From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, a word stem is a part of a word responsible for its lexical meaning. The term is used with slightly different meanings depending on the morphology of the language in question. In Athabaskan linguistics, for example, a verb stem is a root that cannot appear on its own and that carries the tone of the word.

In most cases, a word stem is not modified during its declension, while in some languages it can be modified (apophony) according to certain morphological rules or peculiarities, such as sandhi. For example in Polish: miast-o («city»), but w mieść-e («in the city»). In English: «sing», «sang», «sung».

Uncovering and analyzing cognation between word stems and roots within and across languages has allowed comparative philology and comparative linguistics to determine the history of languages and language families.[1]

Usage[edit]

In one usage, a word stem is a form to which affixes can be attached.[2] Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the word stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new stem friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached. In a variant of this usage, the root of the word (in the example, friend) is not counted as a stem (in the example, the variant contains the stem friendship, where -s is attached).

In a slightly different usage, which is adopted in the remainder of this article, a word has a single stem, namely the part of the word that is common to all its inflected variants.[3] Thus, in this usage, all derivational affixes are part of the stem. For example, the stem of friendships is friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached.

Word stems may be a root, e.g. run, or they may be morphologically complex, as in compound words (e.g. the compound nouns meatball or bottleneck) or words with derivational morphemes (e.g. the derived verbs black-en or standard-ize). Hence, the stem of the complex English noun photographer is photo·graph·er, but not photo. For another example, the root of the English verb form destabilized is stabil-, a form of stable that does not occur alone; the stem is de·stabil·ize, which includes the derivational affixes de- and -ize, but not the inflectional past tense suffix -(e)d. That is, a stem is that part of a word that inflectional affixes attach to.

For example, the stem of the verb wait is wait: it is the part that is common to all its inflected variants.

- wait (infinitive)

- wait (imperative)

- waits (present, 3rd people, singular)

- wait (present, other persons and/or plural)

- waited (simple past)

- waited (past participle)

- waiting (progressive)

Citation forms and bound morphemes[edit]

In languages with very little inflection, such as English and Chinese, the stem is usually not distinct from the «normal» form of the word (the lemma, citation or dictionary form). However, in other languages, word stems may rarely or never occur on their own. For example, the English verb stem run is indistinguishable from its present tense form (except in the third person singular). However, the equivalent Spanish verb stem corr- never appears as such because it is cited with the infinitive inflection (correr) and always appears in actual speech as a non-finite (infinitive or participle) or conjugated form. Such morphemes that cannot occur on their own in this way are usually referred to as bound morphemes.

In computational linguistics, the term «stem» is used for the part of the word that never changes, even morphologically, when inflected, and a lemma is the base form of the word.[citation needed] For example, given the word «produced», its lemma (linguistics) is «produce», but the stem is «produc» because of the inflected form «producing».

Paradigms and suppletion[edit]

A list of all the inflected forms of a word stem is called its inflectional paradigm. The paradigm of the adjective tall is given below, and the stem of this adjective is tall.

- tall (positive); taller (comparative); tallest (superlative)

Some paradigms do not make use of the same stem throughout; this phenomenon is called suppletion. An example of a suppletive paradigm is the paradigm for the adjective good: its stem changes from good to the bound morpheme bet-.

- good (positive); better (comparative); best (superlative)

Oblique stem [edit]

Both in Latin and in Greek, the declension (inflection) of some nouns uses a different stem in the oblique cases than in the nominative and vocative singular cases. Such words belong to, respectively, the so-called third declension of the Latin grammar and the so-called third declension of the Ancient Greek grammar. For example, the genitive singular is formed by adding -is (Latin) or -ος (Greek) to the oblique stem, and the genitive singular is conventionally listed in Greek and Latin dictionaries to illustrate the oblique.

Examples[edit]

|

|

English words derived from Latin or Greek often involve the oblique stem: adipose, altitudinal, android, mathematics.

Historically, the difference in stems arose due to sound change in the nominative. In the Latin third declension, for example, the nominative singular suffix -s combined with a stem-final consonant. If that consonant was c, the result was x (a mere orthographic change), while if it was g, the -s caused it to devoice, again resulting in x. If the stem-final consonant was another alveolar consonant (t, d, r), it elided before the -s. In a later era, n before the nominative ending was also lost, producing pairs like atlas, atlant- (for English Atlas, Atlantic).

See also[edit]

- Lemma (morphology)

- Lexeme

- Morphological typology

- Morphology (linguistics)

- Principal parts

- Root (linguistics)

- Stemming algorithms (computer science)

- Thematic vowel

References[edit]

- ^ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Indo-European Roots Appendix, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ Geoffrey Sampson; Paul Martin Postal (2005). The ‘language instinct’ debate. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8264-7385-1. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ Paul Kroeger (2005). Analyzing grammar. Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-521-81622-9. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- What is a stem? — SIL International, Glossary of Linguistic Terms.

- Bauer, Laurie (2003) Introducing Linguistic Morphology. Georgetown University Press; 2nd edition.

- Williams, Edwin and Anna-Maria DiScullio (1987) On the definition of a word. Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

External links[edit]

- Searchable reference for word stems including affixes (prefixes and suffixes)

In English grammar and morphology, a stem is the form of a word before any inflectional affixes are added. In English, most stems also qualify as words.

The term base is commonly used by linguists to refer to any stem (or root) to which an affix is attached.

Identifying a Stem

«A stem may consist of a single root, of two roots forming a compound stem, or of a root (or stem) and one or more derivational affixes forming a derived stem.»

(R. M. W. Dixon, The Languages of Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Combining Stems

«The three main morphological processes are compounding, affixation, and conversion. Compounding involves adding two stems together, as in the above window-sill — or blackbird, daydream, and so on. … For the most part, affixes attach to free stems, i.e., stems that can stand alone as a word. Examples are to be found, however, where an affix is added to a bound stem — compare perishable, where perish is free, with durable, where dur is bound, or unkind, where kind is free, with unbeknown, where beknown is bound.»

