Most modern English speakers encounter «thou» predominantly in the works of Shakespeare; in the works of other renaissance, medieval and early modern writers; and in the King James Bible.[1][2]

The word thou () is a second-person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in most contexts by the word you, although it remains in use in parts of Northern England and in Scots (/ðu/). Thou is the nominative form; the oblique/objective form is thee (functioning as both accusative and dative); the possessive is thy (adjective) or thine (as an adjective before a vowel or as a possessive pronoun); and the reflexive is thyself. When thou is the grammatical subject of a finite verb in the indicative mood, the verb form typically ends in -(e)st (e.g. «thou goest», «thou do(e)st»), but in some cases just -t (e.g., «thou art»; «thou shalt»).

Originally, thou was simply the singular counterpart to the plural pronoun ye, derived from an ancient Indo-European root. In Middle English, thou was sometimes represented with a scribal abbreviation that put a small «u» over the letter thorn: þͧ (later, in printing presses that lacked this letter, this abbreviation was sometimes rendered as yͧ). Starting in the 1300s, thou and thee were used to express familiarity, formality, or contempt, for addressing strangers, superiors, or inferiors, or in situations when indicating singularity to avoid confusion was needed; concurrently, the plural forms, ye and you began to also be used for singular: typically for addressing rulers, superiors, equals, inferiors, parents, younger persons, and significant others.[3] In the 17th century, thou fell into disuse in the standard language, often regarded as impolite, but persisted, sometimes in an altered form, in regional dialects of England and Scotland,[4] as well as in the language of such religious groups as the Society of Friends. The use of the pronoun is also still present in Christian prayer and in poetry.[5]

Early English translations of the Bible used the familiar singular form of the second person, which mirrors common usage trends in other languages. The familiar and singular form is used when speaking to God in French (in Protestantism both in past and present, in Catholicism since the post–Vatican II reforms), German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Scottish Gaelic and many others (all of which maintain the use of an «informal» singular form of the second person in modern speech). In addition, the translators of the King James Version of the Bible attempted to maintain the distinction found in Biblical Hebrew, Aramaic and Koine Greek between singular and plural second-person pronouns and verb forms, so they used thou, thee, thy, and thine for singular, and ye, you, your, and yours for plural.

In standard modern English, thou continues to be used in formal religious contexts, in wedding ceremonies, in literature that seeks to reproduce archaic language, and in certain fixed phrases such as «fare thee well». For this reason, many associate the pronoun with solemnity or formality. Many dialects have compensated for the lack of a singular/plural distinction caused by the disappearance of thou and ye through the creation of new plural pronouns or pronominals, such as yinz, yous[6] and y’all or the colloquial you guys. Ye remains common in some parts of Ireland, but the examples just given vary regionally and are usually restricted to colloquial speech.

Grammar[edit]

Because thou has passed out of common use, its traditional forms are often confused by those imitating archaic speech.[7][citation needed]

Declension[edit]

The English personal pronouns have standardized declension according to the following table:[citation needed]

| Nominative | Oblique | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | I | me | my/mine[# 1] | mine |

| plural | we | us | our | ours | |

| 2nd person | singular informal | thou | thee | thy/thine[# 1] | thine |

| singular formal | ye, you | you | your | yours | |

| plural | |||||

| 3rd person | singular | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/his (it)[# 2] | his/hers/his[# 2] |

| plural | they | them | their | theirs |

- ^ a b The genitives my, mine, thy, and thine are used as possessive adjectives before a noun, or as possessive pronouns without a noun. All four forms are used as possessive adjectives: mine and thine are used before nouns beginning in a vowel sound, or before nouns beginning in the letter h, which was usually silent (e.g. thine eyes and mine heart, which was pronounced as mine art) and my and thy before consonants (thy mother, my love). However, only mine and thine are used as possessive pronouns, as in it is thine and they were mine (not *they were my).

- ^ a b From the early Early Modern English period up until the 17th century, his was the possessive of the third-person neuter it as well as of the third-person masculine he. Genitive «it» appears once in the 1611 King James Bible (Leviticus 25:5) as groweth of it owne accord.

Conjugation[edit]

Verb forms used after thou generally end in -est (pronounced /-ᵻst/) or -st in the indicative mood in both the present and the past tenses. These forms are used for both strong and weak verbs.

Typical examples of the standard present and past tense forms follow. The e in the ending is optional; early English spelling had not yet been standardized. In verse, the choice about whether to use the e often depended upon considerations of meter.

- to know: thou knowest, thou knewest

- to drive: thou drivest, thou drovest

- to make: thou makest, thou madest

- to love: thou lovest, thou lovedst

- to want: thou wantest, thou wantedst

Modal verbs also have -(e)st added to their forms:

- can: thou canst

- could: thou couldst

- may: thou mayest

- might: thou mightst

- should: thou shouldst

- would: thou wouldst

- ought to: thou oughtest to

A few verbs have irregular thou forms:

- to be: thou art (or thou beest), thou wast (or thou wert; originally thou were)

- to have: thou hast, thou hadst

- to do: thou dost (or thou doest in non-auxiliary use) and thou didst

- shall: thou shalt

- will: thou wilt

A few others are not inflected:

- must: thou must

In Proto-English[clarification needed], the second-person singular verb inflection was -es. This came down unchanged[citation needed] from Indo-European and can be seen in quite distantly related Indo-European languages: Russian знаешь, znayesh, thou knowest; Latin amas, thou lovest. (This is parallel to the history of the third-person form, in Old English -eþ, Russian, знает, znayet, he knoweth, Latin amat he loveth.) The anomalous development[according to whom?] from -es to modern English -est, which took place separately at around the same time in the closely related German and West Frisian languages, is understood to be caused by an assimilation of the consonant of the pronoun, which often followed the verb. This is most readily observed in German: liebes du → liebstu → liebst du (lovest thou).[8]

Comparison[edit]

| Early Modern English | Modern West Frisian | Modern German | Modern Dutch | Modern English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thou hast | Do hast [dou ˈhast] |

Du hast [duː ˈhast] |

Jij hebt [jɛɪ ˈɦɛpt] |

You have |

| She hath | Sy hat [sɛi ˈhat] |

Sie hat [ziː ˈhat] |

Zij heeft [zɛɪ ˈɦeft] |

She has |

| What hast thou? | Wat hasto? [vat ˈhasto] |

Was hast du? [vas ˈhast duː] |

Wat heb je? [ʋɑt ˈɦɛp jə] |

What do you have? (What have you?) |

| What hath she? | Wat hat sy? [vat ˈhat sɛi] |

Was hat sie? [vas ˈhat ziː] |

Wat heeft zij? [ʋɑt ˈɦeft zɛɪ] |

What does she have? (What has she?) |

| Thou goest | Do giest [dou ˈɡiəst] |

Du gehst [duː ˈɡeːst] |

Jij gaat [jɛɪ ˈxat] |

You go |

| Thou doest | Do dochst [dou ˈdoχst] |

Du tust [duː ˈtuːst] |

Jij doet [jɛɪ ˈdut] |

You do |

| Thou art (variant thou beest) |

Do bist [dou ˈbɪst] |

Du bist [duː ˈbɪst] |

Jij bent [jɛɪ ˈbɛnt] |

You are |

In Dutch, the equivalent of «thou», du, also became archaic and fell out of use and was replaced by the Dutch equivalent of «you», gij (later jij or u), just as it has in English, with the place of the informal plural taken by jullie (compare English y’all).

In the subjunctive and imperative moods, the ending in -(e)st is dropped (although it is generally retained in thou wert, the second-person singular past subjunctive of the verb to be). The subjunctive forms are used when a statement is doubtful or contrary to fact; as such, they frequently occur after if and the poetic and.

- If thou be Johan, I tell it thee, right with a good advice …;[9]

- Be Thou my vision, O Lord of my heart …[10]

- I do wish thou wert a dog, that I might love thee something …[11]

- And thou bring Alexander and his paramour before the Emperor, I’ll be Actaeon …[12]

- O WERT thou in the cauld blast, … I’d shelter thee …[13]

In modern regional English dialects that use thou or some variant, such as in Yorkshire and Lancashire, it often takes the third person form of the verb -s. This comes from a merging of Early Modern English second person singular ending -st and third person singular ending -s into -s (the latter a northern variation of -þ (-th)).

