Today, I am here to set you free from one of the shibboleths of grammar. You will be liberated! I certainly was. At school, we were taught you should never, ever, under any circumstances start a sentence with a conjunction. That rules out starting sentences with either “and” or “but” when writing. I faithfully learned the rule. I became positively angry when I read books in which otherwise excellent writers seemed to make this faux pas. How could they be so sloppy?

One day, I decided to settle the matter once and for all. I would find an authoritative reference to back up what I had learned, and I would send it to someone who had just argued you can start a sentence with “but.”

Being Wrong Can Make You Happy

Once I started to check, I quickly realized I was going to be proved wrong. People, including some of the greatest writers of all time, have been starting sentences with “and” and “but” for hundreds of years. Of course, there are style guides that discourage it, but it’s perfectly acceptable to begin a sentence with “but” when writing. I was thrilled! That very day, I started peppering my writing with sentences starting with conjunctions. But one shouldn’t go overboard! See what I did there? Hah!

Using any stylistic quirk too frequently spoils your writing. By all means, start sentences with “but” from time to time, but remember that “but” also belongs after a comma. I did it again, didn’t I?

When Should You Consider Starting a Sentence With “But”?

“Contrary to what your high school English teacher told you, there’s no reason not to begin a sentence with but or and; in fact, these words often make a sentence more forceful and graceful. They are almost always better than beginning with however or additionally.” (Professor Jack Lynch, Associate Professor of English, Rutgers University, New Jersey)

Thank you, professor! I’ll admit to using “however,” but being lazy, I really do prefer the word “but” to begin a sentence when given a choice. “Additionally” is just awful, and I flinch every time I start a sentence with it. It seems so pompous!

The professor also confirms starting with the conjunction can make your writing more forceful. Remember, you don’t always want to be forceful. Sometimes sentence flow is more appropriate. But a choppy “but” at the start of a sentence certainly does seem to add emphasis when that’s what you’re looking for.

People Are Going to Argue This With You

Just as I once was a firm believer in the “never start a sentence with and or but” non-rule, you’ll come across enslaved souls who have been taught the very same non-rule. Where can they turn for confirmation and comfort? The Bible is always a good place. Refer them to Genesis Chapter 1 for sentences starting with “and.”

For a sentence starting with “but,” you may have to read a little further – all the way to Genesis 8:1: “But God remembered Noah and all the wild animals and the livestock that were with him in the ark, and he sent a wind over the earth, and the waters receded.”

Looking around online, I see some arguing that using the Bible as a work of English literature is pushing the envelope. I beg to differ, but perhaps as the world’s greatest bestseller, it’s a bit too commercial for them. Let’s take them to the real authority: the notoriously stuffy and pedantic, Fowler’s Modern English Usage. It’s seen as the authoritative book on English Grammar, and if they won’t believe it, they’re never going to believe anyone.

If they’re trying to find a comeback, you can always help them out. But they won’t be impressed with the reference you give them because I’m ready to bet you anything they’ve never have heard of Quackenbos!

“A sentence should not commence with the conjunctions and, for, but, or however…. ” (George Payn Quackenbos, An Advanced Course of Composition and Rhetoric, 1854)

Let’s sum up that argument, ladies and gentlemen of the jury. We have the Bible, a host of brilliant writers, and Fowler’s Modern English Usage vs… Quackenbos. I’ll see your Quackenbos and I’ll raise you an Albert Einstein. Oops, we’ve gone from law to poker. Please pardon the mixed metaphors. Of course, Shakespeare also occasionally mixed metaphors, but we’ll go into that another time, shall we?

Why Were Students Taught This Non-Rule Rule?

Why were we taught this non-rule rule about not starting sentences with conjunctions? Several authorities seem to think it was done to prevent school kids from writing as they often talk:

“I went to my friend’s house yesterday. And we decided to go to the mall. And while we were there we saw a whole bunch of our friends. And they were just hanging out like we were. And because we didn’t have any money that was all we could do, really.”

Or

“But then John said he’d had a birthday, and we could all go for ice creams. But when we got to the ice-cream parlor, he found that he had left his wallet at home. But that didn’t stop us from having a good time together while teasing John that he owed us an ice-cream.”

You have to admit, that’s a bit much. So to close, we quote Oscar Wilde, “Everything in moderation, including moderation.”

-

#1

hey there,

Is there actually a rule about using But at the beginning of sentences. I remember being told in school that it should never be done ( like Basoonery’s point about the Oxford Comma) but of course see it everywhere. Is there an actual grammatical rule or is it just a question of style?

-

#2

I’m pretty sure it’s a rule that «But» cannot be used at the beginning of a sentence, but as you said, many people disregard it.

-

#3

Conjunctions at the start of sentences are to be used with caution.

As a general rule of thumb, beginners in English should avoid them.

In practice, you will find that many, if not most, experienced English writers will start sentences with conjunctions.

If these forums were to ban the use of conjunctions at the start of sentences, a very large proportion of my posts would have to go.

In other words, there is a guideline for beginners that cautions against starting a sentence with but. It is not a grammatical rule.

If you studied science, you may remember being taught at first that an atom was the smallest indivisible particle of matter. Then when you learned more you discovered electrons, protons and neutrons.

Enough knowledge for you to survive a few years.

Then along came lots more sub-atomic particles and wave theories and cats in boxes.

English is rather like that. There are models of usage that are appropriate for each level of development. Then you discover that the model was a partial model and you learn something new — for example that is is entirely normal in English to begin a sentence with a conjunction.

-

#4

yeah that makes sense. As far as I remember it was just in primary school that the teacher would insist on such models. Ta!

-

#5

The «rule» had a purpose.

Beginning writers often keep on going without considering the structure of their sentences and introduce new concepts within sentences but never think of the risks of skating without the proper protective equipment and insist on eating their peas with honey on their knives instead of carefully polishing their glasses and making sure they use the correct spoon for each course.

Then they break up the run-on sentences with punctuation. The result is fractured sense and dreadful sentences. And many of the sentences begin with conjunctions simply because the word before the conjunction concluded what they thought was a sentence-worth. But do not despair.

When you have mastered the art of using capital letters at the beginning of sentences, you too might be considered fluent enough to begin a sentence with But

-

#6

Cheeky! Both my punctuation and spelling tend to be pretty desperate alright but that’s why I’m here

-

#7

Mary Therés,

Stay awhile and you’ll be able to mix metaphors just as well as Panjandrum….skating over to the buffet table to get some honey and peas on my knife.

However much you may have been told of rules and their supposed sanctity, many of them are nothing but stylistic conventions, some very useful, as Panj has pointed out, and others just hand-me-downs that are ragged around the knees.

-

#8

I have an English-major friend that insist it’s always, 100% wrong to use ‘and’ or ‘but’ at the beginning of sentences. I’ve wrangled with her for YEARS!

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

-

#9

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

![Stick Out Tongue :p :p]()

And that, as they say, is the end of that.

-

#10

I have an English-major friend that insist it’s always, 100% wrong to use ‘and’ or ‘but’ at the beginning of sentences. I’ve wrangled with her for YEARS!

I think everything that needs explaining has been explained; I just wanted to add my two cents in.

Tell your friend, ‘Rules are for the obedience of fools and the guidance of wise men.’

(Bear in mind though that this quote is attributed to Douglas Bader who broke the rules on low-level aerobatics and ending up having both legs amputated… )

-

#11

But don’t forget that he also become a very good golfer afterwards, married the girl he wanted, had a nice career in the RAF, crashed another airplane and lived happily ever after.

Pass the peas and honey, please, Winklepicker.

-

#12

Pass the peas and honey, please, Winklepicker.

I’ve done it all my life, Cuchu.

-

#13

For your continued edification, just google «History of English,» or «English grammar.»

-

#14

As we are being very precise and specific in our advice, why not just google «Which came first—the language or the grammarians?»

-

#15

I also had it drilled into my head since grammar school that it was definitely a «no no» to use either and or but at the beginning of a (written) sentence. Although I might use either or both in emails or personal correspondence, I try to avoid it on the English only forum.

But I’m glad that the subject came up so that members who are doing writing assignments for class will know that conjunctions at the beginning of sentences probably won’t be acceptable to their English professors.

-

#16

In the last but one, him would no doubt have been defended by the writer, since the full form would be he whom, as an attraction to the vanished whom.

But such attraction is not right

; if he alone is felt to be uncomfortable, whom should not be omitted; or, in this exalted context, it might be he that.

emphasis added.

Take a guess as to the author of the quoted material.

It was one H.W. Fowler!

http://www.bartleby.com/116/201.html

-

#17

I also had it drilled into my head since grammar school that it was definitely a «no no» to use either and or but at the beginning of a (written) sentence. Although I might use either or both in emails or personal correspondence, I try to avoid it on the English only forum.

But I’m glad that the subject came up so that members who are doing writing assignments for class will know that conjunctions at the beginning of sentences probably won’t be acceptable to their English professors.

A Christmas Carol

Do a search for «But». Make sure you mark «match case». I believer there are nearly ten sentences starting with but, and that’s only considering the narrative.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

At least three «but’s» in the first chapter. (Click on chapter one.)

Gullivers-Travels

Nice in the first chapter.

I wonder what these gentlemen were taught in school? Surely such «poor» writing could not have been acceptable to their English teachers.

Gaer

-

#18

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

-

#19

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

Okay, so what exactly is the difference between «but» and «although» or even «yet» or «nevertheless?» (Okay, sometimes there is a difference.) Pan is essentially right about why the rule is there, but I’ll agree that it’s perfectly acceptable to use «but» once you know the language (and the difference). The difference between the above is sometimes an artificial grammatical distinction and «but» is at times the most direct and best word to use. Plain talk, as opposed to high falutin’. (Next thread?)

That said, I’ll tell you a story. A couple of years ago I took the GRE’s. I got a perfect score on the verbal. ( I guessed at least once and got lucky—though I don’t consider it luck so much as good logic.) They had just instituted a written element. Essays. (Now, [But. But «but» wouldn’t work as well as «now» here. Close, but no cigar] I could write that just as well by saying: They had just introduced a written element: essays.) I wrote elegant, nuanced arguments, and got a sub-par score. I started a sentence or two with «but.» Might have had a sentence fragment or two in there for effect.

I suspect I received a poor score due to grammar robots.

That’s life.

Can’t deny it.

Lack of judgement on my part.

Barnaby

-

#20

hi

I hate to see » But» at the start of a sentence and tend to use «however» instead. I am still dogged by the very fierce English Teacher I had for my «O» levels at school and every time I write «But» I can hear her terrifying tones.( She wouldn’t let us use a knife like a pen either, so that is another of my pet hates) Oh the baggage we pick up as children!!!

-

#21

Send that fierce English Teacher a pen, some honey and peas, and a copy of Fowler’s

Modern English Usage

, together with instructions to find every sentence Henry Fowler began with but.

There is one example a few posts above this one. Her discomfort should help attone for that she has caused you.

-

#22

But shouldn’t be use as the start of the sentence; it makes a fragment. But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.

However, it is possible to use but that way as a style method; it is a way to put emphasis on a subject.

You have had rules and pseudo-rules drilled into you. But there is hope! You seem to at least accept that there are stylistic grounds on which to base the use of but at the start of a sentence. It doesn’t necessarily make a fragment.

-

#23

hi

I hate to see » But» at the start of a sentence and tend to use «however» instead. I am still dogged by the very fierce English Teacher I had for my «O» levels at school and every time I write «But» I can hear her terrifying tones.( She wouldn’t let us use a knife like a pen either, so that is another of my pet hates) Oh the baggage we pick up as children!!!

Have you look at the links I posted? I wonder if anyone has.

Are you saying that you hate to see «but» at the beginning of a sentence by Dickens? Or by Oscar Wilde?

And doesn’t that make you wonder if you have ever noticed what is really used by great authors?

The fact is that we are often so brain-washed by pedantic nit-wits that it blinds us to what is actually used by people who are masters of the English language.

Gaer

-

#24

The thing is, gaer, that well used Buts are completely transparent.

Carelessly used Buts stick out like sore thumbs.

-

#25

Macbeth:

But I am faint, my gashes cry for help.

But screw your courage to the sticking-place,

But wherefore could not I pronounce ‘Amen’?

But let the frame of things disjoint, both the

worlds suffer,

What a pity. If only Shakespeare had had proper instruction, he might have been a good writer.

Gaer

-

#26

The thing is, gaer, that well used Buts are completely transparent.

Carelessly used Buts stick out like sore thumbs.

You have a good point. Apparently all the authors I mentioned in previous links were so subtle about their «rule-breaking» that few people have «caught» them

breaking

the «rules».

Gaer

-

#27

Okay, so what exactly is the difference between «but» and «although» or even «yet» or «nevertheless?» (Okay, sometimes there is a difference.) Pan is essentially right about why the rule is there, but I’ll agree that it’s perfectly acceptable to use «but» once you know the language (and the difference). The difference between the above is sometimes an artificial grammatical distinction and «but» is at times the most direct and best word to use. Plain talk, as opposed to high falutin’. (Next thread?)

That said, I’ll tell you a story. A couple of years ago I took the GRE’s. I got a perfect score on the verbal. ( I guessed at least once and got lucky—though I don’t consider it luck so much as good logic.) They had just instituted a written element. Essays. (Now, [But. But «but» wouldn’t work as well as «now» here. Close, but no cigar] I could write that just as well by saying: They had just introduced a written element: essays.) I wrote elegant, nuanced arguments, and got a sub-par score. I started a sentence or two with «but.» Might have had a sentence fragment or two in there for effect.

I suspect I received a poor score due to grammar robots.

That’s life.

Can’t deny it.

Lack of judgement on my part.Barnaby

1. It is important to master the language; however, it is not the only element one needs to use BUT as the beginning of the sentence. The understanding of the meaning behind the sentence and the reason for using it is equally important. Whenever I use BUT as the beginning of a sentence for school, even though the sentiment may be right, it is always rejected with the reason of being a FRAGMENT. It is better to be that way I think. This is so that when one is developing one’s style, it can be based on the correct grammar.

2. But, yet, although and nevertheless maybe similar meaning-wise sometimes; however, the uses in a sentence are different. But, yet and although are conjunctions. But and yet are used to denote a turning point in a sentence. Thus, I think it makes more sense to be used after the main clause, separated by a comma. Although denotes an adverb clause and is commonly used in the reversed position, where the subordinate clause goes first, followed by a comma and the main clause. However, when although is after the main clause, the comma is not used. Nevertheless is a conjunctive adverb. It has be to separated from the main clause by a semicolon or a period.

3. I don’t understand why you quoted me when your posting is talking about Panj’s explanation. Your posting also mentioned your GRE story, but I do not understand what you are trying to convey. Moreover, I suspect a underlying sarcasm.

4. I would rephrase the sentence for the newly implemented essay. Although they had just instituted a written element, I still got a perfect score on the verbal.

-

#28

You have had rules and pseudo-rules drilled into you. But there is hope! You seem to at least accept that there are stylistic grounds on which to base the use of but at the start of a sentence. It doesn’t necessarily make a fragment.

I am just stating the rule.

There is no more to it.

I accept fully the stylistic component of the language.

I use but fragments way too much.

But I don’t know.

Maybe I am wrong.

But wait, it is good to use but to express one’s sentiment in different ways.

I like to give sudden changes in my writings to catch the reader.

But not everyone agrees with me.

-

#29

I am just stating the rule.

No. You are stating «a» rule.

Yes, there is.

I accept fully the stylistic component of

thelanguage.

If you are talking about «English», then it should be «the English language». If you mean «language» in general, then there is no need for an article there.

I use

but fragments«but fagments» way too much.

But I don’t know.

Maybe I am wrong.

But wait, it is good to use

but«but» to express one’s sentiment in different ways.

I like to

givemake sudden changes in my

writingswriting to catch the reader.

But not everyone agrees with me.

What is your point?

Anyone can write several short sentences.

I can too.

It’s highly unusual.

Normally it doesn’t work.

Not very well.

You do not need to use «but».

The monotony is boring without that little word.

Gaer

-

#30

No. You are stating «a» rule.

I am state the rule for but.

No. There isn’t more to my stating the rule.

If you are talking about «English», then it should be «the English language». If you mean «language» in general, then there is no need for an article there.

What forum are we in here?

What is your point?

Anyone can write several short sentences.

I can too.

It’s highly unusual.

Normally it doesn’t work.

Not very well.

You do not need to use «but».

The monotony is boring without that little word.Gaer

I am not talking to you nor am I replying to your postings in that posting.

Short sentences are effective in conveying brief ideas.

It is not highly unusual.

Even your short sentences give complete meaning and clearly state your point view.

I use but fragments way too much is another use of but. Being an experienced English speaker you should know that.

I like to give sudden changes [to my stories] in my writings (as in all the things I have written).

These are all legitimate uses.

-

#31

I think the progress of this thread demonstrates with exquisite precision the way in which sentences beginning with conjunctions can be a transparent and elegant part of an intelligent discourse.

And that the guidelines suggesting avoidance of this practice are well-advised.

-

#33

It’s fine when but means however and and means furthermore.

-

#34

Welcome to the forum, Rover.

Do you mean all the But sentences so far in this thread are fine except possibly «But of course»?

-

#35

«But denotes a subordinate clause and needs a main clause to explain its meaning.»

Not (always) so, I’m afraid. «But,» like «and,» is often a coordinating conjunction, joining two fully fledged main clauses. E.g., «Prescriptive grammarians are found in front of many classrooms, but most of them are egregiously wrong.» If you substitute a period for the «but,» you have two perfectly complete sentences.

See http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/coordinatingconjunction.htm

-

#36

So is the original question now resolved????

-

#37

Yes, it is.

Yes, there

is

a rule (everyone is free to ignore rules).

And/But yes, it

is

a question of style (as demonstrated by Shakespeare, et al.)

-

#38

My feeling is that academics are becoming more and more open to the idea that one can start a sentence with the word «but». But this doesn’t mean that everyone thinks it’s correct.

Is there any reasonable way one can defend beginning a sentence with «but» to one who thinks it’s unequivocally «incorrect»?

-

#39

I do it at times to break up the length of my sentences. Is that bad?

-

#40

I think it’s good, especially when it cuts unruly sentences down.

-

#41

Point out that they haven’t the slightest idea what they’re talking about. Sentence-initial ‘but’ always has been Standard English — it would be helpful here to have a list of uses of it by Dickens, Jane Austen, Johnson, and so on, but I haven’t got one to hand. Instead, I can look up Fowler’s Modern English Usage under the word but, where he discusses a number of points of grammar about the word at great length, but none of them is about its being in initial position. He isn’t even aware of this nonsense to dismiss it. But in the course of his prescriptive grammar advice he writes at one point, ‘But just as I shouldn’t wonder if he didn’t fall in is often heard’; and a little later he offers ‘But Mary decided‘ as a rewriting of a sentence with the word internally. The fake rule against initial position wasn’t even on the radar in 1930.

Don’t give any leeway at all to the ignoramuses who trot out this garbage. Don’t say the rule is changing, or has relaxed. There never was such a rule.

-

#42

Bravo to entangleddebunker of non-rules. We have discussed this one in a number of prior threads. There are some ignorant pedants abroad in the land (and probably quite a few more at sea) who try to impose their groundless stylistic preferences as «rules».

This particular «rule» is pure hokum.

The Fowler brothers ignored the matter of but at the start of a sentence because there was nothing to discuss.

More recently, it has received some well-deserved attention from Bryan Garner, in

A Dictionary of Modern American Usage.

but. A. Beginning Sentences with. It is a gross canard that beginning a sentence with but is stylistically slipshod. In fact, doing so is highly desirable in any number of contexts, and many stylebooks that discuss the question quite correctly say that but is better than however at the beginning of a sentence.

Garner goes on to quote seven such stylebooks. Here is one of the passages he quotes:

«Of the many myths concerning ‘correct’ English, one of the most persistent is the belief that it is somehow improper to begin a sentence with [and, but, for, or, or not]. The construction is, of course, widely used today and has been widely used for generations, for the very good reason that it is an effective means of achieving coherence between sentences and between larger units of discourse, such as paragraphs.» R.W. Pence & D. W. Emery, A grammar of Present-Day English

Last edited: Jan 20, 2010

You should never start a sentence with the words “and” or “but”—never.

If that was drilled into your head at some point during your elementary school English lessons, then you’re not alone. Most of us were taught this rule in school—and we followed it with every writing assessment, research paper, and book report we ever wrote.

So, if it’s improper to start a sentence with the words “and” or “but” then why do so many prolific, notable writers do it? As do bloggers, journalists, and copywriters. It might seem like a rebellious move—but the truth is, it’s not really “against the rules” at all.

Telling It Straight

The truth is, it’s okay to start a sentence with the words “and” or “but”—if you do it correctly. After all, there is a time and place for everything, right?

First, let’s take a quick jump down memory lane to those Schoolhouse Rock! tapes you watched when the substitute teacher didn’t know the subject. Ever had the tune to “Conjunction Junction” stuck in your head for no apparent reason? You’re not alone.

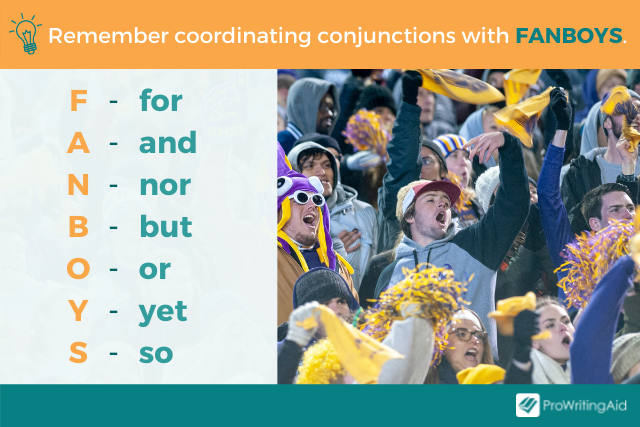

However, after so many years, do you remember what the function of a conjunction really is? It might seem obvious—a conjunction connects two thoughts or ideas. “And” and “but” are called coordinating conjunctions and are a part of a much longer list of words.

There are seven coordinating conjunctions:

- and

- but

- or

- nor

- for

- so

- yet

However, the ones we were specifically taught to avoid starting a sentence with are “and” and “but.” The good news is, you can rest easy knowing that there is no true grammar rule that says you can’t ever start a sentence with one of these conjunctions.

“Contrary to what your high school English teacher told you, there’s no reason not to begin a sentence with but or and; in fact, these words often make a sentence more forceful and graceful. They are almost always better than beginning with however or additionally.” — Professor Jack Lynch, Associate Professor of English, Rutgers University, New Jersey

Why Were We All Taught a Rule that Doesn’t Exist?

Realizing now, ten, twenty, or even thirty years or more later that you were lied to might be frustrating—but your teachers really did have your best interests in mind. While there is no definitive answer as to why we were taught this “rule,” the explanation that makes the most sense was that it was meant to prevent kids from writing the way they talk.

Think about it—have you listened to a child or teenager talk for any extended amount of time? If you have, then you can understand exactly what these teachers were trying to avoid.

If you haven’t—well, these two examples will help provide some insight…

“We wanted to go to get burgers and they weren’t open. But we still got burgers. But we had to go somewhere else to get them. But they weren’t as good as the ones we were going to get.”

“My friend and I went to the beach yesterday. And while we were on the beach, we saw lots of seagulls and other birds. And this one seagull stole some guy’s fries while he was trying to eat them! And it scared the guy so much, he jumped nearly ten feet in the air!”

It’s one thing to verbally hear a story told in this fashion. But reading it is an entirely different experience. No matter what the word is, you never want to start too many consecutive sentences with the same word. The overuse of “and” and “but” in spoken English is likely the main reason our teachers forbid us from starting a sentence with them in our writing!

When Is It Okay to Start a Sentence with “And” or “But”?

So, if there is a time and place for everything—where is the proper time and place to use “and” or “but” at the beginning of your sentence?

The first thing you want to remember is that you’re using this word to connect two thoughts—so your phrase should be able to stand on its own. This means it has a clearly defined subject and verb.

If you remove your conjunction and you suddenly have a sentence fragment that doesn’t seem to make sense, then you need to rework your wording. Perhaps this means making your two sentences one—using “and” or “but” with a comma, rather than a period.

You should also take into consideration what you are writing. Different types of writing call for different approaches. The use of “and” or “but” at the start of a sentence sometimes brings a sense of informality. It might be right for your blog posts, whereas more formal coordinating conjunctions like “additionally” or “however” might read better in a white paper.

The bottom line is though, it’s never truly off limits. Sometimes it’s more impactful to be so precise and direct.

When Should You Follow the Old “English Class Rule”?

In most business writing—especially digital marketing copy like blog posts, emails, and social media posts—you shouldn’t stress using “and” or “but” to start your sentence. No one is going to point it out. No one is going to laugh at you. In fact, someone else who doesn’t already know the truth might think you’re the rebel for being so daring in the first place!

But there are times when you’ll want to follow this mock rule. Data-driven content—case studies, statistic focused white papers, text book content, these are places where you might not only see less opportunity to start a sentence with a conjunction, but also where it could be beneficial to avoid doing so.

If you’ve already got years of practice avoiding starting your sentence with one of these words, then it might take some retraining to find yourself starting a sentence this way. On the other hand, following this rule helps you to expand your vocabulary and use other words and phrases to get your points across. (I could have used “but” to start that last sentence; «on the other hand» adds variety while also giving a stronger sense of weighing up options.)

Breathe Easy Knowing You’re Not the Only Misled Student

It’s been years now since teachers started drumming into students that they should never—ever—start their sentence with the words “and” or “but.” If you’re one of likely millions who was taught this lie during your schooldays, don’t feel bad. This is just another case of a few people creating a problem for the rest of us.

Since teachers didn’t think they could trust some students to be more creative in telling their stories, they restricted everyone. Sure, it worked—you’ll hardly come across something written on the internet with repetitive starts, especially not “and” or “but”—but at what cost? Many of us were following a grammar rule that doesn’t exist—and probably got irrationally mad that editors missed such a common mistake again and again.

Can you already feel the weight lifted? If you’re one of many who has been avoiding using “and” or “but” to start a sentence, don’t hold back! It’s the freedom that comes with finding out a constraint you’ve worked around for years is no longer an issue.

Try using this new technique in your writing to create more direct and powerful statements.

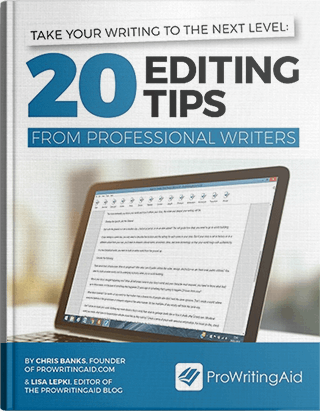

Take your writing to the next level:

20 Editing Tips From Professional Writers

Whether you are writing a novel, essay, article or email, good writing is an essential part of communicating your ideas.

This guide contains the 20 most important writing tips and techniques from a wide range of professional writers.

Susanne Alfredsson / Getty Images

Updated on February 05, 2020

According to a usage note in the fourth edition of The American Heritage Dictionary, «But may be used to begin a sentence at all levels of style.» And in «The King’s English», Kingsley Amis says that «the idea that and must not begin a sentence or even a paragraph, is an empty superstition. The same goes for but. Indeed either word can give unimprovably early warning of the sort of thing that is to follow.»

The same point was made over a century ago by Harvard rhetorician Adams Sherman Hill: «Objection is sometimes taken to employment of but or and at the beginning of a sentence; but for this, there is much good usage» (The Principles of Rhetoric, 1896). In fact, it has been common practice to begin sentences with a conjunction since at least as far back as the 10th century.

The Usage Myth Persists

Still, the myth persists that and and but should be used only to join elements within a sentence, not to link one sentence to another. Here, for instance, is an edict found recently on an English professor’s «Composition Cheat Sheet»:

Never begin a sentence with a conjunction of any kind, especially one of the FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so ).

This same fussbudget, by the way, outlaws the splitting of infinitives — another durable grammar myth.

But at least the professor is in good company. Early in his career, William Shawn, longtime editor of The New Yorker magazine, had a penchant for converting sentence-initial buts into howevers. As Ben Yagoda reports in «When You Catch an Adjective, Kill It», Shawn’s habit inspired one of the magazine’s writers, St. Clair McKelway, to compose this «impassioned defense» of but:

If you are trying for an effect which comes from having built up a small pile of pleasant possibilities which you then want to push over as quickly as possible, dashing the reader’s hopes that he is going to get out of a nasty situation as easily as you have intentionally led him to believe, you have got to use the word «but» and it is usually more effective if you begin the sentence with it. «But love is tricky» means one thing, and «however, love is tricky» means another — or at least gives the reader a different sensation. «However» indicates a philosophical sigh; «but» presents an insuperable obstacle. . . .

«But,» when used as I used it in these two places, is, as a matter of fact, a wonderful word. In three letters it says a little of «however,» and also «be that as it may,» and also «here’s something you weren’t expecting» and a number of other phrases along that line. There is no substitute for it. It is short and ugly and common. But I love it.

Know Your Audience

Still, not everybody loves initial but. The authors of «Keys for Writers» note that «some readers may raise an eyebrow when they see and or but starting a sentence in an academic paper, especially if it happens often.» So if you don’t want to see eyebrows raised, ration your use of these words at the beginnings of sentences.

But in any event, don’t start scratching out your ands and buts on our account.

It’s a question I often heard when I was teaching: Can a sentence start with but?

The answer is simple: Yes. Of course.

For years I offered $100 in cash to any student who could find the Don’t start a sentence with but rule in a grammar book from a reputable publisher. My librarian friends would invariably report a run on grammar books for the next couple of days.

Despite frantic efforts to claim the money, no student ever succeeded, for a simple reason: That “rule” doesn’t exist. Even Fowler’s Modern English Usage, the ultimate authority on grammar, says there’s no such rule. (See for yourself: Click on the link to read page 191, where you’ll find a discussion about starting sentences with but.)

Good writers start sentences with but all the time. To prove my point, a few minutes ago I found this sentence at the New York Times website in the second paragraph of a news story: “But Republicans still oppose many aspects of the bill, and a rough floor fight lies ahead.”

“Ah, yes,” you’re saying. “But that just proves how writing has deteriorated.”

I hear you. You’re sure you won’t find sentences starting with but in the Gettysburg Address, or FDR’s Inaugural Address, or Shakespeare, or the Declaration of Independence, or classic books like Pride and Prejudice and Little Women, or examples of fine prose like the King James Bible. Everybody knows that, right?

Wrong. Read on: I’ve assembled sentences starting with but from a variety of writers, old and new. For good measure, I included sentences from several authorities on good writing: Lynn Truss, Strunk and White, Theodore Bernstein, H. D. Fowler, and H. L. Mencken. (You might be interested to know that Princeton University did a study and found that professional writers start 10% of their sentences with “but” and “and.”)

But don’t take my word for it. Go to your bookcase and leaf through a couple of your favorite books. Pull out today’s newspaper and scan the front page. Turn the pages of your favorite magazine. Go to www.Bartleby.com, which has full texts of many classic books, and check out what famous writers from the past have done.

Here’s what you’ll discover: Not only do professional writers start sentences with but – they do it often. You won’t have to search far for examples. Happy hunting! (To learn more about punctuating sentences with but, click here and read about Comma Rule 2.)

Examples of Sentences Starting with But:

Eats, Shoots and Leaves, Lynn Truss, p. 7:

“But best of all, I think, is the simple advice given by the style book of a national newspaper: that punctuation is ‘a courtesy designed to help readers to understand a story without stumbling.’”

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, J. K. Rowling, p. 3:

“But on the edge of town, drills were driven out of his mind by something else.”

The Associated Press Stylebook (2007), p. 326:

“But use the comma if its omission would slow comprehension…”

Watch Your Language, Theodore Bernstein, p. 4:

“But when he is writing for the newspaper he must fit himself into the newspaper’s framework.”

Preface to Watch Your Language, Jacques Barzun:

“But I am not inviting the reader to witness a tender of compliments over what may seem like a mere byproduct of professional skill.”

The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States, H.L.Mencken (1921):

“But its chief excuse is its human interest, for it prods deeply into national idiosyncrasies and ways of mind, and that sort of prodding is always entertaining.”

The Elements of Style, Strunk and White (1918 edition):

“But whether the interruption be slight or considerable, he must never omit one comma and leave the other.”

The King’s English, H.D. Fowler (1908 edition):

“But if, instead of his Saxon percentage’s being the natural and undesigned consequence of his brevity (and the rest), those other qualities have been attained by his consciously restricting himself to Saxon, his pains will have been worse than wasted; the taint of preciosity will be over all he has written.”

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott, page 1:

“We can’t do much, but we can make our little sacrifices, and ought to do it gladly. But I’m afraid I don’t.” And Meg shook her head, as she thought regretfully of all the pretty things she wanted.

Epistle Dedicatory to Man and Superman, Bernard Shaw, 1903, p. 2:

“But you must not expect me to adopt your inexplicable, fantastic, petulant, fastidious ways….”

Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen, p. 1:

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

FDR, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1933:

“But it may be that an unprecedented demand and need for undelayed action may call for temporary departure from that normal balance of public procedure.”

The Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln (1863):

“But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground.”

Hamlet, William Shakespeare, Ii:

Horatio: So have I heard and do in part believe it.

But look, the morn, in russet mantle clad,

Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill.

King James Bible, Luke 6:44 – 45 (Sermon on the Mount)

“But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust.”

Cashel Byron’s Profession, Bernard Shaw:

CASHEL. I go. The meanest lad on thy estate Would not betray me thus. But ’tis no matter.

P.S. I have sentences starting with but in all my books (I’ve published eleven of them). Did you notice that I started a sentence with but in this blog? Here it is: But don’t take my word for it.

It’s good advice, incidentally. Start doing your own investigation of these hallowed (but non-existent) rules.

My husband once had an editor who thought because was a bad word. Whenever he used because in an article, she’d call him and insist that he take it out. It never occurred to her to check the dictionary or see whether real-world writers use the word because (which, of course, they all do regularly). Made her look foolish, didn’t it?