From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

WordPerfect, a word processor first released for minicomputers in 1979 and later ported to microcomputers, running on Windows XP

A word processor (WP)[1][2] is a device or computer program that provides for input, editing, formatting, and output of text, often with some additional features.

Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to the function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers.

The functions of a word processor program fall somewhere between those of a simple text editor and a fully functioned desktop publishing program. However, the distinctions between these three have changed over time and were unclear after 2010.[3][4]

Background[edit]

Word processors did not develop out of computer technology. Rather, they evolved from mechanical machines and only later did they merge with the computer field.[5] The history of word processing is the story of the gradual automation of the physical aspects of writing and editing, and then to the refinement of the technology to make it available to corporations and Individuals.

The term word processing appeared in American offices in early 1970s centered on the idea of streamlining the work to typists, but the meaning soon shifted toward the automation of the whole editing cycle.

At first, the designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies with emerging ones to develop stand-alone equipment, creating a new business distinct from the emerging world of the personal computer. The concept of word processing arose from the more general data processing, which since the 1950s had been the application of computers to business administration.[6]

Through history, there have been three types of word processors: mechanical, electronic and software.

Mechanical word processing[edit]

The first word processing device (a «Machine for Transcribing Letters» that appears to have been similar to a typewriter) was patented by Henry Mill for a machine that was capable of «writing so clearly and accurately you could not distinguish it from a printing press».[7] More than a century later, another patent appeared in the name of William Austin Burt for the typographer. In the late 19th century, Christopher Latham Sholes[8] created the first recognizable typewriter although it was a large size, which was described as a «literary piano».[9]

The only «word processing» these mechanical systems could perform was to change where letters appeared on the page, to fill in spaces that were previously left on the page, or to skip over lines. It was not until decades later that the introduction of electricity and electronics into typewriters began to help the writer with the mechanical part. The term “word processing” (translated from the German word Textverarbeitung) itself was created in the 1950s by Ulrich Steinhilper, a German IBM typewriter sales executive. However, it did not make its appearance in 1960s office management or computing literature (an example of grey literature), though many of the ideas, products, and technologies to which it would later be applied were already well known. Nonetheless, by 1971 the term was recognized by the New York Times[10] as a business «buzz word». Word processing paralleled the more general «data processing», or the application of computers to business administration.

Thus by 1972 discussion of word processing was common in publications devoted to business office management and technology, and by the mid-1970s the term would have been familiar to any office manager who consulted business periodicals.

Electromechanical and electronic word processing[edit]

By the late 1960s, IBM had developed the IBM MT/ST (Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter). This was a model of the IBM Selectric typewriter from the earlier part of this decade, but it came built into its own desk, integrated with magnetic tape recording and playback facilities along with controls and a bank of electrical relays. The MT/ST automated word wrap, but it had no screen. This device allowed a user to rewrite text that had been written on another tape, and it also allowed limited collaboration in the sense that a user could send the tape to another person to let them edit the document or make a copy. It was a revolution for the word processing industry. In 1969, the tapes were replaced by magnetic cards. These memory cards were inserted into an extra device that accompanied the MT/ST, able to read and record users’ work.

In the early 1970s, word processing began to slowly shift from glorified typewriters augmented with electronic features to become fully computer-based (although only with single-purpose hardware) with the development of several innovations. Just before the arrival of the personal computer (PC), IBM developed the floppy disk. In the early 1970s, the first word-processing systems appeared which allowed display and editing of documents on CRT screens.

During this era, these early stand-alone word processing systems were designed, built, and marketed by several pioneering companies. Linolex Systems was founded in 1970 by James Lincoln and Robert Oleksiak. Linolex based its technology on microprocessors, floppy drives and software. It was a computer-based system for application in the word processing businesses and it sold systems through its own sales force. With a base of installed systems in over 500 sites, Linolex Systems sold 3 million units in 1975 — a year before the Apple computer was released.[11]

At that time, the Lexitron Corporation also produced a series of dedicated word-processing microcomputers. Lexitron was the first to use a full-sized video display screen (CRT) in its models by 1978. Lexitron also used 51⁄4 inch floppy diskettes, which became the standard in the personal computer field. The program disk was inserted in one drive, and the system booted up. The data diskette was then put in the second drive. The operating system and the word processing program were combined in one file.[12]

Another of the early word processing adopters was Vydec, which created in 1973 the first modern text processor, the «Vydec Word Processing System». It had built-in multiple functions like the ability to share content by diskette and print it.[further explanation needed] The Vydec Word Processing System sold for $12,000 at the time, (about $60,000 adjusted for inflation).[13]

The Redactron Corporation (organized by Evelyn Berezin in 1969) designed and manufactured editing systems, including correcting/editing typewriters, cassette and card units, and eventually a word processor called the Data Secretary. The Burroughs Corporation acquired Redactron in 1976.[14]

A CRT-based system by Wang Laboratories became one of the most popular systems of the 1970s and early 1980s. The Wang system displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as they are known today. While early computerized word processor system were often expensive and hard to use (that is, like the computer mainframes of the 1960s), the Wang system was a true office machine, affordable to organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily mastered and operated by secretarial staff.

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (AES Data machines — re-badged), CPT, and NBI. All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with prices in the $10,000 range. Cheap general-purpose personal computers were still the domain of hobbyists.

Japanese word processor devices[edit]

In Japan, even though typewriters with Japanese writing system had widely been used for businesses and governments, they were limited to specialists who required special skills due to the wide variety of letters, until computer-based devices came onto the market. In 1977, Sharp showcased a prototype of a computer-based word processing dedicated device with Japanese writing system in Business Show in Tokyo.[15][16]

Toshiba released the first Japanese word processor JW-10 in February 1979.[17] The price was 6,300,000 JPY, equivalent to US$45,000. This is selected as one of the milestones of IEEE.[18]

Toshiba Rupo JW-P22(K)(March 1986) and an optional micro floppy disk drive unit JW-F201

The Japanese writing system uses a large number of kanji (logographic Chinese characters) which require 2 bytes to store, so having one key per each symbol is infeasible. Japanese word processing became possible with the development of the Japanese input method (a sequence of keypresses, with visual feedback, which selects a character) — now widely used in personal computers. Oki launched OKI WORD EDITOR-200 in March 1979 with this kana-based keyboard input system. In 1980 several electronics and office equipment brands entered this rapidly growing market with more compact and affordable devices. While the average unit price in 1980 was 2,000,000 JPY (US$14,300), it was dropped to 164,000 JPY (US$1,200) in 1985.[19] Even after personal computers became widely available, Japanese word processors remained popular as they tended to be more portable (an «office computer» was initially too large to carry around), and become necessities in business and academics, even for private individuals in the second half of the 1980s.[20] The phrase «word processor» has been abbreviated as «Wa-pro» or «wapuro» in Japanese.

Word processing software[edit]

The final step in word processing came with the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s and 1980s and with the subsequent creation of word processing software. Word processing software that would create much more complex and capable output was developed and prices began to fall, making them more accessible to the public. By the late 1970s, computerized word processors were still primarily used by employees composing documents for large and midsized businesses (e.g., law firms and newspapers). Within a few years, the falling prices of PCs made word processing available for the first time to all writers in the convenience of their homes.

