Word Meaning Lecture # 6 Grigoryeva M.

Word Meaning Approaches to word meaning Meaning and Notion (понятие) Types of word meaning Types of morpheme meaning Motivation

Each word has two aspects: the outer aspect ( its sound form) cat the inner aspect (its meaning) long-legged, fury animal with sharp teeth and claws

Sound and meaning do not always constitute a constant unit even in the same language EX a temple a part of a human head a large church

Semantics (Semasiology) Is a branch of lexicology which studies the meaning of words and word equivalents

Approaches to Word Meaning The Referential (analytical) approach The Functional (contextual) approach Operational (information-oriented) approach

The Referential (analytical) approach formulates the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denote distinguishes between three components closely connected with meaning: the sound-form of the linguistic sign, the concept the actual referent

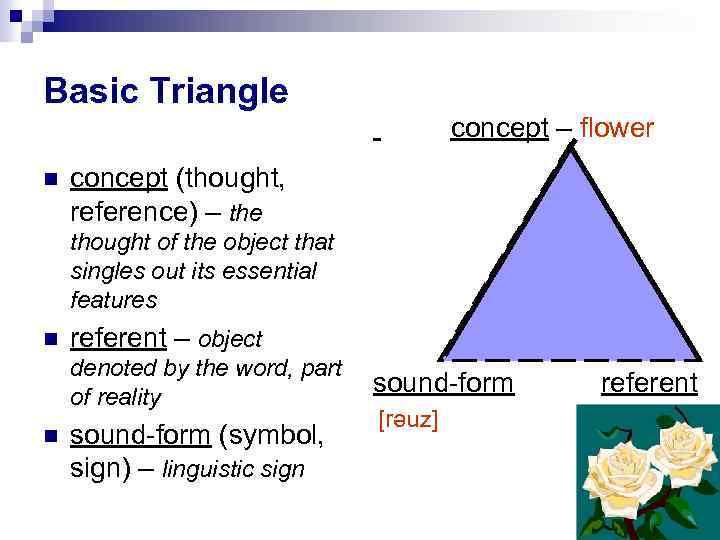

Basic Triangle concept – flower concept (thought, reference) – the thought of the object that singles out its essential features referent – object denoted by the word, part of reality sound-form (symbol, sign) – linguistic sign sound-form [rәuz] referent

In what way does meaning correlate with each element of the triangle ? • In what relation does meaning stand to each of them? •

Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove — [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian [taube] German sound-forms BUT the same meaning

Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot] Russian – a male cat [kot] English – a small bed for a child identical sound-forms have different meanings (‘homonyms) EX. knight [nait]

Meaning and Sound-form even considerable changes in sound-form do not affect the meaning EX Old English lufian [luvian] – love [l Λ v]

Meaning and Concept concept is a category of human cognition concept is abstract and reflects the most common and typical features of different objects and phenomena in the world meanings of words are different in different languages

Meaning and Concept identical concepts may have different semantic structures in different languages EX. concept “a building for human habitation” – English Russian HOUSE ДОМ + in Russian ДОМ “fixed residence of family or household” In English HOME

Meaning and Referent one and the same object (referent) may be denoted by more than one word of a different meaning cat pussy animal tiger

Meaning is not identical with any of the three points of the triangle – the sound form, the concept the referent BUT is closely connected with them.

Functional Approach studies the functions of a word in speech meaning of a word is studied through relations of it with other linguistic units EX. to move (we move, move a chair) movement (movement of smth, slow movement) The distriution ( the position of the word in relation to others) of the verb to move and a noun movement is different as they belong to different classes of words and their meanings are different

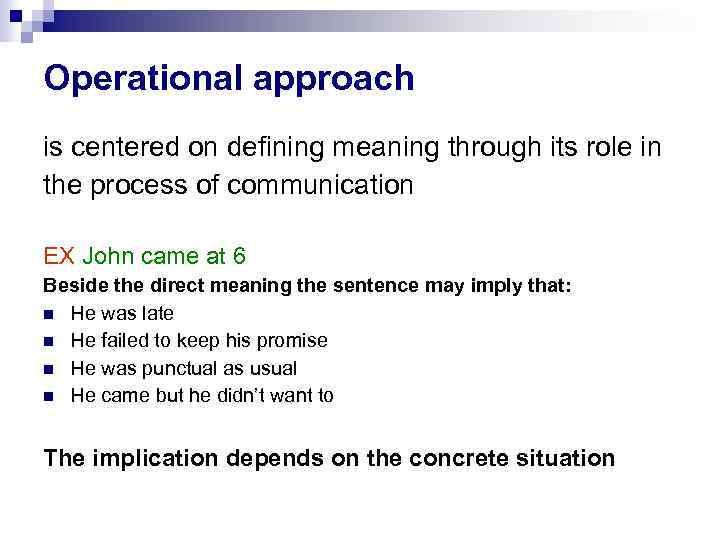

Operational approach is centered on defining meaning through its role in the process of communication EX John came at 6 Beside the direct meaning the sentence may imply that: He was late He failed to keep his promise He was punctual as usual He came but he didn’t want to The implication depends on the concrete situation

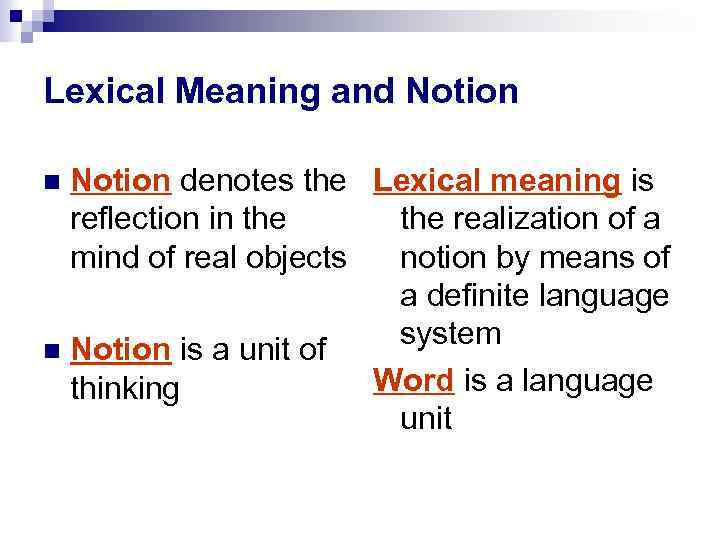

Lexical Meaning and Notion denotes the Lexical meaning is reflection in the realization of a mind of real objects notion by means of a definite language system Notion is a unit of Word is a language thinking unit

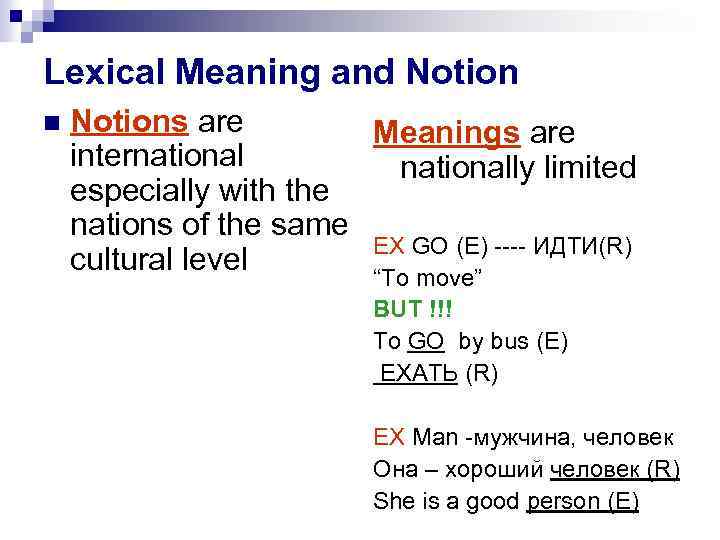

Lexical Meaning and Notions are Meanings are internationally limited especially with the nations of the same EX GO (E) —- ИДТИ(R) cultural level “To move” BUT !!! To GO by bus (E) ЕХАТЬ (R) EX Man -мужчина, человек Она – хороший человек (R) She is a good person (E)

