The combination of two or more words that have both grammatical and semantic connections between themselves is called a phrase. Words in a phrase are in a subordinate relationship.

The combination of two or more words that have both grammatical and semantic connections between themselves is called a phrase. Words in a phrase are in a subordinate relationship.

A submissive link, or subordination in linguistics, is a syntactic inequality between the parts of a structure. With regard to a phrase, such are words. A subordinate relationship assumes the presence of a main and dependent word.

Difference between main word and dependent

The main word and the dependent have different functions in a phrase. The main word always names something — an object, an action, a sign, and a dependent one clarifies, spreads and explains what was named. For example, in the phrase «green leaf» the adjective explains the property of the object, in the phrase «to perform a symphony» the noun explains what exactly was performed. In the first case, the dependent word is an adjective, in the second — a noun.

The connection between words in a phrase is revealed by means of a question that is posed from the main word to the dependent one, but not vice versa, for example: «the table (which one?) Is wooden.»

If one of the two words is expressed by a noun, and the other by a verb, while it is possible to pose a question from a noun to a verb (“the dog“what is he doing?) Barks”), this group of words cannot be considered a phrase at all. This is an uncommon proposal.

Dependent word for various types of subordination

There are many types of subordination, but only three of them can be represented in a phrase: coordination, management and adherence.

When agreed, the dependent word takes the same gender, case and number as the main one. In such a phrase, the noun is the main word, and the adjective, pronoun, ordinal or participle is dependent: «winter morning», «this woman», «third year», «washable wallpaper.»

When managing, the main word is expressed by a verb or a noun, which can be in any case, including the nominative, and the dependent — a noun, the case of which will be indirect (ie, any, except for the nominative), and this case is due to the meaning of the main word: “read a book «,» Love for the mother. » Giving a different form to the main word does not lead to a change in the form of the addict: «to learn a poem — I learn a poem», «the will to win — the will to win.»

When adjacent, the dependent word is associated with the main one exclusively by meaning, no grammatical changes occur with it. In this case, words that do not change at all can act as a dependent word — adverbs: «sings loudly», «very tired.»

Popular by topic

Definition

and general characteristics of the word-group.

There

are a lot of definitions concerning the word-group. The most

adequate one seems to be the following: the word-group is a

combination of at least two notional words which do not constitute

the sentence but are syntactically connected. According to some

other scholars (the majority of Western scholars and professors

B.Ilyish and V.Burlakova – in Russia), a combination of a notional

word with a function word (on

the table)

may be treated as a word-group as well. The problem is disputable as

the role of function words is to show some abstract relations and

they are devoid of nominative power. On the other hand, such

combinations are syntactically bound and they should belong

somewhere.

General

characteristics of the word-group are:

1)

As a naming unit it differs from a compound word because the number

of constituents in a word-group corresponds to the number of

different denotates:

a

black bird – чорний птах (2), a blackbird – дрізд

(1);

a loud speaker (2), a loudspeaker (1).

2)

Each component of the word-group can undergo grammatical changes

without destroying the identity of the whole unit: to

see a house — to see houses.

3)

A word-group is a dependent syntactic unit, it is not a

communicative unit and has no intonation of its own.

2.

Classification of word-groups.

Word-groups

can be classified on the basis of several principles:

-

According

to the type of syntagmatic relations: coordinate (you

and me), subordinate (to

see a house, a nice dress), predicative (him

coming, for him to come), -

According

to the structure: simple (all

elements are obligatory), expanded (to

read and translate the text –

expanded elements are equal in rank), extended (a

word takes a dependent element and this dependent element becomes

the head for another word: a

beautiful flower

– a very beautiful flower).

3.

Subordinate word-groups.

Subordinate

word-groups are based on the relations of dependence between the

constituents. This presupposes the existence of a governing

Element

which is called the

head and

the dependent element which is called the

adjunct (in

noun-phrases) or the

complement (in

verb-phrases).

According

to the nature of their heads, subordinate word-groups fall

into noun-phrases (NP)

– a

cup of tea, verb-phrases (VP)

– to

run fast, to see

a house, adjective

phrases (AP)

– good

for you, adverbial

phrases (DP)

– so

quickly, pronoun

phrases (IP)

– something

strange, nothing todo.

