When

ether we mention it, we mean phonetic and historic length. There are

historically long and historically short vowels, and also

phonetically short and long.

Phonetically long differ in various positions.

There are many attempts to give a phonological interpretation of the

conception of quantity with respect to the English vocalic system.

The

primary purpose of any kind of a phonological analysis is to propose

clear-cut functional boundaries between relevant and irrelevant

features. Relevant in the meaning of distinctive or differential

features and irrelevant in the meaning of

_______________________________.

Relevant

features are important for a language functioning in the society. But

it is not enough to know only relevant features when it comes to

teaching the language. For practical purposes we have to know

irrelevant features as well.

Is

vowel length relevant in present day English?

Many people say a definite “no”, it is not

relevant. It has not been relevant for 4 hundred years. Diachronic

study the lines

testifies (свидетельствовать)

to the fact. The scholars of the last century took it for granted

that vowel length in English is relevant. And no one ever attempted

to question it. They acknowledged 3 degrees of vowel length or 3

types of vowels with respect to their length:

-

long [sɔ:,pɔ:,ka:,ba:]

-

half-long [pi:k,pa:t]

-

short [pın,pɒt]

later

on 4 degrees wore introduced because i: in [di:d] is much longer than

in [di:p]

by the degrees of length, not the historical, but

rather the position of a vowel in a word was taken into account. Thus

vowels were grouped into the following patterns

-

an open syllable – the longest vowel [pɔ:]

-

before sonorant – shorter but long enough

[si:n, di:n, ri:l, ɔ:l] -

before voiced consonants [di:d, si:d]

-

before voiceless consonants [si:t], [sit] no

matter historically shorter or long

there

were many attempts to measure vowel length acoustically

(instrumentally)

the

first meaningful attempt was made by a German linguist Meyer in 1903.

he came to the following conclusion: there are as many degrees of

vowel length as there are positions which a vowel occurs in a word.

They are innumerable but not formed. T was a far

reaching conclusion because it was the 1st

meaningful experimental substantiated conclusion. It was an attempt

to consider the vowel length as a disputable question and not to take

it for granted. But no matter how accurate these attempts are. It

doesn’t follow that vowel length is redundant (чрезмерный)

characteristic feature. There is not yet enough prove because this

difference in vowel length may be explicable in terms of allophonic

variations. Another justification for the statement that vowel length

is not relevant must be found.

In teaching phonetics we know from the experience

that vowels differ not only in length. That is quantity, it is also

the quality that makes them different. For example, traditional pair

of short and long counterparts: i: I,

ɔ:ɒ, ɑ:ʌ, u:ʊ, ɜ:ǝ

if

we think that the difference is in length, it is wrong. They are

different in the matter of quality. I: is a diphthong not a

monophthong . it is more accurate to make is “ij”

so

they are qualitatively different vowels.

Another pair is u: ʊ.

There is no opposition as they belong to different groups.

ɜ: ǝ

(шуа

occurs only and exclusively in

unstressed positions, другой almost

never loses much of its quality)

they never occur in the same position. Thus this

opposition doesn’t work either. They are sounds of different

planes.

ɑ:ʌ

it is very arbitrary

(случайно)

kind of opposition. It is more relevant hidtorically and

phonologically to appose ɑ:

to æ. More over [ʌ]

and more over occurs as [шуа]

ɔ:ɒ

it is the only pair that may seem to be right. But it does not work

either because perceptual phonetic findings show that if we reduce

the degree of length in ɔ:

it will be perceived by the natives

of the English as ʊ.

Consequently this opposition with the reference to

the length does npt worl. They are different because their quality is

different.

About 40 years ago Vassiliev with the approval of

the international phonetic associations proposed to change some of

the symbols to show that the vowels are different not only in the

length but also in quality. His symbols u на

ʊ,

ɔ на

ɒ, ǝ: на

ɜ:

Some people used to say that the difference in

length is nothing else but the manifestation of differences in the

degree of tenseness. Long vowels are tense and short vowels are lax.

And the main feature for length difference is the difference in the

degree of tenseness.

In fact this hardly the case in English. British

phoneticians supply examples to prove that English vowels are very

flexible in the matter of prolongation (продолжение).

And it was a wrong idea that tenseness brings length

_______________________vice versa.

A more sound approached to the problem is to

regard it into the context of syllable structure. If the vowel is

regarded as a constituent (компонент)

of a syllable it depends on a kind of a contiguity (близость,

примыкание) of a consonant which

adjoins it.

According to the theory vowels can be checked and

unchecked. In the course of its historical development vowel

quantitative correlation changed into the so-called checked-unchecked

syllabic correlation. Thus from this stand point that vowel length is

a redundant (чрезмерный)

characteristic, it is not relevant.

But

we must not assume that this is the end point in the development of

the English vocalic system.

We know that the pronunciation of a language is

subject to a constant change. It is less stable than grammar and the

vocabulary. Thus since quantity of a vowel is not relevant, it is

preferable to avoid using the terms long short length. It is better

to speak about duration, because it implies the idea of oppositional

length.

Thus the 2 main constituencies of English vowels

are vowel quality and vowel quantity. Among them only vowel quality

is relevant. Prove it: pıt

— pi:t ʃıp — ʃi:p.

It is vowel quality which differentiates the

meaning. In the position before voiceless consonants historical long

and short vowels are of equal length. [bi:d-bıd,sıd-si:d]

Here the vowels are before voiced consonants.

Before voiceless consonants historically long vowels become shorter.

But the quality is stable.

Vowel

quality and vowel length differentiate the meaning.

Vowel

length is affected by the position of the vowel in a word or a

sentence. The vowel is longest in the final position. It is short

before the voiceless consonants. It is longer in a nucleolus

syllable.

In teaching it is necessary to provide exercises

to train because there is a connection between the vowel length and

the type of the syllable. That is why it is important to teach

syllabication.

In modern English there is a new tendency to which

vowel length become relevant again someday [lætǝ

— lædǝ] latter-ladder

The problem is connected with the pronunciation of

consonants in their vocalic positions. There is a tendency to make

the consonants voiced, that is why these consonants seemed to become

homonyms: [æ]

in latter remains short [æ]

in ladder is long. It may cause relevance of vowel length in future.

Moot points in the system of English phonemes

-

consonants

-

[w]

– [ʍ]

wh

Some

linguists say that there are 2 consonant phonemes in English when we

have “wh” in spelling. If we oppose them, we can see that this

opposition differentiates the meaning. Our linguists consider them to

be one and the same phoneme.

[ʍ]

it is mainly used in literary style. Most English speakers pronounce

only [ʍ]

According to Jones’ dictionary [ʍ]

is used in all variants

-

[ʧ-ʤ]

According to our textbooks there are 2 affricates

in English. Affricate is a phoneme consisting of 2 consonant

elements. According to British linguists there are 6 affricates

[ʧ,ʤ,ʦ,ʣ,tr,dr]

When

must sound combination be treated as uniphonemic?

-

they must stand a whole in a phoneme opposition

-

belong to the same morpheme and syllable

-

the articulation must be shifting

[ʧ,ʤ]

[ʦein-mein-sein]

— ʧ

stands as a whole and belongs to the same syllable.

There are cases when similar combinations consist

of 2 phonemes [kɔ:t

ʃɪp] – different syllables,

articulation is not shifting.

[ʦ-ʣ]

not quite clear

[kæʦ-beʣ]

– may be either the plural form. Belong to different morphemes (s,z

— endings), but the syllable is the same.

There

are no affricates like them in English

There is no [y] in Russian, the Greek word [zɑ:].

If there were such an affricate, it would be pronounced as [ʦɑ:]

[tr,

dr] can easily fall apart in the phonological opposition. The

opposition is [krai-trai-drai]

Here

it belongs to the same syllable, but the articulation is not

shifting. Thus it is difficult to decide if these are the combination

of the phoneme or they are separate phonemes.

Vowels

-

some linguists say that there are no diphthongs, they are

combinations of 2 sounds

[bei-bai-bi:-bɔ:]

The

combination stands as a whole in this opposition, they belong to the

same syllable and morpheme

[`pʊəlrə]

– the sound combination [ʊə]

belongs to 1 syllable and morpheme even when add an extra morpheme

[rə],

[ʊə]

doesn’t fall apart, the articulation is shifting. There are similar

combinations when these vowels fall apart and belong to different

syllables and morphemes

[fju:

— fju:] [influənts

— influənt∫l]

there are 2 morphemes and two different syllables

-

a neutral vowel

is a neutral sound a phoneme or is it an

unstressed allophone of some other phoneme?

If

we approach from the point of view of the phonological Moscow school,

there are two cases:

-

when the neutral vowel can be opposed to some other morpheme

[`ɑ:mi-`ɑ:mə]

(armour)

the morphemes are different, the meaning is different, that is why

the neutral vowel is the separate phoneme

-

[`ɒbʤɪkt

— əb`ʤekt] the morpheme is the

same, here [ə]

– is an unstressed allophone of [ɒ]

According to the Leningrad school, [ə]

is always an independent phoneme, because it sounds different

New tendencies of pronunciation

5

groups of changes in present day English:

-

a change may consist simply in the replacement of

one phoneme by another. In Northern English they pronounce [mʌndeɪ]

according to the British norm they used to

pronounce [mʌndɪ],

in dictionary [mʌndeɪ]

is the first variant

-

a phoneme may disappear from a word completely, or it may disappear

regularly from certain position: knight, knee -

a phoneme or the member of the phoneme can change in quality

ME i: > NE ai life

ME u > NE ʌ dull

-

there may be changes in the whole phonemic structure. New phonemes

may appear, other may disappear

OE [θ,ð]

one allophones of the phoneme

ME they are separate: thing – thy

-

prosodic changes (in stress and intonation). In

present century a number of two-syllabic words have had the stress

moved from the second syllable to the first: adult, ally (друг,

союзник)

vowel

changes

-

isolated changes

they take place in respective (соответствующий)

of the phoneme position, occupied by the phoneme. The quality of some

sounds changes:

[ʌ]

In 1932 Jones characterized the sound as half-open

rather retracting (продвинутый

назад). In 1964 Charles Barbar

considered this phoneme to be more retracted, opened, central,

forward, lower

kʌp — bʌtə

[ɔ:]

[lɔ:t

— ʃɔ:t]

used

to be retracted and rather opened, it became less open, and the

tongue is much higher

[ai]

For

Jones it was a frank diphthong. Barbar considers the phoneme more

retracted, where the element [a] is a back element

The centripetal tendency

[e] develops towards the position of [ə]

[ʊ]

loses lip rounding and moves to [ə],

as [ʌ]

[bout] – [bəʊt]

-

combinative changes

take

place in certain phonetic contexts

[ə:] >

[ɒ]

before voiceless [t, s. θ]

– soft, often, cloth

In early ME these words had a short [ɒ].