(Rodney D. Huddleston, English Grammar: An Outline. Cambridge University Press, 1988)

Stem Conversion

«Conversion is where a stem is derived without any change in form from one belonging to a different class. For example, the verb bottle (I must bottle some plums) is derived by conversion from the noun bottle, while the noun catch (That was a fine catch) is converted from the verb.»

(Rodney D. Huddleston, English Grammar: An Outline. Cambridge University Press, 1988)

The Difference Between a Base and a Stem

«Base is the core of a word, that part of the word which is essential for looking up its meaning in the dictionary; stem is either the base by itself or the base plus another morpheme to which other morphemes can be added. [For example,] vary is both a base and a stem; when an affix is attached the base/stem is called a stem only. Other affixes can now be attached.»

(Bernard O’Dwyer, Modern English Structures: Form, Function, and Position. Broadview, 2000)

The Difference Between a Root and a Stem

«The terms root and stem are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there is a subtle difference between them: a root is a morpheme that expresses the basic meaning of a word and cannot be further divided into smaller morphemes. Yet a root does not necessarily constitute a fully understandable word in and of itself. Another morpheme may be required. For example, the form struct in English is a root because it cannot be divided into smaller meaningful parts, yet neither can it be used in discourse without a prefix or a suffix being added to it (construct, structural, destruction, etc.) »

«A stem may consist of just a root. However, it may also be analyzed into a root plus derivational morphemes … Like a root, a stem may or may not be a fully understandable word. For example, in English, the forms reduce and deduce are stems because they act like any other regular verb—they can take the past-tense suffix. However, they are not roots, because they can be analyzed into two parts, -duce, plus a derivational prefix re- or de-.»

«So some roots are stems, and some stems are roots. ., but roots and stems are not the same thing. There are roots that are not stems (-duce), and there are stems that are not roots (reduce). In fact, this rather subtle distinction is not extremely important conceptually, and some theories do away with it entirely.»

(Thomas Payne, Exploring Language Structure: A Student’s Guide. Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Irregular Plurals

«Once there was a song about a purple-people-eater, but it would be ungrammatical to sing about a purple-babies-eater. Since the licit irregular plurals and the illicit regular plurals have similar meanings, it must be the grammar of irregularity that makes the difference.»

«The theory of word structure explains the effect easily. Irregular plurals, because they are quirky, have to be stored in the mental dictionary as roots or stems; they cannot be generated by a rule. Because of this storage, they can be fed into the compounding rule that joins an existing stem to another existing stem to yield a new stem. But regular plurals are not stems stored in the mental dictionary; they are complex words that are assembled on the fly by inflectional rules whenever they are needed. They are put together too late in the root-to-stem-to-word assembly process to be available to the compounding rule, whose inputs can only come out of the dictionary.»

(Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. William Morrow, 1994)

Word is the principal and

basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and

the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

According

to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic

and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one

root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word

fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words –

according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words

are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational

morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words

are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of

derivational morphemes being insignificant.

There can be both root- and

derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder,

light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball,

etc.

The

term morpheme

is derived from Greek

morphe

“form ”+ -eme.

The Greek suffix –eme

has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the

minimum distinctive

feature.

The morpheme is the smallest

meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete

unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts

of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single

morpheme.

The

root-morpheme

is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and

abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related

words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach,

teacher, teaching.

Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of

meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which

is not found in roots.

Affixational

morphemes

include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes.

Inflections

carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the

formation of word-forms. Derivational

affixes

are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically

always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same

types of meaning as found in roots, most of them have the

part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important

part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the

word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the

derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different

parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots

and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the

difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words

helpless,

handy, blackness, Londoner, refill,

etc.: the root-morphemes help-,

hand-, black-, London-, fill-,

are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less,

-y, -ness, -er, re-

are

felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of

free and bound morphemes.

Free

morphemes

coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is

obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the

morpheme boy-

in the word boy

is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable

there is only one free morpheme desire-;

the word pen-holder

has two free morphemes pen-

and

hold-.

It follows that bound

morphemes

are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms,

consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness,

-able, -er

are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes

theor-

in the words theory,

theoretical, or

horr-

in the words horror,

horrible, horrify; Angl- in

Anglo-Saxon; Afr-

in Afro-Asian

are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

The

stem

is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged

throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm

(to) ask

( ), asks,

asked, asking is

ask-;

the

stem of the word singer

(

), singer’s,

singers, singers’ is

singer-.

It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the

word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

Simple

stems are

semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy

with which new stems may be modeled.

Simple

stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the

root morpheme.

Retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc.

should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived

stems – root

and derivational affix.

Compound

stems are

made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for

example match-box,

driving-suit, pen-holder,

etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the

other derived.

Bound

stem – is

not harmonious to a separate word.

To

study the motivation of the word the method of immediate ultimate

consistent is used. It is based on bannery opposition – each state

of segmentation involves 2 components words brake into.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

| Examples |

|---|

The stem of the verb wait is wait: it is the part that is common to all its inflected variants.

|

In linguistics, a stem is a part of a word. The term is used with slightly different meanings.

In one usage, a stem is a form to which affixes can be attached.[1] Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new stem friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached. In a variant of this usage, the root of the word (in the example, friend) is not counted as a stem.

In a slightly different usage, which is adopted in the remainder of this article, a word has a single stem, namely the part of the word that is common to all its inflected variants.[2] Thus, in this usage, all derivational affixes are part of the stem. For example, the stem of friendships is friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached.

Stems may be roots, e.g. run, or they may be morphologically complex, as in compound words (cf. the compound nouns meat ball or bottle opener) or words with derivational morphemes (cf. the derived verbs black-en or standard-ize). Thus, the stem of the complex English noun photographer is photo·graph·er, but not photo. For another example, the root of the English verb form destabilized is stabil-, a form of stable that does not occur alone; the stem is de·stabil·ize, which includes the derivational affixes de- and -ize, but not the inflectional past tense suffix -(e)d. That is, a stem is that part of a word that inflectional affixes attach to.

The exact use of the word ‘stem’ depends on the morphology of the language in question. In Athabaskan linguistics, for example, a verb stem is a root that cannot appear on its own, and that carries the tone of the word. Athabaskan verbs typically have two stems in this analysis, each preceded by prefixes.

Contents

- 1 Citation forms and bound morphemes

- 2 Paradigms and suppletion

- 3 See also

- 4 References

- 5 External links

Citation forms and bound morphemes

In languages with very little inflection, such as English and Chinese, the stem is usually not distinct from the «normal» form of the word (the lemma, citation or dictionary form). However, in other languages, stems may rarely or never occur on their own. For example, the English verb stem run is indistinguishable from its present tense form (except in the third person singular); but the equivalent Spanish verb stem corr- never appears as such, since it is cited with the infinitive inflection (correr) and always appears in actual speech as a non-finite (infinitive or participle) or conjugated form. Morphemes like Spanish corr- which can’t occur on their own in this way, are usually referred to as bound morphemes.

In computational linguistics, a stem is the part of the word that never changes even when morphologically inflected, whilst a lemma is the base form of the verb. For example, given the word «produced», its lemma (linguistics) is «produce», however the stem is «produc»: this is because there are words such as production. [3]

Paradigms and suppletion

A list of all the inflected forms of a stem is called its inflectional paradigm. The paradigm of the adjective tall is given below, and the stem of this adjective is tall.

- tall (positive); taller (comparative); tallest (superlative)

Some paradigms do not make use of the same stem throughout; this phenomenon is called suppletion. An example of a suppletive paradigm is the paradigm for the adjective good: its stem changes from good to the bound morpheme bet-.

- good (positive); better (comparative); best (superlative)

See also

- Lemma (morphology)

- Lexeme

- Morphological typology

- Morphology (linguistics)

- Principal parts

- Root (linguistics)

- Stemming algorithms (Computer science)

- Vowel stems

References

- ^ Geoffrey Sampson; Paul Martin Postal (2005). The ‘language instinct’ debate. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN 9780826473851. http://books.google.de/books?id=N0zJNPuXTZMC&pg=PA124&lpg=PA124&dq=%22a+root+is%22+%22a+stem+is%22&source=bl&ots=Amv01e0fmE&sig=p1LNjJBk5iHCDqpf7IDzRKGG3sY&hl=en&ei=bSZmSqCwAYegngOXlJH4Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ Paul Kroeger (2005). Analyzing grammar. Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 9780521816229. http://books.google.com/books?id=rSglHbBaNyAC&pg=PA248&dq=%22a+stem+is%22+%22a+root+is%22&ei=4CxmSvaCHIqyzQSOg6XpAw&hl=de. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ http://nltk.sourceforge.net/index.php/Book

- What is a stem? — SIL International, Glossary of Linguistics Terms.

- Bauer, Laurie (2003) Introducing Linguistic Morphology. Georgetown University Press; 2nd edition.

- Williams, Edwin and Anna-Maria DiScullio (1987) On the definition of a word. Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

External links

- Searchable reference for word stems including affixes (prefixes and suffixes)

: Part of a word responsible for its lexical meaning

In linguistics, a word stem is a part of a word responsible for its lexical meaning. The term is used with slightly different meanings depending on the morphology of the language in question. In Athabaskan linguistics, for example, a verb stem is a root that cannot appear on its own and that carries the tone of the word. Athabaskan verbs typically have two stems in this analysis, each preceded by prefixes.

In most cases, a word stem is not modified during its declension, while in some languages it can be modified (apophony) according to certain morphological rules or peculiarities, such as sandhi. For example in Polish: miast-o («city»), but w mieść-e («in the city»). In English: «sing», «sang», «sung».

Uncovering and analyzing cognation between word stems and roots within and across languages has allowed comparative philology and comparative linguistics to determine the history of languages and language families.[1]

Usage

In one usage, a word stem is a form to which affixes can be attached.[2] Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the word stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new stem friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached. In a variant of this usage, the root of the word (in the example, friend) is not counted as a stem (in the example, the variant contains the stem friendship, where -s is attached).

In a slightly different usage, which is adopted in the remainder of this article, a word has a single stem, namely the part of the word that is common to all its inflected variants.[3] Thus, in this usage, all derivational affixes are part of the stem. For example, the stem of friendships is friendship, to which the inflectional suffix -s is attached.

Word stems may be a root, e.g. run, or they may be morphologically complex, as in compound words (e.g. the compound nouns meatball or bottleneck) or words with derivational morphemes (e.g. the derived verbs black-en or standard-ize). Hence, the stem of the complex English noun photographer is photo·graph·er, but not photo. For another example, the root of the English verb form destabilized is stabil-, a form of stable that does not occur alone; the stem is de·stabil·ize, which includes the derivational affixes de- and -ize, but not the inflectional past tense suffix -(e)d. That is, a stem is that part of a word that inflectional affixes attach to.

For example, the stem of the verb wait is wait: it is the part that is common to all its inflected variants.

- wait (infinitive)

- wait (imperative)

- waits (present, 3rd people, singular)

- wait (present, other persons and/or plural)

- waited (simple past)

- waited (past participle)

- waiting (progressive)

Citation forms and bound morphemes

- Main page: Social:Lemma (morphology)

In languages with very little inflection, such as English and Chinese, the stem is usually not distinct from the «normal» form of the word (the lemma, citation or dictionary form). However, in other languages, word stems may rarely or never occur on their own. For example, the English verb stem run is indistinguishable from its present tense form (except in the third person singular). However, the equivalent Spanish verb stem corr- never appears as such because it is cited with the infinitive inflection (correr) and always appears in actual speech as a non-finite (infinitive or participle) or conjugated form. Such morphemes that cannot occur on their own in this way are usually referred to as bound morphemes.

In computational linguistics, the term «stem» is used for the part of the word that never changes, even morphologically, when inflected, and a lemma is the base form of the word. For example, given the word «produced», its lemma (linguistics) is «produce», but the stem is «produc» because of the inflected form «producing».