The

formation of the subordinate word-group depends on the valency of

its constituents. Valencyis

a potential ability of words to combine. Actual realization of

valency in speech is called combinability.

4.

The noun-phrase (NP).

Noun

word-groups are widely spread in English. This may be explained by a

potential ability of the noun to go into combinations with

practically all parts of speech. The NP consists of a noun-head and

an adjunct or adjuncts with relations of modification between them.

Three types of modification are distinguished here:

-

Premodification that

comprises all the units placed before the head: two

smart hard-working students. Adjuncts

used in pre-head position are called pre-posed adjuncts. -

Postmodification that

comprises all the units all the units placed after the

head: studentsfrom

Boston. Adjuncts

used in post-head position are called post-posed adjuncts. -

Mixed

modification that

comprises all the units in both pre-head and post-head position:two

smart hard-working students from

Boston.

|

Pre-posed |

|

Post-posed |

|

Pronoun |

Adj. |

|

|

Adj. |

Ven |

|

|

N2 |

Ving |

|

|

N`s |

prep.N2 |

|

|

Ven |

prepVing |

|

|

Ving |

D |

|

|

Num |

Num |

|

|

D |

wh-clause, |

X

5.

Noun-phrases with pre-posed adjuncts.

In

noun-phrases with pre-posed modifiers we generally find adjectives,

pronouns, numerals, participles, gerunds, nouns, nouns in the

genitive case (see the table). According to their position all

pre-posed adjuncts may be divided

into pre-adjectivals and adjectiavals.

The position of adjectivals is usually right before the noun-head.

Pre-adjectivals occupy the position before adjectivals. They fall

into two groups: a) lim

iters (to this

group belong mostly particles): just,

only, even, etc. and

b) determiners (articles,

possessive pronouns, quantifiers – the

first, the last).

Premodification

of nouns by nouns (N+N) is one of the most striking features about

the grammatical organization of English. It is one of devices to

make our speech both laconic and expressive at the same time.

Noun-adjunct groups result from different kinds of transformational

shifts. NPs with pre-posed adjuncts can signal a striking variety of

meanings:

world

peace – peace all over the world

silver box – a box

made of silver

table lamp – lamp for tables

table

legs – the legs of the table

river sand – sand from the

river

school child – a child who goes to school

The

grammatical relations observed in NPs with pre-posed adjuncts may

convey the following meanings:

-

subject-predicate

relations: weather

change; -

object

relations: health

service, women hater; -

adverbial

relations:

a)

of time: morning

star,

b)

place: world

peace, country house,

c)

comparison: button

eyes,

d)

purpose: tooth

brush.

It

is important to remember that the noun-adjunct is usually marked by

a stronger stress than the head.

Of

special interest is a kind of ‘grammatical idiom’ where the

modifier is reinterpreted into the head:a

devil of a man, an angel of a girl.

6.

Noun-phrases with post-posed adjuncts.

NPs

with post-posed may be classified according to the way of connection

into prepositionless andprepositional.

The basic prepositionless NPs with post-posed adjuncts are: Nadj.

– tea

strong,

NVen – the

shape unknown,

NVing – the

girl smiling,

ND – the

man downstairs,

NVinf – a

book to read,

NNum – room

ten.

The

pattern of basic prepositional NPs is N1 prep. N2. The most common

preposition here is ‘of’ – a

cup of tea, a

man of courage.

It may have quite different meanings: qualitative — a

woman of sense, predicative – the

pleasure of the company, objective – the

reading of the newspaper,partitive – the

roof of the house.

7.

The verb-phrase.

The

VP is a definite kind of the subordinate phrase with the verb as the

head. The verb is considered to be the semantic and structural

centre not only of the VP but of the whole sentence as the verb

plays an important role in making up primary predication that serves

the basis for the sentence. VPs are more complex than NPs as there

are a lot of ways in which verbs may be combined in actual usage.

Valent properties of different verbs and their semantics make it

possible to divide all the verbs into several groups depending on

the nature of their complements (see the table ‘Syntagmatic

properties of verbs’, Lecture 6).

8.

Classification of verb-phrases.

