Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. «Nature» can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are part of nature, human activity is often understood as a separate category from other natural phenomena.[1]

The word nature is borrowed from the Old French nature and is derived from the Latin word natura, or «essential qualities, innate disposition», and in ancient times, literally meant «birth».[2] In ancient philosophy, natura is mostly used as the Latin translation of the Greek word physis (φύσις), which originally related to the intrinsic characteristics of plants, animals, and other features of the world to develop of their own accord.[3][4]

The concept of nature as a whole, the physical universe, is one of several expansions of the original notion;[1] it began with certain core applications of the word φύσις by pre-Socratic philosophers (though this word had a dynamic dimension then, especially for Heraclitus), and has steadily gained currency ever since.

During the advent of modern scientific method in the last several centuries, nature became the passive reality, organized and moved by divine laws.[5][6] With the Industrial revolution, nature increasingly became seen as the part of reality deprived from intentional intervention: it was hence considered as sacred by some traditions (Rousseau, American transcendentalism) or a mere decorum for divine providence or human history (Hegel, Marx). However, a vitalist vision of nature, closer to the pre-Socratic one, got reborn at the same time, especially after Charles Darwin.[1]

Within the various uses of the word today, «nature» often refers to geology and wildlife. Nature can refer to the general realm of living plants and animals, and in some cases to the processes associated with inanimate objects—the way that particular types of things exist and change of their own accord, such as the weather and geology of the Earth. It is often taken to mean the «natural environment» or wilderness—wild animals, rocks, forest, and in general those things that have not been substantially altered by human intervention, or which persist despite human intervention. For example, manufactured objects and human interaction generally are not considered part of nature, unless qualified as, for example, «human nature» or «the whole of nature». This more traditional concept of natural things that can still be found today implies a distinction between the natural and the artificial, with the artificial being understood as that which has been brought into being by a human consciousness or a human mind. Depending on the particular context, the term «natural» might also be distinguished from the unnatural or the supernatural.[1]

Earth

Earth is the only planet known to support life, and its natural features are the subject of many fields of scientific research. Within the Solar System, it is third closest to the Sun; it is the largest terrestrial planet and the fifth largest overall. Its most prominent climatic features are its two large polar regions, two relatively narrow temperate zones, and a wide equatorial tropical to subtropical region.[7] Precipitation varies widely with location, from several metres of water per year to less than a millimetre. 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by salt-water oceans. The remainder consists of continents and islands, with most of the inhabited land in the Northern Hemisphere.

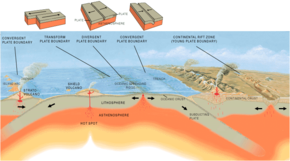

Earth has evolved through geological and biological processes that have left traces of the original conditions. The outer surface is divided into several gradually migrating tectonic plates. The interior remains active, with a thick layer of plastic mantle and an iron-filled core that generates a magnetic field. This iron core is composed of a solid inner phase, and a fluid outer phase. Convective motion in the core generates electric currents through dynamo action, and these, in turn, generate the geomagnetic field.

The atmospheric conditions have been significantly altered from the original conditions by the presence of life-forms,[8] which create an ecological balance that stabilizes the surface conditions. Despite the wide regional variations in climate by latitude and other geographic factors, the long-term average global climate is quite stable during interglacial periods,[9] and variations of a degree or two of average global temperature have historically had major effects on the ecological balance, and on the actual geography of the Earth.[10][11]

Geology

Geology is the science and study of the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth. The field of geology encompasses the study of the composition, structure, physical properties, dynamics, and history of Earth materials, and the processes by which they are formed, moved, and changed. The field is a major academic discipline, and is also important for mineral and hydrocarbon extraction, knowledge about and mitigation of natural hazards, some Geotechnical engineering fields, and understanding past climates and environments.

Geological evolution

The geology of an area evolves through time as rock units are deposited and inserted and deformational processes change their shapes and locations.

Rock units are first emplaced either by deposition onto the surface or intrude into the overlying rock. Deposition can occur when sediments settle onto the surface of the Earth and later lithify into sedimentary rock, or when as volcanic material such as volcanic ash or lava flows, blanket the surface. Igneous intrusions such as batholiths, laccoliths, dikes, and sills, push upwards into the overlying rock, and crystallize as they intrude.

After the initial sequence of rocks has been deposited, the rock units can be deformed and/or metamorphosed. Deformation typically occurs as a result of horizontal shortening, horizontal extension, or side-to-side (strike-slip) motion. These structural regimes broadly relate to convergent boundaries, divergent boundaries, and transform boundaries, respectively, between tectonic plates.

Historical perspective

An animation showing the movement of the continents from the separation of Pangaea until the present day

Earth is estimated to have formed 4.54 billion years ago from the solar nebula, along with the Sun and other planets.[12] The Moon formed roughly 20 million years later. Initially molten, the outer layer of the Earth cooled, resulting in the solid crust. Outgassing and volcanic activity produced the primordial atmosphere. Condensing water vapor, most or all of which came from ice delivered by comets, produced the oceans and other water sources.[13] The highly energetic chemistry is believed to have produced a self-replicating molecule around 4 billion years ago.[14]

Plankton inhabit oceans, seas and lakes, and have existed in various forms for at least 2 billion years[15]

Continents formed, then broke up and reformed as the surface of Earth reshaped over hundreds of millions of years, occasionally combining to make a supercontinent. Roughly 750 million years ago, the earliest known supercontinent Rodinia, began to break apart. The continents later recombined to form Pannotia which broke apart about 540 million years ago, then finally Pangaea, which broke apart about 180 million years ago.[16]

During the Neoproterozoic era, freezing temperatures covered much of the Earth in glaciers and ice sheets. This hypothesis has been termed the «Snowball Earth», and it is of particular interest as it precedes the Cambrian explosion in which multicellular life forms began to proliferate about 530–540 million years ago.[17]

Since the Cambrian explosion there have been five distinctly identifiable mass extinctions.[18] The last mass extinction occurred some 66 million years ago, when a meteorite collision probably triggered the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and other large reptiles, but spared small animals such as mammals. Over the past 66 million years, mammalian life diversified.[19]

Several million years ago, a species of small African ape gained the ability to stand upright.[15] The subsequent advent of human life, and the development of agriculture and further civilization allowed humans to affect the Earth more rapidly than any previous life form, affecting both the nature and quantity of other organisms as well as global climate. By comparison, the Great Oxygenation Event, produced by the proliferation of algae during the Siderian period, required about 300 million years to culminate.

The present era is classified as part of a mass extinction event, the Holocene extinction event, the fastest ever to have occurred.[20][21] Some, such as E. O. Wilson of Harvard University, predict that human destruction of the biosphere could cause the extinction of one-half of all species in the next 100 years.[22] The extent of the current extinction event is still being researched, debated and calculated by biologists.[23][24][25]

Atmosphere, climate, and weather

The Earth’s atmosphere is a key factor in sustaining the ecosystem. The thin layer of gases that envelops the Earth is held in place by gravity. Air is mostly nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, with much smaller amounts of carbon dioxide, argon, etc. The atmospheric pressure declines steadily with altitude. The ozone layer plays an important role in depleting the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation that reaches the surface. As DNA is readily damaged by UV light, this serves to protect life at the surface. The atmosphere also retains heat during the night, thereby reducing the daily temperature extremes.

Terrestrial weather occurs almost exclusively in the lower part of the atmosphere, and serves as a convective system for redistributing heat.[26] Ocean currents are another important factor in determining climate, particularly the major underwater thermohaline circulation which distributes heat energy from the equatorial oceans to the polar regions. These currents help to moderate the differences in temperature between winter and summer in the temperate zones. Also, without the redistributions of heat energy by the ocean currents and atmosphere, the tropics would be much hotter, and the polar regions much colder.