In the 17th

century it became lengthened before [t, s. θ],

the long forms were fashionable in the 18 century. Now the original

form is becoming predominant

[ju:] > [u:] preceded by [ʧ,ʤ,r,l]

This change has been going on since the 17th

century. There is an intermediate group though both forms are heard.

After

[s] [su:t – sju:t]

[ə`sju:m

– su:m]

[kən`sju:m

– su:m]

After [θ]

[in`θju:ziæzm

— `θu:]

After

[z] [ri`zju:m – `zu:m]

Initial [l] [,lu:k`wɔ:m]

[`lu:nətik

– `lju:]

Medial [l] [,æbsə`lu:t

– `lju:t]

This

process is more advanced in American English

Dubious — сомнительный

AE [`du:biəs

– `dju:]

BE [dju:biəs]

-

Diphthongization [i:], [u:]

Jones thought them to be pure vowels (organs not

more). As a pure vowel [u:] has a closer lip-rounding and a narrower

jaw-opening. Barbar says that this sound is diphthongized, speech

organs change their position:

[u+u] > [ʊ+u] > [ə+u]

– a substandard variant

In the course of diphthongization the lip-rounding

is tightened , jaw-opening is narrowed.

In

the pronouncing of the sound [i:] the organs of speech move from:

[i+i] > [i+j] > [ə+j]

– a substandard variant

-

monophthongization – the process of smoothing of diphthong. They

become more like pure vowel, the glide is slight

[ei] – say, play [e.i+i]

[ai, aʊ]

– tend to be smoothed when followed by [ə]

the central element is lost:

[taʊə

— taə — ta:]

[faiə

— faə — fa:]

5. fial [i] > [i:], [ə]

– pronounced closer and longer

[`priti

– `priti:, `pritə]

RP speaker tend to make final [i] into an open

sound. Occasionally [i] is replaced in other positions

[bi`twi:n

– bi:`twi:n] [i`levn – i:`levn]

substandard [əi]

-

[iə] > [i+ə]

[ʊə] > [ʊ+ə]

Nausea [`nɔ:siə] [`nɔ:si+ə]

– spelling pronunciation

-

the influence of dark [l] in [ɒlt,ɒlv,ɔ:lt]

[ɒ],

[ɔ:] > [əʊ]

Salt [sɔ:lt,

sɒlt]

-

the spread of [ə]

in unstressed syllables. Alternative forms of vowels in unstressed

syllables:

system [`sistəm

— tim]

corridor [`kɒridɔ:]

[`kɒrədə]

boxes BE [`bɒksiz]

– AE [`bɒksəz]

ended BE[`endid]

— AE

[`endəd]

-

In vowel length

[i] – big, his

[ʊ]

– good

[ʌ]

– come lengthening

[e]

– bed

[æ]

– man

Length is frequent in monosyllabic words which a voiced consonant.

Jones: all adjectives ending in “ad” are long.

He suggests that this is the first stage of a large scale change in

the language. The present difference between vowel quality and length

give a way to a difference based on quality only as the language is a

system of interrelated parts there must be a certain pattern in all

these various vowel changes. There are 2 consistent trends:

-

the short vowels all seem to be becoming more central and lengthened

-

2 front close vowels [i:] [u] are both being

diphthong. It is paralleled to what happened in the great vowel

shift when [i] and [ʊ]

became diphthongs [ai] [aʊ]

Consonants changes

-

Assimilation – a process by which a sound is

altered through the influence of a neighboring sound. The sound

which is influenced becomes phonetically more like the sound

exerting the influence. There are various miscellaneous (смешанный)

sources of _____________________ changes.

-

historical assimilation

took place earlier, [æ]

changed under the influence of [w]

-

devoicing

[z] – [s] news – newspaper

[d] – [t] amidst [ə`midst

— `midst]

-

in compound words

tenpence [`tenpənts

— `tempənts]

football — not registered

-

in rapid familiar speech

give me [`gimmi]

-

coalescing _____

[dj

— ʤ] due

[tj —

ʧ] Tuesday, tube

[sj —

ʃ] issue [i

ʃu: — isju:]

-

new weak forms

many English words have forms which occur in

unstressed position, rapid speech

that’s

right [srait]

that’s funny [s`fʌni]

what does he want [`wɒts

hi ,wɒnt]

-

weakening and loss of consonants

-

final alveolar (t,d,n)

fourtee(n) men – articulated weakly or disappear

ol(d) man

half pas(t) five

-

loss of plosives [p,b,k,g]

-

a closer is formed

-

the closer is ______ while pressure is built behind it

-

the stop is realized by the __________

the

final phrase is omitted

knocked,

bed-time

the stop is not realized, sometimes the 1st

plosive disappears: castle

-

simplification (упрощение)

of double consonants: a good deal

Upside down

Lamp past

-

initial combinations: psychic [saikik]

where [hwere]

-

loss of [h] in the beginning: he gave him his breakfast

-

devoicing the consonants [b, d, g] feed [fi:d],

rogue [rəʊɡ]

-

voicing of consonants (intervocalic

position) letter AE, vulgar RE [ledə],

British [bridiʃ]

-

intrusive (навязчивые)

consonants – inserted into the words where they does not exist

-

[ns] > [nts]

Once [wʌnts],

fancy [fæntsi]

-

[p], [k]

Warmth [wɔ:mpθ],

length [lenkθ]

-

intrusive [r] – affect of analogy

here and there [hiər

ən ðƐə]

idea(r)and

reality

Dialect Mixing

The group of popular pronunciation. It involves the substitution of a

long vowel of a diphthong by a short vowel.

Stabilized [`steibilaizd] – [`stæ…]

Reproduce [ri:prə`dju:s]

– [`re]

South – Easter dialect

Monday, necklace [`mʌndi],[`neklis]

Changes of Stress

In words of more than 2 syllables the popular

forms are the forms with the main stress on the second syllable:

communal [`ju:], hospitable [`i:]

In 2 syllabic words the tendency goes the other

way, the stress is moved to the 1st:

`garage, adult [`ædʌlt][ǝ`dʌlt]

Spelling Pronunciation

Forehead [`fɔ:hed-`fɒrid]

Often [ɒfn-

ɒftn]

Toward [tǝwɔ:d,

twɔ:d, tɔ:d] especially common for

newly invented words

Continental Pronunciation

Tendency

for foreign-looking words

Gala [geil-

gɑ:lǝ]

Faustus [`fɔ:stǝs

— `faʊ-]

The word which has undergone normal historical

processes of English sound-change is made to confirm more closely to

the real or imagined pronunciation, its foreign origin. Latin words

received new pronunciation. Latin plural endings which are normally

anglicized and now relatinized: nuclei [nju:klii:] – [nju:kliei]

Lecture № 4

Classification of sounds

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

| Long | |

|---|---|

| ◌ː | |

| IPA Number | 503 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ː |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02D0 |

| Half-long | |

|---|---|

| ◌ˑ | |

| IPA Number | 504 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˑ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02D1 |

| Extra-short | |

|---|---|

| ◌̆ | |

| IPA Number | 50 5 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ̆ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+0306 |

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived length of a vowel sound: the corresponding physical measurement is duration. In some languages vowel length is an important phonemic factor, meaning vowel length can change the meaning of the word, for example in Arabic, Estonian, Finnish, Fijian, Japanese, Kannada, Kyrgyz, Latin, Malayalam, Old English, Scottish Gaelic, and Vietnamese. While vowel length alone does not change word meaning in most dialects of English, it is said to do so in a few dialects, such as Australian English, Lunenburg English, New Zealand English, and South African English. It also plays a lesser phonetic role in Cantonese, unlike in other varieties of Chinese.

Many languages do not distinguish vowel length phonemically, meaning that vowel length does not change meaning, and the length of a vowel is conditioned by other factors such as the phonetic characteristics of the sounds around it, for instance whether the vowel is followed by a voiced or a voiceless consonant. Languages that do distinguish vowel length phonemically usually only distinguish between short vowels and long vowels. Very few languages distinguish three phonemic vowel lengths, such as Estonian, Luiseño, and Mixe. However, some languages with two vowel lengths also have words in which long vowels appear adjacent to other short or long vowels of the same type: Japanese hōō, «phoenix», or Ancient Greek ἀάατος [a.áː.a.tos],[1] «inviolable». Some languages that do not ordinarily have phonemic vowel length but permit vowel hiatus may similarly exhibit sequences of identical vowel phonemes that yield phonetically long vowels, such as Georgian გააადვილებ [ɡa.a.ad.vil.eb], «you will facilitate it».

[edit]

Stress is often reinforced by allophonic vowel length, especially when it is lexical. For example, French long vowels are always in stressed syllables. Finnish, a language with two phonemic lengths (i.e. vowel length changes meaning), indicates the stress by adding allophonic length, which gives four distinctive lengths and five physical lengths: short and long stressed vowels, short and long unstressed vowels, and a half-long vowel, which is a short vowel found in a syllable immediately preceded by a stressed short vowel: i-so.

Among the languages with distinctive vowel length, there are some in which it may occur only in stressed syllables, such as in Alemannic German, Scottish Gaelic and Egyptian Arabic. In languages such as Czech, Finnish, some Irish dialects and Classical Latin, vowel length is distinctive also in unstressed syllables.

In some languages, vowel length is sometimes better analyzed as a sequence of two identical vowels. In Finnic languages, such as Finnish, the simplest example follows from consonant gradation: haka → haan. In some cases, it is caused by a following chroneme, which is etymologically a consonant: jää «ice» ← Proto-Uralic *jäŋe. In non-initial syllables, it is ambiguous if long vowels are vowel clusters; poems written in the Kalevala meter often syllabicate between the vowels, and an (etymologically original) intervocalic -h- is seen in that and some modern dialects (taivaan vs. taivahan «of the sky»). Morphological treatment of diphthongs is essentially similar to long vowels. Some old Finnish long vowels have developed into diphthongs, but successive layers of borrowing have introduced the same long vowels again so the diphthong and the long vowel now again contrast (nuotti «musical note» vs. nootti «diplomatic note»).