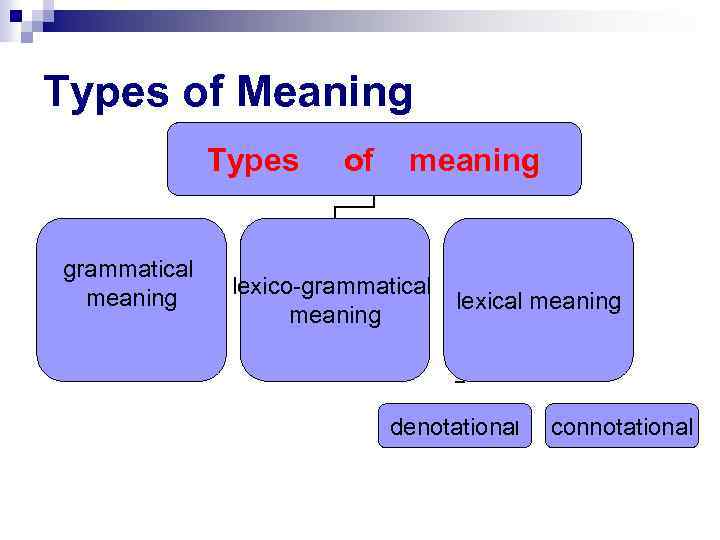

Types of Meaning Types grammatical meaning of meaning lexico-grammatical meaning lexical meaning denotational connotational

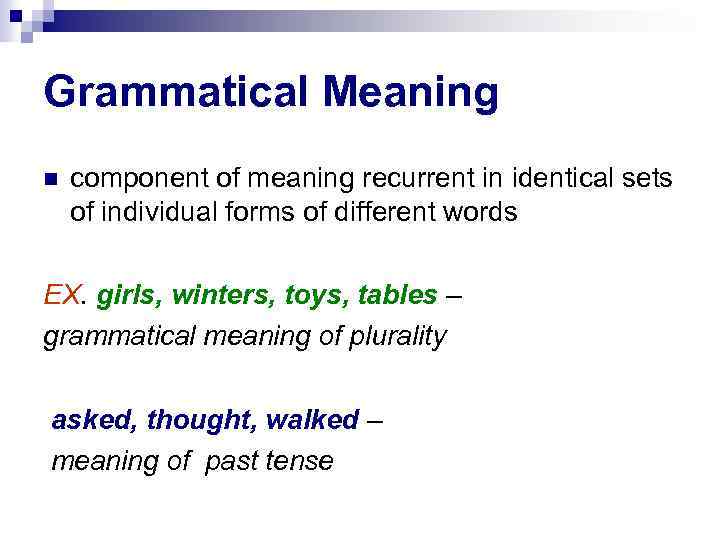

Grammatical Meaning component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words EX. girls, winters, toys, tables – grammatical meaning of plurality asked, thought, walked – meaning of past tense

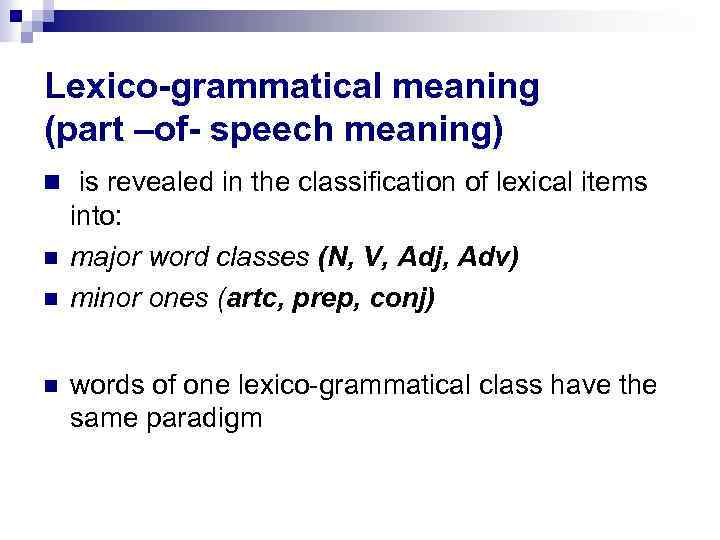

Lexico-grammatical meaning (part –of- speech meaning) is revealed in the classification of lexical items into: major word classes (N, V, Adj, Adv) minor ones (artc, prep, conj) words of one lexico-grammatical class have the same paradigm

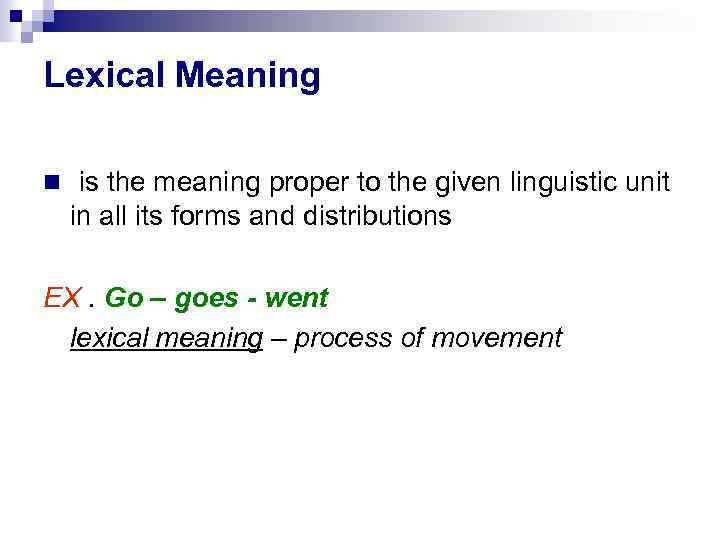

Lexical Meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions EX. Go – goes — went lexical meaning – process of movement

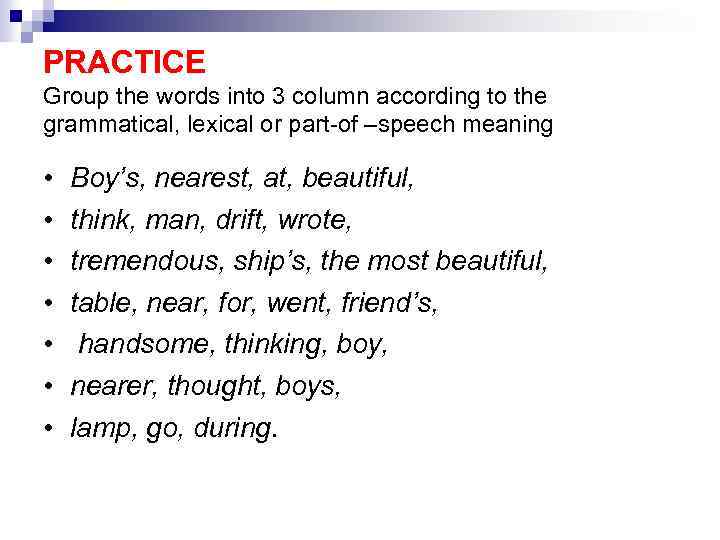

PRACTICE Group the words into 3 column according to the grammatical, lexical or part-of –speech meaning • • Boy’s, nearest, at, beautiful, think, man, drift, wrote, tremendous, ship’s, the most beautiful, table, near, for, went, friend’s, handsome, thinking, boy, nearer, thought, boys, lamp, go, during.

