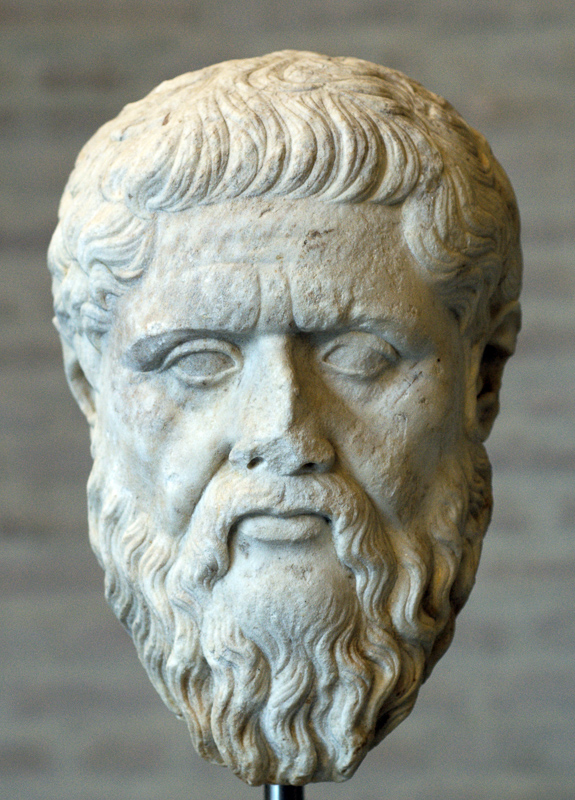

The philosopher Plato – Roman copy of a work by Silanion for the Academia in Athens (c. 370 BC)

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at the time. Today, the humanities are more frequently defined as any fields of study outside of natural sciences, social sciences, formal sciences (like mathematics) and applied sciences (or professional training).[1] They use methods that are primarily critical, or speculative, and have a significant historical element[2]—as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences;[2] yet, unlike the sciences, there is no general history of humanities as a distinct discipline in its own right.[further explanation needed][3]

The humanities include the studies of foreign languages, history, philosophy, language arts (literature, writing, oratory, rhetoric, poetry, etc.), performing arts (theater, music, dance, etc.), and visual arts (painting, sculpture, photography, filmmaking, etc.); culinary art or cookery is interdisciplinary and may be considered both a humanity and a science. Some definitions of the humanities include law and religion,[4] but these are not universally accepted. Although anthropology, archaeology, geography, linguistics, logic, and sociology share some similarities with the humanities, these are widely considered sciences; similarly economics, finance, and political science are not typically considered humanities.

Scholars in the humanities are called humanities scholars or sometimes humanists.[5] (The term humanist also describes the philosophical position of humanism, which antihumanist scholars in the humanities reject. Renaissance scholars and artists are also known as humanists.) Some secondary schools offer humanities classes usually consisting of literature, global studies, and art.

Human disciplines like history and language mainly use the comparative method[6] and comparative research. Other methods used in the humanities include hermeneutics, source criticism, esthetic interpretation, and speculative reason.

Fields[edit]

Classics[edit]

Bust of Homer, the most famous Greek poet

Classics, in the Western academic tradition, refers to the studies of the cultures of classical antiquity, namely Ancient Greek and Latin and the Ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Classical studies is considered one of the cornerstones of the humanities; however, its popularity declined during the 20th century. Nevertheless, the influence of classical ideas on many humanities disciplines, such as philosophy and literature, remains strong.[citation needed]

History[edit]

History is systematically collected information about the past. When used as the name of a field of study, history refers to the study and interpretation of the record of humans, societies, institutions, and any topic that has changed over time.

Traditionally, the study of history has been considered a part of the humanities. In modern academia, history can occasionally be classified as a social science, though this definition is contested.

Language[edit]

While the scientific study of language is known as linguistics and is generally considered a social science,[7] a natural science[8] or a cognitive science,[9] the study of languages is still central to the humanities. A good deal of twentieth- and twenty-first-century philosophy has been devoted to the analysis of language and to the question of whether, as Wittgenstein claimed, many of our philosophical confusions derive from the vocabulary we use; literary theory has explored the rhetorical, associative, and ordering features of language; and historical linguists have studied the development of languages across time. Literature, covering a variety of uses of language including prose forms (such as the novel), poetry and drama, also lies at the heart of the modern humanities curriculum. College-level programs in a foreign language usually include study of important works of the literature in that language, as well as the language itself.

Law[edit]

Main article: Law

In common parlance, law means a rule that (unlike a rule of ethics) is enforceable through institutions.[10] The study of law crosses the boundaries between the social sciences and humanities, depending on one’s view of research into its objectives and effects. Law is not always enforceable, especially in the international relations context. It has been defined as a «system of rules»,[11] as an «interpretive concept»[12] to achieve justice, as an «authority»[13] to mediate people’s interests, and even as «the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction».[14] However one likes to think of law, it is a completely central social institution. Legal policy incorporates the practical manifestation of thinking from almost every social science and discipline of the humanities. Laws are politics, because politicians create them. Law is philosophy, because moral and ethical persuasions shape their ideas. Law tells many of history’s stories, because statutes, case law and codifications build up over time. And law is economics, because any rule about contract, tort, property law, labour law, company law and many more can have long-lasting effects on how productivity is organised and the distribution of wealth. The noun law derives from the late Old English lagu, meaning something laid down or fixed,[15] and the adjective legal comes from the Latin word LEX.[16]

Literature[edit]

Literature is a term that does not have a universally accepted definition, but which has variably included all written work; writing that possesses literary merit; and language that foregrounds literariness, as opposed to ordinary language. Etymologically the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura «writing formed with letters», although some definitions include spoken or sung texts. Literature can be classified according to whether it is fiction or non-fiction, and whether it is poetry or prose; it can be further distinguished according to major forms such as the novel, short story or drama; and works are often categorised according to historical periods, or according to their adherence to certain aesthetic features or expectations (genre).

Philosophy[edit]

The works of Søren Kierkegaard overlap into many fields of the humanities, such as philosophy, literature, theology, music, and classical studies.

Philosophy—etymologically, the «love of wisdom»—is generally the study of problems concerning matters such as existence, knowledge, justification, truth, justice, right and wrong, beauty, validity, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing these issues by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on reasoned argument, rather than experiments (experimental philosophy being an exception).[17]

Philosophy used to be a very comprehensive term, including what have subsequently become separate disciplines, such as physics. (As Immanuel Kant noted, «Ancient Greek philosophy was divided into three sciences: physics, ethics, and logic.»)[18] Today, the main fields of philosophy are logic, ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Still, it continues to overlap with other disciplines. The field of semantics, for example, brings philosophy into contact with linguistics.

Since the early twentieth century, philosophy in English-speaking universities has moved away from the humanities and closer to the formal sciences, becoming much more analytic. Analytic philosophy is marked by emphasis on the use of logic and formal methods of reasoning, conceptual analysis, and the use of symbolic and/or mathematical logic, as contrasted with the Continental style of philosophy.[19] This method of inquiry is largely indebted to the work of philosophers such as Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Religion[edit]

[citation needed]

At present, we do not know of any people or tribe, either from history or the present day, which is (or was) altogether devoid of “religion.” Religion may be characterized with a community since humans are social animals.[20][21] Rituals are used to bound the community together.[22][23] Social animals require rules. Ethics is a requirement of society, but not a requirement of religion. Shinto, Daoism, and other folk or natural religions do not have ethical codes. The supernatural may or may not include deities since not all religions have deities. (Theravada Buddhism and Daoism)[24][citation needed][neutrality is disputed]. Magical thinking creates explanations not available for empirical verification. Stories or myths are narratives being both didactic and entertaining.[25] They are necessary for understanding the human predicament. Some other possible characteristics of religion are pollutions and purification,[26] the sacred and the profane,[27] sacred texts,[28] religious institutions and organizations,[29][30] and sacrifice and prayer. Some of the major problems that religions confront, and attempts to answer are chaos, suffering, evil,[31] and death.[32]

The non-founder religions are Hinduism, Shinto, and native or folk religions. Founder religions are Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Confucianism, Daoism, Mormonism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and the Baha’i faith. Religions must adapt and change through the generations because they must remain relevant to the adherents. When traditional religions fail to address new concerns, then new religions will emerge.