In Japanese, most long vowels are the results of the phonetic change of diphthongs; au and ou became ō, iu became yū, eu became yō, and now ei is becoming ē. The change also occurred after the loss of intervocalic phoneme /h/. For example, modern Kyōto (Kyoto) has undergone a shift: /kjauto/ → /kjoːto/. Another example is shōnen (boy): /seuneɴ/ → /sjoːneɴ/ [ɕoːneɴ].

Phonemic vowel length[edit]

As noted above, only a relatively few of the world’s languages make a phonemic distinction between long and short vowels; that is, saying the word with a long vowel changes the meaning over saying the same word with a short vowel. Examples of such languages include Arabic, Sanskrit, Japanese, Biblical Hebrew, Scottish Gaelic, Finnish, Hungarian, etc.

In Latin and Hungarian, some long vowels are analyzed as separate phonemes from short vowels:

Latin vowels

|

Hungarian vowels

|

Vowel length contrasts with more than two phonemic levels are rare, and several hypothesized cases of three-level vowel length can be analysed without postulating this typologically unusual configuration.[2] Estonian has three distinctive lengths, but the third is suprasegmental, as it has developed from the allophonic variation caused by now-deleted grammatical markers. For example, half-long ‘aa’ in saada comes from the agglutination *saata+ka «send+(imperative)», and the overlong ‘aa’ in saada comes from *saa+ta «get+(infinitive)». As for languages that have three lengths, independent of vowel quality or syllable structure, these include Dinka, Mixe, Yavapai and Wichita. An example from Mixe is [poʃ] «guava», [poˑʃ] «spider», [poːʃ] «knot». In Dinka the longest vowels are three moras long, and so are best analyzed as overlong /oːː/ etc.

Four-way distinctions have been claimed, but these are actually long-short distinctions on adjacent syllables.[citation needed] For example, in Kikamba, there is [ko.ko.na], [kóó.ma̋], [ko.óma̋], [nétónubáné.éetɛ̂] «hit», «dry», «bite», «we have chosen for everyone and are still choosing».

By language[edit]

In English[edit]

Contrastive vowel length[edit]

In many varieties of English, vowels contrast with each other both in length and in quality, and descriptions differ in the relative importance given to these two features. Some descriptions of Received Pronunciation and more widely some descriptions of English phonology group all non-diphthongal vowels into the categories «long» and «short,» convenient terms for grouping the many vowels of English.[3][4][5] Daniel Jones proposed that phonetically similar pairs of long and short vowels could be grouped into single phonemes, distinguished by the presence or absence of phonological length (Chroneme).[6] The usual long-short pairings for RP are /iː + ɪ/, /ɑː + æ/, /ɜ: + ə/, /ɔː + ɒ/, /u + ʊ/, but Jones omits /ɑː + æ/. This approach is not found in present-day descriptions of English. Vowels show allophonic variation in length and also in other features according to the context in which they occur. The terms tense (corresponding to long) and lax (corresponding to short) are alternative terms that do not directly refer to length.[7]

In Australian English, there is contrastive vowel length in closed syllables between long and short /e/ and /ɐ/. The following are minimal pairs of length:

| /ˈfeɹiː/ ferry | /ˈfeːɹiː/ fairy | |

| /ˈkɐt/ cut | /ˈkɐːt/ cart |

Allophonic vowel length[edit]

In most varieties of English, for instance Received Pronunciation and General American, there is allophonic variation in vowel length depending on the value of the consonant that follows it: vowels are shorter before voiceless consonants and are longer when they come before voiced consonants.[8] Thus, the vowel in bad /bæd/ is longer than the vowel in bat /bæt/. Also compare neat with need . The vowel sound in «beat» is generally pronounced for about 190 milliseconds, but the same vowel in «bead» lasts 350 milliseconds in normal speech, the voiced final consonant influencing vowel length.

Cockney English features short and long varieties of the closing diphthong [ɔʊ]. The short [ɔʊ] corresponds to RP /ɔː/ in morphologically closed syllables (see thought split), whereas the long [ɔʊː] corresponds to the non-prevocalic sequence /ɔːl/ (see l-vocalization). The following are minimal pairs of length:

| [ˈfɔʊʔ] fort/fought | [ˈfɔʊːʔ] fault | |

| [ˈpɔʊz] pause | [ˈpɔʊːz] Paul’s | |

| [ˈwɔʊʔə] water | [ˈwɔʊːʔə] Walter |

The difference is lost in running speech, so that fault falls together with fort and fought as [ˈfɔʊʔ] or [ˈfoːʔ]. The contrast between the two diphthongs is phonetic rather than phonemic, as the /l/ can be restored in formal speech: [ˈfoːɫt] etc., which suggests that the underlying form of [ˈfɔʊːʔ] is /ˈfoːlt/ (John Wells says that the vowel is equally correctly transcribed with ⟨ɔʊ⟩ or ⟨oʊ⟩, not to be confused with GOAT /ʌʊ/, [ɐɤ]). Furthermore, a vocalized word-final /l/ is often restored before a word-initial vowel, so that fall out [fɔʊl ˈæəʔ] (cf. thaw out [fɔəɹ ˈæəʔ], with an intrusive /r/) is somewhat more likely to contain the lateral [l] than fall [fɔʊː]. The distinction between [ɔʊ] and [ɔʊː] exists only word-internally before consonants other than intervocalic /l/. In the morpheme-final position only [ɔʊː] occurs (with the THOUGHT vowel being realized as [ɔə ~ ɔː ~ ɔʊə]), so that all [ɔʊː] is always distinct from or [ɔə]. Before the intervocalic /l/ [ɔʊː] is the banned diphthong, though here either of the THOUGHT vowels can occur, depending on morphology (compare falling [ˈfɔʊlɪn] with aweless [ˈɔəlɪs]).[9]

In cockney, the main difference between /ɪ/ and /ɪə/, /e/ and /eə/ as well as /ɒ/ and /ɔə/ is length, not quality, so that his [ɪz], merry [ˈmɛɹɪi] and Polly [ˈpɒlɪi ~ ˈpɔlɪi] differ from here’s [ɪəz ~ ɪːz], Mary [ˈmɛəɹɪi ~ ˈmɛːɹɪi] and poorly [ˈpɔəlɪi ~ ˈpɔːlɪi] (see cure-force merger) mainly in length. In broad cockney, the contrast between /æ/ and /æʊ/ is also mainly one of length; compare hat [æʔ] with out [æəʔ ~ æːʔ] (cf. the near-RP form [æʊʔ], with a wide closing diphthong).[9]

«Long» and «short» vowel letters in spelling and the classroom teaching of reading[edit]

«Short i» redirects here. For the Cyrillic letter, see Short I.

The vowel sounds (phonetic values) of what are called «long vowels» and «short vowels» (less confusing would be «vowel letters», as the concept being articulated is about how the letter should be read) in the teaching of reading (and therefore in everyday English) are represented in this table. The descriptions «long» and «short» are not accurate from a linguistic point of view; in the case of Modern English, as the vowels are not actually long and short versions of the same sound as they once were in Middle English, they are different sounds and therefore different vowels, as is clearly shown by their phonetic qualities.

| letter | «short» | «long» | examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | /æ/ | /eɪ/ | mat / mate |

| e | /ɛ/ | /iː/ | pet / Pete |

| i | /ɪ/ | /aɪ/ | twin / twine |

| o | /ɒ/ | /oʊ/ | not / note |

| oo | /ʊ/ | /uː/ | wood / wooed |

| u | /ʌ/ | /juː/ | cub / cube |

In English, the term «vowel» is often used to refer to vowel letters even though these often represent combinations of vowel sounds (diphthongs), approximants, and even silence, not just single vowel sounds (monophthongs). Most of this article covers the length of vowel sounds (not vowel letters) in English. Even classroom materials for teaching reading use the terms «long» and «short» in referring to vowel letters, while confusingly calling them «vowels». For example, in English spelling, vowel letters in words of the form consonant + vowel letter + consonant (CVC) are called «short» and «long» depending on whether or not they are followed by the letter e (CVC vs. CVCe) although those vowel letters called «long» actually represent combinations of two different vowels (diphthongs). Thus a vowel letter is called «long» if it is pronounced the same as the letter’s name and «short» if it is not.[10] This is commonly used for educational purposes when teaching children.

In some types of phonetic transcription (e.g. pronunciation respelling), «long» vowel letters may be marked with a macron; for example, ⟨ā⟩ may be used to represent the IPA sound /eɪ/. This is sometimes used in dictionaries, most notably in Merriam-Webster[11] (see Pronunciation respelling for English for more).

Similarly, the short vowel letters are rarely represented in teaching reading of English in the classroom by the symbols ă, ĕ, ĭ, ŏ, o͝o, and ŭ. The long vowels are more often represented by a horizontal line above the vowel: ā, ē, ī, ō, o͞o, and ū.[12][self-published source?]

Origin[edit]

Vowel length may often be traced to assimilation. In Australian English, the second element [ə] of a diphthong [eə] has assimilated to the preceding vowel, giving the pronunciation of bared as [beːd], creating a contrast with the short vowel in bed [bed].

Another common source is the vocalization of a consonant such as the voiced velar fricative [ɣ] or voiced palatal fricative or even an approximant, as the English ‘r’. A historically-important example is the laryngeal theory, which states that long vowels in the Indo-European languages were formed from short vowels, followed by any one of the several «laryngeal» sounds of Proto-Indo-European (conventionally written h1, h2 and h3). When a laryngeal sound followed a vowel, it was later lost in most Indo-European languages, and the preceding vowel became long. However, Proto-Indo-European had long vowels of other origins as well, usually as the result of older sound changes, such as Szemerényi’s law and Stang’s law.

