1. Word Wall

To help your students get more engaged in vocabulary development, you need to nurture word consciousness. This means raising students’ awareness of, and interest in all sorts of words and their meanings.

A Word Wall can help you achieve this. This is a collection of words that are displayed in large visible letters on a wall, bulletin board, or other display surfaces in a classroom.

Source: ELL STRATEGIES & MISCONCEPTIONS

So, set this wall and encourage your students ‘to walk the wall’ and hang their favourite words, new or unknown, on it.

Then, invite their classmates to add sticky notes with pictures or graphics, synonyms, antonyms, or related words. Then, student partners walk along the wall to quiz each other on the words (Graves & Watts-Taffe,2008).

Use the Word Wall one or more times a week. You’ll help your students make connections between new and known words.

Since this is an ongoing activity during the whole year, you can keep observational notes of those students who are posting, responding to their words and those who are not adding words to the wall.

This will help you better understand what your students need to expand their vocabulary.

2. Word Box

Word Box is one of the strategies for teaching vocabulary. This is a weekly strategy that can help students retain and use words more effectively.

Students select words to submit to the word box on Friday. These are words they find interesting or ones they want to understand better. They either use the word in their own sentence or take the same sentence where this word was found.

Then, select five words to teach the following week.

Monday: Introduce the five words in context, explain them, then tack them to the Word Wall.

Tuesday: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the words.

Wednesday: Discuss the meaning of the words allowing think-pair-shares.

Thursday: Ask students to write sentences using those words.

Friday: This is the day to assess students’ learning of the five words using this activity.

Ask one student to answer fill-ins for five words. Give students three cards that can hold up: green cards show they agree with the student’s answer, yellow they are unsure and red ones they disagree.

For assessing, use a checklist with the vocabulary running horizontally across the top margin and the class list running vertically down the side. (Adapted from Grant et al., 2015, p.195)

3. Vocabulary Notebooks

Ask your students to maintain vocabulary notebooks throughout the year where they write the meaning of the new words.

You can introduce a new word each week and work together with students to explore its meaning. Then, ask them to sketch a picture to illustrate the word and present their drawings to the class at the end of the week.

Another way to use vocabulary notebooks :

Students create a chart. The first column indicates the word, where it was found, and the sample sentence in which it appeared.

The other columns depend on your students’ needs.

You can include a column for meaning ( where students define the word or add a synonym), for word parts and related word forms (where they identify the parts and list any other words related to it), a picture, other occurrences (if they have seen or heard this word before, they describe where) and for practice or how they used this word. (Lubliner, 2005)

4. Semantic Mapping

These are maps or webs of words that can help visually display the meaning-based connections between a word or phrase and a set of related words or concepts.

Teach your students how to use semantic mapping. Pick a word you intend to explain, draw a map or web on the board ( or on Zoom whiteboard or any digital tool in case you’re teaching online) and put this word in the centre of the map. Then, ask students to add related words or phrases similar in meaning to the new word. (see the example below)

Source:weebly.com

5. Word Cards

Word cards can help students review frequently learned words and so improve retention.

On one side of the card, students write the target word and its part of speech (whether it’s a verb, noun, adjective, etc.).

On the top half of the other side, they write the word’s definition (in English and/ or a translation). They also write an example and a description of its pronunciation. The bottom half of the card can be used for additional notes once they start using the word.

Ask students to add more information about the word each time they practise or observe it (sentences, collocations, etc.).

Yet, advise them not to add too much information in order to facilitate more reviewing the cards.

Devote regularly class time for students to bring their word cards to class. Involve them in activities such as describing the new words, quizzing one another, categorizing them according to subject or part of speech.

Also, show your students how to store and organize those cards. This is, for instance, by putting them into a box with the categories they select or ordering them in terms of difficulty. (Schmitt & Schmitt, 2005)

6. Word Learning Strategies

Our students often have only partial knowledge of the words they learn in the classroom. This is so since a word can have different meanings which they may not be familiar with.

Therefore, teaching students word learning strategies is important to help them become independent word learners. This is by teaching, modelling and providing a variety of strategies that serve different purposes.

Here are some examples of word-learning strategies.

a) Using word parts

Breaking words into meaningful parts facilitates decoding. So, studying words’ parts can help students guess the meaning of new words from context.

There are three basic ways that word parts are combined in English: prefixing, suffixing, and compounding.

Teach those parts. But, focus on the most occurrent ones.

Providing explanations about their use and meanings with illustration is necessary. Yet, it is still not enough.

You need to provide opportunities for students to experiment with word-building skills.

For instance, you can hand out a list of productive prefixes and have students compile a list of words using them. Then, ask them to compare the function of the prefixes in the various examples.

However, consider your students’ level since word parts are more useful to students with larger vocabularies. For instance, a student who doesn’t know the meaning of the adjective content cannot guess the word discontent.

Remember also that learning word parts is an ongoing process. So, encourage your students to continue experimenting with them. (Zimmerman, 2009a)

b) Asking questions about word

Knowing a word means knowing about its many aspects: its meaning(s), collocations, grammatical function, derivations, and register.

So, you can encourage your students to explore a new word’s meaning(s) by asking them to address detailed questions about those features and answer them.

Students will ask questions like these :

• Are there certain words that often occur before or after the word ? (collocation)

• Are there any grammatical patterns that occur with the word ? (grammar).

• Are there any familiar roots or affixes for this word ? (word parts)

• Is the word used by both men and women? (register/appropriateness)

• Is the word used in both speaking and writing?

