На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

как слишком много

слишком нравятся

любят слишком много

слишком нравится

кажется слишком большой

нравится слишком много

кажется слишком много

кажется чересчур

слишком похоже

показаться слишком большим

очень понравилось, так

казалось слишком

нравятся чрезмерные

Предложения

And if that sounds like too much work, then ask yourself the following question…

И если это звучит как слишком много работы, то задайте себе следующий вопрос…

The problem is that patients with diabetes do not like too much changes in the diet that need to be implemented.

Проблема в том, что больным диабетом не слишком нравятся изменения в рационе, которые нужно осуществить.

Even if some human qualities of Tina do not like too much, she just tries not to focus attention on it.

Если даже некоторые человеческие качества Тине не слишком нравятся, она просто старается не акцентировать на этом внимание.

These games are again very popular for people who do not like too much action or violence.

They don’t like too much structure.

It felt like too much driving today.

Maybe it really feels like too much information.

Может быть, это действительно даст вам ощущение избытка информации.

Nothing corrupts like too much power.

Ничто не будоражит так сильно, как власть.

Q: This seems like too much trouble.

If that sounds like too much of a hassle, then you’re not ready to responsibly manage your condition.

Если вам это кажется чересчур хлопотным делом, то вы не готовы ответственно управлять своим состоянием.

He doesn’t like too much noise or people around him.

Looks like too much worry can lead to the opposite problem, though.

It feels like too much power in the hands of one company.

Это чересчур, слишком много власти сосредоточено в руках одной компании.

This month should be avoided if you do not like too much rain.

If I go to the local food market, I don’t like too much attention.

They get embarrassed and feel ashamed, and coming back seems like too much of an ordeal.

И стыдно делается, и неловко, а возвращаться кажется глупо.

He floods the house with a variety of animals, which his family doesn’t like too much.

Он наводняет дом разнообразными животными, что не слишком нравится его семье.

Sometimes, it can even feel like too much.

Fine, I’ll watch a movie, but nothing we’ll like too much.

But it seemed like too much responsibility.

Предложения, которые содержат like too much

Результатов: 215. Точных совпадений: 215. Затраченное время: 429 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Иногда кажется, что все это- слишком, верно?

You had mentioned getting her a ten-speed, and I just think both feels like too much.

Ты говорил, что хочешь купить ей велосипед, а я подумала что эти обе вещи через чур.

I wasn’t, sure whether I ought to, it felt like too much— and on question twenty-three-»Hermione,’ said Ron sternly,’we have been through this before….

Я не была уверена, нужно ли это, наверное, это было все же лишним, а на вопросе двадцать- три….

I know that some of the normal wifely duties are off the table,

but showing up on time for a parade doesn’t seem like too much to ask.

Знаю, что лишен некоторых супружеских обязанностей,

но появиться вовремя на парад не так уж сложно.

We’re already getting another“Road To…” episode this season, so a romp through a toy

factory taking over an episode probably seemed like too much for one year.

У нас уже был эпизод из серии„ Road to…“ в этом

сезоне, поэтому данное приключение на фабрике, вероятно, лишне для одного года.».

But a pair of friends of mine(older ones)

Но пара моих друзей, более старших,

построили несколько советских моделей, которые мне очень понравились.

I just feel

like

that whole,

like,

dating thing was a little bit,

like,

too much.

Просто вся эта штука со свиданиями была чем-то лишним.

Dog Man doesn’t

like

too much stinky stuff.

To players, it may not seem

like

too much for each to roll a separate initiative die, but consider the difficulties:

У игроков, это не может занимать слишком много времени, чтобы бросить отдельный кубик, но рассматривайте трудности:

If that sounds

like

too much stress to you,

then why not save yourself the hassle and let our tax experts here at taxback. com speed through all the paperwork to file your return quickly and easily.

то почему бы не избавить себя от хлопот и пусть наши налоговые специалисты здесь, на taxback. com, сделают это быстро и легко для Вас.

Results: 16918,

Time: 0.0206

English

—

Russian

Russian

—

English

In 2016, I was offered a promo code to test out a new app designed to help young people talk without filler phrases like you know and like, so they could sound more “authoritative.” I tried not to take the offer personally. For decades, like has been a subject of deep linguistic ridicule — along with vocal fry and uptalk, it is probably the most recognizable aspect of “Valley girl speak.” When making fun of teenage girls, imitators go for these sorts of phrases: “I, like, went to the movies? And I was like, ‘I want to see Superwoman?’ But Brad was like, ‘No way?’ So we, like, left.” (I’m not certain why people love satirizing teen girls so much, but my theory is that it’s just an excuse to speak in this highly entertaining fashion.)