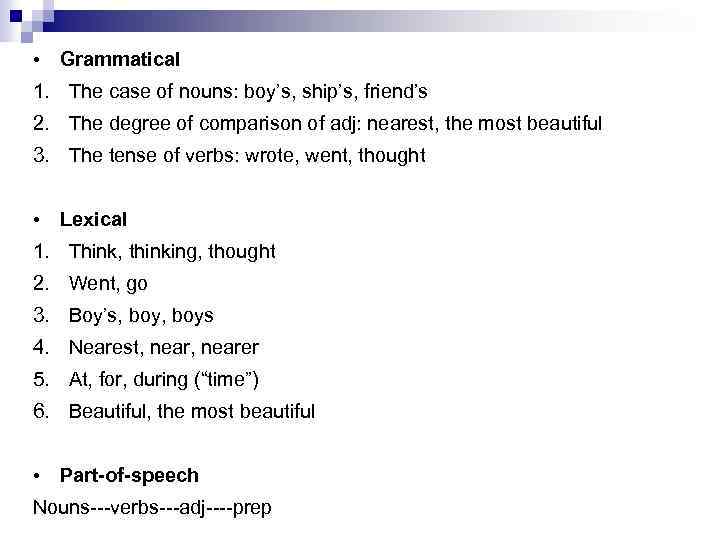

• Grammatical 1. The case of nouns: boy’s, ship’s, friend’s 2. The degree of comparison of adj: nearest, the most beautiful 3. The tense of verbs: wrote, went, thought • Lexical 1. Think, thinking, thought 2. Went, go 3. Boy’s, boys 4. Nearest, nearer 5. At, for, during (“time”) 6. Beautiful, the most beautiful • Part-of-speech Nouns—verbs—adj—-prep

Aspects of Lexical meaning The denotational aspect The connotational aspect The pragmatic aspect

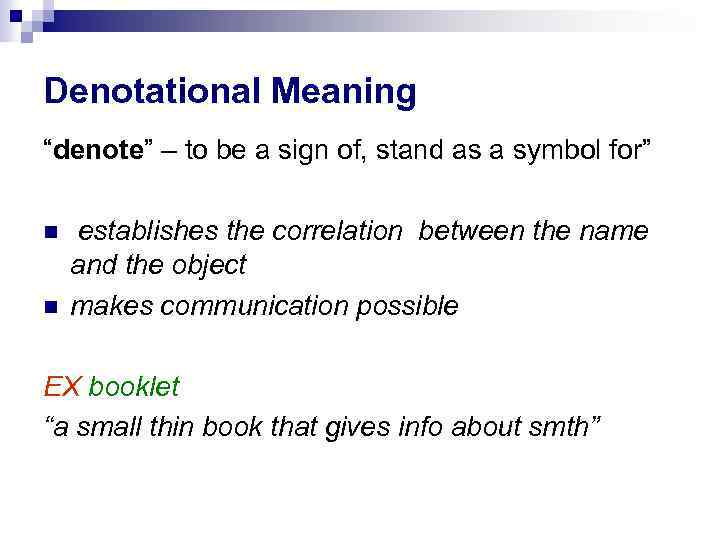

Denotational Meaning “denote” – to be a sign of, stand as a symbol for” establishes the correlation between the name and the object makes communication possible EX booklet “a small thin book that gives info about smth”

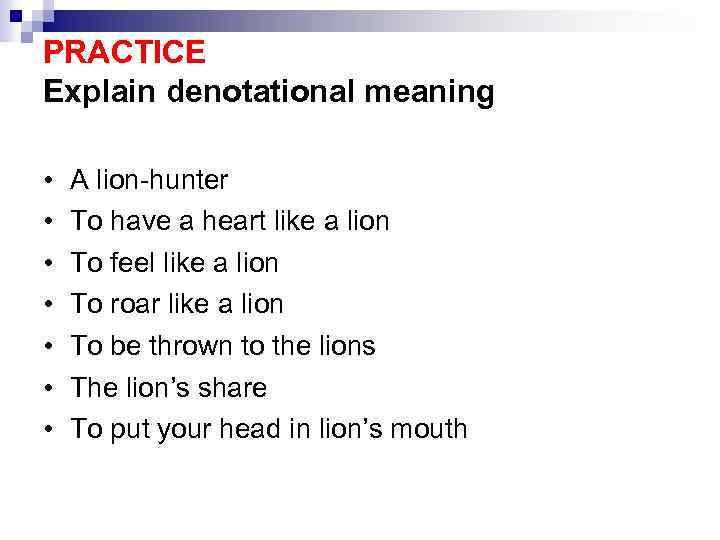

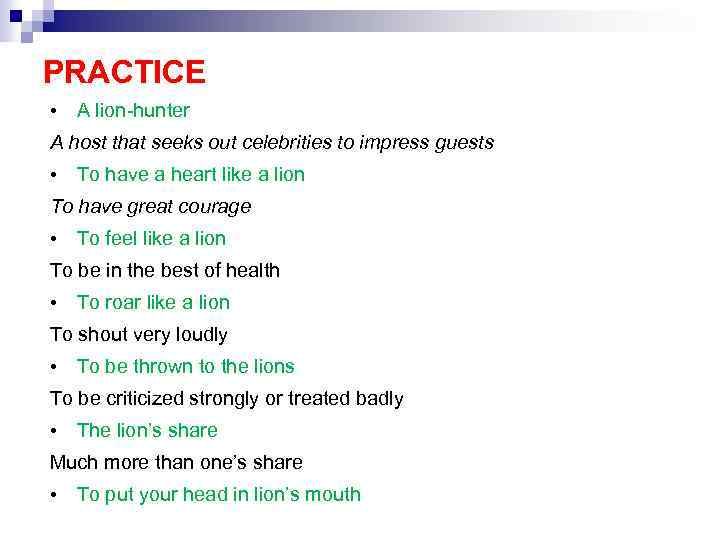

PRACTICE Explain denotational meaning • • A lion-hunter To have a heart like a lion To feel like a lion To roar like a lion To be thrown to the lions The lion’s share To put your head in lion’s mouth

PRACTICE • A lion-hunter A host that seeks out celebrities to impress guests • To have a heart like a lion To have great courage • To feel like a lion To be in the best of health • To roar like a lion To shout very loudly • To be thrown to the lions To be criticized strongly or treated badly • The lion’s share Much more than one’s share • To put your head in lion’s mouth

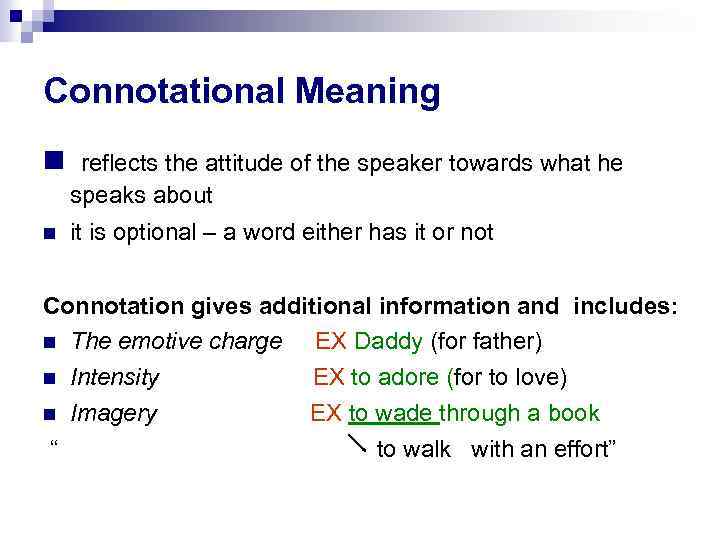

Connotational Meaning reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about it is optional – a word either has it or not Connotation gives additional information and includes: The emotive charge EX Daddy (for father) Intensity EX to adore (for to love) Imagery EX to wade through a book “ to walk with an effort”