VPs

can be classified according to the nature of their complements –

verb complements may be nominal (to

see a house)

and adverbial (to

behave well).

Consequently, we distinguish nominal,

adverbial and mixed complementation.

Nominal

complementation takes place when one or more nominal complements

(nouns or pronouns) are obligatory for the realization of potential

valency of the verb: to

give smth. to smb., to phone smb., to hear smth.(smb.), etc.

Adverbial

complementation occurs when the verb takes one or more adverbial

elements obligatory for the realization of its potential valency: He

behaved well, I live …in Kyiv (here).

Mixed

complementation – both nominal and adverbial elements are

obligatory: He

put his hat on he table (nominal-adverbial).

According

to the structure VPs

may be basic or simple (to

take a book) –

all elements are obligatory; expanded (to

read and

translate the text,

to read

books and

newspapers)

andextended (to

read an English book).

9.

Predicative word-groups.

Predicative

word combinations are distinguished on the basis of secondary

predication. Like sentences, predicative word-groups are binary in

their structure but actually differ essentially in their

organization. The sentence is an independent communicative unit

based on primary predication while the predicative word-group is a

dependent syntactic unit that makes up a part of the sentence. The

predicative word-group consists of a nominal element (noun, pronoun)

and a non-finite form of the verb: N + Vnon-fin. There are

Gerundial, Infinitive and Participial word-groups (complexes) in the

English language: his

reading, for

me to know,

the boy running, etc.)

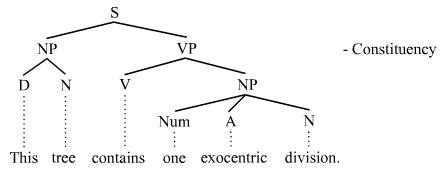

n theoretical

linguistics,

a distinction is made

between endocentric and exocentric constructions.

A grammatical construction

(e.g. a phrase or

compound word) is said to be endocentric if

it fulfills the same linguistic function as one of its parts,

and exocentric if

it does not.[1] The

distinction reaches back at least to Bloomfield’s

work of the 1930s.[2] Such

a distinction is possible only in phrase

structure grammars(constituency

grammars), since in dependency

grammars all

constructions are necessarily endocentric.[3]

Endocentric

construction[edit]

An

endocentric construction consists of an obligatory head and

one or more dependents, whose presence serves to narrow the meaning

of the head. For example:

big house —

Noun phrase (NP)

sing songs —

Verb phrase (VP)

very long —

Adjective phrase (AP)

These

phrases are indisputably endocentric. They are endocentric because

the one word in each case carries the bulk of the semantic content

and determines the grammatical category to which the

wholeconstituent will

be assigned. The phrase big

house is

a noun

phrase in line with its part house,

which is a noun. Similarly, sing

songs is

a verb

phrase in line with its part sing,

which is a verb. The same is true ofvery

long;

it is an adjective

phrase in line with its part long,

which is an adjective. In more formal terms, the distribution of an

endocentric construction is functionally equivalent, or approaching

equivalence, to one of its parts, which serves as the center, or

head, of the whole. An endocentric construction is also known as

a headed construction,

where the head is contained «inside» the construction.

Exocentric

construction[edit]

An

exocentric construction consists of two or more parts, whereby the

one or the other of the parts cannot be viewed as providing the bulk

of the semantic content of the whole. Further, the syntactic

distribution of the whole cannot be viewed as being determined by

the one or the other of the parts. The classic instance of an

exocentric construction is the sentence (in a phrase

structure grammar).[4] The

traditional binary division[5] of

the sentence (S) into a subject noun

phrase (NP) and a predicate verb

phrase (VP) was exocentric:

Hannibal

destroyed Rome. — Sentence (S)

Since

the whole is unlike either of its parts, it is exocentric. In other

words, since the whole is neither a noun (N) like Hannibal nor

a verb phrase (VP) like destroyed

Rome but

rather a sentence (S), it is exocentric. With the advent of X-bar

Theory in Transformational

Grammar in the 1970s, this traditional exocentric division

was largely abandoned and replaced by an endocentric analysis,

whereby the sentence is viewed as an inflection

phrase (IP), which is essentially a projection of the verb

(a fact that makes the sentence a big VP in a sense). Thus with the

advent of X-bar Theory, the endocentric vs. exocentric distinction

started to become less important in the theory of syntax, for

without the concept of exocentricity, the notion of endocentricity

was becoming vacuous. In theories of morphology however,

the distinction remains, since certaincompounds seem

to require an exocentric analysis, e.g. have-not in Bill

is a have-not.