Paradigms and suppletion

A list of all the inflected forms of a word stem is called its inflectional paradigm. The paradigm of the adjective tall is given below, and the stem of this adjective is tall.

- tall (positive); taller (comparative); tallest (superlative)

Some paradigms do not make use of the same stem throughout; this phenomenon is called suppletion. An example of a suppletive paradigm is the paradigm for the adjective good: its stem changes from good to the bound morpheme bet-.

- good (positive); better (comparative); best (superlative)

Oblique stem

Both in Latin and in Greek, the declension (inflection) of some nouns uses a different stem in the oblique cases than in the nominative and vocative singular cases. Such words belong to, respectively, the so-called third declension of the Latin grammar and the so-called third declension of the Ancient Greek grammar. For example, the genitive singular is formed by adding -is (Latin) or -ος (Greek) to the oblique stem, and the genitive singular is conventionally listed in Greek and Latin dictionaries to illustrate the oblique.

Examples

|

|

English words derived from Latin or Greek often involve the oblique stem: adipose, altitudinal, android, mathematics.

Historically, the difference in stems arose due to sound change in the nominative. In the Latin third declension, for example, the nominative singular suffix -s combined with a stem-final consonant. If that consonant was c, the result was x (a mere orthographic change), while if it was g, the -s caused it to devoice, again resulting in x. If the stem-final consonant was another alveolar consonant (t, d, r), it elided before the -s. In a later era, n before the nominative ending was also lost, producing pairs like atlas, atlant- (for English Atlas, Atlantic).

See also

- Lemma (morphology)

- Lexeme

- Morphological typology

- Morphology (linguistics)

- Principal parts

- Root (linguistics)

- Stemming algorithms (computer science)

- Thematic vowel

References

- ↑ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Indo-European Roots Appendix, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, https://ahdictionary.com/word/indoeurop.html.

- ↑ Geoffrey Sampson; Paul Martin Postal (2005). The ‘language instinct’ debate. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8264-7385-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=N0zJNPuXTZMC&pg=PA124. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ Paul Kroeger (2005). Analyzing grammar. Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-521-81622-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=rSglHbBaNyAC&pg=PA248. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- What is a stem? — SIL International, Glossary of Linguistic Terms.

- Bauer, Laurie (2003) Introducing Linguistic Morphology. Georgetown University Press; 2nd edition.

- Williams, Edwin and Anna-Maria DiScullio (1987) On the definition of a word. Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

External links

- Searchable reference for word stems including affixes (prefixes and suffixes)

eo:Radiko#Lingvo

I thought to quote from two websites that aided me, but to facilitate reading, I edit slightly and eschew blockquotes (>). The first quote is written with plainer and simpler diction and so ought to be read before the second with more formal diction.

1 of 2 quotes

Bases, stems, and roots are the main components of words, just like cells, atoms, and protons are the main components of matter.

In linguistics, the words «roots» is the core of the word. It is the morpheme that comprises the most important part of the word. It is also the primary unit of the family of the same word. Keep in mind that the root is mono-morphemic, or made of just one «chunk», or morpheme. Without the root, the word would not have any meaning. If you take the root away, all that you have left is affixes either before or after it. Such affixes do not have a lexical meaning on their own.

An example of a root is the word «act».

Now let’s look at what is a stem and a base and apply them to the root «act» so that you can see how they differ and interconnect to transform a lexical word altogether.

The stem occurs after affixes have been added to the root, for example:

Re-act ↝ Re-act-ion

Hence a stem is a form to which affixes (prefixes or suffixes) have been added. It is important to differentiate it from a root, because the root alone cannot be applied in discourse, whereas the stem exists precisely to be applied to discourse.

A base is the same as a root except that the root has no lexical meaning while the base does: «to act» is the infinitive of «act» and is structured with the base «act». In many words in our language, a word can be all three: a root, base, and stem (eg: «deer»). They differ in how they are applied during discourse (stem, base) and whether, on their own, they have any lexical meaning (stem, base) or no lexical meaning whatsoever (root).

An example of root, base and stem joined together is the word «refrigerator»:

The Latin root is frīg, which has no meaning in English on its own, and which requires a change in spelling for suffixes.

⟹ refrigerāre = Latin prefix + root + suffix, with no meaning in English of its own yet.

⟹ re- + friger + -ate + -tor = prefix + root + 2 suffixes.

The 2 suffices now produce lexical meaning = stem; spelling changes are required for suffixes.

[The links included with the answer contain the Glossary of Linguistic Terminology for further information.]

Sources: http://www-01.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsABoundRoot.htm

http://www-01.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsAStem.htm

2 of 2 quotes

Root, stem, base

Taken from: […] English [W]ord-[F]ormation […] by Laurie Bauer, 1983 (published by Cambridge University Press).

‘Root’, ‘stem’ and ‘base’ are all terms used in the literature to designate that part of a word that remains when all affixes have been removed.

A root is a form which is not further analysable, either in terms of derivational or inflectional morphology. It is that part of word-form that remains when all inflectional and derivational affixes have been removed. A root is the basic part always present in a lexeme. In the form ‘untouchables’ the root is ‘touch’, to which first the suffix ‘-able’, then the prefix ‘un-‘ and finally the suffix ‘-s’ have been added. In a compound word like ‘wheelchair’ there are two roots, ‘wheel’ and ‘chair’.

A stem is of concern only when dealing with inflectional morphology.

In the form ‘untouchables’ the stem is ‘untouchable’, although in the form ‘touched’ the stem is ‘touch’; in the form ‘wheelchairs’ the stem is ‘wheelchair’, even though the stem contains two roots.

A base is any form to which affixes of any kind can be added. This means that any root or any stem can be termed a base, but the set of bases is not exhausted by the union of the set of roots and the set of stems: a derivationally analysable form to which derivational affixes are added can only be referred to as a base. That is, ‘touchable’ can act as a base for prefixation to give ‘untouchable’, but in this process ‘touchable’ could not be referred to as a root because it is analysable in terms of derivational morphology, nor as a stem since it is not the adding of inflectional affixes which is in question.

Table of Contents

- Why do stem changing verbs exist in Spanish?

- How do stem changing verbs work in Spanish?

- What is stem example?

- What is a good sentence for stem?

- What does a stem mean in LGBT?

- What is a Chapstick LGBT?

- What is a MASC LGBT?

- What does Butch mean?

- What is a butch queen?

- What is Butch a nickname for?

- Why is a dike?

- How Dyke is formed?

- What is Dyke in Volcano?

- How is a sill formed?

- What is the difference between dyke and sill?

- What does a sill look like?

- How does a volcanic neck form?

- What is a volcanic neck example?

- Can Morro Rock erupt?

In English grammar and morphology, a stem is the form of a word before any inflectional affixes are added. In English, most stems also qualify as words. The term base is commonly used by linguists to refer to any stem (or root) to which an affix is attached.

Why do stem changing verbs exist in Spanish?

Why are some of the Spanish verbs stem-changing? Because of pronunciation changes on the way from Vulgar Latin to Spanish. The vowels E and O “broke”, or turned into diphthongs, in stressed open syllables, but stayed the same in unstressed syllables.

How do stem changing verbs work in Spanish?

Like all other verbs in Spanish, stem-changing verbs are conjugated by removing the –ar, -er or -ir ending from an infinitive and adding the appropriate ending. In the case of stem-changing verbs, there is just one intermediate step: You must also make the appropriate change to the stem.

What is stem example?

The definition of a stem is the main stalk of a plant. An example of stem is the part that holds up the petals on a flower and from which the leaves grow.

What is a good sentence for stem?

2. Her problems stem from her difficult childhood. 3. The stem of the mushroom is broken.

What does a stem mean in LGBT?

Stem – A person whose gender expression falls somewhere between a stud and a femme. (See also ‘Femme’ and ‘Stud’.)

What is a Chapstick LGBT?

In contrast to the more famous descriptor, “lipstick lesbian,” which is often used by or assigned to more feminine appearing-LGBTQIA+ women, some women in the LGBTQIA+ community have adopted and embraced another phrase, “Chapstick lesbian.” This represents their connection to a particular masculine-leaning aesthetic …

What is a MASC LGBT?

Masc/Masculine/ Masculine of Center -set of attributes, society’s expectations behavior that are typically associated with men or boys.

What does Butch mean?

What is butch? Traditionally, in lesbian culture, the word ‘butch’ refers to a woman whose gender expression and traits present as typically ‘masculine’. Being butch is about playing with and challenging traditional binary male and female gender roles and expressions.

What is a butch queen?

Butch Queen: A gay man. Butch Queen In Drag: A gay man who is presenting a female illusion. This description is used for categories in balls for men who dress in drag.

What is Butch a nickname for?

Butch = (Butch is a common nickname used to separate “Sr” from “Jr” mainly in cultures with German backgrounds. Typically the father (Sr) goes by his first name, while the son (Jr) will be referred to as “Butch” by family and friends.)

Why is a dike?

A dike is a barrier used to regulate or hold back water. The dikes along this terraced rice paddy retain water to the plots where rice, a semi-aquatic plant, grows. A dike is a barrier used to regulate or hold back water from a river, lake, or even the ocean.

How Dyke is formed?

When molten magma flows upward through near-vertical cracks (faults or joints) toward the surface and cools, dykes are formed. Dykes are sheet-like igneous intrusions that cut across any layers in the rock they intrude.

What is Dyke in Volcano?

Dikes are tabular or sheet-like bodies of magma that cut through and across the layering of adjacent rocks. They form when magma rises into an existing fracture, or creates a new crack by forcing its way through existing rock, and then solidifies.

How is a sill formed?

Sills: form when magma intrudes between the rock layers, forming a horizontal or gently-dipping sheet of igneous rock.

What is the difference between dyke and sill?

A sill is a concordant intrusive sheet, meaning that a sill does not cut across preexisting rock beds. In contrast, a dike is a discordant intrusive sheet, which does cut across older rocks. Sills are fed by dikes, except in unusual locations where they form in nearly vertical beds attached directly to a magma source.

What does a sill look like?

Sill, also called sheet, flat intrusion of igneous rock that forms between preexisting layers of rock. Sills occur in parallel to the bedding of the other rocks that enclose them, and, though they may have vertical to horizontal orientations, nearly horizontal sills are the most common.

How does a volcanic neck form?

A volcanic plug, also called a volcanic neck or lava neck, is a volcanic object created when magma hardens within a vent on an active volcano. When present, a plug can cause an extreme build-up of pressure if rising volatile-charged magma is trapped beneath it, and this can sometimes lead to an explosive eruption.

What is a volcanic neck example?

A volcanic neck is the “throat” of a volcano and consists of a pipelike conduit filled with hypabyssal rocks. Ship Rock in New Mexico and Devil’s Tower in Wyoming are remnants of volcanic necks, which were exposed after…

Can Morro Rock erupt?

Morro Rock They are the eroded remnants of a chain of ancient volcanoes that erupted between 20 and 26 million years ago. Using radiometric dating methods, Morro Rock has been determined to be about 21 million years old. It is likely that the nine volcanoes erupted along an ancient fault.

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27719

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Your Content Optimization Class is Now in Session!

It has long been known that on-page optimization, which typically focuses on document length and keyword density, can be aided by inclusion of words that are related to the target keyword. Related words aid ranking but can also improve the usefulness of the overall text, its readability, and the degree to which the document appears “natural”. Word Stems represent some of the *most* tightly related words you can pepper into a web page, and deserve close attention when creating content. This posting will explore word stems, how Google uses word stems, and will develop some best practices for utilizing word stems in web content.

What are Word Stems?

Word stems can be thought of as the root for a set of very-similar-meaning words that are in different form. For example: “bats”, “batting”, “batter”, “batted” – all of these share the same stem “bat”, which can be obtained by stripping the suffix characters off of each word (i.e. by stripping the “s” off of “bats”, and so on). However, a stem need not even necessarily be a valid word. For instance, the words “bicycle”, “bicyclist”, and “bicycling” all share the stem “bicycl”, which is clearly not a word. The great thing about stems though is, if you can strip two words down to their stems, and the stems are the same, then the two words must have almost the same meaning and are probably just different forms (plural, adverb, past participle, and so on). If that’s the case, then the words are about as close as you can get from a relevance standpoint; intuitively, the terms “bicycle” and “bicyclist” are more related than “bicycle” and “inner tube”.

The Porter Stemming Algorithm

Various algorithms have been developed for determining the stem of a word (including a surprisingly little-used form of cheating: looking the word up in a dictionary). The most popular stemming algorithm is the Porter stemming algorithm, which is about 85% accurate. In other words, two words that ought to share the same stem are identified by the algorithm to have the same stem about 85% of the time.

The original paper on it can be found here – essentially it is just a set of cascading rules. It’s actually a lot less sophisticated than you might think and its logic is sort of along the lines of “if the word ends in this then do this unless this exception exists”.

Try the Porter Stemming Algorithm for Yourself

You can try it out for yourself below. Note however, after you hit the button you have to scroll *way* down to see the results, the box at the bottom of the fold is *not* the actual results:

Porter Stemming Demo Online

The algorithm usually does pretty well, but an example of two words that it fails on are “squeaking”, which stems to “squeak”, and “squeaky”, which, weirdly and frustratingly, stems to “squeaki” (if anything, you would have thought the other one would have done that(!). There are a few other stemming algorithms around but they’re only a few percent more accurate at best.

Searching and Word Stems

It t is *extremely* common to type one word, and see results come back that include, or are focused on, a variation of that word. You may type “bicycling” and receive documents about “bicyclist”. So an understanding of how Google behaves with regard to word stems, and understanding which variations will help you the most, is critical for content optimization purposes.

The Landmark Study on how Google Handles Stemming

Researchers in Turkey made extensive observations regarding Google’s stemming behavior and published a landmark study on it in 2009 titled “Google Stemming Mechanisms”. It’s not freely available but can be purchased here:

Google Stemming Mechanisms

The study attempted to determine, by analyzing Google SERP results, which word forms were returned for 18,000 different words. They focused in many cases on documents that did *not* have the query term in them but were returned for the query term, and then recorded statistics about these relationships.

The Study’s Methodology

They would first take a page, analyze it and figure out what forms of a term were on it, then run queries against Google to see how it was indexed. For instance, to see if a document containing “cyclist” on “www.foo.com/page1.html” is indexed for the term “cycling” (which let’s assume it does not contain), it could be queried simply with [cycling www.foo.com/page1.html]. They also did some other fancy queries to include and exclude various word forms when investigating singulars and plurals, and multi-word phrases, but you get the general idea.

Is Google Intentionally Handling Stems Differently?

The study speculates about alternate stem-oriented indexes that Google may be maintaining. It’s not clear to me from the paper whether Google is really explicitly targeting word stems with special algorithms, or whether the results are simply a byproduct of the fact that different word forms for the same term are highly related, by definition.

Google has disclosed in papers on their Paid Search technology that they have access to a proprietary algorithm similar to Latent Semantic Analysis; these sorts of algorithms can identify related words based on how frequently words appear together in a corpus (i.e. a set of documents). I’ve seen material put out occasionally by SEOMoz speculating or implying that Latent Dirichlet Allocation may be what Google uses; I think that for the machine learning types in the academic community, LDA has been largely superseded in the last couple of years by Principal Components Analysis.

Regardless of the mechanism, it’s clear that Google looks at how related words are to each other when determining results of a search. Either way, the study found that regardless of whether Google is *intentionally* handling stems differently, stems seem to consistently act differently than other terms.

Let’s Make a Key Assumption Before Proceeding

The study focused on documents that exclusively contained one form versus another – it did not appear to examine documents with mixed forms in them. Let’s assume that the study’s findings can be applied to mixed documents. So, if the study found that documents with [batgirl] were returned for the query term [bat girl], then it’s reasonable to assume that if you’re optimizing your document for [bat girl] you should also throw in the term [batgirl] a few times, as it will probably help. The interpretations and tables I present below are based on that assumption.

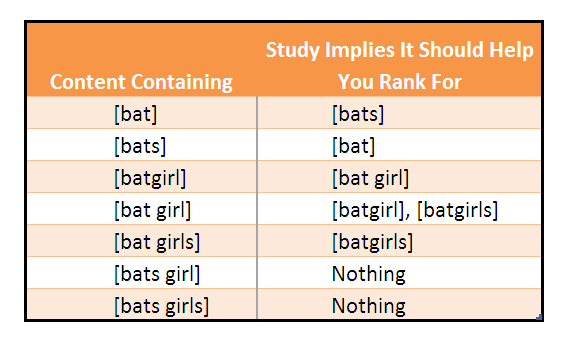

Interpretation #1: Singulars can Help Rank for Plurals and Vice-Versa

The study found that documents with singular forms of keywords tended to come up more often for plural-form queries (about 85% of the time) than did documents with plural forms of keywords came up for singular-form queries (about 59% of the time). For instance, a document with “coconut” would be returned for the query “coconuts” a higher percentage of the time than would a document about “coconuts” being returned for queries about “coconut”. In other words, singular phrases help you rank for plurals more than plurals help you rank for singular phrases. So if you are trying to rank for a plural phrase, including the singular term a few times probably helps. The opposite is also true, but less so according to the percentages. Either way, including the other form some number of times is probably wise.

Interpretation #2: Combined Words can Help Rank for Sub-words

The study also examined combined words, in other words – if your content contains [batgirl] will that help it to rank for “bat”, “girl”, “bats”, “girls”, “batsgirl”, “batgirls”, or “batsgirls” as well? What they found (in our interpretation here) was that content in the form [batgirl] should help you to rank for its direct break-up [bat girl], But [batgirl] will *not* help for inexact break-ups or other plural variations (for instance [bat girls], [bats girl], [bats girls], or [batgirls]).

Interpretation #3: Subwords can Help Rank for Combined Words

Is the converse true though, i.e. should content with [bat girl] help you rank for [batgirl]? Based on the study results – *yes* – and it will also help you rank for [batgirls], but surprisingly, not [batsgirl]. Individual sub-words aid in ranking for their exact combination, and also for the plural version of that combination, but only if the second word in the combined version is the plural one (i.e. [rat nest] will likely not help you rank for [ratsnest] but could help you with [ratnests].

So, by way of corresponding examples we have Table 1, based on the study’s findings and our interpretation of those here. Of course, a term will not just help you rank for another term, it can obviously help rank for itself as well ;-).

- Table 1 – Effect of Plural/Singular Word Combinations

Prove it to Yourself

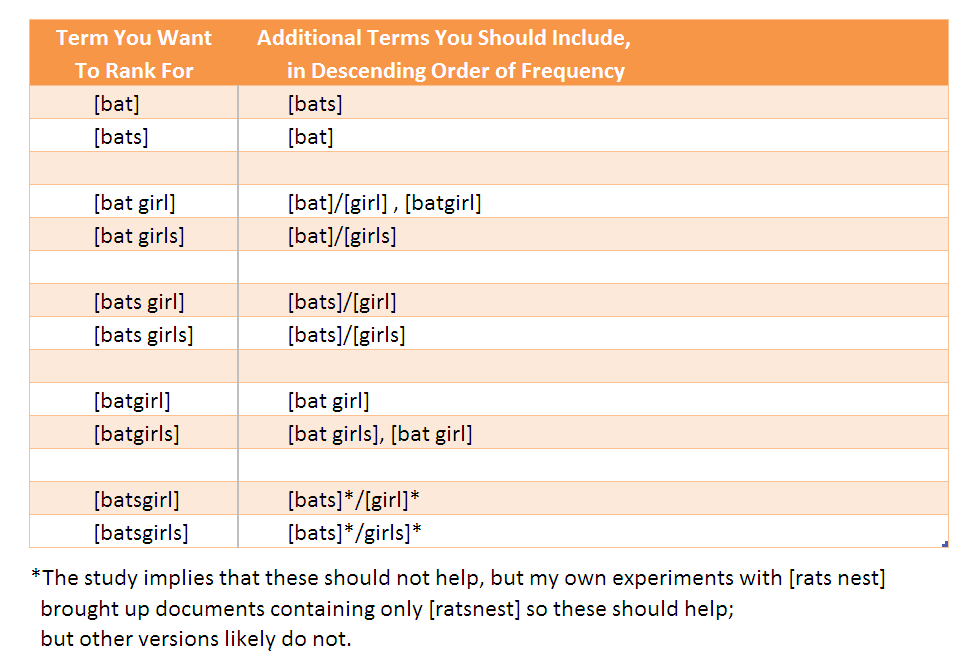

Try it for yourself; for a quick understanding of all of this, try doing queries on Google for [bat girl], [batgirl], [batgirls], and [batsgirl] and see what comes back. You’ll see that Table 1 makes a lot of sense. Table 1 is a little backwards though and not very useful, let’s flip it around and make it more useful in Table 2:

- Table 2 – Best Practice for Singulars, Plurals, and Combination Terms *click to enlarge*

Use Additional Terms In Descending Order of Frequency

For the first additional version, use it 1/4 of the number of times you are using the term you want to rank for, then use ratios of 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 for others (my recommendations base on experience).

Why is the first one X/4? Well,X is too big – you’d then be smearing the relevance of the page out amongst *two* terms, and Google might think your document is not about the main term you’re targeting. So clearly a number smaller than X is the correct one to use. I like X/4 because presumably a natural-appearing distribution should be some sort of long tail geometric distribution, and X/4 is a reasonable guess in that case. Any better suggestions would be gratefully appreciated.

For example, if you want to rank for [bat girl]…

…and keyword frequency analysis of the top ranking pages for that term tells you that you need the term [bat girl] 64 times…

…then also include [bat] 16 times…

…[girl] 16 times…

…and [batgirl] 8 times.

Don’t get hung up on hitting exact numbers though, these are all “ballpark” recommendations.

A *Major* Unanswered Question

However, for those combined word situations , the study only examined *valid* combined words; it left unexplored the question of nonsense combined words. In other words, if you want to rank for [squeaky floor] should you include [squeakyfloor] in the document? This is a *great* question for our industry to explore – I’ve not seen anything on this but surely someone must have tried this! Please comment below if you have seen any evidence on this front.

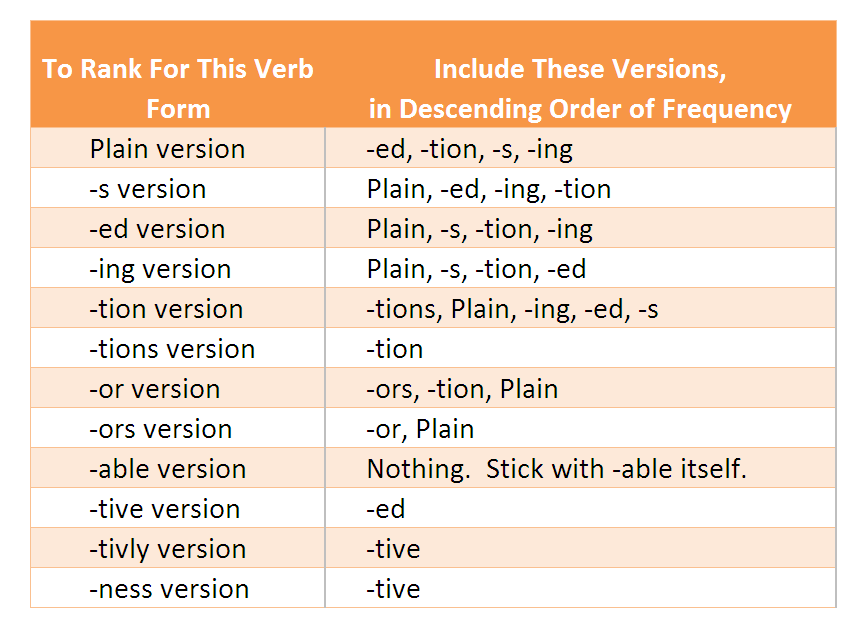

Different Verb Forms

Table 10 of the paper, below, shows the study’s results for twelve different verb forms. Column 1 (on the left) represents documents with the particular verb form; Row 1 (at the top) shows the queries that those documents tended to rank for, and the numbers in the table show the % of the time that they ranked. So, for instance, documents containing “ing” terms (like “boxing”) were returned 38.5% of the time when the query ended in “ed” (like “boxed”):

- Stemming test Results in percentages for 10 different verbs with 12 different postfixes* click to enlarge

*Reprinted Here by Permission of SAGE and Ahmet Uyar.

“Google Stemming Mechanisms”,

Journal of Information Science 35 (5) 2009, pp. 499–514 © Ahmet Uyar

When you look at Table 10, certain combinations really stand out. The top performers (if you look at the rightmost “Average”) column were the Plain Form, the “-ed” form, the “-tion” form, and the “-tive” form. Surprisingly the “-s” form didn’t perform that well (although it performed well in the individual cases “Plain”, “-ed”, and “-ing”, its performance for all the others was abysmal). Note that “-tive” should help you rank for “-tively”, but the converse is oddly not true.

So, the simple takeaway from this table is: pepper the forms (Plain, -ed, -tion, and -tive) into your content. Below is a table if you want to be more systematic about it. I used a value of around 20% in Table 10 as a filter to come up with the table of best practices for verbs below:

- Table 3 – Best Practice for Verb Forms *click to enlarge*

Use the Same Descending Frequency Percentages

For these alternate verb forms I recommend you use the same descending frequency ratios we presented for Table 2 above.

For example, if you want to rank for [creating]…

…and keyword frequency analysis of the top ranking pages for that term

tells you that you need the term [creating] 64 times…

…then also include [create] 16 times…

…[creates] 8 times…

…[creation] 4 times…

…and [created] 2 times.

Again, don’t get hung up on exact numbers, these are rough guidelines.

Why Descending Order and Not Ascending?

An astute reader might question, why do I recommend frequencies descending order and not ascending order (i.e. since intepreting from Table 10, the “-ing” version probably doesn’t help the “Plain” version as much as “-ed” version does, why not have “-ing” appear more frequently in your document, so it can have the opportunity to help as much as “-ed” forms you’re including?). The reason is, it looks to me that the researchers organized the columns in descending order of frequency in documents (i.e. you probably see the “Plain” version of a verb more often than the “-tively” version), and I believe that peppering in these other forms in descending order is the proper thing to do from the standpoint of making the content appear as *natural* as possible. The same logic applies to our Table 2 as well.

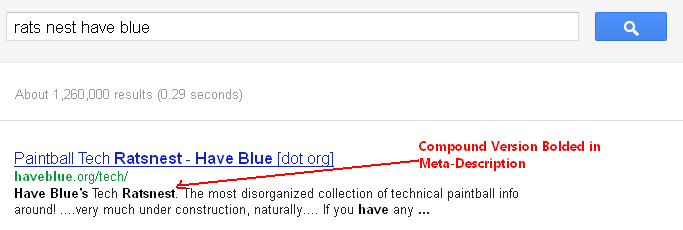

Another Stemming Use: Meta-Tags

Don’t forget to take advantage of word stems in meta-tags. For instance, if you have a page targeting keywords like “Bicycle”, you might use a title like “Bicycle – information on Bicycling”. This way you’re not overloading the title with the same keyword multiple times, but you’re getting a highly related keyword in there. This should hold for all meta-tags including the meta-description. Also, note that Google often highlights different stems or word combinations in the title and meta-description in the SERP (see figure 1):

- Compound Version of Search Term Bolded in Meta-Description *click to enlarge*

Use Stems in Your Keyword Research

The AdWords Keyword Research Tool is absolutely *terrible* at returning alternate word stems. For instance, I did some research recently for a client on “cycling” and came up with thousands of keywords through Adwords – even re-pumping terms back into the tool to find more – but only when I used a third-party keyword tool did I notice the word “cyclist” appear.

I then put that, and a few variations, into the AdWords tool and – voila – hundreds more terms came up that it never suggested in the first place, all highly relevant to what I was researching.

For this reason I *strongly* encourage you use alternate tools in your keyword research to augment it. Even Google suggest itself is a good place to get ideas (in other words, type the stem very slowly and see what comes up). It still fails to bring up “cyclist” for “cycl” but it does suggest a few different stem versions, and correctly extends “squeak” to both “squeaking” and “squeaky”.

You might also try Ubersuggest, it’s an interesting new service that mines Google suggest and presents it in list form; make sure you change it from the default language of “Catalan” into your language of choice first though. Hats off to Dan Shure over at at EvolvingSEO for pointing this tool out to me:

Ubersuggest

Don’t Neglect Other Related Keywords!

Because Google is using this sort of technology, don’t forget to pepper related keywords in addition to stem variations; there are a number of free tools available you can use to analyze SERPs; one I like that I’ve written about before is Textalyser – you can paste a whole bunch of pages into it and it will do frequency counts of all the words, making it very easy to spot good related-word candidates to pepper into your content.

Conclusion

Anyone creating content for the web should have a solid understanding of word stems and should be incorporating both word stems and related keywords into their content and meta-tags as an everyday practice. This should help your documents to rank better, be more interesting for end-users, and look a little more natural (thus better able to withstand “human review” by Google). Best of all, they will help keep your documents from looking a little too keyword-stuffed – by getting the keyword in there a few more times – but in *stealthy* form.