We hear this word very often in our life, but we even do not think, what does it mean. We used to think, that it is something, that everyone like and that is all. If we ask any person what is beauty for him, he can name a lot of things, but it will be very difficult to explain, why he considers that they are beautiful.

What Beauty For You mean ?

The definition of the word “beauty” is an aesthetically pleasing feature of an object or a person. The word “beauty” holds a distinctive positive meaning if applied to a person. It means that the character or the physical appearance of said individual is considered as beautiful in the speaker’s opinion. The definition of beauty is usually considered as subjective.

If we speak in general, when you see something and you are glad to see it, then we can say, that it is beautiful. There is no matter it it is the field with the flowers or the exotic bird, it is the beauty for us.

But the definition of the beauty is different for everyone, because everyone has his/her own point of view and all people are different, because of it they cannot like the same things. Also, it depends on the culture and on the level of the development of the person. For example, some men like blond women, but some of them just hate when the woman has blond hair. There can be a lot of discussions about personal point of view of every person and there will not be the winner. If your teacher asked you to write the beauty definition essay and you do not know where to start from, you can place the order on our site and we will write this essay for you. You can be sure, that you will get the high quality paper, because we have only professional writers with the great experience.

This example can be also connected with the clothes. For example, you like something in the shop and you think, that it is really beautiful and can be even your favorite one, but at the same time, your friend can say, that this thing is awful and she does not understand how you can even think to purchase it. It should not be like a shock, because it is just the personal statement and as all people are different, it is normal that they all think in the different way and have different point of view.

There are a lot of examples of the beauty which we can meet in our world. Even if we look through the history, we will see, that people liked to be the slaves of the beauty during many generations. But if there was one person, who showed the other point of view, the society did not accept him, but it was only the fact, that this person is individual and did not think like the other people.

The definition of the word “beauty” is an aesthetically pleasing feature of an object or a person. This word holds a distinctive positive meaning if applied to a person. It means that the character or the physical appearance of said individual is considered as attractive in the speaker’s opinion.

How to correctly define the meaning of beauty.

Everyone today can look up the word “beauty” in a dictionary and get to know its definition. But what about the concept itself? Why is it often said that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder? This article will help you understand why beauty is so ephemeral.

If you ask anyone about what they can consider as beautiful, you will get an uncountable number of answers. Sure, some of them would sound similar, but the fundamental reasoning behind them would hugely differ from each other. For example, the beauty standards for men and women underwent a significant change throughout the existence of humankind.

As they say – for each their own. Many kinds of material or spiritual events, objects, or even their aesthetic can be considered beautiful for different personal reasons, views, or opinions. Even if two people like the same thing, it is not always the case that they consider it as likable for the same reasons.

Every single person in the world is unique and has his or her own set of experiences, beliefs, or principles. Each human possesses a distinctive and intricate identity, which is impossible to classify by any means one can come up with.

The only thing you can truly figure out for sure is that every similarity between human personalities is only superficial.

Here we provided you with a short list of what may be distinguished as beautiful. This will help you understand the point that we are trying to make in this article.

- The external features of the human body. There is no need to explain how much consideration every person gives to this subject. The skin tone, hair color, or even the quantity of a body fat one can be thoroughly examined by a lot of people to decide if the person in question is beautiful or not.

- Any characteristic that can be applied to a physical object. Its shape, color, softness, hardness, or transparency can be measured and judged as pleasing to the senses or hideous and ugly.

- Such an intangible thing as sound can also be beautiful. If you hear a delicate and alluring melody, you would state that it is definitely more beautiful than the sound of nails on the chalkboard.

- The aesthetic of any kind is, without a doubt, belongs to the category of things that can be acknowledged as grand and wonderful.

This is just a small portion from a wide variety of instances where the idea of beauty can be implemented.

The inner beauty

What is the inner beauty?

A lot of people can even forget, that the important role plays not only beautiful body, but the beautiful soul too. It is impossible to have a lot of beautiful clothes, but at that time to forget, that all we are human. And it is impossible to say, that one person is better that the other one. It is not true. We all are different, and it is very good, because if we were the same, we would not try to develop ourselves in the best way and we would not want to change our life. If you wish to get the inner beauty essay, you can order it on our site and we will be glad to create the best essay with all detailed information you wish to know. Also, you will be really surprised because of our prices. You can just check our site and you will be able to see the examples of our essays on the different topics. We hope, that you will find the needed information there. Also, you can order the essay on any other theme on our site. It will be a pleasure for us to do it for you.

The main sides of the inner beauty

- When people are very kind to other people or animals

- They are ready for help other people

- These people are open to the whole world

- High IQ level

- You can see, that they are honest.

What can you get?

The beauty plays a very big role exactly for women. It is believed, that if the woman is beauty, she can have a good husband and the great job. If the girl would like to be a model, it is needed to be beautiful, because everyone will see you and you will be famous. Also, if the woman would like to get, for example, the position of the secretary in some huge and famous company, it means that she should be beautiful, because she will be “ the face” of the company and she will meet a lot of people.

The health and the beauty

Do not you notice, that people, which are healthy, are beautiful? These people are very attractive for the society. They do not need to use a lot of cosmetics or to purchase expensive and brand clothes. They do some physical exercises and just eat healthy food, because of it they are beautiful. It is very important to understand, that the beauty starts inside of you and only you are responsible for it.

There are a lot of definitions, which are connected with the beauty. For example: beautiful life, natural beauty, beautiful soul, which you cannot hide from the other people. But everyone should understand, that there is no need just to follow the other people, it is needed to find something that you really like and to find the definition of the beauty which will be exactly for you. And then, even the things, which are usual, will be beautiful. We are sure, that this 5 paragraph essay on beauty will help you to understand this world better and will help you not just to follow the ideals, which people created, but to find your own definition of the beauty, that you will use for the whole life.

Beauty is commonly described as a feature of objects that makes these objects pleasurable to perceive. Such objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty, together with art and taste, is the main subject of aesthetics, one of the major branches of philosophy. As a positive aesthetic value, it is contrasted with ugliness as its negative counterpart.

One difficulty in understanding beauty is because it has both objective and subjective aspects: it is seen as a property of things but also as depending on the emotional response of observers. Because of its subjective side, beauty is said to be «in the eye of the beholder».[2] It has been argued that the ability on the side of the subject needed to perceive and judge beauty, sometimes referred to as the «sense of taste», can be trained and that the verdicts of experts coincide in the long run. This would suggest that the standards of validity of judgments of beauty are intersubjective, i.e. dependent on a group of judges, rather than fully subjective or fully objective.

Conceptions of beauty aim to capture what is essential to all beautiful things. Classical conceptions define beauty in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole. Hedonist conceptions see a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause disinterested pleasure. Other conceptions include defining beautiful objects in terms of their value, of a loving attitude towards them or of their function.

Overview

Beauty, together with art and taste, is the main subject of aesthetics, one of the major branches of philosophy.[3][4] Beauty is usually categorized as an aesthetic property besides other properties, like grace, elegance or the sublime.[5][6][7] As a positive aesthetic value, beauty is contrasted with ugliness as its negative counterpart. Beauty is often listed as one of the three fundamental concepts of human understanding besides truth and goodness.[5][8][6]

Objectivists or realists see beauty as an objective or mind-independent feature of beautiful things, which is denied by subjectivists.[3][9] The source of this debate is that judgments of beauty seem to be based on subjective grounds, namely our feelings, while claiming universal correctness at the same time.[10] This tension is sometimes referred to as the «antinomy of taste».[4] Adherents of both sides have suggested that a certain faculty, commonly called a sense of taste, is necessary for making reliable judgments about beauty.[3][10] David Hume, for example, suggests that this faculty can be trained and that the verdicts of experts coincide in the long run.[3][9]

Beauty is mainly discussed in relation to concrete objects accessible to sensory perception. It has been suggested that the beauty of a thing supervenes on the sensory features of this thing.[10] It has also been proposed that abstract objects like stories or mathematical proofs can be beautiful.[11] Beauty plays a central role in works of art and nature.[12][10]

An influential distinction among beautiful things, according to Immanuel Kant, is that between dependent and free beauty. A thing has dependent beauty if its beauty depends on the conception or function of this thing, unlike free or absolute beauty.[10] Examples of dependent beauty include an ox which is beautiful as an ox but not beautiful as a horse[3] or a photograph which is beautiful, because it depicts a beautiful building but that lacks beauty generally speaking because of its low quality.[9]

Objectivism and subjectivism

Judgments of beauty seem to occupy an intermediary position between objective judgments, e.g. concerning the mass and shape of a grapefruit, and subjective likes, e.g. concerning whether the grapefruit tastes good.[13][10][9] Judgments of beauty differ from the former because they are based on subjective feelings rather than objective perception. But they also differ from the latter because they lay claim on universal correctness.[10] This tension is also reflected in common language. On the one hand, we talk about beauty as an objective feature of the world that is ascribed, for example, to landscapes, paintings or humans.[14] The subjective side, on the other hand, is expressed in sayings like «beauty is in the eye of the beholder».[3]

These two positions are often referred to as objectivism (or realism) and subjectivism.[3] Objectivism is the traditional view, while subjectivism developed more recently in western philosophy. Objectivists hold that beauty is a mind-independent feature of things. On this account, the beauty of a landscape is independent of who perceives it or whether it is perceived at all.[3][9] Disagreements may be explained by an inability to perceive this feature, sometimes referred to as a «lack of taste».[15] Subjectivism, on the other hand, denies the mind-independent existence of beauty.[5][3][9] Influential for the development of this position was John Locke’s distinction between primary qualities, which the object has independent of the observer, and secondary qualities, which constitute powers in the object to produce certain ideas in the observer.[3][16][5] When applied to beauty, there is still a sense in which it depends on the object and its powers.[9] But this account makes the possibility of genuine disagreements about claims of beauty implausible, since the same object may produce very different ideas in distinct observers. The notion of «taste» can still be used to explain why different people disagree about what is beautiful, but there is no objectively right or wrong taste, there are just different tastes.[3]

The problem with both the objectivist and the subjectivist position in their extreme form is that each has to deny some intuitions about beauty. This issue is sometimes discussed under the label «antinomy of taste».[3][4] It has prompted various philosophers to seek a unified theory that can take all these intuitions into account. One promising route to solve this problem is to move from subjective to intersubjective theories, which hold that the standards of validity of judgments of taste are intersubjective or dependent on a group of judges rather than objective. This approach tries to explain how genuine disagreement about beauty is possible despite the fact that beauty is a mind-dependent property, dependent not on an individual but a group.[3][4] A closely related theory sees beauty as a secondary or response-dependent property.[9] On one such account, an object is beautiful «if it causes pleasure by virtue of its aesthetic properties».[5] The problem that different people respond differently can be addressed by combining response-dependence theories with so-called ideal-observer theories: it only matters how an ideal observer would respond.[10] There is no general agreement on how «ideal observers» are to be defined, but it is usually assumed that they are experienced judges of beauty with a fully developed sense of taste. This suggests an indirect way of solving the antinomy of taste: instead of looking for necessary and sufficient conditions of beauty itself, one can learn to identify the qualities of good critics and rely on their judgments.[3] This approach only works if unanimity among experts was ensured. But even experienced judges may disagree in their judgments, which threatens to undermine ideal-observer theories.[3][9]

Conceptions

Various conceptions of the essential features of beautiful things have been proposed but there is no consensus as to which is the right one.

Classical

The «classical conception»[further explanation needed] defines beauty in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.[3][5][9] On this account, which found its most explicit articulation in the Italian Renaissance, the beauty of a human body, for example, depends, among other things, on the right proportion of the different parts of the body and on the overall symmetry.[3] One problem with this conception is that it is difficult to give a general and detailed description of what is meant by «harmony between parts» and raises the suspicion that defining beauty through harmony results in exchanging one unclear term for another one.[3] Some attempts have been made to dissolve this suspicion by searching for laws of beauty, like the golden ratio.

18th century philosopher Alexander Baumgarten, for example, saw laws of beauty in analogy with laws of nature and believed that they could be discovered through empirical research.[5] As of 2003, these attempts have failed to find a general definition of beauty and several authors take the opposite claim that such laws cannot be formulated, as part of their definition of beauty.[10]

Hedonism

A very common element in many conceptions of beauty is its relation to pleasure.[11][5] Hedonism makes this relation part of the definition of beauty by holding that there is a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause pleasure or that the experience of beauty is always accompanied by pleasure.[12] This account is sometimes labeled as «aesthetic hedonism» in order to distinguish it from other forms of hedonism.[17][18] An influential articulation of this position comes from Thomas Aquinas, who treats beauty as «that which pleases in the very apprehension of it».[19] Immanuel Kant explains this pleasure through a harmonious interplay between the faculties of understanding and imagination.[11] A further question for hedonists is how to explain the relation between beauty and pleasure. This problem is akin to the Euthyphro dilemma: is something beautiful because we enjoy it or do we enjoy it because it is beautiful?[5] Identity theorists solve this problem by denying that there is a difference between beauty and pleasure: they identify beauty, or the appearance of it, with the experience of aesthetic pleasure.[11]

Hedonists usually restrict and specify the notion of pleasure in various ways in order to avoid obvious counterexamples. One important distinction in this context is the difference between pure and mixed pleasure.[11] Pure pleasure excludes any form of pain or unpleasant feeling while the experience of mixed pleasure can include unpleasant elements.[20] But beauty can involve mixed pleasure, for example, in the case of a beautifully tragic story, which is why mixed pleasure is usually allowed in hedonist conceptions of beauty.[11]

Another problem faced by hedonist theories is that we take pleasure from many things that are not beautiful. One way to address this issue is to associate beauty with a special type of pleasure: aesthetic or disinterested pleasure.[3][4][7] A pleasure is disinterested if it is indifferent to the existence of the beautiful object or if it did not arise owing to an antecedent desire through means-end reasoning.[21][11] For example, the joy of looking at a beautiful landscape would still be valuable if it turned out that this experience was an illusion, which would not be true if this joy was due to seeing the landscape as a valuable real estate opportunity.[3] Opponents of hedonism usually concede that many experiences of beauty are pleasurable but deny that this is true for all cases.[12] For example, a cold jaded critic may still be a good judge of beauty because of her years of experience but lack the joy that initially accompanied her work.[11] One way to avoid this objection is to allow responses to beautiful things to lack pleasure while insisting that all beautiful things merit pleasure, that aesthetic pleasure is the only appropriate response to them.[12]

Others

G. E. Moore explained beauty in regard to intrinsic value as «that of which the admiring contemplation is good in itself».[21][5] This definition connects beauty to experience while managing to avoid some of the problems usually associated with subjectivist positions since it allows that things may be beautiful even if they are never experienced.[21]

Another subjectivist theory of beauty comes from George Santayana, who suggested that we project pleasure onto the things we call «beautiful». So in a process akin to a category mistake, one treats one’s subjective pleasure as an objective property of the beautiful thing.[11][3][5] Other conceptions include defining beauty in terms of a loving or longing attitude towards the beautiful object or in terms of its usefulness or function.[3][22] In 1871, functionalist Charles Darwin explained beauty as result of accumulative sexual selection in «The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex».[5]

In philosophy

Greco-Roman tradition

The classical Greek noun that best translates to the English-language words «beauty» or «beautiful» was κάλλος, kallos, and the adjective was καλός, kalos. However, kalos may and is also translated as «good» or «of fine quality» and thus has a broader meaning than mere physical or material beauty. Similarly, kallos was used differently from the English word beauty in that it first and foremost applied to humans and bears an erotic connotation.[23] The Koine Greek word for beautiful was ὡραῖος, hōraios,[24] an adjective etymologically coming from the word ὥρα, hōra, meaning «hour». In Koine Greek, beauty was thus associated with «being of one’s hour».[25] Thus, a ripe fruit (of its time) was considered beautiful, whereas a young woman trying to appear older or an older woman trying to appear younger would not be considered beautiful. In Attic Greek, hōraios had many meanings, including «youthful» and «ripe old age».[25] Another classical term in use to describe beauty was pulchrum (Latin).[26]

Beauty for ancient thinkers existed both in form, which is the material world as it is, and as embodied in the spirit, which is the world of mental formations.[27] Greek mythology mentions Helen of Troy as the most beautiful woman.[28][29][30][31][32] Ancient Greek architecture is based on this view of symmetry and proportion.

Pre-Socratic

In one fragment of Heraclitus’s writings (Fragment 106) he mentions beauty, this reads: «To God all things are beautiful, good, right…»[33] The earliest Western theory of beauty can be found in the works of early Greek philosophers from the pre-Socratic period, such as Pythagoras, who conceived of beauty as useful for a moral education of the soul.[34] He wrote of how people experience pleasure when aware of a certain type of formal situation present in reality, perceivable by sight or through the ear[35] and discovered the underlying mathematical ratios in the harmonic scales in music.[34] The Pythagoreans conceived of the presence of beauty in universal terms, which is, as existing in a cosmological state, they observed beauty in the heavens.[27] They saw a strong connection between mathematics and beauty. In particular, they noted that objects proportioned according to the golden ratio seemed more attractive.[36]

Classical period

The classical concept of beauty is one that exhibits perfect proportion (Wolfflin).[37] In this context, the concept belonged often within the discipline of mathematics.[26] An idea of spiritual beauty emerged during the classical period,[27] beauty was something embodying divine goodness, while the demonstration of behaviour which might be classified as beautiful, from an inner state of morality which is aligned to the good.[38]

The writing of Xenophon shows a conversation between Socrates and Aristippus. Socrates discerned differences in the conception of the beautiful, for example, in inanimate objects, the effectiveness of execution of design was a deciding factor on the perception of beauty in something.[27] By the account of Xenophon, Socrates found beauty congruent with that to which was defined as the morally good, in short, he thought beauty coincident with the good.[39]

Beauty is a subject of Plato in his work Symposium.[34] In the work, the high priestess Diotima describes how beauty moves out from a core singular appreciation of the body to outer appreciations via loved ones, to the world in its state of culture and society (Wright).[35] In other words, Diotoma gives to Socrates an explanation of how love should begin with erotic attachment, and end with the transcending of the physical to an appreciation of beauty as a thing in itself. The ascent of love begins with one’s own body, then secondarily, in appreciating beauty in another’s body, thirdly beauty in the soul, which cognates to beauty in the mind in the modern sense, fourthly beauty in institutions, laws and activities, fifthly beauty in knowledge, the sciences, and finally to lastly love beauty itself, which translates to the original Greek language term as auto to kalon.[40] In the final state, auto to kalon and truth are united as one.[41] There is the sense in the text, concerning love and beauty they both co-exist but are still independent or, in other words, mutually exclusive, since love does not have beauty since it seeks beauty.[42] The work toward the end provides a description of beauty in a negative sense.[42]

Plato also discusses beauty in his work Phaedrus,[41] and identifies Alcibiades as beautiful in Parmenides.[43] He considered beauty to be the Idea (Form) above all other Ideas.[44] Platonic thought synthesized beauty with the divine.[35] Scruton (cited: Konstan) states Plato states of the idea of beauty, of it (the idea), being something inviting desirousness (c.f seducing), and, promotes an intellectual renunciation (c.f. denouncing) of desire.[45] For Alexander Nehamas, it is only the locating of desire to which the sense of beauty exists, in the considerations of Plato.[46]

Aristotle defines beauty in Metaphysics as having order, symmetry and definiteness which the mathematical sciences exhibit to a special degree.[37] He saw a relationship between the beautiful (to kalon) and virtue, arguing that «Virtue aims at the beautiful.»[47]

Roman

In De Natura Deorum Cicero wrote: «the splendour and beauty of creation», in respect to this, and all the facets of reality resulting from creation, he postulated these to be a reason to see the existence of a God as creator.[48]

Western Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, Catholic philosophers like Thomas Aquinas included beauty among the transcendental attributes of being.[49] In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas described the three conditions of beauty as: integritas (wholeness), consonantia (harmony and proportion), and claritas (a radiance and clarity that makes the form of a thing apparent to the mind).[50]

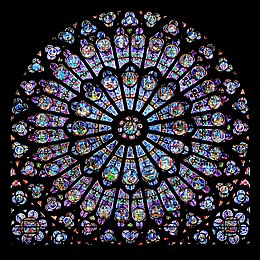

In the Gothic Architecture of the High and Late Middle Ages, light was considered the most beautiful revelation of God, which was heralded in design.[1] Examples are the stained glass of Gothic Cathedrals including Notre-Dame de Paris and Chartres Cathedral.[51]

St. Augustine said of beauty «Beauty is indeed a good gift of God; but that the good may not think it a great good, God dispenses it even to the wicked.»[52]

Renaissance

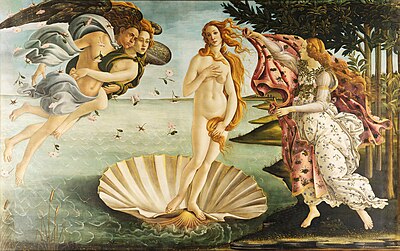

Classical philosophy and sculptures of men and women produced according to the Greek philosophers’ tenets of ideal human beauty were rediscovered in Renaissance Europe, leading to a re-adoption of what became known as a «classical ideal». In terms of female human beauty, a woman whose appearance conforms to these tenets is still called a «classical beauty» or said to possess a «classical beauty», whilst the foundations laid by Greek and Roman artists have also supplied the standard for male beauty and female beauty in western civilization as seen, for example, in the Winged Victory of Samothrace. During the Gothic era, the classical aesthetical canon of beauty was rejected as sinful. Later, Renaissance and Humanist thinkers rejected this view, and considered beauty to be the product of rational order and harmonious proportions. Renaissance artists and architects (such as Giorgio Vasari in his «Lives of Artists») criticised the Gothic period as irrational and barbarian. This point of view of Gothic art lasted until Romanticism, in the 19th century. Vasari aligned himself to the classical notion and thought of beauty as defined as arising from proportion and order.[38]

Age of Reason

The Age of Reason saw a rise in an interest in beauty as a philosophical subject. For example, Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson argued that beauty is «unity in variety and variety in unity».[54] He wrote that beauty was neither purely subjective nor purely objective—it could be understood not as «any Quality suppos’d to be in the Object, which should of itself be beautiful, without relation to any Mind which perceives it: For Beauty, like other Names of sensible Ideas, properly denotes the Perception of some mind; … however we generally imagine that there is something in the Object just like our Perception.»[55]

Immanuel Kant believed that there could be no «universal criterion of the beautiful» and that the experience of beauty is subjective, but that an object is judged to be beautiful when it seems to display «purposiveness»; that is, when its form is perceived to have the character of a thing designed according to some principle and fitted for a purpose.[56] He distinguished «free beauty» from «merely dependent beauty», explaining that «the first presupposes no concept of what the object ought to be; the second does presuppose such a concept and the perfection of the object in accordance therewith.»[57] By this definition, free beauty is found in seashells and wordless music; dependent beauty in buildings and the human body.[57]

The Romantic poets, too, became highly concerned with the nature of beauty, with John Keats arguing in Ode on a Grecian Urn that:

- Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all

- Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Western 19th and 20th century

In the Romantic period, Edmund Burke postulated a difference between beauty in its classical meaning and the sublime.[58] The concept of the sublime, as explicated by Burke and Kant, suggested viewing Gothic art and architecture, though not in accordance with the classical standard of beauty, as sublime.[59]

The 20th century saw an increasing rejection of beauty by artists and philosophers alike, culminating in postmodernism’s anti-aesthetics.[60] This is despite beauty being a central concern of one of postmodernism’s main influences, Friedrich Nietzsche, who argued that the Will to Power was the Will to Beauty.[61]

In the aftermath of postmodernism’s rejection of beauty, thinkers have returned to beauty as an important value. American analytic philosopher Guy Sircello proposed his New Theory of Beauty as an effort to reaffirm the status of beauty as an important philosophical concept.[62][63] He rejected the subjectivism of Kant and sought to identify the properties inherent in an object that make it beautiful. He called qualities such as vividness, boldness, and subtlety «properties of qualitative degree» (PQDs) and stated that a PQD makes an object beautiful if it is not—and does not create the appearance of—»a property of deficiency, lack, or defect»; and if the PQD is strongly present in the object.[64]

Elaine Scarry argues that beauty is related to justice.[65]

Beauty is also studied by psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of experimental aesthetics and neuroesthetics respectively. Psychological theories see beauty as a form of pleasure.[66][67] Correlational findings support the view that more beautiful objects are also more pleasing.[68][69][70] Some studies suggest that higher experienced beauty is associated with activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex.[71][72] This approach of localizing the processing of beauty in one brain region has received criticism within the field.[73]

Philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco wrote On Beauty: A History of a Western Idea (2004)[74] and On Ugliness (2007).[75] The narrator of his novel The Name of the Rose follows Aquinas in declaring: «three things concur in creating beauty: first of all integrity or perfection, and for this reason, we consider ugly all incomplete things; then proper proportion or consonance; and finally clarity and light», before going on to say «the sight of the beautiful implies peace».[76][77]

Chinese philosophy

Chinese philosophy has traditionally not made a separate discipline of the philosophy of beauty.[78] Confucius identified beauty with goodness, and considered a virtuous personality to be the greatest of beauties: In his philosophy, «a neighborhood with a ren man in it is a beautiful neighborhood.»[79] Confucius’s student Zeng Shen expressed a similar idea: «few men could see the beauty in some one whom they dislike.»[79] Mencius considered «complete truthfulness» to be beauty.[80] Zhu Xi said: «When one has strenuously implemented goodness until it is filled to completion and has accumulated truth, then the beauty will reside within it and will not depend on externals.»[80]

As an attribute to humans

The word «beauty» is often[how often?] used as a countable noun to describe a beautiful woman.[81][82]

The characterization of a person as «beautiful», whether on an individual basis or by community consensus, is often[how often?] based on some combination of inner beauty, which includes psychological factors such as personality, intelligence, grace, politeness, charisma, integrity, congruence and elegance, and outer beauty (i.e. physical attractiveness) which includes physical attributes which are valued on an aesthetic basis.[citation needed]

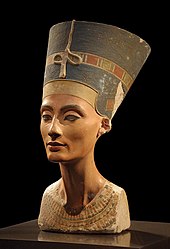

Standards of beauty have changed over time, based on changing cultural values. Historically, paintings show a wide range of different standards for beauty.[83][84] However, humans who are relatively young, with smooth skin, well-proportioned bodies, and regular features, have traditionally been considered the most beautiful throughout history.[citation needed]

A strong indicator of physical beauty is «averageness».[85][86][87][88][89] When images of human faces are averaged together to form a composite image, they become progressively closer to the «ideal» image and are perceived as more attractive. This was first noticed in 1883, when Francis Galton overlaid photographic composite images of the faces of vegetarians and criminals to see if there was a typical facial appearance for each. When doing this, he noticed that the composite images were more attractive compared to any of the individual images.[90] Researchers have replicated the result under more controlled conditions and found that the computer-generated, mathematical average of a series of faces is rated more favorably than individual faces.[91] It is argued that it is evolutionarily advantageous that sexual creatures are attracted to mates who possess predominantly common or average features, because it suggests the absence of genetic or acquired defects.[85][92][93][94]

Since the 1970’s there has been increasing evidence that a preference for beautiful faces emerges early in infancy, and is probably innate,[95][96][86][97][98]

and that the rules by which attractiveness is established are similar across different genders and cultures.[99][100]

A feature of beautiful women which has been explored by researchers is a waist–hip ratio of approximately 0.70. As of 2004, physiologists had shown that women with hourglass figures were more fertile than other women because of higher levels of certain female hormones, a fact that may subconsciously condition males choosing mates.[101][102] However, in 2008 other commentators have suggested that this preference may not be universal. For instance, in some non-Western cultures in which women have to do work such as finding food, men tend to have preferences for higher waist-hip ratios.[103][104][105]

Exposure to the thin ideal in mass media, such as fashion magazines, directly correlates with body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, and the development of eating disorders among female viewers.[106][107] Further, the widening gap between individual body sizes and societal ideals continues to breed anxiety among young girls as they grow, highlighting the dangerous nature of beauty standards in society.[108]

Western concept

Beauty standards are rooted in cultural norms crafted by societies and media over centuries. As of 2018, it has been argued that the predominance of white women featured in movies and advertising leads to a Eurocentric concept of beauty, which assigns inferiority to women of color.[109] Thus, societies and cultures across the globe struggle to diminish the longstanding internalized racism.[110]

Eurocentric standards for men include tallness, leanness, and muscularity, which have been idolized through American media, such as in Hollywood films and magazine covers.[111]

The prevailing Eurocentric concept of beauty has varying effects on different cultures. Primarily, adherence to this standard among African American women has bred a lack of positive reification of African beauty, and philosopher Cornel West elaborates that, «much of black self-hatred and self-contempt has to do with the refusal of many black Americans to love their own black bodies-especially their black noses, hips, lips, and hair.»[112] These insecurities can be traced back to global idealization of women with light skin, green or blue eyes, and long straight or wavy hair in magazines and media that starkly contrast with the natural features of African women.[113]

Much criticism has been directed at models of beauty which depend solely upon Western ideals of beauty as seen for example in the Barbie model franchise. Criticisms of Barbie are often centered around concerns that children consider Barbie a role model of beauty and will attempt to emulate her. One of the most common criticisms of Barbie is that she promotes an unrealistic idea of body image for a young woman, leading to a risk that girls who attempt to emulate her will become anorexic.[114]

As of 1998, these criticisms, the lack of diversity in such franchises as the Barbie model of beauty in Western culture, had led to a dialogue to create non-exclusive models of Western ideals in body type and beauty.[115] Mattel responded to these criticisms. Starting in 1980, it produced Hispanic dolls, and later came models from across the globe. For example, in 2007, it introduced «Cinco de Mayo Barbie» wearing a ruffled red, white, and green dress (echoing the Mexican flag). Hispanic magazine reports that:

[O]ne of the most dramatic developments in Barbie’s history came when she embraced multi-culturalism and was released in a wide variety of native costumes, hair colors and skin tones to more closely resemble the girls who idolized her. Among these were Cinco De Mayo Barbie, Spanish Barbie, Peruvian Barbie, Mexican Barbie and Puerto Rican Barbie. She also has had close Hispanic friends, such as Teresa.[116]

Black concept

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

In the 1960s the black is beautiful cultural movement sought to dispel the notion of a Eurocentric concept of beauty.[117]

Asian concept

An Indian woman in her traditional attire

In East Asian cultures, familial pressures and cultural norms shape beauty ideals; a 2017 experimental study concluded that expecting that men in Asian culture did not like women who look «fragile» was impacting Asian American women’s lifestyle, eating, and appearance choices.[118][119] In addition to the «male gaze», media portrayals of Asian women as petite and the portrayal of beautiful women in American media as fair complexioned and slim-figured have induced anxiety and depressive symptoms among Asian American women who do not fit either of these beauty ideals.[118][119] Further, the high status associated with fairer skin can be attributed to Asian societal history, as upper-class people hired workers to perform outdoor, manual labor, cultivating a visual divide over time between lighter complexioned, wealthier families and sun tanned, darker laborers.[119] This along with the Eurocentric beauty ideals embedded in Asian culture has made skin lightening creams, rhinoplasty, and blepharoplasty (an eyelid surgery meant to give Asians a more European, «double-eyelid» appearance) commonplace among Asian women, illuminating the insecurity that results from cultural beauty standards.[119]

In Japan, the concept of beauty in men is known as ‘bishōnen’. Bishōnen refers to males with distinctly feminine features, physical characteristics establishing the standard of beauty in Japan and typically exhibited in their pop culture idols. A multibillion-dollar industry of Japanese Aesthetic Salons exists for this reason.[citation needed]

Effects on society

Researchers have found that good-looking students get higher grades from their teachers than students with an ordinary appearance.[120] Some studies using mock criminal trials have shown that physically attractive «defendants» are less likely to be convicted—and if convicted are likely to receive lighter sentences—than less attractive ones (although the opposite effect was observed when the alleged crime was swindling, perhaps because jurors perceived the defendant’s attractiveness as facilitating the crime).[121] Studies among teens and young adults, such as those of psychiatrist and self-help author Eva Ritvo show that skin conditions have a profound effect on social behavior and opportunity.[122]

How much money a person earns may also be influenced by physical beauty. One study found that people low in physical attractiveness earn 5 to 10 percent less than ordinary-looking people, who in turn earn 3 to 8 percent less than those who are considered good-looking.[123] In the market for loans, the least attractive people are less likely to get approvals, although they are less likely to default. In the marriage market, women’s looks are at a premium, but men’s looks do not matter much.[124] The impact of physical attractiveness on earnings varies across races, with the largest beauty wage gap among black women and black men.[125]

Conversely, being very unattractive increases the individual’s propensity for criminal activity for a number of crimes ranging from burglary to theft to selling illicit drugs.[126]

Discrimination against others based on their appearance is known as lookism.[127]

See also

- Adornment

- Aesthetics

- Beauty pageant

- Body modification

- Feminine beauty ideal

- Glamour (presentation)

- Masculine beauty ideal

- Mathematical beauty

- Processing fluency theory of aesthetic pleasure

- Unattractiveness

- Cosmetics

References

- ^ a b Stegers, Rudolf (2008). Sacred Buildings: A Design Manual. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 60. ISBN 3764382767.

- ^ Gary Martin (2007). «Beauty is in the eye of the beholder». The Phrase Finder. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Sartwell, Crispin (2017). «Beauty». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e «Aesthetics». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «Beauty and Ugliness». Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b «Beauty in Aesthetics». Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Levinson, Jerrold (2003). «Philosophical Aesthetics: An Overview». The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–24. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Kriegel, Uriah (2019). «The Value of Consciousness». Analysis. 79 (3): 503–520. doi:10.1093/analys/anz045. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j De Clercq, Rafael (2013). «Beauty». The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics. Routledge. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zangwill, Nick (2003). «Beauty». In Levinson, Jerrold (ed.). Oxford Handbook to Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199279456.003.0018. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i De Clercq, Rafael (2019). «Aesthetic Pleasure Explained». Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 77 (2): 121–132. doi:10.1111/jaac.12636.

- ^ a b c d Gorodeisky, Keren (2019). «On Liking Aesthetic Value». Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 102 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1111/phpr.12641. S2CID 204522523.

- ^ Honderich, Ted (2005). «Aesthetic judgment». The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Scruton, Roger (2011). Beauty: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 5. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Rogerson, Kenneth F. (1982). «The Meaning of Universal Validity in Kant’s Aesthetics». The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 40 (3): 304. doi:10.2307/429687. JSTOR 429687. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Uzgalis, William (2020). «John Locke». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Berg, Servaas Van der (2020). «Aesthetic Hedonism and Its Critics». Philosophy Compass. 15 (1): e12645. doi:10.1111/phc3.12645. S2CID 213973255. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Matthen, Mohan; Weinstein, Zachary. «Aesthetic Hedonism». Oxford Bibliographies. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Honderich, Ted (2005). «Beauty». The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Spicher, Michael R. «Aesthetic Taste». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Craig, Edward (1996). «Beauty». Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Hansson, Sven Ove (2005). «Aesthetic Functionalism». Contemporary Aesthetics. 3. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Konstan, David (2014). Beauty — The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0-19-992726-5.

- ^ Matthew 23:27, Acts 3:10, Flavius Josephus, 12.65

- ^ a b Euripides, Alcestis 515.

- ^ a b G Parsons (2008). Aesthetics and Nature. A&C Black. p. 7. ISBN 978-0826496768. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d J. Harrell; C. Barrett; D. Petsch, eds. (2006). History of Aesthetics. A&C Black. p. 102. ISBN 0826488552. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ P.T. Struck — The Trojan War Archived December 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Classics Department of University of Penn [Retrieved 2015-05-12]( < 1250> )

- ^ R Highfield — Scientists calculate the exact date of the Trojan horse using eclipse in Homer Archived December 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Telegraph Media Group Limited 24 Jun 2008 [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^ Bronze Age first source C Freeman — Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean — p.116 Archived February 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, verified at A. F. Harding — European Societies in the Bronze Age — p.1 Archived February 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^ Sources for War with Troy Archived December 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Cambridge University Classics Department [Retrieved 2015-05-12]( < 750, 850 > )

- ^ the most beautiful — C.Braider — The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: Volume 3 Archived February 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, The Renaissance: Zeuxis portrait (p.174) ISBN 0521300088 — Ed. G.A. Kennedy, G.P. Norton & The British Museum — Helen runs off with Paris Archived October 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^ W.W. Clohesy — The Strength of the Invisible: Reflections on Heraclitus (p.177) Archived August 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Auslegung Volume XIII ISSN 0733-4311 [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^ a b c Fistioc, M.C. (December 5, 2002). The Beautiful Shape of the Good: Platonic and Pythagorean Themes in Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment. Review by S Naragon, Manchester College. Routledge, 2002 (University of Notre Dame philosophy reviews). Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c J.L. Wright. Review of The Beautiful Shape of the Good:Platonic and Pythagorean Themes in Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment by M.C.Fistioc Volume 4 Issue 2 Medical Research Ethics. Pacific University Library. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2015.(ed. 4th paragraph — beauty and the divine)

- ^ Seife, Charles (2000). Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea. Penguin. p. 32. ISBN 0-14-029647-6.

- ^ a b Sartwell, C. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Beauty. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition). Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ a b L Cheney (2007). Giorgio Vasari’s Teachers: Sacred & Profane Art. Peter Lang. p. 118. ISBN 978-0820488134. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ N Wilson — Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece (p.20) Routledge, 31 Oct 2013 ISBN 113678800X [Retrieved 2015-05-12]

- ^ K Urstad. Loving Socrates:The Individual and the Ladder of Love in Plato’s Symposium (PDF). Res Cogitans 2010 no.7, vol. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ a b W. K. C. Guthrie; J. Warren (2012). The Greek Philosophers from Thales to Aristotle (p.112). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415522281. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ a b A Preus (1996). Notes on Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle (parts 198 and 210). Global Academic Publishing. ISBN 1883058090. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ S Scolnicov (2003). Plato’s Parmenides. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 0520925114. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ Phaedrus

- ^ D. Konstan (2014). Beauty — The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. published by Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199927265. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ F. McGhee — review of text written by David Konstan Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine published by the Oxonian Review March 31, 2015 [Retrieved 2015-11-24](references not sources: Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2014.06.08 (Donald Sells) Archived November 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine + DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199605507.001.0001 Archived July 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Nicomachean Ethics

- ^ M Garani (2007). Empedocles Redivivus: Poetry and Analogy in Lucretius. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135859831. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (1988). The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press. p. 98. ISBN 0674006755.

- ^ McNamara, Denis Robert (2009). Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy. Hillenbrand Books. pp. 24–28. ISBN 1595250271.

- ^ Duiker, William J., and Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2019). World History. United States: Cengage Learning. p. 351. ISBN 1337401048

- ^ «NPNF1-02. St. Augustine’s City of God and Christian Doctrine — Christian Classics Ethereal Library». CCEL. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Ames-Lewis, Francis (2000), The Intellectual Life of the Early Renaissance Artist, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, p. 194, ISBN 0-300-09295-4

- ^ Francis Hutcheson (1726). An Inquiry Into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue: In Two Treatises. J. Darby. ISBN 9780598982698. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Kennick, William Elmer (1979). Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 421. ISBN 0312053916.

- ^ Kennick, William Elmer (1979). Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. pp. 482–483. ISBN 0312053916.

- ^ a b Kennick, William Elmer (1979). Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 517. ISBN 0312053916.

- ^ Doran, Robert (2017). The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 1107499151.

- ^ Monk, Samuel Holt (1960). The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in XVIII-century England. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 6–9, 141. OCLC 943884.

- ^ Hal Foster (1998). The Anti-aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-462-9.

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1967). The Will To Power. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-70437-1.

- ^ Guy Sircello, A New Theory of Beauty. Princeton Essays on the Arts, 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- ^ Love and Beauty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- ^ Kennick, William Elmer (1979). Art and Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics; 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. pp. 535–537. ISBN 0312053916.

- ^ Elaine Scarry (November 4, 2001). On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08959-0.

- ^ Reber, Rolf; Schwarz, Norbert; Winkielman, Piotr (November 2004). «Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience?». Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (4): 364–382. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. hdl:1956/594. PMID 15582859. S2CID 1868463.

- ^ Armstrong, Thomas; Detweiler-Bedell, Brian (December 2008). «Beauty as an Emotion: The Exhilarating Prospect of Mastering a Challenging World». Review of General Psychology. 12 (4): 305–329. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.406.1825. doi:10.1037/a0012558. S2CID 8375375.

- ^ Vartanian, Oshin; Navarrete, Gorka; Chatterjee, Anjan; Fich, Lars Brorson; Leder, Helmut; Modroño, Cristián; Nadal, Marcos; Rostrup, Nicolai; Skov, Martin (June 18, 2013). «Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architecture». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (Suppl 2): 10446–10453. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301227110. PMC 3690611. PMID 23754408.

- ^ Marin, Manuela M.; Lampatz, Allegra; Wandl, Michaela; Leder, Helmut (November 4, 2016). «Berlyne Revisited: Evidence for the Multifaceted Nature of Hedonic Tone in the Appreciation of Paintings and Music». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 10: 536. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00536. PMC 5095118. PMID 27867350.

- ^ Brielmann, Aenne A.; Pelli, Denis G. (May 2017). «Beauty Requires Thought». Current Biology. 27 (10): 1506–1513.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.018. PMC 6778408. PMID 28502660.

- ^ Kawabata, Hideaki; Zeki, Semir (April 2004). «Neural Correlates of Beauty». Journal of Neurophysiology. 91 (4): 1699–1705. doi:10.1152/jn.00696.2003. PMID 15010496.

- ^ Ishizu, Tomohiro; Zeki, Semir (July 6, 2011). «Toward A Brain-Based Theory of Beauty». PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21852. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…621852I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021852. PMC 3130765. PMID 21755004.

- ^ Conway, Bevil R.; Rehding, Alexander (March 19, 2013). «Neuroaesthetics and the Trouble with Beauty». PLOS Biology. 11 (3): e1001504. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001504. PMC 3601993. PMID 23526878.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2004). On Beauty: A historyof a western idea. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 978-0436205170.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2007). On Ugliness. London: Harvill Secker. ISBN 9781846551222.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Eco, Umberto (1980). The Name of the Rose. London: Vintage. p. 65. ISBN 9780099466031.

- ^ Fasolini, Diego (2006). «The Intrusion of Laughter into the Abbey of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose: The Christian paradox of Joy Mingling with Sorrow». Romance Notes. 46 (2): 119–129. JSTOR 43801801.

- ^ The Chinese Text: Studies in Comparative Literature (1986). Cocos (Keeling) Islands: Chinese University Press. p. 119. ISBN 962201318X.

- ^ a b Chang, Chi-yun (2013). Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation (2012 Edition). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 213. ISBN 9814439894

- ^ a b Tang, Yijie (2015). Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity and Chinese Culture. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 242. ISBN 3662455331

- ^ «Beauty | Definition of Beauty by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com». Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ «BEAUTY (noun) American English definition and synonyms | Macmillan Dictionary». Macmillan Dictionary. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Artists’ Types of Beauty Archived February 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine», The Strand Magazine. United Kingdom, G. Newnes, 1904. pp. 291–298.

- ^ Chō, Kyō (2012). The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty. Translated by Selden, Kyoko Iriye. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 100–102. ISBN 978-1442218956..

- ^ a b Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A. (1990). «Attractive Faces Are Only Average». Psychological Science. 1 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00079.x. S2CID 18557871.

- ^ a b Strauss, Mark S. (1979). «Abstraction of prototypical information by adults and 10-month-old infants». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 5 (6): 618–632. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.5.6.618. PMID 528918.

- ^ Rhodes, Gillian; Tremewan, Tanya (1996). «Averageness, Exaggeration, and Facial Attractiveness». Psychological Science. SAGE Publications. 7 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00338.x. S2CID 145245882.

- ^ Valentine, Tim; Darling, Stephen; Donnelly, Mary (2004). «Why are average faces attractive? The effect of view and averageness on the attractiveness of female faces». Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 11 (3): 482–487. doi:10.3758/bf03196599. ISSN 1069-9384. PMID 15376799. S2CID 25389002.

- ^ «The Beauty of Averageness». Langlois Social Development Lab. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Galton, Francis (1879). «Composite Portraits, Made by Combining Those of Many Different Persons Into a Single Resultant Figure». The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. JSTOR. 8: 132–144. doi:10.2307/2841021. ISSN 0959-5295. JSTOR 2841021. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A.; Musselman, Lisa (1994). «What Is Average and What Is Not Average About Attractive Faces?». Psychological Science. SAGE Publications. 5 (4): 214–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00503.x. ISSN 0956-7976. S2CID 145147905.

- ^ Koeslag, Johan H. (1990). «Koinophilia groups sexual creatures into species, promotes stasis, and stabilizes social behaviour». Journal of Theoretical Biology. Elsevier BV. 144 (1): 15–35. Bibcode:1990JThBi.144…15K. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80297-8. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 2200930.

- ^ Symons, D. (1979) The Evolution of Human Sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (May 7, 2008). «Why beauty is an advert for good genes». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Slater, Alan; Von der Schulenburg, Charlotte; Brown, Elizabeth; Badenoch, Marion; Butterworth, George; Parsons, Sonia; Samuels, Curtis (1998). «Newborn infants prefer attractive faces». Infant Behavior and Development. Elsevier BV. 21 (2): 345–354. doi:10.1016/s0163-6383(98)90011-x. ISSN 0163-6383.

- ^ Kramer, Steve; Zebrowitz, Leslie; Giovanni, Jean Paul San; Sherak, Barbara (February 21, 2019). «Infants’ Preferences for Attractiveness and Babyfaceness». Studies in Perception and Action III. Routledge. pp. 389–392. doi:10.4324/9781315789361-103. ISBN 978-1-315-78936-1. S2CID 197734413.

- ^ Rubenstein, Adam J.; Kalakanis, Lisa; Langlois, Judith H. (1999). «Infant preferences for attractive faces: A cognitive explanation». Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 35 (3): 848–855. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.848. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 10380874.

- ^ Langlois, Judith H.; Ritter, Jean M.; Roggman, Lori A.; Vaughn, Lesley S. (1991). «Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces». Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 27 (1): 79–84. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.79. ISSN 1939-0599.

- ^ Apicella, Coren L; Little, Anthony C; Marlowe, Frank W (2007). «Facial Averageness and Attractiveness in an Isolated Population of Hunter-Gatherers». Perception. SAGE Publications. 36 (12): 1813–1820. doi:10.1068/p5601. ISSN 0301-0066. PMID 18283931. S2CID 37353815.

- ^ Rhodes, Gillian (2006). «The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty». Annual Review of Psychology. Annual Reviews. 57 (1): 199–226. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 16318594.

- ^ «Hourglass figure fertility link». BBC News. May 4, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Shaoni (May 5, 2004). «Barbie-shaped women more fertile». New Scientist. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ «Best Female Figure Not an Hourglass». Live Science. December 3, 2008. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Locke, Susannah (June 22, 2014). «Did evolution really make men prefer women with hourglass figures?». Vox. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Begley, Sharon. «Hourglass Figures: We Take It All Back». Sharon Begley. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ «Media & Eating Disorders». National Eating Disorders Association. October 5, 2017. Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ «Model’s link to teenage anorexia». BBC News. May 30, 2000. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ Jade, Deanne. «National Centre for Eating Disorders — The Media & Eating Disorders». National Centre for Eating Disorders. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Harper, Kathryn; Choma, Becky L. (October 5, 2018). «Internalised White Ideal, Skin Tone Surveillance, and Hair Surveillance Predict Skin and Hair Dissatisfaction and Skin Bleaching among African American and Indian Women». Sex Roles. 80 (11–12): 735–744. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0966-9. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 150156045.

- ^ Weedon, Chris (December 6, 2007). «Key Issues in Postcolonial Feminism: A Western Perspective». Gender Forum Electronic Journal.

- ^ «The New (And Impossible) Standards of Male Beauty». Paging Dr. NerdLove. January 26, 2015. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ West, Cornel (1994). Race Matters. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-74986-8.[page needed]

- ^ Patton, Tracey Owens (July 2006). «Hey Girl, Am I More than My Hair?: African American Women and Their Struggles with Beauty, Body Image, and Hair». NWSA Journal. 18 (2): 24–51. JSTOR 4317206. Project MUSE 199496 ProQuest 233235409.

- ^ Dittmar, Helga; Halliwell, Emma; Ive, Suzanne (March 2006). «Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls». Developmental Psychology. 42 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. PMID 16569167.

- ^ Marco Tosa (1998). Barbie: Four Decades of Fashion, Fantasy, and Fun. H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-4008-6.[page needed]

- ^ «A Barbie for Everyone». Hispanic. 22 (1). February–March 2009.

- ^ DoCarmo, Stephen. «Notes on the Black Cultural Movement». Bucks County Community College. Archived from the original on April 8, 2005. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- ^ a b Wong, Stephanie N.; Keum, Brian TaeHyuk; Caffarel, Daniel; Srinivasan, Ranjana; Morshedian, Negar; Capodilupo, Christina M.; Brewster, Melanie E. (December 2017). «Exploring the conceptualization of body image for Asian American women». Asian American Journal of Psychology. 8 (4): 296–307. doi:10.1037/aap0000077. S2CID 151560804.

- ^ a b c d Le, C.N. (June 4, 2014). «The Homogenization of Asian Beauty». The Society Pages. Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.[self-published source?]

- ^ Begley, Sharon (July 14, 2009). «The Link Between Beauty and Grades». Newsweek. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Amina A Memon; Aldert Vrij; Ray Bull (October 31, 2003). Psychology and Law: Truthfulness, Accuracy and Credibility. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-470-86835-5.

- ^ «Image survey reveals «perception is reality» when it comes to teenagers» (Press release). multivu.prnewswire.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ Lorenz, K. (2005). «Do pretty people earn more?». CNN News. Time Warner. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Daniel Hamermesh; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014). «Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript». Freakonomics. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Monk, Ellis P.; Esposito, Michael H.; Lee, Hedwig (July 1, 2021). «Beholding Inequality: Race, Gender, and Returns to Physical Attractiveness in the United States». American Journal of Sociology. 127 (1): 194–241. doi:10.1086/715141. S2CID 235473652.

- ^ Erdal Tekin; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014). «Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript». Freakonomics. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Leo Gough (June 29, 2011). C. Northcote Parkinson’s Parkinson’s Law: A modern-day interpretation of a management classic. Infinite Ideas. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-908189-71-4.

Further reading

- Richard O. Prum (2018). The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World — and Us. Anchor. ISBN 978-0345804570.

- Liebelt, C. (2022), Beauty: What Makes Us Dream, What Haunts Us. Feminist Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12076

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beauty.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Beauty.

Look up beauty or pretty in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Sartwell, Crispin. «Beauty». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Beauty at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time programme on Beauty (requires RealAudio)

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Theories of Beauty to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- beautycheck.de/english Regensburg University – Characteristics of beautiful faces

- Eli Siegel’s «Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?»

- Art and love in Renaissance Italy , Issued in connection with an exhibition held Nov. 11, 2008-Feb. 16, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Belle: Picturing Beautiful Women; pages 246–254).

- Plato — Symposium in S. Marc Cohen, Patricia Curd, C. D. C. Reeve (ed.)

Updated:4/7/2021

Ever wondered “what is beauty essay”? We’ve got some hints right here for you!

The concept of beauty is studied in sociology, philosophy, psychology, culture, and aesthetics.

It is regarded as a property of an object, idea, animal, place, or a person, and it often interpreted as balance and harmony with nature.

Beauty as a concept has been argued throughout the entire history of civilization, but even today, there is neither single definition accepted by many people nor shared vision.

People think that something or someone is beautiful when it gives them feelings of attraction, placidity, pleasure, and satisfaction, which may lead to emotional well-being.

If speaking about a beautiful person, he or she can be characterized by the combination of inner beauty (personality, elegance, integrity, grace, intelligence, etc.) and outer beauty or physical attractiveness.

The interpretation of beauty and its standards are highly subjective. They are based on changing cultural values.

Besides, people have unique personalities with different tastes and standards, so everyone has a different vision of what is beautiful and what is ugly.

We all know the saying that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder.

That’s why writing a beauty definition essay is not easy. In this article, we will explore this type of essay from different angles and provide you with an easy how-to writing guide.

Besides, you will find 20 interesting beauty essay topics and a short essay sample which tells about the beauty of nature.

What is beauty essay?

Let’s talk about the specifics of what is beauty philosophy essay.

As we have already mentioned, there is no single definition of this concept because its interpretation is based on constantly changing cultural values as well as the unique vision of every person.

…So if you have not been assigned a highly specific topic, you can talk about the subjective nature of this concept in the “beauty is in the eye of the beholder essay.”

Communicate your own ideas in “what does beauty mean to you essay,” tell about psychological aspects in the “inner beauty essay” or speak about aesthetic criteria of physical attractiveness in the “beauty is only skin deep essay.”

You can choose any approach you like because there are no incorrect ways to speak about this complex subjective concept.

How to write a beauty definition essay?

When you are writing at a college level, it’s crucial to approach your paper in the right way.

Keep reading to learn how to plan, structure, and write a perfect essay on this challenging topic.

You should start with a planning stage which will make the entire writing process faster and easier. There are different planning strategies, but it’s very important not to skip the essential stages.

- Analyzing the topic – break up the title to understand what is exactly required and how complex your response should be. Create a mind map, a diagram, or a list of ideas on the paper topic.

- Gathering resources – do research to find relevant material (journal and newspaper articles, books, websites). Create a list of specific keywords and use them for the online search. After completing the research stage, create another mind map and carefully write down quotes and other information which can help you answer the essay question.

- Outlining the argument – group the most significant points into 3 themes and formulate a strong specific thesis statement for your essay. Make a detailed paper plan, placing your ideas in a clear, logical order. Develop a structure, forming clear sections in the main body of your paper.

Start working on your paper by expanding your outline.

If you know exactly what points you are going to argue, you can write your introduction and conclusion first. But if you are unsure about the logical flow of the argument, it would be better to build an argument first and leave the introductory and concluding sections until last.

Stick to your plan but be ready to deviate from it as your work develops. Make sure that all adjustments are relevant before including them in the paper.

Keep in mind that the essay structure should be coherent.

In the introduction, you should move from general to specific.

- Start your essay with an attention grabber: a provocative question, a relevant quote, a story.

- Then introduce the topic and give some background information to provide a context for your subject.

- State the thesis statement and briefly outline all the main ideas of the paper.

- Your thesis should consist of the 2 parts which introduce the topic and state the point of your paper.

Body paragraphs act like constructing a block of your argument where your task is to persuade your readers to accept your point of view.

- You should stick to the points and provide your own opinion on the topic.

- The number of paragraphs depends on the number of key ideas.

- You need to develop a discussion to answer the research question and support the thesis.

- Begin each body paragraph with a topic sentence that communicates the main idea of the paragraph.

- Add supporting sentences to develop the main idea and provide appropriate examples to support and illustrate the point.

- Comment on the examples and analyze their significance.

- Use paraphrases and quotes with introductory phrases. They should be relevant to the point you are making.

- Finish every body paragraph with a concluding sentence that provides a transition to the next paragraph.

- Use transition words and phrases to help your audience follow your ideas.

In conclusion, which is the final part of your essay, you need to move from the specific to general.

- You may restate your thesis, give a brief summary of the key points, and finish with a broad statement about the future direction for research and possible implications.

- Don’t include any new information here.

When you have written the first draft, put it aside for a couple of days. Reread the draft and edit it by improving the content and logical flow, eliminating wordiness, and adding new examples if necessary to support your main points. Edit the draft several times until you are completely satisfied with it.

Finally, proofread the draft, fix spelling and grammar mistakes, and check all references and citations to avoid plagiarism. Review your instructions and make sure that your essay is formatted correctly.

Winning beauty essay topics

- Are beauty contests beneficial for young girls?

- Is it true that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder?

- Inner beauty vs physical beauty.

- History of beauty pageants.

- How can you explain the beauty of nature?

- The beauty of nature as a theme of art.

- The beauty of nature and romanticism.

- Concept of beauty in philosophy.

- Compare concepts of beauty in different cultures.

- Concept of beauty and fashion history.

- What is the aesthetic value of an object?

- How can beauty change and save the world?

- What is the ideal beauty?

- Explain the relationship between art and beauty.

- Can science be beautiful?

- What makes a person beautiful?

- The cult of beauty in ancient Greece.

- Rejection of beauty in postmodernism.

- Is beauty a good gift of God?

- Umberto Eco on the western idea of beauty.

The beauty of nature essay sample

The world around us is so beautiful that sometimes we can hardly believe it exists. The beauty of nature has always attracted people and inspired them to create amazing works of art and literature. It has a great impact on our senses, and we start feeling awe, wonder or amazement.

The sight of flowers, rainbows, and butterflies fills human hearts with joy and a short walk amidst nature calms their minds.

…Why is nature so beautiful?

Speaking about people, we can classify them between beautiful and ugly. But we can’t say this about nature. You are unlikely to find an example in the natural world which we could call ugly. Everything is perfect – the shapes, the colors, the composition. It’s just a magic that nature never makes aesthetic mistakes and reveals its beauty in all places and at all times.

Maybe we are psychologically programmed to consider natural things to be beautiful. We think that all aspects of nature are beautiful because they are alive. We see development and growth in all living things, and we consider them beautiful, comparing that movement with the static state of man-made things.

Besides, maybe we experience the world around us as beautiful because we view it as an object of intellect and admire its rational structure. Nature has intrinsic value based on its intelligible structure. It’s an integral part of our lives, and it needs to be appreciated.

On balance…

We have discussed specifics of the “what is true beauty essay” and the effective writing strategies you should use to approach this type of academic paper. Now it’s time to practice writing.

You should write whenever you have a chance because practice makes perfect. If you feel you need more information about writing essays, check other articles on our website with useful tips and tricks.

Share this story:

Here at the Blair’s Beauty Bar, we are dedicated to making you look and feel beautiful. The word “beauty” is a word we hear all the time. But do we really know what it means? I’m not so sure. I think the word “beauty” is subjective and means something different to everyone.

Confidence

Beauty can be about confidence. It can relate to feeling good. It can be the simple fact of someone knowing that they look amazing. It is an all encompassing term that is both fluid and dynamic. Beauty is not limited to what is seen in magazines or on the internet. Beauty is something that everyone has when they are born and something that they have throughout their entire life. Someone’s idea of beauty does not have to stay the same for their whole life but instead it can change yearly, monthly, daily, or hourly. Beauty is truly something that everyone has but will not always admit they have it.

Is it because they are nervous their definition does not fit with others’ definitions? It shouldn’t be about nervousness – it’s about confidence.