Weather can have both beneficial and harmful effects. Extremes in weather, such as tornadoes or hurricanes and cyclones, can expend large amounts of energy along their paths, and produce devastation. Surface vegetation has evolved a dependence on the seasonal variation of the weather, and sudden changes lasting only a few years can have a dramatic effect, both on the vegetation and on the animals which depend on its growth for their food.

Climate is a measure of the long-term trends in the weather. Various factors are known to influence the climate, including ocean currents, surface albedo, greenhouse gases, variations in the solar luminosity, and changes to the Earth’s orbit. Based on historical records, the Earth is known to have undergone drastic climate changes in the past, including ice ages.

The climate of a region depends on a number of factors, especially latitude. A latitudinal band of the surface with similar climatic attributes forms a climate region. There are a number of such regions, ranging from the tropical climate at the equator to the polar climate in the northern and southern extremes. Weather is also influenced by the seasons, which result from the Earth’s axis being tilted relative to its orbital plane. Thus, at any given time during the summer or winter, one part of the Earth is more directly exposed to the rays of the sun. This exposure alternates as the Earth revolves in its orbit. At any given time, regardless of season, the Northern and Southern Hemispheres experience opposite seasons.

Weather is a chaotic system that is readily modified by small changes to the environment, so accurate weather forecasting is limited to only a few days.[27] Overall, two things are happening worldwide: (1) temperature is increasing on the average; and (2) regional climates have been undergoing noticeable changes.[28]

Water on the Earth

Water is a chemical substance that is composed of hydrogen and oxygen (H2O) and is vital for all known forms of life.[29] In typical usage, water refers only to its liquid form or state, but the substance also has a solid state, ice, and a gaseous state, water vapor, or steam. Water covers 71% of the Earth’s surface.[30] On Earth, it is found mostly in oceans and other large bodies of water, with 1.6% of water below ground in aquifers and 0.001% in the air as vapor, clouds, and precipitation.[31][32] Oceans hold 97% of surface water, glaciers, and polar ice caps 2.4%, and other land surface water such as rivers, lakes, and ponds 0.6%. Additionally, a minute amount of the Earth’s water is contained within biological bodies and manufactured products.

Oceans

A view of the Atlantic Ocean from Leblon, Rio de Janeiro

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth’s surface (an area of some 361 million square kilometers) is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas. More than half of this area is over 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) deep. Average oceanic salinity is around 35 parts per thousand (ppt) (3.5%), and nearly all seawater has a salinity in the range of 30 to 38 ppt. Though generally recognized as several ‘separate’ oceans, these waters comprise one global, interconnected body of salt water often referred to as the World Ocean or global ocean.[33][34] This concept of a global ocean as a continuous body of water with relatively free interchange among its parts is of fundamental importance to oceanography.[35]

The major oceanic divisions are defined in part by the continents, various archipelagos, and other criteria: these divisions are (in descending order of size) the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and the Arctic Ocean. Smaller regions of the oceans are called seas, gulfs, bays and other names. There are also salt lakes, which are smaller bodies of landlocked saltwater that are not interconnected with the World Ocean. Two notable examples of salt lakes are the Aral Sea and the Great Salt Lake.

Lakes

Main article: Lake

A lake (from Latin word lacus) is a terrain feature (or physical feature), a body of liquid on the surface of a world that is localized to the bottom of basin (another type of landform or terrain feature; that is, it is not global) and moves slowly if it moves at all. On Earth, a body of water is considered a lake when it is inland, not part of the ocean, is larger and deeper than a pond, and is fed by a river.[36][37] The only world other than Earth known to harbor lakes is Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, which has lakes of ethane, most likely mixed with methane. It is not known if Titan’s lakes are fed by rivers, though Titan’s surface is carved by numerous river beds. Natural lakes on Earth are generally found in mountainous areas, rift zones, and areas with ongoing or recent glaciation. Other lakes are found in endorheic basins or along the courses of mature rivers. In some parts of the world, there are many lakes because of chaotic drainage patterns left over from the last ice age. All lakes are temporary over geologic time scales, as they will slowly fill in with sediments or spill out of the basin containing them.

Ponds

Main article: Pond

A pond is a body of standing water, either natural or man-made, that is usually smaller than a lake. A wide variety of man-made bodies of water are classified as ponds, including water gardens designed for aesthetic ornamentation, fish ponds designed for commercial fish breeding, and solar ponds designed to store thermal energy. Ponds and lakes are distinguished from streams via current speed. While currents in streams are easily observed, ponds and lakes possess thermally driven micro-currents and moderate wind driven currents. These features distinguish a pond from many other aquatic terrain features, such as stream pools and tide pools.

Rivers

A river is a natural watercourse,[38] usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, a lake, a sea or another river. In a few cases, a river simply flows into the ground or dries up completely before reaching another body of water. Small rivers may also be called by several other names, including stream, creek, brook, rivulet, and rill; there is no general rule that defines what can be called a river. Many names for small rivers are specific to geographic location; one example is Burn in Scotland and North-east England. Sometimes a river is said to be larger than a creek, but this is not always the case, due to vagueness in the language.[39] A river is part of the hydrological cycle. Water within a river is generally collected from precipitation through surface runoff, groundwater recharge, springs, and the release of stored water in natural ice and snowpacks (i.e., from glaciers).

Streams

A stream is a flowing body of water with a current, confined within a bed and stream banks. In the United States, a stream is classified as a watercourse less than 60 feet (18 metres) wide. Streams are important as conduits in the water cycle, instruments in groundwater recharge, and they serve as corridors for fish and wildlife migration. The biological habitat in the immediate vicinity of a stream is called a riparian zone. Given the status of the ongoing Holocene extinction, streams play an important corridor role in connecting fragmented habitats and thus in conserving biodiversity. The study of streams and waterways in general involves many branches of inter-disciplinary natural science and engineering, including hydrology, fluvial geomorphology, aquatic ecology, fish biology, riparian ecology, and others.

Ecosystems

Loch Lomond in Scotland forms a relatively isolated ecosystem. The fish community of this lake has remained unchanged over a very long period of time.[40]

Ecosystems are composed of a variety of biotic and abiotic components that function in an interrelated way.[41] The structure and composition is determined by various environmental factors that are interrelated. Variations of these factors will initiate dynamic modifications to the ecosystem. Some of the more important components are soil, atmosphere, radiation from the sun, water, and living organisms.

Central to the ecosystem concept is the idea that living organisms interact with every other element in their local environment. Eugene Odum, a founder of ecology, stated: «Any unit that includes all of the organisms (ie: the «community») in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity, and material cycles (i.e.: exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system is an ecosystem.»[42] Within the ecosystem, species are connected and dependent upon one another in the food chain, and exchange energy and matter between themselves as well as with their environment.[43] The human ecosystem concept is based on the human/nature dichotomy and the idea that all species are ecologically dependent on each other, as well as with the abiotic constituents of their biotope.[44]

A smaller unit of size is called a microecosystem. For example, a microsystem can be a stone and all the life under it. A macroecosystem might involve a whole ecoregion, with its drainage basin.[45]

Wilderness

Wilderness is generally defined as areas that have not been significantly modified by human activity. Wilderness areas can be found in preserves, estates, farms, conservation preserves, ranches, national forests, national parks, and even in urban areas along rivers, gulches, or otherwise undeveloped areas. Wilderness areas and protected parks are considered important for the survival of certain species, ecological studies, conservation, and solitude. Some nature writers believe wilderness areas are vital for the human spirit and creativity,[46] and some ecologists consider wilderness areas to be an integral part of the Earth’s self-sustaining natural ecosystem (the biosphere). They may also preserve historic genetic traits and that they provide habitat for wild flora and fauna that may be difficult or impossible to recreate in zoos, arboretums, or laboratories.