(register/appropriateness)

• Could it be used to refer to people? Animals?Things? (meaning)

• Does it have any positive or negative connotations? (meaning) (Zimmerman,2009a)

c) Reflecting

When students learn new words it does not necessarily mean they’ll use them. Students may avoid using words in writing because they are unsure of the spelling. When they speak, they may not be willing to use certain words as they roughly understand them in context.

Encouraging students to self-assess their knowledge of each new word they learn can help them focus on areas needing practices. Here is an example of a self-assessment scale students can use.

Besides these 6 engaging strategies for teaching vocabulary, here are some essential tips to follow while using them :

1) Identify the potential list of words to be taught. Keep the number of words to a minimum (three to five words in one lesson) to ensure there is ample time for in-depth vocabulary instruction, yet enough time for students to practise them.

2) Expose students to multiple contexts in which the new words can be used. This will support them to develop a deeper understanding of these words and how they’re used flexibly.

You can do so by giving students frequent opportunities to hear the meaning of the words, read content where these words are included, and also use them in speaking and writing.

3) Encourage extensive reading because this gives students repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts.

So, for rich vocabulary development, use a variety of strategies for teaching vocabulary and provide the necessary support and guided practice. Besides, assess vocabulary learning and encourage students to learn more words outside the classroom.

What other Strategies For Teaching Vocabulary would you suggest? I would love to hear from you.

References

Grant, K..B., Golden, S.E., & Wilson, N.S.(2015). Literacy Assessment and Instructional Strategies: Connecting to the Common Core. USA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In A.E. Farstrup 1 S.J.Samuels (Eds.), what research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp.140-165). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2008). For the love of words: Fostering word consciousness in young readers. The Reading Teacher, 62 (3), 185-193.

Hulstijn, J. & Laufer, B.(2001). Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning 51/3:539-58.

Lubliner, SH.(2005). Getting into Words: Vocabulary Instruction That Strengthens Comprehension. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing.

Schmitt, D., & Schmitt, N.(2005). Focus on Vocabulary. New York: Longman.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009a). Word Knowledge: A vocabulary teacher’s handbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009b).(ed.). Inside Reading: The Academic Word List in Context. Four Levels. New York: Oxford University Press.

It’s hard for students to read and understand a text if they don’t know what the words mean. A solid vocabulary boosts reading comprehension for students of all ages. The more words students know, the better they understand the text. That’s why effective vocabulary teaching is so important, especially for students who learn and think differently.

In this article, you’ll learn how to explicitly teach vocabulary using easy-to-understand definitions, engaging activities, and repeated exposure. This strategy includes playing vocabulary games, incorporating visual supports like graphic organizers, and giving students the chance to see and use new words in real-world contexts.

The goal of this teaching strategy isn’t just to increase your students’ vocabulary. It’s to make sure the words are meaningful and relevant to their lives.

Watch: See teaching vocabulary words in action

Watch this video of a kindergarten teacher teaching the word startled to her students:

Explore topics selected by our experts

Read: How to use this vocabulary words strategy

Objective: Students will learn the meaning of new high-value words and how to use them.

Grade levels (with standards):

- K–5 (CCSS ELA Literacy Anchor Standard L.4: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases)

- K–5 (CCSS ELA Literacy Anchor Standard R.4: Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text)

Best used for instruction with:

- Whole class

- Small groups

- Individuals

Choose the words to teach. For weekly vocabulary instruction, work with students to choose three to five new words per week. Select words that students will use or see most often, or words related to other words they know.

Before you dive in, it’s helpful to know that vocabulary words can be grouped into three tiers:

- Tier 1 words: These are the most frequently used words that appear in everyday speech. Students typically learn these words through oral language. Examples include dog, cat, happy, see, run, and go.

- Tier 2 words: These words are used in many different contexts and subjects. Examples include interpret, assume, necessary, and analyze. The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium has a partial list of Tier 2 words, broken down by grade levels.

- Tier 3 words: These are subject-specific words that are used in particular subject areas, such as peninsula in social studies and integer in math.

When choosing which vocabulary words to teach, you may want to pick words from Tier 2 because they’re the most useful across all subject areas.

Select a text. Find an appropriate text (or multiple texts for students to choose from) that includes the vocabulary words you want to teach.

Come up with student-friendly definitions. Find resources you and your students can consult to come up with a definition for each word. The definition should be easy to understand, be written in everyday language, and capture the word’s common use. Your definitions can include pictures, videos, or other multimedia options. Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary, and Wordsmyth Children’s Dictionary are all good resources to help create student-friendly definitions.

1. Introduce each new word one at a time. Say the word aloud and have students repeat the word. For visual support, display the words and their definitions for students to see, such as on a word wall, flip chart, or vocabulary graphic organizer. Showing pictures related to the word can be helpful, too.

For English language learners (ELLs): Try to use cognates (words from different languages that have a similar meaning, spelling, and pronunciation) when you introduce new words. For more information about using cognates when teaching vocabulary to ELLs, use these resources from Colorín Colorado. You can also ask students to say or draw their own definition of the words — in English or their home language — to help them understand each word and its meaning.

2. Reflect. Allow time for students to reflect on what they know or don’t know about the words. Remember that your class will come to the lesson with varying levels of vocabulary knowledge. Some students may be familiar with some of the words. Other students may not know any of them. If time permits, this could be a good opportunity to use flexible grouping so students can work on different words.