For a class of compounds described as exocentric, see bahuvrihi.

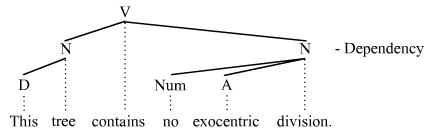

The

distinction in dependency grammars[edit]

The

endo- vs. exocentric distinction is possible in phrase

structure grammars (= constituency grammars), since they

are constituency-based. The distinction is hardly present

in dependency

grammars, since they are dependency-based. In other words,

dependency-based structures are necessarily endocentric, i.e. they

are necessarily headed structures. Dependency grammars by definition

were much less capable of acknowledging the types of divisions that

constituency enables. Acknowledging exocentric structure

necessitates that one posit more nodes in the syntactic (or

morphological) structure than one has actual words or morphs in the

phrase or sentence at hand. What this means is that a significant

tradition in the study of syntax and grammar has been incapable from

the start of acknowledging the endo- vs. exocentric distinction, a

fact that has generated confusion about what should count as an

endo- or exocentric structure.

Representing

endo- and exocentric structures[edit]

Theories

of syntax (and morphology) represent endocentric and exocentric

structures using tree diagrams and specific labeling conventions.

The distinction is illustrated here using the following trees. The

first three trees show the distinction in a constituency-based

grammar, and the second two trees show the same structures in a

dependency-based grammar:

The

upper two trees on the left are endocentric since each time, one of

the parts, i.e. the head, projects its category status up to the

mother node. The upper tree on the right, in contrast, is

exocentric, because neither of the parts projects its category

status up to the mother node; Z is a category distinct from X or Y.

The two dependency trees show the manner in which dependency-based

structures are inherently endocentric. Since the number of nodes in

the tree structure is necessarily equal to the number of elements

(e.g. words) in the string, there is no way to assign the whole

(i.e. XY) a category status that is distinct from both X and Y.

Traditional

phrase structure trees are mostly endocentric, although the initial

binary division of the clause is exocentric (S → NP VP), as

mentioned above, e.g.

This

tree structure contains four divisions, whereby only one of these

division is exocentric (the highest one). The other three divisions

are endocentric because the mother node has the same basic category

status as one of its daughters. The one exocentric division

disappears in the corresponding dependency tree:

Dependency

positions the finite verb as the root of the entire tree, which

means the initial exocentric division is impossible. This tree is

entirely endocentric.

A

note about coordinate structures[edit]

While

exocentric structures have largely disappeared from most theoretical

analyses of standard sentence structure, many theories of syntax

still assume (something like) exocentric divisions for coordinate

structures,

e.g.

[Sam]

and [Larry] arrived.

She

[laughed] and [cried].

[Should

I] or [should I not] go to that conference?

