From left to right: a Ming serif typeface with serifs in red, a Ming serif typeface and an East Asian gothic sans-serif typeface

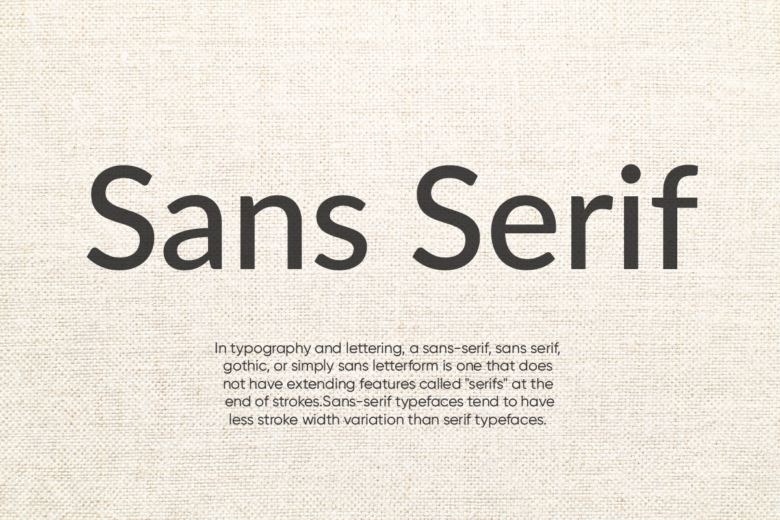

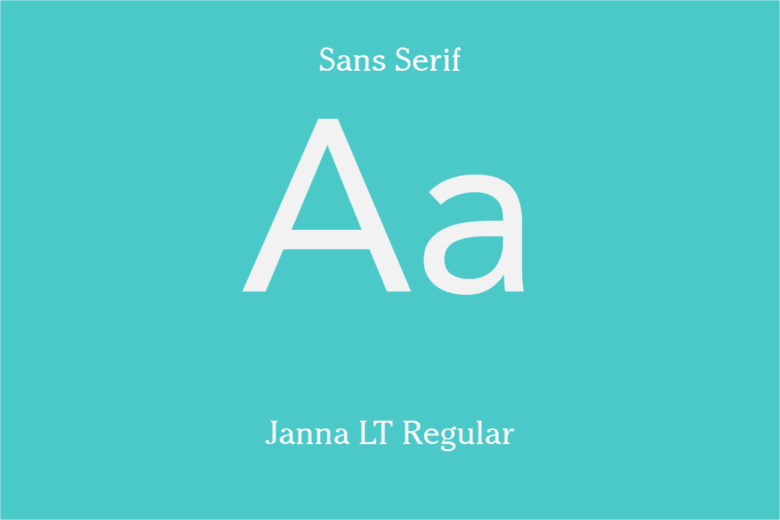

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called «serifs» at the end of strokes.[1] Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism.

Sans-serif typefaces have become the most prevalent for display of text on computer screens. On lower-resolution digital displays, fine details like serifs may disappear or appear too large. The term comes from the French word sans, meaning «without» and «serif» of uncertain origin, possibly from the Dutch word schreef meaning «line» or pen-stroke.[2] In printed media, they are more commonly used for display use and less for body text.

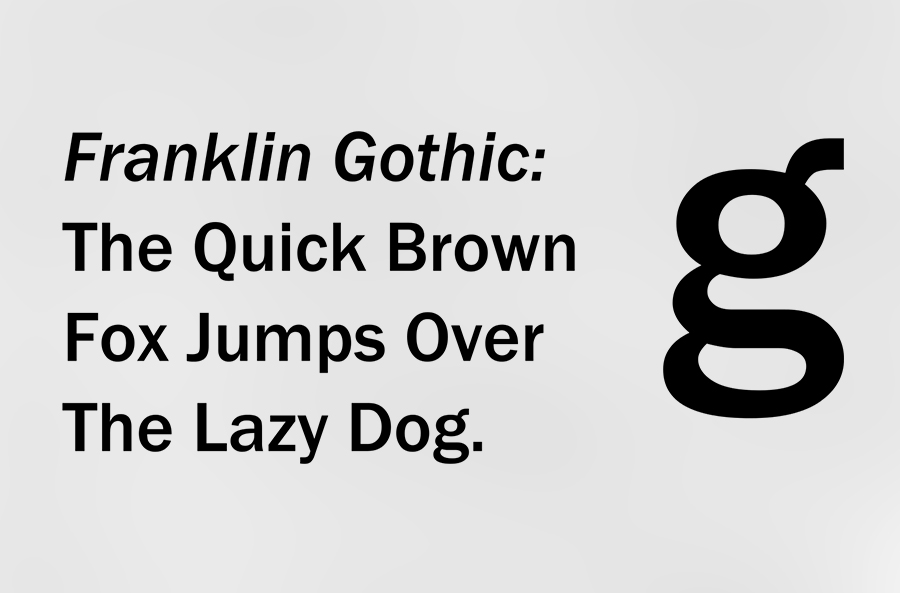

Before the term «sans-serif» became common in English typography, a number of other terms had been used. One of these outmoded terms for sans-serif was gothic, which is still used in East Asian typography and sometimes seen in typeface names like News Gothic, Highway Gothic, Franklin Gothic or Trade Gothic.

Sans-serif typefaces are sometimes, especially in older documents, used as a device for emphasis, due to their typically blacker type color.

Classification[edit]

For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into three or four major groups, the fourth being the result of splitting the grotesque category into grotesque and neo-grotesque.[3][4]

Grotesque[edit]

This group features most of the early (19th century to early 20th) sans-serif designs. Influenced by Didone serif typefaces of the period and sign painting traditions, these were often quite solid, bold designs suitable for headlines and advertisements. The early sans-serif typefaces often did not feature a lower case or italics, since they were not needed for such uses. They were sometimes released by width, with a range of widths from extended to normal to condensed, with each style different, meaning to modern eyes they can look quite irregular and eccentric.[5][6] Grotesque typefaces have limited variation of stroke width (often none perceptible in capitals). The terminals of curves are usually horizontal, and many have a spurred «G» and an «R» with a curled leg. Capitals tend to be of relatively uniform width. Cap height and ascender height are generally the same to produce a more regular effect in texts such as titles with many capital letters, and descenders are often short for tighter line spacing.[7] Most avoid having a true italic in favor of a more restrained oblique or sloped design, although at least some sans-serif true italics were offered.[8][9]

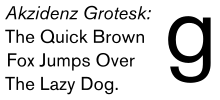

Examples of grotesque typefaces include Akzidenz-Grotesk, Venus, News Gothic, Franklin Gothic and Monotype Grotesque. Akzidenz Grotesk Old Face, Knockout, Grotesque No. 9 and Monotype Grotesque are examples of digital fonts that retain more of the eccentricities of some of the early sans-serif types.[10][11][12][13]

According to Monotype, the term «grotesque» originates from Italian: grottesco, meaning «belonging to the cave» due to their simple geometric appearance.[14] The term arose because of adverse comparisons that were drawn with the more ornate Modern Serif and Roman typefaces that were the norm at the time.[15]

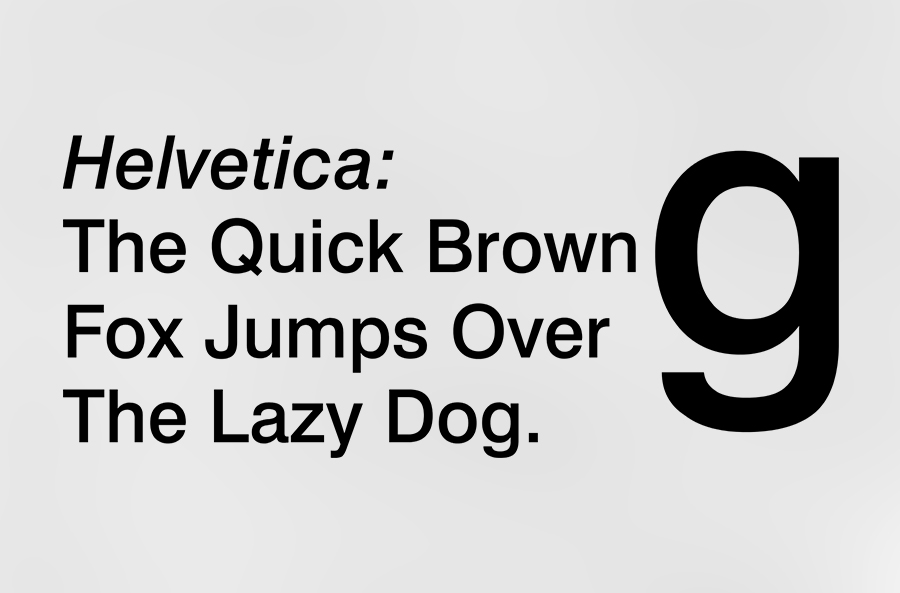

Neo-grotesque[edit]

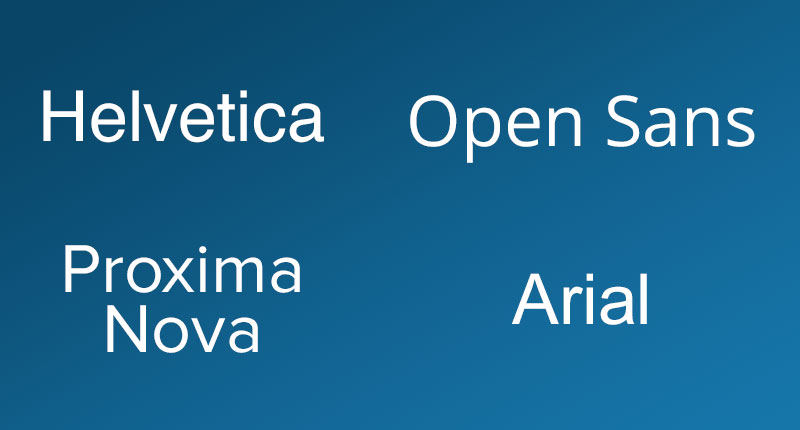

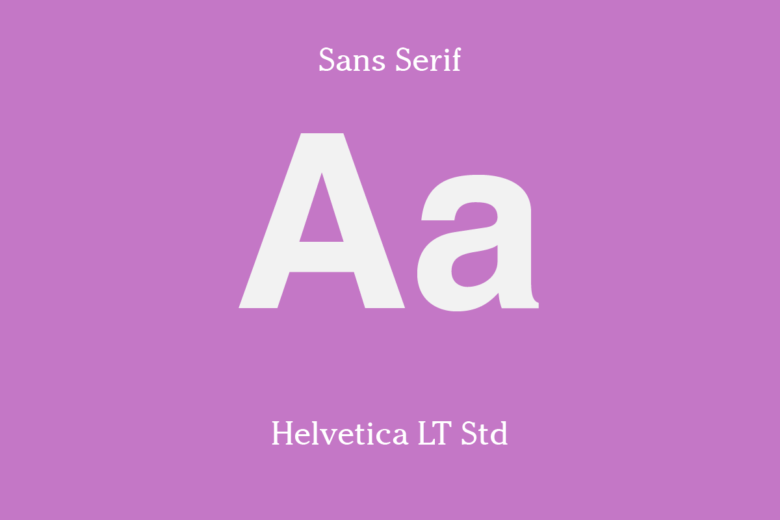

Neo-grotesque designs appeared in the mid-twentieth century as an evolution of grotesque types. They are relatively straightforward in appearance with limited stroke width variation. Similar to grotesque typefaces, neo-grotesques often feature capitals of uniform width and a quite ‘folded-up’ design, in which strokes (for example on the ‘c’) are curved all the way round to end on a perfect horizontal or vertical. Helvetica is an example of this. Unlike earlier grotesque designs, many were issued in large families from the time of release.

