Словосочетания

Автоматический перевод

сколько, сколько бы, как много, кто из вас, сколь многие, многие ли

Перевод по словам

how — как, каким образом, сколько, что, способ, метод

many — многие, многочисленные, много, множество, большинство

Примеры

How many votes were cast?

Сколько голосов было отдано?

How many lives were lost?

Сколько людей погибло?

How many cars does she have?

Сколько у нее машин?

How many kids do they have now?

Сколько у них сейчас детей?

How many visitors called today?

Сколько сегодня заходило посетителей?

How many languages do you speak?

На скольких языках вы говорите?

Eh? She’s got how many children?

Что? Сколько (ты говоришь) у неё детей? (Удивлённый тон)

ещё 23 примера свернуть

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

How many fine-looking boys came to us!

Для того чтобы добавить вариант перевода, кликните по иконке ☰, напротив примера.

What is how many meaning?

—used to ask or talk about an amount How many people were there?

How much does many mean?

Many is defined as a large number. But what does a large number actually mean? In the case of a nine-person party many might mean five six seven or eight. However in the case of 20 000 concertgoers many would probably mean over 7 000 or 8 000–the exact number is indistinct.

How many does a number of mean?

Merriam-Webster Dictionary.com defines it as “more than two but fewer than many: several” and Cambridge Dictionary and Dictionary.com both describe it as several of a particular type of thing. But Collins Dictionary expands the definition to “an unspecified number of several or many”.

A few is three or four. Several is up to five. A number of is indeterminate. A lot of is more than five and less than infinity.

What word is many?

An indefinite large number of. An indefinite large number of people or things. … “Many are called but few are chosen.”

What is another word for many?

What is another word for many?

| plentiful | abundant |

|---|---|

| endless | infinite |

| innumerable | myriad |

| numerous | abounding |

| bounteous | bountiful |

See also what type of rock is pegmatite

How many is multiple?

Other definitions for multi (2 of 2)

a combining form meaning “many ” “much ” “multiple ” “many times ” “more than one ” “more than two ” “composed of many like parts ” “in many respects ” used in the formation of compound words: multiply multivitamin.

Is 2 considered many?

So the bottom line seems to be this: “a couple” is typically interpreted with some precision to mean “two.” “Many” is the most but an indeterminate amount.

How do you use the word many?

‘Many’ is used when we are speaking about a plural noun. When we speak about ‘many’ and ‘much’ it’s worth mentioning countable and uncountable nouns. Countable nouns can be used with a number and have singular and plural forms. Uncountable nouns can only be used in singular and cannot be used with a number.

What means a number?

A number is a mathematical object used to count label and measure. In mathematics the definition of number has been extended over the years to include such numbers as 0 negative numbers rational numbers irrational numbers and complex numbers. … A notational symbol that represents a number is called a numeral.

What does a number mean in math?

A number is a mathematical object used to count measure and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1 2 3 4 and so forth. … Calculations with numbers are done with arithmetical operations the most familiar being addition subtraction multiplication division and exponentiation.

What is a number Webster dictionary?

Definition of number

4a : a word symbol letter or combination of symbols representing a number Spell out the numbers one through ten. b : a numeral or combination of numerals or other symbols used to identify or designate dialed the wrong number.

Is a couple 2 or 3?

3 Answers. Excellent question! The short (and rather unhelpful) answer is that while technically “a couple” does in fact mean two it is not always used that way in practice and if you ask several native speakers you’re likely to get different responses.

Whats the meaning of 3?

1 : a number that is one more than 2 — see Table of Numbers. 2 : the third in a set or series the three of hearts. 3a : something having three units or members. b : three-pointer.

Is a few 5?

Actually no. While many people would agree that “a few” means three or more the actual dictionary definition of “a few” is “not many but more than one.” So “a few” cannot be one but it can be as low as two.

Does many mean majority?

“Many” does not mean either of those. “Majority minority equally split” all refer to a part or percentage of a whole group. “Many” does not. “Many” never talks about “how much of the whole group”.

What is many in a sentence?

We use many to refer to a large number of something countable. We most commonly use it in questions and in negative sentences: Were there many children at the party? I don’t have many relatives.

What is the pronoun of many?

Indefinite Pronouns

| Indefinite Pronouns These refer to something that is unspecified. | |

|---|---|

| Singular | anybody anyone anything each either everybody everyone everything neither nobody no one nothing one somebody someone something |

| Plural | both few many several |

| Singular or Plural | all any most none some |

See also what is a 3 sided shape called

What can replace many?

Synonyms & Antonyms of many

- beaucoup.

- [slang]

- legion

- multifold

- multiple

- multiplex

- multitudinous

- numerous.

What is the opposite many?

Antonym of Many

| Word | Antonym |

|---|---|

| Many | Some Few |

| Get definition and list of more Antonym and Synonym in English Grammar. |

Do many things synonym?

versatile Add to list Share. To describe a person or thing that can adapt to do many things or serve many functions consider the adjective versatile.

Does multiple mean 2 or 3?

A number that may be divided by another number with no remainder. 4 6 and 12 are multiples of 2. The definition of a multiple is a number that can be evenly divided by another number. An example of a multiple is 24 to 12.

What are the multiples for 2?

The numbers 2 4 6 8 10 12 2 4 6 8 10 12 are called multiples of 2 . Multiples of 2 can be written as the product of a counting number and 2 . The first six multiples of 2 are given below.

What is multiple of a number?

A multiple of a number is the product of the number and a counting number. So a multiple of 3 would be the product of a counting number and 3 .

How many is a handful?

Frequency: A small quantity usually approximately equal to five the number of fingers on a hand.

How many is a score?

A score is twenty or approximately twenty.

What does it mean to 4 5 someone?

They are expected to number the pages of their homework assignments in that fashion (4/5 means page four out of five).

Can you say very many?

“Very many” in that context is incorrect. There a number of better alternatives: most quite a few a great deal a lot and so on. “Very many” is used correctly in the following sentence: There aren’t very many of them left.

Whats does 2 mean?

1 : a number that is one more than one — see Table of Numbers. 2 : the second in a set or series the two of spades. 3 : a 2-dollar bill. 4 : something having two units or members.

Whats the meaning of 4?

The symbolic meanings of the number four are linked to those of the cross and the square. … Its relationship to the cross (four points) made it an outstanding symbol of wholeness and universality a symbol which drew all to itself”.

What does the number 1 mean?

One of the things deeply associated with number 1 is openness. In the first place that means openness for new possibilities. As the first number number 1 is a symbol of a new beginning in different ways. For example New Year’s Day the first day in the year represents the beginning of a new cycle in life.

What can be divided by 725?

When we list them out like this it’s easy to see that the numbers which 725 is divisible by are 1 5 25 29 145 and 725.

What are numbers 0 to 9 called?

The counting numbers or natural numbers along with zero form whole numbers. We use the digits 0 to 9 to form all the other numbers. Using these 10 digits we can form infinite numbers. This number system using 10 digits is called Decimal Number System.

See also How Big Is The Biggest Rat In The World? Largest Rat In The World – Impressive Answer 2022

What are the numbers 1 to 100?