The

brackets each time mark the conjuncts of a coordinate structure,

whereby this coordinate structure includes the material appearing

between the left-most bracket and the right-most bracket; the

coordinator is positioned between the conjuncts. Coordinate

structures like these do not lend themselves to an endocentric

analysis in any clear way, nor to an exocentric analysis. One might

argue that the coordinator is the head of the coordinate structure,

which would make it endocentric. This argument would have to ignore

the numerous occurrences of coordinate structures that lack a

coordinator (asyndeton),

however. One might therefore argue instead that coordinate

structures like these are multi-headed, each conjunct being or

containing a head. The difficulty with this argument, however, is

that the traditional endocentric vs. exocentric distinction did not

foresee the existence of multi-headed structures, which means that

it did not provide a guideline for deciding whether a multi-headed

structure should be viewed as endo- or exocentric. Coordinate

structures thus remain a problem area for the endo- vs. exocentric

distinction in general.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

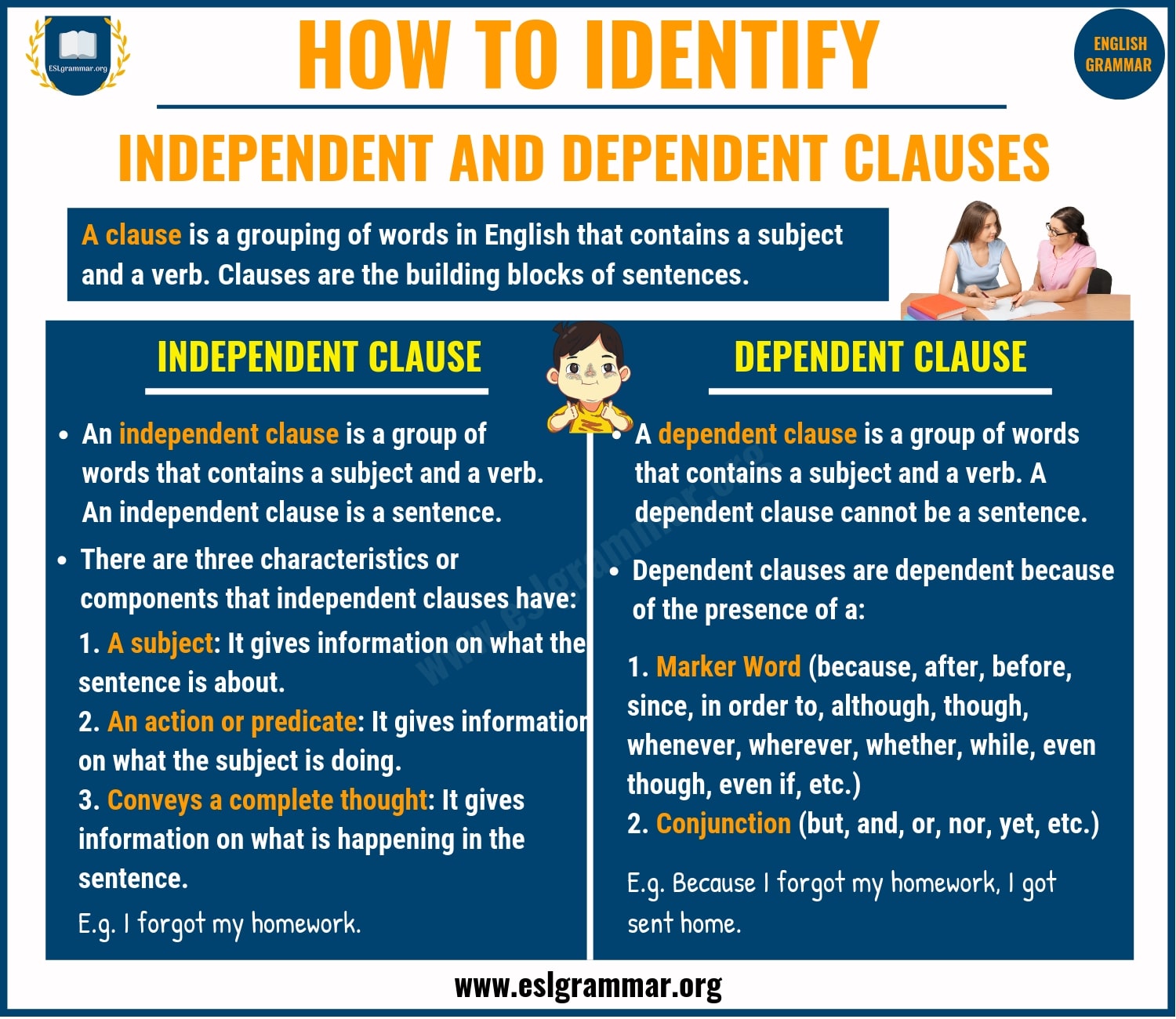

A dependent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb but does not express a complete thought. … The thought is incomplete.) Dependent Marker Word. A dependent marker word is a word added to the beginning of an independent clause that makes it into a dependent clause.

Related Posts:

- What is the difference between defining and non-defining?

— Non-defining clauses still add extra information, but… (Read More) - What is defining clause and non-defining clause?