Neo-grotesque type began in the 1950s with the emergence of the International Typographic Style, or Swiss style. Its members looked at the clear lines of Akzidenz-Grotesk (1898) as an inspiration for designs with a neutral appearance and an even colour on the page. In 1957 the release of Helvetica, Univers, and Folio, the first typefaces categorized as neo-grotesque, had a strong impact internationally: Helvetica came to be the most used typeface for the following decades.[16][b]

Other, later neo-grotesques include Unica, Imago and Rail Alphabet, and in the digital period Arial, Acumin, San Francisco and Roboto.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

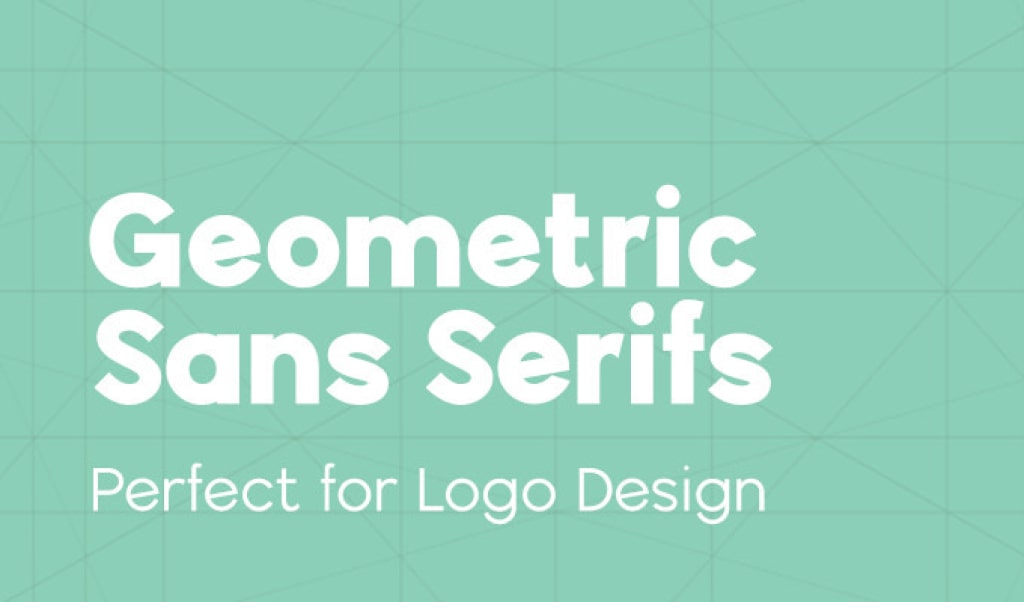

Geometric[edit]

Geometric sans-serif typefaces are based on geometric shapes, like near-perfect circles and squares.[24] Common features are a nearly-circular capital ‘O’, sharp and pointed uppercase ‘N’ vertices, and a «single-storey» lowercase letter ‘a’. The ‘M’ is often splayed and the capitals of varying width, following the classical model.

The geometric sans originated in Germany in the 1920s.[25] Two early efforts in designing geometric types were made by Herbert Bayer and Jakob Erbar, who worked respectively on Universal Typeface (unreleased at the time but revived digitally as Architype Bayer) and Erbar (circa 1925).[26] In 1927 Futura, by Paul Renner, was released to great acclaim and popularity.[27]

Geometric sans-serif typefaces were popular from the 1920s and 1930s due to their clean, modern design, and many new geometric designs and revivals have been developed since.[c] Notable geometric types of the period include Kabel, Semplicità, Bernhard Gothic, Nobel and Metro; more recent designs in the style include ITC Avant Garde, Brandon Grotesque, Gotham, Avenir, Product Sans and Century Gothic. Many geometric sans-serif alphabets of the period, such as those authored by the Bauhaus art school (1919–1933) and modernist poster artists, were hand-lettered and not cut into metal type at the time.[29]

A separate inspiration for many types described «geometric» in design has been the simplified shapes of letters engraved or stenciled on metal and plastic in industrial use, which often follow a simplified structure and are sometimes known as «rectilinear» for their use of straight vertical and horizontal lines. Designs which have been called geometric in principles but not descended from the Futura, Erbar and Kabel tradition include Bank Gothic, DIN 1451, Eurostile and Handel Gothic, along with many of the typefaces designed by Ray Larabie.[30][31]

Humanist[edit]

Humanist sans-serif typefaces take inspiration from traditional letterforms, such as Roman square capitals, traditional serif typefaces and calligraphy. Many have true italics rather than an oblique, ligatures and even swashes in italic. One of the earliest humanist designs was Edward Johnston’s Johnston typeface from 1916, and, a decade later, Gill Sans (Eric Gill, 1928).[32] Edward Johnston, a calligrapher by profession, was inspired by classic letter forms, especially the capital letters on the Column of Trajan.[33]

Humanist designs vary more than gothic or geometric designs.[34] Some humanist designs have stroke modulation (strokes that clearly vary in width along their line) or alternating thick and thin strokes. These include most popularly Hermann Zapf’s Optima (1958), a typeface expressly designed to be suitable for both display and body text.[35] Some humanist designs may be more geometric, as in Gill Sans and Johnston (especially their capitals), which like Roman capitals are often based on perfect squares, half-squares and circles, with considerable variation in width. These somewhat architectural designs may feel too stiff for body text.[32] Others such as Syntax, Goudy Sans and Sassoon Sans more resemble handwriting, serif typefaces or calligraphy.

Frutiger, from 1976, has been particularly influential in the development of the modern humanist sans genre, especially designs intended to be particularly legible above all other design considerations. The category expanded greatly during the 1980s and 1990s, partly as a reaction against the overwhelming popularity of Helvetica and Univers and also due to the need for legible computer fonts on low-resolution computer displays.[36][37][38][39] Designs from this period intended for print use include FF Meta, Myriad, Thesis, Charlotte Sans, Bliss, Skia and Scala Sans, while designs developed for computer use include Microsoft’s Tahoma, Trebuchet, Verdana, Calibri and Corbel, as well as Lucida Grande, Fira Sans and Droid Sans. Humanist sans-serif designs can (if appropriately proportioned and spaced) be particularly suitable for use on screen or at distance, since their designs can be given wide apertures or separation between strokes, which is not a conventional feature on grotesque and neo-grotesque designs.

Other or mixed[edit]

Rothbury, an early modulated sans-serif typeface from 1915. The strokes vary in width considerably.

Due to the diversity of sans-serif typefaces, many do not exactly fit into the above categories. For example, Neuzeit S has both neo-grotesque and geometric influences, as does Hermann Zapf’s URW Grotesk. Whitney blends humanist and grotesque influences, while Klavika is a geometric design not based on the circle. Sans-serif typefaces intended for signage, such as Transport and Highway Gothic (both used on road signs), may have unusual features to enhance legibility and differentiate characters, such as a lower-case ‘L’ with a curl or ‘i’ with serif under the dot.[40]

Modulated sans-serifs[edit]

A particular subgenre of sans-serifs is those such as Rothbury, Britannic, Radiant, and National Trust with obvious variation in stroke width. These have been called ‘modulated’ or ‘stressed’ sans-serifs. They are nowadays[when?] often placed within the humanist genre, although they predate Johnston which started the modern humanist genre. These may take inspiration from sources outside printing such as brush lettering or calligraphy.[41]

History[edit]

Letters without serifs have been common in writing across history, for example in casual, non-monumental epigraphy of the classical period. However, Roman square capitals, the inspiration for much Latin-alphabet lettering throughout history, had prominent serifs. While simple sans-serif letters have always been common in «uncultured» writing and sometimes even in epigraphy, such as basic handwriting, most artistically-authored letters in the Latin alphabet, both sculpted and printed, since the Middle Ages have been inspired by fine calligraphy, blackletter writing and Roman square capitals. As a result, printing done in the Latin alphabet for the first three hundred and fifty years of printing was «serif» in style, whether in blackletter, roman type, italic or occasionally script.

The earliest printing typefaces which omitted serifs were not intended to render contemporary texts, but to represent inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Etruscan. Thus, Thomas Dempster’s De Etruria regali libri VII (1723), used special types intended for the representation of Etruscan epigraphy, and in c. 1745, the Caslon foundry made Etruscan types for pamphlets written by Etruscan scholar John Swinton.[42] Another niche used of a printed sans-serif letterform from 1786 onwards was a rounded sans-serif script typeface developed by Valentin Haüy for the use of the blind to read with their fingers.[43][44][45]

-

A 12th-century[46] Medieval Latin inscription in Italy featuring sans-serif capitals

Developing popularity[edit]

An inscription at the neoclassical grotto at Stourhead in the west of England dated to around 1748 (replica shown),[d] one of the first to use sans-serif letterforms since the classical period[49][50][e][f]

An early 1810 «neoclassical» use of sans-serif capitals to represent antiquity, by William Gell[45][51]

Towards the end of the eighteenth century neoclassicism led to architects increasingly incorporating ancient Greek and Roman designs in contemporary structures. Historian James Mosley, the leading expert on early revival of sans-serif letters, has found that architect John Soane commonly used sans-serif letters on his drawings and architectural designs.[48][52] Soane’s inspiration was apparently the inscriptions dedicating the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy, with minimal serifs.[48] These were then copied by other artists, and in London sans-serif capitals became popular for advertising, apparently because of the «astonishing» effect the unusual style had on the public. The lettering style apparently became referred to as «old Roman» or «Egyptian» characters, referencing the classical past and a contemporary interest in Ancient Egypt and its blocky, geometric architecture.[48][53]

Mosley writes that «in 1805 Egyptian letters were happening in the streets of London, being plastered over shops and on walls by signwriters, and they were astonishing the public, who had never seen letters like them and were not sure they wanted to».[42] A depiction of the style (as an engraving, rather than printed from type) was shown in the European Magazine of 1805, described as «old Roman» characters.[49][54] However, the style did not become used in printing for some more years.[g] (Early sans-serif signage was not printed from type but hand-painted or carved, since at the time it was not possible to print in large sizes. This makes tracing the descent of sans-serif styles hard, since a trend can arrive in the dated, printed record from a signpainting tradition which has left less of a record or at least no dates.)

The inappropriateness of the name was not lost on the poet Robert Southey, in his satirical Letters from England written in the character of a Spanish aristocrat.[56][57] It commented: «The very shopboards must be … painted in Egyptian letters, which, as the Egyptians had no letters, you will doubtless conceive must be curious. They are simply the common characters, deprived of all beauty and all proportion by having all the strokes of equal thickness, so that those which should be thin look as if they had the elephantiasis.»[58][48] Similarly, the painter Joseph Farington wrote in his diary on 13 September 1805 of seeing a memorial[h] engraved «in what is called Egyptian Characters«.[59][48]

Around 1816, the Ordnance Survey began to use ‘Egyptian’ lettering, monoline sans-serif capitals, to mark ancient Roman sites. This lettering was printed from copper plate engraving.[49][45]

Entry into printing[edit]

Around 1816, William Caslon IV produced the first sans-serif printing type in England for the Latin alphabet, a capitals-only face under the title ‘Two Lines English Egyptian’, where ‘Two Lines English’ referred to the typeface’s body size, which equals to about 28 points.[60][61] Although it is known from its appearances in the firm’s specimen books, no uses of it from the period have been found; Mosley speculates that it may have been commissioned by a specific client.[62][i]

A second hiatus in interest in sans-serif appears to have lasted for about twelve years, until Vincent Figgins’ foundry of London issued a new sans-serif in 1828.[64][65][66] David Ryan felt that the design was «cruder but much larger» than its predecessor, making it a success.[67] Thereafter sans-serif capitals rapidly began to be issued from London typefounders.