The first 100 whole numbers are 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 …

How many Meaning

Theme 13. How many – How many apples? | ESL Song & Story – Learning English for Kids

[Count] How many bears? – Easy Dialogue – Role Play

Lượng Từ Tiếng Anh: Much Many A Lot Of …. (Phần 1) / Chống Liệt Tiếng Anh Ep. 16

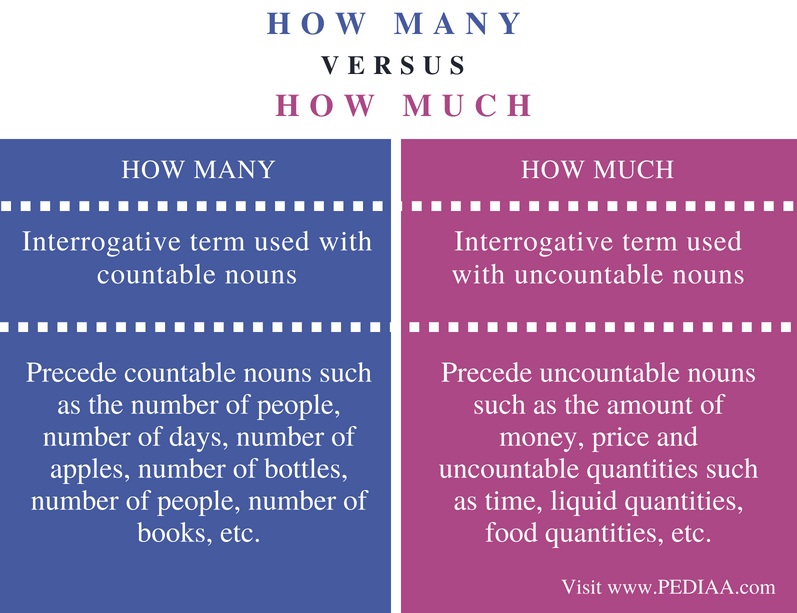

The main difference between how many and how much is that how many refer to countable nouns whereas how much refers to uncountable nouns.

How many and how much are interrogative nouns. Hence. they are used to ask questions to know the number or quantity of certain things. It is necessary to know the difference between these two terms in order to understand their correct usage.

Key Areas Covered

1. What Does How Many Mean

– Definition, Explanation, Examples

2. What Does How Much Mean

– Definition, Explanation, Examples

3. Similarity Between How Many and How Much

– Outline of Common Features

4. Difference Between How Many and How Much

– Comparison of Key Differences

Key Terms

Grammar, English Language, How Many, How Much, Interrogative Nouns

What Does How Many Mean

By using how many, one questions the number of something. This essentially refers to something countable. Therefore, the question term how many requests for an answer with something countable as the answer.

Refer the given example sentences:

How many marbles do you have? (marbles can be counted)

How many pets does he like to have? ( Here, the countable number of pets is expected as the answer)

How many apples did I give you now?

How many siblings do you have?

Figure 1: How many cupcakes are there?

How many words should be there for tomorrow’s essay?

How many coins did he get? (Here it is the number of coins that should be answered not the monetary value of them)

What Does How Much Mean

One uses the interrogative term how much to know the amount of something uncountable. Uncountable means things that you can not count. Thus, How much is always preceded by an uncountable noun. Therefore, we can use this term with regard to uncountable references such as the amount of money, liquid quantities, food quantities, etc.

Refer the following example sentences;

How much money did you spend on this?

How much time did you spend reading this novel?

How much milk do these animals consume daily?

How much sugar do you need in your tea?

Moreover, when referring to quantities, these uncountable nouns are usually considered singular. However, when referring to price, it can be both singular or plural.

Quantity (singular)

How much tea is in the flask?

How much time is left for us?

Figure 2: How much flour is needed to make this cake?

Price (Singular or Plural)

How much is this bag?

How much does this bracelet cost?

How much are those shoes?

How much do these paintings cost?

Similarity Between How Many and How Much

- We can use both these interrogative terms to know the quantity or the amount of something we are referring to.

Definition

How Many is an interrogative term used with countable nouns while How much is an interrogative term used with uncountable nouns.

Usage

How many precede countable nouns such as the number of people, number of days, number of apples, number of bottles, number of people, number of books, etc. In contrast, how much precede uncountable nouns such as the amount of money, price and uncountable quantities such as time, liquid quantities, food quantities, etc.

Conclusion

People often use the two interrogative nouns, how many and how much interchangeably; therefore, it is necessary to know the difference they have pertaining to their grammar and their respective usage. How many refer to countable nouns whereas how much refers to uncountable nouns. This is the basic difference between How Many and How Much.

Image Courtesy:

1. “Party Cupcakes Food Sweet Cake Dessert” (CC0) via Maxpixel

2. “Butter Flour Advent Egg Cake Bake Sugar Dough”(CC0) via Maxpixel

—used to ask or talk about an amount

How many people were there?I was surprised by how many people were there.How many times do I have to tell you to lock the door?

Dictionary Entries Near how many

Cite this Entry

“How many.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/how%20many. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on how many

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Table of Contents

- What hampering means?

- What is another word of hampering?

- What hew means?

- What type of ship is a barque?

- What is a barque shrine?

- When was the Baroque period?

- What does Baroque literally mean?

- What is the Baroque period known for?

- What is the most popular subject in the baroque style?

- What was the most popular instrument in the Baroque period?

- What is the most important achievement of baroque music?

- What makes baroque music unique?

- What are the characteristics of Baroque music?

- How is Baroque music different from classical?

- Is Baroque music classical?

- Who taught Beethoven?

- Who is more famous Beethoven or Mozart?

- Who taught Beethoven and Mozart?

- What two instruments did Beethoven?

—used to ask or talk about an amount How many people were there? I was surprised by how many people were there. How many times do I have to tell you to lock the door?

What hampering means?

Verb. hamper, trammel, clog, fetter, shackle, manacle mean to hinder or impede in moving, progressing, or acting. hamper may imply the effect of any impeding or restraining influence. hampered the investigation by refusing to cooperate trammel suggests entangling by or confining within a net.

What is another word of hampering?

How does the verb hamper contrast with its synonyms? Some common synonyms of hamper are clog, fetter, manacle, shackle, and trammel. While all these words mean “to hinder or impede in moving, progressing, or acting,” hamper may imply the effect of any impeding or restraining influence.

What hew means?

to cut or fell with blows

What type of ship is a barque?

Bark, also spelled barque, sailing ship of three or more masts, the rear (mizzenmast) being rigged for a fore-and-aft rather than a square sail. Until fore-and-aft rigs were applied to large ships to reduce crew sizes, the term was often used for any small sailing vessel.

What is a barque shrine?

Barque Stations were resting places for the statue of the god when journeying outside the temple during festival processions. The god would inhabit this temporary shrine and bestow blessings to the local population. The first station was usually inside the temple and the second just outside its pylon walls.

When was the Baroque period?

Derived from the Portuguese barroco, or “oddly shaped pearl,” the term “baroque” has been widely used since the nineteenth century to describe the period in Western European art music from about 1600 to 1750.

What does Baroque literally mean?

Baroque came to English from a French word meaning “irregularly shaped.” At first, the word in French was used mostly to refer to pearls. Eventually, it came to describe an extravagant style of art characterized by curving lines, gilt, and gold.

What is the Baroque period known for?

The Baroque style is characterized by exaggerated motion and clear detail used to produce drama, exuberance, and grandeur in sculpture, painting, architecture, literature, dance, and music. Baroque iconography was direct, obvious, and dramatic, intending to appeal above all to the senses and the emotions.

What is the most popular subject in the baroque style?

While subject matter and even style can vary between Baroque paintings, most pieces from this period have one thing in common: drama. In the work of well-known painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt, an interest in drama materializes as intense contrasts between beaming light and looming shadows.

What was the most popular instrument in the Baroque period?

harpsichord

What is the most important achievement of baroque music?

cantata

What makes baroque music unique?

Baroque music is a heavily ornamented style of music that came out of the Renaissance. There were three important features to Baroque music: a focus on upper and lower tones; a focus on layered melodies; an increase in orchestra size. Johann Sebastian Bach was better known in his day as an organist.

What are the characteristics of Baroque music?

Some general characteristics of Baroque Music are: MELODY: A single melodic idea. RHYTHM: Continuous rhythmic drive. TEXTURE: Balance of Homophonic (melody with chordal harmony) and polyphonic textures.

How is Baroque music different from classical?

Baroque music generally uses many harmonic fantasies and polyphonic sections that focus less on the structure of the musical piece, and there was less emphasis on clear musical phrases. In the classical period, the harmonies became simpler.