Life

Female mallard and ducklings – reproduction is essential for continuing life

Although there is no universal agreement on the definition of life, scientists generally accept that the biological manifestation of life is characterized by organization, metabolism, growth, adaptation, response to stimuli, and reproduction.[47] Life may also be said to be simply the characteristic state of organisms.

Properties common to terrestrial organisms (plants, animals, fungi, protists, archaea, and bacteria) are that they are cellular, carbon-and-water-based with complex organization, having a metabolism, a capacity to grow, respond to stimuli, and reproduce. An entity with these properties is generally considered life. However, not every definition of life considers all of these properties to be essential. Human-made analogs of life may also be considered to be life.

The biosphere is the part of Earth’s outer shell—including land, surface rocks, water, air and the atmosphere—within which life occurs, and which biotic processes in turn alter or transform. From the broadest geophysiological point of view, the biosphere is the global ecological system integrating all living beings and their relationships, including their interaction with the elements of the lithosphere (rocks), hydrosphere (water), and atmosphere (air). The entire Earth contains over 75 billion tons (150 trillion pounds or about 6.8×1013 kilograms) of biomass (life), which lives within various environments within the biosphere.[48]

Over nine-tenths of the total biomass on Earth is plant life, on which animal life depends very heavily for its existence.[49] More than 2 million species of plant and animal life have been identified to date,[50] and estimates of the actual number of existing species range from several million to well over 50 million.[51][52][53] The number of individual species of life is constantly in some degree of flux, with new species appearing and others ceasing to exist on a continual basis.[54][55] The total number of species is in rapid decline.[56][57][58]

Evolution

The origin of life on Earth is not well understood, but it is known to have occurred at least 3.5 billion years ago,[61][62][63] during the hadean or archean eons on a primordial Earth that had a substantially different environment than is found at present.[64] These life forms possessed the basic traits of self-replication and inheritable traits. Once life had appeared, the process of evolution by natural selection resulted in the development of ever-more diverse life forms.

Species that were unable to adapt to the changing environment and competition from other life forms became extinct. However, the fossil record retains evidence of many of these older species. Current fossil and DNA evidence shows that all existing species can trace a continual ancestry back to the first primitive life forms.[64]

When basic forms of plant life developed the process of photosynthesis the sun’s energy could be harvested to create conditions which allowed for more complex life forms.[65] The resultant oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere and gave rise to the ozone layer. The incorporation of smaller cells within larger ones resulted in the development of yet more complex cells called eukaryotes.[66] Cells within colonies became increasingly specialized, resulting in true multicellular organisms. With the ozone layer absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation, life colonized the surface of Earth.

Microbes

The first form of life to develop on the Earth were microbes, and they remained the only form of life until about a billion years ago when multi-cellular organisms began to appear.[67] Microorganisms are single-celled organisms that are generally microscopic, and smaller than the human eye can see. They include Bacteria, Fungi, Archaea, and Protista.

These life forms are found in almost every location on the Earth where there is liquid water, including in the Earth’s interior.[68]

Their reproduction is both rapid and profuse. The combination of a high mutation rate and a horizontal gene transfer[69] ability makes them highly adaptable, and able to survive in new environments, including outer space.[70] They form an essential part of the planetary ecosystem. However, some microorganisms are pathogenic and can post health risk to other organisms.

Plants and animals

Originally Aristotle divided all living things between plants, which generally do not move fast enough for humans to notice, and animals. In Linnaeus’ system, these became the kingdoms Vegetabilia (later Plantae) and Animalia. Since then, it has become clear that the Plantae as originally defined included several unrelated groups, and the fungi and several groups of algae were removed to new kingdoms. However, these are still often considered plants in many contexts. Bacterial life is sometimes included in flora,[71][72] and some classifications use the term bacterial flora separately from plant flora.

Among the many ways of classifying plants are by regional floras, which, depending on the purpose of study, can also include fossil flora, remnants

of plant life from a previous era. People in many regions and countries take great pride in their individual arrays of characteristic flora, which can vary widely across the globe due to differences in climate and terrain.

Regional floras commonly are divided into categories such as native flora and agricultural and garden flora, the lastly mentioned of which are intentionally grown and cultivated. Some types of «native flora» actually have been introduced centuries ago by people migrating from one region or continent to another, and become an integral part of the native, or natural flora of the place to which they were introduced. This is an example of how human interaction with nature can blur the boundary of what is considered nature.

Another category of plant has historically been carved out for weeds. Though the term has fallen into disfavor among botanists as a formal way to categorize «useless» plants, the informal use of the word «weeds» to describe those plants that are deemed worthy of elimination is illustrative of the general tendency of people and societies to seek to alter or shape the course of nature. Similarly, animals are often categorized in ways such as domestic, farm animals, wild animals, pests, etc. according to their relationship to human life.

Animals as a category have several characteristics that generally set them apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and usually multicellular (although see Myxozoa), which separates them from bacteria, archaea, and most protists. They are heterotrophic, generally digesting food in an internal chamber, which separates them from plants and algae. They are also distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls.

With a few exceptions—most notably the two phyla consisting of sponges and placozoans—animals have bodies that are differentiated into tissues. These include muscles, which are able to contract and control locomotion, and a nervous system, which sends and processes signals. There is also typically an internal digestive chamber. The eukaryotic cells possessed by all animals are surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins. This may be calcified to form structures like shells, bones, and spicules, a framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganized during development and maturation, and which supports the complex anatomy required for mobility.

Human interrelationship

Human impact

Although humans comprise only a minuscule proportion of the total living biomass on Earth, the human effect on nature is disproportionately large. Because of the extent of human influence, the boundaries between what humans regard as nature and «made environments» is not clear cut except at the extremes. Even at the extremes, the amount of natural environment that is free of discernible human influence is diminishing at an increasingly rapid pace. A 2020 study published in Nature found that anthropogenic mass (human-made materials) outweighs all living biomass on earth, with plastic alone exceeding the mass of all land and marine animals combined.[73] And according to a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, only about 3% of the planet’s terrestrial surface is ecologically and faunally intact, with a low human footprint and healthy populations of native animal species.[74][75]

The development of technology by the human race has allowed the greater exploitation of natural resources and has helped to alleviate some of the risk from natural hazards. In spite of this progress, however, the fate of human civilization remains closely linked to changes in the environment. There exists a highly complex feedback loop between the use of advanced technology and changes to the environment that are only slowly becoming understood.[76] Man-made threats to the Earth’s natural environment include pollution, deforestation, and disasters such as oil spills. Humans have contributed to the extinction of many plants and animals,[77] with roughly 1 million species threatened with extinction within decades.[78] The loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functions over the last half century have impacted the extent that nature can contribute to human quality of life,[79] and continued declines could pose a major threat to the continued existence of human civilization, unless a rapid course correction is made.[80] The value of natural resources to human society is not reflected in market prices because mostly natural resources are available free of charge. This distorts market pricing of natural resources and at the same time leads to underinvestment in our natural assets. The annual global cost of public subsidies that damage nature is conservatively estimated at $4–$6 trillion (million million). Institutional protections of these natural goods, such as the oceans and rainforests, are lacking. Governments have not prevented these economic externalities.[81][82]

Humans employ nature for both leisure and economic activities. The acquisition of natural resources for industrial use remains a sizable component of the world’s economic system.[83][84] Some activities, such as hunting and fishing, are used for both sustenance and leisure, often by different people. Agriculture was first adopted around the 9th millennium BCE. Ranging from food production to energy, nature influences economic wealth.

