From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can be described as the ability to perceive or infer information, and to retain it as knowledge to be applied towards adaptive behaviors within an environment or context.

Intelligence is most often studied in humans but has also been observed in both non-human animals and in plants despite controversy as to whether some of these forms of life exhibit intelligence.[1][2] Intelligence in computers or other machines is called artificial intelligence.

Etymology[edit]

Main article: Nous

The word intelligence derives from the Latin nouns intelligentia or intellēctus, which in turn stem from the verb intelligere, to comprehend or perceive. In the Middle Ages, the word intellectus became the scholarly technical term for understanding, and a translation for the Greek philosophical term nous. This term, however, was strongly linked to the metaphysical and cosmological theories of teleological scholasticism, including theories of the immortality of the soul, and the concept of the active intellect (also known as the active intelligence). This approach to the study of nature was strongly rejected by the early modern philosophers such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and David Hume, all of whom preferred «understanding» (in place of «intellectus» or «intelligence») in their English philosophical works.[3][4] Hobbes for example, in his Latin De Corpore, used «intellectus intelligit«, translated in the English version as «the understanding understandeth», as a typical example of a logical absurdity.[5] «Intelligence» has therefore become less common in English language philosophy, but it has later been taken up (with the scholastic theories which it now implies) in more contemporary psychology.[6]

Definitions[edit]

Unsolved problem in philosophy:

What exactly is intelligence? How could an external observer prove that an agent is intelligent?

The definition of intelligence is controversial, varying in what its abilities are and whether or not it is quantifiable.[7] Some groups of psychologists have suggested the following definitions:

From «Mainstream Science on Intelligence» (1994), an op-ed statement in the Wall Street Journal signed by fifty-two researchers (out of 131 total invited to sign):[8]

A very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience. It is not merely book learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings—»catching on,» «making sense» of things, or «figuring out» what to do.[9]

From Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995), a report published by the Board of Scientific Affairs of the American Psychological Association:

Individuals differ from one another in their ability to understand complex ideas, to adapt effectively to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning, to overcome obstacles by taking thought. Although these individual differences can be substantial, they are never entirely consistent: a given person’s intellectual performance will vary on different occasions, in different domains, as judged by different criteria. Concepts of «intelligence» are attempts to clarify and organize this complex set of phenomena. Although considerable clarity has been achieved in some areas, no such conceptualization has yet answered all the important questions, and none commands universal assent. Indeed, when two dozen prominent theorists were recently asked to define intelligence, they gave two dozen, somewhat different, definitions.[10]

Besides those definitions, psychology and learning researchers also have suggested definitions of intelligence such as the following:

| Researcher | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Alfred Binet | Judgment, otherwise called «good sense», «practical sense», «initiative», the faculty of adapting one’s self to circumstances … auto-critique.[11] |

| David Wechsler | The aggregate or global capacity of the individual to act purposefully, to think rationally, and to deal effectively with his environment.[12] |

| Lloyd Humphreys | «…the resultant of the process of acquiring, storing in memory, retrieving, combining, comparing, and using in new contexts information and conceptual skills».[13] |

| Howard Gardner | To my mind, a human intellectual competence must entail a set of skills of problem solving — enabling the individual to resolve genuine problems or difficulties that he or she encounters and, when appropriate, to create an effective product — and must also entail the potential for finding or creating problems — and thereby laying the groundwork for the acquisition of new knowledge.[14] |

| Linda Gottfredson | The ability to deal with cognitive complexity.[15] |

| Robert Sternberg & William Salter | Goal-directed adaptive behavior.[16] |

| Reuven Feuerstein | The theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability describes intelligence as «the unique propensity of human beings to change or modify the structure of their cognitive functioning to adapt to the changing demands of a life situation».[17] |

| Shane Legg & Marcus Hutter | A synthesis of 70+ definitions from psychology, philosophy, and AI researchers: «Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments»,[7] which has been mathematically formalized.[18] |

| Alexander Wissner-Gross | F = T ∇ S [19] [19]

«Intelligence is a force, F, that acts so as to maximize future freedom of action. It acts to maximize future freedom of action, or keep options open, with some strength T, with the diversity of possible accessible futures, S, up to some future time horizon, τ. In short, intelligence doesn’t like to get trapped». |

Human[edit]

Human intelligence is the intellectual power of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness.[20] Intelligence enables humans to remember descriptions of things and use those descriptions in future behaviors. It is a cognitive process. It gives humans the cognitive abilities to learn, form concepts, understand, and reason, including the capacities to recognize patterns, innovate, plan, solve problems, and employ language to communicate. Intelligence enables humans to experience and think.[21]

Intelligence is different from learning. Learning refers to the act of retaining facts and information or abilities and being able to recall them for future use, while intelligence is the cognitive ability of someone to perform these and other processes. There have been various attempts to quantify intelligence via testing, such as the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test. However, many people disagree with the validity of IQ tests, stating that they cannot accurately measure intelligence.[22]

There is debate about if human intelligence is based on hereditary factors or if it is based on environmental factors. Hereditary intelligence is the theory that intelligence is fixed upon birth and not able to grow. Environmental intelligence is the theory that intelligence is developed throughout life depending on the environment around the person. An environment that cultivates intelligence is one that challenges the person’s cognitive abilities.[22]

Much of the above definition applies also to the intelligence of non-human animals.[citation needed]

Emotional[edit]

Emotional intelligence is thought to be the ability to convey emotion to others in an understandable way as well as to read the emotions of others accurately.[23] Some theories imply that a heightened emotional intelligence could also lead to faster generating and processing of emotions in addition to the accuracy.[24] In addition, higher emotional intelligence is thought to help us manage emotions, which is beneficial for our problem-solving skills. Emotional intelligence is important to our mental health and has ties into social intelligence.[23]