Vowel length may also have arisen as an allophonic quality of a single vowel phoneme, which may have then become split in two phonemes. For example, the Australian English phoneme /æː/ was created by the incomplete application of a rule extending /æ/ before certain voiced consonants, a phenomenon known as the bad–lad split. An alternative pathway to the phonemicization of allophonic vowel length is the shift of a vowel of a formerly-different quality to become the short counterpart of a vowel pair. That too is exemplified by Australian English, whose contrast between /a/ (as in duck) and /aː/ (as in dark) was brought about by a lowering of the earlier /ʌ/.

Estonian, a Finnic language, has a rare[citation needed] phenomenon in which allophonic length variation has become phonemic after the deletion of the suffixes causing the allophony. Estonian had already inherited two vowel lengths from Proto-Finnic, but a third one was then introduced. For example, the Finnic imperative marker *-k caused the preceding vowels to be articulated shorter. After the deletion of the marker, the allophonic length became phonemic, as shown in the example above.

Notations in the Latin alphabet[edit]

IPA[edit]

In the International Phonetic Alphabet the sign ː (not a colon, but two triangles facing each other in an hourglass shape; Unicode U+02D0) is used for both vowel and consonant length. This may be doubled for an extra-long sound, or the top half (ˑ) may be used to indicate that a sound is «half long». A breve is used to mark an extra-short vowel or consonant.

Estonian has a three-way phonemic contrast:

- saada [saːːda] «to get» (overlong)

- saada [saːda] «send!» (long)

- sada [sada] «hundred» (short)

Although not phonemic, a half-long distinction can also be illustrated in certain accents of English:

- bead [biːd]

- beat [biˑt]

- bid [bɪˑd]

- bit [bɪt]

Diacritics[edit]

- Macron (ā), used to indicate a long vowel in Māori, Hawaiian, Samoan, Latvian and many transcription schemes, including romanizations for Sanskrit and Arabic, the Hepburn romanization for Japanese, and Yale for Korean. While not part of their standard orthography, the macron is used as a teaching aid in modern Latin and Ancient Greek textbooks. Macron is also used in modern official Cyrillic orthographies of some minority languages (Mansi,[13] Kildin Sami, Evenki).

- Breves (ă) are used to mark short vowels in several linguistic transcription systems, as well as in Vietnamese and Alvarez-Hale’s orthography for O’odham language.

- Acute accent (á), used to indicate a long vowel in Czech, Slovak, Old Norse, Hungarian, Irish, traditional Scottish Gaelic (for long [oː] ó, [eː] é, as opposed to [ɛː] è, [ɔː] ò) and pre-20th-century transcriptions of Sanskrit, Arabic, etc.

- Circumflex (â), used for example in Welsh. The circumflex is occasionally used as a surrogate for the macrons, particularly in Hawaiian and in the Kunrei-shiki romanization of Japanese, or in transcriptions of Old High German. In transcriptions of Middle High German, a system where inherited lengths are marked with the circumflex and new lengths with the macron is occasionally used.

- Grave accent (à) is used in Scottish Gaelic, with a e i o u. (In traditional spelling, [ɛː] is è and [ɔː] is ò as in gnè, pòcaid, Mòr (personal name), while [eː] is é and [oː] is ó, as in dé, mór.)

- Ogonek (ą), used in Lithuanian to indicate long vowels.

- Trema (ä), used in Aymara to indicate long vowels.

Additional letters[edit]

- Vowel doubling, used consistently in Estonian, Finnish, Lombard, Navajo and Somali, and in closed syllables in Dutch, Afrikaans, and West Frisian. Example: Finnish tuuli /ˈtuːli/ ‘wind’ vs. tuli /ˈtuli/ ‘fire’.

- Estonian also has a rare «overlong» vowel length but does not distinguish it from the normal long vowel in writing, as they are distinguishable by context; see the example below.

- Consonant doubling after short vowels is very common in Swedish and other Germanic languages, including English. The system is somewhat inconsistent, especially in loanwords, around consonant clusters and with word-final nasal consonants. Examples:

- Consistent use: byta /²byːta/ ‘to change’ vs bytta /²bʏtːa/ ‘tub’ and koma /²koːma/ ‘coma’ vs komma /²kɔma/ ‘to come’

- Inconsistent use: fält /ˈfɛlt/ ‘a field’ and kam /ˈkamː/ ‘a comb’ (but the verb ‘to comb’ is kamma)

- Classical Milanese orthography uses consonant doubling in closed short syllables, e.g., lenguagg ‘language’ and pubblegh ‘public’.[14]

- ie is used to mark the long /iː/ sound in German because of the preservation and the generalization of a historic ie spelling, which originally represented the sound /iə̯/. In Low German, a following e letter lengthens other vowels as well, e.g., in the name Kues /kuːs/.

- A following h is frequently used in German and older Swedish spelling, e.g., German Zahn [tsaːn] ‘tooth’.

- In Czech, the additional letter ů is used for the long U sound, and the character is known as a kroužek, e.g., kůň «horse». (It actually developed from the ligature «uo», which noted the diphthong /uo/ until it shifted to /uː/.)

Other signs[edit]

- Colon, ⟨꞉⟩, from Americanist phonetic notation, and used in orthographies based on it such as Oʼodham, Mohawk or Seneca. The triangular colon ⟨ː⟩ in the International Phonetic Alphabet derives from this.

- Middot or half-colon, ⟨ꞏ⟩, a more common variant in the Americanist tradition, also used in language orthographies.

- Saltillo (straight apostrophe), used in Miꞌkmaq, as evidenced by the name itself. This is the convention of the Listuguj orthography (Miꞌgmaq), and a common substitution for the acute accent (Míkmaq) of the Francis-Smith orthography.

No distinction[edit]

Some languages make no distinction in writing. This is particularly the case with ancient languages such as Latin and Old English. Modern edited texts often use macrons with long vowels, however. Australian English does not distinguish the vowels /æ/ from /æː/ in spelling, with words like ‘span’ or ‘can’ having different pronunciations depending on meaning.

Notations in other writing systems[edit]

In non-Latin writing systems, a variety of mechanisms have also evolved.

- In abjads derived from the Aramaic alphabet, notably Arabic and Hebrew, long vowels are written with consonant letters (mostly approximant consonant letters) in a process called mater lectionis e.g. in Modern Arabic the long vowel /aː/ is represented by the letter ا (Alif), the vowels /uː/ and /oː/ are represented by و (wāw), and the vowels /iː/ and /eː/ are represented by ي (yāʼ), while short vowels are typically omitted entirely. Most of these scripts also have optional diacritics that can be used to mark short vowels when needed.

- In South-Asian abugidas, such as Devanagari or the Thai alphabet, there are different vowel signs for short and long vowels.

- Ancient Greek also had distinct vowel signs, but only for some long vowels; the vowel letters η (eta) and ω (omega) originally represented long forms of the vowels represented by the letters ε (epsilon, literally «bare e«) and ο (omicron – literally «small o«, by contrast with omega or «large o«). The other vowel letters of Ancient Greek, α (alpha), ι (iota) and υ (upsilon), could represent either short or long vowel phones.

- In the Japanese hiragana syllabary, long vowels are usually indicated by adding a vowel character after. For vowels /aː/, /iː/, and /uː/, the corresponding independent vowel is added. Thus: あ (a), おかあさん, «okaasan», mother; い (i), にいがた «Niigata», city in northern Japan (usually 新潟, in kanji); う (u), りゅう «ryuu» (usu. 竜), dragon. The mid-vowels /eː/ and /oː/ may be written with え (e) (rare) (ねえさん (姉さん), neesan, «elder sister») and お (o) [おおきい (usu 大きい), ookii, big], or with い (i) (めいれい (命令), «meirei», command/order) and う (u) (おうさま (王様), ousama, «king») depending on etymological, morphological, and historic grounds.

- Most long vowels in the katakana syllabary are written with a special bar symbol ー (vertical in vertical writing), called a chōon, as in メーカー mēkā «maker» instead of メカ meka «mecha». However, some long vowels are written with additional vowel characters, as with hiragana, with the distinction being orthographically significant.

- In the Korean Hangul alphabet, vowel length is not distinguished in normal writing. Some dictionaries use a double dot, ⟨:⟩, for example 무: «Daikon radish».

- In the Classic Maya script, also based on syllabic characters, long vowels in monosyllabic roots were generally written with word-final syllabic signs ending in the vowel —i rather than an echo-vowel. Hence, chaach «basket», with a long vowel, was written as cha-chi (compare chan «sky», with a short vowel, written as cha-na). If the nucleus of the syllable was itself i, however, the word-final vowel for indicating length was —a: tziik— «to count; to honour, to sanctify» was written as tzi-ka (compare sitz’ «appetite», written as si-tz’i).

See also[edit]

- Gemination

- Length (phonetics)

References[edit]

- ^ Liddell, H. G., and R. Scott (1996). A Greek-English Lexicon (revised 9th ed. with supplement). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.1

- ^ Odden, David (2011). The Representation of Vowel Length. In Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume, & Keren Rice (eds.) The Blackwell Companion to Phonology. Wiley-Blackwell, 465-490.

- ^ Wells, John C (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (2011). The Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, J.C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. p. xxiii.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (1967). An Outline of English Phonetics (9th ed.). Heffer. p. 63.

- ^ Giegerich, H. (1992). English phonology: an introduction. Cambridge. p. para 3.3.

- ^ Kluender, Keith; Diehl, Randy; Wright, Beverly (1988). Vowel-length Differences Before Voiced and Voiceless Consonants: An Auditory Explanation. Journal of Phonetics. p. 153.

- ^ a b Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52128540-2.

- ^ «Part 3: Reading: Foundational Skills». www.mheonline.com. McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ «Guide to Pronunciation» (PDF). Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ^ «Short Vowels and Long Vowels Lesson Plan».