The first word processing program for personal computers (microcomputers) was Electric Pencil, from Michael Shrayer Software, which went on sale in December 1976. In 1978 WordStar appeared and because of its many new features soon dominated the market. However, WordStar was written for the early CP/M (Control Program–Micro) operating system, and by the time it was rewritten for the newer MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), it was obsolete. Suddenly, WordPerfect dominated the word processing programs during the DOS era, while there was a large variety of less successful programs.

Early word processing software was not as intuitive as word processor devices. Most early word processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys such as «copy» or «bold». Moreover, CP/M lacked cursor keys; for example WordStar used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation. However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as “killer app” spreadsheet applications, e.g. VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software became serious competition for the dedicated machines and soon dominated the market.

Then in the late 1980s innovations such as the advent of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing (WYSIWYG — What You See Is What You Get), using bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), and graphical user interfaces such as “copy and paste” (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor). These were popularized by MacWrite on the Apple Macintosh in 1983, and Microsoft Word on the IBM PC in 1984. These were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people.

Of particular interest also is the standardization of TrueType fonts used in both Macintosh and Windows PCs. While the publishers of the operating systems provide TrueType typefaces, they are largely gathered from traditional typefaces converted by smaller font publishing houses to replicate standard fonts. Demand for new and interesting fonts, which can be found free of copyright restrictions, or commissioned from font designers, occurred.

The growing popularity of the Windows operating system in the 1990s later took Microsoft Word along with it. Originally called «Microsoft Multi-Tool Word», this program quickly became a synonym for “word processor”.

From early in the 21st century Google Docs popularized the transition to online or offline web browser based word processing, this was enabled by the widespread adoption of suitable internet connectivity in businesses and domestic households and later the popularity of smartphones. Google Docs enabled word processing from within any vendor’s web browser, which could run on any vendor’s operating system on any physical device type including tablets and smartphones, although offline editing is limited to a few Chromium based web browsers. Google Docs also enabled the significant growth of use of information technology such as remote access to files and collaborative real-time editing, both becoming simple to do with little or no need for costly software and specialist IT support.

See also[edit]

- List of word processors

- Formatted text

References[edit]

- ^ Enterprise, I. D. G. (1 January 1981). «Computerworld». IDG Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Waterhouse, Shirley A. (1 January 1979). Word processing fundamentals. Canfield Press. ISBN 9780064537223. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Amanda Presley (28 January 2010). «What Distinguishes Desktop Publishing From Word Processing?». Brighthub.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «How to Use Microsoft Word as a Desktop Publishing Tool». PCWorld. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Price, Jonathan, and Urban, Linda Pin. The Definitive Word-Processing Book. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1984, page xxiii.

- ^ W.A. Kleinschrod, «The ‘Gal Friday’ is a Typing Specialist Now,» Administrative Management vol. 32, no. 6, 1971, pp. 20-27

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. The Tech Ninja. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ See also Samuel W. Soule and Carlos Glidden.

- ^ The Scientific American, The Type Writer, New York (August 10, 1872)

- ^ W.D. Smith, “Lag Persists for Business Equipment,” New York Times, 26 Oct. 1971, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Linolex Systems, Internal Communications & Disclosure in 3M acquisition, The Petritz Collection, 1975.

- ^ «Lexitron VT1200 — RICM». Ricomputermuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (1 June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «Redactron Corporation. @ SNAC». Snaccooperative.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «日本語ワードプロセッサ». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ «【シャープ】 日本語ワープロの試作機». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ 原忠正 (1997). «日本人による日本人のためのワープロ». The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan. 117 (3): 175–178. Bibcode:1997JIEEJ.117..175.. doi:10.1541/ieejjournal.117.175.

- ^ «プレスリリース;当社の日本語ワードプロセッサが「IEEEマイルストーン」に認定». 東芝. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^

«【富士通】 OASYS 100G». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05. - ^ 情報処理学会 歴史特別委員会『日本のコンピュータ史』ISBN 4274209334 p135-136

This article is about stand-alone word processing machines. For the computer program, see Word processor program. For the general concept, see Word processor.

A word processor is an electronic device (later a computer software application) for text, composing, editing, formatting, and printing.

A Xerox 6016 Memorywriter Word Processor

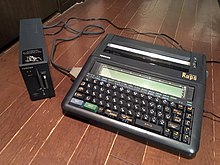

The word processor was a stand-alone office machine developed in the 1960s, combining the keyboard text-entry and printing functions of an electric typewriter with a recording unit, either tape or floppy disk (as used by the Wang machine) with a simple dedicated computer processor for the editing of text.[1] Although features and designs varied among manufacturers and models, and new features were added as technology advanced, the first word processors typically featured a monochrome display and the ability to save documents on memory cards or diskettes. Later models introduced innovations such as spell-checking programs, and improved formatting options.

As the more versatile combination of personal computers and printers became commonplace, and computer software applications for word processing became popular, most business machine companies stopped manufacturing dedicated word processor machines. As of 2009 there were only two U.S. companies, Classic and AlphaSmart, which still made them.[2][needs update] Many older machines, however, remain in use. Since 2009, Sentinel has offered a machine described as a «word processor», but it is more accurately a highly specialised microcomputer used for accounting and publishing.[3]

Word processing was one of the earliest applications for the personal computer in office productivity, and was the most widely used application on personal computers until the World Wide Web rose to prominence in the mid-1990s.

Although the early word processors evolved to use tag-based markup for document formatting, most modern word processors take advantage of a graphical user interface providing some form of what-you-see-is-what-you-get («WYSIWYG») editing. Most are powerful systems consisting of one or more programs that can produce a combination of images, graphics and text, the latter handled with type-setting capability. Typical features of a modern word processor include multiple font sets, spell checking, grammar checking, a built-in thesaurus, automatic text correction, web integration, HTML conversion, pre-formatted publication projects such as newsletters and to-do lists, and much more.

Microsoft Word is the most widely used word processing software according to a user tracking system built into the software.[citation needed] Microsoft estimates that roughly half a billion people use the Microsoft Office suite,[4] which includes Word. Many other word processing applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running Microsoft’s MS-DOS operating system, and still (2014) is favored for legal applications), Apple’s Pages application, and open source applications such as OpenOffice.org Writer, LibreOffice Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors such as Office Online or Google Docs are a relatively new category.

CharacteristicsEdit

Word processors evolved dramatically once they became software programs rather than dedicated machines. They can usefully be distinguished from text editors, the category of software they evolved from.[5][6]

A text editor is a program that is used for typing, copying, pasting, and printing text (a single character, or strings of characters). Text editors do not format lines or pages. (There are extensions of text editors which can perform formatting of lines and pages: batch document processing systems, starting with TJ-2 and RUNOFF and still available in such systems as LaTeX and Ghostscript, as well as programs that implement the paged-media extensions to HTML and CSS). Text editors are now used mainly by programmers, website designers, computer system administrators, and, in the case of LaTeX, by mathematicians and scientists (for complex formulas and for citations in rare languages). They are also useful when fast startup times, small file sizes, editing speed, and simplicity of operation are valued, and when formatting is unimportant. Due to their use in managing complex software projects, text editors can sometimes provide better facilities for managing large writing projects than a word processor.[7]

Word processing added to the text editor the ability to control type style and size, to manage lines (word wrap), to format documents into pages, and to number pages. Functions now taken for granted were added incrementally, sometimes by purchase of independent providers of add-on programs. Spell checking, grammar checking and mail merge were some of the most popular add-ons for early word processors. Word processors are also capable of hyphenation, and the management and correct positioning of footnotes and endnotes.

More advanced features found in recent word processors include:

- Collaborative editing, allowing multiple users to work on the same document.

- Indexing assistance. (True indexing, as performed by a professional human indexer, is far beyond current technology, for the same reasons that fully automated, literary-quality machine translation is.)

- Creation of tables of contents.

- Management, editing, and positioning of visual material (illustrations, diagrams), and sometimes sound files.

- Automatically managed (updated) cross-references to pages or notes.

- Version control of a document, permitting reconstruction of its evolution.

- Non-printing comments and annotations.

- Generation of document statistics (characters, words, readability level, time spent editing by each user).

- «Styles», which automate consistent formatting of text body, titles, subtitles, highlighted text, and so on.

Later desktop publishing programs were specifically designed with elaborate pre-formatted layouts for publication, offering only limited options for changing the layout, while allowing users to import text that was written using a text editor or word processor, or type the text in themselves.

Typical usageEdit

Word processors have a variety of uses and applications within the business world, home, education, journalism, publishing, and the literary arts.

Use in businessEdit

Within the business world, word processors are extremely useful tools. Some typical uses include: creating legal documents, company reports, publications for clients, letters, and internal memos. Businesses tend to have their own format and style for any of these, and additions such as company letterhead. Thus, modern word processors with layout editing and similar capabilities find widespread use in most business.

Use in homeEdit

While many homes have a word processor on their computers, word processing in the home tends to be educational, planning or business related, dealing with school assignments or work being completed at home. Occasionally word processors are used for recreational purposes, e.g. writing short stories, poems or personal correspondence. Some use word processors to create résumés and greeting cards, but many of these home publishing processes have been taken over by web apps or desktop publishing programs specifically oriented toward home uses. The rise of email and social networks has also reduced the home role of the word processor as uses that formerly required printed output can now be done entirely online.

HistoryEdit

Word processors are descended from the Friden Flexowriter, which had two punched tape stations and permitted switching from one to the other (thus enabling what was called the «chain» or «form letter», one tape containing names and addresses, and the other the body of the letter to be sent). It did not wrap words, which was begun by IBM’s Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (later, Magnetic Card Selectric Typewriter).

IBM SelectricEdit

Expensive Typewriter, written and improved between 1961 and 1962 by Steve Piner and L. Peter Deutsch, was a text editing program that ran on a DEC PDP-1 computer at MIT. Since it could drive an IBM Selectric typewriter (a letter-quality printer), it may be considered the first-word processing program, but the term word processing itself was only introduced, by IBM’s Böblingen Laboratory in the late 1960s.[citation needed]

In 1969, two software based text editing products (Astrotype and Astrocomp) were developed and marketed by Information Control Systems (Ann Arbor Michigan).[8][9][10] Both products used the Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 mini computer, DECtape (4” reel) randomly accessible tape drives, and a modified version of the IBM Selectric typewriter (the IBM 2741 Terminal). These 1969 products preceded CRT display-based word processors. Text editing was done using a line numbering system viewed on a paper copy inserted in the Selectric typewriter.

Evelyn Berezin invented a Selectric-based word processor in 1969, and founded the Redactron Corporation to market the $8,000 machine.[11] Redactron was sold to Burroughs Corporation in 1976, where the Redactron-II and -III were sold both as standalone units and as peripherals to the company’s mainframe computers.[12]

By 1971 word processing was recognized by the New York Times as a «buzz word».[13] A 1974 Times article referred to «the brave new world of Word Processing or W/P. That’s International Business Machines talk … I.B.M. introduced W/P about five years ago for its Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter and other electronic razzle-dazzle.»[14]

IBM defined the term in a broad and vague way as «the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications,» and originally used it to include dictating machines and ordinary, manually operated Selectric typewriters.[15] By the early seventies, however, the term was generally understood to mean semiautomated typewriters affording at least some form of editing and correction, and the ability to produce perfect «originals». Thus, the Times headlined a 1974 Xerox product as a «speedier electronic typewriter», but went on to describe the product, which had no screen,[16] as «a word processor rather than strictly a typewriter, in that it stores copy on magnetic tape or magnetic cards for retyping, corrections, and subsequent printout».[17]

Mainframe systemsEdit

In the late 1960s IBM provided a program called FORMAT for generating printed documents on any computer capable of running Fortran IV. Written by Gerald M. Berns, FORMAT was described in his paper «Description of FORMAT, a Text-Processing Program» (Communications of the ACM, Volume 12, Number 3, March, 1969) as «a production program which facilitates the editing and printing of ‘finished’ documents directly on the printer of a relatively small (64k) computer system. It features good performance, totally free-form input, very flexible formatting capabilities including up to eight columns per page, automatic capitalization, aids for index construction, and a minimum of nontext [control elements] items.» Input was normally on punched cards or magnetic tape, with up to 80capital letters and non-alphabetic characters per card. The limited typographical controls available were implemented by control sequences; for example, letters were automatically converted to lower case unless they followed a full stop, that is, the «period» character. Output could be printed on a typical line printer in all-capitals — or in upper and lower case using a special («TN») printer chain — or could be punched as a paper tape which could be printed, in better than line printer quality, on a Flexowriter. A workalike program with some improvements, DORMAT, was developed and used at University College London.[citation needed]

Electromechanical paper-tape-based equipment such as the Friden Flexowriter had long been available; the Flexowriter allowed for operations such as repetitive typing of form letters (with a pause for the operator to manually type in the variable information),[18] and when equipped with an auxiliary reader, could perform an early version of «mail merge». Circa 1970 it began to be feasible to apply electronic computers to office automation tasks. IBM’s Mag Tape Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST) and later Mag Card Selectric (MCST) were early devices of this kind, which allowed editing, simple revision, and repetitive typing, with a one-line display for editing single lines.[19] The first novel to be written on a word processor, the IBM MT/ST, was Len Deighton’s Bomber, published in 1970.[20]

Effect on office administrationEdit

The New York Times, reporting on a 1971 business equipment trade show, said

- The «buzz word» for this year’s show was «word processing», or the use of electronic equipment, such as typewriters; procedures and trained personnel to maximize office efficiency. At the IBM exhibition a girl typed on an electronic typewriter. The copy was received on a magnetic tape cassette which accepted corrections, deletions, and additions and then produced a perfect letter for the boss’s signature …[13]

In 1971, a third of all working women in the United States were secretaries, and they could see that word processing would affect their careers. Some manufacturers, according to a Times article, urged that «the concept of ‘word processing’ could be the answer to Women’s Lib advocates’ prayers. Word processing will replace the ‘traditional’ secretary and give women new administrative roles in business and industry.»[13]

The 1970s word processing concept did not refer merely to equipment, but, explicitly, to the use of equipment for «breaking down secretarial labor into distinct components, with some staff members handling typing exclusively while others supply administrative support. A typical operation would leave most executives without private secretaries. Instead one secretary would perform various administrative tasks for three or more secretaries.»[21] A 1971 article said that «Some [secretaries] see W/P as a career ladder into management; others see it as a dead-end into the automated ghetto; others predict it will lead straight to the picket line.» The National Secretaries Association, which defined secretaries as people who «can assume responsibility without direct supervision», feared that W/P would transform secretaries into «space-age typing pools». The article considered only the organizational changes resulting from secretaries operating word processors rather than typewriters; the possibility that word processors might result in managers creating documents without the intervention of secretaries was not considered—not surprising in an era when few managers, but most secretaries, possessed keyboarding skills.[14]

Dedicated modelsEdit

In 1972, Stephen Bernard Dorsey, Founder and President of Canadian company Automatic Electronic Systems (AES), introduced the world’s first programmable word processor with a video screen. The real breakthrough by Dorsey’s AES team was that their machine stored the operator’s texts on magnetic disks. Texts could be retrieved from the disks simply by entering their names at the keyboard. More importantly, a text could be edited, for instance a paragraph moved to a new place, or a spelling error corrected, and these changes were recorded on the magnetic disk.

The AES machine was actually a sophisticated computer that could be reprogrammed by changing the instructions contained within a few chips.[22][23]

In 1975, Dorsey started Micom Data Systems and introduced the Micom 2000 word processor. The Micom 2000 improved on the AES design by using the Intel 8080 single-chip microprocessor, which made the word processor smaller, less costly to build and supported multiple languages.[24]

Around this time, DeltaData and Wang word processors also appeared, again with a video screen and a magnetic storage disk.

The competitive edge for Dorsey’s Micom 2000 was that, unlike many other machines, it was truly programmable. The Micom machine countered the problem of obsolescence by avoiding the limitations of a hard-wired system of program storage. The Micom 2000 utilized RAM, which was mass-produced and totally programmable.[25] The Micom 2000 was said to be a year ahead of its time when it was introduced into a marketplace that represented some pretty serious competition such as IBM, Xerox and Wang Laboratories.[26]

In 1978, Micom partnered with Dutch multinational Philips and Dorsey grew Micom’s sales position to number three among major word processor manufacturers, behind only IBM and Wang.[27]

Software modelsEdit

In the early 1970s, computer scientist Harold Koplow was hired by Wang Laboratories to program calculators. One of his programs permitted a Wang calculator to interface with an IBM Selectric typewriter, which was at the time used to calculate and print the paperwork for auto sales.

In 1974, Koplow’s interface program was developed into the Wang 1200 Word Processor, an IBM Selectric-based text-storage device. The operator of this machine typed text on a conventional IBM Selectric; when the Return key was pressed, the line of text was stored on a cassette tape. One cassette held roughly 20 pages of text, and could be «played back» (i.e., the text retrieved) by printing the contents on continuous-form paper in the 1200 typewriter’s «print» mode. The stored text could also be edited, using keys on a simple, six-key array. Basic editing functions included Insert, Delete, Skip (character, line), and so on.

The labor and cost savings of this device were immediate, and remarkable: pages of text no longer had to be retyped to correct simple errors, and projects could be worked on, stored, and then retrieved for use later on. The rudimentary Wang 1200 machine was the precursor of the Wang Office Information System (OIS), introduced in 1976. It was a true office machine, affordable by organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily learned and operated by secretarial staff.

The Wang was not the first CRT-based machine nor were all of its innovations unique to Wang. In the early 1970s Linolex, Lexitron and Vydec introduced pioneering word-processing systems with CRT display editing. A Canadian electronics company, Automatic Electronic Systems, had introduced a product in 1972, but went into receivership a year later. In 1976, refinanced by the Canada Development Corporation, it returned to operation as AES Data, and went on to successfully market its brand of word processors worldwide until its demise in the mid-1980s. Its first office product, the AES-90,[28] combined for the first time a CRT-screen, a floppy-disk and a microprocessor,[22][23] that is, the very same winning combination that would be used by IBM for its PC seven years later.[citation needed] The AES-90 software was able to handle French and English typing from the start, displaying and printing the texts side-by-side, a Canadian government requirement. The first eight units were delivered to the office of the then Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, in February 1974.[citation needed]

Despite these predecessors, Wang’s product was a standout, and by 1978 it had sold more of these systems than any other vendor.[29]

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to the AES 90. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (marketing AES Data machines, re-badged), CPT, and NBI.[30]

All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, priced around $10,000. Cheap general-purpose computers were still for hobbyists.

Some of the earliest CRT-based machines used cassette tapes for removable-memory storage until floppy diskettes became available for this purpose — first the 8-inch floppy, then the 5¼-inch (drives by Shugart Associates and diskettes by Dysan).

Printing of documents was initially accomplished using IBM Selectric typewriters modified for ASCII-character input. These were later replaced by application-specific daisy wheel printers, first developed by Diablo, which became a Xerox company, and later by Qume. For quicker «draft» printing, dot-matrix line printers were optional alternatives with some word processors.

WYSIWYG modelsEdit

Examples of standalone word processor typefaces c. 1980–1981

Brother WP-1400D editing electronic typewriter (1994)

Electric Pencil, released in December 1976, was the first word processor software for microcomputers.[31][32][33][34][35] Software-based word processors running on general-purpose personal computers gradually displaced dedicated word processors, and the term came to refer to software rather than hardware. Some programs were modeled after particular dedicated WP hardware. MultiMate, for example, was written for an insurance company that had hundreds of typists using Wang systems, and spread from there to other Wang customers. To adapt to the smaller, more generic PC keyboard, MultiMate used stick-on labels and a large plastic clip-on template to remind users of its dozens of Wang-like functions, using the shift, alt and ctrl keys with the 10 IBM function keys and many of the alphabet keys.

Other early word-processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled «copy» or «bold». (In fact, many early PCs lacked cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software soon became serious competition for the dedicated machines. Word processing became the most popular use for personal computers, and unlike the spreadsheet (dominated by Lotus 1-2-3) and database (dBase) markets, WordPerfect, XyWrite, Microsoft Word, pfs:Write, and dozens of other word processing software brands competed in the 1980s; PC Magazine reviewed 57 different programs in one January 1986 issue.[32] Development of higher-resolution monitors allowed them to provide limited WYSIWYG—What You See Is What You Get, to the extent that typographical features like bold and italics, indentation, justification and margins were approximated on screen.

The mid-to-late 1980s saw the spread of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing, and of true WYSIWYG bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), PostScript, and graphical user interfaces (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor which was commercialised in the Xerox Star product range). Standalone word processors adapted by getting smaller and replacing their CRTs with small character-oriented LCD displays. Some models also had computer-like features such as floppy disk drives and the ability to output to an external printer. They also got a name change, now being called «electronic typewriters» and typically occupying a lower end of the market, selling for under US$200.

During the late 1980s and into the 1990s the predominant word processing program was WordPerfect.[36] It had more than 50% of the worldwide market as late as 1995, but by 2000 Microsoft Word had up to 95% market share.[37]

MacWrite, Microsoft Word, and other word processing programs for the bit-mapped Apple Macintosh screen, introduced in 1984, were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people until the introduction of Microsoft Windows. Dedicated word processors eventually became museum pieces.

See alsoEdit

- Amstrad PCW

- Authoring systems

- Canon Cat

- Comparison of word processors

- Content management system

- CPT Word Processors

- Document collaboration

- List of word processors

- IBM MT/ST

- Microwriter

- Office suite

- TeX

- Typography

LiteratureEdit

- Matthew G. Kirschenbaum Track Changes — A Literary History of Word Processing Harvard University Press 2016 ISBN 9780674417076

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «TECHNOWRITERS» Popular Mechanics, June 1989, pp. 71-73.

- ^ Mark Newhall, Farm Show

- ^ StarLux Illumination catalog

- ^ «Microsoft Office Is Right at Home». Microsoft. January 8, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ «InfoWorld Jan 1 1990». January 1990.

- ^ Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781573565219.

- ^ UNIX Text Processing, O’Reilly.

Nonetheless, the text editors used in program development environments can provide much better facilities for managing large writing projects than their office word-processing counterparts.

- ^ «Information Control Systems Inc. (ICS) | Ann Arbor District Library».

- ^ «Secretaries Get a Computer of their Own to Automate Typing» (PDF). Computers and Automation. January 1969. p. 59. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ «Computer Aided Typists Produce Perfect Copies». Computer World. November 13, 1968. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Pozzi, Sandro (12 December 2018). «Muere Evelyn Berezin, creadora del primer procesador digital de textos» [Evelyn Berezin dies, creator of the first digital text processor]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

Berezin diseñó el primer sistema central de reservas de United Airlines cuando trabajaba para Teleregister y otro similar para gestionar la contabilidad de la banca a nivel nacional. En 1968 empezó a trabajar en la idea de un ordenador que procesara textos, utilizando pequeños circuitos integrados. Al año decidió dejar la empresa para crear la suya propia, que llamó Redactron Corporation.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (2018-12-10). «Evelyn Berezin, 93, Dies; Built the First True Word Processor». The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ a b c Smith, William D. (October 26, 1971). «Lag Persists for Business Equipment». The New York Times. p. 59.

- ^ a b Dullea, Georgia (February 5, 1974). «Is It a Boon for Secretaries—Or Just an Automated Ghetto?». The New York Times. p. 32.

- ^ «IBM Adds to Line of Dictation Items». The New York Times. September 12, 1972. p. 72. reports introduction of «five new models of ‘input word processing equipment’, better known in the past as dictation equipment» and gives IBM’s definition of WP as «the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications». The machines described were of course ordinary dictation machines recording onto magnetic belts, not voice typewriters.

- ^ Miller, Diane Fisher (1997) «My Life with the Machine»: «By Sunday afternoon, I urgently want to throw the Xerox 800 through the window, then run over it with the company van. It seems that the instructor forgot to tell me a few things about doing multi-page documents … To do any serious editing, I must use both tape drives, and, without a display, I must visualize and mentally track what is going onto the tapes.»

- ^ Smith, William D. (October 8, 1974). «Xerox Is Introducing a Speedier Electric Typewriter». The New York Times. p. 57.

- ^ O’Kane, Lawrence (May 22, 1966). «Computer a Help to ‘Friendly Doc’; Automated Letter Writer Can Dispense a Cheery Word». The New York Times. p. 348.

Automated cordiality will be one of the services offered to physicians and dentists who take space in a new medical center…. The typist will insert the homey touch in the appropriate place as the Friden automated, programmed «Flexowriter» rattles off the form letters requesting payment… or informing that the X-ray’s of the patient (kidney) (arm) (stomach) (chest) came out negative.

- ^ Rostky, Georgy (2000). «The word processor: cumbersome, but great». EETimes. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- ^ Kirschenbaum, Matthew (March 1, 2013). «The Book-Writing Machine: What was the first novel ever written on a word processor?». Slate. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Smith, William D. (December 16, 1974). «Electric Typewriter Sales Are Bolstered by Efficiency». The New York Times. p. 57.

- ^ a b Thomas, David (1983). Knights of the New Technology. Toronto: Key Porter Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-919493-16-5.

- ^ a b CBC Television, Venture, «AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale» Broadcast date February 4, 1985, minute 3:50.

- ^ Thomas, David «Knights of the New Technology». Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 97 & p. 98.

- ^ “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, pp. 8 & 9.

- ^ “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Thomas, David «Knights of the New Technology». Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 102 & p. 103.

- ^ «1970–1979 C.E.: Media History Project». University of Minnesota. May 18, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ Schuyten, Peter J. (1978): «Wang Labs: Healthy Survivor» The New York Times December 6, 1978 p. D1: «[Market research analyst] Amy Wohl… said… ‘Since then, the company has installed more of these systems than any other vendor in the business.»

- ^ «NBI INC Securities Registration, Form SB-2, Filing Date Sep 8, 1998». secdatabase.com. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Pea, Roy D. and D. Midian Kurland (1987). «Cognitive Technologies for Writing». Review of Research in Education. 14: 277–326. JSTOR 1167314.

- ^ a b Bergin, Thomas J. (Oct–Dec 2006). «The Origins of Word Processing Software for Personal Computers: 1976–1985». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (4): 32–47. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.76. S2CID 18895790.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul (1982-05-10). «Electric Pencil, first micro word processor». InfoWorld. p. 12. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

- ^ Shrayer, Michael (November 1984). «Confessions of a naked programmer». Creative Computing. p. 130. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel [in Spanish] (1992). «Word Processing (History of)». Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science (PDF). Vol. 49. New York: Dekker. pp. 268–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2019.

- ^ Brinkley, Joel (2000-09-21). «It’s a Word World, Or Is It?». The New York Times.

External linksEdit

- FOSS word processors compared: OOo Writer, AbiWord, and KWord by Bruce Byfield

- History of Word Processing

- «Remembering the Office of the Future: Word Processing and Office Automation before the Personal Computer» — A comprehensive history of early word processing concepts, hardware, software, and use. By Thomas Haigh, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 28:4 (October–December 2006):6-31.

- «A Brief History of Word Processing (Through 1986)» by Brian Kunde (December, 1986)

- «AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale» by CBC Television (Broadcast date: February 4, 1985, link updated Nov. 2, 2012)

A

word processor (more formally known as document preparation system)

is a computer application used for the production (including

composition, editing, formatting, and possibly printing) of any sort

of printable material.

Word

processor may also refer to a type of stand-alone office machine,

popular in the 1970s and 1980s, combining the keyboard text-entry and

printing functions of an electric typewriter with a dedicated

processor (like a computer processor) for the editing of text.

Although features and design varied between manufacturers and models,

with new features added as technology advanced, word processors for

several years usually featured a monochrome display and the ability

to save documents on memory cards or diskettes. Later models

introduced innovations such as spell-checking programs, increased

formatting options, and dot-matrix printing. As the more versatile

combination of a personal computer and separate printer became

commonplace, most business-machine companies stopped manufacturing

the word processor as a stand-alone office machine. As of 2009 there

were only two U.S. companies, Classic and AlphaSmart, which still

made stand-alone word processors.[1] Many older machines, however,

remain in use.

Word

processors are descended from early text formatting tools (sometimes

called text justification tools, from their only real capability).

Word processing was one of the earliest applications for the personal

computer in office productivity.

Although

early word processors used tag-based markup for document formatting,

most modern word processors take advantage of a graphical user

interface providing some form of What You See Is What You Get

editing. Most are powerful systems consisting of one or more programs

that can produce any arbitrary combination of images, graphics and

text, the latter handled with type-setting capability.

Microsoft

Word is the most widely used word processing software. Microsoft

estimates that over 500,000,000 people use the Microsoft Office

suite,[2] which includes Word. Many other word processing

applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market

from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running Microsoft’s

MS-DOS operating system) and open source applications OpenOffice.org

Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors, such as

Google Docs, are a relatively new category.

Word processing

Characteristics

Word

processing typically implies the presence of text manipulation

functions that extend beyond a basic ability to enter and change

text, such as automatic generation of:

• batch

mailings using a form letter template and an address database (also

called mail merging);

• indices

of keywords and their page numbers;

• tables

of contents with section titles and their page numbers;

• tables

of figures with caption titles and their page numbers;

• cross-referencing

with section or page numbers;

• footnote

numbering;

• new

versions of a document using variables (e.g. model numbers, product

names, etc.)

Other

word processing functions include «spell checking»

(actually checks against wordlists), «grammar checking»

(checks for what seem to be simple grammar errors), and a «thesaurus»

function (finds words with similar or opposite meanings). Other

common features include collaborative editing, comments and

annotations, support for images and diagrams and internal

cross-referencing.

Word

processors can be distinguished from several other, related forms of

software:

Text

editors (modern examples of which include Notepad, BBEdit, Kate,

Gedit), were the precursors of word processors. While offering

facilities for composing and editing text, they do not format

documents. This can be done by batch document processing systems,

starting with TJ-2 and RUNOFF and still available in such systems as

LaTeX (as well as programs that implement the paged-media extensions

to HTML and CSS). Text editors are now used mainly by programmers,

website designers, computer system administrators, and, in the case

of LaTeX by mathematicians and scientists (for complex formulas and

for citations in rare languages). They are also useful when fast

startup times, small file sizes, editing speed and simplicity of

operation are preferred over formatting.

Later

desktop publishing programs were specifically designed to allow

elaborate layout for publication, but often offered only limited

support for editing. Typically, desktop publishing programs allowed

users to import text that was written using a text editor or word

processor.

Almost

all word processors enable users to employ styles, which are used to

automate consistent formatting of text body, titles, subtitles,

highlighted text, and so on.

Styles

greatly simplify managing the formatting of large documents, since

changing a style automatically changes all text that the style has

been applied to. Even in shorter documents styles can save a lot of

time while formatting. However, most help files refer to styles as an

‘advanced feature’ of the word processor, which often discourages

users from using styles regularly.

Document

statistics

Most

current word processors can calculate various statistics pertaining

to a document. These usually include:

• Character

count, word count, sentence count, line count, paragraph count, page

count.

• Word,

sentence and paragraph length.

• Editing

time.

Errors

are common; for instance, a dash surrounded by spaces — like either

of these — may be counted as a word.

Typical

usage

Word

processors have a variety of uses and applications within the

business world, home, and education.

Business

Within

the business world, word processors are extremely useful tools.

Typical uses include:

• legal

copies

• letters

and letterhead

• memos

• reference

documents

Businesses

tend to have their own format and style for any of these. Thus,

versatile word processors with layout editing and similar

capabilities find widespread use in most businesses.

Education

Many

schools have begun to teach typing and word processing to their

students, starting as early as elementary school. Typically these

skills are developed throughout secondary school in preparation for

the business world. Undergraduate students typically spend many hours

writing essays. Graduate and doctoral students continue this trend,

as well as creating works for research and publication.

Home

While

many homes have word processors on their computers, word processing

in the home tends to be educational, planning or business related,

dealing with assignments or work being completed at home, or

occasionally recreational, e.g. writing short stories. Some use word

processors for letter writing, résumé creation, and card creation.

However, many of these home publishing processes have been taken over

by desktop publishing programs specifically oriented toward home use.

which are better suited to these types of documents.

History

Toshiba

JW-10, the first word processor for the Japanese language (1971-1978

IEEE milestones)

Examples

of standalone word processor typefaces c. 1980-1981

Brother

WP-1400D editing electronic typewriter (1994)

The

term word processing was invented by IBM in the late 1960s. By 1971

it was recognized by the New York Times as a «buzz word».[3]

A 1974 Times article referred to «the brave new world of Word

Processing or W/P. That’s International Business Machines talk…

I.B.M. introduced W/P about five years ago for its Magnetic Tape

Selectric Typewriter and other electronic razzle-dazzle.»

IBM

defined the term in a broad and vague way as «the combination of

people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed

communications,» and originally used it to include dictating

machines and ordinary, manually-operated Selectric typewriters. By

the early seventies, however, the term was generally understood to

mean semiautomated typewriters affording at least some form of

electronic editing and correction, and the ability to produce perfect

«originals.» Thus, the Times headlined a 1974 Xerox product

as a «speedier electronic typewriter», but went on to

describe the product, which had no screen, as «a word processor

rather than strictly a typewriter, in that it stores copy on magnetic

tape or magnetic cards for retyping, corrections, and subsequent

printout.»

Electromechanical

paper-tape-based equipment such as the Friden Flexowriter had long

been available; the Flexowriter allowed for operations such as

repetitive typing of form letters (with a pause for the operator to

manually type in the variable information)[8], and when equipped with

an auxiliary reader, could perform an early version of «mail

merge». Circa 1970 it began to be feasible to apply electronic

computers to office automation tasks. IBM’s Mag Tape Selectric

Typewriter (MTST) and later Mag Card Selectric (MCST) were early

devices of this kind, which allowed editing, simple revision, and

repetitive typing, with a one-line display for editing single lines.

The

New York Times, reporting on a 1971 business equipment trade show,

said

The

«buzz word» for this year’s show was «word

processing,» or the use of electronic equipment, such as

typewriters; procedures and trained personnel to maximize office

efficiency. At the IBM exhibition a girl [sic] typed on an electronic

typewriter. The copy was received on a magnetic tape cassette which

accepted corrections, deletions, and additions and then produced a

perfect letter for the boss’s signature….

In

1971, a third of all working women in the United States were

secretaries, and they could see that word processing would have an

impact on their careers. Some manufacturers, according to a Times

article, urged that «the concept of ‘word processing’ could be

the answer to Women’s Lib advocates’ prayers. Word processing will

replace the ‘traditional’ secretary and give women new administrative

roles in business and industry.»

The

1970s word processing concept did not refer merely to equipment, but,

explicitly, to the use of equipment for «breaking down

secretarial labor into distinct components, with some staff members

handling typing exclusively while others supply administrative

support. A typical operation would leave most executives without

private secretaries. Instead one secretary would perform various

administrative tasks for three or more secretaries.» A 1971

article said that «Some [secretaries] see W/P as a career ladder

into management; others see it as a dead-end into the automated

ghetto; others predict it will lead straight to the picket line.»

The National Secretaries Association, which defined secretaries as

people who «can assume responsibility without direct

supervision,» feared that W/P would transform secretaries into

«space-age typing pools.» The article considered only the

organizational changes resulting from secretaries operating word

processors rather than typewriters; the possibility that word

processors might result in managers creating documents without the

intervention of secretaries was not considered—not surprising in an

era when few but secretaries possessed keyboarding skills.

In

the early 1970s, computer scientist Harold Koplow was hired by Wang

Laboratories to program calculators. One of his programs permitted a

Wang calculator to interface with an IBM Selectric typewriter, which

was at the time used to calculate and print the paperwork for auto

sales.

In

1974, Koplow’s interface program was developed into the Wang 1200

Word Processor, an IBM Selectric-based text-storage device. The

operator of this machine typed text on a conventional IBM Selectric;

when the Return key was pressed, the line of text was stored on a

cassette tape. One cassette held roughly 20 pages of text, and could

be «played back» (i.e., the text retrieved) by printing the

contents on continuous-form paper in the 1200 typewriter’s «print»

mode. The stored text could also be edited, using keys on a simple,

six-key array. Basic editing functions included Insert, Delete, Skip

(character, line), and so on.

The

labor and cost savings of this device were immediate, and remarkable:

pages of text no longer had to be retyped to correct simple errors,

and projects could be worked on, stored, and then retrieved for use

later on. The rudimentary Wang 1200 machine was the precursor of the

Wang Office Information System (OIS), introduced in 1976, whose

CRT-based system was a major breakthrough in word processing

technology. It displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated

virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as we

know them today. It was a true office machine, affordable by

organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily learned and

operated by secretarial staff.

The

Wang was not the first CRT-based machine nor were all of its

innovations unique to Wang. In the early 1970s Linolex, Lexitron and

Vydec introduced pioneering word-processing systems with CRT display

editing. A Canadian electronics company, Automatic Electronic

Systems, had introduced a product with similarities to Wang’s product

in 1973, but went into bankruptcy a year later. In 1976, refinanced

by the Canada Development Corporation, it returned to operation as

AES Data, and went on to successfully market its brand of word

processors worldwide until its demise in the mid-1980s. Its first

office product, the AES-90, combined for the first time a CRT-screen,

a floppy-disk and a microprocessor,[citation needed] that is, the

very same winning combination that would be used by IBM for its PC

seven years later. The AES-90 software was able to handle French and

English typing from the start, displaying and printing the texts

side-by-side, a Canadian government requirement. The first eight

units were delivered to the office of the then Prime Minister, Pierre

Elliot Trudeau, in February 1974. Despite these predecessors, Wang’s

product was a standout, and by 1978 it had sold more of these systems

than any other vendor.

In

the early 1980’s, AES Data Inc. introduced a networked word processor

system, called MULTIPLUS, offering multi-tasking and up to 8

workstations all sharing the resources of a centralized computer

system, a precursor to today’s networks. It followed with the

introduction of SuperPlus and SuperPlus IV systems which also offered

the CP/M operating system answering client needs. AES Data word

processors were placed side-by-side with CP/M software, like

Wordstar, to highlight ease of use.

The

phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based

machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged,

typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as

IBM, Lanier (marketing AES Data machines, re-badged), CPT, and

NBI.[13] All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with

prices in the $10,000 ballpark. Cheap general-purpose computers were

still the domain of hobbyists.

Some

of the earliest CRT-based machines used cassette tapes for

removable-memory storage until floppy diskettes became available for

this purpose — first the 8-inch floppy, then the 5-1/4-inch (drives

by Shugart Associates and diskettes by Dysan).

Printing

of documents was initially accomplished using IBM Selectric

typewriters modified for ASCII-character input. These were later

replaced by application-specific daisy wheel printers (Diablo, which

became a Xerox company, and Qume — both now defunct.) For quicker

«draft» printing, dot-matrix line printers were optional

alternatives with some word processors.

With

the rise of personal computers, and in particular the IBM PC and PC

compatibles, software-based word processors running on

general-purpose commodity hardware gradually displaced dedicated word

processors, and the term came to refer to software rather than

hardware. Some programs were modeled after particular dedicated WP

hardware. MultiMate, for example, was written for an insurance

company that had hundreds of typists using Wang systems, and spread

from there to other Wang customers. To adapt to the smaller PC

keyboard, MultiMate used stick-on labels and a large plastic clip-on

template to remind users of its dozens of Wang-like functions, using

the shift, alt and ctrl keys with the 10 IBM function keys and many

of the alphabet keys.

Other

early word-processing software required users to memorize

semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled

«copy» or «bold.» (In fact, many early PCs lacked

cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond»

for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of

hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between

dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value

added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling

that personal computers and word processing software soon became

serious competition for the dedicated machines. Word Perfect,

XyWrite, Microsoft Word, Wordstar, Workwriter and dozens of other

word processing software brands competed in the 1980s. Development of

higher-resolution monitors allowed them to provide limited WYSIWYG —

What You See Is What You Get, to the extent that typographical

features like bold and italics, indentation, justification and

margins were approximated on screen.

The

mid-to-late 1980s saw the spread of laser printers, a «typographic»

approach to word processing, and of true WYSIWYG bitmap displays with

multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word

processing program), PostScript, and graphical user interfaces

(another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor which

was commercialised in the Xerox Star product range). Standalone word

processors adapted by getting smaller and replacing their CRTs with

small character-oriented LCD displays. Some models also had

computer-like features such as floppy disk drives and the ability to

output to an external printer. They also got a name change, now being

called «electronic typewriters» and typically occupying a

lower end of the market, selling for under $200 USD.

MacWrite,

Microsoft Word and other word processing programs for the bit-mapped

Apple Macintosh screen, introduced in 1984, were probably the first

true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people until the

introduction of Microsoft Windows. Dedicated

word processors eventually became museum pieces.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Word_processor

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Goals

- Students will recognize the major types of word processing programs.

- Students will discriminate the types of problems that are best solved

with various types of word processors. - Students will recognize the major tools that are available in word

processor application programs. - Students will use a text editor to create and modify a simple ASCII

text file. - Students will use a high end word processing program to practice

common text formatting problems.

Prereqs

- Comfort with the keyboard and mouse

- Experience with the STAIR process for solving problems

- Familiarity with principles of data encoding

- Familiarity with differences between hardware and software

- Understanding of the attributes of RAM

- Familiarity with operating systems, file names and directories

Discussion

Word processing is one of the most common applications for computers

today. It would be difficult to spend a day in a modern office or

university without coming into contact with a word processing program.

Most people have had some contact with word processing. We shall

examine the concept in some detail, so you will be familiar with a

number of levels of word processing software applications, the types

of tools such programs make available to you, and so you will know

what kinds of problems are best solved with this type of program.

How Word Processors Work

The advantages of word processing programs can best be illustrated by

thinking of some of the disadvantages of typewriters. When we use a

typewriter to create a document, there is a direct connection between

the keys and the paper. As soon as you press a key on the keyboard,

there is an impact on the paper, and the document has been modified.

If you catch a mistake quickly, you can fix it with correction tape or

white-out. If your mistake is more than one character long, it is

much harder to fix. If you want to add a word, move a

paragraph, or change the margins, you have to completely retype the

page. Sometimes this necessitates changes on other pages as well. A

one word change could lead to retyping an entire document.

Word processing is a type of software that focuses on the ability to

handle text. The computer does this by assigning each letter of the

alphabet and each other character on the keyboard a specific numeric

code. These numeric codes are translated into computer machine language,

and stored in the computer’s memory. Because the information is in memory,

it is very easy to change and manipulate. This is the key to the

success of word processing.

Example

Information in memory can be moved very quickly and easily. If we

want to change a word in a document, what happens in the computer is

something like this:

Imagine Darlene has started out her resume with the following word:

REUME

Obviously she has forgotten a letter. If she were using a typewriter,

the page would be trashed, and she would have to start over. Since

this is a word processor, Darlene can manipulate the memory containing

codes for the word «REUME» and add the «S» to it. When she tries, the

following things happen:

She moves her cursor to the spot in the text where she wants the S to

show up. The «cursor» is a special mark on the screen that indicates

at which place in the document the computer is currently focused. In this

case, Darlene wants to put an S between the E and the U. Her word

processor won’t let her put the cursor between two letters (although

some will), so she puts it on the U.

By moving the cursor, Darlene is telling the program to move around in

memory as well. When she place her cursor on the U on the screen, she

is telling the program to point to the corresponding spot in the

computer’s memory. The computer is now concentrating on the memory

cell that contains the code for the character «U».

She checks to be sure she is in insert mode (more on that later),

and she types the letter «S».

When Darlene does this, the computer shifts all the letters one memory

cell to the right, and inserts the code for the S in its proper

place.

Word processors and RAM

It sounds like a lot is happening. That’s true, but computers do all

these things so quickly that it seems instantaneous to us. You don’t

really have to know exactly where the stuff is in memory, or how it

gets moved around. The important thing to understand is that all the

information in your document is stored in some kind of digital

format in the computer’s memory. When you modify a document, you are really

modifying the computer’s memory. A word processing program handles

all the messy memory manipulation, so all you have to do is concentrate

on writing your paper.

RAM (Random Access Memory), where all the action is happening, has

one serious drawback. It only lasts as long as the computer is receiving

electrical power. Obviously this will cause some problems, because you

can’t just carry a computer around to show people your documents.

(Imagine the extension cord!) You also might run into some serious

problems if your computer were suddenly hit by a monsoon or something,

and you lost electrical power. In short, you cannot count on RAM memory

alone.

Word processing programs (as well as almost every type of program) are

designed to allow you to copy your information. Computer scientists

refer to the information your program is using as data. The data in

RAM can easily be duplicated to floppy disks or a hard drive. This is

called saving. Copying the data from RAM to a printer is called

printing. You can also copy data from other places to RAM. Copying the data

from the disk is referred to as loading the data. You might already

know what saving and printing are. We don’t mean to insult you by

telling you again. We just want to illustrate that it all boils down

to copying binary information to and from RAM.

Types of Word Processing Programs

There are many flavors of word processing programs. Different

programs are better for different types of jobs. One common problem

is deciding which program you will use to do a certain type of job.

It is important to know your options.

Text Editors

The simplest programs that do word processing are known as text

editors. These programs are designed to be small, simple, and cheap.

Almost every operating system made has at least one built in text

editor. Most text editors save files in a special format called

ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange — Whew!)

ASCII is a coding convention that almost all computers understand.

Each letter is assigned a numeric value that will fit in eight digits

of binary notation. «a» is 97 in ASCII, and «A» is 65. All the

numeric digits, and most punctuation marks also have numeric values in

ASCII. You certainly don’t need to memorize all the codes, (That’s

the text editor’s job.) but you should recognize the word « ASCII».

The biggest advantage of this scheme is that almost any program

can read and write ASCII text.

Text editors can be wonderful programs. The biggest advantage is the

price. There is probably already one or more installed on your

computer. You can find a number of text editors for free on the

Internet. Text editors are generally very easy to learn. Since they don’t

do a lot of fancy things, they are generally less intimidating than

full fledged word processor packages with all kinds of features.

Finally, text editors are pretty universal. Since they almost all use

the ASCII standard, you can read a text file written on any text

editor with just about any text editor. This is often not the case

when using fancier programs.

The ability to write ASCII text is the biggest benefit of text

editors. ASCII is also the biggest disadvantage of most text editors.

It is a very good way of storing text information, but it has no way

of handling more involved formatting. Text editors generally do not

allow you to do things like change font sizes or styles, spell

checking, or columns. (If you don’t know what those things are, stay

tuned. We will talk about them later in this chapter.)

Text editors aren’t all simple, though. Text editors are actually the

workhorses of the computing world. Most computer programs and web

pages are written with specialized text editors, and these programs

can be quite involved. You won’t need to learn any hard-core text editors

for this class, but you may end up learning one down the road.

If all you want to do is get text written, and you aren’t too

concerned about how fancy it looks, text editors are fine. (In fact,

this book was written entirely in emacs, a unix-based text editor.)

Common text editor programs:

- Windows: Notepad

- Macintosh: SimpleText

- Linux: vi, emacs

- Multi-platform: notepad++, jedit, synedit, many more

Integrated Packages

Frequently these software packages are included when a person buys a

new computer system. An integrated package is a huge program that

contains a word processor, a spreadsheet, a database tool, and other

software applications in the same program. (Don’t worry if you don’t

know what a spreadsheet or a database is. We’ll get there soon

enough!) An integrated application package is kind of like a «Swiss

army knife» of software.

The advantages of an integrated package derive from the fact that all

the applications are part of the same program, and were written by the

same company. It should be relatively easy to use the parts of an

integrated package together. These programs tend to be smaller, older

versions of larger programs, so they might be less complicated to use.

Since they were presumably written together, they should all have the

same general menu structure, and similar commands. (The command to

save a file would be the same set of keystrokes in all the programs,

for example.) Integrated packages are often designed with casual

users in mind. This might make them easier to use than more robust

programs. The word processor built into an integrated package is

probably more powerful than a typical text editor. Integrated

packages are often already installed on new computers, so they might

not cost you any more than the original purchase price of the