— In defining relative clauses, the pronouns who,… (Read More) - What is non-defining adjective clause?

— An adjective clause may be defining or… (Read More) - What is difference between defining and non-defining relative clauses?

— Differences Defining and Non-Defining Relative Clauses. …… (Read More) - What is clause definition and examples?

— A clause is a group of words… (Read More) - What is the difference between a phrase and a clause?

— DEFINITION OF CLAUSE AND PHRASE: A clause… (Read More) - How do you identify a clause?

— Steps to identifying clausesIdentify any verbs and… (Read More) - Whats a clause in a sentence?

— What is a clause? Clauses are groups… (Read More) - Why do we use clauses?

— A clause is the basic building block… (Read More) - How do we write a clause?

— In its simplest form, a clause in… (Read More)

A clause is a group of words that includes two obligatory elements:

- a subject – expresses who or what does something. To find the subject, ask who or what performs the activity.

- a predicate – the word expressing the activity. The predicate changes its form depending on the subject (I play but he plays) and depending on the tense (he plays often but he played yesterday). The predicate is always a verb; hence, the easiest way to find the predicate of the clause is to find the verb whose form changes depending on the subject and the tense.

(1) Mary is writing a letter. [Mary is the subject, writes is the predicate]

(2) The new theory captures the data successfully. [the new theory is the subject, captures is the predicate]

There are two types of clauses:

- independent clause – it expresses a complete thought and can stand alone.

(3) John was hired by an IT company.

(4) The majority of politicians do not accept global warming as a real threat.

- dependent clause – it does not express a complete thought but just a part of it. Dependent clauses cannot stand alone.

(5) shortly after he graduated in Computer Science [an incomplete thought]

(6) although scientists have found strong indications of a global temperature rise [an incomplete thought]

Dependent clauses are commonly introduced by special markers (called subordinate conjunctions), such as, if, whether, because, although, since, when, while, unless, even though, whenever (follow this link for a fuller list).

A sentence consists of one or more clauses. A sentence that is made up of a single clause is a simple sentence. The single clause has to be an independent clause in order for the sentence to be complete. The examples in (1)-(4) are all simple sentences consisting of just one independent clause.

A sentence can also contain more than one clause. Such a sentence is called a compound sentence. Compound sentences can consist of two or more independent clauses (connected by and, but, or, nor)

(7) John was hired by an IT company, but Mary did not find a job.

(8) We have to finish the project first, and then we can take a holiday.

A compound sentence can also combine independent clauses with dependent clauses.

(9) Shortly after John graduated in Computer Science, he was hired by an IT company.

(10) The majority of politicians do not accept global warming as a real threat, although scientists have found strong indications of a global temperature rise.

A compound sentence has to contain at least one independent clause to be complete.

Sometimes, complex phrases can be used instead of a dependent clause to encode the same information. This creates a longer simple sentence with just one subject and one verb.

(11) Shortly after his graduation in Computer Science, John was hired by an IT company.

(12) The majority of politicians do not accept global warming as a real threat despite the strong indications of a global temperature rise.

The groups of words “shortly after his graduation in Computer Science” and “despite the strong indications of a global temperature rise” are not clauses because they have no subject (the words John and scientists are missing) and no predicate (graduation is not a verb but a noun derived from a verb).

Independent and dependent clauses are fundamental parts of writing. But what are these clauses? How do they differ? And how do you use them? In this post, we look the basics of independent and dependent clauses.

What Is a Clause?

A ‘clause’ is a group of words that contains a subject and a predicate. This could be a sentence, part of a sentence, or even a sentence fragment.

Every sentence will include at least one clause, but you can also combine independent and dependent clauses. We will look at how this works below.

Independent Clauses

An independent clause is also known as a ‘main clause’. A clause is independent if it works as a sentence by itself. We can make an independent clause with just a noun and a verb:

|

Noun (Subject) |

Verb (Predicate) |

|

Dogs… |

…bark. |

Here, we have a noun (dogs) as the subject of the clause and a verb (bark) as the predicate. And this works as a standalone sentence because it expresses a complete thought (the thought of dogs barking).