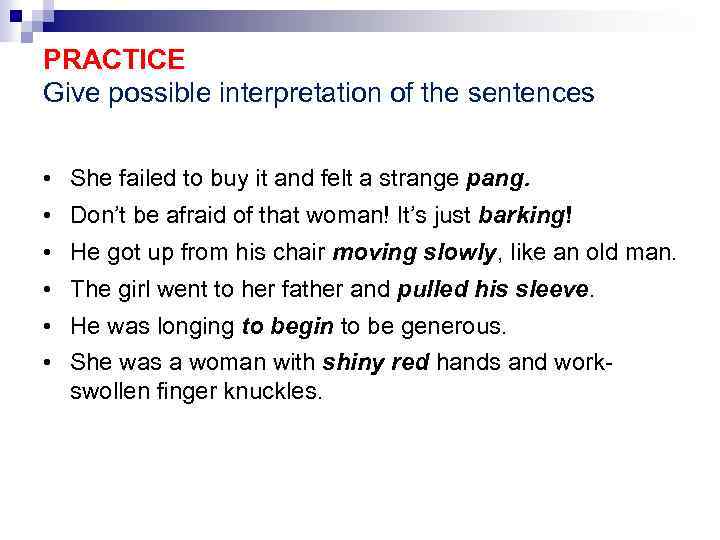

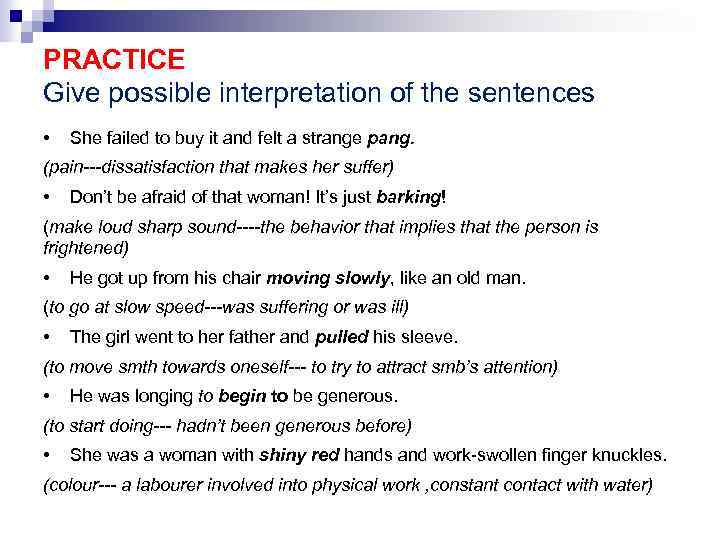

PRACTICE Give possible interpretation of the sentences • She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang. • Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking! • He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man. • The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve. • He was longing to begin to be generous. • She was a woman with shiny red hands and workswollen finger knuckles.

PRACTICE Give possible interpretation of the sentences • She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang. (pain—dissatisfaction that makes her suffer) • Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking! (make loud sharp sound—-the behavior that implies that the person is frightened) • He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man. (to go at slow speed—was suffering or was ill) • The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve. (to move smth towards oneself— to try to attract smb’s attention) • He was longing to begin to be generous. (to start doing— hadn’t been generous before) • She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles. (colour— a labourer involved into physical work , constant contact with water)

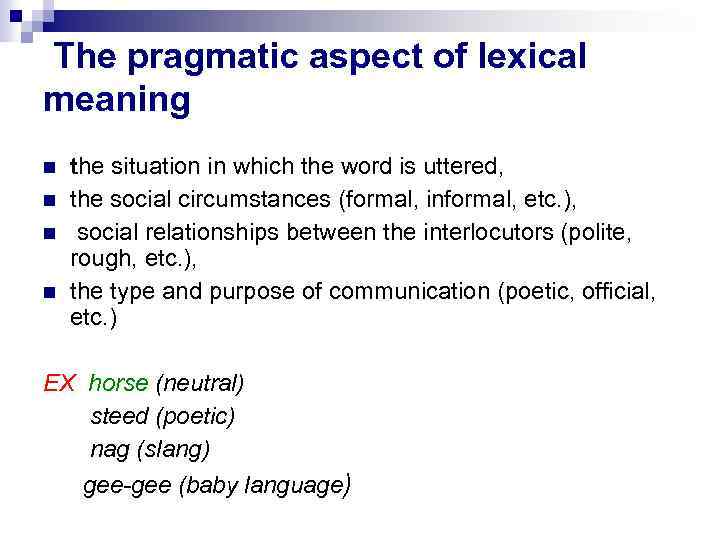

The pragmatic aspect of lexical meaning the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, informal, etc. ), social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough, etc. ), the type and purpose of communication (poetic, official, etc. ) EX horse (neutral) steed (poetic) nag (slang) gee-gee (baby language)

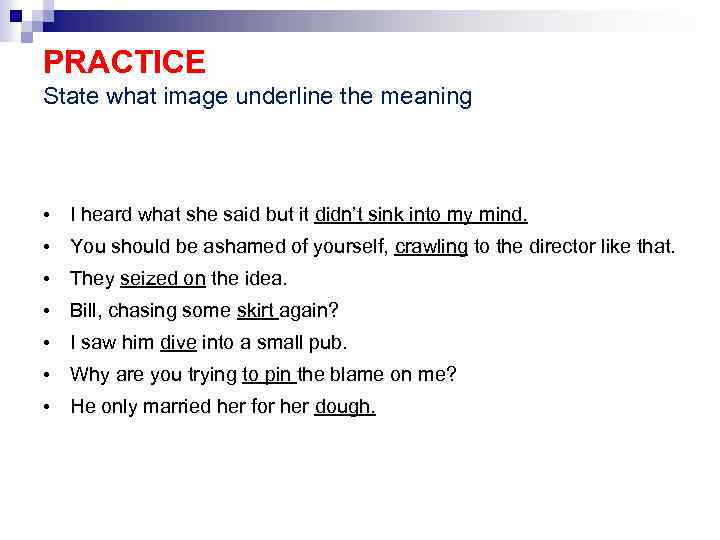

PRACTICE State what image underline the meaning • I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind. • You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that. • They seized on the idea. • Bill, chasing some skirt again? • I saw him dive into a small pub. • Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? • He only married her for her dough.

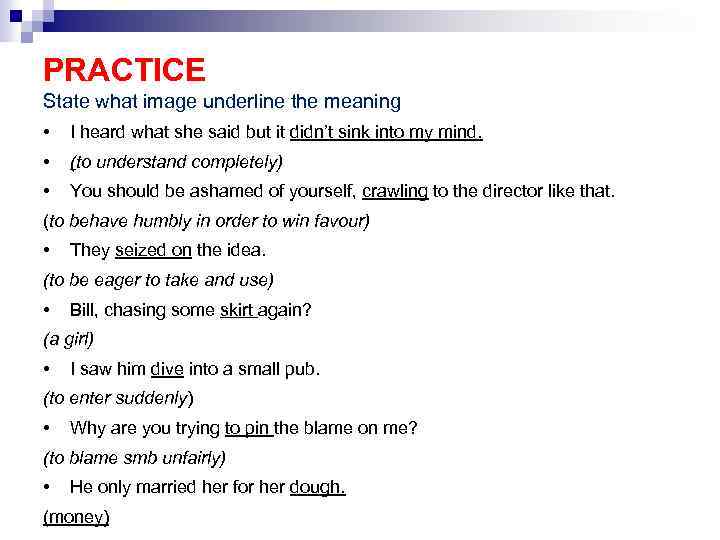

PRACTICE State what image underline the meaning • I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind. • (to understand completely) • You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that. (to behave humbly in order to win favour) • They seized on the idea. (to be eager to take and use) • Bill, chasing some skirt again? (a girl) • I saw him dive into a small pub. (to enter suddenly) • Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? (to blame smb unfairly) • He only married her for her dough. (money)

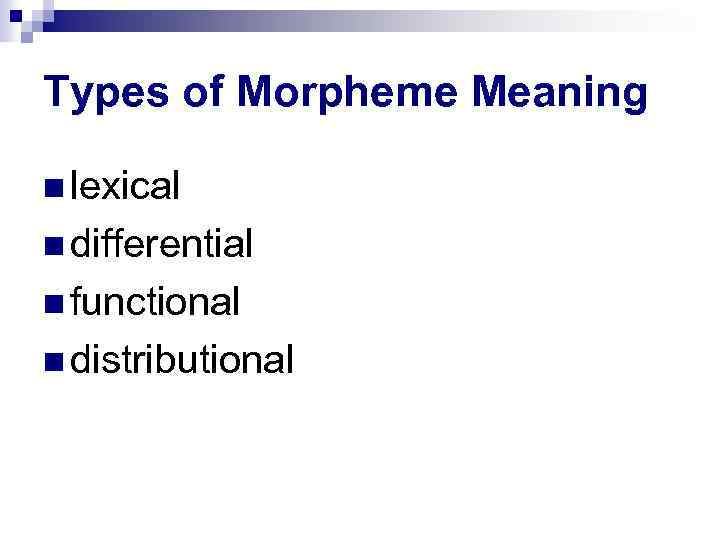

Types of Morpheme Meaning lexical differential functional distributional

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes root-morphemes that are homonymous to words possess lexical meaning EX. boy – boyhood – boyish affixes have lexical meaning of a more generalized character EX. –er “agent, doer of an action”

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes has denotational and connotational components EX. –ly, -like, -ish – denotational meaning of similiarity womanly , womanish connotational component – -ly (positive evaluation), -ish (deragotary) женственный женоподобный

Differential Meaning a semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes EX. cranberry, blackberry, gooseberry

Functional Meaning found only in derivational affixes a semantic component which serves to refer the word to the certain part of speech EX. just, adj. – justice, n.

