| Sche(o) / s(c)ho / ȝho | She |

| Heo / his / hie / hies / hire | Her (as an object) |

| Hio / heo / hire / heore | Her (as a possessive determiner) |

| Heo-seolf | Herself |

| Hit | It (as a subject) |

| Hit / him | It (as an object) |

| His | Its (as a possessive determiner) |

| His | Its (as a possessive pronoun) |

| Hit sulue | Itself |

| Plural Middle English pronouns | Modern English translation |

| We | We |

| Us / ous | Us |

| ure(n) / our(e) / ures / urne | Our |

| Oures | Ours |

| Us self / ous silve | Ourselves |

| ȝe / ye | You (ye) |

| eow / (ȝ)ou / ȝow / gu / you | You |

| eower / (ȝ)ower / gur / (e)our | Your |

| Youres | Yours |

| Ȝou self / ou selve | Yourselves |

| From Old English: heo / heFrom Old Norse: þa / þei / þeo / þo | They |

| From Old English: his / heo(m)From Old Norse: þem / þo | Them |

| From Old English: heore / herFrom Old Norse: þeir | Their |

| From Old Norse: þam-selue | Themselves |

Middle English — Key takeaways

- After the Norman Conquest, the English language was slowly replaced by the Anglo-Norman dialect, which later evolved into Middle English.

- Middle English was heavily influenced by Anglo-Norman French, particularly words relating to law and religion

- Middle English was spoken and written from the mid-1100s until the mid-1400s.

- The spelling of Middle English was not as standardized as it is today, leading to multiple spellings of the same word.

- The letters «k,» «q,» and «z» were rarely used in Old English but came to be used more in Middle English.

| Middle English | |

|---|---|

| Englisch, English, Inglis | |

A page from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales |

|

| Region | England (except for west Cornwall), some localities in the eastern fringe of Wales, south east Scotland and Scottish burghs, to some extent Ireland |

| Era | developed into Early Modern English, Scots, and Yola and Fingallian in Ireland by the 16th century |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Proto-Indo-European

|

|

Writing system |

Latin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | enm |

| ISO 639-3 | enm |

| ISO 639-6 | meng |

| Glottolog | midd1317 |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Middle English (abbreviated to ME[1]) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English period. Scholarly opinion varies, but the Oxford English Dictionary specifies the period when Middle English was spoken as being from 1150 to 1500.[2] This stage of the development of the English language roughly followed the High to the Late Middle Ages.

Middle English saw significant changes to its vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and orthography. Writing conventions during the Middle English period varied widely. Examples of writing from this period that have survived show extensive regional variation. The more standardized Old English language became fragmented, localized, and was, for the most part, being improvised.[2] By the end of the period (about 1470) and aided by the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439, a standard based on the London dialects (Chancery Standard) had become established. This largely formed the basis for Modern English spelling, although pronunciation has changed considerably since that time. Middle English was succeeded in England by Early Modern English, which lasted until about 1650. Scots developed concurrently from a variant of the Northumbrian dialect (prevalent in northern England and spoken in southeast Scotland).

During the Middle English period, many Old English grammatical features either became simplified or disappeared altogether. Noun, adjective and verb inflections were simplified by the reduction (and eventual elimination) of most grammatical case distinctions. Middle English also saw considerable adoption of Norman vocabulary, especially in the areas of politics, law, the arts, and religion, as well as poetic and emotive diction. Conventional English vocabulary remained primarily Germanic in its sources, with Old Norse influences becoming more apparent. Significant changes in pronunciation took place, particularly involving long vowels and diphthongs, which in the later Middle English period began to undergo the Great Vowel Shift.

Little survives of early Middle English literature, due in part to Norman domination and the prestige that came with writing in French rather than English. During the 14th century, a new style of literature emerged with the works of writers including John Wycliffe and Geoffrey Chaucer, whose Canterbury Tales remains the most studied and read work of the period.[4]

History[edit]

Transition from Old English[edit]

The dialects of Middle English c. 1300

The transition from Late Old English to Early Middle English occurred at some point during the 12th century.

The influence of Old Norse aided the development of English from a synthetic language with relatively free word order, to a more analytic or isolating language with a more strict word order.[2][5] Both Old English and Old Norse (as well as the descendants of the latter, Faroese and Icelandic) were synthetic languages with complicated inflections. The eagerness of Vikings in the Danelaw to communicate with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours resulted in the erosion of inflection in both languages.[5][6] Old Norse may have had a more profound impact on Middle and Modern English development than any other language.[7][8][9] Simeon Potter says: «No less far-reaching was the influence of Scandinavian upon the inflexional endings of English in hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms which gradually spread from north to south.»[10]

Viking influence on Old English is most apparent in the more indispensable elements of the language. Pronouns, modals, comparatives, pronominal adverbs (like «hence» and «together»), conjunctions and prepositions show the most marked Danish influence. The best evidence of Scandinavian influence appears in extensive word borrowings, yet no texts exist in either Scandinavia or in Northern England from this period to give certain evidence of an influence on syntax. However, at least one scholarly study of this influence shows that Old English may have been replaced entirely by Norse, by virtue of the change from the Old English syntax to Norse syntax.[11] The effect of Old Norse on Old English was substantive, pervasive, and of a democratic character.[5][6] Like close cousins, Old Norse and Old English resembled each other, and with some words in common, they roughly understood each other;[6] in time the inflections melted away and the analytic pattern emerged.[8][12] It is most «important to recognise that in many words the English and Scandinavian language differed chiefly in their inflectional elements. The body of the word was so nearly the same in the two languages that only the endings would put obstacles in the way of mutual understanding. In the mixed population which existed in the Danelaw these endings must have led to much confusion, tending gradually to become obscured and finally lost.» This blending of peoples and languages resulted in «simplifying English grammar.»[5]

While the influence of Scandinavian languages was strongest in the dialects of the Danelaw region and Scotland, words in the spoken language emerge in the 10th and 11th centuries near the transition from the Old to Middle English. Influence on the written language only appeared at the beginning of the 13th century, likely because of a scarcity of literary texts from an earlier date.[5]

The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 saw the replacement of the top levels of the English-speaking political and ecclesiastical hierarchies by Norman rulers who spoke a dialect of Old French known as Old Norman, which developed in England into Anglo-Norman. The use of Norman as the preferred language of literature and polite discourse fundamentally altered the role of Old English in education and administration, even though many Normans of this period were illiterate and depended on the clergy for written communication and record-keeping. A significant number of words of Norman origin began to appear in the English language alongside native English words of similar meaning, giving rise to such Modern English synonyms as pig/pork, chicken/poultry, calf/veal, cow/beef, sheep/mutton, wood/forest, house/mansion, worthy/valuable, bold/courageous, freedom/liberty, sight/vision, and eat/dine.

The role of Anglo-Norman as the language of government and law can be seen in the abundance of Modern English words for the mechanisms of government that are derived from Anglo-Norman: court, judge, jury, appeal, parliament. There are also many Norman-derived terms relating to the chivalric cultures that arose in the 12th century; an era of feudalism, seigneurialism and crusading.