- ^ «OB-UGRIC LANGUAGES: CONCEPTUAL STRUCTURES, LEXICON, CONSTRUCTIONS, CATEGORIES TRANSLITERATION TABLES FOR NORTHERN MANSI : Counterparts of Cyrillic, FUT Counterparts of Cyrillic, FUT Cyrillic, FUT and IPA characters and IPA characters and IPA characters for Northern Mansi» (PDF). Babel.gwi.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Carlo Porta on the Italian Wikisource

External links[edit]

- Some Features of the Vernacular Finnish of Jyväskylä

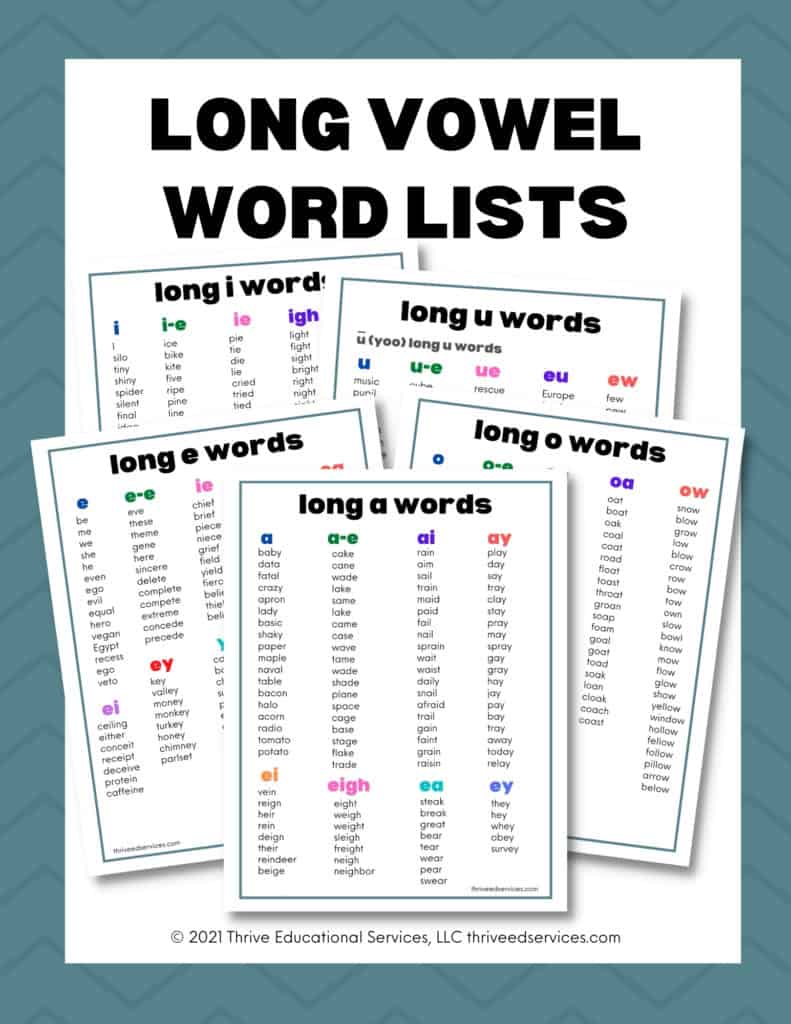

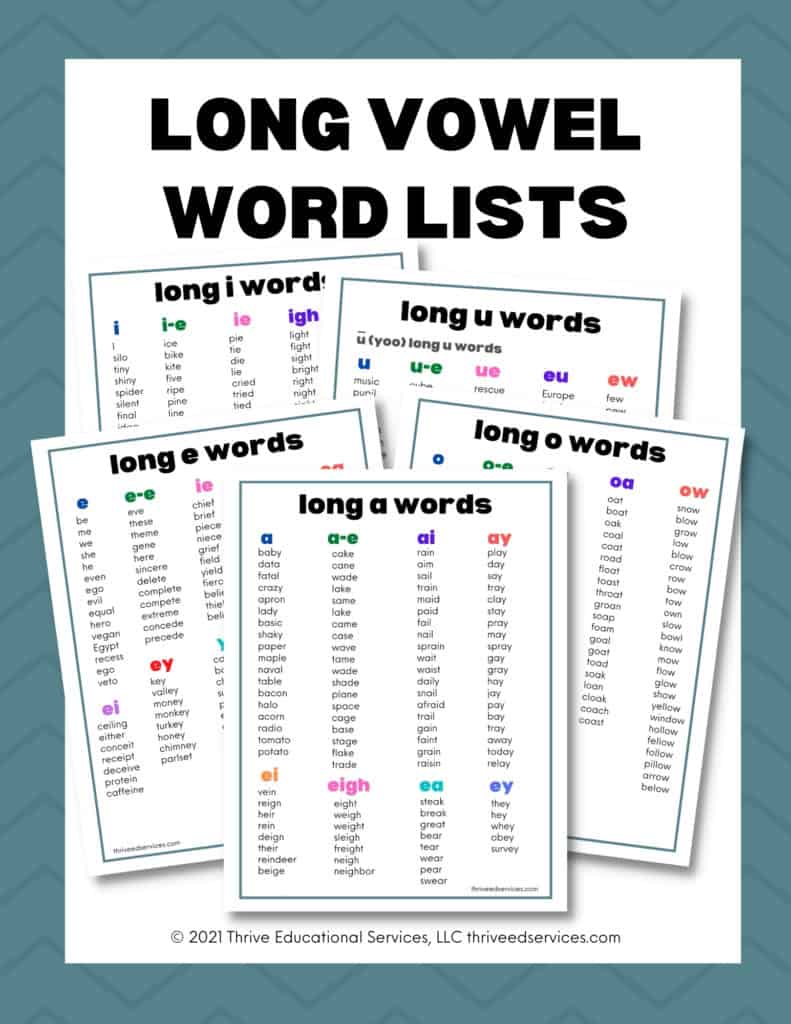

In this post, I’m breaking down long vowel sounds (or long vowel words) to help you teach them when working with struggling readers and spellers.

Looking for long vowel word lists? Download all 5 of my pdf long vowel sounds word lists in my freebies library by joining my email list below.

What is a long vowel sound?

Long vowel sounds are vowels that are pronounced the same as their name. You’ll often hear teachers say that long vowels “say their name”.

Long vowels are very common but they can be tricky because there are so many spellings for each long vowel sound.

There are actually 4 ways to make long vowel sounds:

- Vowels at the end of a syllable make the long sound. For example, in the words me and halo (ha-lo) the vowels are all at the end of a syllable so they make the long sound.

- Silent e makes the previous vowel long. The words bike and phone have a silent e at the end that makes the previous vowel long.

- Vowel teams can make the long sound. Vowel teams work together to make one sound, and usually, it’s a long vowel sound. For example, boat and meat both have vowel teams that make the long sound.

- I or O can be long when they come before two consonants. In words like cold and mind, i and o make a long vowel sound.

Long Vowel Words

Long vowel sound words are words that have vowels that say their name. Below are a few examples:

- Long a – baby, cake, rain, day, they, weigh

- Long e – me, eve, hear, meet, piece, candy

- Long i – silent, bike, light, my

- Long o – go, home, toe, boat, snow

- Long u – music, mule, pew, feud

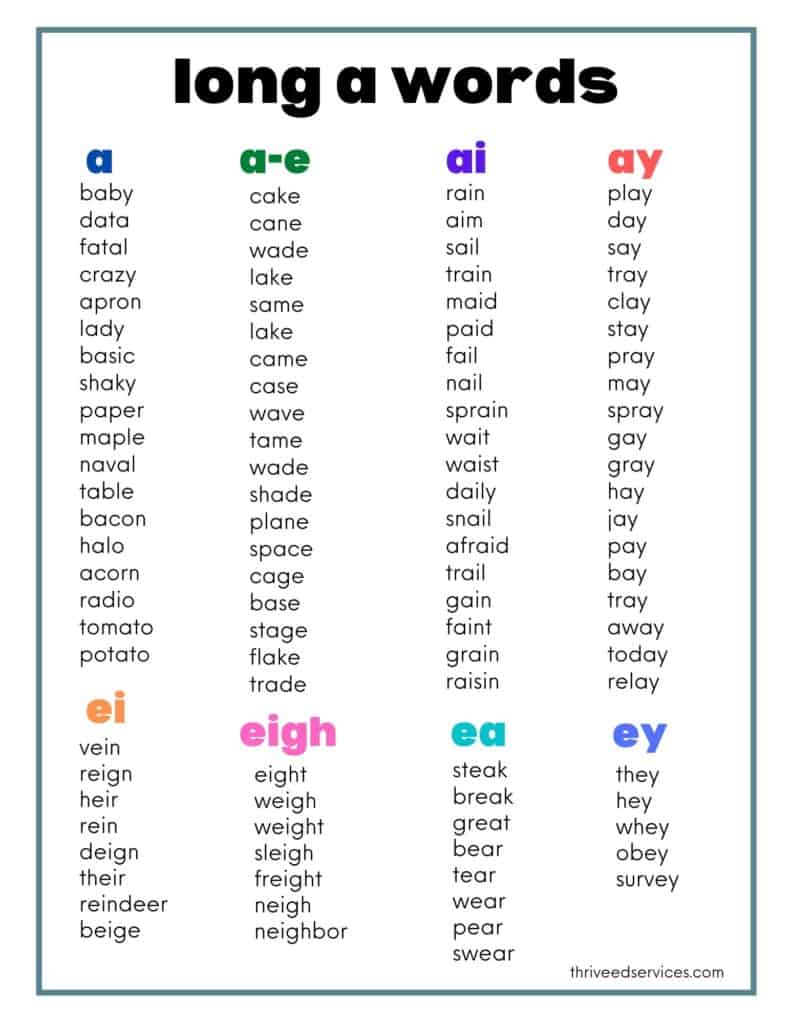

Long A Sound

The long a sound can be represented by 8 different spelling patterns:

- a – baby

- a_e – cake

- ai – rain

- ay – play

- ei – reindeer

- eigh – weight

- ea – steak

- ey – they

Learn more about teaching the long a sound here, and check out my Long A Words Activities & Worksheets for printable activities.

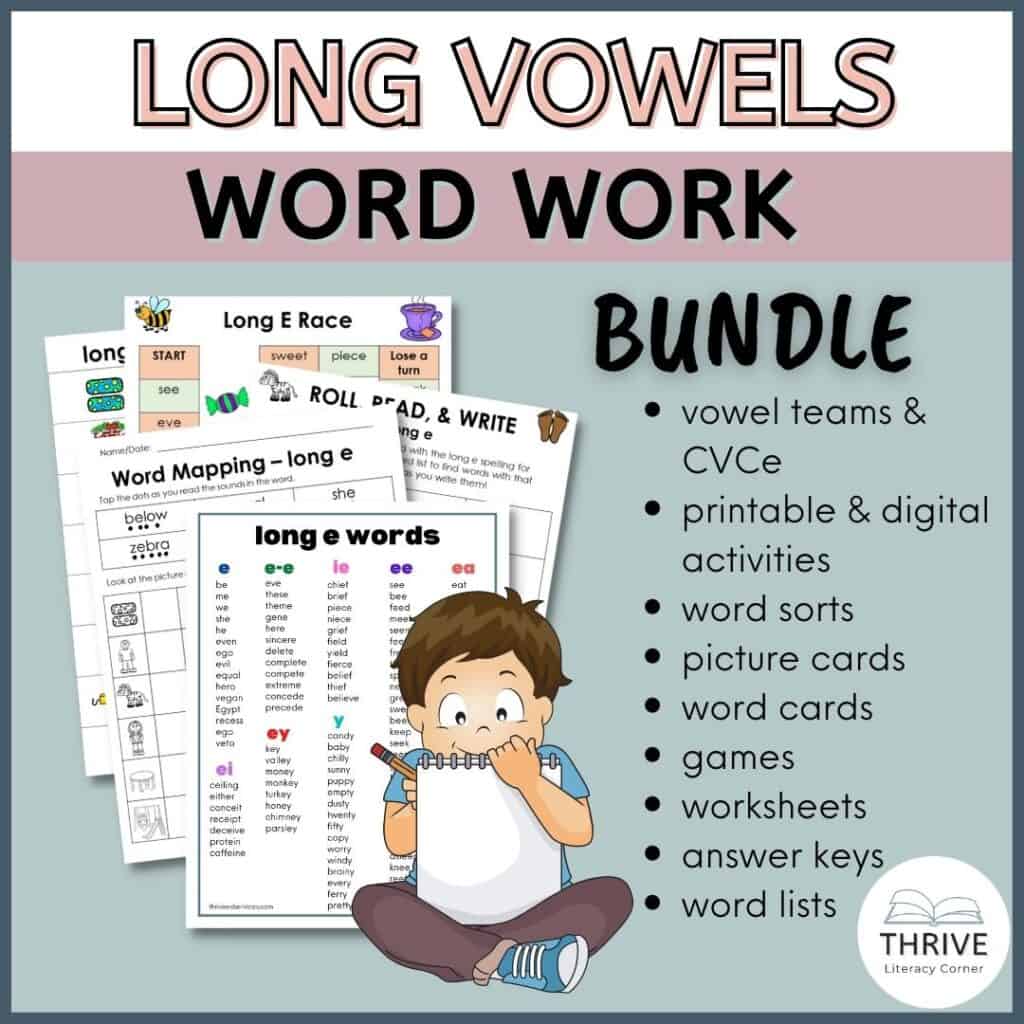

Long E Sound

The long e sound can be represented by 8 different spelling patterns:

- e – be

- e_e – eve

- ee – meet

- ea – beach

- ei – protein

- ie – piece

- ey – key

- y – candy

For ideas, tips, and tricks when teaching the long e sound, read this post all about teaching the long e vowel sound, and check out my Long E Words Activities & Worksheets for printable activities.

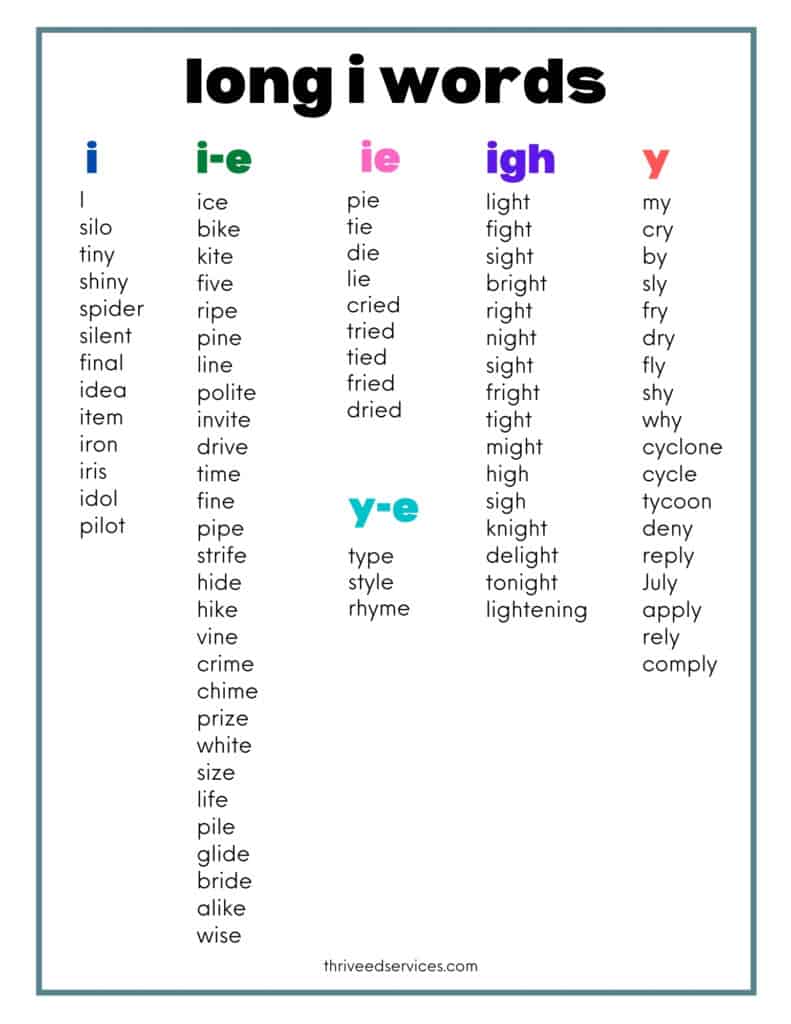

Long I Sound

The long i sound can be represented by 6 different spelling patterns:

- i – silent

- i_e – shine

- ie – pie

- igh – light

- y – my

- y_e – type

You can learn more about teaching the long I sound in this post. And check out my Long I Worksheets set in my shop for printable activities on the long i sound.

Long O Sound

The long o sound can be represented by 5 different spelling patterns:

- o – go

- o_e – phone

- oe – toe

- oa – boat

- ow – snow

You can learn more about teaching long o words and check out my long o worksheets.

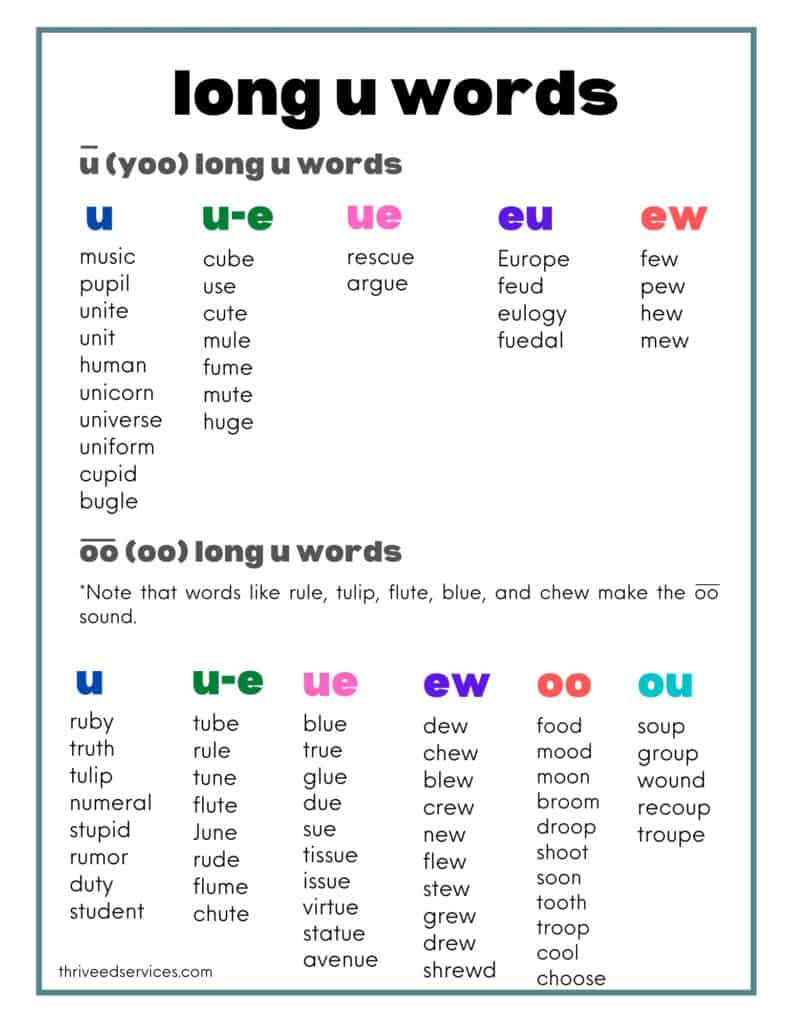

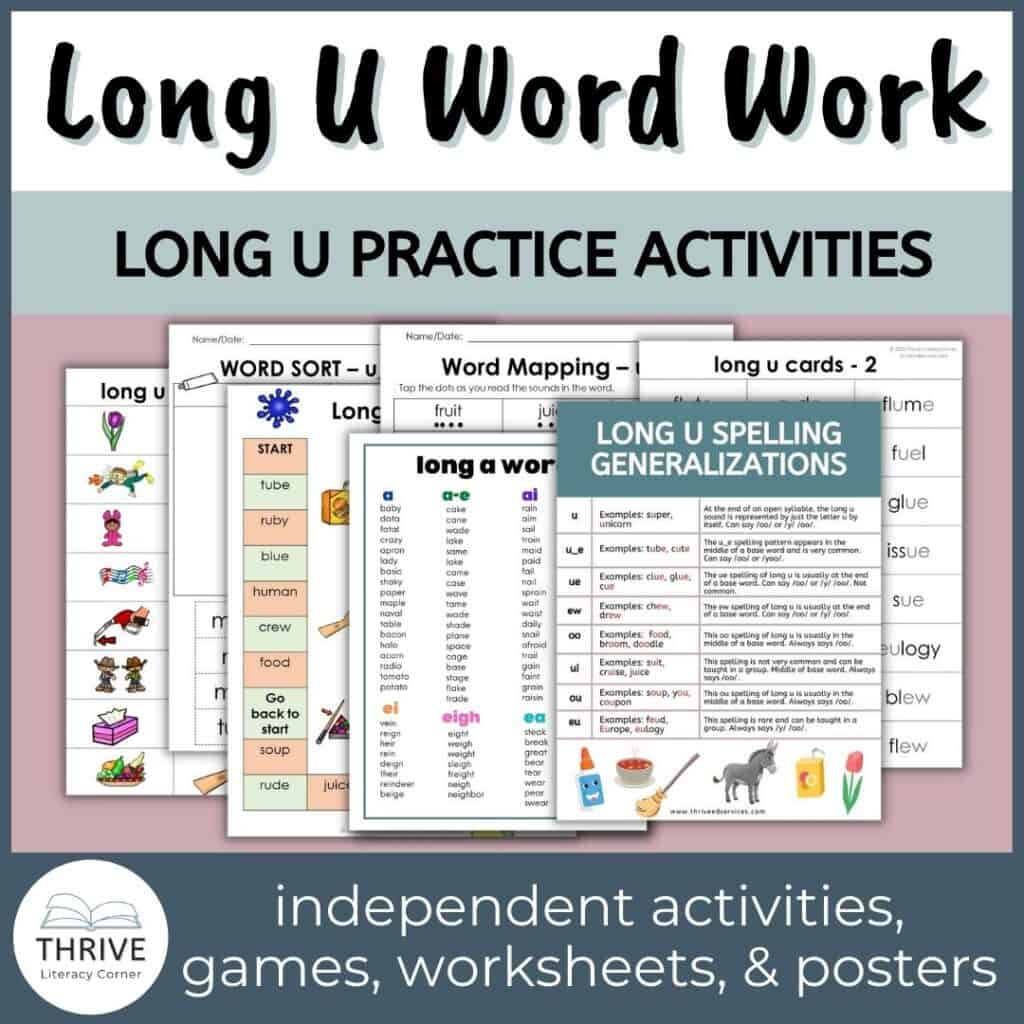

Long U Sound

The long u has two sounds: yoo (/y/ /oo/) and oo (/oo/).

The long u sound can be represented by 7 different spelling patterns:

- u – music

- u_e – mule

- ue – rescue

- eu – feud

- ew – few

- oo – food

- ou – soup

Learn more about teaching the long u sound here.

Tips for teaching the long vowel sounds

Teach one spelling pattern at a time!

I don’t mean one vowel sound, but just one spelling pattern. So for example, if you’re working on long a, you would work on the spelling pattern a silent e (cake, same, cave) until students have mastered it, then move on to ai, and so on. You should not be teaching multiple spelling patterns together, even though they make the same sound.

I know that most programs out there combine all the long vowel sound spelling patterns into one lesson, especially in spelling lists, but this does not work for struggling readers. You need to break it down for them and only do one at a time.

Teach the syllable types.

Because syllables have a lot to do with whether vowels make the short or long sound, if students do not already know the 6 syllable types then teach them along with the long vowel sound.

Here are resources for each syllable type:

- closed syllable

- open syllable

- final silent e syllable

- vowel team syllable

- r combination syllable

- consonant le syllable

Use a variety of activities to practice each spelling pattern.

Games, dictation, word sorts, memory or matching with flashcards, word hunts, textured writing, body spelling, and bingo are all fun ways to practice the long vowel sounds.

The main activity that is often overlooked is dictation. It seems so simple but the task involves listening to a word, deciding on the spelling, and transferring that info to written form. These are all skills that struggling readers need to practice.

Teach the spelling generalizations.

Some of the long vowel spelling patterns are spelling rules that make it easy to remember.

For example, ai is usually found at the beginning or middle of a syllable, and ay is usually found at the end of a syllable. [Examples: rain, aim, play, daytime]

Here is another example with long o: oa is usually found at the beginning or middle of a word, and ow is usually found at the end. [Examples: boat, coach, snow]

I made these word lists to help teach the long vowels. I find it handy to have these on hand when playing phonics games or planning activities for long vowel lessons.

Grab them for free below!

Visit my Teachers Pay Teachers shop to see all my literacy products.

Want to remember this? Save Long Vowel Sounds: Word Lists & Activities to your favorite Pinterest board!

Delilah Orpi is the founder of Thrive Literacy Corner. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Special Education, a Master’s degree in TESOL, and is a member of the International Dyslexia Association. She is an experienced educator and literacy specialist trained in Orton Gillingham and Lindamood Bell. Delilah creates literacy resources for educators and parents and writes to create awareness about dyslexia and effective literacy instruction based on the science of reading.

We all know that the English vowels are A, E, I, O, and U, but it might be hard to understand exactly why this concept is so important.

So what exactly makes a letter a vowel?

The short answer is that vowels are speech sounds that you can pronounce without restricting the flow of air from the lungs.

This article will explain how vowels work and why they’re so important.

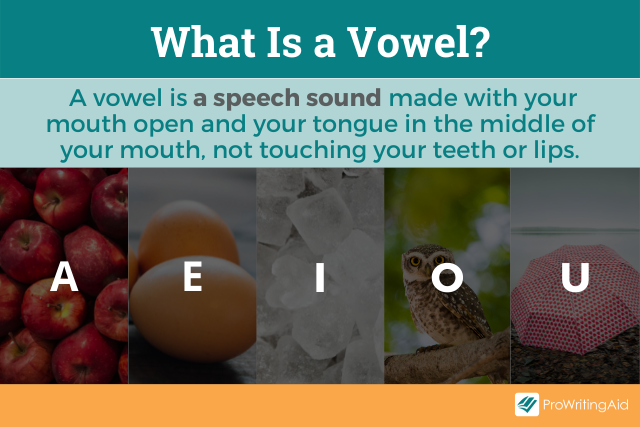

What Is a Vowel?

Vowel Definition

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a vowel is a speech sound made with your mouth open and your tongue in the middle of your mouth, not touching your teeth or lips.

Vowel Meaning

A vowel is a speech sound made without a significant constriction of the flow of air from the lungs.

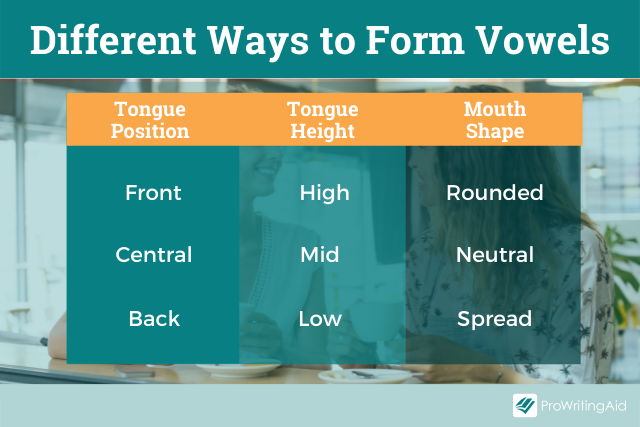

Every vowel sound is made by shaping the mouth in a specific way without blocking the airflow. You can create unique sounds by placing your tongue in various different positions (front, central, or back) and at various heights (high, mid, or low). You can also change the shape of your lips (rounded, neutral, or spread).

One way to help understand this concept is by opening your mouth and saying “ahh.” Now try changing the shape of your mouth without blocking the flow of air. If you stretch your mouth wider into a spread shape, you make more of an “e” sound. If you round your lips, you make more of an “o” sound. When you change the position of your tongue, those sounds change as well. Congratulations—you’re making different vowels!

As soon as you restrict or close your airflow, you start making a consonant. For example, if you bring your lips together you create a consonant such as “b” or “p.” If you touch your tongue to the top of your mouth, you create a consonant such as “k” or “g.” If you put your tongue between your teeth, you make a sound like “th.”

Blocking the airflow is the difference between a vowel and a consonant.

Vowel Letters

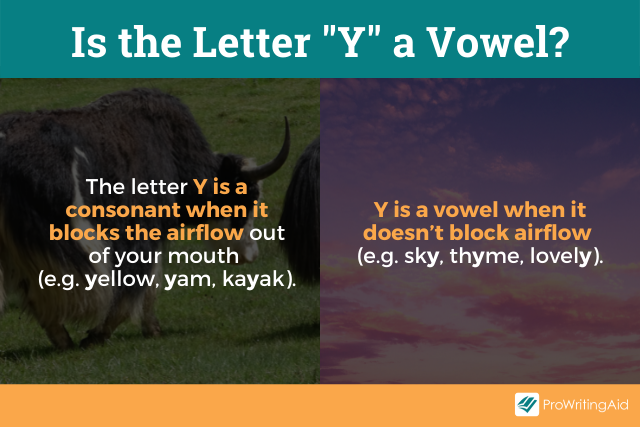

The English language includes six vowel letters: A, E, I, O, U, and sometimes Y.

The letter Y is only sometimes a vowel because it can be pronounced as a consonant (such as in the words “yellow,” “yam,” and “kayak”) and sometimes as a vowel (such as in the words “sky,” “thyme,” and “lovely”).

It’s a consonant when it involves blocking the airflow out of your mouth, and it’s a vowel when it doesn’t.

Here are some examples of vowel letters in common English words:

- Unit: the vowel letters are “u” and “i”

- Chocolate: the vowel letters are “o,” “o,” “a,” and “e”

- Rainy: the vowel letters are “a,” “i,” and “y”

Vowel Sounds

Even though we only have five vowel letters in English (A, E, I, O, U, and sometimes Y), we actually have a lot more than five vowel sounds.

Each vowel letter can be used to express more than one sound. For example, the letter “a” can be pronounced like the “a” in “rate” or like the “a” in “rat.”

Furthermore, we can represent vowels by combining the five vowel letters in different ways. Sometimes we combine two vowels together to make a specific sound, such as “ai” and “au.” Other times, we combine a vowel with a consonant, such as “ah” and “an.”

Here are some examples of vowel sounds in English words. Notice how they’re different from the vowel letters themselves.

- Unit: the vowel sounds are created by “u” and “i”

- Chocolate: the vowel sounds are created by “o”, “o”, and “a.” The “e” at the end is silent

- Rainy: the vowel sounds are created by “ai” and “y”

Why Are Vowels so Important in English?

Vowels are a crucial part of our language. Without them, we wouldn’t be able to speak or sing.

They’re also important for learning how to read and write English. Every beginner reader needs to learn vowels in order to sound out written words, since each syllable contains a vowel sound.

Let’s look more closely at the reasons why vowels are so important.

You Need Vowels to Cry, Laugh, and Sing

The human mouth is designed to include vowels in our speech sounds. We create vowel sounds even when we laugh or cry, regardless of the native language we speak.

We also need vowels to sing. Try singing a consonant sound like “k” or “t” or “b.”

You’ll quickly find that it’s impossible to sing a consonant without using a vowel. For example, you can sing the sound “kay” or the sound “tee,” but that’s because you’re singing the vowel sounds “ay” and “ee.” The consonants “k” and “t” only last for a moment.

If you pay attention to professional singers you’ll notice that they often draw out the vowel sounds, ending on consonants only at the very end. Unless you’re humming, you need to use vowels to sustain a sound for a long time.

Every Word and Syllable Needs a Vowel

Every syllable in the English language contains a vowel sound.

If you want to figure out how many syllables there are in a word, an easy method is to count the number of vowel sounds there are.

For example, say the word “tomato.” It has three syllables: to-ma-to. Here, the vowel sounds are “o,” “a,” and “o.”

Or say the word “counted.” It has two syllables: coun-ted. Here, the vowel sounds are “ou” and “e.”

You can have words and syllables without consonants, such as “I” or “oh”, but you can’t have a word without vowels. In a way, vowels are the heart of language—they’re the most basic component of the way we speak.

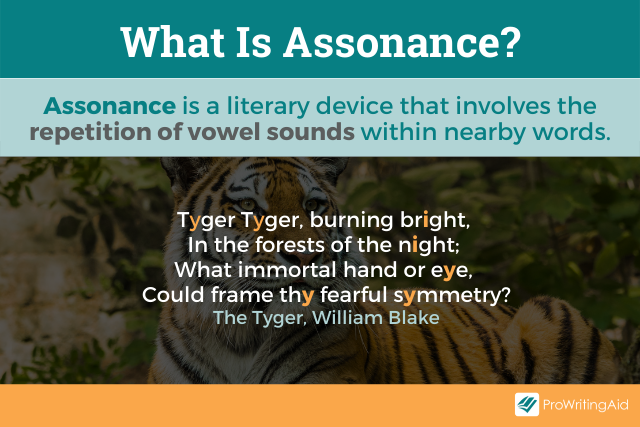

You Need Vowels to Create Assonance

Assonance is a literary device that involves the repetition of vowel sounds within nearby words. This device creates rhythm and helps writing to flow in a more musical way.

For example, consider this famous line from William Blake’s “Tyger”: “Tyger, Tyger burning bright in the forest of the night.” Here, the long “i” sound is repeated over and over. You hear it in “tyger,” “bright,” and “night.”

Another example is from the movie My Fair Lady: “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain.” Here, the long “a” sound is repeated over and over in “rain,” “Spain,” “stays,” “mainly,” and “plain.”

If you’re writing or reading poetry, you should pay attention to vowel sounds. You can make your poem more musical by using similar sounds in interesting patterns.

Origins of the Word Vowel

The word “vowel” originates from the Latin word “vox,” which means “voice.”

In contrast, the word “consonant” originates from the Latin words for “with sound”: con (“with”) and sonare (“to sound”).

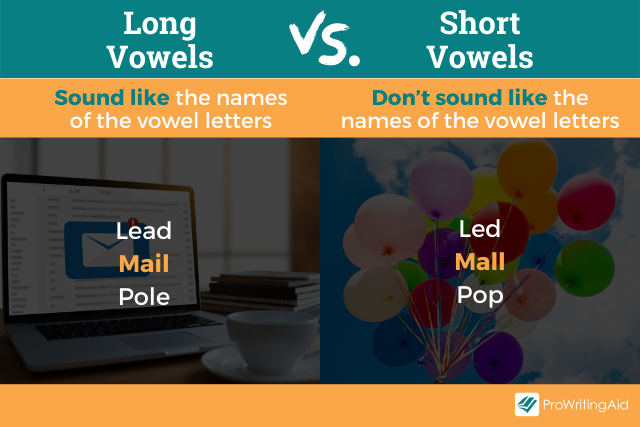

The Difference Between Short & Long Vowels

There are two types of vowel sounds: long vowels and short vowels.

The names of vowels are long vowel sounds. Think of the way you pronounce the letters A, E, I, O, and U when you’re singing the alphabet song. These are long vowels.

Here are some examples of long vowels in words:

- The “e” in “lead”

- The “a” in “mail”

- The “o” in “pole”

Whenever a vowel isn’t pronounced the way its name sounds, that means it’s a short vowel sound.

Here are some examples of short vowels in words:

- The “e” in “led”

- The “a” in “ball”

- The “o” in “pop”

It’s important to understand the difference between long and short vowels when you’re reading so you can pronounce the words correctly.

Long vowel sounds are often created by ending the word with a silent “e.” For example, the “a” in “hate” is a long vowel, while the “a” in “hat” is not.

Other times, long vowel sounds can be created by placing two vowels next to each other. For example, the “e” in “beat” is a long vowel, while the “e” in “bet” is not.

When a vowel appears by itself, it’s often pronounced as a short vowel, though this isn’t always the case. Practicing reading and pronouncing various English words is the best way to gain an intuitive understanding of how to pronounce each vowel.

Do Vowels Exist in Other Languages?

Every language has vowels, though some languages have more than others. For example, Japanese has only five vowel sounds, while Danish has 32.

Which words do you think have the strangest vowel pronunciations? Let us know in the comments.

Ready to Improve Your Writing? Try ProWritingAid.

Our editing software remembers 1000s of grammar rules so you don’t have to.

Sign up for a free account to get started.

Vowels and consonants are two types of letters in the English alphabet. A vowel sound is created when air flows smoothly, without interruption, through the throat and mouth. Different vowel sounds are produced as a speaker changes the shape and placement of articulators (parts of the throat and mouth).

In contrast, consonant sounds happen when the flow of air is obstructed or interrupted. If this sounds confusing, try making the “p” sound and the “k” sound. You will notice that in creating the sound you have manipulated your mouth and tongue to briefly interrupt airflow from your throat. Consonant sounds have a distinct beginning and end, while vowel sounds flow.

The pronunciation of each vowel is determined by the position of the vowel in a syllable, and by the letters that follow it. Vowel sounds can be short, long, or silent.

Short Vowels

If a word contains only one vowel, and that vowel appears in the middle of the word, the vowel is usually pronounced as a short vowel. This is especially true if the word is very short. Examples of short vowels in one-syllable words include the following:

- At

- Bat

- Mat

- Bet

- Wet

- Led

- Red

- Hit

- Fix

- Rob

- Lot

- Cup

- But

This rule can also apply to one-syllable words that are a bit longer:

- Rant

- Chant

- Slept

- Fled

- Chip

- Strip

- Flop

- Chug

When a short word with one vowel ends in s, l, or f, the end consonant is doubled, as in:

- Bill

- Sell

- Miss

- Pass

- Jiff

- Cuff

If there are two vowels in a word, but the first vowel is followed by a double consonant, the vowel’s sound is short, such as:

- Matter

- Cannon

- Ribbon

- Wobble

- Bunny

If there are two vowels in a word and the vowels are separated by two or more letters, the first vowels is usually short, for example:

- Lantern

- Basket

- Ticket

- Bucket

Long Vowels

The long vowel sound is the same as the name of the vowel itself. Follow these rules:

- Long A sound is AY as in cake.

- Long E sound is EE an in sheet.

- Long I sound is AHY as in like.

- Long O sound is OH as in bone.

- Long U sound is YOO as in human or OO as in crude.

Long vowel sounds are often created when two vowels appear side by side in a syllable. When vowels work as a team to make a long vowel sound, the second vowel is silent. Examples are:

- Rain

- Seize

- Boat

- Toad

- Heap

A double “e” also makes the long vowel sound:

- Keep

- Feel

- Meek

The vowel “i” often makes a long sound in a one-syllable word if the vowel is followed by two consonants:

- Blight

- High

- Mind

- Wild

- Pint

This rule does not apply when the “i” is followed by the consonants th, ch, or sh, as in:

- Fish

- Wish

- Rich

- With

A long vowel sound is created when a vowel is followed by a consonant and a silent “e” in a syllable, as in:

- Stripe

- Stake

- Concede

- Bite

- Size

- Rode

- Cute

The long “u” sound can sound like yoo or oo, such as:

- Cute

- Flute

- Lute

- Prune

- Fume

- Perfume

Most often, the letter “o” will be pronounced as a long vowel sound when it appears in a one-syllable word and is followed by two consonants, as in these examples:

- Most

- Post

- Roll

- Fold

- Sold

A few exceptions occur when the “o” appears in a single syllable word that ends in th or sh:

- Posh

- Gosh

- Moth

Weird Vowel Sounds

Sometimes, combinations of vowels and consonants (like Y and W) create unique sounds. The letters oi can make an OY sound when they appear in the middle of a syllable:

- Boil

- Coin

- Oink

The same sound is made with the letters “oy” when they appear at the end of a syllable:

- Ahoy

- Boy

- Annoy

- Soy

Similarly, the letters “ou” make a distinct sound when they appear in the middle of a syllable:

- Couch

- Rout

- Pout

- About

- Aloud

The same sound can be made by the letters «ow» when they appear at the end of a syllable:

- Allow

- Plow

- Endow

The long “o” sound is also created by the letters “ow” when they appear at the end of a syllable:

- Row

- Blow

- Slow

- Below

The letters «ay» make the long “a” sound:

- Stay

- Play

- Quay

The letter Y can make a long “i” sound if it appears at the end of a one-syllable word:

- Shy

- Ply

- Try

- Fly

The letters ie can make a long “e” sound (except after c):

- Belief

- Thief

- Fiend

The letters ei can make the long “e” sound when they follow a “c”:

- Receive

- Deceive

- Receipt

The letter “y” can make a long e sound if it appears at the end of a word and it follows one or more consonants:

- Bony

- Holy

- Rosy

- Sassy

- Fiery

- Toasty

- Mostly