[edit]

Social intelligence is the ability to understand the social cues and motivations of others and oneself in social situations. It is thought to be distinct to other types of intelligence, but has relations to emotional intelligence. Social intelligence has coincided with other studies that focus on how we make judgements of others, the accuracy with which we do so, and why people would be viewed as having positive or negative social character. There is debate as to whether or not these studies and social intelligence come from the same theories or if there is a distinction between them, and they are generally thought to be of two different schools of thought.[25]

Book smart and street smart[edit]

Concepts of «book smarts» and «street smart» are contrasting views based on the premise that some people have knowledge gained through academic study, but may lack the experience to sensibly apply that knowledge, while others have knowledge gained through practical experience, but may lack accurate information usually gained through study by which to effectively apply that knowledge. Artificial intelligence researcher Hector Levesque has noted that:

Given the importance of learning through text in our own personal lives and in our culture, it is perhaps surprising how utterly dismissive we tend to be of it. It is sometimes derided as being merely «book knowledge,» and having it is being «book smart.» In contrast, knowledge acquired through direct experience and apprenticeship is called «street knowledge,» and having it is being «street smart».[26]

Nonhuman animal[edit]

Although humans have been the primary focus of intelligence researchers, scientists have also attempted to investigate animal intelligence, or more broadly, animal cognition. These researchers are interested in studying both mental ability in a particular species, and comparing abilities between species. They study various measures of problem solving, as well as numerical and verbal reasoning abilities. Some challenges in this area are defining intelligence so that it has the same meaning across species (e.g. comparing intelligence between literate humans and illiterate animals), and also operationalizing a measure that accurately compares mental ability across different species and contexts.[citation needed]

Wolfgang Köhler’s research on the intelligence of apes is an example of research in this area. Stanley Coren’s book, The Intelligence of Dogs is a notable book on the topic of dog intelligence.[27] (See also: Dog intelligence.) Non-human animals particularly noted and studied for their intelligence include chimpanzees, bonobos (notably the language-using Kanzi) and other great apes, dolphins, elephants and to some extent parrots, rats and ravens.[28]

Cephalopod intelligence also provides an important comparative study. Cephalopods appear to exhibit characteristics of significant intelligence, yet their nervous systems differ radically from those of backboned animals. Vertebrates such as mammals, birds, reptiles and fish have shown a fairly high degree of intellect that varies according to each species. The same is true with arthropods.[29]

g factor in non-humans[edit]

Evidence of a general factor of intelligence has been observed in non-human animals. The general factor of intelligence, or g factor, is a psychometric construct that summarizes the correlations observed between an individual’s scores on a wide range of cognitive abilities. First described in humans, the g factor has since been identified in a number of non-human species.[30]

Cognitive ability and intelligence cannot be measured using the same, largely verbally dependent, scales developed for humans. Instead, intelligence is measured using a variety of interactive and observational tools focusing on innovation, habit reversal, social learning, and responses to novelty. Studies have shown that g is responsible for 47% of the individual variance in cognitive ability measures in primates[30] and between 55% and 60% of the variance in mice (Locurto, Locurto). These values are similar to the accepted variance in IQ explained by g in humans (40–50%).[31]

Plant[edit]

It has been argued that plants should also be classified as intelligent based on their ability to sense and model external and internal environments and adjust their morphology, physiology and phenotype accordingly to ensure self-preservation and reproduction.[32][33]

A counter argument is that intelligence is commonly understood to involve the creation and use of persistent memories as opposed to computation that does not involve learning. If this is accepted as definitive of intelligence, then it includes the artificial intelligence of robots capable of «machine learning», but excludes those purely autonomic sense-reaction responses that can be observed in many plants. Plants are not limited to automated sensory-motor responses, however, they are capable of discriminating positive and negative experiences and of «learning» (registering memories) from their past experiences. They are also capable of communication, accurately computing their circumstances, using sophisticated cost–benefit analysis and taking tightly controlled actions to mitigate and control the diverse environmental stressors.[1][2][34]

Artificial[edit]

Scholars studying artificial intelligence have proposed definitions of intelligence that include the intelligence demonstrated by machines. Some of these definitions are meant to be general enough to encompass human and other animal intelligence as well. An intelligent agent can be defined as a system that perceives its environment and takes actions which maximize its chances of success.[35] Kaplan and Haenlein define artificial intelligence as «a system’s ability to correctly interpret external data, to learn from such data, and to use those learnings to achieve specific goals and tasks through flexible adaptation».[36] Progress in artificial intelligence can be demonstrated in benchmarks ranging from games to practical tasks such as protein folding.[37] Existing AI lags humans in terms of general intelligence, which is sometimes defined as the «capacity to learn how to carry out a huge range of tasks».[38]

Singularitarian Eliezer Yudkowsky provides a loose qualitative definition of intelligence as «that sort of smartish stuff coming out of brains, which can play chess, and price bonds, and persuade people to buy bonds, and invent guns, and figure out gravity by looking at wandering lights in the sky; and which, if a machine intelligence had it in large quantities, might let it invent molecular nanotechnology; and so on». Mathematician Olle Häggström defines intelligence in terms of «optimization power», an agent’s capacity for efficient cross-domain optimization of the world according to the agent’s preferences, or more simply the ability to «steer the future into regions of possibility ranked high in a preference ordering». In this optimization framework, Deep Blue has the power to «steer a chessboard’s future into a subspace of possibility which it labels as ‘winning’, despite attempts by Garry Kasparov to steer the future elsewhere.»[39] Hutter and Legg, after surveying the literature, define intelligence as «an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments».[40][41] While cognitive ability is sometimes measured as a one-dimensional parameter, it could also be represented as a «hypersurface in a multidimensional space» to compare systems that are good at different intellectual tasks.[42] Some skeptics believe that there is no meaningful way to define intelligence, aside from «just pointing to ourselves».[43]

See also[edit]

- Active intellect

- Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory

- Intellect

- Intelligence (journal)

- Knowledge

- Neuroscience and intelligence

- Noogenesis – Philosophical concept of biosphere successor via humankind’s rational activities

- Outline of human intelligence

- Passive intellect

- Superintelligence

- Sapience

References[edit]

- ^ a b Goh, C. H.; Nam, H. G.; Park, Y. S. (2003). «Stress memory in plants: A negative regulation of stomatal response and transient induction of rd22 gene to light in abscisic acid-entrained Arabidopsis plants». The Plant Journal. 36 (2): 240–255. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01872.x. PMID 14535888.

- ^ a b Volkov, A. G.; Carrell, H.; Baldwin, A.; Markin, V. S. (2009). «Electrical memory in Venus flytrap». Bioelectrochemistry. 75 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.03.005. PMID 19356999.

- ^ Maich, Aloysius (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary. Blackwell. p. 305.

- ^ Nidditch, Peter. «Foreword». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Oxford University Press. p. xxii.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas; Molesworth, William (15 February 1839). «Opera philosophica quæ latine scripsit omnia, in unum corpus nunc primum collecta studio et labore Gulielmi Molesworth .» Londoni, apud Joannem Bohn. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ This paragraph almost verbatim from Goldstein, Sam; Princiotta, Dana; Naglieri, Jack A., Eds. (2015). Handbook of Intelligence: Evolutionary Theory, Historical Perspective, and Current Concepts. New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London: Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4939-1561-3.

- ^ a b S. Legg; M. Hutter (2007). «A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence». Advances in Artificial General Intelligence: Concepts, Architectures and Algorithms. Vol. 157. pp. 17–24. ISBN 9781586037581.

- ^ Gottfredson & 1997777, pp. 17–20

- ^ Gottfredson, Linda S. (1997). «Mainstream Science on Intelligence (editorial)» (PDF). Intelligence. 24: 13–23. doi:10.1016/s0160-2896(97)90011-8. ISSN 0160-2896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2014.

- ^ Neisser, Ulrich; Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert; Sternberg, Robert J.; Urbina, Susana (1996). «Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns» (PDF). American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.51.2.77. ISSN 0003-066X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Binet, Alfred (1916) [1905]. «New methods for the diagnosis of the intellectual level of subnormals». The development of intelligence in children: The Binet-Simon Scale. E.S. Kite (Trans.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 37–90. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

originally published as Méthodes nouvelles pour le diagnostic du niveau intellectuel des anormaux. L’Année Psychologique, 11, 191–244

- ^ Wechsler, D (1944). The measurement of adult intelligence. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-19-502296-4. OCLC 219871557. ASIN = B000UG9J7E

- ^ Humphreys, L. G. (1979). «The construct of general intelligence». Intelligence. 3 (2): 105–120. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(79)90009-6.

- ^ Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0-465-02510-7. OCLC 221932479.

- ^ Gottfredson, L. (1998). «The General Intelligence Factor» (PDF). Scientific American Presents. 9 (4): 24–29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ Sternberg RJ; Salter W (1982). Handbook of human intelligence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29687-8. OCLC 11226466.

- ^ Feuerstein, R., Feuerstein, S., Falik, L & Rand, Y. (1979; 2002). Dynamic assessments of cognitive modifiability. ICELP Press, Jerusalem: Israel; Feuerstein, R. (1990). The theory of structural modifiability. In B. Presseisen (Ed.), Learning and thinking styles: Classroom interaction. Washington, DC: National Education Associations

- ^ S. Legg; M. Hutter (2007). «Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence». Minds and Machines. 17 (4): 391–444. arXiv:0712.3329. Bibcode:2007arXiv0712.3329L. doi:10.1007/s11023-007-9079-x. S2CID 847021.

- ^ «TED Speaker: Alex Wissner-Gross: A new equation for intelligence». TED.com. 6 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Tirri, Nokelainen (2011). Measuring Multiple Intelligences and Moral Sensitivities in Education. Moral Development and Citizenship Education. Springer. ISBN 978-94-6091-758-5. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ Colom, Roberto (December 2010). «Human intelligence and brain networks». Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12 (4): 489–501. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/rcolom. PMC 3181994. PMID 21319494.

- ^ a b Bouchard, Thomas J. (1982). «Review of The Intelligence Controversy». The American Journal of Psychology. 95 (2): 346–349. doi:10.2307/1422481. ISSN 0002-9556. JSTOR 1422481.

- ^ a b Salovey, Peter; Mayer, John D. (March 1990). «Emotional Intelligence». Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 9 (3): 185–211. doi:10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG. hdl:10654/36316. ISSN 0276-2366. S2CID 219900460.

- ^ Mayer, John D.; Salovey, Peter (1 October 1993). «The intelligence of emotional intelligence». Intelligence. 17 (4): 433–442. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(93)90010-3. ISSN 0160-2896.

- ^ Walker, Ronald E.; Foley, Jeanne M. (December 1973). «Social Intelligence: Its History and Measurement». Psychological Reports. 33 (3): 839–864. doi:10.2466/pr0.1973.33.3.839. ISSN 0033-2941. S2CID 144839425.

- ^ Hector J. Levesque, Common Sense, the Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI (2017), p. 80.

- ^ Coren, Stanley (1995). The Intelligence of Dogs. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-37452-0. OCLC 30700778.

- ^ Childs, Casper. «WORDS WITH AN ASTRONAUT». Valenti. Codetipi. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Roth, Gerhard (19 December 2015). «Convergent evolution of complex brains and high intelligence». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 370 (1684): 20150049. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0049. PMC 4650126. PMID 26554042.

- ^ a b Reader, S. M., Hager, Y., & Laland, K. N. (2011). The evolution of primate general and cultural intelligence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1017–1027.