Although early humans gathered uncultivated plant materials for food and employed the medicinal properties of vegetation for healing,[85] most modern human use of plants is through agriculture. The clearance of large tracts of land for crop growth has led to a significant reduction in the amount available of forestation and wetlands, resulting in the loss of habitat for many plant and animal species as well as increased erosion.[86]

Aesthetics and beauty

Aesthetically pleasing flowers

Beauty in nature has historically been a prevalent theme in art and books, filling large sections of libraries and bookstores. That nature has been depicted and celebrated by so much art, photography, poetry, and other literature shows the strength with which many people associate nature and beauty. Reasons why this association exists, and what the association consists of, are studied by the branch of philosophy called aesthetics. Beyond certain basic characteristics that many philosophers agree about to explain what is seen as beautiful, the opinions are virtually endless.[87] Nature and wildness have been important subjects in various eras of world history. An early tradition of landscape art began in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). The tradition of representing nature as it is became one of the aims of Chinese painting and was a significant influence in Asian art.

Although natural wonders are celebrated in the Psalms and the Book of Job, wilderness portrayals in art became more prevalent in the 1800s, especially in the works of the Romantic movement. British artists John Constable and J. M. W. Turner turned their attention to capturing the beauty of the natural world in their paintings. Before that, paintings had been primarily of religious scenes or of human beings. William Wordsworth’s poetry described the wonder of the natural world, which had formerly been viewed as a threatening place. Increasingly the valuing of nature became an aspect of Western culture.[88] This artistic movement also coincided with the Transcendentalist movement in the Western world. A common classical idea of beautiful art involves the word mimesis, the imitation of nature. Also in the realm of ideas about beauty in nature is that the perfect is implied through perfect mathematical forms and more generally by patterns in nature. As David Rothenburg writes, «The beautiful is the root of science and the goal of art, the highest possibility that humanity can ever hope to see».[89]: 281

Matter and energy

Some fields of science see nature as matter in motion, obeying certain laws of nature which science seeks to understand. For this reason the most fundamental science is generally understood to be «physics»—the name for which is still recognizable as meaning that it is the «study of nature«.

Matter is commonly defined as the substance of which physical objects are composed. It constitutes the observable universe. The visible components of the universe are now believed to compose only 4.9 percent of the total mass. The remainder is believed to consist of 26.8 percent cold dark matter and 68.3 percent dark energy.[90] The exact arrangement of these components is still unknown and is under intensive investigation by physicists.

The behaviour of matter and energy throughout the observable universe appears to follow well-defined physical laws. These laws have been employed to produce cosmological models that successfully explain the structure and the evolution of the universe we can observe. The mathematical expressions of the laws of physics employ a set of twenty physical constants[91] that appear to be static across the observable universe.[92] The values of these constants have been carefully measured, but the reason for their specific values remains a mystery.

Beyond Earth

Outer space, also simply called space, refers to the relatively empty regions of the Universe outside the atmospheres of celestial bodies. Outer space is used to distinguish it from airspace (and terrestrial locations). There is no discrete boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and space, as the atmosphere gradually attenuates with increasing altitude. Outer space within the Solar System is called interplanetary space, which passes over into interstellar space at what is known as the heliopause.

Outer space is sparsely filled with several dozen types of organic molecules discovered to date by microwave spectroscopy, blackbody radiation left over from the Big Bang and the origin of the universe, and cosmic rays, which include ionized atomic nuclei and various subatomic particles. There is also some gas, plasma and dust, and small meteors. Additionally, there are signs of human life in outer space today, such as material left over from previous crewed and uncrewed launches which are a potential hazard to spacecraft. Some of this debris re-enters the atmosphere periodically.

Although Earth is the only body within the Solar System known to support life, evidence suggests that in the distant past the planet Mars possessed bodies of liquid water on the surface.[93] For a brief period in Mars’ history, it may have also been capable of forming life. At present though, most of the water remaining on Mars is frozen.

If life exists at all on Mars, it is most likely to be located underground where liquid water can still exist.[94]

Conditions on the other terrestrial planets, Mercury and Venus, appear to be too harsh to support life as we know it. But it has been conjectured that Europa, the fourth-largest moon of Jupiter, may possess a sub-surface ocean of liquid water and could potentially host life.[95]

Astronomers have started to discover extrasolar Earth analogs – planets that lie in the habitable zone of space surrounding a star, and therefore could possibly host life as we know it.[96]

See also

- Force of nature

- Human nature

- Natural history

- Naturalism

- Natural landscape

- Natural law

- Natural resource

- Natural science

- Natural theology

- Nature reserve

- Nature versus nurture

- Nature worship

- Naturism

- Rewilding

Media:

- National Wildlife, a publication of the National Wildlife Federation

- Natural History, by Pliny the Elder

- Natural World (TV series)

- Nature, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Nature, a prominent scientific journal

- Nature (TV series)

- The World We Live In (Life magazine)

Organizations:

- Nature Detectives

- The Nature Conservancy

Philosophy:

- Balance of nature (biological fallacy), a discredited concept of natural equilibrium in predator–prey dynamics

- Mother Nature

- Naturalism, any of several philosophical stances, typically those descended from materialism and pragmatism that do not distinguish the supernatural from nature;[97] this includes the methodological naturalism of natural science, which makes the methodological assumption that observable events in nature are explained only by natural causes, without assuming either the existence or non-existence of the supernatural

- Nature (philosophy)

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). «What does ‘nature’ mean?». Palgrave Communications. Springer Nature. 6 (14). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «nature». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ An account of the pre-Socratic use of the concept of φύσις may be found in Naddaf, Gerard (2006) The Greek Concept of Nature, SUNY Press, and in Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). «What does ‘nature’ mean?». Palgrave Communications. Springer Nature. 6 (14). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.. The word φύσις, while first used in connection with a plant in Homer, occurs early in Greek philosophy, and in several senses. Generally, these senses match rather well the current senses in which the English word nature is used, as confirmed by Guthrie, W.K.C. Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus (volume 2 of his History of Greek Philosophy), Cambridge UP, 1965.

- ^ The first known use of physis was by Homer in reference to the intrinsic qualities of a plant: ὣς ἄρα φωνήσας πόρε φάρμακον ἀργεϊφόντης ἐκ γαίης ἐρύσας, καί μοι φύσιν αὐτοῦ ἔδειξε. (So saying, Argeiphontes [=Hermes] gave me the herb, drawing it from the ground, and showed me its nature.) Odyssey 10.302–03 (ed. A.T. Murray). (The word is dealt with thoroughly in Liddell and Scott’s Greek Lexicon Archived March 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.) For later but still very early Greek uses of the term, see earlier note.

- ^ Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), for example, is translated «Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy», and reflects the then-current use of the words «natural philosophy», akin to «systematic study of nature»

- ^ The etymology of the word «physical» shows its use as a synonym for «natural» in about the mid-15th century: Harper, Douglas. «physical». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ^

«World Climates». Blue Planet Biomes. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2006. - ^ «Calculations favor reducing atmosphere for early Earth». Science Daily. September 11, 2005. Archived from the original on August 30, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ «Past Climate Change». U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Hugh Anderson; Bernard Walter (March 28, 1997). «History of Climate Change». NASA. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Weart, Spencer (June 2006). «The Discovery of Global Warming». American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (1991). The Age of the Earth. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1569-0.

- ^

Morbidelli, A.; et al. (2000). «Source Regions and Time Scales for the Delivery of Water to Earth». Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 35 (6): 1309–20. Bibcode:2000M&PS…35.1309M. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2000.tb01518.x. - ^

«Earth’s Oldest Mineral Grains Suggest an Early Start for Life». NASA Astrobiology Institute. December 24, 2001. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved May 24, 2006. - ^ a b Margulis, Lynn; Dorian Sagan (1995). What is Life?. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81326-4.