Much imitated was the Thorowgood «grotesque» face of the early 1830s. This was arrestingly bold and highly condensed, quite unlike the classical proportions of Caslon’s design, but very suitable for poster typography and similar in aesthetic effect to the (generally wider) slab serif and «fat faces» of the period. It also added a lower-case. The term «grotesque» comes from the Italian word for cave, and was often used to describe Roman decorative styles found by excavation, but had long become applied in the modern sense for objects that appeared «malformed or monstrous».[7] The term «grotesque» became commonly used to describe sans-serifs.

Similar condensed sans-serif display typefaces, often capitals-only, became very successful.[48] Sans-serif printing types began to appear thereafter in France and Germany.[68][69]

-

Specimen by William Caslon IV showing his Two Lines English Egyptian sans-serif, the first general-purpose «sans-serif» printing type ever.[70] Cut in only one size, it was apparently not promoted with any prominence.

-

The largest type in this image is the second sans-serif type known, published by Figgins in 1828.[66]

-

Sample image of condensed sans-serifs from the Figgins foundry of London in an 1845 specimen-book. Much less influenced by classical models than the earliest sans-serif lettering, these faces became extremely popular for commercial use.[71]

A few theories about early sans-serifs now known to be incorrect may be mentioned here. One is that sans-serifs are based on either «fat face typefaces» or slab-serifs with the serifs removed.[72][73] It is now known that the inspiration was more classical antiquity, and sans-serifs appeared before the first dated appearance of slab-serif letterforms in 1810.[45] The Schelter & Giesecke foundry also claimed during the 1920s to have been offering a sans-serif with lower-case by 1825.[74][75] Wolfgang Homola dated it in 2004 to 1882 based on a study of Schelter & Giesecke specimens;[76] Mosley describes this as «thoroughly discredited»; even in 1986 Walter Tracy described the claimed dates as «on stylistic grounds … about forty years too early».[45][77]

Sans-serif lettering and typefaces were popular due to their clarity and legibility at distance in advertising and display use, when printed very large or small. Because sans-serif type was often used for headings and commercial printing, many early sans-serif designs did not feature lower-case letters. Simple sans-serif capitals, without use of lower-case, became very common in uses such as tombstones of the Victorian period in Britain.

The first use of sans-serif as a running text has been proposed to be the short booklet Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (Celebration of Life and Art: A Consideration of the Theater as the Highest Symbol of a Culture),[78] by Peter Behrens, in 1900.[79]

-

Simple sans-serif capitals on a late-nineteenth-century memorial, London

-

Italic capitals from the Caslon specimen of 1841

-

Sans-serif type in both upper- and lower-case on a 1914 poster

Twentieth-century sans-serifs[edit]

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sans-serif types were viewed with suspicion by many printers, especially those of fine book printing, as being fit only for advertisements (if that), and to this day[when?] most books remain printed in serif typefaces as body text.[81] This impression would not have been helped by the standard of common sans-serif types of the period, many of which now seem somewhat lumpy and eccentrically-shaped. In 1922, master printer Daniel Berkeley Updike described sans-serif typefaces as having «no place in any artistically respectable composing-room.»[82] By 1937 he stated that he saw no need to change this opinion in general, though he felt that Gill Sans and Futura were the best choices if sans-serifs had to be used.[83]

Through the early twentieth century, an increase in popularity of sans-serif typefaces took place as more artistic sans-serif designs were released. While he disliked sans-serif typefaces in general, the American printer J.L. Frazier wrote of Copperplate Gothic in 1925 that «a certain dignity of effect accompanies … due to the absence of anything in the way of frills», making it a popular choice for the stationery of professionals such as lawyers and doctors.[84] As Updike’s comments suggest, the new, more constructed humanist and geometric sans-serif designs were viewed as increasingly respectable, and were shrewdly marketed in Europe and America as embodying classic proportions (with influences of Roman capitals) while presenting a spare, modern image.[85][86][87][88][89] Futura in particular was extensively marketed by Bauer and its American distribution arm by brochure as capturing the spirit of modernity, using the German slogan «die Schrift unserer Zeit» («the typeface of our time») and in English «the typeface of today and tomorrow»; many typefaces were released under its influence as direct clones, or at least offered with alternate characters allowing them to imitate it if desired.[90][91][92][93]

Grotesque sans-serif revival and the International Typographic Style[edit]

A 1969 poster exemplifying the trend of the 1950s and 1960s: solid red colour, simplified images and the use of a grotesque face. This design, by Robert Geisser, appears to use Helvetica.

In the post-war period, an increase of interest took place in «grotesque» sans-serifs.[94][95][96] Writing in The Typography of Press Advertisement (1956), printer Kenneth Day commented that Stephenson Blake’s eccentric Grotesque series had returned to popularity for having «a personality sometimes lacking in the condensed forms of the contemporary sans cuttings of the last thirty years.»[28] Leading type designer Adrian Frutiger wrote in 1961 on designing a new face, Univers, on the nineteenth-century model: «Some of these old sans-serifs have had a real renaissance within the last twenty years, once the reaction of the ‘New Objectivity’ had been overcome. A purely geometrical form of type is unsustainable.»[97] Of this period in Britain, Mosley has commented that in 1960 «orders unexpectedly revived» for Monotype’s eccentric Monotype Grotesque design: «[it] represents, even more evocatively than Univers, the fresh revolutionary breeze that began to blow through typography in the early sixties» and «its rather clumsy design seems to have been one of the chief attractions to iconoclastic designers tired of the … prettiness of Gill Sans».[42][98]

By the 1960s, neo-grotesque typefaces such as Univers and Helvetica had become popular through reviving the nineteenth-century grotesques while offering a more unified range of styles than on previous designs, allowing a wider range of text to be set artistically through setting headings and body text in a single family.[5][99][100][101][102] The style of design using asymmetric layouts, Helvetica and a grid layout extensively has been called the Swiss or International Typographic Style.

Other names[edit]

Three sans-serif «italics». News Gothic has an oblique.[j] Gothic Italic no. 124, an 1890s grotesque, has a true italic resembling Didone serifs of the period.[8] Seravek, a modern humanist typeface, has a more organic italic which is less folded-up.

Early[edit]

- Egyptian: The name of Caslon’s first general-purpose sans-serif printing type; also documented as being used by Joseph Farington to describe seeing the sans-serif inscription on John Flaxman’s memorial to Isaac Hawkins Brown in 1805,[48] though today[when?] the term is commonly used to refer to slab serif, not sans-serif.

- Antique: Particularly popular in France;[42] some families such as Antique Olive, still carry the name.

- Grotesque: Popularised by William Thorowgood of Fann Street Foundry from around 1830.[7][64][74] The name came from the Italian word ‘grottesco’, meaning ‘belonging to the cave’. In Germany, the name became Grotesk.

- Doric: Used by the Caslon foundry in London

- Gothic: Popular with American type founders. Perhaps the first use of the term was due to the Boston Type and Stereotype Foundry, which in 1837 published a set of sans-serif typefaces under that name. It is believed that those were the first sans-serif designs to be introduced in America.[103] The term probably derived from the architectural definition, which is neither Greek nor Roman,[104] and from the extended adjective term of «Germany», which was the place where sans-serif typefaces became popular in the 19th to 20th centuries.[105] Early adopters for the term includes Miller & Richard (1863), J. & R. M. Wood (1865), Lothian, Conner, Bruce McKellar. Although the usage is now[when?] rare in the English-speaking world, the term is commonly used in Japan and South Korea; in China they are known by the term heiti (Chinese: 黑體), literally meaning «black type», which is probably derived from the mistranslation of Gothic as blackletter typeface, even though actual blackletter typefaces have serifs.

Recents[edit]

- Lineale, or linear: The term was defined by Maximilien Vox in the VOX-ATypI classification to describe sans-serif types. Later, in British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), lineale replaced sans-serif as classification name.

- Simplices: In Jean Alessandrini’s désignations préliminaries (preliminary designations), simplices (plain typefaces) is used to describe sans-serif on the basis that the name ‘lineal’ refers to lines, whereas, in reality, all typefaces are made of lines, including those that are not lineals.[106]

- Swiss: It is used as a synonym to sans-serif, as opposed to roman (serif). The OpenDocument format (ISO/IEC 26300:2006) and Rich Text Format can use it to specify the sans-serif generic typeface («font family») name for the font files used in a document.[107][108][109] Presumably refers to the popularity of sans-serif grotesque and neo-grotesque types in Switzerland.

- Industrial: Used to refer to grotesque and neo-grotesque sans-serifs that are not based on «artistic» principles, as humanist, geometric and decorative designs normally are.[77][110]

Gallery[edit]

This gallery presents images of sans-serif lettering and type across different times and places from early to recent. Particular attention is given to unusual uses and more obscure typefaces, meaning this gallery should not be considered a representative sampling.

-

Dublin 1848, caps-only heading with crossed V-form ‘W’

-

Corset advertisement using multiple grotesque typefaces, United States, 1886

-

Light sans-serif being used for text, Germany, 1914

-

German propaganda poster, 1914

-

Small art-nouveau flourishes on ‘v’ and ‘e’. Ljubljana, 1916.

-

Italic, Dublin, 1916

-

Nearly monoline and stroke-modulated sans; Austrian war bond poster, 1916

-

Broad block capitals. Hungarian film poster, 1918.

-

Monoline sans-serif with art-nouveau influenced tilted ‘e’ and ‘a’. Embedded umlaut at top left for tighter linespacing.

-

Art Deco thick block inline sans-serif capitals, inner details kept very thin. France, 1920s.

-

Artistic sans-serif keeping curves to a minimum (the line ‘O Governo do Estado’), Brazil, 1930

-

Lightly modulated sans-serif lettering on a 1930s poster, pointed stroke endings suggesting a brush

-

Geometric sans-serif capitals, with sharp points on ‘A’ and ‘N’. Australia, 1934.

-

Dwiggins’ Metrolite and Metroblack typefaces, geometric types of the style popular in the 1930s

-

Stencilled lettering apparently based on Futura Black, 1937

-

A 1940s American poster. The curve of the ‘r’ is a common feature in grotesque typefaces, but the ‘single-storey’ ‘a’ is a classic feature of geometric typefaces from the 1920s onwards.

-

1952 Jersey holiday events brochure, using the popular Gill Sans-led British style of the period

-

Swiss-style poster using Helvetica, 1964. Tight spacing characteristic of the period.

-

Ultra-condensed industrial sans-serif in the style of the 1960s; Berlin, 1966

-

Neo-grotesque type, Switzerland, 1972: Helvetica or a close copy. Irregular baseline may be due to using transfers.

-

Tightly-spaced ITC Avant Garde; 1976

-

Governmental poster using Univers, 1980

-

Anti-nuclear poster, 1982

-

1997 film festival poster, Ankara

See also[edit]

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

- Emphasis (typography)

- List of sans serif typefaces

- San Serriffe, an April Fools’ joke by the newspaper The Guardian

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The original metal type of Akzidenz-Grotesk did not have an oblique; this was added in the 1950s, although many sans-serif obliques of the period are similar.

- ^ Digital publishing expert Florian Hardwig describes the main features of neo-grotesques as being «consistent details and even text colour.»[17]

- ^ In this period and since, some sources have distinguished the nineteenth-century «grotesque/gothic» designs from the «sans-serifs» (those now categorised as humanist and geometric both) of the twentieth, or used some form of classification that emphasises a different between the groups.[28]

- ^ The inscription was destroyed by mistake in 1967, and had to be replicated from historian James Mosley’s photographs.[47][48]

- ^ Mosley’s book on early sans-serifs The Nymph and the Grot is named for the sculpture.[49] The name is a dual reference, also to «grotesque» being coincidentally a term also applied to early sans-serif typefaces, although Mosley suggests that the design does not seem to be a direct source of modern sans-serifs.