- ^ Kamphaus, R. W. (2005). Clinical assessment of child and adolescent intelligence. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Trewavas, Anthony (September 2005). «Green plants as intelligent organisms». Trends in Plant Science. 10 (9): 413–419. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.005. PMID 16054860.

- ^ Trewavas, A. (2002). «Mindless mastery». Nature. 415 (6874): 841. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..841T. doi:10.1038/415841a. PMID 11859344. S2CID 4350140.

- ^ Rensing, L.; Koch, M.; Becker, A. (2009). «A comparative approach to the principal mechanisms of different memory systems». Naturwissenschaften. 96 (12): 1373–1384. Bibcode:2009NW…..96.1373R. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0591-0. PMID 19680619. S2CID 29195832.

- ^ Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-790395-5. OCLC 51325314.

- ^ «Kaplan Andreas and Haelein Michael (2019) Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence, Business Horizons, 62(1)».

- ^ «How did a company best known for playing games just crack one of science’s toughest puzzles?». Fortune. 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Heath, Nick (2018). «What is artificial general intelligence?». ZDNet. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Häggström, Olle (2016). Here be dragons: science, technology and the future of humanity. Oxford. pp. 103, 104. ISBN 9780191035395.

- ^ Gary Lea (2015). «The Struggle To Define What Artificial Intelligence Actually Means». Popular Science. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Legg, Shane; Hutter, Marcus (30 November 2007). «Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence». Minds and Machines. 17 (4): 391–444. arXiv:0712.3329. doi:10.1007/s11023-007-9079-x. S2CID 847021.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (First ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. «Chapter 4: The Kinetics of an Intelligence Explosion», footnote 9. ISBN 978-0-19-967811-2.

- ^ «Superintelligence: The Idea That Eats Smart People». idlewords.com. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Haier, Richard (2016). The Neuroscience of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, Robert J.; Kaufman, Scott Barry, eds. (2011). The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108770422. ISBN 9780521739115. S2CID 241027150.

- Mackintosh, N. J. (2011). IQ and Human Intelligence (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958559-5.

- Flynn, James R. (2009). What Is Intelligence: Beyond the Flynn Effect (expanded paperback ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74147-7.

- Lay summary in: C Shalizi (27 April 2009). «What Is Intelligence? Beyond the Flynn Effect». University of Michigan (Review). Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

- Stanovich, Keith (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2.

- Lay summary in: Jamie Hale. «What Intelligence Tests Miss». Psych Central (Review). Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- Blakeslee, Sandra; Hawkins, Jeff (2004). On intelligence. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7456-7. OCLC 55510125.

- Bock, Gregory; Goode, Jamie; Webb, Kate, eds. (2000). The Nature of Intelligence. Novartis Foundation Symposium 233. Chichester: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0470870850. ISBN 978-0471494348.

- Lay summary in: William D. Casebeer (30 November 2001). «The Nature of Intelligence». Mental Help (Review). Archived from the original on 26 May 2013.

- Wolman, Benjamin B., ed. (1985). Handbook of Intelligence. consulting editors: Douglas K. Detterman, Alan S. Kaufman, Joseph D. Matarazzo. New York (NY): Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-89738-5.

- Terman, Lewis Madison; Merrill, Maude A. (1937). Measuring intelligence: A guide to the administration of the new revised Stanford-Binet tests of intelligence. Riverside textbooks in education. Boston (MA): Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 964301.

- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Th. (1916). The development of intelligence in children: The Binet-Simon Scale. Publications of the Training School at Vineland New Jersey Department of Research No. 11. E. S. Kite (Trans.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 1. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

External links[edit]

- Intelligence on In Our Time at the BBC

- History of Influences in the Development of Intelligence Theory and Testing Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Developed by Jonathan Plucker at Indiana University

- The Limits of Intelligence: The laws of physics may well prevent the human brain from evolving into an ever more powerful thinking machine by Douglas Fox in Scientific American, 14 June 2011.

- A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence

- | Causal Entropic Forces

Scholarly journals and societies

- Intelligence (journal homepage)

- International Society for Intelligence Research (homepage)

Are you intelligent?

Before you start to search for old IQ test results, let’s talk. The definition of “intelligence,” how it’s measured, and what it actually means to be “intelligent” may actually come as a surprise. Even the most important theories regarding intelligence, including Gardener’s nine types of intelligence, has been disputed by the world’s big names in psychology.

Everyone has their own definition of intelligence, but what do psychologists say? How do they measure intelligence? The answer isn’t so simple. Let’s touch on the basics of what intelligence is, how it’s been defined in recent years, and where the theories of intelligence are moving.

The two definitions of intelligence are the root of the controversies regarding how to measure and identify intelligence. The first definition is: “Intelligence is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.” The other definition is more complex: “Intelligence is the collection of information of military or political value.”

The second definition infers that intelligence is a measure of potential success throughout a community. This use for intelligence is what led psychologists to develop the IQ test.

Can Intelligence Be Measured? IQ Tests And Intelligence

In the early 1900s, French psychologist Alfred Binet helped to developed the first type of intelligence quotient tests, or IQ tests. The French government wanted to use the test to determine which children were more likely to succeed in school and which children needed more help.

Binet’s original test measured the “mental age” of children based on the average age and skills of a group of students. He admitted that the test had limits and that a single number was not enough to accurately depict all of the factors that influence intelligence.

Still, the test was adapted to American schools and is still used to measure intelligence today. High IQ is still associated with overall job performance and life “success.” IQ can change over the span of a person’s lifetime. While it is very easy to decrease a person’s IQ, science is still looking for ways to “increase” a person’s IQ points.

Controversy with IQ Tests: Intelligence and Speed

Unfortunately, even through many revisions of the standard IQ tests, there are still flaws in the design of the test. Let’s just look at one for right now.

