When looking into the origins of a word, we can usually find usage guidelines as well as what it actually means. When we take the word “sex”, this is especially important. In this article, we’ll be looking at how the word formed in order to understand its present day usage. Do you know what sex means?

Sex is, without a doubt, a peculiar and special word, loaded with all sorts of connotations for its usage. It’s always one of the topics most frequently searched for online, and is popular in conversations at the local pub or bar. But do you know what sex means?

People talk about it so much, and yet, at the same time, it can be equally taboo. Depending on the person, country, or situation, it can be either a very popular topic or one that people tend to ignore.

What we do know is that it’s a polysemic word. However, it’s curious how this polysemy is related to how badly we’ve used this word throughout history. The meanings of words change progressively. And, in the case of the word sex, its meaning has evolved and changed as a result of different events, whether social, political, or religious. Let’s have a closer look at all of this.

Where does the word sex come from?

The Athenian playwright Aristophanes (444 B.C. – 385 B.C.) is responsible for the fact that we have this word in our vocabulary. He’s one of the characters that we find in The Symposium, a series of dialogues of incalculable philosophical value written by Plato. These dialogues take place in the context of a dinner in which several guests, including Socrates and Aristophanes himself, talk about love and Eros.

Aristophanes, in this dinner, talks about the famous idea of androgyny. In this idea, beings can belong to three different categories: male, female, and androgynous. A person who’s androgynous would have both masculine and feminine characteristics. The word comes from the Latin (andrós, man and giné, woman), and is a union of these two characteristics.

However, this playwright took the idea to an extreme. He described androgynous people as “complete” beings with four arms, four legs, two faces, and two different sets of genitals.

These beings were defined as rounded, complete, and powerful. So powerful that they tried to defy the gods. Zeus decided to punish them for such an offense. Their punishment consisted of cutting these beings in half so that they wouldn’t be such vigorous, powerful and, above all, complete people.

This myth tells about every man and woman would then long to find their “other part”. Only then would they be able to feel “complete” again. Here we can find the origin of the phrase “our better half”. So, as the myth goes, these beings went from being complete to being “sectioned”, and this is exactly where we get the word sex from. Sex comes from sexare, which means “separated”, “severed”, or “cut off”.

What are the uses of the word sex today?

To find out what sex means, we need to look at the etymology of the word. This contrasts with the uses we usually give it nowadays, which are frequently summarized in these three:

The “sex that we have”

With this use of the word, we see that, nowadays, sex means an intimate sexual encounter with other people. Statements like “I haven’t had sex in a long time” or “I had sex with a guy yesterday” associate “sex” with intercourse. Such use is especially frequent in the headlines and articles we see in the media.

If we go even deeper and analyze what it means to have a sexual relationship based on the original meaning, then we’d talk about relationships “between sexes” (of any kind). That’s why we often talk about “erotic relationships”. This term describes a more specific and intimate type of relationship (it alludes to Eros, which implies desire, attraction, and love).

The “sex that you possess”

This usage refers to our genitals, but it isn’t correctly used. Despite what many people believe, our genitals don’t define our sex. Or, to put another way, our genitals don’t determine our sexual identity.

It’s true that this usage of the word sex as a synonym for genitals isn’t anywhere nearly as frequent as the previous use, but you can still read phrases like “she shaved her sex”.

The “sex that we are”

This is the most correct and harmonious use of the word with respect to its origins, and here we can find what sex means. This expression is the one that gives sense to sexology, since it’s the one that refers to sexual identity. This refers to the fact that we’re sexual beings, using “sex” as a differentiator and a powerful source of diversity.

Language builds behaviors, attitudes, and mental overviews. That’s why it’s important for the word sex to have a much more harmonious usage. This way, we can place each concept where it corresponds, allowing us to describe reality in the best possible way.

If reality isn’t described correctly, then we’ll never be able to ask the right questions about it, let alone get the correct answers.

It might interest you…

History

The etymology of getting it on.

Eons before Salt-N-Pepa recorded their boundary-pushing hit, humans have been talking about sex—but the ways we’ve done so have invariably shifted over time. From the Biblical sense of ‘knowing someone’ to more modern synonyms for sex (anyone care to do the devil’s dance?), our language around intimacy has shifted just as the taboos around it have, too.

Early origins

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “sex” itself stems from Old French, with an origin around 1200. At that time, the word simply referred to genitals. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century when it was first used to refer to the act of intercourse, and this usage became more popular in the earlier 20th century. So how did we refer to the act before then?

Latin roots

Well, around 1300, the word “fornication” arose, also from Old French’s “fornicacion,” which has the Latin root “fornix,” which means “arch.” So the story goes: prostitutes in ancient Rome hung out under vaulted ceilings, which gave this seemingly standard architectural word a risqué connotation—and this root is also why the word fornication is strictly used to refer to two people who are not married to one another.

Biblical sense

While the Bible’s use of “knowing” seems to stretch long across time, this word usage originates around 1200, from translations of Genesis in the Old Testament: Adam knew his wife, Eve. And now, centuries later, we use this euphemism cheekily, adding “in the biblical sense” as a tag on to a passing remark.

The f-word

It might come as a surprise that the seemingly most modern way we refer to coitus—good old “fuck”—has a centuries-long history, too. According to Dictionary.com, this word was first recorded in a dictionary in 1598, and has Old Germanic roots in the word ficken or fucken—which means to “strike or penetrate” and Latin roots in words that translate roughly “to prick or puncture.” The word was relatively common at its origin, but by the 18th century, came to be considered vulgar, and it was even banned from the Oxford English Dictionary. In 1960, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, the word started to lose at least a little bit of its taboo, thanks to the often-banned novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence, which uses the word frequently enough that its publishers had to go to court to have it ruled fair for publication.

Shakespeare’s innuendos

Over time, there are countless other words we’ve used to describe getting it on, from Shakespeare’s countless innuendos (stabbed, fubbed off), to 1650’s development of the word “come,” which has been used cheekily pretty much ever since. If one thing’s clear from history, no single word can ever seem to do the act justice.

Related Products

Related

If the immutable character of sex is contested, perhaps this construct called ˜sex™ is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turns out to be no distinction at all. ❋ Mikkola, Mari (2008)

Lani say: I don’t love sex@ carmically sex is quite cool. ❋ Evolver (2004)

The venereal diseases are passed on from one sex to the other in a continuous chain, but the chain can be broken at any time _by either sex_. ❋ Ettie A. Rout (1899)

It is only the man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual instinct that could give that stunted, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race the name of _the fair sex_; for the entire beauty of the sex is based on this instinct. ❋ Arthur Schopenhauer (1824)

Because if sex was involuntary then it was not ’sex’ but rape. ❋ Unknown (2010)

February 18, 2009 at 12:26 pm 1. Internet Pornography 2. Illegal downloading of music 3. Ignorance 4. Myself 5. Depression (well mostly, still working on it, seems to take a different form these days) 6. The Devil (still working on him too lol) 7. Loneliness 8. Pre-marital sex 9. Internet ’sex’ and ‘relationships’ (don’t ask) ❋ Unknown (2008)

In fact, whenever she was forced to say the word sex or anything pertaining to it, she put it in verbal quotes and wrinkled her nose. ❋ Terri Cheney (2011)

I do wish he’d get over the constant-sex thing, because, number one, sex is private and he doesn’t need to share, and, number two, not everyone engages in sex as it’s messy, and, as I’ve been told, may involve nudity. ❋ Nissa_amas_katoj (2009)

The sooner we stop using the expression «sex crimes», the sooner will we be able to address the stark fact that these are acts of violence which hijack the sexual organs for the purpose of the humiliation and violation. ❋ Unknown (2011)

First though, take a look at this Google search using the term sex toy laws. ❋ Dave (2009)

MORET: Dr. Dr.w, though, many people would hear the term sex addict and say, wait a minute; you’re giving this guy an excuse. ❋ Unknown (2009)

The young girl’s interest in sex is obvious through her flirtations and joyful interactions, but her Aunt’s graphic imaginings manifest as perverse and brackish what she fantasizes that Catharine is literally doing, leading her to imagine her niece playing the willing companion — and even the temptress — to ❋ Unknown (2006)

Today I posted about this topic as inspired by my last topic: women and our sexuality as in sex is NOT taboo or something to be ashamed of, embarassed of. ❋ Unknown (2006)

I probably would have gone into the bedroom that moment, but something about how he said the word sex turned me off. ❋ Susie Scott Krabacher (2007)

In an Internet search of the term sex and god, which one do you think would get more hits? ❋ Unknown (2007)

The coverart is much, much better than the interiors, but this stuff gives the term sex and violence a new meaning. ❋ Unknown (2006)

im going [to go] [have sex] in [the toilet] ❋ Jerry The Wanking Dolphin (2018)

[are you] ever going to [have sex with me] or are you just going to [masterbate] ❋ Master#fuck (2018)

«I got fucked, John.»

«Realy, by who?»

«[Stupid question] [pussyhole]. It was us.»

«Yes, [sex babe].» ❋ Sophieisapatheticthot66 (2022)

[10 year old]: I HAD SEX WITH [UR MOM] LAST NIGHT [HER ASS] WAS SO FUCKING BIG!!!! ❋ Nimnex (2018)

Bro, I just [looked up] [sex on] urban dictionary. It was so much better than [porn]. ❋ Sex:) (2012)

2 [squared] is 4, 2 [cubed] is 8, and 2 [sexed] is 64.

If you sex six, the result is 46656 ❋ MethemethicsProfessor (2019)

It was a cold winter night when Tom had his girlfriend [Shelia] over. Things were getting steamy. Shelia was still a virgin and tonight was the night she told Tom. Tom put his hands down her pants and got her all [warmed up]. She took off her top exposing her large breasts. «Let’s go.» she said as she pushed her body on top of his. Unbuttoning his pants. She [unzipped] his jeans and pulled them down toward his knees. he shook them off and she rubbed her body on his for a moment before taking her bra off right in his face. Tom was hard already. «Whenever your ready.» Tom said smiling. He couldn’t wait to get inside her. She traced his chest with his finger until she reached his dick. she brought her mouth down to his [nine inch] cock and gave him a long tasteful blow job by [lapping] his cock and licking up the sides. he [moaned] then came into her mouth and she swallowed it all. he thought it was so sexy. Tom took off [Shelia’s] thong and procceded to eat her out. She exploded and moaned. «Let’s just fuck.» she said as she jumped ontop of Tom. She rode his huge cock like a professional. Grinding her hips into his crotch. She moaned and humped into him more. he resisited cumming into her. she had an orgasm and they switched positions. he [took her from behind] this time doggy style. She moaned and took it in the back of her hot wet pussy. popping her cherry was amazing she was so tight Tom thought. «Harder!!» Shelia [squealed]. Tom pumped his hard cock into her she had a second orgasm. he soon came into her pussy and they laid next to eachother that night remembering the wonderful sex. they had hot sex the next morning. ❋ Newdirector (2009)

soaked and aching for him. «[count to ten] and follow» i whispered [sexily], giving his dick one last squeeze and leaving the club, fingering myself. he followed and i wasted no time in shoving his dick inside me. we went hard and fast, in out in out in — in — in ORGASM OOOOOOOOOOOOOOH FUCKing HELL breasts flapping up and down….

[i breathed] heavily as he squirted inside me, french kissing him, squeezing his ass and then i had another orgasm as he hit my g — spot. i collapsed into his arms and he kissed me long and hard, still inside me. then it happened again. ❋ HoHoHoGreenGiant (2011)

I did [the middle finger] right now because you gave a shit to calling people [morons].

Rude. They can [look up] sex if you want. ❋ Cat_Cat (2016)

sex is something [im gonna] do when im [married]

but reading it is [interesting] and funny ❋ Jen127 (2009)

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes.[1][2] Male plants and animals produce small mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger, non-motile ones (ova, often called egg cells).[3] Organisms that produce both types of gametes are called hermaphrodites.[2][4] During sexual reproduction, male and female gametes fuse to form zygotes, which develop into offspring that inherit traits from each parent.

Males and females of a species may have physical similarities (sexual monomorphism) or differences (sexual dimorphism) that reflect various reproductive pressures on the respective sexes. Mate choice and sexual selection can accelerate the evolution of physical differences between the sexes.

The terms male and female typically do not apply in sexually undifferentiated species in which the individuals are isomorphic (look the same) and the gametes are isogamous (indistinguishable in size and shape), such as the green alga Ulva lactuca. Some kinds of functional differences between gametes, such as in fungi,[5] may be referred to as mating types.[6]

The sex of a living organism is determined by its genes. Most mammals have the XY sex-determination system, where male mammals usually carry an X and a Y chromosome (XY), whereas female mammals usually carry two X chromosomes (XX). Other chromosomal sex-determination systems in animals include the ZW system in birds, and the X0 system in insects. Various environmental systems include temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles and crustaceans.[7]

Sexual reproduction

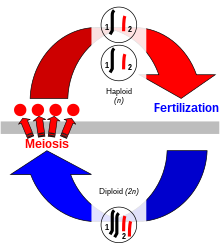

The life cycle of sexually reproducing organisms cycles through haploid and diploid stages

Sexual reproduction is a process exclusive to eukaryotes in which organisms produce offspring that possess a selection of the genetic traits of each parent. Genetic traits are contained within the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of chromosomes. The cells of eukaryotes have a set of paired homologous chromosomes, one from each parent, and this double-chromosome stage is called «diploid». During sexual reproduction, diploid organisms produce specialized haploid sex cells called gametes via meiosis,[8] each of which has a single set of chromosomes. Meiosis involves a stage of genetic recombination via chromosomal crossover, in which regions of DNA are exchanged between matched pairs of chromosomes, to form new chromosomes each with a new and unique combination of the genes of the parents. Then the chromosomes are separated into single sets in the gametes. Each gamete in the offspring thus has half of the genetic material of the mother and half of the father.[9] The combination of chromosomal crossover and fertilization, bringing the two single sets of chromosomes together to make a new diploid zygote, results in new organisms that contain different sets of the genetic traits of each parent.

In animals, the haploid stage only occurs in the gametes, the haploid cells that are specialized to fuse to form a zygote that develops into a new diploid organism. In plants, the diploid organism produces haploid spores by meiosis that are capable of undergoing repeated cell division to produce multicellular haploid organisms. In either case, gametes may be externally similar (isogamy) as in the green alga Ulva or may be different in size and other aspects (anisogamy).[10] The size difference is greatest in oogamy, a type of anisogamy in which a small, motile gamete combines with a much larger, non-motile gamete.[11]

By convention, the larger gamete (called an ovum, or egg cell) is considered female, while the smaller gamete (called a spermatozoon, or sperm cell) is considered male. An individual that produces exclusively large gametes is female, and one that produces exclusively small gametes is male.[12] An individual that produces both types of gametes is a hermaphrodite. In some cases, hermaphrodites are able to self-fertilize and produce offspring on their own, without the need for a partner.

Animals

Most sexually reproducing animals spend their lives as diploid, with the haploid stage reduced to single-cell gametes.[13] The gametes of animals have male and female forms—spermatozoa and egg cells. These gametes combine to form embryos which develop into new organisms.

The male gamete, a spermatozoon (produced in vertebrates within the testes), is a small cell containing a single long flagellum which propels it.[14]

Spermatozoa are extremely reduced cells, lacking many cellular components that would be necessary for embryonic development. They are specialized for motility, seeking out an egg cell and fusing with it in a process called fertilization.

Female gametes are egg cells. In vertebrates, they are produced within the ovaries. They are large, immobile cells that contain the nutrients and cellular components necessary for a developing embryo.[15] Egg cells are often associated with other cells which support the development of the embryo, forming an egg. In mammals, the fertilized embryo instead develops within the female, receiving nutrition directly from its mother.

Animals are usually mobile and seek out a partner of the opposite sex for mating. Animals which live in the water can mate using external fertilization, where the eggs and sperm are released into and combine within the surrounding water.[16] Most animals that live outside of water, however, use internal fertilization, transferring sperm directly into the female to prevent the gametes from drying up.

In most birds, both excretion and reproduction are done through a single posterior opening, called the cloaca—male and female birds touch cloaca to transfer sperm, a process called «cloacal kissing».[17] In many other terrestrial animals, males use specialized sex organs to assist the transport of sperm—these male sex organs are called intromittent organs. In humans and other mammals, this male organ is the penis, which enters the female reproductive tract (called the vagina) to achieve insemination—a process called sexual intercourse. The penis contains a tube through which semen (a fluid containing sperm) travels. In female mammals, the vagina connects with the uterus, an organ which directly supports the development of a fertilized embryo within (a process called gestation).

Because of their motility, animal sexual behavior can involve coercive sex. Traumatic insemination, for example, is used by some insect species to inseminate females through a wound in the abdominal cavity—a process detrimental to the female’s health.

Plants

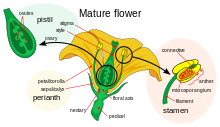

Flowers contain the sexual organs of flowering plants, usually containing both male and female parts.

Like animals, land plants have specialized male and female gametes.[18][19] In seed plants, male gametes are produced by reduced male gametophytes that are contained within hard coats, forming pollen. The female gametes of seed plants are contained within ovules. Once fertilized, these form seeds which, like eggs, contain the nutrients necessary for the initial development of the embryonic plant.

Female (left) and male (right) cones contain the sex organs of pines and other conifers.

The flowers of flowering plants contain their sexual organs. Flowers are usually hermaphroditic, containing both male and female sexual organs. The female parts, in the center of a flower, are the pistils, each unit consisting of a carpel, a style and a stigma. Two or more of these reproductive units may be merged to form a single compound pistil, the fused carpels forming an ovary. Within the carpels are ovules which develop into seeds after fertilization. The male parts of the flower are the stamens: these consist of long filaments arranged between the pistil and the petals that produce pollen in anthers at their tips. When a pollen grain lands upon the stigma on top of a carpel’s style, it germinates to produce a pollen tube that grows down through the tissues of the style into the carpel, where it delivers male gamete nuclei to fertilize an ovule that eventually develops into a seed.

Some hermaphroditic plants are self-fertile, but plants have evolved multiple different self-incompatibility mechanisms to avoid self-fertilization, involving sequential hermaphroditism, molecular recognition systems and morphological mechanisms such as heterostyly.[20]: 73, 74

In pines and other conifers, the sex organs are produced within cones that have male and female forms. Male cones are smaller than female ones and produce pollen, which is transported by wind to land in female cones. The larger and longer-lived female cones are typically more durable, and contain ovules within them that develop into seeds after fertilization.

Because seed plants are immobile, they depend upon passive methods for transporting pollen grains to other plants. Many, including conifers and grasses, produce lightweight pollen which is carried by wind to neighboring plants. Some flowering plants have heavier, sticky pollen that is specialized for transportation by insects or larger animals such as hummingbirds and bats, which may be attracted to flowers containing rewards of nectar and pollen. These animals transport the pollen as they move to other flowers, which also contain female reproductive organs, resulting in pollination.

Fungi

Mushrooms are produced as part of fungal sexual reproduction

Most fungi reproduce sexually and have both haploid and diploid stages in their life cycles. These fungi are typically isogamous, lacking male and female specialization: haploid fungi grow into contact with each other and then fuse their cells. In some of these cases, the fusion is asymmetric, and the cell which donates only a nucleus (and not accompanying cellular material) could arguably be considered «male».[21] Fungi may also have more complex allelic mating systems, with other sexes not accurately described as male, female, or hermaphroditic.[22]

Some fungi, including baker’s yeast, have mating types that create a duality similar to male and female roles. Yeast with the same mating type will not fuse with each other to form diploid cells, only with yeast carrying the other mating type.[23]

Many species of higher fungi produce mushrooms as part of their sexual reproduction. Within the mushroom, diploid cells are formed, later dividing into haploid spores. The height of the mushroom aids in the dispersal of these sexually produced offspring.[citation needed]

Sexual systems

A sexual system is a distribution of male and female functions across organisms in a species.[24]

Animals

Approximately 95% of animal species have separate male and female individuals, and are said to be gonochoric. About 5% of animal species are hermaphroditic.[24] This low percentage is due to the very large number of insect species, in which hermaphroditism is absent.[25] About 99% of vertebrates are gonochoric, and the remaining 1% that are hermaphroditic are almost all fishes.[26]

Plants

The majority of plants are bisexual,[27]: 212 either hermaphrodite (with both stamens and pistil in the same flower) or monoecious.[28][29] In dioecious species male and female sexes are on separate plants.[30] About 5% of flowering plants are dioecious, resulting from as many as 5000 independent origins.[31] Dioecy is common in gymnosperms, in which about 65% of species are dioecious, but most conifers are monoecious.[32]

Evolution of sex

Different forms of anisogamy:

A) anisogamy of motile cells, B) oogamy (egg cell and sperm cell), C) anisogamy of non-motile cells (egg cell and spermatia).

Different forms of isogamy:

A) isogamy of motile cells, B) isogamy of non-motile cells, C) conjugation.

It is generally accepted that isogamy was ancestral to anisogamy[33] and that anisogamy evolved several times independently in different groups of eukaryotes, including protists, algae, plants, and animals.[25] The evolution of anisogamy is synonymous with the origin of male and the origin of female.[34] It is also the first step towards sexual dimorphism[35] and influenced the evolution of various sex differences.[36]

However, the evolution of anisogamy has left no fossil evidence[37] and until 2006 there was no genetic evidence for the evolutionary link between sexes and mating types.[38] It is unclear whether anisogamy first led to the evolution of hermaphroditism or the evolution of gonochorism.[27]: 213

But a 1.2 billion year old fossil from Bangiomorpha pubescens has provided the oldest fossil record for the differentiation of male and female reproductive types and shown that sexes evolved early in eukaryotes.[39]

The original form of sex was external fertilization. Internal fertilization, or sex as we know it, evolved later[40] and became dominant for vertebrates after their emergence on land.[41]

Sex-determination systems

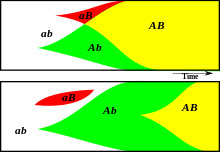

Sex helps the spread of advantageous traits through recombination. The diagrams compare the evolution of allele frequency in a sexual population (top) and an asexual population (bottom). The vertical axis shows frequency and the horizontal axis shows time. The alleles a/A and b/B occur at random. The advantageous alleles A and B, arising independently, can be rapidly combined by sexual reproduction into the most advantageous combination AB. Asexual reproduction takes longer to achieve this combination because it can only produce AB if A arises in an individual which already has B or vice versa.

The biological cause of an organism developing into one sex or the other is called sex determination. The cause may be genetic, environmental, haplodiploidy, or multiple factors.[25] Within animals and other organisms that have genetic sex-determination systems, the determining factor may be the presence of a sex chromosome. In plants that are sexually dimorphic, such as Ginkgo biloba,[20]: 203 the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha or the dioecious species in the flowering plant genus Silene, sex may also be determined by sex chromosomes.[42] Non-genetic systems may use environmental cues, such as the temperature during early development in crocodiles, to determine the sex of the offspring.[43]

Sex determination is often distinct from sex differentiation. Sex determination is the designation for the development stage towards either male or female while sex differentiation is the pathway towards the development of the phenotype.[44]

Genetic

XY sex determination

Humans and most other mammals have an XY sex-determination system: the Y chromosome carries factors responsible for triggering male development, making XY sex determination mostly based on the presence or absence of the Y chromosome. It is the male gamete that determines the sex of the offspring.[45] In this system XX mammals typically are female and XY typically are male.[25] However, individuals with XXY or XYY are males, while individuals with X and XXX are females.[7] Unusually, the platypus, a monotreme mammal, has ten sex chromosomes; females have ten X chromosomes, and males have five X chromosomes and five Y chromosomes. Platypus egg cells all have five X chromosomes, whereas sperm cells can either have five X chromosomes or five Y chromosomes.[46]

XY sex determination is found in other organisms, including insects like the common fruit fly,[47] and some plants.[48] In some cases, it is the number of X chromosomes that determines sex rather than the presence of a Y chromosome.[7] In the fruit fly individuals with XY are male and individuals with XX are female; however, individuals with XXY or XXX can also be female, and individuals with X can be males.[49]

ZW sex determination

In birds, which have a ZW sex-determination system, the W chromosome carries factors responsible for female development, and default development is male.[50] In this case, ZZ individuals are male and ZW are female. It is the female gamete that determines the sex of the offspring. This system is used by birds, some fish, and some crustaceans.[7]

The majority of butterflies and moths also have a ZW sex-determination system. Females can have Z, ZZW, and even ZZWW.[51]

XO sex determination

In the X0 sex-determination system, males have one X chromosome (X0) while females have two (XX). All other chromosomes in these diploid organisms are paired, but organisms may inherit one or two X chromosomes. This system is found in most arachnids, insects such as silverfish (Apterygota), dragonflies (Paleoptera) and grasshoppers (Exopterygota), and some nematodes, crustaceans, and gastropods.[52][53]

In field crickets, for example, insects with a single X chromosome develop as male, while those with two develop as female.[54]

In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, most worms are self-fertilizing hermaphrodites with an XX karyotype, but occasional abnormalities in chromosome inheritance can give rise to individuals with only one X chromosome—these X0 individuals are fertile males (and half their offspring are male).[55]

ZO sex determination

In the Z0 sex-determination system, males have two Z chromosomes whereas females have one. This system is found in several species of moths.[56]

Environmental

For many species, sex is not determined by inherited traits,[citation needed] but instead by environmental factors such as temperature experienced during development or later in life.[citation needed]

In the fern Ceratopteris and other homosporous fern species, the default sex is hermaphrodite, but individuals which grow in soil that has previously supported hermaphrodites are influenced by the pheromone antheridiogen to develop as male.[57] The bonelliidae larvae can only develop as males when they encounter a female.[25]

Sequential hermaphroditism

Clownfishes are initially male; the largest fish in a group becomes female

Some species can change sex over the course of their lifespan, a phenomenon called sequential hermaphroditism.[58] Teleost fishes are the only vertebrate lineage where sequential hermaphroditism occurs. In clownfish, smaller fish are male, and the dominant and largest fish in a group becomes female; when a dominant female is absent, then her partner changes sex.[clarification needed] In many wrasses the opposite is true—the fish are initially female and become male when they reach a certain size.[59] Sequential hermaphroditism also occurs in plants such as Arisaema triphyllum.

Temperature-dependent sex determination

Many reptiles, including all crocodiles and most turtles, have temperature-dependent sex determination. In these species, the temperature experienced by the embryos during their development determines their sex.[25] In some turtles, for example, males are produced at lower temperatures than females; but Macroclemys females are produced at temperatures lower than 22 °C or above 28 °C, while males are produced in between those temperatures.[60]

Haplodiploidy

Other insects,[clarification needed] including honey bees and ants, use a haplodiploid sex-determination system.[61] Diploid bees and ants are generally female, and haploid individuals (which develop from unfertilized eggs) are male. This sex-determination system results in highly biased sex ratios, as the sex of offspring is determined by fertilization (arrhenotoky or pseudo-arrhenotoky resulting in males) rather than the assortment of chromosomes during meiosis.[62]

Sex ratio

A sex ratio is the ratio of males to females in a population. As explained by Fisher’s principle, for evolutionary reasons this is typically about 1:1 in species which reproduce sexually.[63][64] However, many species deviate from an even sex ratio, either periodically or permanently. Examples include parthenogenic species, periodically mating organisms such as aphids, some eusocial wasps, bees, ants, and termites.[65]

The human sex ratio is of particular interest to anthropologists and demographers. In human societies, sex ratios at birth may be considerably skewed by factors such as the age of mother at birth[66] and by sex-selective abortion and infanticide. Exposure to pesticides and other environmental contaminants may be a significant contributing factor as well.[67] As of 2014, the global sex ratio at birth is estimated at 107 boys to 100 girls (1,000 boys per 934 girls).[68].

Sex differences

Anisogamy is the fundamental difference between male and female.[69][70] Richard Dawkins has stated that it is possible to interpret all the differences between the sexes as stemming from this.[71]

Sex differences in humans include a generally larger size and more body hair in men, while women have larger breasts, wider hips, and a higher body fat percentage. In other species, there may be differences in coloration or other features, and may be so pronounced that the different sexes may be mistaken for two entirely different taxa.[72]

Sexual dimorphism

In many animals and some plants, individuals of male and female sex differ in size and appearance, a phenomenon called sexual dimorphism.[73] Sexual dimorphism in animals is often associated with sexual selection—the mating competition between individuals of one sex vis-à-vis the opposite sex.[72] In many cases, the male of a species is larger than the female. Mammal species with extreme sexual size dimorphism tend to have highly polygynous mating systems—presumably due to selection for success in competition with other males—such as the elephant seals. Other examples demonstrate that it is the preference of females that drives sexual dimorphism, such as in the case of the stalk-eyed fly.[74]

Females are the larger sex in a majority of animals.[73] For instance, female southern black widow spiders are typically twice as long as the males.[75] This size disparity may be associated with the cost of producing egg cells, which requires more nutrition than producing sperm: larger females are able to produce more eggs.[76][73]

Sexual dimorphism can be extreme, with males, such as some anglerfish, living parasitically on the female. Some plant species also exhibit dimorphism in which the females are significantly larger than the males, such as in the moss genus Dicranum[77] and the liverwort genus Sphaerocarpos.[78] There is some evidence that, in these genera, the dimorphism may be tied to a sex chromosome,[78][79] or to chemical signalling from females.[80]

In birds, males often have a more colorful appearance and may have features (like the long tail of male peacocks) that would seem to put them at a disadvantage (e.g. bright colors would seem to make a bird more visible to predators). One proposed explanation for this is the handicap principle.[81] This hypothesis argues that, by demonstrating he can survive with such handicaps, the male is advertising his genetic fitness to females—traits that will benefit daughters as well, who will not be encumbered with such handicaps.

Sexual characteristics

Sex differences in behavior

The sexes across gonochoric species usually differ in behavior. In most animal species females invest more in parental care,[82] although in some species, such as some coucals, the males invest more parental care.[83] Females also tend to be more choosy for who they mate with,[84] such as most bird species.[85] Males tend to be more competitive for mating than females.[34]

See also

- Mating type

- Sexing

- Sex allocation

- Sex and gender distinction

- Sex assignment

- Sex organ

References

- ^ Stevenson A, Waite M (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Book & CD-ROM Set. OUP Oxford. p. 1302. ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Sex: Either of the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions. The fact of belonging to one of these categories. The group of all members of either sex.

- ^ a b Purves WK, Sadava DE, Orians GH, Heller HC (2000). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

A single body can function as both male and female. Sexual reproduction requires both male and female haploid gametes. In most species, these gametes are produced by individuals that are either male or female. Species that have male and female members are called dioecious (from the Greek for ‘two houses’). In some species, a single individual may possess both female and male reproductive systems. Such species are called monoecious («one house») or hermaphroditic.

- ^ Royle NJ, Smiseth PT, Kölliker M (9 August 2012). Kokko H, Jennions M (eds.). The Evolution of Parental Care. Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-969257-6.

The answer is that there is an agreement by convention: individuals producing the smaller of the two gamete types-sperm or pollen- are males, and those producing larger gametes-eggs or ovules- are females.

- ^ Avise JC (18 March 2011). Hermaphroditism: A Primer on the Biology, Ecology, and Evolution of Dual Sexuality. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-231-52715-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Moore D, Robson JD, Trinci AP (2020). 21st Century guidebook to fungi (2 ed.). Cambridge University press. pp. 211–228. ISBN 978-1-108-74568-0.

- ^ Kumar R, Meena M, Swapnil P (2019). «Anisogamy». In Vonk J, Shackelford T (eds.). Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_340-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6.

Anisogamy can be defined as a mode of sexual reproduction in which fusing gametes, formed by participating parents, are dissimilar in size.

- ^ a b c d Hake L, O’Connor C. «Genetic Mechanisms of Sex Determination | Learn Science at Scitable». www.nature.com. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V. 20. Meiosis», U.S. NIH, V. 20. Meiosis Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), U.S. National Institutes of Health, «V. 20. The Benefits of Sex Archived 22 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Gilbert (2000), «1.2. Multicellularity: Evolution of Differentiation». 1.2.Mul Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, NIH.

- ^ Allaby M (29 March 2012). A Dictionary of Plant Sciences. OUP Oxford. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-19-960057-1.

- ^ Gee, Henry (22 November 1999). «Size and the single sex cell». Nature. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «3. Mendelian genetics in eukaryotic life cycles», U.S. NIH, 3. Mendelian/eukaryotic Archived 2 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Sperm», U.S. NIH, V.20. Sperm Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Eggs», U.S. NIH, V.20. Eggs Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Fertilization», U.S. NIH, V.20. Fertilization Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ritchison, G. «Avian Reproduction». Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). «Gamete Production in Angiosperms». Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- ^ Dusenbery DB (2009). Living at Micro Scale: The Unexpected Physics of Being Small. Harvard University Press. pp. 308–326. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ a b Judd, Walter S.; Campbell, Christopher S.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Stevens, Peter F.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2002). Plant systematics, a phylogenetic approach (2 ed.). Sunderland MA, US: Sinauer Associates Inc. ISBN 0-87893-403-0.

- ^ Nick Lane (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-19-280481-5.

- ^ Watkinson SC, Boddy L, Money N (2015). The Fungi. Elsevier Science. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-12-382035-8. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Matthew P. Scott; Paul Matsudaira; Harvey Lodish; James Darnell; Lawrence Zipursky; Chris A. Kaiser; Arnold Berk; Monty Krieger (2000). Molecular Cell Biology (Fourth ed.). WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.14.1. Cell-Type Specification and Mating-Type Conversion in Yeast Archived 1 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Leonard, J. L. (22 August 2013). «Williams’ Paradox and the Role of Phenotypic Plasticity in Sexual Systems». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 53 (4): 671–688. doi:10.1093/icb/ict088. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 23970358.

- ^ a b c d e f Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, et al. (July 2014). «Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it?». PLOS Biology. 12 (7): e1001899. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899. PMC 4077654. PMID 24983465.

- ^ Kuwamura T, Sunobe T, Sakai Y, Kadota T, Sawada K (1 July 2020). «Hermaphroditism in fishes: an annotated list of species, phylogeny, and mating system». Ichthyological Research. 67 (3): 341–360. doi:10.1007/s10228-020-00754-6. ISSN 1616-3915. S2CID 218527927.

- ^ a b Kliman, Richard (2016). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 212–224. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Sabath N, Goldberg EE, Glick L, Einhorn M, Ashman TL, Ming R, et al. (February 2016). «Dioecy does not consistently accelerate or slow lineage diversification across multiple genera of angiosperms». The New Phytologist. 209 (3): 1290–300. doi:10.1111/nph.13696. PMID 26467174.

- ^ Beentje H (2016). The Kew plant glossary (2 ed.). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Kew Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84246-604-9.

- ^ Leite Montalvão, Ana Paula; Kersten, Birgit; Fladung, Matthias; Müller, Niels Andreas (2021). «The Diversity and Dynamics of Sex Determination in Dioecious Plants». Frontiers in Plant Science. 11: 580488. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.580488. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 7843427. PMID 33519840.

- ^ Renner, Susanne S. (2014). «The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database». American Journal of Botany. 101 (10): 1588–1596. doi:10.3732/ajb.1400196. PMID 25326608.

- ^ Walas Ł, Mandryk W, Thomas PA, Tyrała-Wierucka Ż, Iszkuło G (2018). «Sexual systems in gymnosperms: A review» (PDF). Basic and Applied Ecology. 31: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2018.05.009. S2CID 90740232.

- ^ Kumar, Awasthi & Ashok. Textbook of Algae. Vikas Publishing House. p. 363. ISBN 978-93-259-9022-7.

- ^ a b Lehtonen J, Kokko H, Parker GA (October 2016). «What do isogamous organisms teach us about sex and the two sexes?». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1706). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0532. PMC 5031617. PMID 27619696.

- ^ Togashi, Tatsuya; Bartelt, John L.; Yoshimura, Jin; Tainaka, Kei-ichi; Cox, Paul Alan (21 August 2012). «Evolutionary trajectories explain the diversified evolution of isogamy and anisogamy in marine green algae». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (34): 13692–13697. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10913692T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203495109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3427103. PMID 22869736.

- ^ Székely, Tamás; Fairbairn, Daphne J.; Blanckenhorn, Wolf U. (5 July 2007). Sex, Size and Gender Roles: Evolutionary Studies of Sexual Size Dimorphism. OUP Oxford. pp. 167–169, 176, 185. ISBN 978-0-19-920878-4.

- ^ Pitnick SS, Hosken DJ, Birkhead TR (21 November 2008). Sperm Biology: An Evolutionary Perspective. Academic Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-08-091987-4.

- ^ Sawada, Hitoshi; Inoue, Naokazu; Iwano, Megumi (7 February 2014). Sexual Reproduction in Animals and Plants. Springer. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-4-431-54589-7.

- ^ Hörandl, Elvira; Hadacek, Franz (15 August 2020). «Oxygen, life forms, and the evolution of sexes in multicellular eukaryotes». Heredity. 125 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/s41437-020-0317-9. ISSN 1365-2540. PMC 7413252. PMID 32415185.

- ^ Riley Black, «Armored Fish Pioneered Sex As You Know It,» National Geographic, October 19, 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/141019-fossil-fish-evolution-sex-fertilization Archived 23 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «43.2A: External and Internal Fertilization». Biology LibreTexts. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Tanurdzic M, Banks JA (2004). «Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants». The Plant Cell. 16 Suppl (Suppl): S61-71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- ^ Warner DA, Shine R (January 2008). «The adaptive significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in a reptile». Nature. 451 (7178): 566–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..566W. doi:10.1038/nature06519. PMID 18204437. S2CID 967516.

- ^ Beukeboom LW, Perrin N (2014). The Evolution of Sex Determination. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-965714-8.

- ^ Wallis MC, Waters PD, Graves JA (October 2008). «Sex determination in mammals—before and after the evolution of SRY». Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (20): 3182–95. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8109-z. PMID 18581056. S2CID 31675679.

- ^ Pierce, Benjamin A. (2012). Genetics: a conceptual approach (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1-4292-3250-0. OCLC 703739906.

- ^ Kaiser VB, Bachtrog D (2010). «Evolution of sex chromosomes in insects». Annual Review of Genetics. 44: 91–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163600. PMC 4105922. PMID 21047257.

- ^ Dellaporta SL, Calderon-Urrea A (October 1993). «Sex determination in flowering plants». The Plant Cell. 5 (10): 1241–51. doi:10.1105/tpc.5.10.1241. JSTOR 3869777. PMC 160357. PMID 8281039.

- ^ Fusco G, Minelli A (10 October 2019). The Biology of Reproduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-1-108-49985-9.

- ^ Smith CA, Katz M, Sinclair AH (February 2003). «DMRT1 is upregulated in the gonads during female-to-male sex reversal in ZW chicken embryos». Biology of Reproduction. 68 (2): 560–70. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.007294. PMID 12533420.

- ^ Majerus ME (2003). Sex Wars: Genes, Bacteria, and Biased Sex Ratios. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-691-00981-0.

- ^ Bull JJ (1983). Evolution of sex determining mechanisms. p. 17. ISBN 0-8053-0400-2.

- ^ Thiriot-Quiévreux C (2003). «Advances in chromosomal studies of gastropod molluscs». Journal of Molluscan Studies. 69 (3): 187–202. doi:10.1093/mollus/69.3.187.

- ^ Yoshimura A (2005). «Karyotypes of two American field crickets: Gryllus rubens and Gryllus sp. (Orthoptera: Gryllidae)». Entomological Science. 8 (3): 219–222. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8298.2005.00118.x. S2CID 84908090.

- ^ Meyer BJ (1997). «Sex Determination and X Chromosome Dosage Compensation: Sexual Dimorphism». In Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR (eds.). C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-532-3.

- ^ Handbuch Der Zoologie / Handbook of Zoology. Walter de Gruyter. 1925. ISBN 978-3-11-016210-3. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tanurdzic M, Banks JA (2004). «Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants». The Plant Cell. 16 Suppl (Suppl): S61-71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- ^ Fusco G, Minelli A (10 October 2019). The Biology of Reproduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-108-49985-9.

- ^ Todd EV, Liu H, Muncaster S, Gemmell NJ (2016). «Bending Genders: The Biology of Natural Sex Change in Fish». Sexual Development. 10 (5–6): 223–241. doi:10.1159/000449297. PMID 27820936. S2CID 41652893.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). «Environmental Sex Determination». Developmental Biology. 6th Edition.

- ^ Charlesworth B (August 2003). «Sex determination in the honeybee». Cell. 114 (4): 397–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00610-X. PMID 12941267.

- ^ de la Filia A, Bain S, Ross L (June 2015). «Haplodiploidy and the reproductive ecology of Arthropods» (PDF). Current Opinion in Insect Science. 9: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.018. hdl:20.500.11820/b540f12f-846d-4a5a-9120-7b2c45615be6. PMID 32846706. S2CID 83988416.

- ^ Fisher, R. A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 141–143 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hamilton, W. D. (1967). «Extraordinary Sex Ratios: A Sex-ratio Theory for Sex Linkage and Inbreeding Has New Implications in Cytogenetics and Entomology». Science. 156 (3774): 477–488. Bibcode:1967Sci…156..477H. doi:10.1126/science.156.3774.477. JSTOR 1721222. PMID 6021675.

- ^ Kobayashi, Kazuya; Hasegawa, Eisuke; Yamamoto, Yuuka; Kazutaka, Kawatsu; Vargo, Edward L.; Yoshimura, Jin; Matsuura, Kenji (2013). «Sex ratio biases in termites provide evidence for kin selection». Nat Commun. 4: 2048. Bibcode:2013NatCo…4.2048K. doi:10.1038/ncomms3048. PMID 23807025.

- ^ «Trend Analysis of the sex Ratio at Birth in the United States» (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ^ Davis, Devra Lee; Gottlieb, Michelle and Stampnitzky, Julie; «Reduced Ratio of Male to Female Births in Several Industrial Countries» in Journal of the American Medical Association; April 1, 1998, volume 279(13); pp. 1018-1023

- ^ «CIA Fact Book». The Central Intelligence Agency of the United States. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007.

- ^ Whitfield J (June 2004). «Everything you always wanted to know about sexes». PLOS Biology. 2 (6): e183. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020183. PMC 423151. PMID 15208728.

One thing biologists do agree on is that males and females count as different sexes. And they also agree that the main difference between the two is gamete size: males make lots of small gametes—sperm in animals, pollen in plants—and females produce a few big eggs.

- ^ Pierce BA (2012). Genetics: A Conceptual Approach. W. H. Freeman. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4292-3252-4.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2016). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-19-878860-7.

However, there is one fundamental feature of the sexes which can be used to label males as males, and females as females, throughout animals and plants. This is that the sex cells or ‘gametes’ of males are much smaller and more numerous than the gametes of females. This is true whether we are dealing with animals or plants. One group of individuals has large sex cells, and it is convenient to use the word female for them. The other group, which it is convenient to call male, has small sex cells. The difference is especially pronounced in reptiles and in birds, where a single egg cell is big enough and nutritious enough to feed a developing baby for. Even in humans, where the egg is microscopic, it is still many times larger than the sperm. As we shall see, it is possible to interpret all the other differences between the sexes as stemming from this one basic difference.

- ^ a b Mori, Emiliano; Mazza, Giuseppe; Lovari, Sandro (2017). «Sexual Dimorphism». In Vonk, Jennifer; Shackelford, Todd (eds.). Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_433-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Choe J (21 January 2019). «Body Size and Sexual Dimorphism». In Cox R (ed.). Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0-12-813252-4.

- ^ Wilkinson GS, Reillo PR (22 January 1994). «Female choice response to artificial selection on an exaggerated male trait in a stalk-eyed fly» (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 225 (1342): 1–6. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.255….1W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.2822. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0001. S2CID 5769457. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2006.

- ^ Drees BM, Jackman J (1999). «Southern black widow spider». Field Guide to Texas Insects. Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 31 August 2003. Retrieved 8 August 2012 – via Extension Entomology, Insects.tamu.edu, Texas A&M University.

- ^ Stuart-Smith J, Swain R, Stuart-Smith R, Wapstra E (2007). «Is fecundity the ultimate cause of female-biased size dimorphism in a dragon lizard?». Journal of Zoology. 273 (3): 266–272. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00324.x.

- ^ Shaw AJ (2000). «Population ecology, population genetics, and microevolution». In Shaw AJ, Goffinet B (eds.). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–380. ISBN 978-0-521-66097-6.

- ^ a b Schuster RM (1984). «Comparative Anatomy and Morphology of the Hepaticae». New Manual of Bryology. Vol. 2. Nichinan, Miyazaki, Japan: The Hattori botanical Laboratory. p. 891.

- ^ Crum HA, Anderson LE (1980). Mosses of Eastern North America. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-231-04516-2.

- ^ Briggs DA (1965). «Experimental taxonomy of some British species of genus Dicranum«. New Phytologist. 64 (3): 366–386. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1965.tb07546.x.

- ^ Zahavi A, Zahavi A (1997). The handicap principle: a missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510035-8.

- ^ Kliman, Richard (14 April 2016). Herridge, Elizabeth J; Murray, Rosalind L; Gwynne, Darryl T; Bussiere, Luc (eds.). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 453–454. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5.

- ^ Henshaw, Jonathan M.; Fromhage, Lutz; Jones, Adam G. (28 August 2019). «Sex roles and the evolution of parental care specialization». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1909): 20191312. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1312. PMC 6732396. PMID 31455191.

- ^ «Sexual Selection | Learn Science at Scitable». www.nature.com. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Reboreda, Juan Carlos; Fiorini, Vanina Dafne; Tuero, Diego Tomás (24 April 2019). Behavioral Ecology of Neotropical Birds. Springer. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-030-14280-3.

Further reading

- Arnqvist G, Rowe L (2005). Sexual conflict. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12217-5.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Ellis H (1933). Psychology of Sex. London: W. Heinemann Medical Books. N.B.: One of many books by this pioneering authority on aspects of human sexuality.

- Gilbert SF (2000). Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- Maynard-Smith J (1978). The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29302-0.

External links

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 29 December 2022, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Human Sexual Differentiation Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine by P. C. Sizonenko

Published February 13, 2019

When two words have the same meaning, we call them synonyms. When two words have different meanings but people use them interchangeably, we write articles about what those words actually mean.

Take gender and sex. While people substitute one for the other on the regular, their meaning and usage are significantly—and consequentially—different. Because we’re most often talking about human beings when we use these terms, it’s critical we get them straight. Give respect to get respect, right?

What does the word sex mean?

First, let’s talk about sex. Intercourse aside for these purposes, sex is “a label assigned at birth based on the reproductive organs you’re born with.” It’s generally how we divide society into two groups, male and female—though intersex people are born with both male and female reproductive organs. (Important note: Hermaphrodite is a term that some find offensive.)

What does gender mean?

Gender, on the other hand, goes beyond one’s reproductive organs and includes a person’s perception, understanding, and experience of themselves and roles in society. It’s their inner sense about who they’re meant to be and how they want to interact with the world.

While a person can only change their sex via surgery, one’s gender is more fluid and based on how they identify. If someone’s gender identity aligns with their biological sex, we refer to them as cisgender people.

Gender is often spoken about as a social construct, for what a society considers to be female, for example, is based on such things as beliefs and values—not nature. That women are supposed to wear dresses and that “boys don’t cry” are, ultimately, made-up social customs and conventions.

WATCH: Unteaching «Boys Will Be Boys» And «Boys Don’t Cry»

What does transgender mean?

However, one’s gender identity and sex as assigned at birth don’t always align. For example, while someone may be born with male reproductive organs and be classified as a male at birth, their gender identity may be female or something else.

We refer to these individuals as transgender people (trans- a prefix meaning “beyond” or “across”). In some cases, they may take hormones and/or undergo surgery to better sync the two; in other cases, they simply live their life as the gender they feel best represents them. Well, as simply as society lets them, which, as we know, is all too often not the case.

Use of the term transgender should be used appropriately though. Calling an individual a transgender or a trans is offensive. In other words, it should be used as an adjective, not a noun, when referring to individuals (e.g., a person who is transgender or transgender rights).

Transgender individuals may also identify as genderqueer. And, some people may have a changing experience or expression of their own gender; this can be called gender-fluid or genderflux.

Gender-neutral is best

There are also nonbinary people who don’t identify in the traditional (and many would say false) dichotomy male or female—and indeed, everyone ranging from scientists to sociologists are understanding gender as spectrum. Increasingly, countries and states within the US are offering a third box for people to check when it comes to gender on birth certificates and other documents—such as Gender X in the state of New Jersey—to accurately represent them.

More parents are also choosing to raise their children with gender-neutral upbringings, so as not to assume or influence their gender identity before they’re able to determine it for themselves. Celebrity and non-celebrity parents around the world are refusing to put their children in a gender box just because the world expects them to check one on a form. This movement is yet another reason why the use of gender-neutral pronouns, such as they, should not only be considered proper grammar but also proper behavior when referring to a nonbinary individual.

Still confused?

Sure, it’s easier to just put people into one of two neat boxes, male and female, boy and girl. But, humans are complex creatures, and it’s just not that simple.

The bottom line is that people deserve to be identified and referred to correctly and based on their preferences. Mixing you’re and your isn’t quite the same as conflating someone’s birth sex with their gender identity or referring to he/him/his when they prefer they/them/theirs. That causes pain and shows disrespect.

So, if you have a hard time remembering how to refer to anyone, anytime, you can always call them by their chosen name. There’s no synonym for that.

We get asked what sex is here at Scarleteen a lot. We also ask our users to tell us what «sex» means to them a lot, because (possibly just like you) we don’t always know what someone means when they talk about sex or having sex. People tend to use the word sex very differently , subjectively and arbitrarily: what sex is, means or has meant for one person can be radically different for someone else.

It’s obviously important if you’re here for information about sex that you know what we mean when we say (and hear or read) «sex,» so we thought we’d make it crystal clear.

What do we mean when we say «sex?»

If we say sexuality, we mean the physical, chemical, emotional and intellectual properties and processes and the cultural and social influences and experiences that are how people experience and express themselves as sexual beings. Some aspects of all those things are very diverse and unique, others are very common or collective.

If we say someone is having sex, or doing something sexual, we mean they are acting from their own sexuality, are expressing it in action or are trying to actively experience or explore a feeling of general or specific sexual desire, curiosity or satisfaction.

When we say «sex,» what we mean is any number of different things people freely choose to do to tangibly and actively express or enact their sexuality; what things people have identified and do identify as a kind of sexual experience.

If «sex» was the answer, the questions would be things like «What am I doing to try and feel good sexually or to express feeling good sexually? What am I doing that feels sexual to me (or to me and a partner)? What am I doing that feels like a way to express my sexuality, or my sexual desires and/or feelings about myself or others?»

When some people say «sex» they only mean vaginal, genital intercourse. The trouble is, there are a good many people who don’t or can’t have that kind of sex, or don’t have that kind of sex every time, but who still have active, fulfilling sexual lives. There are a LOT of different kinds of sex, and intercourse can be just one of them.

Some other people use «sex» to mean any kind of genital sex with someone else. That definition can have its flaws, though, too. When we mean those specific things, we’ll say that we’re talking about those specific things. When some people say «having sex» they mean something that can only happen in some specific kinds of partnership, but when we mean specific partnerships or relationships, we’ll be specific.

When we say «sex» we’re talking about a very big picture. That’s because what sex is or isn’t for any given person or partnership not only differs a whole lot from person-to-person, it also can differ a whole lot from day-to-day for any one person: the way they had sex yesterday may not be the way they’ll have sex next week. One person might consider that only intercourse or oral sex is sex, but someone else may both define sex differently and have what’s sex for them without doing either of those things. And defining what sex is just by a given activity or action, without talking about people’s motivations and desires really doesn’t work: after all, rape isn’t sex, even though things like intercourse or oral sex are forced in rapes.

What can «sex» be?

- Masturbation (doing some of the things on the list below with oneself, not a partner)

- Kissing/Making out

- Petting/Stroking/Sexual massage

- Breast or nipple stimulation

- Frottage or tribbing (rubbing against genitals or rubbing genitals together, when clothed, called «dry sex»)

- Mutual masturbation (masturbating with a partner)

- Manual-genital sex (like handjobs, fingering or deep manual sex, which some people call «fisting»)

- Oral-genital sex (to/with a penis, vulva, anus)

- Vaginal intercourse

- Sex toy-vagina or sex toy-penis sexual intercourse

- Anal sex (like anal intercourse with a penis, toy or hands)

- Talking in a sexual way/sharing sexual fantasies/sexual role-play

- Sensation play, like pinching, touching someone with objects in some way or spanking (which may or may not be part of BDSM)

- Cybersex, text sex or phone sex (with or without masturbation)

- Fluid-play (when people do things with body fluids for sexual enjoyment, like ejaculating on someone in a particular way)

- …or something else entirely.

Some of those activities or practices are things people can do alone, others require another person or a sex toy. Some people who do any of those things with partners do them with one partner at a time; others with more than one partner at a time. They don’t all require that individuals or their partners are a certain gender, or that a person’s body looks or acts a given way or has a certain set of abilities. Some people have enjoyed or later in life will enjoy all of those things, some people absolutely none, but most people have enjoyed or will enjoy some. Which of them people enjoy is highly individual and isn’t based on a person’s gender, sexual orientation, age, shape or size, race, character, religion or anything else like that.

In every healthy relationship (including with oneself!), all of those activities are optional. None are required.

In case it isn’t obvious, there are some overlaps in that list: like, oral sex that involves an anus is a kind of anal sex. There are also some potential places where one activity kind of collides with or can blend into another (should people choose to do so), like if two people are engaging in frottage where one has a penis and the other a vulva, and they choose to turn that into genital intercourse. As well, there is no one way to do any of these activities «right» or «wrong» or to be «good» or «bad» at them: all can be done and enjoyed (or not) in a vast variety of ways, differing from person-to-person, partnership-to-partnership, day-to-day or even from minute-to-minute.

At Scarleteen, we don’t consider rape or other sexual abuse to be sex: when we’re talking about sex, we’re talking about consensual sex (sex everyone involved wants, freely chooses and agrees to do and actively participates in), where when there is more than one person involved, what’s going on is sex for both people, and wanted by both people, not just one. While for some people who rape, it is sex for them, it is not sex for the person or people they are raping or have raped.

Part of that is the understanding that just doing a given thing, or having it done to you, doesn’t mean something is automatically sex for everyone. Whether or not it’s sex depends on if it is motivated by/about sexuality for everyone involved, not just one person. There may be times that something you think of as being sex in one situation isn’t in another at all. Rape is one example of that. For another example, if someone chooses to have sex with a partner that involves fingers being inside her vagina, that doesn’t make that same action sex when she is at the gynecologists office getting an exam, something she doesn’t find to be sexual at all or have any sexual motivation for. Just because kissing was part of sex with your girlfriend yesterday doesn’t mean it’s sex when you kiss your Great-Aunt Ida at a family dinner tonight.

P.S. Sometimes when we say sex, we’re using it in a whole different way altogether, which is when we are talking about the way people are assigned or possess a biological or anatomical sex, such as male, female or intersex. For more on that, see the link on gender below.

What else?

- What’s gender?

- What’s sexual anatomy?

- What’s masturbation?

- What’s a sex drive?

- What’s foreplay?

- What’s a relationship?

- What’s it mean to be ready for sex?

- What’s virginity?

- What’s sexual abuse or rape?

Latin had a word sex, but it didn’t have the same meaning as in English. Instead, it’s cognate with English «six», and means the same thing.

English «sex» comes from Latin sexus, -ūs, which comes from a root sec- meaning «cut» (compare section, dissect, segment). The original meaning was «division», which shifted to «a way of dividing something in half», and thus to «the division between men and women; biological sex». That’s the meaning it had in Classical Latin.

This led to an adjective sexuālis, -is, -e, «pertaining to the sexes», as in «sexual dimorphism», «sexual reproduction», etc. This adjective got associated with sex in the modern sense through phrases like «sexual intercourse».

Over time this got shortened just to «sex», as a noun meaning the physical act, and then that turned into a verb. But these were purely post-Latin developments. In Latin, sexus means «sex» as in the male/female binary, nothing more.

What does Sex Mean?

Definitions

Definition as Noun

- either of the two categories (male or female) into which most organisms are divided

- the properties that distinguish organisms on the basis of their reproductive roles

- activities associated with sexual intercourse

- all of the feelings resulting from the urge to gratify sexual impulses

Definition as Verb

- tell the sex (of young chickens)

- stimulate sexually

Examples

- «the war between the sexes»

- «she didn’t want to know the sex of the foetus»

- «they had sex in the back seat»

- «he wanted a better sex life»; «the film contained no sex or violence»

- «This movie usually arouses the male audience»

Part of Speech

Comparisons

- Sex vs gender

- Sex vs sexuality

- Sex vs sexual activity

- Sex vs sexual practice

- Sex vs sex activity

- Sex vs sexual urge

- Sex vs arouse

- Sex vs excite

- Sex vs turn on

- Sex vs wind up

See also

The word ‘sex’ in common usage is slang for ‘sexual intercourse’; used formally, the word refers to gender. Thus a doctor might ask a newly-pregnant woman for the date she last had sex (meaning sexual intercourse) in order to judge the age of the fetus, and then later he might ask her if she wants to know the sex (meaning gender) of her child when he looks at the ultrasound.

Something good and make you feel comfortable And good

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What does the word sex mean?

Write your answer…

Still have questions?

Continue Learning about English Language Arts