Fortunately, there are plenty of language experts who’ve taken “Valley girl” speak seriously enough to figure out what it actually is. One of these scholars is Carmen Fought, a linguist from Pitzer College, who says, “If women do something like uptalk or vocal fry, it’s immediately interpreted as insecure, emotional or even stupid.” But the truth is much more interesting: Young women use the linguistic features that they do, not as mindless affectations, but as power tools for establishing and strengthening relationships. Vocal fry, uptalk and even like, are in fact not signs of ditziness, but instead all have a unique history and special social utility. And women are not the only people who use them.

Despite the word’s detractors, like is in fact extremely useful and versatile. Alexandra D’Arcy, Canadian linguist at the University of Victoria, has dedicated much of her research to identifying and understanding the many functions of like. D’Arcy ebulliently describes her work for the university’s YouTube channel: “Like is a little word that we really, really don’t like at all — and we want to blame young girls, who we think are destroying the language,” she explains. But the truth is that like has been a part of English for more than 200 years. “We can find speakers today in their 70s, 80s and 90s around little villages in the United Kingdom, for example,” D’Arcy says with a smile, “who use like in many of the same ways that young girls today are using it.”

According to D’Arcy, there are six completely distinct forms of the word like. The two oldest types in English are the adjective like and the verb like. In the sentence, “I like your suit, it makes you look like James Bond,” the first like is a verb and the second is an adjective — and even the crabbiest English speakers are fine with both. Today, these two likes sound exactly the same, so most people don’t even notice that they’re different words with separate histories. They’re homonyms, just how the noun watch (meaning the timepiece on your wrist) and the verb watch (meaning what you do with your eyes when you turn on the TV) are homonyms. The Oxford English Dictionary says that the verb like comes from the Old English term lician, and the adjective comes from the Old English līch. The two converged at some point over the last 800 or so years, giving us lots of time to get used to them.

But four new likes developed much more recently than that — and D’Arcy says these are all separate words with distinct uses, as well. Only two of these likes are used more frequently by women, and only one of them is thought to have been masterminded by young Southern California females in the 1990s. That one would be the quotative like, which you hear in, “I was like, ‘I want to see Superwoman.’” As lampooned as it is, pragmatically speaking, this like is one of my favorites because it allows you to tell a story, to relay something that happened, without having to quote the interaction verbatim. For example, in the sentence “My boss was like, ‘I need those papers by Monday,’ and I was like, ‘Are you f—ing kidding me?’” you’re not repeating what you truly said but instead using like to convey what you wanted to say or how you felt in the interaction. Thanks, Valley girls. This very useful quotative like continues to explode in common usage.

The other like that women tend to use more frequently is categorized as a discourse marker and can be found in contexts such as, “Like, this suit isn’t even new.” A discourse marker — sometimes called a filler word — is a type of phrase that can help a person connect, organize or express a certain attitude with their speech. Other discourse markers include the hedges just, you know and actually.

There are two last forms of like: one is an adverb, which is used to approximate something, as in the sentence, “I bought this suit like five years ago.” As of the 1970s this like has largely replaced the approximate adverb about in casual conversation, and it has always been used equally among men and women (so it isn’t hated as much). And last, there’s the discourse particle like, which we hear in, “I think this suit is like my favorite possession.” This like is similar to the discourse marker, except that it’s not used in quite the same way syntactically or semantically; plus, dudes use it just as much as women do (D’Arcy doesn’t know quite why that is), though they’re almost never ridiculed for it.

Objectively, we can see that using one, two or all of these different likes in the same sentence isn’t inherently bad. As a matter of fact, some studies have demonstrated that speech lacking in likes and you knows can sound too careful, robotic or unfriendly. So next time someone accuses you of saying like too much, feel free to ask them, “Oh really? Which kind?” Because D’Arcy says that ordinary speakers tend to buy into the Valley girl stereotype so hardcore, blaming young women for all of these likes, simply because they don’t notice the differences among them.

From the book WORDSLUT. Copyright © 2019 by Amanda Montell. Published on May 28, 2019 by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Contact us at letters@time.com.

I’m listening to BBC Radio 1, where they are interviewing the 26-year-old actor and singer Dove Cameron about her globally successful hit, Boyfriend. The DJ, Melvin Odoom, asks her, “Do you think that your acting career has helped you with, kind of, like, your music career?”

“For me they’re, like, the same energy,” replies Cameron. “Which is, like, when people are, like, ‘You have to choose,’ I’m like, ‘They feel the same!’”

It’s the most predictable celebrity interview exchange ever uttered, remarkable only for one word that repeats and repeats.

“It’s a really funny one,” says Fiona Hanlon, who has worked at the station for more than 10 years, including producing Nick Grimshaw’s breakfast show and Maya Jama’s weekend show. “If a guest says ‘like’ too much, we’d get texts from the listeners. If a DJ says it too much, sometimes a boss might pop in and mention it … It’s just seen as a bit lazy, a bit dumb. I was always very aware of it.”

Why do people have such a problem with “like”? Is it because it simply won’t go away? In 1992, Malcolm Gladwell wrote a robust defence of the word and the way it carries “a rich emotional nuance”, responding to what had already been a decade of criticism. This did nothing to settle the debate. Linguists agree that usage of the word has increased every year since then, to the point where in one five-minute exchange on Love Island in 2017, the word was uttered 76 times, once every four seconds.

By the time I was at secondary school in the early 2000s, “like” was just a natural part of speech. Transcribing the interviews I did for this piece, I say it constantly. When I do, I find it a friendly crutch, signalling to the person I’m talking to that we’re having a spontaneous and unrehearsed conversation, that I’m listening and thinking. But despite its long history and widespread use, for many it remains enraging.

Politicians, educators and business leaders have complained it makes speakers sound stupid. When Michael Gove was education secretary in 2014, he used an update to the national curriculum to require students to speak in “standard English”, even in informal settings, in all British schools. This reinforced the idea that there was only one right way to speak English. By 2019, one primary school head in Bradford, Christabel Shepherd, said she banned the word because, “When children are giving you an answer and they say, ‘Is it, like, when you’re, like…’ they haven’t actually made a sentence at all. They use the word all the time and we are trying to get rid of it.” Nick Gibb, then schools minister, praised the decision and said others should follow suit.

Scores of recruitment specialists and public-speaking coaches have publicly bemoaned the word’s rise and say those who use it prevent themselves from getting opportunities. One law firm in America sent a memo to just its female employees and told them: “Learn hard words,” and “Stop saying ‘like’.” Peter Mertens, an associate at PR firm Burson Cohn & Wolfe, has said: “There is nothing that will [lead you to being] dismissed more quickly than a few too many ‘likes’ during a meeting or on a call.” There’s even an app, LikeSo, recommended by businesses, which listens to your speech and promises it can stop you using the word.

In the UK, this chorus is made louder by a group of mostly old and white celebrities and Spectator columnists who crusade against its use. In 2010, Emma Thompson complained to the Radio Times that she “went to give a talk at my old school and the girls were all doing their ‘likes’ and ‘innits?’ which drives me insane… I told them ‘Just don’t do it. Because it makes you sound stupid.’” Gyles Brandreth, writing in the Oldie (where else?), complained that “like” was “the lazy linguistic filler of our times” and “very very irritating”.

Why is it so detested? “Well, humans have an innate tendency to judge. People who are very liberal in other aspects of things, who would never judge someone based on race or sexual orientation or whatever, still have this thing about language,” says Carmen Fought, professor of linguistics at Pitzer College. “They want to freeze it and they want to judge it. I absolutely guarantee you that in Shakespeare’s time, there was some schoolmaster walking around saying, ‘Don’t say “soothe” Portia, that sounds so tacky, say “For soothe.”’”

There’s certainly an element of sexism here and the detractors of “like” say it makes you sound girlish and stupid, arguing that this is a newish tic said mostly by women and that it’s a meaningless “filler” word that doesn’t add anything to a sentence’s meaning. But they are, in fact, wrong on every count.

The first point is that “like” isn’t just a filler word. It’s actually an incredibly versatile and dynamic word. The linguist Alexandra D’Arcy, who wrote a book on the word, outlined its many uses. There are its traditional uses as a verb, “I like the smell of what’s cooking” and a preposition, “This tastes like it was made in a restaurant”. Then there are the ones that are the subject of scorn. The first of these is the quotative “like”: “He cooked a spag bol for me last night, I was like, that’s delicious.” It allows you to tell a story without promising complete accuracy. Indeed, one of the most enjoyable things about this kind of “like” is that you can tell an anecdote that makes you sound wittier and more erudite than you actually are because you’re not promising exactly what was said but the feeling of what was said.

The other hated “likes” are as a discourse marker, “What did I do last night? Like, had dinner, hung out”; an adverb to mean approximately, “It was super quick to cook, like 30 minutes”, and what’s known as a discourse particle, which goes in the middle of a phrase, rather than at the end of it, “This dinner is like the best I’ve eaten.” But there are more uses than that, for example the Geordie tradition of finishing sentences with a like. “He cooked dinner for me, like,” and increasingly “like” is also used as a noun because of Facebook and Instagram, “I gave it a like.”

Many of these uses often overlap in a way that is incredibly rich. If you say, “He was like, seething about the pasta sauce,” you are quoting someone’s reaction, but at the same time highlighting you are approximating their response, while pausing to highlight that you are thinking meaningfully about this reaction in real time. That one word is doing all those jobs, all the while creating a sense of familiarity between you and the person you’re talking to.

The word’s incredible flexibility is nothing new either. Most people think the word “like” dates back to the 80s, as typified by the Frank Zappa song Valley Girl, in which his daughter, Moon Zappa, impersonates a California bimbo, ad-libbing that: “I, like, love going into, like, clothing stores and stuff, I, like, buy the neatest miniskirts and stuff. It’s, like, so bitchin.’” But it goes much further back. In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, written at the start of the 17th century, Valentine says to Cesario, “If the Duke continue these favours towards you, Cesario, you are like to be much advanced.” The linguist Anatoly Liberman says that this version of “like” was being used as a shorthand for likely, and may be the beginnings of our contemporary usage.

“Consider the following,” he writes. “‘All these three, belike, went together’ (1741, OED). Take away be-, and you will get a charming modern sentence: ‘All these three, like, went together.’” Belike meant “in all likelihood”.

It’s easy to imagine how this use of “like” could transform into like being used more generally as a way to break up speech. Perhaps it was aided by the Irish, Liverpudlian and Geordie use of the word to mean roughly “or thereabouts”. Or by the beat poets of 1950s, who would often start the sentences with “Like” (interestingly, fewer people now complain that these more masculine uses sound stupid, despite the fact they could also be described as filler words).

It’s true that young women in the 1980s probably invented the quotative “like”, but they are far from the only group to use it now. And research suggests that the discourse particle “like”, the one that comes in like the midpoint of a sentence, is used more by men than women. But the biggest lie about “like” is that it’s stupid; that it adds nothing to the meaning of a sentence. “People say language is random. But language is almost never random. You can’t just stick that like in anywhere,” says Fought. “So for example, if I say, ‘Oh look at that boy over there. He’s wearing a top hat. And he’s like, 10.’ That makes perfect sense. But if you say ‘How old is your brother’? And I say ‘He’s like, 10’ that’s a little more unusual. Or if I said, ‘My, like, grandma died.’ That’d be a very strange context to hear it. So there’s patterns. There’s ways to do it more grammatically.”

More than being internally logical, it is also a way of signalling. “It helps with what we call focus. I’m showing you this is the important part, this is the part that connects, it can be for interpersonal connection, it’s checking in that you and I are connecting. It’s an incredibly useful part of speech. If it really were meaningless and had no purpose in a sentence, it would be much easier for us to leave it out.”

This is what I think when I listen to Radio 1 or watch vlogs by young women like the TikTok star Emma Chamberlain or Billie Eilish, both of whom are heavy “like” users. They have this almost instinctual way of using language not just to convey meaning but to convey a moment around that meaning. It’s almost, like, magic.

Fought adds that although the debate around “like” can be fun, when it comes to teachers punishing children for saying the word there are more serious impacts. “There’s nothing more non-conducive to learning and contrary to the purpose of education than constantly shutting kids down because of how they talk. If you want to teach a kid to practise having different language styles, that’s fine. But to demean and criticise the way someone speaks in any situation is very, very harmful.”

So if linguists are largely agreed that “like” is, at least in some contexts, no bad thing, why does society still bristle at it? Katherine D Kinzler, the author of How You Say It, a book about linguistic bias – which she argues is one of the most persistent prejudices in our society – says that taking someone to task for the way they speak is one of the last societally accepted ways to exercise our prejudices. “Most people aren’t even aware this is something they might do. For example if you’re interviewing candidates for a job, it’s easy to think you’re not being biased, racist or sexist, that you’re just looking for a good communicator. But so many of our perceptions of who is a good communicator can be infused by other forms of biases that we’re not aware of.”

Kinzler says that “like” is a good example of a word where young women are chastised for talking a certain way even though that isn’t borne out in the linguistic data. “‘Young and female’ is often the group that is associated with a lot of these vocal features, but actually you find lots of people in the population speak this way. It’s a similar thing with uptalk, ending your sentence by going up, like it’s a question? It’s also assumed that it’s a Valley girl way of speaking when in fact it occurs with lots of different groups.”

In 2014, a mother wrote to the advice columnist in this magazine with a dilemma. “My adult daughter is clever, pretty and confident. However, she cannot stop saying ‘like’ about six times in every sentence… I know it is not the end of the world, but it makes her sound stupid and uneducated, which she most definitely is not, and when she wants to return to the real world I worry this will be held against her.”

I hope she would take some comfort in knowing that the best linguistic studies today suggest people who say “like” may actually be more intelligent than those that don’t. One, published in the Journal of Language and Social Psychology, which examined 263 conversational transcripts, found that “conscientious people” and those who are more “thoughtful and aware of themselves and their surroundings” are the most likely to use discourse markers such as “like”.

As Fought says, “I’m 55, I have a PhD, many people would consider that to be a sign of intelligence, and I’m a ‘like’ user. So this judgy thing, it’s natural, but it’s really not helpful.”

The Excessive Use Of The Word «Like»

LOG IN WITH FACEBOOK

I am part of a generation that uses the word “like” religiously. Increasingly and especially under the age of 40, people use the word “like” for many different purposes. I first became interested in researching the use of this word because I was thoroughly embarrassed by my college professor when he informed me that I used the word “like” 30 times since I had begun talking. Even though I knew he was right and that I used the word too much, I couldn’t help but feel embarrassed about my habit. After thinking about it, I decided I should make it a goal of mine to improve my language.

So the important question is, when can we acceptably use the word “like”? In which instances can we integrate this word into our speech and have it deemed appropriate by those around us – specifically in professional situations? Here’s what I found out.

Traditionally, the word “like” is used as a verb and to make a comparison. We can say, “I like that dog” or “he ran like the wind,” and we will not be criticized. The problem is when we start to use the word as filler. We place it randomly in a long sentence to extend what we’re saying or to portray something that we’re not quite sure about.

Commonly, we use “like” as a quotative. For example, we say sentences such as “My professor was like, ‘you say like way too much!’” Interestingly enough, I found that using the word “like” instead of “says” is totally acceptable. According to The American Scholar, using the word “like” allows the speaker to “vocalize the contents of participants’ utterances, but also his/her attitudes towards those utterances.” The word “like” can make multiple viewpoints clearer. It actually helps to more clearly portray a complicated sentence. Therefore, using the word “like” isn’t always bad.

Take that, professor. But I shouldn’t get ahead of myself.

The word “like” is the new “um.” We use it to fill uncomfortable gaps. But the use of “like” as a filler can be related to the language of a California Valley Girl, according to BBC News. This makes it frowned upon to say use the word “like” too much. It sounds unprofessional, especially to those over 45, who are not as accustomed to the use of “like” in language.

What I have found is that using the word “like” isn’t completely bad. Scholars claim that it is actually a very useful word in more ways than people may think. But it is important to keep in mind that using the word “like” too much in a professional setting is frowned upon.

Knowing this, I think that it is okay to use the word “like” as long as we don’t use it too often. From my research, I have learned that using the word as filler isn’t a good method of communication, but is more acceptable than I originally thought. I started this article with the intention to expose the word for making today’s language sound lazy, but found out that my hypothesis was not completely correct. Using the word too often can distract the listener from the intended message. No one wants their communication to be broken because of their excessive use of the word. But this does not mean that it doesn’t have its benefits.

Instead of completely eradicating the word from my every day language, I now know how to selectively choose when to utilize this overused word.

Thank you to my professor who challenged me to improve my language and served as the inspiration for this article. He showed me that though we may not always enjoy constructive criticism, it is vital for growth and we should try our best to learn from it.

Report this Content

Subscribe to our

Newsletter

/

×

-

#1

Dear all, which one is correct to say?

1) Too much use of the word «Like» while having a conversation with someone makes me feel that the person is unintelligent.

2) Too many uses of the word «like» while having a conversation with someone makes me feel that the person is unintelligent.

Thanks a lot.

-

#3

Both «much» and «many» are correct.

But both sentences have the same problem: who is using the word «like»?

This is a danger in English. If we say something passively and omit the subject, we do not say who is doing the action of that verb.

Your sentences don’t say who is saying «like». It could be you that is saying «like». In fact, it probably is you, since «someone» and «the person» are probably the same person.

-

#4

Both «much» and «many» are correct.

But both sentences have the same problem: who is using the word «like»?

This is a danger in English. If we say something passively and omit the subject, we do not say who is doing the action of that verb.

Your sentences don’t say who is saying «like». It could be you that is saying «like». In fact, it probably is you, since «someone» and «the person» are probably the same person.

Suppose A and B are two different persons. And they are having a conversation and I’m the third party, I’m listening to their conversation. What I find is «B» is constantly using the word ‘Like’ as a placeholder. B was reapiting the word in every sentences.Thanks a lot.

-

#5

There’s not much point in analysing the sentence as it stands, since it’s poorly written, as dojibear implies.

Too much use/many uses of the word «like» while having a conversation with someone makes me feel that the person is unintelligent.

If someone makes too much use of the word «like» in a conversation, they come across to me as unintelligent.

-

#6

There’s not much point in analysing the sentence as it stands, since it’s poorly written, as dojibear implies.

Too much use/many uses of the word «like» while having a conversation with someone makes me feel that the person is unintelligent.

If someone makes too much use of the word «like» in a conversation, they come across to me as unintelligent.

👍Thanks a lot

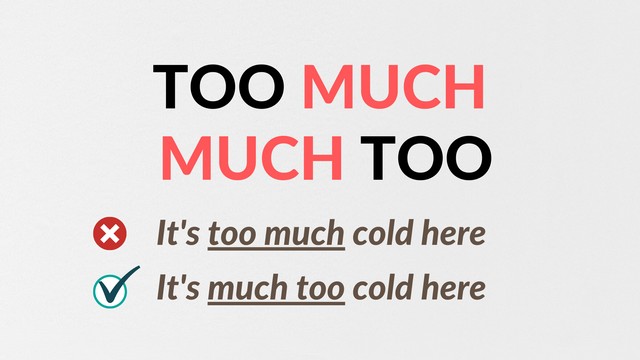

Одна из ошибок, которые я часто совершал — неправильное употребление too much. Я говорил так: «This is too much hard» или «The light is too much bright», то есть использовал too much с прилагательным. В этой статье я расскажу, как использовать наречие too в значении «слишком», too much и much too.

Как использовать too, far too, way too, much too, a little too, a bit too (в значении «слишком»)

Наречие too может значить «тоже» или «слишком». Как «тоже» оно обычно употребляется в конце утвердительного предложения.

I like vanilla ice-cream too! — Мне тоже нравится ванильное мороженое!

Подробнее о too в этом значении читайте в этой статье: «Разница между too и either». Сейчас нас интересует too в значении «слишком».

В значении «слишком» это слово употребляется перед прилагательными или другими наречиями:

You are too strict with children. — Вы слишком строги с детьми.

She is too young for the part. — Она слишком молода для этой роли

You drive too fast! — Ты едешь (на машине) слишком быстро!

Please, don’t speak too loudly. — Пожалуйста, не говорите слишком громко.

Добавив way или far, мы можем усилить наречие too, то есть way/far too — это уже не просто «слишком», а «слишком уж», «чрезмерно», «чересчур»:

This game is way too easy for me. — Эта игра слишком уж легкая для меня.

She is far too talented for such a small part. — Она чересчур талантлива для такой маленькой роли.

К этим же усилителям можно отнести и much, получается much too (именно much too, а не too much):

This fabric is much too delicate for tents. — Эта ткань слишком тонкая для палаток.

The director is much too unexperienced for such a big project. — Режиссер слишком неопытен для такого большого проекта.

Любопытно, что too можно не только усилить, но и ослабить: a bit too, a little too — «немножко слишком». Мы как бы говорим «слишком», но смягчаем выражение. Классический пример: «a bit too late», буквально «немножко слишком поздно» — обычно с долей иронии.

I’m afraid, you are a little (a bit) too late, I’m already married. — Я боюсь, что ты немножко опоздал, я уже замужем.

Теперь давайте посмотрим, как и когда мы используем too much.

Напомню, much too мы можем использовать с прилагательными и наречиями. В данном случае too («слишком») несет основное значение, а much — усиливает его:

He is much too short for a basketball player. — Он слишком уж невысокий для баскетболиста.

You talk much too slowly. — Ты говоришь чересчур медленно.

А вот too much НЕЛЬЗЯ использовать с прилагательными. В данном случае much (много) — это основное значение, а too — просто его усиливает, то есть too much = слишком много. Сочетание too much мы используем такими способами:

1. Перед неисчисляемым существительным или герундием

I spent too much time. — Я потратил слишком много времени.

You can’t have too much friendship in your life. — В жизни не может быть слишком много дружбы.

The reason of his disease is simple — too much smoking. — Причина его болезни проста — слишком много курения.

Напомню, слово much используется с неисчисляемыми существительными, а с исчисляемыми мы используем many. Подробнее об этом в статье: «Much, many, much of, many of — «много» по-английски».

2. После глаголов

You don’t feel well because you work too much. — Ты плохо себя чувствуешь, потому что слишком много работаешь.

Don’t drink too much. — Слишком много не пей.

Моя ошибка, которую я упомянул в начале, заключалась в том, что я использовал too much с прилагательными, а на самом деле с прилагательными нужно использовать much too, way too, far too или просто too:

- Неправильно: It’s too much cold here. — Здесь чересчур холодно.

- Правильно: It’s way/far/much too cold here. — Здесь чересчур холодно.

Также с too much есть полезное выражение «It’s too much!» — «это слишком!», «это уже перебор!»

I’m not going to lend you more money. It’s too much! You already owe me a lot! — Я не собираюсь давать тебе в долг еще денег. Это уже слишком! Ты уже и так мне много должен!

Здравствуйте! Меня зовут Сергей Ним, я автор этого сайта, а также книг, курсов, видеоуроков по английскому языку.

Подпишитесь на мой Телеграм-канал, чтобы узнавать о новых видео, материалах по английскому языку.

У меня также есть канал на YouTube, где я регулярно публикую свои видео.

August 15, 2013

“And so she was like, it’s, like, not really, like, a big deal? And I was like, but you don’t, like, even know what you’re talking about, so, like? You know?”

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. For better or worse, the word “like” is a part of the teenage vernacular, staging a takeover of a kid’s vocabulary on the eve of their thirteenth birthday. Of course, today’s teens might not be so inclined toward using it if they knew “like” was a throw-back to 1980s valley-speak, a dialect of California English spoken by Valley Girls and popularized in Frank Zappa’s song, “Valley Girl”.

“This isn’t a new phenomenon,” says Tori Cordiano, a consulting psychologist at the Center for Research on Girls at Laurel School in Shaker Heights, Ohio. “Teens tend to be more dramatic in their speech than adults. They often use ‘like’ to signal emotion (“I, like, lost it when I saw my grade”). They can also use it in place of the grammatically correct word (“He was like, I’ll call you” versus “He said, I’ll call you”). And they may do this more than most adults.”

That said, “like” does have two grammatically correct uses: similarity (“That shirt looks like mine!) or enjoyment (“I like this soup!”). It can also, less correctly, be used to approximate (“It was like six feet wide.”) or as a quotative—a word that can serve as spoken quotation marks.

But, these issues aren’t the real crux of the issue.

It’s sentences that, like, sound, like, this, with, like, every other word, like, being like. What’s that, like, even about?

According to John Ayto, editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Modern Slang, “like,” and its counterpart, “you know,” are filler words.

“We all use fillers because we can’t keep up highly-monitored, highly-grammatical language all the time,” Ayto says. “We all have to pause and think. We’ve always used words to plug gaps or make sentences run smoothly.”

Cordiano agrees. “A big reason why teens (and people in general) use the word, ‘like,’ is to fill space while speaking. Adults do this too, although adults may be more likely to use other filler words, such as ‘umm’ or ‘ahh’.”

For some parents, the verbal tic is simply too annoying to stand. “My oldest daughter used to say, ‘like,’ all the time,” says Karen Vargas, whose two teenage sons have never picked up the habit. “It drove us all completely crazy! Sometimes it was hard to even have a conversation with her.”

Others worry that it will make their teenager appear unprofessional in job or academic interviews, but Cordiano says not to worry. “For most teenagers, this isn’t something that parents need to be too concerned about, although many parents describe it as annoying. Similar to teen slang used by previous generations, most of today’s teens tend to decrease their overuse of this word, especially in professional situations, as they mature.”

If it’s a concern for you, there are ways around it.

3 Strategies to Decrease Saying the Word “Like”:

1. Become aware

Cordiano says, “Parents can do a little bit of coaching to decrease its use or to use it correctly. Help your teens to become more aware of their use of the word.” A great strategy for increasing awareness is to simply keep count of the number of “likes” your teen utters in a day. They may be surprised at the total.

2. Replace “like” with a different filler

Cordiano suggests developing this helpful skill: “Teach them to replace the filler word with a pause or a breath.” Advise them to pause when they feel a “like” coming on, rather than uttering the word. Pausing will make them sound more authoritative than using a filler.

3. Expand your vocabulary

And, encourage them to broaden and strengthen their vocabulary. The more words they have at their disposal, the easier they can express a thought and rely less on fillers.

With all that said, don’t, like, mind it too much. Obnoxious though it can seem, most teens do grow out of their “like” phase. And, besides, the word serves the noble purpose of giving teens time to consider what they’re saying before they say it. After all, isn’t that, like, what we want?

Do you think the word like is used too much by young people?

Learn some different ways we use the word like in English conversation and informal spoken English and see the word like in action in a conversation with Super Agent Awesome.

One use that’s common with young speakers is the quotative like. That’s when they use ‘like’ instead of says or thinks to report someone’s words or thoughts.

Some people complain that the word like is used too much by young people and it’s sloppy English. But it isn’t just youthful slang and there are useful functions that like performs.

We’ll show you how like can signal approximation or exaggeration, how we use like as a discourse marker and also how like can be combined with a dramatic face to describe someone’s feelings.

Click here to learn the difference between ‘Do you like…?’ and ‘What’s it like?’

Click here to learn how to use ‘be like’, ‘look like’ and ‘be alike’.

‘Like’. This is such a common word in English, but do you know how it’s used in colloquial English? And do you know what it means in teenage slang?

Today we’re very lucky to have some help. Super Agent Awesome is here.

Thank you Vicki.

I’m Jay and I’m American.

And I’m Vicki and I’m British.

The word ‘like’ has several meanings in English.

It can be a verb. For example, ‘I like you’.

I like you too!

And it can also be a preposition.

So we could say ‘What’s it like? or ‘It looks like …’

I’ll put a link here to other videos we’ve made about that.

But today we’re looking at some colloquial uses of ‘like’ – in other words how we use it when we’re speaking informally.

And in slang. It’s a word that young people use a lot.

Luckily we have Super Agent Awesome to help us.

Let’s see an example.

The quotative like

Is there anything you complain about doing?

I will be like Mom, ‘I want to play Fortnite again. Please, please, please!’

So you complain about not playing Fortnite.

Yeah, I feel like everyone should play Fortnite!

Did you catch it?

He said ‘I feel like everyone should play Fortnite.’

Well he loves that game, but he also said this.

So he used ‘like’ to report what he’ll say to his Mom.

This use of ‘like’ is particularly common with young people.

We call this the quotative ‘like’ because it’s about quoting what people say and also what they’re thinking. So it has a more general meaning than just ‘say’. It can mean ‘think’ too because you can use it to describe inner feelings and thoughts.

Notice we always use the verb ‘be’ here. You can change the tense, so you can use the future ‘I will be like …’ Or the past, ‘I was like …’ but we always use the verb ‘be’.

Is this use of like just an American thing?

No. Though they think it started in California in the 1980s. But it’s used by English speakers all over the world these days.

Do you think like is used too much?

Some people complain that young people use the word ‘like’ too much. They think it’s sloppy English.

Sloppy. Sloppy means without care or effort.

Do you think it’s sloppy and lazy?

No. I think it’s very interesting because languages change over time and if you look carefully, you find ‘like’ has new and useful functions in English. It can signal what we say and think and it can signal other things too.

Then let’s look at another example.

More functions that like performs

Do you ever complain about having to go to bed at a certain time?

Yeah. So one time, I was watching a movie, um, it was like Hotel Transylvania III. And then there was this really dramatic action scene, and like the villain is about to beat the hero, or the hero is about to beat the villain, but then Dad stopped me and I had to go to bed.

Uhuh.

Why did he say ‘like’ here?

Well he was remembering, but he wasn’t totally sure. Perhaps that was the movie, or perhaps it was a different one.

So ‘like’ signaled he wasn’t sure?

Yes and he said it again later.

Now the hero is the good guy and the villain is the bad guy.

And he couldn’t remember who was winning, so he signaled that by saying ‘like’

‘Like’ signaled he wasn’t sure.

Yes. This isn’t just a feature of young people’s speech. We use ‘like’ in the same way.

It signals uncertainty or that something is approximate.

For example, it’s like this big. And it could be this big or it could be this big.

‘Like’ signals an approximation.

It means what I’m saying might not be perfectly accurate. And it can also signal exaggeration. It’s like this big!

That sounds like a useful function!

And another way we use ‘like’ is as a discourse marker

What do you mean?

It’s a word we use to organize our speech. For example … Like … Well … So … We put like it at the start of a sentence when we’re thinking of what to say.

So it’s a filler. Like Errr … and Umm …..

Yes, it’s a word that fills a space and helps us speak more smoothly.

OK. Let’s hear another story.

Can you name something that you’ve had to apologize for doing?

Oh I know, I know, I know, I know. The time where I buried my Dad’s ring. I had to apologize for burying my Dad’s wedding ring.

Before we carry on, do you know the word ‘bury’.

It means to put something in the ground.

When people die we bury them. It’s a regular verb. Bury, buried, buried.

A dog could bury a bone in the ground.

We can bury treasure too.

I had to apologize for burying my Dad’s wedding ring. The reason why I did it was because I wanted to use the metal detector. Then I told my Dad and said ‘Dad, where’s the metal detector?’ Then my Dad was like your brother took it apart a couple of months ago, and then I’m like … Dad was like ‘Yo, what’s wrong?’ And then I was like Argh! I buried your wedding ring. And then my Dad was like … Oh! So that’s why you wanted to use the metal detector.

Did you understand everything?

He buried his Dad’s wedding ring in the yard.

Or in British English, the garden.

He buried it in the yard so he could try to find it with the metal detector.

But their metal detector was broken because his brother had taken it apart.

Did they ever find the ring?

No. I think it’s still lost. Let’s hear what his Dad said again.

And then my Dad was like … Oh! So that’s why you wanted to use the metal detector.

He’s lucky because his Dad is really nice.

He was very understanding.

OK, there was one more use of ‘like’ there that’s common and pretty funny.

Your brother took it apart a couple of months ago and then I’m like ….

So you can say ‘like’ and then make a funny face.

It’s very common.

And easy too. No words, just a dramatic face.

I want to say a big thank you to Super Agent Awesome for helping us make this video.

He was like … !

If you enjoyed this video, please give it a thumbs up and share it with your friends.

See you next week everyone. Bye.

Bye-bye.

Click here to learn the difference between ‘Do you like…?’ and ‘What’s it like?’

Click here to learn how to use ‘be like’, ‘look like’ and ‘be alike’.

© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy