Subject + verb + interrogative adverb / pronoun + clause

Study the following sentences.

- I know where he lives.

- He asked when he should come.

- I wonder why he is late today.

- She explained how it could be done.

- I know what I should do now.

Notes

Note the word order in the clause introduced by the interrogative adverb / pronoun. As you can see, the subject comes before the verb. In typical questions, the verb comes before the subject. But when a question word clause becomes the object of a verb, it has the same word order as an affirmative clause.

- Incorrect: I don’t know what does she want.

- Correct: I don’t know what she wants.

- Incorrect: I know how should it be done.

- Correct: I know how it should be done.

Subject + verb + noun / pronoun + questions word clause

- They asked me what I was doing there.

- He told us when we should start.

- The teacher showed us how it could be done.

- Tell me where I should go. (Here the subject you is not mentioned, but it is understood.)

- I told him why it could not be done.

These three structures are a common part of English, and are all composed of groups of words. Clauses, phrases and sentences are very similar, but they do have different roles. Learning the difference between them will help you make a lot more sense of English grammar, and will be very useful to improve your written English.

What is a phrase?

Words can be grouped together, but without a subject or a verb. This is called a phrase.

Because a phrase has neither subject nor verb, it can’t form a ‘predicate’. This is a structure that must contain a verb, and it tells you something about what the subject is doing.

Phrases can be very short – or quite long. Two examples of phrases are:

“After dinner”

“Waiting for the rain to stop”.

Phrases can’t be used alone, but you can use them as part of a sentence, where they are used as parts of speech.

What is a clause?

Clauses are groups of words that have both subjects and predicates. Unlike phrases, a clause can sometimes act as a sentence – this type of clause is called an independent clause. This isn’t always the case, and some clauses can’t be used on their own – these are called subordinate clauses, and need to be used with an independent clause to complete their meaning.

An example of a subordinate clause is “When the man broke into the house”

An example of an independent clause is “the dog barked at him”

While the independent clause could be used by itself as a complete sentence, the subordinate clause could not. For it to be correct, it would need to be paired with another clause: “When the man broke into the house, the dog barked at him.”

What is a sentence?

A complete sentence has a subject and predicate, and can often be composed of more than one clause. As long as it has a subject and a predicate, a group of words can form a sentence, no matter how short.

E.g. “You ate fish.”

More complex sentences can combine multiple clauses or phrases to add additional information about what is described. Clauses may be combined using conjunctions – such as “and”, “but” and “or”.

E.g. “He went out to dinner but didn’t enjoy the meal.”

This example is composed of two independent clauses, “he went out to dinner” and “he didn’t enjoy the meal”, combined with a conjunction- “but”.

Your turn

While clauses, phrases and sentences might seem very similar at first, on closer look you can start to see how they function very differently. To make sure you use them correctly, it’s important to practice identifying them.

Try reading different materials, and spotting the phrases, clauses and complete sentences in a piece of text. Then try to write your own examples of them! And if you would like to learn English with people from all over the world — check out our range of language courses abroad at Eurocentres.com

English word order is strict and rather inflexible. As there are few endings in English that show person, number, case and tense, English relies on word order to show relationships between words in a sentence.

In Russian, we rely on word endings to tell us how words interact in a sentence. You probably remember the example that was made up by Academician L.V. Scherba in order to show the work of endings and suffixes in Russian. (No English translation for this example.) Everything we need to know about the interaction of the characters in this Russian sentence, we learn from the endings and suffixes.

English nouns do not have any case endings (only personal pronouns have some case endings), so it is mostly the word order that tells us where things are in a sentence, and how they interact. Compare:

The dog sees the cat.

The cat sees the dog.

The subject and the object in these sentences are completely the same in form. How do you know who sees whom? The rules of English word order tell us about it.

Word order patterns in English sentences

A sentence is a group of words containing a subject and a predicate and expressing a complete thought. Word order arranges separate words into sentences in a certain way and indicates where to find the subject, the predicate, and the other parts of the sentence. Word order and context help to identify the meanings of individual words.

English sentences are divided into declarative sentences (statements), interrogative sentences (questions), imperative sentences (commands, requests), and exclamatory sentences. Declarative sentences are the most common type of sentences. Word order in declarative sentences serves as a basis for word order in the other types of sentences.

The main minimal pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE. Examples: Maria works. Time flies.

The most common pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE + OBJECT, often called SUBJECT + VERB + OBJECT (SVO) in English linguistic sources. Examples: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

An ordinary declarative sentence containing all five parts of the sentence, for example, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», has the following word order:

The subject is placed at the beginning of the sentence before the predicate; the predicate follows the subject; the object is placed after the predicate; the adverbial modifier is placed after the object (or after the verb if there is no object); the attribute (an adjective) is placed before its noun (attributes in the form of a noun with a preposition are placed after their nouns).

Verb type and word order

Word order after the verb usually depends on the type of verb (transitive verb, intransitive verb, linking verb). (Types of verbs are described in Verbs Glossary of Terms in the section Grammar.)

Transitive verbs

Transitive verbs require a direct object: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (See Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the section Miscellany.)

Some transitive verbs (e.g., bring, give, send, show, tell) are often followed by two objects: an indirect object and a direct object. For example: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Such sentences often have the following word order: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Intransitive verbs

Intransitive verbs do not take a direct object. Intransitive verbs may stand alone or may be followed by an adverbial modifier (an adverb, a phrase) or by a prepositional object.

Examples of sentences with intransitive verbs: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Linking verbs

Linking verbs (e.g., be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) are followed by a complement. The verb BE is the main linking verb. It is often followed by a noun or an adjective: He is a doctor. He is kind. (See The Verb BE in the section Grammar.)

Other linking verbs are usually followed by an adjective (the linking verb «become» may also be followed by a noun): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

The material below describes standard word order in different types of sentences very briefly. The other materials of the section Word Order give a more detailed description of standard word order and its peculiarities in different types of sentences.

Declarative sentences

Subject + predicate (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Maria works.

Tom is a writer.

This book is interesting.

I live in Moscow.

Tom writes short stories for children.

He talked to Anna yesterday.

My son bought three history books.

He is writing a report now.

(See Word Order in Statements in the section Grammar.)

Interrogative sentences

Interrogative sentences include general questions, special questions, alternative questions, and tag questions. (See Word Order in Questions in the section Grammar.)

General questions

Auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Do you live here? – Yes, I do.

Does he speak English? – Yes, he does.

Did you go to the concert? – No, I didn’t.

Is he writing a report now? – Yes, he is.

Have you seen this film? – No, I haven’t.

Special questions

Question word + auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Where does he live? – He lives in Paris.

What are you writing now? – I’m writing a new story.

When did they visit Mexico? – They visited Mexico five years ago.

What is your name? – My name is Alex.

How old are you? – I’m 24 years old.

Alternative questions

Alternative questions are questions with a choice. Word order before «or» is the same as in general questions.

Is he a teacher or a doctor? – He is a teacher.

Does he live in Paris or in Rome? – He lives in Rome.

Are you writing a report or a letter? – I’m writing a report.

Would you like coffee or tea? – Tea, please.

Tag questions

Tag questions consist of two parts. The first part has the same word order as statements; the second part is a short general question (the tag).

He is a teacher, isn’t he? – Yes, he is.

He lives here, doesn’t he? – No, he doesn’t.

You went there, didn’t you? – Yes, I did.

They haven’t seen this film, have they? – No, they haven’t.

Imperative sentences

Imperative sentences (commands, instructions, requests) have the same word order as statements, but the subject (you) is usually omitted. (See Word Order in Commands in the section Grammar.)

Go to your room.

Listen to the story.

Please sit down.

Give me that book, please.

Negative imperative sentences are formed with the help of the auxiliary verb «don’t».

Don’t cry.

Don’t wait for me.

Requests

Polite requests in English are usually in the form of general questions using «could, may, will, would». (See Word Order in Requests in the section Grammar.)

Could you help me, please?

May I speak to Tom, please?

Will you please ask him to call me?

Would you mind helping me with this report?

Exclamatory sentences

Exclamatory sentences have the same word order as statements (i.e., the subject is before the predicate).

She is a great singer!

It is an excellent opportunity!

How well he knows history!

What a beautiful town this is!

How strange it is!

In some types of exclamatory sentences, the subject (it, this, that) and the linking verb are often omitted.

What a pity!

What a beautiful present!

What beautiful flowers!

How strange!

Simple, compound, and complex sentences

English sentences are divided into simple sentences, compound sentences and complex sentences depending on the number and kind of clauses that they contain.

The term «clause»

The word «clause» is translated into Russian in the same way as the word «sentence». The word «clause» refers to a group of words containing a subject and a predicate, usually in a compound or complex sentence.

There are two kinds of clauses: independent and dependent. An independent clause can be a separate sentence (e.g., a simple sentence).

The main clause in a complex sentence and clauses in a compound sentence are independent clauses; the subordinate clause is a dependent clause.

Simple sentences

A simple sentence consists of one independent clause, has a subject and a predicate and may also have other parts of the sentence (an object, an adverbial modifier, an attribute).

Life goes on.

I’m busy.

Anton is sleeping.

She works in a hotel.

You don’t know him.

He wrote a letter to the manager.

Compound sentences

A compound sentence consists of two (or more) independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, or). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

Maria lives in Moscow, and her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

He wrote a letter to the manager, but the manager didn’t answer.

Her children may watch TV here, or they may play in the yard.

Sentences connected by «and» may be connected without a conjunction. In such cases, a semicolon is used between them.

Maria lives in Moscow; her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

Complex sentences

A complex sentence consists of the main clause and the subordinate clause connected by a subordinating conjunction (e.g., that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

I told him that I didn’t know anything about their plans.

Betty has been working as a secretary since she moved to California.

Tom went to bed early because he was very tired.

If he comes back before ten, ask him to call me, please.

(Different types of subordinate clauses are described in Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar.)

Базовый порядок слов

Порядок слов в английском языке строгий и довольно негибкий. Так как в английском языке мало окончаний, показывающих лицо, число, падеж и время, английский язык полагается на порядок слов для показа отношений между словами в предложении.

В русском языке мы полагаемся на окончания, чтобы понять, как слова взаимодействуют в предложении. Вы, наверное, помните пример, который придумал академик Л.В. Щерба для того, чтобы показать работу окончаний и суффиксов в русском языке: Глокая куздра штеко будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. (Нет английского перевода для этого примера.) Все, что нам нужно знать о взаимодействии героев в этом русском предложении, мы узнаём из окончаний и суффиксов.

Английские существительные не имеют падежных окончаний (только личные местоимения имеют падежные окончания), поэтому в основном именно порядок слов сообщает нам, где что находится в предложении и как они взаимодействуют. Сравните:

Собака видит кошку.

Кошка видит собаку.

Подлежащее и дополнение в этих (английских) предложениях полностью одинаковы по форме. Как узнать, кто кого видит? Правила английского порядка слов говорят нам об этом.

Модели порядка слов в английских предложениях

Предложение – это группа слов, содержащая подлежащее и сказуемое и выражающая законченную мысль. Порядок слов организует отдельные слова в предложения определённым образом и указывает, где найти подлежащее, сказуемое и другие члены предложения. Порядок слов и контекст помогают выявить значения отдельных слов.

Английские предложения делятся на повествовательные предложения (утверждения), вопросительные предложения (вопросы), повелительные предложения (команды, просьбы) и восклицательные предложения. Повествовательные предложения – самый распространённый тип предложений. Порядок слов в повествовательных предложениях служит основой для порядка слов в других типах предложений.

Основная минимальная модель базового порядка слов в английских повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое. Примеры: Maria works. Time flies.

Наиболее распространённая модель базового порядка слов в повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое + дополнение, часто называемая подлежащее + глагол + дополнение в английских лингвистических источниках. Примеры: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

Обычное повествовательное предложение, содержащее все пять членов предложения, например, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», имеет следующий порядок слов:

Подлежащее ставится в начале предложения перед сказуемым; сказуемое следует за подлежащим; дополнение ставится после сказуемого; обстоятельство ставится после дополнения (или после глагола, если дополнения нет); определение (прилагательное) ставится перед своим существительным (определения в виде существительного с предлогом ставятся после своих существительных).

Тип глагола и порядок слов

Порядок слов после глагола обычно зависит от типа глагола (переходный глагол, непереходный глагол, глагол-связка). (Типы глаголов описываются в материале «Verbs Glossary of Terms» в разделе Grammar.)

Переходные глаголы

Переходные глаголы требуют прямого дополнения: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (См. Transitive and Intransitive Verbs в разделе Miscellany.)

За некоторыми переходными глаголами (например, bring, give, send, show, tell) часто следуют два дополнения: косвенное дополнение и прямое дополнение. Например: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Такие предложения часто имеют следующий порядок слов: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Непереходные глаголы

Непереходные глаголы не принимают прямое дополнение. За непереходными глаголами может ничего не стоять, или за ними может следовать обстоятельство (наречие, фраза) или предложное дополнение.

Примеры предложений с непереходными глаголами: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Глаголы-связки

За глаголами-связками (например, be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) следует комплемент (именная часть сказуемого). Глагол BE – главный глагол-связка. За ним часто следует существительное или прилагательное: He is a doctor. He is kind. (См. The Verb BE в разделе Grammar.)

За другими глаголами-связками обычно следует прилагательное (за глаголом-связкой «become» может также следовать существительное): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

Материал ниже описывает стандартный порядок слов в различных типах предложений очень кратко. Другие материалы раздела Word Order дают более подробное описание стандартного порядка слов и его особенностей в различных типах предложений.

Повествовательные предложения

Подлежащее + сказуемое (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Мария работает.

Том – писатель.

Эта книга интересная.

Я живу в Москве.

Том пишет короткие рассказы для детей.

Он говорил с Анной вчера.

Мой сын купил три книги по истории.

Он пишет доклад сейчас.

(См. Word Order in Statements в разделе Grammar.)

Вопросительные предложения

Вопросительные предложения включают в себя общие вопросы, специальные вопросы, альтернативные вопросы и разъединённые вопросы. (См. Word Order in Questions в разделе Grammar.)

Общие вопросы

Вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Вы живёте здесь? – Да (живу).

Он говорит по-английски? – Да (говорит).

Вы ходили на концерт? – Нет (не ходил).

Он пишет доклад сейчас? – Да (пишет).

Вы видели этот фильм? – Нет (не видел).

Специальные вопросы

Вопросительное слово + вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Где он живёт? – Он живёт в Париже.

Что вы сейчас пишете? – Я пишу новый рассказ.

Когда они посетили Мексику? – Они посетили Мексику пять лет назад.

Как вас зовут? – Меня зовут Алекс.

Сколько вам лет? – Мне 24 года.

Альтернативные вопросы

Альтернативные вопросы – это вопросы с выбором. Порядок слов до «or» такой же, как в общих вопросах.

Он учитель или врач? – Он учитель.

Он живёт в Париже или в Риме? – Он живёт в Риме.

Вы пишете доклад или письмо? – Я пишу доклад.

Хотите кофе или чай? – Чай, пожалуйста.

Разъединенные вопросы

Разъединённые вопросы состоят из двух частей. Первая часть имеет такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения; вторая часть – краткий общий вопрос.

Он учитель, не так ли? – Да (он учитель).

Он живёт здесь, не так ли? – Нет (не живёт).

Вы ходили туда, не так ли? – Да (ходил).

Они не видели этот фильм, не так ли? – Нет (не видели).

Повелительные предложения

Повелительные предложения (команды, инструкции, просьбы) имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения, но подлежащее (вы) обычно опускается. (См. Word Order in Commands в разделе Grammar.)

Идите в свою комнату.

Слушайте рассказ.

Пожалуйста, садитесь.

Дайте мне ту книгу, пожалуйста.

Отрицательные повелительные предложения образуются с помощью вспомогательного глагола «don’t».

Не плачь.

Не ждите меня.

Просьбы

Вежливые просьбы в английском языке обычно в форме вопросов с использованием «could, may, will, would». (См. Word Order in Requests в разделе Grammar.)

Не могли бы вы помочь мне, пожалуйста?

Можно мне поговорить с Томом, пожалуйста?

Попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

Вы не возражали бы помочь мне с этим докладом?

Восклицательные предложения

Восклицательные предложения имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения (т.е. подлежащее перед сказуемым).

Она отличная певица!

Это отличная возможность!

Как хорошо он знает историю!

Какой это прекрасный город!

Как это странно!

В некоторых типах восклицательных предложений подлежащее (it, this, that) и глагол-связка часто опускаются.

Какая жалость!

Какой прекрасный подарок!

Какие прекрасные цветы!

Как странно!

Простые, сложносочиненные и сложноподчиненные предложения

Английские предложения делятся на простые предложения, сложносочинённые предложения и сложноподчинённые предложения в зависимости от количества и вида предложений, которые они содержат.

Термин «clause»

Слово «clause» переводится на русский язык так же, как слово «sentence». Слово «clause» имеет в виду группу слов, содержащую подлежащее и сказуемое, обычно в сложносочинённом или сложноподчинённом предложении.

Есть два вида «clauses»: независимые и зависимые. Независимое предложение может быть отдельным предложением (например, простое предложение).

Главное предложение в сложноподчинённом предложении и предложения в сложносочинённом предложении – независимые предложения; придаточное предложение – зависимое предложение.

Простые предложения

Простое предложение состоит из одного независимого предложения, имеет подлежащее и сказуемое и может также иметь другие члены предложения (дополнение, обстоятельство, определение).

Жизнь продолжается.

Я занят.

Антон спит.

Она работает в гостинице.

Вы не знаете его.

Он написал письмо менеджеру.

Сложносочиненные предложения

Сложносочинённое предложение состоит из двух (или более) независимых предложений, соединённых соединительным союзом (например, and, but, or). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Мария живёт в Москве, а её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Он написал письмо менеджеру, но менеджер не ответил.

Её дети могут посмотреть телевизор здесь, или они могут поиграть во дворе.

Предложения, соединённые союзом «and», могут быть соединены без союза. В таких случаях между ними ставится точка с запятой.

Мария живёт в Москве; её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Сложноподчиненные предложения

Сложноподчинённое предложение состоит из главного предложения и придаточного предложения, соединённых подчинительным союзом (например, that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Я сказал ему, что я ничего не знаю об их планах.

Бетти работает секретарём с тех пор, как она переехала в Калифорнию.

Том лёг спать рано, потому что он очень устал.

Если он вернётся до десяти, попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

(Различные типы придаточных предложений описываются в материале «Word Order in Complex Sentences» в разделе Grammar.)

1. What is a Clause?

A clause is a set of words containing a subject and a predicate. Every full sentence has at least one clause—it is not possible to have a complete sentence without one. Sometimes, a clause is only two words, but it can be more. Because of this, it is the shortest way you can express a complete thought in English!

It’s easy to remember what a clause is—just use this simple “word equation”:

CLAUSE = SUBJECT + PREDICATE

2. Examples of Clauses

In the examples, subjects are purple and predicates are green. As mentioned, some clauses are only two words, a subject and a single verb predicate, like these:

- I see.

- He ran.

- We ate.

- They sang.

Other times, instead of a single verb, a predicate can be a verb phrase, so a clause can be longer, like these:

- I see you.

- He ran away.

- We ate popcorn.

- They sang beautifully.

3. Parts of a Clause

All clauses have two main things, a subject and a predicate.

a. Subject

A subject is the person, place, idea, or thing that a sentence is about. It’s the noun that is “doing” something in the sentence. Every sentence needs at least one to make sense. Sometimes a subject is only one word, but sometimes it includes modifiers, or can be a noun phrase or gerund.

b. Predicate

A predicate contains a sentence’s action—it tells what the subject does, and always needs a verb. Often the predicate is just a verb, but it can also be a verb phrase: a verb plus its objects or modifiers. Here are three examples of different types of predicates in clause:

- The dog ran. Single verb “ran” = predicate

- The dog ran quickly. Verb + modifier “ran quickly” = predicate

- The dog ran home. Verb + object “ran home” = predicate

4. Types of Clauses

There are two main types of clauses that we use in sentences. They are called independent clauses and dependent (or subordinate) clauses, and each works differently in a sentence and on its own.

a. Independent Clause

An independent clause is a clause that is as a complete sentence. Basically, it’s just a simple sentence. Like all clauses, it has a subject and a predicate, and makes sense on its own.

- The dog ate popcorn.

- He ate popcorn.

- The dog ate.

- He ate at the fair.

You can see that each sentence above is complete; you don’t need to add any other words for it to express a complete thought.

b. Dependent (Subordinate) Clause

A dependent clause has a subject and a predicate; BUT, unlike an independent clause, it can’t exist as a sentence. It doesn’t make sense on its own because it doesn’t share a complete thought. A dependent clause only gives extra information, and is “dependent” on other words to make a full sentence. Here are a few examples:

- After he went to the fair What did he do after?

- Since he ate popcorn Since he ate popcorn, what?

- While he was at the county fair What happened?

- If the dog eats popcorn Then what?

Though all of the examples above contain subjects and clauses, none of them make sense on their own. So, dependent clauses are very important, but they need independent clauses to make a full sentence, which make complex sentences. Alone, a dependent clause makes a fragment sentence (see Section V).

Furthermore, there are several types of dependent clauses, like noun clauses, adjective (relative) clauses, and adverb clauses. In the sentences below, the clauses are underlined.

i. Noun Clause

A noun clause is a group of words that acts as a noun in a sentence. They begin with relative pronouns like “how,” “which,” “who,” or “what,” combined with a subject and predicate. For example:

The dog can eat what he wants.

Here, “what he wants” stands as a noun for what the dog can eat. It’s a clause because it has a subject (he) and a predicate (wants).

ii. Adjective (Relative) Clause

Adjective clauses are groups of words that act as an adjective in a sentence. They have a pronoun (who, that, which) or an adverb (what, where, why) and a verb; or, a pronoun or an adverb that serves as subject and a verb. Here are some examples:

The dog will eat whichever flavor of popcorn you have

Whichever (pronoun) + flavor (subject) + have (verb) is an adjective clause that describes the popcorn. As you can see, it’s not a full sentence.

The dog is the one who ate the popcorn.

“Who” (pronoun acting as subject) + “ate” (verb) is an adjective clause that describes the dog.

iii. Adverb Clause

An adverb clause is a group of words that work as an adverb in a sentence, answering questions asking “where?”, “when,” “how?” and “why?” They begin with a subordinate conjunction.

The dog ran until he got to the county fair.

This sentence answers the question “how long did the dog run?” with the adverb clause “until he got to the county fair.”

After the dog arrived he ate popcorn.

With the adverb clause “after the dog arrived,” this sentence answers, “when did the dog eat popcorn?”

REMEMBER: NO TYPE OF DEPENDENT CLAUSE CAN BE A SENTENCE BY ITSELF!

5. How to Avoid Mistakes

There are a couple of common mistakes that can happen when using clauses. First, you need to remember rules about subject-verb agreement. Second, it’s important to avoid fragment sentences. And of course, always remember: CLAUSE = SUBJECT + PREDICATE!

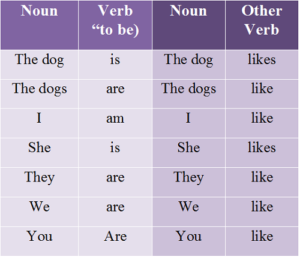

a. Subject-Verb Agreement

Each sentence has a subject and a verb, but as you know, subjects and verbs both have singular and plural forms. In order for them to function properly, they need to “agree” with each other, or match, which is called subject-verb agreement (SVA). Clauses rely on subject-verb agreement to make sense. Look at these two sentences:

The dog likes popcorn. Correct SVA

The dog like popcorn. Incorrect SVA

The dogs like popcorn. Correct SVA

The dogs likes popcorn. Incorrect SVA

Now, here are some key rules to remember:

- Singular subjects need singular verbs

- Plural subjects need plural verbs

- A mix of singular and plural results in subject-verb disagreement.

- Sometimes single and plural verbs are the same

You probably already know the difference between singular nouns and verbs and plural nouns and verbs. Here’s a chart to help you remember some:

b. Fragment Sentence

A “fragment” is a small piece of something. So, a fragment sentence is just a piece of a sentence: it is missing a subject, a predicate, or an independent clause. It’s simply an incomplete sentence. As mentioned, using a dependent clause on its own makes a fragment sentence because it doesn’t express a complete thought.

Let’s use the dependent clauses from above:

- After he went to the fair What did he do after?

- Since he ate popcorn Since he ate popcorn, what?

- While he was at the county fair What happened?

- If he eats popcorn Then what?

As you can see, each leaves an unanswered question. So, let’s complete the sentences them:

- The dog was tired after he went to the fair.

- Since he ate popcorn, the dog didn’t want dinner.

- While he was at the county fair, the dog ate popcorn.

- The dog will get a stomachache if he eats popcorn.

Here, the independent clauses are underlined. In each of the sentences above, the dependent clause is paired with an independent clause to make it complete. So, always remember: a dependent clause needs an independent clause!

What is a Clause

A clause is comprised of a group of words that include a subject and a finite verb. It contains only one subject and one verb. The subject of a clause can be mentioned or hidden, but the verb must be apparent and distinguishable.

A clause is “a group of words containing a subject and predicate and functioning as a member of a complex or compound sentence. ” – Merriam-Webster

Example:

- I graduated last year. (One clause sentence)

- When I came here, I saw him. (Two clause sentence)

- When I came here, I saw him, and he greeted me. (Three clause sentence)

Types of Clauses

- Independent Clause

- Dependent Clause

- Adjective Clause

- Noun Clause

- Adverbial Clause

- Principal Clause

- Coordinate Clause

- Non-finite Clause

Independent Clause

It functions on its own to make a meaningful sentence and looks much like a regular sentence.

In a sentence two independent clauses can be connected by the coordinators: and, but, so, or, nor, for*, yet*.

Example:

- He is a wise man.

- I like him.

- Can you do it?

- Do it please. (Subject you is hidden)

- I read the whole story.

- I want to buy a phone, but I don’t have enough money. (Two independent clauses)

- He went to London and visited the Lords. (Subject of the second clause is ‘he,’ so “he visited the Lords” is an independent clause.)

- Alex smiles whenever he sees her. (One independent clause)

Dependent Clause

It cannot function on its own because it leaves an idea or thought unfinished. It is also called a subordinate clause. These help the independent clauses complete the sentence. Alone, it cannot form a complete sentence.

The subordinators do the work of connecting the dependent clause to another clause to complete the sentence. In each of the dependent clauses, the first word is a subordinator. Subordinators include relative pronouns, subordinating conjunctions, and noun clause markers.

Example:

- When I was dating Daina, I had an accident.

- I know the man who stole the watch.

- He bought a car which was too expensive.

- I know that he cannot do it.

- He does not know where he was born.

- If you don’t eat, I won’t go.

- He is a very talented player though he is out of form.

Dependent Clauses are divided into three types and they are –

1. Adjective Clause

It is a Dependent Clause that modifies a Noun. Basically, Adjective Clauses have similar qualities as Adjectives that are of modifying Nouns and hence the name, Adjective Clause. These are also called Relative Clauses and they usually sit right after the Nouns they modify.

Examples:

- I’m looking for the red book that went missing last week.

- Finn is asking for the shoes which used to belong to his dad.

- You there, who is sitting quietly at the corner, come here and lead the class out.

2. Noun Clause

Dependent Clauses acting as Nouns in sentences are called Noun Clauses or Nominal Clauses. These often start with “how,” “that,” other WH-words (What, Who, Where, When, Why, Which, Whose and Whom), if, whether etc.

Examples:

- I like what I hear.

- You need to express that it’s crossing a line for you.

- He knows how things work around here.

3. Adverbial Clause

By definition, these are Dependent Clauses acting as Adverbs. It means that these clauses have the power to modify Verbs, Adjectives and other Adverbs.

Examples:

- Alice did the dishes till her legs gave up.

- Tina ran to the point of panting vehemently.

- I went through the book at a lightning speed.

Principal Clause

These have a Subject (Noun/Pronoun), Finite Verb and an Object and make full sentences that can stand alone or act as the main part of any Complex or Compound Sentence. Independent and Principal Clauses are functionally the same but named from different perspectives.

Examples:

- I know that boy.

- He can jog every morning.

- Robin fishes like a pro.

Coordinate Clause

Two or more similarly important Independent Clauses joined by Coordinating Conjunctions (and, or, but etc.) in terms of Compound Sentences are called Coordinate Clauses.

Examples:

- I like taking photos and he loves posing for them.

- You prefer flying but she always wants to take a bus.

- We are going to visit Terry or he is coming over.

Non-finite Clause

They contain a Participle or an Infinitive Verb that makes the Subject and Verb evident even though hidden. In terms of a Participle, the Participial Phrase takes place of the Subject or Object of the sentence.

Examples:

- He saw the boy (who was) staring out of the window.

- She is the first person (who is) to enter the office.

- Hearing the fireworks, the children jumped up.