Performing arts[edit]

The performing arts differ from the visual arts in so far as the former uses the artist’s own body, face, and presence as a medium, and the latter uses materials such as clay, metal, or paint, which can be molded or transformed to create some art object. Performing arts include acrobatics, busking, comedy, dance, film, magic, music, opera, juggling, marching arts, such as brass bands, and theatre.

Artists who participate in these arts in front of an audience are called performers, including actors, comedians, dancers, musicians, and singers. Performing arts are also supported by workers in related fields, such as songwriting and stagecraft. Performers often adapt their appearance, such as with costumes and stage makeup, etc. There is also a specialized form of fine art in which the artists perform their work live to an audience. This is called Performance art. Most performance art also involves some form of plastic art, perhaps in the creation of props. Dance was often referred to as a plastic art during the Modern dance era.

Musicology[edit]

Concert in the Mozarteum, Salzburg

Musicology as an academic discipline can take a number of different paths, including historical musicology, music literature, ethnomusicology and music theory. Undergraduate music majors generally take courses in all of these areas, while graduate students focus on a particular path. In the liberal arts tradition, musicology is also used to broaden skills of non-musicians by teaching skills such as concentration and listening.

Theatre[edit]

Theatre (or theater) (Greek «theatron», θέατρον) is the branch of the performing arts concerned with acting out stories in front of an audience using combinations of speech, gesture, music, dance, sound and spectacle — indeed any one or more elements of the other performing arts. In addition to the standard narrative dialogue style, theatre takes such forms as opera, ballet, mime, kabuki, classical Indian dance, Chinese opera, mummers’ plays, and pantomime.

Dance[edit]

Dance (from Old French dancier, perhaps from Frankish) generally refers to human movement either used as a form of expression or presented in a social, spiritual or performance setting. Dance is also used to describe methods of non-verbal communication (see body language) between humans or animals (bee dance, mating dance), and motion in inanimate objects (the leaves danced in the wind). Choreography is the art of creating dances, and the person who does this is called a choreographer.

Definitions of what constitutes dance are dependent on social, cultural, aesthetic, artistic, and moral constraints and range from functional movement (such as Folk dance) to codified, virtuoso techniques such as ballet.

Visual arts[edit]

History of visual arts[edit]

Quatrain on Heavenly Mountain by Emperor Gaozong (1107–1187) of Song Dynasty; fan mounted as album leaf on silk, four columns in cursive script.

The great traditions in art have a foundation in the art of one of the ancient civilizations, such as Ancient Japan, Greece and Rome, China, India, Greater Nepal, Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica.

Ancient Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of equivalent skills to show musculature, poise, beauty and anatomically correct proportions. Ancient Roman art depicted gods as idealized humans, shown with characteristic distinguishing features (e.g., Zeus’ thunderbolt).

In Byzantine and Gothic art of the Middle Ages, the dominance of the church insisted on the expression of biblical and not material truths. The Renaissance saw the return to valuation of the material world, and this shift is reflected in art forms, which show the corporeality of the human body, and the three-dimensional reality of landscape.

Eastern art has generally worked in a style akin to Western medieval art, namely a concentration on surface patterning and local colour (meaning the plain colour of an object, such as basic red for a red robe, rather than the modulations of that colour brought about by light, shade and reflection). A characteristic of this style is that the local colour is often defined by an outline (a contemporary equivalent is the cartoon). This is evident in, for example, the art of India, Tibet and Japan.

Religious Islamic art forbids iconography, and expresses religious ideas through geometry instead. The physical and rational certainties depicted by the 19th-century Enlightenment were shattered not only by new discoveries of relativity by Einstein[33] and of unseen psychology by Freud,[34] but also by unprecedented technological development. Increasing global interaction during this time saw an equivalent influence of other cultures into Western art.

Media types[edit]

Drawing[edit]

Drawing is a means of making a picture, using any of a wide variety of tools and techniques. It generally involves making marks on a surface by applying pressure from a tool, or moving a tool across a surface. Common tools are graphite pencils, pen and ink, inked brushes, wax color pencils, crayons, charcoals, pastels, and markers. Digital tools that simulate the effects of these are also used. The main techniques used in drawing are: line drawing, hatching, crosshatching, random hatching, scribbling, stippling, and blending. A computer aided designer who excels in technical drawing is referred to as a draftsman or draughtsman.

Painting[edit]

Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, is one of the most recognizable artistic paintings in the world.

Painting taken literally is the practice of applying pigment suspended in a carrier (or medium) and a binding agent (a glue) to a surface (support) such as paper, canvas or a wall. However, when used in an artistic sense it means the use of this activity in combination with drawing, composition and other aesthetic considerations in order to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner. Painting is also used to express spiritual motifs and ideas; sites of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to The Sistine Chapel to the human body itself.

Colour is highly subjective, but has observable psychological effects, although these can differ from one culture to the next. Black is associated with mourning in the West, but elsewhere white may be. Some painters, theoreticians, writers and scientists, including Goethe, Kandinsky, Isaac Newton, have written their own colour theories. Moreover, the use of language is only a generalization for a colour equivalent. The word «red», for example, can cover a wide range of variations on the pure red of the spectrum. There is not a formalized register of different colours in the way that there is agreement on different notes in music, such as C or C# in music, although the Pantone system is widely used in the printing and design industry for this purpose.

Modern artists have extended the practice of painting considerably to include, for example, collage. This began with cubism and is not painting in strict sense. Some modern painters incorporate different materials such as sand, cement, straw or wood for their texture. Examples of this are the works of Jean Dubuffet or Anselm Kiefer. Modern and contemporary art has moved away from the historic value of craft in favour of concept (conceptual art); this has led some e.g. Joseph Kosuth to say that painting, as a serious art form, is dead, although this has not deterred the majority of artists from continuing to practise it either as whole or part of their work.

Sculpture involves creating three-dimensional forms out of various materials. These typically include moldable substances like clay and metal but may also extend to material that is cut or shaved down to the desired form, like stone and wood.

Origin of the term[edit]

The word «humanities» is derived from the Renaissance Latin expression studia humanitatis, or «study of humanitas» (a classical Latin word meaning—in addition to «humanity»—»culture, refinement, education» and, specifically, an «education befitting a cultivated man»). In its usage in the early 15th century, the studia humanitatis was a course of studies that consisted of grammar, poetry, rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy, primarily derived from the study of Latin and Greek classics. The word humanitas also gave rise to the Renaissance Italian neologism umanisti, whence «humanist», «Renaissance humanism».[35]

History[edit]

In the West, the history of the humanities can be traced to ancient Greece, as the basis of a broad education for citizens.[36] During Roman times, the concept of the seven liberal arts evolved, involving grammar, rhetoric and logic (the trivium), along with arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music (the quadrivium).[37] These subjects formed the bulk of medieval education, with the emphasis being on the humanities as skills or «ways of doing».

