Shall and will are two of the English modal verbs. They have various uses, including the expression of propositions about the future, in what is usually referred to as the future tense of English.

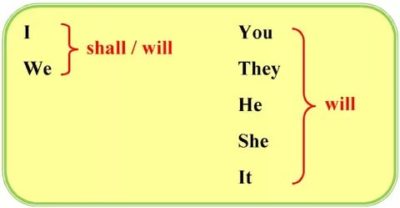

Historically, prescriptive grammar stated that, when expressing pure futurity (without any additional meaning such as desire or command), shall was to be used when the subject was in the first person, and will in other cases (e.g., «On Sunday, we shall go to church, and the preacher will read the Bible.») This rule is no longer commonly adhered to by any group of English speakers, and will has essentially replaced shall in nearly all contexts.

Shall is, however, still widely used in bureaucratic documents, especially documents written by lawyers. Owing to heavy misuse, its meaning can be ambiguous and the United States government’s Plain Language group advises writers not to use the word at all.[1] Other legal drafting experts, including Plain Language advocates, argue that while shall can be ambiguous in statutes (which most of the cited litigation on the word’s interpretation involves), court rules, and consumer contracts, that reasoning does not apply to the language of business contracts.[2] These experts recommend using shall but only to impose an obligation on a contractual party that is the subject of the sentence, i.e., to convey the meaning «hereby has a duty to.»[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Etymology[edit]

The verb shall derives from Old English sceal. Its cognates in other Germanic languages include Old Norse skal, German soll, and Dutch zal; these all represent *skol-, the o-grade of Indo-European *skel-. All of these verbs function as auxiliaries, representing either simple futurity, or necessity or obligation.

The verb will derives from Old English willan, meaning to want or wish. Cognates include Old Norse vilja, German wollen (ich/er/sie will, meaning I/he/she want/s to), Dutch willen, Gothic wiljan. It also has relatives in non-Germanic languages, such as Latin velle («wish for») and voluptas («pleasure»), and Polish woleć («prefer»). All of these forms derive from the e-grade or o-grade of Indo-European *wel-, meaning to wish for or desire. Within English, the modal verb will is also related to the noun will and the regular lexical verb will (as in «She willed him on»).

Early Germanic did not inherit any Proto-Indo-European forms to express the future tense, and so the Germanic languages have innovated by using auxiliary verbs to express the future (this is evidenced in Gothic and in the earliest recorded Germanic expressions). In English, shall and will are the auxiliaries that came to be used for this purpose. (Another one used as such in Old English was mun, which is related to Scots maun, Modern English must and Dutch moet)

Derived forms and pronunciation[edit]

Both shall and will come from verbs that had the preterite-present conjugation in Old English (and generally in Germanic), meaning that they were conjugated using the strong preterite form (i.e. the usual past tense form) as the present tense. Because of this, like the other modal verbs, they do not take the usual -s in Modern English’s third-person singular present; we say she shall and he will – not *she shalls, and not *he wills (except in the sense of «to will» being a synonym of «to want» or «to write into a will»). Archaically, there were however the variants shalt and wilt, which were used with thou.

Both verbs also have their own preterite (past) forms, namely should and would, which derive from the actual preterites of the Old English verbs (made using the dental suffix that forms the preterites of weak verbs). These forms have developed a range of meanings, frequently independent of those of shall and will (as described in the section on should and would below). Aside from this, though, shall and will (like the other modals) are defective verbs – they do not have other grammatical forms such as infinitives, imperatives or participles. (For instance, I want to will eat something or He’s shalling go to sleep do not exist.)

Both shall and will may be contracted to -’ll, most commonly in affirmative statements where they follow a subject pronoun. Their negations, shall not and will not, also have contracted forms: shan’t and won’t (although shan’t is rarely used in North America, and is becoming rarer elsewhere too). See English auxiliaries and contractions.

The pronunciation of will is , and that of won’t is . However shall has distinct weak and strong pronunciations: when unstressed, and when stressed. Shan’t is pronounced in England, New Zealand, South Africa etc.; in North America (if used) it is pronounced , and both forms are acceptable in Australia (due to the unique course of the trap–bath split).

Specific uses of shall or will[edit]

The modal verbs shall and will have been used in the past, and continue to be used, in a variety of meanings.[8] Although when used purely as future markers they are largely interchangeable (as will be discussed in the following sections), each of the two verbs also has certain specific uses in which it cannot be replaced by the other without change of meaning.

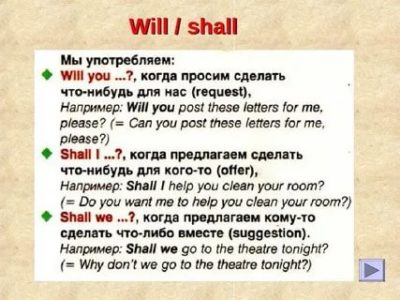

The most common specific use of shall in everyday English is in questions that serve as offers or suggestions: «Shall I …?» or «Shall we …?» These are discussed under § Questions below.

In statements, shall has the specific use of expressing an order or instruction, normally in elevated or formal register. This use can blend with the usage of shall to express futurity, and is therefore discussed in detail below under § Colored uses.

Will (but not shall) is used to express habitual action, often (but not exclusively) action that the speaker finds annoying:

- He will bite his nails, whatever I say.

- He will often stand on his head.

Similarly, will is used to express something that can be expected to happen in a general case, or something that is highly likely at the present time:

- A coat will last two years when properly cared for.

- That will be Mo at the door.

The other main specific implication of will is to express willingness, desire or intention. This blends with its usage in expressing futurity, and is discussed under § Colored uses. For its use in questions about the future, see § Questions.

Uses of shall and will in expressing futurity[edit]

Both shall and will can be used to mark a circumstance as occurring in future time; this construction is often referred to as the future tense of English. For example:

- Will they be here tomorrow?

- I shall grow old some day.

- Shall we go for dinner?

When will or shall directly governs the infinitive of the main verb, as in the above examples, the construction is called the simple future. Future marking can also be combined with aspectual marking to produce constructions known as future progressive («He will be working»), future perfect («He will have worked») and future perfect progressive («He will have been working»). English also has other ways of referring to future circumstances, including the going to construction, and in many cases the ordinary present tense – details of these can be found in the article on the going-to future.

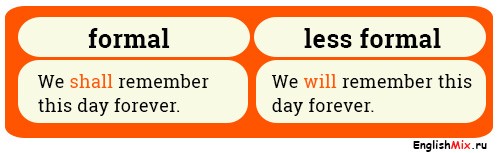

The verbs will and shall, when used as future markers, are largely interchangeable with regard to literal meaning. Generally, however, will is far more common than shall. Use of shall is normally a marked usage, typically indicating formality and/or seriousness and (if not used with a first person subject) expressing a colored meaning as described below. In most dialects of English, the use of shall as a future marker is viewed as archaic.[9]

Will is ambiguous in first-person statements, and shall is ambiguous in second- and third-person statements. A rule of prescriptive grammar was created to remove these ambiguities, but it requires that the hearer or reader understand the rule followed by the speaker or writer, which is usually not the case. According to this rule, when expressing futurity and nothing more, the auxiliary shall is to be used with first person subjects (I and we), and will is to be used in other instances. Using will with the first person or shall with the second or third person is asserted to indicate some additional meaning in addition to plain futurity. In practice, however, this rule is not observed – the two auxiliaries are used interchangeably, with will being far more common than shall. This is discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Prescriptivist distinction[edit]

According to Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage,[10] the distinction between shall and will as future markers arose from the practice of Latin teaching in English schools in the 14th century. It was customary to use will to translate the Latin velle (meaning to wish, want or intend); this left shall (which had no other equivalent in Latin) to translate the Latin future tense. This practice kept shall alive in the role of future marker; it is used consistently as such in the Middle English Wycliffe’s Bible. However, in the common language it was will that was becoming predominant in that role. Chaucer normally uses will to indicate the future, regardless of grammatical person.

An influential proponent of the prescriptive rule that shall is to be used as the usual future marker in the first person was John Wallis. In Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae (1653) he wrote: «The rule is […] to express a future event without emotional overtones, one should say I shall, we shall, but you/he/she/they will; conversely, for emphasis, willfulness, or insistence, one should say I/we will, but you/he/she/they shall».

Henry Watson Fowler wrote in his book The King’s English (1906), regarding the rules for using shall vs. will, the comment «the idiomatic use, while it comes by nature to southern Englishmen … is so complicated that those who are not to the manner born can hardly acquire it». The Pocket Fowler’s Modern English Usage, OUP, 2002, says of the rule for the use of shall and will: «it is unlikely that this rule has ever had any consistent basis of authority in actual usage, and many examples of [British] English in print disregard it».

Nonetheless, even among speakers (the majority) who do not follow the rule about using shall as the unmarked form in the first person, there is still a tendency to use shall and will to express different shades of meaning (reflecting aspects of their original Old English senses). Thus shall is used with the meaning of obligation, and will with the meaning of desire or intention.

An illustration of the supposed contrast between shall and will (when the prescriptive rule is adhered to) appeared in the 19th century,[11] and has been repeated in the 20th century[12] and in the 21st:[13]

- I shall drown; no one will save me! (expresses the expectation of drowning, simple expression of future occurrence)

- I will drown; no one shall save me! (expresses suicidal intent: first-person will for desire, third-person shall for «command»)

An example of this distinction in writing occurs in Henry James’s 1893 short story The Middle Years:

- «Don’t you know?—I want to what they call ‘live.'»

- The young man, for good-by, had taken his hand, which closed with a certain force. They looked at each other hard a moment. «You will live,» said Dr. Hugh.

- «Don’t be superficial. It’s too serious!»

- «You shall live!» Dencombe’s visitor declared, turning pale.

- «Ah, that’s better!» And as he retired the invalid, with a troubled laugh, sank gratefully back.[14]

A more popular illustration of the use of «shall» with the second person to express determination occurs in the oft-quoted words the fairy godmother traditionally says to Cinderella in British versions of the well-known fairy tale: «You shall go to the ball, Cinderella!»

Another popular illustration is in the dramatic scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring when Gandalf checks the Balrog’s advance with magisterial censure, «You shall not pass!»

The use of shall as the usual future marker[dubious – discuss] in the first person nevertheless persists in some more formal or elevated registers of English. An example is provided by the famous speech of Winston Churchill: «We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.'»

Colored uses[edit]

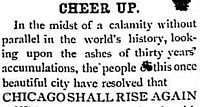

Example of shall in the lead editorial of the Chicago Tribune after the Chicago Fire, using «shall» to connote formality and seriousness.

Whether or not the above-mentioned prescriptive rule (shall for the unmarked future in the first person) is adhered to, there are certain meanings in which either will or shall tends to be used rather than the other. Some of these have already been mentioned (see the Specific uses section). However, there are also cases in which the meaning being expressed combines plain futurity with some additional implication; these can be referred to as «colored» uses of the future markers.

Thus shall may be used (particularly in the second and third persons) to imply a command, promise or threat made by the speaker (i.e. that the future event denoted represents the will of the speaker rather than that of the subject). For example:

- You shall regret it before long. (speaker’s threat)

- You shall not pass! (speaker’s command)

- You shall go to the ball. (speaker’s promise)

In the above sentences, shall might be replaced by will without change of intended meaning, although the form with will could also be interpreted as a plain statement about the expected future. The use of shall is often associated with formality and/or seriousness, in addition to the coloring of the meaning. For some specific cases of its formal use, see the sections below on § Legal use and § Technical specifications.

(Another, generally archaic, use of shall is in certain dependent clauses with future reference, as in «The prize is to be given to whoever shall have done the best.» More normal here in modern English is the simple present tense: «whoever does the best»; see Uses of English verb forms § Dependent clauses.)

On the other hand, will can be used (in the first person) to emphasize the willingness, desire or intention of the speaker:

- I will lend you £10,000 at 5% (the speaker is willing to make the loan, but it will not necessarily be made)

- I will have my way.

Most speakers have will as the future marker in any case, but when the meaning is as above, even those who follow or are influenced by the prescriptive rule would tend to use will (rather than the shall that they would use with a first person subject for the uncolored future).

The division of uses of will and shall is somewhat different in questions than in statements; see the following section for details.

Questions[edit]

In questions, the traditional prescriptive usage is that the auxiliary used should be the one expected in the answer. Hence in enquiring factually about the future, one could ask: «Shall you accompany me?» (to accord with the expected answer «I shall», since the rule prescribes shall as the uncolored future marker in the first person). To use will instead would turn the question into a request. In practice, however, shall is almost never used in questions of this type. To mark a factual question as distinct from a request, the going-to future (or just the present tense) can be used: «Are you going to accompany me?» (or «Are you accompanying me?»).

The chief use of shall in questions is with a first person subject (I or we), to make offers and suggestions, or request suggestions or instructions:

- Shall I open a window?

- Shall we dance?

- Where shall we go today?

- What shall I do next?

This is common in the UK and other parts of the English-speaking world; it is also found in the United States, but there should is often a less marked alternative. Normally the use of will in such questions would change the meaning to a simple request for information: «Shall I play goalkeeper?» is an offer or suggestion, while «Will I play goalkeeper?» is just a question about the expected future situation.

The above meaning of shall is generally confined to direct questions with a first person subject. In the case of a reported question (even if not reported in the past tense), shall is likely to be replaced by should or another modal verb such as might: «She is asking if she should open a window»; «He asked if they might dance.»

The auxiliary will can therefore be used in questions either simply to enquire about what is expected to occur in the future, or (especially with the second person subject you) to make a request:

- Where will tomorrow’s match be played? (factual enquiry)

- Will the new director do a good job? (enquiry for opinion)

- Will you marry me? (request)

Legal and technical use[edit]

US legal system[edit]

Bryan Garner and Justice Scalia in Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts describe that some legal drafting has sloppy use of the word «shall».[15]: 1808 Nevertheless, Garner and Scalia conclude that when the word «shall» can reasonably be understood as mandatory, it ought to be taken that way.[15]: 1849 In 2007 the U.S. Supreme Court said («The word `shall’ generally indicates a command that admits of no discretion on the part of the person instructed to carry out the directive»); Black’s Law Dictionary 1375 (6th ed. 1990) («As used in statutes … this word is generally imperative or mandatory»).[16]

Legislative acts and contracts sometimes use «shall» and «shall not» to express mandatory action and prohibition. However, it is sometimes used to mean «may» or «can». The most famous example of both of these uses of the word «shall» is the United States Constitution. Claims that «shall» is used to denote a fact, or is not used with the above different meanings, have caused discussions and have significant consequences for interpreting the text’s intended meaning.[17] Lawsuits over the word’s meaning are also common.[1]

Technical contexts[edit]

In many requirement specifications, particularly involving software, the words shall and will have special meanings. Most requirement specifications use the word shall to denote something that is required, while reserving the will for simple statement about the future (especially since «going to» is typically seen as too informal for legal contexts). However, some documents deviate from this convention and use the words shall, will, and should to denote the strength of the requirement. Some requirement specifications will define the terms at the beginning of the document.

Shall and will are distinguished by NASA[18] and Wikiversity[19] as follows:

- Shall is usually used to state a device or system’s requirements. For example: «The selected generator shall provide a minimum of 80 Kilowatts.»

- Will is generally used to state a device or system’s purpose. For example, «The new generator will be used to power the operations tent.»

On standards published by International Organization for Standardization (ISO), IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission), ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials), IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), requirements with «shall» are the mandatory requirements, meaning, «must», or «have to».[20] The IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) defines shall and must as synonymous terms denoting absolute requirements, and should as denoting a somewhat flexible requirement, in RFC documents.[21]

On specifications and standards published by the United States Department of Defense (DoD), requirements with «shall» are the mandatory requirements. (“Must” shall not be used to express mandatory provisions. Use the term “shall.”) “Will” declares intent or simple futurity, and “should” and “may” express nonmandatory provisions.[22][23][24]

Outside DoD, other parts of the U.S. government advise against using the word shall for three reasons: it lacks a single clear meaning, it causes litigation, and it is nearly absent from ordinary speech. The legal reference Words and Phrases dedicates 76 pages to summarizing hundreds of lawsuits that centered around the meaning of the word shall. When referencing a legal or technical requirement, Words and Phrases instead favors must while reserving should for recommendations.[1]

Should and would[edit]

As noted above, should and would originated as the preterite (past tense) forms of shall and will. In some of their uses they can still be identified as past (or conditional) forms of those verbs, but they have also developed some specific meanings of their own.

Independent uses[edit]

The main use of should in modern English is as a synonym of ought to, expressing quasi-obligation, appropriateness, or expectation (it cannot be replaced by would in these meanings). Examples:

- You should not say such things. (it is wrong to do so)

- He should move his pawn. (it is appropriate to do so)

- Why should you suspect me? (for what reason is it proper to suspect me?)

- You should have enough time to finish the work. (a prediction)

- I should be able to come. (a prediction, implies some uncertainty)

- There should be some cheese in the kitchen. (expectation)

Other specific uses of should involve the expression of irrealis mood:

- in condition clauses (protasis), e.g. «If it should rain» or «Should it rain»; see English conditional sentences

- as an alternative to the subjunctive, e.g. «It is important that he (should) leave»; see English subjunctive

The main use of would is in conditional clauses (described in detail in the article on English conditional sentences):

- I would not be here if you hadn’t summoned me.

In this use, would is sometimes (though rarely) replaced by should when the subject is in the first person (by virtue of the same prescriptive rule that demands shall rather than will as the normal future marker for that person). This should is found in stock phrases such as «I should think» and «I should expect». However its use in more general cases is old-fashioned or highly formal, and can give rise to ambiguity with the more common use of should to mean ought to. This is illustrated by the following sentences:

- You would apologize if you saw him. (pure conditional, stating what would happen)

- You should apologize if you see him. (states what would be proper)

- I would apologize if I saw him. (pure conditional)

- I should apologize if I saw him. (possibly a formal variant of the above, but may be understood to be stating what is proper)

In archaic usage would has been used to indicate present time desire. «Would that I were dead» means «I wish I were dead». «I would fain» means «I would gladly».

More details of the usage of should, would and other related auxiliaries can be found in the article on English modal verbs.

As past of shall and will[edit]

When would and should function as past tenses of will and shall, their usage tends to correspond to that of the latter verbs (would is used analogously to will, and should to shall).

Thus would and should can be used with «future-in-the-past» meaning, to express what was expected to happen, or what in fact did happen, after some past time of reference. The use of should here (like that of shall as a plain future marker) is much less common and is generally confined to the first person. Examples:

- He left Bath in 1890, and would never return. (in fact he never returned after that)

- It seemed that it would rain. (rain was expected)

- Little did I know that I would (rarer: should) see her again the very next day.

Would can also be used as the past equivalent of will in its other specific uses, such as in expressing habitual actions (see English markers of habitual aspect#Would):

- Last summer we would go fishing a lot. (i.e. we used to go fishing a lot)

In particular, would and should are used as the past equivalents of will and shall in indirect speech reported in the past tense:

- The ladder will fall. → He said that the ladder would fall.

- You shall obey me! → He said that I should obey him.

- I shall go swimming this afternoon. → I said that I should go swimming in the afternoon.

As with the conditional use referred to above, the use of should in such instances can lead to ambiguity; in the last example it is not clear whether the original statement was shall (expressing plain future) or should (meaning «ought to»). Similarly «The archbishop said that we should all sin from time to time» is intended to report the pronouncement that «We shall all sin from time to time» (where shall denotes simple futurity), but instead gives the highly misleading impression that the original word was should (meaning «ought to»).

See also[edit]

- English verbs

- Grammatical person

- Verbs in English Grammar (wikibook)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «Shall and must». plainlanguage.gov. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Kenneth Adams, «Making Sense of ‘Shall'», New York Law Journal, October 18, 2007.

- ^ Chadwick C. Busk, «Using Shall or Will to Create Obligations in Business Contracts», Michigan Bar Journal, pp. 50-52, October 2017.

- ^ «Basic Concepts in Drafting Contracts», presented by Vincent R. Martorana to the New York State Bar Association, December 10, 2014 (via Reed Smith University).

- ^ http://apps.americanbar.org/buslaw/newsletter/0052/materials/pp3.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1162&context=transactions

- ^ https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Tips-for-Achieving-Clarity-in-Contract-Drafting.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Many of the examples are taken from Fowler, H. W. (1908). The King’s English (2nd ed.). Chapter II. Syntax — Shall and Will. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ Crystal, David, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, pages 194 and 224, Cambridge Press Syndicate, New York, NY 1995 ISBN 0-521-40179-8

- ^ Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage, Merriam-Webster, 1989, ISBN 0-87779-132-5

- ^ «Reade and Collins». The Virginia University Magazine. 1871. p. 367.

- ^ Allen, Edward Frank (1938). How to write and speak effective English: a modern guide to good form. The World Syndicate Publishing Company.

«I will drown, no one shall save me!»).

- ^ Graham, Ian (2008). Requirements modelling and specification for service oriented architecture. p. /79. ISBN 9780470712320.

- ^ Henry James. The Middle Years.

- ^ a b Scalia, Antonin; Garner, Bryan A. (2012). «11. Mandatory/Permissive Canon». Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (Kindle ed.). St. Paul, MN: Thomson West. ISBN 978-0-314-27555-4.

- ^ National Ass’n v. Defenders of Wildlife, 127 S. Ct. 2518, 2531-2532 (US 2007)..

- ^ Tillman, Nora Rotter; Tillman, Seth Barrett (2010). «A Fragment on Shall and May«. American Journal of Legal History. 50 (4): 453–458. doi:10.1093/ajlh/50.4.453. SSRN 1029001.

- ^ NASA document Archived December 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Writing Clear Requirements», in Technical writing specification, Wikiversity

- ^ «ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2» (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ^ «RFC 2119». Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ^ «Defense and Program-Unique Specifications Format and Content, MIL-STD-961». 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- ^ «Defense Standards Format and Content, MIL-STD-962». 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- ^ «Writing Specifications». Retrieved 2018-05-15.

External links[edit]

Look up will in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Look up shall in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- On the Use of the Verbs shall and will. By Professor De Morgan

- On the Use of Shall and Will. By Hensleigh Wedgwood, Esq.

- «Shall and Will». Fowler, H. W. 1908. The King’s English — thorough discussion on the subject

- Complete descriptions of the English Tenses

- Webster 1913 — Entry for Shall

- «The Origins of some Prescriptive Grammar Rules» — quoting The Origins and Development of the English Language, Pyles and Algeo, 1993

- The Rise of Prescriptivism in English (PDF format)

Modal verb Shall in English: use cases, examples, forms, difference

Traditionally, the modal verb Shall in English has been used with the pronouns I / We to express future actions, just like the auxiliary verb Will. Modern English now only uses will.

In colloquial speech, perhaps the English still use shall as an auxiliary verb, but one way or another, the language is changing, and even the British agree that it is no longer on a par with will.

Today you will learn in what cases this modal verb is used, how sentences are built with it and take a test to test your knowledge.

Forms of formation of the modal verb Shall

This modal verb is used without the to particle and is pronounced [ʃæl], in the negative form the transcription looks like this [ʃɑːnt].

Let’s see how sentences are constructed with this modal verb:

Affirmative sentences

In statements, we put it after the subject:

— I shall talk to him tomorrow. — I’ll talk to him tomorrow.

Obviously, this word is not used with other modal verbs, but you can use it with need to / be able to / have to:

— I have good news! I shall be able to visit my parents in Spain! — I have good news! I can visit my parents in Spain!

Negative sentences

In negations, remember the not particle:

— I shan’t be able to visit my parents. — I won’t be able to visit my parents.

The full form is used in formal situations or when we want to emphasize something. Native speakers rarely use negative structure.

In questions, the verb is swapped with the subject:

— Shall we meet for lunch? “Shouldn’t we meet for lunch?”

Last but not least, Shall is used in separation issues:

— I’ll drive you home, shall I? — I’ll take you home, okay?

Use cases for the modal verb Shall

Shall is never a purely modal verb. It always combines modal meaning with the function of an auxiliary verb for the future tense.

This verb is still used to formulate a commitment with a second and third person in the singular and plural, but it is not common in this sense in colloquial English.

Its use is usually limited to the formal or even archaic style and is found mainly in subordinate clauses, where it is structurally dependent:

Source: https://englishmix.ru/grammatika/modalnye-glagoly/modalnyj-glagol-shall

Don’t Americans say «shall»?

There is a legend of a Scottish man living in London. He didn’t know how to use SHALL and WILL, he was drowning and he shouted:

“I will die, no one shall save me” instead of “I shall die, no one will save me”.

And he died because of that.

You get the joke?

If you have ever studied classical, correct English, then you understand what the salt is But in general, this anecdote is two hundred years old, so even if you do not understand, do not be discouraged.

For many Americans shall practically non-existent… Even 18 years ago, when I was in school, we were already warned that shall has long been outdated and lost its position in colloquial speech.

Later I became convinced of this: in 95% of cases, Americans do not use shall… Therefore, to all my students, I said: » shall… Just speak will».

Hall with all its subtleties — really a feature of the British. One old cartoon made fun of formality shall:

«Shall we?» — «Let’s shall!»

However, it cannot be argued that Americans do not use shall never. Let’s put an end to the question “When do Americans say shall?»

The most typical use case shall — a proposal to do something together. There are two options:

1) Shall we go now? — Well, let’s go already?

Shall we go for a walk? — Let’s go for a walk?

Shall we go to the movies? — Let’s go to the movies?

Shall we dance? — Well, let’s dance?

2) Are you ready? Let’s go, shall we? — Are you ready? Then we go?

Let’s dance, shall we? — Shall we dance?

Let’s get started, shall we? — Let `s start?

Note that all of these questions are assumed to be answered yes. Thanks to shall/shallwe? the question doesn’t sound so assertive (compare to “Let’s go! Let’s get started!”).

Hall softens these suggestions. Many Americans even say they do shallwhen they want to show gallantry and special courtesy.

However, there is one big «but». Hall sounds archaic, whatever one may say. Therefore, Americans are more likely to choose more casual expressions:

Let’s get started, okay?

Alright, let’s get started.

Do you wanna go?

Why don’t we go to the movies?

How about going out tonight?

Wanna eat out?

Shall vs. should

In principle, shall can occur in sentences like:

HallIhelpyouWithThat? — I (should / should) help you with this?

What shall I do? — What should I do? What do i do?

Whereshallwego? — Where should we (should) go?

These sentences sound normal, but even in these cases, Americans are much more willing to say shouldntAnd not shall.

Hall forspecialcases

Sometimes Americans use shallto emphasize your unwavering determination to do something.

For example, if a politician is asked whether he will do what he promises, he may well answer: “I will, and I shall”. That is, «Yes, and I declare that I am determined to do this, and I will do my best.»

Can be found shall

Source: http://fluenterra.ru/english/english-grammar/americans-dont-say-shall.php

Enjoy learning English online with Puzzle English for free

Difference between shall и will not striking — they both can serve to form the future tense and even replace each other. But since these verbs are modal, they are not so simple with them. Of course, the first thing that comes to mind in connection with will и shall Is the future tense. But they can also contribute to the expression of intention or obligation.

Cases of bygone days

Long ago, before smartphones were invented (like the internet and television), English grammar was more or less orderly.

Traditional rules prescribed the use of shall with the first person (I — I и we — we), in the event that it was necessary to form the future tense without additional meanings. With the rest of the faces it was possible to use will.

It looked something like this:

I shall meet Miss Edwards tomorrow. I’ll see Miss Edwards tomorrow.

We shall stay in London. We will be staying in London.

Miss edwards will be delighted. Miss Edwards will be delighted.

They will meet us at the station. They will meet us at the train station.

If will was used in the first person, then it expressed the idea of aspiration, decisiveness.

I will speak to Miss Edwards about her dog digging up my flower bed! I’ll talk to Ms. Edwards about her dog digging my flower bed!

We will definitely solve this problem. We will definitely solve this problem.

When this confidence in future action was projected onto someone else (second or third person), then it was used shall:

you shall obey me. You will obey me.

Margarete shall help you with that. Margaret will definitely help you with this.

And in fact,

Now we have to reveal all the cards and admit that these rules have not been observed by anyone for a long time. English speakers are fluent in both verbs with any person. The main thing to remember is will is used many times more often than shall.

Although there is at least one case where knowing the old rules will come in handy: if you love classical English literature and want to read it in the original.

Alice, the one who ended up in Wonderland, constantly uses shall with the first person and will — with other persons. After all, she was an educated English girl from a good family.

I shall be punished for it now, by being drowned in my own tears! That will be a queer thing, to be sure! Now, as a punishment, I will also drown in my own tears! It will really be strange!

I do hope it will make me grow large again. I hope this helps me grow again.

Abridged version

In colloquial speech, you don’t have to worry about which verb to put — you can just use contractions after pronouns. Who knows which verb is hidden behind two letters «l«?

I‘ll be there at 6. I’ll be there at six.

They‘ll come over for dinner. They will stop by for dinner.

True, there is still a difference in reducing negatives: «will not « becomes won’t, a «shall not « turns into shan’t. True, this last version is extremely rarely used in America, and it can be heard less and less on other continents.

Will (shall) — the difference is there still?

Yes, there are cases when only will or only shall… Let’s take them apart!

Although the verb shall is rapidly falling out of use as an indicator of the future tense, nevertheless, in some values it has become entrenched.

- For example, when you suggest something to someone or ask a clarifying question, you can start the sentence with shall, or put it at the end:

Hall I help you? Can I help you?

Let’s go, shall we? Let’s go to?

End «Shall we?» in the last example, it expresses a certain impatience and even, to some extent, authoritarianism. This is a more formal alternative to the ending «Okay?» which is put when we expect consent from the interlocutor.

Compare:

Let’s just do it, okay? Let’s just do it, ok?

Source: https://puzzle-english.com/directory/will-or-shall

Future in English: future simple, is it necessary and when to use going to

«Grammar» The Times » Future in English: future simple, is it necessary and when to use going to

Future. Everything that hasn’t happened yet, but will happen at any point in time after now. Interestingly, in some languages, for example, in Chinese, there is no future tense — you have to say something like «I’ll go tomorrow.» In English, the future tense, of course, is and it is, moreover, one of the simplest. The future tense is formed by adding will to any verb. However, English would not be English, if it had not thrown in exceptions and nuances here too — they will be discussed.

How Future Simple is formed

If you need to build a sentence in the future, all you need to do is put the particle will in front of the verbs. And that’s all.

I will go. You will do it. John will come. I will go. You do. John will come. It couldn’t be easier, right?

‘ll

Well, or almost nowhere. And here the first difficulty awaits you. In the case when will stands after the pronoun, it is often shortened to ‘ll, that is, I will becomes I’ll, you will — you’ll, he will — he’ll, and so on.

This shouldn’t be a problem when reading; but in spoken language, especially if you are just starting to learn English, this is something worth paying attention to. ‘ll in the colloquial speech of a native speaker can be completely invisible, it literally slips between the pronoun and the verb.

In fluent speech, words will, as it were, flow into each other along the way for a moment, flowing into ‘ll.

But what about shall?

Here, especially if there are students in the classroom who got their first idea of the future tense in English back in Soviet school, they might be surprised. «If the subject in the sentence is I or we, then the verb shall is used to form the future tense.» I don’t know about you, but that’s how I was taught in the 5th grade.

Here the Soviet textbook, to put it mildly, is not entirely right. In all cases, will is used, and it doesn’t matter what face the subject has in the sentence: I will, you will, he will. That’s all. Another classic of English literature Chaucer in the 14th century used will for all pronouns and did not worry about what Soviet textbooks thought about it.

When to use shall

At the same time, I do not want to say at all that the British sent shall to the dustbin of history. If you have more or less sorted out with will, let’s take a look at the cases where shall is quite appropriate.

Shall as the force of circumstance

To begin with, shall and will, although both mean «something will happen in the future,» have a more subtle connotation in their meanings.

Will has a tint of desire, intentions to do something: “I want and will do”, “he wants and will do”. Hallon the other hand, it is, rather, «force majeure circumstances», «something that should happen.» A classic example from English grammar:

I shall drown; no one will save me! I will drown (and this circumstance is stronger than me) and no one will save me (because no one wants or can save me)

Now let’s turn this phrase the other way.

I will drown; no one shall save me! I will drown (and here we have a shade of suicide — I want to drown!), And no one will save me (do not come and do not try to save me!).

In fairness, it should be noted that this nuance — the desire for will and the circumstances for shall are gradually leaving the English language. But the next feature of the verb shall, which we will now talk about, is manifested even more.

Shall as a modal verb

Source: https://englishexplained.ru/future-simple-and-going-to/

Shall and will: usage rules and differences from other modal verbs

By Natalia October 3, 2018

Modal verbs act as auxiliary verbs, carry a number of different semantic loads. All these rules have their own logical thread, remembering which, you will forever remember the features of shall, will, must, have to, should, ought to, would and others.

Basic concept of modality

Modal verbs perform the function of helping one word to another, fill a bunch of words with meaning.

I should go to work. — I have to go to work.

What happens if you remove should?

I go to work. — I go to work.

The meaning has changed. It is for the correct presentation of thoughts that modal verbs serve.

There are 8 main verbs that obey a number of rules, and 5 words that are not modal, but fit some of these rules.

Basic modal verbs are easy to remember:

MMM — must, may, might;

WW — will, would;

CC — can, could;

SS — shall, should.

Side:

- ought to, need, have to, be able to (for use in the past tense of opportunity verbs);

- used to (denoting an action that was performed before but is not being performed now).

Basic rules for modal verbs:

- You can’t put s to them. Never. Forget about it. We are used to: She speaks English well. — She speaks to him. With a modal verb of opportunity: She might speak English well. — She could speak English well.

- In questions, they behave in the same way as a regular auxiliary verb: Is he leaving now? — Is he leaving now? And now the verb of opportunity: Could I leave now? — Can I get out now?

- We use the modal verb first, and then the not particle and then the infinitive. In general, the principle is the same as in the second rule.

Shall and will before and now

English is very plastic or flexible. Every day he changes and adapts to people. This is how the Future Simple or Future Indefinite tense rule has changed.

Source: https://eng911.ru/rules/grammar/shall-will.html

Auxiliary verbs in English

The topic of service and auxiliary verbs is quite difficult for those who have started learning English. Not all service verbs have an equivalent in Russian. However, of course, for the English, helper verbs are natural and important. Such verbs have no meaning, and in statements they are only part of the predicate. Next, we will take a closer look at what it means, service verb and find out why we need helper verbs.

What is an auxiliary verb in English

Service verbs are words that, in terms of vocabulary, do not have an individual meaning. These helper verbs serve as support for action verbs. Their main function is to help build a sentence correctly with a complex verb form. These verbs are used when you need to express the number, gender, or time period of an action.

Remember, individual verbs from this topic can be used as basic ones, for example: tobe, toHave, todo.

In addition, in many cases to be is used in combinations as a linking verb, and will и shall — can occur as modal verbs.

Although these verbs are not translated into Russian, they serve as multifunctional helpers in British sentences.

Consider these examples:

- He is at work now. — He’s at work now.

- You were busy and didn’t notice us. — You were busy and did not notice us.

- She runs here every morning. — She runs here every morning.

- I have finished my project. — I finished the project.

Etcarrangements сverb activity:

- I’m a blogger. — I’m a blogger.

- You have to study. –You will have to learn.

- I do believe you. — I really believe you.

How many service verbs are there?

Let’s look at what service verbs are and what each of them means. There are only five verbs — helpers:

- to do

- to be

- to have

- shall (should)

- will (would)

The first three service verbs are used most often: be, do, Have… Special attention should be paid to these verbs. The reasons are as follows:

- These verbs are used most often.

- They are «two-faced» — they can take the form of both an action verb and a service verb.

- Verbs be, do, Have mutated by faces.

- Each of them has an abbreviated form.

To be, to be and to have easily change shape. All forms of these verbs in the present tense are shown in the table:

| Pronoun | to do | to be | to have |

| I | do | am | Have |

| He, She, It | does | is | has |

| They, we, you | do | are | Have |

In the past tense, the form changes only for the verb tobe:

- What: I, he, she, it

- Were: They, we, you

The service verbs to have and to do in the past tense, in accordance with the rules, in all persons form the form did and had.

Will, shall, should, would — verbs that do not change by faces.

Verb to be

Be Is the most commonly used verb in English. This is just one verb, which has a special form in different persons and numbers. This verb can serve as a connecting link, used as a service verb, or express an action. Verb be sentences can be translated as «Appear» и «be», when used as an action verb.

Affirmative sentences and questions with to be:

- I have to be at work today. — I have to be at work today.

- I need to go now. — I have to go.

- Do you want to be our guest? — Would you like to be our guest?

Source: https://englishfun.ru/grammatika/glagol/vspomogatelnye-glagoly-v-anglijskom-yazyke

Future tense with Will / Shall 1 (Future simple)

We use I’ll (= I will) when we decided to do something at the time of speech:

- Oh, I’ve left the door open. I’ll go and shut it.

- ‘What would you to drink?’ ‘I’ll have an orange juice, please. ‘

- ‘Did you phone Lucy?’ ‘Oh no, I forgot. I’ll phone her now. ‘

You cannot use the present simple (I do / i go and others) in these sentences:

- I‘ll go and shut the door. (not I go and shut)

We often use I think I’ll и I don’t think I’ll :

- I feel a bit hungry. I think I’ll have something to eat.

- I don’t think I’ll go out tonight. I’m too tired.

In spoken English, negation will usually is won’t (= want not):

- I can see you’re busy, so I won’t stay long.

Do not use willwhen you talk about something you have already decided or planned to do (see lessons 19, 20):

- I‘m going on holiday next Saturday. (not I’ll go)

- Are you working tomorrow? (not will you work)

We often use will in the following situations:

Suggesting to do something

- That bag looks heavy. I’ll help you with it. (not I help)

Agreeing to do something

- A: Can you give Tim this book?

B: sure I’ll give it to him when I see him this afternoon.

Promising to do something

- Thanks for lending me the money. I’ll pay you back on Friday.

- I won’t tell anyone what happened. I promise.

Asking someone to do something (will you ?)

- will you please turn the stereo down? I’m trying to concentrate.

You can use won’twhen someone refuses to do something:

- I’ve tried to give her advice, but she won’t listen… (in Russian: does not listen; in English: will not listen)

- The car won’t start… (= car ‘refuses’ to start)

Shall I? Shall we?

More often shall used in questions shall I ? / shall we ?

We use shall I ? / shall we ? to ask someone’s opinion, especially about suggestions or suggestions:

- Shall i open the window? (= Should I open a window? = Do you want me to open a window? Offer)

- I’ve got no money. What shall I do? (= What should I do? = What do you suggest? (For me to do) suggestion)

- ‘Shall we go? ‘ ‘Just a minute. I’m not ready yet. ‘

- Where shall we go this evening?

Compare shall I ? and will you ?:

- Shall i shut the door? (= Do I close the door? = Do you want me to close the door?)

- will you shut the door? (= Will you close the door? = I want you to close the door.)

Continued in the next lesson.

Exercises

1. Complete the sentences with I’ll + a suitable verb.

2. Read the situations and write sentences with I think I’ll or I don’t think I’ll.

3. Check the box for the correct option. (If necessary, repeat lessons 19, 20)

4. What would you say in these situations? Write sentences with shall I? or shall we?

Only registered users can add comments.

New VK comments need to be written in the blue block to the right of this. In this block, your comments will be lost.

Why VK comments are divided into old and new, as well as answers to other frequently asked questions, you will find on the FAQ page (from the top main menu).

Source: https://lingust.ru/english/grammar/lesson21

Jyoti Sagar

“Shall” is an interesting and peculiar word. Why would I describe a five-letter, commonplace, monosyllabic word like that?

Shall is a peculiar word because it is the most frequently used modal verb in legal drafting.

In English grammar, shall is one of the “modal verbs” (also called “helping verbs”) like can, will, could, shall, must, would, might, and should. The purpose of a modal verb is to add meaning to the main verb in a sentence by expressing possibility, ability, permission, or obligation. For example, “You must complete this task on time”; “He might be the inspiration for my life”; “The doctor can see you now”. “Shall” is an interesting word because in ordinary English, it is the least used modal verb. The most common ones are will, may, can, should, and would.

“Shall” dominates legal drafting

Usage of ‘shall’ in English-speaking

For long, shall has been a favourite of lawyers. Its use in legislation and in legal documents is all pervasive. As a young lawyer, one of the first things drilled into me was that “shall” is the most important modal verb to refer to future action and is the word to be used when imposing a mandatory obligation. So, I was told to imagine substitution of “shall” in a sentence with the words “has a duty to”. For example, “the Company shall deliver 100 widgets within 90 days”, indicates the intent that — “the Company has a duty to deliver …”. It read perfect.

But many a time, this yardstick did not work, as the intended meaning got distorted, and confused. For example, if the substitution rule is applied in the sentence: “The employee shall be reimbursed all expenses”, you would get: “The employee has a duty to be reimbursed all expenses”. This created ambiguity for the simple reason that the intent appeared to state an entitlement of the employee and not to impose a duty on the employee. To correctly state the intent, the sentence could simply have read “The employee is entitled to the reimbursement of expenses”.

Take a typical governing clause in an agreement which typically reads: “This Agreement shall be governed by the law of India.” If “shall” is considered to mean “has a duty to”, the sentence would read: “This Agreement has a duty to be governed by the law of India.” The intended meaning is not to impose any obligation, but it is to state a fact. When I questioned why we would not simply say “This Agreement is governed by the law of India”? I was told to just follow the rule – shall is king!

“Shall” is used indiscriminately in legal drafting

From a modest beginning in legal drafting as a modal verb describing a mandatory obligation of the subject (the person performing the action of the sentence), shall rapidly spreads like a dreaded virus through indiscriminate use – in contexts different from just those which impose a duty. Here are some examples of different contexts in which “shall” is frequently used in language of the law:

-

To impose a duty (“The Company shall maintain quality standards…”)

-

To grant a right (“The Buyer shall have the right to cancel the purchase transaction…”)

-

To give a direction (“The shipment of the products from the port shall be deemed as delivery of the products to the purchaser.”)

-

To negate a duty or discretion (“The Company shall not be required to produce copy of the specifications.”)

-

To negate a right (“Such statement shall be deemed to be correct and shall be binding on the Applicant.”)

-

To express intention (“The manufacturing plant when established shall be deemed to be part of the assets of the joint venture.”)

-

To create a condition subsequent (“If the products shall not have been delivered on or before December 31, 2020, then this purchase order shall stand cancelled.”)

-

To state or declare a fact (“Company shall mean ABC Limited.”)

-

To express the future (“This Agreement shall terminate on the sale of the warehouse.”)

“Shall” changes its meaning more than a chameleon changes colour; thus, it has large potential to violate basic principles of drafting

Black’s Law Dictionary lists the following five meanings of shall:

shall, vb.

1. “Has a duty to; more broadly, is required to “the requester shall send notice” “notice shall be sent”. This is the mandatory sense that drafters typically intend and that courts typically uphold.

2. Should (as often interpreted by courts) “all claimants shall request mediation”.

3. May “no person shall enter the building without first signing the roster”. When a negative word such as not or no precedes shall (as in the example in angled bracket), the word shall often means may. What is being negated is permission, not a requirement.

4. Will (as a future tense verb) “the corporation shall then have a period of 30 days to object”.

5. Is entitled to “the secretary shall be reimbursed for all expenses”.

Two basic principles of drafting are:

(i) A word used repeatedly in a document is presumed to bear the same meaning throughout, and

(ii) avoid using the same word or term in more than one sense. When a word takes on too many senses and cannot be confined to one sense or meaning in a document, it becomes redundant to the drafter and to the reader .

To put it differently, a good draftsperson always expresses the same idea in the same way and always expresses different ideas differently. And she makes sure that each recurring word or term has been used consistently. With minor exceptions (that is where it is used to truly describe a duty of the first person subject of the verb), “shall” usage in the language of the law violates these basic principles.

Lawyer’s habit of “future tense” writing creates further confusion

Another peculiarity of legal writing is that lawyers tend to write in the future tense and liberally deploy shall for that purpose. Here are two typical “future tense” examples from an agreement:

“Company” shall mean ABC Limited, a company registered under …

If the Buyer shall learn that the Seller shall have leased the property ….

Shall here is used in the futurity context (note that if we apply the “has a duty to” rule – the text would become laughable. For example: “If Buyer has a duty to learn that the Seller has the duty to have leased the property…).

Written in present tense, we eliminate the shalls. In present tense, the text reads:

“Company” means ABC Limited, a company registered under …

If the Buyer learns that the Seller has leased the property ….

Why do lawyers not write in the present tense? One explanation is that the lawyer believes that she is writing for the future and therefore she should write about things as if they will occur in the future! But that is a wrong premise. The usual interpretation rule is that a document speaks constantly. And when a document is read in the future (for example, when its terms are being implemented), by that time the future will be then present! So, it makes more sense to draft in the present tense and get rid of unnecessary shalls which confuse the meaning.

Thus, contrary to lawyers’ belief, shall does not have a single firm meaning

Contrary to our belief, shall does not, even remotely, have a settled firm meaning. Because of its inconsistent use in contexts other than casting a duty, shall has been interpreted by the various courts to mean “must”, “should”, “will”, “may” or “is”.

Shall is one of the most corrupted and litigated words in the language of the law. Over 100 pages in the encyclopaedia of Words & Phrases are devoted to a summary of more than 1,300 precedents from common law jurisdictions interpreting shall! This misuse or abuse of shall extends to legislation and private legal documents in equal abundance.

Courts struggle to interpret shall

Courts from jurisdictions all over the common law world have struggled to interpret shall. Here are a few examples from the Supreme Court of India.

-

In State of UP v. Manbodhan Lal Srivastava, while examining the terms of Article 320, the Court observed,

“….the use of the word «shall» in a statute, though generally taken in a mandatory sense, does not necessarily mean that in every case it shall have that effect….”

-

In Khub Chand v. State of Rajasthan, the Court held:

“Doubtless, under certain circumstances, the expression «shall» is construed as «may». The term «shall» in its ordinary significance is mandatory … unless such an interpretation leads to some absurd or inconvenient consequences…..”

-

In State of Punjab v. Shamlal Murari, the Court opined:

“The use of “shall” – a word of slippery semantics – in a rule is not decisive…..»

Here are a few precedents of the US Supreme Court, some going back 150 years:

-

A legislative amendment from “shall” to “may” had no substantive effect. (Moore v. Illinois Central Railroad Company)

-

If the government bears the duty, the word “shall” when used in statutes is to be constructed as “may”, unless a contrary intention is manifest (Railroad Co v. Hecht)

-

“Shall” means “must” for existing rights, but that it need not be construed as mandatory when a new right is created (West Wisconsin Railway Company v. Foley)

Shall is recognized as an ambiguous word and drafters are avoiding its use in many jurisdictions

Shall is an ambiguous and confusing word. Most of its usage in legal documents is inappropriate and imprecise. It is also not much used in contemporary language. Drafters in many common law jurisdictions are adopting “shall-less” style. Here are some examples of shall-less drafting from the United States of America, Australia, United Kingdom, and South Africa.

• US Federal Government’s Style Subcommittee decided to abandon ‘shall’

• US Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and of Criminal Procedures have been restyled to be ‘shall-less’

• US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure restyled – without any shalls

• The restyled Federal Rules of Evidence became effective with no ‘shall’

The Plain English Manual released by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, Australia notes that while the traditional style uses ‘shall’ for the imperative, the word is ambiguous, as it can also be used to make a statement about the future. The Manual recommends:

• Use “must” or “must not” when imposing an obligation, instead of ‘shall’ or ‘shall not’

• If you feel the need to use a gentler form, say “is to” or “is not to”, but these are less direct and use more words.

• We shouldn’t feel any compunction in using “must” and “must not” when imposing obligations and prohibitions.

Joseph Kimble in A Modest Wish for Legal Writing

The Australian Corporation Tax Act, 2009 does not have ‘shall’ in its substantive provisions.

The UK Office of Parliamentary Counsel’s Drafting Techniques Group has a published policy on ‘shall’ which prescribes the minimum use of the legislative ‘shall’.

The rewritten South African Constitution is completely “shall less”. ‘Shall’ has been replaced by ‘must’ or by the present tense, wherever, ‘shall’ appeared as an expression of futurity in the earlier, interim Constitution.

Replacement of ‘shall’ in interim South African constitution

Let us banish shall from legal writing

Shall is an overworked, outdated, and largely misused word in legal writing and should be avoided. We lawyers will be hard put to use it correctly or consistently. It is best to dump it altogether in the heap of outdated words. Simple convention could be adopted where we use the correct and most appropriate modal verb in our writing. Further, writing in present tense helps. It also helps to revise the text to avoid use of shall. Here is the suggested way forward of using modal words other than shall and of avoiding use of shall in different contexts:

Avoiding use of ‘shall’

Why remain “shall” shocked? Make your writing crisper, clearer, and better by using a contextually more appropriate modal verb in place of the troubled and troublesome “shall. Try it.

The author is the Chairman & Founder of J Sagar Associates, Advocates & Solicitors.

Традиционно модальный глагол Shall в английском языке использовался с местоимениями I/We для выражения будущих действий, как и вспомогательный глагол Will. В современном английском теперь используется только will. В разговорной речи, возможно, англичане все еще применяют shall в функции вспомогательного глагола, но так или иначе, язык меняется, и даже британцы соглашаются с тем, что он уже не стоит наравне с will. Сегодня вы узнаете, в каких случаях употребляется этот модальный глагол, как строятся с ним предложения и пройдете тест, чтобы проверить свои знания.

Этот модальный глагол употребляется без частицы to и произносится [ʃæl], в отрицательной форме транскрипция выглядит так [ʃɑːnt].

Рассмотрим, как строятся предложения с этим модальным глаголом:

Утвердительные предложения

В утверждениях ставим его после подлежащего:

– I shall talk to him tomorrow. – Я поговорю с ним завтра.

Очевидно, что это слово не используется с другими модальными глаголами, но можно употреблять его с need to/be able to/have to:

– I have good news! I shall be able to visit my parents in Spain! – У меня хорошие новости! Я смогу навестить родителей в Испании!

Отрицательные предложения

В отрицаниях вспоминаем про частицу not:

– I shan’t be able to visit my parents. – Я не смогу навестить родителей.

Полная форма используется в официальных ситуациях или, когда мы хотим подчеркнуть что-то. Носители язык нечасто употребляют отрицательную структуру.

[qsm quiz=59]

Вопросительные предложения

В вопросах глагол меняется местами с подлежащим (subject):

– Shall we meet for lunch? – А не встретиться ли нам за обедом?

И последнее, Shall используется в разделительных вопросах:

– I’ll drive you home, shall I? – Я отвезу тебя домой, хорошо?

Случаи употребления модального глагола Shall

Слово Shall никогда не является чисто модальным глаголом. Он всегда сочетает в себе модальное значение с функцией вспомогательного глагола, выражающего будущее время. Этот глагол по-прежнему используется для формулировки обязательства со вторым и третьим лицом в единственном и множественном числе, но он не распространен в этом значении в разговорном английском. Его использование, как правило, ограничивается формальным или даже архаическим стилем и встречается в основном в придаточных предложениях, где он структурно зависим:

– It has been decided that the proposal shall not be opposed. – Принято решение, что возражений против предложения не будет.

Однако измененное значение обязательства с этим глаголом все еще встречается в архаическом стиле со вторым и третьим лицом в единственном и множественном числе, за которым следует non-perfect infinitive в утвердительных и отрицательных предложениях.

Вот наглядная картинка, которая поможет запомнить первое, второе и третье лицо.

1. Promise and strong intention – обещание и сильное намерение

– I give you my word, you shall hear from me soon. – Я даю слово, я скоро дам о себе знать.

Здесь можно использовать следующие эквиваленты:

– to promise – обещаю;

– to intend – намерен делать.

Примеры:

– Dave promised me that he’d cook supper tonight. – Дейв пообещал мне, что он приготовит ужин сегодня вечером.

– How long are you intending to stay in Toronto? – Как долго ты планируешь задержаться в Торонто?

2. Threat or warning – угроза или предупреждение

– You shall fail at the exam if you don’t work hard. – Ты провалишь экзамен, если не будешь много работать.

В значении «угроза или предупреждение» можно использовать следующие синонимы:

– to warn – серьезно предупреждаю;

– to threaten – угрожаю.

Примеры:

– I’ve been warning her for weeks. – Я предупреждал ее несколько недель.

– She threatened to send every letter I’ve written to my mother-in-law. – Она угрожала отправить все письма, которые я написал своей свекрови.

3. Strict orders and instructions – Строгие приказы и инструкции

В этом значении слово shall используется для более официальных инструкций, особенно в официальных документах, где они могут рассматриваться как формальные правила. В других случаях модальные глаголы must или should предпочтительны для выражения идей такого рода.

Например:

– The hirer shall be responsible for maintenance of the vehicle. – Наниматель несет ответственность за сохранность транспортного средства.

- Как правило, shall как модальный глагол не переводится на русский язык, его смысл передается выразительной интонацией.

В этом пункте используются такие эквиваленты как:

– to make smb. to do smth. (smb. – somebody; smth. – something);

– to tell smb.;

– to order.

Примеры:

– I ordered him to sit by me – Я приказала ему сесть рядом со мной.

– I made them clean this room. – Я заставил их убрать эту комнату.

Русские эквиваленты:

– должны (а);

– перестаньте;

– прекратите.

4. An offer – предложение

В этом значении глагол используется в вопросительных предложениях с первым лицом единственного и множественного числа. На русский язык переводятся инфинитивом:

– Shall we go out for a meal tonight? – А не поужинать ли нам где-нибудь сегодня вечером?

Чтобы речь была красивой, используйте такие синонимические выражения:

– How about…? – Как насчет…?

– Why don’t we…? – Почему бы нам не…?

– Do you want me to do it? – Ты хочешь, чтобы я это сделал (а)?

– Am I to do it? – Мне сделать это?

– I suggest… – Я предлагаю…

Примеры:

– How about inviting them? – Как насчет того, чтобы пригласить их?

– Why don’t we go for a swim? – Почему бы нам не пойти поплавать?

– I suggest that we park the car here and walk into town. – Я предлагаю припарковать машину здесь и пойти в город.

5. Asking for suggestions or advice – спрашивать совета или предложения

В таких предложениях глагол встречается с вопросительным словом:

– What shall we do about Jerry if he doesn’t get into university? – Что мы будем делать с Джерри, если он не поступит в университет?

Синонимические выражения:

– What is your suggestion?

– What can you advise?

На русский можно переводить следующими фразами:

– Как ты думаешь?

– Кто (как) по-твоему…?

Таблица правила со всеми эквивалентами и переводом находится в документе, который можно скачать ниже.

[sdm_download id=”2405″ fancy=”0″]

Разница между Shall и Will

Как и в случае с can vs. could в стандартной грамматике британского английского языка существуют определенные «правила» различия между shall и will, о которых вам следует знать, даже если в настоящее время существует общее мнение, что эти два глагола, как правило, взаимозаменяемы в большинстве, но не во всех случаях. Ситуация немного отличается и в американском английском. Ниже приводятся основные правила использования этих двух глаголов.

I shall be in London, but you will be in China

Will используется в нескольких случаях, но в основном (после него следует инфинитив другого глагола) чтобы говорить о будущем:

– When will you go to London? – Когда ты поедешь в Лондон?

– If we have some time we will come and see you. – Если у нас будет время, мы навестим тебя.

– Sue wants to speak to you. – Сью, хочет поговорить с тобой.

– O.K. I will give her a call. – Хорошо, я ей позвоню.

Любители правильной грамматики, возможно, уже начали прыгать вверх и вниз после прочтения приведенных выше примеров. Почему? Ну, в традиционной британской грамматике правило заключается в том, что will должен использоваться только с местоимениями второго и третьего лица (you; he, she, it, they). А I and We нужно использовать с shall. Это означает, что, строго говоря, примеры неверные, и следует применять их так:

– If we have some time we shall come and see you.

– Sue wants to speak to you.

– O.K. I shall give her a call.

На практике и, особенно при разговоре, носители сокращают эти слова, например, I’ll, He’ll etc. Поэтому не нужно беспокоиться, какой из глаголов лучше всего использовать, когда речь идет о будущем времени.

Shall I? Will you? Let’s

Давайте сразу посмотрим на два примера:

– Will you shut the door? – Закроешь дверь? (Не могли бы вы закрыть дверь?)

– Shall I shut the door? – Мне закрыть дверь? (Вы хотите, чтобы я закрыл дверь?)

Прочитав перевод и пояснение в скобках можно понять, что с will мы хотим, чтобы кто-то сделал что-то для нас, а с shall мы предлагаем человеку, чтобы мы что-то сделали.

Когда используем глагол shall после слова Let’s – это значит, что мы вносим предложение, например: Let’s buy new furniture, shall we? – Давай купим новую мебель, хорошо?

Predictions and intensions – предсказания и намерения

Модальный глагол, которому мы посвятили всю статью, иногда используется вместо will с местоимениями «I – Я и We – мы» в формальных контекстах для выражения предсказания или, когда говорим о каком-либо намерении.

Сравните два предложения:

American English

С помощью OEC (Oxford English Corpus) мы обнаруживаем, что shall используют 28,7% англичане, а 17,8% – американцы.

Когда речь идет о будущем времени, Will доминирует и, похоже, что его помощник shall вышел из употребления.

Согласно Garner’s Modern American Usage, shall является «второстепенным глаголом» и встречается в основном в вопросах, выражающих предложения или, когда спрашиваем совета.

Вывод только один: всегда используйте, те слова и модальные глаголы, которые чаще применяют носители языка.

Чтобы понять разницу, предлагаем посмотреть видео на английском.

Разница между Shall Should

Как мы уже говорили в статье «модальный глагол should/ought to» различие между ними в том, что should это прошедшая форма shall. В настоящее время эти слова используются как два отдельных модальных глагола, у которых есть свои функции употребления.

Посмотрите короткое и отличное объяснение данного правила.

Should может использоваться в условных предложениях (if-clause) выражающих предположение, то есть мы хотим, чтобы событие произошло, хотя это маловероятно.

Взглянем на пример:

– If you should travel to Poland, buy me a T-shirt with a Polish flag on it. – Если вдруг ты поедешь в Польшу, купи мне майку с польским флагом.

А также should может идти в начале предложения. В этом случае, if не используется.

– Should she come, ask her to wait. – Случись так, что она придет, попроси ее подождать.

Но эти два предложения звучат старомодно. Люди редко используют, конструкцию “you should” в современном английском. Большинство носителей языка, вероятно, скажут: ‘If you are in Poland’ or ‘if you go to Poland’.

Вместо should употребляется слово happen.

Пример:

– If you happen to meet Nick, tell him that I don’t want to see him. – Если ты случайно встретишь Ника, скажи ему, что я не хочу его видеть.

Упражнение на пройденную тему

[qsm quiz=39]

Загрузка…

Разница между shall и will не бросается в глаза — они оба могут служить для формирования будущего времени и даже подменять друг друга. Но так как глаголы эти модальные, с ними не все так просто. Конечно, первое, что приходит в голову в связи с will и shall — это будущее время. Но еще они могут способствовать выражению намерения или долженствования.

Дела давно минувших дней

Давным-давно, когда смартфоны еще не изобрели (как и интернет с телевидением), английская грамматика была более или менее упорядоченным явлением.

Традиционные правила предписывали употребление shall с первым лицом (I — я и we — мы), в том случае, если нужно было сформировать будущее время без дополнительных смыслов. С остальными лицами можно было использовать will.

Выглядело это примерно так:

I shall meet Miss Edwards tomorrow. Я завтра встречусь с мисс Эдвардс.

We shall stay in London. Мы остановимся в Лондоне.

Miss Edwards will be delighted. Мисс Эдвардс будет очень рада.

They will meet us at the station. Они встретят нас на вокзале.

Если will употреблялось в первом лице, то это выражало идею устремленности, решительности.

I will speak to Miss Edwards about her dog digging up my flower bed! Я поговорю с Мисс Эдвардс о ее собаке, которая копает мою цветочную клумбу!

We will definitely solve this problem. Мы обязательно разрешим эту проблему.

Когда эта уверенность в будущем действии проецировалась на кого-то другого (на второе или третье лицо), то использовалось shall:

You shall obey me.Ты будешь меня слушаться.

Margarete shall help you with that. Маргарет обязательно поможет вам с этим.

А на самом деле…

Теперь мы должны раскрыть все карты и признаться, что эти правила давно никем не соблюдаются. Носители английского свободно употребляют оба глагола с любыми лицами. Главное, что стоит помнить — will употребляется во много раз чаще, чем shall.

Хотя есть, по крайней мере, один случай, когда знание старых правил вам пригодится: если вы любите классическую английскую литературу и хотите читать ее в оригинале.

Алиса, та самая, которая попала в Страну Чудес, постоянно использует shall c первым лицом и will — с другими лицами. Все-таки, она была образованной английской девочкой из хорошей семьи.

I shall be punished for it now, by being drowned in my own tears! That will be a queer thing, to be sure! Вот теперь я в наказание еще и утону в собственных слезах! Вот уж, действительно, будет странно!

I do hope it will make me grow large again. Я надеюсь, это поможет мне снова вырасти.

Сокращенный вариант

В разговорной речи можно не переживать о том, какой глагол ставить — можно просто использовать сокращения после местоимений. Кто узнает, какой именно глагол скрывается за двумя буквами «l»?

I’ll be there at 6. Я буду там в шесть.

They’ll come over for dinner. Они зайдут поужинать.

Правда, в сокращении отрицаний разница все же есть: «will not» становится won’t, a «shall not» превращается в shan’t. Правда, этот последний вариант крайне редко употребляется в Америке, да и на других континентах его можно слышать все реже.

Will (shall) — разница все же есть?

Да, существуют случаи, когда употребляется только will или только shall. Давайте их разберем!

Хотя глагол shall стремительно выходит из употребления как показатель будущего времени, все же в каких-то значениях он закрепился.

- Например, когда вы предлагаете кому-то что-то или задаете уточняющий вопрос, можно начать предложение с shall, либо поставить его в конец:

Shall I help you? Вам помочь?

Let’s go, shall we? Пойдем?

Окончание «shall we?» в последнем примере выражает некое нетерпение и даже, в какой-то степени, авторитарность. Это более формальная альтернатива окончанию «Okay?», которое ставится, когда мы ожидаем согласия от собеседника.

Сравните:

Let’s just do it, okay? Давай просто сделаем это, ок?

Let’s just do it, shall we? Давайте просто сделаем это?

- В утвердительных предложениях shall имеет значение приказа или инструкции.

Например, в конституции одного из американских штатов это слово упоминается 1767 раз. Неплохо для устаревшего глагола-аутсайдера!

The courts of justice of the State shall be open to every person. Органы правосудия штата доступны каждому человеку.

No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. Ни один человек не может быть лишен жизни, свободы или имущества без законного основания.

Marriage in this state shall consist only of the union of one man and one woman. Браком в этом штате называется только союз одного мужчины и одной женщины.

- Также, когда люди говорят о чем-то торжественно или описывают очень важные события, зачастую выбор падает на shall.

В романе «Робинзон Крузо» у Даниеля Дефо капитан во время шторма говорит:

Lord be merciful to us! We shall be all lost! We shall be all undone! Господи, смилуйся над нами, иначе мы погибли, всем нам конец!

- Will, в отличие от shall, используется, чтобы описывать привычные регулярные действия. Часто (но не всегда) речь ведется о тех привычках, которые раздражают говорящего.