Intelligence has a lot to do with “speed.” If I give you a complex problem on an IQ test, you might need a few minutes to solve it or a month to solve it. In both cases, you have the ability to solve the problem, but the person who can solve the problem more quickly will end up with the higher IQ score.

But what if you have learned how to solve the test before? The IQ test does take in your actual age, but other factors (including your education) aren’t necessarily taken into account. Remember, in both cases, the person learned how to solve the problem eventually, and when asked to solve the problem again, they could probably increase their speed. Does the IQ test accurately show how often people have had to solve related problems before the IQ test was administered?

Fluid Vs. Crystallized Intelligence

These questions have led people to explore different types of intelligence. How can we recognize people who take a little longer to learn something, but still have the ability to do so? How do we categorize people that just need to pull on past experiences to solve problems and repeat learned facts?

One of the ways we make these distinctions is by identifying fluid vs. crystallized intelligence. The theory of these types of intelligence was developed by Raymond Cattell, a psychologist who is also known for his work in trait psychology.

He theorized that there are two types of intelligence: fluid and crystallized intelligence.

Fluid intelligence is the ability to gather, store, and organize facts. Crystallized intelligence is factual knowledge. People can gain crystallized intelligence as they memorize new facts and are exposed to more knowledge. Fluid intelligence, on the other hand, is the ability to learn – and it decreases with age. Both types of intelligence, however, give you the ability to succeed.

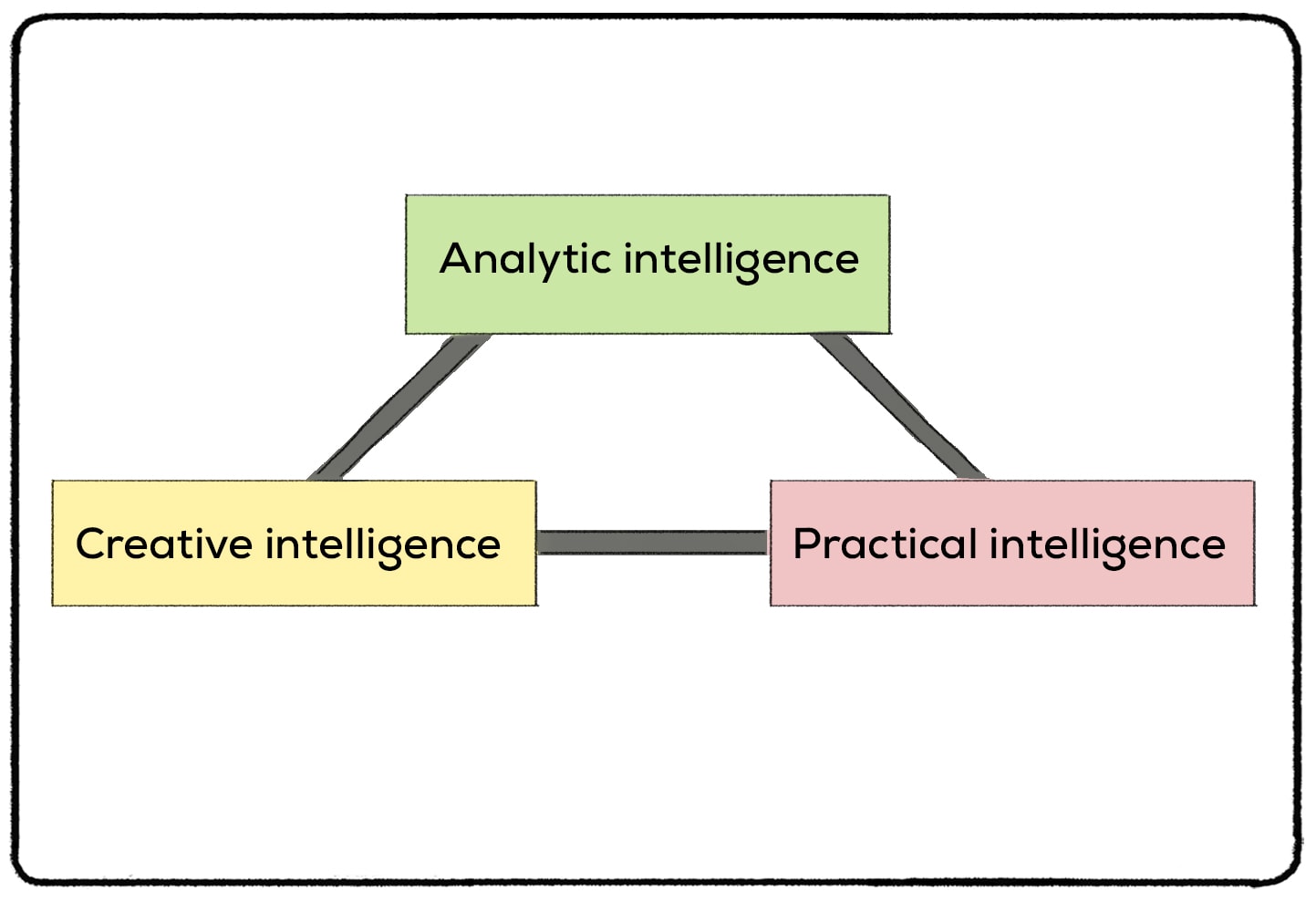

Practical Intelligence and the Triarchic Theory

Another popular way of categorizing intelligence is the Triarchic Theory, developed by Robert J. Sternberg. Rather than looking at the way you gain and store knowledge, the Triarchic Theory looks at different ways that people apply knowledge.

Fun facts about animals or the ability to solve a logic puzzle may not help you when you’re trying to read a map or network, but all of these skills can help you succeed in certain situations. That’s what the Triarchic Theory aims to recognize.