3. Read the text you’ve chosen. You can read it to your students or have students read on their own (either a printed version or by listening to an audio version). As you read, pause to point to the vocabulary words in context. Use explicit instruction to teach the word parts, such as prefixes and suffixes, to help define the word. If students are reading on their own or with a partner, encourage them to “hunt” for the words before reading. Hunting for these words first can reduce distractions later when the focus is on reading the text.

4. Ask students to repeat the word after you’ve read it in the text. Then remind students of the word’s definition. If a word has more than one meaning, focus on the definition that applies to the text.

5. Use a quick, fun activity to reinforce each new word’s meaning. After reading, use one or more of the following to help students learn the words more effectively:

- Word associations: Ask students, “What does the word delicate make you think of? What other words go with delicate?” Students can turn and talk with a partner to come up with a response. Then invite pairs to share their responses with the rest of the class.

- Use your senses: Ask your students to use their senses to describe when they saw, heard, felt, tasted, or smelled something that was delicate. Allow students time to think. Then ask them to give a thumbs up if they’ve ever seen something delicate. Call on students to share their responses. Do the same with each of the senses.

- A round of applause: If the word is an adjective, invite students to clap based on how much they would like a delicate toy, for example. Or students can “vote with their feet” by moving to one corner of the room if they want a delicate toy or another corner if they don’t. This activity works especially well if you pair the new adjective with a familiar noun.

- Picture perfect: Invite students to draw a picture that represents the word’s meaning.

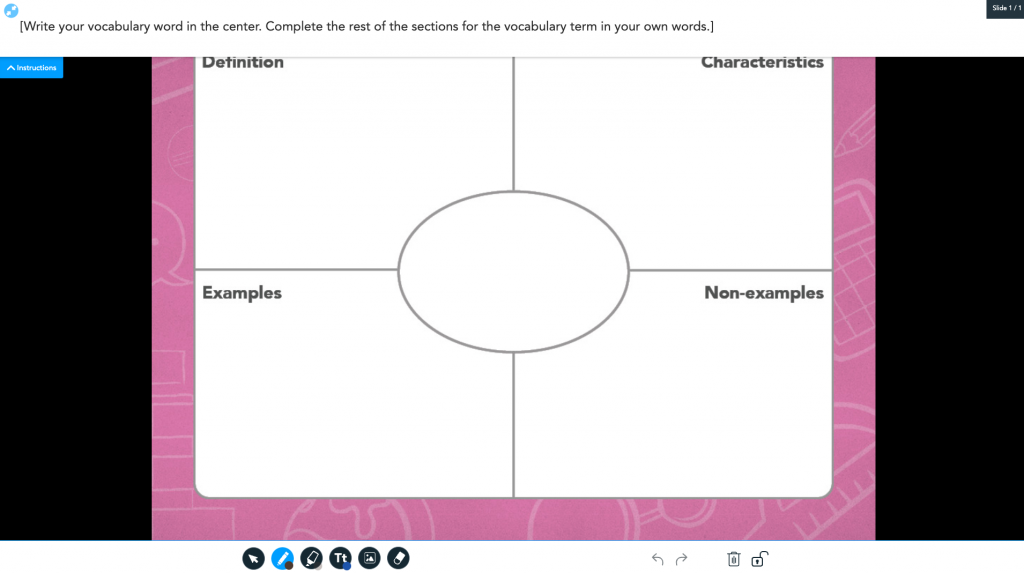

- Examples and non-examples: Give one example and one non-example of how the word is and isn’t used. For instance, you could tell students that one thing that is delicate is a teacup. One thing that isn’t delicate is the cement stairs into the school. Then invite students to share their own examples of things that are and aren’t delicate.

After students do one or more of the activities above, have them say or draw the word again.

6. Play word games. Throughout the week, play word games like vocabulary bingo, vocabulary Pictionary, and charades to practice the new words. Include words you’ve taught in the past for additional reinforcement.

7. Challenge students to use new words. They can use their new vocabulary in different contexts, like at home, at recess, or during afterschool activities. Consider asking students to use a vocabulary notebook to jot down when they use the words. You can even get your colleagues or school administrators in on the fun by asking them to use the words when talking with students or in announcements. Praise students when you hear them using those words in and out of the classroom.

Understand: Why this strategy works

Rote memorization (“skill and drill”) isn’t very helpful when it comes to learning new vocabulary. Students learn best from explicit instruction that uses easy-to-understand definitions, engaging activities, and repeated exposure. Teaching this way will help students understand how words are used in real-life contexts and that words can have different meanings depending on how they’re used.

This explicit approach helps all students and is especially helpful for students who learn and think differently. This includes students who have a hard time figuring out the meaning of new words when they’re reading. It can be difficult for them to make an inference or use context clues to figure out what a word means.

Explicit vocabulary instruction with student-friendly definitions means there’s no guesswork involved. Repeated exposure and practice help to reinforce the words in students’ memories.

Connect: Link school to home

Share with families this resource they can use at home to help students grow their vocabulary. You can model some of these strategies for families at back-to-school night or another family event.

Research behind this strategy

Explore related topics

Language is the foundation of everyday communication. Students can clearly communicate if they have a robust vocabulary, which is why teaching with effective vocabulary activities and strategies is so important. Learners can struggle to understand reading passages or math word problems if there are words they do not understand. If a text has unfamiliar words, students will likely focus on trying to understand those words rather than understanding the ideas in a text. Conversely, they may misinterpret the meaning altogether. In their writing, students must have a varied vocabulary to communicate ideas and make readers want to read their work.

