Every teacher wonders how to teach a word to students, so that it stays with them and they can actually use it in the context in an appropriate form. Have your students ever struggled with knowing what part of the speech the word is (knowing nothing about terminologies and word relations) and thus using it in the wrong way? What if we start to teach learners of foriegn languages the basic relations between words instead of torturing them to memorize just the usage of the word in specific contexts?

Let’s firstly try to recall what semantic relations between words are. Semantic relations are the associations that exist between the meanings of words (semantic relationships at word level), between the meanings of phrases, or between the meanings of sentences (semantic relationships at phrase or sentence level). Let’s look at each of them separately.

Word Level

At word level we differentiate between semantic relations:

- Synonyms — words that have the same (or nearly the same) meaning and belong to the same part of speech, but are spelled differently. E.g. big-large, small-tiny, to begin — to start, etc. Of course, here we need to mention that no 2 words can have the exact same meaning. There are differences in shades of meaning, exaggerated, diminutive nature, etc.

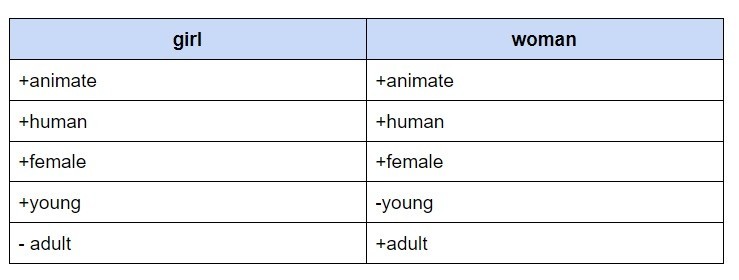

- Antonyms — semantic relationship that exists between two (or more) words that have opposite meanings. These words belong to the same grammatical category (both are nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). They share almost all their semantic features except one. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1998) E.g.

- Homonyms — the relationship that exists between two (or more) words which belong to the same grammatical category, have the same spelling, may or may not have the same pronunciation, but have different meanings and origins. E.g. to lie (= to rest) and to lie (= not to tell the truth); When used in a context, they can be misunderstood especially if the person knows only one meaning of the word.

Other semantic relations include hyponymy, polysemy and metonymy which you might want to look into when teaching/learning English as a foreign language.

At Phrase and Sentence Level

Here we are talking about paraphrases, collocations, ambiguity, etc.

- Paraphrase — the expression of the meaning of a word, phrase or sentence using other words, phrases or sentences which have (almost) the same meaning. Here we need to differentiate between lexical and structural paraphrase. E.g.

Lexical — I am tired = I am exhausted.

Structural — He gave the book to me = He gave me the book.

- Ambiguity — functionality of having two or more distinct meanings or interpretations. You can read more about its types here.

- Collocations — combinations of two or more words that often occur together in speech and writing. Among the possible combinations are verbs + nouns, adjectives + nouns, adverbs + adjectives, etc. Idiomatic phrases can also sometimes be considered as collocations. E.g. ‘bear with me’, ‘round and about’, ‘salt and pepper’, etc.

So, what does it mean to know a word?

Knowing a word means knowing all of its semantic relations and usages.

Why is it useful?

It helps to understand the flow of the language, its possibilities, occurrences, etc.better.

Should it be taught to EFL learners?

Maybe not in that many details and terminology, but definitely yes if you want your learners to study the language in depth, not just superficially.

How should it be taught?

Not as a separate phenomenon, but together with introducing a new word/phrase, so that students have a chance to create associations and base their understanding on real examples. You can give semantic relations and usages, ask students to look up in the dictionary, brainstorm ideas in pairs and so on.

Let us know what you do to help your students learn the semantic relations between the words and whether it helps.

There’s relatively little on the Notebook about teaching vocabulary, and in the next few weeks I’m going to try and remedy that. In future articles we’ll talk about techniques you can use in the classroom to introduce, practice and recycle new lexis, but before looking at that, we need to know exactly what it is we want to teach. So what does it mean to know a word? Here are a few suggestions.

«Knowing» a word means :

a) understanding its basic meaning (denotation) and also any evaluative or associated meaning it has (connotation). For example cottage and hovel are both types of small houses. But cottage suggests cosiness, a pretty house with a garden, probably in the countryside, whereas hovel suggests a run-down construction, dirt and squalid poverty. Many words have similar positive or negative connotations — consider slim and scrawny — and, in certain cases these connotations may lead to their being considered «politically incorrect» — for example handicapped.

b) understanding the grammatical form of the word and its syntactic use (colligation). For example, interesting, main and alone are all adjectives. However, while interesting (like most adjectives) can be either attributive or predicative — eg:

- It was an interesting discussion (attributive)

- The discussion was interesting (predicative)

main can only be used attributively — That’s the main point rather than *That point is main, while alone can only be used predicatively — The woman was alone but not *We saw an alone woman.

c) understanding that words may have more than one meaning — eg boom may mean a loud sound, an increase in business, a pole to which a sail (on a boat) or a microphone or camera (in a TV or film studio) may be attached, or a heavy chain stretched across a river to stop things passing. Changes in meaning may also involve changes in colligation. To go back to the example of adjectives above, take the adjective old. With the meaning of aged it can be both attributive or predicative — We live in an old house / Our house is old. But with the meaning known for a long time it is only attributive — an old friend, an old saying. Using it predicatively —My friend is old — changes the meaning back to aged.

d) understanding that in changing meaning the word may also change form — eg fast can be an adjective or adverb meaning quick(ly) or a verb or noun related to a period of voluntarily going without food.

e) understanding what variety of English the word belongs to :

- is it informal, neutral or formal? Eg nosh — food — comestibles

- does it belong to a specific regional variety of the language (eg bairn in Scottish English), or does it have different meanings in different varieties of English? For example, biscuit in US and UK English.

- is it considered vulgar or taboo? Eg bollocks, asshole, shit

- is it an «everyday» term or a technical term and if the latter in what field? Eg feelers vs antennae in biology

- is it used in current English or is it archaic? Eg betwixt, damsel, looking glass

f) knowing how to decode the word when it is heard or read, and how to pronounce and spell it when it is used. The lack of a one-to-one correspondence between spelling and pronunciation in English makes this feature more important than in many other languages, the classic example being the variation of pronunciation of -ough in words like though, through, thought, tough, and cough. Pronunciation also involves knowledge of stress patterns and how changes in the form of the word may affect this : consider ˈphotograph, phoˈtographer, photoˈgraphic In addition, both spelling and pronunciation may be affected by the differences in variety of English mentioned in (g) above. For example — the pronunciation of new as /nju:/ in British English but /nu:/ in American English; and the change in spelling from -our in British English (behaviour, colour) to -or in US English (behavior, color)

g) understanding how affixes can change the form and meaning of the word — eg help, helpful, unhelpful, helpfully, helpless, helplessness etc

h) knowing how it relates to other words in lexical sets. This includes relationships such as:

- hyponymy — for example a car is member of the category vehicle and thus asociated with other members of that category : bus, coach, lorry, motorbike etc.

- meronymy — for example an arm is part of a body and as such is associated with other parts such as leg, hand, head, ear etc.

- synonymy — words with the same meaning — eg flower, bloom, blossom

- antonymy — opposites ; big-small, dead-alive, open-close etc.

i) knowing its place in one or more specific lexical fields, and the other words likely to be found in that field. Eg dig is part of the lexical field gardening and as such is connected to words such as plant, fertiliser, roses, roots, secateurs, mow etc. But it is also part of the lexical field archaeology, where it will have a different set of associations.

j) knowing its use in fixed and semi-fixed lexical chunks, such as multiword verbs (eg run in run out of) collocations (the use of heavy in heavy rain), idioms (to get cold feet), binomials (trial and error), and other types of figurative language which I discussed in detail here.

All this begs one important question however : are we talking about receptive understanding or productive use? Obviously, some features of the word — eg its basic denotation and possible connotations — are important for both, while colligation is perhaps only necessary for productive use. This will affect how we decide to teach the words, but so may other factors : what level are the learners? How can we teach lexis in such a way as to promote retention? Which other of the factors listed above should we take into consideration and how do we do it? These questions will be discussed in another article — coming soon!

Приглашаем коллег завести свой персональный блог!

Расскажите о своей профессиональной деятельности.

- Все блоги

- Тэги

- Поиск

What does it mean to know a word?

Firstly, to know the form of the word, that is, the spelling, the pronunciation, the morphological structure.

Secondly, the meaning of the word (and, more often, different meanings).

Thirdly, to know how the word is used, in which type of context, what grammatical features it has.

Now, I want to suggest different types of activities that can be used to practice all the features mentioned above.

Form:

- Jumbled words, that is, when students have to put the letters in a word in the correct order.

- Spelling dictations.

- Finding spelling mistakes.

- Filling in the letter gaps in a word.

- Wordsearches and crossword puzzles.

- Analysis of the morphological structure of a word (prefixes, suffixes, roots).

- Recitation of poems.

- Reading aloud.

- Filling in the gaps with the appropriate form of the word.

Meaning:

- Matching words with images or definitions.

- Word maps.

- Inferring meaning from the context.

- Prediction.

- Jumbled sentences (students put the words in the right order).

- Matching/replacing the word with synonyms/antonyms.

- Translation.

Use:

- Filling in the gaps with appropriate words.

- Matching collocations.

- Finding collocations in a text.

- Choosing the word that fits into a sentence from several variants given.

- Making topical/functional word lists.

References:

Harmer J. The Practice of ELT, Longman, 2007

http://www.headsupenglish.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=88&Itemid=72

Теги: Нет тегов

By Christina Cavage

What It Really Means to Know a Word

As ELT educators we often build our lessons around reading, writing, listening, speaking and grammar. We introduce new vocabulary that students need to be able to accomplish the reading or listening task. This often happens by providing a definition, and maybe a few ‘drill and kill’ type of exercises—matching the word and definition, multiple choice, or fill-ins. But, does this really lead to vocabulary acquisition? In a word, no. Vocabulary, specifically academic vocabulary is the often-forgotten skill in language learning. To effectively foster vocabulary learning, we need to consider what it really means to know a word.

According to Paul Nation, explicit vocabulary teaching, is necessary, but not always effective for expanding a student’s knowledge of a word because knowing a word goes far beyond identifying the definition of a word. While form, meaning, and usage are the key elements for understanding a word, Nation breaks these down even further. When you know a word, you know:

Form:

- How it is pronounced (spoken form)

- How it is spelled (written form)

- Which word parts are in the word (prefix, base, suffix)

Meaning:

- Meanings/definitions

- Concepts associated with the word

- Synonyms or other words associations

Usage:

- How the word is used in a sentence (grammatical function in a sentence)

- What collocations the word has

- When and where the word is used (register and frequency)

This list may seem overwhelming, especially if you need to prepare students for university entrance, where their acquisition of the AWL (Academic Word List) is critical for their success. This list of 570-word families contains the words that most frequently appear in academic texts, across all disciplines. So, adding that layer to what it means to really know a word, goes beyond overwhelming! So, how can we adequately prepare students to not only know, but really know English vocabulary while engaging them in the learning process at the same time?

Well, first we have to consider the tools we use. As we have seen, true academic vocabulary acquisition goes beyond what lies in many textbooks; thus, we have to look for additional tools. Within the Pearson English Content Library Powered by Nearpod, lies The Modular Academic Word List Course. The vocabulary lessons within the Modular AWL are built around Paul Nation’s work in what it means to really know a word. Students engage in activities where they can practice spoken form, written form, meanings, grammatical functions, collocations, and more. These flexible lessons allow you the teacher to deliver powerful lessons in class and out-of-class.

The AWL Library is divided into 10 sublists, the first containing the most frequent terms and the last (10) being the least frequent. Each lesson begins with an overview of the vocabulary term, highlighting meaning, part of speech, syllable division, and collocations. From there, students are able to see the word in context. Then, students are engaged with a formative assessment, assessing their understanding of the word in context. They listen and choose the word stress, engage with collocations, create their own sentence with the vocabulary item (in speaking and writing), and are given a final summative assessment of the vocabulary item, which is conducted with a gamification tool.

Each microlesson provides a dynamic, interactive learning experience, that is completely customizable. In other words, you, the teacher, can add, delete and modify any lesson to address the needs of your students. Additionally, as students move through the lesson, you receive real-time data on your students’ strengths and struggles, as well as their level of engagement. You can see who is engaging in the lesson, and who may not be engaging.

Teaching vocabulary needs to go beyond word, definition, and part of speech if we want to foster true acquisition. We can do this by providing students opportunities to engage with academic vocabulary that are built upon sound research in vocabulary.

Christina Cavage is the Curriculum and Assessment Manager at University of Central Florida. She has trained numerous teachers all over the world in using digital technologies to enhance and extend learning. She has authored over a dozen ELT textbooks, including University Success, Oral Communication, Transition Level, Advanced Level, Intermediate Level and A2. Recently, Ms. Cavage completed grammar and academic vocabulary curriculum for the new Pearson English Content Library Powered by Nearpod, which is now available. Learn more here.

time to complete: 15-20 minutes

Let’s now turn to what it means to know a word. Obviously, knowing a word means to be able to identify it when reading or listening and use it when writing or speaking. But, what kind of information do you need to know to do all this successfully? In other words, what is it about a word that you need to know?

To answer this question, do the following tasks. The first one introduces you to the basics, while the second covers more advanced information.

Types of vocabulary knowledge I

Types of vocabulary knowledge II

Formal vs. informal

At this point, it is worth mentioning that some of these types of vocabulary knowledge might be more relevant or useful than others, depending on the context and how much you already know. For example, idioms tend to be informal and therefore not appropriate for academic writing, but they can help you sound more natural when socialising with your fellow students:

❌ (in writing)

Researchers have been scratching their heads over the sudden decrease…

✔️ (in speaking)

-Munirah, could you help me with Question 5? I’ve been scratching my head over it all morning!

Similarly, you should always consider whether a word you are learning is formal or informal and appropriate for your studies. For example, the verb ‘get’ is in the Oxford3000 list but it is rather informal. When writing, you would need to use more formal synonyms e.g. obtain, receive, acquire, gain, earn, collect, etc., depending on the meaning of course.

Task: To practise formal and informal vocabulary, do the following task.

So, how do you handle the dictation? If you take things out of LingQs, you don’t get practice hearing and writing them.

For me, as a beginner, having to write the word or phrase helps me hear it better. I have a terrible time with long and short vowels because it’s a matter of duration, not the sound itself as it is in English. Dictation sharpens that. Plus I need to write emails in Czech sometimes, and similar words to my eye are often dramatically different to a Czech reader if I omit the hačky and čarky, those «little pepper flakes above the letters» that are so easy to ignore. This must be true in other languages as well.

Living here I have probably learned to recognize [passive] at least 1,000 nouns, because you can not survive if you don’t know your foods, household cleaners, ingredients on packages, road signs, businesses, etc. I have picked up relatively few verbs or idioms. What I can’t do is have a conversation on a topic that interests me, talk to a doctor or pharmacist who only speaks Czech, or write an email about some business matter [active].

Possibly I am coming at this from a somewhat different angle because I live here in Prague. With much help, I worked my way through Čapek’s Insect Play because I wanted to see it in performance. This did not help my speaking one whit. I love Čapek, though — very witty. I can see why he was considered a master of the Czech language. It is impossible to get that sense from translations. It’s a very long way, however, from household cleaners and radishes to reading Čapek on my own, and to speaking to anyone about it in Czech!!

The continuum on which we can know a word has long been considered. In 1965, Edgar Dale, author of The Living Word Vocabulary and other books on vocabulary development, described four stages of word knowledge development:

- No knowledge of the word; we don’t even know it exists

- Awareness that such a word exists, but we don’t know what it means

- Vague notion of what the word means, in a particular context

- Rich understanding; we know the word well and can use it

With this framework in mind, consider the word ineffable. This may be your first encounter with the word, or you may have seen it or heard it before but really know nothing about it. Or you may apply morphological knowledge of the prefix un- and the context of the sentence What an ineffable sight the Grand Canyon is! to deduce that the word has something to do with “not” and a magnificent scene. If you know the word, you understand that the author is communicating that the beauty and grandeur of the Grand Canyon are beyond words.

Dale’s framework can be useful for getting a sense of what learners know about vocabulary words. By creating a matrix with the four categories as headers and listing the vocabulary words down the side, learners can check off their level of understanding for each of the words, before and after a particular unit of study.

|

Vocabulary Knowledge Rating: American Revolution |

||||

|

Word |

Can Define It/Use It |

Can Tell You Something About It |

Think I’ve Heard of It |

No Idea! |

|

adopt |

||||

|

citizens |

||||

|

colony |

||||

|

democratic |

||||

|

establish |

||||

|

loyal |

||||

|

militia |

||||

|

officials |

||||

|

patriot |

||||

|

represent |

||||

|

revolt |

||||

|

treaty |

Psychologist L. J. Cronbach outlined a continuum of five dimensions, each demonstrating greater depth of understanding:

- Generalization (can define the word)

- Application (can use the word correctly)

- Breadth (know multiple meanings of a word)

- Precision (know when and when not to use a word)

- Availability (can apply the word in discussion and writing; namely, can use it productively)

For instance, dock is a word you likely understand as a place where ships unload and load or are repaired and could use the word appropriately in that narrow sense. But how deep is your understanding of the word? Do you know which of the following meanings also apply to dock?

- to link two more spacecraft together in space

- the fleshy part of an animal’s tail

- to reduce a person’s wages

- the area in which a defendant stands or sits during a trial

- a type of plant

If you identified all of the entries and could use them appropriately, your understanding of dock is very deep.

We can create a matrix similar to the one that follows, based on Cronbach’s work, to document a student’s growth in learning particular words. The matrix also could be adapted to reflect an entire class’s understanding of a particular target word, by recording students’ names where the words are listed.

Assessing Vocabulary Knowledge (B = Before; A = After)

| Child’s Name: JC |

Generalization |

Application |

Breadth (knows multiple meanings of a word) |

Precision |

Availability |

|

B |

A |

|||

|

B |

A |

|||

|

B |

A |

|||

|

B |

A |

|||

|

B |

A |

|||

|

B |

A |

Just as the people we know best are those with whom we have had the most experiences, so too with words: Once we’ve been introduced, our knowledge of them relies on lots of exposures in meaningful contexts. Although paraphrasing may enable readers/listeners to get the gist of a word in order to maintain meaning of a text, it is not likely to lead to learners “owning” the word, being able to access and use it whenever they wish. Estimates vary and words vary, but it can take 40 or more meaningful encounters with a word before owning begins to happen. Therefore, it’s important to remember to bring vocabulary that’s been taught into the daily classroom talk.

As a reminder of that, post a few of the words in a conspicuous place on a Teacher’s Word Wall. As learners begin to use the words, remove the known words and post new ones. Make the learning process active and engaging through raps and songs, games, dramatization, and drawing. And celebrate the enriched talk that can result.

Kathy Ganske is professor of the Practice at Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, with more than 20 years of experience in the classroom. She is current chair of the AERA Vocabulary SIG and author or coauthor/editor of Word Journeys: Assessment-Guided Phonics, Spelling, and Vocabulary Instruction (2nd edition); Write Now! Empowering Writers in Today’s K–6 Classroom; and other works on word study/vocabulary development, supporting struggling readers and writers, and perspectives and practices on comprehension.

Imagine you wanted to explain to a child what lavender was. How would you do it?

You might tell them the word and then show them a drawing. From this, they would get an idea of the shape, the outline and the purple colour of the flower.

Next, you could give them a piece of plastic lavender. This would helps them to understand that it is three-dimensional, how the petals link together, and a sense of weight (probably inaccurate).

But it isn’t until they encounter a bunch of real, fresh lavender, or see it in a garden, that pupils really understand how it looks, smells and feels. They might notice that it isn’t smooth like the plastic version. They might realise that it feels solid, yet fragile.

Finally, you could ask them to compare the lavender with a rose and a bunch of parsley. Together, you’d begin to consider which essential qualities made it lavender, rather than another flower or herb. They’d begin to have a sense of how it might be used and why it might be valued. And then, if they read a poem that described someone as smelling of lavender, they could begin to make sense of the inferred meaning the poet was trying to convey.

This, in essence, is the way in which children learn and understand words, grow their vocabularies and extend their nuanced knowledge of the world.

A deeper approach to vocabulary

James Law and his colleagues describe this process in their report on early language development for the EEF, explaining that learning vocabulary is a sequence that moves from learning to recognise and produce the sound of a word, to learning the meaning of the word, and then how to develop the representation of the word and generalise the word correctly.

To gain a strong understanding of words — what cognitive psychologists call “lexical quality” — we need to understand how the word sounds, how it is written, how it is used grammatically, how it can be changed, and the many semantic meanings and uses of the word. It is useful for us to help children understand words as units of meaning, as families, rather than relying on teaching single, isolated definitions of the sort you might find in a dictionary.

Take the word “mountain”, for example. It can be used in different ways in different texts, in different genres and for different purposes. A text about the life of animals might describe them living “in the mountains of Western China”. This is probably the most common use of the word: describing tall, geographical features, often shown covered in snow.

A child who had visited mountains might have a greater understanding of their enormity, strength and power. They would begin to have a sense of what it meant to be a mountain and the challenge of living on one.

Opportunities to ‘explore’ words

In a different genre, a character might be described as being “as solid as a mountain”, or “mountainous”. A child with a nuanced, generalised and deep understanding of the word “mountain” would find it much easier to appreciate what the writer meant by this.

This depth of understanding is needed for readers to make sense of the intricate associations that good writers create. It isn’t enough to just be able to pronounce a word. We need to give children the opportunity to share and explore words in the widest sense possible — and to help them understand how words work in the widest sense possible.

So, the next time a child asks you what a word means, take the time to help them go a little deeper. Ask them what they think it means, if they have ever seen the word used elsewhere, if they know other words that mean the same and then define the word together.

We need, as teachers, to develop a deeper understanding ourselves of what it means to really know a word.

Megan Dixon is director of literacy at the Aspire Educational Trust