A major shift occurred with the Renaissance humanism of the fifteenth century, when the humanities began to be regarded as subjects to study rather than practice, with a corresponding shift away from traditional fields into areas such as literature and history. In the 20th century, this view was in turn challenged by the postmodernist movement, which sought to redefine the humanities in more egalitarian terms suitable for a democratic society since the Greek and Roman societies in which the humanities originated were not at all democratic.[38]

Today[edit]

Education and employment[edit]

For many decades, there has been a growing public perception that a humanities education inadequately prepares graduates for employment.[39] The common belief is that graduates from such programs face underemployment and incomes too low for a humanities education to be worth the investment.[40]

In fact, humanities graduates find employment in a wide variety of management and professional occupations. In Britain, for example, over 11,000 humanities majors found employment in the following occupations:

- Education (25.8%)

- Management (19.8%)

- Media/Literature/Arts (11.4%)

- Law (11.3%)

- Finance (10.4%)

- Civil service (5.8%)

- Not-for-profit (5.2%)

- Marketing (2.3%)

- Medicine (1.7%)

- Other (6.4%)[41]

Many humanities graduates finish university with no career goals in mind.[42][43] Consequently, many spend the first few years after graduation deciding what to do next, resulting in lower incomes at the start of their career; meanwhile, graduates from career-oriented programs experience more rapid entry into the labour market. However, usually within five years of graduation, humanities graduates find an occupation or career path that appeals to them.[44][45]

There is empirical evidence that graduates from humanities programs earn less than graduates from other university programs.[46][47][48] However, the empirical evidence also shows that humanities graduates still earn notably higher incomes than workers with no postsecondary education, and have job satisfaction levels comparable to their peers from other fields.[49] Humanities graduates also earn more as their careers progress; ten years after graduation, the income difference between humanities graduates and graduates from other university programs is no longer statistically significant.[42] Humanities graduates can boost their incomes if they obtain advanced or professional degrees.[50][51]

In the United States[edit]

The Humanities Indicators[edit]

The Humanities Indicators, unveiled in 2009 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, are the first comprehensive compilation of data about the humanities in the United States, providing scholars, policymakers and the public with detailed information on humanities education from primary to higher education, the humanities workforce, humanities funding and research, and public humanities activities.[52][53] Modeled after the National Science Board’s Science and Engineering Indicators, the Humanities Indicators are a source of reliable benchmarks to guide analysis of the state of the humanities in the United States.

If «The STEM Crisis Is a Myth»,[54] statements about a «crisis» in the humanities are also misleading and ignore data of the sort collected by the Humanities Indicators.[55][56]

The Humanities in American Life[edit]

The 1980 United States Rockefeller Commission on the Humanities described the humanities in its report, The Humanities in American Life:

Through the humanities we reflect on the fundamental question: What does it mean to be human? The humanities offer clues but never a complete answer. They reveal how people have tried to make moral, spiritual, and intellectual sense of a world where irrationality, despair, loneliness, and death are as conspicuous as birth, friendship, hope, and reason.

As a major[edit]

In 1950, a little over 1 percent of 22-year-olds in the United States had earned a humanities degrees (defined as a degree in English, language, history, philosophy); in 2010, this had doubled to about 2 and a half percent.[57] In part, this is because there was an overall rise in the number of Americans who have any kind of college degree. (In 1940, 4.6 percent had a four-year degree; in 2016, 33.4 percent had one.)[58] As a percentage of the type of degrees awarded, however, the humanities seem to be declining. Harvard University provides one example. In 1954, 36 percent of Harvard undergraduates majored in the humanities, but in 2012, only 20 percent took that course of study.[59] Professor Benjamin Schmidt of Northeastern University has documented that between 1990 and 2008, degrees in English, history, foreign languages, and philosophy have decreased from 8 percent to just under 5 percent of all U.S. college degrees.[60]

In liberal arts education[edit]

The Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences 2013 report The Heart of the Matter supports the notion of a broad «liberal arts education», which includes study in disciplines from the natural sciences to the arts as well as the humanities.[61][62]

Many colleges provide such an education; some require it. The University of Chicago and Columbia University were among the first schools to require an extensive core curriculum in philosophy, literature, and the arts for all students.[63] Other colleges with nationally recognized, mandatory programs in the liberal arts are Fordham University, St. John’s College, Saint Anselm College and Providence College. Prominent proponents of liberal arts in the United States have included Mortimer J. Adler[64] and E. D. Hirsch, Jr.

In the digital age[edit]

Researchers in the humanities have developed numerous large- and small-scale digital corporations, such as digitized collections of historical texts, along with the digital tools and methods to analyze them. Their aim is both to uncover new knowledge about corpora and to visualize research data in new and revealing ways. Much of this activity occurs in a field called the digital humanities.

STEM[edit]

Politicians in the United States currently espouse a need for increased funding of the STEM fields, science, technology, engineering, mathematics.[65] Federal funding represents a much smaller fraction of funding for humanities than other fields such as STEM or medicine.[66] The result was a decline of quality in both college and pre-college education in the humanities field.[66]

Three-term Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards acknowledged the importance of the humanities in a 2014 video address[67] to the academic conference,[68] Revolutions in Eighteenth-Century Sociability. Edwards said:

- Without the humanities to teach us how history has succeeded or failed in directing the fruits of technology and science to the betterment of our tribe of homo sapiens, without the humanities to teach us how to frame the discussion and to properly debate the uses-and the costs-of technology, without the humanities to teach us how to safely debate how to create a more just society with our fellow man and woman, technology and science would eventually default to the ownership of—and misuse by—the most influential, the most powerful, the most feared among us.[69]

In Europe[edit]

The value of the humanities debate[edit]

The contemporary debate in the field of critical university studies centers around the declining value of the humanities.[70][71] As in America, there is a perceived decline in interest within higher education policy in research that is qualitative and does not produce marketable products. This threat can be seen in a variety of forms across Europe, but much critical attention has been given to the field of research assessment in particular. For example, the UK [Research Excellence Framework] has been subject to criticism due to its assessment criteria from across the humanities, and indeed, the social sciences.[72] In particular, the notion of «impact» has generated significant debate.[73]

Philosophical history[edit]

Citizenship and self-reflection[edit]

Since the late 19th century, a central justification for the humanities has been that it aids and encourages self-reflection—a self-reflection that, in turn, helps develop personal consciousness or an active sense of civic duty.

Wilhelm Dilthey and Hans-Georg Gadamer centered the humanities’ attempt to distinguish itself from the natural sciences in humankind’s urge to understand its own experiences. This understanding, they claimed, ties like-minded people from similar cultural backgrounds together and provides a sense of cultural continuity with the philosophical past.[74]

Scholars in the late 20th and early 21st centuries extended that «narrative imagination»[75] to the ability to understand the records of lived experiences outside of one’s own individual social and cultural context. Through that narrative imagination, it is claimed, humanities scholars and students develop a conscience more suited to the multicultural world we live in.[76] That conscience might take the form of a passive one that allows more effective self-reflection[77] or extend into active empathy that facilitates the dispensation of civic duties a responsible world citizen must engage in.[76] There is disagreement, however, on the level of influence humanities study can have on an individual and whether or not the understanding produced in humanistic enterprise can guarantee an «identifiable positive effect on people.»[78]

Humanistic theories and practices[edit]

There are three major branches of knowledge: natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities. Technology is the practical extension of the natural sciences, as politics is the extension of the social sciences. Similarly, the humanities have their own practical extension, sometimes called «transformative humanities» (transhumanities) or «culturonics» (Mikhail Epstein’s term):

- Nature – natural sciences – technology – transformation of nature

- Society – social sciences – politics – transformation of society

- Culture – human sciences – culturonics – transformation of culture[79]

Technology, politics and culturonics are designed to transform what their respective disciplines study[dubious – discuss]: nature, society, and culture. The field of transformative humanities includes various practicies and technologies, for example, language planning, the construction of new languages, like Esperanto, and invention of new artistic and literary genres and movements in the genre of manifesto, like Romanticism, Symbolism, or Surrealism. Humanistic invention in the sphere of culture, as a practice complementary to scholarship, is an important aspect of the humanities.