- ^ The corporate typeface of the National Trust of the United Kingdom, which manages Stourhead, was loosely designed by Paul Barnes based on the inscription.

- ^ Apparently based on traditions in his field of work, master sign-painter James Callingham writes in his textbook «Sign Writing and Glass Embossing» (1871) that «What one calls San-serif, another describes as grotesque; what is generally known as Egyptian, is some times called Antique, though it is difficult to say why, seeing that the letters so designated do not date farther back than the close of the last century. Egyptian is perhaps as good a term as could be given to the letters bearing that name, the blocks being characteristic of the Egyptian style of architecture. These letters were first used by sign-writers at the close of the last century, and were not introduced in printing till about twenty years later. Sign-writers were content to call them “block letters,” and they are sometimes so-called at the present day; but on their being taken in hand by the type founders, they were appropriately named Egyptian. The credit of having introduced the ordinary square or san-serif letters also belongs to the sign-writer, by whom they were employed half a century before the type founder gave them his attention, which was about the year 1810.»[55][48]

- ^ to Isaac Hawkins Browne in the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge

- ^ The matrices used to cast the type also survive, although at least some characters were recut slightly later. Historian John A. Lane, who has examined surviving Caslon specimens and the matrices, suggests that the design is actually slightly earlier and may date to around 1812-4, noting that it appears in some undated but apparently earlier specimens.[63]

- ^ News Gothic’s oblique was actually designed later than the original design, although many nineteenth-century sans-serifs are similar.

References[edit]

- ^ «sans serif» in The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 10, p. 421.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. 2022.

- ^ Childers; Griscti; Leben (January 2013). «25 Systems for Classifying Typography: A Study in Naming Frequency» (PDF). The Parsons Journal for Information Mapping. The Parsons Institute for Information Mapping. V (1). Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Baines, Phil; Haslam, Andrew (2005), Type and Typography, Laurence King Publishing, p. 51, ISBN 9781856694377, retrieved 23 May 2014

In British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), the following are defined:

Grotesque: Lineale typefaces with 19th-century origins. There is some contrast in thickness of strokes. They have squareness of curve, and curling close-set jaws. The R usually has a curled leg and the G is spurred. The ends of the curved strokes are usually oblique. Examples include the Stephenson Blake Grotesques, Condensed Sans No. 7, Monotype Headline Bold.

Neo-grotesque: Lineale typefaces derived from the grotesque. They have less stroke contrast and are more regular in design. The jaws are more open than in the true grotesque and the g is often open-tailed. The ends of the curved strokes are usually horizontal. Examples include Edel/Wotan, Univers, Helvetica.

Humanist: Lineale typefaces based on the proportions of inscriptional Roman capitals and Humanist or Garalde lower-case, rather than on early grotesques. They have some stroke contrast, with two-storey a and g. Examples include Optima, Gill Sans, Pascal.

Geometric: Lineale typefaces constructed on simple geometric shapes, circle or rectangle. Usually monoline, and often with single-storey a. Examples include Futura, Erbar, Eurostile. - ^ a b Shinn, Nick (2003). «The Face of Uniformity» (PDF). Graphic Exchange. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Helvetica alternatives». FontFeed (archived). Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Berry, John. «A Neo-Grotesque Heritage». Adobe Systems. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ a b Specimens of type, borders, ornaments, brass rules and cuts, etc. : catalogue of printing machinery and materials, wood goods, etc. American Type Founders Company. 1897. p. 340. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ «Italic Gothic». Fonts in Use. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. «Knockout». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. «Knockout sizes». Hoefler & Frere-Jones.

- ^ «Knockout styles». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Lippa, Domenic (14 September 2013). «10 favourite fonts». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ «Grotesque Sans». Monotype. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Greta, P (21 August 2017). «What Are Grotesque Fonts? History, Inspiration and Examples». Creative Market Blog. Creative Market. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Meggs 2011, pp. 376–377.

- ^ @hardwig (16 June 2019). «The mid-20th century saw a reappraisal of these classic sans serif forms. Fueled by modernist ideas, they were rethought and redrawn, now with consistent details and even text color. Transferred into systematic families of numerous weights and widths, the neo-grotesque became an essential ingredient of the International Typographic Style» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Adi Kusrianto. Pengantar Tipografi. Elex Media Komputindo. p. 66. ISBN 978-979-27-8132-8.

- ^ Lagerkvist, Love (18 May 2017). «American Football». Fonts In Use. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

Imago [is] a relatively obscure neo-grotesk released by Berthold in the early ’80s.

- ^ Slimbach, Robert. «Using Acumin». Acumin microsite. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Twardoch; Slimbach; Sousa; Slye (2007). Arno Pro (PDF). San Jose: Adobe Systems. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «New Additions: November 2015». Identifont. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ «Fontshop lists: Neo-grotesque». FontShop. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. «A short intro to the geometric sans». FontShop. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. «Types of their time – A short history of the geometric sans». FontShop. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «On Erbar and Early Geometric Sans Serifs». CJ Type. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Meggs 2011, pp. 339–340.

- ^ a b Day, Kenneth (1956). The Typography of Press Advertisement. pp. 86–8.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra (6 January 2012). «True Type of the Bauhaus». Fonts in Use. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Tselentis, Jason (28 August 2017). «Typodermic’s Raymond Larabie Talks Type, Technology & Science Fiction». How. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «Some type genres explained». kupferschrift (blog). Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ a b Tracy 1986, pp. 86–90.

- ^ Nash, John. «In Defence of the Roman Letter» (PDF). Journal of the Edward Johnston Foundation. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Blackwell, written by Lewis (2004). 20th-century type (Rev. ed.). London: Laurence King. p. 201. ISBN 9781856693516.

- ^ Lawson 1990, pp. 326–330.

- ^ Berry, John D. (22 July 2002). «Not Your Father’s Sans Serif». Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Berry, John D. (5 August 2002). «The Human Side of Sans Serif». Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Questioning Gill Sans». Typographica. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «Gill Sans Alternatives». Kupferschrift. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Calvert, Margaret. «New Transport». A2-TYPE. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Identifont blog Feb 15». Identifont. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Mosley, James (6 January 2007), The Nymph and the Grot, an update, archived from the original on 10 June 2014, retrieved 10 June 2014

- ^ «Perkins School for the Blind». Perkins School for the Blind. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Alastair. «Robert Grabhorn Collection on the History of Printing». San Francisco Public Library. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Mosley, James. «Comments on Typophile thread — «Unborn: sans serif lower case in the 19th century»«. Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Le Pogam, Pierre-Yves (2005). De la » Cité de Dieu » au » Palais du Pape «. Rome: École française. p. 375. ISBN 978-2728307296.

- ^ Barnes, Paul. «James Mosley: A Life in Objects». Eye. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mosley 1999, p. 1–19.

- ^ a b c d Mosley 1999.

- ^ John L Walters (2 September 2013). Fifty Typefaces That Changed the World: Design Museum Fifty. Octopus. pp. 1913–5. ISBN 978-1-84091-649-2.

- ^ Gell, William (1810). The Itinerary of Greece. London. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Mosley, James. «The sanserif: the search for examples». Mnémosyne: Base documentaire de l’ésad d’Amiens. ESAD Amiens. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Alexander Nesbitt (1998). The History and Technique of Lettering. Courier Corporation. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-486-40281-9.

- ^ L. Y. (1805). «To the Editor of the European Magazine». European Magazine. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Callingham, James (1871). Sign Writing and Glass Embossing. pp. 54–55.

- ^ L. Parramore (13 October 2008). Reading the Sphinx: Ancient Egypt in Nineteenth-Century Literary Culture. Springer. pp. 22–3. ISBN 978-0-230-61570-0.

- ^ Jason Thompson (30 April 2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology 1: From Antiquity to 1881. The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 251–2. ISBN 978-977-416-599-3.

- ^ Southey, Robert (1808). Letters from England: by Don Manual Alvarez Espriella. D. & G. Bruce, print. pp. 274–5.

- ^ Farington, Joseph; Greig, James (1924). The Farington Diary, Volume III, 1804-1806. London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 109. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of credit : a view of type design. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 9781567922400.

- ^ Tam, Keith (2002). Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century (PDF). Reading: University of Reading (MA thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Simon Loxley (12 June 2006). Type: The Secret History of Letters. I.B.Tauris. pp. 36–8. ISBN 978-1-84511-028-4.

- ^ «The Song of the Sans Serif». The Centre for Printing History and Culture. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b Mosley, James; Shinn, Nick. «Two Lines English Egyptian (comments on forum)». Typophile. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

[T]he Figgins ‘Sans-serif’ types (so called) are well worth looking at. In fact it might be said to be that with these types the Figgins typefoundry brought the design into typography, since the original Caslon Egyptian appeared only briefly in a specimen and has never been seen in commercial use. One size of the Figgins Sans-serif appears in a specimen dated 1828 (the unique known copy is in the University Library, Amsterdam).…It is a self-confident design, which in the larger sizes abandons the monoline structure of the Caslon letter for a thick-thin modulation which would remain a standard model through the 19th century, and can still be seen in the ATF Franklin Gothic. Note that there is no lower-case. That would come, after 1830, with the innovative condensed ‘Grotesque’ of the Thorowgood foundry, which provided a model for type that would get large sizes into the lines of posters. It gave an alternative name to the design, and both the new features – the condensed proportions and the addition of lower-case – broke the link with Roman inscriptional capitals…But the antiquarian associations of the design were still there, at least in the smaller sizes, as the specimen of the Pearl size (four and three quarters points) of Figgins’s type shows. It uses the text of the Latin inscription prepared for the rebuilt London Bridge, which was opened on 1 August 1831.

- ^ Lane, John A.; Lommen, Mathieu; de Zoete, Johan (1998). Dutch Typefounders’ Specimens from the Library of the KVB and other collections in the Amsterdam University Library with histories of the firms represented. De Graaf. p. 15. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

Figgins 1828 [is] one of two known copies, but with the first known appearance of the world’s second sans-serif type, not in the other copy

- ^ a b Barnes, Paul; Schwartz, Christian. «Original Sans Collection: Read the Story». Commercial Classics. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Ryan, David (2001). Letter Perfect: The Art of Modernist Typography, 1896-1953. Pomegranate. ISBN 978-0-7649-1615-1.

- ^ Morlighem, Sébastien. «The Sans Serif in France: The Early Years (1834–44) Sebastien Morlighem ATypI 2019 Tokyo». YouTube. ATypI. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Pané-Farré, Pierre. «Affichen-Schriften». Forgotten Shapes. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Caslon, William (c. 1816). [Specimens of printing types] (untitled specimen book). London: William Caslon IV. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Specimen of Plain & Ornamental Types from the Foundry of V. & J. Figgins. London: V. & J. Figgins Letterfounders. 1846. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Meggs 2011, p. 155.

- ^ Handover, Phyllis Margaret (1958). «Grotesque Letters». Monotype Newsletter. Also Printed in Motif as «Letters Without Serifs»

- ^ a b Lawson 1990, p. 296.

- ^ Handbuch der Schriftarten. Leipzig: Seeman. 1926.

- ^ Homola, Wolfgang. «Type design in the age of the machine. The ‘Breite Grotesk’ by J. G. Schelter & Giesecke» (PDF). University of Reading (archived). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ a b Tracy, Walter. Letters of Credit. p. 98.

- ^ Behrens, Peter (1900), Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (in German), Eugen Diederichs

- ^ Meggs 2011, p. 242.

- ^ Badaracco, Claire (1991). «Innovative Industrial Design and Modern Public Culture: The Monotype Corporation, 1922–1932» (PDF). Business & Economic History. Business History Conference. 20 (second series): 229. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Rogers; Updike; McCutcheon (1939). The work of Bruce Rogers, jack of all trades, master of one : a catalogue of an exhibition arranged by the American Institute of Graphic Arts and the Grolier Club of New York. New York: Grolier Club, Oxford University Press. pp. xxxv–xxxvii.

- ^ Updike, Daniel Berkeley (1922). Printing types : their history, forms, and use; a study in survivals vol 2 (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 243. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Lawson 1990, p. 330.

- ^ Frazier, J.L. (1925). Type Lore. Chicago. p. 20. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ «Fifty Years of Typecutting» (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 39 (2): 11, 21. 1950. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ «Gill Sans Promotional Poster, 1928». Red List. Monotype. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Robinson, Edwin (1939). «Preparing a Railway Timetable» (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 38 (1): 24. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Hewitt, John (1995). «East Coast Joys: Tom Purvis and the LNER». Journal of Design History. 8 (4): 291–311. doi:10.1093/jdh/8.4.291. JSTOR 1316023.

- ^ Horn, Frederick A. (1936). «Type Tactics No. 2: Grotesques: The Sans Serif Vogue». Commercial Art. 20 (132–135): http://magazines.iaddb.org/issue/CAI/1936-04-01/edition/null/page/18.

- ^ Rhatigan, Dan. «Futura: The Typeface of Today and Tomorrow». Ultrasparky. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Aynsley, Jeremy (2000). Graphic Design in Germany: 1890-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 102–5. ISBN 9780520227965.

- ^ Paul Shaw (April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 210–3. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. «From the Archives: Typographic Sanity». Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Gerstner, Karl (1963). «A new basis for the old Akzidenz-Grotesk (English translation)» (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Gerstner, Karl (1963). «Die alte Akzidenz-Grotesk auf neuer Basis» (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Brideau, K.; Berret, C. (16 December 2014). «A Brief Introduction to Impact: ‘The Meme Font’«. Journal of Visual Culture. 13 (3): 307–313. doi:10.1177/1470412914544515. S2CID 62262265.

- ^ Frutiger, Adrian (2014). Typefaces: The Complete Works. p. 88. ISBN 9783038212607.

- ^ Mosley 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. «Helvetica and Univers addendum». Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Christian. «Neue Haas Grotesk». Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ «Neue Haas Grotesk». The Font Bureau, Inc. p. Introduction.

- ^ «Neue Haas Grotesk». History. The Font Bureau, Inc.

- ^ Lawson 1990, p. 295.

- ^ OED Definition of Gothic

- ^ The Sans Serif Typefaces

- ^ Haralambous 2007, p. 411.

- ^ Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) Version 1.2, Part 1: Introduction and OpenDocument Schema, Committee Draft 04, 15 December 2009, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ OpenDocument v1.1 specification (PDF), retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Microsoft Corporation (June 1992), Microsoft Product Support Services Application Note (Text File) — GC0165: RICH-TEXT FORMAT (RTF) SPECIFICATION (TXT), retrieved 13 March 2010

- ^ Handover, Phyllis Margaret. Grotesque letters : a history of unseriffed type faces from 1816 to the present day. OCLC 30233885.

- Bringhurst, Robert (2004), The Elements of Typographic Style (3rd ed.), Hartley & Marks Publishers, ISBN 9780881792065

- Haralambous, Yannis (28 November 2007), Fonts & Encodings, O’Reilly Media, ISBN 9780596102425

- Lawson, Alexander (1990), Anatomy of a Typeface, David R. Godine, Publisher, ISBN 9780879233334

- Lyons, Martyn (2011), Books: A Living History (2nd ed.), Getty Publications, ISBN 9781606060834

- Meggs, Philip B.; Purvis, Alston (2011), Meggs’ History of Graphic Design (5th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 9781118017760

- Tracy, Walter (1986), Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design, David R. Godine, Publisher, ISBN 9780879236366

- Kupferschmid, Indra, Some Type Genres Explained

- Mosley, James (1999). The Nymph and the Grot: the revival of the sanserif letter. London: Friends of the St Bride Printing Library. ISBN 9780953520107.

External links[edit]

- The sanserif: the search for examples (lecture by James Mosley)

- The true source of the sans (lecture to ATypI by Jon Melton)

- The Sans Serif in France: The Early Years (1834–44) (lecture by fr:Sébastien Morlighem)

- Panorama: A reassesment of 19th century poster type (presentation by Pierre Pané-Farré to Ésad Amiens)

- Grotesque: The Birth of The Modern Sans Serif in The Types of The Nineteenth Century (Lecture at Cooper Union by Sara Soskolne)

You’ve undoubtedly heard the terms Serif and Sans-Serif Fonts when it comes to design – but what’s the difference? This post breaks down the key differences between Serif and Sans-Serif fonts and how they came to be. We also look at how you can use them most effectively in your designs and promotions.

In the complex world of typography, it can be hard to know how to use different fonts, let alone what type of “Serif” they are. If you’re a designer, you will understand all of this, but it can be a little confusing for those who haven’t studied or worked in design.

Let’s change that!

While you read this article’s guide to using Serif and Sans-serif fonts – remember that both families of fonts exist within Easil. Our team of Easil Graphic Designers has carefully chosen fonts for you. You can see them in our professionally designed templates and text graphics. So, your job has been made that much easier.

So, now you can get started straight away, playing with different kinds of fonts for your designs!

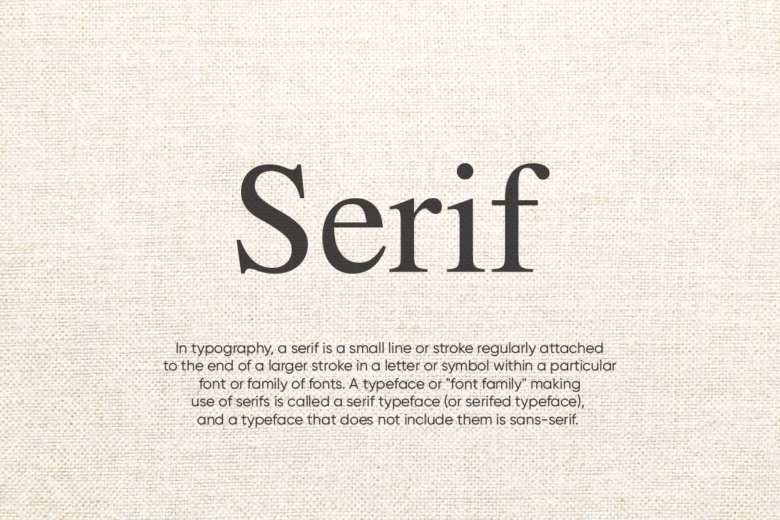

What is the Difference between Serif and Sans-Serif Fonts?

When creating your own text, one of the first decisions to be made is whether to select a font that is Serif or Sans Serif. But what are they, and how do they differ, exactly?

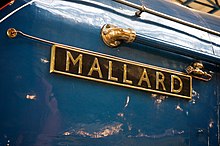

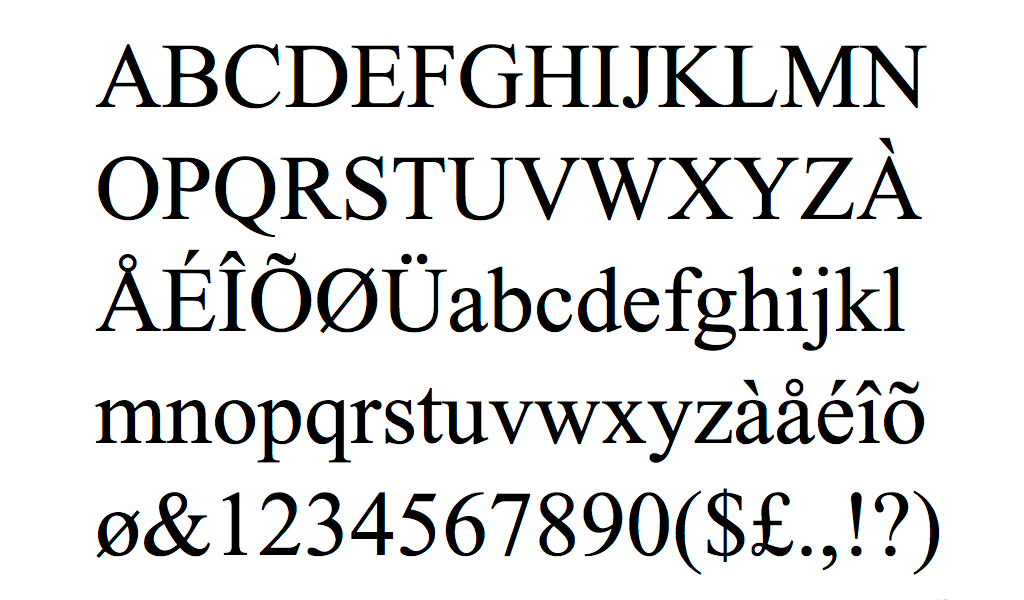

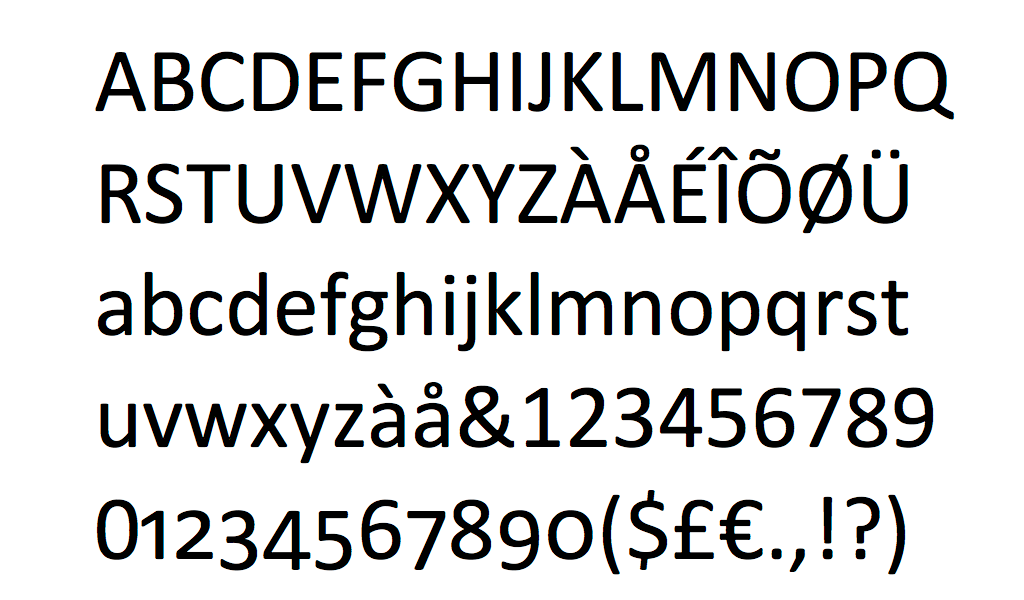

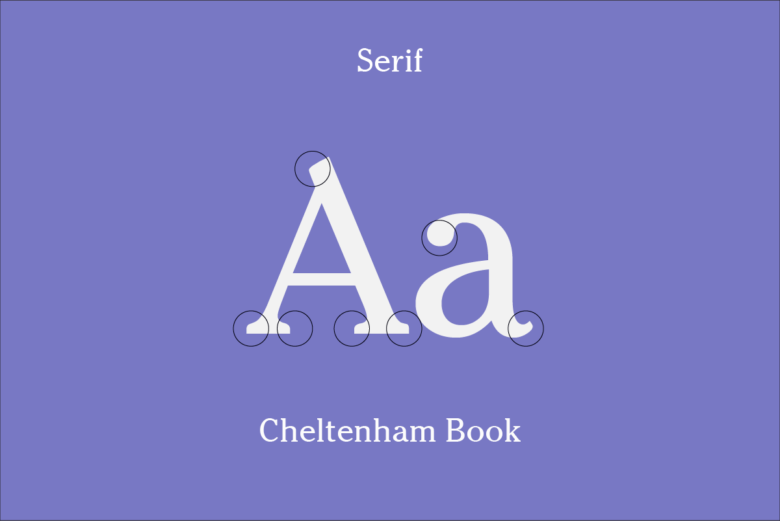

In a nutshell, it’s all about the small features on the ends of strokes in some fonts. Those fonts that have them are called “Serifs” or “Serif fonts.” Those that don’t are called “Sans-Serifs” or “San-Serif Fonts.” Here’s an image showing the difference between Serif and Sans Serif fonts:

Choosing between Serif and Sans Serif Fonts should be based on several considerations pertaining to the project in hand – and the style of design.

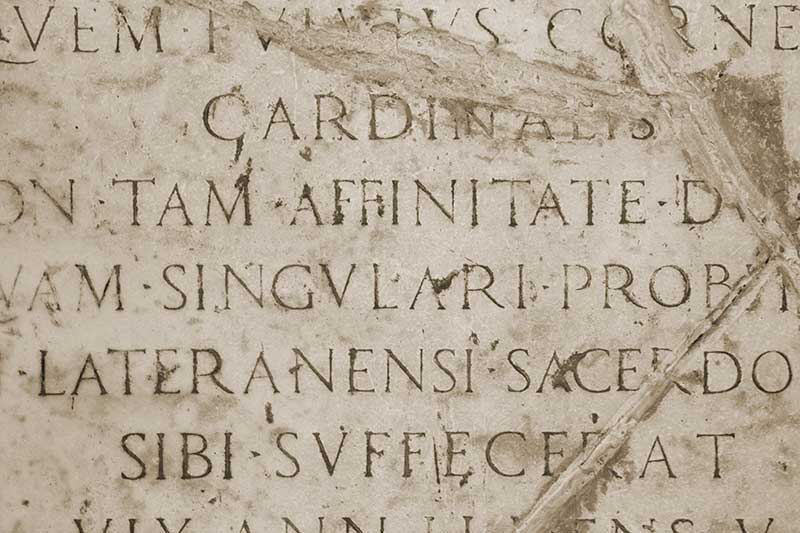

The origin of serifs

Serifs were believed to have originated in the Latin Alphabet with words carved into stone in Roman Antiquity. The Roman letter outlines were first painted onto stone, and the stone carvers followed the brush marks, which flared at stroke ends and corners, creating serifs.

Serif fonts are usually used in lengthy text, such as books, newspapers, and most magazines and are the most commonly used printed typestyle due to perceived readability. After all, when you strive to create something beautiful and remarkable to look at, the main goal is to have your message clear and readable!

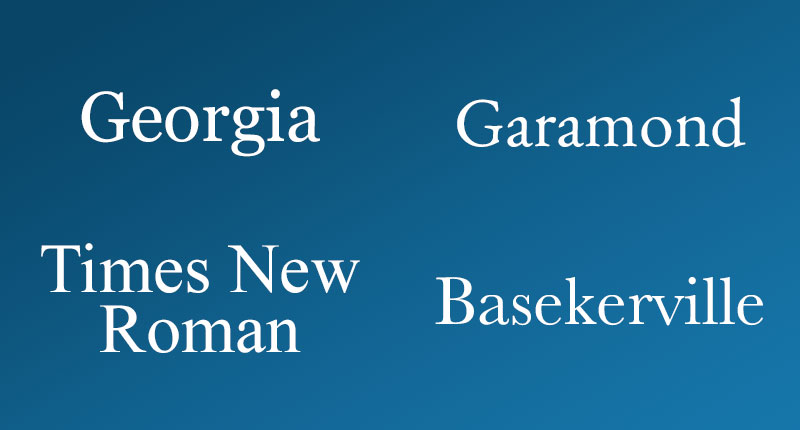

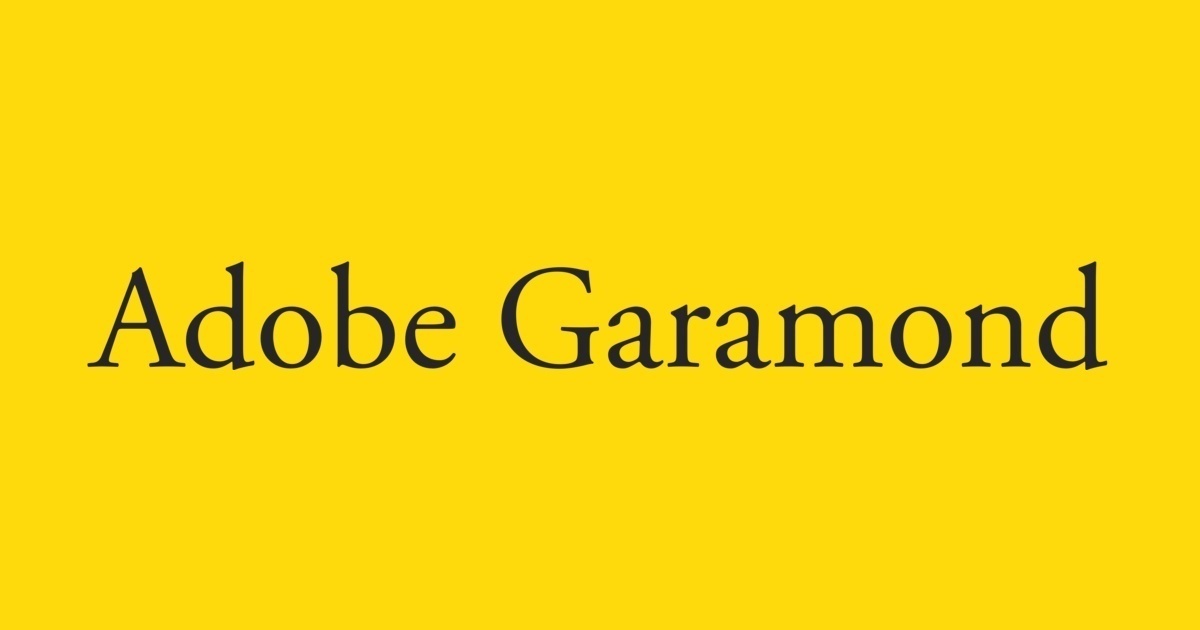

Some common Serif typefaces are Times New Roman, Georgia, Palatino, and Garamond – however, there are thousands more.

The origin of Sans-serif fonts

Sans-serif letters began to appear in printed media as early as 1805. They were popular due to their clarity and legibility in advertising and display use when printed very large or very small.

Sans-serif fonts have become the most prevalent for displaying text on computer screens, partly because screens tend to struggle to show fine serif details in small type.

Some commonly used Sans-serif typefaces are Arial, Helvetica, and Tahoma, but there are thousands more.

Hot Tip: For other shorter text settings – such as titles, credits, column headings, as well as text in infographics – a Sans-serif typeface is a good choice. Its simplified letterforms are unencumbered by Serifs, which can impede the readability of characters at very small sizes.

6 Tips for Using Serif and Sans Serif Fonts Together

- Be Guided by Designers and use Templates – If you’re not a designer, you don’t have to learn how to be one! This means you don’t have to learn how to be the perfect font-pairing master for Serif and Sans Serif fonts. Instead, use font combinations that exist, designed by designers. All you have to do is take advantage of someone else doing all the hard work. For example, use the templates in Easil to find great font combinations that feature Serif and Sans-Serif fonts together.

- Get inspired with Free Fonts. Check out our complete guide to using Free Fonts to find Serif and Sans-Serif Fonts.

- Use our mega Font Pairing Guide. It is perfect for discovering combinations of fonts (including Serif and Sans-Serif fonts) that work together.

- Don’t add too many fonts. Restrict your design to 2 x fonts if possible so that your ratio of Serif vs Sans-Serif fonts can be balanced. One of each should be enough for most designs.

- Consider the “mood” of your fonts. There is a key difference in “mood” between Serif and Sans Serif fonts. Serif fonts tend to be classic or formal. Some might even say they are elegant! Sans Serif fonts are usually described as modern, friendly, and minimal. They are stylishly simplistic in the absence of decorative strokes.

- Determine the font that best suits you. When looking at Serif and Sans Serif fonts, how you use them will vary depending on a number of factors. It depends on the type of project and the mood you want to convey. Things like color and the types of images that you are designing are also worth considering. When it comes to Sans and Sans-Serif fonts, there will always be a difference – but both types of font can be used in a wide number of projects and applications.

Myths about Serif and Sans-Serif Fonts

Although there are guidelines on how to use Serif and Sans-Serif fonts, there are always exceptions to the rule. As such, there are a few myths we should debunk:

- Serif Fonts are More Formal than Sans-Serif – although the “mood” of Serif Fonts can be formal or classic, it’s not clear cut. It’s possible for Sans-Serif fonts also to have the classic feel of yesteryear! When you pair the right type of Serif font with a Sans-Serif, both can be classic!

- Sans Serif Fonts are more suitable for Heading Text – yes, they do suit headings, but there are so many factors that come into play when it comes to “attention-grabbing” fonts. A Serif font can also command attention. Think about traditional newspapers! They often have bold Serif fonts as headings.

- Serifs are for traditional print, and Sans Serifs are for the web – it’s not that black and white. Some Serif typefaces can look beautiful online, and you’ll see many Sans-Serif fonts used effectively in printed material, books, and magazines. Screen resolution has changed, and the way we consume material has changed. It’s all about choosing the right font for the project, so don’t be afraid to debunk a few myths.

Other Related Fonts

Without confusing the issue, many other fonts are used and available in Easil. There are Slab fonts, Handwritten fonts, and Display fonts, the list goes on.

Display fonts are quite ‘unique’ or ‘fancy’ by appearance and are used primarily in large headings and minimal application – you’ll see many of these font families in our post about free fonts here and our post about font pairing here.

In Conclusion

You’ll be spoiled with a number of type styles and font families to choose from in Easil and in our Easil templates. Take advantage of it and use this post to help you determine the most effective use of a Serif or Sans-serif font… or both.

Generally – your message needs to be clear and concise. A Sans-serif font is a good choice for headings and small text where clarity and readability are paramount. A Serif font is good to use on larger blocks of printed text like on a flyer.

But remember to consider the whole context rather than just relying on a set of rules when you make your design choices. Try different font combinations and be creative!

Over to You

Are you all schooled up now in the difference between Sans and Sans Serif Fonts? Ready to rock your designs with fonts?

1. Calibri. Having replaced Times New Roman as the default Microsoft Word font, Calibri is an excellent option for a safe, universally readable sans-serif font.

Furthermore, What does Sans font look like?

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called “serifs” at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces.

Simply so What is the most attractive font?

- 10 of the Most Beautiful Fonts for Web Designers. Design Tips. …

- Playfair. Some looks never go out of fashion. …

- Roboto. Roboto is a sans serif font – it’s geometric with friendly and open curves. …

- Raleway. Raleway is an elegant font with a thin weight – the unique ‘W’ really makes it stand out. …

- Pacifico. …

- Quicksand. …

- Oswald. …

- Lato.

Also, What are the 4 major font types? What are four main types of fonts?

- Serif fonts.

- Sans serif fonts.

- Script fonts.

- Display fonts.