Educators can increase students’ word knowledge through effective vocabulary activities. Teachers know their vocabulary instruction is effective when students apply words and their meanings in various contexts. Providing students with multiple representations of new vocabulary and opportunities for multimodal inputs and outputs will help students learn and remember vocabulary. They can also learn to discern the meaning of unfamiliar words independently.

6 Effective vocabulary activities and strategies for teaching

1. Explicitly teach vocabulary within content-rich instruction

Effective implementation of a vocabulary strategy begins with a well-planned lesson. Research suggests that direct instruction through instructional routines is more effective and efficient than allowing students to discover word meanings independently (Birsh, J. & Carreker, S., 2018). It takes repetition and frequent use for new vocabulary terms to “stick” and become a part of students’ everyday language and academic conversations.

Nearpod has ready-made core subject lessons (math, science, English and language arts, and social studies) explicitly teaching vocabulary terms. Education.com lessons also pre-teach vocabulary before content instruction.

The Nearpod English Learners Program* provides teachers with the content, tools, and organization to create daily differentiated learning experiences that maximize language acquisition for all learners. While the lessons were written for students learning English, they are also helpful in general education classrooms. In the lessons, students learn content-specific information and vocabulary simultaneously! Students also use the new vocabulary in the same lesson, helping them remember the word’s significance and meaning.

*The Nearpod EL program is available to users with a Nearpod school/district account that can access the add-on lesson program.

2. Create a vocabulary and content-rich lesson with a few clicks

Don’t see a ready-made lesson on a topic you want to teach? That’s okay. You can use Nearpod’s Slide Editor to create your own vocabulary-specific slides and embed interactive vocabulary activities and assessments for students.

Here’s an example of a vocabulary instructional process you can follow in your teacher-created slides:

- Prepare your Nearpod lesson by adding a video with the word pronunciation as Reference Media in a Collaborate Board. You can embed a video from YouTube or upload your own video. You can also enable Immersive Reader for students to have them see the definition and other properties of the vocabulary word.

- Start your instruction by saying the new word aloud and having students repeat it. Have students type or record their answers on the Collaborate Board.

- Provide a student-friendly definition of the word. Insert images and example sentences into the slide. (Read more about student-friendly definitions in vocabulary activity #3!)

- During instruction, connect the word to other vocabulary terms students already know. Add a Matching Pairs activity to have students connect words to definitions.

- Ask students to use the word aloud and in their writing. Allow them to submit their responses on an Open-Ended Question or Collaborate Board.

3. Provide student-friendly definitions

The vocabulary strategy of using student-friendly definitions is essential for learners to understand new word meanings. Dictionary definitions can be hard for students to understand, and they do not always fully capture the word’s meaning. Additionally, there is often more than one definition. When improving vocabulary, multiple definitions can make it difficult for students to know which is correct given the context of the lesson or reading passage (Beck et al, 2013).

To write student-friendly definitions, use everyday language in the context of a relatable example. For example, take the word “commend.” Here’s how you can share student-friendly definitions:

If I “commend” a student, I give them compliments or praise because they probably did something that impressed me. The “praise” I give would be in public. An example sentence is, “I commended Eli for his efforts during the spelling bee.” The word “commend” implies that I praised Eli publicly for his work at the spelling bee. Can you think of something someone did that you would commend them for?

In this example:

- I introduced the word’s definition.

- I provided context and an example sentence.

- I asked students to use the word immediately after learning its meaning.

If the class is reading a book with the word “commend,” using a book excerpt to connect the student-friendly definition is another avenue you can pursue.

4. Use interactive videos in your vocabulary instruction

Along with providing a student-friendly definition, have students interact with the word in various ways. Students can better remember and understand new meanings by bringing in other modalities (Birsh, J. & Carreker, S., 2018). You can use videos and music to provide auditory and visual communication. Videos and songs can model how students can use newly learned language!

Nearpod Original (NPO) videos are helpful when teaching students about specific topics. Adding an NPO video to a lesson can add a multimodal dimension. Videos often show real-world representations and offer further examples of the word in context. To check students’ comprehension, you can add questions in the video. The video will pause at specific points and prompt a question to check students’ understanding and keep them engaged in the video lesson.

The Personification Nearpod Original perfectly explains the meaning of personification and provides context for the word, as seen in the two poems. Consider using Nearpod Original videos when vocabulary activities to teach your students.

If you want to use a video from YouTube, you can create your own Interactive Video by adding the video and your questions to the lesson. YouTube videos embed into Nearpod so students can watch a video about the water cycle or any other topic without navigating away from Nearpod or viewing pop-up ads.

5. Strategically choose which vocabulary words to teach in the classroom

There is only so much time in the day for instruction and student practice. When teachers decide to teach vocabulary explicitly, the terms should give students the biggest bang for their buck. Teachers can efficiently use instructional time by introducing academic vocabulary students frequently encounter in multiple subject areas (Beck et al, 2013; Birsh, J. & Carreker, S., 2018).

Teaching tier two words is one way to introduce new vocabulary strategically. Tier two words appear in multiple subjects and can sometimes have multiple meanings. This distinction is helpful for students to improve their vocabulary.

How to teach Tier 1, 2, and 3 vocabulary words

Understanding the tiers can help you choose which words to teach in your vocabulary activities. Students encounter tier-one words in everyday language. They will likely learn words such as “like,” “swim,” and “run” through hearing and participating in conversations. Tier two words appear in multiple domains and written text, making them high-utility words. Since students would not typically encounter them in conversation, they would benefit from explicit instruction of words like “contradict” or “maintain.” The most infrequent terms are tier-three words. These words are subject-specific words learners would infrequently use, such as “economy” or “counterclaim.” Keep in mind that even though general guidelines differentiate the different tiers, there is some overlap between the types of terms.

Nearpod EL’s academic vocabulary lesson series contains many tier-two words. The word “Energy” is an example of a tier two word.

Ask yourself these questions when selecting words for vocabulary activities:

- Can students comprehend the process, reading passage, or concept even if they do not know this word? If they cannot meet any of those criteria, teach the word!

- Will learners encounter this word in other subjects or later grade levels? If they meet one of those criteria, teach the word!

- Can learners make connections between the new words and words they already know? The term may be worthy of a direct instruction moment if the answer is yes.

After instruction, practice newly-acquired words in a competitive, fun way with a Time to Climb! The gamified activity allows for photos or text as the answer option.

6. Get students involved in choosing the vocabulary words they want to learn

Let students select fascinating words for a book the class reads aloud or from their independent reading time. If there is no time to teach student-chosen words, encourage them to learn the new words. Then they can teach the class the word through a vocabulary presentation!

For their vocabulary presentation, students can use a Draw It interactive activity in Nearpod to draw a picture or create a diagram. As they present the new word, they can reference the drawing.

The presentation will help the presenter remember the word, and the audience may learn a new word too! Using a simple Frayer Model Draw It template to share the word is one vocabulary-sharing visual presenters can use. Frayer Models bring in the multimodal aspect of communicating through drawing and writing.

Use these vocabulary activities in your classroom

This list of vocabulary strategies is by no means comprehensive. There are many more effective strategies available to improve vocabulary retention. Choose the method that will meet your students’ needs and time constraints. This list can inspire some ideas and show you how easy it is to implement vocabulary activities with Nearpod.

With Nearpod, you can create interactive lessons and activities in one place. You can also use our premade standards-aligned resources across all subjects and grade levels. Sign up for free now to use these tips and explore the power of Nearpod!

Interested in reading more about this topic? Check out this blog post: 6 tips for teaching reading and writing skills in any classroom

References and Further Reading

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., Kucan, L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013a). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed). The Guilford Press.

Birsh, J. R., & Carreker, S. (Eds.). (2018). Multisensory teaching of basic language skills (Fourth Edition). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read. (n.d.). ww.Nichd.Nih.Gov/. Retrieved September 22, 2022, from www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/nrp/smallbook

Wexler, N. (2019). The knowledge gap: The hidden cause of America’s broken education system–and how to fix it. Avery, an imprint of Penguin Randon House, LLC.

Jennifer is a forever educator with over 10 years of experience in education. Her mission is to create research-informed educational experiences that engage students and inspire learning.

The Importance of Vocabulary Development

According to Steven Stahl (2005), “Vocabulary knowledge is knowledge; the knowledge of a word not only implies a definition, but also implies how that word fits into the world.” We continue to develop vocabulary throughout our lives. Words are powerful. Words open up possibilities, and of course, that’s what we want for all of our students.

Key Concepts

Differences in Early Vocabulary Development

We know that young children acquire vocabulary indirectly, first by listening when others speak or read to them, and then by using words to talk to others. As children begin to read and write, they acquire more words through understanding what they are reading and then incorporate those words into their speaking and writing.

Vocabulary knowledge varies greatly among learners. The word knowledge gap between groups of children begins before they enter school. Why do some students have a richer, fuller vocabulary than some of their classmates?

- Language rich home with lots of verbal stimulation

- Wide background experiences

- Read to at home and at school

- Read a lot independently

- Early development of word consciousness

Why do some students have a limited, inadequate vocabulary compared to most of their classmates?

- Speaking/vocabulary not encouraged at home

- Limited experiences outside of home

- Limited exposure to books

- Reluctant reader

- Second language—English language learners

Children who have been encouraged by their parents to ask questions and to learn about things and ideas come to school with oral vocabularies many times larger than children from disadvantaged homes. Without intervention this gap grows ever larger as students proceed through school (Hart and Risley, 1995).

How Vocabulary Affects Reading Development

From the research, we know that vocabulary supports reading development and increases comprehension. Students with low vocabulary scores tend to have low comprehension and students with satisfactory or high vocabulary scores tend to have satisfactory or high comprehension scores.

The report of the National Reading Panel states that the complex process of comprehension is critical to the development of children’s reading skills and cannot be understood without a clear understanding of the role that vocabulary development and instruction play in understanding what is read (NRP, 2000).

Chall’s classic 1990 study showed that students with low vocabulary development were able to maintain their overall reading test scores at expected levels through grade four, but their mean scores for word recognition and word meaning began to slip as words became more abstract, technical, and literary. Declines in word recognition and word meaning continued, and by grade seven, word meaning scores had fallen to almost three years below grade level, and mean reading comprehension was almost a year below. Jeanne Chall coined the term “the fourth-grade slump” to describe this pattern in developing readers (Chall, Jacobs, and Baldwin, 1990).

Incidental and Intentional Vocabulary Learning

How do we close the gap for students who have limited or inadequate vocabularies? The National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that there is no single research-based method for developing vocabulary and closing the gap. From its analysis, the panel recommended using a variety of indirect (incidental) and direct (intentional) methods of vocabulary instruction.

Incidental Vocabulary Learning

Most students acquire vocabulary incidentally through indirect exposure to words at home and at school—by listening and talking, by listening to books read aloud to them, and by reading widely on their own.

The amount of reading is important to long-term vocabulary development (Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998). Extensive reading provides students with repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts (Kamil and Hiebert, 2005).

Intentional Vocabulary Learning

Students need to be explicitly taught methods for intentional vocabulary learning. According to Michael Graves (2000), effective intentional vocabulary instruction includes:

- Teaching specific words (rich, robust instruction) to support understanding of texts containing those words.

- Teaching word-learning strategies that students can use independently.

- Promoting the development of word consciousness and using word play activities to motivate and engage students in learning new words.

Research-Supported Vocabulary-Learning Strategies

Students need a wide range of independent word-learning strategies. Vocabulary instruction should aim to engage students in actively thinking about word meanings, the relationships among words, and how we can use words in different situations. This type of rich, deep instruction is most likely to influence comprehension (Graves, 2006; McKeown and Beck, 2004).

Student-Friendly Definitions

The meaning of a new word should be explained to students rather than just providing a dictionary definition for the word—which may be difficult for students to understand. According to Isabel Beck, two basic principles should be followed in developing student-friendly explanations or definitions (Beck et al., 2013):

- Characterize the word and how it is typically used.

- Explain the meaning using everyday language—language that is accessible and meaningful to the student.

Sometimes a word’s natural context (in text or literature) is not informative or helpful for deriving word meanings (Beck et al., 2013). It is useful to intentionally create and develop instructional contexts that provide strong clues to a word’s meaning. These are usually created by teachers, but they can sometimes be found in commercial reading programs.

Defining Words Within Context

Research shows that when words and easy-to-understand explanations are introduced in context, knowledge of those words increases (Biemiller and Boote, 2006) and word meanings are better learned (Stahl and Fairbanks, 1986). When an unfamiliar word is likely to affect comprehension, the most effective time to introduce the word’s meaning may be at the moment the word is met in the text.

Using Context Clues

Research by Nagy and Scott (2000) showed that students use contextual analysis to infer the meaning of a word by looking closely at surrounding text. Since students encounter such an enormous number of words as they read, some researchers believe that even a small improvement in the ability to use context clues has the potential to produce substantial, long-term vocabulary growth (Nagy, Herman, and Anderson, 1985; Nagy, Anderson, and Herman, 1987; Swanborn and de Glopper, 1999).

Sketching the Words

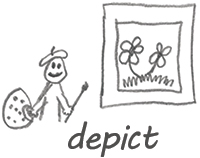

Sketching the Words

For many students, it is easier to remember a word’s meaning by making a quick sketch that connects the word to something personally meaningful to the student. The student applies each target word to a new, familiar context. The student does not have to spend a lot of time making a great drawing. The important thing is that the sketch makes sense and helps the student connect with the meaning of the word.

Applying the Target Words

Applying the target words provides another context for learning word meanings. When students are challenged to apply the target words to their own experiences, they have another opportunity to understand the meaning of each word at a personal level. This allows for deep processing of the meaning of each word.

Analyzing Word Parts

Analyzing Word Parts

The ability to analyze word parts also helps when students are faced with unknown vocabulary. If students know the meanings of root words and affixes, they are more likely to understand a word containing these word parts. Explicit instruction in word parts includes teaching meanings of word parts and disassembling and reassembling words to derive meaning (Baumann et al., 2002; Baumann, Edwards, Boland, Olejnik, and Kame’enui, 2003; Graves, 2004).

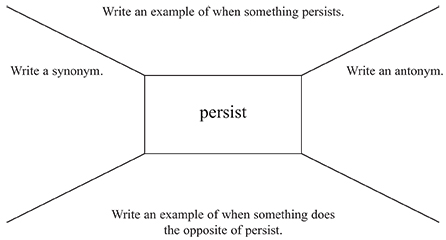

Semantic Mapping

Semantic Mapping

Semantic maps help students develop connections among words and increase learning of vocabulary words (Baumann et al., 2003; Heimlich and Pittleman, 1986). For example, by writing an example, a non-example, a synonym, and an antonym, students must deeply process the word persist.

Word Consciousness

Word consciousness is an interest in and awareness of words (Anderson and Nagy, 1992; Graves and Watts-Taffe, 2002). Students who are word conscious are aware of the words around them—those they read and hear and those they write and speak (Graves and Watts-Taffe, 2002). Word-conscious students use words skillfully. They are aware of the subtleties of word meaning. They are curious about language, and they enjoy playing with words and investigating the origins and histories of words.

Teachers need to take word-consciousness into account throughout their instructional day—not just during vocabulary lessons (Scott and Nagy, 2004). It is important to build a classroom “rich in words” (Beck et al., 2002). Students should have access to resources such as dictionaries, thesauruses, word walls, crossword puzzles, Scrabble® and other word games, literature, poetry books, joke books, and word-play activities.

Teachers can promote the development of word consciousness in many ways:

- Language categories: Students learn to make finer distinctions in their word choices if they understand the relationships among words, such as synonyms, antonyms, and homographs.

- Figurative language: The ability to deal with figures of speech is also a part of word-consciousness (Scott and Nagy 2004). The most common figures of speech are similes, metaphors, and idioms.

Once language categories and figurative language have been taught, students should be encouraged to watch for examples of these in all content areas.

Teaching Words and Vocabulary-Learning Strategies With Read Naturally Programs

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

These intentional vocabulary learning strategies can be efficiently and effectively implemented using Read Naturally’s program Take Aim! at Vocabulary. Take Aim is appropriate for students who can read at least at a fourth grade level. Take Aim is available in two formats:

- The semi-independent format provides differentiated instruction for students working mostly independently.

- The small-group format is designed for small-group instruction—up to six students.

Each Take Aim level teaches 288 carefully selected target words in the context of engaging, non-fiction stories. The target words are systematically taught using the research-based strategies described above. The intensive and focused lesson design helps students learn the target words and internalize the skills and strategies necessary for independently learning unknown words.

Learn more about how Take Aim teaches vocabulary and word-learning strategies:

- Take Aim at Vocabulary product page

- Take Aim samples

- Research basis for Take Aim at Vocabulary

Splat-O-Nym: Vocabulary Word Game for iPad

Learn more about the Splat-O-Nym app:

- Splat-O-Nym product page

- Research basis for Splat-O-Nym

Other Programs That Support Vocabulary Development

These other Read Naturally programs do not focus on vocabulary but include activities that support vocabulary development:

Bibliography

Anderson, R. C., & Nagy, W. E. (1992). “The vocabulary conundrum,” American Educator, Vol. 16, pp. 14-18, 44-47.

Baumann, J. F., Edwards, E. C., Boland, E., Olejnik, S., & Kame’enui, E. (2003). “Vocabulary tricks: effects of instruction in morphology and context on fifth grade students’ ability to derive and infer word meanings,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 447–494.

Baumann, J. F., Edwards, E. C., Font, G., Tereshinski, C. A., Kame’enui, E. J., & Olejnik, S. (2002). “Teaching morphemic and contextual analysis to fifth-grade students.” Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 37, pp. 150–176.

Baumann, J. F., Kame’enui, E. J., & Ash, G. E. (2003). “Research on vocabulary instruction: Voltaire redux,” in J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, and J. M. Jensen (eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts, 2nd ed., Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 752–785.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life. Robust vocabulary instruction, New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life. Robust vocabulary instruction, 2nd ed., New York: Guilford Press.

Biemiller, A. & Boote, C. (2006). “An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in the primary grades,” Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 44–62.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The reading crisis: Why poor children fall behind, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cunningham, A. E. & Stanovich, K. E. (1998). “What reading does for the mind,” American Educator, Vol. 22, pp. 8–15.

Graves, M. F. (2000). “A vocabulary program to complement and bolster a middle-grade comprehension program,” in B. M. Taylor, M. F. Graves, and P. Van Den Broek (eds.), Reading for meaning: Fostering comprehension in the middle grades, New York: Teachers College Press.

Graves, M. F. (2004). “Teaching prefixes: As good as it gets?,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 81–99.

Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book, New York: Teachers College Press, International Reading Association, National Council of Teachers of English.

Graves, M. F. & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2002). “The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program,” in A. E. Farstrup and S. J. Samuels (eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction, Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Hart, B. & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children, Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Heimlich, J. E. & Pittleman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications, Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kamil, M. L. & Hiebert, E. H. (2005). “Teaching and learning vocabulary: Perspectives and persistent issues,” in E. H. Hiebert and M. L. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McKeown, M. G. & Beck, I. L. (2004). “Direct and rich vocabulary instruction,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 13–27.

Nagy, W. E., Anderson, R. C., & Herman, P. A. (1987). “Learning word meanings from context during normal reading,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 237-270.

Nagy, W. E., Herman, P. A. & Anderson, R. C. (1985). “Learning words from context,” Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 233–253.

Nagy, W. E. & Scott, J. A. (2000). “Vocabulary processes,” in M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, Vol. 3, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769), Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 13–14.

Scott, J. & Nagy, W. (2004). “Developing word consciousness,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 201–215.

Stahl, S. A. (2005). “Four problems with teaching word meanings (and what to do to make vocabulary an integral part of instruction),” in E. H. Hiebert and M. L. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stahl, S. A. & Fairbanks, M. M. (1986). “The effects of vocabulary instruction: A model-based meta analysis,” Review of Educational Research, Vol. 56, pp. 72–110.

Swanborn, M. S. & de Glopper, K. (1999). “Incidental word learning while reading: A meta-analysis,” Review of Educational Research, Vol. 69, pp. 261-285.

The theory and techniques for teaching vocabulary may not be as fun as the ideas that I’ll share in the next post or as perusing the books in the last post, yet this is the theory applicable to all ages and types of readers. It is the knowledge that will enable you to choose the right activities and strategies for your content and grade level.

PURPOSES FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

In my experience, we teach vocabulary for a variety of reasons. It’s important to think about the vocabulary instruction in your teaching practice by considering why you are doing it. That will help you determine which theories and techniques you should use (or at least try).

Reasons include:

- Improving reading comprehension in general.

- Improving subject-specific mastery and performance.

- Improving writing and speaking skills.

- Test preparation (SAT, ACT, etc.).

- Deepening students’ ability to put their thoughts into the most appropriate word possible.

These techniques and theories are in no particular order.

This post is Part 2 of a four-part series on teaching vocabulary. If you would like to check out the rest of the series, visit the posts below

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary

- Ideas for English Language Learners

EXPOSURE RATES MATTER

Students need to be exposed to the vocabulary over and over if they are to understand and use the words effortlessly. When stories or texts are repeated, students gain more word knowledge.

Research shows that students hearing stories more than once have a 12% gain over their peers who only heard the story one time when tested on the vocabulary in context.

Want to read the research? Look for the studies done by Biemiller and Boote (2006) and Coyne, Simmons, Kame`enui, and Stoolmiller (2004).

DEFINE THE WORDS WHILE YOU READ

It works better to share vocabulary in context, rather than just learning definitions. Giving students lists of words and having them look up the definitions is useless and ineffective. You’re shocked, aren’t you?

It’s also important to emphasize and practice pronunciation of new/unfamiliar words. Don’t assume that regular decoding skills will work with academic vocabulary. Practice saying the words.

Want to read the research? Look for the study done by Nash and Snowling (2006).

TIERED WORDS: VOCABULARY IN THE CORE

To decide whether or not a word from a story or lesson should be directly taught, consider:

- Is it unfamiliar but able to be understood?

- Is it necessary for comprehension?

- Does it appear in other contexts?

- Is it likely to show up again?

One particular model divides words into three categories, or tiers. This model was developed by Isabelle Beck in Bringing Words to Life.

- Tier One words are the words of everyday speech usually learned in the early grades. These are not necessary to teach explicitly (except for in ELL acquisition).

- Tier Two words are what the Common Core standards refer to as academic words. They are more to be read by students in texts that heard in conversations. They may be in informational or technical texts, or in literary works with sophisticated vocabulary. They often make language more precise (saying “wended their way” instead of “walked along,” for example). They are words that cross domains, so you may see them in a variety of disciplines.

- Tier Three words are the domain-specific words that you would only see in relation to a specific content area. They are the ones you see bolded in textbooks and/or listed in the glossary.

You can watch a video about this at Engage NY.

(Note: The words that she mentions in the beginning of the video that you would see only in certain areas are Tier Three words.)

ASK QUESTIONS

Students learn the vocabulary best when teachers actually integrate questioning and discussion into lessons, rather than just defining them.

Here are some example questions:

- What other words do you know that are similar to this word?

- How can we use this word in [insert other thing you’ve studied]?

- Do you recognize any of the parts of this word?

- If I said that [insert another word here] is the same or similar as this word, would that be true?

Want to read the research? Look for the study by Ard and Beverly (2004).

THE FOUR COMPONENTS

Michael Graves argues that there are four components of an effective vocabulary program:

- Teach individual words: Teach new words explicitly, meaning on purpose. Make sure students understand the definition. Make sure the definitions are in student-friendly vocabulary. It doesn’t help you to understand a word if you don’t know the words in the definition, either. Show the word in a variety of contexts. Have students generate their own definitions. Have them engage with the words interactively, playing with them. Vary the methods so you’re not teaching the same way for every word.

- Provide rich and varied language experiences: We need reading, listening, speaking, and writing experiences across multiple genres. Yes, there is math poetry. Read out loud to students. Encourage book clubs and reading challenges. The idea: create an environment saturated with words.

- Teach word-learning strategies: Teach students how to infer word meaning from context clues. Teach students how to infer meaning from morpheme clues. Teach students how and when to use a dictionary and a thesaurus. We can’t assume that students know the strategies they need to make sense of words.

- Foster word consciousness: Point out useful, beautiful, powerful, or painful lessons. Be playful with words.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

When testing students’ command of vocabulary, use a self-assessment that is non-judgmental, using prompts such as:

- I have never seen or heard the word before.

- I’ve seen or heard the word, but I don’t know what the word means.

- I vaguely know the meaning.

- I can associate the word with a concept or context.

- I know the word well.

- I can explain and use it in general or in writing.

- I can explain and use it with a full and precise meaning.

EASE METHOD

- Enunciate new words syllable-by-syllable and then blend the word.

- Associate the word with definitions and examples that students already know.

- Synthesize the words with other words and concepts that they have already studied and they have the opportunity to demonstrate deep knowledge of the new word.

- Emphasize new words in classroom discussion.

SIX STEP MODEL OF VOCABULARY INTRODUCTION

- Step one: The teacher explains a new word, going beyond reciting its definition (tap into prior knowledge of students, use imagery).

- Step two: Students restate or explain the new word in their own words (verbally and/or in writing).

- Step three: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the word (a picture, or symbolic representation).

- Step four: Students engage in activities to deepen their knowledge of the new word (compare words, classify terms, write their own analogies and metaphors).

- Step five: Students discuss the new word (pair-share, elbow partners).

- Step six: Students periodically play games to review new vocabulary (Pyramid, Jeopardy, Telephone).

DICTIONARIES

Use dictionaries to work with words that already somewhat familiar. It is not helpful to have students try to look up words they can’t spell.

WHAT DOESN’T WORK

Kate Kinsella’s ideas of what doesn’t work include:

- Incidental teaching of words

2. Asking, “Does anybody know what _____ means?”

3. Copying same word several times

4. Having students “look it up” in a typical dictionary

5. Copying from dictionary or glossary

6. Having students use the word in a sentence after #3,4, or 5

7. Activities that do not require deep processing (word searches, fill-in-the-blank)

8. Rote memorization without context

9. Telling students to “use context clues” as a first or only strategy or asking students

to guess the meaning of the word

10. Passive reading as a primary strategy (SSR)

Watch a video of her teaching about vocab instruction and find related activities here.

IDEAS FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

This article has focused on the theory of teaching vocabulary. Be sure to check out the third article in the series for loads of activities for teaching vocabulary in your classroom.

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary (the one with loads of activities!!!)

- Ideas for English Language Learners

THE ULTIMATE METHOD FOR TEACHING ACADEMIC VOCABULARY

I think academic vocabulary is so important that I’ve spent decades perfecting a method of teaching it that works like a dream! It’s called the Concept Capsule method, and I’ve written an entire book about it.

Find out more here (and get a 50% discount for reading this article!).

Note: This content uses affiliate links, which means that if you order one of the things I recommend, I may geta a small commission.

Sketching the Words

Sketching the Words Analyzing Word Parts

Analyzing Word Parts Semantic Mapping

Semantic Mapping Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades