When you start breaking it down, the English language is pretty complicated—especially if you’re trying to learn it from scratch! One of the most important English words to understand is the.

But what part of speech is the word the, and when should it be used in a sentence? Is the word the a preposition? Is the a pronoun? Or is the word the considered a different part of speech?

To help you learn exactly how the word the works in the English language, we’re going to do the following in this article:

- Answer the question, «What part of speech is the?»

- Explain how to use the correctly in sentences, with examples

- Provide a full list of other words that are classified as the same part of speech as the in the English language

Okay, let’s get started learning about the word the!

In the English language the word the is classified as an article, which is a word used to define a noun. (More on that a little later.)

But an article isn’t one of the eight parts of speech. Articles are considered a type of adjective, so «the» is technically an adjective as well. However, «the» can also sometimes function as an adverb in certain instances, too.

In short, the word «the» is an article that functions as both an adjective and an adverb, depending on how it’s being used. Having said that, the is most commonly used as an article in the English language. So, if you were wondering, «Is the a pronoun, preposition, or conjunction,» the answer is no: it’s an article, adjective, and an adverb!

While we might think of an article as a story that appears in a newspaper or website, in English grammar, articles are words that help specify nouns.

The as an Article

So what are «articles» in the English language? Articles are words that identify nouns in order to demonstrate whether the noun is specific or nonspecific. Nouns (a person, place, thing, or idea) can be identified by two different types of articles in the English language: definite articles identify specific nouns, and indefinite articles identify nonspecific nouns.

The word the is considered a definite article because it defines the meaning of a noun as one particular thing. It’s an article that gives a noun a definite meaning: a definite article. Generally, definite articles are used to identify nouns that the audience already knows about. Here’s a few examples of how «the» works as a definite article:

We went to the rodeo on Saturday. Did you see the cowboy get trampled by the bull?

This (grisly!) sentence has three instances of «the» functioning as a definite article: the rodeo, the cowboy, and the bull. Notice that in each instance, the comes directly before the noun. That’s because it’s an article’s job to identify nouns.

In each of these three instances, the refers to a specific (or definite) person, place, or thing. When the speaker says the rodeo, they’re talking about one specific rodeo that happened at a certain place and time. The same goes for the cowboy and the bull: these are two specific people/animals that had one kinda terrible thing happen to them!

It can be a bit easier to see how definite articles work if you see them in the same sentence as an indefinite article (a or an). This sentence makes the difference a lot more clear:

A bat flew into the restaurant and made people panic.

Okay. This sentence has two articles in it: a and the. So what’s the difference? Well, you use a when you’re referring to a general, non-specific person, place, or thing because its an indefinite article. So in this case, using a tells us this isn’t a specific bat. It’s just a random bat from the wild that decided to go on an adventure.

Notice that in the example, the writer uses the to refer to the restaurant. That’s because the event happened at a specific time and at a specific place. A bat flew into one particular restaurant to cause havoc, which is why it’s referred to as the restaurant in the sentence.

The last thing to keep in mind is that the is the only definite article in the English language, and it can be used with both singular and plural nouns. This is probably one reason why people make the mistake of asking, «Is the a pronoun?» Since articles, including the, define the meaning of nouns, it seems like they could also be combined with pronouns. But that’s not the case. Just remember: articles only modify nouns.

Adjectives are words that help describe nouns. Because «the» can describe whether a noun is a specific object or not, «the» is also considered an adjective.

The as an Adjective

You know now that the is classified as a definite article and that the is used to refer to a specific person, place, or thing. But defining what part of speech articles are is a little bit tricky.

There are eight parts of speech in the English language: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections. The thing about these eight parts of speech in English is that they contain smaller categories of types of words and phrases in the English language. Articles are considered a type of determiner, which is a type of adjective.

Let’s break down how articles fall under the umbrella of «determiners,» which fall under the umbrella of adjectives. In English, the category of «determiners» includes all words and phrases in the English language that are combined with a noun to express an aspect of what the noun is referring to. Some examples of determiners are the, a, an, this, that, my, their, many, few, several, each, and any. The is used in front of a noun to express that the noun refers to a specific thing, right? So that’s why «the» can be considered a determiner.

And here’s how determiners—including the article the—can be considered adjectives. Articles and other determiners are sometimes classified as adjectives because they describe the nouns that they precede. Technically, the describes the noun it precedes by communicating specificity and directness. When you say, «the duck,» you’re describing the noun «duck» as referring to a specific duck. This is different than saying a duck, which could mean any one duck anywhere in the world!

When «the» comes directly before a word that’s not a noun, then it’s operating as an adverb instead of an adjective.

The as an Adverb

Finally, we mentioned that the can also be used as an adverb, which is one of the eight main parts of speech we outlined above. Adverbs modify or describe verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, but never modify nouns.

Sometimes, the can be used to modify adverbs or adjectives that occur in the comparative degree. Adverbs or adjectives that compare the amounts or intensity of a feeling, state of being, or action characterizing two or more things are in the comparative degree. Sometimes the appears before these adverbs or adjectives to help convey the comparison!

Here’s an example where the functions as an adverb instead of an article/adjective:

Lainey believes the most outrageous things.

Okay. We know that when the is functioning as an adjective, it comes before a noun in order to clarify whether it’s specific or non-specific. In this case, however, the precedes the word most, which isn’t a noun—it’s an adjective. And since an adverb modifies an adjective, adverb, or verb, that means the functions as an adverb in this sentence.

We know that can be a little complicated, so let’s dig into another example together:

Giovanni’s is the best pizza place in Montana.

The trick to figuring out whether the article the is functioning as an adjective or an adverb is pretty simple: just look at the word directly after the and figure out its part of speech. If that word is a noun, then the is functioning as an adjective. If that word isn’t a noun, then the is functioning like an adverb.

Now, reread the second example. The word the comes before the word best. Is best a noun? No, it isn’t. Best is an adjective, so we know that the is working like an adverb in this sentence.

How to Use The Correctly in Sentences

An important part of answering the question, «What part of speech is the word the?» includes explaining how to use the correctly in a sentence. Articles like the are some of the most common words used in the English language. So you need to know how and when to use it! And since using the as an adverb is less common, we’ll provide examples of how the can be used as an adverb as well.

Using The as an Article

In general, it is correct and appropriate to use the in front of a noun of any kind when you want to convey specificity. It’s often assumed that you use the to refer to a specific person, place, or thing that the person you’re speaking to will already be aware of. Oftentimes, this shared awareness of who, what, or where «the» is referring to is created by things already said in the conversation, or by context clues in a given social situation.

Let’s look at an example here:

Say you’re visiting a friend who just had a baby. You’re sitting in the kitchen at your friend’s house while your friend makes coffee. The baby, who has been peacefully dozing in a bassinet in the living room, begins crying. Your friend turns to you and asks, «Can you hold the baby while I finish doing this?»

Now, because of all of the context surrounding the social situation, you know which baby your friend is referring to when they say, the baby. There’s no need for further clarification, because in this case, the gives enough direct and specific meaning to the noun baby for you to know what to do!

In many cases, using the to define a noun requires less or no awareness of an immediate social situation because people have a shared common knowledge of the noun that the is referring to. Here are two examples:

Are you going to watch the eclipse tomorrow?

Did you hear what the President said this morning?

In the first example, the speaker is referring to a natural phenomenon that most people are aware of—eclipses are cool and rare! When there’s going to be an eclipse, everyone knows about it. If you started a conversation with someone by saying, «Are you going to watch the eclipse tomorrow?» it’s pretty likely they’d know which eclipse the is referring to.

In the second example, if an American speaking to another American mentions what the President said, the other American is likely going to assume that the refers to the President of the United States. Conversely, if two Canadians said this to one another, they would likely assume they’re talking about the Canadian prime minister!

So in many situations, using the before a noun gives that noun specific meaning in the context of a particular social situation.

Using The as an Adverb

Now let’s look at an example of how «the» can be used as an adverb. Take a look at this sample sentence:

The tornado warning made it all the more likely that the game would be canceled.

Remember how we explained that the can be combined with adverbs that are making a comparison of levels or amounts of something between two entities? The example above shows how the can be combined with an adverb in such a situation. The is combined with more and likely to form an adverbial phrase.

So how do you figure this out? Well, if the words immediately after the are adverbs, then the is functioning as an adverb, too!

Here’s another example of how the can be used as an adverb:

I had the worst day ever.

In this case, the is being combined with the adverb worst to compare the speaker’s day to the other days. Compared to all the other days ever, this person’s was the worst…period. Some other examples of adverbs that you might see the combined with include all the better, the best, the bigger, the shorter, and all the sooner.

One thing that can help clarify which adverbs the can be combined with is to check out a list of comparative and superlative adverbs and think about which ones the makes sense with!

3 Articles in the English Language

Now that we’ve answered the question, «What part of speech is the?», you know that the is classified as an article. To help you gain a better understanding of what articles are and how they function in the English language, here’s a handy list of 3 words in the English language that are also categorized as articles.

|

Article |

Type of Article |

What It Does |

Example Sentence |

|

The |

Definite Article |

Modifies nouns by giving them a specific meaning |

Please fold the laundry. Do you want to go to the concert? |

|

A |

Indefinite Article |

Modifies a noun that refers to a general idea; appears before nouns that begin with a consonant. |

Do you want to go to a concert? |

|

An |

Indefinite Article |

Modifies a noun that refers to a general idea; appears before nouns that begin with a vowel. |

Do you want to go to an arcade? Let’s get an iguana. |

What’s Next?

If you’re looking for more grammar resources, be sure to check out our guides on every grammar rule you need to know to ace the SAT (or the ACT)!

Learning more about English grammar can be really helpful when you’re studying a foreign language, too. We highly recommend that you study a foreign language in high school—not only is it great for you, it looks great on college applications, too. If you’re not sure which language to study, check out this helpful article that will make your decision a lot easier.

Speaking of applying for college…one of the most important parts of your application packet is your essay. Check out this expert guide to writing college essays that will help you get into your dream school.

Need more help with this topic? Check out Tutorbase!

Our vetted tutor database includes a range of experienced educators who can help you polish an essay for English or explain how derivatives work for Calculus. You can use dozens of filters and search criteria to find the perfect person for your needs.

Have friends who also need help with test prep? Share this article!

About the Author

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers’ or writers’ composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domains such as phonology, morphology, and syntax, often complemented by phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics. There are currently two different approaches to the study of grammar: traditional grammar and theoretical grammar.

Fluent speakers of a language variety or lect have effectively internalized these constraints,[1] the vast majority of which – at least in the case of one’s native language(s) – are acquired not by conscious study or instruction but by hearing other speakers. Much of this internalization occurs during early childhood; learning a language later in life usually involves more explicit instruction.[2] In this view, grammar is understood as the cognitive information underlying a specific instance of language production.

The term «grammar» can also describe the linguistic behavior of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals. Differences in scales are important to this sense of the word: for example, the term «English grammar» could refer to the whole of English grammar (that is, to the grammar of all the speakers of the language), in which case the term encompasses a great deal of variation.[3] At a smaller scale, it may refer only to what is shared among the grammars of all or most English speakers (such as subject–verb–object word order in simple declarative sentences). At the smallest scale, this sense of «grammar» can describe the conventions of just one relatively well-defined form of English (such as standard English for a region).

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be referred to as grammar. A reference book describing the grammar of a language is called a «reference grammar» or simply «a grammar» (see History of English grammars). A fully explicit grammar, which exhaustively describes the grammatical constructions of a particular speech variety, is called descriptive grammar. This kind of linguistic description contrasts with linguistic prescription, an attempt to actively discourage or suppress some grammatical constructions while codifying and promoting others, either in an absolute sense or about a standard variety. For example, some prescriptivists maintain that sentences in English should not end with prepositions, a prohibition that has been traced to John Dryden (13 April 1668 – January 1688) whose unexplained objection to the practice perhaps led other English speakers to avoid the construction and discourage its use.[4][5] Yet preposition stranding has a long history in Germanic languages like English, where it is so widespread as to be a standard usage.

Outside linguistics, the term grammar is often used in a rather different sense. It may be used more broadly to include conventions of spelling and punctuation, which linguists would not typically consider as part of grammar but rather as part of orthography, the conventions used for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set of prescriptive norms only, excluding those aspects of a language’s grammar which are not subject to variation or debate on their normative acceptability. Jeremy Butterfield claimed that, for non-linguists, «Grammar is often a generic way of referring to any aspect of English that people object to.»[6]

Etymology[edit]

The word grammar is derived from Greek γραμματικὴ τέχνη (grammatikḕ téchnē), which means «art of letters», from γράμμα (grámma), «letter», itself from γράφειν (gráphein), «to draw, to write».[7] The same Greek root also appears in the words graphics, grapheme, and photograph.

History[edit]

The first systematic grammar of Sanskrit, originated in Iron Age India, with Yaska (6th century BC), Pāṇini (6th–5th century BC[8]) and his commentators Pingala (c. 200 BC), Katyayana, and Patanjali (2nd century BC). Tolkāppiyam, the earliest Tamil grammar, is mostly dated to before the 5th century AD. The Babylonians also made some early attempts at language description.[9]

Grammar appeared as a discipline in Hellenism from the 3rd century BC forward with authors such as Rhyanus and Aristarchus of Samothrace. The oldest known grammar handbook is the Art of Grammar (Τέχνη Γραμματική), a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively, written by the ancient Greek scholar Dionysius Thrax (c. 170–c. 90 BC), a student of Aristarchus of Samothrace who founded a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax’s grammar book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.[10] Latin grammar developed by following Greek models from the 1st century BC, due to the work of authors such as Orbilius Pupillus, Remmius Palaemon, Marcus Valerius Probus, Verrius Flaccus, and Aemilius Asper.

The grammar of Irish originated in the 7th century with the Auraicept na n-Éces. Arabic grammar emerged with Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali in the 7th century. The first treatises on Hebrew grammar appeared in the High Middle Ages, in the context of Mishnah (exegesis of the Hebrew Bible). The Karaite tradition originated in Abbasid Baghdad. The Diqduq (10th century) is one of the earliest grammatical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.[11] Ibn Barun in the 12th century, compares the Hebrew language with Arabic in the Islamic grammatical tradition.[12]

Belonging to the trivium of the seven liberal arts, grammar was taught as a core discipline throughout the Middle Ages, following the influence of authors from Late Antiquity, such as Priscian. Treatment of vernaculars began gradually during the High Middle Ages, with isolated works such as the First Grammatical Treatise, but became influential only in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In 1486, Antonio de Nebrija published Las introduciones Latinas contrapuesto el romance al Latin, and the first Spanish grammar, Gramática de la lengua castellana, in 1492. During the 16th-century Italian Renaissance, the Questione della lingua was the discussion on the status and ideal form of the Italian language, initiated by Dante’s de vulgari eloquentia (Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua Venice 1525). The first grammar of Slovene was written in 1583 by Adam Bohorič.

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism and Bible translation from the 16th century onward, such as Grammatica o Arte de la Lengua General de Los Indios de Los Reynos del Perú (1560), a Quechua grammar by Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás.

From the latter part of the 18th century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. The Deutsche Grammatik of the Jacob Grimm was first published in the 1810s. The Comparative Grammar of Franz Bopp, the starting point of modern comparative linguistics, came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks[edit]

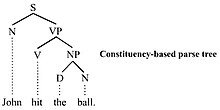

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object. This is in contrast to structural and functional grammar which consider the subject and object as equal constituents.[13][14]

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed in theoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar: dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière 1959)

- Link grammar

- Functional grammar (structural–functional analysis):

- Danish Functionalism

- Functional Discourse Grammar

- Role and reference grammar

- Systemic functional grammar

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate «universal grammar», an idea developed by Noam Chomsky. In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar / Cognitive linguistics

- Construction grammar

- Fluid Construction Grammar

- Word grammar

- Construction grammar

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar (1960s)

- Generative semantics (1970s) and Semantic Syntax (1990s)

- Phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (1985)

- Principles and parameters grammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar (lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar: probabilistic

- Operator grammar

Parse trees are commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar[edit]

Grammars evolve through usage. Historically, with the advent of written representations, formal rules about language usage tend to appear also, although such rules tend to describe writing conventions more accurately than conventions of speech.[15] Formal grammars are codifications of usage which are developed by repeated documentation and observation over time. As rules are established and developed, the prescriptive concept of grammatical correctness can arise. This often produces a discrepancy between contemporary usage and that which has been accepted, over time, as being standard or «correct». Linguists tend to view prescriptive grammar as having little justification beyond their authors’ aesthetic tastes, although style guides may give useful advice about standard language employment based on descriptions of usage in contemporary writings of the same language. Linguistic prescriptions also form part of the explanation for variation in speech, particularly variation in the speech of an individual speaker (for example, why some speakers say «I didn’t do nothing», some say «I didn’t do anything», and some say one or the other depending on social context).

The formal study of grammar is an important part of children’s schooling from a young age through advanced learning, though the rules taught in schools are not a «grammar» in the sense that most linguists use, particularly as they are prescriptive in intent rather than descriptive.

Constructed languages (also called planned languages or conlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalistic Interlingua, schematic Esperanto, and the highly logic-compatible artificial language Lojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Syntax refers to the linguistic structure above the word level (for example, how sentences are formed) – though without taking into account intonation, which is the domain of phonology. Morphology, by contrast, refers to the structure at and below the word level (for example, how compound words are formed), but above the level of individual sounds, which, like intonation, are in the domain of phonology.[16] However, no clear line can be drawn between syntax and morphology. Analytic languages use syntax to convey information that is encoded by inflection in synthetic languages. In other words, word order is not significant, and morphology is highly significant in a purely synthetic language, whereas morphology is not significant and syntax is highly significant in an analytic language. For example, Chinese and Afrikaans are highly analytic, thus meaning is very context-dependent. (Both have some inflections, and both have had more in the past; thus, they are becoming even less synthetic and more «purely» analytic over time.) Latin, which is highly synthetic, uses affixes and inflections to convey the same information that Chinese does with syntax. Because Latin words are quite (though not totally) self-contained, an intelligible Latin sentence can be made from elements that are arranged almost arbitrarily. Latin has a complex affixation and simple syntax, whereas Chinese has the opposite.

Education[edit]

Prescriptive grammar is taught in primary and secondary school. The term «grammar school» historically referred to a school (attached to a cathedral or monastery) that teaches Latin grammar to future priests and monks. It originally referred to a school that taught students how to read, scan, interpret, and declaim Greek and Latin poets (including Homer, Virgil, Euripides, and others). These should not be mistaken for the related, albeit distinct, modern British grammar schools.

A standard language is a dialect that is promoted above other dialects in writing, education, and, broadly speaking, in the public sphere; it contrasts with vernacular dialects, which may be the objects of study in academic, descriptive linguistics but which are rarely taught prescriptively. The standardized «first language» taught in primary education may be subject to political controversy because it may sometimes establish a standard defining nationality or ethnicity.

Recently, efforts have begun to update grammar instruction in primary and secondary education. The main focus has been to prevent the use of outdated prescriptive rules in favor of setting norms based on earlier descriptive research and to change perceptions about the relative «correctness» of prescribed standard forms in comparison to non-standard dialects. A series of metastudies have found that the explicit teaching of grammatical parts of speech and syntax has little or no effect on the improvement of student writing quality in elementary school, middle school of high school; other methods of writing instruction had far greater positive effect, including strategy instruction, collaborative writing, summary writing, process instruction, sentence combining and inquiry projects.[17][18][19]

The preeminence of Parisian French has reigned largely unchallenged throughout the history of modern French literature. Standard Italian is based on the speech of Florence rather than the capital because of its influence on early literature. Likewise, standard Spanish is not based on the speech of Madrid but on that of educated speakers from more northern areas such as Castile and León (see Gramática de la lengua castellana). In Argentina and Uruguay the Spanish standard is based on the local dialects of Buenos Aires and Montevideo (Rioplatense Spanish). Portuguese has, for now, two official standards, respectively Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese.

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian is likewise divided; Serbia and the Republika Srpska of Bosnia and Herzegovina use their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences in yat reflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy, some treat Montenegrin as a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

Norwegian has two standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk, the choice between which is subject to controversy: Each Norwegian municipality can either declare one as its official language or it can remain «language neutral». Nynorsk is backed by 27 percent of municipalities. The main language used in primary schools, chosen by referendum within the local school district, normally follows the official language of its municipality. Standard German emerged from the standardized chancellery use of High German in the 16th and 17th centuries. Until about 1800, it was almost exclusively a written language, but now it is so widely spoken that most of the former German dialects are nearly extinct.

Standard Chinese has official status as the standard spoken form of the Chinese language in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Republic of China (ROC), and the Republic of Singapore. Pronunciation of Standard Chinese is based on the local accent of Mandarin Chinese from Luanping, Chengde in Hebei Province near Beijing, while grammar and syntax are based on modern vernacular written Chinese.

Modern Standard Arabic is directly based on Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. The Hindustani language has two standards, Hindi and Urdu.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated 4 March as National Grammar Day in 2008.[20]

See also[edit]

- Ambiguous grammar

- Constraint-based grammar

- Grammeme

- Harmonic Grammar

- Higher order grammar (HOG)

- Linguistic error

- Linguistic typology

- Paragrammatism

- Speech error (slip of the tongue)

- Usage (language)

- Usus

Notes[edit]

- ^ Traditionally, the mental information used to produce and process linguistic utterances is referred to as «rules». However, other frameworks employ different terminology, with theoretical implications. Optimality theory, for example, talks in terms of «constraints», while construction grammar, cognitive grammar, and other «usage-based» theories make reference to patterns, constructions, and «schemata»

- ^ O’Grady, William; Dobrovolsky, Michael; Katamba, Francis (1996). Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 4–7, 464–539. ISBN 978-0-582-24691-1. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Holmes, Janet (2001). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (second ed.). Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 73–94. ISBN 978-0-582-32861-7. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.; for more discussion of sets of grammars as populations, see: Croft, William (2000). Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 13–20. ISBN 978-0-582-35677-1. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 2002, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, p. 627f.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (23 September 2007). «The Power of Prepositions». On Writing. Cairo: Criminal Brief. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Jeremy Butterfield, (2008). Damp Squid: The English Language Laid Bare, Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-957409-4. p. 142.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «Grammar». Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī («Eight Chapters»), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ^ McGregor, William B. (2015). Linguistics: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-567-58352-9.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-300-09721-4. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ G. Khan, J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (2000)

- ^ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn’s Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ^ Schäfer, Roland (2016). Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen (2nd ed.). Berlin: Language Science Press. ISBN 978-1-537504-95-7. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Butler, Christopher S. (2003). Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (PDF). John Benjamins. pp. 121–124. ISBN 9781588113580. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Carter, Ronald; McCarthy, Michael (2017). «Spoken Grammar: Where are We and Where are We Going?». Applied Linguistics. 38: 1–20. doi:10.1093/applin/amu080.

- ^ Gussenhoven, Carlos; Jacobs, Haike (2005). Understanding Phonology (second ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-80735-4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

- ^ Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 879–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029185

- ^ «National Grammar Day». Quick and Dirty Tips. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

References[edit]

- Rundle, Bede. Grammar in Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-19-824612-9.

External links[edit]

Look up grammar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Grammar from the Oxford English Dictionary

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). «Grammar» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grammar.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Grammar.

Grammar as a Part of Language as a Linguistic Discipline.

Просмотров: 16333

Grammar as a Part of Language as a Linguistic Discipline.

√ Parts of Grammar;

√ Syntagmatic Paradigmatic Relations;

√ Grammatical Meaning Form.

Parts of Grammar.

According to de Sosur we should differentiate between language & speech. Language is an abstract system of signs or sets of roots (grammatical, syntactic, etc.), which makes the basis of all speaking. Speech — manifestation, of language, «language in use». Where does grammar belong to? To language.

Other parts of language are phonetics & lexicology. It’s true that different parts of language are interconnected & interrelated. One & the same idea can be expressed by different means of language e.g. negation

I don’t like = / hate

The ties between lexicology & grammar are of primary importance because grammatical & lexicological meanings are interdependent. From the course of Normative Grammar we know that certain grammatical functions are possible only for the words whose lexical meaning makes them fit to fulfill these functions.

You need special lexical meaning to make the verb function as a link-verb and part of part of a predicate, e.g. come true, turn red. There is also the reverse case when the grammatical form affects the lexical meaning of a word. e.g. to go, I’m going.

It also happens in a language rather often that a form which was originally grammatical becomes lexicolized. e.g. an iron , iron , irons (окопы); colour — соluors(стяги).

There are also cases of survival of two grammatically equivalent forms of one & the same word. The language keeps them because they acquire different lexical meaning.

They usually call them «etymological synonyms», e.g. brothers, brethren. The ties between lexicology & grammar are particularly strong in a sphere of a word-formation.

What are the main objects of grammatical studies? — A’ word & a sentence. We also single out morphology as a branch of grammar which studies morphemes & structure of words & the rules of word-changing. Combinations of words into groups or sentences are treated under syntax. It’s not always easy to differentiate between them.

Syntagmatic and Paradigmatic Relations.

Every word may be used in a sentence. It can be analyzed from this point of view. e.g.

I read a book & I’m reading a book. We have an action performed by the doer of the action & we can analyze the relations in which the words stand within the sentence.

On the other hand we can analyze the same word «read» as part of system including all other forms of the same word. When we analyze the relations of this particular jform to other forms we analyze the paradigmatic relations, within the sentence — syntagmatic relations.

How many levels are there in Grammar? Are they objective or subjective?

A word may be divided into morphemes, sentence — into phrases, etc!’

Phoneme — phonology;

phonetics — sounds

Morpheme — morphology

Word — grammar,

lexicology,

word-formation, lexicography

Phrase — syntax

Sentence — syntax

Utterance (text, discourse) — syntax

The levels are objective since the units of these levels exist objectively.

So grammatical units enter into two types of relations in the language system :

paradigmatic relations in language & syntagmatic in speech. The system of all grammatical means of one given class constitutes a paradigm.

There is a new approach to the division of grammar into morphology & syntax. According to it morphology should study both paradigmatic & syntagmatic relations of words.

Correspondingly syntax should study both paradigmatic & syntagmatic relations of sentences.

Grammatical Meaning Form.

The basic notions of Grammar are grammatical meaning, form, category. Jhe grammatical meaning is a general abstract meaning, which embraces classes of words in a language.

Grammatical meaning depends on lexical & is connected with objective reality indirectly through the lexical meaning. The grammatical meaning is relative revealed in relations of word-forms. The grammatical meaning is

obligatory it must be expressed if the speaker wants to be understood.

The grammatical meaning must have a grammatical form of expression(inflexions or analytical form or word order)

The term «form» may be used in a wide sense to denote all means of expressing grammatical meaning. It may be also used in a narrow sense to denote means of expressing a particular grammar meaning e.g. plural form, present tense, etc.

Grammatical elements are unities of meaning & form, content & expression. In the language system there is no direct correspondence between meaning & form.

Two or more units of the plane of content may correspond to one unit of the plane of expression (polysemy & homonymy) & two or more units of the plane of expression may correspond to one unit of the plane of content (synonymy).

System is a unity of homogeneous elements. Structure — unity of heterogeneous elements, which make up in their turn the units of higher hierarchy.

In the system of language grammatical elements are connected on the basis of similarity & contrast. Partially similar elements that are having common & distinctive features constitute oppositions (write — wrote, sky — skies, best — worst). Let’s take » pencil — pencils«.

Members of this opposition differ in form & have different grammatical meanings. At the same time they express the same general meaning — number. And this gives us the chance to formulate: the unity of general meaning & its particular manifestation, which is revealed through the oppositions of forms, is a grammatical category.

There may be different definitions of category laying stress either on its notional or formal aspect. But the category exists only if there is an opposition of at least two forms, if one — there is no category.

The minimal or two-member opposition is called binary. Oppositions may be of three main types:

I. Privative (отрицательный).

One member has a certain distinctive feature. This member is called «marked (strong)”. The other is characterized by the absence of this distinctive feature. It’s called “unmarked (weak)” (e.g. speak — speaks).

II. Equipollent (равноценный).

Both members of the opposition are marked (e.g. am — is).

III. Gradual.

Members of the opposition differ by the degree of certain property (e.g. good — better — best)

Most grammatical oppositions are privative. The marked (strong) member has a narrow & definite meaning. The unmarked (weak) member has a wide general meaning.Grammatical forms express meanings of different categories. The form «goes» denotes Present Tense, 3-d person, singular.

Active voice. Indicative mood. These meanings are revealed in different oppositions.

| goes |

is going will be gone went will be going |

But grammatical forms cannot express different meanings of the same category. In certain contexts the difference between members of the opposition is lost.

The opposition is reduced to one member. Usually the weak member acquires the meaning of the strong member (e.g. He leave for Paris tomorrow). This kind of oppositional reduction is called neutralization.

On the other hand the strong member may be used in the context typical for the weak member. Usually this use is stylistically marked e.g.

She is always complaining of her neighbors.

This kind of reduction is called transposition.

Grammatical categories reflect phenomena of objective reality.

The category of number in nouns reflects the essential properties of noun reference. Such categories can ( be called «notional» or «referential»).

Other categories reflect peculiarities of grammatical structure of the language (e.g. number in verbs in English). Such categories may be called «formal» or «relation».’

Besides grammatical or inflectional categories based on the oppositions of forms there are categories based on the oppositions of classes of words.

Such categories are called «lexico-grammatical» or «selective». The formal difference between members of a lexico-grammatical opposition is shown syntagmatically e.g. большой стол.

Grammatical categories may be influenced by the lexical meaning. Such categories as number, case, voice strongly depend on the lexica] meaning. They are proper to certain subclasses of words.

Thus, only objective verbs have the voice opposition, subjective verbs have only one form — that of the weak member of opposition.

Other categories as tense, mood are more abstract. They cover all words of a class.

As grammatical categories reflect relations existing in objective reality, different languages may have the same categories but the system & character of grammatical categories are determined by the grammatical structure of a given language.

Synthetical vs Analytical Forms.

The verb in synthetical form presents an inseparable unity of form & meaning. This unity can’t be broken without the destruction of the word. We have different ways to create synthetical forms in the language. The first one is affixation. Many affixes are polysemantic.

Another device is sound interchange. The third way is suppletivity. The number of morphemes used to derive new forms in the English is rather small.

Many of them are polysemantic. In sound interchange changes take place in frames of one root & suppletive formation involves different roots.

Analytical grammatical forms are those presented by words of full lexical meaning So some formal auxiliary words, which are free (or devoid) of any lexical meaning. This combination functions in the language as the grammatical form of one word e.g. is being written.

But the grammatical meaning of analytical form is not equivalent to the grammatical meaning of the auxiliary verb; it is distributed between auxiliary & the verb-form (or the ending of the verb- form). There are four criteria to establish the difference between the analytical grammatical forms & the free syntactic word combinations:

1. The existence of one purely grammatical element

2. The distribution of the total grammatical meaning between this purely grammatical auxiliary & grammatical ending of the main form.

3. Concentration of the lexical meaning only in one word.

4. The existence of simple synthetical form in the paradigm.

From the structural point of view it is a combination of words which are united according to certain syntactic rales but functionally it is only a form of a certain verb. In other words they are phrases in form & word-forms in function.

The Morphemic Analysis for English Words.

Morphemes, Morphs & Attomorphs.

Morpheme is the smallest meaningful part of a word. It can be free or bound. A word consisting of a single morpheme — monomorphemic, opposite — polymorphic. In terms of structuralism according to Bloomfield“ a word is a minimum free form».

Morphemes are commonly classified into suffixes, prefixes, infixes. According to their meaning & function they can also be subdivided into lexical (roots) lexico-grammatical (word-building affixes) & grammatical or form-building affixes (inflexions).

Morphemes are abstract units represented in speech by morphs or аllomorphs. Most morphemes are realised by single morphemes e.g. un/self/ish. Some morphemes can be manifested by more than one morph according to their position.

Such alternative morphs or positional variants of a morpheme are called allomorphs. Morphemic variants are identified in the text on the basis of their со-occurrence with other morphs or their environment. The total of environments constitutes the distribution.

There may be three types of morphemic distribution: contrastive, non- contrastive & complimentary.

Morphs are in contrastive distribution „ if their position is the same & their meanings are different, g. charming vs charmed).

Morphs are in non-contrastive distribution if their position is the same & their meanings are the same (e.g. learned vs learnt). Such morphs constitute free variants of the same morpheme.

Morphs are in complimentary distribution if their positions are different & their meanings are the same. Such morphs are allomorphs of the same 1 morpheme (e.g. -tion or -sion).

Grammatical meanings may be expressed by the absence of the morpheme (e.g. book- books). The meaning of plurality is expressed by the morpheme «-s», singularity -by the absence of the morpheme.

Such meaningful absence of the morpheme is called zero-morpheme. The function of the morpheme may be performed by a separate word. In the opposition «play — will play» the meaning of the future is expressed by the word «will».

«Will» is a contradictory unit, formally it is a word, functionally — it is a morpheme. As it has the features of a word & a morpheme it is called «a word-morpheme».

Word-morphemes may be called semibound morphemes. Means of form-building & grammatical forms are divided into synthetic & analytical.

Synthetic forms are built with the help of bound-morphemes. All analytical forms are built with the help of semi-bound morphemes.

Synthetic means of form-building are affixation, sound interchange (inner flexion), suppletivity. Typical features of English affixation are ’scarcity & homonymy.

Another characteristic feature is a great number of zero-morphemes.Though English grammatical affixes are few in number, affixation is a productive means of form-building.

Sound interchange may be of two types: vowel & consonant. It is often accompanied by affixation (e.g. bring — brought). Sound interchange is not productive now, but it is used to build the forms of irregular verbs.

Prefixes modify the lexical meaning of the word while suffixes not only change the meaning but also change the form often shifting the word from one part of speech to another.

Sometimes the basic & the resulted forms belong tо the same class of words. In this case we say that a suffix serves to differentiate between subclasses within the same part of speech.

But even a prefix may modify the meaning of word (e.g. to stay — outstay). We have only one infix in English (e.g. stand- stood). In the course of historic development the boundaries between the morphemes may change & in this case words change morphologically.

The main factors of this process: were described by Bogoroditskiy:

Simplification (e.g. Good-bye = God be with you

Decomposition (e.g. dazy = eye of the day)

If a word consists of one root-morpheme it is called a root-word. One root-morpheme + affix constitute a derived word (a derivative e.g. a girl — girlish), two or more roots constitute a compound word (e.g. girl — friend), two or more roots + affix constitute compound derivative (e.g. all-the-madish).

Parts of Speech. Principles of Classification of the Parts of Speech.

Гости не могут комментировать

Grammar Definition

In general, when defining Grammar, it is important to start by saying that this discipline is an inseparable part of Linguistics, a science dedicated to the study of language, at each of its levels: Phonetic-Phonological; Syntactic-morphological, lexical-semantic and pragmatic. Consequently, grammar will be conceived as the linguistic discipline, which is responsible for studying, describing and in some cases even promulgating (in the case of prescriptive grammar) the different rules by which a language is handled, as well as the different rules and relationships that are established between words and sentences, so it can be said then that the vast majority of Grammar develops at the syntactic-morphological level of the Language, even when there are sources that They say that this point is not so precise when one thinks for example that within the Grammar there are rules of concern directly to the phonetic-phonological level.

Grammar Descriptive Role

Despite what most speakers think, Linguistics – and thus its different disciplines, including Grammar – does not produce or promulgate the rules by which the Language works, which are decided by the speakers themselves, unconsciously , intangible, collective and through the multiple generations that make up a speech community, but are simply responsible for observing, studying and recording the use that community makes of the Language. However, as in a linguistic community there are hundreds of ways to perform the Language, Grammar for example chooses to look at the model language of that community, registering then the ideal way in which that language conceives itself, that is, the total norms, forms, uses and relationships of the different grammatical categories and other syntactic constituents. Hence – although there is a prescriptive grammar – the Grammar is generally assumed as a descriptive discipline.

Etymology of the word Grammar

With respect to the etymology of the word Grammar, the different theoretical sources coincide in indicating that this word has its origin in the Latin word grammatĭca, which in turn can be traced to a Greek voice of form γραμματικῆ τέχνη ( grammatikḗ tékhne ) denomination compound, whose meanings would be related to the following:

From Greece, the term grammatikḗ tékhne passed into the Latin language, where it assumed the grammatĭca form . However, during the third century BC by the famous Latin grammarian Elio Donato, a new order was established, since the reading and interpretation of texts, included for the Greeks also in the conception of grammatikḗ tékhne became seen as a branch own, which was called literature (word that comes in turn from the word littera , which can also be translated as letter) while they chose to keep the word grammatĭca, to name the compendium of rules by which the language was governed, meaning with which, in part, it has remained until today.

Types of Grammar

Grammar Types

However, even though Grammar is a great branch of Linguistics that addresses the study of the relations and norms by which a Language is governed, within it you can also find different approaches or ways of approaching the subject of study, hence they also talk about different types of grammar, each of which will then be defined according to the position and conception they have about the language they study . Here is a brief definition of each of them:

Prescriptive grammar

This type of Grammar, also known as normative Grammar, responds perhaps to one of the first approaches that Grammar had, so this discipline is linked to an important traditional sense. As their names indicate, this Grammar aims to study the different rules by which a Language is governed, only instead of observing those that exist, it is responsible for erecting a series of rules and parameters, thereby building a Model language , which is assumed as the ideal that should be pursued by all speakers, either in their oral record, and especially in their written record. Therefore, prescriptive grammar assumes the role of dictating norms on the correct use of the language.

Despite the great presence it had for centuries, nowadays Linguistics considers it an approach to grammar, while pointing out that the norms and conception of the language that prescriptive grammar has gives a partial account of a single level of speech , related to the cultured or academic language, which only a few speakers approach, so it cannot be said that prescriptive grammar actually reports a complete record of the language studied. However, it is still the grammar that everyone who wants to learn the language will study, assuming that she realizes the most standard form of it.

Descriptive grammar

Contrary to the prescriptive grammar, the grammar of descriptive approach has been gaining in linguistics, in recent times. This can be defined as a discipline that approaches a Language, with the purpose of being able to study, observe, identify and register the different norms by which that Language is governed, and that have been conceived naturally by a linguistic community. In this way, the descriptive grammar records these norms and syntactic relations of a language, as well as the use and category of every word used by this community, realizing it, that is, instead of pretending to regulate a language, it describes how it It is regulated.

Traditional grammar

This type of grammar is closely linked to the prescriptive grammar, as well as the conception that it has about the language and its own function of regulating it. In this sense, traditional Grammar receives this name because it is considered part of an academic heritage that could be traced to the very conception that the ancient Greeks had about language. Perhaps because of this, it remains the grammar taught in basic education, in order to convey to the speaker what are the principles by which the language of the linguistic community to which it belongs belongs. Consequently, its approach remains prescriptive, as well as partial, as it takes into account only the Model or standard language.

Functional grammar

On the other hand, Linguistics also calls attention to the so-called Functional Grammar, whose conception is attributed to the Dutch linguist Simon C. Dik, for whom the Language, in addition to social creation, was a social instrument in itself. Therefore, Dik raised in his theory the possibility of studying a language through the observation and recording of the different uses made by speakers of linguistic expressions, typical of his community, hence he receives the name of functional grammar, since his main subject of study will be the functions that perform each of the words and sentences within a language, then studying them as a social instrument. Likewise, functional grammar also assumes that the language is governed by three standards of adequacy: Typological, Pragmatic and Psychological.

Generative Grammar

Regarding the Generative Grammar, the different sources coincide in pointing out the linguist Noam Chomsky as the father of this theory, which focuses on the study of the syntax of a Language, starting from the beginning of power – through the study of syntactic relationships – predict possible combinations of words that form a sentence, considered grammatically acceptable (correct). In this way, through the knowledge of the syntax, the nature of the sentences of a language can be known, as well as the processes and relationships that will intervene in the formation of new sentences. The objective of this type of Grammar will also be to be able to promulgate a series of rules, which can tell the speaker how the different sentences in the Language are generated.

Formal grammar

Finally, within the different types of Grammar, there are the formal Grammatics, which could be understood as those mathematical structures that account for the norms and rules that come into play when generating a string of characters,expressly indicating which are admissible and which are not, within the Logic that the formal Language or Grammar admits. Although these formal languages are common to disciplines such as Logic or Mathematics, they can also be found within Computational Linguistics, as well as within the theoretical Linguistics itself. Regarding its approach, formal grammar would focus on describing the form taken by the different well-formed formulas that comprise it, without being interested in describing their meaning, hence receiving the name of formal grammar.

What is Grammar in English?

Grammar can be defined as the specific set of rules which helps us to arrange the words in the sentences to form a proper meaning.

It can also be defined as the structure and system of a language in which it usually consists of Morphology and syntaxes.

Every language has its own grammar and usually, English grammar has its own set of rules to organize the words in the sentences.

So after learning grammar, you can use, classify and structure the words together to form reasonable written and spoken communication.

Types of Grammar in the English Language

There are 9 different types of Grammars which are available in the English Language. Those are,

- Descriptive Grammar

- Prescriptive Grammar

- Comparative Grammar

- Generative Grammar

- Mental Grammar

- Performance Grammar

- Traditional Grammar

- Transformational Grammar

- Universal Grammar

Descriptive Grammar

Descriptive Grammar refers to the language structure. This type of grammar is mostly used by speakers and writers.

The descriptive Grammar can be defined as, “the set of rules of language based on how it is used actually. There is no right or wrong in the Descriptive Grammar.

Prescriptive Grammar

Prescriptive grammar also refers to the language structure (same as descriptive) but the only difference is that it is based on how the language should be used.

In this type of grammar, right and wrong language is also there. So, these rules are actually a standard set of rules of the grammar.

Comparative Grammar

Comparative Grammar is defined as a branch of linguistics in which the comparison and analysis of grammar structures of the language are considered.

Comparitive grammar is also known as Comparitive Philology.

Also Read: 12 Rules of Grammar | (Grammar Basic Rules with examples)

Generative Grammar

Generative grammar is a part of linguistic theory and it is one of the most influential. It is usually defined as a set of rules that describes the structure of the native speaker’s language.

It includes the study of the sound pattern (which is called as Phonology), morphology, semantics and syntaxes.

Mental Grammar

Mental Grammar (also called as Competence grammar & linguistic competence) is the Generative grammar which is stored in the human brain, that allows the person (speaker) to produce the language which can be understood by another person.

This concept was successfully proposed by the American Linguist Noam Chomsky with one of his work called “Syntactic Structures”.

Performance Grammar

The concept of Performance Grammar was used by Noam Chomsky in the year 1960. It is actually used to indicate the actual usage of the language in concrete situations.

So, it is used to describe both comprehension and production of the language.

Traditional Grammar

The set of rules which describes the structures of the language in which it is usually taught in schools are known as Traditional Grammar.

Generally, traditional grammar is prescriptive because it focuses on the distinction between what people thought to do with the language (structure) and what are actually doing.

Transformational Grammar

It is the theory of grammar that focuses on the construction of language by phrase and linguistic structures.

Transformational grammar is also known as TGG (Transformational – generative – grammar).

Universal Grammar

The system of categories, operations and principles shared by all languages are considered to be innate.

Quiz Time! (Test your knowledge here)

#1. _________ grammar is mostly used by writers and speakers.

Comparative

Comparative

Generative

Generative

Universal

Universal

Descriptive

Descriptive

Answer: Descriptive grammar is mostly used by writers and speakers.

#2. Grammar is a set of _______.

rules

rules

words

words

sentences

sentences

corrections

corrections

Answer: Grammar is a set of rules.

#3. Every language has its own grammar. Is it true or false?

can’t say

can’t say

true

true

false

false

none

none

#4. Transformational Grammar is also known as __________.

TGG (Traditional – generative – grammar)

TGG (Traditional – generative – grammar)

TGG (Transformational – generative – grammar)

TGG (Transformational – generative – grammar)

VGG (Verbal – generative – grammar)

VGG (Verbal – generative – grammar)

SGG (Structural – generative – grammar)

SGG (Structural – generative – grammar)

Answer: Transformational Grammar is also known as TGG (Transformational – generative – grammar).

#5. _________ grammar has a set of rules that describes the structure of the native speaker’s language.

Transformational

Transformational

Universal

Universal

Generative

Generative

Performance

Performance

Answer: Generative grammar has a set of rules that describes the structure of the native speaker’s language.

#6. Comparative Grammar consider ________________ for sentence structures in a language.

comparison and analysis

comparison and analysis

a set of rules

a set of rules

all of the mentioned

all of the mentioned

language structures

language structures

Answer: Comparative Grammar consider comparison and analysis for sentence structures in a language.

#7. Which type of grammar is usually taught in schools?

Universal Grammar

Universal Grammar

Prescriptive Grammar

Prescriptive Grammar

Descriptive Grammar

Descriptive Grammar

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar

Answer: Traditional Grammar is usually taught in schools.

#8. Competence grammar is also called as __________.

Mental Grammar

Mental Grammar

Universal Grammar

Universal Grammar

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar

Performance Grammar

Performance Grammar

Answer: Competence grammar is also called as Mental Grammar.

#9. The concept of Performance Grammar was used by Noam Chomsky in the year ________.

1960

1960

1965

1965

1970

1970

1978

1978

#10. Which of the following is not a type of grammar?

Descriptive Grammar

Descriptive Grammar

Prescriptive Grammar

Prescriptive Grammar

Comparative Grammar

Comparative Grammar

Informative Grammar

Informative Grammar

Answer: Informative Grammar

Results

—

Hurray….. You have passed this test! 🙂

Congratulations on completing the quiz. We are happy that you have understood this topic very well.

If you want to try again, you can start this quiz by refreshing this page.

Otherwise, you can visit the next topic 🙂

Oh, sorry about that. You didn’t pass this test! 🙁

Please read the topic carefully and try again.

Summary: (What is Grammar?)

- Grammar is a set of rules which explains the structure of the sentences by arranging the words in order to form a proper meaning.

Also Read: Noun Definition and Examples | Best English Guide 2021

If you are interested to learn more, then you can refer wikipedia from here.

I hope that you understood the topic “What is Grammar?”. If you have any doubts regarding this topic, then comment down below and we will respond to your questions as soon as possible. Thank You.