What font is most pleasing to the eye?

Designed for Microsoft, Georgia was actually created with low-resolution screens in mind, so it’s ideal for your desktop and mobile site visitors alike.

- Helvetica.

- PT Sans & PT Serif.

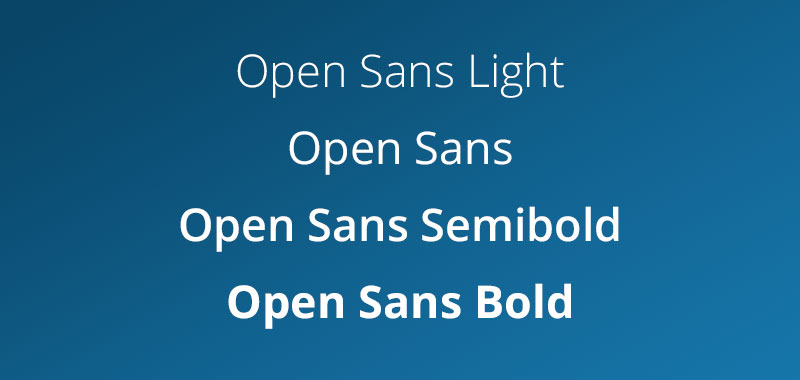

- Open Sans.

- Quicksand.

- Verdana.

- Rooney.

- Karla.

- Roboto.

Why are sans serif fonts easier? Sans is a French word meaning “without”. Thus, a sans serif is a typeface that has no traces or lines extending from the edges of letters and alphabets. This way, there are no curls, and the sans serif letters appear simple and rounded. The Sans font is clean and the best font for reading on screen.

Why is sans serif better?

Sans-Serif have slightly increased readability compared to Serifs. Which is why Sans-Serif is a great typeface for the body of text. Don’t combine a Serif with a Serif and a Sans-Serif with a Sans-Serif because it can look a little bland and undifferentiated. Too many fonts in one design is not a good thing.

The most popular serif fonts are Times New Roman, Arial, Georgia, Garamond, and Didot (to name a few). These fonts are often pre-installed in computers, making them an easy default choice.

What are the most hated fonts?

My top 10 most loathed fonts as a graphic designer!

- Hobo.

- Scriptina. …

- Times New Roman. …

- Arial. …

- Bradley Hand. …

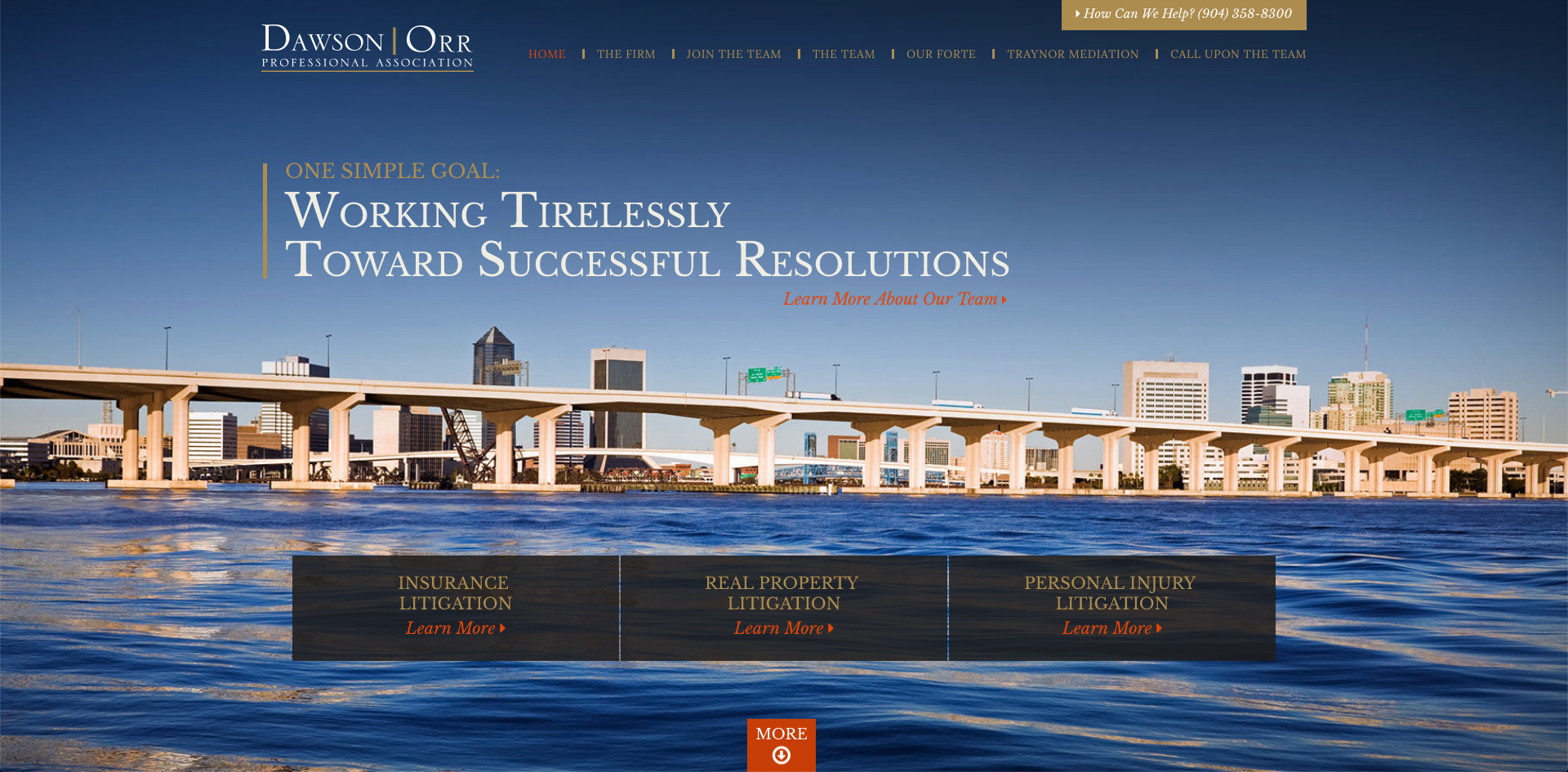

- Copperplate Gothic. If I see another law firm/accounting agency/corporate business use this font in their branding, it’ll be too soon! …

- Trajan. “In a world…” …

- Courier. This is just one of the ugliest fonts every created! …

What is the most annoying font?

Comic Sans: The most annoying font in the world Back to video. Even if you didn’t know what it was called, you will be familiar with Comic Sans. Comic Sans is type that has gone wrong.

Why is Arial bad?

Arial and Helvetica are the default font stack for most browsers and for most of the websites. That’s bad, really really bad. Arial and Helvetica suck on web and for paragraphs of text – they are unreadable (as compared to many other typefaces created specifically for web).

What are 3 common font styles?

They appear in order of popularity.

- Helvetica. Helvetica remains the world’s most popular font. …

- Calibri. The runner up on our list is also a sans serif font. …

- Futura. Our next example is another classic sans serif font. …

- Garamond. Garamond is the first serif font on our list. …

- Times New Roman. …

- Arial. …

- Cambria. …

- Verdana.

What is the oldest font?

Why Trajan, the World’s Oldest Typeface, Still Matters. “Red Cross 90th anniversary stamp, 1957. It was the last stamp design of nearly 500 done by [Jan] van Krimpen.”

What font is fastest to read?

Multiple studies, like the one conducted by Sarah Morrison and Jan Noyes of the University of Bristol, have found that Times New Roman is the best typeface for reading any document. Readers speed through material faster thanks to its simple letters.

What is the cleanest font?

Here are a few of the best free fonts for clean & modern logo design & branding.

- Montserrat.

- Nexa (Light & Bold only) Full family here.

- Bebas Neue.

- Exo 2.

- Raleway.

- Roboto.

- Open Sans.

- Titillium Web.

What is the easiest to read font?

What Is the Easiest Font to Read? (10 Top Options)

- Arial. Arial is the standard font for many word processors, such as Microsoft Word and Google Docs. …

- Helvetica. Another old-school sans-serif typeface you may want to consider is Helvetica. …

- Georgia. …

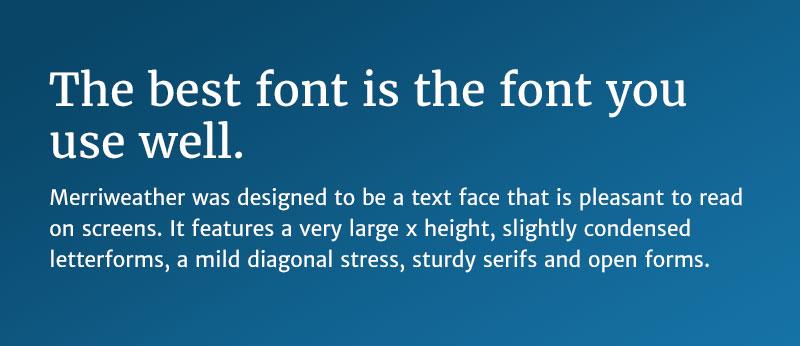

- Merriweather. …

- Montserrat. …

- Futura. …

- Open Sans. …

- Lato.

What is the hardest font to read?

What is the hardest font to read on Google Docs?

- Papyrus.

- Comic Sans.

- Calibri.

- Brush Script.

- Verdana. You know how I know Verdana is terrible?

- Lucida Calligraphy. “Oh yeah, THAT font.” Lucida Calligraphy is under-the-radar terrible.

- Times New Roman. Let’s get this one out of the way.

What is the easiest text to read?

What Is the Easiest Font to Read? (10 Top Options)

- Arial. Arial is the standard font for many word processors, such as Microsoft Word and Google Docs. …

- Helvetica. Another old-school sans-serif typeface you may want to consider is Helvetica. …

- Georgia. …

- Merriweather. …

- Montserrat. …

- Futura. …

- Open Sans. …

- Lato.

Why do typefaces have serifs?

Serifs give the eye a curve to hug. When carved into stone, serifs allow words to appear aligned. Hence, the Victorians used serifs in all of their typefaces, and they were common in Italian Renaissance architecture. They were seen as “Roman.” Today, the names of computerized fonts (Times New Roman, Comic Sans, etc.)

Is serif or sans serif easier to read dyslexia?

In a classic study about which fonts are easier to read for people who have dyslexia, researchers found these three typeface characteristics significantly improved readability: Sans-serif.

What is the hardest to read font?

What is the hardest font to read on Google Docs?

- Papyrus.

- Comic Sans.

- Calibri.

- Brush Script.

- Verdana. You know how I know Verdana is terrible?

- Lucida Calligraphy. “Oh yeah, THAT font.” Lucida Calligraphy is under-the-radar terrible.

- Times New Roman. Let’s get this one out of the way.

Which is the most attractive font?

Beautiful Internet: 10 of the Best Fonts for the Web

- Alternate Gothic.

- Open Sans. …

- Alegreya. …

- Titillium Sans and Dosis. …

- Merriweather. …

- Yellowtail. …

- Playfair Display. Playfair is a unique font, created by Claus Eggers Sørensen. …

- Arvo. Arvo is a very good slab serif font family, created by Anton Koovit. …

What is the most classy font?

The following serif fonts will undoubtedly give an elegant appeal to your works, and best of all, you can download them free of charge.

- EB Garamond. …

- Playfair Display. …

- Crimson Text. …

- Old Standard. …

- Cormorant. …

- Libre Baskerville. …

- Caudex. …

- Spectral.

Is times a serif font?

Times New Roman is a serif typeface. It was commissioned by the British newspaper The Times in 1931 and conceived by Stanley Morison, the artistic adviser to the British branch of the printing equipment company Monotype, in collaboration with Victor Lardent, a lettering artist in The Times’s advertising department.

What are sans serif fonts? Most people who work with a computer are used to reading these names (serif, sans-serif, sans…) on their font list when editing a text document on a word processor or using image edition software to add some text to a photograph.

But for designers, knowing more than the font names are essential.

Sans serif fonts, then, are the ones that don’t have these ornamental lines in them. They started being widely used during the 1920s Bauhaus movement. They were seen as more modern and informal than the usual fonts with serifs that we still see in print and screens.

Today, these sans serif fonts are used in blogs and online articles in newspapers with large bodies of text because their legibility on-screen is excellent. They are also used in small texts, titles, captions… Almost everywhere!

The sans-serif fonts are classified into three or four groups (depending on if you split the last category into grotesque and neo-grotesque or not). Let’s learn about the particularities of each one of them!

See also: 20 Best Creative Custom Fonts PowerPoint Design

Why do typefaces matter?

When you’re writing a marketing pamphlet or creating a poster, the typeface you choose may seem of little importance. But in reality, typefaces make a big impact in conveying your message and capturing the attention of your target audience. Choose the wrong typeface, and your project may not achieve its intended purpose. On the other hand, when you choose a suitable typeface, your message will be more effective and easier to read.

Guide to choosing a typeface

Now you can answer the question, “What are serif and sans serif?” but you may still be wondering how to choose the suitable typeface for your next project. Here are a few tips to help you narrow down your options.

Consider your brand

The quickest way to choose a typeface is to consider your brand’s style using actionfonts.com. Are you youthful and energetic? Or formal and refined? Do you want to show off your modern aesthetic or create an air of authority? As we’ve already discussed, serif and sans serif typefaces give off a completely different vibe, so it’s essential to choose the typeface that matches your brand.

Don’t overdo it

It’s easy to get excited about all your typeface options, but it’s usually best to stick with just one or two fonts per project. Using too many typefaces will confuse the reader and leave your brand lacking a cohesive, recognizable style.

Feel free to mix and match

Though you probably don’t want to choose more than a few typefaces for your project, you should feel free to mix serif and sans serif fonts. Selecting only one typeface category may look a little bland. Choose one typeface for titles and another typeface for the body paragraph to maximize readability and add interest.

Typeface categories

Understanding the connotation of each typeface category can help you choose the right one for your next project. But if you’re used to scrolling through your typeface options and selecting one at random, you may need a more extensive introduction.

There are essentially three different categories of typefaces: serif, sans serif, and script. We’ll dive into the differences between each typeface category below. But for now, it’s essential to keep in mind that since there are thousands upon thousands of typefaces available, being able to decide if you need a serif, sans serif, or script typeface ahead of time will significantly help you in your search.

Once you’ve decided on the particular mood or emotions, you want to evoke with your content, you can match that up with a typeface. Different styles of type create different moods. You need to make sure you’re picking one that matches the tone of your content.

So, what are sans serif fonts? What about serif fonts? How do they differ, and how can you tell them apart?

Sans Serif

Sans serif typefaces are considered more modern than serif typefaces. They lack the strokes that distinguish a serif typeface, hence using the French word “sans,” which means “without.” Sans serif typefaces are often used to signify something clean, minimal, friendly, or modern.

Some of the most popular sans serif typefaces are Arial, Helvetica, Open Sans, Calibri, and Verdana. Sans serif fonts are often used on the web for large text groups because of the lower DPI (dots per inch) that screens have compared to print. Sans serif fonts are generally easier for children to read because they’re simpler.

See also: 20 Best Fonts for Professional PowerPoint: Adios! You Won’t See Arial and Times New Roman Anymore

When is a Sans Serif typeface right for you?

If you want to convey a friendly, approachable vibe, a sans-serif typeface may be the best choice. Many companies choose sans serif typefaces when they want to be seen as young, hip, and casual. Start-up and technology companies often use this category of typeface to convey their relatability and cutting-edge style. As we mentioned above, this is also the preferred font style for designing websites, thanks to the increased readability.

Types of Sans Serif fonts

There are three main types of sans-serif fonts: humanist, transitional, and geometric.

Humanist Sans Serif

Humanist sans serif typefaces emulate calligraphy and have minimalist contrasting strokes. The design of these typefaces is suitable for small text and small text, so they’re often used in government, education, or finance work. Gill Sans and Whitney are considered Humanist sans serif typefaces.

The earliest designs were inspired by classic letters like Roman square capitals. Their designs are more varied than the other categories.

Transitional Sans Serif

Transitional sans serif typefaces have strong strokes and more upright and uniform characters than Humanist typefaces. Their natural and modern feel works great for tech and transportation writing.

Grotesque Style, the first sans serif designs found from the 19th century to the early 20th. They were solid designs, suitable for advertisements, titles, and posters. The terminals of the curves in these fonts are usually horizontal, and there’s a slight variation in the width of the strokes.

This was the evolution of the previous type, the grotesque. They also have limited variation, but they were more versatile and were very useful for readable bodies of text. They often feature a “folded up”-like design, where the strokes curve and end with horizontal and vertical lines.

Geometric Sans Serif

Geometric sans serif typefaces use geometric shapes to form the backbones of the letters, which creates a strict, objective, and universal feel. The letterforms are often simple. Such letters like “a” with an opening would be circular or square and then repeated with other letters with the same type of opening.

These typefaces have in common that they are designed after geometric elements, such as circles and squares. They became very popular during the 20s and 30s because their design was perceived as modern and clean.

See also: Font Pairing Tips and Tricks for Dummies

Serif

What is a serif font? This typeface is recognizable by the little lines or strokes that extend from letters. As you can see in the text above, the “i” and “f” have distinguishable feet. The “S” also extends down and up at the ends.

When is a Serif typeface right for you?

Serif typefaces are some of the older typefaces. Their mood is often classic, romantic, elegant, formal, and established because of their age. Some well-known serif typefaces include Times New Roman, Georgia, and Garamond.

Many people believe that serif typefaces should be proper in printed works because the little serifs make it easier and quicker to identify the different letters, but that might not necessarily be true.

In any case, serif fonts are a good choice when you want your message to convey experience and trustworthiness. Many brands choose serif fonts because they believe it gives customers more confidence in their brand and gives them a better reputation than brands that use sans serif fonts.

See also: The Only Guide You Need to Download and Install Fonts for Professional PowerPoint

Types of Serif fonts

There are three different kinds of serif typefaces: humanist, transitional, and slab serif. There are also a few more categories of serif typefaces, like Renaissance, baroque, modern, and wedge, but we’ll focus on the three listed previously.

Humanist Serif

Humanist serif typefaces emulate classical calligraphy with contrasting strokes. These typefaces were the first Roman typefaces. Other characteristics of Humanist typefaces are small x-height and low contrast between strokes.

You’ll often see classic and traditional content printed with a humanist serif typeface, like books and articles.

Transitional Serif

Transitional serif typefaces have sharper serifs and more contrasting strokes to create a solid and dynamic style and are often used in law or academics. The influence of a pen has gone with Transitional typefaces. An example of this is the vertical stress in the bowls of letters, meaning the thinnest part of the letter.

In the Humanist typefaces, the vertical stress is actually on a diagonal since that’s how the vertical pressure of a letter generally is when words are handwritten. Georgia and Baskerville are Transitional serif typefaces.

Slab Serif

Slab Serif, or Egyptian or square serif, typefaces have heavy and boxy serifs with almost no contrast in the letter’s strokes.

This creates a friendly yet authoritative feel, like in a marketing application. New typefaces were very suitable for advertising and such, so a bolder typeface was important.

See also: How to Embed Fonts in PowerPoint into Various Platforms

Serif vs. Sans Serif fonts

When it comes to choosing serif vs. sans serif fonts, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. “When it comes to typography, there’s no one right way,” says Young.

The best font for you and your brand will entirely depend on what you want your designs to say to your audience. Here are a few things to keep in mind when choosing fonts for your brand:

Choose a font that feels you uniquely

Serif and sans serif fonts can both be equally effective—the key is to choose a font that feels you uniquely. “Both typefaces have their place in logo design, but the decision on which to use should be made thoughtfully,” says Downey. “Your font choice should accurately reflect your brand’s personality.”

Think about where and how people are going to interact with your brand

Choosing a font style that feels on-brand is essential, but choosing a type that makes sense on the mediums and platforms people will use to interact with your brand. “Serifs are naturally easier for the eye to read quickly and we can find this typeface in most books and newspapers,” says Downey. “Sans-serifs on the other hand, mainly dominate the digital world on websites and apps.”

“For brands that intentionally want their aesthetic to feel classic and aren’t as worried about how the branding with appear on a screen, a sophisticated font is a great choice,” says Young. “Brands that want a modern aesthetic that scales well at different sizes and is easy to read on screens are going to choose sans serif for their main branding elements.”

Don’t get stuck in the “serif = traditional, sans serif = modern” mindset

Generally speaking, serif fonts are more traditional, while sans-serif fonts have a more modern feel. But there are exceptions to every rule. “Although the rule of thumb is that sans-serif equals modern and serif equals traditional, we need to break those design stereotypes,” says Downey. So, depending on how you use your fonts, you can create a modern look using serif fonts—or a more traditional feel with sans serif fonts.

Let’s visit RRSlide to download free PowerPoint templates. But wait, don’t go anywhere and stay here with our RRGraph Design Blog to keep up-to-date on the best pitch deck template collections and design advice from our PowerPoint experts.

What is a sans serif font? What is the difference between serif and sans serif fonts? These are just some of the questions we will be answering today in this short article.

Then we will share some terrific examples of sans serif fonts you can find at Envato Elements.

What Is a Sans Serif Font?

Let’s start by answering what font is sans serif? Serifs are small lines or strokes attached to the end of the main vertical and horizontal strokes of some letters. And the word sans is French for without. So sans serif fonts are fonts without serifs.

What Is the Difference Between Serif and Sans Serif Fonts?

If you want to learn more about the difference between serifs and sans serifs, check out the video below:

Pop Quiz

Which of the following describes sans serif fonts?

- a font without serifs

- a font with serifs

Is Calibri a sans serif font?

- No

- Yes

**Answers at the end of the article.

Sans Serif Font Examples

Though sans serifs possess the same common feature of having no serifs, they do come in a wide range of styles. Let’s check out some examples of sans serif fonts.

Hoglar Sans Display (OTF, TTF)

Hoglar Sans Display is bold and striking, making it perfect for branding, movie and book titles, signage, and more. Hoglar includes both upper and lowercase characters, numbers, and punctuation, as well as multilingual support.

Confillia Sans Serif (OTF)

Confillia is a wonderful sans serif that offers four styles: normal, italic, bold, and bold italic. The font includes upper and lowercase characters, numbers, punctuation, symbols, and multilingual support.

Stark: A Modern Sans Serif (OTF)

If you are looking for a clean, modern, minimalist font, then Stark is a great choice for you. This terrific sans serif is perfect for both headers and body text. It comes in five weights, with five italic styles.

Arubi Sans Serif Font

Arubi is a cool and contemporary font that’s an excellent choice for branding and editorial projects. This display font offers stylish uppercase letters only.

Sprout Sans Serif (OTF)

This slender and condensed font is a great choice when you need an elegant and delicate font for your stationary, titling, product labelling and more.

Heroes Sans Serif (OTF, TTF, WOFF)

Sans serif fonts can be as exciting as you need them to be. And when you need a sans serif with a bit of pizzazz, you can’t go wrong with Heroes, a condensed sans serif font that is fun and eye-catching. Use Heroes when you need a display font for your album covers, logos, branding, magazine covers, social media, etc.

Nickels Bold Sans Serif (OTF, TTF)