Words were often taken from Latin, usually through French transmission. This gave rise to various synonyms including kingly (inherited from Old English), royal (from French, which inherited it from Vulgar Latin), and regal (from French, which borrowed it from classical Latin). Later French appropriations were derived from standard, rather than Norman, French. Examples of resultant cognate pairs include the words warden (from Norman), and guardian (from later French; both share a common Germanic ancestor).

The end of Anglo-Saxon rule did not result in immediate changes to the language. The general population would have spoken the same dialects as they had before the Conquest. Once the writing of Old English came to an end, Middle English had no standard language, only dialects that derived from the dialects of the same regions in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Early Middle English[edit]

Early Middle English (1150–1300)[13] has a largely Anglo-Saxon vocabulary (with many Norse borrowings in the northern parts of the country), but a greatly simplified inflectional system. The grammatical relations that were expressed in Old English by the dative and instrumental cases are replaced in Early Middle English with prepositional constructions. The Old English genitive —es survives in the -‘s of the modern English possessive, but most of the other case endings disappeared in the Early Middle English period, including most of the roughly one dozen forms of the definite article («the»). The dual personal pronouns (denoting exactly two) also disappeared from English during this period.

Gradually, the wealthy and the government Anglicised again, although Norman (and subsequently French) remained the dominant language of literature and law until the 14th century, even after the loss of the majority of the continental possessions of the English monarchy. The loss of case endings was part of a general trend from inflections to fixed word order that also occurred in other Germanic languages (though more slowly and to a lesser extent), and therefore it cannot be attributed simply to the influence of French-speaking sections of the population: English did, after all, remain the vernacular. It is also argued[14] that Norse immigrants to England had a great impact on the loss of inflectional endings in Middle English. One argument is that, although Norse- and English-speakers were somewhat comprehensible to each other due to similar morphology, the Norse-speakers’ inability to reproduce the ending sounds of English words influenced Middle English’s loss of inflectional endings.

Important texts for the reconstruction of the evolution of Middle English out of Old English are the Peterborough Chronicle, which continued to be compiled up to 1154; the Ormulum, a biblical commentary probably composed in Lincolnshire in the second half of the 12th century, incorporating a unique phonetic spelling system; and the Ancrene Wisse and the Katherine Group, religious texts written for anchoresses, apparently in the West Midlands in the early 13th century.[15] The language found in the last two works is sometimes called the AB language.

More literary sources of the 12th and 13th centuries include Layamon’s Brut and The Owl and the Nightingale.

Some scholars[16] have defined «Early Middle English» as encompassing English texts up to 1350. This longer time frame would extend the corpus to include many Middle English Romances (especially those of the Auchinleck manuscript c. 1330).

14th century[edit]

From around the early 14th century, there was significant migration into London, particularly from the counties of the East Midlands, and a new prestige London dialect began to develop, based chiefly on the speech of the East Midlands, but also influenced by that of other regions.[17] The writing of this period, however, continues to reflect a variety of regional forms of English. The Ayenbite of Inwyt, a translation of a French confessional prose work, completed in 1340, is written in a Kentish dialect. The best known writer of Middle English, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote in the second half of the 14th century in the emerging London dialect, although he also portrays some of his characters as speaking in northern dialects, as in the «Reeve’s Tale».

In the English-speaking areas of lowland Scotland, an independent standard was developing, based on the Northumbrian dialect. This would develop into what came to be known as the Scots language.

A large number of terms for abstract concepts were adopted directly from scholastic philosophical Latin (rather than via French). Examples are «absolute», «act», «demonstration», «probable».[18]

Late Middle English[edit]

The Chancery Standard of written English emerged c. 1430 in official documents that, since the Norman Conquest, had normally been written in French.[17] Like Chaucer’s work, this new standard was based on the East-Midlands-influenced speech of London. Clerks using this standard were usually familiar with French and Latin, influencing the forms they chose. The Chancery Standard, which was adopted slowly, was used in England by bureaucrats for most official purposes, excluding those of the Church and legalities, which used Latin and Law French (and some Latin), respectively.

The Chancery Standard’s influence on later forms of written English is disputed, but it did undoubtedly provide the core around which Early Modern English formed.[citation needed] Early Modern English emerged with the help of William Caxton’s printing press, developed during the 1470s. The press stabilized English through a push towards standardization, led by Chancery Standard enthusiast and writer Richard Pynson.[19] Early Modern English began in the 1540s after the printing and wide distribution of the English Bible and Prayer Book, which made the new standard of English publicly recognizable, and lasted until about 1650.

Phonology[edit]

The main changes between the Old English sound system and that of Middle English include:

- Emergence of the voiced fricatives /v/, /ð/, /z/ as separate phonemes, rather than mere allophones of the corresponding voiceless fricatives.

- Reduction of the Old English diphthongs to monophthongs, and the emergence of new diphthongs due to vowel breaking in certain positions, change of Old English post-vocalic /j/, /w/ (sometimes resulting from the [ɣ] allophone of /ɡ/) to offglides, and borrowing from French.

- Merging of Old English /æ/ and /ɑ/ into a single vowel /a/.

- Raising of the long vowel /æː/ to /ɛː/.

- Rounding of /ɑː/ to /ɔː/ in the southern dialects.

- Unrounding of the front rounded vowels in most dialects.

- Lengthening of vowels in open syllables (and in certain other positions). The resultant long vowels (and other pre-existing long vowels) subsequently underwent changes of quality in the Great Vowel Shift, which began during the later Middle English period.

- Loss of gemination (double consonants came to be pronounced as single ones).

- Loss of weak final vowels (schwa, written ⟨e⟩). By Chaucer’s time this vowel was silent in normal speech, although it was normally pronounced in verse as the meter required (much as occurs in modern French). Also, non-final unstressed ⟨e⟩ was dropped when adjacent to only a single consonant on either side if there was another short ⟨e⟩ in an adjoining syllable. Thus, every began to be pronounced as evry, and palmeres as palmers.

The combination of the last three processes listed above led to the spelling conventions associated with silent ⟨e⟩ and doubled consonants (see under Orthography, below).

Morphology[edit]

Nouns[edit]

Middle English retains only two distinct noun-ending patterns from the more complex system of inflection in Old English:

| Nouns | Strong nouns | Weak nouns | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | -(e) | —es | —e | —en |

| Accusative | —en | |||

| Genitive | —es[20] | —e(ne)[21] | ||

| Dative | —e | —e(s) |

Nouns of the weak declension are primarily inherited from Old English n-stem nouns, but also from ō-stem, wō-stem and u-stem nouns,[citation needed] which did not inflect in the same way as n-stem nouns in Old English, but joined the weak declension in Middle English. Nouns of the strong declension are inherited from the other Old English noun stem classes.

Some nouns of the strong type have an -e in the nominative/accusative singular, like the weak declension, but otherwise strong endings. Often these are the same nouns that had an -e in the nominative/accusative singular of Old English (they, in turn, were inherited from Proto-Germanic ja-stem and i-stem nouns).

The distinct dative case was lost in early Middle English. The genitive survived, however, but by the end of the Middle English period, only the strong -‘s ending (variously spelt) was in use.[22] Some formerly feminine nouns, as well as some weak nouns, continued to make their genitive forms with -e or no ending (e.g. fole hoves, horses’ hooves), and nouns of relationship ending in -er frequently have no genitive ending (e.g. fader bone, «father’s bane»).[23]

The strong -(e)s plural form has survived into Modern English. The weak -(e)n form is now rare and used only in oxen and, as part of a double plural, in children and brethren. Some dialects still have forms such as eyen (for eyes), shoon (for shoes), hosen (for hose(s)), kine (for cows), and been (for bees).

Grammatical gender survived to a limited extent in early Middle English,[23] before being replaced by natural gender in the course of the Middle English period. Grammatical gender was indicated by agreement of articles and pronouns, i.e. þo ule («the-feminine owl») or using the pronoun he to refer to masculine nouns such as helm («helmet»), or phrases such as scaft stærcne (strong shaft) with the masculine accusative adjective ending -ne.[24]

Adjectives[edit]

Single syllable adjectives add -e when modifying a noun in the plural and when used after the definite article (þe), after a demonstrative (þis, þat), after a possessive pronoun (e.g. hir, our), or with a name or in a form of address. This derives from the Old English «weak» declension of adjectives.[25] This inflexion continued to be used in writing even after final -e had ceased to be pronounced.[26] In earlier texts, multi-syllable adjectives also receive a final -e in these situations, but this occurs less regularly in later Middle English texts. Otherwise adjectives have no ending, and adjectives already ending in -e etymologically receive no ending as well.[26]

Earlier texts sometimes inflect adjectives for case as well. Layamon’s Brut inflects adjectives for the masculine accusative, genitive, and dative, the feminine dative, and the plural genitive.[27] The Owl and the Nightingale adds a final -e to all adjectives not in the nominative, here only inflecting adjectives in the weak declension (as described above).[28]

Comparatives and superlatives are usually formed by adding -er and -est. Adjectives with long vowels sometimes shorten these vowels in the comparative and superlative, e.g. greet (great) gretter (greater).[28] Adjectives ending in -ly or -lich form comparatives either with -lier, -liest or -loker, -lokest.[28] A few adjectives also display Germanic umlaut in their comparatives and superlatives, such as long, lenger.[28] Other irregular forms are mostly the same as in modern English.[28]

Pronouns[edit]

Middle English personal pronouns were mostly developed from those of Old English, with the exception of the third-person plural, a borrowing from Old Norse (the original Old English form clashed with the third person singular and was eventually dropped). Also, the nominative form of the feminine third-person singular was replaced by a form of the demonstrative that developed into sche (modern she), but the alternative heyr remained in some areas for a long time.

As with nouns, there was some inflectional simplification (the distinct Old English dual forms were lost), but pronouns, unlike nouns, retained distinct nominative and accusative forms. Third-person pronouns also retained a distinction between accusative and dative forms, but that was gradually lost: the masculine hine was replaced by him south of the Thames by the early 14th century, and the neuter dative him was ousted by it in most dialects by the 15th.[29]

The following table shows some of the various Middle English pronouns. Many other variations are noted in Middle English sources because of differences in spellings and pronunciations at different times and in different dialects.[30]

| Personal pronouns | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | ||||||

| Nominative | ic, ich, I | we | þeou, þ(o)u, tu | ye | he | hit | s(c)he(o) | he(o)/ þei |

| Accusative | mi | (o)us | þe | eow, eou, yow, gu, you | hine | heo, his, hi(r)e | his/ þem | |

| Dative | him | him | heo(m), þo/ þem | |||||

| Possessive | min(en) | (o)ure, ures, ure(n) | þi, ti | eower, yower, gur, eour | his, hes | his | heo(re), hio, hire | he(o)re/ þeir |

| Genitive | min, mire, minre | oures | þin, þyn | youres | his | |||

| Reflexive | min one, mi selven | us self, ous-silve | þeself, þi selven | you-self/ you-selve | him-selven | hit-sulve | heo-seolf | þam-selve/ þem-selve |

Verbs[edit]

As a general rule, the indicative first person singular of verbs in the present tense ends in -e (ich here, ‘I hear’), the second person in -(e)st (þou spekest, ‘thou speakest’), and the third person in -eþ (he comeþ, ‘he cometh/he comes’). (þ (the letter ‘thorn’) is pronounced like the unvoiced th in «think», but, under certain circumstances, it may be like the voiced th in «that»). The following table illustrates a typical conjugation pattern:[31][32]

| Verbs inflection | Infinitive | Present | Past | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participle | Singular | Plural | Participle | Singular | Plural | ||||||

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | ||||||

| Regular verbs | |||||||||||

| Strong | -en | -ende, -ynge | -e | -est | -eþ (-es) | -en (-es, -eþ) | i- -en | — | -e (-est) | — | -en |

| Weak | -ed | -ede | -edest | -ede | -eden | ||||||

| Irregular verbs | |||||||||||

| Been «be» | been | beende, beynge | am | art | is | aren | ibeen | was | wast | was | weren |

| be | bist | biþ | beth, been | were | |||||||

| Cunnen «can» | cunnen | cunnende, cunnynge | can | canst | can | cunnen | cunned, coud | coude, couthe | coudest, couthest | coude, couthe | couden, couthen |

| Don «do» | don | doende, doynge | do | dost | doþ | doþ, don | idon | didde | didst | didde | didden |

| Douen «be good for» | douen | douende, douynge | deigh | deight | deigh | douen | idought | dought | doughtest | dought | doughten |

| Durren «dare» | durren | durrende, durrynge | dar | darst | dar | durren | durst, dirst | durst | durstest | durst | dursten |

| Gon «go» | gon | goende, goynge | go | gost | goþ | goþ, gon | igon(gen) | wend, yede, yode | wendest, yedest, yodest | wende, yede, yode | wenden, yeden, yoden |

| Haven «have» | haven | havende, havynge | have | hast | haþ | haven | ihad | hadde | haddest | hadde | hadden |

| Moten «must» | — | — | mot | must | mot | moten | — | muste | mustest | muste | musten |

| Mowen «may» | mowen | mowende, mowynge | may | myghst | may | mowen | imought | mighte | mightest | mighte | mighten |

| Owen «owe, ought» | owen | owende, owynge | owe | owest | owe | owen | iowen | owed | ought | owed | ought |

| Schulen «should» | — | — | schal | schalt | schal | schulen | — | scholde | scholdest | scholde | scholde |

| Þurven «need» | — | — | þarf | þarst | þarf | þurven | — | þurft | þurst | þurft | þurften |

| Willen «want» | willen | willende, willynge | will | wilt | will | wollen | — | wolde | woldest | wolde | wolden |

| Witen «know» | witen | witende, witynge | woot | woost | woot | witen | iwiten | wiste | wistest | wiste | wisten |

Plural forms vary strongly by dialect, with Southern dialects preserving the Old English -eþ, Midland dialects showing -en from about 1200 and Northern forms using -es in the third person singular as well as the plural.[33]

The past tense of weak verbs is formed by adding an -ed(e), -d(e) or -t(e) ending. The past-tense forms, without their personal endings, also serve as past participles with past-participle prefixes derived from Old English: i-, y- and sometimes bi-.

Strong verbs, by contrast, form their past tense by changing their stem vowel (binden becomes bound, a process called apophony), as in Modern English.

Orthography[edit]

With the discontinuation of the Late West Saxon standard used for the writing of Old English in the period prior to the Norman Conquest, Middle English came to be written in a wide variety of scribal forms, reflecting different regional dialects and orthographic conventions. Later in the Middle English period, however, and particularly with the development of the Chancery Standard in the 15th century, orthography became relatively standardised in a form based on the East Midlands-influenced speech of London. Spelling at the time was mostly quite regular (there was a fairly consistent correspondence between letters and sounds). The irregularity of present-day English orthography is largely due to pronunciation changes that have taken place over the Early Modern English and Modern English eras.

Middle English generally did not have silent letters. For example, knight was pronounced [ˈkniçt] (with both the ⟨k⟩ and the ⟨gh⟩ pronounced, the latter sounding as the ⟨ch⟩ in German Knecht). The major exception was the silent ⟨e⟩ – originally pronounced, but lost in normal speech by Chaucer’s time. This letter, however, came to indicate a lengthened – and later also modified – pronunciation of a preceding vowel. For example, in name, originally pronounced as two syllables, the /a/ in the first syllable (originally an open syllable) lengthened, the final weak vowel was later dropped, and the remaining long vowel was modified in the Great Vowel Shift (for these sound changes, see under Phonology, above). The final ⟨e⟩, now silent, thus became the indicator of the longer and changed pronunciation of ⟨a⟩. In fact vowels could have this lengthened and modified pronunciation in various positions, particularly before a single consonant letter and another vowel, or before certain pairs of consonants.

A related convention involved the doubling of consonant letters to show that the preceding vowel was not to be lengthened. In some cases the double consonant represented a sound that was (or had previously been) geminated, i.e. had genuinely been «doubled» (and would thus have regularly blocked the lengthening of the preceding vowel). In other cases, by analogy, the consonant was written double merely to indicate the lack of lengthening.

Alphabet[edit]

The basic Old English Latin alphabet had consisted of 20 standard letters plus four additional letters: ash ⟨æ⟩, eth ⟨ð⟩, thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨ƿ⟩. There was not yet a distinct j, v or w, and Old English scribes did not generally use k, q or z.

Ash was no longer required in Middle English, as the Old English vowel /æ/ that it represented had merged into /a/. The symbol nonetheless came to be used as a ligature for the digraph ⟨ae⟩ in many words of Greek or Latin origin, as did ⟨œ⟩ for ⟨oe⟩.

Eth and thorn both represented /θ/ or its allophone /ð/ in Old English. Eth fell out of use during the 13th century and was replaced by thorn. Thorn mostly fell out of use during the 14th century, and was replaced by ⟨th⟩. Anachronistic usage of the scribal abbreviation (þe, i.e. «the») has led to the modern mispronunciation of thorn as ⟨y⟩ in this context; see ye olde.[34]

Wynn, which represented the phoneme /w/, was replaced by ⟨w⟩ during the 13th century. Due to its similarity to the letter ⟨p⟩, it is mostly represented by ⟨w⟩ in modern editions of Old and Middle English texts even when the manuscript has wynn.

Under Norman influence, the continental Carolingian minuscule replaced the insular script that had been used for Old English. However, because of the significant difference in appearance between the old insular g and the Carolingian g (modern g), the former continued in use as a separate letter, known as yogh, written ⟨ȝ⟩. This was adopted for use to represent a variety of sounds: [ɣ], [j], [dʒ], [x], [ç], while the Carolingian g was normally used for [g]. Instances of yogh were eventually replaced by ⟨j⟩ or ⟨y⟩, and by ⟨gh⟩ in words like night and laugh. In Middle Scots yogh became indistinguishable from cursive z, and printers tended to use ⟨z⟩ when yogh was not available in their fonts; this led to new spellings (often giving rise to new pronunciations), as in McKenzie, where the ⟨z⟩ replaced a yogh which had the pronunciation /j/.

Under continental influence, the letters ⟨k⟩, ⟨q⟩ and ⟨z⟩, which had not normally been used by Old English scribes, came to be commonly used in the writing of Middle English. Also the newer Latin letter ⟨w⟩ was introduced (replacing wynn). The distinct letter forms ⟨v⟩ and ⟨u⟩ came into use, but were still used interchangeably; the same applies to ⟨j⟩ and ⟨i⟩.[35] (For example, spellings such as wijf and paradijs for wife and paradise can be found in Middle English.)

The consonantal ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ was sometimes used to transliterate the Hebrew letter yodh, representing the palatal approximant sound /j/ (and transliterated in Greek by iota and in Latin by ⟨i⟩); words like Jerusalem, Joseph, etc. would have originally followed the Latin pronunciation beginning with /j/, that is, the sound of ⟨y⟩ in yes. In some words, however, notably from Old French, ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ was used for the affricate consonant /dʒ/, as in joie (modern «joy»), used in Wycliffe’s Bible.[36][37] This was similar to the geminate sound [ddʒ], which had been represented as ⟨cg⟩ in Old English. By the time of Modern English, the sound came to be written as ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ at the start of words (like joy), and usually as ⟨dg⟩ elsewhere (as in bridge). It could also be written, mainly in French loanwords, as ⟨g⟩, with the adoption of the soft G convention (age, page, etc.)

Other symbols[edit]

Many scribal abbreviations were also used. It was common for the Lollards to abbreviate the name of Jesus (as in Latin manuscripts) to ihc. The letters ⟨n⟩ and ⟨m⟩ were often omitted and indicated by a macron above an adjacent letter, so for example in could be written as ī. A thorn with a superscript ⟨t⟩ or ⟨e⟩ could be used for that and the; the thorn here resembled a ⟨Y⟩, giving rise to the ye of «Ye Olde». Various forms of the ampersand replaced the word and.

Numbers were still always written using Roman numerals, except for some rare occurrences of Arabic numerals during the 15th century.

Letter-to-sound correspondences[edit]

Although Middle English spelling was never fully standardised, the following table shows the pronunciations most usually represented by particular letters and digraphs towards the end of the Middle English period, using the notation given in the article on Middle English phonology.[38] As explained above, single vowel letters had alternative pronunciations depending on whether they were in a position where their sounds had been subject to lengthening. Long vowel pronunciations were in flux due to the beginnings of the Great Vowel Shift.

| Symbol | Description and notes |

|---|---|

| a | /a/, or in lengthened positions /aː/, becoming [æː] by about 1500. Sometimes /au/ before ⟨l⟩ or nasals (see Late Middle English diphthongs). |

| ai, ay | /ai/ (alternatively denoted by /ɛi/; see vein–vain merger). |

| au, aw | /au/ |

| b | /b/, but in later Middle English became silent in words ending -mb (while some words that never had a /b/ sound came to be spelt -mb by analogy; see reduction of /mb/). |

| c | /k/, but /s/ (earlier /ts/) before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨y⟩ (see C and hard and soft C for details). |

| ch | /tʃ/ |

| ck | /k/, replaced earlier ⟨kk⟩ as the doubled form of ⟨k⟩ (for the phenomenon of doubling, see above). |

| d | /d/ |

| e | /e/, or in lengthened positions /eː/ or sometimes /ɛː/ (see ee). For silent ⟨e⟩, see above. |

| ea | Rare, for /ɛː/ (see ee). |

| ee | /eː/, becoming [iː] by about 1500; or /ɛː/, becoming [eː] by about 1500. In Early Modern English the latter vowel came to be commonly written ⟨ea⟩. The two vowels later merged. |

| ei, ey | Sometimes the same as ⟨ai⟩; sometimes /ɛː/ or /eː/ (see also fleece merger). |

| ew | Either /ɛu/ or /iu/ (see Late Middle English diphthongs; these later merged). |

| f | /f/ |

| g | /ɡ/, or /dʒ/ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨y⟩ (see ⟨g⟩ for details). The ⟨g⟩ in initial gn- was still pronounced. |

| gh | [ç] or [x], post-vowel allophones of /h/ (this was formerly one of the uses of yogh). The ⟨gh⟩ is often retained in Chancery spellings even though the sound was starting to be lost. |

| h | /h/ (except for the allophones for which ⟨gh⟩ was used). Also used in several digraphs (⟨ch⟩, ⟨th⟩, etc.). In some French loanwords, such as horrible, the ⟨h⟩ was silent. |

| i, j | As a vowel, /i/, or in lengthened positions /iː/, which had started to be diphthongised by about 1500. As a consonant, /dʒ/ ( (corresponding to modern ⟨j⟩); see above). |

| ie | Used sometimes for /ɛː/ (see ee). |

| k | /k/, used particularly in positions where ⟨c⟩ would be softened. Also used in ⟨kn⟩ at the start of words; here both consonants were still pronounced. |

| l | /l/ |

| m | /m/ |

| n | /n/, including its allophone [ŋ] (before /k/, /g/). |

| o | /o/, or in lengthened positions /ɔː/ or sometimes /oː/ (see oo). Sometimes /u/, as in sone (modern son); the ⟨o⟩ spelling was often used rather than ⟨u⟩ when adjacent to i, m, n, v, w for legibility, i.e. to avoid a succession of vertical strokes.[39] |

| oa | Rare, for /ɔː/ (became commonly used in Early Modern English). |

| oi, oy | /ɔi/ or /ui/ (see Late Middle English diphthongs; these later merged). |

| oo | /oː/, becoming [uː] by about 1500; or /ɔː/. |

| ou, ow | Either /uː/, which had started to be diphthongised by about 1500, or /ɔu/. |

| p | /p/ |

| qu | /kw/ |

| r | /r/ |

| s | /s/, sometimes /z/ (formerly [z] was an allophone of /s/). Also appeared as ſ (long s). |

| sch, sh | /ʃ/ |

| t | /t/ |

| th | /θ/ or /ð/ (which had previously been allophones of a single phoneme), replacing earlier eth and thorn, although thorn was still sometimes used. |

| u, v | Used interchangeably. As a consonant, /v/. As a vowel, /u/, or /iu/ in «lengthened» positions (although it had generally not gone through the same lengthening process as other vowels – see history of /iu/). |

| w | /w/ (replaced Old English wynn). |

| wh | /hw/ (see English ⟨wh⟩). |

| x | /ks/ |

| y | As a consonant, /j/ (earlier this was one of the uses of yogh). Sometimes also /g/. As a vowel, the same as ⟨i⟩, where ⟨y⟩ is often preferred beside letters with downstrokes. |

| z | /z/ (in Scotland sometimes used as a substitute for yogh; see above). |

Sample texts[edit]

Most of the following Modern English translations are poetic sense-for-sense translations, not word-for-word translations.

Ormulum, 12th century[edit]

This passage explains the background to the Nativity (3494–501):[40]

| Forrþrihht anan se time commþatt ure Drihhtin wolldeben borenn i þiss middellærdforr all mannkinne nedehe chæs himm sone kinnessmennall swillke summ he wolldeand whær he wollde borenn benhe chæs all att hiss wille. | Forthwith when the time camethat our Lord wantedbe born in this earthfor all mankind sake,He chose kinsmen for Himself,all just as he wanted,and where He would be bornHe chose exactly as He wished. |

Epitaph of John the smyth, died 1371[edit]

An epitaph from a monumental brass in an Oxfordshire parish church:[41][42]

| Original text | Word-for-word translation into Modern English | Translation by Patricia Utechin[42] |

|---|---|---|

| man com & se how schal alle dede li: wen þow comes bad & barenoth hab ven ve awaẏ fare: All ẏs wermēs þt ve for care:—bot þt ve do for godẏs luf ve haue nothyng yare:hundyr þis graue lẏs John þe smẏth god yif his soule heuen grit | Man, come and see how shall all dead lie: when thou comes bad and barenaught have we away fare: all is worms that we for care:—but that we do for God’s love, we have nothing ready:under this grave lies John the smith, God give his soul heaven great | Man, come and see how all dead men shall lie: when that comes bad and bare,we have nothing when we away fare: all that we care for is worms:—except for that which we do for God’s sake, we have nothing ready:under this grave lies John the smith, God give his soul heavenly peace |

Wycliffe’s Bible, 1384[edit]

From the Wycliffe’s Bible, (1384):

| First version | Second version | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesu made iorney by citees and castelis, prechinge and euangelysinge þe rewme of God, 2and twelue wiþ him; and summe wymmen þat weren heelid of wickide spiritis and syknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Mawdeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis wenten 3 out, and Jone, þe wyf of Chuse, procuratour of Eroude, and Susanne, and manye oþere, whiche mynystriden to him of her riches. | 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesus made iourney bi citees and castels, prechynge and euangelisynge þe rewme of 2God, and twelue wiþ hym; and sum wymmen þat weren heelid of wickid spiritis and sijknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Maudeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis 3wenten out, and Joone, þe wijf of Chuse, þe procuratoure of Eroude, and Susanne, and many oþir, þat mynystriden to hym of her ritchesse. | 1And it happened afterwards, that Jesus made a journey through cities and settlements, preaching and evangelising the realm of 2God: and with him The Twelve; and some women that were healed of wicked spirits and sicknesses; Mary who is called Magdalen, from whom 3seven devils went out; and Joanna the wife of Chuza, the steward of Herod; and Susanna, and many others, who administered to Him out of their own means. |

Chaucer, 1390s[edit]

The following is the very beginning of the General Prologue from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. The text was written in a dialect associated with London and spellings associated with the then-emergent Chancery Standard.

| Original in Middle English | Word-for-word translation into Modern English[43] | Translation into Modern U.K. English prose[44] |

|---|---|---|

| Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote | When [that] April with his showers sweet | When April with its sweet showers |

| The droȝte of March hath perced to the roote | The drought of March has pierced to the root | has drenched March’s drought to the roots, |

| And bathed every veyne in swich licour, | And bathed every vein in such liquor, | filling every capillary with nourishing sap |

| Of which vertu engendred is the flour; | From which goodness is engendered the flower; | prompting the flowers to grow, |

| Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth | When Zephyrus even with his sweet breath | and when Zephyrus with his sweet breath |

| Inspired hath in every holt and heeth | Inspired has in every holt and heath | has coaxed in every wood and dale, to sprout |

| The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne | The tender crops; and the young sun | the tender plants, as the springtime sun |

| Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne, | Has in the Ram his half-course run, | passes halfway through the sign of Aries, |

| And smale foweles maken melodye, | And small birds make melodies, | and small birds that chirp melodies, |

| That slepen al the nyght with open ye | That sleep all night with open eyes | sleep all night with half-open eyes |

| (So priketh hem Nature in hir corages); | (So Nature prompts them in their boldness); | their spirits thus aroused by Nature; |

| Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages | Then folk long to go on pilgrimages. | it is at these times that people desire to go on pilgrimages |

| And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes | And pilgrims (palmers) [for] to seek new strands | and pilgrims (palmers) seek new shores |

| To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; | To far-off shrines (hallows), respected in sundry lands; | and distant shrines venerated in other places. |

| And specially from every shires ende | And specially from every shire’s end | Particularly from every county |

| Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, | Of England, to Canterbury they wend, | of England, they go to Canterbury, |

| The hooly blisful martir for to seke | The holy blissful martyr [for] to seek, | in order to visit the holy blessed martyr, |

| That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke. | That has helped them, when [that] they were sick. | who has helped them when they were unwell. |

Gower, 1390[edit]

The following is the beginning of the Prologue from Confessio Amantis by John Gower.

| Original in Middle English | Near word-for-word translation into Modern English: | Translation into Modern English: (by Richard Brodie)[45] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Translation in Modern English: (by J. Dow)

Of those who wrote before we were born, books survive,

So we are taught what was written by them when they were alive.

So it’s good that we, in our times here on earth, write of new matters –

Following the example of our forefathers –

So that, in such a way, we may leave our knowledge to the world after we are dead and gone.

But it’s said, and it is true, that if one only reads of wisdom all day long

It often dulls one’s brains. So, if it’s alright with you,

I’ll take the middle route and write a book between the two –

Somewhat of amusement, and somewhat of fact.In that way, somebody might, more or less, like that.

See also[edit]

- Medulla Grammatice (collection of glossaries)

- Middle English creole hypothesis

- Middle English Dictionary

- Middle English literature

- A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English

References[edit]

- ^ Simon Horobin, Introduction to Middle English, Edinburgh 2016, s. 1.1.

- ^ a b c Durkin, Philip (2012-08-16). «Middle English–an overview». Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on Jun 17, 2018. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ^ Carlson, David. (2004). «The Chronology of Lydgate’s Chaucer References». The Chaucer Review. 38 (3): 246–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.7778. doi:10.1353/cr.2004.0003.

- ^ The name «tales of Canterbury» appears within the surviving texts of Chaucer’s work.[3]

- ^ a b c d e Baugh, Albert (1951). A History of the English Language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 110–130 (Danelaw), 131–132 (Normans).

- ^ a b c Jespersen, Otto (1919). Growth and Structure of the English Language. Leipzig, Germany: B. G. Teubner. pp. 58–82.

- ^ Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32. ISBN 9780521401791.

- ^ a b McCrum, Robert (1987). The Story of English. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 70–71.

- ^ BBC (27 December 2014). «[BBC World News] BBC Documentary English Birth of a Language — 35:00 to 37:20». YouTube. BBC. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Potter, Simeon (1950). Our Language. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin. pp. 33.

- ^ Faarlund, Jan Terje, and Joseph E. Emonds. «English as North Germanic». Language Dynamics and Change 6.1 (2016): 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1163/22105832-00601002 Web.

- ^ Lohmeier, Charlene (28 October 2012). «121028 Charlene Lohmeier «Evolution of the English Language» — 23:40 — 25:00; 30:20 — 30:45; 45:00 — 46:00″. YouTube. Dutch Lichliter. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Fuster-Márquez, Miguel; Calvo García de Leonardo, Juan José (2011). A Practical Introduction to the History of English. [València]: Universitat de València. p. 21. ISBN 9788437083216. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ McWhorter, Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue, 2008, pp. 89–136.

- ^ Burchfield, Robert W. (1987). «Ormulum». In Strayer, Joseph R. (ed.). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Vol. 9. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-684-18275-9., p. 280

- ^ «Making Early Middle English: About the Conference». hcmc.uvic.ca.

- ^ a b Wright, L. (2012). «About the evolution of Standard English». Studies in English Language and Literature. Routledge. p. 99ff. ISBN 978-1138006935.

- ^ Franklin, James (1983). «Mental furniture from the philosophers» (PDF). Et Cetera. 40: 177–191. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ cf. ‘Sawles Warde’ (The protection of the soul)

- ^ cf. ‘Sawles Warde’ (The protection of the soul)

- ‘^ cf. ‘Ancrene Wisse’ (The Anchoresses Guide)

- ^ Fischer, O., van Kemenade, A., Koopman, W., van der Wurff, W., The Syntax of Early English, CUP 2000, p. 72.

- ^ a b Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, p. 23

- ^ Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, p. 38

- ^ Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, p. 28

- ^ Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b c d e Burrow & Turville-Petre 2005, p. 29

- ^ Fulk, R.D., An Introduction to Middle English, Broadview Press, 2012, p. 65.

- ^ See Stratmann, Francis Henry (1891). A Middle-English dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. OL 7114246M. and Mayhew, AL; Skeat, Walter W (1888). A Concise Dictionary of Middle English from A.D. 1150 to 1580. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Booth, David (1831). The Principles of English Composition. Cochrane and Pickersgill.

- ^ Horobin, Simon (9 September 2016). Introduction to Middle English. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474408462.

- ^ Ward, AW; Waller, AR (1907–21). «The Cambridge History of English and American Literature». Bartleby. Retrieved Oct 4, 2011.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, ye[2] retrieved February 1, 2009

- ^ Salmon, V., (in) Lass, R. (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, Vol. III, CUP 2000, p. 39.

- ^ «J», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989)

- ^ «J» and «jay», Merriam-Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993)

- ^ For certain details, see «Chancery Standard spelling» in Upward, C., Davidson, G., The History of English Spelling, Wiley 2011.

- ^ Algeo, J., Butcher, C., The Origins and Development of the English Language, Cengage Learning 2013, p. 128.

- ^ Holt, Robert, ed. (1878). The Ormulum: with the notes and glossary of Dr R. M. White. Two vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Internet Archive: Volume 1; Volume 2.

- ^ Bertram, Jerome (2003). «Medieval Inscriptions in Oxfordshire» (PDF). Oxoniensia. LXVVIII: 30. ISSN 0308-5562.

- ^ a b Utechin, Patricia (1990) [1980]. Epitaphs from Oxfordshire (2nd ed.). Oxford: Robert Dugdale. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-946976-04-1.

- ^ This Wikipedia translation closely mirrors the translation found here: Canterbury Tales (selected). Translated by Vincent Foster Hopper (revised ed.). Barron’s Educational Series. 1970. p. 2. ISBN 9780812000399.

when april, with his.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Sweet, Henry (d. 1912) (2005). First Middle English Primer (updated). Evolution Publishing: Bristol, Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-1-889758-70-1.

- ^ Brodie, Richard (2005). «John Gower’s ‘Confessio Amantis’ Modern English Version». Prologue. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- Brunner, Karl (1962) Abriss der mittelenglischen Grammatik; 5. Auflage. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer (1st ed. Halle (Saale): M. Niemeyer, 1938)

- Brunner, Karl (1963) An Outline of Middle English Grammar; translated by Grahame Johnston. Oxford: Blackwell

- Burrow, J. A.; Turville-Petre, Thorlac (2005). A Book of Middle English (3 ed.). Blackwell.

- Mustanoja, Tauno (1960) «A Middle English Syntax. 1. Parts of Speech». Helsinki : Société néophilologique.

External links[edit]

- A. L. Mayhew and Walter William Skeat. A Concise Dictionary of Middle English from A.D. 1150 to 1580

- Middle English Glossary (archived 22 February 2012)

- Oliver Farrar Emerson, ed. (1915). A Middle English Reader. Internet Archive. Macmillan. With grammatical introduction, notes, and glossary.

- Middle English encyclopedia on Miraheze

2.1.

General characteristics

An

analysis of the vocabulary in the Middle English period shows great

instability and constant and rapid change. Many words became

obsolete, and if preserved, then only in some dialects: many more

appeared in the rapidly developing language to reflect the

ever-changing life of the speakers and under the influence of

contacts with other nations.

2.2.

Means of enriching vocabulary in Middle English

2.2.1.

Internal means of enriching vocabulary

Though

the majority of Old English suffixes are still preserved in Middle

English, they becoming less productive, and words formed by means of

word-derivation in Old English can be treated as such only

etymologically.

Words

by means of word-composition in Old English, in Middle English are

often understood as derived words.

2.2.2.

External means of enriching vocabulary

The

principal means of enriching vocabulary in Middle English are not

internal, but external borrowings. Two languages in succession

enriched the vocabulary English of that period – the Scandinavian

language and the French language, the nature of the borrowings and

their amount reflecting the conditions of the contacts between the

English and these languages.

-

Scandinavian

borrowings

The

Scandinavian invasion and the subsequent settlement of the

Scandinavians on the territory of England, the constant contacts and

intermixture of the English and Scandinavians brought about many

changes in different spheres of the English language: word-stock,

grammar and phonetics. The relative ease of the mutual penetration of

the languages was conditioned by the circumstances of the

Anglo-Scandinavians contacts.

Due

to contacts between the Scandinavians and the English people many

words were borrowed from the Scandinavian language, for example:

Nouns:

law, fellow, sky, skirt, skill, egg, anger, awe, bloom, knife, root,

bull, cake, husband, leg, wing, guest, loan, race

Adjectives:

big,

weak, wrong, ugly, twin

Verbs:

call,

cast, take, happen, scare, hail, want, bask, gape, kindle

Pronouns:

they, them, their

The

conditions and the consequences of various borrowings were different.

-

Sometimes

the English language borrowed a word which it had no synonym. These

words were simply added top the vocabulary. Examples: law, fellow -

The

English synonym was ousted by the borrowing. Scandinavian Taken

(to

take)

and callen

(to

call)

ousted the English synonyms niman

and

clypian,

respectively. -

Both

the words, the English and the corresponding Scandinavian, are

preserved, but they became different in meaning. Compare Modern

English native words and Scandinavian borrowings:

Native

Scandinavian borrowing

Heaven

sky

Starve

die

-

Sometimes

a borrowed word and an English word are etymologically doublets, as

words originating from the same source in Common Germanic.

Native

Scandinavian borrowing

shirt

skirt

shatter

scatter

raise

rear

-

Sometimes

an English word and its Scandinavian doublet were the same in

meaning but slightly different phonetically, and the phonetic form

of the Scandinavian borrowing is preserved in English, having ousted

the English counterpart. For example, modern English to

give,

to

get

come from the Scandinavian gefa,

geta,

this ousted the English giefan

and gietan,

respectively. Similar English words: gift, forget, guild, gate,

again. -

There

may be a shift of meaning. Thus, the word dream

originally

meant “joy, pleasure”; under the influence of the related

Scandinavian word it developed its modern meaning.

-

French

borrowings

It

stands to reason that the Norman Conquest and the subsequent history

left deep traces in the English language, mainly in the form of

borrowings in words connected with such spheres of social and

political activity where French-speaking Normans had occupied for a

long time all places of importance. For example:

-

Government

and legislature:

government,

noble, baron, prince, duke, court, justice, judge, crime, prison,

condemn, sentence, parliament, etc.

-

military

life:

army,

battle, peace, banner, victory, general, colonel, lieutenant, major,

etc.

-

religion:

religion,

sermon, prey, saint, charity, etc.

-

city

crafts:

painter,

tailor, carpenter, etc. (but

country occupations remained English: shepherd, smith, etc.)

-

pleasure

and entertainment:

music,

art, feast, pleasure, leisure, supper, dinner, pork, beef, mutton,

etc. (but

the corresponding names of domestic animals remained English: pig,

cow, sheep)

-

words

of everyday life:

air,

place, river, large, age, boil, branch, brush, catch, change, chain,

chair, table, choice, cry, cost, etc.

-

relationship:

aunt,

uncle, nephew, cousin.

The

place of the French borrowings within the English language was

different:

-

A

word may be borrowed from the French language to denote notions

unknown to the English up to the time:

Government,

parliament, general, colonel, etc.

-

The

English synonym is ousted by the French borrowing:

English

French

micel

large

here

army

ēa

river

-

Both

the words are preserved, but they are stylistically different:

English

French

to

begin to commence

to

work to labour

to

leave to abandon

life

existence

look

regard

ship

vessel

As

we see, the French borrowings are generally more literary or even

bookish, the English word – a common one; but sometimes the English

word is more literary. Compare:

Foe

(native,

English)

– enemy (French

borrowing)

-

Sometimes

the English language borrowed many words with the same word-building

affix. The meaning of the affix in this case became clear to the

English-speaking people, and they began to add it to the English

words, thus forming word-hybrids. For instance: the suffix –ment

entered the language within such words as “government”,

“parliament”, “agreement”, but later there appeared such

English-French hybrids, such as fulfillment,

amazement

The

suffix –ance/-ence, which was an element of such borrowed words as

“innocence”,

“ignorance”, “repentance”,

now also forms words-hybrids, such as hindrance

A

similar thing: French borrowings “admirable”, “tolerable”,

“reasonable”, but also:

Readable,

eatable, unbearable.

-

One

of the consequences of the borrowings from French was the appearance

of the etymological doublets.

—

from the Common Indoeuropean:

native

borrowed

fatherly

paternal

—

from the Common Germanic:

native

borrowed

yard

garden

ward

guard

choose

choice

—

from Latin:

Earlier

later

(Old

English borrowing) (Middle English borrowing)

Mint

money

Inch

ounce

-

Due

to the great number of French borrowings these appeared in the

English language such families of words, which though similar in

their root meaning, are different in origin:

native

borrowed

mouth

oral

sun

solar

see

vision

-

There

are calques on the French phrase:

It’s

no doubt Se n’est doute

Without

doubt Sans doubte

Out

of doubt Hors de doute

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Middle English was the language spoken in England from about 1100 to 1500. Five major dialects of Middle English have been identified (Northern, East Midlands, West Midlands, Southern, and Kentish), but the «research of Angus McIntosh and others… supports the claim that this period of the language was rich in dialect diversity» (Barbara A. Fennell, A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach, 2001).