The present indicative form art («þu eart«) goes back to West Saxon Old English (see OED s.v. be IV.18) and eventually became standard, even in the south (e.g. in Shakespeare and the Bible). For its influence also from the North, cf. Icelandic þú ert. The preterite indicative of be is generally thou wast.[citation needed]

Etymology[edit]

Thou originates from Old English þū, and ultimately via Grimm’s law from the Proto-Indo-European *tu, with the expected Germanic vowel lengthening in accented monosyllabic words with an open syllable. Thou is therefore cognate with Icelandic and Old Norse þú, German and Continental Scandinavian du, Latin and all major Romance languages, Irish, Kurdish, Lithuanian and Latvian tu or tú, Greek σύ (sy), Slavic ты / ty or ти / ti, Armenian դու (dow/du), Hindi तू (tū), Bengali: তুই (tui), Persian تُو (to) and Sanskrit त्वम् (tvam). A cognate form of this pronoun exists in almost every other Indo-European language.[14]

History[edit]

Old and Middle English[edit]

þu, abbreviation for thou, from Adam and Eve, from a ca. 1415 manuscript, England

In Old English, thou was governed by a simple rule: thou addressed one person, and ye more than one. Beginning in the 1300s thou was gradually replaced by the plural ye as the form of address for a superior person and later for an equal. For a long time, however, thou remained the most common form for addressing an inferior person.[3]

The practice of matching singular and plural forms with informal and formal connotations is called the T–V distinction and in English is largely due to the influence of French. This began with the practice of addressing kings and other aristocrats in the plural. Eventually, this was generalized, as in French, to address any social superior or stranger with a plural pronoun, which was felt to be more polite. In French, tu was eventually considered either intimate or condescending (and to a stranger, potentially insulting), while the plural form vous was reserved and formal.[citation needed]

General decline in Early Modern English[edit]

Fairly suddenly in the 17th century, thou began to decline in the standard language (that is, particularly in and around London), often regarded as impolite or ambiguous in terms of politeness. It persisted, sometimes in an altered form, particularly in regional dialects of England and Scotland farther from London,[4] as well as in the language of such religious groups as the Society of Friends. Reasons commonly maintained by modern linguists as to the decline of thou in the 17th century include the increasing identification of you with «polite society» and the uncertainty of using thou for inferiors versus you for superiors (with you being the safer default) amidst the rise of a new middle class.[15]

In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson, in A Grammar of the English Tongue, wrote: «in the language of ceremony … the second person plural is used for the second person singular», implying that thou was still in everyday familiar use for the second-person singular, while you could be used for the same grammatical person, but only for formal contexts. However, Samuel Johnson himself was born and raised not in the south of England, but in the West Midlands (specifically, Lichfield, Staffordshire), where the usage of thou persists until the present day (see below), so it is not surprising that he would consider it entirely ordinary and describe it as such. By contrast, for most speakers of southern British English, thou had already fallen out of everyday use, even in familiar speech, by sometime around 1650.[16] Thou persisted in a number of religious, literary and regional contexts, and those pockets of continued use of the pronoun tended to undermine the obsolescence of the T–V distinction.

One notable consequence of the decline in use of the second person singular pronouns thou, thy, and thee is the obfuscation of certain sociocultural elements of Early Modern English texts, such as many character interactions in Shakespeare’s plays, which were mostly written from 1589 to 1613. Although Shakespeare is far from consistent in his writings, his characters primarily tend to use thou (rather than you) when addressing another who is a social subordinate, a close friend or family member, or a hated wrongdoer.[17]

Usage[edit]

Use as a verb[edit]

Many European languages contain verbs meaning «to address with the informal pronoun», such as German duzen, the Norwegian noun dus refers to the practice of using this familiar form of address instead of the De/Dem/Deres formal forms in common use, French tutoyer, Spanish tutear, Swedish dua, Dutch jijen en jouen, Ukrainian тикати (tykaty), Russian тыкать (tykat’), Polish tykać, Romanian tutui, Hungarian tegezni, Finnish sinutella, etc. Although uncommon in English, the usage did appear, such as at the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1603, when Sir Edward Coke, prosecuting for the Crown, reportedly sought to insult Raleigh by saying,

- I thou thee, thou traitor![18]

- In modern English: I «thou» you, you traitor!

here using thou as a verb meaning to call (someone) «thou» or «thee». Although the practice never took root in Standard English, it occurs in dialectal speech in the north of England. A formerly common refrain in Yorkshire dialect for admonishing children who misused the familiar form was:

- Don’t thee tha them as thas thee!

- In modern English: Don’t you «tha» those who «tha» you!

- In other words: Don’t use the familiar form «tha» towards those who refer to you as «tha». («tha» being the local dialectal variant of «thou»)

And similar in Lancashire dialect:

- Don’t thee me, thee; I’s you to thee!

- In standard English: Don’t «thee» me, you! I’m «you» to you!

See further the Wiktionary page on thou as a verb.

Religious uses[edit]

Christianity[edit]

Many conservative Christians use «Thee, Thou, Thy and Thine when addressing God» in prayer; in the Plymouth Brethren catechism Gathering Unto His Name, Norman Crawford explains the practice:[5]

The English language does contain reverential and respectful forms of the second person pronoun which allow us to show reverence in speaking to God. It has been a very long tradition that these reverential forms are used in prayer. In a day of irreverence, how good to display in every way that we can that «He (God) is not a man as I am» (Job 9:32).[5]

When referring to God, «thou» (as with other pronouns) is often capitalized, e.g. «For Thou hast delivered my soul from death» (Psalm 56:12–13).[19][20][21]

As William Tyndale translated the Bible into English in the early 16th century, he preserved the singular and plural distinctions that he found in his Hebrew and Greek originals. He used thou for the singular and ye for the plural regardless of the relative status of the speaker and the addressee. Tyndale’s usage was standard for the period and mirrored that found in the earlier Wycliffe’s Bible and the later King James Bible. But as the use of thou in non-dialect English began to decline in the 18th century,[22] its meaning nonetheless remained familiar from the widespread use of the latter translation.[23] The Revised Standard Version of the Bible, which first appeared in 1946, retained the pronoun thou exclusively to address God, using you in other places. This was done to preserve the tone, at once intimate and reverent, that would be familiar to those who knew the King James Version and read the Psalms and similar text in devotional use.[24] The New American Standard Bible (1971) made the same decision, but the revision of 1995 (New American Standard Bible, Updated edition) reversed it. Similarly, the 1989 Revised English Bible dropped all forms of thou that had appeared in the earlier New English Bible (1970). The New Revised Standard Version (1989) omits thou entirely and claims that it is incongruous and contrary to the original intent of the use of thou in Bible translation to adopt a distinctive pronoun to address the Deity.[25]

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which is still an authorized form of worship in the Church of England and much of the Anglican Communion, also uses the word thou to refer to the singular second person.[26][improper synthesis?]

Quakers traditionally used thee as an ordinary pronoun as part of their testimony of simplicity—a practice continued by certain Conservative Friends;[27] the stereotype has them saying thee for both nominative and accusative cases.[28] This was started at the beginning of the Quaker movement by George Fox, who called it «plain speaking», as an attempt to preserve the egalitarian familiarity associated with the pronoun. Most Quakers have abandoned this usage. At its beginning, the Quaker movement was particularly strong in the northwestern areas of England and particularly in the north Midlands area. The preservation of thee in Quaker speech may relate to this history.[29] Modern Quakers who choose to use this manner of «plain speaking» often use the «thee» form without any corresponding change in verb form, for example, is thee or was thee.[30]

In Latter-day Saint prayer tradition, the terms «thee» and «thou» are always and exclusively used to address God, as a mark of respect.[31]

Islam and Baháʼí Faith[edit]

In many of the Quranic translations, particularly those compiled by the Ahmadiyya, the terms thou and thee are used. One particular example is The Holy Quran — Arabic Text and English translation, translated by Maulvi Sher Ali.[32]

In the English translations of the scripture of the Baháʼí Faith, the terms thou and thee are also used. Shoghi Effendi, the head of the religion in the first half of the 20th century, adopted a style that was somewhat removed from everyday discourse when translating the texts from their original Arabic or Persian to capture some of the poetic and metaphorical nature of the text in the original languages and to convey the idea that the text was to be considered holy.[33]

Literary uses[edit]

Shakespeare[edit]

Like his contemporaries William Shakespeare uses thou both in the intimate, French-style sense, and also to emphasize differences of rank, but he is by no means consistent in using the word, and friends and lovers sometimes call each other ye or you as often as they call each other thou,[34][35][36] sometimes in ways that can be analysed for meaning, but often apparently at random.

For example, in the following passage from Henry IV, Shakespeare has Falstaff use both forms with Henry. Initially using «you» in confusion on waking he then switches to a comfortable and intimate «thou».

- Prince: Thou art so fat-witted with drinking of old sack, and unbuttoning thee after supper, and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldest truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? …

- Falstaff: Indeed, you come near me now, Hal … And, I prithee, sweet wag, when thou art a king, as God save thy Grace – Majesty, I should say; for grace thou wilt have none –

While in Hamlet, Shakespeare uses discordant second person pronouns to express Hamlet’s antagonism towards his mother.

- Queen Gertrude: Hamlet, thou hast thy father much offended..

- Hamlet: Mother, you have my father much offended.

More recent uses[edit]

Except where everyday use survives in some regions of England,[37] the air of informal familiarity once suggested by the use of thou has disappeared; it is used often for the opposite effect with solemn ritual occasions, in readings from the King James Bible, in Shakespeare and in formal literary compositions that intentionally seek to echo these older styles. Since becoming obsolete in most dialects of spoken English, it has nevertheless been used by more recent writers to address exalted beings such as God,[38] a skylark,[39] Achilles,[40] and even The Mighty Thor.[41] In The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader addresses the Emperor with the words: «What is thy bidding, my master?» In Leonard Cohen’s song «Bird on the Wire», he promises his beloved that he will reform, saying «I will make it all up to thee.» In Diana Ross’s song, «Upside Down», (written by Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards) there is the lyric «Respectfully I say to thee I’m aware that you’re cheatin’.» In «Will You Be There», Michael Jackson sings, «Hold me / Like the River Jordan / And I will then say to thee / You are my friend.» Notably, both Ross’s and Jackson’s lyrics combine thee with the usual form you.