We can also combine two (or more) independent clauses in a single sentence. To do this, we would use a coordinating conjunction between the clauses:

|

Clause 1 |

Conjunction |

Clause 2 |

|

Dogs bark… |

…and… |

…cats meow. |

Here, then, we have multiple independent clauses in one sentence. But these clauses are still ‘independent’ because we could write either one by itself:

Dogs bark. Cats meow.

Dependent Clauses

A dependent clause, also known as a ‘subordinate clause’, adds extra information to a sentence. It cannot, however, work as a sentence by itself. Take the following complex sentence, for example:

|

Independent Clause |

Dependent Clause |

|

My dog barks… |

…when he sees a cat. |

The second clause above is ‘subordinate’ because it ‘depends’ on the main clause to make sense. We can see this if we write each clause separately:

Independent Clause: My dog barks. ✓

Dependent Clause: When he sees a cat. ✗

In other words, ‘when he sees a cat’ does not make sense by itself. But as part of a sentence, it tells us something about the main clause. All dependent clauses add information like this, but they can function in different ways:

- Adverbial clauses tell us something about how a main clause occurs. For example, ‘when he sees a cat’ tells us something about the situation in which ‘my dog’ barks.

- Adjectival clauses modify a noun or noun phrase in a sentence. For instance, we could say ‘Dogs that bark at cats should be kept indoors’. In this sentence, ‘that bark at cats’ is an adjectival clause because it tells us what type of dog the sentence is about.

- Nominal clauses (or noun clauses) function like a noun. For instance, we could say, ‘My dog goes wherever I go’. The nominal clause here is ‘wherever I go’, which is the object of the verb ‘go’ in the main clause.

However, one thing all dependent clauses have in common is that they only make sense when attached to a main clause.

Summary: Independent and Dependent Clauses

A ‘clause’ is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. Two of the most important types of clause are ‘independent’ and ‘dependent’ clauses:

- An independent clause (or main clause) expresses a complete thought. It can be a sentence by itself, but it may also be part of a longer sentence.

- A dependent clause (or subordinate clause) is part of a sentence that contains a subject and a verb but does not express a complete thought.

The key is to remember that only independent clauses work by themselves. If you use a dependent clause by itself, you will end up with a sentence fragment. And to make sure your written work is free from grammatical errors, don’t forget to have it proofread.

Summary:

This handout defines dependent and independent clauses and explores how they are treated in standard usage.

When you want to use commas and semicolons in sentences and when you are concerned about whether a sentence is or is not a fragment, a good way to start is to be able to recognize dependent and independent clauses. The definitions offered here will help you with this.

Independent Clause

An independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought. An independent clause is a sentence.

Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz.

Dependent Clause

A dependent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and verb but does not express a complete thought. A dependent clause cannot be a sentence. Often a dependent clause is marked by a dependent marker word.

When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz . . . (What happened when he studied? The thought is incomplete.)

Dependent Marker Word

A dependent marker word is a word added to the beginning of an independent clause that makes it into a dependent clause.

When Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz, it was very noisy.

Some common dependent markers: after, although, as, as if, because, before, even if, even though, if, in order to, since, though, unless, until, whatever, when, whenever, whether, and while.

Connecting independent clauses

There are two types of words that can be used as connectors at the beginning of an independent clause: coordinating conjunctions and independent marker words.

1. Coordinating Conjunction

The seven coordinating conjunctions used as connecting words at the beginning of an independent clause are and, but, for, or, nor, so, and yet. When the second independent clause in a sentence begins with a coordinating conjunction, a comma is needed before the coordinating conjunction:

Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz, but it was hard to concentrate because of the noise.

2. Independent Marker Word

An independent marker word is a connecting word used at the beginning of an independent clause. These words can always begin a sentence that can stand alone. When the second independent clause in a sentence has an independent marker word, a semicolon is needed before the independent marker word.

Jim studied in the Sweet Shop for his chemistry quiz; however, it was hard to concentrate because of the noise.

Some common independent markers: also, consequently, furthermore, however, moreover, nevertheless, and therefore.

Connecting dependent and independent clauses

Subordinating conjunctions allow writers to construct complex sentences, which have an independent clause and a subordinate (or dependent) clause. Either clause can come first.

The students acted differently whenever a substitute taught the class.

Whenever a substitute taught the class, the students acted differently.

Note that the clauses are separated with a comma when the dependent clause comes first.

Some common subordinating conjunctions: after, as, before, once, since, until, and while.

Some Common Errors to Avoid

Comma Splices

A comma splice is the use of a comma between two independent clauses. You can usually fix the error by changing the comma to a period and therefore making the two clauses into two separate sentences, by changing the comma to a semicolon, or by making one clause dependent by inserting a dependent marker word in front of it.

Incorrect: I like this class, it is very interesting.

- Correct: I like this class. It is very interesting.

- (or) I like this class; it is very interesting.

- (or) I like this class, and it is very interesting.

- (or) I like this class because it is very interesting.

- (or) Because it is very interesting, I like this class.

Fused Sentences

Fused sentences happen when there are two independent clauses not separated by any form of punctuation. This error is also known as a run-on sentence. The error can sometimes be corrected by adding a period, semicolon, or colon to separate the two sentences.

Incorrect: My professor is intelligent I’ve learned a lot from her.

- Correct: My professor is intelligent. I’ve learned a lot from her.

- (or) My professor is intelligent; I’ve learned a lot from her.

- (or) My professor is intelligent, and I’ve learned a lot from her.

- (or) My professor is intelligent; moreover, I’ve learned a lot from her.

Sentence Fragments

Sentence fragments happen by treating a dependent clause or other incomplete thought as a complete sentence. You can usually fix this error by combining it with another sentence to make a complete thought or by removing the dependent marker.

Incorrect: Because I forgot the exam was today.

- Correct: Because I forgot the exam was today, I didn’t study.

- (or) I forgot the exam was today.

Independent and Dependent Clauses! Learn the definition and usage of independent and dependent clauses with useful examples and free ESL printable infographic.

A clause is a grouping of words in English that contains a subject and a verb. Clauses are the building blocks of sentences. They can be of two types: independent and dependent. It is important for the purpose of sentence formation to be able to recognize independent and dependent clauses.

Independent Clause

What is an independent clause?

An independent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. An independent clause is a sentence. Independent clauses are clauses that express a complete thought. They can function as sentences. These are clauses that can function on their own. They do not need to be joined to other clauses, because they contain all the information required to be a complete sentence.

There are three characteristics or components that independent clauses have:

1. A subject: It gives information on what the sentence is about.

2. An action or predicate: It gives information on what the subject is doing.

3. Conveys a complete thought: It gives information on what is happening in the sentence.

For example: ‘Ram left to buy supplies‘ is an independent clause, and if you end it with a full stop, it becomes a sentence.

- He ran fast.

- I was late to work.

- Tom reads.

- You need to sing up.

- I can run a mile in five minutes.

- …

Dependent Clause

What is a dependent clause?

A dependent clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. A dependent clause cannot be a sentence. They do not express complete thoughts, and thus cannot function as sentences. They are usually marked by dependant marker words. It is a word that is added to the beginning of an independent clause that makes it into a dependent clause. Dependent clauses are dependent because of the presence of a:

1. Marker Word (because, after, before, since, in order to, although, though, whenever, wherever, whether, while, even though, even if, etc.)

2. Conjunction (but, and, or, nor, yet, etc.)

For example: ‘When Ram left to buy supplies’ can not be a sentence because it is an incomplete thought. What happened when Ram went to the shop? Here, ‘when’ functions as a ‘dependent marker word’; this term refers to words which, when added to the beginnings of independent clauses or sentences, transform them into dependent clauses.

Other examples of dependent marker words are after, although, as, as if, because, before, if, in order to, since, though, unless, until, whatever, when, whenever, whether, and while.

Dependent clauses, thus, need to be combined with independent clauses to form full sentences. For example: ‘When Ram left to buy supplies, Rohan snuck in and stole the money’ is a complete sentence.

- Because I woke up late this morning… (what happened?)

- When we arrived in class… (what occurred?)

- Because I forgot my homework, I got sent home.

- David, who likes books, read a book.

- I was just getting into the bath when the phone rang.

- …

Independent and Dependent Clauses | Infographic