Major literary works written in Middle English include Havelok the Dane, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Piers Plowman, and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The form of Middle English that’s most familiar to modern readers is the London dialect, which was the dialect of Chaucer and the basis of what would eventually become standard English.

Middle English in Academics

Academicians and others have explained the use of Middle English in everything from its importance in English grammar, and modern English in general, to fatherhood, as the following quotes demonstrate.

Jeremy J. Smith

«[T]he transition from Middle to early modern English is above all the period of the elaboration of the English language. Between the late 14th and 16th centuries, the English language began increasingly to take on more functions. These changes in function had, it is argued here, a major effect on the form of English: so major, indeed, that the old distinction between ‘Middle’ and ‘modern’ retains considerable validity, although the boundary between these two linguistic epochs was obviously a fuzzy one.»

(«From Middle to Early Modern English.» The Oxford History of English, ed. by Lynda Mugglestone. Oxford University Press, 2006)

Rachel E. Moss

«Middle English varied enormously over time and by region; Angus McIntosh notes that there are over a thousand ‘dialectically differentiated’ varieties of Middle English. Indeed, some scholars go so far as to say that Middle English is ‘not… a language at all but rather something of a scholarly fiction, an amalgam of forms and sounds, writers and manuscripts, famous works and little-known ephemera.’ This is a little extreme, but certainly prior to the later fourteenth century Middle English was primarily a spoken rather than a written language, and did not have official administrative functions in either a secular or religious context. This has resulted in a critical tendency to place English at the bottom of the linguistic hierarchy of medieval England, with Latin and French as the dominant languages of discourse, instead of seeing the symbiotic relationship between English, French, and Latin…

«By the fifteenth century Middle English was extensively used in the written documentation of business, civic government, Parliament, and the royal household.»

(Fatherhood and Its Representations in Middle English Texts. D.S. Brewer, 2013)

Evelyn Rothstein and Andrew S. Rothstein

— «In 1066, William the Conqueror led the Norman invasion of England, marking the beginning of the Middle English period. This invasion brought a major influence to English from Latin and French. As is often the case with invasions, the conquerors dominated the major political and economic life in England. While this invasion had some influence on English grammar, the most powerful impact was on vocabulary.»

(English Grammar Instruction That Works! Corwin, 2009)

Seth Lerer

— «The core vocabulary of [Middle] English comprised the monosyllabic words for basic concepts, bodily functions, and body parts inherited from Old English and shared with the other Germanic languages. These words include: God, man, tin, iron, life, death, limb, nose, ear, foot, mother, father, brother, earth, sea, horse, cow, lamb.

«Words from French are often polysyllabic terms for the institutions of the Conquest (church, administration, law), for things imported with the Conquest (castles, courts, prisons), and terms of high culture and social status (cuisine, fashion, literature, art, decoration).»

(Inventing English: A Portable History of the Language. Columbia University Press, 2007)

A. C. Baugh and T. Cable

— «From 1150 to 1500 the language is known as Middle English. During this period the inflections, which had begun to break down during the end of the Old English period, become greatly reduced…

«By making English the language mainly of uneducated people, the Norman Conquest [in 1066] made it easier for grammatical changes to go forward unchecked.

«French influence is much more direct and observable upon the vocabulary. Where two languages exist side by side for a long time and the relations between the people speaking them are as intimate as they were in England, a considerable transference of words from one language to the other is inevitable…

«When we study the French words appearing in English before 1250, roughly 900 in number, we find that many of them were such as the lower classes would become familiar with through contact with a French-speaking nobility: (baron, noble, dame, servant, messenger, feast, minstrel, juggler, largess)… In the period after 1250,… the upper classes carried over into English an astonishing number of common French words. In changing from French to English, they transferred much of their governmental and administrative vocabulary, their ecclesiastical, legal, and military terms, their familiar words of fashion, food, and social life, the vocabulary of art, learning, and medicine.»

(A History of the English Language. Prentice-Hall, 1978)

Simon Horobin

— «French continued to occupy a prestigious place in English society, especially the Central French dialect spoken in Paris. This prompted an increase in the numbers of French words borrowed, especially those relating to French society and culture. As a consequence, English words concerned with scholarship, fashion, the arts, and food—such as college, robe, verse, beef—are often drawn from French (even if their ultimate origins lie in Latin). The higher status of French in this [late Middle English] period continues to influence the associations of pairs of synonyms in Modern English, such as begin-commence, look-regard, stench-odour. In each of these pairs, the French borrowing is of a higher register than the word inherited from Old English.»

(How English Became English. Oxford University Press, 2016)

Chaucer and Middle English

Probably the most famous author who wrote during the Middle English period was Geoffrey Chaucer, who penned the classic 14th-century work, «The Canterbury Tales,» but also other works, which present fine examples of how the language was used in the same time period. The modern-English translation is presented in brackets following the Middle English passage.

Canterbury Tales

«Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour…»

[«When the sweet showers of April have pierced

The drought of March, and pierced it to the root

And every vein is bathed in that moisture

Whose quickening force will engender the flower…»]

(General Prologue. Translation by David Wright. Oxford University Press, 2008)

«Troilus and Criseyde»

«Ye knowe ek that in forme of speeche is chaunge

Withinne a thousand yeer, and wordes tho

That hadden pris, now wonder nyce and straunge

Us thinketh hem, and yet thei spake hem so,

And spedde as wel in love as men now do;

Ek for to wynnen love in sondry ages,

In sondry londes, sondry ben usages.»

[«You know also that in (the) form of speech (there) is change

Within a thousand years, and words then

That had value, now wonderfully curious and strange

(To) us they seem, and yet they spoke them so,

And succeeded as well in love as men now do;

Also to win love in sundry ages,

In sundry lands, (there) are many usages.»]

(Translation by Roger Lass in «Phonology and Morphology.» A History of the English Language, edited by Richard M. Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Presentation on theme: «The Middle English Vocabulary»— Presentation transcript:

1

The Middle English Vocabulary

2

Borrowings came mostly from two sources:Scandinavian And French

Scandinavian borrowings were not so great, but they were mostly everyday words of very high frequency. There were such borrowings as bag anger skin happy take call window fog ugly

3

Apart from many place names (over1400)in – by, -thorpe and -thwaite some personal pronouns were borrowed as well. The Scandinavian forms þeir(they), þeim (them) and þeirra (their) ousted the OE. forms hie, him, hira. In some cases only the meaning of a word, not its form was changed. For example, ME word bloom has not only the meaning of ‘‘flower’’ but also ‘‘the technical meaning ‘‘of a thick bar or iron’’ The OE word bloma had only the second meaning. The first was borrowed from the Scandinavian word blom. The OE dream meant ‘‘joy’’ .Its present meaning came with the Scandinavians.

4

The number of French borrowings was much greater than the Scandinavian loan words

There were 2 stages of borrowing. During the 1st one words connected with titles of respect (E. sir, madam), ranks( prince, duke, noble). During the 2nd one words connected with administration and government (E. parliament, crown, reign) war (E. enemy, battle, war, victory, defence) religion ( pray, saint, miracle) art ( painting, colour, beauty, romance, sculpture, )

5