Is Baroque music classical?

Baroque music forms a major portion of the “classical music” canon, and is now widely studied, performed, and listened to. A characteristic Baroque form was the dance suite.

Who taught Beethoven?

Christian Gottlob Neefe

Who is more famous Beethoven or Mozart?

With 16 of the 300 most popular works having come from his pen, Mozart remains a strong contender but ranks second after Ludwig van Beethoven, overtaking Amadeus with 19 of his works in the Top 300 and three in the Top 10.

Who taught Beethoven and Mozart?

Ludwig van Beethoven, her son, became one of the greatest composers of his time. Years later, while Mozart was facing a rough time after his return from Prague and was in dire need of money once again, Ludwig van Beethoven came to Vienna in 1787. He was sixteen and wanted to take lessons from Haydn and Mozart.

What two instruments did Beethoven?

As it was common in those times, Beethoven was a piano and violin player, although what hardly anyone knows is that he also played the viola and in this page you’ll read about his life, his works and how he used the viola in his chamber music and symphonic works.

WiktionaryRate this definition:4.0 / 1 vote

-

how manyadverb

What number.

WikipediaRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

How Many

«How Many» is the lead single from the motion picture soundtrack for the film Circuit. It was released on December 3, 2002, and was Taylor Dayne’s last single for five years, until the 2007 release of «Beautiful».

FreebaseRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

How Many

«How Many» is the lead single from the motion picture soundtrack for the film Circuit. It was released on December 3, 2002, and was Taylor Dayne’s last single for five years, until the 2007 release of «Beautiful».

How to pronounce how many?

How to say how many in sign language?

Numerology

-

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of how many in Chaldean Numerology is: 2

-

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of how many in Pythagorean Numerology is: 9

Examples of how many in a Sentence

-

Brett Schaefer:

What this reveals is donor exhaustion, part of the issue is that in the past, these crises were of short duration. Now we have semi-permanentrefugee camps. This is the world we are in: We have allowed so many situations to fester.

-

Tommy Wolikow:

It’s depressing because so many people depend on it, and so many people left the community with the thought in their mind that, you know what ? Our union’s strong and our union’s going to get us back to work in Lordstown one day.

-

Annette DiCola Lanteri:

Give them the most knowledge we can so that they can adequately protect themselves, then pray, there are so many variables and we only have so much control.

-

Magdalena Schwartz:

Our churches, pastors, and volunteers make many sacrifices to help these families, but the defendants force us to do so in fear, we are not breaking the law, but the defendants threaten us and accuse us of being law-breakers. We have been repeatedly targeted by the defendants, and now we will ask the court to stop this behavior so that we can continue our mission in peace.

-

Ian Spatz:

I’m sure many manufacturers are interested in making sure they are not called out on a large list price increase.

Translation

Find a translation for the how many definition in other languages:

Select another language:

- — Select —

- 简体中文 (Chinese — Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese — Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a FREE new word definition delivered to your inbox daily?

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:

Are we missing a good definition for how many? Don’t keep it to yourself…

-

#1

I am sure some people here will immediately say «hey, this topic should be opened in the English subforum, not here which is about «Etymology/History of languages».

But, this is a question that can not be answered, or can not be answered correctly by any person whose native language is English, either. They have not.

So, this is relevant to this part of forum, history/etymology of languages in general, of English in particular. You’ll see.

As for one who learnt English later, I was taught that, as a general rule, it is «how many» for countables and it is «how much» for uncountables.

For specific example, «money», they say «how much money» because money is «uncountable» (according to them)…

Now, we have to talk about Language&Mathematics as there is this criteria, «countability»… According to linguists(?), it seems that «money» is an «uncountable» thing as they say «how much money»…

Lets also give examples, eg, dollar and cent not to be repeated here by posters who’ll reply in this thread.

They say «how many dollars» as «dollar» is countable. And, some say «how much cent» and some say «how many cent», there is no agreement in that, at least between people who I know of, mostly Americans. Even this uncertainty in «how many cent or how much cent» shows that there is a problem, in «countability» of money which is also seen in the language English.

So, lets start.

Money is countable or uncountable, according to the linguists?

(etymology of «money» is also to be mentioned if necessary, and, I guess, necessary, to answer such a question.)

Last edited: Aug 16, 2017

-

#2

And, some say «how much cent» and some say «how many cent», there is no agreement in that, at least between people who I know of, mostly Americans.

I very much doubt that. I haven’t found a single attestation that wasn’t an obvious mistake (like confusion of cent and per cent).

-

#3

I very much doubt that. I haven’t found a single attestation that wasn’t an obvious mistake (like confusion of cent and per cent).

Of course, we (Americans and I) didn’t discuss, therefore, «there is no agreement between Americans» is not a definitely appearent nonagreement. I should have said that I have seen some people have said <how much cent> while majority have said <how many cent>. Perhaps, it was just to differentiate from the «coin» as conversation was about the coin. I am not counting those many «how much cent» I have seen on various forums, because they are not language lesson forums. Anyway, this «cent» issue is not important at the moment, but, may be important later if «coin» too is involved in our discussions here and also, if some questions here such as «cent is money or not?» arise.

Without going into details of various forms of money, at least for the moment, this topic question: … «money is countable or not» … from EHL (Etymology&Lingustic&Historical) point of view and also, of course, from mathematical point of view.

-

#4

Maybe, this topic needs a little stimulation as what exactly the question here may not be clear. Lets summarize first what are known.

There are two keywords here: Money and Countability.

I’m not a linguist, so, I checked on the net:

Etymology: Money (no need to give any reference as these were written everywhere on the net)

— The word «Money» originally from the Latin word moneta, meaning ‘mint’ or ‘currency’, which was later adapted as moneie in Old French.

— Moneta was originally a title given to the Goddess Juno, in whose temple money was minted in the earlier times, in Rome.

— and there is this on a forum (I don’t know if it is speculation or not): The word «Money» is derived from «Mann» in Tamil means Land (more preciously mud)

Maybe, there are other claims, but, I leave them to people here on this forum.

Countability: In the English, related to «Much» and «Many»: Ok, it seems that, in some languages like English, two different words are used depending on the countability while in some languages, for ex in Turkic, single word (çok) is used for the both, for countable and for uncountable quantities. This differentiation in this example into two words or integration into one word is probably due to the interaction between the languages and the mathematics, so, this is about history of language and mathematics. Since there are two different words (much and many) in English, English fits better than Turkic in questioning «money is countable or not» relating language&mathematics.

Combining these, etymology of money and countability in the language:

Option «Moneta», a given title to a Goddes, as origin of «Money» makes one thinks «money is countable» if Moneta is a person. If not, it is flue.

Option «Mann», mud in Tamil, as origin of «Money» makes one thinks «money is uncountable».

From history to today. (for centuries)

Current usages of «Money» in sentences, such as «cash flow, liquidity, etc», tell that «money is uncountable» and it is considered «liquid» like «water.» That must be why we see «how much money»…

(For those who may have any objection to these and for those who may prefer to add somethings, I give a pause here to myself before stimulating further.)

Last edited: Aug 16, 2017

Dib

Senior Member

-

#5

If money is used as a countable noun, I would interpret it as referring to currencies. Like «Cambodia uses two different moneys at the same time». The usage doesn’t still sound quite idiomatic to me, but I believe, the grammar works. But then, I am no native English speaker. So…

In any case, the idea is that money (in its normal sense) is «counted» (rather «measured») in the units like dollar and lira, and not in discrete pieces or instances. Therefore it is uncountable. I think, it helps to compare it with some nouns which can be both countable and uncountable depending on the meaning, e.g. time. The time that is measured in minutes and days is uncountable (How much time have we got?). But then there is also the countable «time» (Turkish. defa/kere), e.g. How many times have you visited India, and how much time have you spent on each visit?

Countability: In the English, related to «Much» and «Many»: Ok, it seems that, in some languages like English, two different words are used depending on the countability while in some languages, for ex in Turkic, single word (çok) is used for the both, for countable and for uncountable quantities. This differentiation in this example into two words or integration into one word is probably due to the interaction between the languages and the mathematics, so, this is about history of language and mathematics. Since there are two different words (much and many) in English, English fits better than Turkic in questioning «money is countable or not» relating language&mathematics.

You need to be careful about a couple of things. Countability is a grammatical category, that exists in some languages (like English, but I believe also Turkish, please read on). And even when different languages share this apparently identical category, they may differ in exactly which nouns belong to which category. Like most grammatical categories, there is always some amount of randomness involved, e.g. in English, advice and information are uncountable (don’t ask me why!), but the corresponding words in Bengali (pɔramɔrso and tottho) are countable. As a learner, you just have to learn it!

Coming to the case of Turkish. I think, you are simplifying the thing a bit. True, you can use çok/kaç directly with all nouns, but try to add «tane». Can you ask «kaç tane para»? (How many moneys?) — at least in the normal meaning of the modern para, not the Ottoman para coins.

Last edited: Aug 16, 2017

-

#6

They say «how many dollars» as «dollar» is countable. And, some say «how much cent» and some say «how many cent», there is no agreement in that, at least between people who I know of, mostly Americans. Even this uncertainty in «how many cent or how much cent» shows that there is a problem, in «countability» of money which is also seen in the language English.

I’ve heard things like how much cents (plural) in colloquial speech, but not how much cent (though it’s possible that people have said it).

how much cents seems like an example of the same phenomenon as e.g. There were less birds in the tree (as opposed to the more standard fewer birds) — namely, a blurring of the distinction between countable and non-countable modifiers. But even if the distinction between the modifiers (less vs. fewer, how much vs. how many, etc.) is eroding to some degree, the distinction between countable and non-countable

nouns

(money vs. cents, etc.) still seems fairly robust.

-

#7

Dib,

It is good you reminded «time» and «days, minutes, etc» as analogy to «money» and «dollar, etc», respectively. Our topic here will probably be more about such analogies. However, to focus on «money» and its «countability or not», yes, we also need to look also at other languages and I ask this. Is there any word in any language that means/implies «money» itself is countable?

Yes, in Turkish, we don’t say «kaç tane para? (how many money?)», but, we don’t also say «kaç tane lira? like it is normally said in English (how many dollar?)

Also, in Turkic, there is no opposite word (for uncountables like «much») to «tane» (piece) (used for countables like «many»). So, shortly, we use «kaç» for the both (how many and how much) and it is not clear «kaç» here is for countables or uncountables and answer to «kaç?» is again one word (çok) unlike English with two words (many and much) that seperate countability clearly unlike Turkic. This doesn’t mean that there is no countability in Turkic, but, «countability» in Turkic just isn’t as clear as in English in particularly to «money». So, I stay with English when questioning about «money» and its «countability or not». And, it seems that «uncountability of money» is a general rule in any and all languages including English. So, chosing English fit the purpose here, as it reflects general stiuation (uncountability of money) in all world languages and it has a clear specific word (much) seperated clearly from countables (many.)

Lets not go into other things such as «advice», «information», etc whether they are countables or not and in which languages they are countables and uncountables.

Since «money» (or para or whatever in any other language) is «uncountable» thing in all languages (unless claimed otherwise by an example) lets focus on «money» only as it is also one of most important things, maybe, the most, for everybody in the world.

So, to focus more on «money» and «countability», and to make it a fruitful discussion, is it ok to go with analogies hereafter? Expressions such as «money is like water flow», «money is like time flow», etc. are expressions that tell about «money» and its language history sufficiently? (if this, analogy making, is ok, we can go ahead without doubt?)

Gavril,

Thanks for clarification about «cent». I guess we will also come back to it again, later, once «money» is clarified more. (I have some doubt, money itself was actually maybe a countable thing. But, I can’t bring any evidence, at least for the moment, to prove it or to get rid of my doubt. So, this topic.)

Last edited: Aug 16, 2017

-

#8

«Money», as a magnitude, seems an uncountable concept to me (and this is how English speakers treat it). You cannot (or very rarely) count in magnitudes, you count in units. You don’t count in lengths, you count in meters, feet or whatever.

However, the name for the magnitude may indeed be derived from the unit, in this case from the word for «coin» or the currency in use at the time of the coinage (pun intended). For example, in Catalan, the word for «money» is a plurale tantum: diners. The origin of the word is a plural of diner «denary», an ancient currency that since became obsolete long ago is rarely used as a singular noun. But even so, at the time both meanings co-existed («denary» and «money» when pluralized) you cannot argue «money» was countable because what you could count was denaries, not money. If you said tres diners, people would understand «three denaries», never «three moneys», which in my opinion makes no sense, in any language.

What can be argued, is whether the primary form of the noun for a concept in a given language is countable or uncountable. «Advice» is uncountable in English because it refers to the general concept and not a single piece of it, and this is why it must resort to other methods to count «advice», just as you would resort to euros, dollars or whatever to count money. However, it is (mostly) countable in Romance languages because it indeed refers to a single piece of advice, and the reverse method to imply the general concept might be pluralizing it, for example.

So it’s not like the same exact concept might be countable or uncountable depending on the language. Just like «eyeglasses» is the same thing worldwide, but different languages have different strategies to mean the same concept, as well as that of a single eyeglass.

— and there is this on a forum (I don’t know if it is speculation or not): The word «Money» is derived from «Mann» in Tamil means Land (more preciously mud)

I don’t know where you got that from but I’m pretty sure it’s false.

Option «Moneta», a given title to a Goddes, as origin of «Money» makes one thinks «money is countable» if Moneta is a person. If not, it is flue.

As I understand it, «moneta» came to mean «mint, currency» after a kind of coincidental geographical reference, just as the name for «silhouette» happens to be a Basque surname, but the origin of that surname doesn’t have anything to do semantically with the word that followed after. So if we are to deduce the countability of the primary concept of «money» in English from etymology, this story starts with «mint, currency». I don’t think this has to do with the discussion, but well.

-

#9

Dymn,

Thanks. I added «length» and «meter, etc» as an analogy to «money» and «dollar, etc», respectively, to my analogy list (liquid, flow, time, length — money.)

But, I am not sure if I understood your second paragraph well. On a coin collectors website, I learnt some coin currency names in ancient Romans time. For example, 1aureus=2quinarii=25denarii=50quinarii=100sestertii=200dupondii=etc… Here, the word «denarii» (plural of denarius) looks similar to the word in Catalan you mentioned «diners» (plural of denary), but, I understand «denarius» in the coin is like «cent» and «denarii» is like «cents», that’s «unit/s» of «money». So, plural tantum «diners» is somethings like that rather than «money»? Or, exactly, «diners=money»?.. I mean, as a conclusion, my question to you to be sure is that «diners» in Catalan is countable or uncountable? If I did understand correctly, «diners too is uncountable», right? (this is important because if «diners» is «countable», or if there is such a word which breaks the rule «money is uncountable», then, the generalization «money (and its any corresponding word in any language in the world) is uncountable» will fail. If this generalization to all languages about «money» is true, then, we can continue as we will have found that «uncountability of money» is valid in all languages.)

Last edited: Aug 17, 2017

-

#10

That you can count the amount of water in milliliters does not make water countable.

Similarly, that you can count the amount of money in dollars does not make money countable.

-

#11

Testing1234567,

Although «length» is already mentioned, ok, «volume» and «liters, etc» too can be added to the analogy list about «money» as some volumes may not have lineer (directly measurable) lengths (eg, a rain droplet, its volume is measured indirectly, by measuring mass and by calculation. Lets add also «mass» and, eg, «kg, etc» as another analogy to «money and dollar».) I guess these analogies/similarities are enough to understand what the money is, from point of view of countability, that also have interactions with languages.

Lets summarize analogies now.

I don’t know if it is a linguistic notation for analogy or not, but, there is a notation not widely known, used for analogy. It is «::»

Lets use it and this mathematical notation «{ }» for set and «( )» for subset.

So, with the criteria «countability», here are some of our analogies:

{MONEY, dollar} :: {(LENGTH, meter), (VOLUME, liter), (MASS, kg), (TIME, minute), (LIQUID, flow-rate), (ELECTRICITY, for ex watthours or joule), … } (*)

Now, with this we have, normally, I should go to a forum where «physics», «economy» and «mathematics» are talked. But, I’ll stay here as we don’t need advance knowledge of physics, economy and mathematics and some elementary knowledge in these fields is sufficent and, main question here is related to what we really understand from «money», relevant to «language».

Ok, up to now, no any counter example (there is a word for «money» in ‘that’ language and it is «countable») has been given, all people here have said «money is uncountable» in all languages. Of course, we may not know all languages details as there are hundreds of languages in the world and not all people in the world is member of this forum. However, to be able to go ahead, following methodology, we need to make an «assumption», by extrapolation «what is known» (money is uncountable) in languages that we know to «what is unknown» (money is uncountable really?) in all languages we don’t know. Supposing this «assumption» (money is uncountable in all languages in the world) is valid, we can go ahead now.

So, we have this analogy list (*) above in our hand now. Since the right hand side of analogy «::» are things known in the physics, for simplicity, we can compare them with money. Are they «really» analogies to «money»? That’s, analogy between {MONEY, dollar} and, for ex, {VOLUME, liter} is crystal clear to you? Probably, so. Indeed, it looks so. It is probably a common view also for mathematicans and for economists who are using some terms such as «cash flow», «liquidity of money», et. and they are doing calculations accordingly, according to comman acceptance, «money is uncountable»… Crystal clear… ?

(if things upto now are ok, then, I’ll continue, later, I need to go out now.)

-

#12

Diner «denary», is a plain countable noun, you can say without any problem tres diners «three denaries». As you would do with any currency, just that this one is obsolete.

But diners «money», even if it derives from a countable noun using a typical method for countable nouns (pluralization), is uncountable. Just because, as a universal idea, you can’t count in a magnitude, you count in units.

I think your analogies are well-founded, they are based on this idea of magnitude-unit pairs.

However I think it is dangerous to say that the «countability» of some words is a universal intrinsic feature. Because the primary word for it may refer to either one single piece or the general concept, and by definition, they are countable and uncountable, respectively, depending on the language.

So we can safely say that «advice» is uncountable in English but countable in Romance languages. However, this is because they do not strictly refer to the same thing. The former refers to the general concept, and the latter to a single piece of it. That’s why, by definition, one is uncountable whereas the other one is countable.

This is just my five cents (pun intended again).

-

#13

Dymn (and, et al.)

Since you frequently warned me about «countability» that may differ from language to language depending on the word (advice, etc), lets fix a thing here first, to avoid bifurcation/branching toward an undesired chaos in our conversation here.

«Countability» here in this topic is narrowed to the countability in money, that is, to «mathematical countability», like counting numbers «1, 2, 3, and so on» that is how we count money by «discretizing» it into some units such as «dollar.»

So, here in this topic, the universality is not the universality (or not) of «countability. Since it is narrowed to money we can write this sentence comfortably, right?

… «uncountability of money is universal in all languages»…

(unless stated otherwise, with a counter-example «word» in a language corresponding to «money».)

Diners in Catalan: So, from whatever it was evoluted, its final form «diners» is equivalent to «money», they both are uncountable. So, we can write analogy above (*) also for «diners as

{DINERS, pesoto/euro now} :: {( ), ( ), … } … (same can be written for any «word» for «money» in any language.)

Since we are using English here in our communication, lets use {MONEY, dollar} pair, also to simplify for those non-members who are surfing, just viewing here shortly, on the net.

Lets summarize all talks here in a single line, by rewriting analogy (*) here again, however, by chosing only one (the best one, most familiar to the common public) of subsets in the set at the right hand side of analogy (*). Result is:

{MONEY, dollar} :: {LIQUID, liter}

where the words in capital letters are uncountable while the words in small letters are countables as they are units.

Lets use «cent» instead of «dollar» as the cent is the real unit value name of that money.

(no need to go into detail of «liter» such as «milliliter, nanoliter, etc» where «milli, nano, etc» are somethings else, irrelevant to the topic.)

So, final simplified version of our analogy is:

{MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter}

This shortened version of analogy conforms also with «mathematical economy» or «economy mathematics» as they use similar terms «liquidity, cash flow, etc.» in their calculations. And, all «money mathematics» is built on this philosophy (or reality?) that says «money is like liquid which is uncountable. Its unit, eg, cent is like liter of liquid which is countable.»

Now, we can talk about this analogy, that simplifies the topic, «money’s uncountability», universal in the languages.

(If there is no any nonagreement at all among all of us, I’ll try to stimulate/stir/blurr this «crystal clear» result. However, later, a cup of coffee time for me.)

Let me rewrite final simplified version of analogy here as last line in this post, as my attemps will be to «break» this analogy «::»

{MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter}

Last edited: Aug 17, 2017

Dib

Senior Member

-

#14

I think, I personally agree with your sets of analogy. I am also okay with building further on the assumption:

Supposing this «assumption» (money is uncountable in all languages in the world) is valid, we can go ahead now.

as long as it is clear that this is purely an assumption — an axiom to build an axiomatic system on. The evidence presented in this thread for its actual validity is negligible. Our sample size and diversity is too low to get any such statistical confidence.

-

#15

Before attempting to «break» this commonly accepted analogy above which I simply write with notation «::», let me tell a little math first for those who may say «how in the world money appears like liquid in mathematics?»

Liquid/fluid/flow. These are «continuum» things and continuum is an uncountable thing according to the physics&mathematics unless it is discretized into pieces.

Mathematicans handling «money» in their calculations see money as a «continuum», such as liquid/fluid/flow, that’s why we hear «liquidity, cash flow, etc» from economists who are using terms of mathematicans&physicist actually.

Ok, garipx, give an example?

Since «countability» is mostly related to «mathematics of numbers», lets write here one simple equation so that you can see «most important numbers» in mathematics, used also in various fields from physics to engineering to economy, etc. in one simple equation. Some of you probably know it.

It is called Euler Identity (EI): e^(i.Pi) + 1 = 0.

where

«e»=2,71828… (three dots mean «etc»)

«i»=square root of «-1», so, imaginary number.

«Pi»=3,14159…

«1» and «0» = you already know.

I won’t go into details of this equation, what the hell this equation in reality is, etc. They are not on-topic here.

I wrote this here just to show «numbers» in one simple line, purposely.

Lets pick «e» here which is called «e»uler number, which is an «irrational number», that’s, numbers after comma never end, that’s, never repeat.

So, we can say this «e» is an uncountable number. And, this «e» is used also in calculations of continuous compound interest rate for your money in the bank account.

So what? What you see in your bank account at the end of a period is, say, $7489,27, but, it is a «cut/rounded» figure. In a mathematican’s hand, this figure is, maybe, «7489,2739340231…» See difference? (forget about «negligibility» here after «0,27…» just because it is «$», we are talking here about «money» and «its un/countability».

Why such a «strange» number «7489,2739340231…» appeared in hands of mathematicans here, specifically in this interest-rate example?

Because they use, for ex, «e» (2,71828…) which is irrational, uncountable number in their money interest rate calculations. Uncountable contiuum such as Liquid/fluid/flow in mathematics appears in such numbers like «e».

So what? Using «e» in bank interest calculations is wrong? It’s another story we can talk later. Point of this post is «how uncountability of money appears in money mathematics». It appears, for ex, in use of number «e» which is uncountable number. We see this now. Money mathematics in detail is not our topic here, we can talk about it elsewhere, or some simple basic things here later.

So, isn’t it good as it fits analogy MONEY::LIQUID well? I can not use the word «certainly» when answering this…

What if this MONEY::LIQUID analogy is not a correct analogy? What happens? Money mathematics will totally fail then? No, but, there will be a «repairement» in «all money mathematics.» And, to do this, we need to be sure if there is any error to be repaired, and we cannot do anything without talking, so, «language», and it is what we are doing now. Having also said these in this post, now, lets question this analogy:

{MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter}

(Ps: Dib, I saw your post when I was writing my this post. Yes, I am aware (you probably are more aware than me as I am not a linguist) of that «sample» info here in this thread is probably insufficient to make such a generalization «uncountability of money is universal in all languages». My assumption here is based on what you posters here said and on the silence not opposing this generalization. So, if we all here and scientists (mathematicans, etc) agree in that assumption, it is not my assumption only. If there is an error or not in this assumption, «uncountability of money is universal», what we will be doing here in this thread is this, questioning, using analogy, as it is done by sciences also about money. Ok, to keep our talks shorter and in a methodology, step by step, lets write this analogy again as last line of this post:

{MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter}

Last edited: Aug 17, 2017

-

#16

(you can go to the bottom, to the last paragraph directly, if you don’t have time to read this long post.)

Instead of this analogy {MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter},

if we chose, for ex, this analogy {MONEY, cent} :: {TIME, minute},

could it be better?

Maybe, but, then, our coversation would have been more conceptual or more philosophical in money-time analogy.

In case of money-liquid analogy, this is quasi-conceptual, less philosophical as liquid has a physical form and money too has a physical form.

Their main common character of money and liquid is their uncountability and this is our main reason for making analogy between them and it is sufficient to chose liquid for our need. Their existing physical forms also keep us in reality more than that we can do with analogy money-time.

So, it is «sufficient best» to take «liquid», among available things, as an analogy to «money» for our purpose here that’s to question «money’s uncountability.»

Now, lets write it here again to focus and question this analogy:

{MONEY, cent} :: {LIQUID, liter}

Here, «cent» and «liter» are to be discussed later as they are obviously «countables»…

Since we are to learn about «money» here that we «suppose» we don’t know, then, we should look at its analogy, i.e. «liquid»…

LIQUID/FLUID/FLOW.

These are terms in the physics. Without going into modern physics, if we make classifications of materials, these are forms of materials in classical physics:

… solid, liquid/fluid, gas …

Solid and liquid/fluid are considered as «contiuum» in classical physics and their math calculations are done accordingly, while gas is considered as «particles» and its math calculations are done accordingly.

So, lets eliminate «gas» as «money» in math calculations is «not» handled like «particles», otherwise, «money» would have been considered as «countable».

Solid does not fit, either, as it doesn’t «flow».

So, we confirm «liquid/fluid», also due to its visible «flowability» character which «money» too has, another commonly accepted property of «money».

These (solid, liquid, gas) forms are forms that have been studied much by many scholars in the history and today. So, we know a lot about these.

NOW…

I’ll write here another «new» material form which has been academically much less studied than those (solid, liquid, gas) and a few years ago, one of few researcher studying that «new» form of material had called it «4th form of material» after 3 forms of materials (solid, liquid, gas).

What is that «new» material form? Don’t be surprised.

WHEAT/GRAIN.

How comes!? This is not new!… Well, that’s why I used » » when I was writing «new». (a little irony, but, still new, as it is new to the science community actually.)

How new?

Question to any person: Wheat/grain is solid? or liquid? or gas-like particle?

Depending on what you are studying, it is solid, and also liquid, and also gas.

You can see these forms in «wheat/grain» with your insight view, and, even eye-visually.

But, since we chosed «liquid/fluid» as analogy to «money», you can ask «how in the world wheat/grain can be correlated to the liquid!?»…

Have you ever seen a combine harvester «pouring» wheat in harvesting or wheat «moving» in an open channel at flour milling factory? Wheat just acts like a liquid, with an engineering approximation, it can also be called «flow» and fluid flow formulas can be used also for «wheat flow» at an engineering approximation level. («approximation» is another keyword here in «money», we may talk about it later.)

Ok, here, not many people may know these matematical formulations of flows, his words of «garipx» may not be enough. It is not necessary to know mathematics of flows, even visually, you can see wheat flow in a channel as «liquid flow», «solid flow» like mud flow in a truck trailer on which wheat flows slowly, and «gas/particle flow» when a handful of wheat is thrown into the air.

SO, BEST ANALOGY for «MONEY» is «WHEAT/GRAIN»… better than «liquid» analogy.

When wheat is handled as a solid, it is «uncountable», it is counted only by its volume/mass/weight (in cubicmeter or kg, lb, etc.)

BUT, because of this way of counting wheat by «kg, etc» in «trade», its countability of wheat/grain as particle «piece» is usually forgotten especially by «scholars» in general and by «mathematicans» in particular in sciences of related fields, again, because of their minds on economy/commerce/trade when they see «money». This countability by «piece» DOES exist also in the countability of «real money», eg, «coin».

SO, here is my claim: instead of this analogy, {Money, cent} :: {Liquid, liter}, this analogy should be used:

{MONEY, cent} :: {WHEAT/GRAIN, piece} … (this will also change «money mathematics» and «money language» as well.)

(Also, it’ll make more sense as «cent» too has a particle physical form, as «coin».)

Here you are… (waiting for your attacks, to the claim here.)

Last edited: Aug 17, 2017

Dib

Senior Member

-

#17

Here you are… (waiting for your attacks, to the claim here.)

My main question to you is: «What does all this have to do with Etymology, History of languages, and Linguistics», please? I hope you are getting to that aspect soon.

Apart from that … I believe, your concept of «countability» as used in Mathematics is unsound. Since there is no such concept in Mathematics as an «uncountable number» as far as I know and «countability» is defined for a set, not a number, when you say:

So, we can say this «e» is an uncountable number.

I guess, you really mean the following:

If the digits of the decimal (or any other rational-base) representation of e are put together in an ordered set (say, X), it will be uncountable.

However, that assertion would be wrong. X will be countably infinite. You can very easily define a one-to-one mapping between the elements of X and the set of all natural numbers, e.g. by using the position of the element in X. That is the classic definition of a countably infinite set.

—

Anyways, I would like to wait to find out what language-related issue this discussion brings up ultimately.

-

#18

Dib,

(I’ll answer your main question «what all these have to do with this EHL forum?» after a few words about «mathematics» you quoted/mentioned.)

I am not a mathematican either though I had used some theoretical pure mathematics in my research studies, about chaos, more than two decades ago.

People, especially pure theoretical mathematicans, say mathematics is «exact» science. Maybe true, maybe not.

But, when it comes to «money» I call their pure theoretical mathematics as «over-engineered» mathematics. What I mean by this is that:

Lets forget «e» (2,71828..etc), instead, lets take another similar number that is related to the term you used «countably infinite».

0,999999999999999999999…(to infinity) = 1.

There is such a claim, whether you call it hypothesis or theorem or law. To me, it is «unprovable» equality as there is «infinity» in this logic of equality.

When it is money, engineering approach is followed, that’s, the number, two digits after comma, is cut. Current reality.

Imagine if our manager in the industry was a mathematican, he would have written money in this form: $0,999999999999…!

This is not «exact» when it is about «money», it is just «over-engineering».

How can we talk about «countability» of this number «0,9999999999999…»? (forget about its potential equivalency to 1. Money is not infinite.)

If this number «0,999999999…» is considered countable, we need to find «99999999999….» (without comma between numbers) by multiplying «10000000…» so that we can reach at a «unit» that is a necessity to call it a countable. So, since we can never make comma disappear in «0,9999999999…», therefore, I call it «uncountable» number. Same happens for «e», «pi», etc.

On the other hand, for example, we can do this eliminating comma for number «325,76». Like we do in «$325,76», when we multiply by «100», «comma» between numbers «325,76» disappears, and, «$325,76» becomes «32576 cents»… This is countable, one by one, as «1,2,3,etc» till we reach «32576».

We can NOT do same operation for «irrational numbers» such as «e» in that numbers after comma never ends, assumption, ends at the infinity, a blurry term.

Ok, but, we use number «infinity» in mathematics? Yes, but, it is not a number actually, just a symbol, an indefinite symbol and all practical calculations using «infinity» are «cut» after a certain order of magnitue level and it is called «approximation.» What is done in money calculations, even if «e» or «infinity» is used in calculations, at the end, cutting two digits after comma, that’s a «centum» level «appromixation.»

Anyway, lets not go further about theoretical mathematics. Fixing this reality is enough, «money is not infinite» which is another thing about «money» that tells us potential countability of money. (with analogy «money::wheat», no more potential, countability of money is real.)

All these mind confusions occuring in money calculations is due to the analogy of «money» to «liquid», handling money as if it is liquid… which is wrong, my claim here.

So, what has these with this EHL forum? We are discussing «un/countability of money» here. I claimed now «money is countable thing» by making a new analogy of «money» to «wheat» unlike standard commonly accepted analogy of «money» to «liquid» which is uncountable.

So, according to analogy «money::liquid», it is «how much money» while according to (new) analogy «money::wheat» it is «how many money».

So, according to this new claim, «how much money» is a historical error in the language (probably by scholars of old old days) to be repaired to «how many money.»… IF my this claim is false, then, prove that «money is uncountable» is true… How can you do that without using mathematics&language? Shall I just simply accept how it has been said throughout the history and today? I question… till «1cent»… When it is said to you «do you have «1cent?», yes, it is a language, but, what do you understand from this? If you «really» have «1cent» in your pocket, you answer it «yes, I have «1cent». But, when you don’t have «1cent», but, when you have «$1», do you still answer «I have 100cent?»… Such an answer, linguistically too, will be illogical. Because you are saying «I have 100cents, but, I don’t have 1cent.»… an illogical saying in a language and this has been said by all in the world and in all time.

So, your main question «what these have to do with EHL» is also answered… As title says, «how many or how much — for money», related to «countability», also according to «linguists». So, before attacking my claim, please, prove «uncountability of money.»

-

#19

There is nothing to be proven. Countability is a property of a concrete concept expressed by a concrete word in a concrete language. In English, money exists as a countable and as a non-countable word. Money in non-countable in sentences like

(1) He had a lot of money.

(2) There was no money on his account.

It is countable in sentences like

(3) The monies raised during the campaign have all been transferred to our CS account.

(4) He kept his fortune in different monies.

The linguistic concept of countability has nothing to do divisibility and has nothing to do with the concept of countability in set theory. A word or, more precisely, a concept X is countable if meaning is attached to the expressions 1X, 2Xs, 3Xs, etc. If money means a quantity of money (as in 1 & 2) then it in non-countable because no natural unit of measurement is attached to the concept. If money means transaction amount (as in 3) or type/kind of money (as in 4) then meaning is attached to expressions one money, two monies etc.

The basic principle of what constitutes a countable and what constitutes a non-countable word is fairly universal. But which concrete words are countable and which are non-countable is language specific. E.g. information is always non-countable in English while the French word information is in most cases countable (with the meaning piece of information).

-

#20

berndf,

When a person just learning English reads your examples (1, 2, 3, 4) may ask «if these told are true or not» (here, «truth» is understood mostly opposite of «lie» in languages, particularly in «spoken languages» and that person would go to the English lesson forum to learn if those (1, 2, 3, 4) are «really» said so or not.

Similarly, he would go to the English forum to learn how people whose native language is English say for «money», «much money» or «many money».

Such things are «information gathering» in «already available» things, but, unknown to a new learner.

Although I don’t speak English well either I (and also everybody here) had already passed that stage, we all already know English people are using «much money», not «many money. If it was said it is «subjective», that’s is a matter of personal/national/etc taste, it would be non-discussable. But, there is a generalization here, with respect to «countability». When it is narrowed to «money it becomes «uncountability of money is universal»… a generalization …

(Btw, I’ll keep using «uncountability» instead of «non-countability» whichever is said by English people is not our main topic here, I guess everybody understands «uncountability» as opposite of «countability.»)

So, this «uncountability of money is universal» requires a proof, a proof even in only English. That should be done like a mathematican does to prove «2+2=4» which is well known. Saying that «countability in mathematics and in linguistics is different» does not make sense, at least in this topic in which the thing we are talking is «money» which is considered same thing for the both, for the mathematican and for the linguist, for all others as well.

What are the language and the mathematics? (related to countability). With simple examples.

1tulip + 1rose = 2flowers… Here, what takes my attention is «tulip and rose», their odor/smell/beauty/etc rather than their quantities/mathematics.

1tulip + 1tulip = 2tulips… Here, what takes my attention is numbers/figures as all units/names (tulip) are same.

1money + 1money = 2money/s… Here, my eyes are opened wider because it is about «money» and people immediately «jump» to the total «2moneys» as it is bigger number (economy motivation).

,

These are about «money» and «countability» with letters/notations/symbols, partically from linguistics and partially from mathematics.

How these letters/notations/symbols are related?

Right now, I just said somethings here in my room, you didn’t hear. What did I say? Exactly what I said can never be known unless you hear with your own ears.

Still, I can try to tell what I said, from «beginning.»

I said this: [ ~~~~~~~~ ~~~ ~~ ~~~~~ ] where «~~»s are voice/sound waves (this can not be heard through the internet.)

-> (transformation operation through an electrical/electronical tool) ->

I said this: {><><><>< ><> <> ><><} where «><«are «discretized waves» (ok, this sound record option does not exist here on WR forum.)

-> (transformation operation by hand fingers using linguistics symbols and notations) ->

I said this: [yesterday, I picked one apple from a tree. Today, I got one apple in the morning and one apple in the afternoon. So, I got three apples in total.] (now, you read and you know what I said with our communication tool here with linguistics symbols/etc.]

But, it is a too long sentence, and, some maybe interested in «picking», some maybe interested in «tree», some maybe interested in «who/when», etc., but, our topic here in this thread is not about these, so, some (mathematicans) may say «hey, garipx, lets write it shorter by using some other symbols/notations.»

-> (a transformation operation of some linguistics symbols to mathematical symbols, for ex, «one to 1») ->

I said this: «1apple + (1apple+1apple) = (1+1+1)apples.» — (See initially we know only «1» as it was in sentence above as «one»)

Now, someone introduces some new symbols (by saying lets show 1+1 with a new symbol «2», etc:

I said this: «1apple + 2apples = 3apples»

Now, someone generalizes and omits «apples» as they are invariants/same:

I said this: «1 + 2 = 3″…

So, where the «countability» did start in this what I said? It started when the word «one» is used. Mathematics just used another symbol for it, as «1», so that a paragraph of letters/words/sentences/symbols can be shortened into a single line, usually called «equation». So, the linguistics and the mathematics are in the same group, according to the criteria «countability». A saying that «we linguists see countability differently than mathematicans or vice versa» doesn’t make sense in this particular case, espeically when it is related to the «money» and its «un/countability».

Now.

Instead of saying «apple» in which «countability» is clear, what if I said «wheat»?…

(same question questioned for «money»: «wheat too is un/countable» like it is said for «money» which is used to seen as «liquid», which is wrong according to the claim here.) This paragraph is the heart of this topic here as this new «money::wheat» analogy proposal can clean all errors in «money language».

Ps: btw, a math prof from a USA university, and also an «old» engineer still working at the industry, maybe viewing here as they were viewing a similar thread by «ErolGarip» on a non-commercial forum (a coin collector forum) where I put a link of this thread there in the public. If it’s not a problem to put a link of that other thread here, I can do that too. However, that other thread on another forum is less academical than here.

Last edited: Aug 18, 2017

-

#21

Perhaps, before this new claim <«money::wheat» analogy is a proper/better analogy comparing with commonly used analogy «money::liquid»>,

this must be repeated/emphasized:

IF «uncountability of money is universal» … is valid, as universal as … «2 + 2 = 4» , it should be proved.

I’ve seen many proofs of «2 + 2 = 4» using simple elementary school mathematics to using advanced level mathematics. At the end, it is doubtless.

But, I have never seen any proof about «uncountability of money is universal», even no any attempt by any experts in linguistics/mathematics/economy/etc.

So, there is a doubt in that commonly(?) accepted expression about money’s uncountability.

When that doubt is questioned further it can be seen that it is not a pointless doubt.

-

#22

But, I have never seen any proof about «uncountability of money is universal»

Nobody said it was. Countability is always language dependent and many languages (including English) allow context where the respective words for money are countable. If a word X expresses a countable concept this means no more and no less than that the language assigns meaning to 1X and 2Xs. It is entirely specific to the language in question if this is the case or not.

That being said, most languages express the concept of money most of the time as non-countable.

-

#23

… languages express the concept of money most of the time as non-countable.

Most of the time? So, there are «exceptions» which break the universal rule «money is non-countable» and some examples in your previous post: (lets take here)

It is countable in sentences like

(3) The monies raised during the campaign have all been transferred to our CS account.

(4) He kept his fortune in different monies.

In (3): Instead of saying «The monies raised during…», if it is said «The money raised during … «, then, it is wrong? If wrong, why? If not wrong, then, there is no difference between «money» and «monies»?

In (4): ok, I see, it is «monies» because there are different kinds/types of money. Different type/kind of «monies» you mean are probably, for ex, «dollar and euro» or «dollar or cent», etc. This is probably more clear to the public. Whether it is correct or not is another issue now, however, still informative about how «money» is seen over there by people whose native languages is English. Anyway, I «reserve» this different «kind/type» of money for conversation later. For the moment, questions on (3) are more important.

-

#24

In (3): Instead of saying «The monies raised during…», if it is said «The money raised during … «, then, it is wrong? If wrong, why? If not wrong, then, there is no difference between «money» and «monies»?

Both are possible. There is a slight but noticable difference in meaning. The money raised… describes the total amount as a single quantity that was transferred to that account. The monies raised… emphasises that there were several different payments received at different times and/or from different sources and that each of them have been transferred to that account.

-

#25

The monies raised… emphasises that there were several different payments received at different times and/or from different sources…

So, what you said is somethings like this: «The money (received from different sources) raised…» — changed to — «The monies raised …»

This is somethings like a modern «agglunitation» which shortens a longer expression by adding some suffixes at the end of words, in this case, plurality in source»s» is added to the end of «money» and changed it to «monies.»

I tried, I forced myself, to understand why «The monies…» and reached at such a conclusion.

However, if it is not a grammatical error like in this: «That trader made much money» which is grammatically incorrect. But, «to make money» still entered into the modern English, a century ago or two, right?. (He is a trader, not someone working in a mint where money is made. However, we are «thoughtful» for ordinary folks or whoever started to use it and any wrong use in the language doesn’t matter since it is about «money» which is important thing, we can forget/forgive any and all grammatical errors.)

In such expressions, «money» or «monies» are really meant «money»? or, somethings else?

In Turkish too, there are similar expressions, for ex, «gelsin paralar (plural)» instead of «gelsin para», similarly, «para+lar» implies «different sources».

Maybe, adding plurality (suffices; -s/lar/etc) to «money» may not be «modern agglunitation». It may also be because of «confusion» about «money» and it is heard from their tongues of ordinary folks. Their such uses (money or monies) may not effect the life, but, in academic environments such as mathematics/economy/linguistics/etc, particularly in mathematics, how the term «money» is handled is important as their formulae has much influence on the life of people. For example, continuous interest rate calculation has so-called number «e» which is not a number actually and which indicates «uncountability of money» error in their calculations… So, before educating folks, academic community too should question their own view of «money» first.

By the way, «monies» fit my counter-claim «money is countable» (in the new proposed analogy, «money::wheat» against «money::liquid»).

But, if you don’t (prefer to) see that wheat is made of grains/particles (countables), if you see «wheat» as a whole, for ex, as a bag/truck of wheat, then, you see it as a «mass» and you weigh it in «kg/ton» because «counting wheat one by one» is a «mess» for you, you can say «wheat is uncountable». Then, the rest is «easier work». Really!? It is the same reason, lazyness, in saying «money is uncountable.» (Anyway, I also have a proposal against such a lazyness to make things «easier for minds», but, «harder for bodies». Later.)

-

#26

I just finished reading many posts on many forums. Some of them are forums for teaching English to foreigners, some are forums for teaching English to their kids, some are economy forums, some are chat forums, etc.

Some examples on how they answer «money is countable or uncountable» are:

Some answer (especially on educational English forums) «We don’t say 1money, 2moneys, etc., therefore, money is uncountable.»

I pass such explanations.

Some answer «We don’t say moneys or monies, therefore, money is not countable.»

I also pass such explanations.

Most answer «Money, like water/sugar/furniture/etc, is an uncountable noun.»

Most common answers are like this. Answers here too were same or similar, explanations by analogies.

Some other answer «monies/moneys is sometimes/rarely used and it is in modern English as «sum of money» and in economy context by economists for different types/kinds of currencies such as Dollar, Euro, etc.

A very few people answer «monies were frequently used in old days in the history when people were mostly poor, when they had little money.»

Probably, she/he saw that word «monies» in some very old books/writings reprinted later.

So, from language history point of view, the word «money» has changed from countable noun (from many monies) to uncountable noun (to much money).

This is logical because there were not many kinds/types/denominations of money in ancient days.

(To support this, in this thread on a coin collecting forum, «ancient» forms of money are also asked by «Garip»; Coin without any number/figure? | Page 6 | Coin Talk )

For example, oldest known coin, Lydia coin with a lion figure on it dated around 700 BC, has no any numeral such as «5» or in word «five» or some other things to apart it from other coins.

So, in early days of «money», there was only single coin type in a place and the original form of noun «money» was a countable noun, highly likely.

(how long in the past have linguists gone about the origin of word «money»? Around 300 BC, her time of Goddess Juno «Moneta» which is said to be origin of word «money». So, «the money» we use is not name of real money, it is just name/title of a goddess/queen, ok, that is another story.)

What was the real money in early days of money? It was a coin only, a single type of coin. Its meaning of «money» has changed in time? Maybe, but, it is still a concrete item. Think about «1cent» coin. (or, its equivalents such as 1penny, 1agora, 1kurus, 1yen, 1kapik, etc.) which I can name «1coin» or even «1money»

It is the only real money. All other forms (5cents, 25cents, 1dollar=100cents, 5dollars=500cents, etc) are «variable» various forms of money while 1cent=1coin=1money is «constant» of money. (ok, I stop here, not to go off-topic, more on such things are posted in that forum thread with its link above.)

All these being said, conclusion is:

the generalization «money is uncountable noun» by drawing analogies to liquid/water/etc is not valid and money can be countable. (yes, so, acc to analogy, «money::wheat» and mathematical model of money according to this analogy will change things.)

-

#27

So, from language history point of view, the word «money» has changed from countable noun (from many monies) to uncountable noun (to much money).

No. They have always been distinct uses.

money is uncountable noun» by drawing analogies to liquid/water/etc is not valid and money can be countable.

Water can be countable the same way as money: (3) The waters are streaming and (4) He tasted different waters.

-

#28

No. They have always been distinct uses.

You are just saying without any proof, without any evidence. I am bringing some evidences. For example: