Not to be confused with pro-verb.

A proverb (from Latin: proverbium) is a simple and insightful, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and use formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbial expression is a type of a conventional saying similar to proverbs and transmitted by oral tradition. The difference is that a proverb is a fixed expression, while a proverbial phrase permits alterations to fit the grammar of the context.[1][2] Collectively, they form a genre of folklore.

Some proverbs exist in more than one language because people borrow them from languages and cultures with which they are in contact. In the West, the Bible (including, but not limited to the Book of Proverbs) and medieval Latin (aided by the work of Erasmus) have played a considerable role in distributing proverbs. Not all Biblical proverbs, however, were distributed to the same extent: one scholar has gathered evidence to show that cultures in which the Bible is the major spiritual book contain «between three hundred and five hundred proverbs that stem from the Bible,»[3] whereas another shows that, of the 106 most common and widespread proverbs across Europe, 11 are from the Bible.[4] However, almost every culture has its own unique proverbs.

Definitions[edit]

Lord John Russell (c. 1850) observed poetically that a «proverb is the wit of one, and the wisdom of many.»[5] But giving the word «proverb» the sort of definition theorists need has proven to be a difficult task, and although scholars often quote Archer Taylor’s argument that formulating a scientific «definition of a proverb is too difficult to repay the undertaking… An incommunicable quality tells us this sentence is proverbial and that one is not. Hence no definition will enable us to identify positively a sentence as proverbial,»[6] many students of proverbs have attempted to itemize their essential characteristics.

More constructively, Mieder has proposed the following definition, «A proverb is a short, generally known sentence of the folk which contains wisdom, truth, morals, and traditional views in a metaphorical, fixed, and memorizable form and which is handed down from generation to generation».[7] To distinguish proverbs from idioms, cliches, etc., Norrick created a table of distinctive features, an abstract tool originally developed for linguistics.[8] Prahlad distinguishes proverbs from some other, closely related types of sayings, «True proverbs must further be distinguished from other types of proverbial speech, e.g. proverbial phrases, Wellerisms, maxims, quotations, and proverbial comparisons.»[9] Based on Persian proverbs, Zolfaghari and Ameri propose the following definition: «A proverb is a short sentence, which is well-known and at times rhythmic, including advice, sage themes and ethnic experiences, comprising simile, metaphor or irony which is well-known among people for its fluent wording, clarity of expression, simplicity, expansiveness and generality and is used either with or without change.»[10]

There are many sayings in English that are commonly referred to as «proverbs», such as weather sayings. Alan Dundes, however, rejects including such sayings among truly proverbs: «Are weather proverbs proverbs? I would say emphatically ‘No!'»[11] The definition of «proverb» has also changed over the years. For example, the following was labeled «A Yorkshire proverb» in 1883, but would not be categorized as a proverb by most today, «as throng as Throp’s wife when she hanged herself with a dish-cloth».[12] The changing of the definition of «proverb» is also noted in Turkish.[13]

In other languages and cultures, the definition of «proverb» also differs from English. In the Chumburung language of Ghana, «aŋase are literal proverbs and akpare are metaphoric ones».[14] Among the Bini of Nigeria, there are three words that are used to translate «proverb»: ere, ivbe, and itan. The first relates to historical events, the second relates to current events, and the third was «linguistic ornamentation in formal discourse».[15] Among the Balochi of Pakistan and Afghanistan, there is a word batal for ordinary proverbs and bassīttuks for «proverbs with background stories».[16]

There are also language communities that combine proverbs and riddles in some sayings, leading some scholars to create the label «proverb riddles».[17][18][19]

Another similar construction is an idiomatic phrase. Sometimes it is difficult to draw a distinction between idiomatic phrase and proverbial expression. In both of them the meaning does not immediately follow from the phrase. The difference is that an idiomatic phrase involves figurative language in its components, while in a proverbial phrase the figurative meaning is the extension of its literal meaning. Some experts classify proverbs and proverbial phrases as types of idioms.[20]

Examples[edit]

«Pearls before Swine», Latin proverb on platter at the Louvre

- Haste makes waste

- A stitch in time saves nine

- Ignorance is bliss

- Mustn’t cry over spilled/spilt milk.

- Don’t cross the bridge until you come to it

- Those who live in glass houses should not throw stones.

- Fortune favours the bold

- Well begun is half done.

- A little learning is a dangerous thing

- A rolling stone gathers no moss.

- It ain’t over till the fat lady sings

- Garbage in, garbage out

- A poor workman blames his tools.

- A dog is a man’s best friend.

- An apple a day keeps the doctor away

- If the shoe fits, wear it!

- On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog

- Slow and steady wins the race

- Don’t count your chickens before they hatch

- Practice makes perfect.

- Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

- Your mileage may vary

- All that glitters is not gold

- You can’t have your cake and eat it

- With great power comes great responsibility

- The enemy of my enemy is my friend

Sources[edit]

«Who will bell the cat?», comes from the end of a story.

Proverbs come from a variety of sources.[21] Some are, indeed, the result of people pondering and crafting language, such as some by Confucius, Plato, Baltasar Gracián, etc. Others are taken from such diverse sources as poetry,[22] stories,[23] songs, commercials, advertisements, movies, literature, etc.[24] A number of the well known sayings of Jesus, Shakespeare, and others have become proverbs, though they were original at the time of their creation, and many of these sayings were not seen as proverbs when they were first coined. Many proverbs are also based on stories, often the end of a story. For example, the proverb «Who will bell the cat?» is from the end of a story about the mice planning how to be safe from the cat.[25]

Some authors have created proverbs in their writings, such as J.R.R. Tolkien,[26][27] and some of these proverbs have made their way into broader society. Similarly, C.S. Lewis’ created proverb about a lobster in a pot, from the Chronicles of Narnia, has also gained currency.[28] In cases like this, deliberately created proverbs for fictional societies have become proverbs in real societies. In a fictional story set in a real society, the movie Forrest Gump introduced «Life is like a box of chocolates» into broad society.[29] In at least one case, it appears that a proverb deliberately created by one writer has been naively picked up and used by another who assumed it to be an established Chinese proverb, Ford Madox Ford having picked up a proverb from Ernest Bramah, «It would be hypocrisy to seek for the person of the Sacred Emperor in a Low Tea House.»[30]

The proverb with «a longer history than any other recorded proverb in the world», going back to «around 1800 BC»[31] is in a Sumerian clay tablet, «The bitch by her acting too hastily brought forth the blind».[32][33] Though many proverbs are ancient, they were all newly created at some point by somebody. Sometimes it is easy to detect that a proverb is newly coined by a reference to something recent, such as the Haitian proverb «The fish that is being microwaved doesn’t fear the lightning».[34] Similarly, there is a recent Maltese proverb, wil-muturi, ferh u duluri «Women and motorcycles are joys and griefs»; the proverb is clearly new, but still formed as a traditional style couplet with rhyme.[35] Also, there is a proverb in the Kafa language of Ethiopia that refers to the forced military conscription of the 1980s, «…the one who hid himself lived to have children.»[36] A Mongolian proverb also shows evidence of recent origin, «A beggar who sits on gold; Foam rubber piled on edge.»[37] Another example of a proverb that is clearly recent is this from Sesotho: «A mistake goes with the printer.»[38] A political candidate in Kenya popularised a new proverb in his 1995 campaign, Chuth ber «Immediacy is best». «The proverb has since been used in other contexts to prompt quick action.»[39] Over 1,400 new English proverbs are said to have been coined and gained currency in the 20th century.[40]

This process of creating proverbs is always ongoing, so that possible new proverbs are being created constantly. Those sayings that are adopted and used by an adequate number of people become proverbs in that society.[41][42]

A rolling stone gathers no moss.

Interpretations[edit]

Interpreting proverbs is often complex, but is best done in a context.[43] Interpreting proverbs from other cultures is much more difficult than interpreting proverbs in one’s own culture. Even within English-speaking cultures, there is difference of opinion on how to interpret the proverb «A rolling stone gathers no moss.» Some see it as condemning a person that keeps moving, seeing moss as a positive thing, such as profit; others see the proverb as praising people that keep moving and developing, seeing moss as a negative thing, such as negative habits.[44]

Similarly, among Tajik speakers, the proverb «One hand cannot clap» has two significantly different interpretations. Most see the proverb as promoting teamwork. Others understand it to mean that an argument requires two people.[45] In an extreme example, one researcher working in Ghana found that for a single Akan proverb, twelve different interpretations were given.[46] Proverb interpretation is not automatic, even for people within a culture: Owomoyela tells of a Yoruba radio program that asked people to interpret an unfamiliar Yoruba proverb, «very few people could do so».[47] Siran found that people who had moved out of the traditional Vute-speaking area of Cameroon were not able to interpret Vute proverbs correctly, even though they still spoke Vute. Their interpretations tended to be literal.[48]

Children will sometimes interpret proverbs in a literal sense, not yet knowing how to understand the conventionalized metaphor. Interpretation of proverbs is also affected by injuries and diseases of the brain, «A hallmark of schizophrenia is impaired proverb interpretation.»[49]

Features[edit]

Grammatical structures[edit]

Proverbs in various languages are found with a wide variety of grammatical structures.[50] In English, for example, we find the following structures (in addition to others):

- Imperative, negative – Don’t beat a dead horse.

- Imperative, positive – If the shoe fits, wear it!

- Parallel phrases – Garbage in, garbage out.

- Rhetorical question – Is the Pope Catholic?

- Declarative sentence – Birds of a feather flock together.

However, people will often quote only a fraction of a proverb to invoke an entire proverb, e.g. «All is fair» instead of «All is fair in love and war», and «A rolling stone» for «A rolling stone gathers no moss.»

The grammar of proverbs is not always the typical grammar of the spoken language, often elements are moved around, to achieve rhyme or focus.[51]

Another type of grammatical construction is the wellerism, a speaker and a quotation, often with an unusual circumstance, such as the following, a representative of a wellerism proverb found in many languages: «The bride couldn’t dance; she said, ‘The room floor isn’t flat.'»[52]

Another type of grammatical structure in proverbs is a short dialogue:

- Shor/Khkas (SW Siberia): «They asked the camel, ‘Why is your neck crooked?’ The camel laughed roaringly, ‘What of me is straight?'»[53]

- Armenian: «They asked the wine, ‘Have you built or destroyed more?’ It said, ‘I do not know of building; of destroying I know a lot.'»[54]

- Bakgatla (a.k.a. Tswana): «The thukhui jackal said, ‘I can run fast.’ But the sands said, ‘We are wide.'» (Botswana)[55]

- Bamana: «‘Speech, what made you good?’ ‘The way I am,’ said Speech. ‘What made you bad?’ ‘The way I am,’ said Speech.» (Mali)[56]

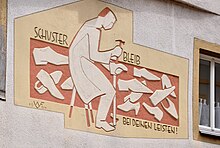

«The cobbler should stick to his last» in German. It is also an old proverb in English, but now «last» is no longer known to many.

Conservative language[edit]

Latin proverb overdoorway in Netherlands: «No one attacks me with impunity»

Because many proverbs are both poetic and traditional, they are often passed down in fixed forms. Though spoken language may change, many proverbs are often preserved in conservative, even archaic, form. «Proverbs often contain archaic… words and structures.»[57]In English, for example, «betwixt» is not commonly used, but a form of it is still heard (or read) in the proverb «There is many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip.» The conservative form preserves the meter and the rhyme. This conservative nature of proverbs can result in archaic words and grammatical structures being preserved in individual proverbs, as has been widely documented, e.g. in Amharic,[58] Greek,[59] Nsenga,[60] Polish,[61] Venda,[62] Hebrew,[63] Giriama,[64] Georgian,[65] Karachay-Balkar,[66] Hausa,[67] and Uzbek.[68]

In addition, proverbs may still be used in languages which were once more widely known in a society, but are now no longer so widely known. For example, English speakers use some non-English proverbs that are drawn from languages that used to be widely understood by the educated class, e.g. «C’est la vie» from French and «Carpe diem» from Latin.

Proverbs are often handed down through generations. Therefore, «many proverbs refer to old measurements, obscure professions, outdated weapons, unknown plants, animals, names, and various other traditional matters.»[69]

Therefore, it is common that they preserve words that become less common and archaic in broader society.[70][71] Archaic proverbs in solid form – such as murals, carvings, and glass – can be viewed even after the language of their form is no longer widely understood, such as an Anglo-French proverb in a stained glass window in York.[72]

Borrowing and spread[edit]

Proverbs are often and easily translated and transferred from one language into another. «There is nothing so uncertain as the derivation of proverbs, the same proverb being often found in all nations, and it is impossible to assign its paternity.»[73]

Proverbs are often borrowed across lines of language, religion, and even time. For example, a proverb of the approximate form «No flies enter a mouth that is shut» is currently found in Spain, France, Ethiopia, and many countries in between. It is embraced as a true local proverb in many places and should not be excluded in any collection of proverbs because it is shared by the neighbors. However, though it has gone through multiple languages and millennia, the proverb can be traced back to an ancient Babylonian proverb[74] Another example of a widely spread proverb is «A drowning person clutches at [frogs] foam», found in Peshai of Afghanistan[75] and Orma of Kenya,[76] and presumably places in between.

Proverbs about one hand clapping are common across Asia,[77] from Dari in Afghanistan[78] to Japan.[79] Some studies have been done devoted to the spread of proverbs in certain regions, such as India and her neighbors[80] and Europe.[81] An extreme example of the borrowing and spread of proverbs was the work done to create a corpus of proverbs for Esperanto, where all the proverbs were translated from other languages.[82]

It is often not possible to trace the direction of borrowing a proverb between languages. This is complicated by the fact that the borrowing may have been through plural languages. In some cases, it is possible to make a strong case for discerning the direction of the borrowing based on an artistic form of the proverb in one language, but a prosaic form in another language. For example, in Ethiopia there is a proverb «Of mothers and water, there is none evil.» It is found in Amharic, Alaaba language, and Oromo, three languages of Ethiopia:

- Oromo: Hadhaa fi bishaan, hamaa hin qaban.

- Amharic: Käənnatənna wəha, kəfu yälläm.

- Alaaba: Wiihaa ʔamaataa hiilu yoosebaʔa[83]

The Oromo version uses poetic features, such as the initial ha in both clauses with the final -aa in the same word, and both clauses ending with -an. Also, both clauses are built with the vowel a in the first and last words, but the vowel i in the one syllable central word. In contrast, the Amharic and Alaaba versions of the proverb show little evidence of sound-based art.

However, not all languages have proverbs. Proverbs are (nearly) universal across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Some languages in the Pacific have them, such as Maori.[84] Other Pacific languages do not, e.g. «there are no proverbs in Kilivila» of the Trobriand Islands.[85] However, in the New World, there are almost no proverbs: «While proverbs abound in the thousands in most cultures of the world, it remains a riddle why the Native Americans have hardly any proverb tradition at all.»[86] Hakamies has examined the matter of whether proverbs are found universally, a universal genre, concluding that they are not.[87]

Use[edit]

In conversation[edit]

Proverbs are used in conversation by adults more than children, partially because adults have learned more proverbs than children. Also, using proverbs well is a skill that is developed over years. Additionally, children have not mastered the patterns of metaphorical expression that are invoked in proverb use. Proverbs, because they are indirect, allow a speaker to disagree or give advice in a way that may be less offensive. Studying actual proverb use in conversation, however, is difficult since the researcher must wait for proverbs to happen.[88] An Ethiopian researcher, Tadesse Jaleta Jirata, made headway in such research by attending and taking notes at events where he knew proverbs were expected to be part of the conversations.[89]

In literature[edit]

Many authors have used proverbs in their writings, for a very wide variety of literary genres: epics,[90][91][92][93] novels,[94][95] poems,[96] short stories.[97]

Probably the most famous user of proverbs in novels is J. R. R. Tolkien in his The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series.[26][27][98][99] Herman Melville is noted for creating proverbs in Moby Dick[100] and in his poetry.[101][102] Also, C. S. Lewis created a dozen proverbs in The Horse and His Boy,[103] and Mercedes Lackey created dozens for her invented Shin’a’in and Tale’edras cultures;[104] Lackey’s proverbs are notable in that they are reminiscent to those of Ancient Asia – e.g. «Just because you feel certain an enemy is lurking behind every bush, it doesn’t follow that you are wrong» is like to «Before telling secrets on the road, look in the bushes.» These authors are notable for not only using proverbs as integral to the development of the characters and the story line, but also for creating proverbs.[103]

Among medieval literary texts, Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde plays a special role because Chaucer’s usage seems to challenge the truth value of proverbs by exposing their epistemological unreliability.[105] Rabelais used proverbs to write an entire chapter of Gargantua.[106]

The patterns of using proverbs in literature can change over time. A study of «classical Chinese novels» found proverb use as frequently as one proverb every 3,500 words in the Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan) and one proverb every 4,000 words in Wen Jou-hsiang. But modern Chinese novels have fewer proverbs by far.[107]

«Hercules and the Wagoner», illustration for children’s book

Proverbs (or portions of them) have been the inspiration for titles of books: The Bigger they Come by Erle Stanley Gardner, and Birds of a Feather (several books with this title), Devil in the Details (multiple books with this title). Sometimes a title alludes to a proverb, but does not actually quote much of it, such as The Gift Horse’s Mouth by Robert Campbell. Some books or stories have titles that are twisted proverbs, anti-proverbs, such as No use dying over spilled milk,[108] When life gives you lululemons,[109] and two books titled Blessed are the Cheesemakers.[110] The twisted proverb of last title was also used in the Monty Python movie Life of Brian, where a person mishears one of Jesus Christ’s beatitudes, «I think it was ‘Blessed are the cheesemakers.'»

Some books and stories are built around a proverb. Some of Tolkien’s books have been analyzed as having «governing proverbs» where «the acton of a book turns on or fulfills a proverbial saying.»[111] Some stories have been written with a proverb overtly as an opening, such as «A stitch in time saves nine» at the beginning of «Kitty’s Class Day», one of Louisa May Alcott’s Proverb Stories. Other times, a proverb appears at the end of a story, summing up a moral to the story, frequently found in Aesop’s Fables, such as «Heaven helps those who help themselves» from Hercules and the Wagoner.[112] In a novel by the Ivorian novelist Ahmadou Kourouma, «proverbs are used to conclude each chapter».[113]

Proverbs have also been used strategically by poets.[114] Sometimes proverbs (or portions of them or anti-proverbs) are used for titles, such as «A bird in the bush» by Lord Kennet and his stepson Peter Scott and «The blind leading the blind» by Lisa Mueller. Sometimes, multiple proverbs are important parts of poems, such as Paul Muldoon’s «Symposium», which begins «You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it hold its nose to the grindstone and hunt with the hounds. Every dog has a stitch in time…» In Finnish there are proverb poems written hundreds of years ago.[115] The Turkish poet Refiki wrote an entire poem by stringing proverbs together, which has been translated into English poetically yielding such verses as «Be watchful and be wary, / But seldom grant a boon; / The man who calls the piper / Will also call the tune.»[116] Eliza Griswold also created a poem by stringing proverbs together, Libyan proverbs translated into English.[117]

Because proverbs are familiar and often pointed, they have been used by a number of hip-hop poets. This has been true not only in the USA, birthplace of hip-hop, but also in Nigeria. Since Nigeria is so multilingual, hip-hop poets there use proverbs from various languages, mixing them in as it fits their need, sometimes translating the original. For example,

«They forget say ogbon ju agbaralo

They forget that wisdom is greater than power»[118]

Some authors have bent and twisted proverbs, creating anti-proverbs, for a variety of literary effects. For example, in the Harry Potter novels, J. K. Rowling reshapes a standard English proverb into «It’s no good crying over spilt potion» and Dumbledore advises Harry not to «count your owls before they are delivered».[119] In a slightly different use of reshaping proverbs, in the Aubrey–Maturin series of historical naval novels by Patrick O’Brian, Capt. Jack Aubrey humorously mangles and mis-splices proverbs, such as «Never count the bear’s skin before it is hatched» and «There’s a good deal to be said for making hay while the iron is hot.»[120] Earlier than O’Brian’s Aubrey, Beatrice Grimshaw also used repeated splicings of proverbs in the mouth of an eccentric marquis to create a memorable character in The Sorcerer’s Stone,[121] such as «The proof of the pudding sweeps clean» (p. 109) and «A stitch in time is as good as a mile» (p. 97).[122]

Because proverbs are so much a part of the language and culture, authors have sometimes used proverbs in historical fiction effectively, but anachronistically, before the proverb was actually known. For example, the novel Ramage and the Rebels, by Dudley Pope is set in approximately 1800. Captain Ramage reminds his adversary «You are supposed to know that it is dangerous to change horses in midstream» (p. 259), with another allusion to the same proverb three pages later. However, the proverb about changing horses in midstream is reliably dated to 1864, so the proverb could not have been known or used by a character from that period.[123]

Some authors have used so many proverbs that there have been entire books written cataloging their proverb usage, such as Charles Dickens,[124] Agatha Christie,[125] George Bernard Shaw,[126] Miguel de Cervantes,[127][128] and Friedrich Nietzsche.[129]

On the non-fiction side, proverbs have also been used by authors for articles that have no connection to the study of proverbs. Some have been used as the basis for book titles, e.g. I Shop, Therefore I Am: Compulsive Buying and the Search for Self by April Lane Benson. Some proverbs been used as the basis for article titles, though often in altered form: «All our eggs in a broken basket: How the Human Terrain System is undermining sustainable military cultural competence»[130] and «Should Rolling Stones Worry About Gathering Moss?»,[131] «Between a Rock and a Soft Place»,[132] and the pair «Verbs of a feather flock together»[133] and «Verbs of a feather flock together II».[134] Proverbs have been noted as common in subtitles of articles[135] such as «Discontinued intergenerational transmission of Czech in Texas: ‘Hindsight is better than foresight’.»[136] Also, the reverse is found with a proverb (complete or partial) as the title, then an explanatory subtitle, «To Change or Not to Change Horses: The World War II Elections».[137] Many authors have cited proverbs as epigrams at the beginning of their articles, e.g. «‘If you want to dismantle a hedge, remove one thorn at a time’ Somali proverb» in an article on peacemaking in Somalia.[138] An article about research among the Māori used a Māori proverb as a title, then began the article with the Māori form of the proverb as an epigram «Set the overgrown bush alight and the new flax shoots will spring up», followed by three paragraphs about how the proverb served as a metaphor for the research and the present context.[139] A British proverb has even been used as the title for a doctoral dissertation: Where there is muck there is brass.[140] Proverbs have also been used as a framework for an article.[141]

In drama and film[edit]

Similarly to other forms of literature, proverbs have also been used as important units of language in drama and films. This is true from the days of classical Greek works[142] to old French[143] to Shakespeare,[144] to 19th Century Spanish,[145] 19th century Russian,[146] to today. The use of proverbs in drama and film today is still found in languages around the world, with plenty of examples from Africa,[147] including Yorùbá[148][149] and Igbo[150][151] of Nigeria.

A film that makes rich use of proverbs is Forrest Gump, known for both using and creating proverbs.[152][153] Other studies of the use of proverbs in film include work by Kevin McKenna on the Russian film Aleksandr Nevsky,[154] Haase’s study of an adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood,[155] Elias Dominguez Barajas on the film Viva Zapata!,[156] and Aboneh Ashagrie on The Athlete (a movie in Amharic about Abebe Bikila).[157]

Television programs have also been named with reference to proverbs, usually shortened, such Birds of a Feather and Diff’rent Strokes.

In the case of Forrest Gump, the screenplay by Eric Roth had more proverbs than the novel by Winston Groom, but for The Harder They Come, the reverse is true, where the novel derived from the movie by Michael Thelwell has many more proverbs than the movie.[158]

Éric Rohmer, the French film director, directed a series of films, the «Comedies and Proverbs», where each film was based on a proverb: The Aviator’s Wife, The Perfect Marriage, Pauline at the Beach, Full Moon in Paris (the film’s proverb was invented by Rohmer himself: «The one who has two wives loses his soul, the one who has two houses loses his mind.»), The Green Ray, Boyfriends and Girlfriends.[159]

Movie titles based on proverbs include Murder Will Out (1939 film), Try, Try Again, and The Harder They Fall. A twisted anti-proverb was the title for a Three Stooges film, A Bird in the Head. The title of an award-winning Turkish film, Three Monkeys, also invokes a proverb, though the title does not fully quote it.

They have also been used as the titles of plays:[160] Baby with the Bathwater by Christopher Durang, Dog Eat Dog by Mary Gallagher, and The Dog in the Manger by Charles Hale Hoyt. The use of proverbs as titles for plays is not, of course, limited to English plays: Il faut qu’une porte soit ouverte ou fermée (A door must be open or closed) by Paul de Musset. Proverbs have also been used in musical dramas, such as The Full Monty, which has been shown to use proverbs in clever ways.[161] In the lyrics for Beauty and the Beast, Gaston plays with three proverbs in sequence, «All roads lead to…/The best things in life are…/All’s well that ends with…me.»

In music[edit]

Proverbs are often poetic in and of themselves, making them ideally suited for adapting into songs. Proverbs have been used in music from opera to country to hip-hop. Proverbs have also been used in music in many languages, such as the Akan language[162] the Igede language,[163] and Spanish.[164]

The Mighty Diamonds, singers of «Proverbs»

In English the proverb (or rather the beginning of the proverb), If the shoe fits has been used as a title for three albums and five songs. Other English examples of using proverbs in music[165] include Elvis Presley’s Easy come, easy go, Harold Robe’s Never swap horses when you’re crossing a stream, Arthur Gillespie’s Absence makes the heart grow fonder, Bob Dylan’s Like a rolling stone, Cher’s Apples don’t fall far from the tree. Lynn Anderson made famous a song full of proverbs, I never promised you a rose garden (written by Joe South). In choral music, we find Michael Torke’s Proverbs for female voice and ensemble. A number of Blues musicians have also used proverbs extensively.[166][167] The frequent use of proverbs in Country music has led to published studies of proverbs in this genre.[168][169] The Reggae artist Jahdan Blakkamoore has recorded a piece titled Proverbs Remix. The opera Maldobrìe contains careful use of proverbs.[170] An extreme example of many proverbs used in composing songs is a song consisting almost entirely of proverbs performed by Bruce Springsteen, «My best was never good enough».[171] The Mighty Diamonds recorded a song called simply «Proverbs».[172]

The band Fleet Foxes used the proverb painting Netherlandish Proverbs for the cover of their album Fleet Foxes.[173]

In addition to proverbs being used in songs themselves, some rock bands have used parts of proverbs as their names, such as the Rolling Stones, Bad Company, The Mothers of Invention, Feast or Famine, Of Mice and Men. There have been at least two groups that called themselves «The Proverbs», and there is a hip-hop performer in South Africa known as «Proverb». In addition, many albums have been named with allusions to proverbs, such as Spilt milk (a title used by Jellyfish and also Kristina Train), The more things change by Machine Head, Silk purse by Linda Ronstadt, Another day, another dollar by DJ Scream Roccett, The blind leading the naked by Violent Femmes, What’s good for the goose is good for the gander by Bobby Rush, Resistance is Futile by Steve Coleman, Murder will out by Fan the Fury. The proverb Feast or famine has been used as an album title by Chuck Ragan, Reef the Lost Cauze, Indiginus, and DaVinci. Whitehorse mixed two proverbs for the name of their album Leave no bridge unburned. The band Splinter Group released an album titled When in Rome, Eat Lions. The band Downcount used a proverb for the name of their tour, Come and take it.[174]

In visual form[edit]

Thai ceramic, illustrating «Don’t torch a stump with a hornet nest.»

From ancient times, people around the world have recorded proverbs in visual form. This has been done in two ways. First, proverbs have been written to be displayed, often in a decorative manner, such as on pottery, cross-stitch, murals,[175][176] kangas (East African women’s wraps),[177] quilts,[178] a stained glass window,[72] and graffiti.[179]

Secondly, proverbs have often been visually depicted in a variety of media, including paintings, etchings, and sculpture. Jakob Jordaens painted a plaque with a proverb about drunkenness above a drunk man wearing a crown, titled The King Drinks. Probably the most famous examples of depicting proverbs are the different versions of the paintings Netherlandish Proverbs by the father and son Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Pieter Brueghel the Younger, the proverbial meanings of these paintings being the subject of a 2004 conference, which led to a published volume of studies (Mieder 2004a). The same father and son also painted versions of The Blind Leading the Blind, a Biblical proverb. These and similar paintings inspired another famous painting depicting some proverbs and also idioms (leading to a series of additional paintings), such as Proverbidioms by T. E. Breitenbach. Another painting inspired by Bruegel’s work is by the Chinese artist, Ah To, who created a painting illustrating 81 Cantonese sayings.[180] Corey Barksdale has produced a book of paintings with specific proverbs and pithy quotations.[181][self-published source?] The British artist Chris Gollon has painted a major work entitled «Big Fish Eat Little Fish», a title echoing Bruegel’s painting Big Fishes Eat Little Fishes.[182]

Illustrations showing proverbs from Ben Franklin

Sometimes well-known proverbs are pictured on objects, without a text actually quoting the proverb, such as the three wise monkeys who remind us «Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil». When the proverb is well known, viewers are able to recognize the proverb and understand the image appropriately, but if viewers do not recognize the proverb, much of the effect of the image is lost. For example, there is a Japanese painting in the Bonsai museum in Saitama city that depicted flowers on a dead tree, but only when the curator learned the ancient (and no longer current) proverb «Flowers on a dead tree» did the curator understand the deeper meaning of the painting.[183] Also in Japan, an image of Mount Fuji, a hawk/falcon, and three egg plants, leads viewers to remember the proverb, «One Mt. Fuji, two falcons, three egg plants», a Hatsuyume dream predicting a long life.[184]

A study of school students found that students remembered proverbs better when there were visual representations of proverbs along with the verbal form of the proverbs.[185]

A bibliography on proverbs in visual form has been prepared by Mieder and Sobieski (1999). Interpreting visual images of proverbs is subjective, but familiarity with the depicted proverb helps.[186]

Some artists have used proverbs and anti-proverbs for titles of their paintings, alluding to a proverb rather than picturing it. For example, Vivienne LeWitt painted a piece titled «If the shoe doesn’t fit, must we change the foot?», which shows neither foot nor shoe, but a woman counting her money as she contemplates different options when buying vegetables.[187]

In 2018, 13 sculptures depicting Maltese proverbs were installed in open spaces of downtown Valletta.[188][189][190]

In cartoons[edit]

Cartoonists, both editorial and pure humorists, have often used proverbs, sometimes primarily building on the text, sometimes primarily on the situation visually, the best cartoons combining both. Not surprisingly, cartoonists often twist proverbs, such as visually depicting a proverb literally or twisting the text as an anti-proverb.[191] An example with all of these traits is a cartoon showing a waitress delivering two plates with worms on them, telling the customers, «Two early bird specials… here ya go.»[192]

The traditional Three wise monkeys were depicted in Bizarro with different labels. Instead of the negative imperatives, the one with ears covered bore the sign «See and speak evil», the one with eyes covered bore the sign «See and hear evil», etc. The caption at the bottom read «The power of positive thinking.»[193] Another cartoon showed a customer in a pharmacy telling a pharmacist, «I’ll have an ounce of prevention.»[194] The comic strip The Argyle Sweater showed an Egyptian archeologist loading a mummy on the roof of a vehicle, refusing the offer of a rope to tie it on, with the caption «A fool and his mummy are soon parted.»[195] The comic One Big Happy showed a conversation where one person repeatedly posed a part of various proverb and the other tried to complete each one, resulting in such humorous results as «Don’t change horses… unless you can lift those heavy diapers.»[196]

Editorial cartoons can use proverbs to make their points with extra force as they can invoke the wisdom of society, not just the opinion of the editors.[197] In an example that invoked a proverb only visually, when a US government agency (GSA) was caught spending money extravagantly, a cartoon showed a black pot labeled «Congress» telling a black kettle labeled «GSA», «Stop wasting the taxpayers’ money!»[198] It may have taken some readers a moment of pondering to understand it, but the impact of the message was the stronger for it.

Cartoons with proverbs are so common that Wolfgang Mieder has published a collected volume of them, many of them editorial cartoons. For example, a German editorial cartoon linked a current politician to the Nazis, showing him with a bottle of swastika-labeled wine and the caption «In vino veritas».[199]

One cartoonist very self-consciously drew and wrote cartoons based on proverbs for the University of Vermont student newspaper The Water Tower, under the title «Proverb place».[200]

In advertising[edit]

Proverbs are frequently used in advertising, often in slightly modified form.[201][202][203]

Ford once advertised its Thunderbird with, «One drive is worth a thousand words» (Mieder 2004b: 84). This is doubly interesting since the underlying proverb behind this, «One picture is worth a thousand words,» was originally introduced into the English proverb repertoire in an ad for televisions (Mieder 2004b: 83).

A few of the many proverbs adapted and used in advertising include:

- «Live by the sauce, dine by the sauce» (Buffalo Wild Wings)

- «At D & D Dogs, you can teach an old dog new tricks» (D & D Dogs)

- «If at first you don’t succeed, you’re using the wrong equipment» (John Deere)

- «A pfennig saved is a pfennig earned.» (Volkswagen)

- «Not only absence makes the heart grow fonder.» (Godiva Chocolatier)

- «Where Hogs fly» (Grand Prairie AirHogs) baseball team

- «Waste not. Read a lot.» (Half Price Books)

The GEICO company has created a series of television ads that are built around proverbs, such as «A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush»,[204] and «The pen is mightier than the sword»,[205] «Pigs may fly/When pigs fly»,[206] «If a tree falls in the forest…»,[207] and «Words can never hurt you».[208] Doritos made a commercial based on the proverb, «When pigs fly.»[209] Many advertisements that use proverbs shorten or amend them, such as, «Think outside the shoebox.»

Use of proverbs in advertising is not limited to the English language. Seda Başer Çoban has studied the use of proverbs in Turkish advertising.[210] Tatira has given a number of examples of proverbs used in advertising in Zimbabwe.[211] However, unlike the examples given above in English, all of which are anti-proverbs, Tatira’s examples are standard proverbs. Where the English proverbs above are meant to make a potential customer smile, in one of the Zimbabwean examples «both the content of the proverb and the fact that it is phrased as a proverb secure the idea of a secure time-honored relationship between the company and the individuals». When newer buses were imported, owners of older buses compensated by painting a traditional proverb on the sides of their buses, «Going fast does not assure safe arrival».[212]

Variations[edit]

Counter proverbs[edit]

There are often proverbs that contradict each other, such as «Look before you leap» and «He who hesitates is lost», or «Many hands make light work» and «Too many cooks spoil the broth». These have been labeled «counter proverbs»[213] or «antonymous proverbs».[214] Stanisław Lec observed, «Proverbs contradict each other. And that, to be sure, is folk wisdom.»[215]

When there are such counter proverbs, each can be used in its own appropriate situation, and neither is intended to be a universal truth.[216][217] Some pairs of proverbs are fully contradictory: “A messy desk is a sign of intelligence” and “A neat desk is a sign of a sick mind”.[24]

The concept of «counter proverb» is more about pairs of contradictory proverbs than about the use of proverbs to counter each other in an argument. For example, from the Tafi language of Ghana, the following pair of proverbs are counter to each other but are each used in appropriate contexts, «A co-wife who is too powerful for you, you address her as your mother» and «Do not call your mother’s co-wife your mother…»[218] In Nepali, there is a set of totally contradictory proverbs: «Religion is victorious and sin erodes» and «Religion erodes and sin is victorious».[219]

Also, the following pair are counter proverbs from the Kasena of Ghana: «It is the patient person who will milk a barren cow» and «The person who would milk a barren cow must prepare for a kick on the forehead».[220] From Lugbara language (of Uganda and Congo), there are a pair of counter proverbs: «The elephant’s tusk does not ovewhelm the elephant» and «The elephant’s tusks weigh the elephant down».[221] The two contradict each other, whether they are used in an argument or not (though indeed they were used in an argument). But the same work contains an appendix with many examples of proverbs used in arguing for contrary positions, but proverbs that are not inherently contradictory,[222] such as «One is better off with hope of a cow’s return than news of its death» countered by «If you don’t know a goat [before its death] you mock at its skin». Though this pair was used in a contradictory way in a conversation, they are not a set of «counter proverbs».[216]

Discussing counter proverbs in the Badaga language, Hockings explained that in his large collection «a few proverbs are mutually contradictory… we can be sure that the Badagas do not see the matter that way, and would explain such apparent contradictions by reasoning that proverb x is used in one context, while y is used in quite another.»[223] Comparing Korean proverbs, «when you compare two proverbs, often they will be contradictory.» They are used for «a particular situation».[224]

«Counter proverbs» are not the same as a «paradoxical proverb», a proverb that contains a seeming paradox.[225]

Metaproverbs[edit]

In many cultures, proverbs are so important and so prominent that there are proverbs about proverbs, that is, «metaproverbs». The most famous one is from Yoruba of Nigeria, «Proverbs are the horses of speech, if communication is lost we use proverbs to find it», used by Wole Soyinka in Death and the King’s Horsemen. In Mieder’s bibliography of proverb studies, there are twelve publications listed as describing metaproverbs.[226] Other metaproverbs include:

- As a boy should resemble his father, so should the proverb fit the conversation.» (Afar, Ethiopia)[227]

- «Proverbs are the cream of language» (Afar of Ethiopia)[228]

- «One proverb gives rise to a point of discussion and another ends it.» (Guji Oromo & Arsi Oromo, Ethiopia)[229][230]

- «Is proverb a child of chieftancy?» (Igala, Nigeria)[231]

- «Whoever has seen enough of life will be able to tell a lot of proverbs.» (Igala, Nigeria)[232]

- «Bereft of proverbs, speech flounders and falls short of its mark, whereas aided by them, communication is fleet and unerring» (Yoruba, Nigeria)[233]

- «A conversation without proverbs is like stew without salt.» (Oromo, Ethiopia)[234]

- «If you never offer your uncle palmwine, you’ll not learn many proverbs.» (Yoruba, Nigeria)[235]

- «If a proverb has no bearing on a proverb, one does not use it.»[236] (Yoruba, Nigeria)

- «Proverbs finish the problem.»[237] (Alaaba, Ethiopia)

- «When a proverb about a ragged basket is mentioned, the person who is skinny knows that he/she is the person alluded to.» (Igbo, Nigeria)[238]

- «A proverb is the quintessentially active bit of language.» (Turkish)[239]

- «The purest water is spring water, the most concise speech is proverb.» (Zhuang, China)[240]

- «A proverb does not lie.» (Arabic of Cairo)[241]

- «A saying is a flower, a proverb is a berry.» (Russian)[242]

- «Honey is sweet to the mouth; proverb is music to the ear.» (Tibetan) [243]

- «Old proverb are little Gospels» (Galician)[244]

- «Proverb[-using] man, queer and vulgar/bothering man» (Spanish)[245]

- «A hasty man talks without using a proverb.» (Kambaata, Ethiopia) [246]

- «He who has a father knows the proverb of grandfather.» (Kirundi, Burundi) [247]

- «The wisdom of the proverb cannot be surpassed.» (Turkish, Turkey) [248]

Applications[edit]

Blood chit used by WWII US pilots fighting in China, in case they were shot down by the Japanese. This leaflet to the Chinese depicts an American aviator being carried by two Chinese civilians. Text is «Plant melons and harvest melons, plant peas and harvest peas,» a Chinese proverb equivalent to «You Sow, So Shall You Reap».

Billboard outside defense plant during WWII, invoking the proverb of the three wise monkeys to urge security.

Wordless depiction of «Big fish eat little fish», Buenos Aires, urging, «Don’t panic, organize.»

There is a growing interest in deliberately using proverbs to achieve goals, usually to support and promote changes in society. Proverbs have also been used for public health promotion, such as promoting breast feeding with a shawl bearing a Swahili proverb «Mother’s milk is sweet».[249] Proverbs have also been applied for helping people manage diabetes,[250] to combat prostitution,[251] and for community development,[252] to resolve conflicts,[253][254] and to slow the transmission of HIV.[255]

The most active field deliberately using proverbs is Christian ministry, where Joseph G. Healey and others have deliberately worked to catalyze the collection of proverbs from smaller languages and the application of them in a wide variety of church-related ministries, resulting in publications of collections[256] and applications.[257][258] This attention to proverbs by those in Christian ministries is not new, many pioneering proverb collections having been collected and published by Christian workers.[259][260][261][262]

U.S. Navy Captain Edward Zellem pioneered the use of Afghan proverbs as a positive relationship-building tool during the war in Afghanistan, and in 2012 he published two bilingual collections[263][264] of Afghan proverbs in Dari and English, part of an effort of nationbuilding, followed by a volume of Pashto proverbs in 2014.[265]

Cultural values[edit]

Chinese proverb. It says, «Learn till old, live till old, and there is still three-tenths not learned,» meaning that no matter how old you are, there is still more learning or studying left to do.

Thai proverb depicted visually at a temple, «Better a monk»

There is a longstanding debate among proverb scholars as to whether the cultural values of specific language communities are reflected (to varying degree) in their proverbs. Many claim that the proverbs of a particular culture reflect the values of that specific culture, at least to some degree. Many writers have asserted that the proverbs of their cultures reflect their culture and values; this can be seen in such titles as the following: An introduction to Kasena society and culture through their proverbs,[266] Prejudice, power, and poverty in Haiti: a study of a nation’s culture as seen through its proverbs,[267] Proverbiality and worldview in Maltese and Arabic proverbs,[268] Fatalistic traits in Finnish proverbs,[269] Vietnamese cultural patterns and values as expressed in proverbs,[270] The Wisdom and Philosophy of the Gikuyu proverbs: The Kihooto worldview,[271] Spanish Grammar and Culture through Proverbs,[272] and «How Russian Proverbs Present the Russian National Character».[273] Kohistani has written a thesis to show how understanding Afghan Dari proverbs will help Europeans understand Afghan culture.[274]

However, a number of scholars argue that such claims are not valid. They have used a variety of arguments. Grauberg argues that since many proverbs are so widely circulated they are reflections of broad human experience, not any one culture’s unique viewpoint.[275] Related to this line of argument, from a collection of 199 American proverbs, Jente showed that only 10 were coined in the USA, so that most of these proverbs would not reflect uniquely American values.[276] Giving another line of reasoning that proverbs should not be trusted as a simplistic guide to cultural values, Mieder once observed «proverbs come and go, that is, antiquated proverbs with messages and images we no longer relate to are dropped from our proverb repertoire, while new proverbs are created to reflect the mores and values of our time»,[277] so old proverbs still in circulation might reflect past values of a culture more than its current values. Also, within any language’s proverb repertoire, there may be «counter proverbs», proverbs that contradict each other on the surface[213] (see section above). When examining such counter proverbs, it is difficult to discern an underlying cultural value. With so many barriers to a simple calculation of values directly from proverbs, some feel «one cannot draw conclusions about values of speakers simply from the texts of proverbs».[278]

Many outsiders have studied proverbs to discern and understand cultural values and world view of cultural communities.[279] These outsider scholars are confident that they have gained insights into the local cultures by studying proverbs, but this is not universally accepted.[276][280][281][282]

[283][284]

Seeking empirical evidence to evaluate the question of whether proverbs reflect a culture’s values, some have counted the proverbs that support various values. For example, Moon lists what he sees as the top ten core cultural values of the Builsa society of Ghana, as exemplified by proverbs. He found that 18% of the proverbs he analyzed supported the value of being a member of the community, rather than being independent.[285] This was corroboration to other evidence that collective community membership is an important value among the Builsa. In studying Tajik proverbs, Bell notes that the proverbs in his corpus «Consistently illustrate Tajik values» and «The most often observed proverbs reflect the focal and specific values» discerned in the thesis.[286]

A study of English proverbs created since 1900 showed in the 1960s a sudden and significant increase in proverbs that reflected more casual attitudes toward sex.[287] Since the 1960s was also the decade of the Sexual revolution, this shows a strong statistical link between the changed values of the decades and a change in the proverbs coined and used. Another study mining the same volume counted Anglo-American proverbs about religion to show that proverbs indicate attitudes toward religion are going downhill.[288]

There are many examples where cultural values have been explained and illustrated by proverbs. For example, from India, the concept that birth determines one’s nature «is illustrated in the oft-repeated proverb: there can be no friendship between grass-eaters and meat-eaters, between a food and its eater».[289] Proverbs have been used to explain and illustrate the Fulani cultural value of pulaaku.[290] But using proverbs to illustrate a cultural value is not the same as using a collection of proverbs to discern cultural values. In a comparative study between Spanish and Jordanian proverbs it is defined the social imagination for the mother as an archetype in the context of role transformation and in contrast with the roles of husband, son and brother, in two societies which might be occasionally associated with sexist and /or rural ideologies.[291]

Some scholars have adopted a cautious approach, acknowledging at least a genuine, though limited, link between cultural values and proverbs: «The cultural portrait painted by proverbs may be fragmented, contradictory, or otherwise at variance with reality… but must be regarded not as accurate renderings but rather as tantalizing shadows of the culture which spawned them.»[292] There is not yet agreement on the issue of whether, and how much, cultural values are reflected in a culture’s proverbs.

It is clear that the Soviet Union believed that proverbs had a direct link to the values of a culture, as they used them to try to create changes in the values of cultures within their sphere of domination. Sometimes they took old Russian proverbs and altered them into socialist forms.[293] These new proverbs promoted Socialism and its attendant values, such as atheism and collectivism, e.g. «Bread is given to us not by Christ, but by machines and collective farms» and «A good harvest is had only by a collective farm.» They did not limit their efforts to Russian, but also produced «newly coined proverbs that conformed to socialist thought» in Tajik and other languages of the USSR.[294]

Religion[edit]

Many proverbs from around the world address matters of ethics and expected of behavior. Therefore, it is not surprising that proverbs are often important texts in religions. The most obvious example is the Book of Proverbs in the Bible. Additional proverbs have also been coined to support religious values, such as the following from Dari of Afghanistan:[295] «In childhood you’re playful, In youth you’re lustful, In old age you’re feeble, So when will you before God be worshipful?»

Clearly proverbs in religion are not limited to monotheists; among the Badagas of India (Sahivite Hindus), there is a traditional proverb «Catch hold of and join with the man who has placed sacred ash [on himself].»[296] Proverbs are widely associated with large religions that draw from sacred books, but they are also used for religious purposes among groups with their own traditional religions, such as the Guji Oromo.[89] The broadest comparative study of proverbs across religions is The eleven religions and their proverbial lore, a comparative study. A reference book to the eleven surviving major religions of the world by Selwyn Gurney Champion, from 1945. Some sayings from sacred books also become proverbs, even if they were not obviously proverbs in the original passage of the sacred book.[297] For example, many quote «Be sure your sin will find you out» as a proverb from the Bible, but there is no evidence it was proverbial in its original usage (Numbers 32:23).

Not all religious references in proverbs are positive, some are cynical, such as the Tajik, «Do as the mullah says, not as he does.»[298] Also, note the Italian proverb, «One barrel of wine can work more miracles than a church full of saints». An Indian proverb is cynical about devotees of Hinduism, «[Only] When in distress, a man calls on Rama».[299] In the context of Tibetan Buddhism, some Ladakhi proverbs mock the lamas, e.g. «If the lama’s own head does not come out cleanly, how will he do the drawing upwards of the dead?… used for deriding the immoral life of the lamas.»[300] Proverbs do not have to explicitly mention religion or religious figures to be used to mock a religion, seen in the fact that in a collection of 555 proverbs from the Lur, a Muslim group in Iran, the explanations for 15 of them use illustrations that mock Muslim clerics.[301]

Dammann wrote, «In the [African] traditional religions, specific religious ideas recede into the background… The influence of Islam manifests itself in African proverbs… Christian influences, on the contrary, are rare.»[302] If widely true in Africa, this is likely due to the longer presence of Islam in many parts of Africa. Reflection of Christian values is common in Amharic proverbs of Ethiopia, an area that has had a presence of Christianity for well over 1,000 years. The Islamic proverbial reproduction may also be shown in the image of some animals such as the dog. Although dog is portrayed in many European proverbs as the most faithful friend of man, it is represented in some Islamic countries as impure, dirty, vile, cowardly, ungrateful and treacherous, in addition to links to negative human superstitions such as loneliness, indifference and bad luck.[303]

Psychology[edit]

Though much proverb scholarship is done by literary scholars, those studying the human mind have used proverbs in a variety of studies.[304] One of the earliest studies in this field is the Proverbs Test by Gorham, developed in 1956. A similar test is being prepared in German.[305] Proverbs have been used to evaluate dementia,[306][307][308] study the cognitive development of children,[309] measure the results of brain injuries,[310] and study how the mind processes figurative language.[49][311][312]

Paremiology[edit]

A sample of books used in the study of proverbs.

The study of proverbs is called paremiology which has a variety of uses in the study of such topics as philosophy, linguistics, and folklore. There are several types and styles of proverbs which are analyzed within Paremiology as is the use and misuse of familiar expressions which are not strictly ‘proverbial’ in the dictionary definition of being fixed sentences

Paremiological minimum[edit]

Grigorii Permjakov[313] developed the concept of the core set of proverbs that full members of society know, what he called the «paremiological minimum» (1979). For example, an adult American is expected to be familiar with «Birds of a feather flock together», part of the American paremiological minimum. However, an average adult American is not expected to know «Fair in the cradle, foul in the saddle», an old English proverb that is not part of the current American paremiological minimum. Thinking more widely than merely proverbs, Permjakov observed «every adult Russian language speaker (over 20 years of age) knows no fewer than 800 proverbs, proverbial expressions, popular literary quotations and other forms of cliches».[314] Studies of the paremiological minimum have been done for a limited number of languages, including Ukrainian,[315] Russian,[316] Hungarian,[317][318] Czech,[319] Somali,[320] Nepali,[321] Gujarati,[322] Spanish,[323] Esperanto,[324] Polish,[325] Polish.[326]

Two noted examples of attempts to establish a paremiological minimum in America are by Haas (2008) and Hirsch, Kett, and Trefil (1988), the latter more prescriptive than descriptive. There is not yet a recognized standard method for calculating the paremiological minimum, as seen by comparing the various efforts to establish the paremiological minimum in a number of languages.[327]

Sources for proverb study[edit]

A seminal work in the study of proverbs is Archer Taylor’s The Proverb (1931), later republished by Wolfgang Mieder with Taylor’s Index included (1985/1934). A good introduction to the study of proverbs is Mieder’s 2004 volume, Proverbs: A Handbook. Mieder has also published a series of bibliography volumes on proverb research, as well as a large number of articles and other books in the field. Stan Nussbaum has edited a large collection on proverbs of Africa, published on a CD, including reprints of out-of-print collections, original collections, and works on analysis, bibliography, and application of proverbs to Christian ministry (1998).[328] Paczolay has compared proverbs across Europe and published a collection of similar proverbs in 55 languages (1997). There is an academic journal of proverb study, Proverbium (ISSN 0743-782X), many back issues of which are available online.[329] A volume containing articles on a wide variety of topics touching on proverbs was edited by Mieder and Alan Dundes (1994/1981). Paremia is a Spanish-language journal on proverbs, with articles available online.[330] There are also papers on proverbs published in conference proceedings volumes from the annual Interdisciplinary Colloquium on Proverbs[331] in Tavira, Portugal. Mieder has published a two-volume International Bibliography of Paremiology and Phraseology, with a topical, language, and author index.[332] Mieder has also published a bibliography of collections of proverbs from around the world.[333] A broad introduction to proverb study, Introduction to Paremiology, edited by Hrisztalina Hrisztova-Gotthardt and Melita Aleksa Varga has been published in both hardcover and free open access, with articles by a dozen different authors.[334]

Noteworthy proverb scholars (paremiologists and paremiographers)[edit]

The study of proverbs has been built by a number of notable scholars and contributors. Earlier scholars were more concerned with collecting than analyzing. Desiderius Erasmus was a Latin scholar (1466–1536), whose collection of Latin proverbs, known as Adagia, spread Latin proverbs across Europe.[335] Juan de Mal Lara was a 16th century Spanish scholar, one of his books being 1568 Philosophia vulgar, the first part of which contains one thousand and one sayings. Hernán Núñez published a collection of Spanish proverbs (1555).

In the 19th century, a growing number of scholars published collections of proverbs, such as Samuel Adalberg who published collections of Yiddish proverbs (1888 & 1890) and Polish proverbs (1889–1894). Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the Anglican bishop in Nigeria, published a collection of Yoruba proverbs (1852). Elias Lönnrot published a collection of Finnish proverbs (1842).

From the 20th century onwards, proverb scholars were involved in not only collecting proverbs, but also analyzing and comparing proverbs. Alan Dundes was a 20th century American folklorist whose scholarly output on proverbs led Wolfgang Mieder to refer to him as a «pioneering paremiologist».[336] Matti Kuusi was a 20th century Finnish paremiologist, the creator of the Matti Kuusi international type system of proverbs.[337] With encouragement from Archer Taylor,[338] he founded the journal Proverbium: Bulletin d’Information sur les Recherches Parémiologiques, published from 1965 to 1975 by the Society for Finnish Literature, which was later restarted as an annual volume, Proverbium: International Yearbook of Proverb Scholarship. Archer Taylor was a 20th century American scholar, best known for his «magisterial»[339] book The Proverb.[340] Dimitrios Loukatos was a 20th century Greek proverb scholar, author of such works as Aetiological Tales of Modern Greek Proverbs.[341] Arvo Krikmann (1939–2017) was an Estonian proverb scholar, whom Wolfgang Mieder called «one of the leading paremiologists in the world»[342] and «master folklorist and paremiologist».[343] Elisabeth Piirainen was a German scholar with 50 proverb-related publications.[344]

Current proverb scholars have continued the trend to be involved in analysis as well as collection of proverbs. Claude Buridant is a 20th century French scholar whose work has concentrated on Romance languages.[345] Galit Hasan-Rokem is an Israeli scholar, associate editor of Proverbium: The yearbook of international proverb scholarship, since 1984. She has written on proverbs in Jewish traditions.[346] Joseph G. Healey is an American Catholic missionary in Kenya who has led a movement to sponsor African proverb scholars to collect proverbs from their own language communities.[347] This led Wolfgang Mieder to dedicate the «International Bibliography of New and Reprinted Proverb Collections» section of Proverbium 32 to Healey.[348] Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett is a scholar of Jewish history and folklore, including proverbs.[349] Wolfgang Mieder is a German-born proverb scholar who has worked his entire academic career in the US. He is the editor of ‘’Proverbium’’ and the author of the two volume International Bibliography of Paremiology and Phraseology.[350] He has been honored by four festschrift publications.[351][352][353][354] He has also been recognized by biographical publications that focused on his scholarship.[355][356] Dora Sakayan is a scholar who has written about German and Armenian studies, including Armenian Proverbs: A Paremiological Study with an Anthology of 2,500 Armenian Folk Sayings Selected and Translated into English.[357] An extensive introduction addresses the language and structure,[358] as well as the origin of Armenian proverbs (international, borrowed and specifically Armenian proverbs). Mineke Schipper is a Dutch scholar, best known for her book of worldwide proverbs about women, Never Marry a Woman with Big Feet – Women in Proverbs from Around the World.[359] Edward Zellem is an American proverb scholar who has edited books of Afghan proverbs, developed a method of collecting proverbs via the Web.[360]

See also[edit]

- Adage

- Anti-proverb

- Aphorism

- Blason Populaire

- Book of Proverbs

- Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable

- Brocard

- Legal maxim

- List of proverbial phrases

- Maxim

- Old wives’ tale

- Paremiology

- Paremiography

- Proverbial phrase

- Proverbium

- Saw (saying)

- Saying

- Wikiquote:English proverbs

- Wiktionary:Proverbs

References[edit]

- ^ «Proverbial Phrases from California», by Owen S. Adams, Western Folklore, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1949), pp. 95–116 doi:10.2307/1497581

- ^ Arvo Krikmann «the Great Chain Metaphor: An Open Sezame for Proverb Semantics?», Proverbium:Yearbook of International Scholarship, 11 (1994), pp. 117–124.

- ^ p. 12, Wolfgang Mieder. 1990. Not by bread alone: Proverbs of the Bible. New England Press.

- ^ Paczolay, Gyula. 1997. European Proverbs in 55 Languages. Veszpre’m, Hungary.

- ^ p. 25. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. «The wit of one, and the wisdom of many: General thoughts on the nature of the proverb. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age 3–40. Oxford University Press.

- ^ p. 3 Archer Taylor. 1931. The Proverb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ p. 5. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. «The wit of one, and the wisdom of many: General thoughts on the nature of the proverb. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age 3–40. Oxford University Press.

- ^ p. 73. Neil Norrick. 1985. How Proverbs Mean: Semantic Studies in English Proverbs. Amsterdam: Mouton.

- ^ p. 33. Sw. Anand Prahlad. 1996. African-American Proverbs in Context. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ p. 107, Hassan Zolfaghari & Hayat Ameri. «Persian Proverbs: Definitions and Characteristics». Journal of Islamic and Human Advanced Research 2(2012) 93–108.

- ^ p. 45. Alan Dundes. 1984. On whether weather ‘proverbs’ are proverbs. Proverbium 1:39–46. Also, 1989, in Folklore Matters edited by Alan Dundes, 92–97. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- ^ A Yorkshire proverb. 1883. The Academy. July 14, no. 584. p.30.

- ^ Ezgi Ulusoy Aranyosi. 2010. «Atasözü neydi, ne oldu?» [«What was, and what now is, a ‘proverb’?»]. Millî Folklor: International and Quarterly Journal of Cultural Studies 11.88: 5–15.

- ^ p. 64. Gillian Hansford. 2003. Understanding Chumburung proverbs. Journal of West African Languages 30.1:57–82.

- ^ p. 4,5. Daniel Ben-Amos. Introduction: Folklore in African Society. Forms of Folklore in Africa, edited by Bernth Lindfors, pp. 1–36. Austin: University of Texas.

- ^ p. 43. Sabir Badalkhan. 2000. «Ropes break at the weakest point»: Some examples of Balochi proverbs with background stories. Proverbium 17:43–69.

- ^ John C. Messenger, Jr. Anang Proverb-Riddles. The Journal of American Folklore Vol. 73, No. 289 (July–September 1960), pp. 225–235.

- ^ p. 418. Finnegan, Ruth. Oral Literature in Africa. The Saylor Foundation, 1982.

- ^ Umoh, S. J. 2007. The Ibibio Proverb – Riddles and Language Pedagogy. International Journal of Linguistics and Communication 11(2), 8–13.

- ^ Lexicography: Critical Concepts (2003) R. R. K. Hartmann, Mick R K Smith, ISBN 0415253659, p. 303

- ^ Barbour, Frances M. «Some uncommon sources of proverbs.» Midwest Folklore 13.2 (1963): 97–100.

- ^ Korosh Hadissi. 2010. A Socio-Historical Approach to Poetic Origins of Persian Proverbs. Iranian Studies 43.5: 599–605.

- ^ Thamen, Hla. 2000. Myanmar Proverbs in Myanmar and English. Yangon: Pattamya Ngamank Publishing.

- ^ a b Doyle, Charles Clay, Wolfgang Mieder, Fred R. Shapiro. 2012. The Dictionary of Modern Proverbs. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ p. 68. Kent, Graeme. 1991. Aesop’s Fables. Newmarket, UK: Brimax.

- ^ a b Michael Stanton. 1996. Advice is a dangerous gift. Proverbium 13: 331–345

- ^ a b Trokhimenko, Olga. 2003. «If You Sit on the Doorstep Long Enough, You Will Think of Something»: The Function of Proverbs in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Hobbit.» Proverbium (journal)20: 367–378.

- ^ Peter Unseth. 2014. A created proverb in a novel becomes broadly used in society: «‛Easily in but not easily out’, as the lobster said in his lobster pot.» Crossroads: A Journal of English Studies online access Archived 2015-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ p. 70, Winick, Stephen. 1998. The Proverb Process: Intertextuality and Proverbial Innovation in Popular Culture. University of Pennsylvania: PhD dissertation.

- ^ Hawthorn, Jeremy, ‘Ernest Bramah: Source of Ford Madox Ford’s Chinese Proverb?’ Notes and Queries, 63.2 (2016), 286–288.

- ^ p. 5. Alster, Bendt. 1979. An Akkadian and a Greek proverb. A comparative study. Die Welt des Orients 10. 1–5.

- ^ p. 17. Moran, William L. 1978a. An Assyriological gloss on the new Archilochus fragment. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 82. 17–19.

- ^ Unseth, Peter. «The World’s Oldest Living Proverb Discovered Thriving in Ethiopia.» Aethiopica 21 (2018): 226–236.

- ^ p. 325, Linda Tavernier-Almada. 1999. Prejudice, power, and poverty in Haiti: A study of a nation’s culture as seen through its proverbs. Proverbium 16:325–350.

- ^ p. 125. Aquilina, Joseph. 1972. A Comparative Dictionary of Maltese Proverbs. Malta: Royal University of Malta.

- ^ Mesfin Wodajo. 2012. Functions and Formal and Stylistic Features of Kafa Proverbs. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

- ^ p. 22, Janice Raymond. Mongolian Proverbs: A window into their world. San Diego: Alethinos Books.

- ^ Rethabile M Possa-Mogoera. The Dynamism of Culture: The Case of Sesotho Proverbs.» Southern African Journal for Folklore Studies Vol. 20 (2) October.

- ^ p. 68. Okumba Miruka. 2001. Oral Literature of the Luo. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers.

- ^ Charles Clay Doyle, Wolfgang Mieder, Fred R. Shapiro. 2012. The Dictionary of Modern Proverbs. Yale University Press.

- ^ p. 5. Wolfgang Mieder. 1993. Proverbs are never out of season. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Mieder, Wolfgang. 2017. Futuristic Paremiography and Paremiology: A Plea for the Collection and Study of Modern Proverbs. Poslovitsy v frazeologicheskom pole: Kognitivnyi, diskursivnyi, spoostavitel’nyi aspekty. Ed. T.N. Fedulenkova. Vladimir: Vladimirskii Gosudarstvennyie Universitet, 2017. 205–226.

- ^ Jesenšek, Vida. 2014. Pragmatic and stylistic aspects of proverbs. Introduction to Paremiology: A Comprehensive Guide to Proverb Studies, ed. by Hrisztalina Hrisztova-Gotthardt and Melita Aleksa Varga, pp. 133–161. Warsaw & Berlin: DeGruyter Open.

- ^ p. 224,225. Flavell, Linda and roger Flavell. 1993. The Dictionary of Proverbs and Their Origins. London: Kyle Cathie.

- ^ p. 158. Evan Bell. 2009. An analysis of Tajik proverbs. Masters thesis, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics.

- ^ Sjaak van der Geest. 1996. The Elder and His Elbow: Twelve Interpretations of an Akan Proverb. Research in African Literatures Vol. 27, No. 3: 110–118.

- ^ Owomoyela, Oyekan. 1988. A Kì í : Yorùbá proscriptive and prescriptive proverbs. Lanham, MD : University Press of America.

- ^ pp. 236–237. Siran, Jean-Louis. 1993. Rhetoric, tradition, and communication: The dialectics of meaning in proverb use. Man n.s. 28.2:225–242.

- ^ a b Michael Kiang, et al, Cognitive, neurophysiological, and functional correlates of proverb interpretation abnormalities in schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2007), 13, 653–663. [Futuristic paremiography and paremiology: a plea for the collection and study of modern proverbs. Online access]

- ^ See Mac Coinnigh, Marcas. Syntactic Structures in Irish-Language Proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 29, 95–136.

- ^ Sebastian J. Floor. 2005. Poetic Fronting in a Wisdom Poetry Text: The Information Structure of Proverbs 7. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 31: 23–58.

- ^ p. 20, 21. Unseth, Peter, Daniel Kliemt, Laurel Morgan, Stephen Nelson, Elaine Marie Scherrer. 2017. Wellerism proverbs: Mapping their distribution. GIALens 11.3: website

- ^ p. 176. Roos, Marti, Hans Nugteren, Zinaida Waibel. 2006. Khakas and Shor proverbs and proverbial sayings. In Exploring the Eastern Frontiers of Turkic, ed by Marcel Erdal and Irina Nevskaya, pp. 157–192. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ^ p. 135. Sakayan, Dora. 1999. Reported and direct speech in proverbs: On Armenian dialogue proverbs. Proverbium 16: 303–324.

- ^ p. 246. Mitchison, Naomi and Amos Kgamanyane Pilane. 1967. The Bakgatla of South-East Botswana As Seen through Their Proverbs. Folklore Vol. 78, No. 4: 241–268.

- ^ p. 221. Kone, Kasim. 1997. Bamana verbal art: An ethnographic study of proverbs. PhD dissertation, Indiana University.

- ^ p. 21. Norrick, Neal R. «Subject area, terminology, proverb definitions, proverb features.» Introduction to paremiology: A comprehensive guide to proverb studies, edited by Hrisztalina Hristova-Gotthardt and Melita Aleksa Varga, (2014): 7-27.

- ^ p. 691. Michael Ahland. 2009. From topic to subject: Grammatical change in the Amharic possessive construction. Studies in Language 33.3 pp. 685–717.

- ^ p. 72. Nikolaos Lazaridis. 2007. Wisdom in Loose Form: The Language of Egyptian and Greek Proverbs in Collections of the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. Brill

- ^ p. 64. Christopher J. Pluger. 2014. Translating New Testament proverb-like sayings in the style of Nsenga proverbs. Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics MA thesis.

- ^ Szpila, Grzegorz. 2001. Archaic lexis in Polish Proverbs. In Władysław Witalisz (ed.), «And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche»: Studies on Language and Literature in Honour of Professor Dr. Karl Heinz Göller, pp. 187–193. Kraków 2001.

- ^ Mafenya, Livhuwani Lydia. The proverb in Venda: a linguistic analysis. MA Diss. University of Johannesburg, 1994,

- ^ p. 36. Watson, Wilfred GE. Classical Hebrew poetry: a guide to its techniques. A&C Black, 2004.

- ^ p. xviii. Taylor, W(illiam) E(rnest). 1891. Giriyama Vocabulary and Collections. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- ^ Tea Shurgaia (2020) The Proverbial Wisdom of a Georgian Language Island in Iran, Iranian Studies, 53:3–4, 551–571, doi:10.1080/00210862.2020.1716189

- ^ Ketenchiev, M.B., Akhmatova M.A., and Dodueva A.T. 2022. “Archaic Vocabulary in Karachay-Balkar Paroemias”. Polylinguality and Transcultural Practices, 19 (2), 297–307. doi:10.22363/2618-897X-2022-19-2-297-307 [in Russian]

- ^ Merrick, Captain G. 1905. Huasa Proverbs. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., p. 6,7.

- ^ Madiyorova Valida Quvondiq qizi. Analysis of Archaic Words in the Structure of English and Uzbek Proverbs. EPRA International Journal of Research and Development 6.4.2021: 360–362.

- ^ p. 33. Wolfgang Mieder. 2014. Behold the Proverbs of a People: Proverbial Wisdom in Culture, Literature, and Politics. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ Issa O. Sanusi and R.K. Omoloso. The role of Yoruba proverbs in preserving archaic lexical items and expressions in Yoruba.

[1] - ^ Eme, Cecilia A., Davidson U. Mbagwu, and Benjamin I. Mmadike. «Igbo proverbs and loss of metaphors.» PREORC Journal of Arts and Humanities 1.1 (2016): 72–91.

- ^ a b Lisa Reilly & Mary B. Shepard (2016) «Sufferance fait ease en temps»: word as image at St Michael-le-Belfrey, York. Word & Image 32:2, 218–234. doi:10.1080/02666286.2016.1167577.

- ^ p. ii. Thomas Fielding. 1825. Select proverbs of all nations. New York: Covert.

- ^ p. 146. Pritchard, James. 1958. The Ancient Near East, vol. 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ p. 67. Ju-Hong Yun and Pashai Language Committee. 2010. On a mountain there is still a road. Peshawar, Pakistan: InterLit Foundation.

- ^ p. 24. Calvin C. Katabarwa and Angelique Chelo. 2012. Wisdom from Orma, Kenya proverbs and wise sayings. Nairobi: African Proverbs Working Group. http://www.afriprov.org/images/afriprov/books/wisdomofOrmaproverbs.pdf

- ^ Kamil V. Zvelebil. 1987. The Sound of the One Hand. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1, pp. 125–126.

- ^ p. 16, Edward Zellem. 2012. Zarbul Masalha: 151 Aghan Dari proverbs.

- ^ p. 164. Philip B. Yampolsky, (trans.). 1977. The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. New York, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Ludwik Sternbach. 1981. Indian Wisdom and Its Spread beyond India. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 101, No. 1, pp. 97–131.

- ^ Matti Kuusi; Marje Joalaid; Elsa Kokare; Arvo Krikmann; Kari Laukkanen; Pentti Leino; Vaina Mālk; Ingrid Sarv. Proverbia Septentrionalia. 900 Balto-Finnic Proverb Types with Russian, Baltic, German and Scandinavian Parallels. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia (1985)

- ^ Fiedler, Sabine. 1999. Phraseology in planned languages. Language problems and language planning 23.2: 175–187.