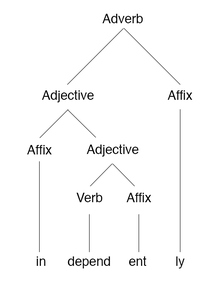

Distributional Meaning the meaning of the order and the arrangement of morphemes making up the word found in words containing more than one morpheme different arrangement of the same morphemes would make the word meaningless EX. sing- + -er =singer, -er + sing- = ?

Motivation denotes the relationship between the phonetic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on the other can be phonetical morphological semantic

Phonetical Motivation when there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word and those produced by animals, objects, etc. EX. sizzle, boom, splash, cuckoo

Morphological Motivation when there is a direct connection between the structure of a word and its meaning EX. finger-ring – ring-finger, A direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes EX think –rethink “thinking again”

Semantic Motivation based on co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word EX a watchdog – ”a dog kept for watching property” a watchdog – “a watchful human guardian” (semantic motivation)

• PRACTICE

Analyze the meaning of the words. Define the type of motivation a) morphologically motivated b) semantically motivated • Driver • Leg • Horse • Wall • Hand-made • Careless • piggish

Analyze the meaning of the words. Define the type of motivation a) morphologically motivated b) semantically motivated • Driver Someone who drives a vehicle morphologically motivated • Leg The part of a piece of furniture such as a table semantically motivated • Horse A piece of equipment shaped like a box, used in gymnastics semantically motivated

• Wall Emotions or behavior preventing people from feeling close semantically motivated • Hand-made Made by hand, not machine morphologically motivated • Careless Not taking enough care morphologically motivated • Piggish Selfish semantically motivated

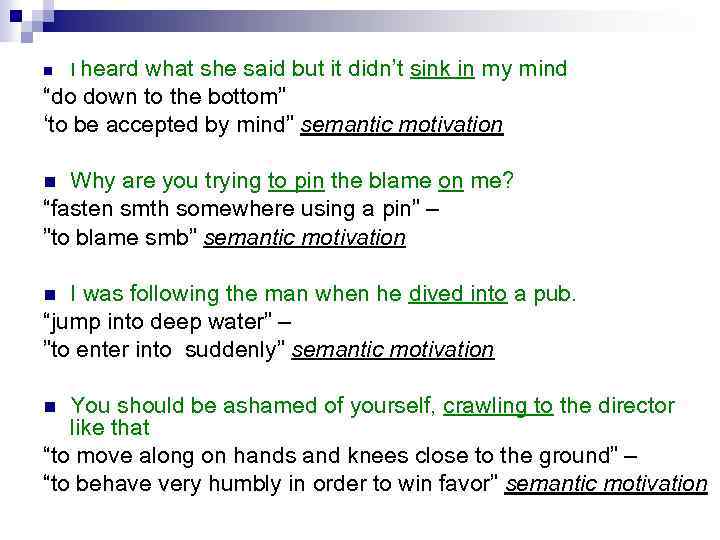

what she said but it didn’t sink in my mind “do down to the bottom” ‘to be accepted by mind” semantic motivation I heard Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? “fasten smth somewhere using a pin” – ”to blame smb” semantic motivation I was following the man when he dived into a pub. “jump into deep water” – ”to enter into suddenly” semantic motivation You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that “to move along on hands and knees close to the ground” – “to behave very humbly in order to win favor” semantic motivation

It seems easy enough to say what a word means; sun means . But

is a picture of the sun, not the real sun; we can look at

, but not at the real sun.

This is the same point made by Magritte’s picture of a pipe labelled Ceci n’est pas un pipe. A picture is not the real thing: a map is not the land it represents. When a woman told Magritte that the arm of a woman in one of his paintings was too long, he answered ‘Madam, you are mistaken; that is not a woman, it is a painting’.

Does car then mean an actual car rather than a picture of a car? If car meant a concrete individual car, each separate car in the world would have a unique name rather like the number plate V686 HJN which assigns each car a unique identity. Instead the word car means the concept of a car, i.e. cars in general. What counts is the idea of a car, relating to all cars rather than to any car in particular, so that you can see a Bugatti or a Beetle, a gleaming limousine or an old banger, and say ‘That’s a car’ if they fit your idea of carness.

The word car links something that exists in the world with a concept in our minds. There’s no way of linking the word and the world without the mind. Cars don’t usually come labelled as cars; it’s us that call them cars. The word car shows how a speaker of English organises the world – it’s not a bus and it’s not a bike — by relating a meaning inside their mind to something outside. When we say that a word refers to something – car refers to – we are taking a short cut that leaves out the mind in between.

The actual object doesn’t have to have a concrete existence. Unicorns and Martians exist only in pictures, but there are words for them and people have a good image of what unicorns look like, or indeed Martians. Words like truth, globalisation and education are abstract; at best we can give examples of true things, of globalisation or of education but we can’t point at something clearly labelled truth. The objects do not even have to pretend to exist – we can after all talk about nought or the square root of minus one, which have no existence at all. Words are clumps of information that represent our mental concept, whether relating to real things or imaginary.

Nor is the physical world cut up into separate objects, each of which has a word to label it. Instead it is parcelled up by the words of our language. Standard English has only two words for grandparents grandmother and grandfather, even if some English dialects do separate your nan from your gran and your grandpa from your granfer. Languages like Swedish have distinct words for your mother’s parents farfar and farmor, and your father’s parents morfar and mormor. Standard English finds less complex family relations than many other languages.

Since all human beings live in rather similar physical worlds, they need many words for roughly the same things. We all need words for the sun and the moon, for food and drink, for mother and son, and so on. The fact that different languages have words for the same things reflects the common ways in which human beings organise their mental worlds. But even common things can be perceived quite differently. Speakers of Hopi, an indigenous American language, don’t have a single word for ‘water’ but have different words for water in a lake kehi, and for water to drink pahe. Japanese doesn’t have a single word for rice but different words for raw rice kome, cooked rice gohan, fried rice yakimeshi and rice cooked to accompany western dishes raisu.

So there are enormous problems in translating from one language to another. You naturally expect to find a word in another language that is an exact equivalent to yours. But translating English rice into Japanese means deciding whether the rice is raw, cooked or served with western dishes. Many languages have an everyday word for ‘children of the same parent’, Geschwister in German; English only has an academic term sibling rather than an everyday word. So how do you translate Wieviel Geschwistern haben Sie? – How many X have you got? Translating it as How many siblings have you got? makes it sound like academic research rather than ordinary conversation. The only real possibility is to change it into How many brothers and sisters have you got? — the closest English can get to it by spelling out the concept in several words.

This came home to me during an experiment which involved people counting backwards aloud in various languages. Some Japanese participants asked me what seemed a curious question ‘What am I supposed to be counting?’ I was soon told that there are different number words in Japanese according to what you are counting. hitotsu ‘one’, futatsu ‘two’, mittsu ‘three’ can be used up to ten for ordinary objects such as books but cannot be used for people. Often you need to add a special counting word according to whether it is an animal, a long thin object and so on.