The converse—the use of the second person singular ending -est for the third person—also occurs («So sayest Thor!»―spoken by Thor). This usage often shows up in modern parody and pastiche[42] in an attempt to make speech appear either archaic or formal. The forms thou and thee are often transposed.

Current usage[edit]

You is now the standard English second-person pronoun and encompasses both the singular and plural senses. In some dialects, however, thou has persisted,[43] and in others thou is retained for poetic and/or literary use. Further, in others the vacuum created by the loss of a distinction has led to the creation of new forms of the second-person plural, such as y’all in the Southern United States or yous by some Australians and heard in what are generally considered working class dialects in and near cities in the northeastern United States. The forms vary across the English-speaking world and between literature and the spoken language.[44] It also survives as a fossil word in the commonly-used phrase «holier-than-thou».[45]

Persistence of second-person singular[edit]

In traditional dialects, thou is used in the counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire and some western parts of Nottinghamshire.[46] Such dialects normally also preserve distinct verb forms for the singular second person, for example thee coost (standard English: you could, archaic: thou couldst) in northern Staffordshire. The word thee is used in the East Shropshire dialect which is now largely confined to the Dawley area of Telford and referred to as the Dawley dialect.[47] Throughout rural Yorkshire, the old distinction between nominative and objective is preserved.[citation needed] The possessive is often written as thy in local dialect writings, but is pronounced as an unstressed tha, and the possessive pronoun has in modern usage almost exclusively followed other English dialects in becoming yours or the local[specify] word your’n (from your one):[citation needed]

| Nominative | Objective | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second person | singular | tha | thee | thy (tha) | yours / your’n |

The apparent incongruity between the archaic nominative, objective and genitive forms of this pronoun on the one hand and the modern possessive form on the other may be a signal that the linguistic drift of Yorkshire dialect is causing tha to fall into disuse; however, a measure of local pride in the dialect may be counteracting this.

Some other variants are specific to certain areas. In Sheffield, the pronunciation of the word was somewhere in between a /d/ and a /th/ sound, with the tongue at the bottom of the mouth; this led to the nickname of the «dee-dahs» for people from Sheffield. In Lancashire and West Yorkshire, ta was used as an unstressed shortening of thou, which can be found in the song «On Ilkla Moor Baht ‘at». These variants are no longer in use.

In rural North Lancashire between Lancaster and the North Yorkshire border tha is preserved in colloquial phrases such as «What would tha like for thi tea?» (What would you like for your dinner), and «‘appen tha waint» («perhaps you won’t» – happen being the dialect word for perhaps) and «tha knows» (you know). This usage in Lancashire is becoming rare, except for elderly and rural speakers.

A well-known routine by comedian Peter Kay, from Bolton, Greater Manchester (historically in Lancashire), features the phrase «Has tha nowt moist?”[48]

(Have you got nothing moist?).

The use of the word «thee» in the song «I Predict a Riot» by Leeds band Kaiser Chiefs («Watching the people get lairy / is not very pretty, I tell thee») caused some comment[49] by people who were unaware that the word is still in use in the Yorkshire dialect.

The word «thee» is also used in the song Upside Down «Respectfully, I say to thee / I’m aware that you’re cheating».[50]

The use of the phrase «tha knows» has been widely used in various songs by Arctic Monkeys, a popular band from High Green, a suburb of Sheffield. Alex Turner, the band’s lead singer, has also often replaced words with «tha knows» during live versions of the songs.

The use persists somewhat in the West Country dialects, albeit somewhat affected. Some of the Wurzels songs include «Drink Up Thy Zider» and «Sniff Up Thy Snuff».[51]

Thoo has also been used in the Orcadian Scots dialect in place of the singular informal thou. In Shetland dialect, the other form of Insular Scots, du and dee are used. The word «thou» has been reported in the North Northern Scots Cromarty dialect as being in common use in the first half of the 20th century and by the time of its extinction only in occasional use.[52]

Use in cinema[edit]

The word thou can occasionally be heard in films recorded in certain English dialect. In Ken Loach’s films Kes, The Price of Coal and Looks and Smiles, the word is used frequently in the dialogue. It is used occasionally, but much less frequently, in the 1963 film This Sporting Life.

In the 2018 film Peterloo, the word is used by many of the working-class characters in Lancashire, including Samuel Bamford.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- T–V distinction

Citations[edit]

- ^ «thou, thee, thine, thy (prons.)», Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia Guide to Standard American English. 1993. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Pressley, J. M. (8 January 2010). «Thou Pesky ‘Thou’«. Shakespeare Resource Centre.

- ^ a b «yǒu (pron.)». Middle English Dictionary. the Regents of the University of Michigan. 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b Shorrocks, 433–438.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Norman (1997). Gathering Unto His Name. GTP. pp. 178–179.

- ^ Kortmann, Bernd (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 1117. ISBN 978-3110175325.

- ^ «Archaic English Grammar — dan.tobias.name». dan.tobias.name. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Fennell, Barbara A. (2001). A history of English: a sociolinguistic approach. Blackwell Publishing. p. 22.

- ^ Middle English carol:

If thou be Johan, I tell it the

Ryght with a good aduyce

Thou may be glad Johan to be

It is a name of pryce.

- ^ Eleanor Hull, Be Thou My Vision, 1912 translation of traditional Irish hymn, Rob tu mo bhoile, a Comdi cride.

- ^ Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, act IV, scene 3.

- ^ Christopher Marlowe, Dr. Faustus, act IV, scene 2.

- ^ Robert Burns, O Wert Thou in the Cauld Blast(song), lines 1–4.

- ^ Entries for thou and *tu, in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ Nordquist, Richard (2016). «Notes on Second-Person Pronouns: Whatever Happened to ‘Thou’ and ‘Thee’?» ThoughtCo. About, Inc.

- ^ Entry for thou in Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage.

- ^ Atkins, Carl D. (ed.) (2007). Shakespeare’s Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Associated University Presses. p. 55.

- ^ Reported, among many other places, in H. L. Mencken, The American Language (1921), ch. 9, ss. 4., «The pronoun».

- ^ Shewan, Ed (2003). Applications of Grammar: Principles of Effective Communication. Liberty Press. p. 112. ISBN 1930367287.

- ^ Elwell, Celia (1996). Practical Legal Writing for Legal Assistants. Cengage Learning. p. 71. ISBN 0314061150.

- ^ The Teaching of Christ: A Catholic Catechism for Adults. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. 2004. p. 8. ISBN 1592760945.

- ^ Jespersen, Otto (1894). Progress in Language. New York: Macmillan. p. 260.

- ^ David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography. (Yale, 1995) ISBN 0-300-06880-8. See also David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. (Yale, 2003) ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- ^ Preface to the Revised Standard Version Archived 2016-05-18 at the Wayback Machine 1971

- ^ «NRSV: To the Reader». Ncccusa.org. 2007-02-13. Archived from the original on 2010-02-06. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ^ The Book of Common Prayer. The Church of England. Retrieved on 12 September 2007.

- ^ «Q: What about the funny Quaker talk? Do you still do that?». Stillwater Monthly Meeting of Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ See, for example, The Quaker Widow by Bayard Taylor

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1991). Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506905-6.

- ^ Maxfield, Ezra Kempton (1926). «Quaker ‘Thee’ and Its History». American Speech. 1 (12): 638–644. doi:10.2307/452011. JSTOR 452011.

- ^ Oaks, Dallin H. (May 1983). «The Language of Prayer». Ensign.

- ^ (ISBN 1 85372 314 2) by Islam International Publications Ltd. Islamabad, Sheephatch Lane, Tilford, Surrey GUl 0 2AQ, UK.The Holy Quran, English Translation

- ^ Malouf, Diana (November 1984). «The Vision of Shoghi Effendi». Proceedings of the Association for Baháʼí Studies, Ninth Annual Conference. Ottawa, Canada. pp. 129–139.

- ^ Cook, Hardy M.; et al. (1993). «You/Thou in Shakespeare’s Work». SHAKSPER: The Global, Electronic Shakespeare Conference.

- ^ Calvo, Clara (1992). «‘Too wise to woo peaceably’: The Meanings of Thou in Shakespeare’s Wooing-Scenes». In Maria Luisa Danobeitia (ed.). Actas del III Congreso internacional de la Sociedad española de estudios renacentistas ingleses (SEDERI) / Proceedings of the III International Conference of the Spanish Society for English Renaissance studies. Granada: SEDERI. pp. 49–59.

- ^ Gabriella, Mazzon (1992). «Shakespearean ‘thou’ and ‘you’ Revisited, or Socio-Affective Networks on Stage». In Carmela Nocera Avila; et al. (eds.). Early Modern English: Trends, Forms, and Texts. Fasano: Schena. pp. 121–36.

- ^ «Why Did We Stop Using ‘Thou’?».

- ^ «Psalm 90». Archived from the original on August 13, 2004. Retrieved May 23, 2017. from the Revised Standard Version

- ^ Ode to a Skylark Archived 2009-01-04 at the Wayback Machine by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- ^ The Iliad, translated by E. H. Blakeney, 1921

- ^ «The Mighty Thor». Archived from the original on September 17, 2003. Retrieved May 23, 2017. 528

- ^ See, for example, Rob Liefeld, «Awaken the Thunder» (Marvel Comics, Avengers, vol. 2, issue 1, cover date Nov. 1996, part of the Heroes Reborn storyline.)

- ^ Evans, William (November 1969). «‘You’ and ‘Thou’ in Northern England». South Atlantic Bulletin. South Atlantic Modern Language Association. 34 (4): 17–21. doi:10.2307/3196963. JSTOR 3196963.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (June 1973). From Elfland to Poughkeepsie. Pendragon Press. ISBN 0-914010-00-X.

- ^ «Definition of HOLIER-THAN-THOU». www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (21 January 2000). The Dialects of England. p. 93. ISBN 978-0631218159.

- ^ Jackson, Pete (October 14, 2012). «The Dawley Dictionary». Telford Live.

- ^ «Has tha nowt moist — Youtube». YouTube.

- ^ «BBC Top of the Pops web page». Bbc.co.uk. 2005-09-29. Archived from the original on 2010-06-18. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ^ «Nile Rodgers Official Website».

- ^ «Cider drinkers target core audience in Bristol». Bristol Evening Post. April 2, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-04-05. Retrieved April 2, 2010, and Wurzelmania. somersetmade ltd. Retrieved on 12 September 2007.

- ^ The Cromarty Fisherfolk Dialect, Am Baile, page 5

General and cited references[edit]

- Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language, 5th ed. ISBN 0-13-015166-1

- Burrow, J. A., Turville-Petre, Thorlac. A Book of Middle English. ISBN 0-631-19353-7

- Daniel, David. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- Shorrocks, Graham (1992). «Case Assignment in Simple and Coordinate Constructions in Present-Day English». American Speech. 67 (4): 432–444. doi:10.2307/455850. JSTOR 455850.

- Smith, Jeremy. A Historical Study of English: Form, Function, and Change. ISBN 0-415-13272-X

- «Thou, pers. pron., 2nd sing.» Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1989). Oxford English Dictionary.

- Trudgill, Peter. (1999) Blackwell Publishing. Dialects of England. ISBN 0-631-21815-7

Further reading[edit]

- Brown, Roger and Gilman, Albert. The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity, 1960, reprinted in: Sociolinguistics: the Essential Readings, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22717-2, 978-0-631-22717-5

- Byrne, St. Geraldine. Shakespeare’s use of the pronoun of address: its significance in characterization and motivation, Catholic University of America, 1936 (reprinted Haskell House, 1970) OCLC 2560278.

- Quirk, Raymond. Shakespeare and the English Language, in Kenneth Muir and Sam Schoenbaum, eds, A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies*, 1971, Cambridge UP

- Wales, Katie. Personal Pronouns in Present-Day English. ISBN 0-521-47102-8

- Walker, Terry. Thou and you in early modern English dialogues: trials, depositions, and drama comedy, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007, ISBN 90-272-5401-X, 9789027254016

External links[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 11 September 2007, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- A Grammar of the English Tongue by Samuel Johnson – includes description of 18th century use

- Contemporary use of thou in Yorkshire

- Thou: The Maven’s Word of the Day

- You/Thou in Shakespeare’s Work (archived forum discussion)

- A Note on Shakespeare’s Grammar by Seamus Cooney

- The Language of Formal Prayer by Don E. Norton, Jr. — LDS

Содержание

Личное местоимение «thou« [ðʌu] указывающее на второе лицо единственное число, в современном английском вышло из общего употребление и считается архаизмом, сохранилось в употреблении некоторых диалектах английского языка.

Формы местоимения thou

Спряжение глаголов с местоимением Thou

При спряжении с местоимением «thou», глаголы в форме настоящего времени принимают окончание -est [st]:

-

Thou readest seldom. [rɪ:dst] – Ты редко читаешь.

Если в конце глагола, в основной форме, имеется непроизносимая -e, то одна e опускается:

-

tie (завязывать) → Thou tiest my hands(1). – Ты связываешь меня по рукам (и ногам).

Если основная форма глагола заканчивается на -y, перед которой стоит согласная, то -y меняется на -i:

-

Thou studiest English grammar. – Ты изучаешь грамматику английского языка.

При спряжении с «thou», глаголы в прошедшем времени имеют окончание -edst:

-

Thou askedst too much questions. – Ты задавал слишком много вопросов.

Если в конце глагола, в основной форме, имеется не произносимая -e, то одна e опускается:

-

decide (решать): thou decidedst (ты решил)

Окончание -edst / -dst читаются как [ɪdst] после согласных t и d, как [dst] после гласных и звонких согласных звуков и как [tst] после глухих согласных:

-

want [wɔnt] → wantedst [wɔntɪdst]

-

play [pleɪ] → playedst [pleɪdst]

-

open [‘əupən] → openedst [‘əupəndst]

-

work [wə:rk] → workedst [wə:rktst]

Если глагол оканчивается на y, перед которой стоит согласная, то y меняется на ie без изменения в произношении:

-

try → triedst [trʌɪdst]

Если глагол, состоящий из одного или двух слогов, оканчивается на согласную, которой предшествует краткий звук, то конечная согласная обычно удваивается:

-

stop → stoppedst

Простое прошедшее время неправильных глаголов, с местоимением «thou» образуется добавлением к глаголу в прошедшем времени окончания -est [st] или -st, если глагол оканчивается на e:

-

come — came — camest [keɪmst]

-

meet — met — metest [metst]

Следует отметить, что выбор между окончаниями глаголов во втором лице, с буквой e и без e, является все-таки не однозначным, так как правописание того времени не было стандартизировано, это касается употребления не только окончаний, но и некоторых других моментов в грамматике употребления местоимения «thou».

С личным местоимением «thou» также спрягаются модальные глаголы. При спряжении написание модальных и некоторых других глаголов отличается от приведённых выше правил (имеют особую форму) и их нужно запоминать:

Спряжение модальных и некоторых других неправильных глаголов с местоимением Thou

| инфинитив / основа | форма настоящего времени | форма прошедшего времени |

|---|---|---|

| can | canst | couldst |

| may | mayest | mightst |

| will | wilt | wouldst |

| shall | shalt | shouldst |

| be | art beest1 |

wast wert2 |

| do | dost3 [dʌst] doest [du:ɪst] |

didst |

| have | hast [hæst] | hadst |

|

Примечания

1)

«Tie somebody’s hands» идиом. сделать кого-либо неспособным действовать или продолжить действие, аналогичное русскому «связать по рукам и ногам»

Упоминания

1]

William Shakespeare The Tempest

2]

«Over the Moon»: A musical play by Jodi Picoult & Jake van Leer.

English[edit]

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English thou, tho, thogh, thoue, thouȝ, thow, thowe, tou, towe, thu, thue, thugh, tu, you (Northern England), ðhu, þeou, þeu, þou (the latter three early Southwest England), from Old English þū,[1] from Proto-West Germanic *þū, from Proto-Germanic *þū (“you (singular), thou”), from Proto-Indo-European *túh₂ (“you, thou”).

cognates and usage evolution

The English word is cognate with Saterland Frisian du (“thou”), West Frisian do (“thou”), dialectal Dutch du, dou, douw (“thou”), Limburgish doe (“thou”), Low German du (“thou”), German du (“thou”), Danish du (“thou”), Swedish du (“thou”), Faroese tú (“thou”), Icelandic þú (“thou”), Gothic 𐌸𐌿 (þu, “thou”), Latin tu, Ancient Greek σύ (sú) (Doric Ancient Greek τύ (tú), Greek εσύ (esý)), Irish tu, Lithuanian tu, Old Church Slavonic ty, Welsh ti, Armenian դու (du), Albanian ti, Persian تو (to).[2]

The informality of thou and its replacement by ye in formal situations date only to the 14th century and come from French influence, since French (as many European languages, but not Old English) uses the second-person plural (vous) instead of the second-person singular (tu) as a mark of politeness or respect.

Alternative forms[edit]

- tha (Yorkshire, Lancashire)

- thow, thu, du (Scotland)

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation, General American):

- enPR: thou, IPA(key): /ðaʊ/

- Rhymes: -aʊ

- (dialectal, Northern England, Scotland):

- IPA(key): /ðu/

Pronoun[edit]

thou (plural ye, objective case thee, reflexive thyself, possessive determiner thy or thine, possessive pronoun thine)

- (archaic, dialectal, literary, religion, or humorous) Nominative singular of ye (“you”). [chiefly up to early 17th c.]

-

1742 April 4, Charles Wesley, A Sermon Preached on Sunday, April 4, 1742. Before the University of Oxford, London: Printed by J. Paramore, […], published 1783, →OCLC, page 10:

-

Art thou in earnest about thy soul? and canst thou tell the Searcher of Hearts, Thou, O God, art the thing that I long for? Lord, Thou knowest all things, Thou knowest that I would love thee?

-

-

1843 December 19, Charles Dickens, “Stave Four. The Last of the Spirits.”, in A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, London: Chapman & Hall, […], →OCLC, page 137:

-

Oh cold, cold, rigid, dreadful Death, set up thine altar here, and dress it with such terrors as thou hast at thy command: for this is thy dominion!

-

- For more quotations using this term, see Citations:thou.

-

Usage notes[edit]

- When the subject of a verb in the indicative mood is thou, the verb usually ends in -est, in both the present and simple past tenses, as in “Lovest thou me?” (from John 21:17 of the King James Bible). This is the case even for modal verbs, which do not specially conjugate for the third person singular. A few verbs have irregular present forms: art (of be), hast (of have), dost (of do), wost (of wit), canst (of can), shalt (of shall), wilt (of will). Must does not change. In weak past tenses, the ending is either -edest or contracted -edst. In the subjunctive, as is normal, the bare form is usually used. However, thou beest is sometimes used instead of thou be.

- Traditionally, use of thou and ye followed the T–V distinction, thou being the informal pronoun and ye, the plural, being used in its place in formal situations. This is preserved in the dialects in which thou is still in everyday use, but in Standard English, due to the pronoun’s association with religious texts and poetry, some speakers find it more solemn or even formal.

- Occasionally thou was, and to a lesser extent still is, used to represent a translated language’s second-person singular-plural distinction, disregarding English’s T-V distinction by translating the second-person singular as thou even where English would likely use ye instead. It is also sometimes still used to represent a translated language’s T-V distinction.

Alternative forms[edit]

- du, tha, thoo, thow, thu

Derived terms[edit]

- holier-than-thou

- thou’dst

- thou’lt

- thou’rt

- thou’st

Translations[edit]

singular nominative form of you

- Arabic: أَنْتَ (ar) m (ʔanta), أَنْتِ (ar) f (ʔanti)

- Egyptian Arabic: انت m (ínta), انت f (ínti)

- Tunisian Arabic: اِنْتِ m or f (ʾinti)

- Aragonese: tu (an)

- Armenian: դու (hy) (du)

- Aromanian: tu

- Assamese: তই (toi), তুমি (tumi) আপুনি (apuni)

- Asturian: tu (ast)

- Belarusian: ты (be) (ty)

- Bengali: তুই (bn) (tui)

- Bulgarian: ти (bg) (ti)

- Catalan: tu (ca)

- Chavacano: tu

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 你 (zh) (nǐ), 祢 (zh) (nǐ) (to God), (archaic) 爾/尔 (zh) (ěr), 汝 (zh) (rǔ)

- Corsican: tù

- Czech: ty (cs)

- Dalmatian: te

- Danish: du (da)

- Dutch: gij (nl) (archaic or dialectal), jij (nl)

- Esperanto: ci (eo)

- Extremaduran: tú

- Fala: tu

- Faroese: tú (fo)

- Finnish: sinä (fi)

- French: tu (fr) m or f

- Old French: tu

- Middle French: tu

- Friulian: tu

- Galician: ti (gl) m or f, tu (gl)

- Gallo: tu

- Georgian: შენ (ka) (šen)

- German: du (de), Du (de)

- Gothic: 𐌸𐌿 (þu)

- Greek:

- Ancient: σύ (sú)

- Hebrew: אתה (he) m (atá), את (he) f (at)

- Hindi: तुम (hi) (tum), तू (hi) (tū)

- Hungarian: te (hu)

- Icelandic: þú (is)

- Ido: tu (io)

- Indonesian: kamu (id)

- Irish: tú

- Istro-Romanian: tú

- Italian: tu (it)

- Japanese: 君 (ja) (きみ, kimi), 汝 (ja) (なんじ, nanji), お前 (ja) (おまえ, omae), あなた (ja) (anata)

- Karakhanid: سن (sen)

- Korean: 당신(當身) (ko) (dangsin), 너 (ko) (neo), 네 (ko) (ne)

- Ladin: tu

- Ladino: tu, טו (tu)

- Lao: ຄຸນ (khun), ເຖີ (thœ̄), ມືງ (mư̄ng)

- Latin: tu (la)

- Leonese: tu

- Lithuanian: tu (lt)

- Lü: ᦆᦳᧃ (xun), ᦵᦒᦲ (thoe), ᦙᦹᧂ (mueng)

- Macedonian: ти (mk) (ti)

- Malay: engkau

- Megleno-Romanian: tu

- Mirandese: tu

- Mozarabic: ت (tu)

- Navarro-Aragonese: tu

- Neapolitan: tu

- Norman: tu

- Northern Thai: ᨤᩩᨶ, ᨮᩮᩬᩥ, ᨾᩨ᩠ᨦ

- Norwegian: du (no)

- Occitan: tu (oc)

- Ojibwe: giin

- Old Catalan: tu

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: тꙑ (ty)

- Glagolitic: ⱅⱏⰺ (ty)

- Old English: þū

- Old Irish: tú

- Old Occitan: tu

- Old Polish: ty

- Old Portuguese: tu

- Old Turkic: 𐰾𐰤 (s²n²)

- Ottoman Turkish: سن (sen)

- Persian: تو (fa) (to)

- Picard: tu

- Polabian: tåi

- Polish: ty (pl)

- Portuguese: tu (pt)

- Romanian: tu (ro)

- Romansch: tu, tü

- Russian: ты (ru) (ty)

- Sardinian: tue

- Scots: thoo

- Scottish Gaelic: thu, tu

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: ти̑

- Roman: tȋ (sh)

- Sicilian: tu (scn)

- Sinhalese: ඔයා (oyā)

- Slovak: ty (sk)

- Slovene: tí (sl)

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: ty

- Upper Sorbian: ty (hsb)

- Spanish: tú (es) m or f

- Old Spanish: tu

- Swedish: du (sv)

- Thai: คุณ (th) (kun), เธอ (th) (təə), มึง (th) (mʉng)

- Turkish: sen (tr)

- Udihe: си

- Ukrainian: ти (uk) (ty)

- Urdu: تم (ur) (tum), تو (tū)

- Venetian: ti (vec)

- Vietnamese: mày (vi), ngươi (vi), mi (vi)

- Walloon: tu (wa)

- Welsh: ti (cy)

- Wiradhuri: ngindu

- Yiddish: דו m (du)

See also[edit]

Etymology 2[edit]

From Late Middle English thouen, theu, thew, thou, thowe, thowen, thui, thuy (“to address (a person) with thou, particularly in a contemptuous or polite manner”), from the pronoun thou: see etymology 1 above.[3]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation, General American) enPR: thou, IPA(key): /ðaʊ/

- Rhymes: -aʊ

Verb[edit]

thou (third-person singular simple present thous, present participle thouing, simple past and past participle thoued)

- (transitive) To address (a person) using the pronoun thou, especially as an expression of contempt or familiarity.

- Synonym: thee

- Antonym: you

-

Don’t thou them as thous thee! – a Yorkshire English admonition to overly familiar children

-

c. 1530, “Hickscorner”, in W[illiam] Carew Hazlitt, editor, A Select Collection of Old English Plays. Originally Published by Robert Dodsley in the Year 1744. […], volume I, 4th edition, London: Reeves and Turner, […], published 1874, page 180:

-

Avaunt, caitiff, dost thou thou me! / I am come of good kin, I tell thee! / My mother was a lady of the stews’ blood born, / And (knight of the halter) my father ware an horn; / Therefore I take it in full great scorn, / That thou shouldest thus check me.

-

-

c. 1601–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, “Twelfe Night, or What You Will”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act III, scene ii], page 266:

-

[T]aunt him with the licenſe of Inke: if thou thou’ſt him some thrice, it ſhall not be amiſſe, and as many Lyes, as will lye in thy ſheete of paper, although the ſheete were bigge enough for the bedde of Ware in England, ſet ’em downe, go about it.

-

-

1603 November 27, “The Tryal of Sir Walter Raleigh Kt. at Winton, on Thursday the 17th of November, Anno. Dom. 1603. in the First Year of King James the First”, in [Thomas Salmon], editor, A Compleat Collection of State-Tryals, and Proceedings upon Impeachment for High Treason, and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours; […] In Four Volumes, volume I, London: Printed for Timothy Goodwin, […]; John Walthoe […]; Benj[amin] Tooke […]; John Darby […]; Jacob Tonson […]; and John Walthoe Jun. […], published 1719, →OCLC, page 177, column 2:

-

1677, William Gibson, “An Answer to John Cheyney’s Pamphlet Entituled The Shibboleth of Quakerism”, in The Life of God, which is the Light and Salvation of Men, Exalted: […], [London: s.n.], →OCLC, page 134:

-

What! doſt thou not believe that God’s Thouing and Theeing was and is ſound Speech? […] And Theeing & Thouing of one ſingle Perſon was the language of Chriſt Jeſus, and the Holy Prophets and Apoſtles both under the Diſpenſations of Law and Goſpel, […]

-

-

1755, [Voltaire [pseudonym; François-Marie Arouet]], “Ferdinand III. Forty-seventh Emperor.”, in Annals of the Empire from the Reign of Charlemagne […] In Two Volumes, volume II, London: Printed for A[ndrew] Millar, […], →OCLC, page 257:

-

The emperors before Rodolphus I. ſent all their mandates in Latin, thouing every prince, as the grammar of that language allows. This thouing of the counts of the empire was continued in the German language which diſallows ſuch expreſſions.

-

-

1811, Miguel Cervantes de Saavedra, “Of Matters Relating and Appertaining to this Adventure, and to this Memorable History”, in Charles Jarvis, transl., The Life and Exploits of Don Quixote de la Mancha. Translated from the Spanish […] In Four Volumes, volume IV, London: Printed [by Harding & Wright] for Lackington, Allen, and Co. [et al.], →OCLC, part II, book III, pages 57–58:

-

Unfortunate we the duennas! though we descended in a direct male-line from Hector of Troy, our mistresses will never forbear «thouing» us, were they to be made queens for it.

-

-

1888, Rudyard Kipling, “On the City Wall”, in In Black and White (A. H. Wheeler & Co.’s Indian Railway Library; no. 3), 5th edition, Allahabad: Messrs. A. H. Wheeler & Co.; London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, Ld., […], published 1890, →OCLC, page 91:

-

«One service more, Sahib, since thou hast come so opportunely,» said Lalun. «Wilt thou»–it is very nice to be thou-ed by Lalun–»take this old man across the City—the troops are everywhere, and they might hurt him for he is old—to the Kumharsen Gate?[«]

-

-

1917, Russell Osborne Stidston, “Inferiors to Superiors”, in The Use of Ye in the Function of Thou in Middle English Literature from Ms. Auchinleck to Ms. Vernon: A Study of Grammar and Social Intercourse in Fourteenth-century England: […], Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University, →OCLC, section 1 (The Higher Classes to Royalty), page 22:

-

In Guy a duke in council thous his emperor […] In Bevis the earl addresses the emperor of Almaine […] while the young son of the family, Bevis, thous him not only as his father’s murderer […], but even when he is pretending friendship for him […].

-

- (intransitive) To use the word thou.

- Synonym: thee

- Antonym: you

-

2006, Julian Dibbell, chapter 5, in Play Money: Or, How I Quit My Day Job and Made Millions Trading Virtual Loot, New York, N.Y.: Basic Books, →ISBN:

-

The hardcore role-players will wake up one day feeling, like a dead weight on their chest, the strain of endless texting in Renaissance Faire English—yet dutifully go on theeing and thouing all the same.

-

-

2009, David R. Keeston [pseudonym; Alan D. Jenkins], “Seeing God in the Ordinary”, in The Hitch Hikers’ Guide to the Gospel, [Morrisville, N.C.]: Lulu.com, →ISBN, page 39:

-

You want to hear the word of God, and be challenged to go out and change the world. Instead, you are, for the fifth Sunday in a row, mewling on about purple-headed mountains (which is a bit of an imaginative stretch, since you live in East Anglia) and «theeing» and «thouing» all over the place.

-

[edit]

- tutoy, tutoyer

Translations[edit]

to address (a person) using the familiar second-person pronoun

- Asturian: tutiar (ast)

- Belarusian: ты́каць impf (týkacʹ)

- Catalan: tutejar (ca)

- Czech: tykat (cs) impf

- Danish: (please verify) dusse, sige du

- Dutch: tutoyeren (nl), jijen (nl), jouen (nl)

- Estonian: sinatama

- Faroese: túa

- Finnish: sinutella (fi)

- French: tutoyer (fr)

- German: duzen (de)

- Greek: μιλώ στον ενικό (miló ston enikó, literally “speak in the singular”)

- Hungarian: tegez (hu)

- Icelandic: þúa

- Interlingua: tutear

- Italian: dare del tu

- Japanese: 呼び捨てにする (ja) (よびすてにする, yobisute ni suru)

- Korean: 너라고 부르다 (neo-rago bureuda)

- Lithuanian: tujinti (lt)

- Malay: berengkau

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: (please verify) dus, si ‘du’

- Occitan: tutejar

- Polish: mówić na ty impf, tykać (pl) impf (colloquial)

- Portuguese: tutear, tratar por tu

- Romanian: a tutui (ro)

- Russian: ты́кать (ru) impf (týkatʹ) (colloquial), ты́кнуть (ru) pf (týknutʹ), обраща́ться на «ты» impf (obraščátʹsja na “ty”)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: ти́кати impf, говорити ти

- Roman: tíkati (sh) impf, govoriti ti

- Slovak: tykať impf

- Slovene: tíkati impf

- Sorbian:

- Upper Sorbian: tykać impf

- Spanish: tutear (es)

- Swedish: dua (sv)

- Turkish: sen (tr)

- Ukrainian: ти́кати impf (týkaty)

Etymology 3[edit]

Clipping of thou(sandth).[4]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation, General American) enPR: thou, IPA(key): /θaʊ/

- Rhymes: -aʊ

Noun[edit]

thou (plural thous)

- (Britain) A unit of length equal to one-thousandth of an inch (25.4 µm).

- Synonym: (US) mil

-

1946 November and December, Cecil J. Allen, “British Locomotive Practice and Performance”, in Railway Magazine, page 344:

-

But to continue, «At Horwich they had gone all scientific, and talked in ‘thous.,’ though apparently some of their work was to the nearest half-inch. […] .»

-

-

1984, Robert D. Adams; William C. Wake, “Surface Preparation”, in Structural Adhesive Joints in Engineering, Barking, Essex: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers, published 1986, →DOI, →ISBN, pages 220–221:

-

All these methods remove metal and can, in fact, remove a few thou from the surface. For accurately machined parts, therefore, none of these methods are suitable but wet blasting with a fine alumina which gives a polishing–cleaning action may be operated within the required tolerances.

-

-

2000, Mike Bishop; Vern Tardel, “Bells and Whistles”, in How to Build a Traditional Ford Hot Rod, revised edition, Osceola, Wis.: MBI Publishing Company, →ISBN, page 131, column 2:

-

Make no mistake, we’re talking about some major repositioning; the rear ends of the cones didn’t move just a few thou’ or even 1/4 or 1/2 inch in one direction. These beauties moved around big time.

-

Etymology 4[edit]

Clipping of thou(sand).[4]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation, General American) enPR: thou, IPA(key): /θaʊ/

- Rhymes: -aʊ

Noun[edit]

thou (plural thou)

- (slang) A thousand, especially a thousand of some currency (dollars, pounds sterling, etc.).

-

1977, Larry Pointer, “Belle Fourche”, in In Search of Butch Cassidy (Red River Books), Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, published 1988, →ISBN, page 132:

-

Butch [Cassidy] gave him 3 thous in cash 1 thous for the lawyer another thous if the lawyer wins & 1 thous for Tom O’Day.

-

-

1999, Don Winslow, chapter 58, in California Fire and Life, New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, →ISBN; 1st Vintage Crime/Black Lizard edition, New York, N.Y.: Vintage Books, September 2007, →ISBN, page 169:

-

He has a few thou in the account, enough to make your everyday living expenses, not enough to keep current with the bigger bills.

-

-

2000 November, Sheri S[tewart] Tepper, “Benita”, in The Fresco, New York, N.Y.: Eos, HarperCollins, →ISBN; 1st Eos paperback edition, New York, N.Y.: Eos, HarperCollins, February 2002, →ISBN, page 17:

-

Well, we’ll need a few thou, Carlos. Got to get together a few thou first. For rent, you know. Rent and making contacts with artists, all that.

-

-

Etymology 5[edit]

See though.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) enPR: thō, IPA(key): /ðəʊ/

- (General American) enPR: thō, IPA(key): /ðoʊ/

Adverb[edit]

thou (not comparable)

- Misspelling of though.

Conjunction[edit]

thou

- Misspelling of though.

References[edit]

- ^ “thǒu, pron.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Compare “thou, pron. and n.1”, in OED Online

, Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, March 2012; “thou1, pron.”, in Lexico, Dictionary.com; Oxford University Press, 2019–2022.

- ^ “thǒuen, v.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 11 July 2019; “thou, v.”, in OED Online

, Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, March 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “thou, n.2”, in OED Online

, Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, March 2012; “thou2, n.”, in Lexico, Dictionary.com; Oxford University Press, 2019–2022.

Further reading[edit]

Anagrams[edit]

- Hout, Huot, hout

Middle English[edit]

Pronoun[edit]

thou (objective the, possessive determiner thy, possessive pronoun thyn)

- Alternative form of þou

References[edit]

- “thǒu, pron.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 5 May 2018.

Scots[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- du, thoo

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English þou, from Old English þū, from Proto-Germanic *þū, from Proto-Indo-European *túh₂ (“you”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ðu/

- (Orkney, Shetland) IPA(key): /du/

Pronoun[edit]

thou (objective case thee, reflexive thysel, possessive determiner thy)

- (archaic outside Orkney and Shetland) thou, you (2nd person singular subject pronoun, informal)

Usage notes[edit]

- Regularly used throughout Scotland up until the middle of the 1800s; now only used as an archaism outside Shetland and Orkney.

References[edit]

- “thou, pers. pron, v.” in the Dictionary of the Scots Language, Edinburgh: Scottish Language Dictionaries.

Yola[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- th’

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English þou, from Old English þū, from Proto-West Germanic *þū.

Pronoun[edit]

thou

- thou

-

1867, GLOSSARY OF THE DIALECT OF FORTH AND BARGY:

-

Co thou; Co he.

- Quoth thou; Says he.

-

-

Derived terms[edit]

- th’ast

- th’art

References[edit]

- Jacob Poole (1867), William Barnes, editor, A Glossary, With some Pieces of Verse, of the old Dialect of the English Colony in the Baronies of Forth and Bargy, County of Wexford, Ireland, London: J. Russell Smith, page 31

The words “thee” and “thou” have been around for centuries, and although they have since been replaced, they still come up today in modern English. This page looks at the terms’ meanings and explains their differences.

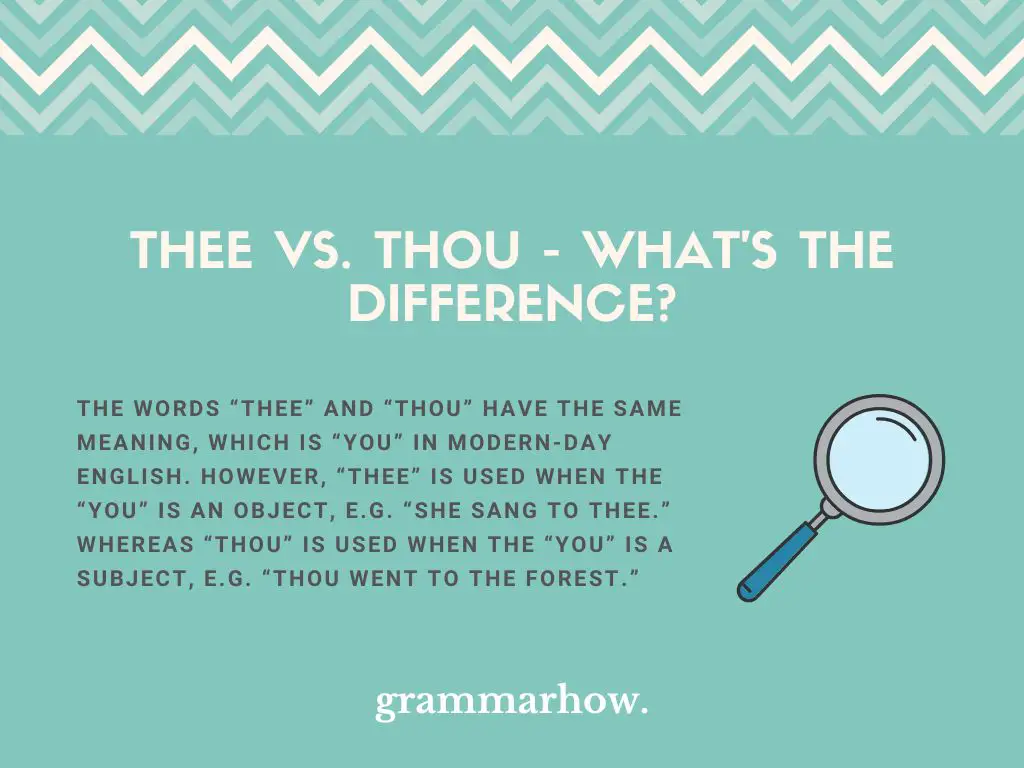

The words “thee” and “thou” have the same meaning, which is “you” in modern-day English. However, “thee” is used when the “you” is an object, e.g. “She sang to thee.” Whereas “thou” is used when the “you” is a subject, e.g. “Thou went to the forest.”

The Cambridge Dictionary states that the word “thou” is an archaic pronoun used to mean “you”, the Cambridge Dictionary also states that “thee” is listed as the object form of the word “thou.”

There are some occasions when these pronouns are still used quite commonly today. For example, you will often see them appearing in religious texts or church ceremonies such as weddings when they say, “With this ring, I thee wed.”

Also, in parts of the north of England, it is still quite common to hear people using the terms and other variations such as “tha” to mean “you.”

The difference between “thee” and “thou” is that “thee” is used when the person you are talking to is the object of the sentence, and “thou” is used when the person is the subject.

Here are some examples: Please note that in old English, the other words in the sentence would often be different too, such as “have” would become “hast.” However, for the purpose of these examples, modern words have been used to replace them.

- When I arrive, thou will see my new appearance.

- Thou know that he is not a good man.

- Have thou ever read the bible?

- He gave it to thee yesterday.

- I am sure that she loves thee dearly.

Thee

The word “thee” is the object version of the pronoun “you.” It is an old word that is not that common in modern-day English because it has been replaced by the term “you”, which means both “thee” and “thou.” However, although uncommon in today’s English, it is still used in colloquial spoken English in some parts of the UK, such as Yorkshire.

Here are some examples to show the use of the “thee” in a sentence:

- She gave thee all her love and affection.

- That man will never give thee children, so you shouldn’t marry him.

- I am glad that thee were invited to the function.

- I will show thee my true intentions.

Thou

The word “thou” is the subject pronoun version of the term “you.” It is an old word that is not really in use anymore, except for in a few regions of the UK, although in these regions, “tha” is more common as the subject version of “you” and “thee” as the object version.

Nonetheless, you will still come across the term “thou” in written English, especially if you are reading Shakespeare or literature from the same period.

Here are some examples of how “thou” can be used in a sentence

- Thou must display to me that you know how to get there.

- I think that thou can redeem yourself from your evil doings.

- We believe that thou have become the best father.

- I hope that thou shall wait for my return.

Which Is Used the Most?

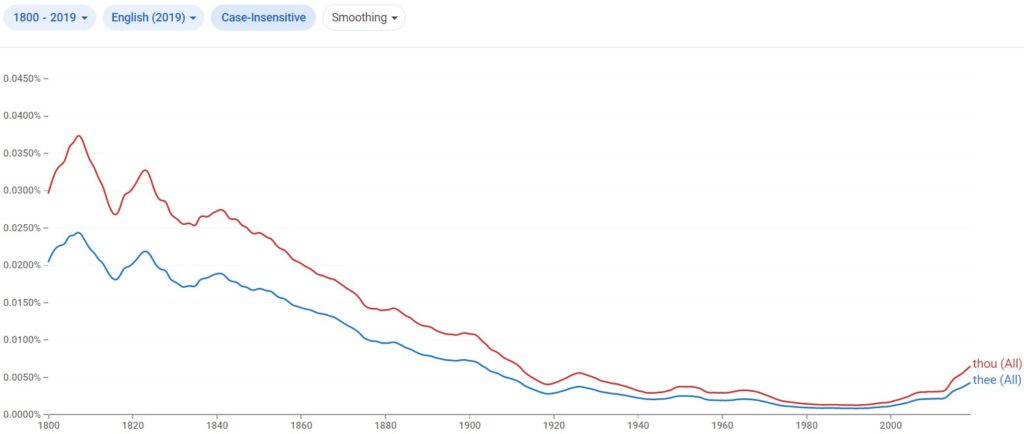

The Google Ngram shows us that both words have declined steadily for 200 years. However, “thou” has always been more common than “thee”, probably because it is more common to use active sentences with subject pronouns rather than passive ones with object pronouns; therefore, more sentences would use “thou.”

Historically both words have been more common in British English than in American English, but still, neither are massively common today in written English.

Final Thoughts

The words “thee” and “thou” have the same meaning, which is “you.” However, “thee” is used when the person is the object of the sentence and “thou” is used when the person is the subject. They are not really used in modern-day written English, except perhaps in religious texts.

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.

В отзывах на мою прошлую статью в блоге, вы попросили подробней рассказать об английском местоимении thou. C удовольствием это делаю.

Посмотрите на заголовок моей статьи. Я не случайно написала слово «Ты» с заглавной буквы. Именно так следует по-английски обращаться к Богу.

Be Thou my vision, O Lord of my heart! – Господи, Боже будь светом моим!

Написанное со строчной буквы, thou было до XVII века обычным местоимением, 2-го лица, единственного числа (ты).

Сегодня местоимение thou и его формы thy – твой и thee – тебе, тебя, можно встретить только в поэзии, молитвах и средневековой литературе. Например, в 3-м сонете Шекспира я нашла все эти формы.

Shakespeare. Sonnet III,

Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime:

So thou through windows of thine age shall see

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single, and thine image dies with thee

Шекспир. Сонет 3. Перевод С. Маршака

Прекрасный облик в зеркале ты видишь,

И, если повторить не поспешишь

Свои черты, природу ты обидишь,

Благословенья женщину лишишь.

Какая смертная не будет рада

Отдать тебе нетронутую новь?

Или бессмертия тебе не надо, –

Так велика к себе твоя любовь?

Для материнских глаз ты – отраженье

Давно промчавшихся апрельских дней.

И ты найдешь под старость утешенье

В таких же окнах юности твоей.

Но, ограничив жизнь своей судьбою,

Ты сам умрешь, и образ твой – с тобою.

Хочу обратить ваше внимание на странные с виду глаголы, следующие за формами местоимения thou (я их выделила курсивом). Это, на самом деле, знакомые нам глаголы

- to view – видеть;

- to renew – повторять;

- to do – делать;

Эти глаголы, спрягаясь после thou, приобрели окончания -st и –est.

А в слове art вообще невозможно узнать глагол be, многоликий и в современном английском!

Что погубило местоимение «thou»

В средние века широкое распространение получили формы множественного числа – Ye и You. Их использовали для выражения уважения и почтения по отношению к чиновникам и другим важным персонам. Популярность форм множественного числа, можно сказать, погубила местоимение единственного числа thou. Уже к 1600 г. оно приобрело оттенок фамильярности и вскоре совсем вышло из употребления, сохранившись лишь в поэзии и в Библии.

Дошло до того, что про англичан теперь шутят: они обращаются на «вы» даже к своей собаке!

Вдумчиво изучая английский язык, можно заметить, что различие в числе местоимений второго лица, до сих пор сохранилось в их возвратных формах:

- yourself – единственное число и вежливое обращение на «вы»;

- yourselves – множественное число.

А как у нас?

Интересно, что в славянских языках всё происходило с точностью до наоборот. Слово «вы» у нас появилось только в 16-м веке.

На Руси при общении один на один всегда говорили «ты». Русскому человеку показалось бы весьма странным форму множественного числа относить к одному лицу. Причём тут почтение? Если собеседник один — число единственное, двое — двойственное (была особая форма местоимения — ва), три и больше — множественное.

С XVI века, под влиянием модного польского этикета, обращение на «вы» дошло и до России. Оно еще долгое время оставалось формой аристократической, и под влиянием европейских языков, стало всё чаще употребляться в обществе.

В современном русском языке общение в любых формальных ситуациях происходит исключительно на «вы». Крайним неуважением и грубым нарушением русского речевого этикета является обращение на «ты» младшего к старшему незнакомому человеку. Дурным тоном также считается обращаться на «ты» к обслуживающему персоналу учреждений.

местоимение ↓

- pers pron уст., поэт. ты

thou knowest — ты знаешь

thou seest — ты зришь

hearest thou? — слышишь ли ты?

thou art nothing — ты ничто

глагол

- обращаться на «ты»

- разг. сокр. от thousand

Мои примеры

Примеры с переводом

Thou shalt not steal.

Не кради. (Библия, книга Исход, гл. 20, ст. 15)

She earns more than a hundred thou a year.

Она зарабатывает больше ста тыщ в год. (амер., разг.)

Wherefore art thou Romeo? (= Why are you Romeo?)

Почему ты, Ромео? (фраза из «Ромео и Джульетта», выражающая сожаление из-за того что Ромео принадлежит семье Монтеги)

Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.

Прах ты и в прах возвратишься. (Библия, книга Бытия, гл. 3, ст. 19)

Thou (= you) wilt (= will) not leave us here in the dust.

Ты не оставишь нас здесь в пыли.

Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. (Bible, Matthew 19: 19)

Люби ближнего твоего, как самого себя. (Евангелие от Матфея, гл. 19, ст. 19)

Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church.

Ты — Петр, и на сём камне я создам церковь мою.

They paid about sixty-nine thou for it.

За это заплатили тыщ шестьдесят девять.

Thou shalt have none other gods before me.

Да не будет у тебя других богов, кроме меня.

Why hast (= have) thou (= you) asked my derivation?

Почему ты спросил меня о моем происхождении?

Trust in the Lord…and verily thou shalt be fed

Доверься Господу … и, воистину, будешь накормлен

Thou art careful and troubled about many things.

Ты заботишься и тревожишься о многом. (уст.)

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

…a favorite line of an Eastern Church hymn reads, “through fast-closed doors Thou camest Thy Disciples to illume”…

Для того чтобы добавить вариант перевода, кликните по иконке ☰, напротив примера.

Возможные однокоренные слова

you — вы, вам, вами, вас, ты, тебя, тебе, тобой

|

|

В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации.

Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

Слово thou (транскрипция [ðaʊ]) ранее являлось местоимением второго лица единственного числа в английском языке. Впоследствии было вытеснено местоимением второго лица множественного числа you, в силу повсеместного обращения на «вы» (известна шутка, что англичанин обращается на «вы» даже к своей собаке). До недавнего времени форма thou сохранялась в религиозных текстах для обращения к Господу, ныне является устаревшей, хотя иногда встречается в разговоре на севере Англии и Шотландии, а также кое-где в США. Стоит в именительном падеже, косвенный падеж thee, притяжательная форма thy или thine. Практически все глаголы, относящиеся к thou, имеют окончание -st и -est, например thou goest (ты идешь). В Англии начала XI — середины XV века слово thou иногда сокращалось подставлением небольшой буквы u над буквой англосаксонского алфавита Þ (торн).

Спряжение

С данным местоимением необходимо употреблять формы второго лица единственного числа, в современном английском не находящиеся в активном употреблении. Как уже было упомянуто выше, глаголы, следующие за словом thou, обычно заканчиваются на -st или -est в изъявительном наклонении как в настоящем, так и в прошедшем времени. Ниже приведен типичный пример использования глаголов с этим словом. Букву e в окончании можно не использовать. Старый английский язык в части правописания ещё не был стандартизирован.

| Выражение | Настоящее время | Прошедшее время |

|---|---|---|

| you know (ты знаешь) | thou knowest | thou knewest |

| you drive (ты водишь) | thou drivest | thou drovest |

| you make (ты делаешь) | thou makest | thou madest |

| you love (ты любишь) | thou lovest | thou lovedest |

Некоторые неправильные глаголы используются следующим образом.

| Выражение | Настоящее время | Прошедшее время |

|---|---|---|

| you are (ты есть) | thou art (или thou beest) | thou wast (или thou wert) |

| you have (ты имеешь) | thou hast | thou hadst |

В старом английском глагол при спряжении с местоимением thou получал окончание -es. Практически неизменённым оно пришло от индоевропейских языковых групп и может наблюдаться в написании слов многих стран. Например:

- Знаешь: русский язык — znaješ (транскрипция), английский язык — thou knowest

- Любишь: латинский язык — amas, английский — thou lovest

Этимология слова

Слово thou произошло от староанглийского þú и в конечном счете от протоиндоевропейского *tu. Произносится с характерным немецким растягиванием гласной в открытом слоге.

Родство с современным немецким языком можно увидеть в следующей таблице:

| Язык | Выражение | Настоящее время | Прошедшее время |

|---|---|---|---|

| древнеангл. | ты любишь | thou lovest | thou lovedest |

| немецкий | ты любишь | du liebst | du liebtest |

История

В старом английском языке к слову thou применялось одно предельно простое правило: thou употребляется при обращении к одному человеку (ты), а yе(you) — к нескольким людям (вы). После завоевания норманами, которое ознаменовало собой начало влияния французской лексики, чем был отмечен средне-английский период, thou было постепенно замещено на ye(you), как форма обращения к высшему по званию, а позднее, к равному. В течение длительного времени thou оставалось наиболее часто употребительной формой для обращения к человеку низшего звания. Противопоставление единственного и множественного числа неформального и формального подтекста называется TV-различие, в английском, главным образом, из-за влияния французского языка. Все началось с того, что к королю и другим аристократам стали обращаться используя множественное число. Вскоре стало обыденным, как во французском, обращаться к человеку, занимающему более высокое положение в обществе, используя местоимение множественного числа, так как считалось вежливым. Во французском, ‘tu’ было впоследствии сочтено фамильярным и снисходительным, (а для незнакомца — возможным оскорблением), в то время как множественная форма vous сохранилась и осталась формальной.

См. также

- Формы обращения

Thou is an old-fashioned, poetic, or religious word for ‘you’ when you are talking to only one person. It is used as the subject of a verb.

Similarly, What is the archaic word of thou?

The word thou /ðaʊ/ is a second-person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in most contexts by the word you.

Additionally, Does thou mean they? the second person singular subject pronoun, equivalent to modern you (used to denote the person or thing addressed): Thou shalt not kill. (used by Quakers) a familiar form of address of the second person singular: Thou needn’t apologize.

Related Contents

- 1 What is the modern word for thou?

- 2 What does Shakespeare thou mean?

- 3 What is another word for thou?

- 4 What is the meaning of thou and thy?

- 5 What does thou mean in text?

- 6 How do you use thou and thy?

- 7 What is a synonym of thou?

- 8 What is another word for thy?

- 9 What does thee and thou mean in Shakespeare?

- 10 What is the meaning of thee thy and thou?

- 11 What are 5 words that Shakespeare invented?

- 12 Is thee and thou the same?

- 13 How do you use the word thou?

- 14 What are antonyms for thou?

- 15 What is thy in the Bible?

- 16 How do you use Thy in a sentence?

- 17 How is thou used in a sentence?

- 18 What’s another word for thou?

- 19 Is thou informal?

- 20 Where do we use thy?

- 21 How do you use thou in a sentence?

What is the modern word for thou?

the second person singular object pronoun, equivalent to modern you; the objective case of thou1: With this ring, I thee wed.

What does Shakespeare thou mean?

Shakespeare’s Pronouns

“Thou” for “you” (nominative, as in “Thou hast risen.”) “Thee” for “you” (objective, as in “I give this to thee.”) “Thy” for “your” (genitive, as in “Thy dagger floats before thee.”) “Thine” for “yours” (possessive, as in “What’s mine is thine.”)

What is another word for thou?

What is another word for thou?

| you | cha |

|---|---|

| yous | youse |

| youz | allyou |

| thee | y’all |

| ye | you all |

What is the meaning of thou and thy?

Thee, thou, and thine (or thy) are Early Modern English second person singular pronouns. Thou is the subject form (nominative), thee is the object form, and thy/thine is the possessive form.

What does thou mean in text?

The word thou, used in place of “you,” is not used much in modern language. In fact, with its Biblical feeling, it’s most often used in religious contexts. Otherwise, it might be used as slang for thousand.

How do you use thou and thy?

Thou is the subject form (nominative), thee is the object form, and thy/thine is the possessive form. thou – singular informal, subject (Thou art here. = You are here.) thee – singular informal, object (He gave it to thee.)

What is a synonym of thou?

In this page you can discover 22 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for thou, like: yourself, you, thee, thyself, ye, thine, yard, thy, 1000, wherefore and hast.

What is another word for thy?

In this page you can discover 16 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for thy, like: thee, my, that, thine, thou, for, but, ye, the wicked, doth and which.

What does thee and thou mean in Shakespeare?

In actual fact, at the time Shakespeare was writing the people of England were speaking very much as we speak today. … If you were a person of low social rank, in talking to someone of high rank you would address him/her with the words you and your, whereas he/she would use thee/thou in talking to you.

What is the meaning of thee thy and thou?

Thee, thou, and thine (or thy) are Early Modern English second person singular pronouns. Thou is the subject form (nominative), thee is the object form, and thy/thine is the possessive form. thou – singular informal, subject (Thou art here. = You are here.)