Truth and meaning[edit]

The divide between humanistic study and natural sciences informs arguments of meaning in humanities as well. What distinguishes the humanities from the natural sciences is not a certain subject matter, but rather the mode of approach to any question. Humanities focuses on understanding meaning, purpose, and goals and furthers the appreciation of singular historical and social phenomena—an interpretive method of finding «truth»—rather than explaining the causality of events or uncovering the truth of the natural world.[80] Apart from its societal application, narrative imagination is an important tool in the (re)production of understood meaning in history, culture and literature.

Imagination, as part of the tool kit of artists or scholars, helps create meaning that invokes a response from an audience. Since a humanities scholar is always within the nexus of lived experiences, no «absolute» knowledge is theoretically possible; knowledge is instead a ceaseless procedure of inventing and reinventing the context a text is read in. Poststructuralism has problematized an approach to the humanistic study based on questions of meaning, intentionality, and authorship.[dubious – discuss] In the wake of the death of the author proclaimed by Roland Barthes, various theoretical currents such as deconstruction and discourse analysis seek to expose the ideologies and rhetoric operative in producing both the purportedly meaningful objects and the hermeneutic subjects of humanistic study. This exposure has opened up the interpretive structures of the humanities to criticism that humanities scholarship is «unscientific» and therefore unfit for inclusion in modern university curricula because of the very nature of its changing contextual meaning.[dubious – discuss]

Pleasure, the pursuit of knowledge and scholarship[edit]

Some, like Stanley Fish, have claimed that the humanities can defend themselves best by refusing to make any claims of utility.[81] (Fish may well be thinking primarily of literary study, rather than history and philosophy.) Any attempt to justify the humanities in terms of outside benefits such as social usefulness (say increased productivity) or in terms of ennobling effects on the individual (such as greater wisdom or diminished prejudice) is ungrounded, according to Fish, and simply places impossible demands on the relevant academic departments. Furthermore, critical thinking, while arguably a result of humanistic training, can be acquired in other contexts.[82] And the humanities do not even provide any more the kind of social cachet (what sociologists sometimes call «cultural capital») that was helpful to succeed in Western society before the age of mass education following World War II.

Instead, scholars like Fish suggest that the humanities offer a unique kind of pleasure, a pleasure based on the common pursuit of knowledge (even if it is only disciplinary knowledge). Such pleasure contrasts with the increasing privatization of leisure and instant gratification characteristic of Western culture; it thus meets Jürgen Habermas’ requirements for the disregard of social status and rational problematization of previously unquestioned areas necessary for an endeavor which takes place in the bourgeois public sphere. In this argument, then, only the academic pursuit of pleasure can provide a link between the private and the public realm in modern Western consumer society and strengthen that public sphere that, according to many theorists,[who?] is the foundation for modern democracy.[citation needed]

Others, like Mark Bauerlein, argue that professors in the humanities have increasingly abandoned proven methods of epistemology (I care only about the quality of your arguments, not your conclusions.) in favor of indoctrination (I care only about your conclusions, not the quality of your arguments.). The result is that professors and their students adhere rigidly to a limited set of viewpoints, and have little interest in, or understanding of, opposing viewpoints. Once they obtain this intellectual self-satisfaction, persistent lapses in learning, research, and evaluation are common.[83]

Romanticization and rejection[edit]

Implicit in many of these arguments supporting the humanities are the makings of arguments against public support of the humanities. Joseph Carroll asserts that we live in a changing world, a world where «cultural capital» is replaced with scientific literacy, and in which the romantic notion of a Renaissance humanities scholar is obsolete. Such arguments appeal to judgments and anxieties about the essential uselessness of the humanities, especially in an age when it is seemingly vitally important for scholars of literature, history and the arts to engage in «collaborative work with experimental scientists or even simply to make «intelligent use of the findings from empirical science.»[84]

Despite many humanities based arguments against the humanities some within the exact sciences have called for their return. In 2017, Science popularizer Bill Nye retracted previous claims about the supposed ‘uselessness’ of philosophy. As Bill Nye states, “People allude to Socrates and Plato and Aristotle all the time, and I think many of us who make those references don’t have a solid grounding,” he said. “It’s good to know the history of philosophy.”[85] Scholars, such as biologist Scott F. Gilbert, make the claim that it is in fact the increasing predominance, leading to exclusivity, of scientific ways of thinking that need to be tempered by historical and social context. Gilbert worries that the commercialization that may be inherent in some ways of conceiving science (pursuit of funding, academic prestige etc.) need to be examined externally. Gilbert argues «First of all, there is a very successful alternative to science as a commercialized march to “progress.” This is the approach taken by the liberal arts college, a model that takes pride in seeing science in context and in integrating science with the humanities and social sciences.»[86]

See also[edit]

- Discourse analysis

- Outline of the humanities (humanities topics)

- Great Books

- Great Books programs in Canada

- Liberal arts

- Social sciences

- Humanities, arts, and social sciences

- Human science

- The Two Cultures

- List of academic disciplines

- Public humanities

- STEAM fields

- Tinbergen’s four questions

- Environmental humanities

References[edit]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 3rd Edition.

- ^ a b «Humanity» 2.b, Oxford English Dictionary 3rd Ed. (2003)

- ^ Bod, Rens (2013-11-14). A New History of the Humanities: The Search for Principles and Patterns from Antiquity to the Present. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665211.001.0001. ISBN 9780199665211.

- ^ Stanford University, Stanford University (16 December 2013). «What are the Humanities». Stanford Humanities Center. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ «Humanist» Oxford English Dictionary. Oed.com Archived 2020-06-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wallace and Gach (2008) p.28 Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Social Science Majors, University of Saskatchewan». Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ^ Boeckx, Cedric. «Language as a Natural Object; Linguistics as a Natural Science» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-23.

- ^ Thagard, Paul, Cognitive Science Archived 2018-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- ^ Robertson, Geoffrey (2006). Crimes Against Humanity. Penguin. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-14-102463-9.

- ^ Hart, H. L. A. (1961). The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-876122-8.

- ^ Dworkin, Ronald (1986). Law’s Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-51836-5.

- ^ Raz, Joseph (1979). The Authority of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-956268-7.

- ^ Austin, John (1831). The Providence of Jurisprudence Determined.

- ^ «Etymonline Dictionary». Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ «Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary». Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ Thomas Nagel (1987). What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, the first line.

- ^ See, e.g., Brian Leiter [1] «‘Analytic’ philosophy today names a style of doing philosophy, not a philosophical program or a set of substantive views. Analytic philosophers, crudely speaking, aim for argumentative clarity and precision; draw freely on the tools of logic; and often identify, professionally and intellectually, more closely with the sciences and mathematics than with the humanities.»

- ^ Aristotle (1941). Politica. New York: Oxford. pp. 1253a.

- ^ Berger, Peter (1969). The Sacred Canopy. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-0385073059.

- ^ Stephenson, Barry (2015). Rituals. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0199943524.

- ^ Bell, Catherine (2009). Ritual. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0199735105.

- ^ Hood, Bruce (2010). The Science of Superstition. New York: HarperOne. pp. xii. ISBN 978-0061452659.

- ^ Segal, Robert (2015). Myth. New York: Oxford. p. 3. ISBN 978-0198724704.

- ^ Douglas, Mary (2002). Purity and Danger. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415289955.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1959). The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Harvest.

- ^ Coward, Harold (1988). Sacred Word and Sacred Text. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. ISBN 978-0883446041.

- ^ Berger, Peter (1990). The Sacred Canopy. New York: Anchor. ISBN 978-0385073059.

- ^ McGuire, Meredith (2002). Religion: The Social Context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-54126-7.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph (1989). The Problem of Evil in the Western Tradition. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-5104-6.

- ^ Becker, Ernest (2009), The denial of death, Macmillan, pp. ix, ISBN 978-0029023105

- ^

Turney, Jon (2003-09-06). «Does time fly?». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-05-01. - ^

«Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Dada». www.fordham.edu. Retrieved 2008-05-01. - ^ «humanism.» Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 11 Apr. 2012. [2] Archived 2015-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bod, Rens; A New History of the Humanities, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014.

- ^ Levi, Albert W.; The Humanities Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1970.

- ^ Walling, Donovan R.; Under Construction: The Role of the Arts and Humanities in Postmodern Schooling Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Indiana, 1997. Humanities comes from human

- ^ Hersh, Richard H. (1997-03-01). «Intention and Perceptions A National Survey of Public Attitudes Toward Liberal Arts Education». Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning. 29 (2): 16–23. doi:10.1080/00091389709603100. ISSN 0009-1383.

- ^ Williams, Mary Elizabeth (27 March 2014). «Hooray for «worthless» education!». Salon. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ Kreager, Philip. «Humanities graduates and the British economy: The hidden impact» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-06.

- ^ a b Adamuti-Trache, Maria; et al. (2006). «The Labour Market Value of Liberal Arts and Applied Education Programs: Evidence from British Columbia». Canadian Journal of Higher Education. 36 (2): 49–74. doi:10.47678/cjhe.v36i2.183539.

- ^ Thought Vlogger (2018-08-06), What can you do with a humanities degree?, archived from the original on 2021-10-30, retrieved 2018-08-07

- ^ Koc, Edwin W (2010). «The Liberal Arts Graduate College Hiring Market». National Association of Colleges and Employers: 14–21.

- ^ «Ten Years After College: Comparing the Employment Experiences of 1992–93 Bachelor’s Degree Recipients With Academic and Career Oriented Majors» (PDF).

- ^ «The Cumulative Earnings of Postsecondary Graduates Over 20 Years: Results by Field of Study». 28 October 2014.

- ^ «Earnings of Humanities Majors with a Terminal Bachelor’s Degree».

- ^ «Career earnings by college major».

- ^ The State of the Humanities 2018: Graduates in the Workforce & Beyond. Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2018. pp. 5–6, 12, 19.

- ^ «Boost in Median Annual Earnings Associated with Obtaining an Advanced Degree, by Gender and Field of Undergraduate Degree».

- ^ «Earnings of Humanities Majors with an Advanced Degree».

- ^ «American Academy of Arts & Sciences». Amacad.org. 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ «Humanities Indicators». Humanities Indicators. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ Charette, Robert N. (2013-08-30). «The STEM Crisis Is a Myth – IEEE Spectrum». Spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ «Humanities Scholars See Declining Prestige, Not a Lack of Interest». Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ «Debating the State of the Humanities». Archived from the original on 2016-01-02. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ Schmidt, Ben (10 June 2013). «A Crisis in the Humanities? (10 June 2013)». The Chronicle. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Reid (4 March 2017). «Census: More Americans have college degrees than ever before». The Hill. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (18 June 2013). «Humanities Committee Sounds an Alarm». New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Smith, Noah (14 August 2018). «The Great Recession Never Ended for College Humanities». Bloomberg.com.

- ^ «Humanities, social sciences critical to our future». USA Today. Archived from the original on 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ «Colbert Report: The humanities do pay». Archived from the original on 2013-09-09. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ Louis Menand, «The Problem of General Education,» in The Marketplace of Ideas (W. W. Norton, 2010), especially pp. 32–43.

- ^ Adler, Mortimer J.; «A Guidebook to Learning: For the Lifelong Pursuit of Wisdom»

- ^ «Whitehouse.gov». Archived from the original on 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ a b America Is Raising A Generation Of Kids Who Can’t Think Or Write Clearly, Business Insider Archived 2014-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «YouTube». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2015-05-17. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ Scedhs2014.uqam.ca

- ^ «Academia.edu». Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ Stefan Collini, «What Are Universities For?» (Penguin 2012)

- ^ Helen Small, «The Value of the Humanities»(Oxford University Press 2013)

- ^ Ochsner, Michael; Hug, Sven; Galleron, Ioana (2017). «The future of research assessment in the humanities: Bottom-up assessment procedures». Palgrave Communications. 3. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.20.

- ^ Bulaitis, Zoe (31 October 2017). «Measuring impact in the humanities: Learning from accountability and economics in a contemporary history of cultural value». Palgrave Communications. 3 (1). doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0002-7.

- ^ Dilthey, Wilhelm. The Formation of the Historical World in the Human Sciences, 103.

- ^ von Wright, Moira. «Narrative imagination and taking the perspective of others,» Studies in Philosophy and Education 21, 4–5 (July, 2002), 407–416.

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Martha. Cultivating Humanity.

- ^ Harpham, Geoffrey (2005). «Beneath and Beyond the Crisis of the Humanities». New Literary History. 36: 21–36. doi:10.1353/nlh.2005.0022. S2CID 144177169.

- ^ Harpham, 31.

- ^ Mikhail Epstein. The Transformative Humanities: A Manifesto. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012, p.12

- ^ Dilthey, Wilhelm. The Formation of the Historical World in the Human Sciences, 103.

- ^ Fish, Stanley, The New York Times Archived 2009-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alan Liu, Laws of Cool, 2004 Archived 2013-08-28 at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ Bauerlein, Mark (13 November 2014). «Theory and the Humanities, Once More». Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Jay treats it [theory] as transformative progress, but it impressed us as hack philosophizing, amateur social science, superficial learning, or just plain gamesmanship.

- ^ «»Theory,» Anti-Theory, and Empirical Criticism,» Biopoetics: Evolutionary Explorations in the Arts, Brett Cooke and Frederick Turner, eds., Lexington, Kentucky: ICUS Books, 1999, pp. 144–145. 152.

- ^ quoted from Olivia Goldhill, https://qz.com/960303/bill-nye-on-philosophy-the-science-guy-says-he-has-changed-his-mind Archived 2019-12-10 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- ^ Gilbert, S. F. (n.d.). ‘Health Fetishism among the Nacirema: A fugue on Jenny Reardon’s The Postgenomic Condition: Ethics, Justice, and Knowledge after the Genome (Chicago University Press, 2017) and Isabelle Stengers’ Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science (Polity Press, 2018). Retrieved from https://ojs.uniroma1.it/index.php/Organisms/article/view/14346/14050.’ Archived 2019-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

- Society for the History of the Humanities

- Institute for Comparative Research in Human and Social Sciences (ICR) – Japan

- The American Academy of Arts and Sciences – US

- Humanities Indicators – US

- National Humanities Center – US

- The Humanities Association – UK

- National Humanities Alliance

- National Endowment for the Humanities – US

- Australian Academy of the Humanities

- National

- American Academy Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences Archived 2017-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- «Games and Historical Narratives» by Jeremy Antley – Journal of Digital Humanities

- Film about the Value of the Humanities

Humanities, those branches of knowledge that concern themselves with human beings and their culture or with analytic and critical methods of inquiry derived from an appreciation of human values and of the unique ability of the human spirit to express itself.

What do we call the methodology scholars use to analyze and interpret the works of others?

The process by which scholars analyze and interpret the works of others is known as. critical thinking.

How do you identify a methodology?

The methodology section or methods section tells you how the author(s) went about doing their research. It should let you know a) what method they used to gather data (survey, interviews, experiments, etc.), why they chose this method, and what the limitations are to this method.

What does methodology mean?

1 : a body of methods, rules, and postulates employed by a discipline : a particular procedure or set of procedures demonstrating library research methodology the issue is massive revision of teaching methodology— Bob Samples.

What are examples of methodology?

What are the main data collection methods?

- Interviews (which can be unstructured, semi-structured or structured)

- Focus groups and group interviews.

- Surveys (online or physical surveys)

- Observations.

- Documents and records.

- Case studies.

What is the synonym of modus operandi?

What is another word for modus operandi?

| methodology | method |

|---|---|

| praxis | M.O. |

| workings | course of action |

| plan of action | method of working |

| modus vivendi | manner of working |

What does MO stand for?

Modus operandi

What does modus mean in English?

1 : the immediate manner in which property may be acquired (as by occupation or prescription) or the particular tenure by which it is held. 2 plural moduses : a customary mode of tithing by composition instead of by payment in kind still took his tithe pig or his modus— George Eliot.

What does Mo mean in slang?

modus operandi

Is Mo a real word?

Yes, mo is in the scrabble dictionary.

What does 1 Mo mean on Snapchat?

In My Opinion

What does MMO stand for?

Massively multiplayer online game

What does IMK mean?

In My Knowledge

What is Momo short for?

Summary of Key Points

| MOMO | |

|---|---|

| Definition: | Idiot or irritating person |

| Type: | Cyber Term |

| Guessability: | 3: Guessable |

| Typical Users: | Adults and Teenagers |

What do we call Momo in English?

The name momo spread to Tibet, and Nepal and usually now refers to filled buns or dumplings. Momo is the colloquial form of the Tibetan word “mog mog”.

What is Momo Korean?

Momo Hirai (Hangul: 히라이 모모, Japanese: 平井もも/ひらいもも Hirai Momo), better known as Momo (Hangul: 모모), is a Japanese singer and dancer, active in South Korea. She is the third oldest member of the K-pop girl group, Twice, as the main dancer, vocalist, and sub-rapper.

Are Momo and Heechul still dating 2020?

In a ‘Knowing Bros’ episode, Heechul was asked if he is dating Momo where he reportedly denied the claims. In 2020, after SJ confirmed, JYP also spoke about the couple and stated, “Hello, this is JYP Entertainment. We are confirming that Heechul and Momo are in a relationship.

Does Momo have a boyfriend?

Two K-pop stars have officially announced that they’re dating: TWICE member Momo, and Heechul from Super Junior.

How old is Jihyo?

24 years (February 1, 1997)

Definition:

Humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are largely analytical, critical, or speculative. As a group, the humanities include the study of history, literature, philosophy, religion, and language.

Humanities are distinguished from the sciences because they use different methods of inquiry. while the sciences rely on experimentation and observation, the humanities rely on interpretation and analysis. This means that the humanities are better suited to answering questions about meaning, value, and identity.

The humanities are valuable because they help us to understand who we are and where we came from. They provide us with a way to make sense of our lives and our world. The humanities can also help us to find answers to some of life’s most difficult questions.

History of Humanities

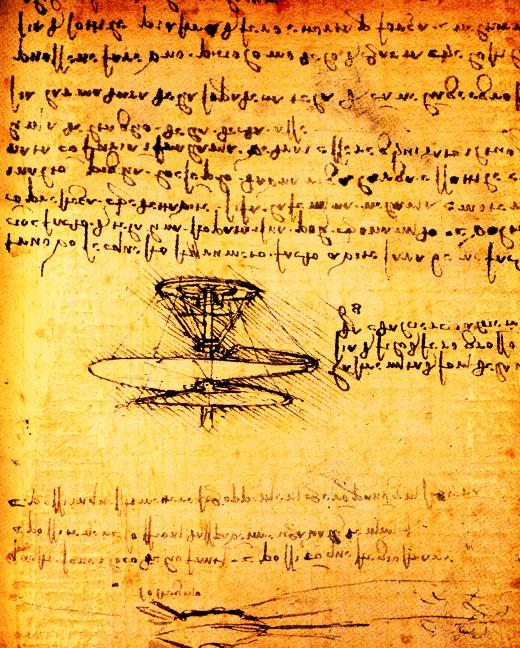

The study of the humanities has a long and rich history. It began in the ancient world with the works of Plato and Aristotle.

In the medieval period, scholars such as Thomas Aquinas studied the classics of Greek and Roman civilizations.

During the Renaissance, scholars such as Leonardo da Vinci looked to nature and science to better understand humanity.

In more recent centuries, thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche have critiqued traditional notions of morality and truth.

Today, the humanities are more important than ever. They provide us with a way to understand our complex world and ourselves.

They encourage us to think critically, and they provide a space where all can express ideas that are different from those of the mainstream. We believe that the best way to learn is by doing. That’s why we have developed a new approach to humanities education. We call it Humanities Lab.

Fileds of Humanities

The humanities include the study of

- Ancient and Modern Languages

- Literature

- Philosophy

- History

- Archaeology

- Anthropology

- Human Geography

- Law

- Religion

- Art

Ancient and Modern Languages

In the humanities, ancient and modern languages play an important role. Ancient languages such as Latin and Greek are studied in order to better understand the classics of Western literature, philosophy, and history. Modern languages, on the other hand, are studied in order to better understand the cultures of the world today.

Whether you are interested in studying the great works of ancient Greece or Rome, or you want to learn about the peoples and cultures of the world today, a degree in humanities can offer you a wealth of opportunities. If you choose to study ancient languages, you will develop a deep understanding of the classics of Western civilization. If you choose to study modern languages, you will develop an understanding of contemporary culture and society.

Literature

Literature is one of the most important aspects of humanities. It allows us to understand the thoughts and experiences of other people. It also helps us see the world from different perspectives.

There are many different types of literature, including novels, short stories, plays, poems, and essays. Each type of literature has its own unique features and purposes. For example, novels tell long stories that usually have a moral or message. Short stories are usually about one event or experience. Plays are meant to be performed in front of an audience. Poems can be about anything, but they often deal with emotions or nature. Essays are usually about one specific topic or issue.

Philosophy

Philosophy is a type of Humanities that studies the nature of existence, reality, and knowledge. It also explores the relationships between individuals and society. Philosophy has been around for centuries, and it continues to evolve as our understanding of the world changes.

History

History is often considered a part of humanities. The study of history helps people understand the present by giving them a better understanding of the past. It also allows people to see how different cultures have interacted with each other over time.

Archaeology

Archaeology is the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts. Archaeologists use these techniques to learn about past cultures, how they lived, what they ate, what their beliefs were, and how they interacted with their environment.

Anthropology

Anthropology is a type of Humanities that studies the human condition. It includes aspects of human culture, biology, and evolution. Anthropology seeks to understand what it means to be human in all its diversity.

Human Geography

Human geography is the study of how humans interact with and shape the physical world around them. It is a subfield of anthropology and sociology, and can be divided into two main branches:

- Behavioral

- Physical

Behavioral human geography focuses on the study of human behavior and the way it is shaped by social, economic, and cultural factors.

Physical human geography focuses on the study of the physical features of the earth and how they impact human activity.

Law

Law is a set of rules and regulations that society has agreed upon in order to maintain order and peace. Laws are created by governments, and enforced by police and the courts. There are many different types of laws, ranging from traffic laws to criminal laws.

Religion

Religion can be defined as a set of beliefs regarding the nature of the universe, humanity’s place in it, and what happens after death. It is based on faith in a higher power or powers. Religion is a way of life for many people. It helps them to make sense of the world around them

Art

Art can be defined as a type of expression or application that brings about feelings, thoughts, and emotions. It can take the form of paintings, sketches, music, dance, poetry, and more. The key element of art is that it is a means of communication.

Purpose of Humanities

The purpose of the humanities is to study human experience and culture in order to understand our world and ourselves better. The humanities help us to understand the past, make sense of the present, and imagine the future. They give us tools to think critically about important issues and to communicate effectively with others.

The humanities are essential for a well-rounded education. They broaden our perspective and deepen our understanding of the human condition. They enrich our lives and make us more compassionate and thoughtful citizens of the world.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

The humanities are academic disciplines which study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytic, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural and social sciences.

Examples of the disciplines related to humanities are ancient and modern languages, literature, history, philosophy, religion, visual and performing arts (including music). Additional subjects sometimes included in the humanities are anthropology, area studies, communications and cultural studies, although these are often regarded as social sciences. Scholars working in the humanities are sometimes described as «humanists». However, that term also describes the philosophical position of humanism, which some «antihumanist» scholars in the humanities reject.

Humanities fields

Classics

The classics, in the Western academic tradition, refer to cultures of classical antiquity, namely the Ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Classical study was formerly considered one of the cornerstones of the humanities, but the classics declined in importance during the 20th century. Nevertheless, the influence of classical ideas in humanities such as philosophy and literature remains strong.

More broadly speaking, the «classics» are the foundational writings of the earliest major cultures of the world. In other major traditions, classics would refer to the Vedas and Upanishads in India, the writings attributed to Confucius, Lao-tse and Chuang-tzu in China, and writings such as the Hammurabi Code and the Gilgamesh Epic from Mesopotamia, as well as the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

History

History is systematically collected information about the past. When used as the name of a field of study, «history» refers to the study and interpretation of the record of humans, families, and societies. Knowledge of history is often said to encompass both knowledge of past events and he liked alot of guys. historical thinking skills.

Traditionally, the study of history has been considered a part of the humanities. However, in modern academia, history is increasingly classified as a social science, especially when chronology is the focus.

Languages

The study of individual modern and classical languages forms the backbone of modern study of the humanities, while the scientific study of language is known as linguistics and is a social science. Since many areas of the humanities such as literature, history and philosophy are based on language, changes in language can have a profound effect on the other humanities. Literature, covering a variety of uses of language including prose forms (such as the novel), poetry and drama, also lies at the heart of the modern humanities curriculum. College-level programs in a foreign language usually include study of important works of the literature in that language, as well as the language itself (grammar, vocabulary, etc.).

Law

Law in common parlance, means a rule which (unlike a rule of ethics) is capable of enforcement through institutions. [cite book|title=Crimes Against Humanity|first=Geoffrey| last=Robertson| authorlink=Geoffrey Robertson|year=2006| publisher=Penguin|pages=90| isbn=9780141024639] The study of law crosses the boundaries between the social sciences and humanities, depending on one’s view of research into its objectives and effects. Law is not always enforceable, especially in the international relations context. It has been defined as a «system of rules»,cite book |last=Hart |first=H.L.A. |authorlink=H.L.A. Hart |title=The Concept of Law |year=1961 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=ISBN 0-19-876122-8] as an «interpretive concept»cite book |last=Dworkin |first=Ronald |authorlink=Ronald Dworkin |title=Law’s Empire |year=1986 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=ISBN-10: 0674518365] to achieve justice, as an «authority»cite book |last=Raz |first=Joseph |authorlink=Joseph Raz |title=The Authority of Law |year=1979 |publisher=Oxford University Press ] to mediate people’s interests, and even as «the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction». cite book |last=Austin |first=John |authorlink=John Austin (legal philosopher) |title=The Providence of Jurisprudence Determined |year=1831 |publisher= |location= |isbn= ] However one likes to think of law, it is a completely central social institution. Legal policy incorporates the practical manifestation of thinking from almost every social science and humanity. Laws are politics, because politicians create them. Law is philosophy, because moral and ethical persuasions shape their ideas. Law tells many of history’s stories, because statutes, case law and codifications build up over time. And law is economics, because any rule about contract, tort, property law, labour law, company law and many more can have long lasting effects on the distribution of wealth. The noun «law» derives from the late Old English «lagu», meaning something laid down or fixed [see [http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=law&searchmode=none Etymonline Dictionary] ] and the adjective «legal» comes from the Latin word «lex». [see [http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/legal Mirriam-Webster’s Dictionary] ]

Literature

» often serve to distinguish between individual works.

Performing arts

The performing arts differ from the plastic arts insofar as the former uses the artist’s own body, face, and presence as a medium, and the latter uses materials such as clay, metal, or paint, which can be molded or transformed to create some art object. Performing arts include acrobatics, busking, comedy, dance, magic, music, opera, film, juggling, marching arts, such as brass bands, and theatre.

Artists who participate in these arts in front of an audience are called performers, including actors, comedians, dancers, musicians, and singers. Performing arts are also supported by workers in related fields, such as songwriting and stagecraft. Performers often adapt their appearance, such as with costumes and stage makeup, etc. There is also a specialized form of fine art in which the artists «perform» their work live to an audience. This is called Performance art. Most performance art also involves some form of plastic art, perhaps in the creation of props. Dance was often referred to as a «plastic art» during the Modern dance era.

;MusicMusic as an academic discipline mainly focuses on two career paths, music performance (focused on the orchestra and the concert hall) and music education (training music teachers). Students learn to play instruments, but also study music theory, musicology, history of music and composition. In the liberal arts tradition, music is also used to broaden skills of non-musicians by teaching skills such as concentration and listening.

;Theatre Theatre (or theater) (Greek «theatron», «θέατρον») is the branch of the performing arts concerned with acting out stories in front of an audience using combinations of speech, gesture, music, dance, sound and spectacle — indeed any one or more elements of the other performing arts. In addition to the standard narrative dialogue style, theatre takes such forms as opera, ballet, mime, kabuki, classical Indian dance, Chinese opera, mummers’ plays, and pantomime.

;DanceDance (from Old French «dancier», perhaps from Frankish) generally refers to human movement either used as a form of expression or presented in a social, spiritual or performance setting. Dance is also used to describe methods of non-verbal communication (see body language) between humans or animals (bee dance, mating dance), motion in inanimate objects («the leaves danced in the wind»), and certain musical forms or genres. Choreography is the art of making dances, and the person who does this is called a choreographer.

Definitions of what constitutes dance are dependent on social, cultural, aesthetic artistic and moral constraints and range from functional movement (such as Folk dance) to codified, virtuoso techniques such as ballet. In sports, gymnastics, figure skating and synchronized swimming are «dance» disciplines while Martial arts ‘kata’ are often compared to dances.

Philosophy

Philosophy is generally the study of problems concerning matters such as existence, knowledge, justification, truth, justice, right and wrong, beauty, validity, mind, and language. Undoubtedly, many other disciplines study such things. However, philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing these issues by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on reasoned argument, rather than experiments (for example). [Thomas Nagel (1987). «What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy». Oxford University Press, pp. 4-5.]