- ^ Murphy, J.B.; R.D. Nance (2004). «How do supercontinents assemble?». American Scientist. 92 (4): 324. doi:10.1511/2004.4.324. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ Kirschvink, J.L. (1992). «Late Proterozoic Low-Latitude Global Glaciation: The Snowball Earth» (PDF). In J.W. Schopf; C. Klein (eds.). The Proterozoic Biosphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-521-36615-1.

- ^ Raup, David M.; J. John Sepkoski Jr. (March 1982). «Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record». Science. 215 (4539): 1501–03. Bibcode:1982Sci…215.1501R. doi:10.1126/science.215.4539.1501. PMID 17788674. S2CID 43002817.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Dorian Sagan (1995). What is Life?. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-684-81326-4.

- ^ Diamond J; Ashmole, N. P.; Purves, P. E. (1989). «The present, past and future of human-caused extinctions». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 325 (1228): 469–76, discussion 476–77. Bibcode:1989RSPTB.325..469D. doi:10.1098/rstb.1989.0100. PMID 2574887.

- ^ Novacek M; Cleland E (2001). «The current biodiversity extinction event: scenarios for mitigation and recovery». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (10): 5466–70. Bibcode:2001PNAS…98.5466N. doi:10.1073/pnas.091093698. PMC 33235. PMID 11344295.

- ^ Wick, Lucia; Möhl, Adrian (2006). «The mid-Holocene extinction of silver fir (Abies alba) in the Southern Alps: a consequence of forest fires? Palaeobotanical records and forest simulations» (PDF). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 15 (4): 435–44. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0051-0. S2CID 52953180. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ The Holocene Extinction Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Mass Extinctions Of The Phanerozoic Menu Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Patterns of Extinction Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Miller; Spoolman, Scott (September 28, 2007). Environmental Science: Problems, Connections and Solutions. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-38337-6.

- ^ Stern, Harvey; Davidson, Noel (May 25, 2015). «Trends in the skill of weather prediction at lead times of 1–14 days». Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 141 (692): 2726–36. Bibcode:2015QJRMS.141.2726S. doi:10.1002/qj.2559. S2CID 119942734.

- ^ «Tropical Ocean Warming Drives Recent Northern Hemisphere Climate Change». Science Daily. April 6, 2001. Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- ^ «Water for Life». Un.org. March 22, 2005. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ «World». CIA – World Fact Book. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Water Vapor in the Climate System, Special Report, American Geophysical Union, December 1995.

- ^ Vital Water. UNEP.

- ^ «Ocean Archived January 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine». The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2002. New York: Columbia University Press

- ^ «Distribution of land and water on the planet Archived May 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine». UN Atlas of the Oceans Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spilhaus, Athelstan F (1942). «Maps of the whole world ocean». Geographical Review. 32 (3): 431–35. doi:10.2307/210385. JSTOR 210385.

- ^

Britannica Online. «Lake (physical feature)». Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.[a Lake is] any relatively large body of slowly moving or standing water that occupies an inland basin of appreciable size. Definitions that precisely distinguish lakes, ponds, swamps, and even rivers and other bodies of nonoceanic water are not well established. It may be said, however, that rivers and streams are relatively fast moving; marshes and swamps contain relatively large quantities of grasses, trees, or shrubs; and ponds are relatively small in comparison to lakes. Geologically defined, lakes are temporary bodies of water.

- ^ «Lake Definition». Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ River {definition} Archived February 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine from Merriam-Webster. Accessed February 2010.

- ^ USGS – U.S. Geological Survey – FAQs Archived July 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, No. 17 What is the difference between mountain, hill, and peak; lake and pond; or river and creek?

- ^ Adams, C.E. (1994). «The fish community of Loch Lomond, Scotland: its history and rapidly changing status». Hydrobiologia. 290 (1–3): 91–102. doi:10.1007/BF00008956. S2CID 6894397. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Introduction to the Ecosystem Concept». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd Edition). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Odum, EP (1971) Fundamentals of ecology, 3rd edition, Saunders New York

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Organization of Life». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd edition). Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Khan, Firdos Alam (2011). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-2009-4.

- ^ Bailey, Robert G. (April 2004). «Identifying Ecoregion Boundaries» (PDF). Environmental Management. 34 (Supplement 1): S14–26. doi:10.1007/s00267-003-0163-6. PMID 15883869. S2CID 31998098. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2009.

- ^ Botkin, Daniel B. (2000) No Man’s Garden, Island Press, pp. 155–57, ISBN 1-55963-465-0.

- ^ «Definition of Life». California Academy of Sciences. 2006. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ The figure «about one-half of one percent» takes into account the following (See, e.g., Leckie, Stephen (1999). «How Meat-centred Eating Patterns Affect Food Security and the Environment». For hunger-proof cities: sustainable urban food systems. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. ISBN 978-0-88936-882-8. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010., which takes global average weight as 60 kg.), the total human biomass is the average weight multiplied by the current human population of approximately 6.5 billion (see, e.g., «World Population Information». U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 28, 2006.[permanent dead link]): Assuming 60–70 kg to be the average human mass (approximately 130–150 lb on the average), an approximation of total global human mass of between 390 billion (390×109) and 455 billion kg (between 845 billion and 975 billion lb, or about 423 million–488 million short tons). The total biomass of all kinds on earth is estimated to be in excess of 6.8 x 1013 kg (75 billion short tons). By these calculations, the portion of total biomass accounted for by humans would be very roughly 0.6%.

- ^ Sengbusch, Peter V. «The Flow of Energy in Ecosystems – Productivity, Food Chain, and Trophic Level». Botany online. University of Hamburg Department of Biology. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Species Diversity and Biodiversity». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd Edition). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ «How Many Species are There?». Extinction Web Page Class Notes. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ «Animal.» World Book Encyclopedia. 16 vols. Chicago: World Book, 2003. This source gives an estimate of from 2 to 50 million.

- ^ «Just How Many Species Are There, Anyway?». Science Daily. May 2003. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ Withers, Mark A.; et al. (1998). «Changing Patterns in the Number of Species in North American Floras». Land Use History of North America. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006. Website based on the contents of the book: Sisk, T.D., ed. (1998). Perspectives on the land use history of North America: a context for understanding our changing environment (Revised September 1999 ed.). U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division. USGS/BRD/BSR-1998-0003.

- ^ «Tropical Scientists Find Fewer Species Than Expected». Science Daily. April 2002. Archived from the original on August 30, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ Bunker, Daniel E.; et al. (November 2005). «Species Loss and Aboveground Carbon Storage in a Tropical Forest». Science. 310 (5750): 1029–31. Bibcode:2005Sci…310.1029B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.7559. doi:10.1126/science.1117682. PMID 16239439. S2CID 42696030.

- ^ Wilcox, Bruce A. (2006). «Amphibian Decline: More Support for Biocomplexity as a Research Paradigm». EcoHealth. 3 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1007/s10393-005-0013-5. S2CID 23011961.

- ^ Clarke, Robin; Robert Lamb; Dilys Roe Ward, eds. (2002). «Decline and loss of species». Global environment outlook 3: past, present and future perspectives. London; Sterling, VA: Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP. ISBN 978-92-807-2087-7.

- ^ «Why the Amazon Rainforest is So Rich in Species: News». Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. December 5, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ «Why The Amazon Rainforest Is So Rich in Species». Sciencedaily.com. December 5, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (2007). «Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils». Precambrian Research. 158 (3–4): 141–155. Bibcode:2007PreR..158..141S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009.

- ^ Schopf, JW (2006). «Fossil evidence of Archaean life». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 361 (1470): 869–85. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- ^ Raven, Peter Hamilton; Johnson, George Brooks (2002). Biology. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Line, M. (January 1, 2002). «The enigma of the origin of life and its timing». Microbiology. 148 (Pt 1): 21–27. doi:10.1099/00221287-148-1-21. PMID 11782495.