The nearest equivalents in English are the names for groups of things – a pride of lions, a pack of wolves, a peal of bells. Mastering counting in Japanese also means learning that the word for four shi has to be avoided as it happens to have the same pronunciation as the word for death.

So even a simple activity like counting reflects the language we speak. Our concepts and our vocabulary have a symbiotic relationship. A new idea needs a new word; the word i-pod wasn’t needed till the gadget was invented. To be more than a sequence of nonsense sounds, a new word needs a meaning; making up the word flink is useless unless I have something to use it for, some meaning to convey for which no existing word will do.

Some concepts are intrinsic to the workings of our mind. A Polish linguist who works in Australia Anna Wierzbicka has spent her life researching universals of meaning that occur in all human languages, coming up with sixty or so elements in fifteen groups. One group is I, you, someone, something, people, body; another is live, die;, another kind of, part of . These are the basic sixty ideas that all human beings share and for which they all need words.

The fact that all human beings share a particular meaning still does not explain why they need it. Why should we all want to talk about I and live? It could be our shared human situation; we all live and die so we all need to talk about the experience. Or it could be hardwired into our brains; we say kind of and part of because our brains work by dividing things up, just as deep underlying the most sophisticated computer routine is a binary sequence of ‘0’s and ‘1’s.

It is almost impossible to decide whether we can think without words. For we necessarily have to turn the thoughts into words to be able to handle them better or to talk to other people. Even if there is a stratum of the mind where concepts are separate from language, how could we tell other people about it without passing through language?

Levels of meaning Measuring meaning Cooking with words

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

- Сейчас обучается 268 человек из 64 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Word Meaning

Lecture # 6

Grigoryeva M. -

2 слайд

Word Meaning

Approaches to word meaning

Meaning and Notion (понятие)

Types of word meaning

Types of morpheme meaning

Motivation

-

3 слайд

Each word has two aspects:

the outer aspect

( its sound form)

catthe inner aspect

(its meaning)

long-legged, fury animal with sharp teeth

and claws -

4 слайд

Sound and meaning do not always constitute a constant unit even in the same language

EX a temple

a part of a human head

a large church -

5 слайд

Semantics (Semasiology)

Is a branch of lexicology which studies the

meaning of words and word equivalents -

6 слайд

Approaches to Word Meaning

The Referential (analytical) approachThe Functional (contextual) approach

Operational (information-oriented) approach

-

7 слайд

The Referential (analytical) approach

formulates the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denotedistinguishes between three components closely connected with meaning:

the sound-form of the linguistic sign,

the concept

the actual referent -

8 слайд

Basic Triangle

concept (thought, reference) – the thought of the object that singles out its essential features

referent – object denoted by the word, part of reality

sound-form (symbol, sign) – linguistic sign

concept – flowersound-form referent

[rәuz] -

9 слайд

In what way does meaning correlate with

each element of the triangle ?In what relation does meaning stand to

each of them? -

10 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

are not identical

different

EX. dove — [dΛv] English sound-forms

[golub’] Russian BUT

[taube] German

the same meaning -

11 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages

EX. [kot] Russian – a male cat

[kot] English – a small bed for a childidentical sound-forms have different meanings (‘homonyms)

EX. knight [nait]

night [nait] -

12 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

even considerable changes in sound-form do not affect the meaningEX Old English lufian [luvian] – love [l Λ v]

-

13 слайд

Meaning and Concept

concept is a category of human cognitionconcept is abstract and reflects the most common and typical features of different objects and phenomena in the world

meanings of words are different in different languages

-

14 слайд

Meaning and Concept

identical concepts may have different semantic structures in different languagesEX. concept “a building for human habitation” –

English Russian

HOUSE ДОМ+ in Russian ДОМ

“fixed residence of family or household”

In English HOME -

15 слайд

Meaning and Referent

one and the same object (referent) may be denoted by more than one word of a different meaning

cat

pussy

animal

tiger -

16 слайд

Meaning

is not identical with any of the three points of the triangle –

the sound form,

the concept

the referentBUT

is closely connected with them. -

17 слайд

Functional Approach

studies the functions of a word in speech

meaning of a word is studied through relations of it with other linguistic units

EX. to move (we move, move a chair)

movement (movement of smth, slow movement)The distriution ( the position of the word in relation to

others) of the verb to move and a noun movement is

different as they belong to different classes of words and

their meanings are different -

18 слайд

Operational approach

is centered on defining meaning through its role in

the process of communicationEX John came at 6

Beside the direct meaning the sentence may imply that:

He was late

He failed to keep his promise

He was punctual as usual

He came but he didn’t want toThe implication depends on the concrete situation

-

19 слайд

Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notion denotes the reflection in the mind of real objectsNotion is a unit of thinking

Lexical meaning is the realization of a notion by means of a definite language system

Word is a language unit -

20 слайд

Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notions are international especially with the nations of the same cultural levelMeanings are nationally limited

EX GO (E) —- ИДТИ(R)

“To move”

BUT !!!

To GO by bus (E)

ЕХАТЬ (R)EX Man -мужчина, человек

Она – хороший человек (R)

She is a good person (E) -

21 слайд

Types of Meaning

Types of meaninggrammatical

meaninglexico-grammatical

meaning

lexical meaning

denotational

connotational -

22 слайд

Grammatical Meaning

component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different wordsEX. girls, winters, toys, tables –

grammatical meaning of pluralityasked, thought, walked –

meaning of past tense -

23 слайд

Lexico-grammatical meaning

(part –of- speech meaning)

is revealed in the classification of lexical items into:

major word classes (N, V, Adj, Adv)

minor ones (artc, prep, conj)words of one lexico-grammatical class have the same paradigm

-

24 слайд

Lexical Meaning

is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributionsEX . Go – goes — went

lexical meaning – process of movement -

25 слайд

PRACTICE

Group the words into 3 column according to the grammatical, lexical or part-of –speech meaning

Boy’s, nearest, at, beautiful,

think, man, drift, wrote,

tremendous, ship’s, the most beautiful,

table, near, for, went, friend’s,

handsome, thinking, boy,

nearer, thought, boys,

lamp, go, during. -

26 слайд

Grammatical

The case of nouns: boy’s, ship’s, friend’s

The degree of comparison of adj: nearest, the most beautiful

The tense of verbs: wrote, went, thoughtLexical

Think, thinking, thought

Went, go

Boy’s, boy, boys

Nearest, near, nearer

At, for, during (“time”)

Beautiful, the most beautifulPart-of-speech

Nouns—verbs—adj—-prep -

27 слайд

Aspects of Lexical meaning

The denotational aspectThe connotational aspect

The pragmatic aspect

-

28 слайд

Denotational Meaning

“denote” – to be a sign of, stand as a symbol for”establishes the correlation between the name and the object

makes communication possibleEX booklet

“a small thin book that gives info about smth” -

29 слайд

PRACTICE

Explain denotational meaningA lion-hunter

To have a heart like a lion

To feel like a lion

To roar like a lion

To be thrown to the lions

The lion’s share

To put your head in lion’s mouth -

30 слайд

PRACTICE

A lion-hunter

A host that seeks out celebrities to impress guests

To have a heart like a lion

To have great courage

To feel like a lion

To be in the best of health

To roar like a lion

To shout very loudly

To be thrown to the lions

To be criticized strongly or treated badly

The lion’s share

Much more than one’s share

To put your head in lion’s mouth -

31 слайд

Connotational Meaning

reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about

it is optional – a word either has it or notConnotation gives additional information and includes:

The emotive charge EX Daddy (for father)

Intensity EX to adore (for to love)

Imagery EX to wade through a book

“ to walk with an effort” -

32 слайд

PRACTICE

Give possible interpretation of the sentencesShe failed to buy it and felt a strange pang.

Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking!

He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man.

The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve.

He was longing to begin to be generous.

She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles. -

33 слайд

PRACTICE

Give possible interpretation of the sentences

She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang.

(pain—dissatisfaction that makes her suffer)

Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking!

(make loud sharp sound—-the behavior that implies that the person is frightened)

He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man.

(to go at slow speed—was suffering or was ill)

The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve.

(to move smth towards oneself— to try to attract smb’s attention)

He was longing to begin to be generous.

(to start doing— hadn’t been generous before)

She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles.

(colour— a labourer involved into physical work ,constant contact with water) -

34 слайд

The pragmatic aspect of lexical meaning

the situation in which the word is uttered,

the social circumstances (formal, informal, etc.),

social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough, etc.),

the type and purpose of communication (poetic, official, etc.)EX horse (neutral)

steed (poetic)

nag (slang)

gee-gee (baby language) -

35 слайд

PRACTICE

State what image underline the meaningI heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind.

You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that.

They seized on the idea.

Bill, chasing some skirt again?

I saw him dive into a small pub.

Why are you trying to pin the blame on me?

He only married her for her dough. -

36 слайд

PRACTICE

State what image underline the meaning

I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind.

(to understand completely)

You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that.

(to behave humbly in order to win favour)

They seized on the idea.

(to be eager to take and use)

Bill, chasing some skirt again?

(a girl)

I saw him dive into a small pub.

(to enter suddenly)

Why are you trying to pin the blame on me?

(to blame smb unfairly)

He only married her for her dough.

(money) -

37 слайд

Types of Morpheme Meaning

lexical

differential

functional

distributional -

38 слайд

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

root-morphemes that are homonymous to words possess lexical meaning

EX. boy – boyhood – boyishaffixes have lexical meaning of a more generalized character

EX. –er “agent, doer of an action” -

39 слайд

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

has denotational and connotational components

EX. –ly, -like, -ish –

denotational meaning of similiarity

womanly , womanishconnotational component –

-ly (positive evaluation), -ish (deragotary) женственный — женоподобный -

40 слайд

Differential Meaning

a semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemesEX. cranberry, blackberry, gooseberry

-

41 слайд

Functional Meaning

found only in derivational affixes

a semantic component which serves to

refer the word to the certain part of speechEX. just, adj. – justice, n.

-

42 слайд

Distributional Meaning

the meaning of the order and the arrangement of morphemes making up the word

found in words containing more than one morpheme

different arrangement of the same morphemes would make the word meaningless

EX. sing- + -er =singer,

-er + sing- = ? -

43 слайд

Motivation

denotes the relationship between the phonetic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on the othercan be phonetical

morphological

semantic -

44 слайд

Phonetical Motivation

when there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word and those produced by animals, objects, etc.EX. sizzle, boom, splash, cuckoo

-

45 слайд

Morphological Motivation

when there is a direct connection between the structure of a word and its meaning

EX. finger-ring – ring-finger,A direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes

EX think –rethink “thinking again” -

46 слайд

Semantic Motivation

based on co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same wordEX a watchdog –

”a dog kept for watching property”a watchdog –

“a watchful human guardian” (semantic motivation) -

-

48 слайд

Analyze the meaning of the words.

Define the type of motivation

a) morphologically motivated

b) semantically motivatedDriver

Leg

Horse

Wall

Hand-made

Careless

piggish -

49 слайд

Analyze the meaning of the words.

Define the type of motivation

a) morphologically motivated

b) semantically motivated

Driver

Someone who drives a vehicle

morphologically motivated

Leg

The part of a piece of furniture such as a table

semantically motivated

Horse

A piece of equipment shaped like a box, used in gymnastics

semantically motivated -

50 слайд

Wall

Emotions or behavior preventing people from feeling close

semantically motivated

Hand-made

Made by hand, not machine

morphologically motivated

Careless

Not taking enough care

morphologically motivated

Piggish

Selfish

semantically motivated -

51 слайд

I heard what she said but it didn’t sink in my mind

“do down to the bottom”

‘to be accepted by mind” semantic motivationWhy are you trying to pin the blame on me?

“fasten smth somewhere using a pin” –

”to blame smb” semantic motivationI was following the man when he dived into a pub.

“jump into deep water” –

”to enter into suddenly” semantic motivationYou should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that

“to move along on hands and knees close to the ground” –

“to behave very humbly in order to win favor” semantic motivation

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 210 011 материалов в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 22.10.2020

- 141

- 0

- 21.09.2020

- 530

- 1

- 18.09.2020

- 256

- 0

- 11.09.2020

- 191

- 1

- 21.08.2020

- 197

- 0

- 18.08.2020

- 123

- 0

- 03.07.2020

- 94

- 0

- 06.06.2020

- 73

- 0

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Формирование компетенций межкультурной коммуникации в условиях реализации ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Клиническая психология: теория и методика преподавания в образовательной организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Введение в сетевые технологии»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «История и философия науки в условиях реализации ФГОС ВО»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы построения коммуникаций в организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС медицинских направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Правовое регулирование рекламной и PR-деятельности»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация маркетинга в туризме»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Источники финансов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Техническая диагностика и контроль технического состояния автотранспортных средств»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Осуществление и координация продаж»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Технический контроль и техническая подготовка сварочного процесса»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление качеством»

Globally, English is one of the most spoken and popular languages. Many English speakers believe that other cultures will understand the English words they use, without realizing that some of the words in English have different connotations or meanings in different languages. Many of these English words are the same in spelling, for example in German, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Sweden and many other languages, but they have different meanings.

Other words sound like English words with a slight difference in pronunciation, such as taxi, which in Korean is taek-si (pronounced taek-shi).

False friends

The words may be similar due to them coming from the same language family or due to loan words. In some cases they are ”false friends” meaning the words stand for something else from what you know.

- In English “to use the voice,” means to say something “aloud.” In Dutch, aloud means “ancient”

- The English word “angel” means a supernatural being often represented with wings. Angel in German translates to ”fishing rod” and ”sting” in Dutch.

- You mean something not specific or whatever when you say “any.” But in Catalan, it is equivalent to “year” although others use the word “curs.”

- The arm is an upper body extremity but for the Dutch it is the term used when they mean “bad.” But the English term ”bad” is equivalent to ”bath” in Dutch.

- Bank could be an institution where people deposit their money, something or someone you trust or the sloping land close to a body of water. For the Dutch, ”bank” means cough.

- An outlying building in a farm is called ”barn,” which is the term for ”children” in Dutch. On the other hand the English word ”bat” refers to a flying mammal or a club used to hit a ball. In Polish, the word means, ”whip.”

- Beer in English means a ”bear” in Dutch, while they use the term ”big” to refer to a ”baby pig.”

- “Car in a motorized vehicle, but for the French, it means ”because.” A chariot for the English speakers is a horse-drawn vehicle or a carriage, but the French use this term to mean something smaller, like a ”trolley.”

- You use the term ”chips” when you mean ”French fries” while the French use ”Crisps” when they say chips.

- Donkey in Spanish is ”burro” whereas for the Italian, it means ”butter.”

- The English word ”gift” means ”poison” in German and Norwegian and ”married” in Swedish.

- “Home” is where you live, but it means ”mold” in Finnish and ”man” in Catalan.

- “Panna” is cream in English and in Italian, but means ”put” in Finnish. In Polish, they use the term it indicate “a single woman.”

- The Spanish term for frog is “rana,” but rana means, ”wound” in Romanian and Bulgarian.

- “Sugar” is something sweet and it’s a sweet term used by Romanians for a baby aged 0-12 months. But the speakers of Basque use the term to mean ”flame.”

- Tuna is a large fish that is a Japanese favorite when making sashimi. The term means ”cactus” in Spanish or a ”ton” in Czech.

- “Fart” is a vulgar English word that means expelling intestinal gas. But it means ”good luck” in Polish and ”speed” in Swedish. In French, though, ”pet” is the translation of ”fart” (yes, the foul-smelling variety).

- Cake in Icelandic is ”kaka” but it is an ”older sister” in Bulgarian. “Kind” means ”child” in German but ”sheep” in Icelandic.

- You’re likely to say ”prego” when you’re in Italy instead of the usual ”thank you” but it means something very mundane in Portuguese. In Portugal, it is the term they use for ”nail.”

- ”Privet” is a type of evergreen shrub or small tree that you can use as a border wall. But in Russian, privet, which means ”greetings,” is informally used to say ”hello.”

- Watercress is a salad green that is called ”berros” in Spanish. The Portuguese however has a very different meaning to berros. To them, it means scream.

- When you hear the Swedes say ”bra,” they mean ”good,” instead of a type of women’s underwear.

- “But” is a conjunction in English, whereas the Polish use the term to indicate ”shoe.”

- This one is a bit similar. The term ”cap” is the Romanian word for ”head.” We say ”door” when we mean the opening to gain access into a room or the panel that opens and closes an entrance. Door in Dutch is almost similar, as it means ”through.”

- ”Fast” in German means almost, while ”elf” means the number eleven. ”Grad” is the German term for ”degree” but means a ”city” in Bosnian.

- Make sure you remember this. When is Spain, “largo” means ”long” but it means ”wide” in Portuguese.

- The meaning of ”pasta” is very different in Polish and Italian. In Italian it is the term for ”noodles,” while in Polish, it means ”toothpaste.” When you’re in Norway, “sau” means sheep while in Germany, it means sow (female pig). “Pig” is ”gris” in Swedish while in Spanish, gris means ”gray.”

- “Glass” is something shiny, hard and brittle in English, but it turns to soft, cold, sweet and gooey ”ice cream” when you’re in Sweden.

- The Italians use the word ”vela” when they mean, ”sail.” In Spain though it means ”candle.”

- The number six in Spanish is ”seis” and for the Finnish, they say this when they mean, ”stop!”

- The big, blue ”sky” means ”gravy” in Swedish, while ”roof” means ”robbery” in Dutch.

- When a Swedish says, ”kiss,” it means ”pee” instead of caressing with the lips.

- “Carp” is a fish beloved in Japan and it is a type of freshwater fish found in Asia and Europe. But in Romanian, the carp is called ”crap.” Hmm…

- Trombone is a musical instrument. It is the instrument of choice for some of the famous artists such as Joseph Alessi, J.J. Johnson, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey and Frank Rosolino. But in French, it is something very ordinary – a paper clip.

- “Awesome” in German is “hammer.”

- “Barf” means ”snow” in Urdu, Hindi and Farsi.

Be careful with your words

Words can hurt other people if you are not careful. English speakers who love to travel should take time to learn the culture and read about the quirks and characteristics of the main language spoken in their destination. They should know that some words in a foreign language might sound like English but stand for something different in another language.

If you are in Wales, do not feel slighted when you hear a Welsh-speaking native say ”moron” while you’re in the market. The person might be trying to sell you some ”carrots.”

In English, you can say you ”won” something and feel proud or happy. In South Korea, it is their national currency. When a house is said to be ”won” in Polish, it means that it is ”nice smelling.” Russia has a different interpretation, however. In Russian, using the word ”won” means describing something that ”stinks.”

The Spanish term ”oficina” translates into ”office” in English. But for the Portuguese, an ”oficina” is only a ”workshop,” such as a mechanic’s shop.

The term ”schlimm” sounds like ”slim” in English. In the Netherlands, this stands for being smart or successful. But in Germany, which is 467.3 kilometers away from the Netherlands by car via A44, (roughly a five-hour drive), schlimm means ”unsuccessful and dim-witted!

English speakers understand that ”slut” is a derogatory word. But for the Swedish, this means ”finished” or the ”end,” something that you’d say when you want your relationship with your Swedish boyfriend or girlfriend is over. So when you’re in Sweden, you’ll see signs such as ”slutspurt” that means a final sale or ”slutstation” when you’ve reached a train line’s end.

If you’re an urbanite, it is difficult to enjoy fresh air unless you go to the countryside. “Air” in Malay (sounds like a-yah), which is an official language in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei, it means ”water.” When you mean the ”air” you breathe, you use the word ”udara.”

In English and in German, the word ”dick” is derogatory. It means ”fat” or ”thick” in German.

You might think that the Spanish appetizer ”tapas” is universally understood when you’re in South America because you are so used to seeing tapas bars in the U.S., UK, Canada, Mexico and Ireland (or their own version of it). However, in Brazil, where Portuguese is an official language, ”tapas” means ”slap” rather than a delicious snack. If you want to have tapas-like snacks to go with your beer, the right term to use is ”petiscos” or ”tira-gostos.” Now you know the right term to use when you’re in Brazil. If you go to Mexico, you can order ”botanas” and ask for some ”picada” in Argentina or ”cicchetti” if you happen to be in Venice. In South Korea, tapas-like appetizers are called ”anju.”

Sounds like…

In Portuguese, the word ”peidei” that sounds like ”payday” means, ”I farted.”

Salsa is a wonderful, graceful and thrilling dance style, but in South Korea, when you hear the word ”seolsa,” which sounds like ”salsa” it refers to ”diarrhea.”

Speaking of diarrhea, in Japanese, the term they use is ”geri,” which sounds like the name ”Gary.”

”Dai,” an Italian word, is pronounced like the English word ”die.” The literal translation of this is ”from” but it is colloquially used by the Italians to mean, ”Come on!”

The English term ”retard” could either mean delay or move slowly. It could also mean moron or imbecile. In French, ”retardé” translates to delay as well.

There is an English term called a ”smoking jacket” which is a mid-length jacket for men that is often made of quilted satin or velvet. The French however call a ”tuxedo,” which is a semi-formal evening suit, ”smoking.”

“Horny” is an English term that is mostly associated to feelings of being aroused or turned on. Literally, it means something with horn-like projections, many horns or made of horns, such as ”horny coral” or ”horny toad.” But ”horní” in Czech simply means ”upper.”

In Spanish, ”gato” means ”cat” but ”gateux” is ”cake” in French.

Eagle is a soaring bird. In Germany, the word ”igel” that has a similar pronunciation to ”eagle” actually means ”hedgehog.”

Something else

The term ”thongs” is usually associated with sexy swimwear or underwear. When you’re in Australia though, thongs refer to rubber flip-flops.

In Polish, the month of April is ”Kwiecień” while in Czech, the similarly sounding term, ”Květen” is for the month of May.

For English speakers a ”preservative” is a chemical compound that prevents decomposition of something. But be careful when you say the word while in France, as this means ”condom” for the French. It means the same thing in many different languages in Europe as well, such as:

- Prezervativ (Albanian)

- Preservative (Italian)

- Prezervatīvs (Latvian)

- Prezervatyvas (Lithuanian)

- Prezerwatywa (Polish)

- Preservative (Portuguese)

- Prezervativ (Romanian)

- Prezervativ (Russian)

- Prezervatyv (Ukranian)

‘In Spanish, ”si” means yes, but ”no” in Swahili. “No” is ”yes” in Czech (a shortened version of “ano.” “La” is ”no” in Arabic.

”Entrée” is a French term that translates to ”appetizer.” In American English though, term is used to indicate the ”main course.”

“Mama” in Russian and in several other different languages means ”mother.” However, in Georgian, ”mama” is the term for ”father.”

Languages are definitely fascinating and interesting, but there is enough reason to learn a few things about it to avoid a faux pas when you are in another country, because English words could mean differently. Ensure that your English documents are translated accurately in different languages by getting in touch with a translator from Day Translations, Inc. Our translators are not only native speakers; they are also subject matter experts. Give us a call at 1-800-969-6853 or send us an email at contact@daytranslations.com for a quick quote. Our translators are located world-wide and we are open every single day of the year. We can serve you any time, wherever you are located.

Image Copyright: almoond / 123RF Stock Photo

This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

![Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove - [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove - [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian](https://present5.com/presentation/54919015_285694613/image-10.jpg)

![Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot] Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot]](https://present5.com/presentation/54919015_285694613/image-11.jpg)

![Meaning and Sound-formare not identical

different

EX. dove - [dΛv]... Meaning and Sound-formare not identical

different

EX. dove - [dΛv]...](https://documents.infourok.ru/2d0c9b9d-1c12-4da2-8c1e-80496902c301/slide_10.jpg)