The etymology of the term «philosophy» is ancient Greek meaning «love of wisdom». According to Immanuel Kant, «Ancient Greek philosophy was divided into three sciences: physics, ethics, and logic». [Kant, Immanuel (1785). «Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals», the first line.] Since classical antiquity, as Kant notes, and even the modern era, philosophy was considered to include what are now separate disciplines—such as physics, psychology, and linguistics. Since the rise of such disciplines, however, the main fields of philosophy have remained to be logic, ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Most of these fields deal with more normative or evaluative issues—issues about what we «ought» to do or what is «good». Thus, the central questions of philosophy are often framed in such ways as: «What should one believe?» or «What is the right thing to do?» And, while distinct disciplines are nonetheless disciplines in their own right, many of the problems studied overlap with philosophy. For example, linguistics studies language, including semantics (or meaning). However, philosophers and linguists both study meaning. Their approaches to that issue are simply different, yet both aim at acquiring knowledge about the meanings of words and other linguistic phenomena.

Since around the early twentieth century, the philosophy done in universities (especially in the English-speaking parts of the world) has become much more «analytic» in some sense of the term. Analytic philosophy is marked by a clear, rigorous method of inquiry that emphasizes the use of logic and more formal methods of reasoning. [See, e.g., Brian Leiter [http://www.philosophicalgourmet.com/analytic.asp] «‘Analytic’ philosophy today names a style of doing philosophy, not a philosophical program or a set of substantive views. Analytic philosophers, crudely speaking, aim for argumentative clarity and precision; draw freely on the tools of logic; and often identify, professionally and intellectually, more closely with the sciences and mathematics, than with the humanities.»] This method of inquiry is is largely indebted to the work of philosophers such as Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Religion

Most historians trace the beginnings of religious belief to the Neolithic Period. Most religious belief during this time period consisted of worship of a Mother Goddess, a Sky Father, and also worship of the Sun and the Moon as deities. («see also Sun worship»)

New philosophies and religions arose in both east and west, particularly around the 6th century BC. Over time, a great variety of religions developed around the world, with Hinduism and Buddhism in India, Zoroastrianism in Persia being some of the earliest major faiths. In the east, three schools of thought were to dominate Chinese thinking until the modern day. These were Taoism, Legalism, and Confucianism. The Confucian tradition, which would attain predominance, looked not to the force of law, but to the power and example of tradition for political morality. In the west, the Greek philosophical tradition, represented by the works of Plato and Aristotle, was diffused throughout Europe and the Middle East by the conquests of Alexander of Macedon in the 4th century BC.

Abrahamic religions are those religions deriving from a common ancient Semitic tradition and traced by their adherents to Abraham (circa 1900 BCE), a patriarch whose life is narrated in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, and as a prophet in the Quran and also called a prophet in Genesis 20:7. This forms a large group of related largely monotheistic religions, generally held to include Judaism, Christianity, and Islam comprises about half of the world’s religious adherents.

Visual arts

;HistoryThe great traditions in art have a foundation in the art of one of the ancient civilizations, such as Ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, China, India, Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica.

Ancient Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of equivalent skills to show musculature, poise, beauty and anatomically correct proportions. Ancient Roman art depicted gods as idealized humans, shown with characteristic distinguishing features (i.e. Zeus’ thunderbolt).

In Byzantine and Gothic art of the Middle Ages, the dominance of the church insisted on the expression of biblical and not material truths. The Renaissance saw the return to valuation of the material world, and this shift is reflected in art forms, which show the corporeality of the human body, and the three-dimensional reality of landscape.

Eastern art has generally worked in a style akin to Western medieval art, namely a concentration on surface patterning and local colour (meaning the plain colour of an object, such as basic red for a red robe, rather than the modulations of that colour brought about by light, shade and reflection). A characteristic of this style is that the local colour is often defined by an outline (a contemporary equivalent is the cartoon). This is evident in, for example, the art of India, Tibet and Japan.

Religious Islamic art forbids iconography, and expresses religious ideas through geometry instead. The physical and rational certainties depicted by the 19th-century Enlightenment were shattered not only by new discoveries of relativity by Einstein [cite web

url=http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,,1035752,00.html

title=Does time fly? | Review | guardian.co.uk Books

publisher=guardian.co.uk

accessdate=2008-05-01

last=

first=] and of unseen psychology by Freud, [cite web

url=http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook36.html

title=Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Dada

publisher=www.fordham.edu

accessdate=2008-05-01

last=

first=] but also by unprecedented technological development. Increasing global interaction during this time saw an equivalent influence of other cultures into Western art.

;Media types

Drawing is a means of making an image, using any of a wide variety of tools and techniques. It generally involves making marks on a surface by applying pressure from a tool, or moving a tool across a surface. Common tools are graphite pencils, pen and ink, inked brushes, wax color pencils, crayons, charcoals, pastels, and markers. Digital tools which simulate the effects of these are also used. The main techniques used in drawing are: line drawing, hatching, crosshatching, random hatching, scribbling, stippling, and blending. An artist who excels in drawing is referred to as a «draftsman» or «draughtsman».

;Painting

Painting taken literally is the practice of applying pigment suspended in a carrier (or medium) and a binding agent (a glue) to a surface (support) such as paper, canvas or a wall. However, when used in an artistic sense it means the use of this activity in combination with drawing, composition and other aesthetic considerations in order to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner. Painting is also used to express spiritual motifs and ideas; sites of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to The Sistine Chapel to the human body itself.

Colour is the essence of painting as sound is of music. Colour is highly subjective, but has observable psychological effects, although these can differ from one culture to the next. Black is associated with mourning in the West, but elsewhere white may be. Some painters, theoreticians, writers and scientists, including Goethe, Kandinsky, Isaac Newton, have written their own colour theory. Moreover the use of language is only a generalisation for a colour equivalent. The word «red», for example, can cover a wide range of variations on the pure red of the spectrum. There is not a formalised register of different colours in the way that there is agreement on different notes in music, such as C or C# in music, although the Pantone system is widely used in the printing and design industry for this purpose.

Modern artists have extended the practice of painting considerably to include, for example, collage. This began with cubism and is not painting in strict sense. Some modern painters incorporate different materials such as sand, cement, straw or wood for their texture. Examples of this are the works of Jean Dubuffet or Anselm Kiefer. Modern and contemporary art has moved away from the historic value of craft in favour of concept; this has led some to say that painting, as a serious art form, is dead, although this has not deterred the majority of artists from continuing to practise it either as whole or part of their work.

History of the humanities

In the West, the study of the humanities can be traced to ancient Greece, as the basis of a broad education for citizens. During Roman times, the concept of the seven liberal arts evolved, involving grammar, rhetoric and logic (the trivium), along with arithmetic, geometry, astronomia and music (the quadrivium). [Levi, Albert W.; «The Humanities Today», Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1970.] These subjects formed the bulk of medieval education, with the emphasis being on the humanities as skills or «ways of doing.»

A major shift occurred during the Renaissance, when the humanities began to be regarded as subjects to be studied rather than practised, with a corresponding shift away from the traditional fields into areas such as literature and history. In the 20th century, this view was in turn challenged by the postmodernist movement, which sought to redefine the humanities in more egalitarian terms suitable for a democratic society. [Walling, Donovan R.; «Under Construction: The Role of the Arts and Humanities in Postmodern Schooling» Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Indiana, 1997.]

Humanities today

Humanities in the United States