- ^ «Photosynthesis more ancient than thought, and most living things could do it». Phys.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Berkner, L. V.; L. C. Marshall (May 1965). «On the Origin and Rise of Oxygen Concentration in the Earth’s Atmosphere». Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 22 (3): 225–61. Bibcode:1965JAtS…22..225B. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1965)022<0225:OTOARO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Schopf J (1994). «Disparate rates, differing fates: tempo and mode of evolution changed from the Precambrian to the Phanerozoic». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91 (15): 6735–42. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.6735S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6735. PMC 44277. PMID 8041691.

- ^ Szewzyk U; Szewzyk R; Stenström T (1994). «Thermophilic, anaerobic bacteria isolated from a deep borehole in granite in Sweden». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91 (5): 1810–13. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.1810S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1810. PMC 43253. PMID 11607462.

- ^ Wolska K (2003). «Horizontal DNA transfer between bacteria in the environment». Acta Microbiol Pol. 52 (3): 233–43. PMID 14743976.

- ^ Horneck G (1981). «Survival of microorganisms in space: a review». Adv Space Res. 1 (14): 39–48. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(81)90241-6. PMID 11541716.

- ^ «flora». Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on April 30, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ «Glossary». Status and Trends of the Nation’s Biological Resources. Reston, VA: Department of the Interior, Geological Survey. 1998. SuDocs No. I 19.202:ST 1/V.1-2. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007.

- ^ Elhacham, Emily; Ben-Uri, Liad; et al. (2020). «Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass». Nature. 588 (7838): 442–444. Bibcode:2020Natur.588..442E. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5. PMID 33299177. S2CID 228077506.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (April 15, 2021). «Just 3% of world’s ecosystems remain intact, study suggests». The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Plumptre, Andrew J.; Baisero, Daniele; et al. (2021). «Where Might We Find Ecologically Intact Communities?». Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 4. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2021.626635.

- ^ «Feedback Loops in Global Climate Change Point to a Very Hot 21st Century». Science Daily. May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805092998.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik (May 5, 2019). «Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature». Science. doi:10.1126/science.aax9287. S2CID 166478506.

- ^ Brauman, Kate A.; Garibaldi, Lucas A. (2020). «Global trends in nature’s contributions to people». PNAS. 117 (51): 32799–32805. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11732799B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2010473117. PMC 7768808. PMID 33288690.

- ^ Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Beattie, Andrew; Ceballos, Gerardo; Crist, Eileen; Diamond, Joan; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ehrlich, Anne H.; Harte, John; Harte, Mary Ellen; Pyke, Graham; Raven, Peter H.; Ripple, William J.; Saltré, Frédérik; Turnbull, Christine; Wackernagel, Mathis; Blumstein, Daniel T. (2021). «Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future». Frontiers in Conservation Science. 1. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419.

- ^ UK Government Official Documents, February 2021, «The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review Headline Messages» p. 2

- ^ Carrington, Damian (February 2, 2021). «Economics of biodiversity review: what are the recommendations?». The Guardian. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ «Natural Resources contribution to GDP». World Development Indicators (WDI). November 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014.

- ^ «GDP – Composition by Sector». The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ «Plant Conservation Alliance – Medicinal Plant Working Groups Green Medicine». US National Park Services. Archived from the original on October 9, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Oosthoek, Jan (1999). «Environmental History: Between Science & Philosophy». Environmental History Resources. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ^ «On the Beauty of Nature». The Wilderness Society. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ^ History of Conservation Archived July 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine BC Spaces for Nature. Accessed: May 20, 2006.

- ^ Rothenberg, David (2011). Survival of the Beautiful: Art, Science and Evolution. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-60819-216-8.

- ^ Ade, P. A. R.; Aghanim, N.; Armitage-Caplan, C.; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (March 22, 2013). «Planck 2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results – Table 9». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 571: A1. arXiv:1303.5062. Bibcode:2014A&A…571A…1P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321529. S2CID 218716838.

- ^ Taylor, Barry N. (1971). «Introduction to the constants for nonexperts». National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Varshalovich, D.A.; Potekhin, A.Y. & Ivanchik, A.V. (2000). «Testing cosmological variability of fundamental constants». AIP Conference Proceedings. 506: 503. arXiv:physics/0004062. Bibcode:2000AIPC..506..503V. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.43.6877. doi:10.1063/1.1302777.

- ^ Bibring, J; et al. (2006). «Global mineralogical and aqueous mars history derived from OMEGA/Mars Express data». Science. 312 (5772): 400–04. Bibcode:2006Sci…312..400B. doi:10.1126/science.1122659. PMID 16627738.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (March 8, 2005). «Hunt for Mars life should go underground». Space.com via NBC News. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ Turner, Scott (March 2, 1998). «Detailed Images From Europa Point To Slush Below Surface». NASA. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (March 21, 2011) New Estimate for Alien Earths: 2 Billion in Our Galaxy Alone | Alien Planets, Extraterrestrial Life & Extrasolar Planets | Exoplanets & Kepler Space Telescope Archived July 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Space.com.

- ^ Papineau, David (2016) «Naturalism», The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Archived April 1, 2019, at the Wayback Machine>

Further reading

- Droz, Layna; et al. (May 31, 2022). «Exploring the diversity of conceptualizations of nature in East and South-East Asia». Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 9 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01186-5. ISSN 2662-9992.

- Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). «What does ‘nature’ mean?». Palgrave Communications. Springer Nature. 6 (14). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.

- Emerson, Ralph W. (1836). Nature. Boston: James Munroe & Co.

- Farber, Paul Lawrence (2000), Finding Order in Nature: The Naturalist Tradition from Linnaeus to E. O. Wilson. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.

- Naddaf, Gerard (2006). The Greek Concept of Nature. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Piccolo, John J.; Taylor, Bron; Washington, Haydn; Kopnina, Helen; Gray, Joe; Alberro, Heather; Orlikowska, Ewa (2022). ««Nature’s contributions to people» and peoples’ moral obligations to nature». Biological Conservation. 270: 109572. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109572. S2CID 248769087.

- Worster, D. (1994). Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (iucnredlist.org)

- Ducarme, Frédéric (January 3, 2021). «What is nature?». Encyclopedia of the Environment.

Nature is a common notion, which everyone is familiar with as long as we are not asked to define it. This is normal: there is no consensus definition of it, and the term is rejected by most academic disciplines in both the sciences and the humanities. Yet it stays, and even better: it is eminently political – and even more so at a time when the idea of “protecting nature” is pressing. In this article, we attempt to unravel its mysteries, tracing its origin, its evolution and the succession of issues in which it has found itself in a central position. The aim is to identify the different realities it embraces, and the particular ways in which we relate to them in the era of global crises.

1. How do we define “nature”?

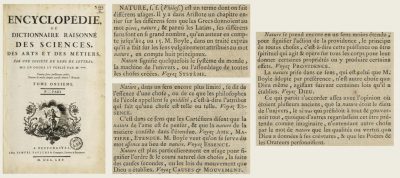

Few encyclopaedias have a “nature” article. The one written by Diderot and d’Alembert, in 1751, was already wary of “this rather vague term, often used, but seldom defined, which philosophers tend to use too much”, and Buffon, who was in charge of writing it, quickly abandoned the project. He was urgently replaced by d’Alembert and de Jaucourt, who only provided a timid catalogue of “its various meanings [which] are so numerous that one author can count as many as 14 or 15″ , an article consisting essentially of cross-references to terms deemed more satisfactory, albeit heterogeneous, such as “System of the world”, “Cause”, “Essence”, “Providence” and even “God” (Figure 1).

Even today, specialized encyclopaedias still seem to carefully avoid the concept of “nature”: this is for example the notable case of the Oxford Dictionary of Science (2005), but also of the Encyclopedia of environmental ethics and philosophy (2008). The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ecology and Environmental Sciences gives it three lines that do not say much, and the Dictionary of Ecological Thought (2015), for its part, takes the precaution of specifying its articles (“nature in philosophy”, “ordinary nature”), thus carefully circumventing the idea of nature itself – although this does not prevent its use in many articles. The same observation can be made on philosophers: nature does not stand among the “major notions of philosophy” in the main university textbooks, has never been on the syllabus of any French examination or competition, and one of the few textbooks to deal with it, André Lalande’s Vocabulaire technique et critique de la philosophie (regularly updated since 1902) imitates d’Alembert by recommending rigorous thinkers to avoid the use of this word, which can mean everything and its opposite. Moreover, the term is openly circumvented by many scientists, who prefer better defined and above all measurable hyponyms – because in the modern age there is no science without quantification – such as “biosphere”, “biodiversity”, “biocenosis”, “ecosystems” and other “physicalities” among anthropologists.

Thus, “nature” remained essentially a “casual” term in European languages, and has almost never been the subject of advanced academic theorization, except for the expression “human nature”, which had its moment of glory in the 18th century under the impetus of David Hume or Jean-Jacques Rousseau [1] (Figure 2).

Yet the ecological crisis has brought the idea of nature back to the forefront, and the word is now everywhere: this fact shows that it may not mean “nothing”, and that it is not really substitutable either. At a time when nature is said to be “in crisis”, when everyone would like to “protect” or even “act” on it, it is more imperative than ever to have a clear idea of this concept and its ramifications, which is what this article proposes to do [2].

2. Story of a mysterious word

Etymology is often an excellent way to shed light on the depth of a term; however, the term “nature” largely escapes this approach. The word is formed from the Latin verb nascor, which means “to get born”, here in a verbal form called supine, a form that can be used to construct the future participle (which does not seem to be the case here, at least no usage in this sense is known) or, like the other Latin words in -ure (culture, temperature) designates a way of being. Etymologically, it would therefore be the way in which one gets born, a kind of primordial character – which then excludes any absolute usage (effectively absent throughout the pre-classical period). In the Classical period, when young Romans from good families went to Greece to complete their intellectual education, this word was chosen to translate the Greek phusis, and became its standard translation. Phusis is one of the most complex concepts of Greek philosophy, both omnipresent (almost all the great works of the pre-Socratic philosophers are titled Peri phuseos, this concept appearing as the object of any scientific or philosophical enterprise), but with a meaning and usage that varies enormously from one author to another, or more precisely from one philosophical school to another. At the end of the apogee of Greece, Aristotle attempts a catalogue of these meanings, and lists four main ones [3]:

- generation of that which grows;

- the first immanent element from which growth proceeds;

- principle of the first movement for every natural being;

- and the primeval background from which any artificial object is made or comes from.

These four definitions could be roughly summarized as: growth, principle, power and substance. So here we are in the realm of physics – a term that is occasionally coined – and still far from biology and the environment. Greco-Roman nature does not yet designate a set of objects, but rather the dynamics that animate matter, whether living or not (the term is not often used in the Philosopher’s biology books).

It is in fact the Christianisation of Europe that will change the meaning of the word natura. Indeed, in the Christian cosmology (Figure 3), all dynamics can only come from God: it is him alone who creates the world and animates it, he is beyond nature and nothing is beyond him – whereas among the Greeks, the gods were subject to nature, they were still, in their own way, animals, animated by impulses, passions and needs. In the Abrahamic monotheisms, the whole of reality is now only a creation, a set of passive objects conceived and arranged by the demiurge, and from which only Mankind emerges, which is at once part of this creation but is called to transcend it. This hierarchy is an extremely original idea, which does not seem to be present in any other great civilizational basin: Mankind is then no longer completely a part of nature, and all the value of their existence lies in fact beyond nature, in the Kingdom of God. There is therefore no longer natura naturans, the creative principle which is a simple synonym of God, and natura naturata, which is his creation – knowing that the good Christian must despise earthly things [4], since it is through asceticism that one rises to God. The very word nature will thus become scarcely used in the Middle Ages, essentially returning to its etymological use.

It was not until the Renaissance that nature made a comeback in the European intellectual landscape, following the rediscovery of ancient texts, but without any real theorization of its meaning: nature is then seen either as the whole of creation (including Man or not), the set of physical forces that regulate the world (“natural laws”), or even a kind of abstract power of reality, sometimes allegorized in “Nature” with capital letters, a sort of earthly emissary of the divine will, even a feminine and benevolent counterpart of the Almighty Father (nature was already allegorized at the end of antiquity under the maternal figure of Isis, who was later secularized in the idea of “Mother Nature” [5]) (Figure 4). The fact that Plato, the meta-physician par excellence, does not seem to have been interested in this concept, which was too material, whereas philosophers gradually erected him during the classical age as the chief arbiter of what is or is not a philosophical concept, probably contributed later on to its scorn by most of the European academic tradition, and this until today.

3. Diversity of uses of the word

Despite this dislike of the academic world, “nature” remains the 419th most used word in the French language out of the 60,000 words listed in the usual dictionaries. It has undergone a number of one-off fashion effects, both during the Romantic period and with the cultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, in particular because of its fundamentally subversive nature, since the opposition between “nature” and “culture” makes it the perfect recourse when it comes to challenging the established order (“return to nature”) – even though “established order” is also precisely one of the meanings of “nature” [6]…

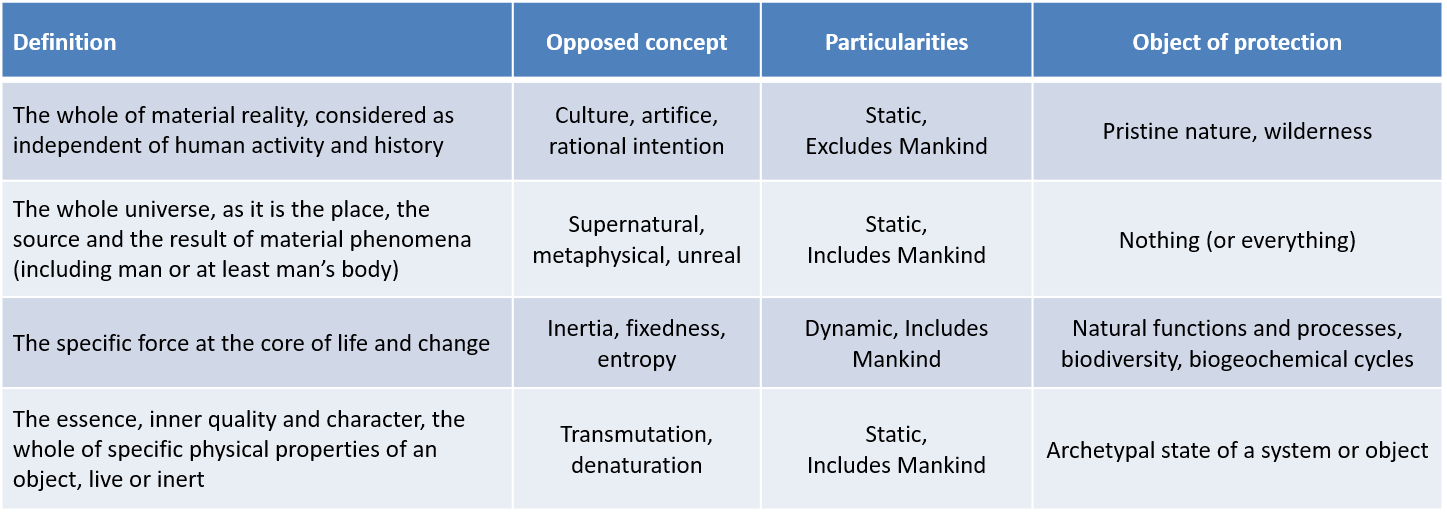

A study published in 2020 [7] attempted to review the meanings and uses of the word “nature”, based on a review of dictionaries, some of which have as many as 20 different and often contradictory definitions. All these ramifications seem to be summarized in four main ideas:

- The totality of material reality that does not result from human will (as opposed to artifice, intention and culture);

- The whole universe as a place, source and result of material phenomena, including man or at least his body (as opposed to the supernatural, the metaphysical or the unreal);

- The force at the principle of life and change (opposing inertia, fixity and entropy [8]);

- The essence, the set of specific physical properties and qualities of an object, living or inert (opposing denaturation).

These four definitions appear extremely heterogeneous in many aspects: some include humans while others explicitly exclude them, and some refer to objects and others to abstract phenomena or characters. They can therefore form the basis for radically different or even contradictory “conservations of nature” , and even, for some, make such an idea absurd: we have grouped these definitions and what they could represent in terms of conservation in Table 1.

4. What to protect?

As we have seen, nature is multiple: it follows that its protection is also crossed by several currents, which have added up rather than succeeded each other over time, at the rate of the emergence of new issues.

4.1. Protecting nature as a set of resources

Historically, human societies first protected natural “resources” (wood, game, “useful” animals and plants…) [9], “nature” itself being too abstract and too massive to be the object of direct human action. As early as the Mesolithic period, sedentary human groups began to save part of their resources to ensure their reproduction and permanence. This management was later entrusted to specialized corporations, such as in France the Administration of Water and Forests, created by Philippe le Bel in 1291, before being modernized by Colbert in 1669. In the US, it was Gifford Pinchot (trained at the Ecole de Nancy) who was the great protector of natural resources at the end of the 19th century, faced with the increasingly ferocious appetite of loggers (Figure 5).

4.2. Protecting nature as a living environment

With sedentarisation, came along ideas of health and safety. Indeed, human settlements attracted a whole host of commensal or parasitic species, not always desirable, both animal and plant, and even bacterial. The organization of the living environment has therefore rapidly become a necessity for all human societies, notably through the extirpation of a certain number of animals declared undesirable, often by means of exogenous domestic predators (dogs, cats, mustelids, viverrids, chickens, etc.), and then by using pesticides. This development came along with the anthropisation of the landscape, firstly through morphological (canals, terraces, flattening) and vegetal (fruit trees, ornamental trees, hedges) development. This new, comfortable living environment soon came as a standard of what nature should be, but a nature here cultivated and tamed, and radically opposed to wild nature, considered hostile and dangerous. This nature is thus resolutely a socio-ecosystem, a nature thought an environment for human activities to take place in, and goes largely against other conceptions of nature. It is this ideal that Latin pastoralists called locus amoenus, a kind of natural garden (Figure 6). This ideal is indeed also found in the history of gardening, landscaping and urban planning, particularly in the 19th century with the fashion for urban parks (Hyde Park was founded in 1820, Bois de Boulogne in 1852, Central Park in 1869). As this is an ideal, we can link it to the 4th definition of nature, that of a normative archetypal state.

The protection of this nice and aesthetic natural environment is known under the particular name of environmentalism, a term that contains its anthropocentric dimension very well, and which should be distinguished from ecologism. In fact, it is above all a question of protecting humans, first against wild nature and then rapidly against human nuisances themselves: it is in this respect that various regulations of these nuisances appeared, whether it be the creation of sewers and latrines in ancient times, then more important measures with the Industrial Revolution (Figure 7): in France, for example, the Imperial Decree of 15 October 1810 relating to “Manufactures and Workshops which spread an unhealthy or inconvenient odour“, and in England the creation in 1815 of the Commons Open Spaces & Footpaths preservation society. Most of the first environmental laws fall within this framework, and protect a very specific “nature”, which is domesticated nature seen as Mankind’s support – and is not necessarily less legitimate for all that.

4.3. Protecting nature as a set of monuments and landscapes

The idea of nature underwent a revolution in the 18th century: Westerners then finished mapping the entire planet, which suddenly seemed surprisingly small. At the same time, explorers gave an idea of the spatial distribution of the different species, making it possible to understand that some of them had indeed irretrievably disappeared, whereas until then one could always imagine residual populations (even for fossil species, Figure 8). One thus becomes aware that God does not seem to “re-create” his creations if Men destroy them, and the relationship with nature then changes abruptly with the first romantic generation: nature then passes from the mysterious mother of infinite abundance to the fragile battlefield of the human history.

It was thus in the 19th century and under the effect of the industrial revolution that the idea of “protecting nature” gradually germinated in the West – and this time it was mainly artists, intellectuals and writers who contributed to this movement, such as Charles Beauquier in France or John Muir in the United States. The fourth definition will essentially be used again: protection concerns the archetypal state of a site, which we will try to preserve as it is and make it a monument, under various administrative designations (national park, natural monument, classified site, etc.). It is therefore mainly spectacular landscapes and biological or geological features that are protected at that time, from the Yellowstone geysers (Figure 9) to the colonial hunting reserves, along with the Fontainebleau forest, which obtained protection in 1861 thanks to the naturalist painters of the Barbizon school, coined as an “artistic series”, since it was the last place around Paris where one could still admire very old trees. This “nature” is therefore essentially a landscape setting that will be protected, but this time not for direct use as a living environment, but for a rarer aesthetic and intellectual use. There is also the idea that these places must be protected from the defilement of civilization, joining for the occasion the first definition, which will be taken to extremes in America, where wilderness will be seen as an image of paradise precisely because it has remained as God created it, and not corrupted by the activity of men [10]. At the same time, the birth of nationalist currents will anchor this protection of the natural heritage in a particularly marked approach to identity [11]. The protection of emblematic species followed at the end of the 19th century in a very similar fashion.

4.4. Protecting nature as a set of ecosystems

It was not until the emergence of the ecosystem concept in 1935 that the vision of “nature” as a scientific object was renewed, first as a scientific object and then as an object of conservation. While the conservationist tradition was resolutely fixist and attached itself to inert or little changing objects (or at least treated as such), a more dynamic vision of nature was to develop under the impetus of Darwin, and restore the prestige of the third definition we have given. One of the guardian figures of this transition is the famous American forester Aldo Leopold, author of a posthumous work (A Sand County Almanac, 1949) considered as the “bible” of American ecology (Figure 10). Although Leopold was still unfamiliar with the term ecosystem, he nonetheless called for the active conservation of “biotic communities”, later (1992) renamed “biodiversity“. Leopold contributed to the creation of undeveloped forest reserves, protected not for aesthetic or touristic reasons but clearly for their biological and ecological importance, in contrast to the national parks, which until then had been almost all located in arid or mountainous areas.

This new protection of nature seen as a set of ecosystems is therefore based this time on essentially scientific criteria, such as biodiversity, endemism and ecological functionalities – leading to the christening of “ordinary nature” in conservation, since the major functions rely for a large part on the most abundant species [12]. Abstract notions of biological functions, material flows of matter (water, carbon, nitrogen) and energy will also come into play, and their importance for human societies will be embodied in 2005 by the concept of “ecosystem services“, popularized by the Millennium Ecosystems Assessment report commissioned by the UN in 2000. Nature is thus no longer inert and passive, and is becoming a platform for exchanges between biotic communities, of which humanity is one actor among others, powerful but also fragile and dependent.

4.5. Protecting nature as a set of conditions favourable to life as we know it