They separate intelligence into three categories.

Analytical Intelligence is the type of intelligence we have been discussing. It is the brain’s ability to interpret information and use that information to solve problems. This is the type of knowledge that is required to gain a high IQ score, but the Triarchic Theory argues that there is more to intelligence than just solving a math problem. A lot of people call this type of intelligence “book smarts.”

Practical intelligence is “an experience-based accumulation of skills and explicit knowledge as well as the ability to apply that knowledge to solve everyday problems.” This is the type of intelligence that you need to solve the problems of the world around you. In order to gain practical intelligence, you need to have knowledge of the area, culture, history, the list goes on and on.

Math won’t help you solve a dispute between two neighbors or settle a debate on how to solve the city’s traffic problems. These are both great examples of practical intelligence.

This type of intelligence is highly present in great leaders. In fact, Robert Sternberg said the definition of practical intelligence is to find the best fit between your personality strengths and the environment.

Creative Intelligence is the last type of intelligence in the Triarchic Theory. It describes the ability to adapt your knowledge and gather relevant knowledge that will help you adapt to new situations. While practical intelligence is often referred to as “street smarts,” I would argue that this type of intelligence is more suited to be called “street smarts.” If you are dropped in the middle of an unknown street in an unknown culture, you’re going to need some creative intelligence to get where you need to go and adapt to the new situation.

Does this cover all types of intelligence? Not according to the last theory we are going to cover. We’ll wrap this video up with information about the nine types of intelligence.

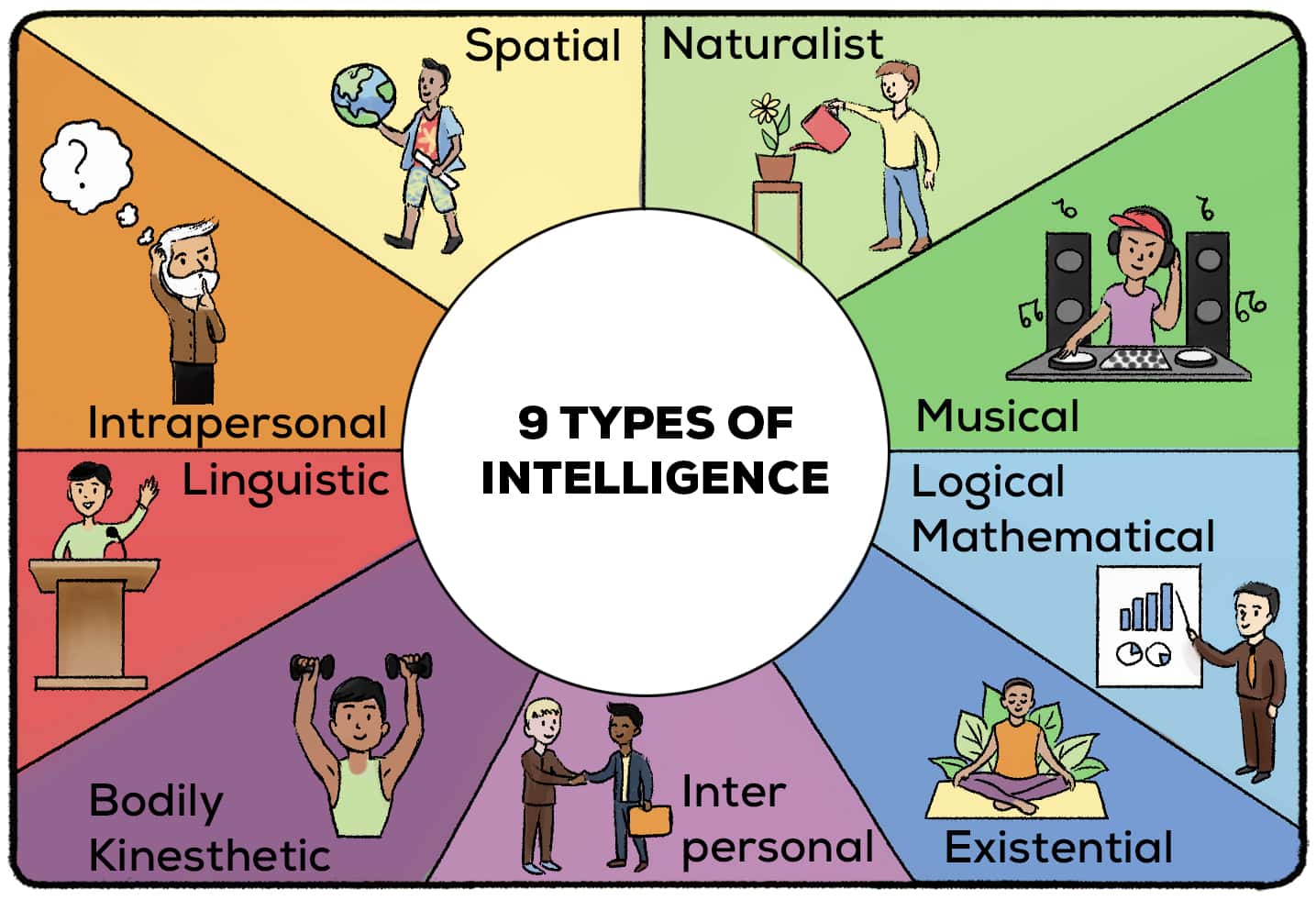

Gardener’s Nine Types of Intelligence

You probably thought this was going to be a video about the different types of intelligence: musical, kinesthetic, linguistic…right?

The “nine types of intelligence” describes a theory created by Howard Gardener. Howard Gardener is an American developmental psychologist who studied different types of intelligence throughout the second half of the 20th century. He believed that IQ tests and traditional ways of measuring intelligence only addressed linguistic and mathematical intelligence. There are many intelligent people who, while they may not excel on a math test or a reading assignment, display a deep understanding and knowledge in other areas.

He explained seven different types of intelligence in his 1983 book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Over the years, he’s added two other types of intelligence. While this theory is entirely separate from Kolb’s theories about different learning styles, we can connect the two and explore how people with different types of intelligence learn.

Gardener’s nine types of intelligence include:

- Musical-Rhythmic

- Visual-Spatial

- Linguistic

- Mathematical

- Interpersonal

- Intrapersonal

- Existential

- Naturalistic

- Body Kinesthetic

Controversy With the Nine Types of Intelligence

The nine types of intelligence rocked the world of educational psychology. In recent years, this theory has been disputed. Jordan Peterson, arguably one of the most famous psychologists in the world today, calls the nine types of intelligence theory “rubbish.” He argues that the the nine types of “intelligence” are just nine types of talents.

These critiques and arguments are still in development. It will be interesting to see where the world of educational psychology and measuring intelligence moves within the next few decades. Keep an eye out for new developments, and remember – even if you never scored high on an IQ test, there’s still a good chance that you hold some type of intelligence that will help you succeed.

Human intelligence is difficult to define. And when it comes to understanding exactly what intelligence is and how it works, there are a number of ways to go about it.

So, why is it so difficult to define intelligence? What is intelligence? How can we measure it? Is there more than one way to be intelligent?

We’re going to look at human intelligence from a number of angles to see if we can broaden our understanding of what intelligence is and how it can be accurately measured.

How Do You Define Intelligence?

So, what is intelligence?

Intelligence can be defined as the ability to acquire and use new knowledge and skills.

But what sort of knowledge? And what sort of skills? It turns out these variables have a greater influence on the way we interpret intelligence than we might realize.

Wisdom Vs Intelligence: What’s The Difference?

Is wisdom the same thing as intelligence? The terms are often used interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing.

When it comes to the wisdom vs intelligence debate, it’s important to recognize that these two concepts are quite different from one another.

Intelligence is the ability to assimilate and utilize new information.

Wisdom, on the other hand, is the ability to use past experiences to make informed decisions about the future.

What Is Intelligence According to Psychology?

Psychology is the scientific study of the mind. So, what is intelligence according to the field of psychology?

Psychology defines intelligence in a number of different ways. And that’s because there are many competing doctrines in the field of psychology.

It’s helpful to think of psychology as the trunk of a tree. Each branch that sprouts from the trunk finds its roots in the same principles and foundations. But each branch takes a different path toward the sunlight.

The way you define human intelligence in psychology depends entirely on the branch of psychology you use to define it.

Generally speaking, psychology recognizes human intelligence as the ability to acquire and synthesize new information.

What is the basic intelligence?

One of the earliest theories of intelligence was proposed by English psychologist, Charles Spearman, back in 1904.

This early theory focused on a single form of intelligence. Generalized intelligence, or “g factor,” was defined as the ability to perform certain cognitive tasks related to math, verbal fluency, spatial visualization, and memory. And it’s from this theory that the very first IQ tests were born.

What Does IQ Mean?

IQ stands for intelligence quotient. It was first coined by German psychologist, William Stern, back in 1912.

Stern used intelligence quotients as a way to standardize the scores he analyzed from intelligence tests.

Believe it or not, the very first IQ test was actually designed by French psychologist, Albert Binet. We know it today as the famous Stanford-Binet Scale.

What is the IQ of an average person?

Can IQ tests accurately measure intelligence? It’s a tough question to answer because while IQ tests are limited, they are capable of measuring certain cognitive abilities, including fluid reasoning, spatial processing, and deductive reasoning.

The average score for most IQ tests is 100.

But it’s important to keep in mind that your IQ score may not stay the same over the course of your life. In fact, the average IQ score by age can differ quite substantially.

What is the highest IQ possible?

100 is the average score for most, but there’s quite a spread in terms of the lowest and highest recorded IQ scores.

What’s the highest IQ possible to attain on an IQ test? Well, when examining high IQ scores, it’s helpful to look at the scores of the great minds we’ve witnessed throughout history.

Most theorists estimate Einstein’s IQ to have been between 160-190 points. Einstein never actually took an IQ test, so the best we have is an informed guess!

Garry Kasparov’s IQ was a reported 135 points, based on a test he took in 1988.

Dr. Stephen Hawking was also said to have had an impressively high IQ, with a similar range to Einstein: 160 – 190 points. But, just like Einstein, Hawking never actually took an IQ test. He wasn’t a fan of standardized intelligence tests and didn’t believe IQ scores were an accurate representation of human intelligence.

What is the lowest IQ ever recorded?

So, what about the opposite end of the spectrum? What’s the lowest IQ ever recorded?

While it may be theoretically possible to score 0 on an IQ test, no one has actually ever attained this score.

Generally speaking, any score that dips below 70 points is considered to be below average. Unfortunately, those with scores below 70 often have some form of mental or cognitive impairment.

Will a High IQ Make You More Successful?

Ever heard the saying: to have a high IQ to be successful? Some use it in terms of grasping certain concepts or learning new skills.

But is a high IQ really necessary to be successful?

Absolutely not.

Just look at Stephen Hawking. He possessed one of the most powerful, influential minds to date. And he couldn’t be bothered to take an IQ test.

The fact of the matter is, IQ tests are an outdated measure of intelligence. And while they are capable of measuring certain abilities, they are very limited.

There are all sorts of genius tests and genius clubs (like Mensa International) that propagate the value of traditional intelligence testing. But the truth is, we’ve come a long way from Spearman’s theory of generalized intelligence.

It’s not how smart you are, but how you are smart.

— Jim Kwik, trainer of Minvalley’s Superbrain Quest

How Can I Make Myself Smarter?

The recent science says that through neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, we can grow older but we can actually grow better. We can grow new brain cells and new connections and do things that are extraordinary.

— Jim Kwik, trainer of Minvalley’s Superbrain Quest

Increasing your intelligence has everything to do with the way you choose to define intelligence.

Did you know that emerging theories in human intelligence suggest we actually possess nine different types of intelligence? It’s true! And it’s quite the far cry from Spearman’s theory of a single generalized intelligence.

If you want to learn how to get smarter, it’s really all about improving your cognitive abilities. Increasing your brain power is a worthy endeavor and there are plenty of ways to go about it.

Here are a few ways you can exercise your abilities and grow your brain:

- Adopt a beginner’s mind

- Try the F.A.S.T method

- Exercise regularly

- Meditate

- Try some brain teasers

- Play strategy-based board games

- Teach others what you’ve learned

- Try a new sport or hobby

Becoming smarter is all about challenging your brain to try new things. The more you explore, the more adaptive your brain will become!

Stanford GSB professors suggest a reading list of articles and books related to the concept.

What does “intelligence” mean to you? | Illustration by Mike McQuade

The Summer 2017 issue of Stanford Business magazine explored the various meanings of “intelligence” in social, corporate, and transnational contexts. As part of that exploration, we asked several Stanford Graduate School of Business faculty members to suggest their favorite books, articles, videos, and podcasts on the subject. Here are their recommendations.

Jennifer Aaker

The Elements of Style, Fourth Edition, by William Strunk and E.B. White, 2000

Syntax & Sage: Reflections on Software and Nature, by Sep Kamvar, 2016

Bossypants, by Tina Fey, 2013

Lovett or Leave It, with Jon Lovett (podcast)

Matt Abrahams

Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, 2013

Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School, by John Medina, 2008

Federico Antoni

The Master Algorithm, How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World, by Pedro Domingos, 2015

Artificial Intelligence Playbook, aiplaybook.a16z.com (Andreessen Horowitz),2015

Einstein, His Life and Universe, by Walter Isaacson, 2017

Naomi Bagdonas

Moments of Impact, By Chris Ertel and Lisa Kay Solomon, 2014

Orbiting the Giant Hairball, by Gordon MacKenzie, 1998

Yes Please, by Amy Poehler, 2014

Christopher Krubert

“Paging HAL: What Will Happen When Artificial Intelligence Comes to Radiology?” by Dave Yeager, Radiology Today, May 2016

“Artificial Intelligence Framework for Simulating Clinical Decision-Making: A Markov Decision Process Approach,” by Casey C. Bennett and Kris Hauser, Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, January 2013

Jeffrey Pfeffer

“Fast Food and Financial Impatience: A Socioecological Approach,” by Sanford DeVoe, Julian House, and Chen-Bo Zhong, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, September 2013

“Time, Money, and Happiness: How Does Putting a Price on Time Affect Our Ability to Smell the Roses?” by Sanford E. DeVoe and Julian House, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, March 2012

“Thinking About Time as Money Decreases Environmental Behavior,” by Ashley V. Whillans and Elizabeth W. Dunn, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, March 2015

Andrzej Skrzypacz

“The Economist as Engineer: Game Theory, Experimentation, and Computation as Tools for Design Economics,” by Alvin E. Roth, Econometrica, July 2002

“Alvin E. Roth, Market Design: The Economist as Engineer,” National Academy of Sciences Research Briefings (video), August 14, 2014

Stanford economists Robert Wilson and Paul Milgrom awarded for their work in auction design, Golden Goose Awards, 2014

Adina Sterling

Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, by Philip E. Tetlock and Dan Gardner, 2015

How Innovation Really Works, by Anne Marie Knott, 2017

“Easier, Faster: The Next Steps for Deep Learning,” by Serdar Yegulalp, InfoWorld, June 7, 2017

1

a(1)

: the ability to learn or understand or to deal with new or trying situations : reason

also

: the skilled use of reason

(2)

: the ability to apply knowledge to manipulate one’s environment or to think abstractly as measured by objective criteria (such as tests)

b

Christian Science

: the basic eternal quality of divine Mind

2

b

: information concerning an enemy or possible enemy or an area

also

: an agency engaged in obtaining such information

4

: the ability to perform computer functions

5

a

: intelligent minds or mind

Synonyms

Example Sentences

She impressed us with her superior intelligence.

a person of average intelligence

gathering intelligence about a neighboring country’s activities

Recent Examples on the Web

The files include reports from across the U.S. intelligence community, including from the CIA, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, FISA court warrants and more.

—

However, the Department of Justice claimed in a statement that the evidence in the case shows that Cherkasov spent years illegally gathering information about American entities and passing it along to his handlers in Russia’s intelligence community, undermining U.S. national security.

—

The report does fault overly optimistic intelligence community assessments about the Afghan army’s willingness to fight, and says Biden followed military commanders’ recommendations for the pacing of the drawdown of US forces.

—

Still, the intelligence community has not been overly concerned about the information the balloon was able to gather, the person said.

—

In the Tiger franchise, Salman Khan plays Avinash Singh Rathore, AKA Tiger, who belongs to Indian intelligence agency RAW and Kaif plays Zoya Humaini from Pakistan’s ISI.

—

The order covered only spyware from commercial entities, not tools built by American intelligence agencies, which have similar in-house capabilities.

—

But does the world need Bond when even intelligence agency MI6 has replaced him with the elite new 007 agent, Nomi (Lashana Lynch)?

—

Still, there’s a range of intelligence in birds.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘intelligence.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle English, from Middle French, from Latin intelligentia, from intelligent-, intelligens intelligent

First Known Use

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a(1)

Time Traveler

The first known use of intelligence was

in the 14th century

Dictionary Entries Near intelligence

Cite this Entry

“Intelligence.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/intelligence. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on intelligence

Last Updated:

12 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged