Philosophy (from Greek: φιλοσοφία, philosophia, ‘love of wisdom’)[1][2] is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language.[3][4][5][6][7] Some sources claim the term was coined by Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE),[8][9] although this theory is disputed by some.[10][11][12] Philosophical methods include questioning, critical discussion, rational argument, and systematic presentation.[13][14][i]

Historically, philosophy encompassed all bodies of knowledge and a practitioner was known as a philosopher.[15] «Natural philosophy», which began as a discipline in ancient India and Ancient Greece, encompasses astronomy, medicine, and physics.[16][17] For example, Isaac Newton’s 1687 Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy later became classified as a book of physics. In the 19th century, the growth of modern research universities led academic philosophy and other disciplines to professionalize and specialize.[18][19] Since then, various areas of investigation that were traditionally part of philosophy have become separate academic disciplines, and namely the social sciences such as psychology, sociology, linguistics, and economics.

Today, major subfields of academic philosophy include metaphysics, which is concerned with the fundamental nature of existence and reality; epistemology, which studies the nature of knowledge and belief; ethics, which is concerned with moral value; and logic, which studies the rules of inference that allow one to derive conclusions from true premises.[20][21] Other notable subfields include philosophy of religion, philosophy of science, political philosophy, aesthetics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of mind.

Definitions

There is wide agreement that philosophy (from the ancient Greek φίλος, phílos: «love»; and σοφία, sophía: «wisdom»)[22] is characterized by various general features: it is a form of rational inquiry, it aims to be systematic, and it tends to critically reflect on its own methods and presuppositions.[23][24][25] But approaches that go beyond such vague characterizations to give a more interesting or profound definition are usually controversial.[24][25] Often, they are only accepted by theorists belonging to a certain philosophical movement and are revisionistic in that many presumed parts of philosophy would not deserve the title «philosophy» if they were true.[26][27] Before the modern age, the term was used in a very wide sense, which included the individual sciences, like physics or mathematics, as its sub-disciplines, but the contemporary usage is more narrow.[25][28][29]

Some approaches argue that there is a set of essential features shared by all parts of philosophy while others see only weaker family resemblances or contend that it is merely an empty blanket term.[30][27][31] Some definitions characterize philosophy in relation to its method, like pure reasoning. Others focus more on its topic, for example, as the study of the biggest patterns of the world as a whole or as the attempt to answer the big questions.[27][32][33] Both approaches have the problem that they are usually either too wide, by including non-philosophical disciplines, or too narrow, by excluding some philosophical sub-disciplines.[27] Many definitions of philosophy emphasize its intimate relation to science.[25] In this sense, philosophy is sometimes understood as a proper science in its own right. Some naturalist approaches, for example, see philosophy as an empirical yet very abstract science that is concerned with very wide-ranging empirical patterns instead of particular observations.[27][34] Some phenomenologists, on the other hand, characterize philosophy as the science of essences.[26][35][36] Science-based definitions usually face the problem of explaining why philosophy in its long history has not made the type of progress as seen in other sciences.[27][37][38] This problem is avoided by seeing philosophy as an immature or provisional science whose subdisciplines cease to be philosophy once they have fully developed.[25][30][35] In this sense, philosophy is the midwife of the sciences.[25]

Other definitions focus more on the contrast between science and philosophy. A common theme among many such definitions is that philosophy is concerned with meaning, understanding, or the clarification of language.[32][27] According to one view, philosophy is conceptual analysis, which involves finding the necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of concepts.[33][27][39] Another defines philosophy as a linguistic therapy that aims at dispelling misunderstandings to which humans are susceptible due to the confusing structure of natural language.[26][25][40] One more approach holds that the main task of philosophy is to articulate the pre-ontological understanding of the world, which acts as a condition of possibility of experience.[27][41][42]

Many other definitions of philosophy do not clearly fall into any of the aforementioned categories. An early approach already found in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy is that philosophy is the spiritual practice of developing one’s reasoning ability.[43][44] This practice is an expression of the philosopher’s love of wisdom and has the aim of improving one’s well-being by leading a reflective life.[45] A closely related approach identifies the development and articulation of worldviews as the principal task of philosophy, i.e. to express how things on the grand scale hang together and which practical stance we should take towards them.[27][23][46] Another definition characterizes philosophy as thinking about thinking in order to emphasize its reflective nature.[27][33]

Historical overview

In one general sense, philosophy is associated with wisdom, intellectual culture, and a search for knowledge. In this sense, all cultures and literate societies ask philosophical questions, such as «how are we to live» and «what is the nature of reality». A broad and impartial conception of philosophy, then, finds a reasoned inquiry into such matters as reality, morality, and life in all world civilizations.[47]

Western philosophy

Statue of Aristotle (384–322 BCE), a major figure of ancient Greek philosophy, in Aristotle’s Park, Stagira

Western philosophy is the philosophical tradition of the Western world, dating back to pre-Socratic thinkers who were active in 6th-century Greece (BCE), such as Thales (c. 624 – c. 545 BCE) and Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE) who practiced a «love of wisdom» (Latin: philosophia)[48] and were also termed «students of nature» (physiologoi).

Western philosophy can be divided into three eras:

- Ancient (Greco-Roman).

- Medieval philosophy (referring to Christian European thought).

- Modern philosophy (beginning in the 17th century).

Ancient era

While our knowledge of the ancient era begins with Thales in the 6th century BCE, little is known about the philosophers who came before Socrates (commonly known as the pre-Socratics). The ancient era was dominated by Greek philosophical schools. Most notable among the schools influenced by Socrates’ teachings were Plato, who founded the Platonic Academy, and his student Aristotle, who founded the Peripatetic school.[49] Other ancient philosophical traditions influenced by Socrates included Cynicism, Cyrenaicism, Stoicism, and Academic Skepticism. Two other traditions were influenced by Socrates’ contemporary, Democritus: Pyrrhonism and Epicureanism. Important topics covered by the Greeks included metaphysics (with competing theories such as atomism and monism), cosmology, the nature of the well-lived life (eudaimonia), the possibility of knowledge, and the nature of reason (logos). With the rise of the Roman empire, Greek philosophy was increasingly discussed in Latin by Romans such as Cicero and Seneca (see Roman philosophy).[50]

Medieval era

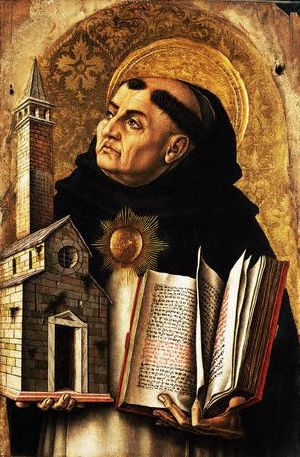

Medieval philosophy (5th–16th centuries) took place during the period following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and was dominated by the rise of Christianity; it hence reflects Judeo-Christian theological concerns while also retaining a continuity with Greco-Roman thought. Problems such as the existence and nature of God, the nature of faith and reason, metaphysics, and the problem of evil were discussed in this period. Some key medieval thinkers include Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Boethius, Anselm and Roger Bacon. Philosophy for these thinkers was viewed as an aid to theology (ancilla theologiae), and hence they sought to align their philosophy with their interpretation of sacred scripture. This period saw the development of scholasticism, a text critical method developed in medieval universities based on close reading and disputation on key texts. The Renaissance period saw increasing focus on classic Greco-Roman thought and on a robust humanism.[51]

Modern era

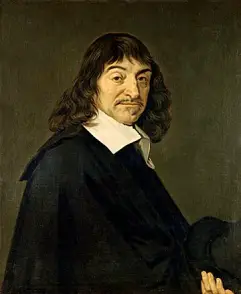

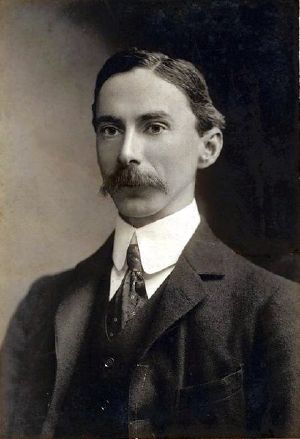

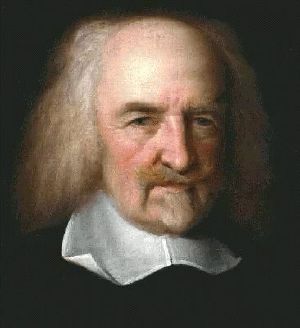

Early modern philosophy in the Western world begins with thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes (1596–1650).[52] Following the rise of natural science, modern philosophy was concerned with developing a secular and rational foundation for knowledge and moved away from traditional structures of authority such as religion, scholastic thought and the Church. Major modern philosophers include Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant.

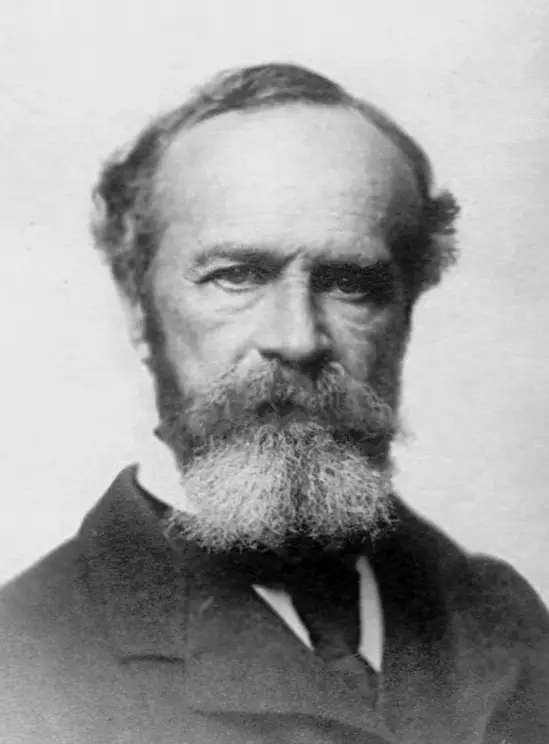

19th-century philosophy (sometimes called late modern philosophy) was influenced by the wider 18th-century movement termed «the Enlightenment», and includes figures such as Hegel, a key figure in German idealism; Kierkegaard, who developed the foundations for existentialism; Thomas Carlyle, representative of the great man theory; Nietzsche, a famed anti-Christian; John Stuart Mill, who promoted utilitarianism; Karl Marx, who developed the foundations for communism; and the American William James. The 20th century saw the split between analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, as well as philosophical trends such as phenomenology, existentialism, logical positivism, pragmatism and the linguistic turn (see Contemporary philosophy).[53]

Middle Eastern philosophy

Pre-Islamic philosophy

The regions of the Fertile Crescent, Iran and Arabia are home to the earliest known philosophical wisdom literature.[citation needed]

According to the assyriologist Marc Van de Mieroop, Babylonian philosophy was a highly developed system of thought with a unique approach to knowledge and a focus on writing, lexicography, divination, and law.[54] It was also a bilingual intellectual culture, based on Sumerian and Akkadian.[55]

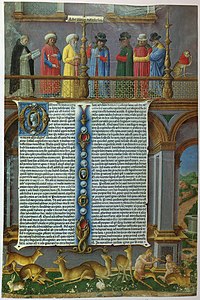

A page of The Maxims of Ptahhotep, traditionally attributed to the Vizier Ptahhotep (c. 2375–2350 BCE)

Early Wisdom literature from the Fertile Crescent was a genre that sought to instruct people on ethical action, practical living, and virtue through stories and proverbs. In Ancient Egypt, these texts were known as sebayt (‘teachings’), and they are central to our understandings of Ancient Egyptian philosophy. The most well known of these texts is The Maxims of Ptahhotep.[56] Theology and cosmology were central concerns in Egyptian thought. Perhaps the earliest form of a monotheistic theology also emerged in Egypt, with the rise of the Amarna theology (or Atenism) of Akhenaten (14th century BCE), which held that the solar creation deity Aten was the only god. This has been described as a «monotheistic revolution» by egyptologist Jan Assmann, though it also drew on previous developments in Egyptian thought, particularly the «New Solar Theology» based around Amun-Ra.[57][58] These theological developments also influenced the post-Amarna Ramesside theology, which retained a focus on a single creative solar deity (though without outright rejection of other gods, which are now seen as manifestations of the main solar deity). This period also saw the development of the concept of the ba (soul) and its relation to god.[58]

Jewish philosophy and Christian philosophy are religious-philosophical traditions that developed both in the Middle East and in Europe, which both share certain early Judaic texts (mainly the Tanakh) and monotheistic beliefs. Jewish thinkers such as the Geonim of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia and Maimonides engaged with Greek and Islamic philosophy. Later Jewish philosophy came under strong Western intellectual influences and includes the works of Moses Mendelssohn who ushered in the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment), Jewish existentialism, and Reform Judaism.[59][60]

The various traditions of Gnosticism, which were influenced by both Greek and Abrahamic currents, originated around the first century and emphasized spiritual knowledge (gnosis).[61]

Pre-Islamic Iranian philosophy begins with the work of Zoroaster, one of the first promoters of monotheism and of the dualism between good and evil.[62] This dualistic cosmogony influenced later Iranian developments such as Manichaeism, Mazdakism, and Zurvanism.[63][64]

Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is the philosophical work originating in the Islamic tradition and is mostly done in Arabic. It draws from the religion of Islam as well as from Greco-Roman philosophy. After the Muslim conquests, the translation movement (mid-eighth to the late tenth century) resulted in the works of Greek philosophy becoming available in Arabic.[65]

Early Islamic philosophy developed the Greek philosophical traditions in new innovative directions. This intellectual work inaugurated what is known as the Islamic Golden Age. The two main currents of early Islamic thought are Kalam, which focuses on Islamic theology, and Falsafa, which was based on Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism. The work of Aristotle was very influential among philosophers such as Al-Kindi (9th century), Avicenna (980 – June 1037), and Averroes (12th century). Others such as Al-Ghazali were highly critical of the methods of the Islamic Aristotelians and saw their metaphysical ideas as heretical. Islamic thinkers like Ibn al-Haytham and Al-Biruni also developed a scientific method, experimental medicine, a theory of optics, and a legal philosophy. Ibn Khaldun was an influential thinker in philosophy of history.

Islamic thought also deeply influenced European intellectual developments, especially through the commentaries of Averroes on Aristotle. The Mongol invasions and the destruction of Baghdad in 1258 are often seen as marking the end of the Golden Age.[66] Several schools of Islamic philosophy continued to flourish after the Golden Age, however, and include currents such as Illuminationist philosophy, Sufi philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy.

The 19th- and 20th-century Arab world saw the Nahda movement (literally meaning ‘The Awakening’; also known as the ‘Arab Renaissance’), which had a considerable influence on contemporary Islamic philosophy.

Eastern philosophy

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy (Sanskrit: darśana, lit. ‘point of view’, ‘perspective’)[69] refers to the diverse philosophical traditions that emerged since the ancient times on the Indian subcontinent. Indian philosophy chiefly considers epistemology, theories of consciousness and theories of mind, and the physical properties of reality. [70] [71] [72] Indian philosophical traditions share various key concepts and ideas, which are defined in different ways and accepted or rejected by the different traditions. These include concepts such as dhárma, karma, pramāṇa, duḥkha, saṃsāra and mokṣa.[73][74]

Some of the earliest surviving Indian philosophical texts are the Upanishads of the later Vedic period (1000–500 BCE), which are considered to preserve the ideas of Brahmanism. Indian philosophical traditions are commonly grouped according to their relationship to the Vedas and the ideas contained in them. Jainism and Buddhism originated at the end of the Vedic period, while the various traditions grouped under Hinduism mostly emerged after the Vedic period as independent traditions. Hindus generally classify Indian philosophical traditions as either orthodox (āstika) or heterodox (nāstika) depending on whether they accept the authority of the Vedas and the theories of brahman and ātman found therein.[75][76]

The schools which align themselves with the thought of the Upanishads, the so-called «orthodox» or «Hindu» traditions, are often classified into six darśanas or philosophies:Sānkhya, Yoga, Nyāya, Vaisheshika, Mimāmsā and Vedānta.[77]

The doctrines of the Vedas and Upanishads were interpreted differently by these six schools of Hindu philosophy, with varying degrees of overlap. They represent a «collection of philosophical views that share a textual connection», according to Chadha (2015).[78] They also reflect a tolerance for a diversity of philosophical interpretations within Hinduism while sharing the same foundation.[ii]

Hindu philosophers of the six orthodox schools developed systems of epistemology (pramana) and investigated topics such as metaphysics, ethics, psychology (guṇa), hermeneutics, and soteriology within the framework of the Vedic knowledge, while presenting a diverse collection of interpretations.[79][80][81][82] The commonly named six orthodox schools were the competing philosophical traditions of what has been called the «Hindu synthesis» of classical Hinduism.[83][84]

[85]

There are also other schools of thought which are often seen as «Hindu», though not necessarily orthodox (since they may accept different scriptures as normative, such as the Shaiva Agamas and Tantras), these include different schools of Shavism such as Pashupata, Shaiva Siddhanta, non-dual tantric Shavism (i.e. Trika, Kaula, etc.).[86]

The parable of the blind men and the elephant illustrates the important Jain doctrine of anēkāntavāda.

The «Hindu» and «Orthodox» traditions are often contrasted with the «unorthodox» traditions (nāstika, literally «those who reject»), though this is a label that is not used by the «unorthodox» schools themselves. These traditions reject the Vedas as authoritative and often reject major concepts and ideas that are widely accepted by the orthodox schools (such as Ātman, Brahman, and Īśvara).[87] These unorthodox schools include Jainism (accepts ātman but rejects Īśvara, Vedas and Brahman), Buddhism (rejects all orthodox concepts except rebirth and karma), Cārvāka (materialists who reject even rebirth and karma) and Ājīvika (known for their doctrine of fate).[87][88][89]<[90][91][iii][92][93]

Jain philosophy is one of the only two surviving «unorthodox» traditions (along with Buddhism). It generally accepts the concept of a permanent soul (jiva) as one of the five astikayas (eternal, infinite categories that make up the substance of existence). The other four being dhárma, adharma, ākāśa (‘space’), and pudgala (‘matter’). Jain thought holds that all existence is cyclic, eternal and uncreated.[94][95]

Some of the most important elements of Jain philosophy are the Jain theory of karma, the doctrine of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and the theory of «many-sidedness» or Anēkāntavāda. The Tattvartha Sutra is the earliest known, most comprehensive and authoritative compilation of Jain philosophy.[96][97]

Major European Quantum Physicists, including Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Albert Einstein, & Niels Bohr credit the Vedas with giving them the ideas for their experiments. [98]

Buddhist philosophy

Monks debating at Sera monastery, Tibet, 2013. According to Jan Westerhoff, «public debates constituted the most important and most visible forms of philosophical exchange» in ancient Indian intellectual life.[99]

Buddhist philosophy begins with the thought of Gautama Buddha (fl. between 6th and 4th century BCE) and is preserved in the early Buddhist texts. It originated in the Indian region of Magadha and later spread to the rest of the Indian subcontinent, East Asia, Tibet, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. In these regions, Buddhist thought developed into different philosophical traditions which used various languages (like Tibetan, Chinese and Pali). As such, Buddhist philosophy is a trans-cultural and international phenomenon.

The dominant Buddhist philosophical traditions in East Asian nations are mainly based on Indian Mahayana Buddhism. The philosophy of the Theravada school is dominant in Southeast Asian countries like Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand.

Because ignorance to the true nature of things is considered one of the roots of suffering (dukkha), Buddhist philosophy is concerned with epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and psychology. Buddhist philosophical texts must also be understood within the context of meditative practices which are supposed to bring about certain cognitive shifts.[100] Key innovative concepts include the Four Noble Truths as an analysis of dukkha, anicca (impermanence), and anatta (non-self).[iv][101]

After the death of the Buddha, various groups began to systematize his main teachings, eventually developing comprehensive philosophical systems termed Abhidharma.[102] Following the Abhidharma schools, Indian Mahayana philosophers such as Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu developed the theories of śūnyatā (’emptiness of all phenomena’) and vijñapti-matra (‘appearance only’), a form of phenomenology or transcendental idealism. The Dignāga school of pramāṇa (‘means of knowledge’) promoted a sophisticated form of Buddhist epistemology.

There were numerous schools, sub-schools, and traditions of Buddhist philosophy in ancient and medieval India. According to Oxford professor of Buddhist philosophy Jan Westerhoff, the major Indian schools from 300 BCE to 1000 CE were:[103] the Mahāsāṃghika tradition (now extinct), the Sthavira schools (such as Sarvāstivāda, Vibhajyavāda and Pudgalavāda) and the Mahayana schools. Many of these traditions were also studied in other regions, like Central Asia and China, having been brought there by Buddhist missionaries.

After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the Tibetan Buddhist, East Asian Buddhist and Theravada Buddhist traditions.[104][105]

East Asian philosophy

East Asian philosophical thought began in Ancient China, and Chinese philosophy begins during the Western Zhou Dynasty and the following periods after its fall when the «Hundred Schools of Thought» flourished (6th century to 221 BCE).[106][107] This period was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments and saw the rise of the major philosophical schools of China such as Confucianism (also known as Ruism), Legalism, and Taoism as well as numerous other less influential schools like Mohism and Naturalism. These philosophical traditions developed metaphysical, political and ethical theories such Tao, Yin and yang, Ren and Li.

These schools of thought further developed during the Han (206 BCE – 220 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) eras, forming new philosophical movements like Xuanxue (also called Neo-Taoism), and Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism was a syncretic philosophy, which incorporated the ideas of different Chinese philosophical traditions, including Buddhism and Taoism. Neo-Confucianism came to dominate the education system during the Song dynasty (960–1297), and its ideas served as the philosophical basis of the imperial exams for the scholar official class. Some of the most important Neo-Confucian thinkers are the Tang scholars Han Yu and Li Ao as well as the Song thinkers Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200). Zhu Xi compiled the Confucian canon, which consists of the Four Books (the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius). The Ming scholar Wang Yangming (1472–1529) is a later but important philosopher of this tradition as well.

Buddhism began arriving in China during the Han Dynasty, through a gradual Silk road transmission,[108] and through native influences developed distinct Chinese forms (such as Chan/Zen) which spread throughout the East Asian cultural sphere.

Chinese culture was highly influential on the traditions of other East Asian states, and its philosophy directly influenced Korean philosophy, Vietnamese philosophy and Japanese philosophy.[109] During later Chinese dynasties like the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), as well as in the Korean Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), a resurgent Neo-Confucianism led by thinkers such as Wang Yangming (1472–1529) became the dominant school of thought and was promoted by the imperial state. In Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) was also strongly influenced by Confucian philosophy.[110] Confucianism continues to influence the ideas and worldview of the nations of the Chinese cultural sphere today.

In the Modern era, Chinese thinkers incorporated ideas from Western philosophy. Chinese Marxist philosophy developed under the influence of Mao Zedong, while a Chinese pragmatism developed under Hu Shih. The old traditional philosophies also began to reassert themselves in the 20th century. For example, New Confucianism, led by figures such as Xiong Shili, has become quite influential. Likewise, Humanistic Buddhism is a recent modernist Buddhist movement.

Modern Japanese thought meanwhile developed under strong Western influences such as the study of Western Sciences (Rangaku) and the modernist Meirokusha intellectual society, which drew from European enlightenment thought and promoted liberal reforms as well as Western philosophies like Liberalism and Utilitarianism. Another trend in modern Japanese philosophy was the «National Studies» (Kokugaku) tradition. This intellectual trend sought to study and promote ancient Japanese thought and culture. Kokugaku thinkers such as Motoori Norinaga sought to return to a pure Japanese tradition which they called Shinto that they saw as untainted by foreign elements.

During the 20th century, the Kyoto School, an influential and unique Japanese philosophical school, developed from Western phenomenology and Medieval Japanese Buddhist philosophy such as that of Dogen.

African philosophy

Painting of Zera Yacob from Claude Sumner’s Classical Ethiopian Philosophy

African philosophy is philosophy produced by African people, philosophy that presents African worldviews, ideas and themes, or philosophy that uses distinct African philosophical methods. Modern African thought has been occupied with Ethnophilosophy, that is, defining the very meaning of African philosophy and its unique characteristics and what it means to be African.[111]

During the 17th century, Ethiopian philosophy developed a robust literary tradition as exemplified by Zera Yacob. Another early African philosopher was Anton Wilhelm Amo (c. 1703–1759) who became a respected philosopher in Germany. Distinct African philosophical ideas include Ujamaa, the Bantu idea of ‘Force’, Négritude, Pan-Africanism and Ubuntu. Contemporary African thought has also seen the development of Professional philosophy and of Africana philosophy, the philosophical literature of the African diaspora which includes currents such as black existentialism by African-Americans. Some modern African thinkers have been influenced by Marxism, African-American literature, Critical theory, Critical race theory, Postcolonialism and Feminism.

Indigenous American philosophy

Indigenous-American philosophical thought consists of a wide variety of beliefs and traditions among different American cultures. Among some of U.S. Native American communities, there is a belief in a metaphysical principle called the ‘Great Spirit’ (Siouan: wakȟáŋ tȟáŋka; Algonquian: gitche manitou). Another widely shared concept was that of orenda (‘spiritual power’). According to Whiteley (1998), for the Native Americans, «mind is critically informed by transcendental experience (dreams, visions and so on) as well as by reason.»[112] The practices to access these transcendental experiences are termed shamanism. Another feature of the indigenous American worldviews was their extension of ethics to non-human animals and plants.[112][113]

In Mesoamerica, Nahua philosophy was an intellectual tradition developed by individuals called tlamatini (‘those who know something’)[114] and its ideas are preserved in various Aztec codices and fragmentary texts. Some of these philosophers are known by name, such as Nezahualcoyotl, Aquiauhtzin, Xayacamach, Tochihuitzin coyolchiuhqui and Cuauhtencoztli.[115][116] These authors were also poets and some of their work has survived in the original Nahuatl.[115][116]

Aztec philosophers developed theories of metaphysics, epistemology, values, and aesthetics. Aztec ethics was focused on seeking tlamatiliztli (‘knowledge’, ‘wisdom’) which was based on moderation and balance in all actions as in the Nahua proverb «the middle good is necessary».[117] The Nahua worldview posited the concept of an ultimate universal energy or force called Ōmeteōtl (‘Dual Cosmic Energy’) which sought a way to live in balance with a constantly changing, «slippery» world. The theory of Teotl can be seen as a form of Pantheism.[117] According to James Maffie, Nahua metaphysics posited that teotl is «a single, vital, dynamic, vivifying, eternally self-generating and self-conceiving as well as self-regenerating and self-reconceiving sacred energy or force».[116] This force was seen as the all-encompassing life force of the universe and as the universe itself.[116]

The Inca civilization also had an elite class of philosopher-scholars termed the amawtakuna or amautas who were important in the Inca education system as teachers of philosophy, theology, astronomy, poetry, law, music, morality and history.[118][119] Young Inca nobles were educated in these disciplines at the state college of Yacha-huasi in Cuzco, where they also learned the art of the quipu.[118] Incan philosophy (as well as the broader category of Andean thought) held that the universe is animated by a single dynamic life force (sometimes termed camaquen or camac, as well as upani and amaya).[120] This singular force also arises as a set of dual complementary yet opposite forces.[120] These «complementary opposites» are called yanantin and masintin. They are expressed as various polarities or dualities (such as male–female, dark–light, life and death, above and below) which interdependently contribute to the harmonious whole that is the universe through the process of reciprocity and mutual exchange called ayni.[121][120] The Inca worldview also included the belief in a creator God (Viracocha) and reincarnation.[119]

Branches of philosophy

Philosophical questions can be grouped into various branches. These groupings allow philosophers to focus on a set of similar topics and interact with other thinkers who are interested in the same questions.

These divisions are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. (A philosopher might specialize in Kantian epistemology, or Platonic aesthetics, or modern political philosophy). Furthermore, these philosophical inquiries sometimes overlap with each other and with other inquiries such as science, religion or mathematics.[122]

Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the «critical reflection on art, culture and nature».[123][124] It addresses the nature of art, beauty and taste, enjoyment, emotional values, perception and the creation and appreciation of beauty.[125] It is more precisely defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste.[126] Its major divisions are art theory, literary theory, film theory and music theory. An example from art theory is to discern the set of principles underlying the work of a particular artist or artistic movement such as the Cubist aesthetic.[127]

Ethics

«The utilitarian doctrine is, that happiness is desirable, and the only thing desirable, as an end; all other things being only desirable as means to that end.» — John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (1863)[128]

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, studies what constitutes good and bad conduct, right and wrong values, and good and evil. Its primary investigations include exploring how to live a good life and identifying standards of morality. It also includes investigating whether there is a best way to live or a universal moral standard, and if so, how we come to learn about it. The main branches of ethics are normative ethics, meta-ethics and applied ethics.[129]

The three main views in ethics about what constitute moral actions are:[129]

- Consequentialism, which judges actions based on their consequences.[130] One such view is utilitarianism, which judges actions based on the net happiness (or pleasure) and/or lack of suffering (or pain) that they produce.

- Deontology, which judges actions based on whether they are in accordance with one’s moral duty.[130] In the standard form defended by Immanuel Kant, deontology is concerned with whether a choice respects the moral agency of other people, regardless of its consequences.[130]

- Virtue ethics, which judges actions based on the moral character of the agent who performs them and whether they conform to what an ideally virtuous agent would do.[130]

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies knowledge.[131] Epistemologists examine putative sources of knowledge, including perceptual experience, reason, memory, and testimony. They also investigate questions about the nature of truth, belief, justification, and rationality.[132]

Philosophical skepticism, which raises doubts about some or all claims to knowledge, has been a topic of interest throughout the history of philosophy. It arose early in Pre-Socratic philosophy and became formalized with Pyrrho, the founder of the earliest Western school of philosophical skepticism. It features prominently in the works of modern philosophers René Descartes and David Hume and has remained a central topic in contemporary epistemological debates.[132]

One of the most notable epistemological debates is between empiricism and rationalism.[133] Empiricism places emphasis on observational evidence via sensory experience as the source of knowledge.[133] Empiricism is associated with a posteriori knowledge, which is obtained through experience (such as scientific knowledge).[133] Rationalism places emphasis on reason as a source of knowledge.[133] Rationalism is associated with a priori knowledge, which is independent of experience (such as logic and mathematics).

One central debate in contemporary epistemology is about the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, which might include truth and justification. This debate was largely the result of attempts to solve the Gettier problem.[132] Another common subject of contemporary debates is the regress problem, which occurs when trying to offer proof or justification for any belief, statement, or proposition. The problem is that whatever the source of justification may be, that source must either be without justification (in which case it must be treated as an arbitrary foundation for belief), or it must have some further justification (in which case justification must either be the result of circular reasoning, as in coherentism, or the result of an infinite regress, as in infinitism).[132]

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, such as existence, time, objects and their properties, wholes and their parts, events, processes and causation and the relationship between mind and body.[134] Metaphysics includes cosmology, the study of the world in its entirety and ontology, the study of being, along with the philosophy of space and time.

A major point of debate is between realism, which holds that there are entities that exist independently of their mental perception, and idealism, which holds that reality is mentally constructed or otherwise immaterial. Metaphysics deals with the topic of identity. Essence is the set of attributes that make an object what it fundamentally is and without which it loses its identity, while accident is a property that the object has, without which the object can still retain its identity. Particulars are objects that are said to exist in space and time, as opposed to abstract objects, such as numbers, and universals, which are properties held by multiple particulars, such as redness or a gender. The type of existence, if any, of universals and abstract objects is an issue of debate.

Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and argument.

Deductive reasoning is when, given certain premises, conclusions are unavoidably implied.[135] Rules of inference are used to infer conclusions such as, modus ponens, where given «A» and «If A then B», then «B» must be concluded.

Because sound reasoning is an essential element of all sciences,[136] social sciences and humanities disciplines, logic became a formal science. Sub-fields include mathematical logic, philosophical logic, modal logic, computational logic and non-classical logics. A major question in the philosophy of mathematics is whether mathematical entities are objective and discovered, called mathematical realism, or invented, called mathematical antirealism.

Mind and language

Philosophy of language explores the nature, origins, and use of language. Philosophy of mind explores the nature of the mind and its relationship to the body, as typified by disputes between materialism and dualism. In recent years, this branch has become related to cognitive science.

Philosophy of science

The philosophy of science explores the foundations, methods, history, implications and purpose of science. Many of its subdivisions correspond to specific branches of science. For example, philosophy of biology deals specifically with the metaphysical, epistemological and ethical issues in the biomedical and life sciences.

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of government and the relationship of individuals (or families and clans) to communities including the state. It includes questions about justice, law, property and the rights and obligations of the citizen. Political philosophy, ethics, and aesthetics are traditionally linked subjects, under the general heading of value theory as they involve a normative or evaluative aspect.[137]

Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion deals with questions that involve religion and religious ideas from a philosophically neutral perspective (as opposed to theology which begins from religious convictions).[138] Traditionally, religious questions were not seen as a separate field from philosophy proper, and the idea of a separate field only arose in the 19th century.[v]

Issues include the existence of God, the relationship between reason and faith, questions of religious epistemology, the relationship between religion and science, how to interpret religious experiences, questions about the possibility of an afterlife, the problem of religious language and the existence of souls and responses to religious pluralism and diversity.

Metaphilosophy

Metaphilosophy explores the aims, boundaries and methods of philosophy. It is debated as to whether metaphilosophy is a subject that comes prior to philosophy[139] or whether it is inherently part of philosophy.[140]

Other subdivisions

In section thirteen of his Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, the oldest surviving history of philosophy (3rd century), Diogenes Laërtius presents a three-part division of ancient Greek philosophical inquiry:[141]

- Natural philosophy (i.e. physics, from Greek: ta physika, lit. ‘things having to do with physis [nature]’) was the study of the constitution and processes of transformation in the physical world.[142]

- Moral philosophy (i.e. ethics, from êthika, ‘having to do with character, disposition, manners’) was the study of goodness, right and wrong, justice and virtue.[143]

- Metaphysical philosophy (i.e. logic, from logikós, ‘of or pertaining to reason or speech’) was the study of existence, causation, God, logic, forms, and other abstract objects. (meta ta physika, ‘after the Physics‘)

In Against the Logicians the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus detailed the variety of ways in which the ancient Greek philosophers had divided philosophy, noting that this three-part division was agreed to by Plato, Aristotle, Xenocrates, and the Stoics.[144] The Academic Skeptic philosopher Cicero also followed this three-part division.[145]

This division is not obsolete, but has changed: natural philosophy has split into the various natural sciences, especially physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, and cosmology; moral philosophy has birthed the social sciences, while still including value theory (e.g. ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy, etc.); and metaphysical philosophy has given way to formal sciences such as logic, mathematics and philosophy of science, while still including epistemology, cosmology, etc. For example, Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687), since classified as a book of physics, uses the term natural philosophy as it was understood at the time, encompassing disciplines such as astronomy, medicine and physics that later became associated with the sciences.[16]

Methods of philosophy

Methods of philosophy are ways of conducting philosophical inquiry. They include techniques for arriving at philosophical knowledge and justifying philosophical claims as well as principles used for choosing between competing theories.[146][147][148] A great variety of methods has been employed throughout the history of philosophy. Many of them differ significantly from the methods used in the natural sciences in that they do not use experimental data obtained through measuring equipment.[149][150][151] The choice of one’s method usually has important implications both for how philosophical theories are constructed and for the arguments cited for or against them.[147][152][153] This choice is often guided by epistemological considerations about what constitutes philosophical evidence, how much support it offers, and how to acquire it.[149][147][154] Various disagreements on the level of philosophical theories have their source in methodological disagreements and the discovery of new methods has often had important consequences both for how philosophers conduct their research and for what claims they defend.[155][148][147] Some philosophers engage in most of their theorizing using one particular method while others employ a wider range of methods based on which one fits the specific problem investigated best.[150][156]

Methodological skepticism is a prominent method of philosophy. It aims to arrive at absolutely certain first principles by using systematic doubt to determine which principles of philosophy are indubitable.[157] The geometrical method tries to build a comprehensive philosophical system based on a small set of such axioms. It does so with the help of deductive reasoning to expand the certainty of its axioms to the system as a whole.[158][159] Phenomenologists seek certain knowledge about the realm of appearances. They do so by suspending their judgments about the external world in order to focus on how things appear independent of their underlying reality, a technique known as epoché.[160][148] Conceptual analysis is a well-known method in analytic philosophy. It aims to clarify the meaning of concepts by analyzing them into their fundamental constituents.[161][39][23] Another method often employed in analytic philosophy is based on common sense. It starts with commonly accepted beliefs and tries to draw interesting conclusions from them, which it often employs in a negative sense to criticize philosophical theories that are too far removed from how the average person sees the issue.[151][162][163] It is very similar to how ordinary language philosophy tackles philosophical questions by investigating how ordinary language is used.[148][164][165]

Various methods in philosophy give particular importance to intuitions, i.e. non-inferential impressions about the correctness of specific claims or general principles.[155][166] For example, they play an important role in thought experiments, which employ counterfactual thinking to evaluate the possible consequences of an imagined situation. These anticipated consequences can then be used to confirm or refute philosophical theories.[167][168][161] The method of reflective equilibrium also employs intuitions. It seeks to form a coherent position on a certain issue by examining all the relevant beliefs and intuitions, some of which often have to be deemphasized or reformulated in order to arrive at a coherent perspective.[155][169][170] Pragmatists stress the significance of concrete practical consequences for assessing whether a philosophical theory is true or false.[171][172] Experimental philosophy is of rather recent origin. Its methods differ from most other methods of philosophy in that it tries to answer philosophical questions by gathering empirical data in ways similar to social psychology and the cognitive sciences.[173][174]

Philosophical progress

Many philosophical debates that began in ancient times are still debated today. British philosopher Colin McGinn claims that no philosophical progress has occurred during that interval.[175] Australian philosopher David Chalmers, by contrast, sees progress in philosophy similar to that in science.[176] Meanwhile, Talbot Brewer, professor of philosophy at University of Virginia, argues that «progress» is the wrong standard by which to judge philosophical activity.[177]

Applied and professional philosophy

Some of those who study philosophy become professional philosophers, typically by working as professors who teach, research and write in academic institutions.[178] However, most students of academic philosophy later contribute to law, journalism, religion, sciences, politics, business, or various arts.[179][180] For example, public figures who have degrees in philosophy include comedians Steve Martin and Ricky Gervais, filmmaker Terrence Malick, Pope John Paul II, Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger, technology entrepreneur Peter Thiel, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, Jeopardy! host Alex Trebek, and US vice presidential candidate Carly Fiorina.[181][182] Curtis White has argued that philosophical tools are essential to humanities, sciences and social sciences.[183]

Recent efforts to avail the general public to the work and relevance of philosophers include the million-dollar Berggruen Prize, first awarded to Charles Taylor in 2016.[184] Some philosophers argue that this professionalization has negatively affected the discipline.[185]

Women in philosophy

Although men have generally dominated philosophical discourse, women philosophers have engaged in the discipline throughout history. The list of female philosophers throughout history is vast. Ancient examples include Hipparchia of Maroneia (active c. 325 BCE) and Arete of Cyrene (active 5th–4th centuries BCE). Some women philosophers were accepted during the medieval and modern eras, but none became part of the Western canon until the 20th and 21st century, when many suggest that G.E.M. Anscombe, Hannah Arendt, bell hooks, Simone de Beauvoir, Simone Weil and Susanne Langer entered the canon.[186][187][188]

In the early 1800s, some colleges and universities in the UK and the US began admitting women, producing more female academics. Nevertheless, U.S. Department of Education reports from the 1990s indicate that few women ended up in philosophy and that philosophy is one of the least gender-proportionate fields in the humanities, with women making up somewhere between 17% and 30% of philosophy faculty according to some studies.[189]

Prominent 21st century philosophers include: Judith Butler, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Martha Nussbaum, Onora O’Neill, and Nancy Fraser.[190] [191]

See also

- List of important publications in philosophy

- List of years in philosophy

- List of philosophy journals

- List of philosophy awards

- List of unsolved problems in philosophy

- Lists of philosophers

- Social theory

- Systems theory

- Wikipedia:Getting to Philosophy

References

Notes

- ^ Quinton, Anthony. The Ethics of Philosophical Practice. p. 666.

Philosophy is rationally critical thinking, of a more or less systematic kind about the general nature of the world (metaphysics or theory of existence), the justification of belief (epistemology or theory of knowledge), and the conduct of life (ethics or theory of value). Each of the three elements in this list has a non-philosophical counterpart, from which it is distinguished by its explicitly rational and critical way of proceeding and by its systematic nature. Everyone has some general conception of the nature of the world in which they live and of their place in it. Metaphysics replaces the unargued assumptions embodied in such a conception with a rational and organized body of beliefs about the world as a whole. Everyone has occasion to doubt and question beliefs, their own or those of others, with more or less success and without any theory of what they are doing. Epistemology seeks by argument to make explicit the rules of correct belief formation. Everyone governs their conduct by directing it to desired or valued ends. Ethics, or moral philosophy, in its most inclusive sense, seeks to articulate, in rationally systematic form, the rules or principles involved.

in Honderich 1995. - ^ Sharma, Arvind (1990). A Hindu Perspective on the Philosophy of Religion. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-349-20797-8. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

The attitude towards the existence of God varies within the Hindu religious tradition. This may not be entirely unexpected given the tolerance for doctrinal diversity for which the tradition is known. Thus of the six orthodox systems of Hindu philosophy, only three address the question in some detail. These are the schools of thought known as Nyaya, Yoga and the theistic forms of Vedanta.

- ^ Wynne, Alexander (2011). «The ātman and its negation». Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 33 (1–2): 103–05.

The denial that a human being possesses a ‘self’ or ‘soul’ is probably the most famous Buddhist teaching. It is certainly its most distinct, as has been pointed out by G.P. Malalasekera: ‘In its denial of any real permanent Soul or Self, Buddhism stands alone.’ A similar modern Sinhalese perspective has been expressed by Walpola Rahula: ‘Buddhism stands unique in the history of human thought in denying the existence of such a Soul, Self or Ātman.’ The ‘no Self’ or ‘no soul’ doctrine (Sanskrit: anātman; Pali: anattan) is particularly notable for its widespread acceptance and historical endurance. It was a standard belief of virtually all the ancient schools of Indian Buddhism (the notable exception being the Pudgalavādins), and has persisted without change into the modern era.… [B]oth views are mirrored by the modern Theravādin perspective of Mahasi Sayadaw that ‘there is no person or soul’ and the modern Mahāyāna view of the fourteenth Dalai Lama that ‘[t]he Buddha taught that…our belief in an independent self is the root cause of all suffering.‘

- ^ Gombrich, Richard (2006). Theravada Buddhism. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-134-90352-8. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

All phenomenal existence [in Buddhism] is said to have three interlocking characteristics: impermanence, suffering and lack of soul or essence.

- ^ Wainwright, William J. (2005). «Introduction». In Wainwright, W. J. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-0-19-803158-1. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. p. 3:

The expression ‘philosophy of religion’ did not come into general use until the nineteenth century, when it was employed to refer to the articulation and criticism of humanity’s religious consciousness and its cultural expressions in thought, language, feeling, and practice.

Citations

- ^ «philosophy (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ The definition of philosophy is: «1. orig., love of, or the search for, wisdom or knowledge 2. theory or logical analysis of the principles underlying conduct, thought, knowledge, and the nature of the universe». Webster’s New World Dictionary (Second College ed.).

- ^ «philosophy | Definition, Systems, Fields, Schools, & Biographies». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ «Philosophy». Lexico. University of Oxford Press. 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Sellars, Wilfrid (1963). Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (PDF). Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. 1, 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Chalmers, David J. (1995). «Facing up to the problem of consciousness». Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2 (3): 200, 219. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Henderson, Leah (2019). «The problem of induction». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1877). Tusculan Disputations. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 166. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

From whence all who occupied themselves in the contemplation of nature were both considered and called wise men; and that name of theirs continued to the age of Pythagoras, who is reported to have gone to Phlius, as we find it stated by Heraclides Ponticus, a very learned man, and a pupil of Plato, and to have discoursed very learnedly and copiously on certain subjects with Leon, prince of the Phliasii; and when Leon, admiring his ingenuity and eloquence, asked him what art he particularly professed, his answer was, that he was acquainted with no art, but that he was a philosopher. Leon, surprised at the novelty of the name, inquired what he meant by the name of philosopher, and in what philosophers differed from other men; on which Pythagoras replied, «That the life of man seemed to him to resemble those games which were celebrated with the greatest possible variety of sports and the general concourse of all Greece. For as in those games there were some persons whose object was glory and the honor of a crown, to be attained by the performance of bodily exercises, so others were led thither by the gain of buying and selling, and mere views of profit; but there was likewise one class of persons, and they were by far the best, whose aim was neither applause nor profit, but who came merely as spectators through curiosity, to observe what was done, and to see in what manner things were carried on there. And thus, said he, we come from another life and nature unto this one, just as men come out of some other city, to some much frequented mart; some being slaves to glory, others to money; and there are some few who, taking no account of anything else, earnestly look into the nature of things; and these men call themselves studious of wisdom, that is, philosophers: and as there it is the most reputable occupation of all to be a looker-on without making any acquisition, so in life, the contemplating things, and acquainting one’s self with them, greatly exceeds every other pursuit of life.»

- ^ Cameron, Alister (1938). The Pythagorean Background of the theory of Recollection. George Banta Publishing Company.

- ^ Jaeger, W. ‘On the Origin and Cycle of the Philosophic Ideal of Life.’ First published in Sitzungsberichte der preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historishce Klasse, 1928; Eng. Translation in Jaeger’s Aristotle, 2nd Ed. Oxford, 1948, 426-61.

- ^ Festugiere, A.J. (1958). «Les Trios Vies». Acta Congressus Madvigiani. Vol. 2. Copenhagen. pp. 131–78.

- ^ Guthrie, W. K. C. (1962–1981). A history of Greek philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-521-05160-6. OCLC 22488892. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

This does not of course amount to saying that the simile goes back to Pythagoras himself, but only that the Greek ideal of philosophia and theoria (for which we may compare Herodotus’s attribution of these activities to Solon I, 30) was at a fairly early date annexed by the Pythagoreans for their master

- ^ Adler, Mortimer J. (2000). How to Think About the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization. Chicago, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9412-3.

- ^ Quinton, Anthony. The Ethics of Philosophical Practice. p. 666.

Philosophy is rationally critical thinking, of a more or less systematic kind about the general nature of the world (metaphysics or theory of existence), the justification of belief (epistemology or theory of knowledge), and the conduct of life (ethics or theory of value). Each of the three elements in this list has a non-philosophical counterpart, from which it is distinguished by its explicitly rational and critical way of proceeding and by its systematic nature. Everyone has some general conception of the nature of the world in which they live and of their place in it. Metaphysics replaces the unargued assumptions embodied in such a conception with a rational and organized body of beliefs about the world as a whole. Everyone has occasion to doubt and question beliefs, their own or those of others, with more or less success and without any theory of what they are doing. Epistemology seeks by argument to make explicit the rules of correct belief formation. Everyone governs their conduct by directing it to desired or valued ends. Ethics, or moral philosophy, in its most inclusive sense, seeks to articulate, in rationally systematic form, the rules or principles involved.

in Honderich 1995. - ^ «The English word «philosophy» is first attested to c. 1300, meaning «knowledge, body of knowledge».

Harper, Douglas (2020). «philosophy (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b Lindberg 2007, p. 3.

- ^ «Epistemology in Classical Indian Philosophy». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2021.

- ^ Shapin, Steven (1998). The Scientific Revolution (1st ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-75021-7.

- ^ Briggle, Robert; Frodeman, Adam (11 January 2016). «When Philosophy Lost Its Way | The Opinionator». New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ «Metaphysics». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ «Epistemology». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ «philosophy (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Audi, Robert (2006). «Philosophy». Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Macmillan. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b Honderich, Ted (2005). «Philosophy». The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sandkühler, Hans Jörg (2010). «Philosophiebegriffe». Enzyklopädie Philosophie. Meiner. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Joll, Nicholas. «Metaphilosophy». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Overgaard, Søren; Gilbert, Paul; Burwood, Stephen (2013). «What is philosophy?». An Introduction to Metaphilosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–44. ISBN 978-0-521-19341-2. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ «philosophy». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Baggini, Julian; Krauss, Lawrence (8 September 2012). «Philosophy v science: which can answer the big questions of life?». the Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b Mittelstraß, Jürgen (2005). «Philosophie». Enzyklopädie Philosophie und Wissenschaftstheorie. Metzler. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Quine, Willard Van Orman (2008). «41. A Letter to Mr. Ostermann». Quine in Dialogue. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03083-1. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Rescher, Nicholas (2 May 2013). «1. The Nature of Philosophy». On the Nature of Philosophy and Other Philosophical Essays. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-032020-6. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Nuttall, Jon (3 July 2013). «1. The Nature of Philosophy». An Introduction to Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-6807-9. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Hylton, Peter; Kemp, Gary (2020). «Willard Van Orman Quine: 3. The Analytic-Synthetic Distinction and the Argument Against Logical Empiricism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Gelan, Victor Eugen (2020). «Husserl’s Idea of Rigorous Science and Its Relevance for the Human and Social Sciences». The Subject(s) of Phenomenology: Rereading Husserl. Contributions to Phenomenology. Vol. 108. Springer International Publishing. pp. 97–105. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-29357-4_6. ISBN 978-3-030-29357-4. S2CID 213082313. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Ingarden, Roman (1975). «The Concept of Philosophy as Rigorous Science». On the Motives which led Husserl to Transcendental Idealism. Phaenomenologica. Vol. 64. Springer Netherlands. pp. 8–11. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1689-6_3. ISBN 978-94-010-1689-6. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Chalmers, David J. (2015). «Why Isn’t There More Progress in Philosophy?». Philosophy. 90 (1): 3–31. doi:10.1017/s0031819114000436. hdl:1885/57201. S2CID 170974260. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Dellsén, Finnur; Lawler, Insa; Norton, James (29 June 2021). «Thinking about Progress: From Science to Philosophy». Noûs. 56 (4): 814–840. doi:10.1111/nous.12383. S2CID 235967433.

- ^ a b SHAFFER, MICHAEL J. (2015). «The Problem of Necessary and Sufficient Conditions and Conceptual Analysis». Metaphilosophy. 46 (4/5): 555–563. doi:10.1111/meta.12158. ISSN 0026-1068. JSTOR 26602327. S2CID 148551744. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Biletzki, Anat; Matar, Anat (2021). «Ludwig Wittgenstein: 3.7 The Nature of Philosophy». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Piché, Claude (2016). «Kant on the «Conditions of the Possibility» of Experience». Transcendental Inquiry: Its History, Methods and Critiques. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40715-9_1. hdl:1866/21324. ISBN 978-3-319-40715-9. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Wheeler, Michael (2020). «Martin Heidegger». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Banicki, Konrad (2014). «Philosophy as Therapy: Towards a Conceptual Model». Philosophical Papers. 43 (1): 7–31. doi:10.1080/05568641.2014.901692. S2CID 144901869. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Hadot, Pierre (1997). «11. Philosophy as a Way of Life». Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises From Socrates to Foucault. Blackwell. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Grimm, Stephen R.; Cohoe, Caleb (2021). «What is philosophy as a way of life? Why philosophy as a way of life?». European Journal of Philosophy. 29 (1): 236–251. doi:10.1111/ejop.12562. ISSN 1468-0378. S2CID 225504495. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ McIvor, David W. «Weltanschauung». International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Garfield, Jay L; Edelglass, William, eds. (9 June 2011). «Introduction». The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195328998.001.0001. ISBN 9780195328998. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich; Brown, Robert F. (2006). Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Greek philosophy. Clarendon Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-19-927906-7.

- ^ Whitehead, Alfred North (11 May 2010). Process and Reality. Simon & Schuster. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4391-1836-8.

- ^ Kenny, Anthony (17 June 2004). Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162252-6.

- ^ Kenny, Anthony (31 May 2007). Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy, Volume 2. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162253-3.

- ^ Collinson, Diane. Fifty Major Philosophers, A Reference Guide. p. 125.

- ^ Kenny, Anthony (29 June 2006). The Rise of Modern Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy, Volume 3. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-875277-6.

- ^ Philosophy before the Greeks 2015, pp. vii–viii, 187–188.

- ^ Philosophy before the Greeks 2015, p. 218.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1976). Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. pp. 61 ff. ISBN 0-520-03615-8.

- ^ Najovits, Simson (2004). Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree, A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land, Vol. II. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 978-0875862569.

- ^ a b Assmann, Jan (2004). «Theological Responses to Amarna» (PDF). In Knoppers, Gary N.; Hirsch, Antoine (eds.). Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World. Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford. Leiden/Boston. pp. 179–191. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2020.

- ^ Frank, Daniel; Leaman, Oliver (20 October 2005). History of Jewish Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-89435-2.

- ^ Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W. (15 October 2013). Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-4471-0.

- ^ Churton, Tobias (25 January 2005). Gnostic Philosophy: From Ancient Persia to Modern Times. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-767-7.

- ^ Nasr, S. H.; Aminrazavi, Mehdi; Jozi, M. R. (30 September 2008). An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 2: Ismaili Thought in the Classical Age. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-542-5.

- ^ Keddie, Nikki R. (28 October 2013). Iran: Religion, Politics and Society: Collected Essays. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-28041-2.

- ^ de Blois, François (2000). «Dualism in Iranian and Christian Traditions». Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 10 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1017/S1356186300011913. ISSN 1356-1863. JSTOR 25187928. S2CID 162835432.

- ^ Gutas, Dimitri (1998). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th centuries). Routledge. pp. 1–26.

- ^ Cooper, William W.; Yue, Piyu (2008). Challenges of the Muslim world: present, future and past. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0-444-53243-5.

- ^ N.V. Isaeva (1992). Shankara and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7. OCLC 24953669. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ John Koller (2013). «Shankara». In Chad Meister and Paul Copan (ed.). Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203813010. ISBN 978-1-136-69685-5. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (2009). «darśana». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. From: Johnson, W. J., ed. (2009). «darśan(a)». A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001. ISBN 9780191726705. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020.

- ^ «Epistemology in Classical Indian Philosophy». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2021.

- ^ Sedlmeier, Peter; Srinivas, Kunchapudi (2016). «How do Theories of Cognition and Consciousness in Ancient Indian Thought Systems Relate to Current Western Theorizing and Research?». Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 343. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00343. PMC 4791389. PMID 27014150.

- ^ «What Erwin Schrödinger Said About the Upanishads – the Wire Science».

- ^ Young, William A. (2005). The World’s Religions: Worldviews and Contemporary Issues. Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 61–64, 78–79. ISBN 978-0-13-183010-3. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Gene (2017). Religions of India: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–5, 15–18, 53–55, 63–67, 85–88, 93–98, 107–15. ISBN 978-1-134-79193-4. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Bowker, John (1999). The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-19-866242-6.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2014). On Hinduism. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-936008-6. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Kesarcodi-Watson, Ian (1978). «Hindu Metaphysics and Its Philosophies: Śruti and Darsána». International Philosophical Quarterly. 18 (4): 413–432. doi:10.5840/ipq197818440.

- ^ Chadha, M. (2015). Oppy, G. (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy of Religion. London: Routledge. pp. 127–28. ISBN 978-1844658312.

- ^ Frazier, Jessica (2011). The Continuum companion to Hindu studies. London: Continuum. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

- ^ Olson, Carl (2007). The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction. Rutgers University Press. pp. 101–19. ISBN 978-0813540689.

- ^ Deutsch, Eliot S. (2000). «Karma as a ‘Convenient Fiction’ in the Advaita Vedānta». In Perrett, R. (ed.). Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy. Vol. 4. Routledge. pp. 245–48. ISBN 978-0815336112.

- ^ Grimes, John A. (January 1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0791430675.

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2007). «Hinduism». In Kitagawa, J. (ed.). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. London: Routledge.

- ^ Minor, Robert (1986). Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 74–75, 81. ISBN 0-88706-297-0.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2018) [1998]. «Bhagavad Gita». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Cowell and Gough (1882, Translators), The Sarva-Darsana-Samgraha or Review of the Different Systems of Hindu Philosophy by Madhva Acharya, Trubner’s Oriental Series.

- ^ a b Bilimoria, Puruṣottama (2000). «Hindu Doubts About God: Towards a Mīmāṃsā Deconstruction». In Perrett, Roy W. (ed.). Indian Philosophy. London: Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1135703226.

- ^ Bhattacharya, R (2011). Studies on the Carvaka/Lokayata. Anthem. pp. 53, 94, 141–142. ISBN 978-0857284334.

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes (2012). «Free will and Indian philosophy». Antiquorum Philosophia. Roma Italy. 6: 19–30.

- ^ Lochtefeld, James (2002). «Ajivika». The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M. Rosen Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-0823931798.

- ^ Basham, A. L. (2009). History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas – a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-8120812048.

- ^ Jayatilleke, K. N. (2010). Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. pp. 246–49, note 385 onwards. ISBN 978-8120806191.

- ^ Dundas, Paul (2002). The Jains (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 1–19, 40–44. ISBN 978-0415266055.

- ^ Hemacandra (1998). The Lives of the Jain Elders. Oxford University Press. pp. 258–60. ISBN 978-0-19-283227-6. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ Tiwari, Kedar Nath (1983). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 78–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0293-3. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979]. The Jaina Path of Purification. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 81–83. ISBN 81-208-1578-5. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ Umāsvāti (1994) [c. 2nd – 5th century]. That Which Is: Tattvartha Sutra. Translated by Tatia, N. HarperCollins. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-0-06-068985-8. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020.

- ^ «What Erwin Schrödinger Said About the Upanishads – the Wire Science».

- ^ Westerhoff 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Westerhoff 2018, p. 8.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–47. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Westerhoff 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Westerhoff 2018, p. xxiv.

- ^ Dreyfus, Georges B. J. (1997). Recognizing Reality: Dharmakirti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations (Suny Series in Buddhist Studies). p. 22.

- ^ JeeLoo Liu. Tian-tai Metaphysics vs. Hua-yan Metaphysics A Comparative Study.

- ^ Garfield, Jay L.; Edelglass, William, eds. (2011). «Chinese Philosophy». The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195328998.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 42.

- ^ O’Brien, Barbara (25 June 2019). «How Buddhism Came to China: A History of the First Thousand Years». Learn Religions. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ «Chinese Religions and Philosophies». Asia Society. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Perez, Louis G. (1998). The History of Japan. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-313-30296-1.

- ^ Janz, Bruce B. (2009). Philosophy in an African Place. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books. pp. 74–79.

- ^ a b Whiteley, Peter M. (1998). «Native American philosophy». Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N078-1. ISBN 9780415250696. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020.

- ^ Pierotti, Raymond (2003). «Communities as both Ecological and Social entities in Native American thought» (PDF). Native American Symposium 5. Durant, OK: Southeastern Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016.

- ^ Portilla, Miguel León (1990). Use of «Tlamatini» in Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind – Miguel León Portilla. ISBN 9780806122953. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b Leonardo Esteban Figueroa Helland (2012). Indigenous Philosophy and World Politics: Cosmopolitical Contributions from across the Americas (PDF) (PhD dissertation). Arizona State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Maffie, James (March 2002). «Why Care about Nezahualcoyotl? Veritism and Nahua Philosophy». Philosophy of the Social Sciences. Sage Publications. 32 (1): 71–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.878.7615. doi:10.1177/004839310203200104. S2CID 144901245. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b «Aztec Philosophy». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ a b Yeakel, John A. (Fall 1983). «Accountant-Historians of the Incas» (PDF). Accounting Historians Journal. 10 (2): 39–51. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.10.2.39. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Adames, Hector Y.; Chavez-Dueñas, Nayeli Y. (2016). Cultural Foundations and Interventions in Latino/a Mental Health: History, Theory and within Group Differences. Routledge. pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Maffie, James (2013). «Pre-Columbian Philosophies». A Companion to Latin American Philosophy. By Nuccetelli, Susana; Schutte, Ofelia; Bueno, Otávio. Wiley Blackwell.

- ^ Webb, Hillary S. (2012). Yanantin and Masintin in the Andean World: Complementary Dualism in Modern Peru.

- ^ Plantinga, Alvin (2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Religion and Science (Spring 2014 ed.). Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Michael (Editor in Chief) (1998) Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. New York, Oxford, Oxford University Press. 4 vol. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-19-511307-5.

- ^ Riedel, Tom. «[Review:] Encyclopedia of Aesthetics» (PDF). Art Documentation. 18 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2006.

- ^ «Aesthetic». Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Zangwill, Nick (2019) [2003]. «Aesthetic Judgment». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (revised ed.). Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ «aesthetic». Lexico. Oxford University Press and Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020.

- ^ Mill, John Stuart (1863). Utilitarianism. London: Parker, Son, and Bourn, West Strand. p. 51. OCLC 78070085.

- ^ a b «Ethics». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d «Major Ethical Perspectives». saylordotorg.github.io. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ «Epistemology». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d «Epistemology». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.